↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The brain’s ability to create and use cognitive maps for spatial navigation has long been a topic of interest in neuroscience. Understanding how this is achieved computationally has presented a significant challenge. This study introduces a new model that addresses this challenge. The model proposes that spatial information is encoded using a combination of optimality principles and an algebraic framework, allowing for efficient and robust computation. The researchers suggest that spatial positions are represented using residue number systems and individual modules in the brain correspond to grid cell modules in the entorhinal cortex. The study uses computational modelling to demonstrate that the model exhibits favorable properties, including superlinear scaling, robust error correction, and hexagonal encoding of spatial positions.

The model provides a more comprehensive understanding of how the brain achieves efficient computation in complex spatial tasks. The findings also offer several testable experimental predictions that could help to further refine the model and deepen our understanding of how the brain works. Importantly, the model provides insight into how more general compositional computations can occur in the hippocampal formation, suggesting implications for other cognitive functions that might also rely on this type of mechanism. This research advances our understanding of how the brain represents and manipulates spatial information, which is important for a wide range of cognitive functions and has implications for the development of more realistic and effective AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers studying spatial memory and navigation, grid cells, and hippocampal function. It offers a novel model integrating optimality principles with algebraic computations, opening new avenues for testing experimental predictions and developing more biologically plausible computational models of the brain. Its findings have implications for broader fields like AI, particularly in developing more efficient and robust systems for spatial representation and navigation.

