↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Partial-label learning (PLL) aims to train classifiers using datasets where each instance is associated with a set of possible labels, only one of which is correct. Recent PLL algorithms are highly complex and varied, making it difficult to determine optimal design choices. This creates a need for a better understanding of what makes a PLL algorithm truly effective.

This paper addresses this issue by performing a comprehensive empirical analysis of existing PLL methods. The researchers identify that successful methods share a common behavior: a progressive transition from uniform to one-hot pseudo-labels. This transition is achieved through a process called mini-batch PL purification. The authors then present a minimal algorithm that leverages this process, demonstrating surprisingly high accuracy, highlighting the critical role of mini-batch PL purification. This simplifies future research by providing essential design guidelines.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in weakly supervised learning, particularly partial-label learning (PLL). It addresses the critical challenge of choosing effective PLL algorithms among many complex methods. By identifying minimal design principles and proposing a simple yet effective algorithm, this research significantly streamlines future PLL algorithm development and improves performance. The findings impact algorithm design, potentially improving the accuracy and efficiency of numerous applications involving uncertain labels.

Visual Insights#

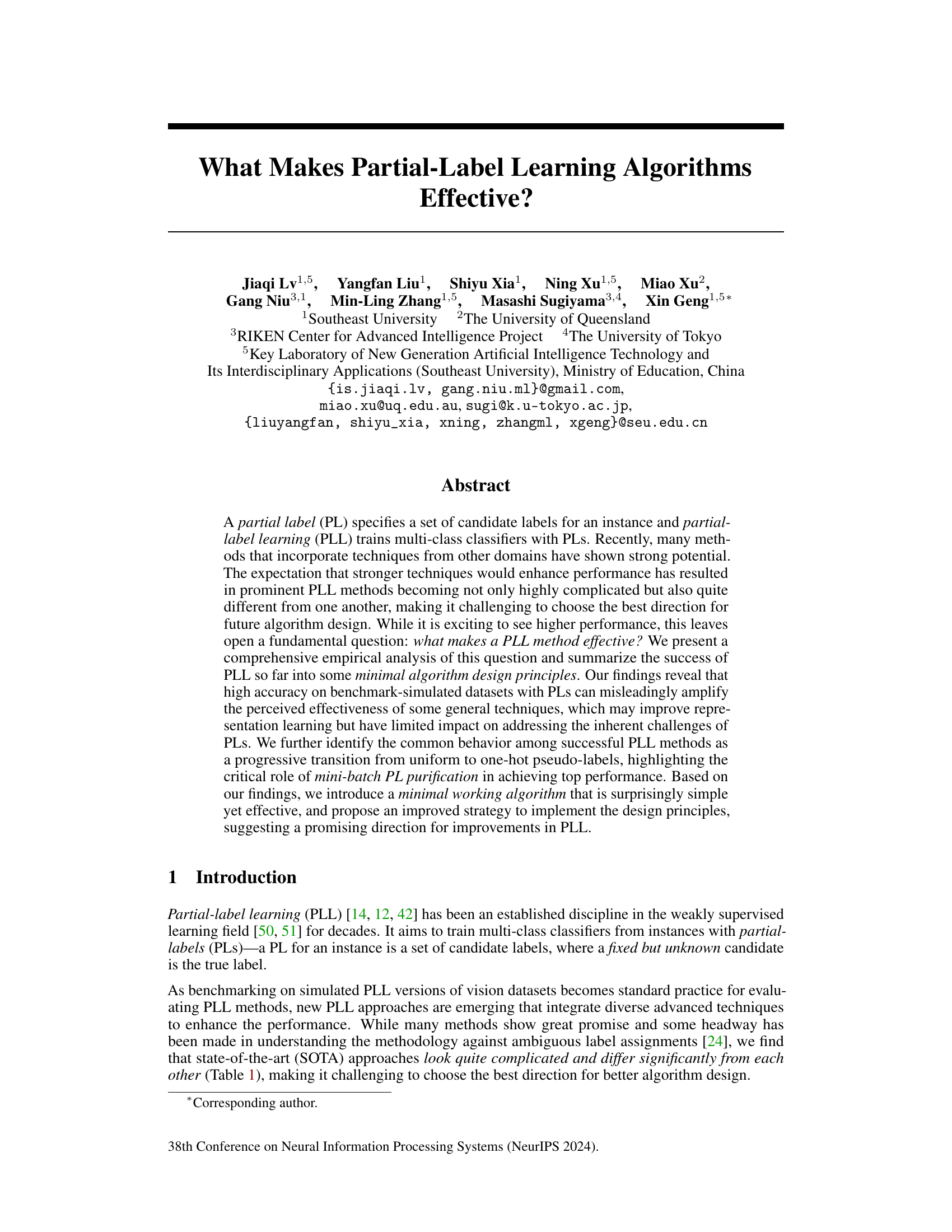

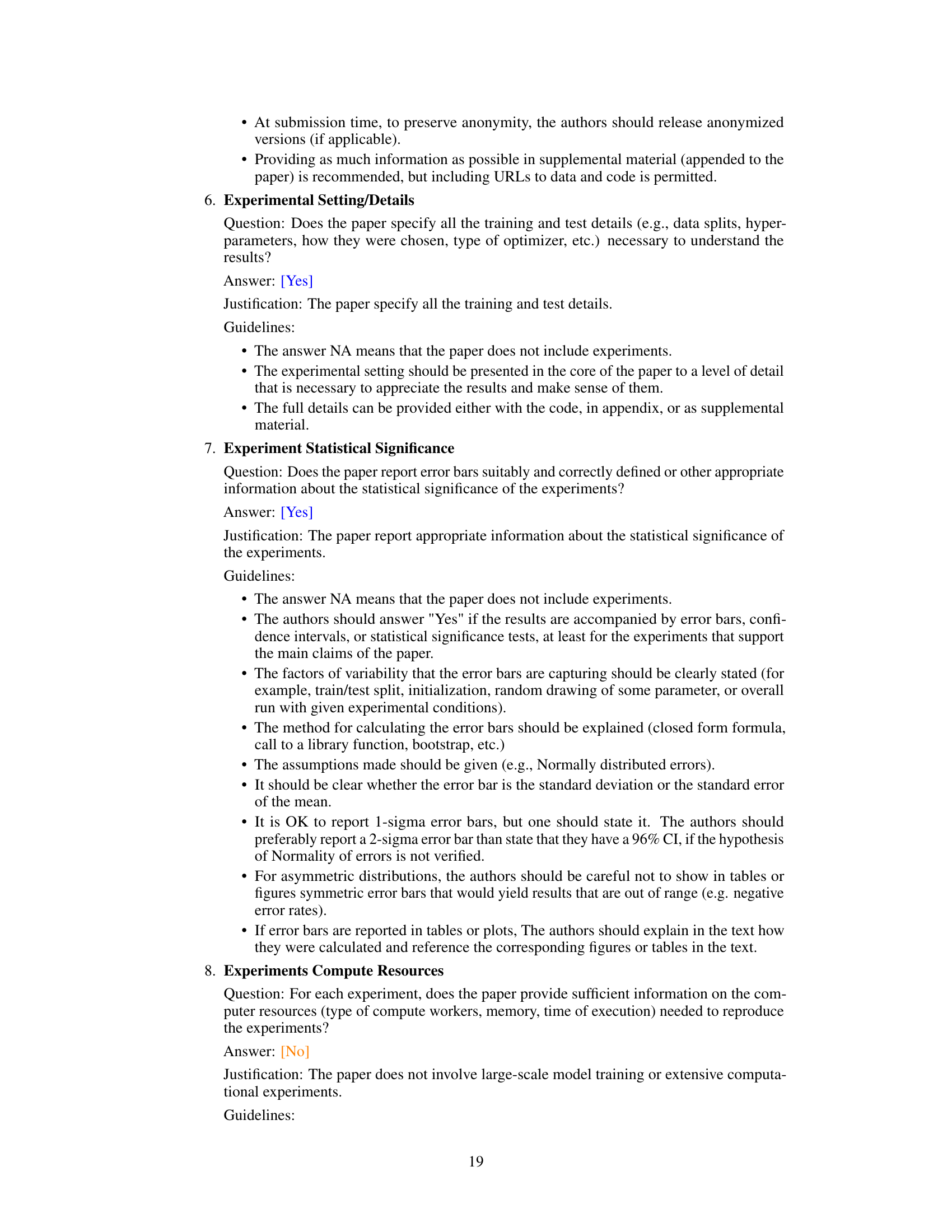

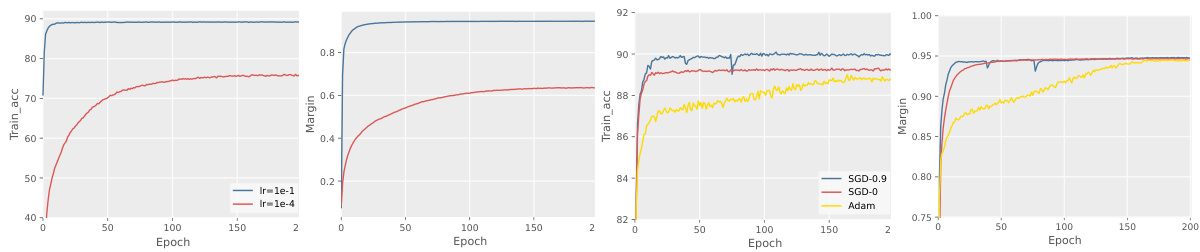

This figure shows the training accuracy and confidence margin of predicted pseudo-labels for both traditional identification-based strategy (IBS) and average-based strategy (ABS) methods on the Fashion-MNIST dataset with partial labels (PLs). The subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate how the granularity of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) execution in IBS methods changes during training. Initially, the EM process is performed in a single step, but this is gradually refined to encompass an entire epoch. This refinement causes a smoother transition from uniform to one-hot pseudo-labels. Subfigures (c) and (d) show that when using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization, the optimization targets for candidate labels in ABS methods gradually become more distinct over time. This observation highlights that ABS methods might behave in a way similar to IBS methods under appropriate conditions.

