↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Preference-based Reinforcement Learning (PbRL) traditionally focuses on maximizing average reward, ignoring risk. This is problematic for safety-critical applications like healthcare and autonomous driving, where risk-averse strategies are essential. Existing risk-aware RL methods are not directly applicable to PbRL’s unique one-episode reward setting.

This paper introduces Risk-Aware PbRL (RA-PbRL), a novel algorithm that addresses this gap. RA-PbRL incorporates nested and static quantile risk objectives, enabling the optimization of risk-sensitive policies. Theoretical analysis demonstrates sublinear regret bounds, proving the algorithm’s efficiency. Empirical evaluations on various tasks confirm RA-PbRL’s superior performance compared to risk-neutral baselines, highlighting its practical value in safety-critical applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation of existing preference-based reinforcement learning (PbRL) methods: their inability to handle risk effectively. RA-PbRL offers a novel solution by incorporating risk-aware objectives and developing a provably efficient algorithm. This work is relevant to current research trends in safe and robust AI, which require algorithms that can reason about the potential risks associated with their actions. RA-PbRL opens avenues for further research in risk-sensitive decision making and preference learning.

Visual Insights#

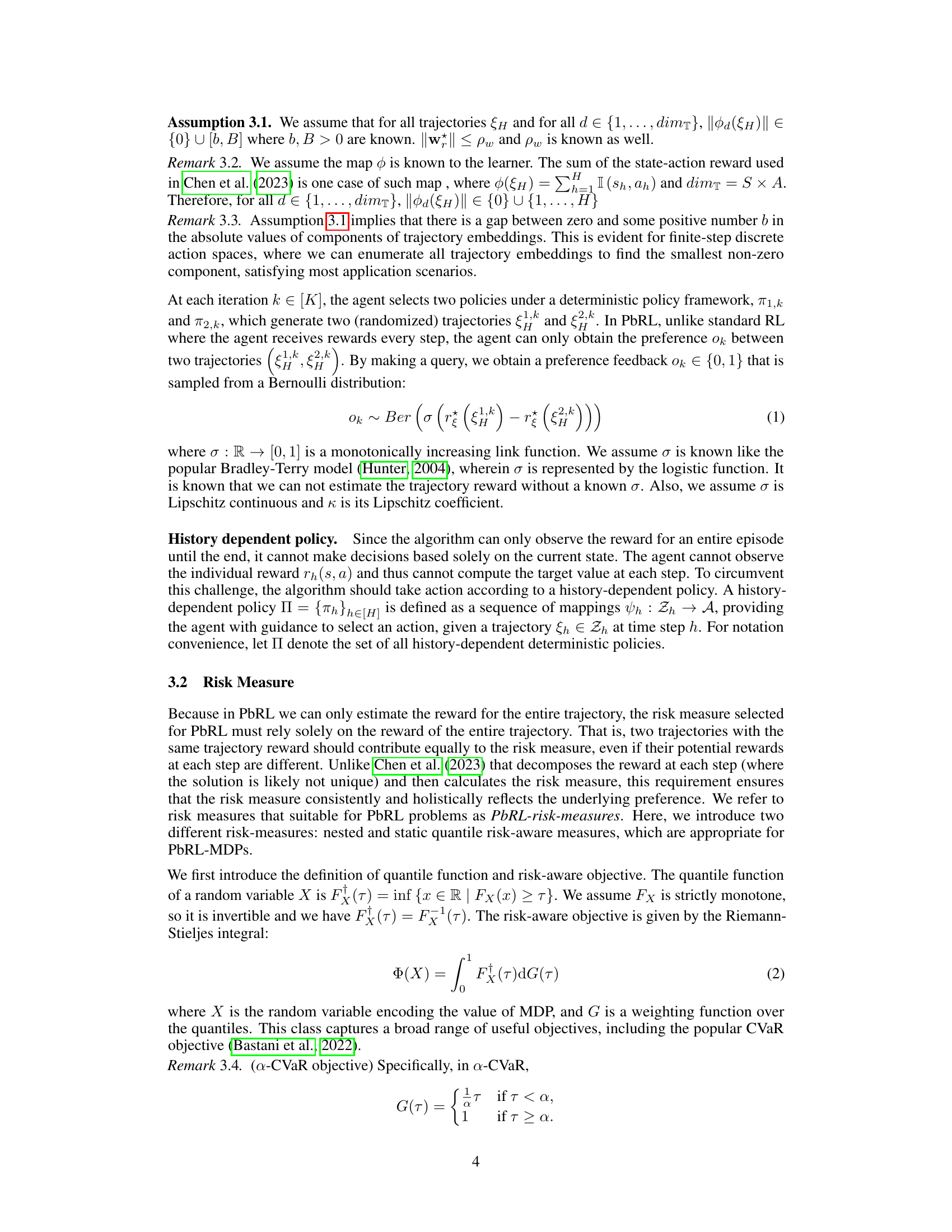

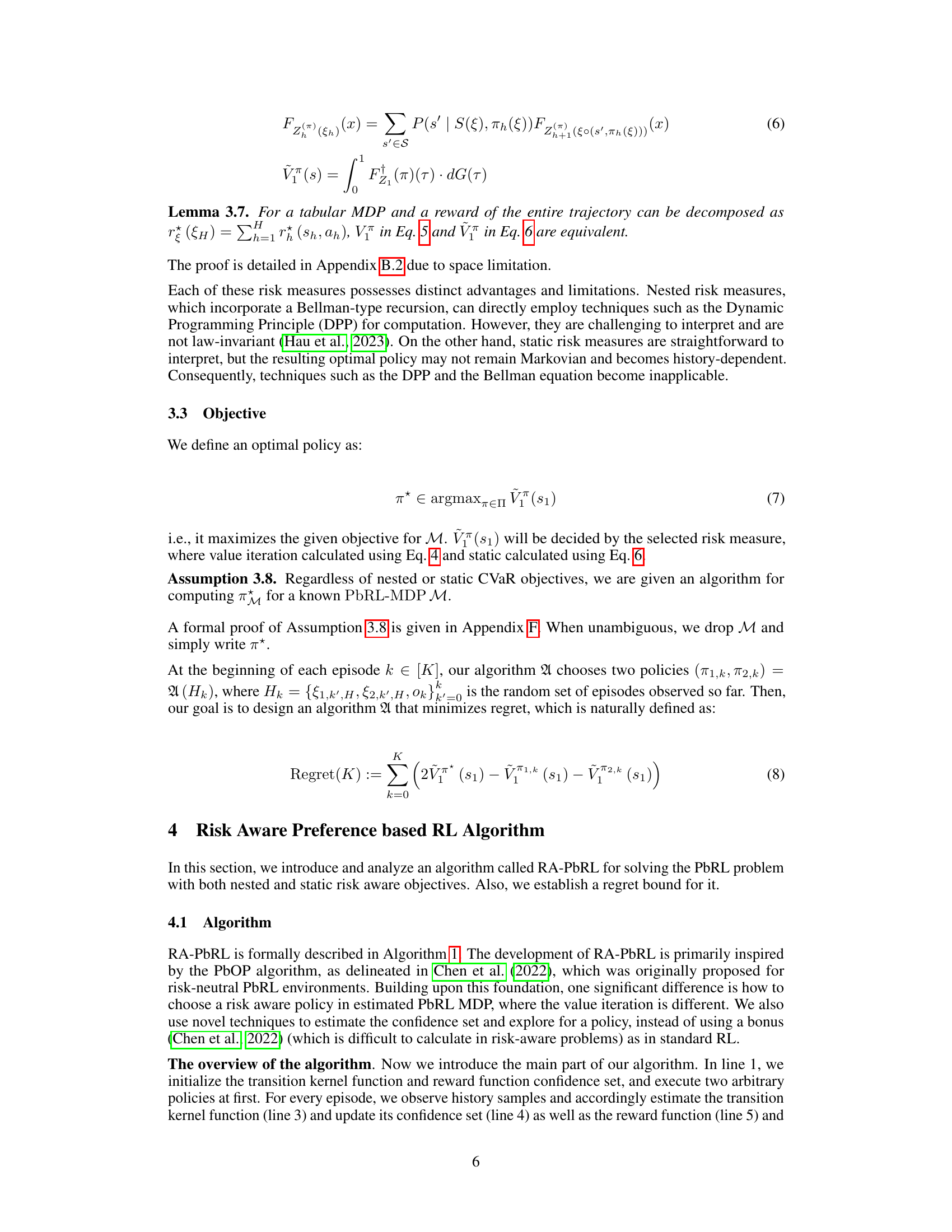

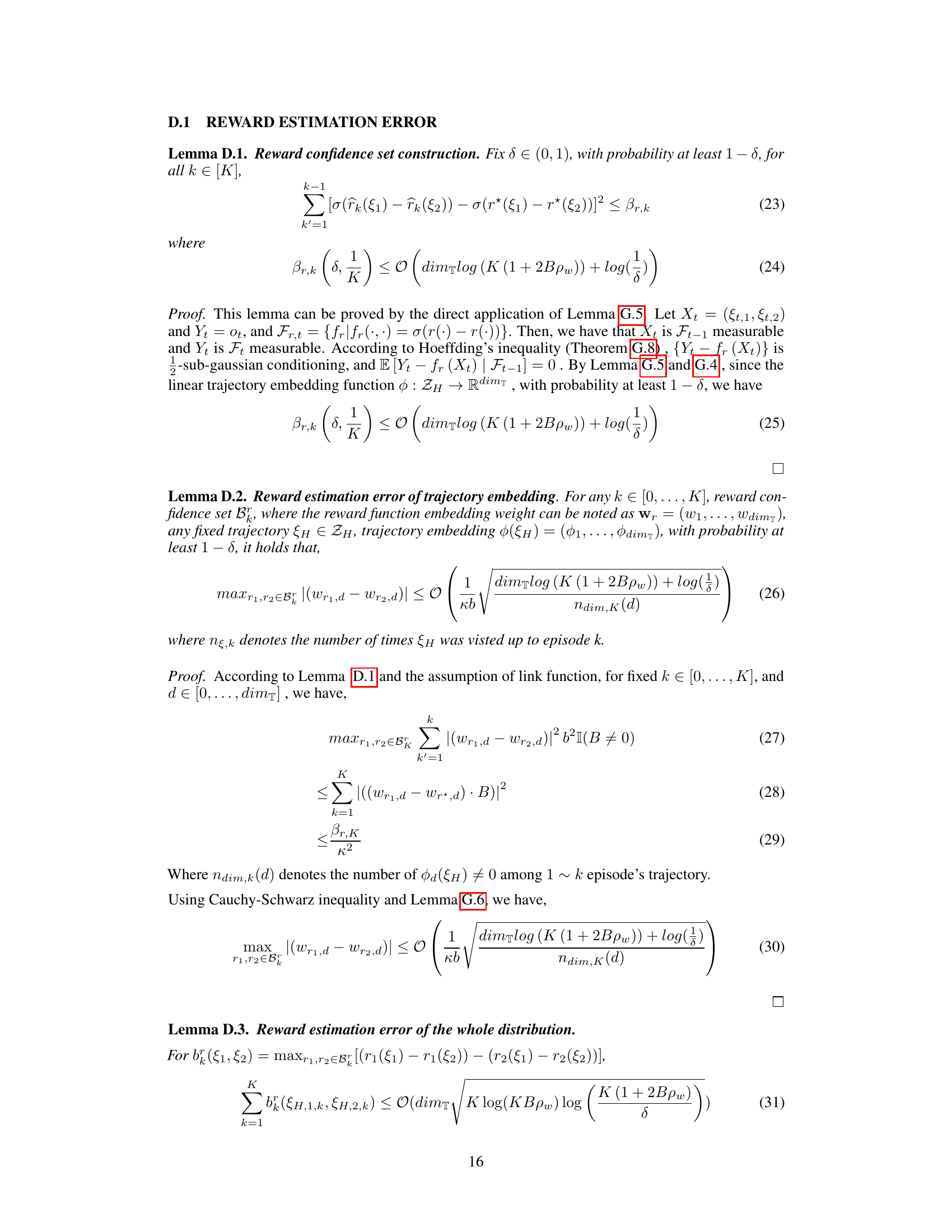

This figure shows the cumulative regret for the static CVaR objective across different values of α (risk aversion levels). The x-axis represents the number of episodes, and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret. Four subplots are presented, each corresponding to a different α value (0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40). Each subplot displays the performance of three algorithms: RA-PbRL (the proposed algorithm), PbOP (a risk-neutral baseline), and ICVaR-RLHF (a risk-aware baseline). The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals. The figure demonstrates that RA-PbRL generally exhibits lower regret than the baseline methods across various levels of risk aversion.

