↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current reward models in Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) for Large Language Models (LLMs) suffer from poor generalization, leading to issues like reward hacking and over-optimization. This limits the effectiveness of RLHF in aligning LLMs with human intentions.

The paper introduces a novel approach called Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) that uses text-generation regularization to enhance the reward model’s generalization ability. GRM retains the base model’s language model head and incorporates text-generation losses to preserve the hidden states’ text-generation capabilities. Experimental results demonstrate that GRM significantly improves reward model accuracy on out-of-distribution tasks and effectively mitigates over-optimization, offering a more reliable preference learning paradigm.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical issue in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) for large language models (LLMs): the limited generalization ability of reward models. The proposed GRM significantly improves the accuracy and robustness of reward models, especially when training data is limited, opening new avenues for creating more reliable and aligned LLMs. This has implications for the broader field of AI safety and the development of more beneficial AI systems.

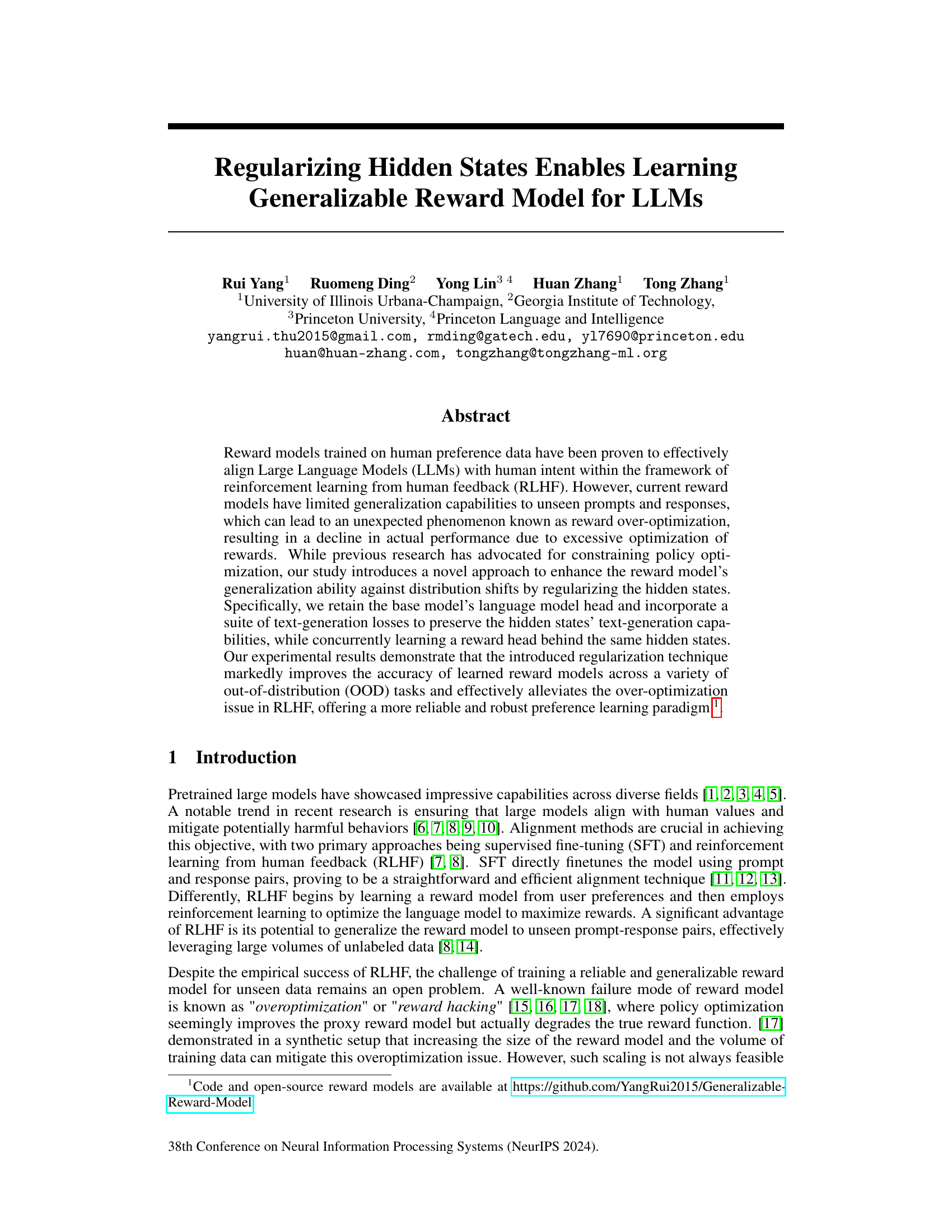

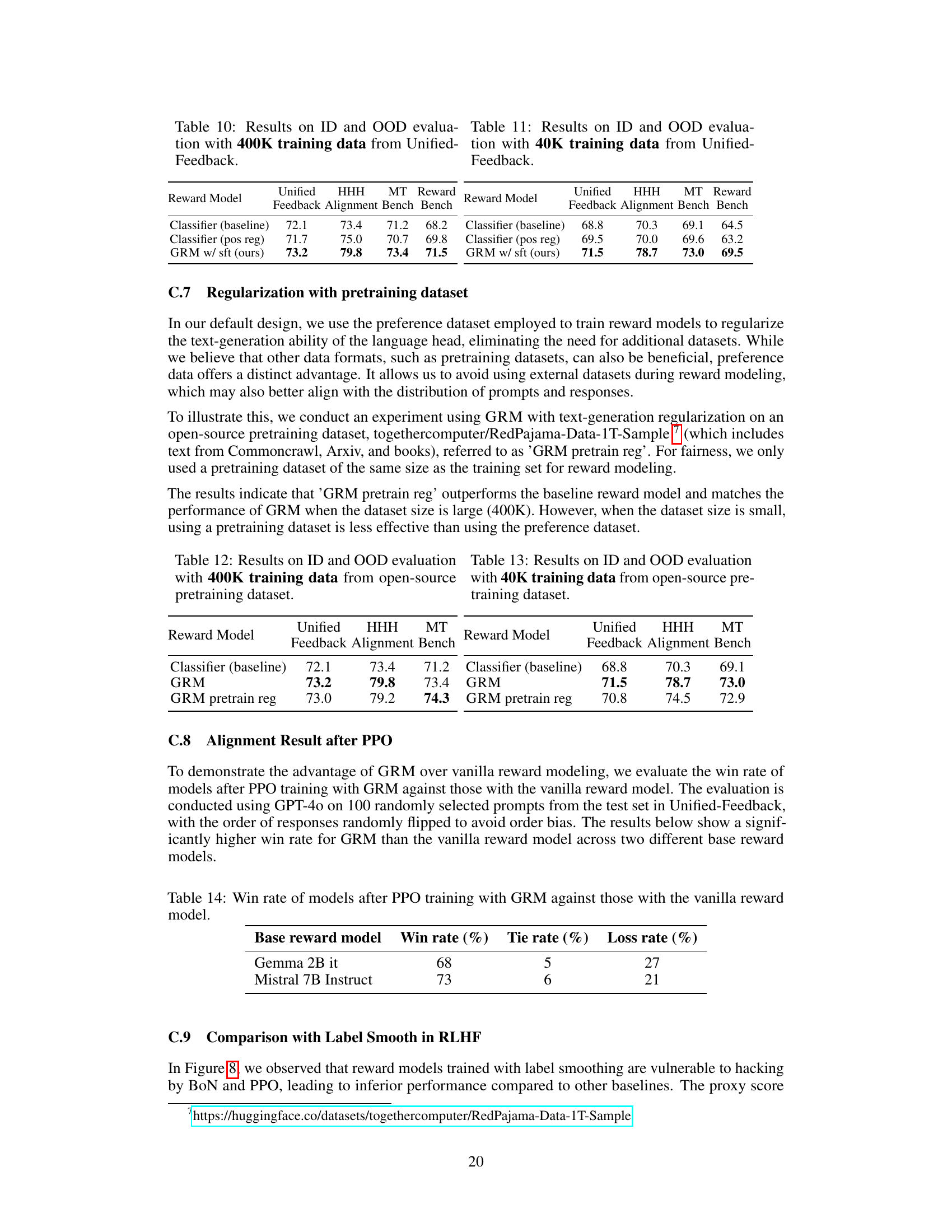

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) architecture and its performance compared to a baseline reward model. The architecture (a) shows how GRM incorporates both a reward head and a language model head, sharing the same hidden states and minimizing both reward loss and text-generation loss. The performance comparison (b) demonstrates GRM’s superior generalization ability on out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks, particularly when training data is limited. The results show that GRM consistently outperforms the baseline model on both in-distribution and OOD tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: (1) Illustration of GRM. Given preference data pairs (x, yc, yr), the reward head re minimizes the reward loss in Eq 1, while the language model (LM) head πθLM minimizes a suite of text-generation losses introduced in Sec 3.2. (2) Performance of GRM and the vanilla reward model on in-distribution (ID) task (Unified-Feedback) and average results of OOD tasks (HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench). Compared with the baseline reward model, GRM generalizes better on OOD tasks, with a larger advantage when the dataset size is relatively small.

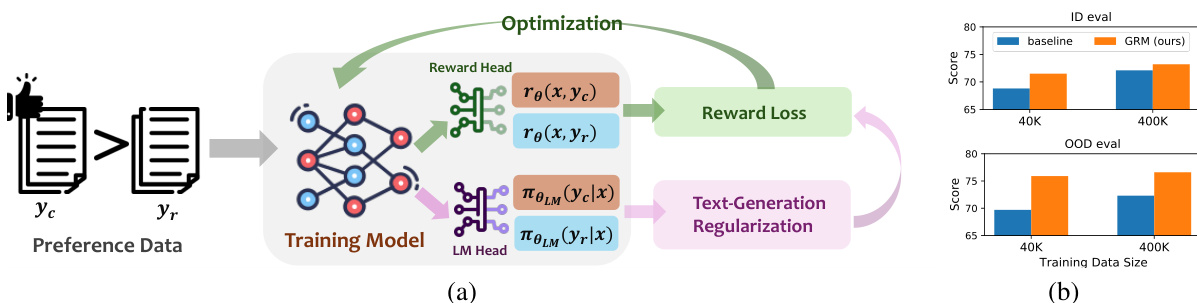

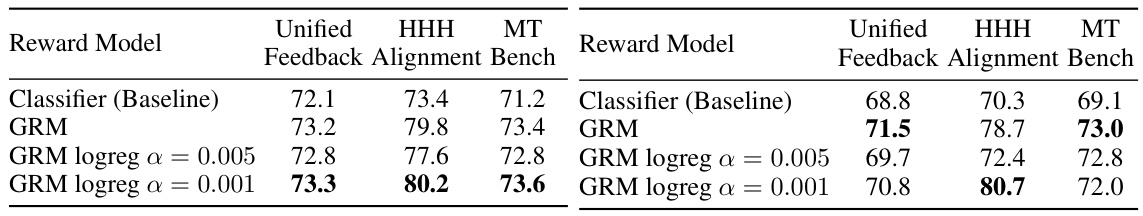

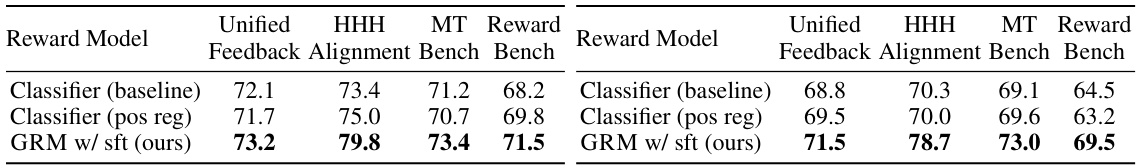

🔼 This table presents the results of the in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) evaluations using 400K training data from the Unified-Feedback dataset. It compares the performance of various reward models, including the baseline, models with margin and label smoothing, and the proposed GRM model with different regularizations. The scores for ID and two OOD tasks (HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench) are shown. The best performing model for each evaluation task is highlighted in bold, while the second-best is underlined.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