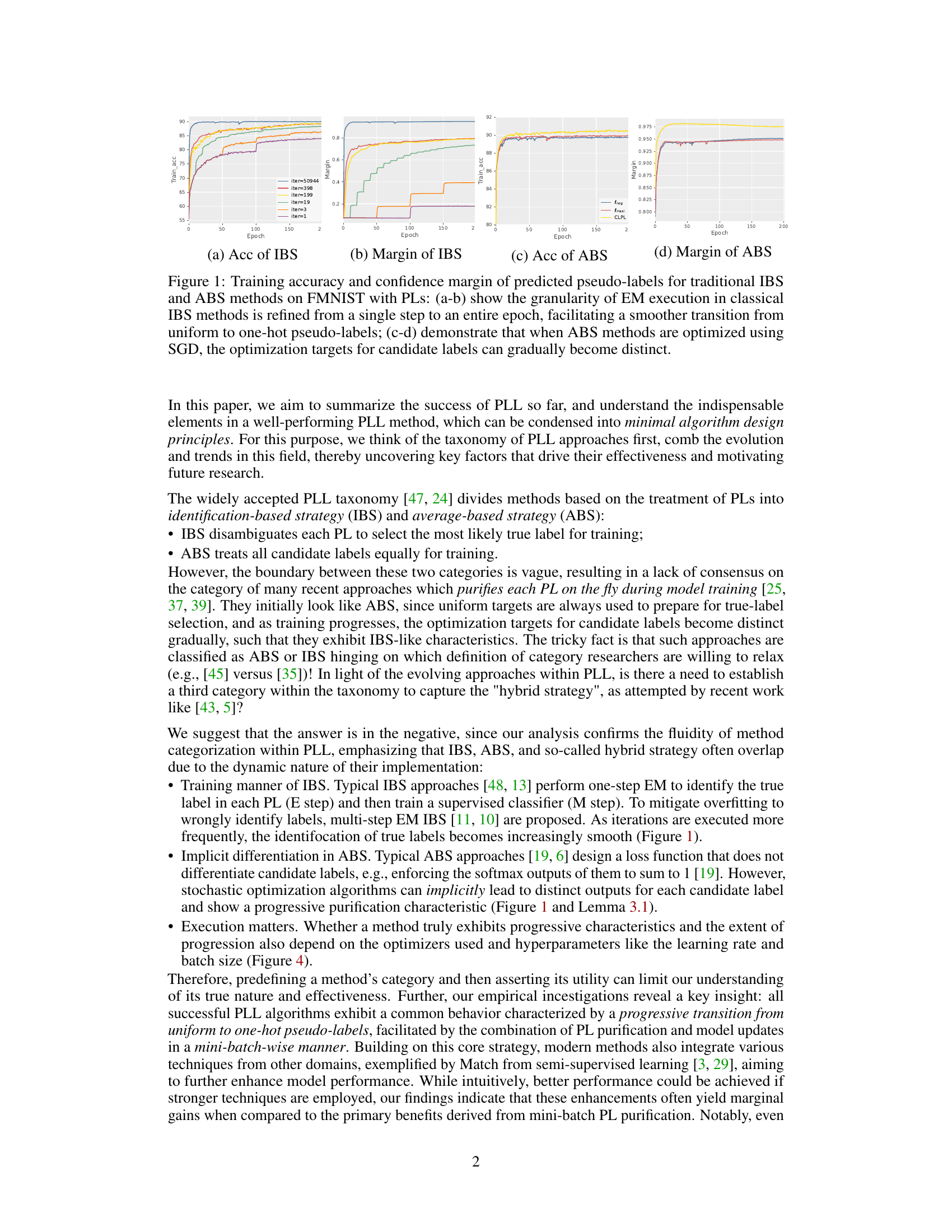

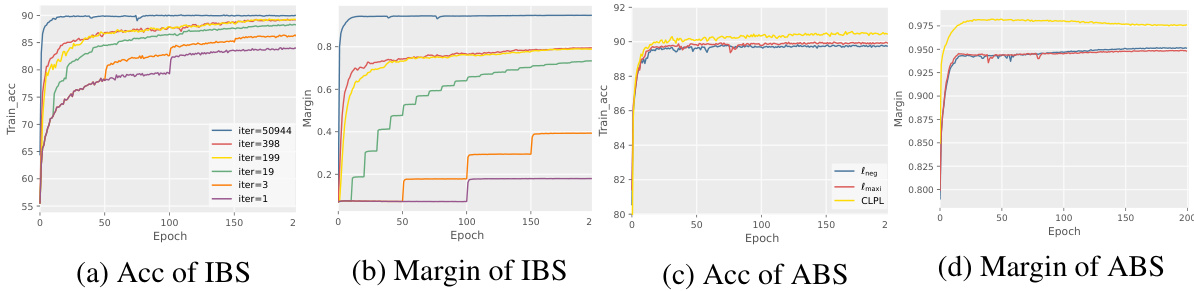

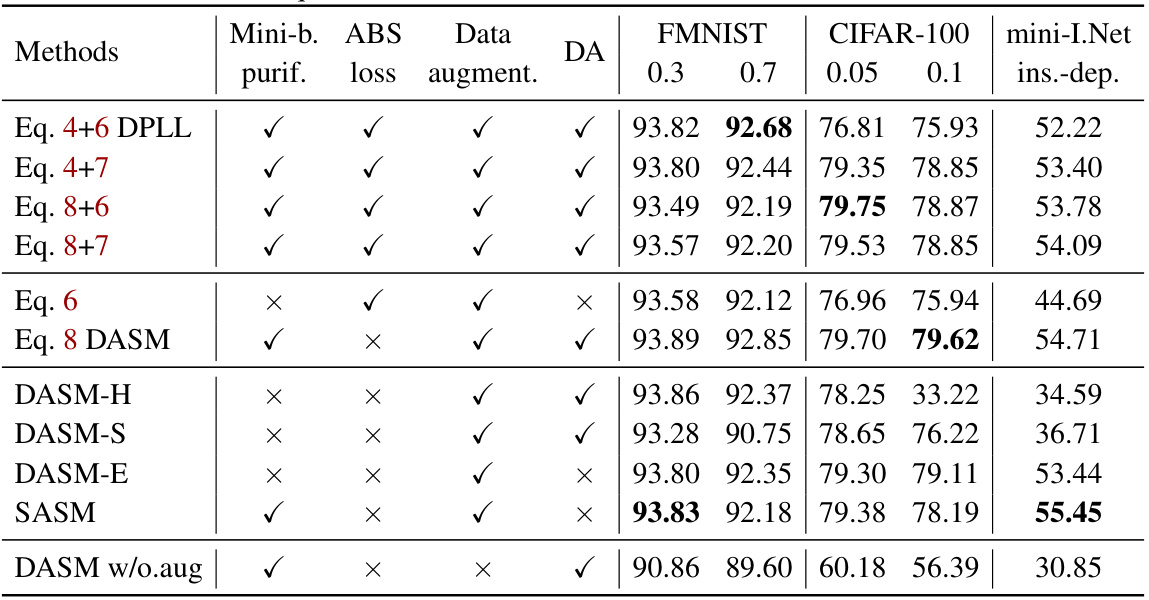

This table compares eight prominent Partial Label Learning (PLL) methods, showing which techniques they utilize. The techniques include mini-batch purification, Mixup, data augmentation, exponential moving average, data augmentation match (DA), and dual-model match (DM). The table also lists the main assumption each method makes.

In-depth insights#

PLL Algorithm Design#

Effective Partial Label Learning (PLL) algorithm design hinges on mini-batch PL purification, progressively transitioning pseudo-labels from uniform to one-hot encodings. While incorporating advanced techniques like Mixup or data augmentation can improve representation learning, they offer marginal gains compared to the core principle of purification. Successful algorithms demonstrate a fluid categorization, blurring the lines between identification-based and average-based strategies. The key is the dynamic, iterative refinement of pseudo-labels within mini-batches, not a predefined, static approach. Furthermore, algorithm design should focus on simplicity and effectiveness; a surprisingly simple algorithm implementing the core purification principle achieves competitive results with complex state-of-the-art methods. This emphasizes the critical role of iterative pseudo-label refinement over sophisticated auxiliary techniques in achieving high accuracy.

Mini-batch Purification#

Mini-batch purification, a core concept in partial-label learning (PLL), addresses the challenge of ambiguous labels by iteratively refining the weights assigned to candidate labels within each mini-batch. It’s a dynamic process where initial uniform weights evolve progressively towards one-hot pseudo-labels as the model learns, highlighting a crucial transition from average-based to identification-based strategies. This refinement is driven by the model’s increasing confidence in specific labels within a mini-batch, allowing for a smoother and more effective training process. Successful PLL algorithms often implicitly or explicitly incorporate this technique, demonstrating its essential role in achieving high accuracy. The method enhances the efficiency of algorithm design, leading to surprisingly simple yet effective minimal working algorithms. However, over-reliance on this strategy, without carefully considering other aspects such as data augmentation and model architecture, might limit the method’s effectiveness and lead to the marginal gains. The process’ success depends significantly on the effective interplay between model updates and weight adjustments within each mini-batch, making it a key design principle in advanced PLL methods.

