↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Multi-task Bayesian bandit algorithms optimize decisions across multiple related tasks by sharing information. Existing algorithms, like HierTS, offered regret bounds that were not optimal. The problem is that these existing algorithms do not sufficiently exploit shared information between the tasks and are thus not efficient in practice. This paper addresses this issue by refining the analysis of existing algorithms and proposing a novel algorithm, HierBayesUCB, designed for the multi-task setting.

This paper improves existing Bayes regret bounds, particularly for HierTS (reducing the bound from O(m√n log n log (mn)) to O(m√n log n) for infinite action settings). For finite action settings, it introduces HierBayesUCB, achieving a logarithmic regret bound. The algorithms are then extended to combinatorial semi-bandit settings, providing improved bounds. Empirical results validate the theoretical findings, showcasing the efficiency and effectiveness of these improved algorithms. The results have important implications for applications using multi-task bandit learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multi-task Bayesian bandit algorithms because it provides improved theoretical guarantees and proposes novel algorithms with tighter regret bounds. This advancement is relevant to various applications like recommendation systems and online advertising, improving efficiency and performance. The findings also open doors for further research into concurrent settings and more general multi-task bandit problems, advancing the field.

Visual Insights#

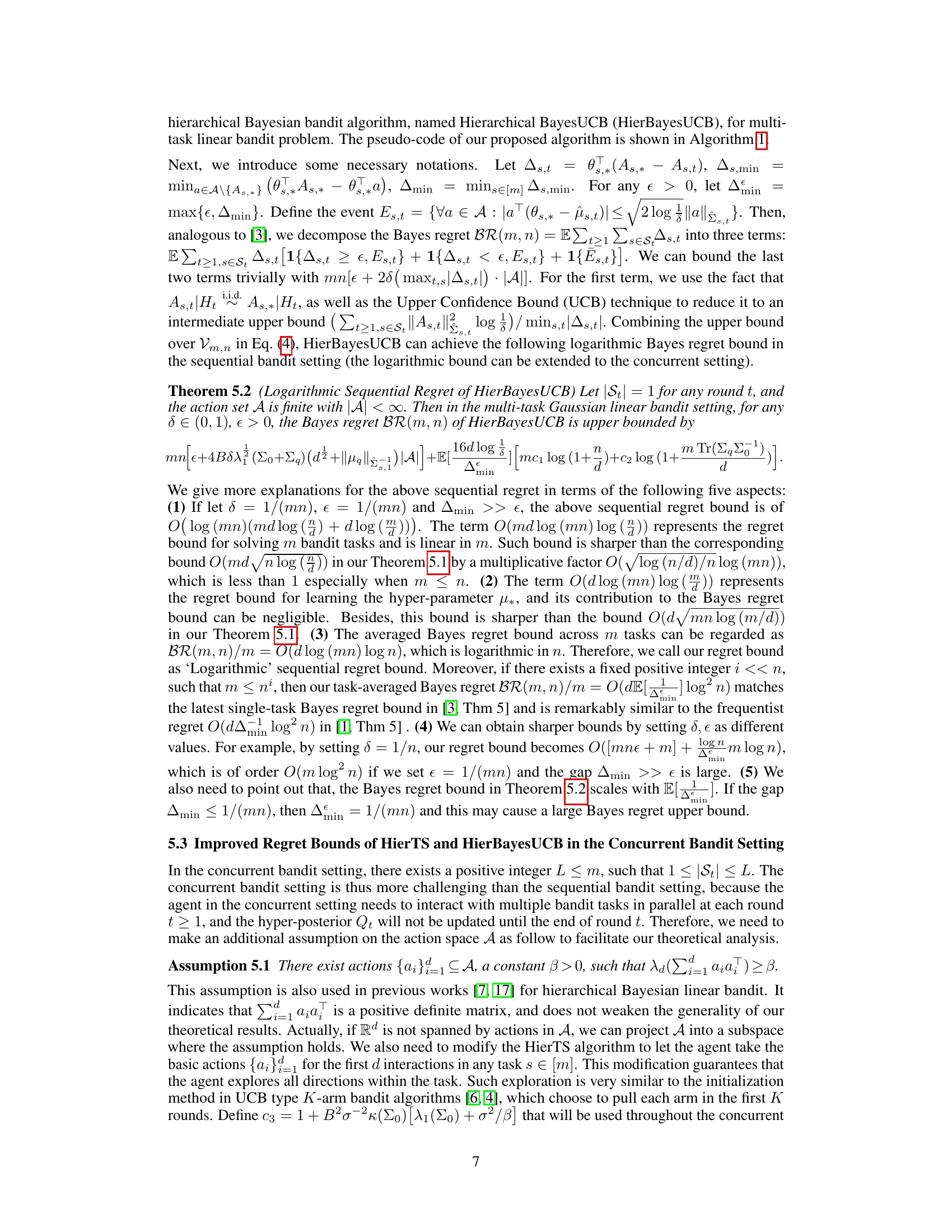

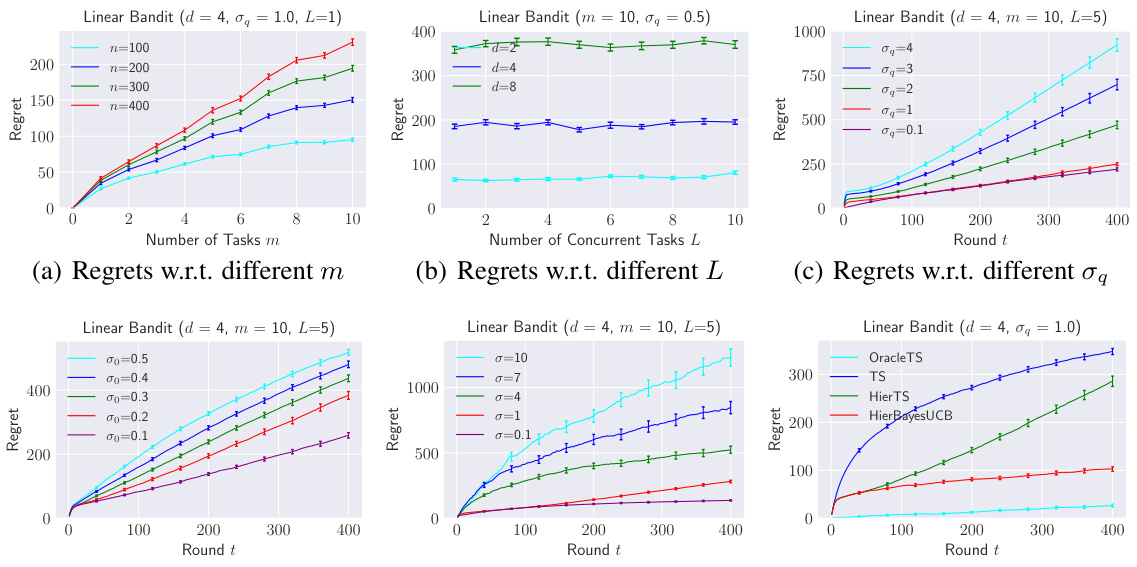

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the HierTS algorithm under various hyperparameter settings. Subplots (a) through (e) illustrate the impact of different hyperparameters (number of tasks (m), number of concurrent tasks (L), hyperparameter σq, hyperparameter σο, and noise standard deviation σ) on the cumulative regret of the HierTS algorithm. These plots demonstrate how the regret changes as each hyperparameter is varied, holding the others constant. Subplot (f) compares the performance of HierTS against other algorithms (OracleTS, TS, HierBayesUCB) under a specific hyperparameter configuration, providing a benchmark comparison.