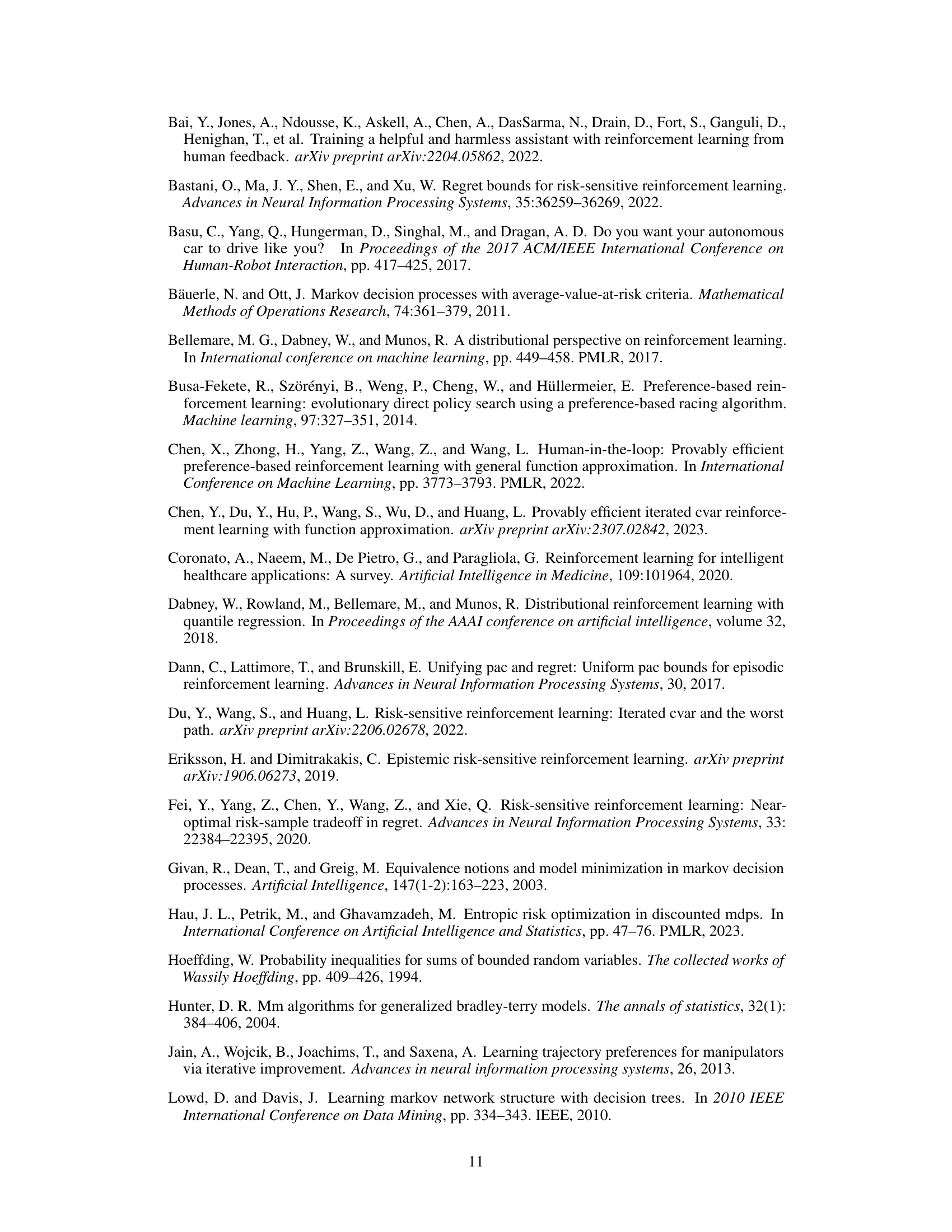

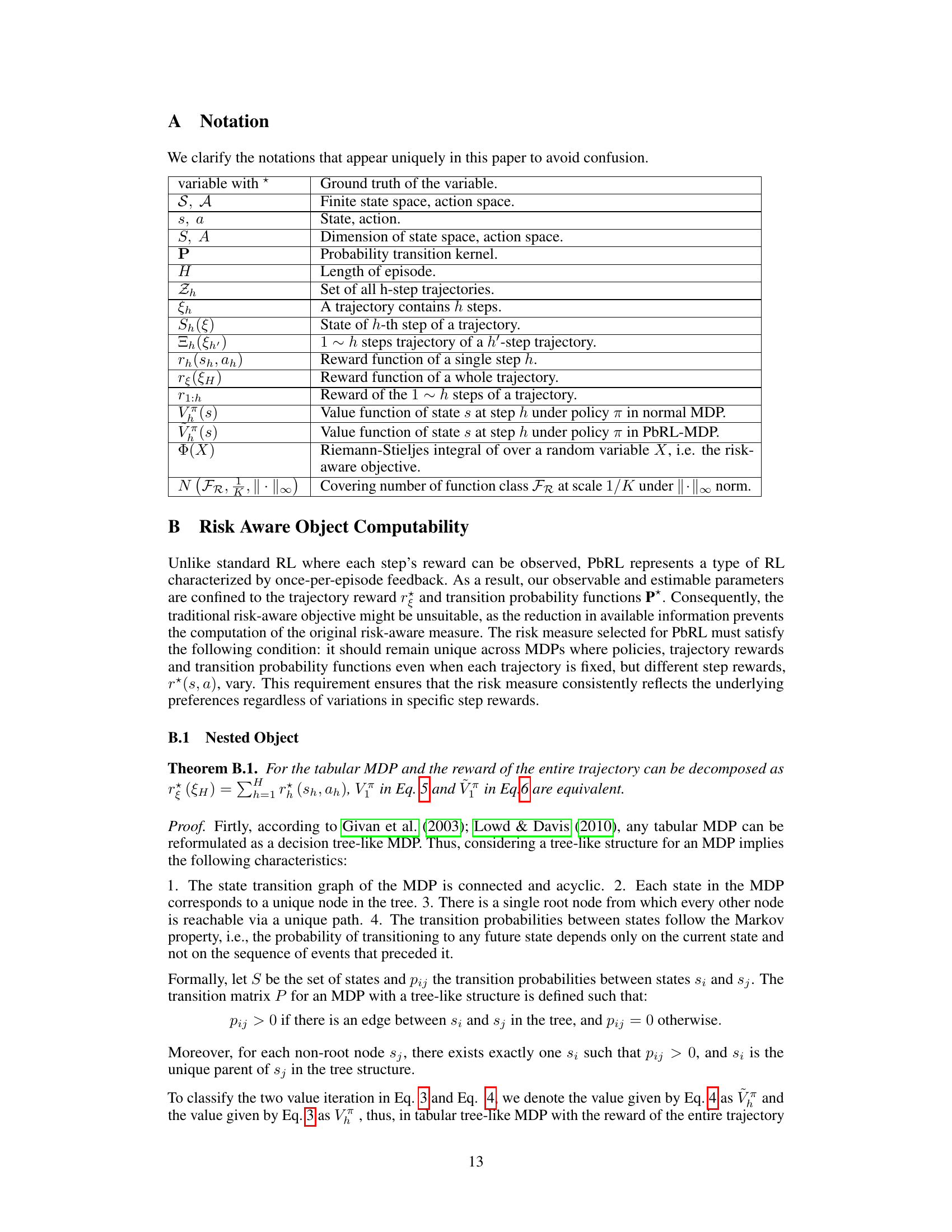

This table lists notations used in the paper. It defines various symbols used to represent concepts like ground truth variables, state and action spaces, probability transition kernels, trajectories, reward functions, value functions, risk-aware objectives, and covering numbers. These notations help to clarify and concisely express the mathematical formulations presented throughout the paper.

In-depth insights#

Risk-Aware PbRL#

Risk-aware preference-based reinforcement learning (PbRL) addresses a critical gap in traditional PbRL, which predominantly focuses on maximizing average reward without considering risk. Risk-aware PbRL aims to optimize policies that not only achieve high rewards but also mitigate potential risks, making it particularly suitable for safety-critical applications like autonomous driving and healthcare. This is achieved by incorporating risk-sensitive objectives into the PbRL framework, which differ from standard RL due to the one-episode-feedback nature of preferences. The core challenge lies in defining and efficiently computing risk-aware measures for trajectory preferences, given that standard risk measures in RL rely on per-step rewards. This necessitates the development of novel algorithms that account for the unique properties of PbRL while incorporating risk considerations. The theoretical analysis of regret bounds is crucial for proving the efficiency of any proposed risk-aware PbRL algorithm. Furthermore, empirical evaluations are vital to validate the effectiveness of these methods in real-world scenarios. The development of risk-aware PbRL opens up exciting opportunities in various domains, advancing the capabilities and safety of reinforcement learning agents.

Quantile Risk#

Quantile risk, in the context of risk-aware reinforcement learning, offers a flexible and robust approach to managing uncertainty. Unlike traditional risk measures focusing on the average outcome, quantile risk directly targets specific points in the reward distribution. This allows for a more nuanced approach to risk management, enabling agents to balance risk aversion with reward maximization. For example, one could prioritize minimizing the worst-case scenario (a high quantile) while still aiming for reasonable average performance. The choice of quantile(s) to focus on determines the level of risk aversion. Moreover, quantile risk is particularly well-suited for reinforcement learning settings, where the reward is often uncertain due to stochastic transitions and imperfect model knowledge. By analyzing different quantiles, an agent can better understand the range of potential outcomes and make more informed decisions. In preference-based reinforcement learning (PbRL), where rewards are implicitly defined via preferences over trajectories, quantile risk offers a powerful tool to ensure safer and more robust behavior by focusing on minimizing the risk associated with the lower quantiles of the trajectory reward distribution.