Data Augmentation Role#

The role of data augmentation in partial-label learning (PLL) is multifaceted and requires nuanced understanding. While intuitively expected to enhance model robustness and generalization, the study reveals a more subtle impact. Data augmentation primarily improves representation learning, rather than directly addressing the core challenge of disambiguation inherent in PLL. The experiments highlight that augmenting data, while beneficial, does not necessarily lead to more accurate pseudo-label identification; in fact, using pseudo-labels from augmented data to supervise the original data can even degrade performance. This suggests that data augmentation’s contribution in PLL lies more in boosting feature extraction than in improving the reliability of pseudo-label generation. Therefore, while it serves as a valuable tool to enhance model stability, it should not be considered a fundamental design principle for effective PLL methods; the focus should remain on robust pseudo-label purification strategies.

PLL Taxonomy Limits#

The limitations of existing PLL taxonomies become apparent when considering the dynamic nature of modern PLL algorithms. Traditional binary categorizations (IBS vs. ABS) fail to capture the nuanced approaches that often blend aspects of both. Many state-of-the-art methods exhibit a progressive transition from uniform to one-hot pseudo-labels during training, defying simple categorization. This fluidity highlights the need for a more flexible and descriptive taxonomy that accounts for this dynamic behavior. A taxonomy focused on the underlying principles and mechanisms of PL purification, rather than rigid algorithmic classifications, would offer a more insightful understanding of PLL algorithm design and effectiveness. Such a framework could better guide future research by emphasizing commonalities and underlying design principles amongst diverse approaches.

Future Research#

Future research directions in partial-label learning (PLL) should prioritize developing more robust and efficient mini-batch PL purification strategies. This includes exploring adaptive warm-up strategies that dynamically adjust to individual instance readiness and investigating alternative methods for refining pseudo-labels beyond current techniques. Addressing the limitations of existing data augmentation techniques in PLL is also crucial, focusing on methods that genuinely improve true label identification rather than simply enhancing model robustness. A deeper exploration of the interplay between pseudo-label manipulation and loss minimization in PLL is necessary to fully understand their effectiveness. Finally, extending PLL to new domains beyond vision tasks and evaluating its effectiveness in more challenging scenarios will be important for assessing its practical impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

