↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Modern Language Models (LLMs) often undergo a final training stage using preference feedback to enhance their capabilities. However, the methods used vary widely, making it difficult to isolate the effects of data, algorithms, reward models, and training prompts. This lack of understanding hinders the development of more effective LLM training strategies.

This paper systematically studies these four core aspects of preference-based learning, comparing the performance of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). The results show that data quality matters most, followed by the algorithm choice (PPO outperforming DPO), reward model quality, and finally, the choice of training prompts. While scaling reward models showed gains in mathematical evaluation, other categories saw only marginal improvement. The study also provides a recipe for effective preference-based learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it systematically investigates the impact of various factors on preference-based learning, a critical step in improving large language models. It offers a practical recipe for better LLM training and opens avenues for future research on enhancing model performance and alignment.

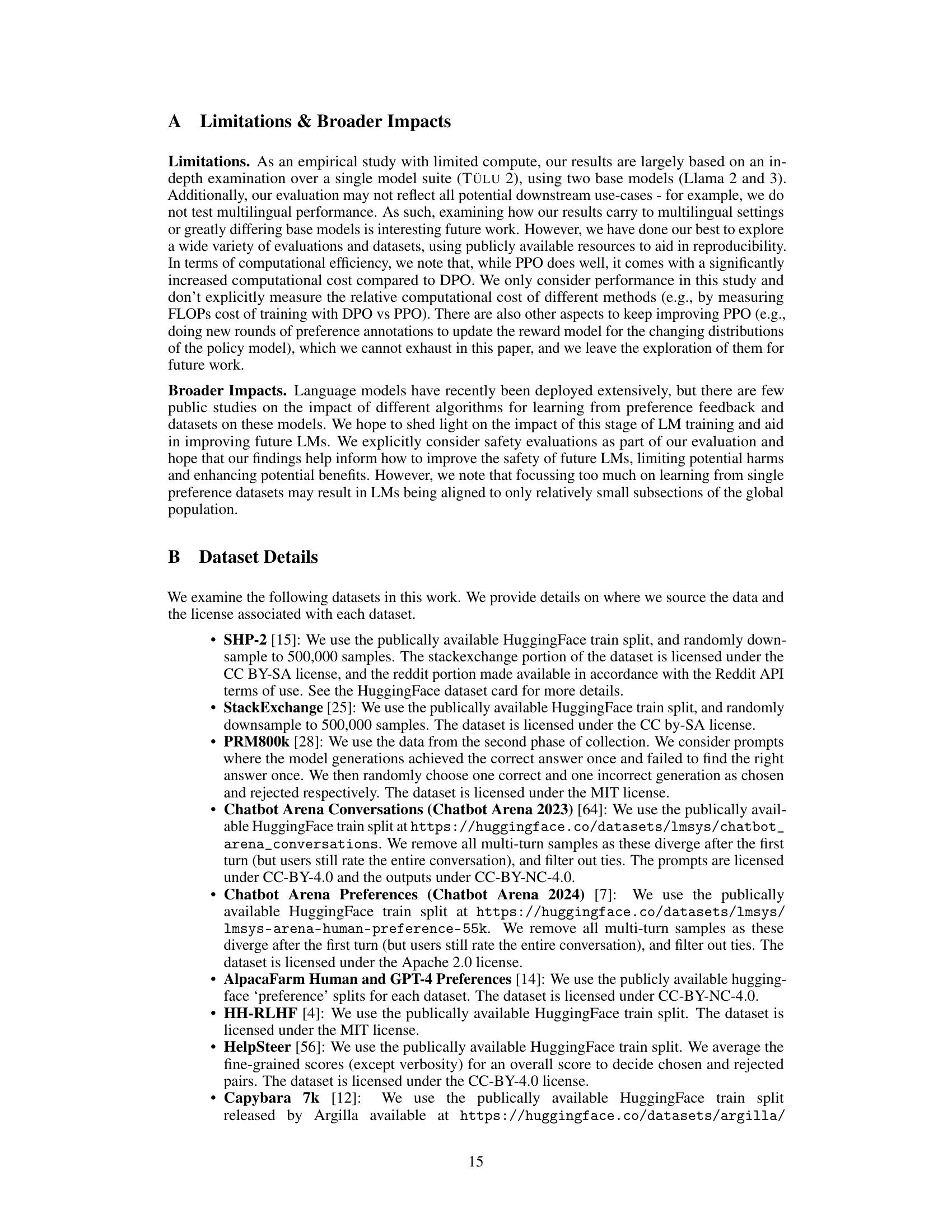

Visual Insights#

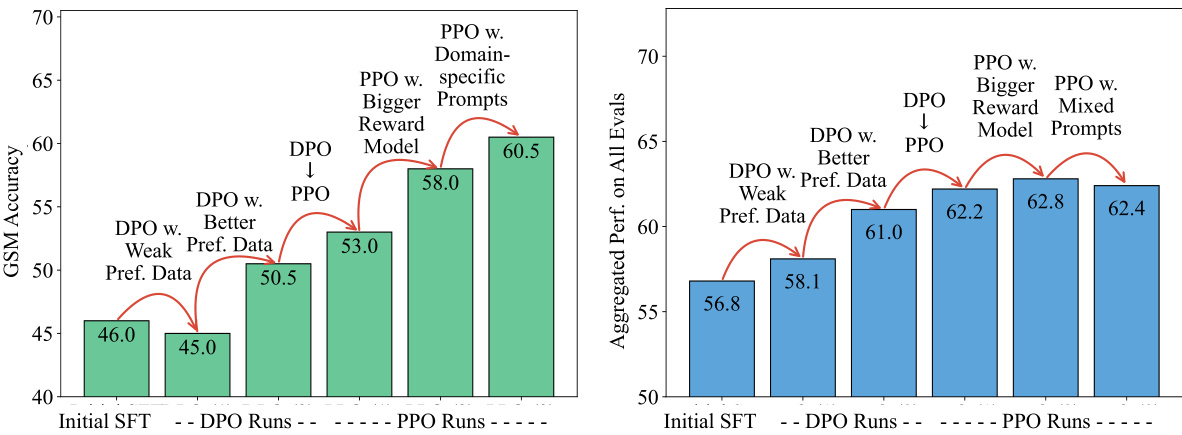

This figure shows the impact of different factors on the performance of a language model trained using preference feedback. The left panel shows accuracy on the GSM (Grade School Math) benchmark, focusing on mathematical reasoning. The right panel displays the overall performance across 11 different benchmarks. Each bar represents a model trained with a specific combination of factors, such as the quality of preference data, learning algorithm (DPO or PPO), and reward model. The figure highlights the importance of each of these factors in achieving good performance. Notably, PPO generally outperforms DPO, and high-quality preference data leads to the most significant improvement.

