↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Cross-domain few-shot learning (CFC) aims to classify images from unseen domains using limited labeled data. Current CFC methods adapt a single transformation for both prototype (class representation) and image embeddings. This paper reveals that this approach overlooks a significant gap between prototype and image representations, hindering optimal learning.

The researchers introduce CoPA, a novel method that addresses this issue. CoPA adapts different transformations for prototypes and images, similar to the successful CLIP model. Extensive experiments demonstrate CoPA’s superior performance, achieving state-of-the-art results while efficiently learning better representation clusters. CoPA also reveals that a larger gap between prototypes and image representations improves generalization, offering valuable insights for future CFC research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in few-shot learning and cross-domain adaptation. It highlights a critical gap in existing methods and proposes a novel solution (CoPA) that significantly improves performance. The findings are broadly applicable and offer valuable insights for future research in representation learning and model adaptation.

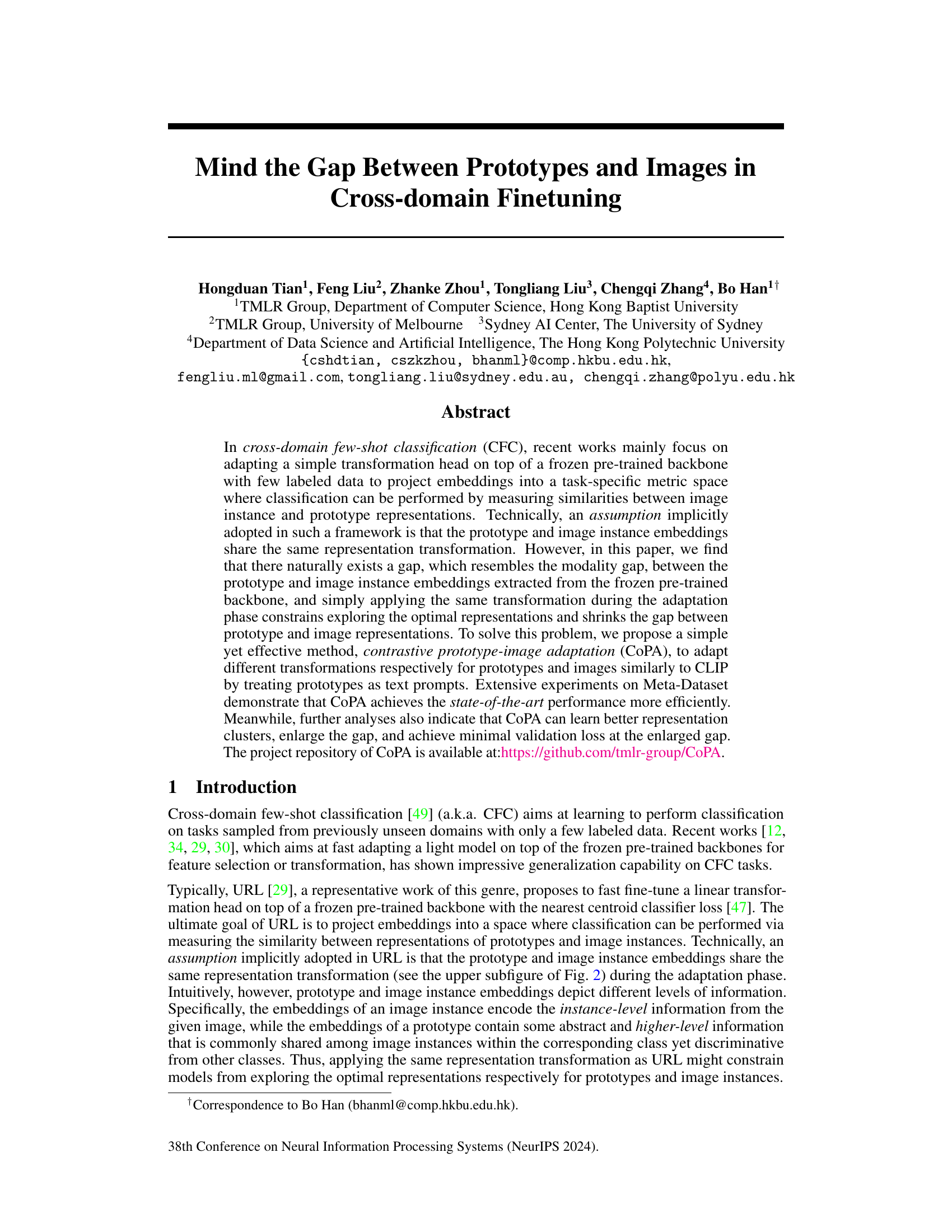

Visual Insights#

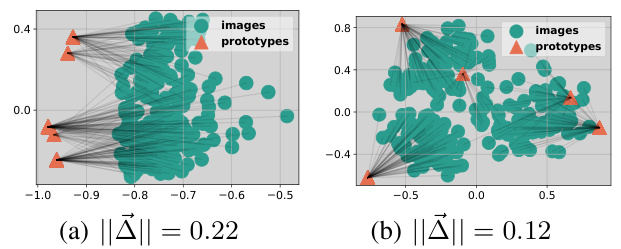

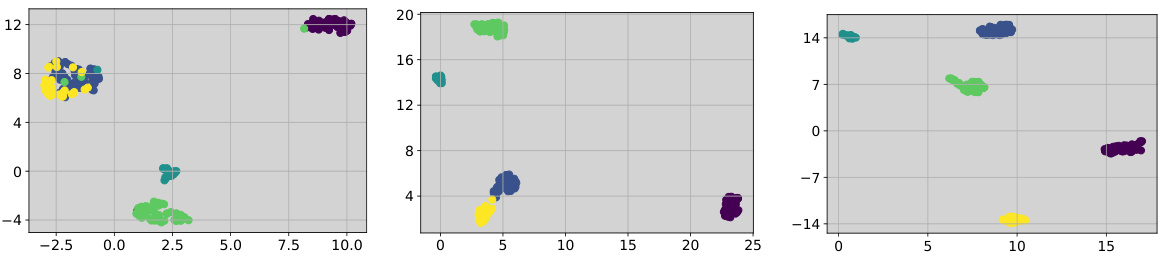

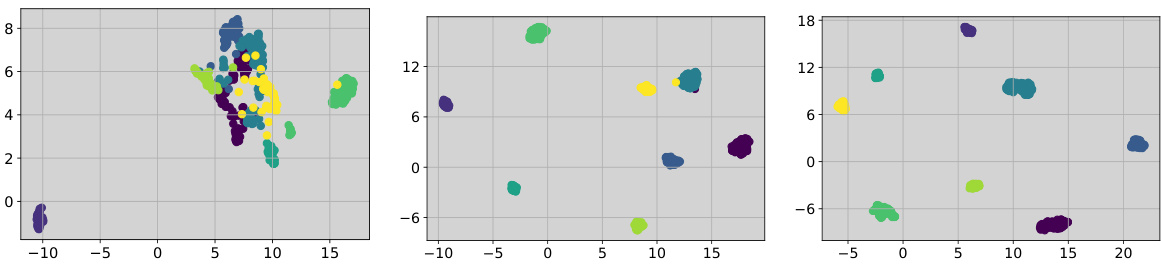

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to visualize the gap between prototype and image embeddings. The left panel (a) shows the natural gap between the embeddings extracted from a frozen pre-trained backbone. Applying the same transformation to both prototype and image instance embeddings reduces this gap, as shown in the right panel (b). The gap’s existence and the transformation’s effect on it are key observations in the paper.