In-depth insights#

RLHF Reward Models#

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) reward models are crucial for aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. Effective reward models are key to successful RLHF, guiding the LLM to generate outputs that humans find valuable and safe. However, a significant challenge is that current reward models often struggle with generalization to unseen prompts and responses, leading to reward hacking or over-optimization. This means the model might excel at optimizing the reward signal itself, rather than truly capturing and reflecting human preferences. The paper explores the potential for regularization techniques in the reward model, particularly focusing on hidden state regularization, to improve generalization performance and address the problem of over-optimization. This focus on improving the model’s ability to generalize is a key step towards creating more robust and reliable LLMs. In essence, the paper aims to improve reward model’s generalization performance and ensure it acts as a better proxy for human preferences, thus making RLHF more effective and safe.

Hidden State Reg.#

Regularizing hidden states in reward models offers a novel approach to enhance the generalizability of LLMs. By incorporating text generation losses alongside reward optimization, this technique prevents the distortion of pre-trained features caused by random initialization of reward heads. This mitigates reward over-optimization, a common issue where the model focuses excessively on proxy rewards at the expense of genuine alignment with human intent. Maintaining the hidden states’ language generation capabilities is crucial for ensuring that the model retains its base functionalities. The method’s effectiveness has been demonstrated across various out-of-distribution tasks, suggesting its potential as a robust and reliable preference learning paradigm for LLMs. Lightweight and adaptable, this method doesn’t require multiple reward model training or additional data, making it practical for real-world applications.

OOD Generalization#

Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization is a crucial aspect of reward model training for large language models (LLMs). Reward models trained on human preference data are susceptible to over-optimization, failing to generalize well to unseen prompts and responses. This paper addresses this challenge by regularizing the hidden states of the reward model, preserving their text-generation capabilities while simultaneously learning a reward head. This method enhances the model’s ability to generalize to OOD data. The regularization technique significantly improves the accuracy of reward models on a variety of OOD tasks, demonstrating robust generalization performance. This is a significant step towards developing more reliable and robust preference learning paradigms for aligning LLMs with human intent. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed regularization, particularly in data-scarce scenarios, where the improvement over baseline models is substantially larger. The success of this approach suggests that a focus on feature preservation during fine-tuning is key to achieving better OOD generalization. This opens avenues for more reliable and generalizable reward models in RLHF.