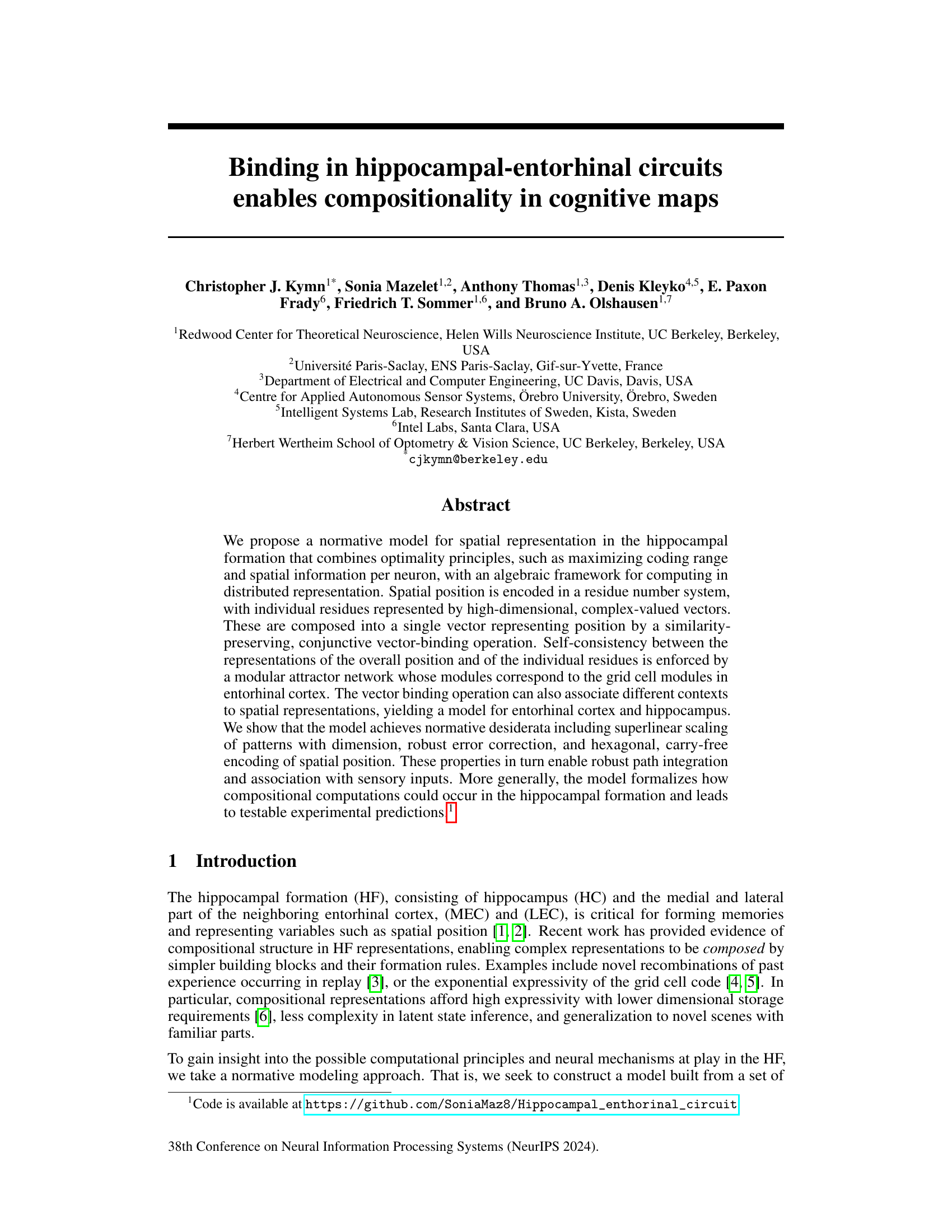

Visual Insights#

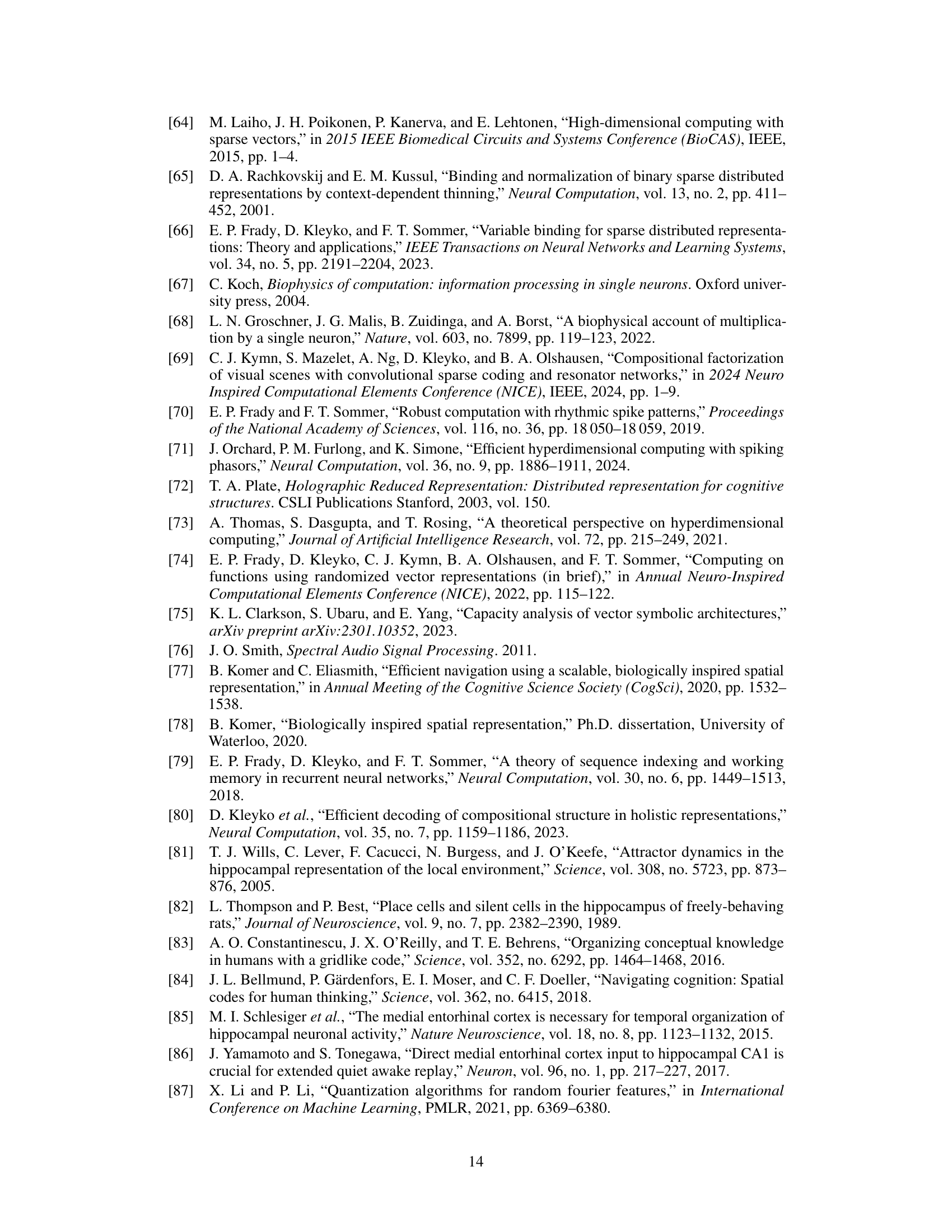

This figure shows a schematic of the proposed attractor model for the hippocampal formation. It illustrates the interaction between the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC), hippocampus (HC), and lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC). MEC grid modules (Gi) represent individual residues (gi) of a spatial position, with a context label (c). The hippocampus (HC) stores the contextualized spatial position (p). Binding (⋅) combines these residues into the overall position. The model shows how velocity (q(v)) influences path integration and sensory inputs (s) from LEC interact with the hippocampal representation.

In-depth insights#

Modular Attractor Nets#

Modular attractor networks represent a significant advancement in neural network design, particularly within the context of spatial representation and cognitive mapping. The modularity allows for scalable high-dimensional encoding, handling complex information efficiently. Each module, often inspired by biological grid cell structures, processes a component of the overall representation (e.g., a specific residue in a residue number system). Similarity-preserving vector binding then integrates these modular outputs into a unified spatial representation. This approach offers robust error correction, crucial for real-world applications where noise is inevitable. The use of attractor dynamics within each module enhances noise resistance and enables stable computations, providing a pathway towards implementing continuous path integration. The combination of optimality principles (e.g., maximizing coding range and information efficiency) and an algebraic framework makes this approach elegant and theoretically grounded. However, challenges include fully mapping these modular attractor networks to specific neurobiological structures, and the implications of this approach for learning and generalization remain important avenues for future investigation.

RNS Compositionality#

The concept of “RNS Compositionality” centers on leveraging the Residue Number System (RNS) to create compositional representations in neural networks. RNS excels at representing high-dimensional data efficiently, especially in scenarios requiring high resolution and robustness. By encoding individual spatial dimensions or features as residues and binding them via vector multiplication, the model achieves compositionality: a complex representation is built from simpler, orthogonal components. This approach offers benefits including superlinear scaling (coding range increases exponentially with the number of RNS modules), robust error correction (inherent to RNS), and carry-free arithmetic, crucial for path integration and other computations. The modular nature of the RNS representation maps elegantly to the modular architecture observed in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Overall, RNS compositionality provides a theoretical framework for understanding how the brain might perform complex spatial computations efficiently and robustly, offering a unique perspective on neural coding and binding.

Hexagonal Encoding#

Hexagonal encoding, in the context of spatial representation in the brain, presents a compelling alternative to traditional Cartesian grid-based systems. Its key advantage lies in its ability to achieve higher spatial resolution and information density with fewer resources. This enhanced efficiency stems from the hexagonal lattice’s inherent properties: it’s the most space-efficient way to tile a plane without gaps, providing a more compact representation of spatial information. This natural hexagonal arrangement aligns well with empirical observations of grid cells’ hexagonal firing patterns in the entorhinal cortex. The shift from a square to hexagonal grid reduces redundancy in the code, thus improving data efficiency and robustness to noise. However, implementing hexagonal encoding using a residue number system (RNS) faces challenges. The standard RNS relies on Cartesian coordinates, and translating it to hexagonal coordinates requires careful design to maintain the RNS’s carry-free arithmetic. The authors address this challenge by introducing a novel approach combining the 2D hexagonal grid with a 3D frame, facilitating carry-free computations. This demonstrates a significant step toward integrating the efficiency and biological plausibility of hexagonal spatial coding into computational models.