RA-PbRL Algorithm#

The heading ‘RA-PbRL Algorithm’ suggests a core contribution of the research paper: a novel algorithm for risk-aware preference-based reinforcement learning. The algorithm likely integrates risk-sensitive measures (like CVaR) into the preference-based RL framework. This is a significant advancement because traditional PbRL often overlooks risk, which is crucial in real-world applications where safety and reliability are paramount. RA-PbRL likely addresses the challenge of learning from preferences rather than explicit rewards, while simultaneously considering the risk associated with different actions. This likely involves a sophisticated approach to balancing exploration and exploitation, potentially using techniques like Thompson sampling or upper confidence bounds. The paper probably presents theoretical analysis demonstrating the algorithm’s efficiency and perhaps regret bounds, showcasing its convergence properties. A key aspect likely explored is the algorithm’s ability to handle non-Markovian reward models, which are common in the preference-based setting. The empirical evaluation might show the algorithm’s superiority over risk-neutral baselines, highlighting its practical benefits. The effectiveness of RA-PbRL in various real-world scenarios (like robotics or healthcare) is likely demonstrated.

Regret Analysis#

A regret analysis in a reinforcement learning context evaluates the difference between an agent’s cumulative performance and the optimal performance achievable over a given timeframe. In preference-based reinforcement learning (PbRL), where rewards are implicitly defined through pairwise trajectory comparisons, the regret analysis becomes particularly crucial. A key focus is on demonstrating that the regret grows sublinearly with the number of episodes, indicating that the agent’s policy converges towards optimality. This requires carefully considering the complexities of PbRL, including the non-Markovian nature of the reward signal (as rewards are trajectory-based, not step-based) and the uncertainty in preference feedback. The analysis would likely involve bounding the estimation errors of trajectory embeddings and reward functions, then relating these errors to the agent’s regret. Different risk-averse measures (e.g., nested and static quantile risk) would yield different regret bounds, requiring distinct theoretical analyses to accommodate their specific properties. Proving sublinear regret for various risk measures is a significant achievement because it offers strong theoretical evidence for the algorithm’s efficiency and convergence properties. Tight lower bounds are also important to establish the fundamental limits of performance for the studied algorithm, under specific conditions.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion mentions several promising avenues for future research. Extending the framework to handle n-wise comparisons, instead of just pairwise preferences, would significantly increase the algorithm’s robustness and applicability. Relaxing the linearity assumption of the reward function is another crucial area, opening the door to more complex and realistic scenarios. Investigating tighter theoretical bounds for regret, bridging the gap between upper and lower bounds, will enhance the algorithm’s theoretical foundation. Finally, empirical validation in more diverse and complex environments, beyond those tested, will provide valuable insights into the algorithm’s practical performance and limitations. Addressing these key areas will ultimately lead to a more robust, versatile, and impactful risk-aware preference-based reinforcement learning framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows the cumulative regret for static CVaR for four different values of α (0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40). Each subplot represents a different α value and shows the performance of three algorithms: RA-PbRL, PbOP, and ICVaR-RLHF. The y-axis represents the cumulative regret, and the x-axis represents the number of episodes. The shaded regions around the lines represent confidence intervals. The figure demonstrates the performance of the RA-PbRL algorithm compared to existing methods across different levels of risk aversion (represented by α).

