↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current semantic routing systems suffer from scalability issues due to their reliance on repurposing classical route optimization algorithms. These systems have limitations in handling rich user queries and diverse route criteria. This paper argues that a learning-based approach is a more effective and scalable alternative.

To address these issues, the authors introduce a large-scale public benchmark dataset for semantic routing that comprises real-world navigation tasks, user queries, and annotated road networks. They also present an autoregressive model that solves semantic routing by predicting the next edge in the route. This method demonstrates a simple yet effective way to scale up graph learning, achieving non-trivial performance even with standard transformer networks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the scalability challenges in semantic routing, a crucial area in navigation and route planning. By introducing a large-scale benchmark and a proof-of-concept autoregressive model, it offers valuable resources and insights for researchers to advance the field. The benchmark facilitates the evaluation and development of various approaches, while the autoregressive model shows promise for overcoming the difficulties of scaling up graph learning methods. This work opens new avenues for investigation in both large-scale graph learning and multi-objective route planning.

Visual Insights#

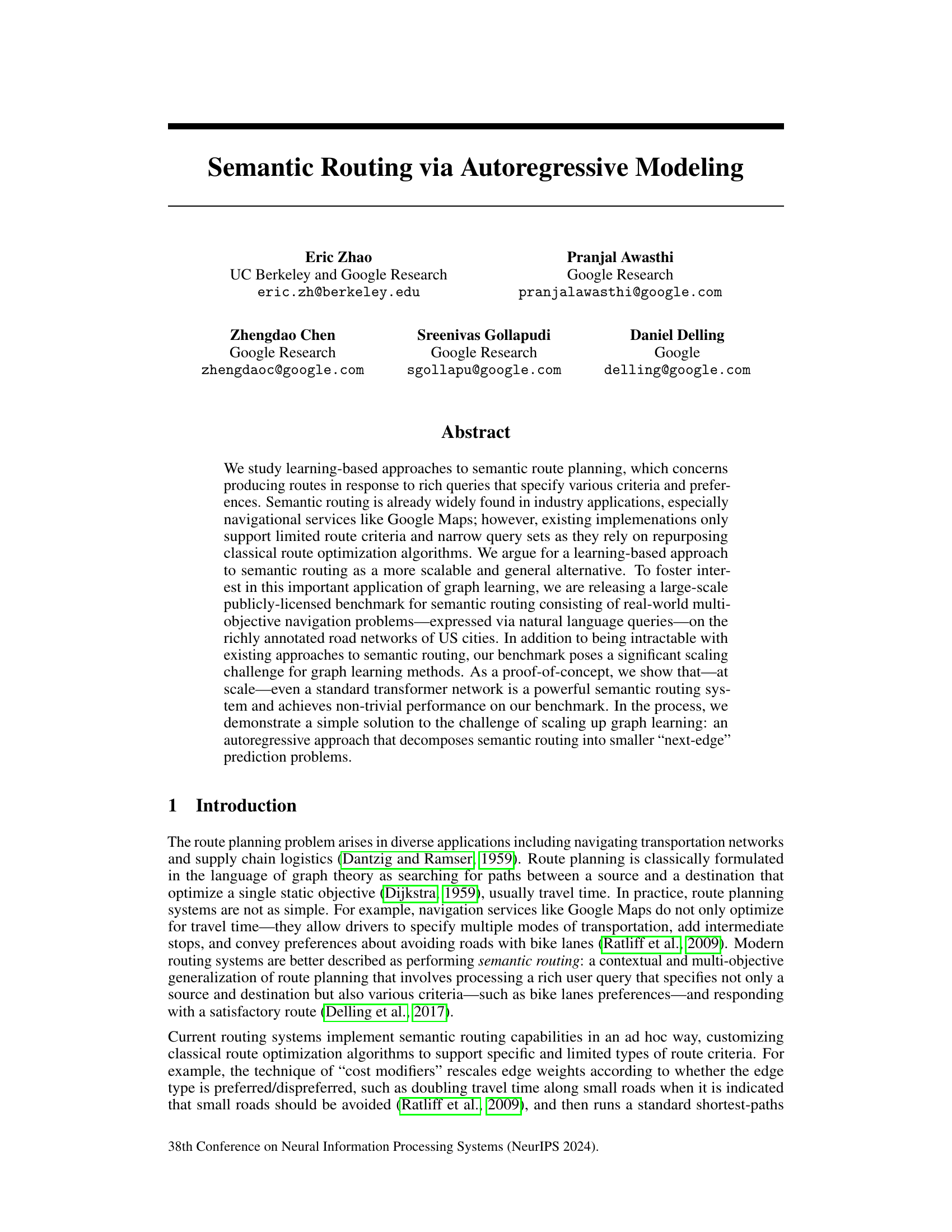

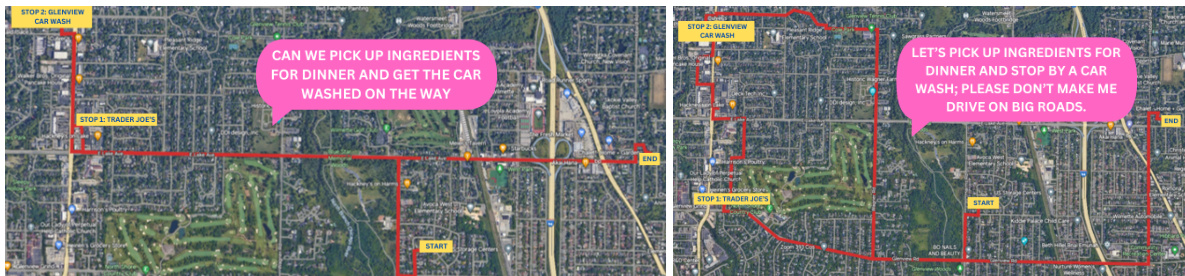

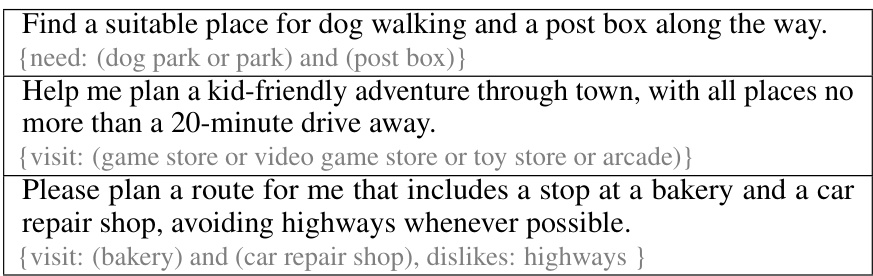

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. Each example displays a map with a route highlighted in red. The route is the optimal path identified by the researchers’ automated evaluation system. The user’s query, which specifies various criteria and preferences for the route, is shown in a pink speech bubble. These examples illustrate how the system handles nuanced user requests, incorporating factors beyond simple point-to-point navigation.