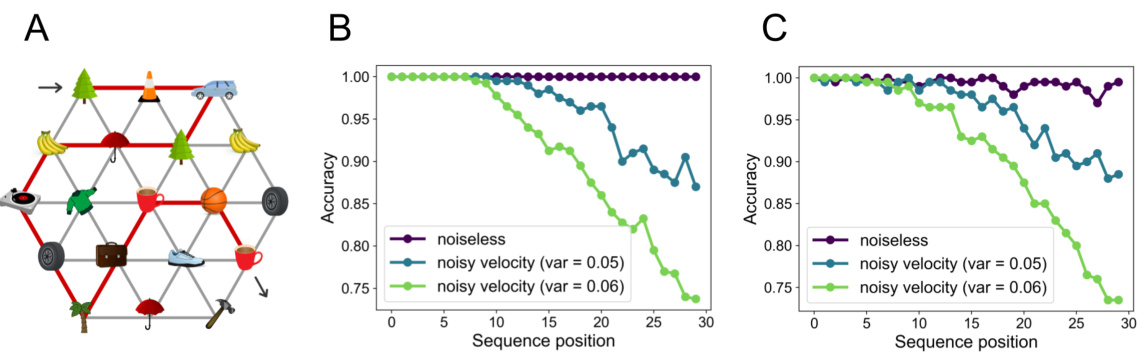

Path Integration Test#

A path integration test for a model of hippocampal-entorhinal spatial representation would rigorously assess its ability to accurately track and predict an agent’s location over time, solely based on movement information (e.g. velocity). Successful path integration suggests the model accurately accumulates movement vectors, overcoming inherent noise and drift. Key aspects of such a test would involve simulating realistic trajectories (possibly incorporating turns and pauses) and evaluating the model’s accumulated position error. A crucial aspect to assess would be the effect of noise on accumulated error, determining the robustness and limits of the model’s accuracy. Comparing the model’s predicted trajectory against the ground truth trajectory would reveal crucial information about both its computational accuracy and noise handling capabilities. Furthermore, analyzing the model’s performance across multiple trials with varying noise levels helps establish its overall reliability and potential limitations. Visualizations of trajectories and accumulated errors (quantified metrics) are important for evaluating model performance. Ideally, results would show that while noise impacts accuracy, a sufficiently robust model will largely maintain accuracy over realistic movement durations, demonstrating reliable path integration which is a critical function for spatial navigation.

Sensory Cue Robustness#

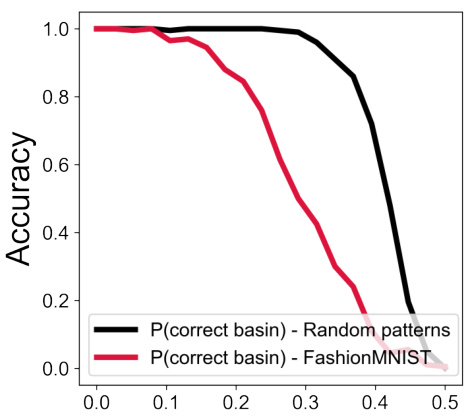

Sensory cue robustness is a critical aspect of any navigation system, especially in biological contexts. A robust system should not be overly sensitive to noise or missing information in sensory inputs. The paper investigates this, examining the model’s resilience to noisy or incomplete sensory information. The results demonstrate a high degree of robustness, suggesting the system can reliably perform path integration even when faced with imperfect sensory cues. This robustness is likely crucial for real-world navigation where sensory information is rarely perfect. The ability to integrate multiple sensory modalities would likely improve robustness further, however, this aspect may require further investigation. Moreover, understanding the limits of this robustness is equally important. Determining the threshold at which sensory noise overwhelms the system will provide valuable insights into the system’s limitations. Further research examining the specific mechanisms behind this robustness, and how it interacts with other cognitive processes, would significantly strengthen the findings and deepen our understanding of navigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