Overoptimization#

Overoptimization in reward models for large language models (LLMs) is a critical challenge. It occurs when the reward model is excessively optimized to a proxy reward, leading to unintended and harmful behaviors in the LLM. The model may achieve high scores on the proxy reward but fail to align with true human values, such as safety or helpfulness. This phenomenon undermines the effectiveness of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Several strategies to mitigate overoptimization exist, including constraining policy optimization or enhancing the generalization of the reward model, which is the focus of the study. Regularizing hidden states is presented as a novel approach to improve reward model generalization. The core idea is to retain the language model head’s text-generation capabilities while simultaneously learning a reward head. This method offers a lightweight yet effective solution to prevent the distortion of pre-trained features by the randomly initialized reward head and enhances the reward model’s performance across various tasks and datasets. Furthermore, by effectively alleviating overoptimization, the method offers a more reliable and robust paradigm for preference learning in RLHF.

Future of RLHF#

The future of RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) hinges on addressing its current limitations. Improved reward model generalization is crucial; current models often struggle with unseen prompts and responses, leading to suboptimal policies. More robust and efficient reward model training techniques are needed, potentially incorporating techniques like meta-learning or adversarial training to enhance generalization and reduce overfitting. Scalability remains a significant concern; current RLHF methods can be computationally expensive, hindering application to very large language models. Therefore, research into more efficient algorithms and architectures is vital. Finally, better methods for handling biases and inconsistencies in human feedback are crucial for ensuring the fairness and safety of RLHF-trained systems. Addressing these issues is key to unlocking the full potential of RLHF and creating more aligned and beneficial AI systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