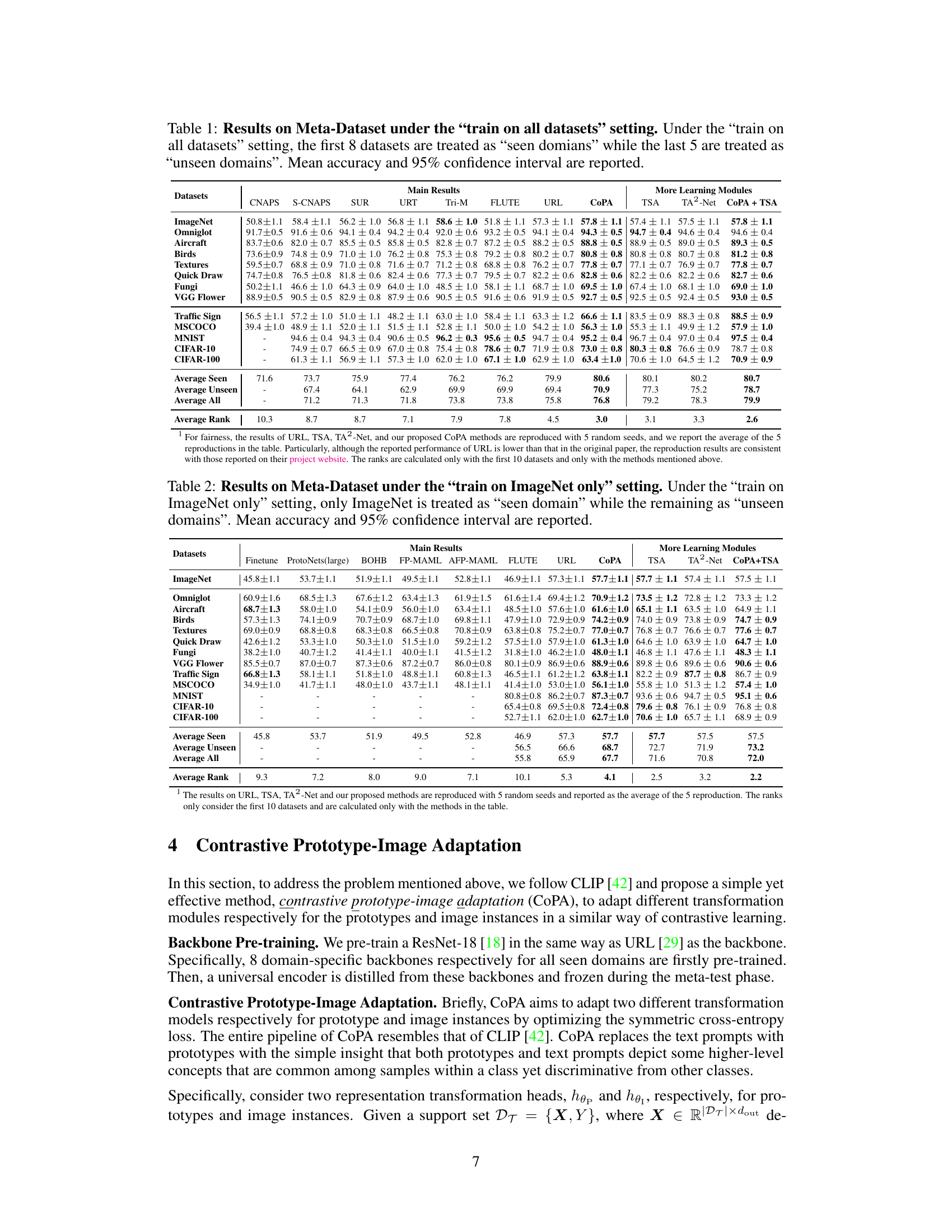

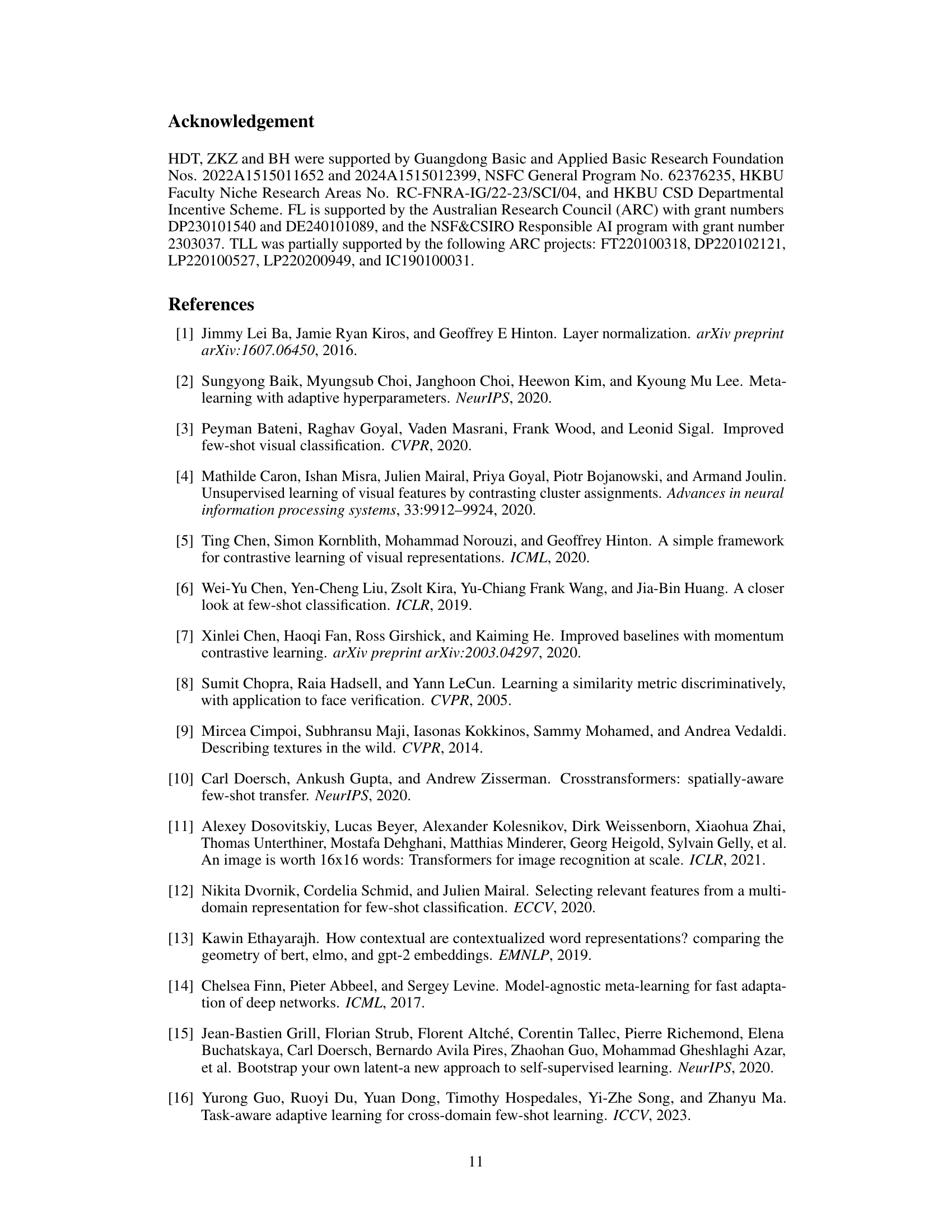

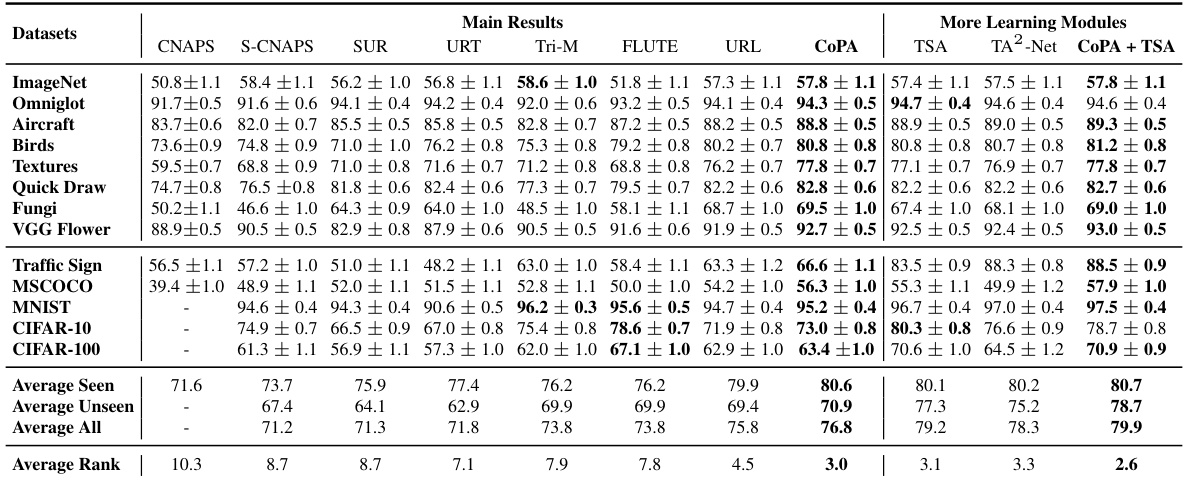

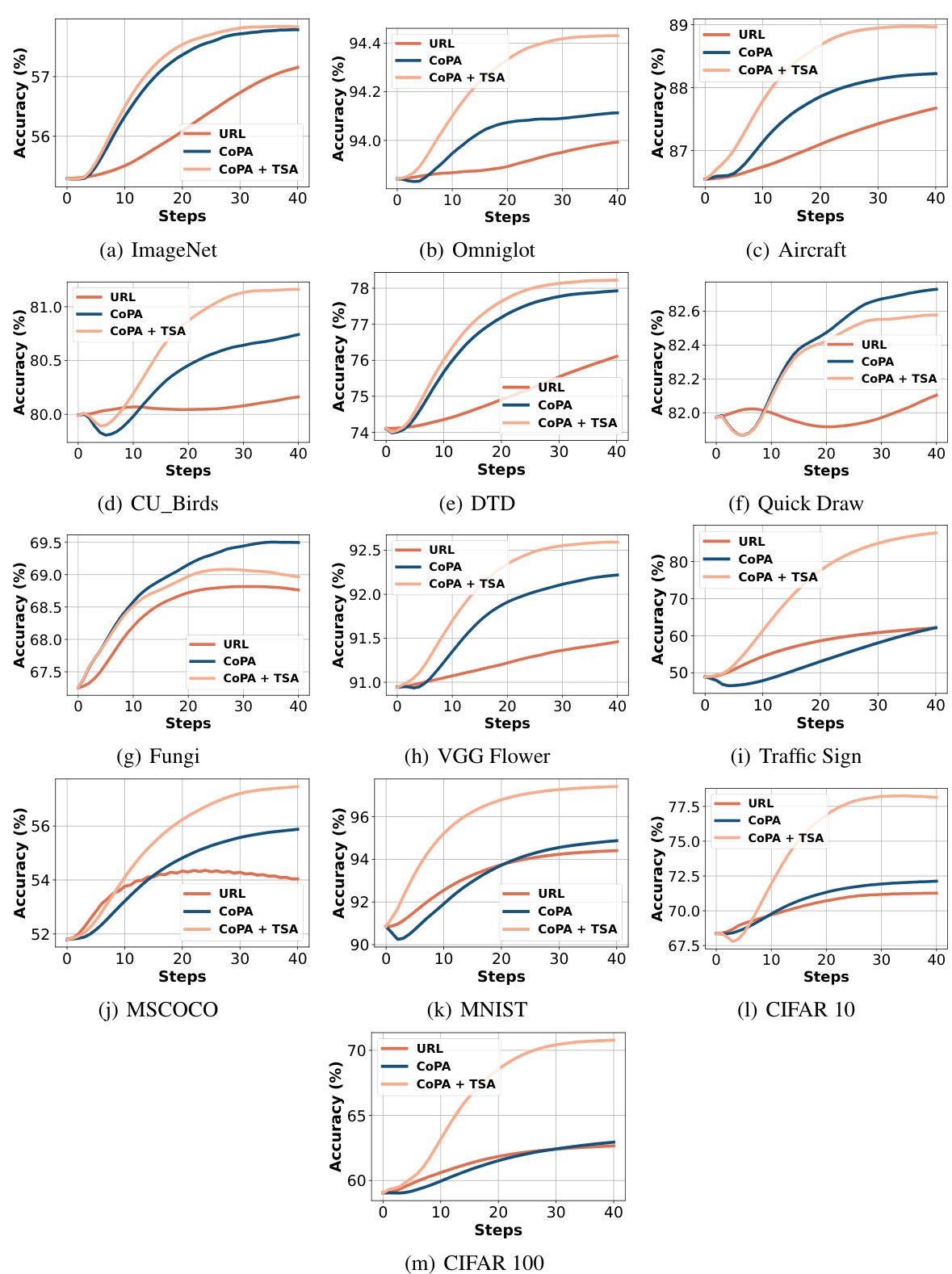

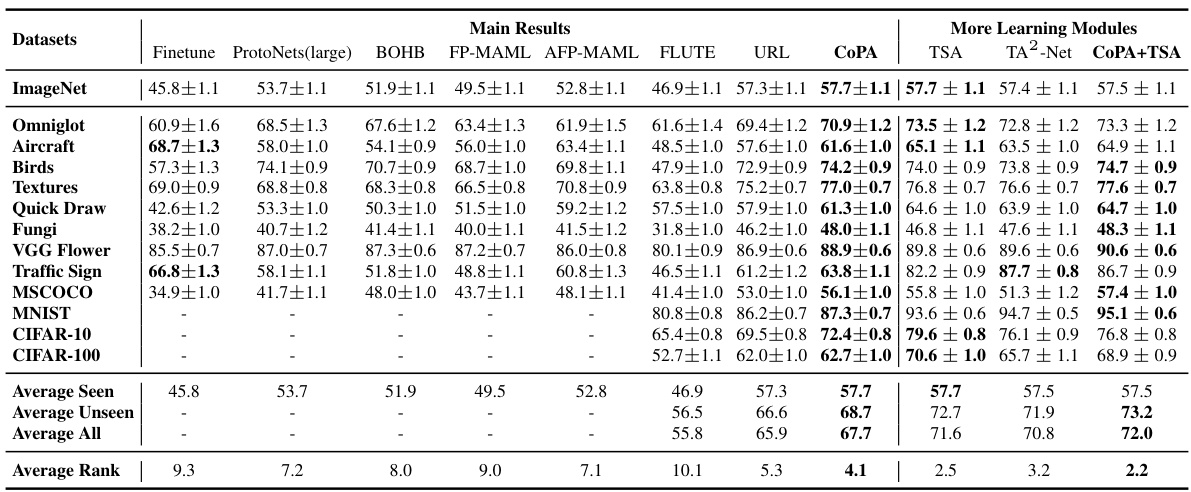

This table presents the results of the proposed CoPA method and other state-of-the-art methods on the Meta-Dataset benchmark under the ’train on all datasets’ setting. It shows the mean accuracy and 95% confidence intervals for each dataset, categorized into seen and unseen domains. The average accuracy across seen and unseen domains and average ranks of the models are also provided. This provides a comprehensive performance comparison of various few-shot learning models in a cross-domain setting.

In-depth insights#

Prototype-Image Gap#

The concept of “Prototype-Image Gap” highlights a crucial observation in cross-domain few-shot learning: prototypes and image instances, even when derived from the same backbone network, possess distinct representational characteristics. Prototypes, representing class-level abstractions, capture higher-level semantic information, while image instances encode detailed, instance-specific features. This gap is akin to a “modality gap”, analogous to the difference between text and image representations in multi-modal models. Simply applying the same transformation to both prototypes and images during adaptation restricts the model’s ability to learn optimal representations for each, hindering performance. The existence and impact of this gap underscore the need for specialized adaptation strategies, such as separately transforming prototypes and images. Approaches that preserve or even enlarge this gap, like contrastive learning, prove beneficial for better generalization. Failing to account for this gap can limit model’s capacity to leverage the distinct information embedded within prototypes and images, ultimately impacting few-shot classification accuracy.

CoPA Adaptation#

CoPA Adaptation presents a novel approach to cross-domain few-shot classification (CFC) by addressing the inherent disparity between prototype and image instance embeddings. The core innovation lies in decoupling the adaptation process for prototypes and images, employing distinct transformation heads instead of a shared one as in previous methods. This allows the model to learn more effective representations by preserving the discriminative information present in gradients. Treating prototypes as text prompts, similar to CLIP’s approach, further enhances this effect. By learning separate transformations, CoPA leverages a contrastive loss to enlarge the gap between prototypes and images, improving representation clustering and ultimately enhancing generalization performance. The results show that CoPA achieves state-of-the-art results more efficiently while learning more compact representation clusters. This technique is particularly effective in handling unseen domains and minimal validation loss at an enlarged gap.