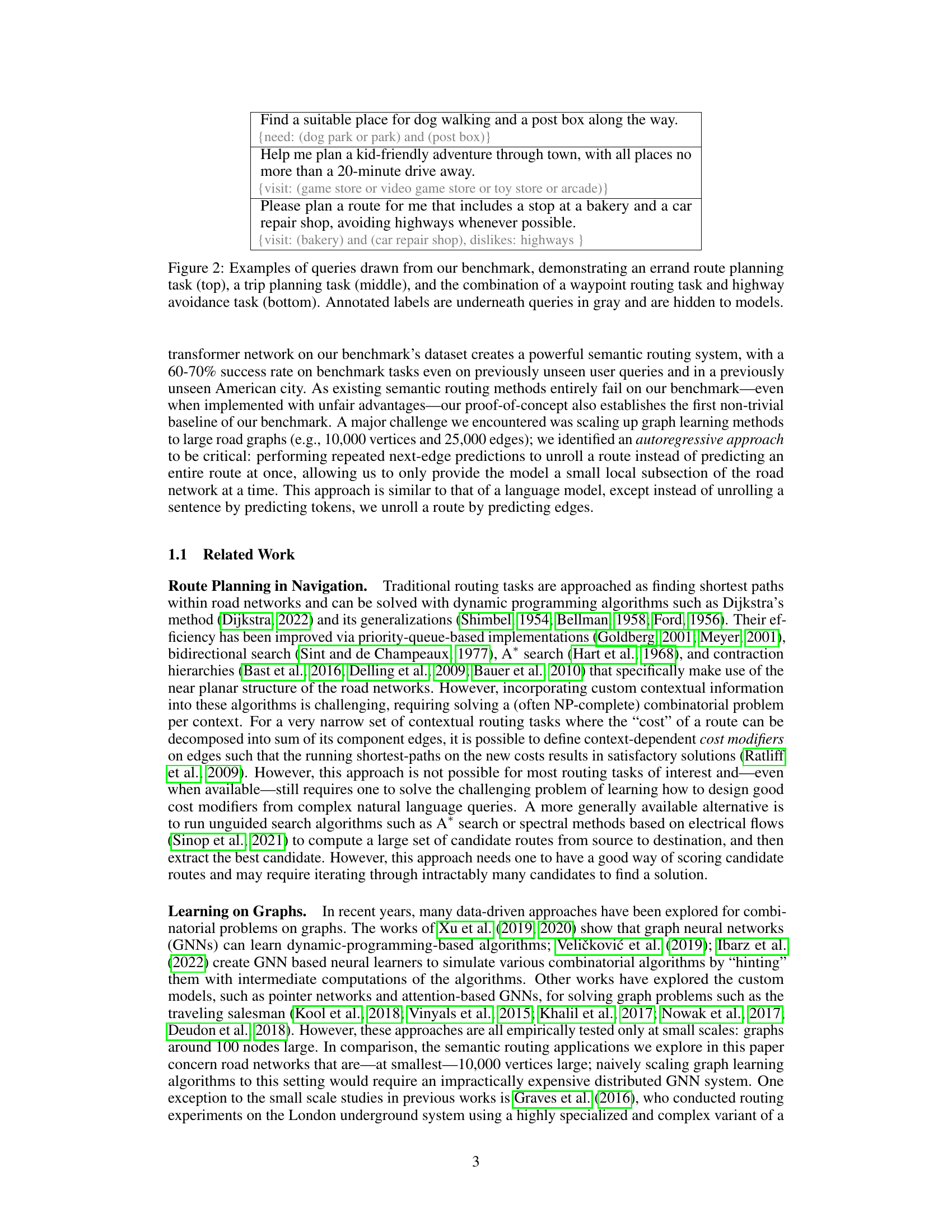

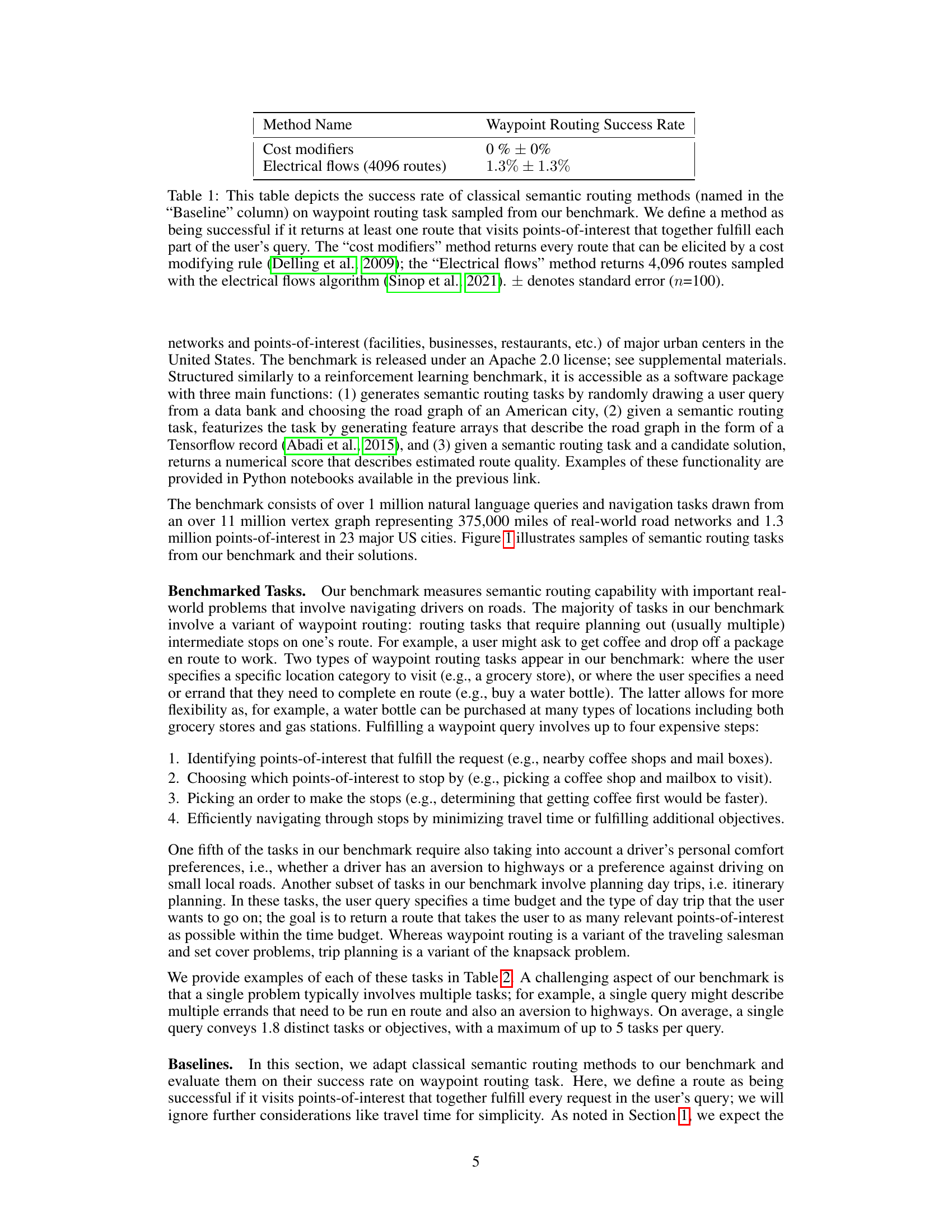

The table presents the success rate of two classical semantic routing methods (cost modifiers and electrical flows) on a waypoint routing task from the benchmark dataset. A method is considered successful if at least one of the returned routes satisfies all requirements of the user query. The results show very low success rates for both methods, highlighting the limitations of classical approaches.

In-depth insights#

Semantic Route Planning#

Semantic route planning represents a significant advancement in navigation systems, moving beyond simple shortest-path algorithms to incorporate rich contextual information and user preferences. Classical approaches often struggle with the complexity of multi-objective routing and the expressiveness of natural language queries. Learning-based methods offer a more scalable and general solution by enabling the system to learn intricate relationships between routes, user intent, and diverse criteria like preferred road types or points-of-interest. The development of large-scale benchmarks with real-world data is crucial for evaluating and advancing these learning-based techniques. However, scaling learning-based approaches to large-scale road networks presents unique challenges, motivating the need for innovative architectures such as autoregressive models that decompose the problem into smaller, manageable prediction subtasks. Overall, the field holds immense potential for enhancing user experience and enabling more sophisticated navigation applications.

Autoregressive Approach#

The autoregressive approach, decomposing the complex semantic routing problem into a sequence of smaller, more manageable “next-edge” prediction problems, offers a scalable solution to the challenges of graph learning in this domain. This method avoids the computational burden of directly predicting entire routes, making it efficient for large-scale road networks. By focusing on local neighborhoods, the approach limits the model’s input size at each step. This strategy leverages the power of autoregressive models, similar to language models, to generate a route step-by-step, proving particularly effective in handling the rich contextual information inherent in semantic routing queries. The autoregressive nature allows the model to learn complex dependencies, capturing intricate route preferences implied by natural language queries. This approach contrasts with traditional methods that rely on computationally expensive global optimizations, showcasing a significant advance in scalability and efficiency for the task of semantic routing.

Benchmark Dataset#

A robust benchmark dataset is crucial for evaluating semantic routing models. Real-world data, encompassing diverse and complex navigation tasks, is paramount. The dataset should include a variety of queries, reflecting diverse user needs and preferences. Rich graph metadata, such as road types, speed limits, and points-of-interest, is essential for evaluating performance beyond simple shortest-path calculations. The benchmark must also be scalable to accommodate large-scale road networks and diverse queries, as real-world applications involve vast amounts of data. An automated evaluation mechanism that provides objective and consistent scores is key to ensure reliable comparison of models. Furthermore, the dataset’s design should include a variety of scenarios and tasks, including those with multiple objectives and constraints, to comprehensively assess model performance. Publicly available datasets are invaluable to enable collaborative research and foster advancements in the field. A carefully constructed benchmark greatly enhances the overall value and reliability of research in semantic routing.