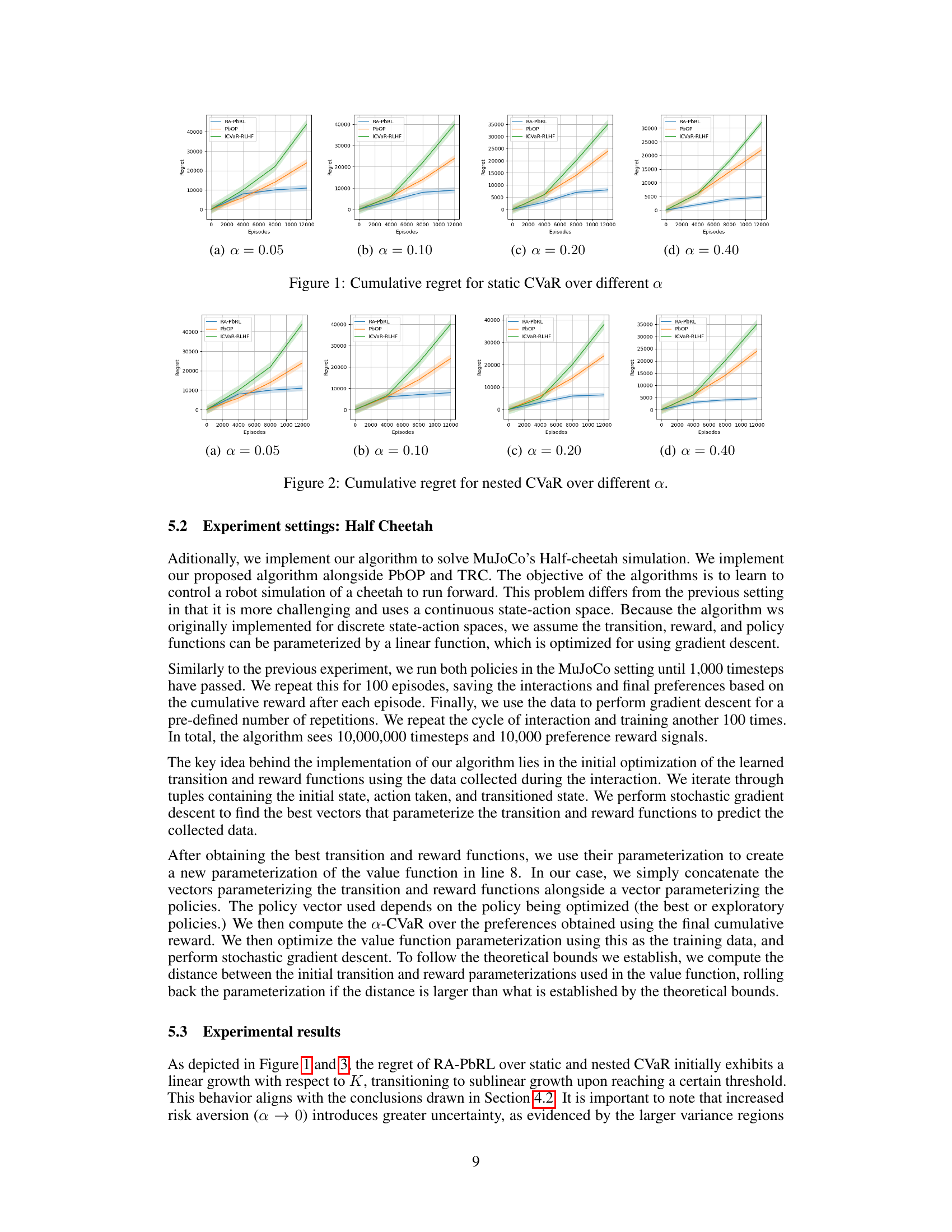

This figure displays the cumulative regret for static CVaR across four different risk aversion levels (α = 0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40) in the MuJoCo Half-Cheetah environment. It compares the performance of the proposed RA-PbRL algorithm against two baseline algorithms: PbOP and ICVaR-RLHF. The x-axis represents the timestep, while the y-axis shows the cumulative regret. The plot illustrates how the cumulative regret changes over time for each algorithm under various risk aversion settings.