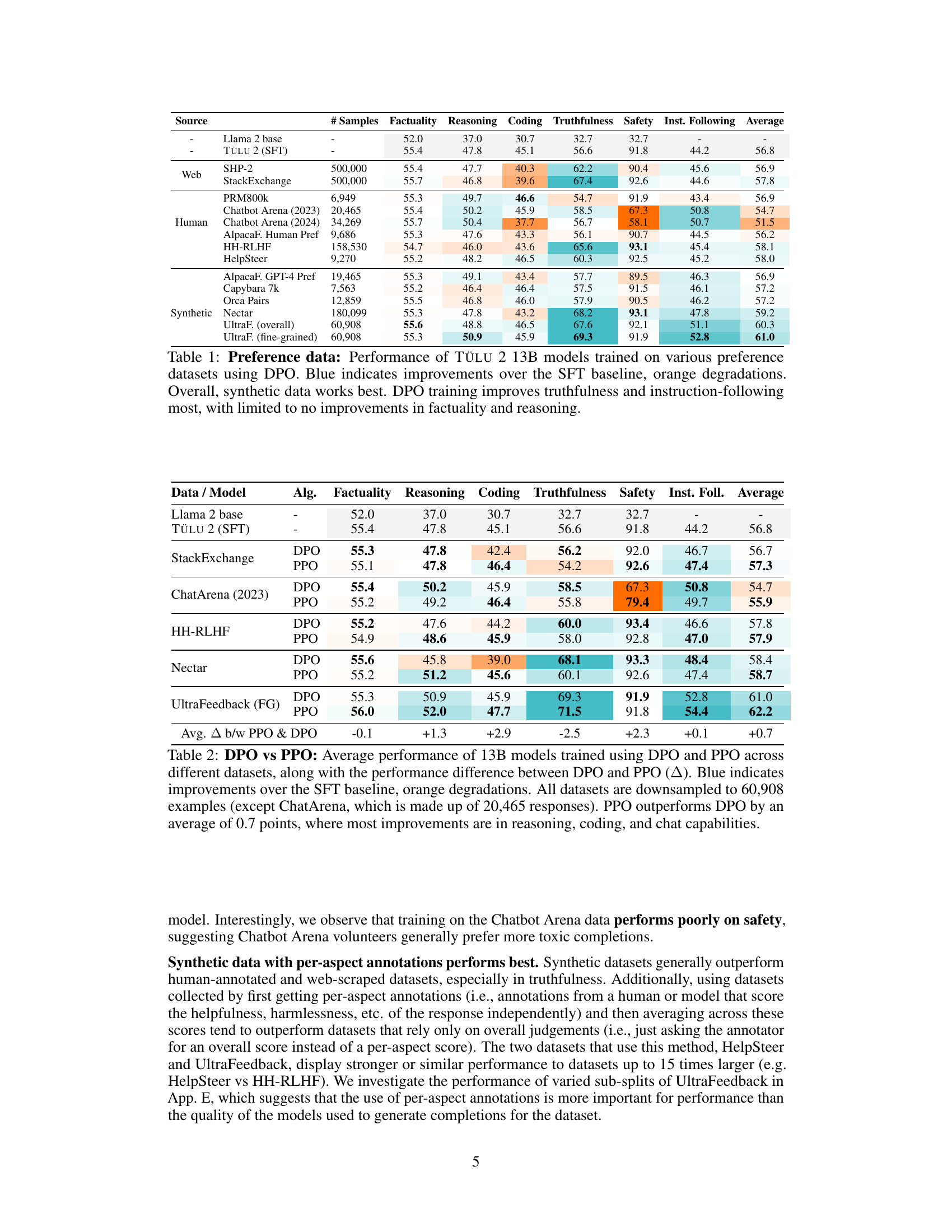

This table presents the results of training a 13B parameter TÜLU language model using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) on fourteen different preference datasets. The table shows the model’s performance across several evaluation categories (Factuality, Reasoning, Coding, Truthfulness, Safety, and Instruction Following). The performance is compared against a baseline model trained with supervised fine-tuning (SFT). The color-coding highlights improvements (blue) and degradations (orange) compared to the baseline. The overall findings indicate that synthetic datasets tend to yield the best results, and DPO training primarily improves truthfulness and instruction-following capabilities.

In-depth insights#

Pref-Based Learning#

Preference-based learning (Pref-based learning) offers a powerful paradigm for enhancing language models by leveraging human preferences over generated outputs. This method sidesteps the complexities of precisely defining reward functions, a significant challenge in traditional reinforcement learning. Instead, it directly optimizes the model based on human judgments comparing different outputs. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with nuanced aspects of language like helpfulness, harmlessness, or overall quality, which are difficult to capture with explicit rules. The choice of data, algorithm, and reward models significantly impacts performance. High-quality preference data is crucial, with synthetic data often demonstrating superior results compared to manually annotated sets. Effective algorithms, such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), are key to successfully integrating these preferences into model training. While simpler methods like Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) exist, PPO often outperforms DPO in diverse downstream tasks, though at a higher computational cost. Further research into developing more efficient and scalable pref-based learning methods remains important, especially concerning large-scale deployment.

PPO vs. DPO#

The comparison of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Direct Policy Optimization (DPO) for learning from preference feedback reveals crucial differences in their approaches and performance. PPO, an online method, trains a reward model to score generated responses, iteratively refining a policy model based on these scores. DPO, conversely, is an offline method, directly training the policy model on preference data without an intermediary reward model. While DPO offers computational efficiency, PPO demonstrates superior downstream performance across various evaluation metrics, particularly in complex tasks requiring reasoning and code generation. The choice between PPO and DPO involves a trade-off between computational cost and performance gains, with PPO’s enhanced capabilities justifying its higher computational demand in many scenarios.