Meta-Dataset Results#

The Meta-Dataset Results section of a research paper would typically present the performance of different few-shot learning models on the Meta-Dataset benchmark. A thoughtful analysis would go beyond simply reporting accuracy numbers. It should discuss the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model across different datasets within Meta-Dataset, highlighting whether any model consistently outperforms others or shows particular strengths on specific visual domains (e.g., images of animals versus handwritten characters). The analysis should also address statistical significance, demonstrating if observed performance differences are meaningful, and consider potential biases or limitations of the Meta-Dataset itself, as this can impact the generalizability of the results. Crucially, a strong analysis would correlate the results with the core methodology of the paper, explaining how any observed successes or failures relate to the proposed approach, and exploring the reasons for any unexpected outcomes. Finally, a discussion of future research directions based on these findings would provide valuable context.

Gap Generalization#

The concept of “Gap Generalization” in the context of cross-domain few-shot learning (CFC) is intriguing. It suggests that the performance of a model is not solely determined by minimizing the distance between prototypes and images, but also by the magnitude of the gap between these representations. A larger gap, which can resemble a “modality gap” seen in multi-modal learning, might indicate that the model has learned more discriminative features. Simply shrinking this gap by applying the same transformation to both prototypes and images may hinder the model’s ability to generalize effectively to unseen domains. Instead, the optimal strategy might involve learning different transformations for prototypes (higher-level abstractions) and images (instance-level details), potentially preserving the gap and resulting in improved generalization. This is supported by the observation that models which preserve or even enlarge this gap tend to show better generalization performance and compact representation clusters. Further research is needed to fully explore the impact of different transformation strategies on the gap and how the size of the gap relates to overall model performance.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending CoPA to handle even more complex visual tasks beyond image classification, such as object detection or segmentation, is crucial. Investigating the effect of different backbone architectures and pre-training strategies on CoPA’s performance is warranted. A deeper theoretical analysis of the relationship between the prototype-image gap and generalization capability would yield valuable insights. Furthermore, empirical evaluations on a wider range of datasets with diverse characteristics would strengthen the findings. Finally, exploring more sophisticated methods for prototype selection and adaptation could lead to significant improvements. These avenues offer exciting possibilities for advancing the field of cross-domain few-shot learning.