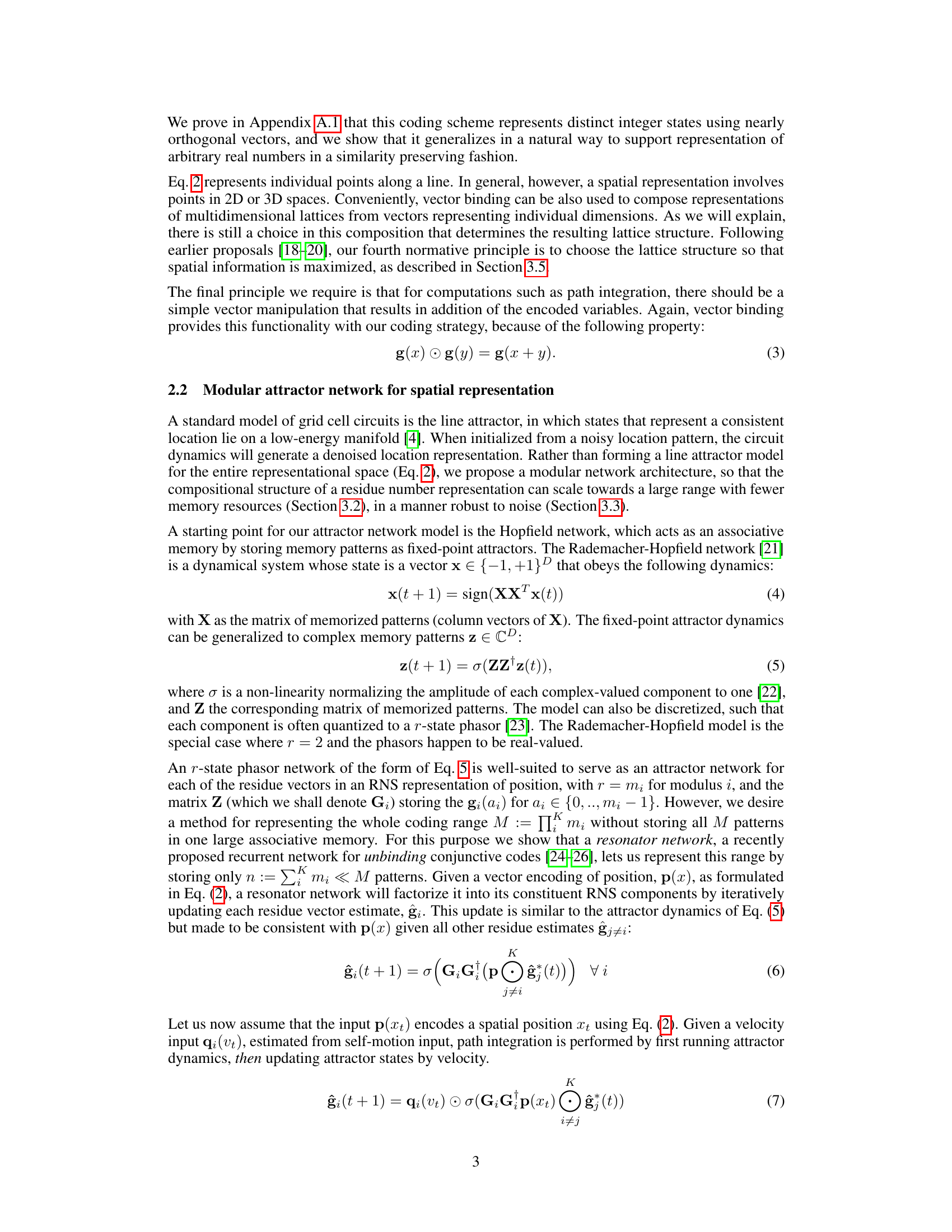

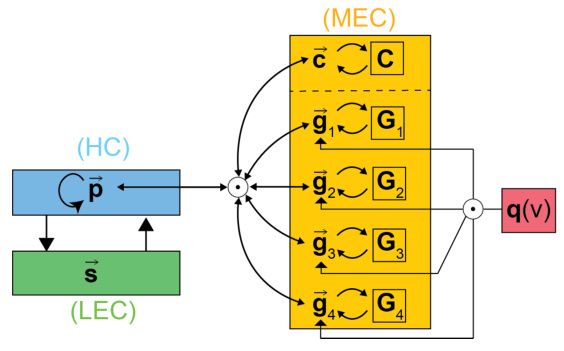

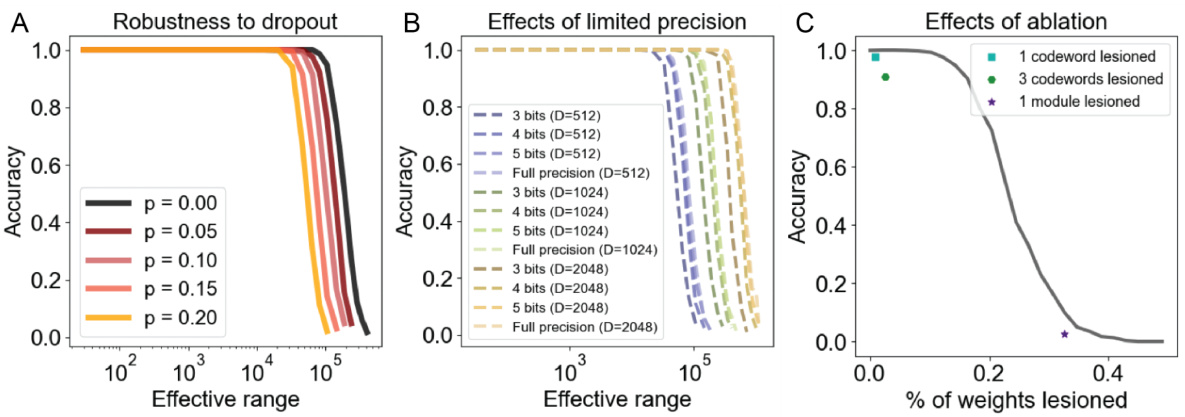

This figure demonstrates the favorable scaling properties of the proposed model for representing space. Panel A shows the exponential growth of the coding range (number of states) with the number of modules (K), reaching a maximum determined by Landau’s function. Panel B illustrates the superlinear scaling relationship between the coding range and vector dimension (D) for different numbers of modules. Panel C shows the superlinear scaling coefficients (αK) for different numbers of modules, highlighting that these values are close to K−1.