Reward Model Impact#

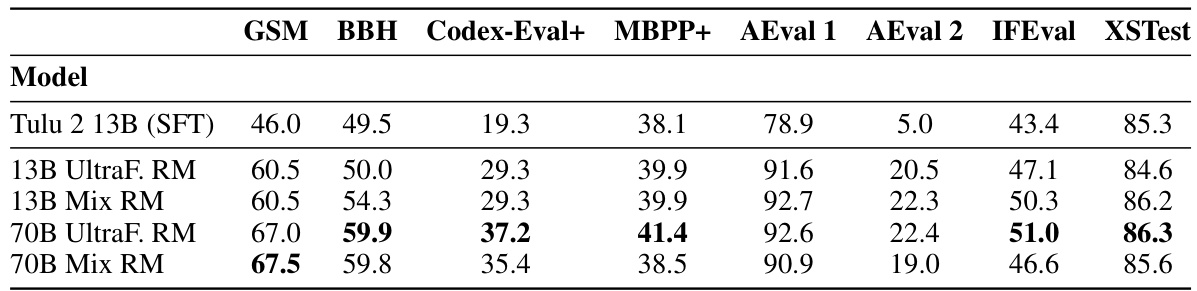

The study’s findings on reward model impact reveal a complex relationship between reward model size and performance. Larger reward models (70B parameters) yielded significant improvements on specific tasks, most notably GSM (mathematics reasoning), exceeding gains from smaller models. However, this improvement didn’t generalize broadly across all benchmarks. Surprisingly, other categories showed only marginal gains despite significant gains in mathematical evaluations. This suggests that while scaling up reward model size can be beneficial for specialized tasks, it may not necessarily translate to substantial improvements in overall model performance. The quality and diversity of the reward model training data also play a crucial role, highlighting the need for high-quality preference data for optimal results. The research emphasizes the need for comprehensive evaluation across diverse benchmarks rather than relying solely on a limited set of metrics to accurately gauge overall performance improvements. This highlights a critical challenge in effectively leveraging learning from preferences — achieving improvements across a wide range of abilities remains difficult even with significantly improved reward models.

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering plays a crucial role in effectively utilizing large language models (LLMs). Careful crafting of prompts significantly impacts the quality and relevance of LLM outputs. The paper highlights that prompt engineering is not a standalone process, but rather deeply intertwined with other aspects of LLM training and fine-tuning, such as data selection and reward model design. High-quality prompts, particularly those tailored to specific downstream tasks, can substantially improve model performance. However, the paper also suggests that the effectiveness of prompt engineering is dependent on the strength of other components within the training pipeline. While targeted prompts can yield significant gains in specific areas, applying more general prompts and leveraging well-trained reward models can provide more robust performance across diverse tasks. Therefore, a well-rounded approach, combining effective prompt engineering with other best practices, is essential for maximizing the capabilities of LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize expanding the scope of learning from preference feedback beyond the current limitations. Addressing the computational cost of PPO and the scalability challenges of large-scale reward models is crucial. Investigating the impact of diverse, high-quality preference data from various sources, including synthetic generation and human annotation, is needed. Exploring more efficient algorithms than PPO, that can match or surpass its performance while maintaining scalability, is another key area. Furthermore, future efforts should focus on understanding how to better incorporate domain-specific knowledge and contextual information into reward models to improve downstream performance. A deeper investigation into handling potential biases embedded in existing datasets is also necessary to create fairer and more robust language models. Finally, expanding the evaluation benchmarks beyond currently used metrics to incorporate a broader range of capabilities would provide a more thorough understanding of the impacts and limitations of these approaches.