More visual insights#

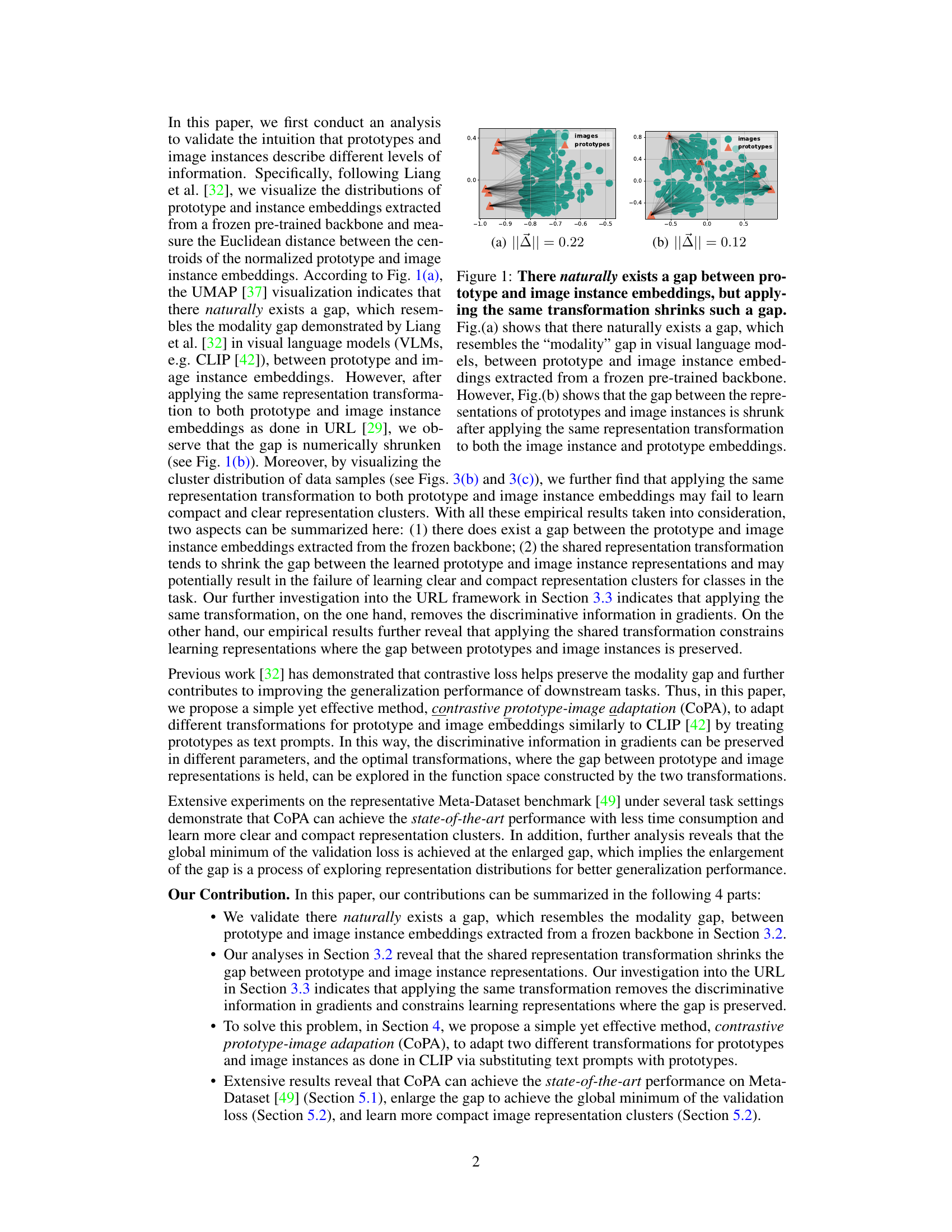

More on figures

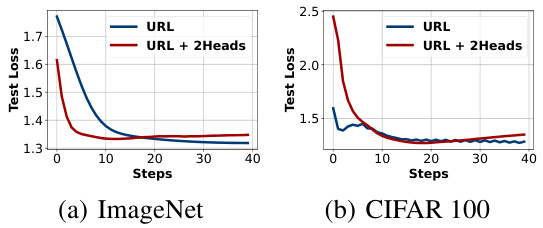

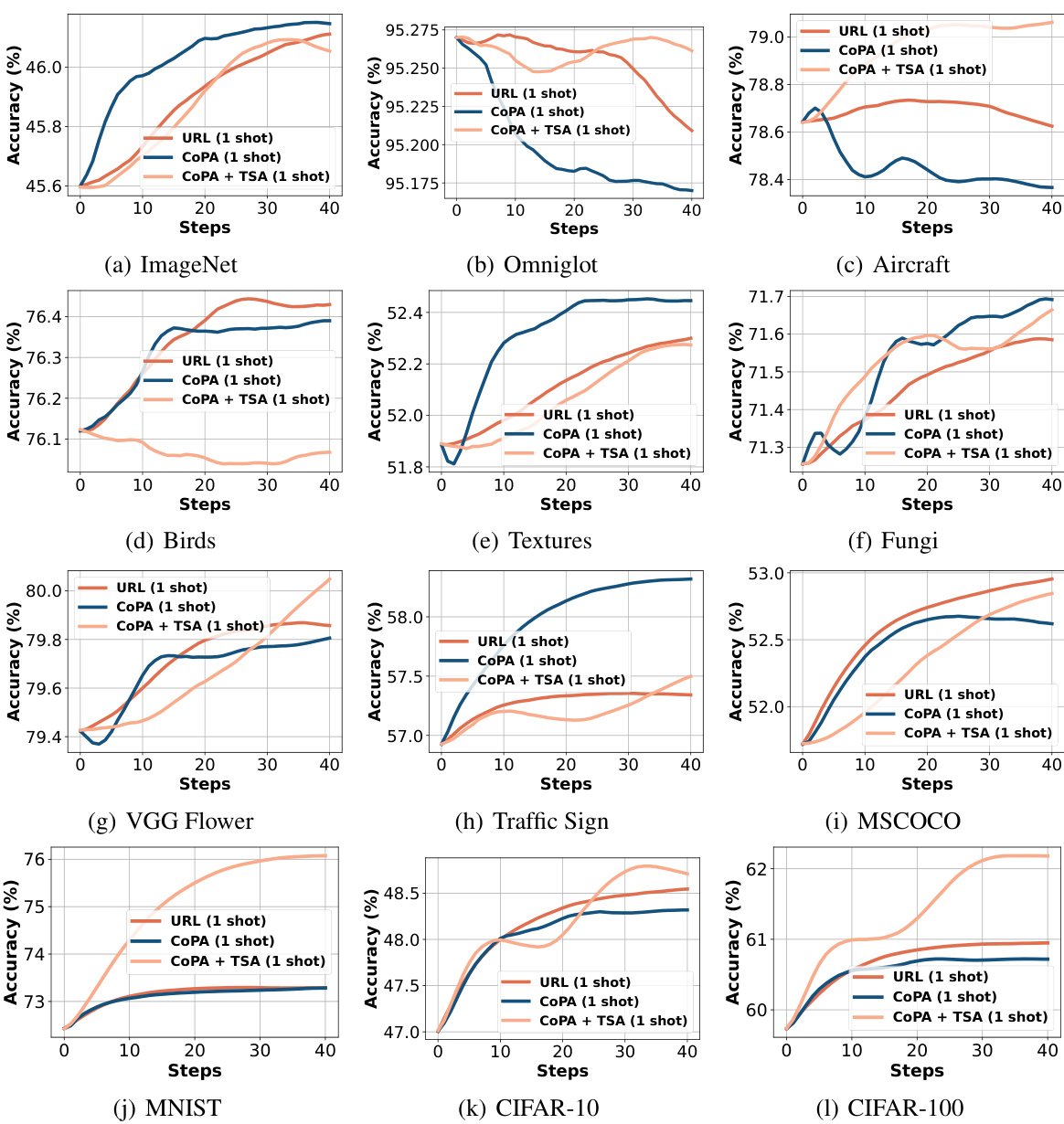

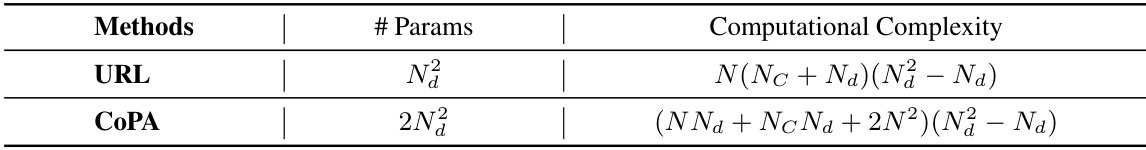

This figure compares the architectures of URL and CoPA. URL uses a single transformation head applied to both prototype and image embeddings. CoPA, inspired by CLIP, uses separate transformation heads for prototypes and image embeddings to address the limitations of applying a single transformation. This allows CoPA to learn distinct representations that better capture the differences between prototypes (high-level class information) and image instances (low-level instance information).

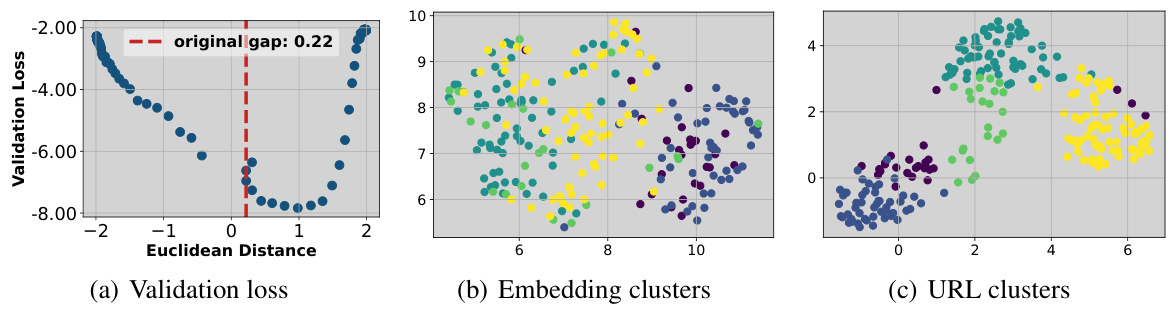

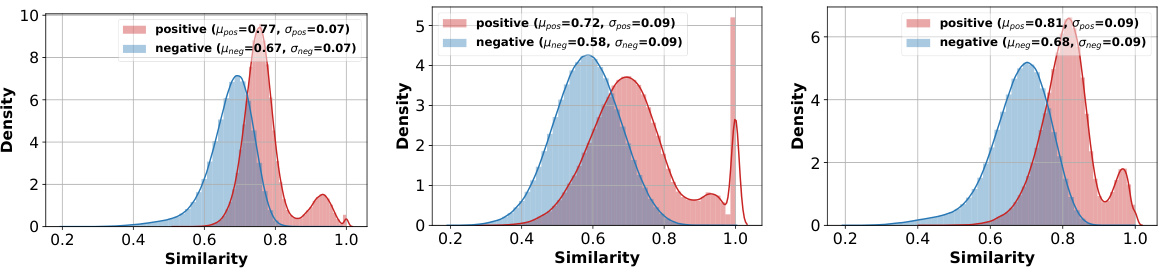

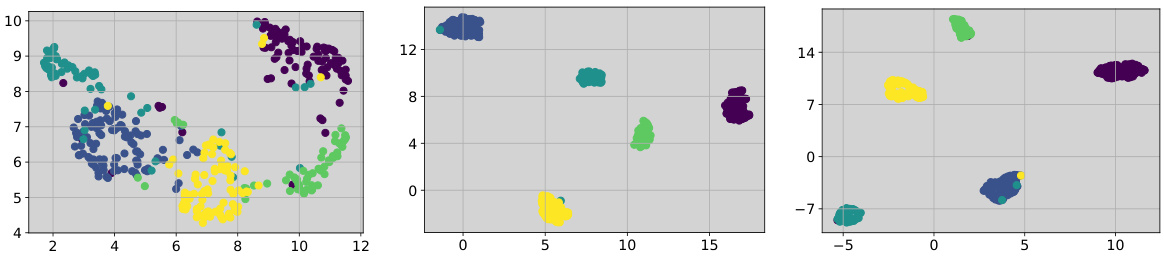

This figure shows that enlarging the gap between prototype and image embeddings leads to a lower validation loss, indicating better generalization. It also demonstrates that using a shared transformation for both prototypes and images hinders the learning of compact and well-clustered image representations.

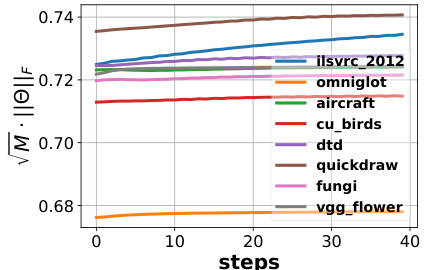

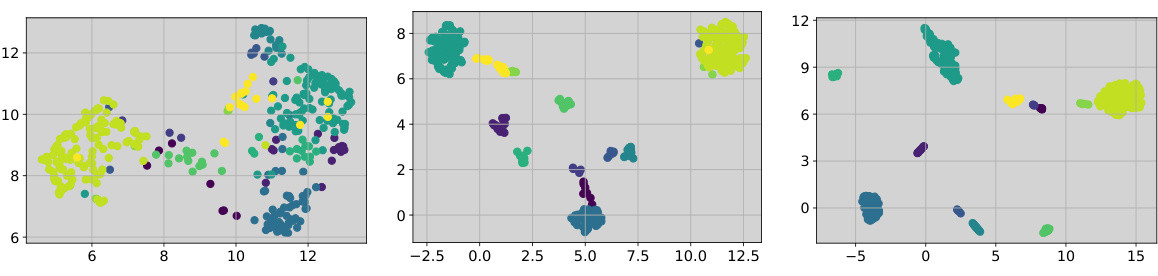

The figure shows the change of the scale of the upper bound of URL representation gaps during the adaptation process for eight different datasets. The y-axis represents the scale (√M ||Θ||F), which is a measure used in Theorem 3.2 to bound the gap between prototype and image representations. The x-axis represents the number of steps in the adaptation. The graph shows that for all datasets, the scale remains below 1, indicating that the shared transformation used in URL shrinks the gap between prototypes and image instances.