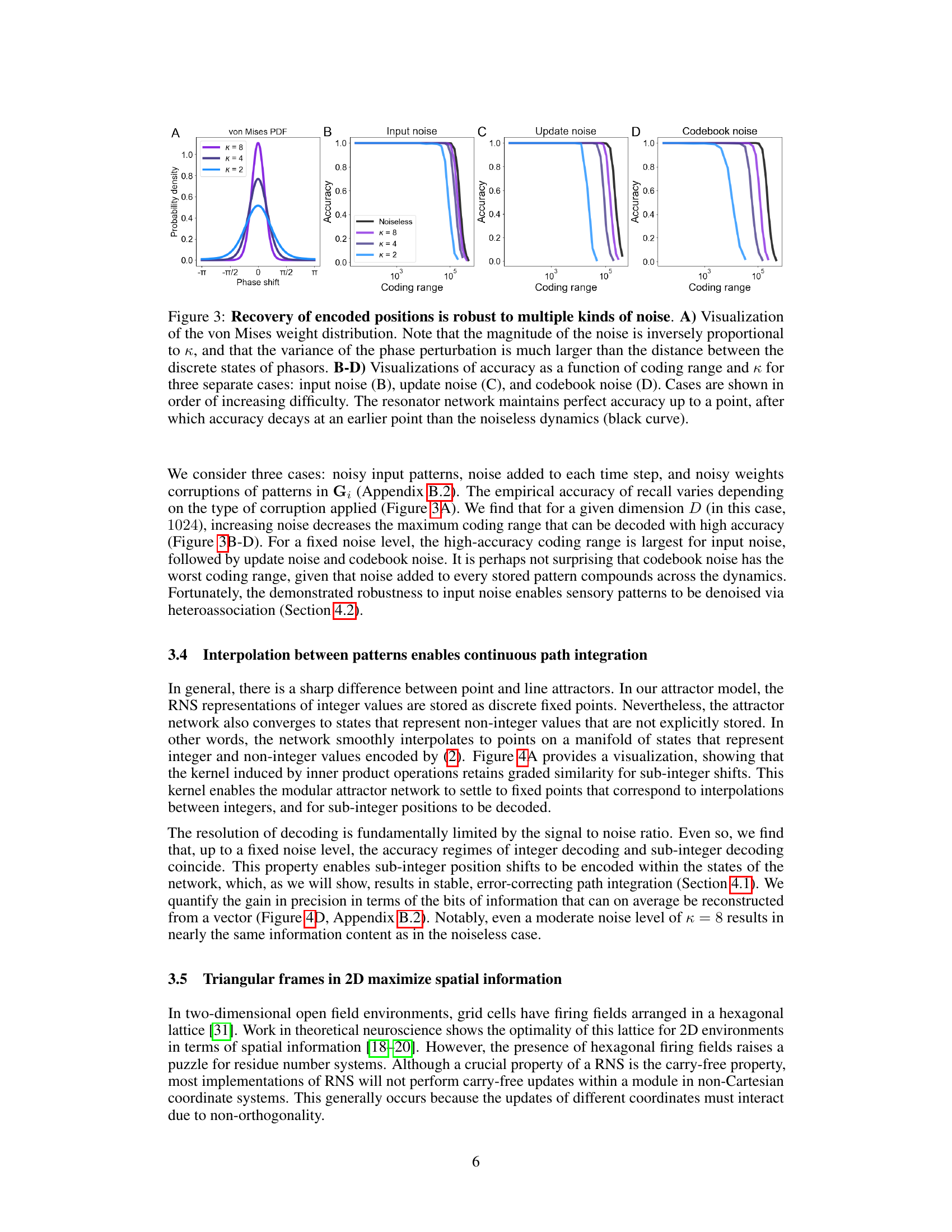

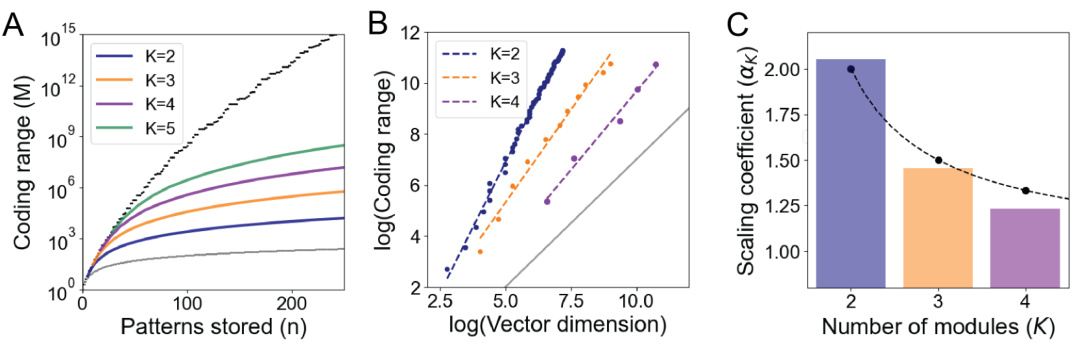

This figure demonstrates the robustness of the proposed attractor network model to various types of noise. Panel A shows the von Mises distribution used to model the noise. Panels B, C, and D illustrate the accuracy of the model in recovering encoded positions across a range of coding ranges and noise levels (parameterized by κ). Different noise types (input, update, and codebook noise) are evaluated, demonstrating that the model remains accurate despite the presence of noise, though performance degrades as the noise level increases.

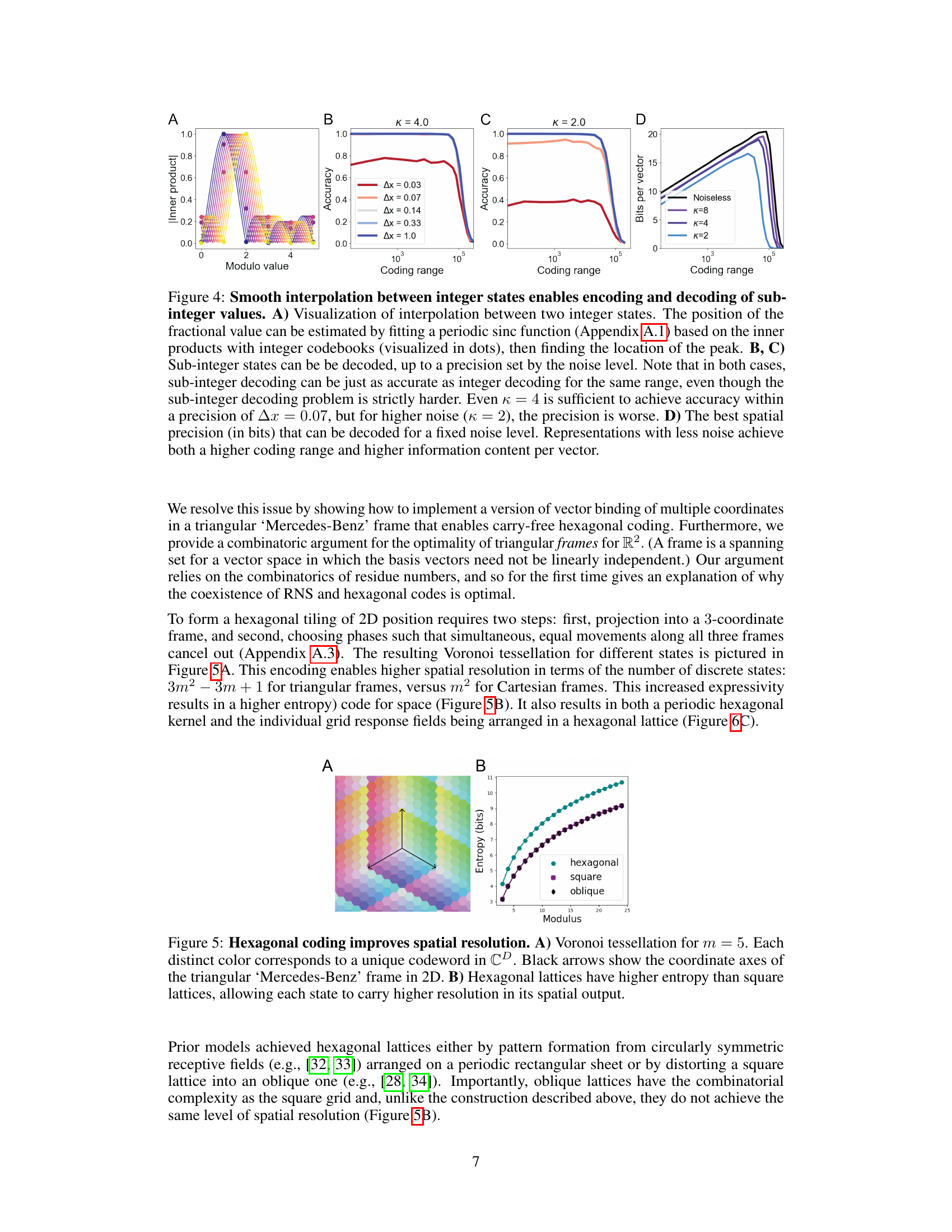

This figure demonstrates the ability of the model to represent and decode sub-integer values, showing that the network smoothly interpolates between integer states. Panel A visualizes this interpolation using a sinc function fit to inner products. Panels B and C show how the accuracy of sub-integer decoding depends on both the coding range and the noise level (κ). Panel D quantifies the information content (in bits) achievable at different noise levels and coding ranges.