More visual insights#

More on figures

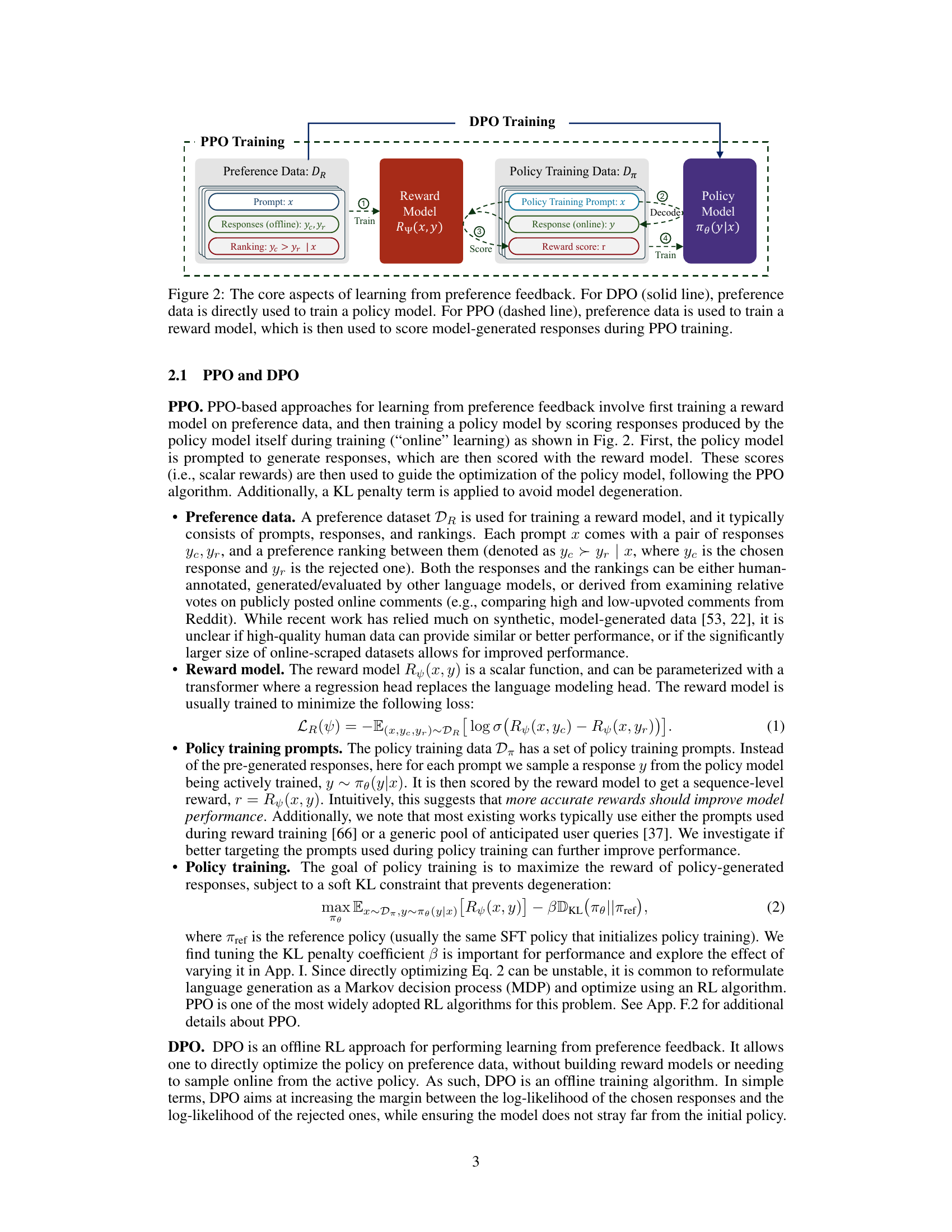

This figure illustrates the core components of two prominent preference-based learning algorithms: Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). DPO directly trains a policy model using preference data, represented by prompts, responses, and rankings. In contrast, PPO uses a two-stage approach. First, it trains a reward model on the preference data. Then, this reward model scores the responses generated by the policy model during training. These scores guide the policy model’s training, resulting in improved response quality based on the learned preferences.

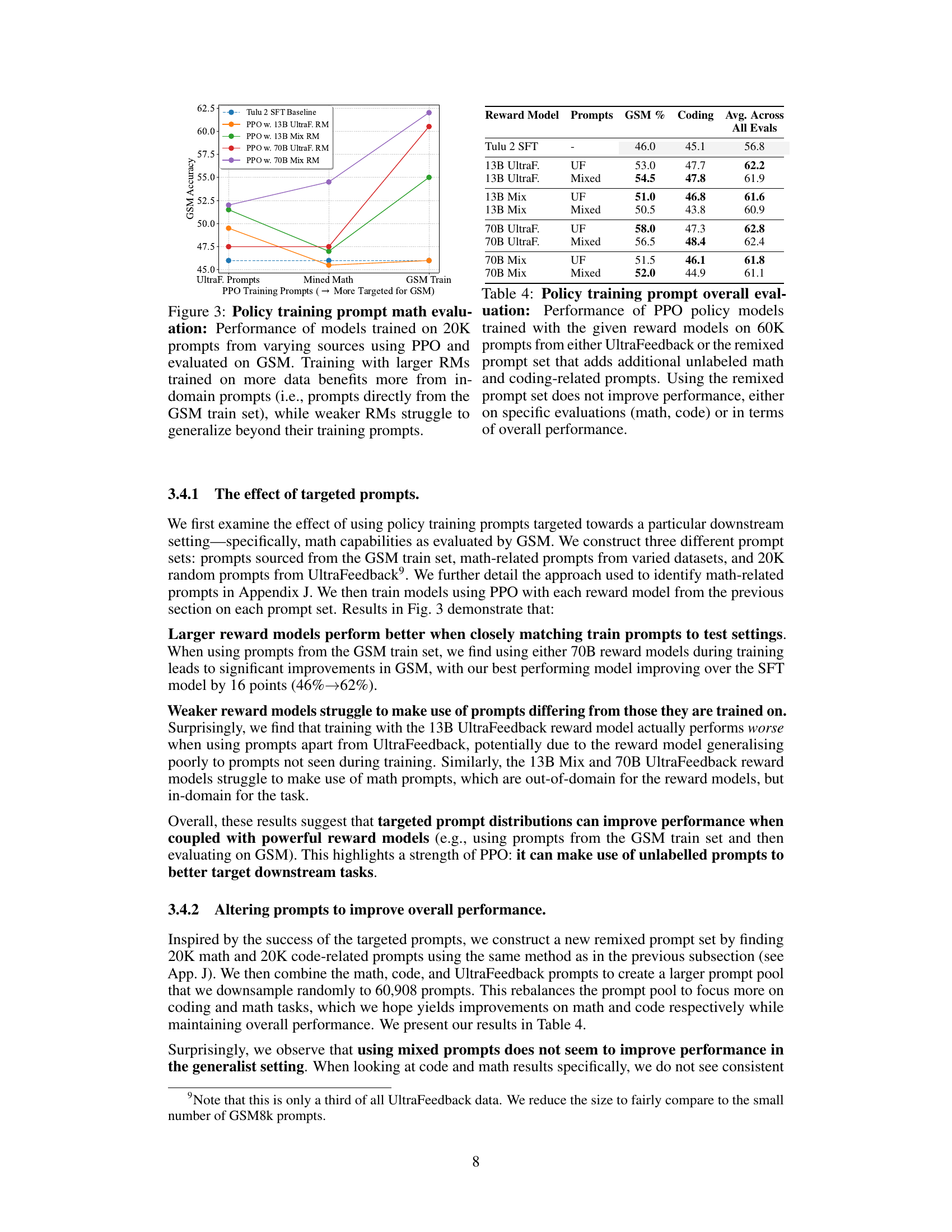

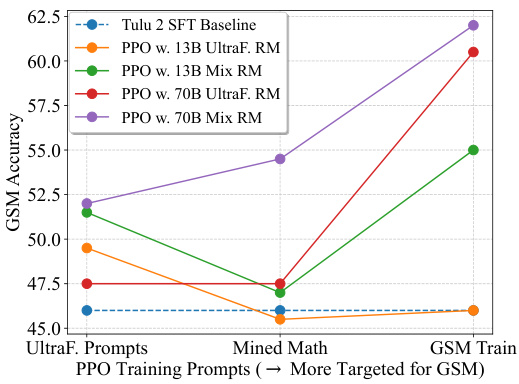

This figure shows the results of an experiment where the authors trained models using different sets of prompts in the PPO algorithm, and evaluated their performance on the GSM math task. They varied the size and training data of the reward model, and the source of the policy training prompts (UltraFeedback, prompts specifically mined for math, or prompts directly from the GSM training set). The results indicate that larger reward models trained on more data perform significantly better when using prompts matched to the test setting (GSM training prompts), demonstrating the importance of tailoring prompts to the specific task.