Scalability Challenges#

Scalability is a critical concern in semantic routing, especially when dealing with large-scale real-world road networks. Traditional methods based on classical optimization algorithms struggle to handle the complexity of rich user queries and diverse route preferences, becoming computationally expensive and difficult to extend. Learning-based approaches offer a more scalable alternative, but they also present challenges. Training deep learning models on massive graph datasets is resource-intensive, demanding significant computational power and memory. Scaling up graph neural networks (GNNs) to handle the size and complexity of road networks remains a significant hurdle. The paper addresses this through an autoregressive model, decomposing the problem into smaller subproblems, but this approach may have its own limitations as it relies on the accuracy of successive next-edge predictions. Further research is needed to explore more efficient and scalable architectures for learned semantic routing systems. Efficient feature representation and data management are crucial for scalability; improving the efficiency of input encoding and data access would enable the use of more sophisticated graph learning methods, which would potentially yield more accurate results.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the autoregressive model is crucial, potentially through investigating more advanced attention mechanisms or exploring alternative model architectures better suited for large-scale graph processing. Furthermore, exploring more sophisticated methods for handling longer routes is vital, as current approaches struggle with extended trips. This could involve incorporating hierarchical methods to reduce the complexity of the search space. The benchmark itself could be significantly expanded by increasing the diversity and complexity of queries, including scenarios beyond waypoint routing, thereby providing a more rigorous testbed for future semantic routing models. Finally, investigating alternative scoring functions beyond the current heuristic-based approach, possibly incorporating more nuanced user preferences and real-time data, would further enhance the benchmark’s utility and realism.