This figure shows three plots. The first plot (a) is a UMAP visualization of prototype and image embeddings showing that the gap between them is enlarged after applying CoPA. The second plot (b) visualizes the image instance representation clusters obtained with CoPA and shows that the clusters are more compact than those learned by URL. The last plot (c) shows the validation loss curve with respect to the Euclidean distance, indicating that CoPA achieves the global minimum at an enlarged gap.

This figure shows that enlarging the gap between prototype and image embeddings leads to a lower validation loss and better-formed clusters. The shared transformation used in previous methods shrinks this gap and produces poor clusters.

The figure shows the results of an experiment designed to visualize the gap between prototype and image instance embeddings. Figure 1(a) demonstrates that a gap exists between prototype and image embeddings when extracted directly from a pre-trained backbone. Figure 1(b) shows that applying the same transformation to both prototype and image embeddings reduces this gap. This reduction in the gap suggests that different transformations are needed for prototypes and image instances to maintain the distinction in their representation.

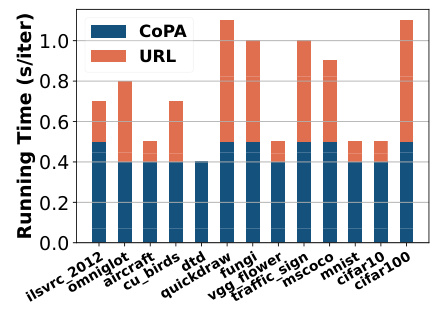

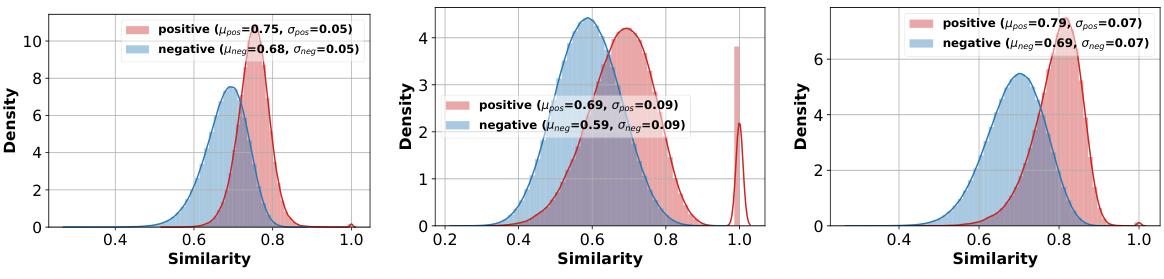

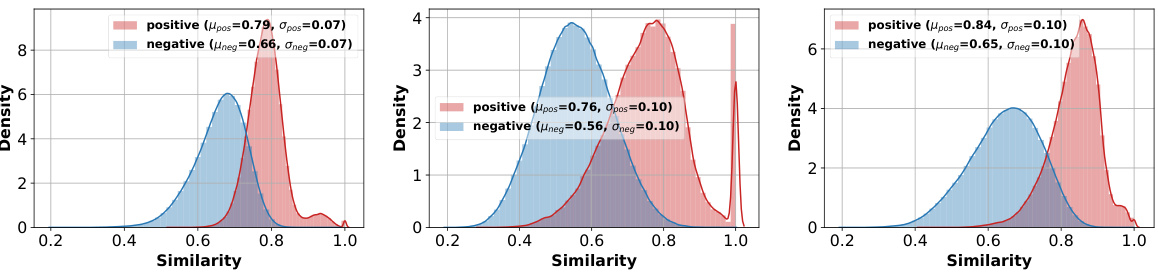

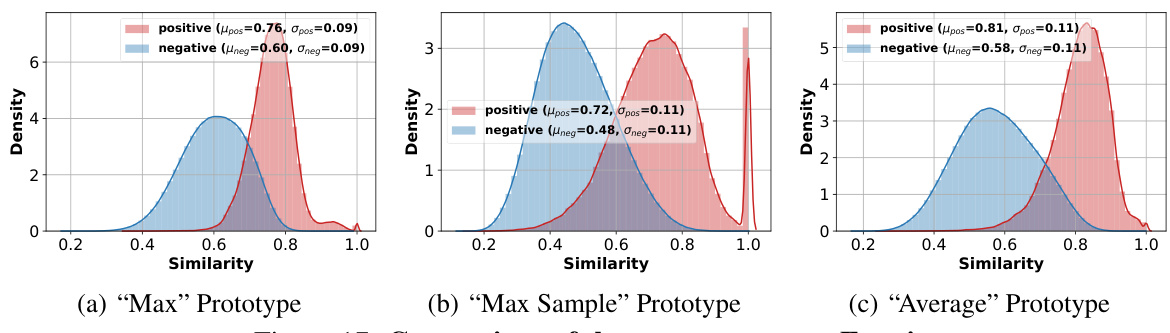

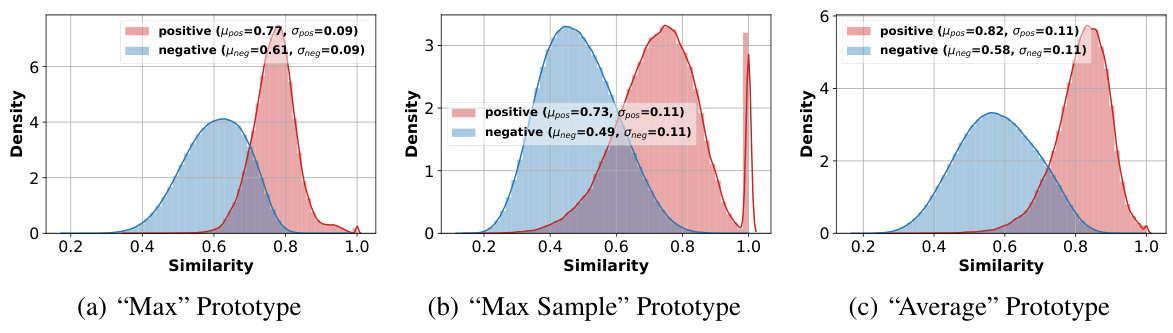

This figure compares three different prototype selection methods: Max, Max Sample, and Average. It shows the average accuracy of URL (a representative adaptation strategy from prior work) using each prototype on the ImageNet dataset. Subplots (b), (c), and (d) display the distributions of positive and negative similarities (similarity of samples to their own class prototype versus similarity to other class prototypes) for each prototype type, demonstrating the differences in their representational properties and how these properties relate to classification performance.

This figure shows an analysis of the gap between prototype and image embeddings. (a) shows that there is a gap between the embeddings of prototypes and image instances extracted from a frozen pre-trained backbone. This gap is similar to the modality gap observed in visual language models. (b) shows that applying the same transformation to both prototype and image embeddings shrinks this gap. This suggests that using separate transformations for prototypes and images might be beneficial.

This figure shows the validation loss landscape with respect to the changes in the modality gap between prototype and image embeddings. It demonstrates that the global minimum validation loss is achieved when the gap is enlarged, indicating that a larger gap is beneficial. The figure also includes visualizations of embedding clusters, showing that the shared representation transformation fails to learn compact instance representation clusters compared to the proposed method.

The figure shows the comparison of running time per iteration between the URL and CoPA methods on 13 datasets. CoPA is generally faster than URL, with the largest differences observed on datasets like fungi and ilsvrc_2012.

The figure shows the results of an experiment comparing three different prototype selection methods (‘Max’, ‘Max Sample’, and ‘Average’) for few-shot image classification using the URL baseline. The comparison includes the average accuracy achieved by each prototype selection method on the ImageNet dataset and the distribution of positive (similarity between the prototype and samples of the same class) and negative (similarity between the prototype and samples from different classes) similarities. This helps in determining which prototype selection method produces the best prototypes for few-shot classification.