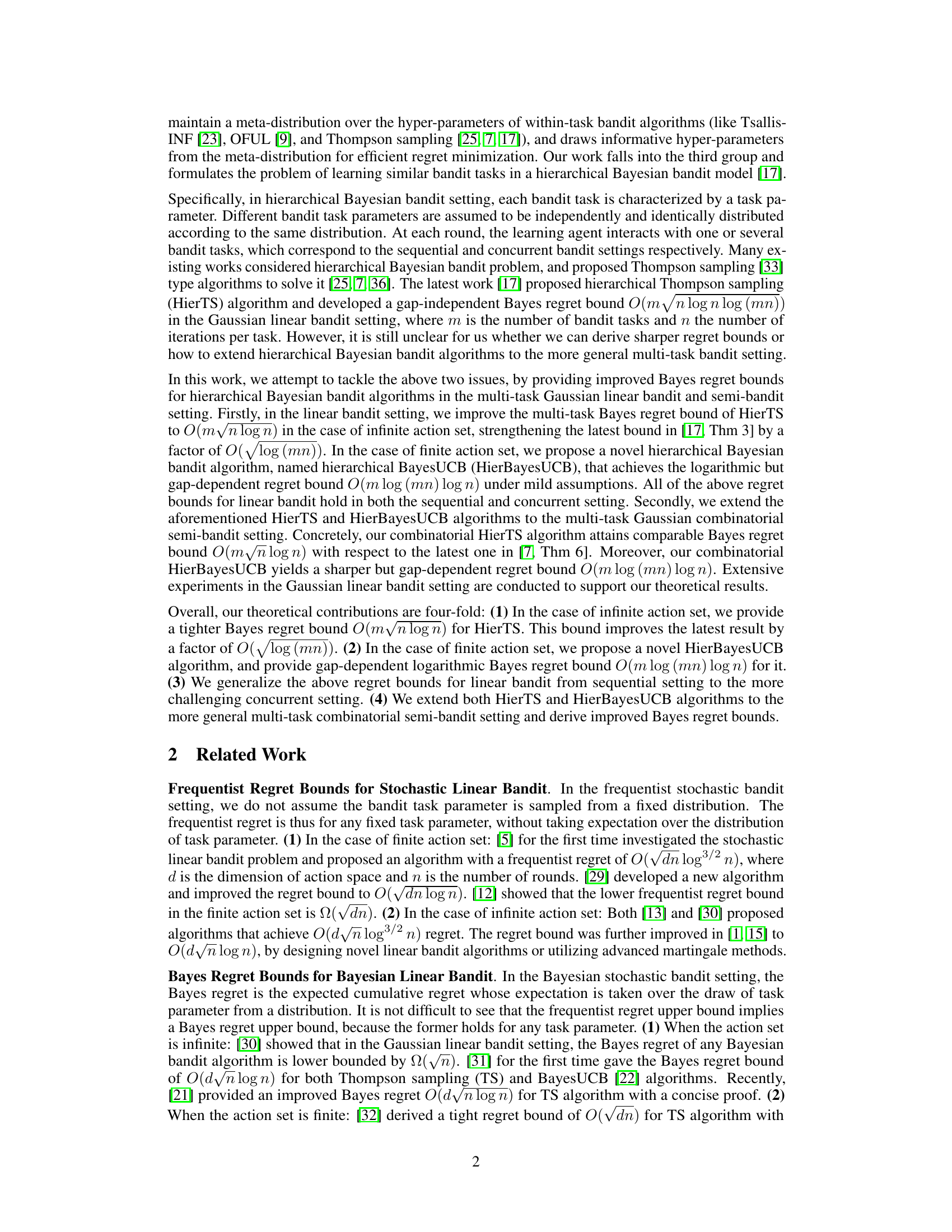

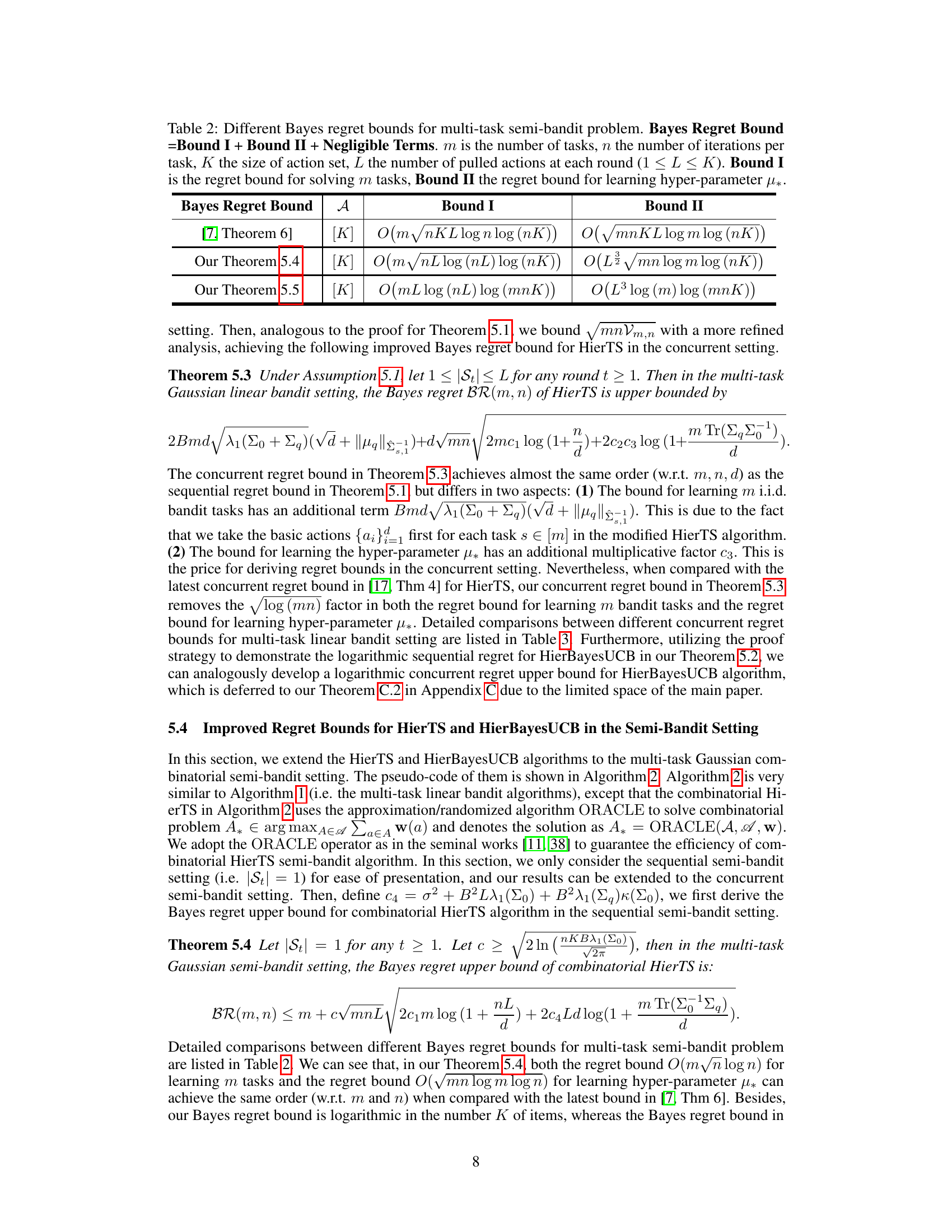

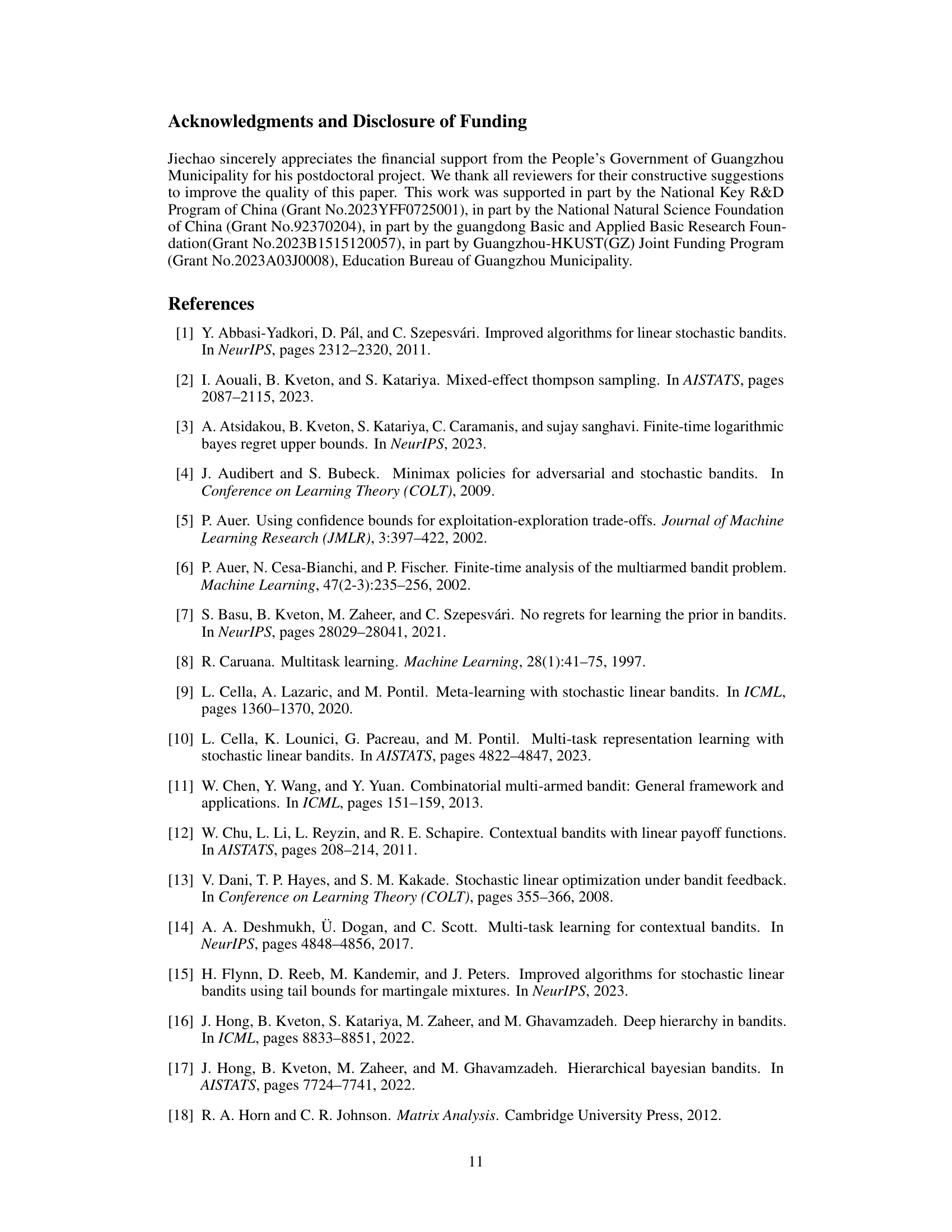

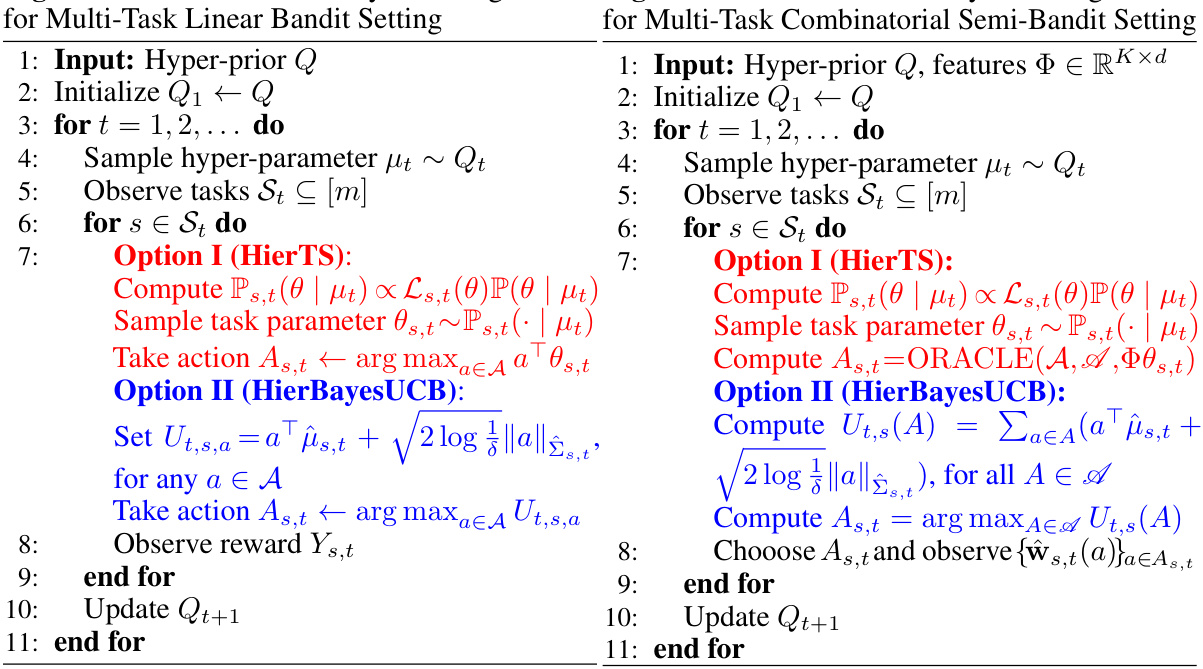

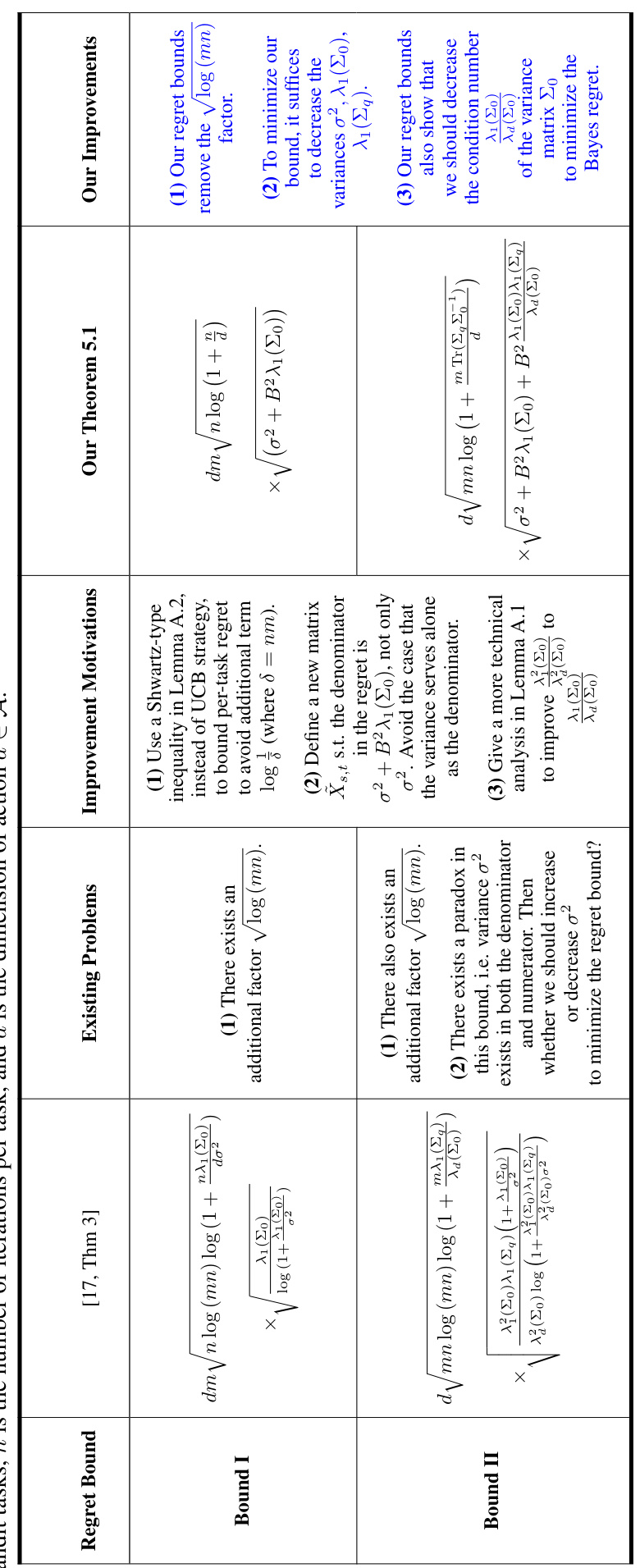

This table compares different Bayes regret bounds for multi-task linear bandit problems in a sequential setting. It shows the regret bounds (Bound I and Bound II) achieved by various algorithms from different papers, distinguishing between the regret for solving multiple tasks and the regret for learning hyperparameters. The action set (A) can be finite or infinite.

In-depth insights#

HierBayes Bandits#

HierBayes Bandits represent a novel approach to multi-task bandit problems, leveraging a hierarchical Bayesian framework to model the relationships between tasks. This approach assumes that individual task