↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Online control of continuous-time systems is challenging due to the presence of non-stochastic noise and the need for real-time adaptation. Existing methods often struggle with these issues, leading to suboptimal control performance. This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on continuous-time linear systems.

The researchers developed a two-level online control algorithm that addresses these issues. This method uses a higher-level strategy to learn the optimal control policy and a lower-level strategy to provide real-time feedback. By applying this algorithm, they achieved sublinear regret, meaning that the algorithm’s performance comes close to the performance of an optimal controller. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach for training agents in domain randomization environments, significantly improving performance compared to traditional methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it provides the first non-asymptotic results for controlling continuous-time linear systems with a finite number of interactions, addressing a significant gap in the field. Its novel two-level online control algorithm achieves sublinear regret even under adversarial disturbances, offering a practical and robust solution for real-world applications. The work also demonstrates the effectiveness of techniques like frame stacking and skipping in domain randomization, providing valuable insights for sim-to-real transfer.

Visual Insights#

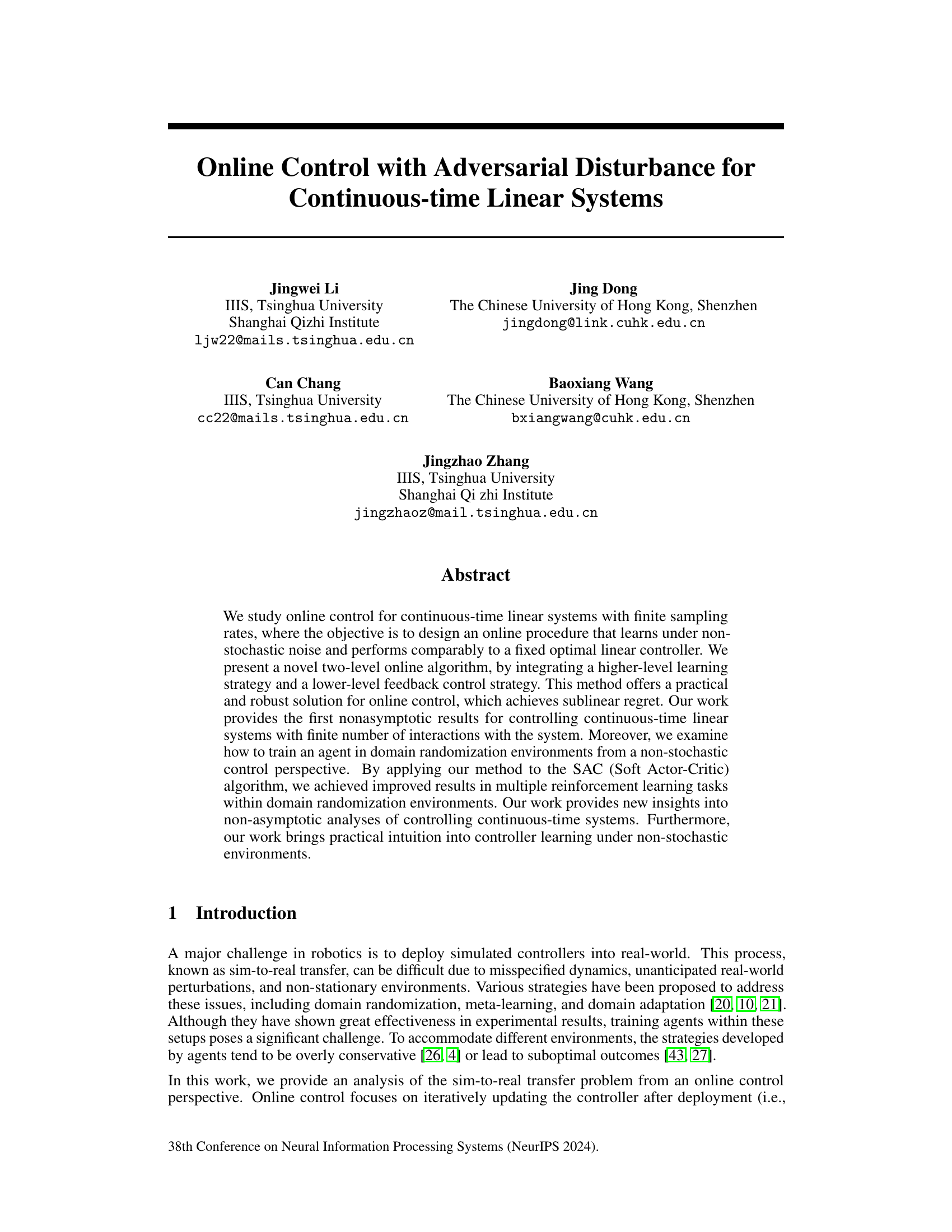

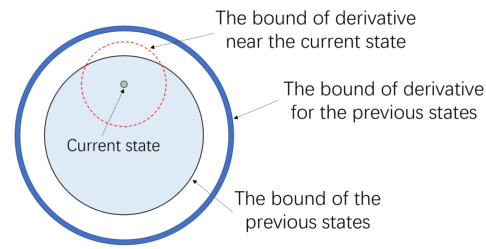

The figure illustrates the method used to bound the states and their derivatives in a continuous-time system. It shows three concentric circles representing bounds on previous states, previous state derivatives, and the current state and its derivative. The iterative application of Gronwall’s inequality with induction allows for bounding of the states, a key step in proving sublinear regret for the continuous online control algorithm.