This figure shows that the global minimum validation loss is achieved when the gap between prototype and image instance embeddings is enlarged. The shared representation transformation fails to learn compact instance representation clusters because it shrinks the gap between prototypes and images.

This figure visualizes the distributions of prototype and image instance embeddings. Figure 1(a) shows a clear gap between prototype and image embeddings extracted from a pre-trained backbone, similar to the modality gap observed in visual language models. Figure 1(b) demonstrates that applying the same transformation to both prototype and image embeddings shrinks this gap, highlighting the difference in information captured by prototype and image embeddings.

The figure shows that enlarging the gap between prototype and image embeddings leads to a lower validation loss, suggesting that the shared transformation used in previous methods constrains learning and prevents the formation of well-defined clusters. The optimal performance is obtained with an enlarged gap between the embeddings.

This figure compares three different prototype selection methods: Max, Max Sample, and Average. It shows the average accuracy of the URL method using each prototype type on the ImageNet dataset. Subplots (b), (c), and (d) display the distributions of positive and negative similarities for each prototype type, illustrating their effectiveness in distinguishing between samples within and outside of their assigned classes.

This figure analyzes three different prototype selection methods for few-shot classification: Max, Max Sample, and Average. It shows the average accuracy of the URL method using each prototype type on the ImageNet dataset. Additionally, it presents the distributions of positive (similarity between a sample and its own class prototype) and negative (similarity between a sample and prototypes from other classes) similarities for each prototype type, providing insights into their discriminative power.

This figure shows that enlarging the gap between prototype and image embeddings leads to a lower validation loss. It also shows that using the same transformation for both prototypes and images results in poorly formed clusters, while separate transformations lead to better-formed clusters.

This figure compares three different prototype selection methods for few-shot classification on ImageNet: Max, Max Sample, and Average. It shows the average accuracy of the URL method using each prototype type, along with the distributions of positive and negative similarities for each. Positive similarity refers to the similarity between a sample and its own class prototype, while negative similarity measures similarity with prototypes from other classes. The results indicate that the ‘Average’ prototype generally outperforms the others in terms of accuracy and similarity distributions, suggesting it is the most effective prototype type in this context.

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to visualize the gap between prototype and image instance embeddings. Panel (a) shows the natural gap between prototypes and image embeddings extracted from a pre-trained backbone using UMAP visualization. Panel (b) demonstrates that applying the same transformation to both prototype and image embeddings reduces this gap. This observation highlights a key problem addressed in the paper, specifically that assuming prototypes and image embeddings share the same transformation constrains optimal representation learning and limits the effectiveness of cross-domain few-shot classification.

The figure shows an analysis of the effect of the gap between prototype and image embeddings on validation loss and representation cluster quality. The leftmost subplot shows that validation loss is minimized when the gap is enlarged. The two rightmost subplots compare representation clusters generated with and without a shared transformation, revealing the shared transformation impedes the formation of compact clusters.

This figure shows the validation loss landscape as a function of the gap between prototype and image embeddings. The global minimum loss is obtained when this gap is enlarged, illustrating that the shared transformation used in previous methods is suboptimal. The figure also includes visualizations showing the improved clustering of image representations when this gap is increased.

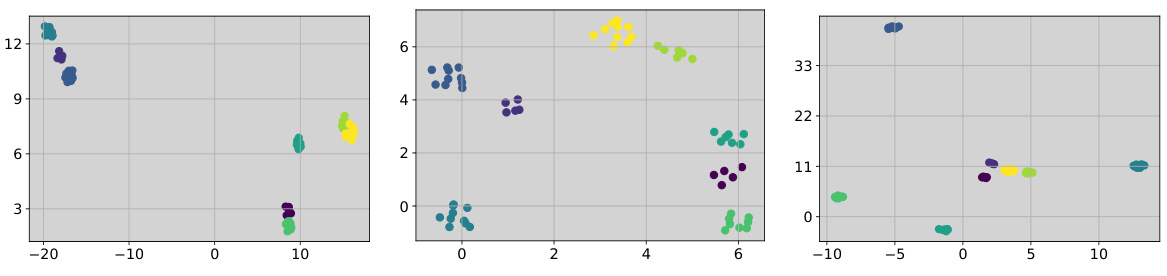

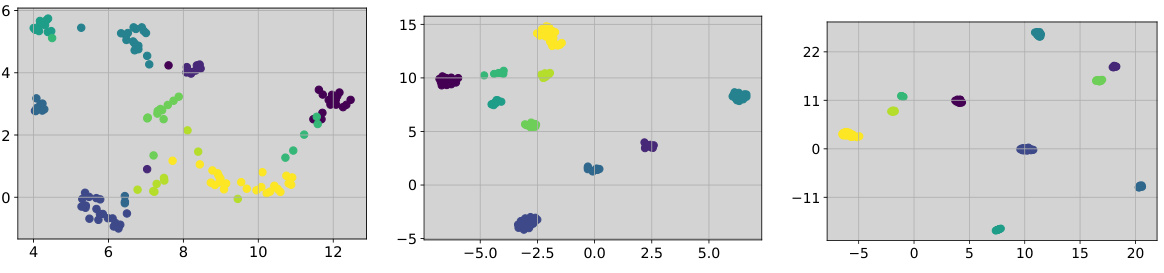

This figure visualizes the embedding and representation clusters of the Omniglot dataset using three different methods: (a) Extracted embeddings, (b) URL representation, and (c) CoPA representation. It demonstrates that CoPA learns more compact and clearly separated representation clusters compared to the other methods. The visualization helps understand how different representation learning strategies impact the quality of cluster formations, which is critical for few-shot classification.

The figure shows three subfigures. (a) shows the validation loss landscape with respect to the changes in the modality gap between prototype and image instance embeddings. (b) shows the embedding clusters of prototype and image instances from the frozen backbone. (c) shows the embedding clusters of prototype and image instances with the shared transformation. The global minimum validation loss occurs when the modality gap is enlarged. The shared transformation fails to generate compact representation clusters.

This figure shows the relationship between the validation loss and the distance between prototype and image embeddings. The global minimum validation loss is not at the original distance. When the distance between the prototypes and image embeddings is enlarged, the validation loss decreases. Furthermore, the figure shows the effect of a shared representation transformation on the clustering of embeddings. A shared transformation results in less well-defined clusters compared to when separate transformations are used for prototypes and images.

This figure shows that enlarging the gap between prototype and image embeddings leads to a lower validation loss and better clustering of image representations. The shared transformation used in previous methods fails to achieve this optimal gap and representation clustering.

The figure shows that the global minimum validation loss is achieved when the gap between prototype and image instance embeddings is enlarged. The shared representation transformation fails to learn compact instance representation clusters. Applying the same transformation shrinks the gap and hinders the learning of clear clusters, whereas enlarging the gap improves the model’s generalization performance.

This figure shows that there is a gap between prototype and image embeddings before applying a transformation. However, when the same transformation is applied to both, the gap shrinks. This supports the paper’s claim that applying separate transformations for prototypes and images is beneficial.