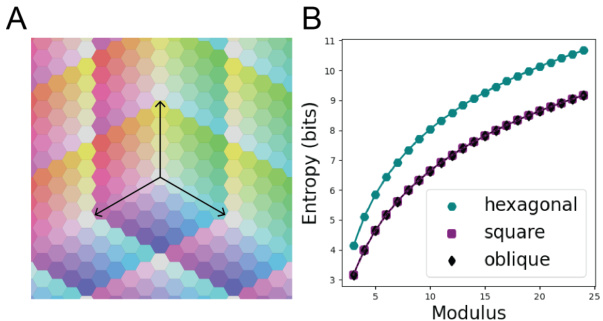

This figure shows that hexagonal lattices provide higher spatial resolution than square or oblique lattices. Panel A shows a Voronoi tessellation for m=5 where each color represents a unique codeword. Black arrows indicate the coordinate axes of the triangular frame in 2D. Panel B shows that hexagonal lattices achieve higher entropy than square or oblique lattices.

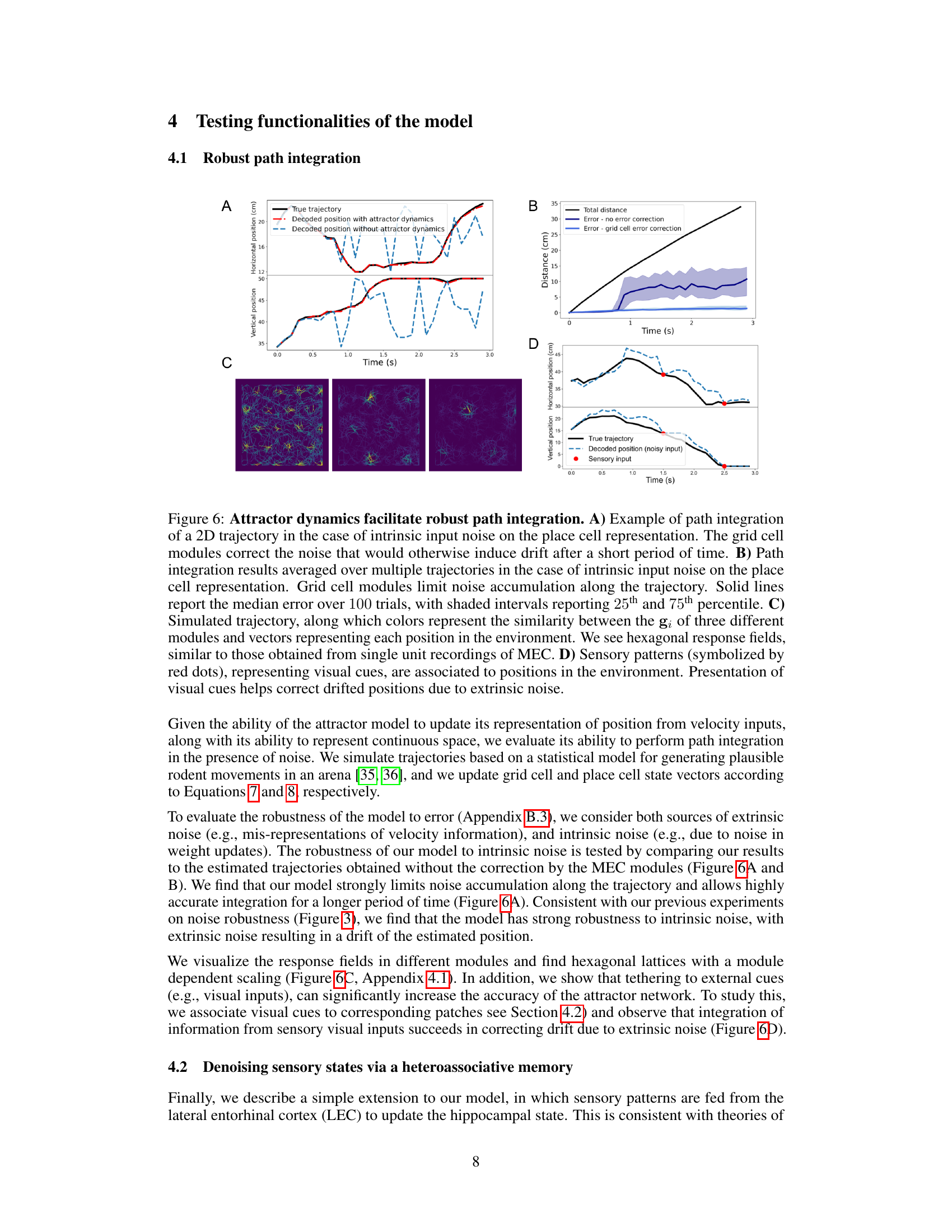

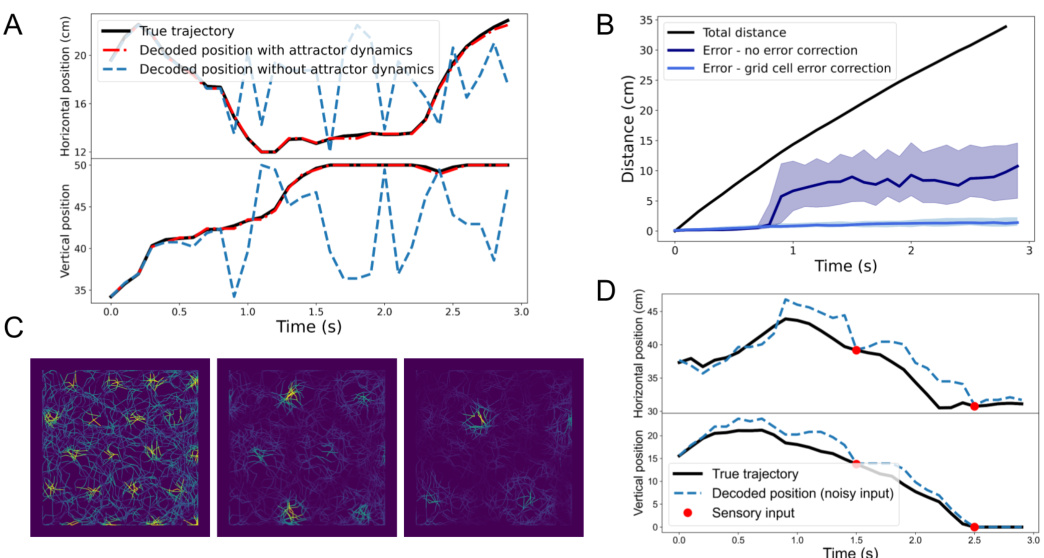

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform path integration in the presence of noise. Panel A shows an example of path integration with intrinsic noise, highlighting how grid cell modules correct for the noise and prevent drift. Panel B shows the average path integration error over multiple trials with and without grid cell error correction, demonstrating the effectiveness of the correction. Panel C visualizes the hexagonal response fields of the grid cell modules, similar to what’s observed experimentally. Finally, Panel D illustrates how sensory input helps to correct for path integration errors caused by extrinsic noise.