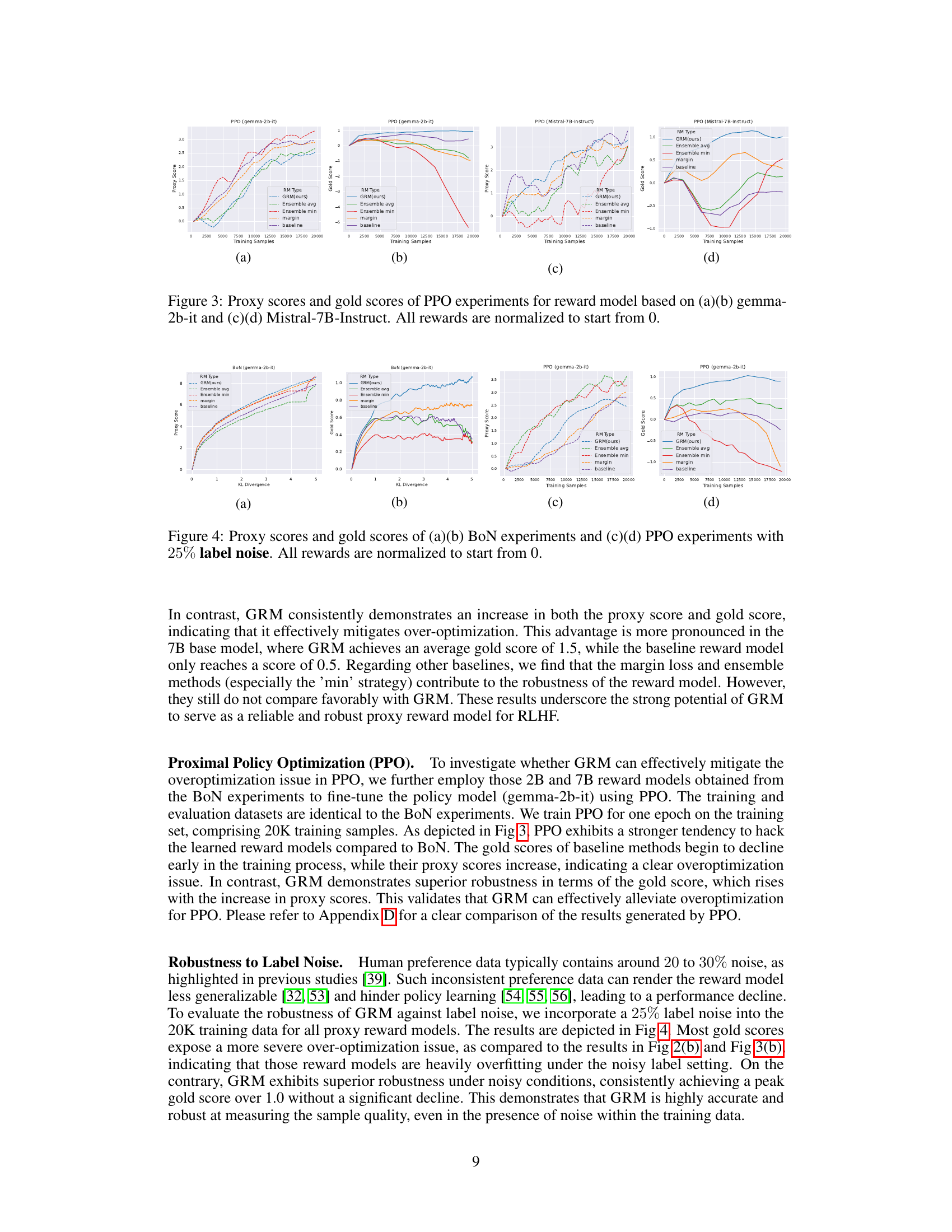

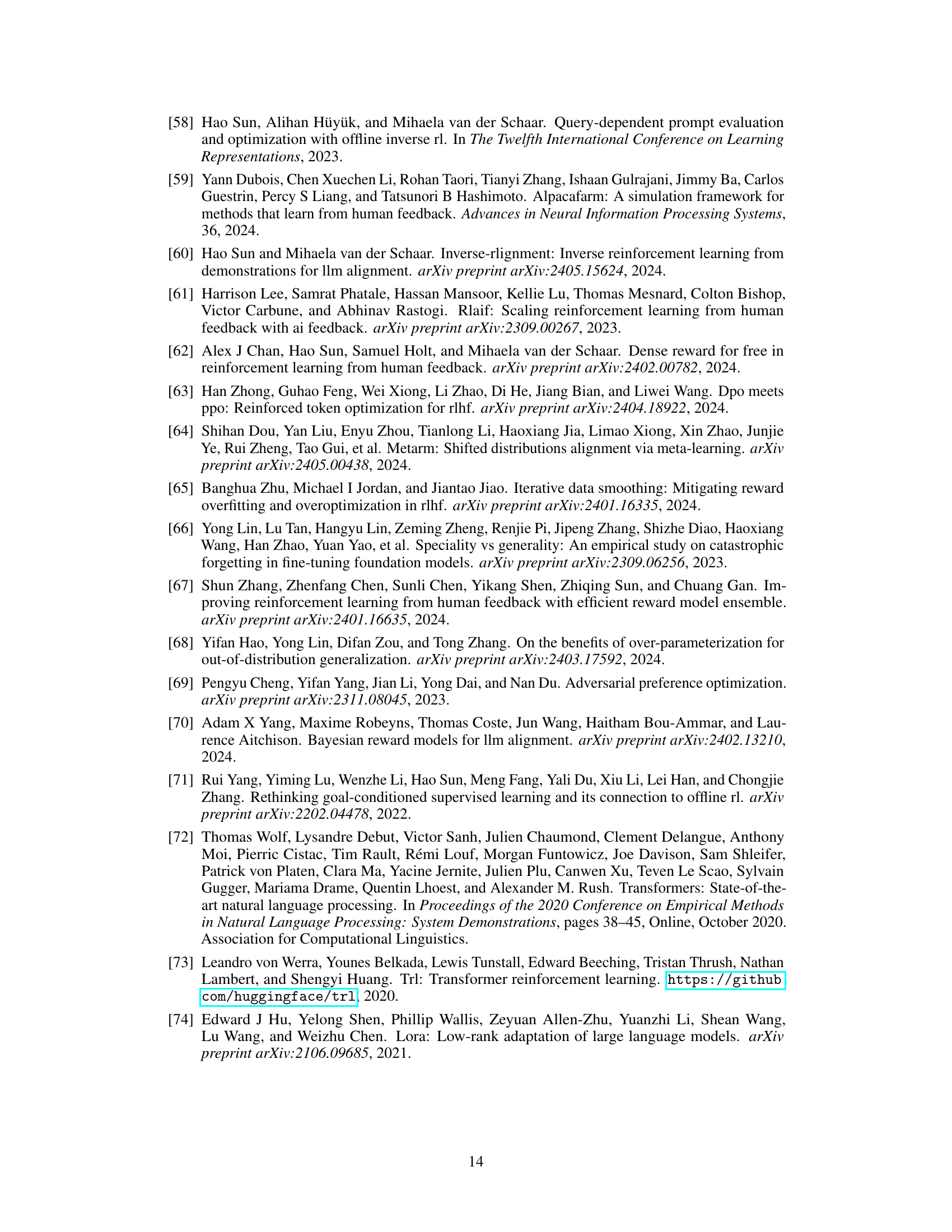

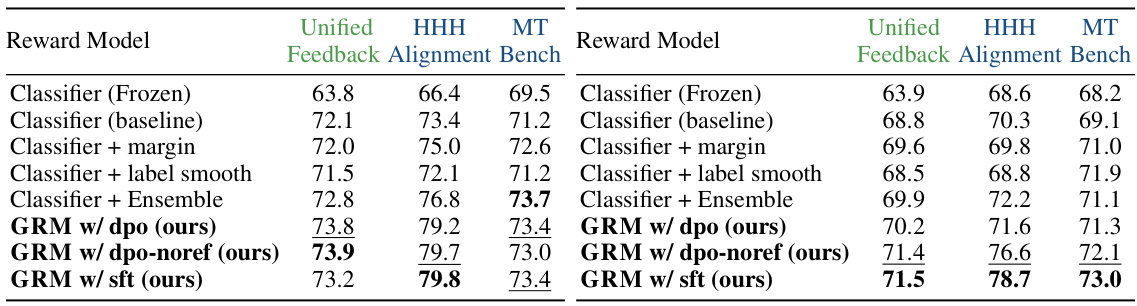

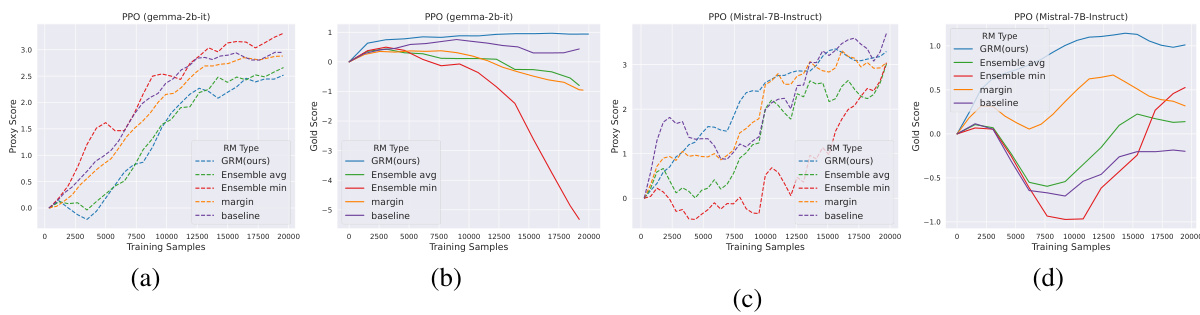

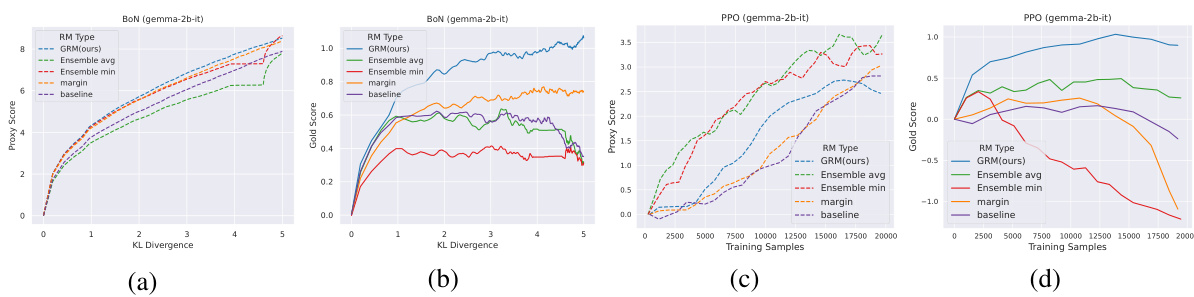

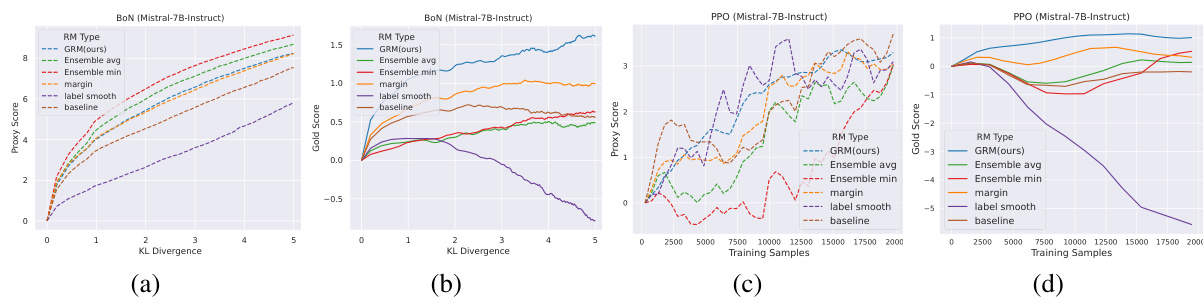

🔼 This figure shows the results of best-of-n (BoN) sampling experiments using two different base language models: gemma-2b-it and Mistral-7B-Instruct. The x-axis represents the KL divergence, which increases with the number of samples considered in BoN. The y-axis shows both proxy scores (predicted by the reward model) and gold scores (actual human preferences). The dashed lines represent proxy scores, and the solid lines represent gold scores. The figure demonstrates that GRM (the proposed method) consistently selects better responses that are more closely aligned with human preferences (gold scores) than the baseline methods, especially as the KL divergence increases, showcasing its robustness and ability to generalize to unseen data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Proxy scores and gold scores of BoN experiments for base models of (a)(b) gemma-2b-it and (c)(d) Mistral-7B-Instruct. Proxy and gold scores are in dashed and solid curves, respectively. Rewards are normalized to start from 0. GRM demonstrates a robust ability to select the best response aligned with the gold rewards as the KL Divergence increases.

