↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language model (LLM) evaluation is currently limited by using only a few prompts, potentially impacting the reproducibility of results. This approach is problematic as it doesn’t represent the real-world diversity of prompts LLMs will encounter. This leads to inconsistent LLM rankings and inaccurate performance assessments, hindering the development of robust and reliable benchmarks.

PromptEval addresses these issues by efficiently estimating performance distributions across a large number of prompts. The proposed method uses Item Response Theory and advanced statistical techniques to borrow strength across prompts and examples, producing accurate performance quantiles, even with limited evaluations. This allows for more robust performance comparisons and identification of the most effective prompts. Experiments demonstrated its effectiveness on various benchmarks, showing that PromptEval consistently estimates performance distributions and enables accurate quantile estimations with a small evaluation budget.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because robust LLM evaluation is critical for progress in the field. Current methods often rely on limited prompt sets, leading to unreliable results. This work’s efficient multi-prompt evaluation technique is important for building better leaderboards and for applications such as LLM-as-a-judge and prompt optimization. Its theoretical guarantees and empirical validations on multiple benchmarks enhance the reliability and applicability of the proposed method.

Visual Insights#

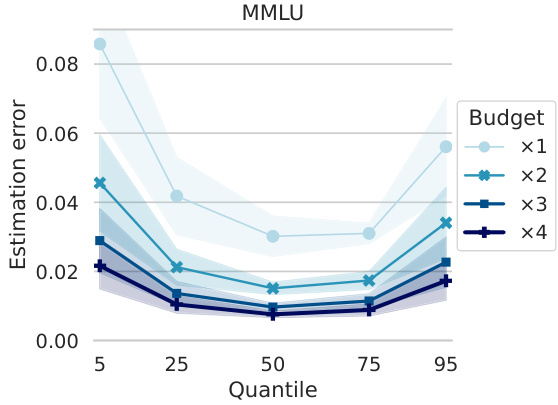

This figure displays the average estimation error for various performance quantiles (5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th) when evaluating a large language model (LLM) using different prompt templates. The x-axis represents the performance quantile being estimated, while the y-axis shows the average estimation error. Different colored lines represent different evaluation budgets, expressed as multiples of the computational cost required to evaluate one template on the MMLU benchmark. The shaded areas around the lines represent the confidence intervals for the estimation errors. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of PromptEval, as the estimation error generally decreases as the budget increases, indicating its ability to provide accurate performance estimates across a large number of prompt templates with a limited evaluation budget.