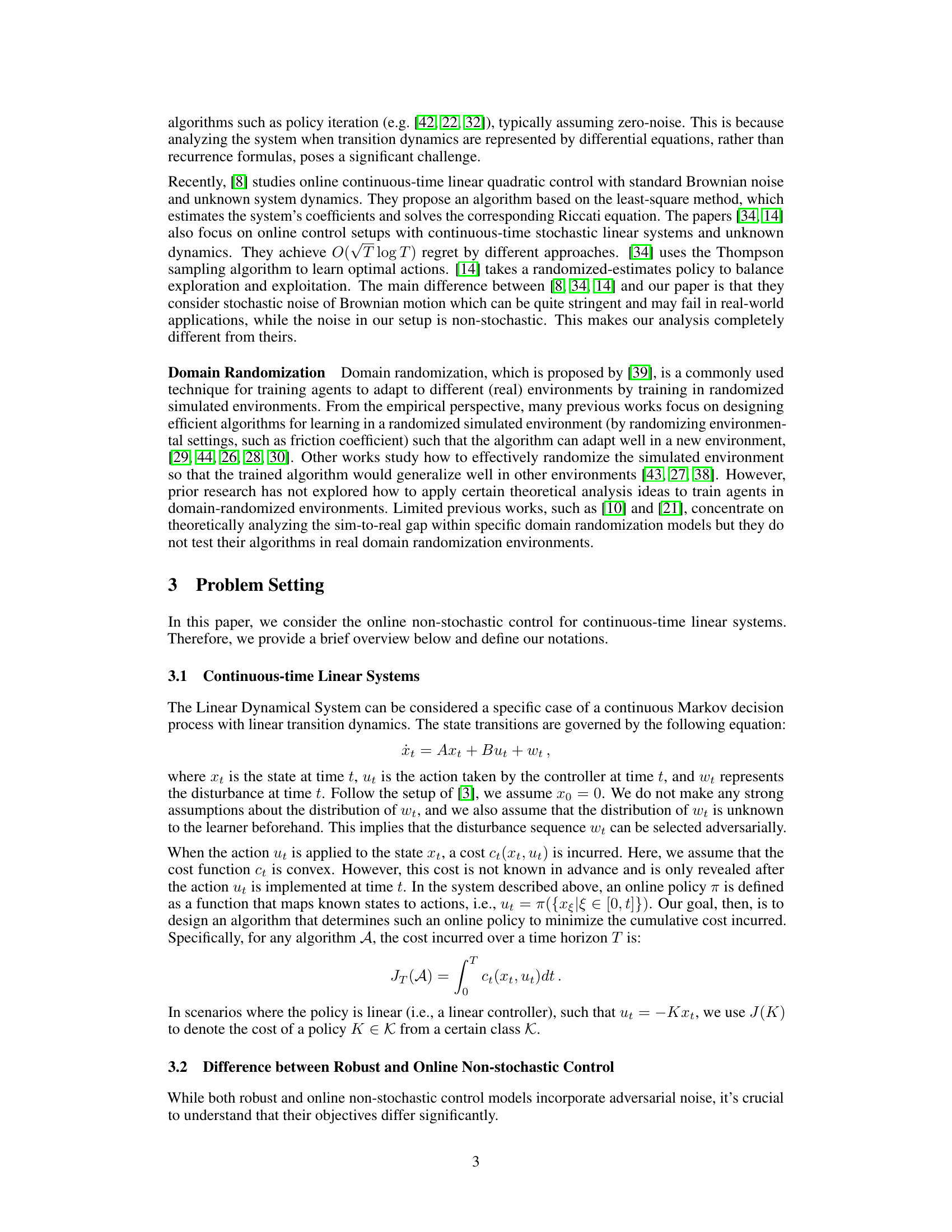

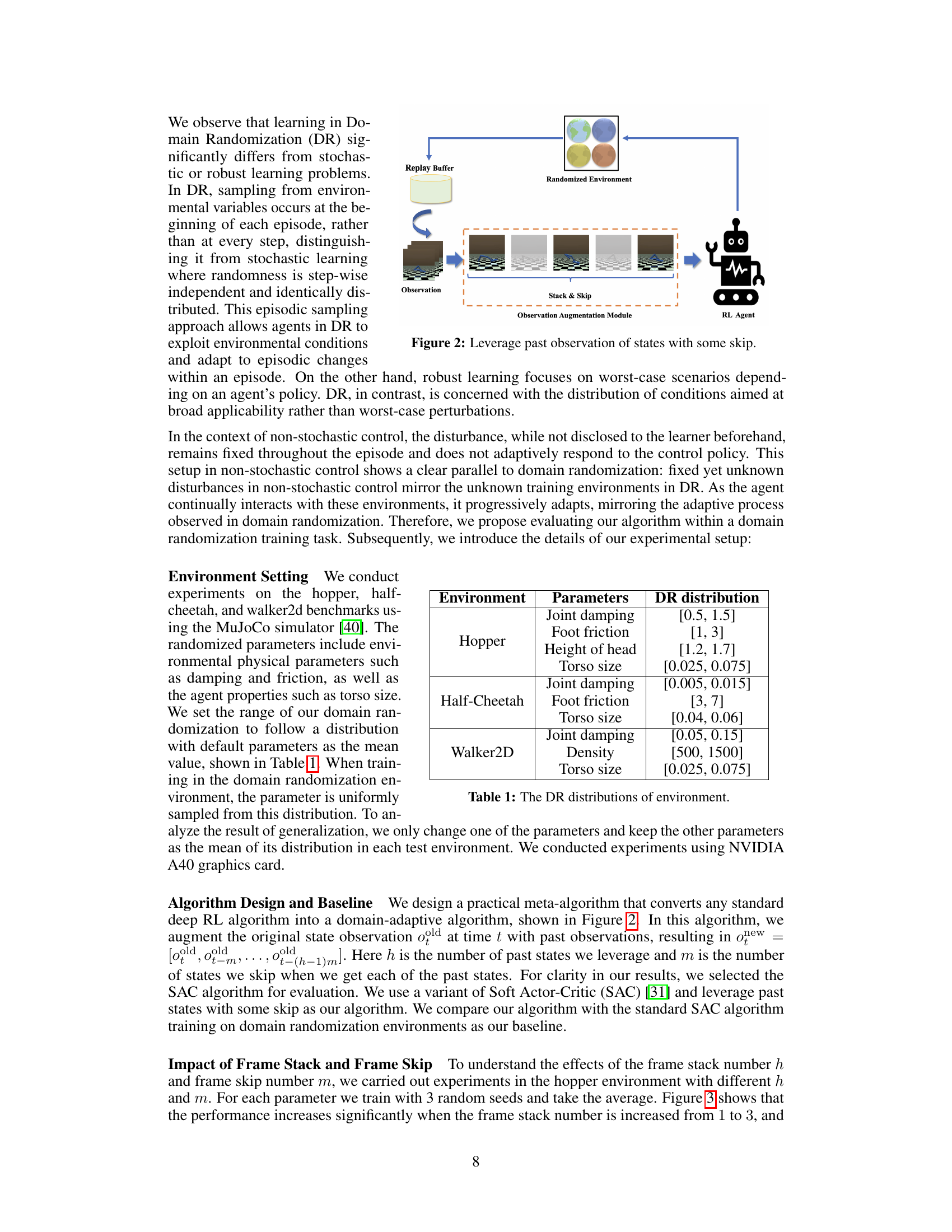

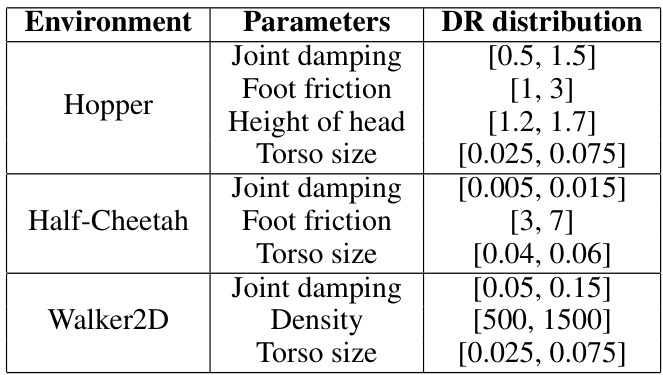

This table shows the range of parameters that are randomized in the domain randomization experiments. For each environment (Hopper, Half-Cheetah, and Walker2D), several parameters are listed along with their ranges. These parameters represent physical properties of the simulated environments, such as joint damping, foot friction, height of the head, and torso size. The randomized values are uniformly sampled from the specified intervals.

In-depth insights#

Adversarial Robustness#

Adversarial robustness examines how machine learning models, particularly in control systems, withstand malicious attacks or unexpected disturbances. A core challenge lies in designing algorithms capable of maintaining performance even when faced with adversarial inputs crafted to mislead the system. This involves developing methods to detect and mitigate these attacks, often relying on techniques that enhance model generalization. Robustness is crucial for safety-critical applications where model failures can have severe consequences, such as autonomous vehicles or medical devices. The analysis often includes understanding the vulnerabilities within model architectures and designing defenses to prevent or reduce the impact of such attacks. Key approaches may incorporate input validation, regularization, and the use of robust optimization methods in model training. Evaluating adversarial robustness typically involves testing against various attack strategies to gauge the model’s resilience. The continuous-time setting adds complexity due to the continuous nature of the disturbances and system dynamics, necessitating specialized techniques for both algorithm design and analysis.