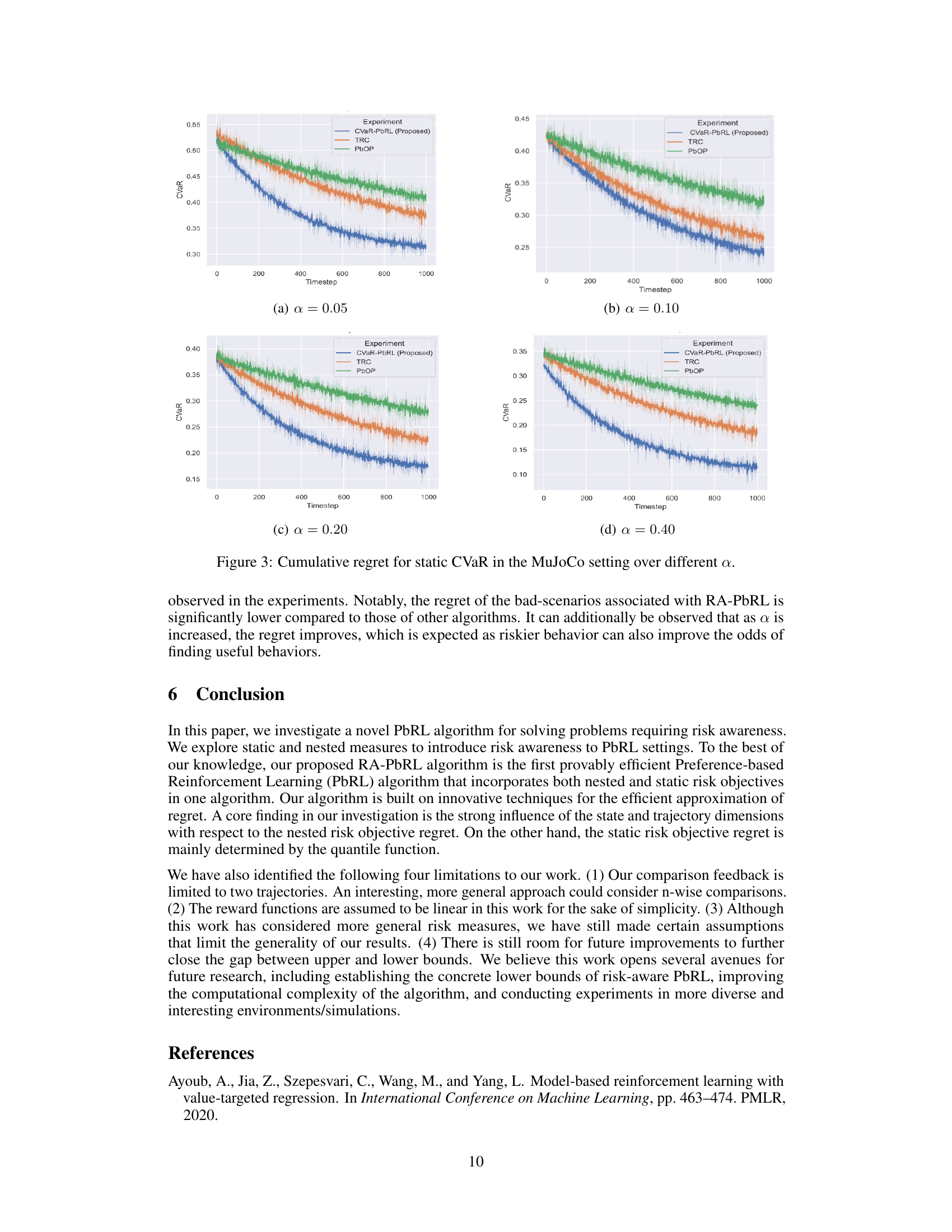

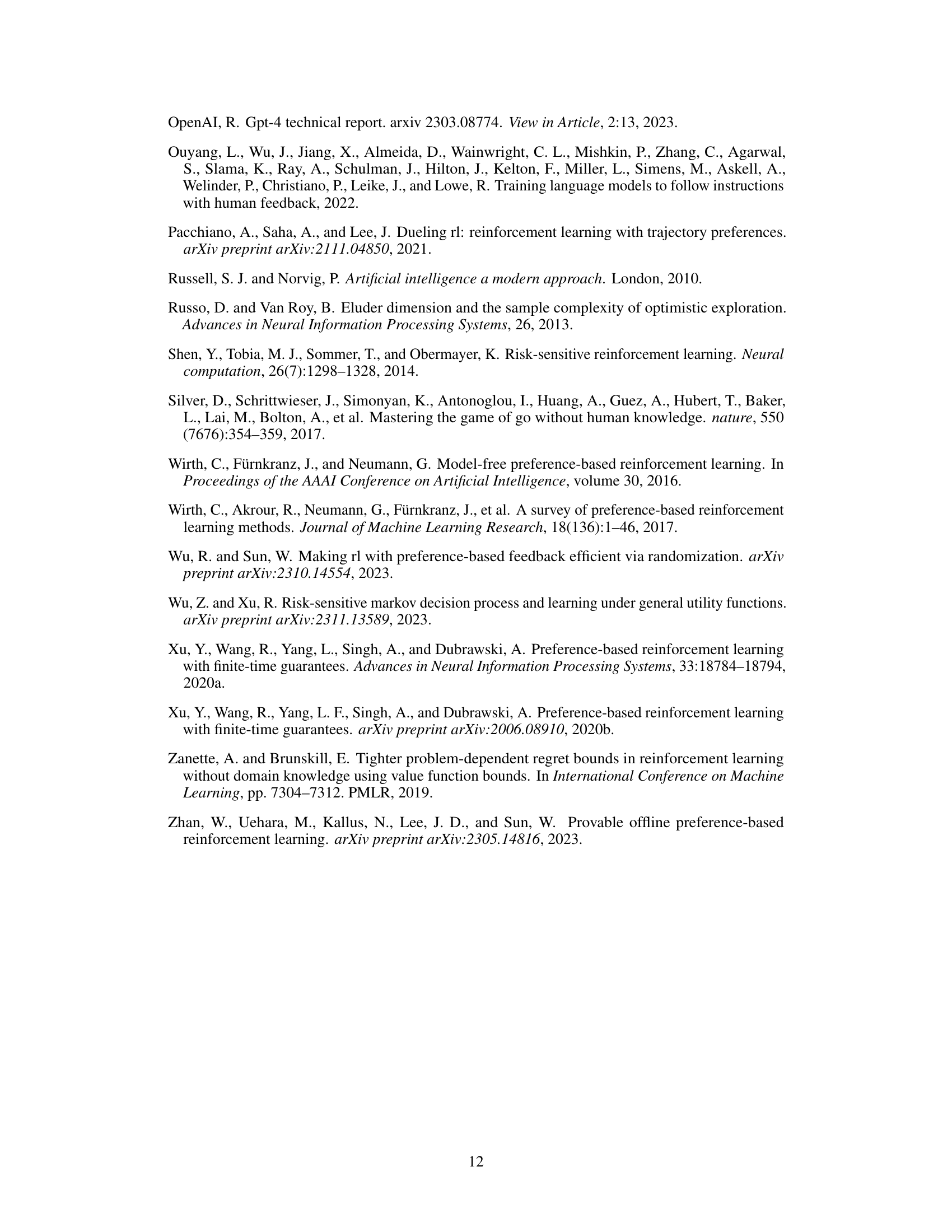

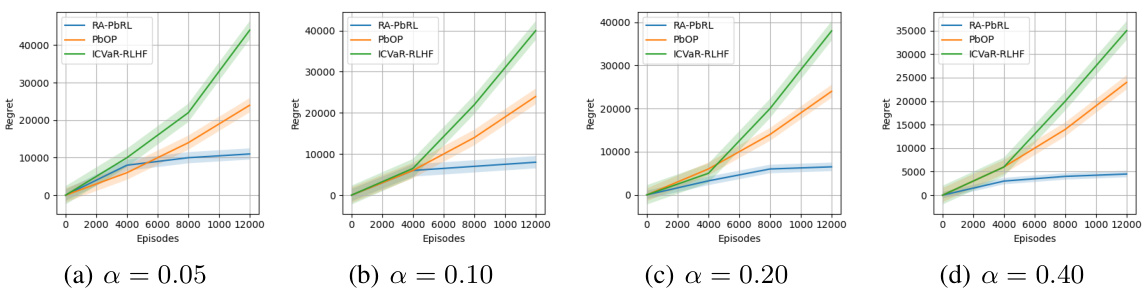

This figure shows a comparison of cumulative regret between two policies (policy A and policy B) under different risk levels (α). The MDP instance is designed to have identical reward distributions for both policies, leading to similar preferences but differing risk profiles. The policies share the same actions in the first two steps but differ in the third step. This figure demonstrates the impact of the choice of risk measure (nested vs. static CVaR) on the overall cumulative regret. The nested CVaR and static CVaR methods are shown for different α values (risk aversion levels).