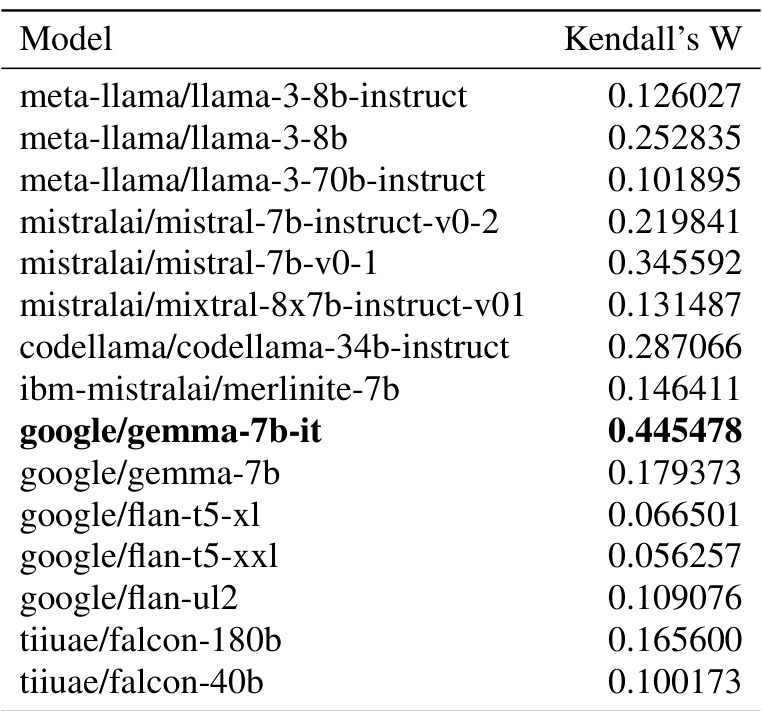

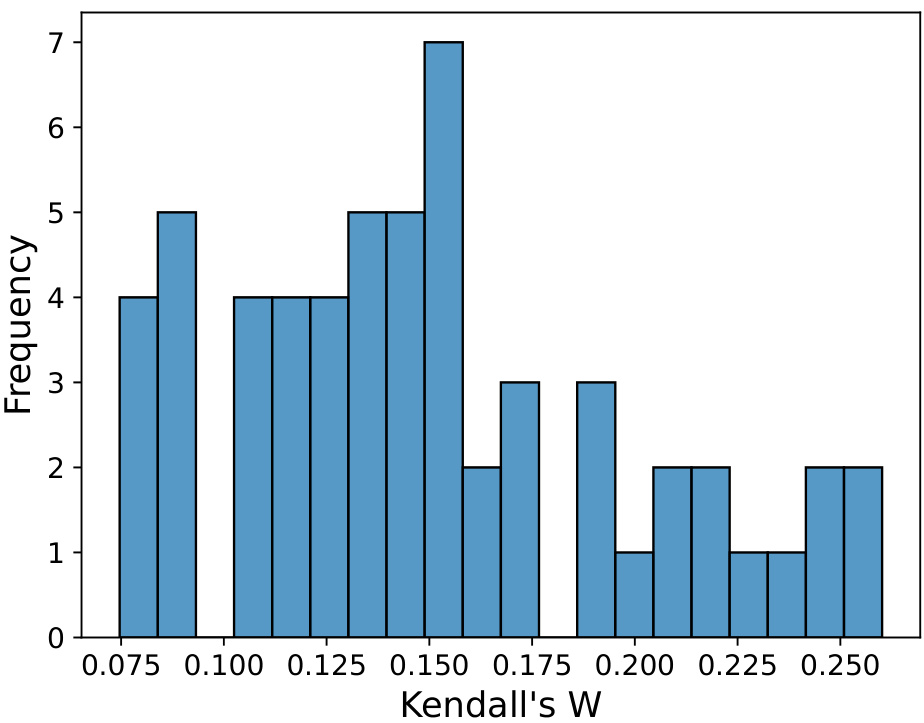

This table presents the Kendall’s W values for each of the 15 LLMs evaluated in the paper. Kendall’s W is a measure of agreement among rankings, ranging from 0 (no agreement) to 1 (perfect agreement). In this context, it measures the consistency of each model’s performance across different prompt templates within the MMLU benchmark. Higher Kendall’s W values suggest greater consistency in a model’s ranking across different prompts.

In-depth insights#

PromptEval Method#

PromptEval is a novel multi-prompt evaluation method designed to efficiently estimate the performance distribution of large language models (LLMs) across a vast number of prompt templates. It leverages the strength across prompts and examples, borrowing information to generate accurate estimates even with a limited evaluation budget. This contrasts with traditional methods relying on single prompts, which are highly susceptible to the sensitivity of LLMs to specific prompt variations. PromptEval’s key innovation lies in using a probabilistic model, likely Item Response Theory (IRT), to estimate performance across the full distribution of prompts, enabling the calculation of robust performance metrics such as quantiles (e.g., median or top 95%). This allows for a more comprehensive and reliable evaluation of LLMs, reducing reliance on potentially misleading single-prompt results. Empirically, PromptEval has demonstrated efficacy in accurately estimating quantiles across numerous prompt templates on established benchmarks, highlighting its potential for improving the robustness and reproducibility of LLM leaderboards and aiding in applications like LLM-as-a-judge and best-prompt identification. The method’s efficiency is a key advantage, making large-scale multi-prompt evaluations feasible.

LLM Sensitivity#

The concept of “LLM Sensitivity” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on the significant impact of slight variations in input prompts on model performance. This sensitivity underscores the instability and unreliability of relying on single prompts for evaluation, particularly concerning the reproducibility of benchmark results. Minor changes to phrasing, structure, or even contextual information within a prompt can drastically alter the LLM’s output and subsequent accuracy scores. Consequently, a single-prompt evaluation strategy falls short of providing a holistic performance assessment. To address this challenge, researchers advocate for multi-prompt evaluation frameworks, emphasizing the importance of estimating the performance distribution across various prompt variants. Understanding and quantifying LLM sensitivity is vital for developing more robust benchmarks, improving model evaluation practices, and building more resilient applications that are less susceptible to unpredictable responses due to prompt variations.