More visual insights#

More on figures

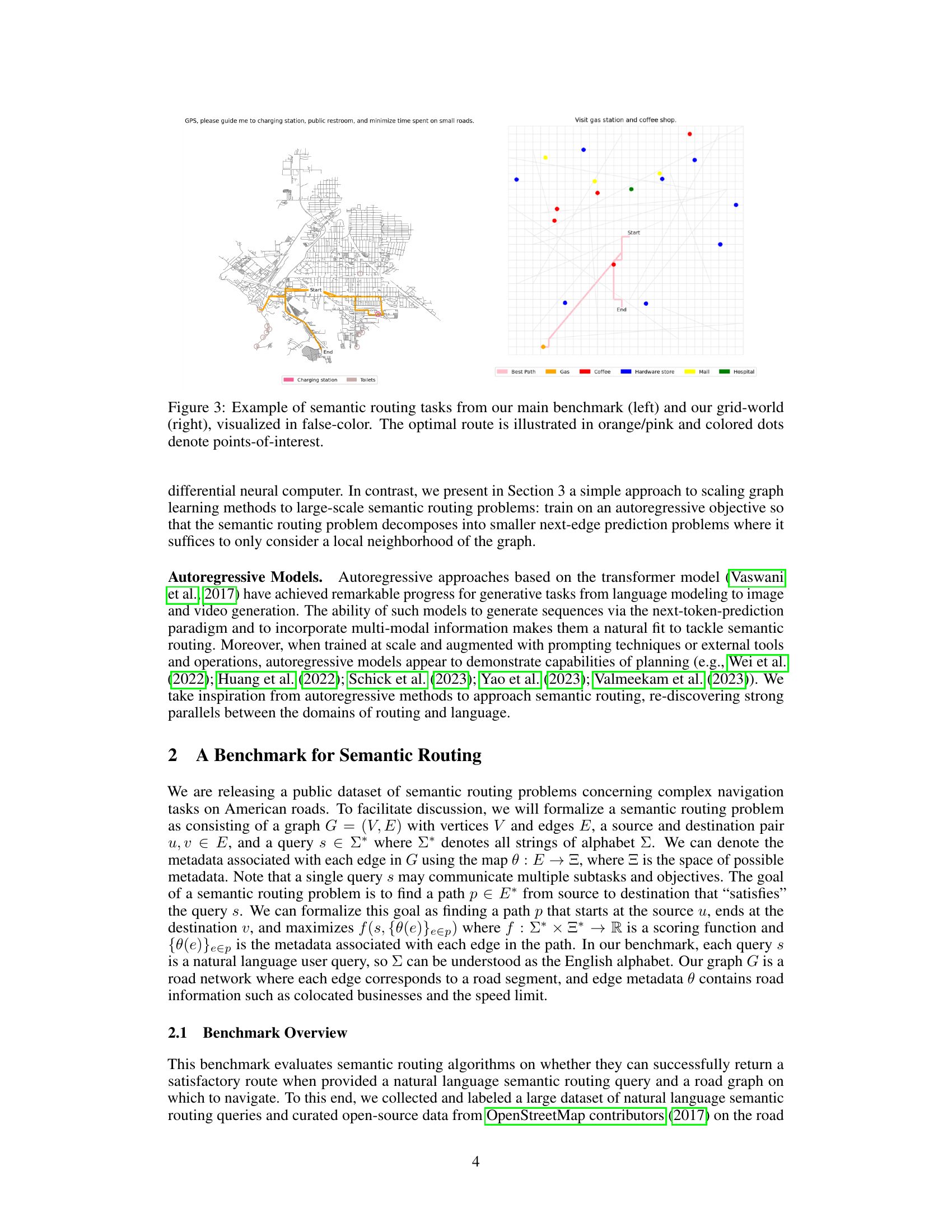

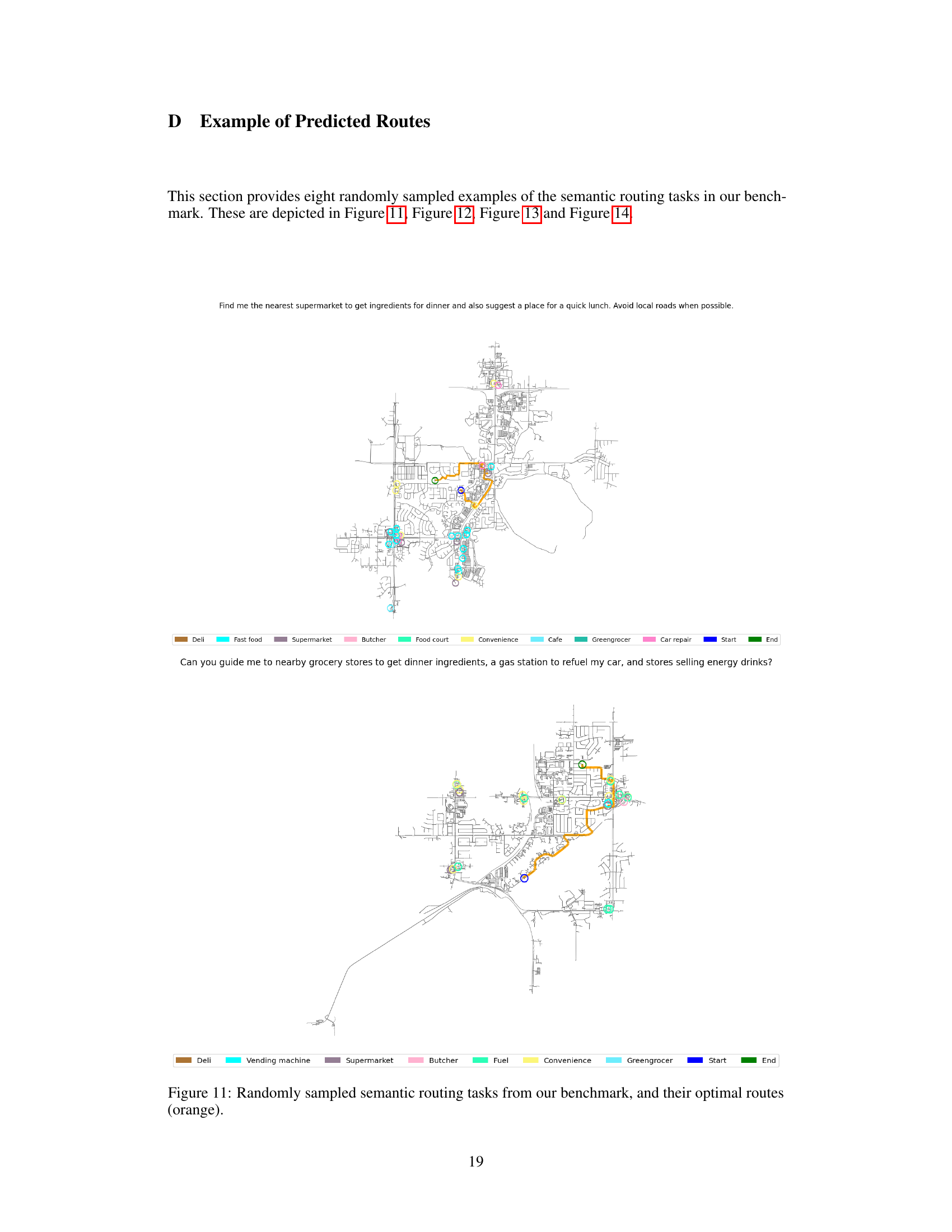

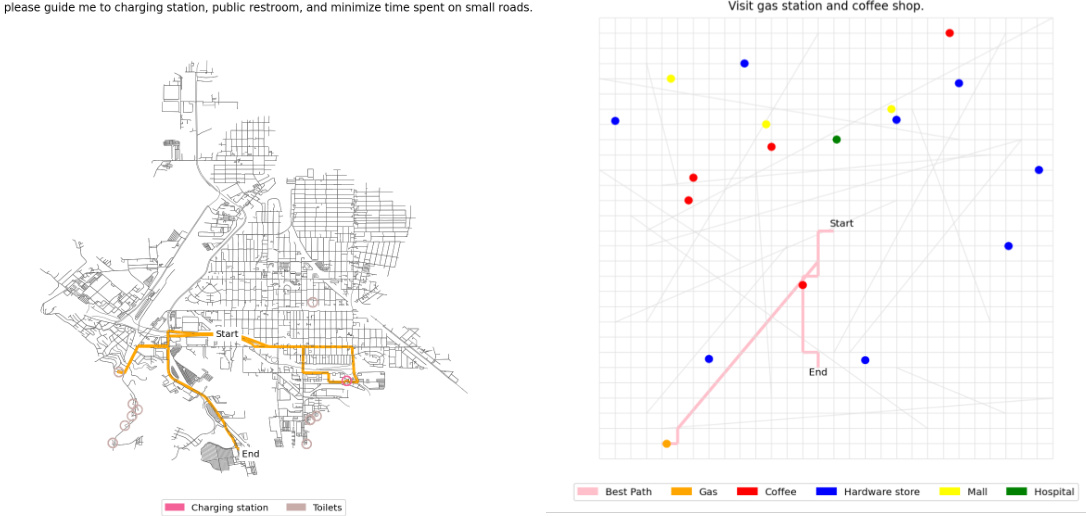

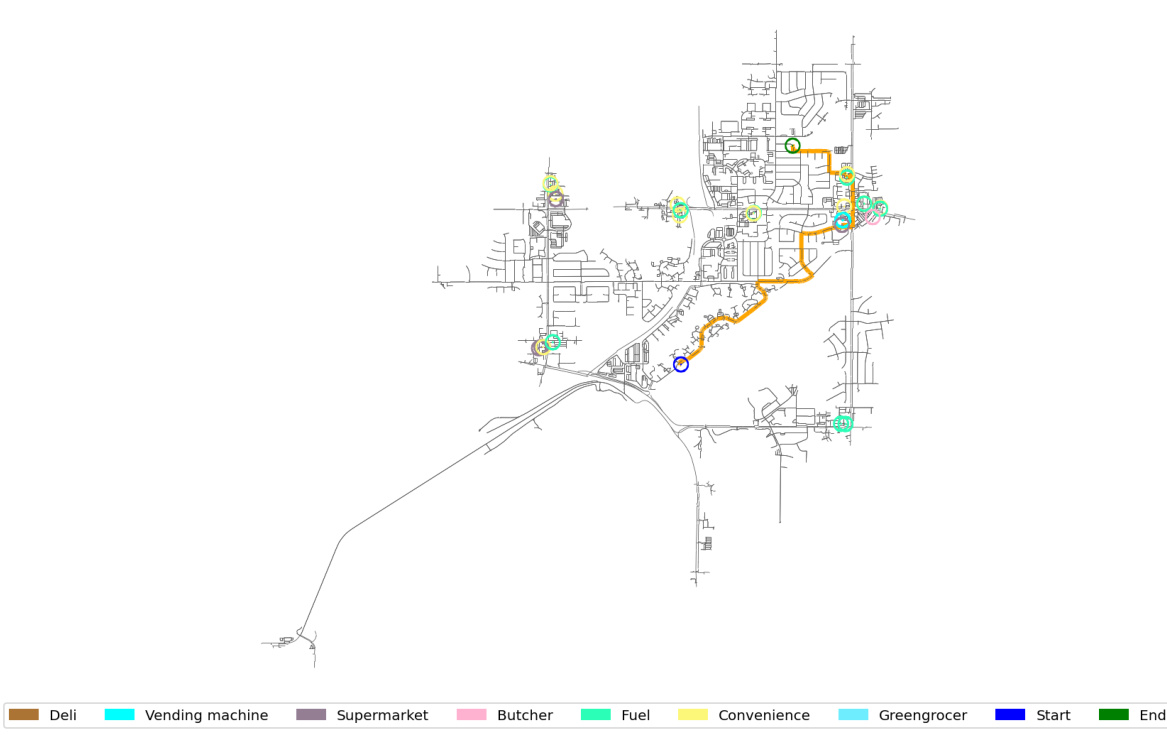

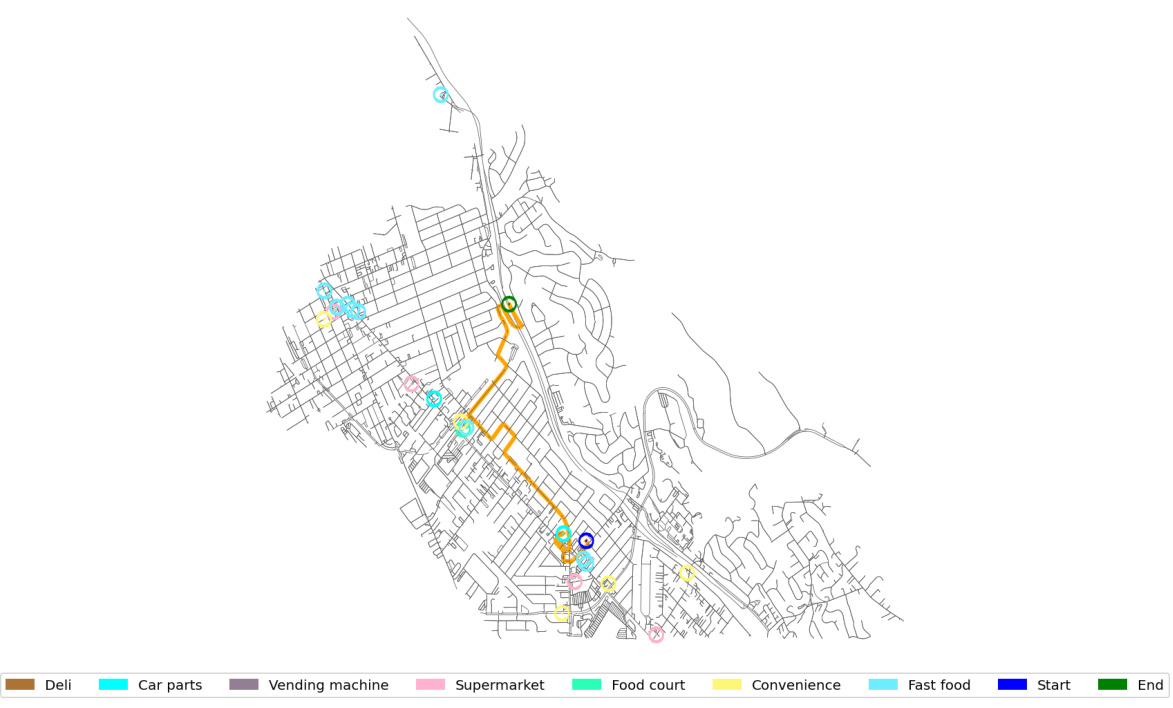

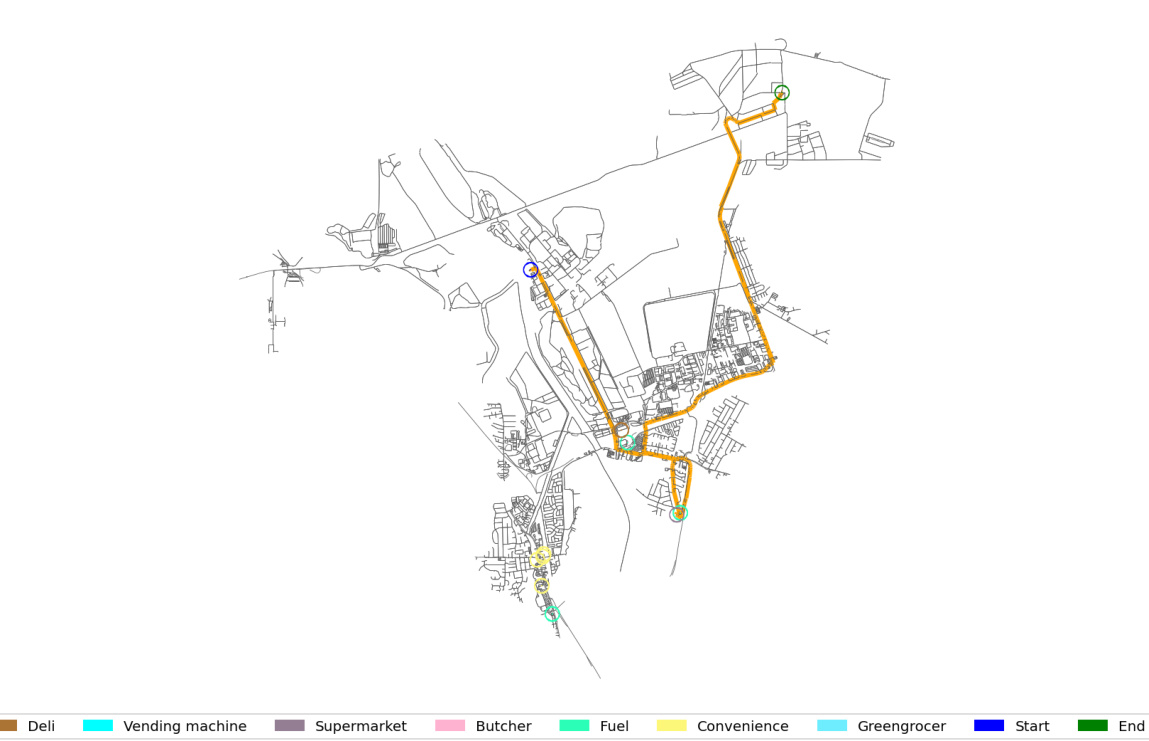

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. The left panel shows a real-world example in a road network, while the right panel shows a simplified grid-world example. In both cases, the optimal route is highlighted in orange/pink, and different points of interest are marked with different colors. The figure illustrates the complexity and diversity of semantic routing problems.

This figure details the architecture of the proof-of-concept semantic routing model, which is a transformer network trained with an autoregressive objective. The