Online Control Algo#

An online control algorithm continuously adapts to changing environments by iteratively updating its control policy based on observed system behavior. Unlike traditional control methods that rely on pre-defined models, online algorithms learn directly from data. This adaptability is particularly valuable in situations with incomplete system knowledge or unpredictable disturbances. The algorithm’s performance is often evaluated by its regret, measuring how much worse it performs compared to an optimal controller with complete prior knowledge. Key design considerations include the choice of policy update mechanism (e.g., gradient descent, least-squares), the frequency of updates, and the method for handling noisy or adversarial inputs. The theoretical analysis of online control algorithms focuses on deriving regret bounds to guarantee performance improvements over time. Practical implementations may incorporate techniques such as domain randomization to improve generalization and robustness. Successful online control algorithms must balance exploration (learning about the environment) and exploitation (using current knowledge to achieve optimal control).

Sim-to-Real Transfer#

Sim-to-real transfer, bridging the gap between simulated and real-world environments, is a critical challenge in robotics and AI. The core difficulty lies in the discrepancies between the idealized dynamics of simulations and the complexities of the real world. Factors such as sensor noise, unmodeled friction, and unpredictable disturbances make directly deploying simulated controllers problematic. Domain randomization, a common approach, attempts to mitigate this by training agents in diverse simulated scenarios, but it can lead to overly conservative or suboptimal policies. Online control methods offer a potential solution by adaptively updating controllers based on real-world feedback, effectively learning to compensate for the sim-to-real gap. The success of online methods hinges on efficient algorithms that can learn quickly and robustly in the face of non-stochastic disturbances and limited interaction data. This makes the theoretical analysis of non-asymptotic regret bounds crucial for ensuring practical efficacy. Combining domain randomization with online control strategies represents a promising avenue for more effective sim-to-real transfer, but requires careful consideration of both the environmental uncertainty and the limitations of online learning algorithms.

Regret Bounds#

Regret bounds, in the context of online control algorithms, quantify the difference in performance between an online learning algorithm and an optimal, pre-determined controller. The goal is to design algorithms that minimize this regret, ideally achieving sublinear regret, meaning the cumulative difference grows slower than the number of interactions with the system. Analyzing regret bounds is crucial for understanding the efficiency and convergence properties of online control systems. Tight regret bounds demonstrate an algorithm’s ability to learn and adapt efficiently, offering a strong theoretical guarantee. However, the practicality and tightness of regret bounds often depend on the specific assumptions made about the system dynamics, noise characteristics (e.g., stochastic versus adversarial), and the class of admissible control policies. Therefore, a careful evaluation of these assumptions is needed when interpreting regret bounds. Furthermore, the analysis of regret bounds often involves sophisticated mathematical techniques, including those drawn from online learning, control theory, and probability. Achieving strong theoretical guarantees while maintaining practical feasibility is a significant challenge in online control research.

Future Works#

The paper’s ‘Future Works’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the methodology to systems with unknown dynamics is crucial for real-world applicability. The current reliance on known dynamics is a significant limitation. Investigating the impact of relaxing the strong convexity assumption on the cost function would enhance the algorithm’s robustness. Shifting the focus from regret to the competitive ratio would provide a different performance metric, offering additional insights. Finally, exploring more sophisticated methods for utilizing historical data in domain randomization settings is needed. This could involve time series analysis, providing a more nuanced approach to agent training in varied environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