Benchmark Analysis#

A robust benchmark analysis is crucial for evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs). It should involve multiple, diverse benchmarks to capture a wide range of LLM capabilities, avoiding over-reliance on a single benchmark that might not fully represent the model’s strengths and weaknesses. The selection of benchmarks should be carefully justified, considering factors such as task types, data distribution, and evaluation metrics. A good analysis will compare results across different benchmarks, identifying consistent patterns and highlighting discrepancies. Statistical significance testing is essential to ensure that observed performance differences are not due to random chance. Furthermore, the analysis should explore the sensitivity of LLM performance to various factors such as prompt variations, dataset biases, and evaluation metrics. Investigating these factors helps reveal the robustness and generalizability of the models. Finally, a well-executed benchmark analysis will critically discuss limitations and potential biases in the chosen benchmarks, fostering transparency and guiding future research in LLM evaluation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore PromptEval’s application in low-resource settings, investigating its performance with limited evaluation budgets and smaller prompt sets. Adapting PromptEval to handle different evaluation metrics beyond accuracy, such as those focusing on fluency or coherence, would broaden its utility. The impact of prompt engineering techniques on PromptEval’s performance also warrants investigation, evaluating how different prompt generation methods affect the accuracy and stability of the resulting performance distributions. Furthermore, exploring PromptEval’s effectiveness across a wider range of LLMs, including those with varying architectures and sizes, and on diverse benchmark datasets beyond the three examined in the paper would strengthen its generalizability. Finally, research could focus on developing more sophisticated IRT models within the PromptEval framework, potentially incorporating more nuanced covariate features to better capture the complex interactions between prompts and LLMs. This could lead to even more accurate and robust performance estimations under various evaluation conditions.

Limitations#

A thoughtful analysis of limitations in a research paper is crucial for evaluating its validity and impact. Identifying limitations demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the research process, acknowledging potential weaknesses and areas for future improvement. A strong limitations section should transparently address factors that may affect the reliability or generalizability of the findings. This might involve discussing limitations in data collection, methodology, sample size, or the scope of the study. Acknowledging limitations enhances the paper’s credibility, showing that the authors are aware of potential biases or constraints in their work. By explicitly stating limitations, researchers open the door for future studies to address these weaknesses, potentially improving upon the current work and expanding the knowledge base. Well-articulated limitations also highlight the boundaries of the study’s conclusions, preventing overgeneralization and ensuring the findings are interpreted within their appropriate context. This careful consideration of limitations is a hallmark of rigorous and responsible research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