This figure shows the effect of different KL penalty coefficients (β) on the performance of models trained with 13B and 70B UltraFeedback Reward Models (RMs). It presents three subfigures: (a) GSM Accuracy: Illustrates the accuracy on the GSM (GSM8k) benchmark as β varies. (b) AlpacaEval 2 Winrate: Shows the winrate on the AlpacaEval 2 benchmark as β varies. (c) Overall Average: Displays the overall average performance across all evaluation metrics. The results indicate that the optimal β value depends on the RM size. The 70B RM shows more robustness to changes in β compared to the 13B RM. Interestingly, AlpacaEval 2 performance increases as β decreases, suggesting a trade-off between performance on different benchmarks when tuning β.

This figure displays the performance of eleven different evaluation metrics across various training steps during the PPO training process. The training utilizes the 70B UltraFeedback Reward Model and UltraFeedback prompts, extending over three epochs. Each metric’s performance trajectory is plotted, revealing the changes over time. The grey dashed lines demarcate epoch boundaries for easier visualization and understanding of the training progress.

This figure displays the performance change over training steps for three different evaluation metrics: AlpacaEval 2, IFEval, and GSM8k. The training utilized the 70B UltraFeedback Reward Model and UltraFeedback prompts over three epochs. Dashed lines in the graph mark the boundaries between each epoch.