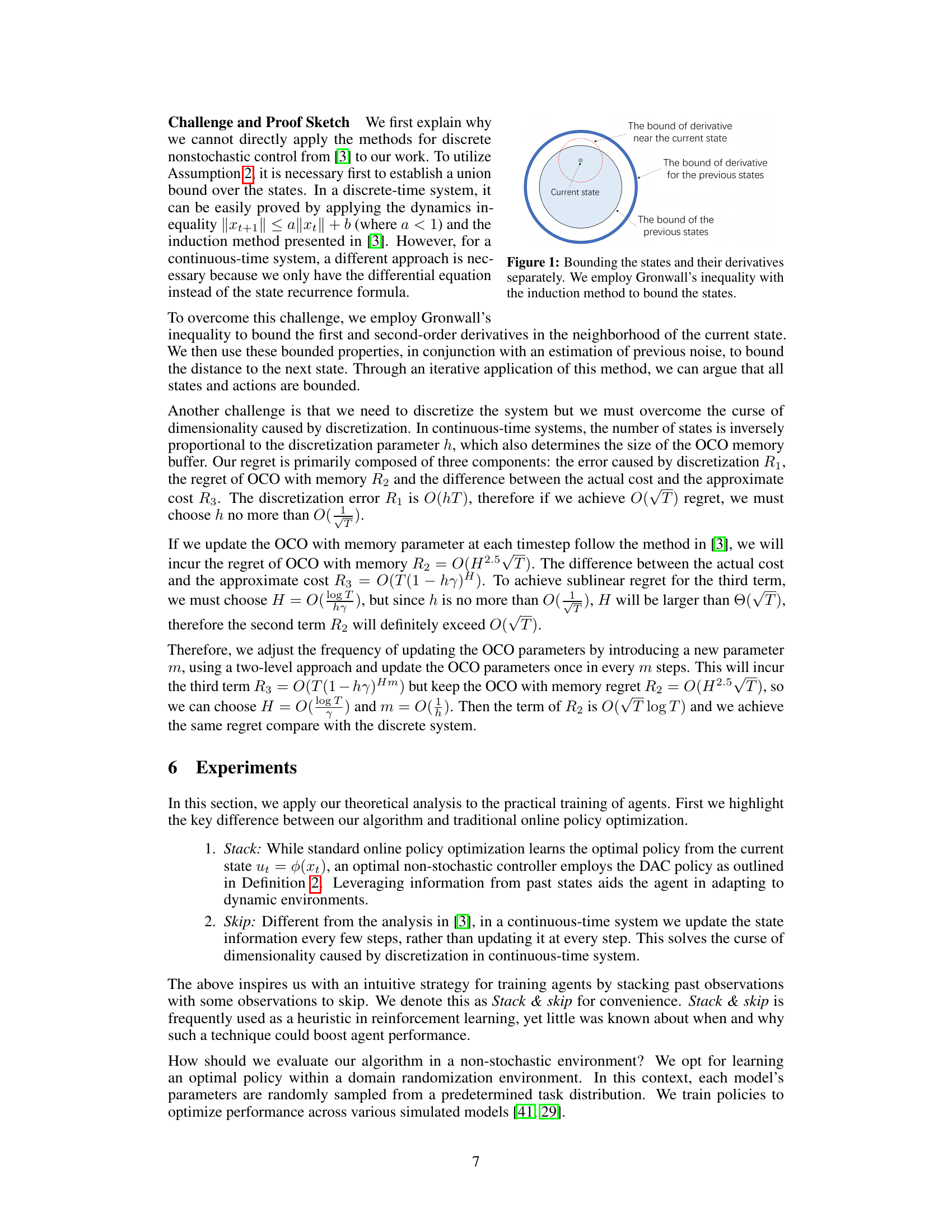

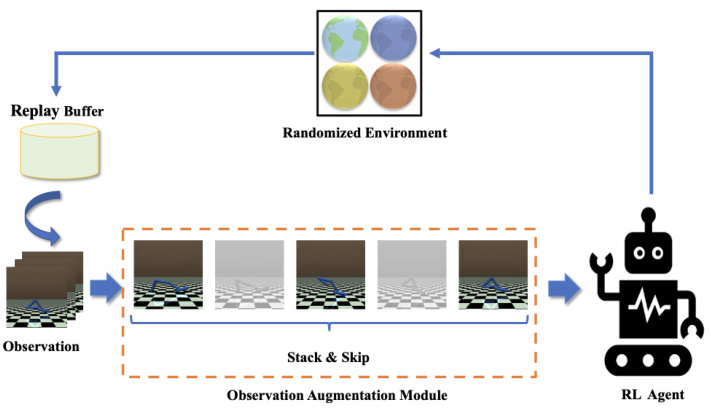

This figure shows the architecture of the proposed method. The replay buffer stores past observations. The observation augmentation module processes the observations using a stack and skip mechanism, augmenting the current observation with past observations. The augmented observation is fed to the RL agent, which interacts with the randomized environment to learn an optimal policy. This module simulates the non-stochastic environment by randomizing parameters at the start of each episode.