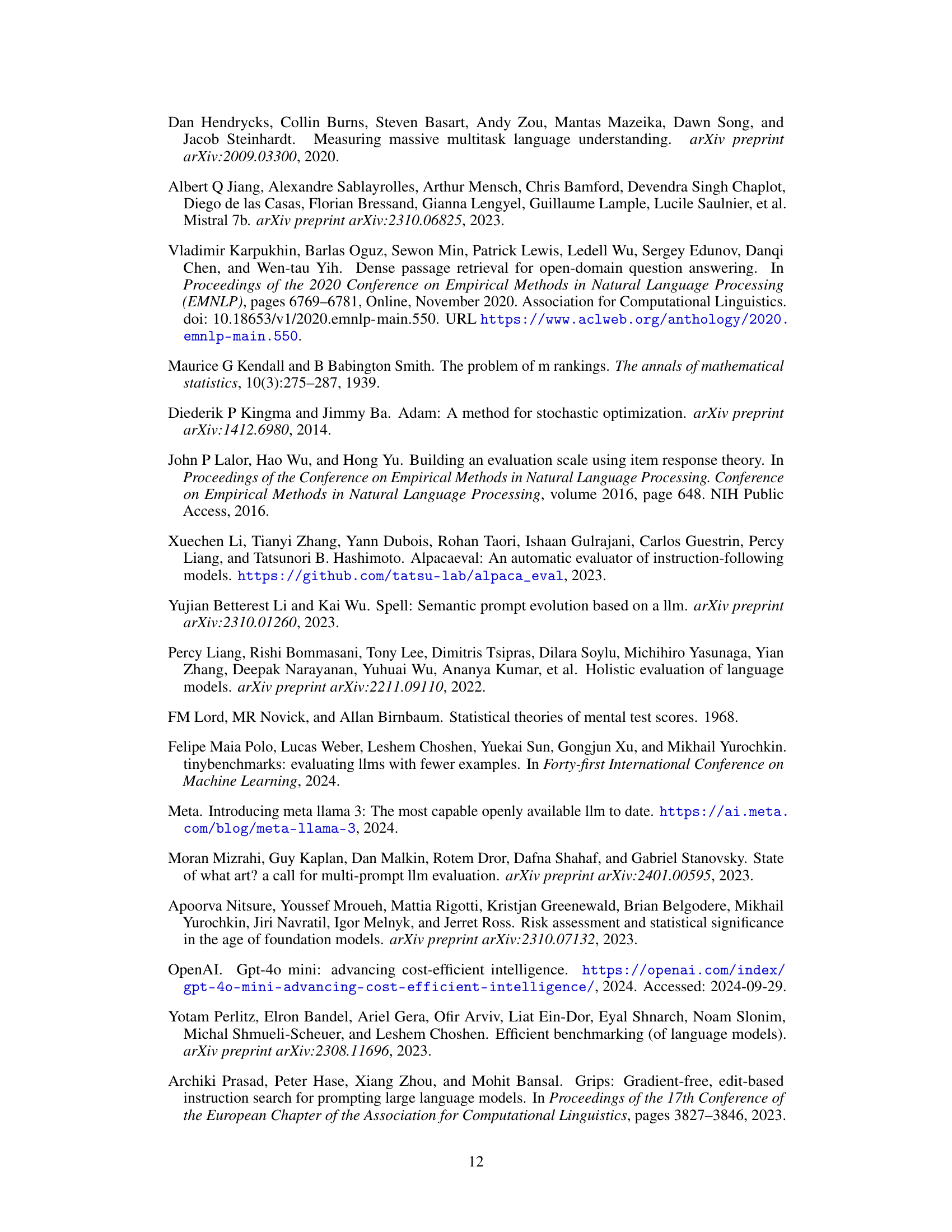

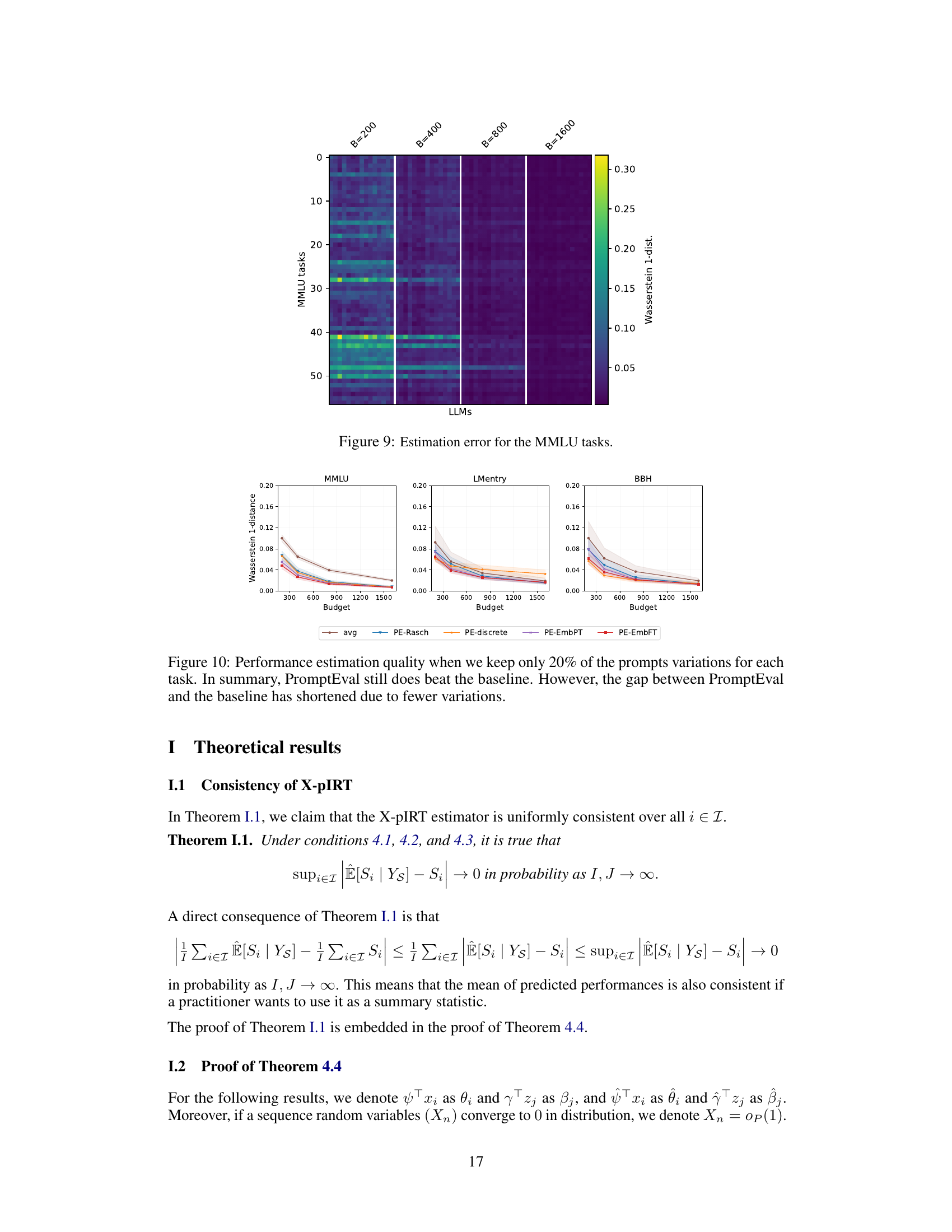

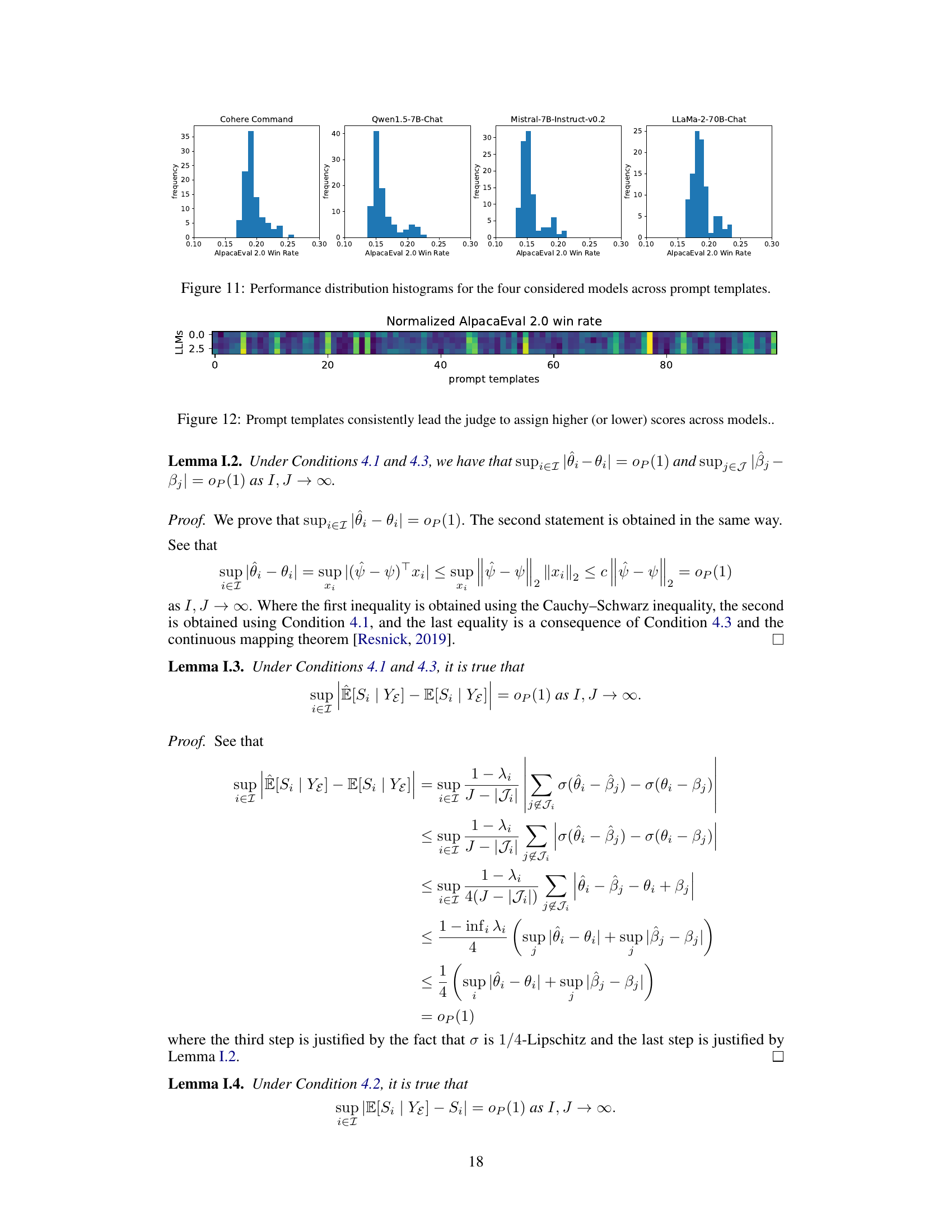

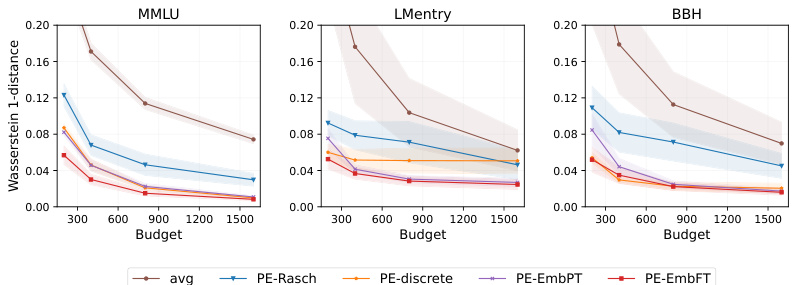

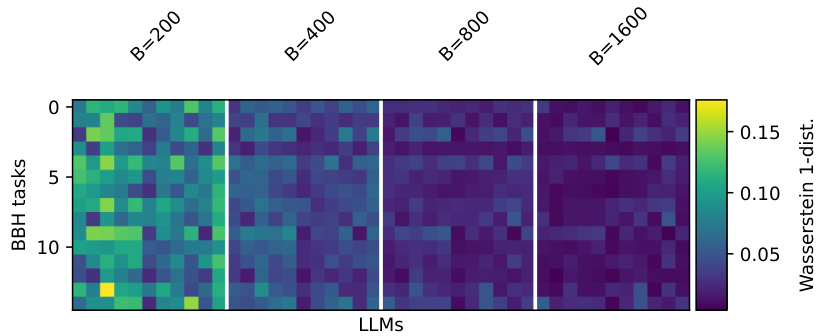

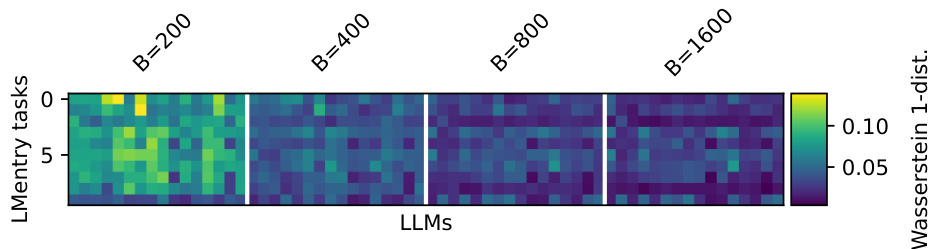

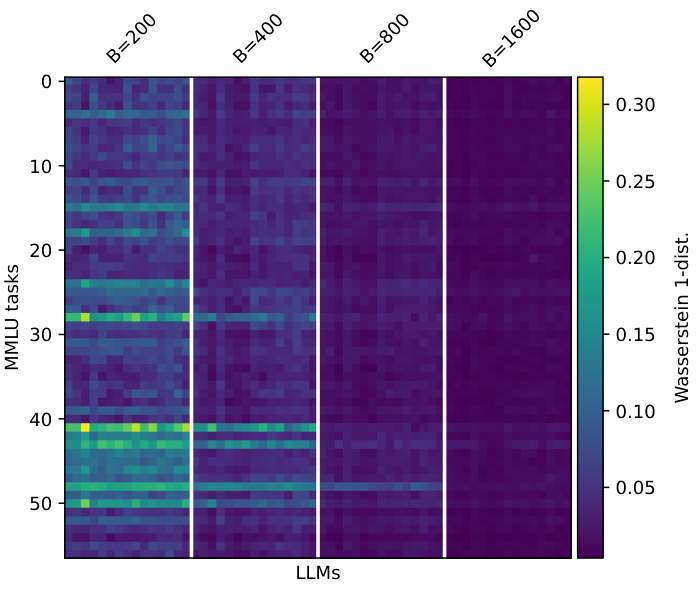