parameters are drawn from a shared, higher-level distribution, allowing for efficient transfer learning between tasks. The core idea is to learn a meta-distribution over task parameters, which enables the algorithm to adapt quickly to new tasks and improve performance over traditional independent learning methods. This hierarchical structure is particularly beneficial in scenarios with limited data per task. By sharing information across tasks, HierBayes Bandits can reduce the exploration-exploitation dilemma and lead to better overall performance. Key theoretical contributions typically focus on deriving regret bounds, which quantify the algorithm’s performance compared to an oracle that knows the optimal actions in advance. This analysis provides a rigorous evaluation of the method’s efficiency and effectiveness in the multi-task setting. While effective, the performance of HierBayes Bandits is often sensitive to the choice of prior distributions and hyperparameters, requiring careful tuning for optimal results. Furthermore, extensions to more complex bandit settings, such as combinatorial bandits, are areas of active research.

Regret Bounds#

The section on ‘Regret Bounds’ in a multi-task Bayesian bandit algorithm research paper would delve into the theoretical guarantees of the proposed algorithms. It would likely present upper bounds on the cumulative Bayes regret, which quantifies the algorithm’s performance relative to an optimal strategy. These bounds would typically be expressed as functions of key parameters, such as the number of tasks (m), the number of rounds (n) per task, the dimension of the action space (d), and possibly problem-specific constants. The analysis might distinguish between settings with finite and infinite action sets, leading to different types of bounds (e.g., logarithmic vs. square-root). A crucial aspect would be the comparison of the derived bounds to existing results, highlighting any improvements in terms of tightness or dependency on problem parameters. Gap-dependent and gap-independent bounds would likely be discussed, representing the trade-off between the algorithm’s performance on problems with large versus small reward gaps between actions. Finally, the analysis might extend to more challenging scenarios, such as concurrent task settings where multiple tasks are solved simultaneously, or combinatorial semi-bandit settings dealing with sets of actions rather than individual actions.