input consists of several parts: the user’s query, the destination, the route taken so far, a receptive field (a local neighborhood of the road network), and candidate edges for the next step. These inputs are embedded, processed through multiple transformer blocks, and finally produce a prediction distribution for the next edge in the route. The arrows show the flow of data through the model.

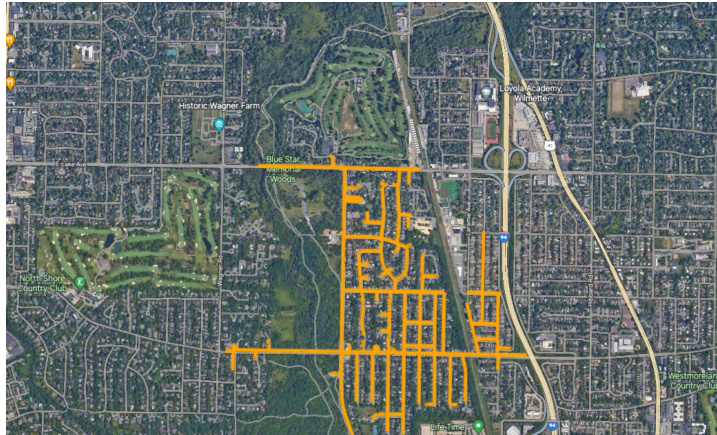

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. Each example includes a map showing the route (in red), the start and end locations, and intermediate stops. The user’s query is shown in pink, indicating the preferences and criteria specified by the user. These examples illustrate how semantic routing goes beyond simple shortest-path calculations, incorporating user preferences and constraints.