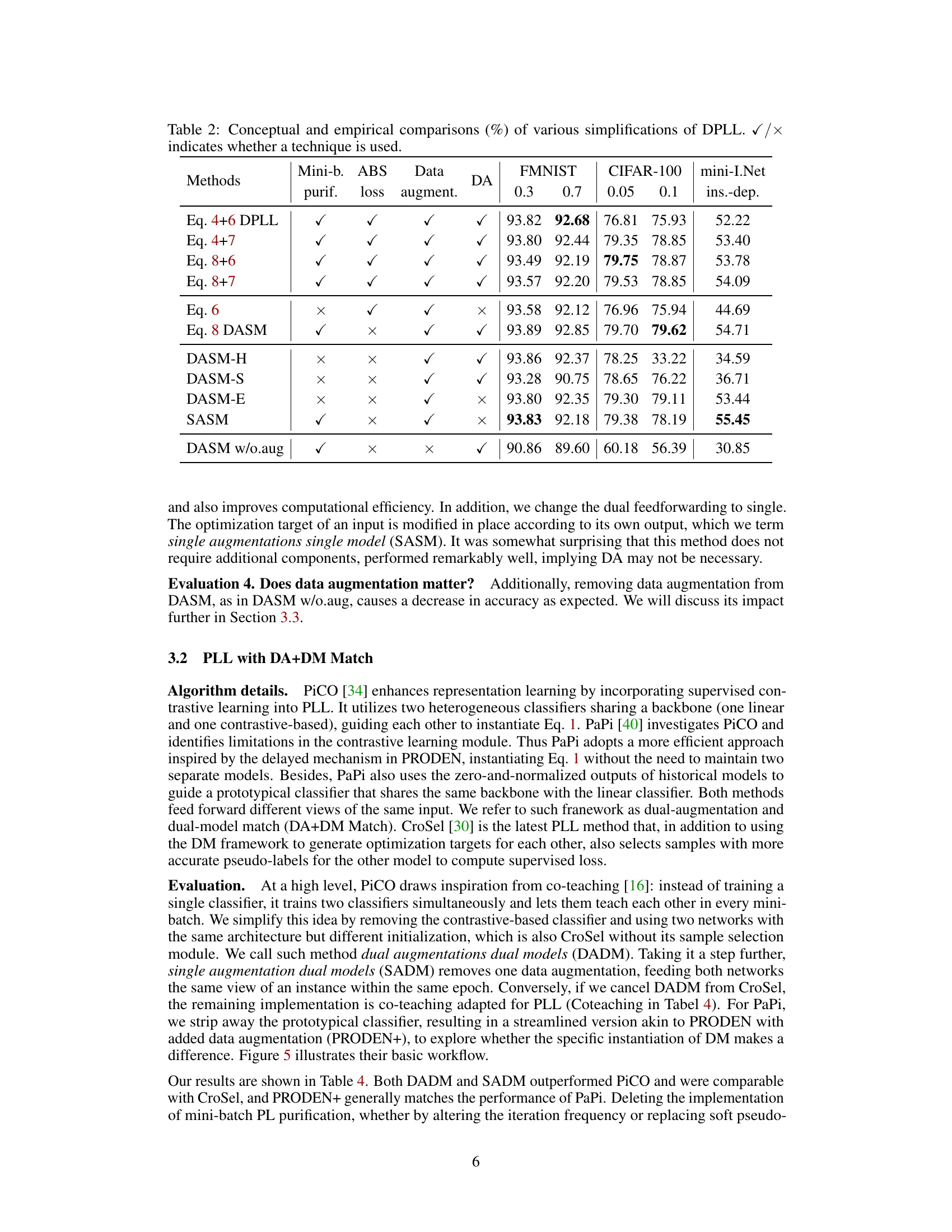

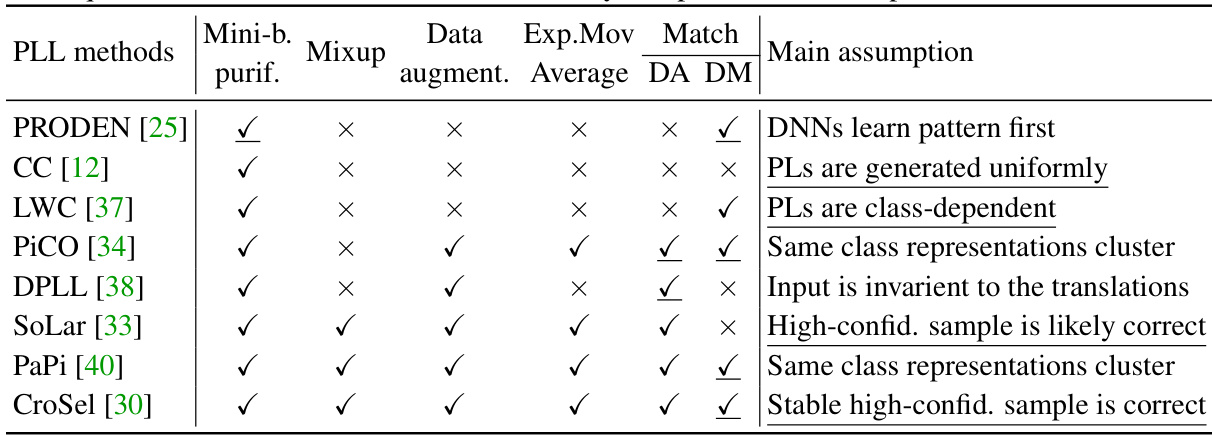

This figure compares the performance of different training setups for the DASM (Dual Augmentation Single Model) algorithm on the FMNIST dataset with partial labels. The left panel (a) displays the accuracy of the pseudo-labels generated during training, illustrating how well the model is able to identify the true labels within the sets of candidate labels. The right panel (b) shows the test accuracy, which represents the generalization performance of the model on unseen data. Different colors show different training setup configurations. The results indicate that a specific training setup (SADM) outperforms other strategies, highlighting the importance of the choice of training setup for effective PLL (Partial Label Learning).