More on tables

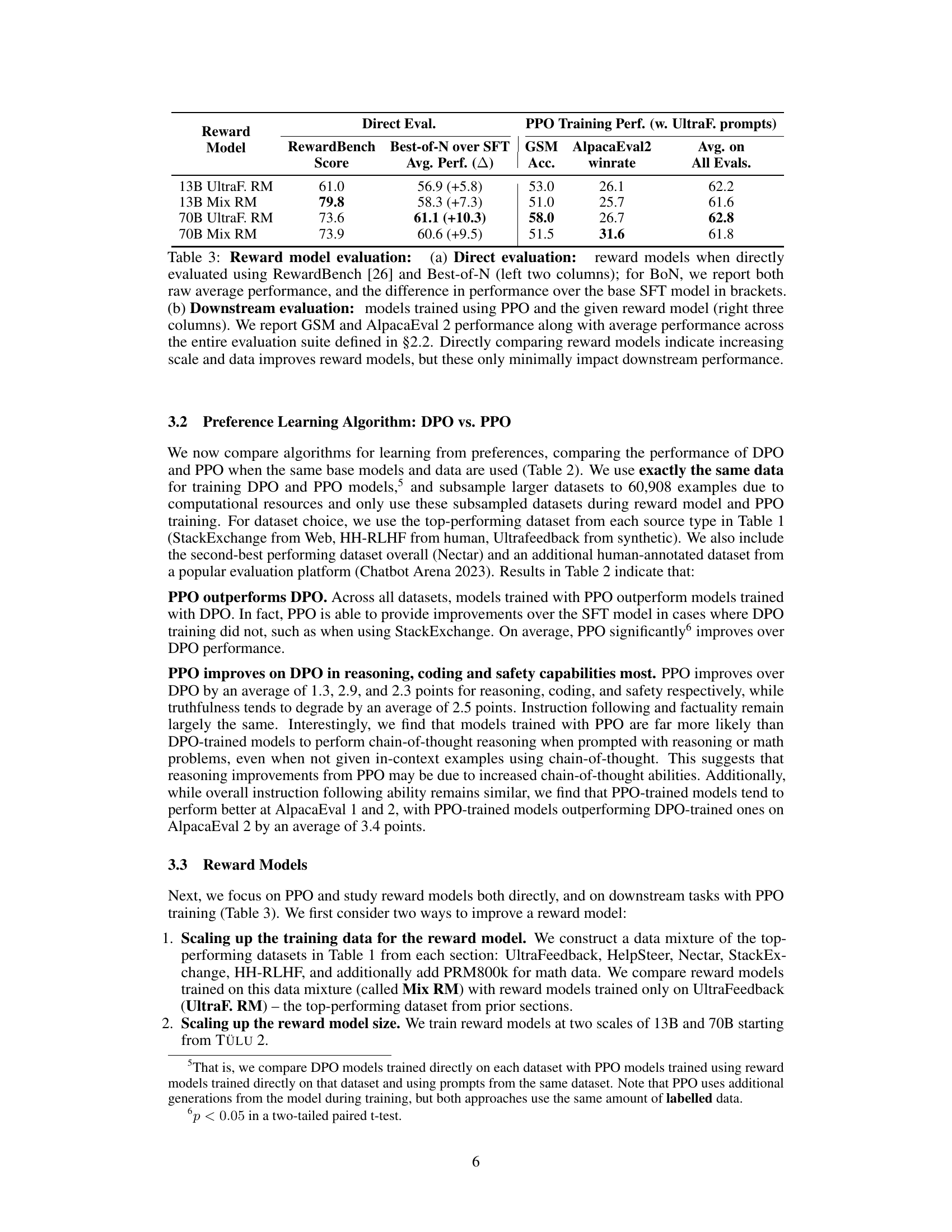

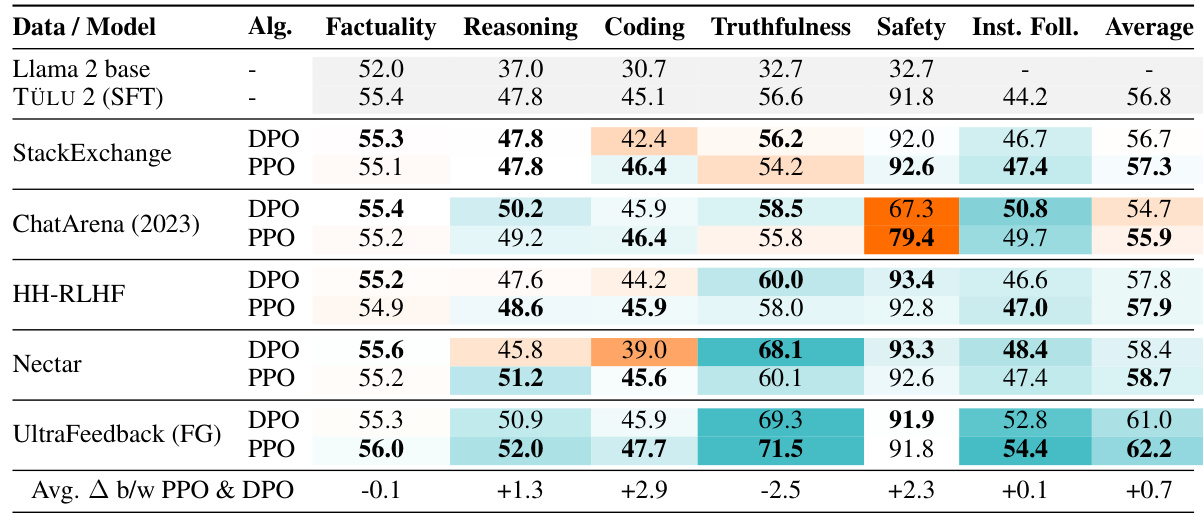

This table compares the performance of DPO and PPO on several datasets. It shows the average performance across various evaluation categories (factuality, reasoning, coding, etc.) for both algorithms, highlighting the difference in performance between them. The table emphasizes that PPO generally outperforms DPO, particularly in reasoning, coding, and conversational abilities.

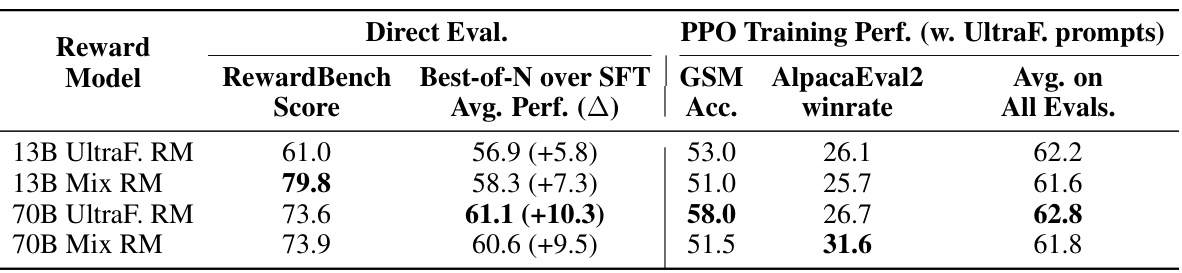

This table presents the results of evaluating reward models both directly and indirectly through downstream PPO training. Direct evaluation uses RewardBench and Best-of-N metrics to assess the quality of the reward models. Downstream evaluation measures the impact of using different reward models on the performance of PPO-trained policy models across various benchmarks, including GSM and AlpacaEval2.

This table shows the results of an experiment evaluating the effect of different policy training prompts on the performance of models trained using PPO with different reward models. Two sets of prompts were used: UltraFeedback prompts and a remixed set of prompts that included additional math and coding-related prompts. The table reports the average performance across multiple evaluation metrics. The findings suggest that using the remixed prompt set did not significantly improve model performance.

This table presents the performance comparison of different language models, including several popular open-source models and the authors’ best-performing models. The models are evaluated across multiple benchmarks measuring various capabilities like factuality, reasoning, coding, truthfulness, safety, and instruction following. The table highlights the superior performance of models trained using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm with a large reward model, especially when combined with a mixed set of prompts tailored for specific tasks.