Concurrent Tasks#

The concept of “Concurrent Tasks” in a multi-task learning scenario signifies handling multiple tasks simultaneously. This contrasts with a sequential approach where tasks are processed one after another. Concurrency introduces complexities in algorithm design, particularly concerning resource allocation and managing inter-task dependencies. Algorithms designed for concurrent settings must efficiently distribute resources across tasks while minimizing interference. Efficient parallelization becomes crucial for scalability and speed. However, concurrency also presents challenges. It can lead to increased computational overhead if not implemented carefully. The theoretical analysis of algorithms in concurrent settings often becomes more intricate compared to sequential settings. Analyzing performance metrics such as regret or accuracy requires considering the interactions between concurrently executing tasks. There may be trade-offs involved: a highly parallelized concurrent approach might sacrifice some level of individual task accuracy for overall speed improvements. Careful evaluation and comparison are needed to determine the optimal level of concurrency for a given problem and set of resources.

Semi-Bandit Setting#

In the semi-bandit setting of multi-task bandit problems, partial feedback is provided, unlike the full feedback in the bandit setting or the absence of feedback in the adversarial setting. The agent selects a subset of actions (items), and receives feedback only on the chosen actions. This partial feedback presents a unique challenge compared to full-information scenarios, requiring careful algorithms to balance exploration and exploitation with limited information. Combinatorial semi-bandits, a common variant, involve choosing a subset of actions with a combined reward, introducing additional complexity. Analyzing the semi-bandit setting necessitates considering the structure of the feedback, often leading to different regret bounds and algorithm designs than those employed in full-information settings. Efficient exploration becomes crucial to minimize regret under partial feedback. Algorithms for combinatorial semi-bandits frequently employ techniques such as upper confidence bounds or Thompson sampling, adapted to handle the subset selection process and the inherent complexities of partial feedback. The theoretical analysis involves deriving regret bounds for specific algorithms and problem instances. This often involves tackling the exploration-exploitation dilemma under partial information and carefully analyzing the relationship between chosen actions and the resulting rewards.

Future Research#

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section could explore extending the theoretical bounds to sub-exponential bandit settings, a significant advancement beyond the current Gaussian setting. This would enhance the applicability and robustness of the proposed algorithms. Another avenue is investigating the impact of task similarity on regret, moving beyond the i.i.d. assumption for task parameters. This would require developing techniques to model and leverage task relationships. Furthermore, empirical evaluation should be broadened to encompass a more diverse range of multi-task bandit problems and real-world applications. Investigating the practical performance under different hyperparameter configurations and more complex scenarios would strengthen the claims. Finally, it would be valuable to analyze the trade-off between computational complexity and regret improvement, exploring potential algorithmic optimizations and parallelization techniques.

More visual insights#

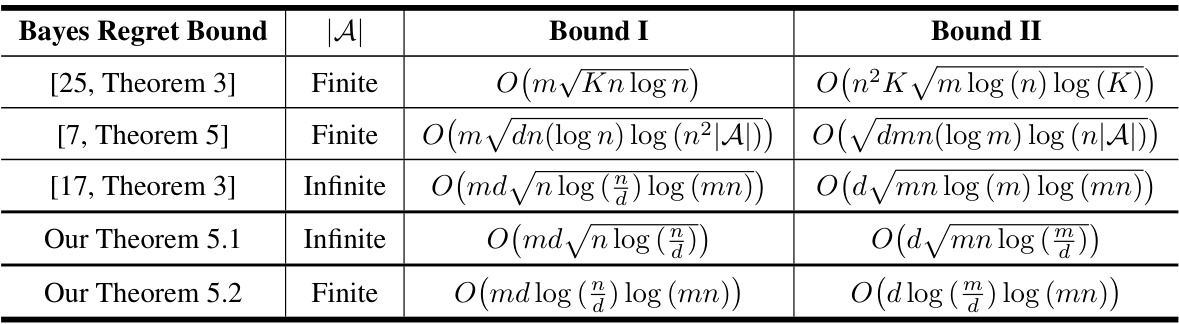

More on tables

This table compares different Bayes regret bounds for multi-task linear bandit problems in the sequential setting. It shows the regret bounds (Bound I and Bound II) achieved by different algorithms ([25, Theorem 3], [7, Theorem 5], [17, Theorem 3], and the authors’ Theorems 5.1 and 5.2), categorized by whether the action set is finite or infinite. Bound I represents the regret for solving the m tasks, and Bound II represents the regret for learning the hyper-parameter μ*. The table helps to illustrate the improvements in regret bounds achieved by the authors’ algorithms.

This table compares different Bayes regret bounds from existing research on multi-task linear bandit problems in a sequential setting (meaning each task is solved one at a time). It shows the regret bounds broken down into two components: Bound I (regret from solving the individual tasks) and Bound II (regret from learning the hyperparameter). The table helps illustrate the improvements achieved in the current paper.