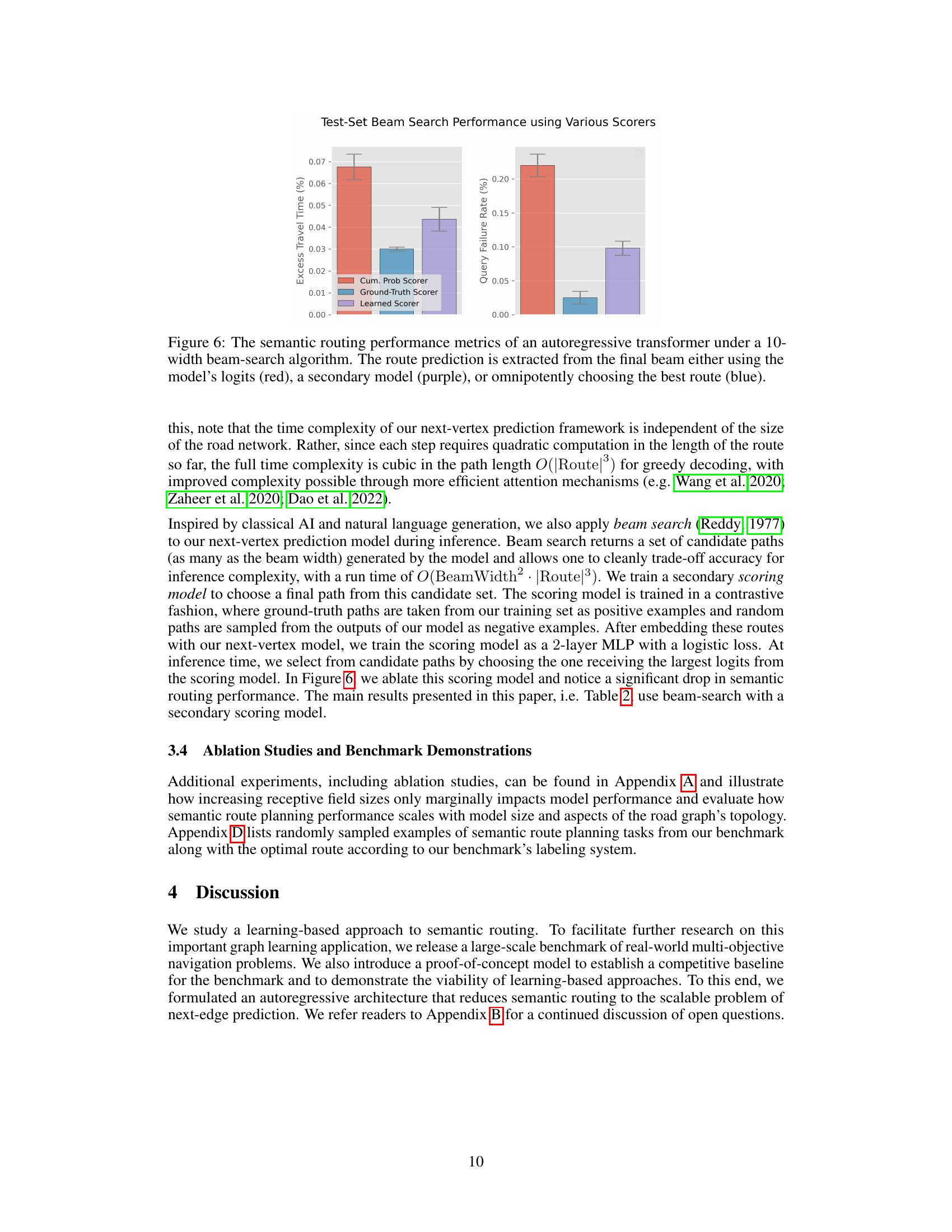

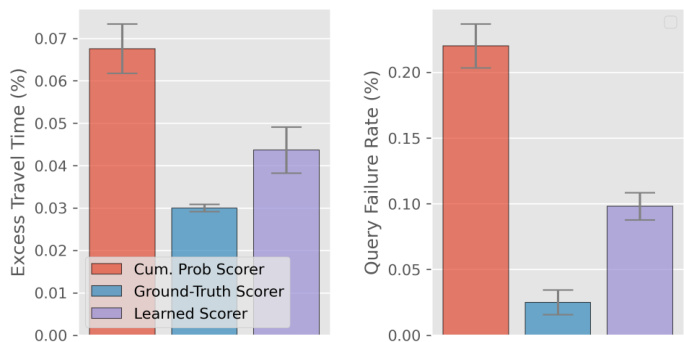

This figure compares the performance of three different scoring methods used with a beam search algorithm (width=10) for semantic route planning using an autoregressive transformer model. The three methods are: 1. Cum. Prob Scorer: Uses the cumulative probabilities from the model’s logits to select the route. 2. Ground-Truth Scorer: Uses the ground truth scores (provided in the dataset) to select the route. This serves as an upper bound on performance. 3. Learned Scorer: Uses a secondary model trained to predict good routes from the model’s outputs. This helps to alleviate the bias towards higher probability paths in the model’s logits. The figure shows two key metrics: * Excess Travel Time (%): The percentage increase in travel time compared to the optimal route. * Query Failure Rate (%): The percentage of queries for which no satisfactory route was found. The comparison helps to understand the relative effectiveness of these different scoring mechanisms, highlighting the importance of the learned scorer in improving route quality.

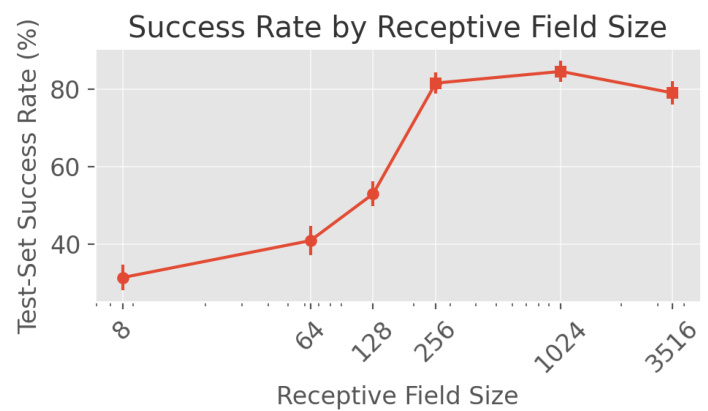

This figure shows the relationship between the size of the receptive field used in a transformer network for semantic routing and the model’s performance. The receptive field is a local area around the current position considered during the next-edge prediction. The experiment shows that performance improves significantly as the receptive field size increases until it reaches a certain point, after which increasing the size yields diminishing returns. The largest receptive field encompasses the entire road network (3516 edges). The results imply that using larger receptive fields does not significantly improve performance beyond a certain threshold, suggesting the importance of an appropriately sized receptive field in balancing model accuracy and computational efficiency.

This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating the effect of beam search width on the performance of an autoregressive transformer model for semantic routing in a grid-world environment. Two metrics are presented: excess travel time and query failure rate. The left panel shows results without a secondary scorer, and the right panel shows results with the secondary scorer. The results indicate diminishing returns from increasing beam width for both metrics.

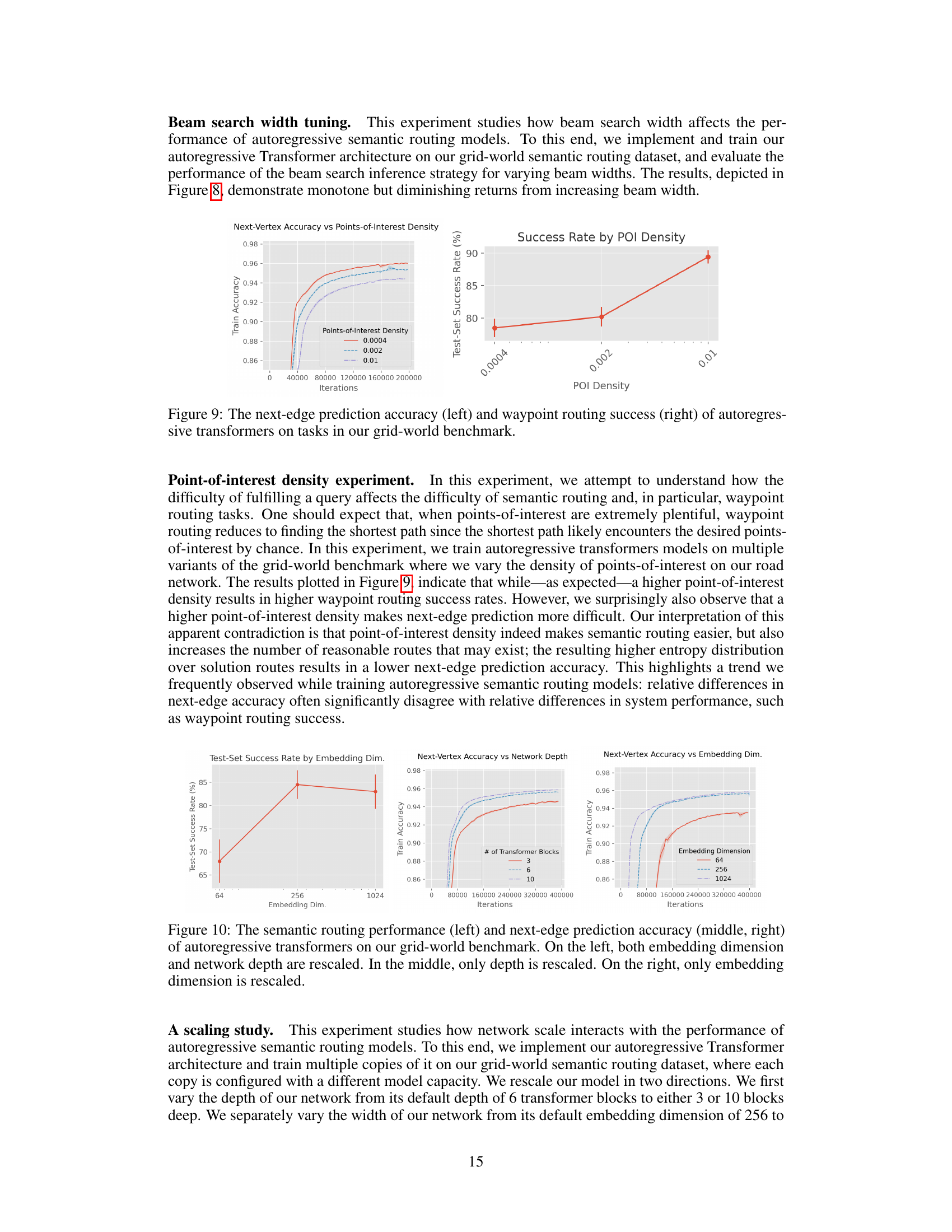

This figure shows the results of an experiment on the grid-world benchmark where the density of points-of-interest was varied. The left plot shows the training accuracy of the next-edge prediction model as a function of the number of iterations for different densities. The right plot shows the test-set success rate of the waypoint routing task as a function of the point-of-interest density. The results show that higher point-of-interest density leads to higher waypoint routing success but lower next-edge prediction accuracy.