🔼 This figure shows the results of Best-of-N (BoN) sampling experiments for two different language models (gemma-2b-it and Mistral-7B-Instruct). It compares the performance of the proposed Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) against several baseline reward models. The x-axis represents the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which is a measure of the difference between the policy model’s distribution and the reference model’s distribution. The y-axis shows both proxy scores (model’s predicted rewards) and gold scores (human-evaluated rewards), normalized to start at 0. The figure demonstrates that GRM consistently selects better responses, as measured by gold scores, even when the KL divergence increases and there is a larger difference between the policy and reference models. This highlights GRM’s robustness in choosing high-quality responses.

read the caption

Figure 2: Proxy scores and gold scores of BoN experiments for base models of (a)(b) gemma-2b-it and (c)(d) Mistral-7B-Instruct. Proxy and gold scores are in dashed and solid curves, respectively. Rewards are normalized to start from 0. GRM demonstrates a robust ability to select the best response aligned with the gold rewards as the KL Divergence increases.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of GRM with several baseline methods on best-of-n (BoN) sampling for two different base models (gemma-2b-it and Mistral-7B-Instruct). The x-axis represents the KL divergence, which is a measure of the difference between the model’s policy and the reference policy. The y-axis represents the proxy score (the score assigned by the reward model) and the gold score (the score assigned by human evaluators). The figure shows that GRM consistently selects responses with higher gold scores as the KL divergence increases, indicating its robustness and ability to generalize well to unseen data. In contrast, the baseline methods often fail to select the best responses as the KL divergence increases, suggesting that they are more susceptible to over-optimization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Proxy scores and gold scores of BoN experiments for base models of (a)(b) gemma-2b-it and (c)(d) Mistral-7B-Instruct. Proxy and gold scores are in dashed and solid curves, respectively. Rewards are normalized to start from 0. GRM demonstrates a robust ability to select the best response aligned with the gold rewards as the KL Divergence increases.

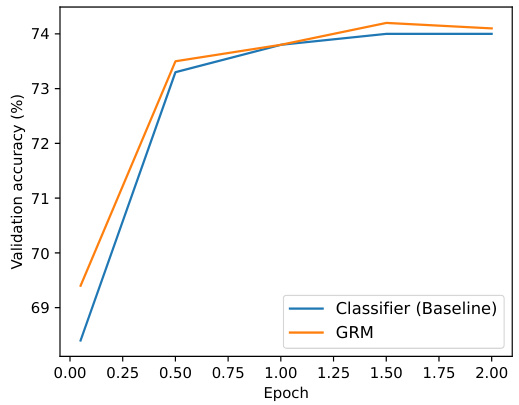

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves for two reward models trained on the Unified-Feedback dataset. The blue line represents the baseline reward model, while the orange line represents the proposed GRM model. The x-axis represents the number of epochs, and the y-axis represents the validation accuracy. The figure demonstrates that the GRM model converges faster and achieves a higher validation accuracy compared to the baseline model. This suggests that the GRM model is more effective in learning reward functions from human feedback data.

read the caption

Figure 5: Learning curves for reward models on Unified-Feedback.