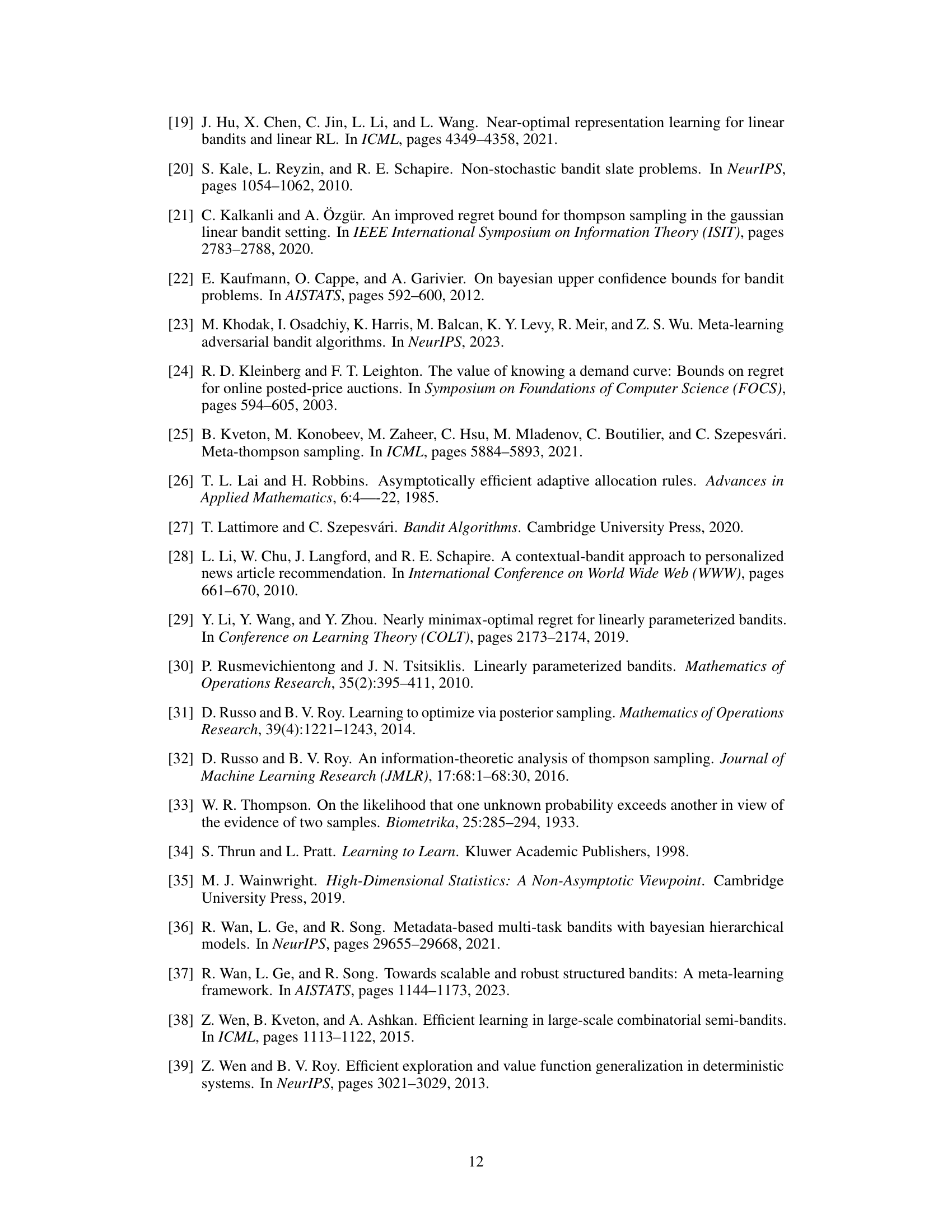

This table compares different Bayes regret bounds for multi-task d-dimensional linear bandit problems in the concurrent setting. It shows the regret bounds obtained from three different sources ([17, Theorem 4], Our Theorem 5.3, Our Theorem C.2), categorized by whether the action set |A| is finite or infinite. For each source, the table is further divided into Bound I (regret bound for solving m tasks) and Bound II (regret bound for learning the hyper-parameter μ*). This allows for a detailed comparison of different approaches to solving the multi-task concurrent linear bandit problem.

This table compares different Bayes regret bounds for multi-task linear bandit problems in a sequential setting. It shows the components of the Bayes regret bound (Bound I for solving m tasks, Bound II for learning the hyperparameter μ*), highlighting the different results obtained by various studies ([25, Theorem 3], [7, Theorem 5], [17, Theorem 3]) and the improved bounds proposed by the authors (Our Theorem 5.1 and Our Theorem 5.2). The action set (A) is considered in both finite and infinite cases.

Full paper#