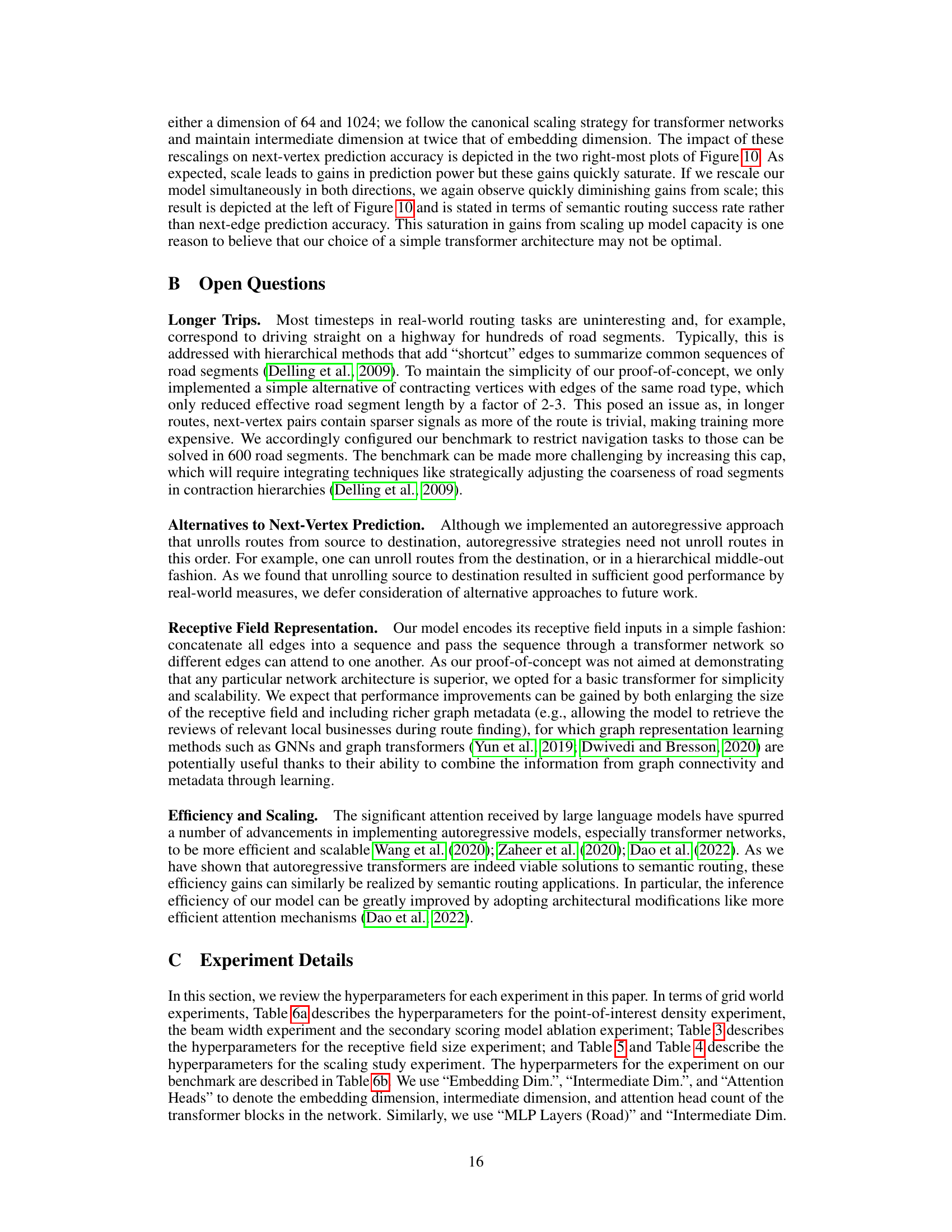

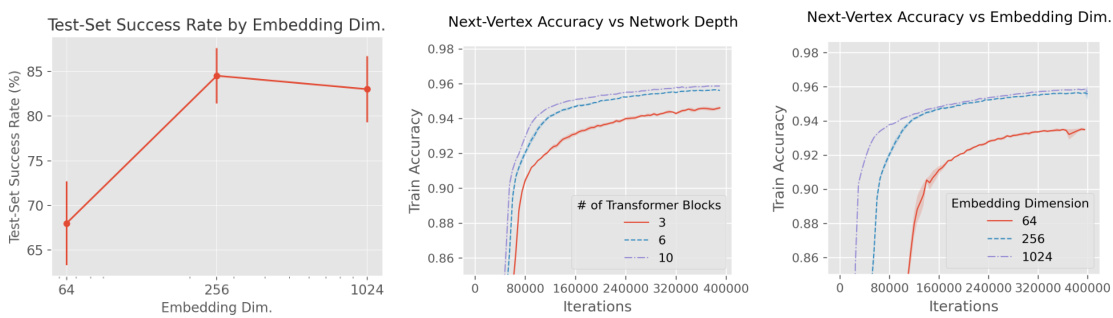

This figure shows the results of an experiment on a grid-world dataset to study how the model performance scales with network scale (depth and embedding dimension). The leftmost plot demonstrates the relationship between embedding dimension and semantic routing success rate. The middle and rightmost plots illustrate the influence of network depth and embedding dimension on next-edge prediction accuracy, respectively. The results indicate that increasing model capacity improves performance, but the gains saturate quickly.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. Each task involves navigating between two locations while fulfilling multiple criteria specified in a natural language query. The optimal route, determined by an automated evaluation system, is highlighted in orange. The left example asks for the nearest supermarket and a place for lunch while avoiding local roads. The right example asks for a route to grocery stores, a gas station, and stores selling energy drinks.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. Each example includes a map showing the route (in red) and the natural language user query (in pink). The tasks require navigating between two points while fulfilling additional criteria or preferences specified in the query, showcasing the complexity of semantic routing.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. Each example displays a road network map with a starting point and an ending point. The user’s request is shown. A path representing the optimal route is highlighted in orange. The optimal route is determined by an automated evaluation mechanism that assesses the route’s ability to fulfill the user query, factoring in multiple objectives such as visiting specific locations, avoiding certain road types, or adhering to time constraints. Different colors represent different types of points-of-interest.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. The top example shows a user request to find a supermarket and a place to buy dessert. The bottom example asks for directions to the nearest pharmacy. The optimal routes, determined by an automated evaluation system, are highlighted in orange on the map of the road networks.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. Each example displays a map section with the route visualized, the user’s query, and the optimal route highlighted. The queries include multiple criteria and preferences, such as visiting specific locations and avoiding certain types of roads. The optimal routes are generated by the automated evaluation system used in the benchmark.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. Each example displays a map section with a route (in red) plotted to satisfy a user’s natural language query (in pink). The queries include multiple objectives and criteria, making them more complex than traditional routing problems. The figure illustrates the concept of semantic routing, where routes are generated to satisfy rich user preferences instead of simply optimizing for distance or time.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. The left image displays a real-world routing task from the benchmark dataset, showing a map with an optimal route highlighted in orange/pink. Colored dots represent various points-of-interest. The right image illustrates a simpler, grid-world example, demonstrating a similar route planning scenario within a structured grid environment.

This figure shows two examples of semantic routing tasks. Each task involves navigating between two locations while fulfilling additional criteria specified in a natural language query. The optimal routes, determined by an automated evaluation system, are highlighted in orange. The map shows points-of-interest like grocery stores, gas stations, etc., and their relationship to the routes.

More on tables

This table shows the poor performance of classical semantic routing methods on waypoint routing tasks from the benchmark dataset. It compares two common techniques: cost modifiers and electrical flows. The results highlight the failure of these methods to effectively handle waypoint routing tasks, setting the stage for the proposed learning-based approach.