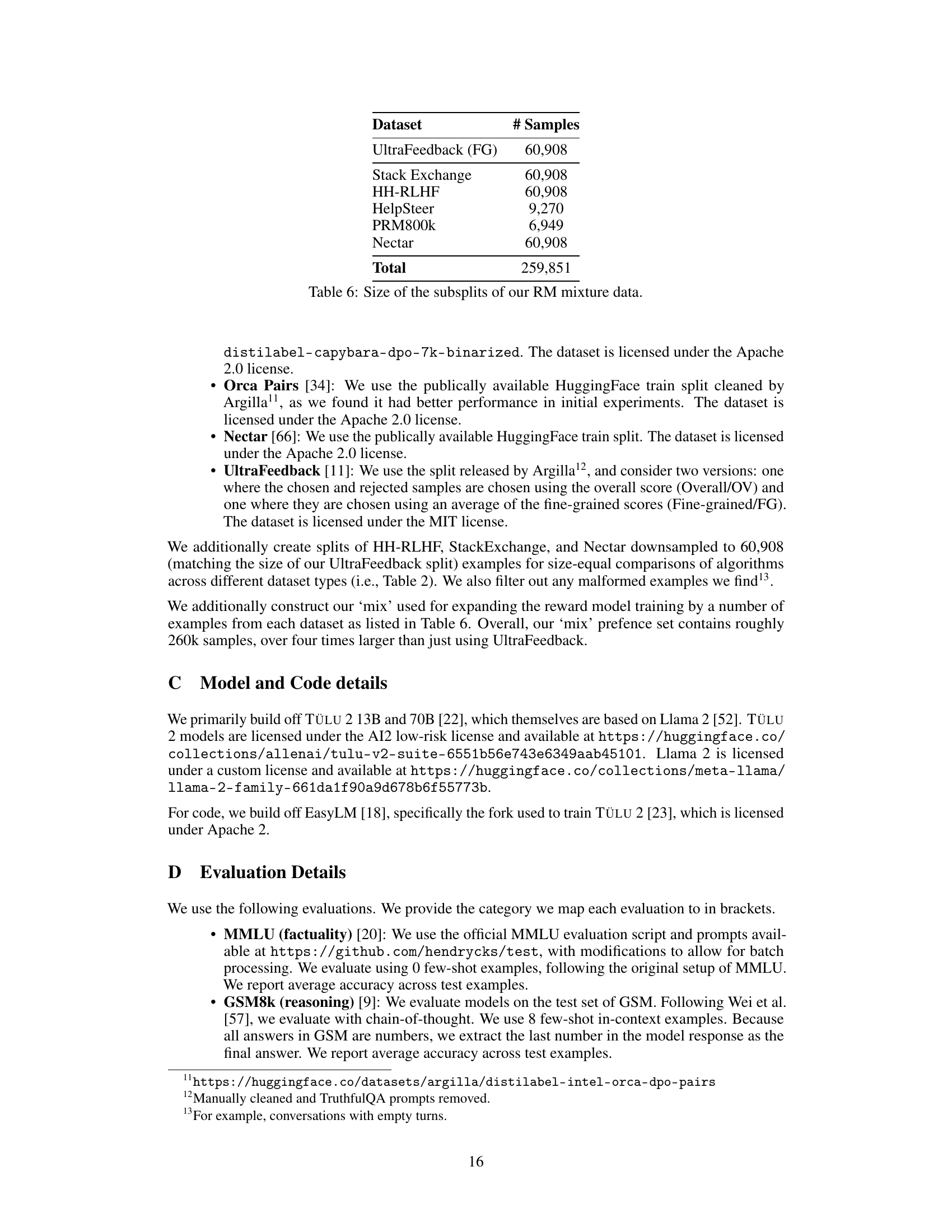

This table shows the number of samples used for each of the six datasets in the reward model (RM) mixture data. The datasets were subsampled to create a balanced mixture for training the reward model, except for HelpSteer and PRM800k, which retained their original sizes. The total number of samples in the RM mixture data is 259,851.

This table presents the results of training the TÜLU 2 13B language model using the DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) algorithm on fourteen different preference datasets. The table shows the performance of the resulting models across several evaluation metrics, including factuality, reasoning, coding, truthfulness, safety, and instruction following. The color-coding highlights datasets where the model performance improved (blue) or decreased (orange) compared to a standard Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) baseline. The overall findings suggest that synthetic preference datasets generally lead to better model performance compared to real-world datasets.