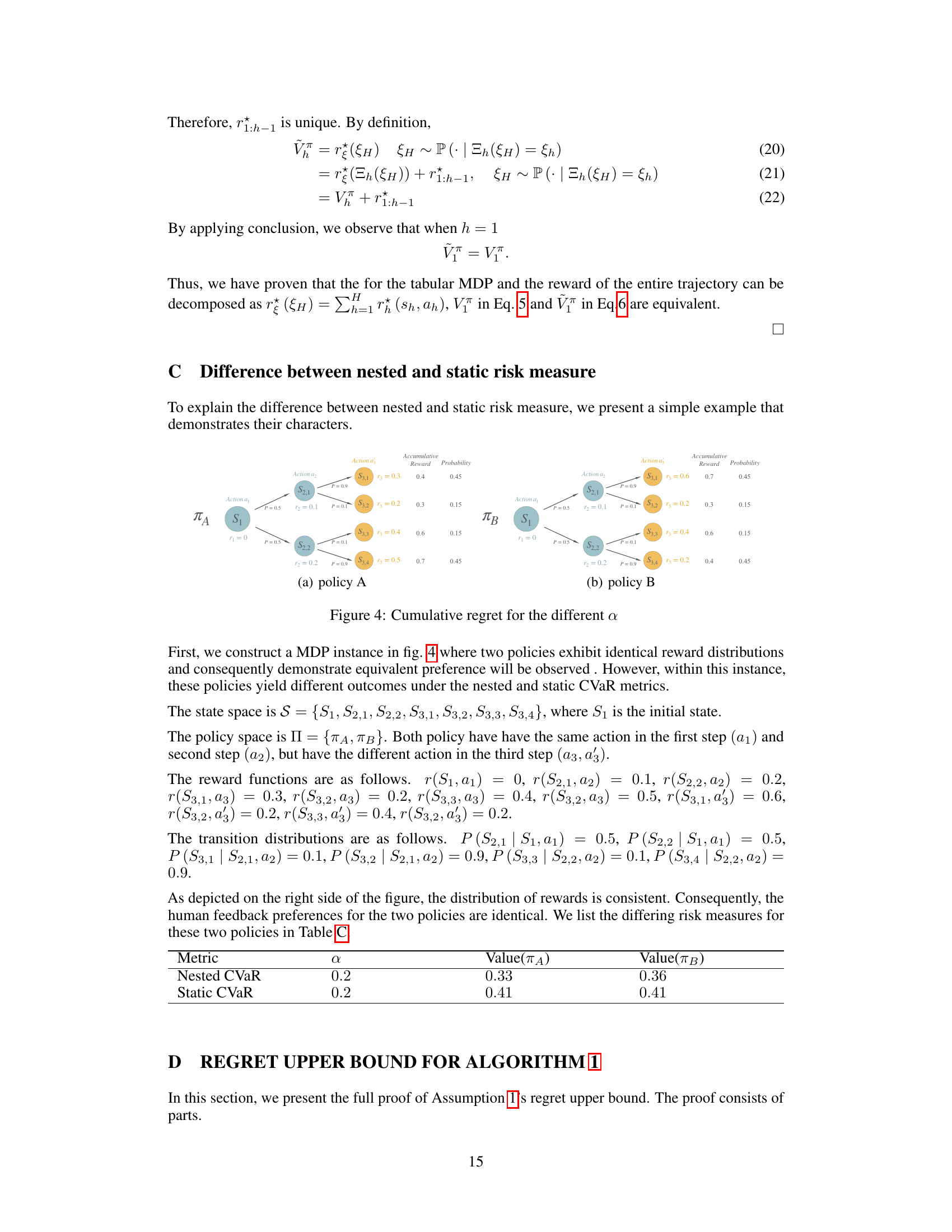

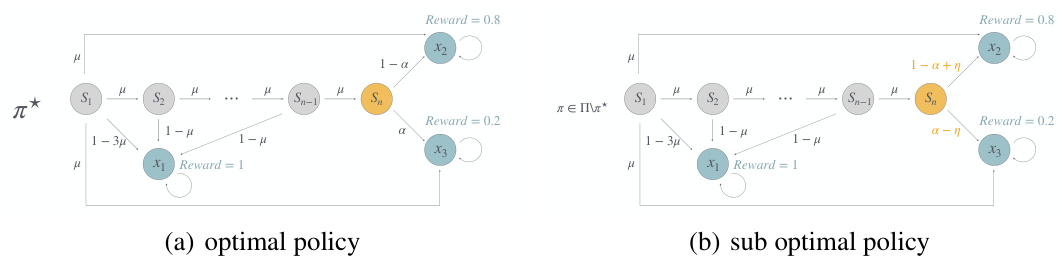

This figure presents two scenarios, (a) optimal policy and (b) suboptimal policy, to illustrate a hard-to-learn instance for the nested CVaR RA-PbRL algorithm. The instance features a state space with absorbing states X1, X2, and X3 and a set of intermediate states S1…Sn. The transition probabilities and rewards are designed such that the optimal policy leads to higher cumulative rewards, while the suboptimal policy yields lower rewards. The difference highlights the challenge in achieving optimal risk-averse policies within the one-episode reward setting of PbRL.

This figure presents a hard-to-learn instance for the nested CVaR objective. In this instance, two policies exhibit almost identical reward distributions and, consequently, similar preferences. However, the nested CVaR metric assigns significantly different values to these policies, demonstrating that nested CVaR risk is sensitive to the order of states and actions.

Full paper#