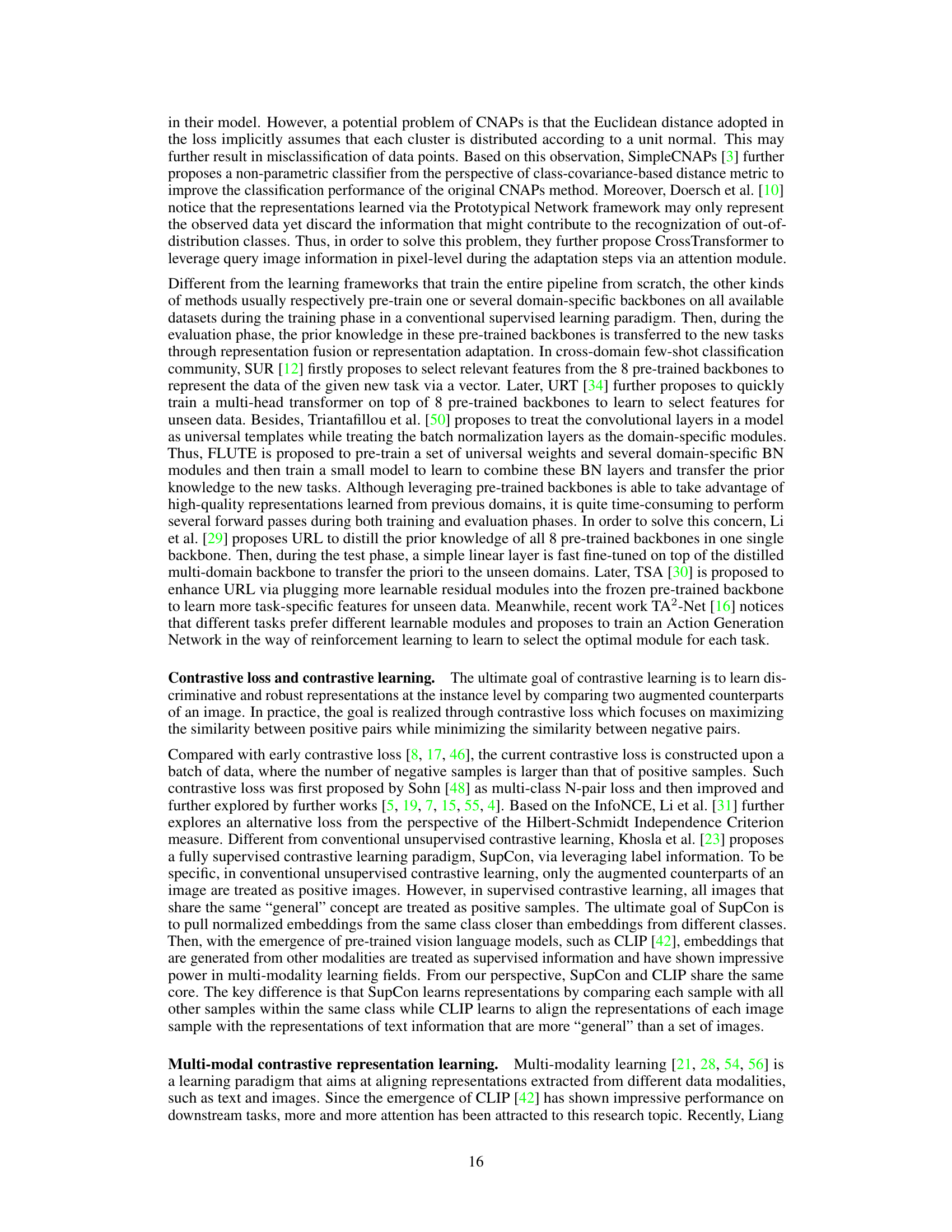

More on tables

This table presents the results of various few-shot learning methods on the Meta-Dataset benchmark, using the ’train on all datasets’ setting. The first 8 datasets are considered ‘seen domains,’ while the remaining 5 are ‘unseen domains.’ The table shows the mean accuracy and 95% confidence interval for each method across all datasets. It allows for a comparison of different methods on both seen and unseen data, revealing their generalization capabilities to new datasets.

This table presents the average gap between prototype and image instance embeddings/representations across 8 datasets in the Meta-Dataset benchmark. The gap is calculated as the Euclidean distance between the centroids of normalized prototype and image instance embeddings. Three gap measurements are shown: the original gap from the pre-trained backbone (||Aembed||), the gap after applying the same transformation as in the URL method (||AURL||), and the gap after applying the CoPA method (||ACOPA||). The table demonstrates that CoPA enlarges the gap, while URL shrinks it.

This table compares the performance of CoPA using a linear transformation head and a visual transformer. The results are shown for two experimental settings: training on all datasets and training only on ImageNet. Mean accuracy and 95% confidence intervals are provided for each dataset across five separate runs, each initialized with a different random seed (41-45).

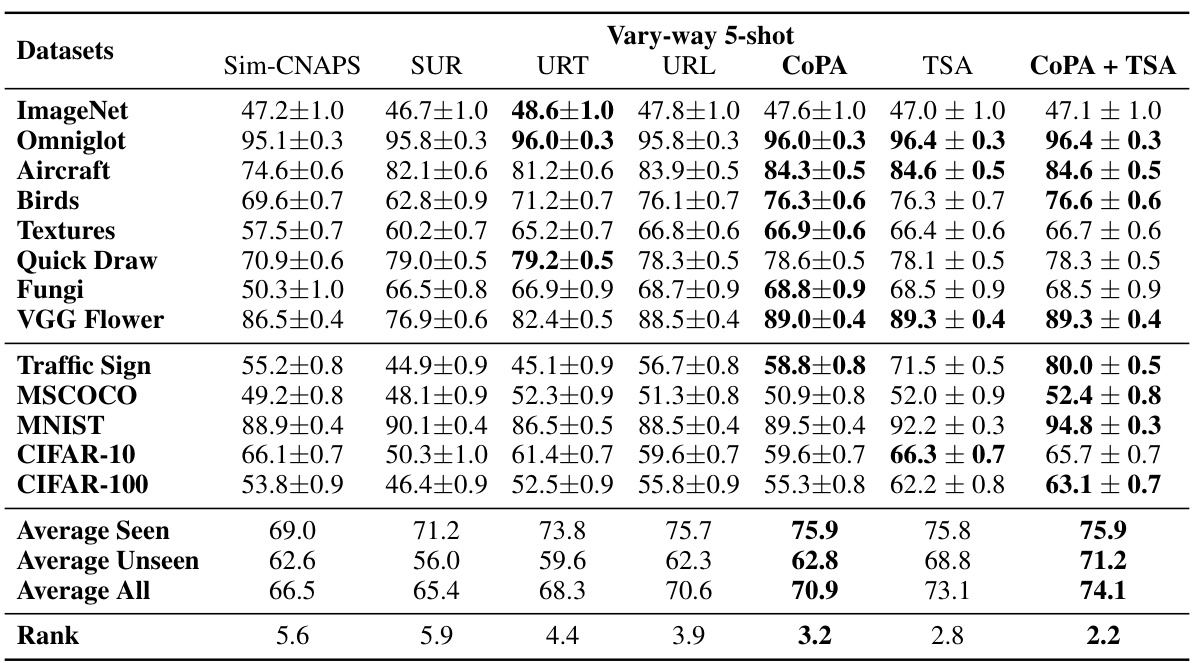

This table presents the results of the vary-way 5-shot task setting under the ’train on all datasets’ setting from the Meta-Dataset benchmark. The table compares the performance of several methods, including Sim-CNAPS, SUR, URT, URL, CoPA, TSA, and CoPA + TSA, across various datasets. Mean accuracy and a 95% confidence interval are provided for each method and dataset. The results showcase the average performance across multiple random seeds.

This table presents the results of the vary-way 5-shot experiments on the Meta-Dataset, where the number of classes and shots are randomly determined for each task. It compares the performance of CoPA against several other state-of-the-art methods, showing mean accuracy and 95% confidence intervals for each dataset. The ‘Average Seen,’ ‘Average Unseen,’ and ‘Average All’ rows provide summary statistics across all datasets, and the ‘Rank’ row shows the average ranking of each method.

This table shows the results of the analysis on how the number of support data affects the performance of CoPA. The experiment was conducted under the setting of training on all datasets. The minimum, maximum, and average number of support samples for each dataset are shown in this table. The analysis helps to understand the impact of the support data size on CoPA’s performance.

This table presents the results of the proposed CoPA method and several other state-of-the-art methods on the Meta-Dataset benchmark under the ’train on all datasets’ setting. The first 8 datasets are considered ‘seen domains’, while the last 5 are ‘unseen domains.’ The table reports mean accuracy and 95% confidence intervals for each method on each dataset, offering a comprehensive comparison of their performance across various visual domains.

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to investigate the impact of the number of model parameters on the performance of the proposed CoPA method and a variant of URL with a similar number of parameters. The results are reported for various datasets under the ‘Train on all datasets’ setting, showing the mean accuracy and 95% confidence intervals for each method and dataset. The purpose is to determine if the improved performance of CoPA stems solely from its increased number of parameters or from other design features.

This table presents the results of the proposed CoPA method and other existing methods on the Meta-Dataset benchmark under the setting where all datasets are used for training. It shows the mean accuracy and 95% confidence interval for each dataset, broken down into seen and unseen domains. The table also provides an average ranking of the methods across all datasets.

Full paper#