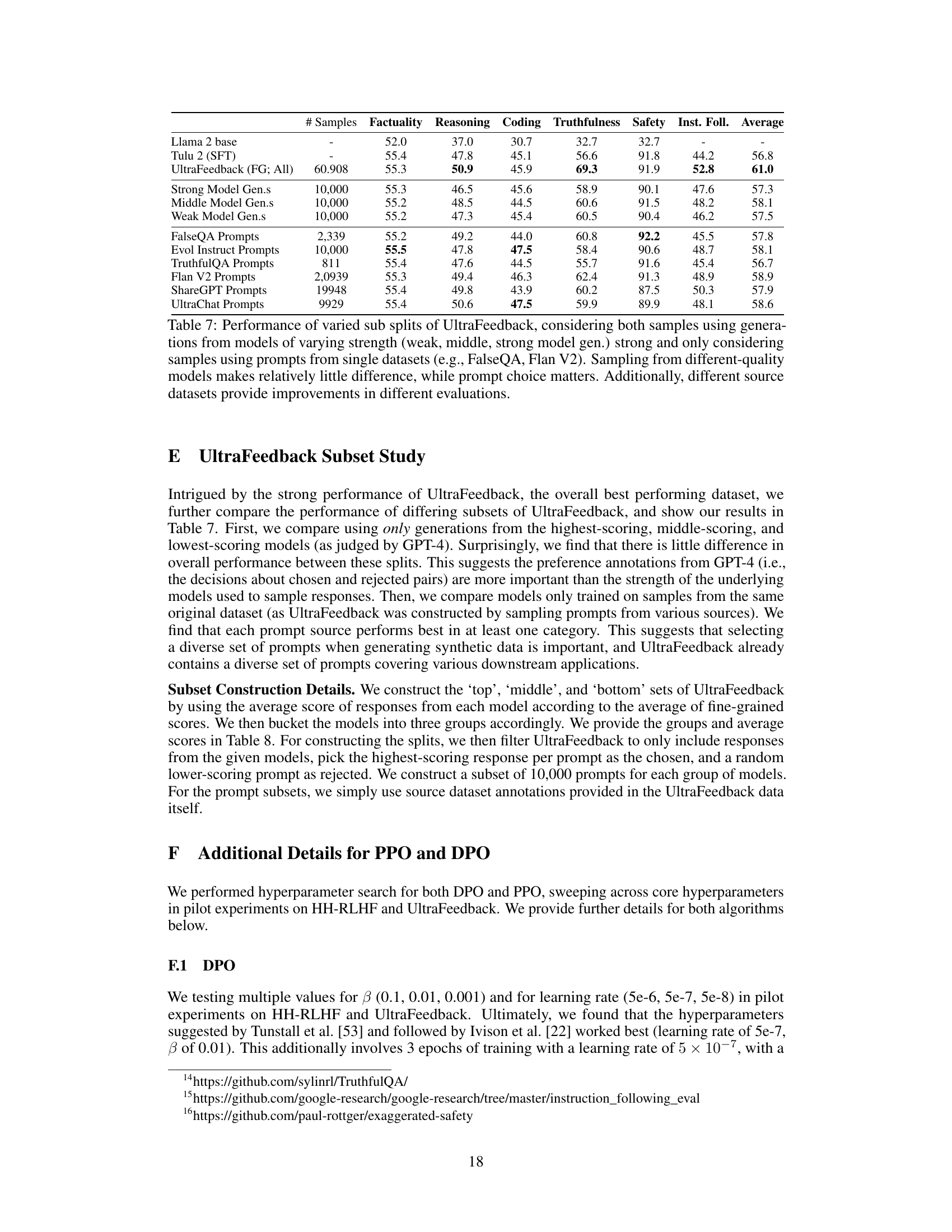

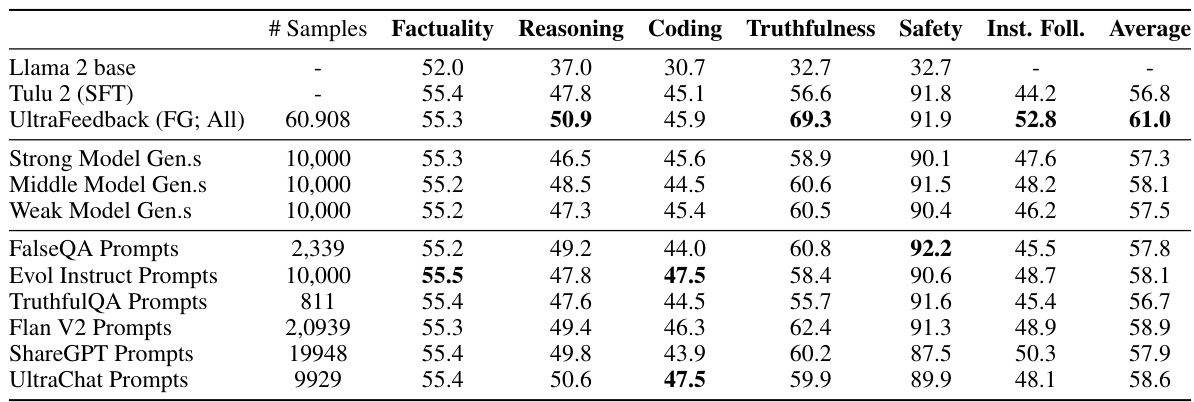

This table shows the results of using different subsets of the UltraFeedback dataset. It explores the impact of model quality (weak, middle, strong) on performance when generating responses, as well as the performance of using prompts from different datasets. The findings suggest that model quality has a relatively small impact compared to prompt source, and different sources improve performance on different evaluation metrics.

This table presents the performance of models trained using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) on various preference datasets. The performance is measured on several downstream tasks related to language model capabilities. The results show that synthetic datasets generally lead to better performance than human-annotated or web-scraped data. The use of DPO improves instruction following and truthfulness more than other aspects (factuality and reasoning).

This table compares different implementations of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm, highlighting key differences in their approaches. It contrasts our implementation with those from several other open-source projects (Quark, Rainier/Crystal, FG-RLHF, AlpacaFarm) by detailing the presence or absence of specific techniques. These techniques include initializing the value model from the reward model, using the EOS trick for truncated completions, reward normalization, reward whitening, advantage whitening, the use of an adaptive KL controller, KL clamping, and employing multiple rollouts per prompt.

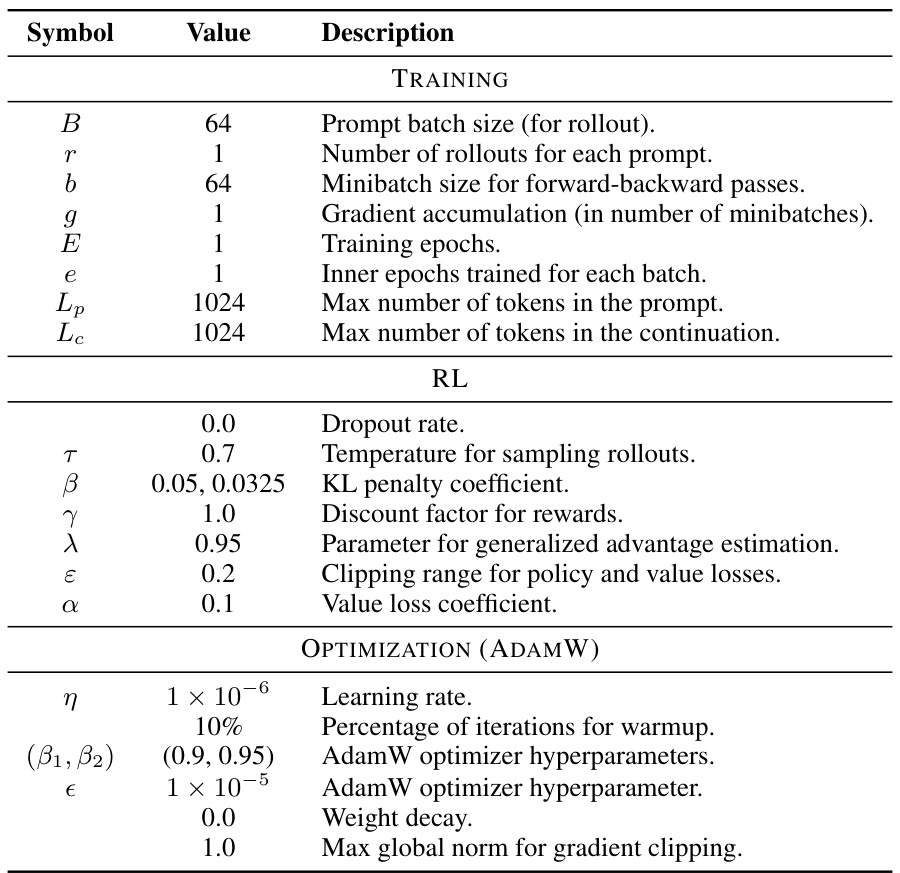

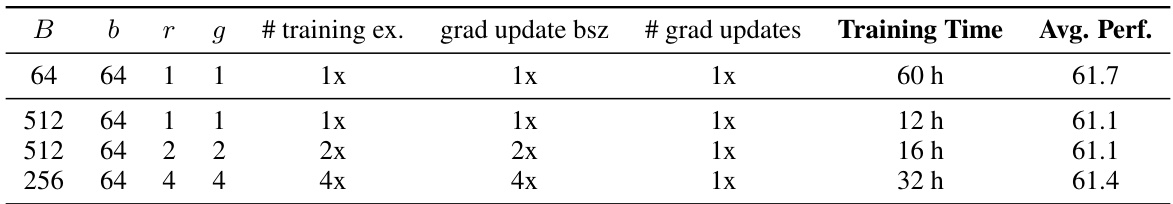

This table compares the performance of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm under different prompt batch sizes. It shows that increasing the batch size can reduce training time, but at the cost of some performance degradation. However, this performance loss can be mitigated by increasing the number of rollouts and gradient accumulation steps.

This table compares the performance of two preference-based learning algorithms, DPO and PPO, across multiple datasets. It shows the average performance scores for several categories (Factuality, Reasoning, Coding, Truthfulness, Safety, Instruction Following) and highlights the difference in performance between DPO and PPO for each dataset. The results indicate that PPO generally outperforms DPO, particularly in reasoning, coding, and chat-related tasks.

This table presents the detailed results of evaluating reward models using the RewardBench dataset. Reward models of varying sizes (13B and 70B) trained on different datasets (UltraFeedback and a mixture of datasets) are assessed. The ‘Score’ column reflects the overall performance across various sub-categories of RewardBench (Chat, Chat Hard, Safety, Reasoning, Prior Sets), with prior sets weighted differently than other categories as per Lambert et al. [26]. This provides a more granular view of the reward model performance compared to the summary in Table 3.

Full paper#