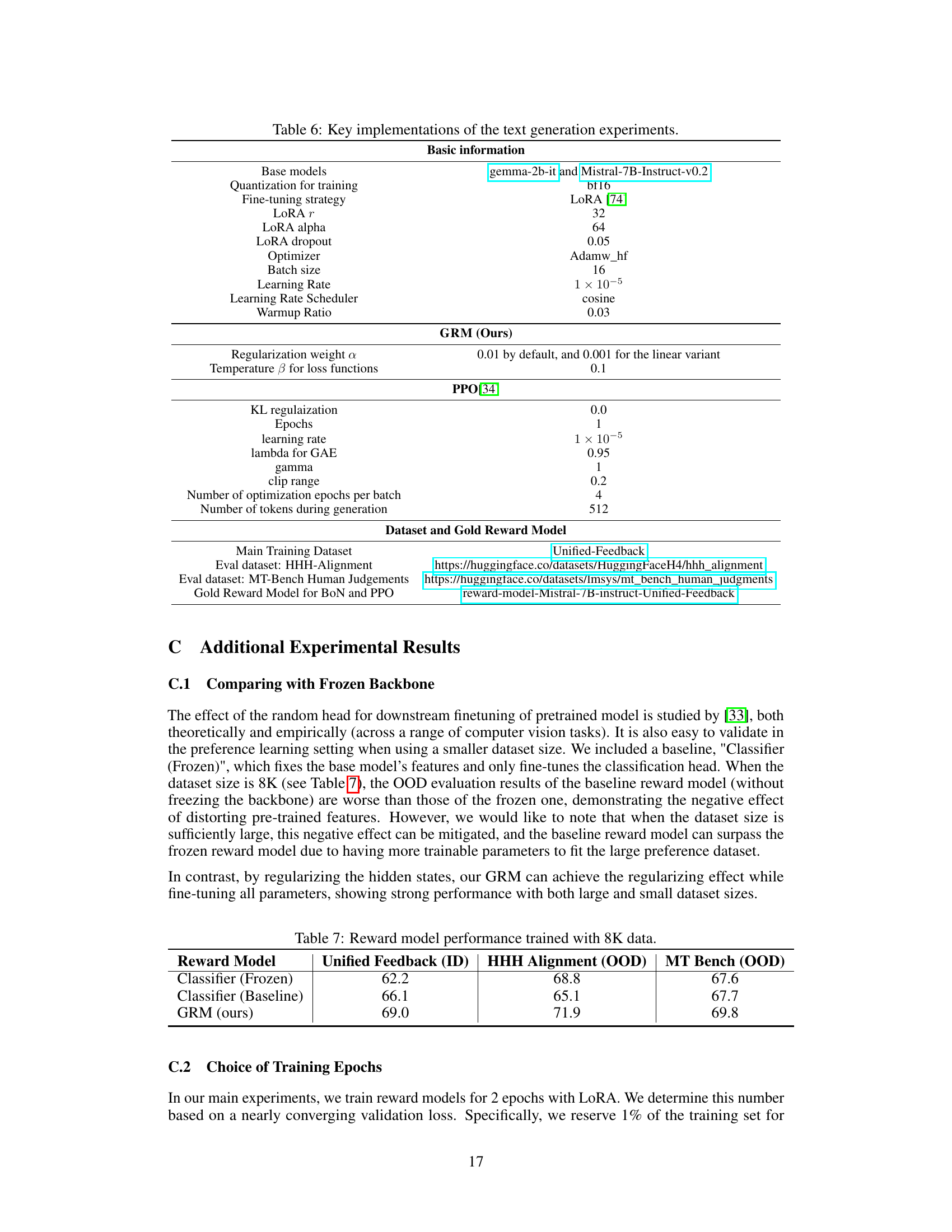

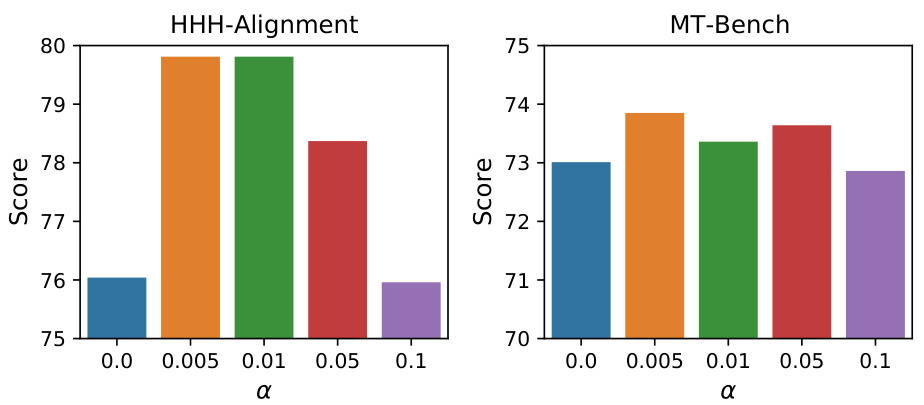

🔼 This figure shows the performance of the Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) with different regularization weights (α) on two out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets: HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench. The x-axis represents the value of α, and the y-axis represents the score achieved on each dataset. The bars show that the optimal value of α lies between 0.005 and 0.05 for both datasets, demonstrating the impact of the regularization weight on the model’s generalization performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparing different values of α for GRM (2B) on scores of HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench.

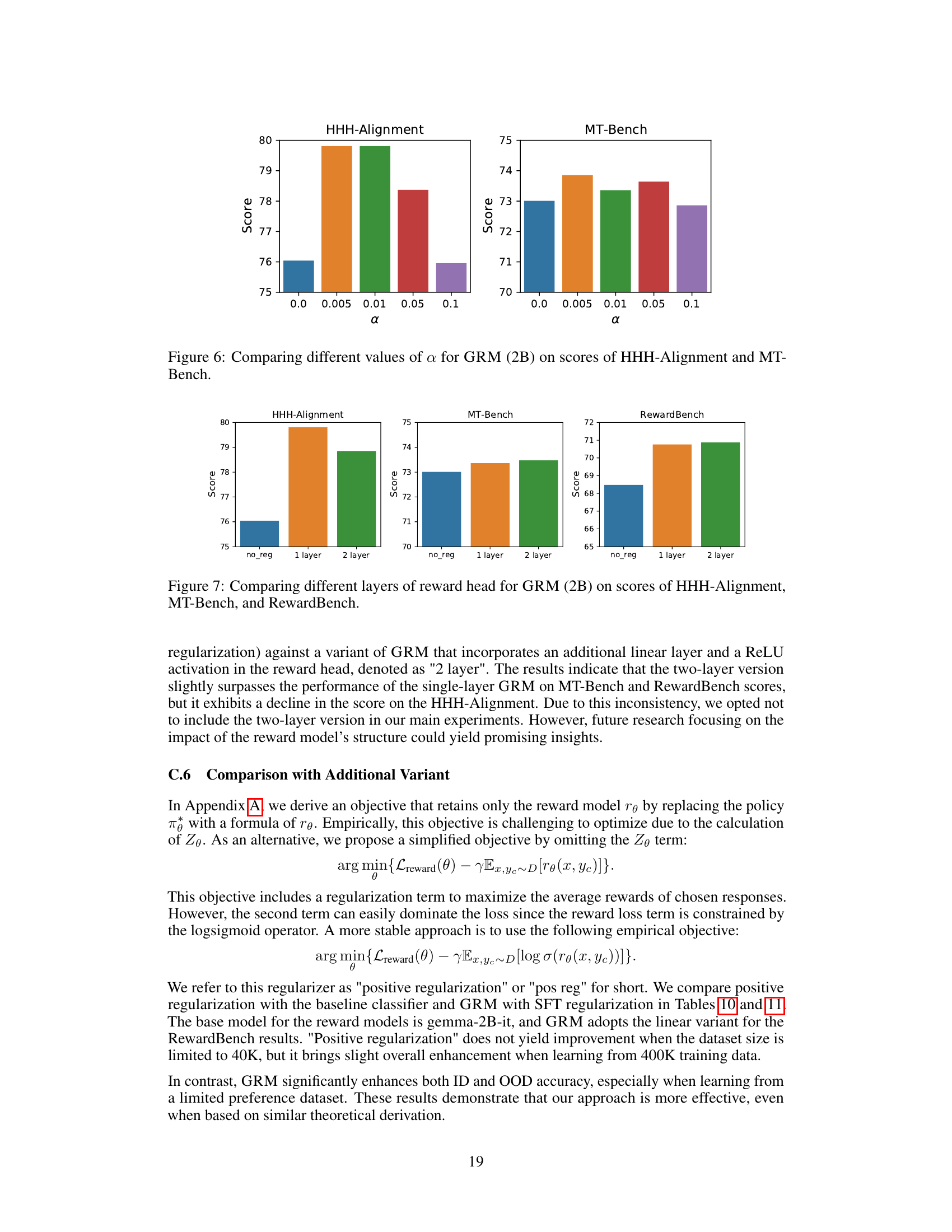

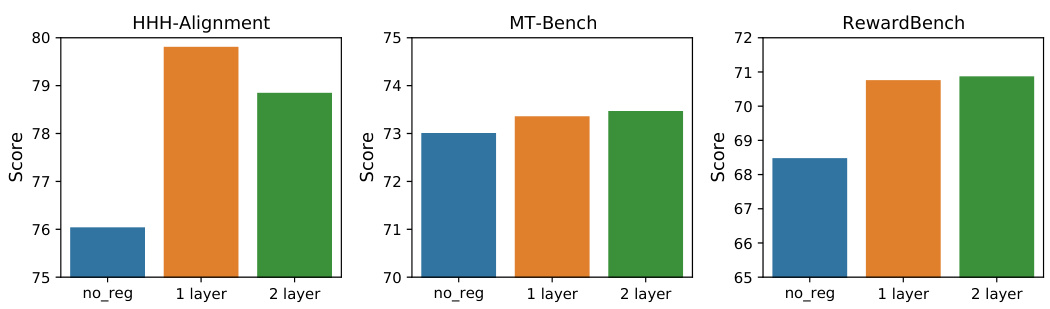

🔼 This figure compares the performance of GRM models with different reward head structures on three benchmark datasets: HHH-Alignment, MT-Bench, and RewardBench. The ’no_reg’ bars represent the baseline GRM without regularization. The ‘1 layer’ bars show the performance of the default GRM with a single layer reward head. The ‘2 layer’ bars depict the results when an additional linear layer and ReLU activation are added to the reward head. The figure helps to understand the effect of the reward head architecture on the model’s generalization ability across various datasets. The results show that adding an extra layer doesn’t universally improve performance, suggesting that the default single-layer architecture provides a good balance.

read the caption

Figure 7: Comparing different layers of reward head for GRM (2B) on scores of HHH-Alignment, MT-Bench, and RewardBench.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of GRM and other reward models in selecting the best response in the Best-of-N (BoN) sampling method. The x-axis represents either the KL divergence or the number of training samples, while the y-axis shows the proxy and gold scores. GRM consistently outperforms the baselines, exhibiting a strong correlation between proxy and gold scores, even when the KL divergence is high.

read the caption

Figure 2: Proxy scores and gold scores of BoN experiments for base models of (a)(b) gemma-2b-it and (c)(d) Mistral-7B-Instruct. Proxy and gold scores are in dashed and solid curves, respectively. Rewards are normalized to start from 0. GRM demonstrates a robust ability to select the best response aligned with the gold rewards as the KL Divergence increases.