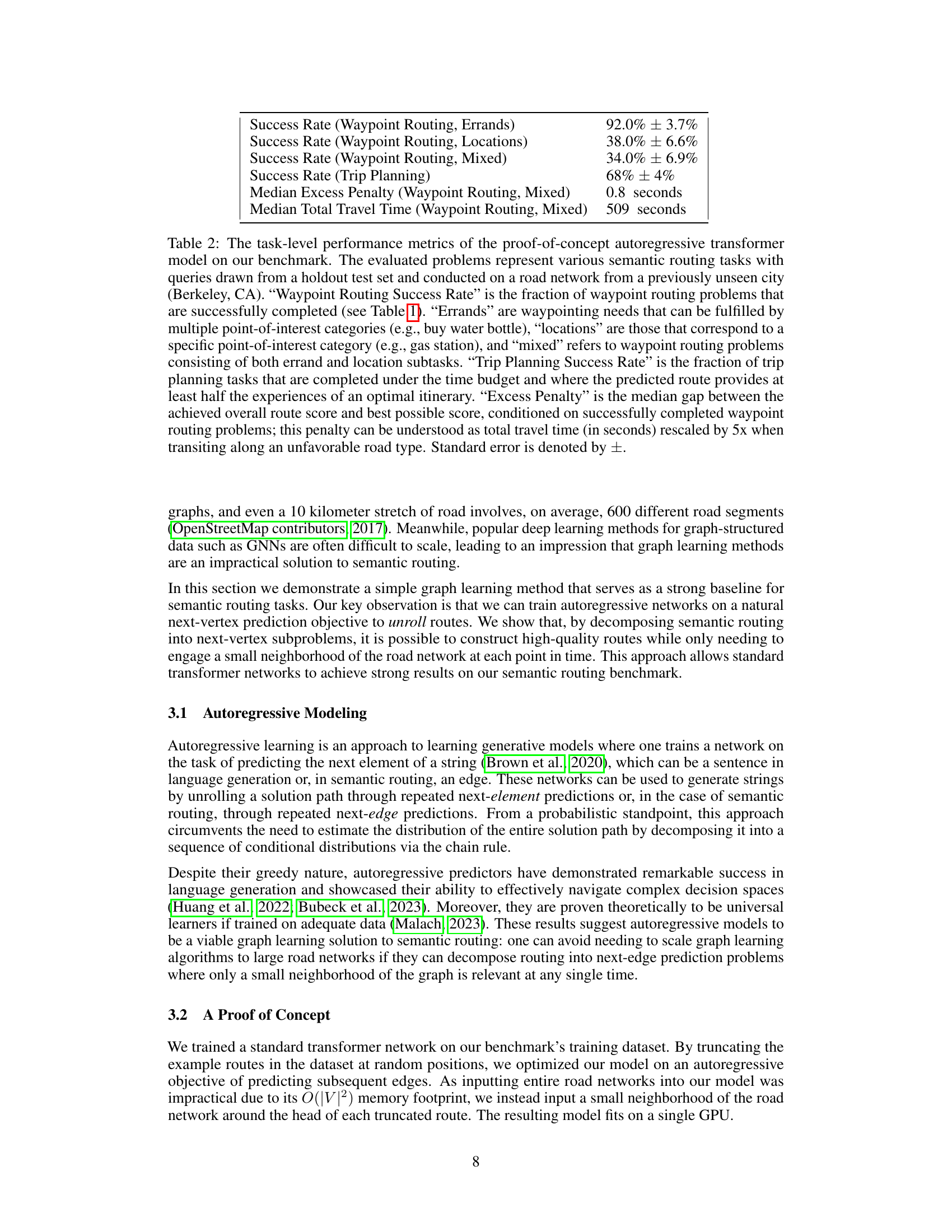

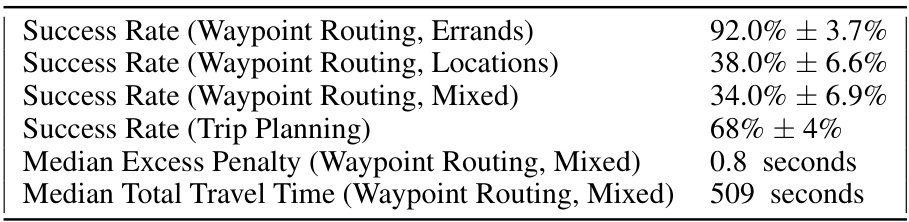

This table shows the performance of the proof-of-concept autoregressive transformer model on a held-out test set of semantic routing problems, using a road network from a city not seen during training (Berkeley, CA). The table presents success rates for different types of waypoint routing tasks (errands, locations, mixed) and trip planning tasks. It also includes the median excess penalty (additional travel time) and median total travel time for mixed waypoint routing tasks.

This table shows the poor performance of two classical semantic routing methods on a waypoint routing task from the benchmark dataset. The methods used are ‘cost modifiers’ and ’electrical flows’. The success rate is defined as whether the method returns at least one route that visits points-of-interest satisfying all parts of a user’s query. The low success rates highlight the limitations of classical methods for handling complex semantic routing tasks.

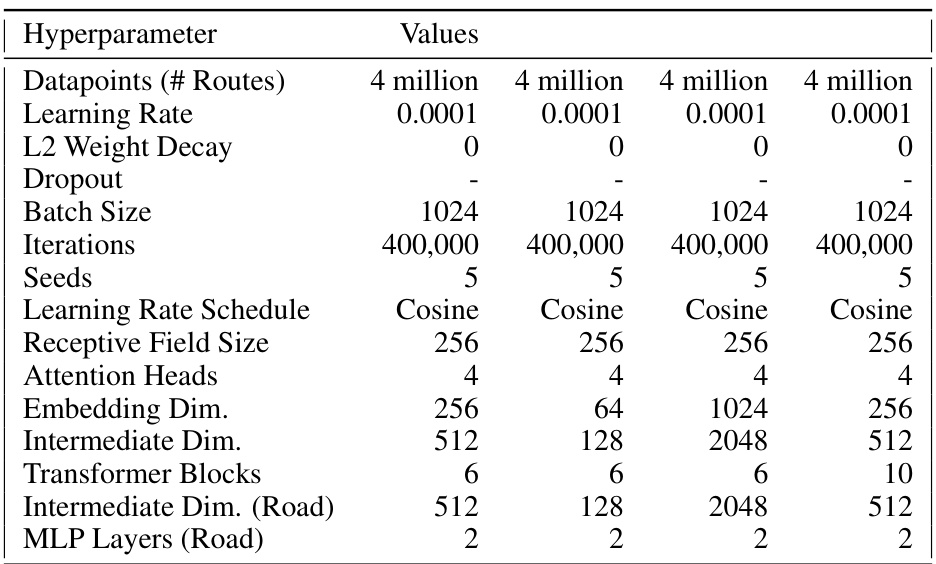

This table details the hyperparameters used in a scaling study experiment conducted on a grid-world dataset. The experiment investigated the effect of varying model size (depth and width) on the model’s performance. Different configurations are shown, each with a specified number of data points, learning rate, dropout rate, batch size, iterations, learning rate schedule, receptive field size, attention heads, embedding dimension, intermediate dimension, number of transformer blocks, intermediate dimension for road features, and number of MLP layers for road data.

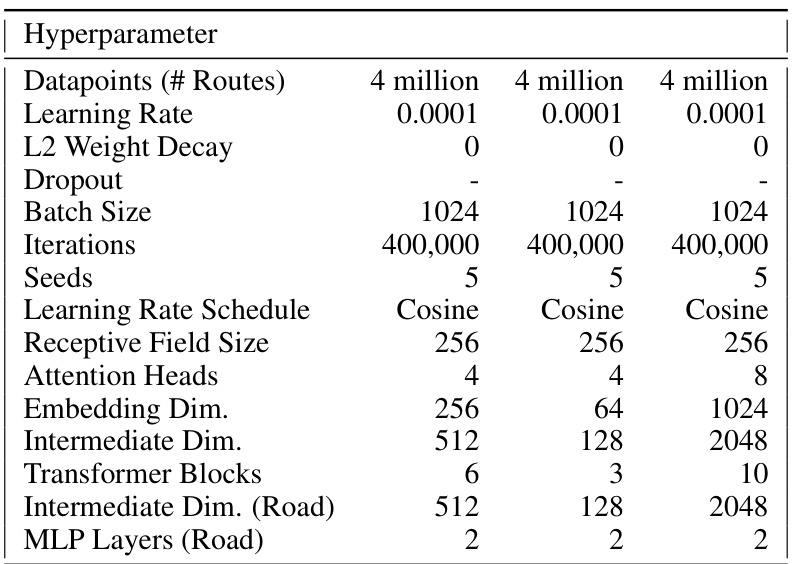

This table shows the hyperparameters used in the scaling study experiment on the grid-world dataset. The experiment varied the model’s depth and width (embedding dimension) to see how performance scaled. The hyperparameters include the number of datapoints, learning rate, L2 weight decay, dropout rate, batch size, number of iterations, seeds, learning rate schedule, receptive field size, number of attention heads, embedding dimension, intermediate dimension, number of transformer blocks, intermediate dimension for road encoding, and number of MLP layers for road encoding.

This table compares the success rates of two classical semantic routing methods on a waypoint routing task from the benchmark dataset. The methods are: 1. Cost Modifiers: This method adjusts edge weights based on user preferences and then uses a shortest-path algorithm. The success rate is reported as 0% because it failed to produce any successful routes that meet the benchmark criteria. 2. Electrical Flows (4096 routes): This method uses electrical flows to sample multiple candidate routes (4096 in this case) and checks if any satisfy the query. The success rate is reported as 1.3%, suggesting very low success using this approach. The low success rates highlight the limitations of classical methods for handling complex semantic routing tasks, setting the stage for the learning-based approach presented in the paper.

This table compares the success rate of two classical semantic routing methods against a waypoint routing task from the benchmark dataset. It shows that classical methods (cost modifiers and electrical flows) perform poorly (0% and 1.3% success rate, respectively) on this complex task, highlighting the need for a novel approach.

Full paper#