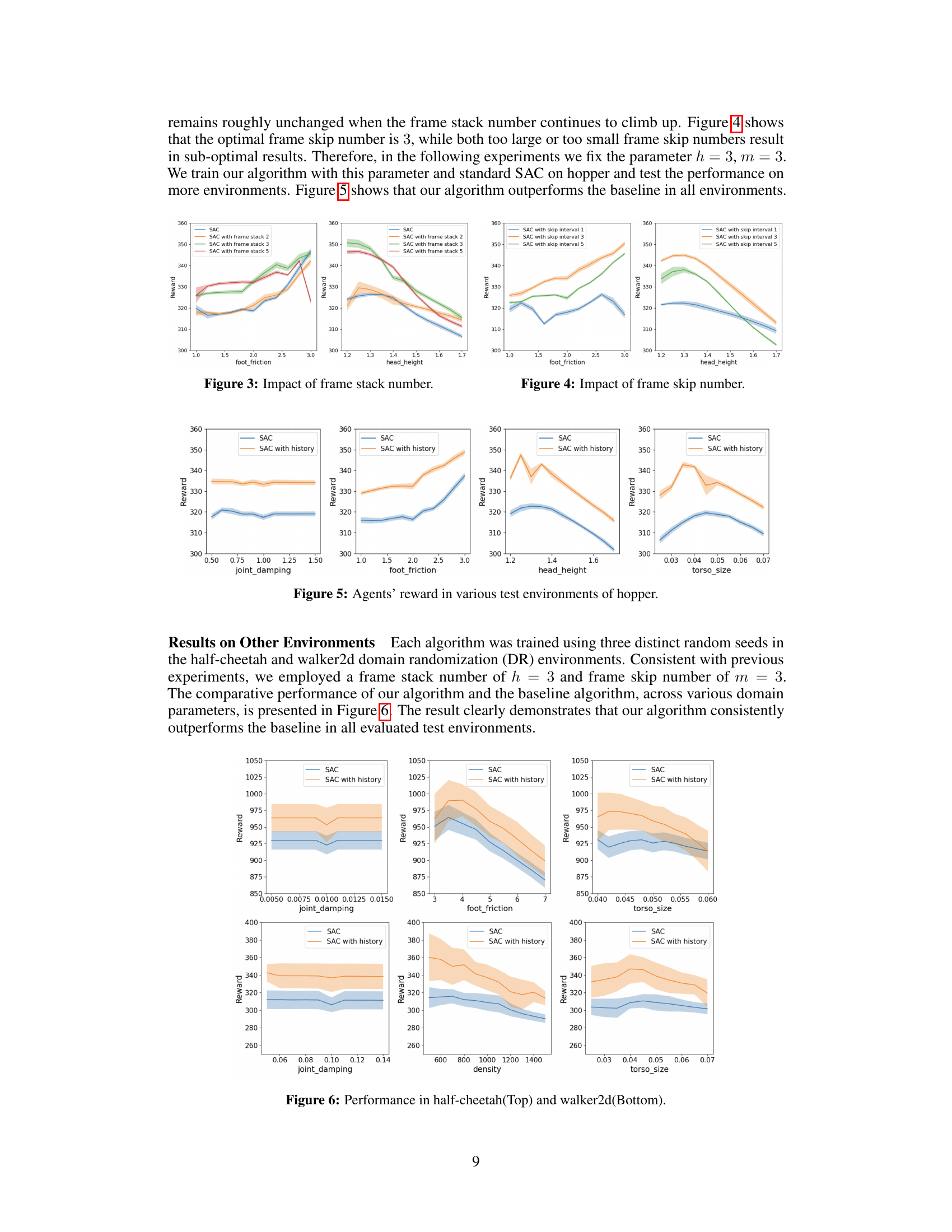

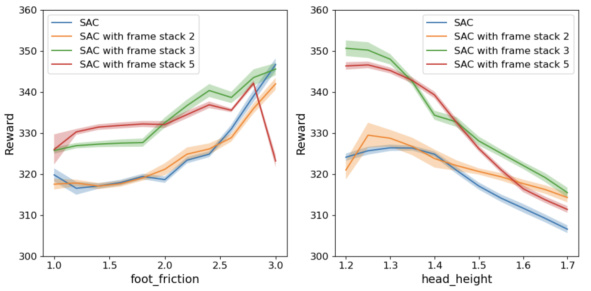

This figure shows the impact of the frame stack number on the agent’s performance in the hopper environment. The x-axis represents the foot friction parameter, and the y-axis represents the reward. Different lines represent different frame stack numbers (1, 2, 3, and 5). The shaded area around each line represents the standard deviation across multiple trials. The results suggest that increasing the frame stack number improves performance, and the optimal performance occurs with a frame stack number of 3. Using more than 3 frames does not further improve performance.

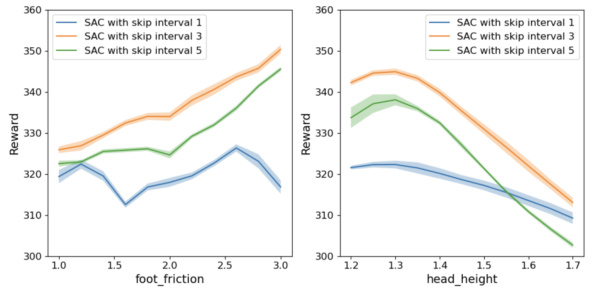

This figure shows the impact of varying the frame skip number (m) on the agent’s performance in the Hopper environment. The x-axis represents the foot friction, while the y-axis shows the average reward obtained. Three different frame skip numbers (1, 3, and 5) are compared against a standard SAC agent. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across three random seeds. The results indicate that a frame skip number of 3 yields the best performance, while both larger and smaller values result in suboptimal rewards.