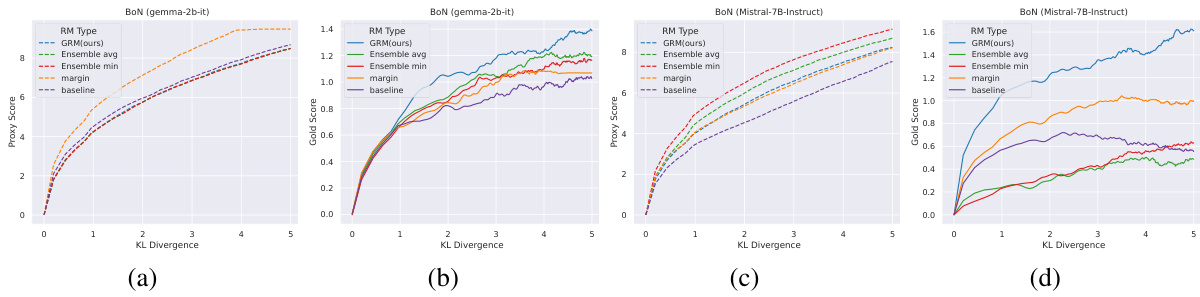

More on tables

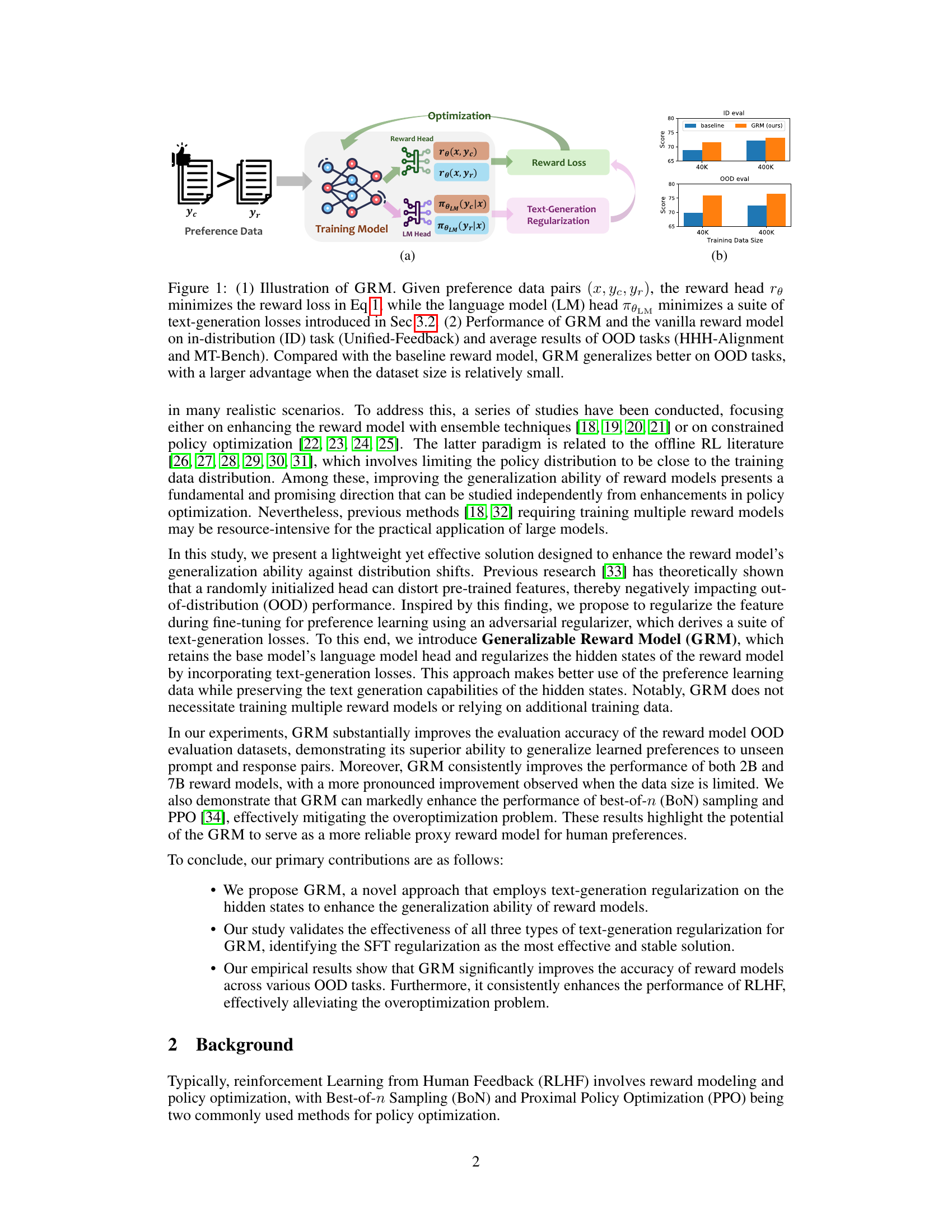

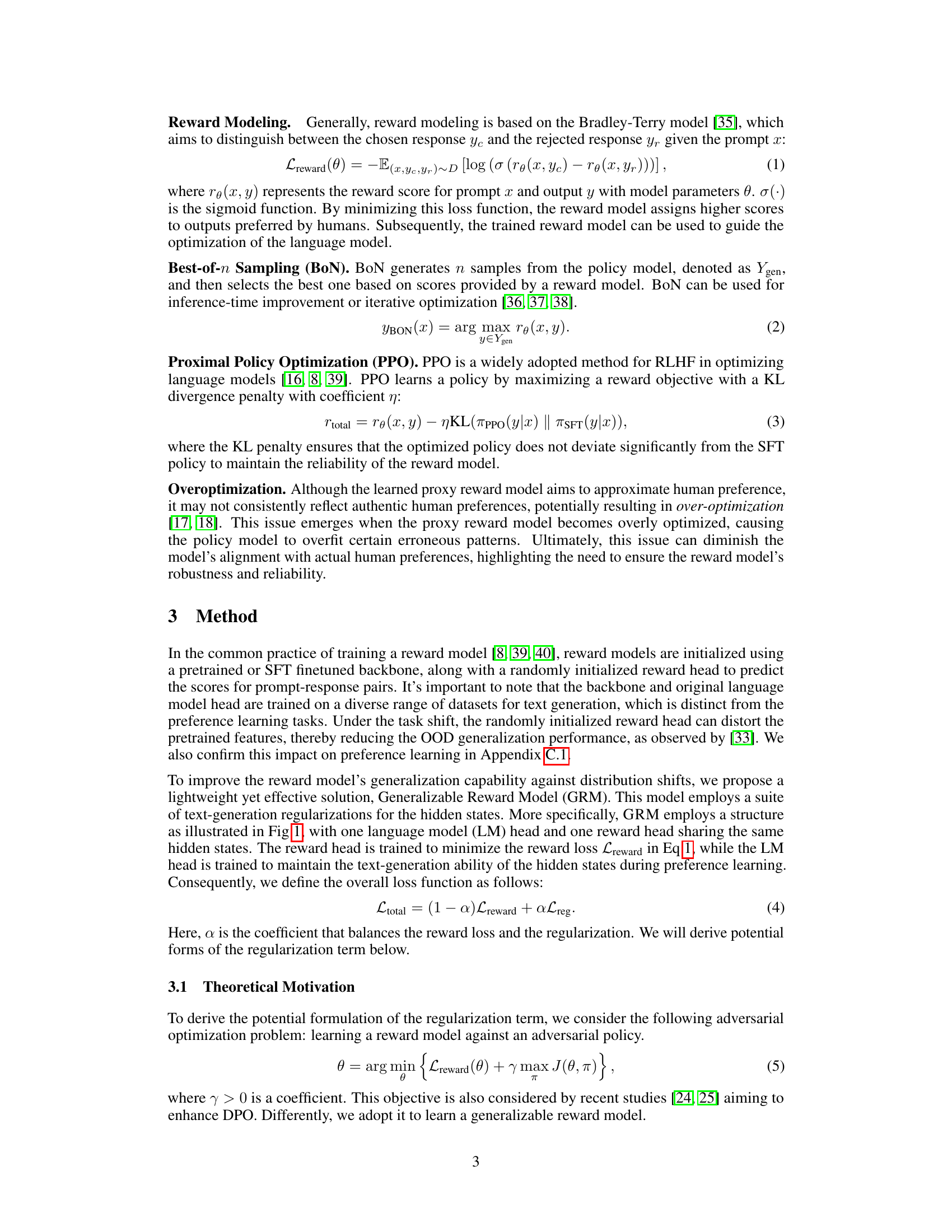

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating various reward models on the RewardBench dataset. The models were trained using 400K samples from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The table shows the average performance across all tasks and the performance broken down by task category: Chat, Chat-Hard, Safety, and Reasoning. The goal is to compare the performance of the proposed Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) against several baseline reward models (Classifier, Classifier+margin, Classifier+label smooth, Classifier+Ensemble) to highlight GRM’s superior generalization ability.

read the caption

Table 3: Results on RewardBench with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback.

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating various reward models on the RewardBench dataset. The models were trained using 400K samples from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The table compares the performance of the proposed Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) against several baseline models (vanilla classifier, classifier with margin, classifier with label smoothing, and classifier with ensemble) across four task categories within RewardBench: chat, chat-hard, safety, and reasoning. The results show the average score for each model across all four task categories, along with the scores for each individual task category. This allows for a detailed comparison of model performance across different types of tasks and different model architectures.

read the caption

Table 3: Results on RewardBench with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback.

🔼 This table presents the results of a full parameter training experiment conducted on the RewardBench dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed GRM model (with 8B parameters) against several other reward models, including GPT-4 variants and state-of-the-art models like FsfairX-LLaMA3-RM-8B and Starling-RM-34B. The comparison is based on the average score across different task categories within RewardBench (Chat, Chat-Hard, Safety, and Reasoning). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of GRM in achieving high performance even on a larger model scale.

read the caption

Table 5: Results of full parameter training on RewardBench.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different reward models on in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks. The models were trained on 400K samples from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The table compares various reward models, including baselines (Frozen Classifier, baseline classifier, classifier + margin, classifier + label smoothing, classifier + ensemble) and the proposed GRM (with three types of regularization: DPO, DPO without reference, and SFT). Performance is measured by the scores achieved on the ID dataset (Unified Feedback) and two OOD datasets (HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench). The best and second-best performing models for each dataset are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table compares the performance of three reward models on an 8K dataset. The models are Classifier (Frozen), which keeps the base model’s parameters fixed; Classifier (Baseline), which is a vanilla reward model; and GRM (ours), which is the proposed generalizable reward model. The evaluation metrics include Unified Feedback (in-distribution), HHH Alignment (out-of-distribution), and MT Bench (out-of-distribution). GRM outperforms the baseline models on all three evaluation metrics, demonstrating its superior generalization capability.

read the caption