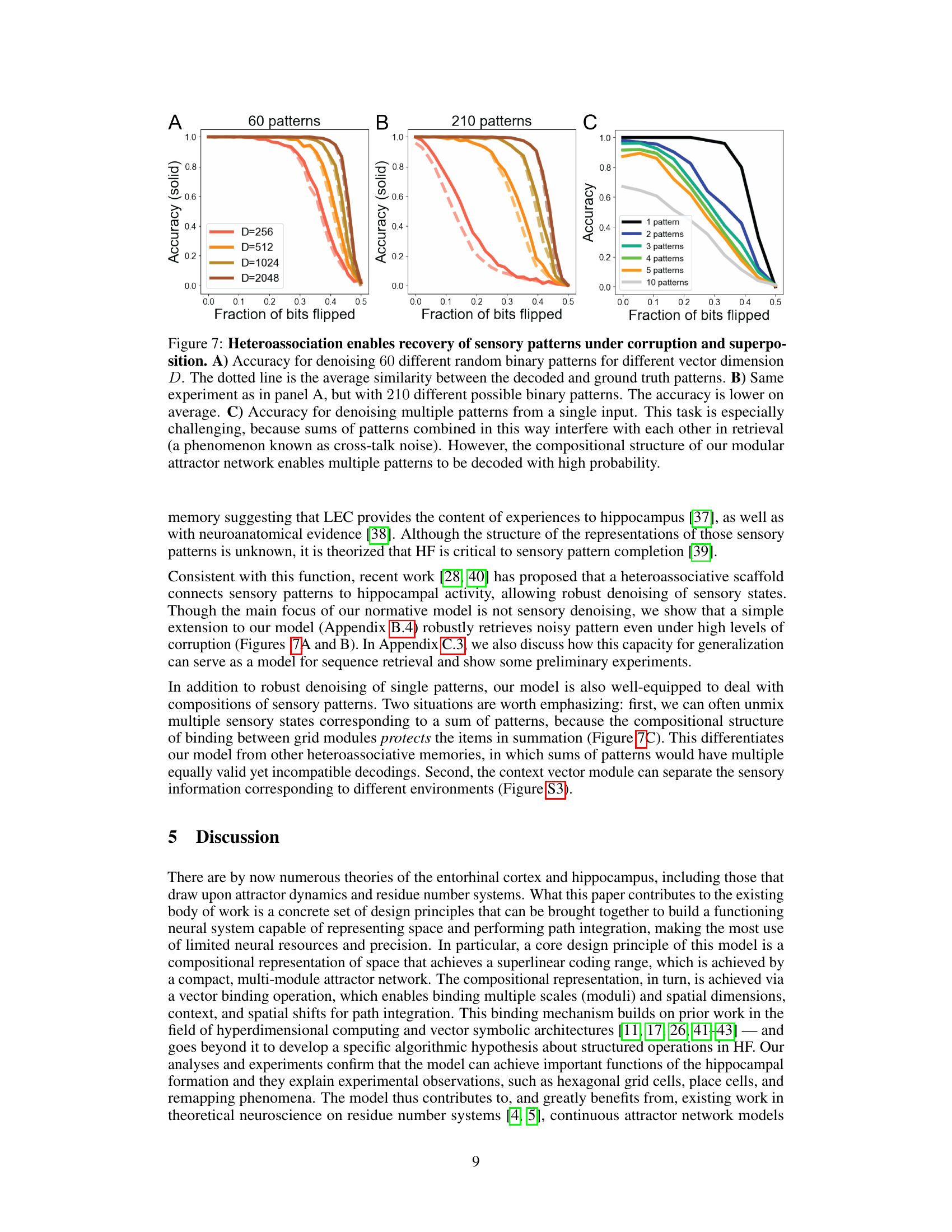

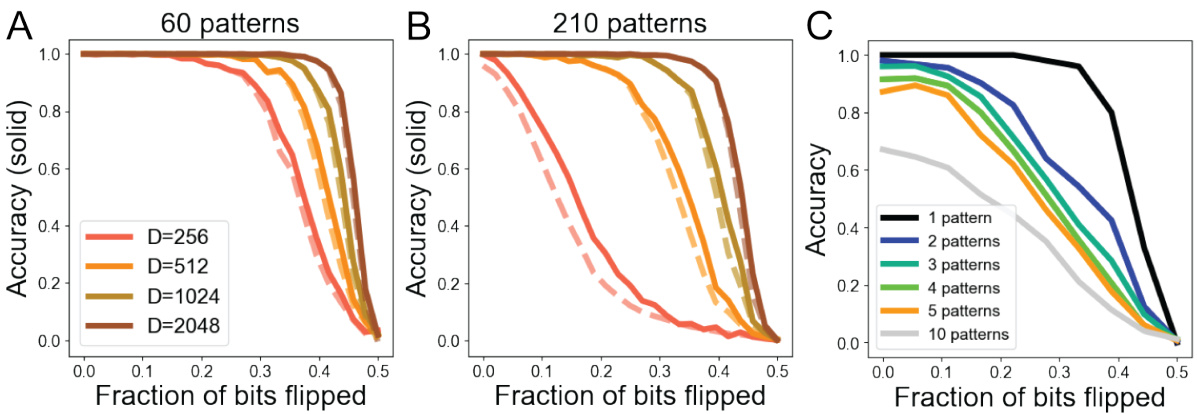

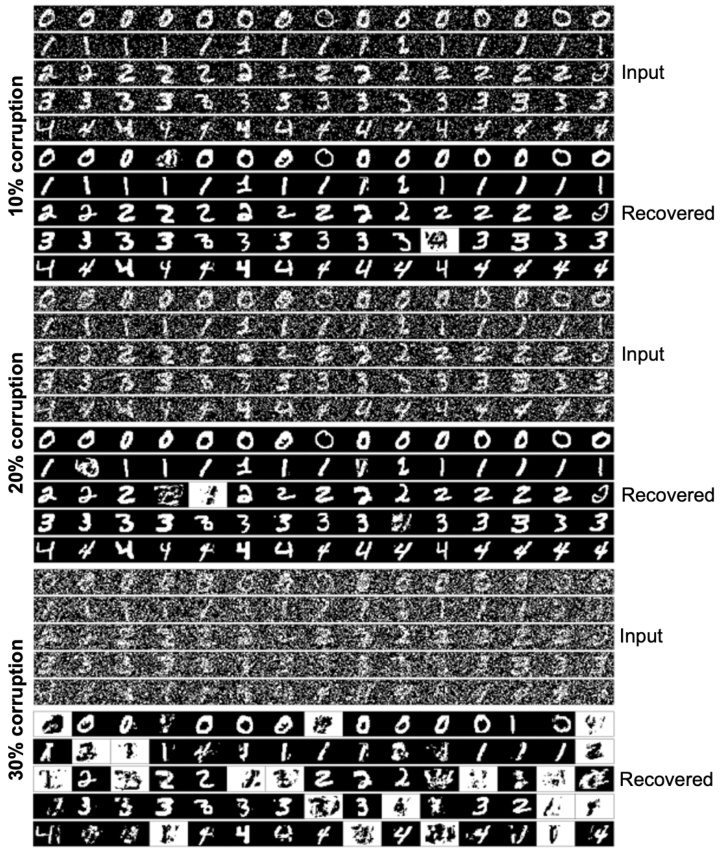

This figure demonstrates the robustness of the heteroassociative memory model to noise and pattern superposition. Panel A shows the accuracy of denoising 60 random binary patterns with varying levels of corruption and different vector dimensions. Panel B repeats the experiment with 210 patterns, showing a decrease in average accuracy. Panel C shows the accuracy when attempting to decode multiple patterns superimposed on a single input, highlighting the model’s ability to handle ‘cross-talk noise’ due to its compositional structure.

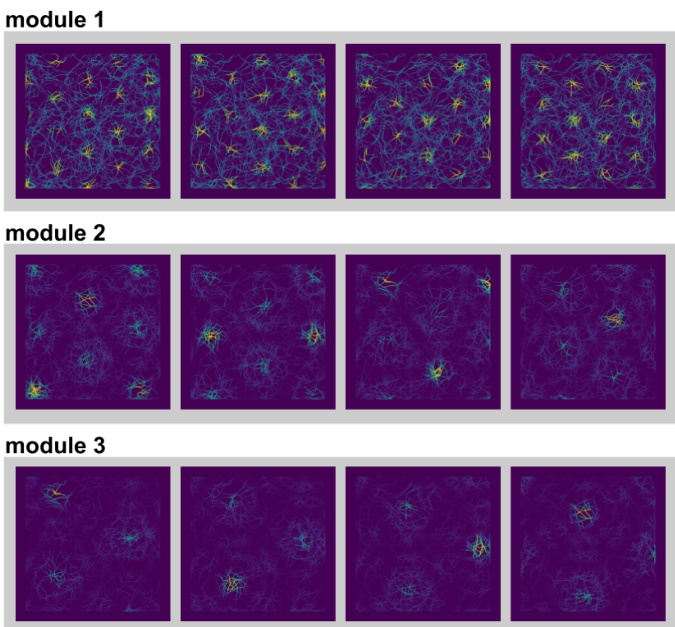

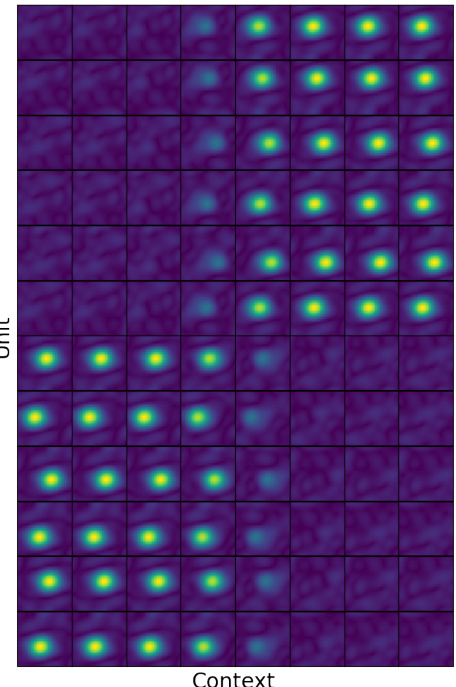

This figure visualizes the response fields of grid cells from different modules in the model. It shows that for a given module, the response fields are translations of each other, meaning that the same pattern is repeated across the spatial field. This supports the model’s representation of space as a modular system.

This figure shows the remapping of place cells in different contexts. The color intensity represents the firing rate of each place cell in each context. The results are consistent with experimental studies of attractor network dynamics in the hippocampus, demonstrating the model’s ability to simulate this complex phenomenon.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform robust path integration in the presence of noise. Panel A shows an example of path integration with intrinsic noise, highlighting how grid cell modules correct for drift. Panel B presents averaged results over multiple trajectories, showing the effectiveness of grid cells in limiting noise accumulation. Panel C visualizes hexagonal response fields, similar to those observed in MEC recordings, along a simulated trajectory. Finally, Panel D illustrates how incorporating sensory cues (visual cues) helps correct for positional drift caused by extrinsic noise.