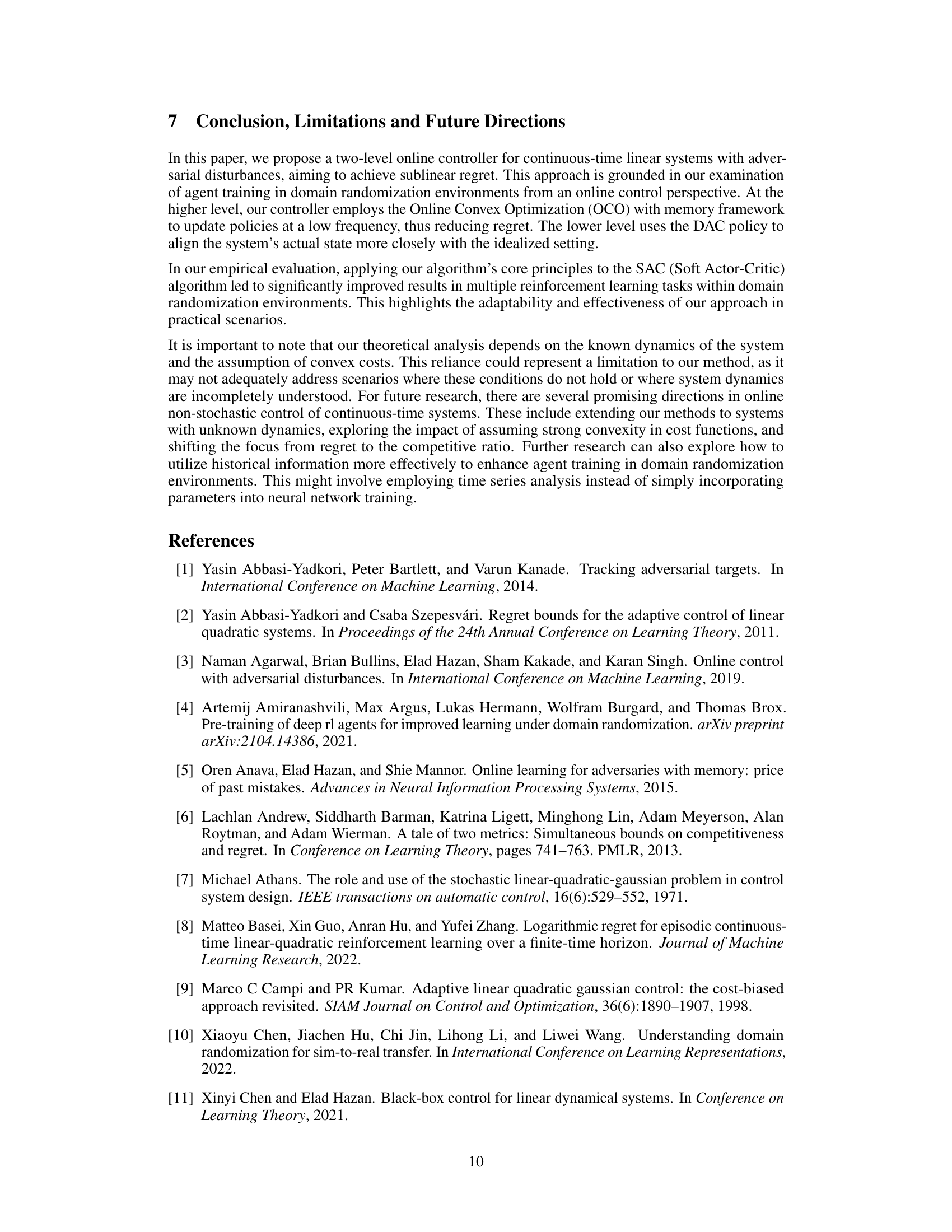

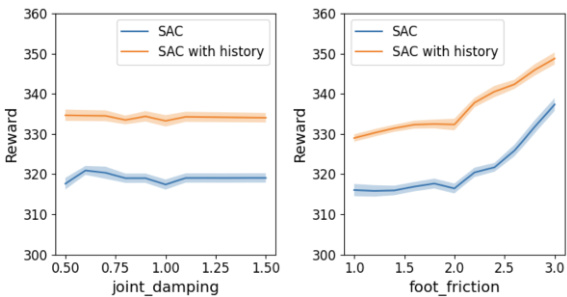

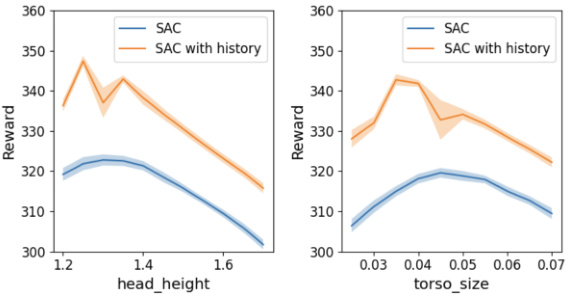

This figure displays the performance comparison between the standard SAC algorithm and the proposed SAC with history algorithm on the HalfCheetah and Walker2d environments. The x-axis represents the value of a specific domain randomization parameter (joint damping for the top row and foot friction for the bottom row), while the y-axis represents the reward achieved by each algorithm. Each data point represents the average reward obtained over three independent trials. The figure visually demonstrates that the algorithm with history consistently outperforms the baseline.