Table 7: Reward model performance trained with 8K data.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different reward models on both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks, using a 400K training dataset from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The models’ performance is measured by their scores on the ID dataset and two OOD datasets (HHH-Alignment and MT-Bench). The best-performing model in each task is highlighted in bold, and the second-best is underlined, allowing for a clear comparison of the models’ generalization capabilities. The table shows that the proposed Generalizable Reward Model (GRM) consistently outperforms various baseline models across both in-distribution and out-of-distribution tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different reward models on both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks. The models were trained on 400K samples from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The performance metrics are shown for three tasks: Unified Feedback (ID), HHH-Alignment (OOD), and MT-Bench (OOD). The best performing model for each task is highlighted in bold, with the second-best underlined. This allows for easy identification of the best-performing models and comparison of the effectiveness of different reward model training techniques.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of various reward models on in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks. The models were trained on 400K samples from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The table shows the accuracy scores for each model across three tasks: Unified Feedback (ID), HHH-Alignment (OOD), and MT-Bench (OOD). The best and second-best performing models are highlighted for each task.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table presents the win rate, tie rate, and loss rate of language models after training with proximal policy optimization (PPO). The models are trained using two different base reward models: Gemma 2B it and Mistral 7B Instruct. The ‘win rate’ indicates the percentage of times the model trained with GRM outperformed the model trained with the vanilla reward model. Similarly, the ’tie rate’ shows the percentage of times both models performed equally, while the ’loss rate’ indicates when the model trained with the vanilla reward model outperformed the one trained with GRM. This data helps evaluate the effectiveness of the GRM in improving the performance of models undergoing PPO training.

read the caption

Table 14: Win rate of models after PPO training with GRM against those with the vanilla reward model.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different reward models on both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks, using the Unified-Feedback dataset for training. The results show the accuracy scores achieved by various models on three evaluation datasets: Unified Feedback (ID), HHH-Alignment (OOD), and MT-Bench (OOD). The best performing model for each task is highlighted in bold, while the second-best is underlined. The table aims to demonstrate the generalization capability and robustness of the proposed GRM (Generalizable Reward Model) compared to several baseline models, such as the vanilla classifier and different regularization techniques.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table presents the results of in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) evaluations of different reward models using 400,000 data points from the Unified-Feedback dataset. The models are evaluated on three tasks: Unified Feedback (ID), HHH-Alignment (OOD), and MT-Bench (OOD). The best performing model for each task is highlighted in bold, and the second-best is underlined. This allows comparison of different methods across in-distribution and out-of-distribution settings.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

🔼 This table presents the results of in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) evaluations of different reward models using the gemma-2B-it base model. It compares the performance of the proposed GRM method against several baselines across three datasets: Unified-Feedback (ID), HHH-Alignment (OOD), and MT-Bench (OOD). The table highlights the superior generalization ability of GRM, especially when the training dataset size is limited. The best performance on each dataset (ID and OOD) is shown in bold, with the second-best result underlined.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on ID and OOD evaluation with 400K training data from Unified-Feedback. The best performance in each task is in bold and the second best one is underlined.

Full paper#