This figure demonstrates the benefits of combining residue number systems (RNS) with a modular attractor network. Panel A shows that the number of possible encoded states (M) increases exponentially with the number of modules (K), reaching a limit set by Landau’s function. Panel B illustrates that the coding range scales superlinearly with the dimension of the vectors representing each module (D), indicated by the exponent αK which is greater than 1. This superlinear scaling means that a larger coding range can be achieved with a relatively lower-dimensional representation. Panel C further supports the superlinear scaling by showing the relationship between dimension, number of modules, and coding range using a log-log plot.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform sequence retrieval via path integration in a conceptual space. Panel A shows an example of a hexagonal lattice where each node represents a state and sensory observations are associated with those states. Panel B shows the accuracy of retrieving random binary patterns, demonstrating that accuracy decreases as the sequence position increases (with noise). Panel C shows that the model can successfully infer the context tag when retrieving the sequence.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform robust path integration, even in the presence of noise. Panel A shows an example trajectory with and without the attractor dynamics, highlighting the noise correction provided by the grid cells. Panel B quantifies this effect by averaging over multiple trials and showing median error with 25th and 75th percentiles. Panel C visualizes the hexagonal response fields of grid cells, demonstrating that the model replicates experimental observations. Panel D illustrates how sensory cues can improve the accuracy of path integration.

Full paper#