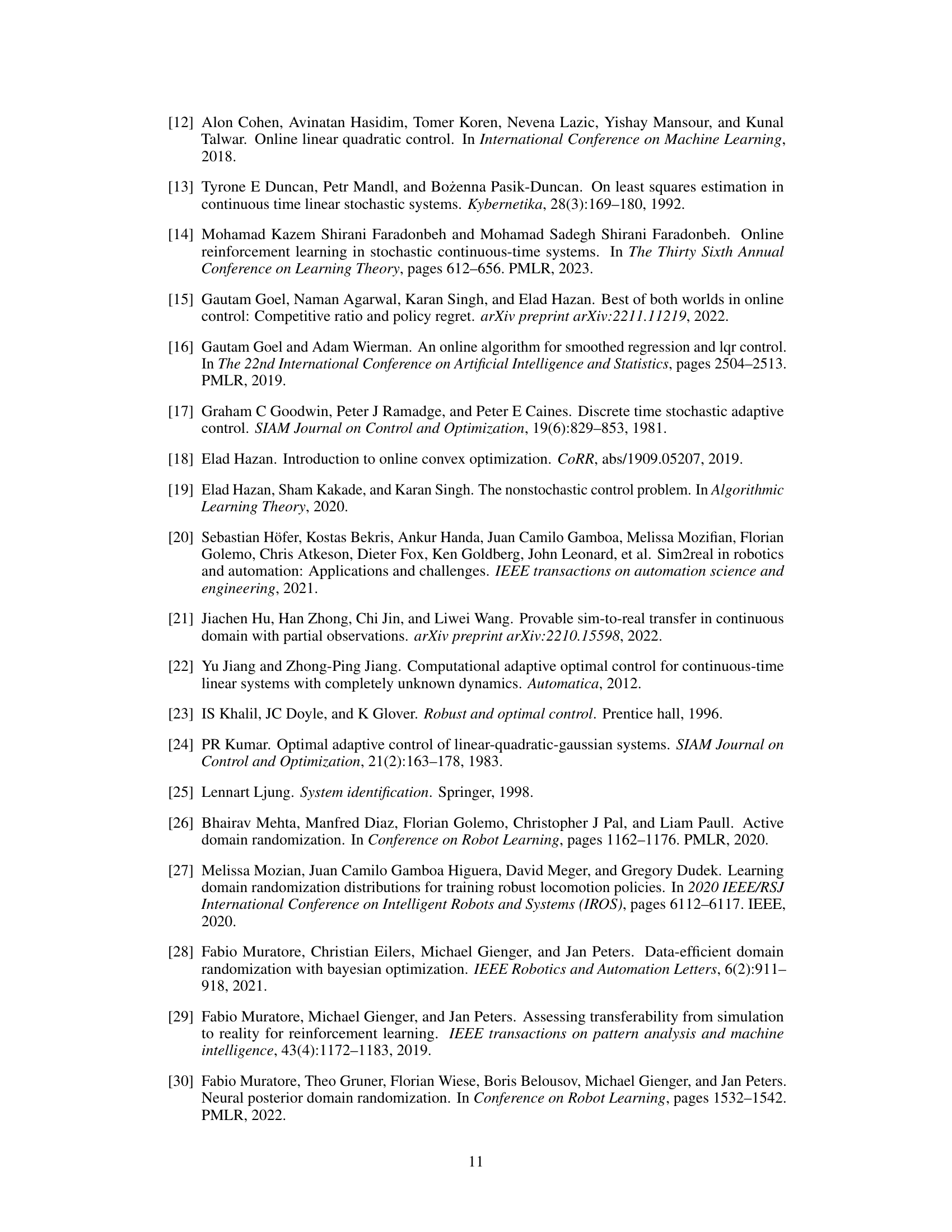

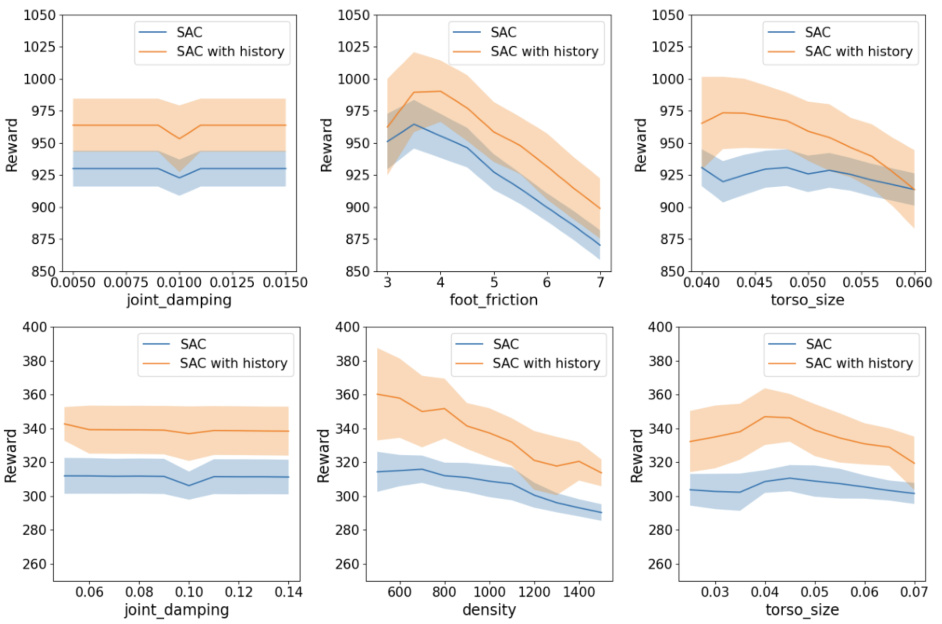

This figure shows the performance comparison between the standard SAC algorithm and the proposed algorithm with the frame stack and skip mechanism. The results are presented for two different MuJoCo environments: Half-Cheetah (top) and Walker2D (bottom). Each environment has different parameters (joint damping, foot friction, torso size, density) that are individually varied and tested, showing the reward obtained under various conditions. The shaded regions represent the standard deviation across multiple training runs.

This figure displays the performance comparison between the standard SAC algorithm and the proposed algorithm incorporating frame stacking and skipping techniques. The results are shown across three different environments (half-cheetah and walker2d) and various hyperparameter settings, showcasing the consistent superiority of the proposed algorithm in diverse conditions.

Full paper#