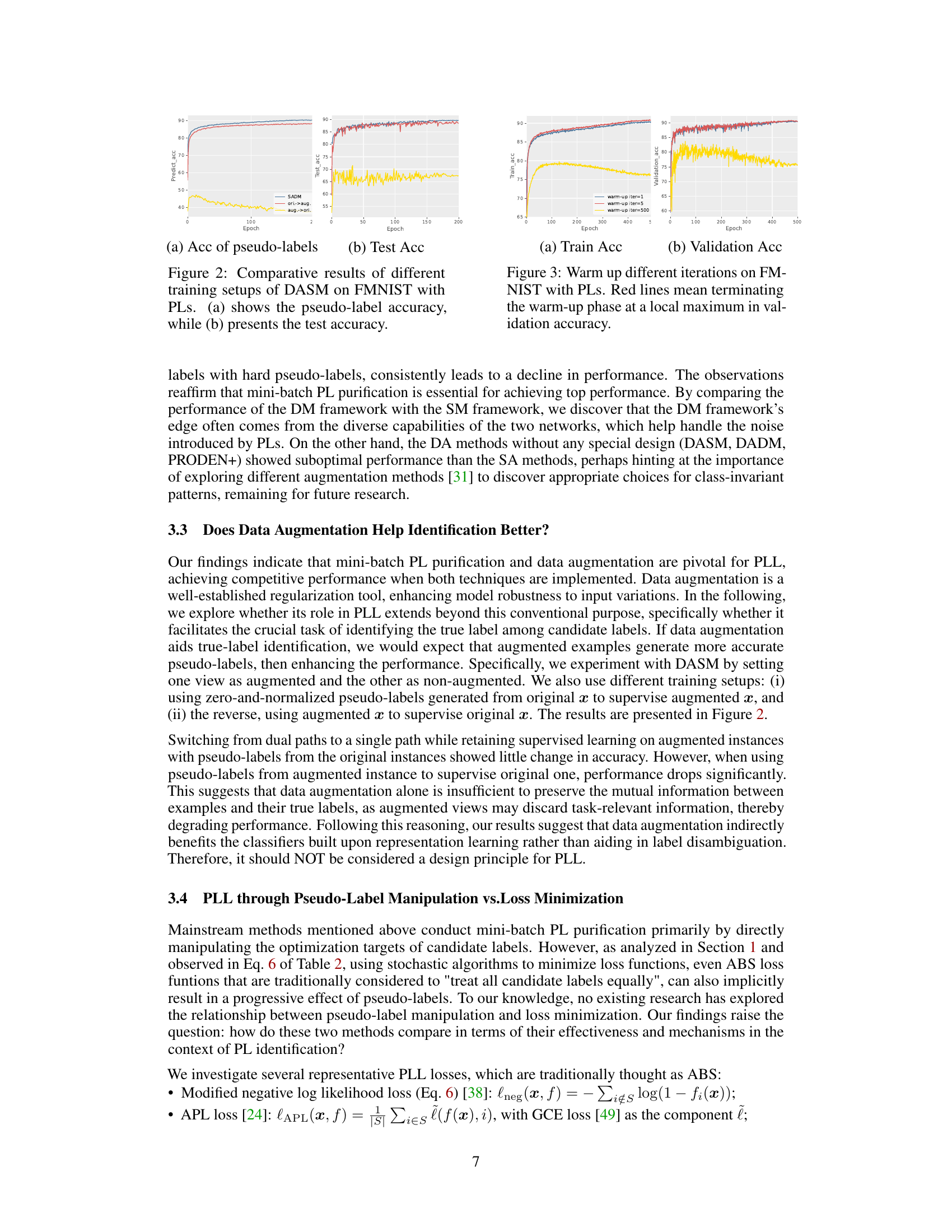

This figure shows the training and validation accuracy curves for three different warm-up iteration numbers (1, 5, and 500) on the Fashion-MNIST dataset with partial labels. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The red lines indicate where the validation accuracy reached a local maximum, suggesting that prematurely stopping the warm-up phase before overfitting may improve performance. The optimal warm-up strategy appears to be neither too short nor too long.

This figure visualizes the training accuracy and confidence margin of predicted pseudo-labels for the SASM (Single Augmentation Single Model) method on the FMNIST dataset with partial labels. It explores the impact of different learning rates (1e-1 and 1e-4) and optimizers (SGD with momentum 0.9, SGD without momentum, and Adam) on the model’s performance. The plots show how these hyperparameters affect the convergence of the model and the clarity of the pseudo-labels during training.

This figure illustrates the core components of four state-of-the-art partial label learning (PLL) methods: DASM, SADM, DADM, and PRODEN+. Each method’s architecture is shown, highlighting the key components: dual augmentations, dual models, and the use of mini-batch PL purification. The figure simplifies the architecture of each method to illustrate the commonalities and differences in their approaches to addressing the challenges of partial labeling.

More on tables

This table compares eight prominent partial-label learning (PLL) methods, highlighting the techniques used in each. It shows whether each method utilizes mini-batch purification, Mixup, data augmentation, exponential moving average, Match (DA or DM), and the main assumption behind the method’s design. The table helps to understand the diversity of approaches and the key components driving their success.

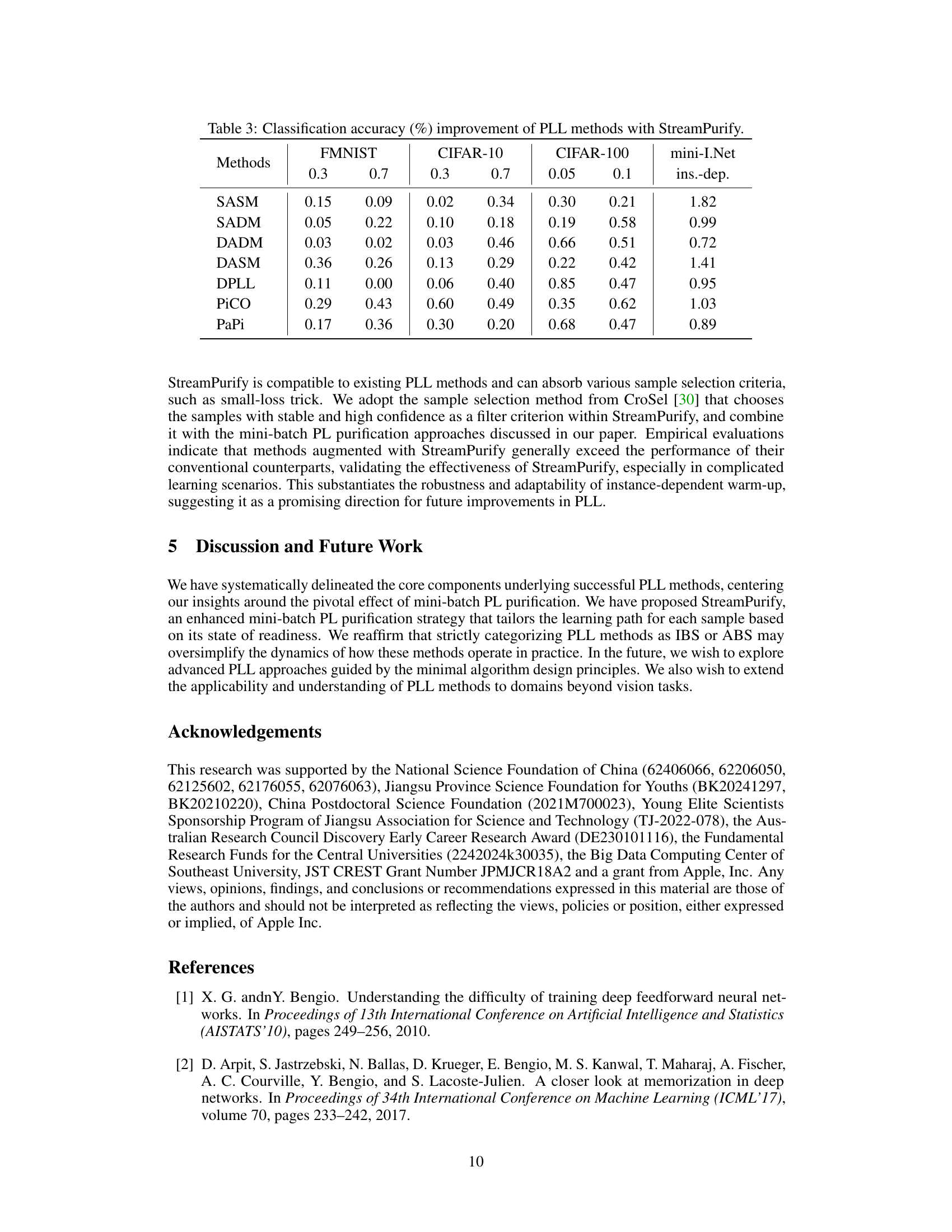

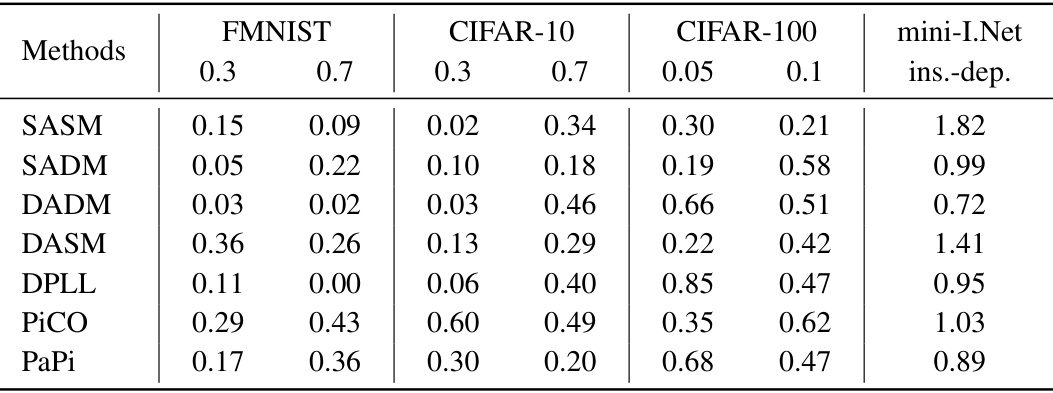

This table shows the improvement in classification accuracy achieved by adding the StreamPurify method to various Partial Label Learning (PLL) algorithms. The results are presented for different datasets (FMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, mini-ImageNet) and varying noise levels (represented by the flipping probability). The improvement is calculated as the difference in accuracy between the original PLL method and the same method augmented with StreamPurify.

This table compares eight prominent Partial Label Learning (PLL) methods, highlighting the techniques used in each. It shows whether each method utilizes mini-batch purification, mixup, data augmentation, exponential moving average, match, and other techniques. It also briefly describes the main assumption behind each method. This helps in understanding the different approaches to PLL and their key components.

This table presents the average training and testing accuracy results obtained using three different loss functions: lneg, lAPL, and lmaxi. The results are shown for various datasets (FMNIST, CIFAR-100, mini-ImageNet) and different noise levels (0.3, 0.7 for FMNIST; 0.05, 0.1 for CIFAR-100; instance-dependent for mini-ImageNet). It demonstrates the impact of different loss functions on the accuracy of partial label learning models.

Full paper#