The figure displays the Wasserstein-1 distance, a measure of the difference between the true performance distribution and the estimated distribution using different methods (avg, PE-Rasch, PE-discrete, PE-EmbPT, PE-EmbFT) across three benchmarks (MMLU, LMentry, BBH) at different evaluation budget sizes. Lower values indicate better estimation accuracy. The shaded areas represent the standard error across multiple random evaluations. The figure shows that PromptEval methods (PE variants) significantly outperform the baseline average method (avg) across all benchmarks and budget sizes.

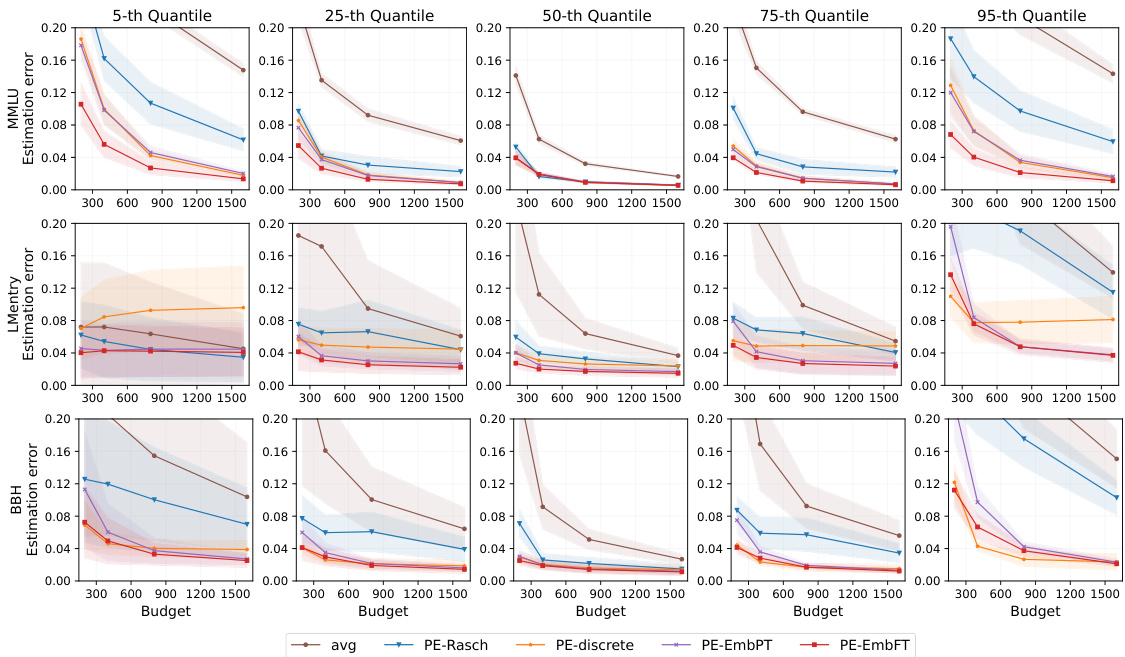

This figure shows the performance of different variations of PromptEval in estimating various performance quantiles (5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th) across three different benchmarks (MMLU, LMentry, and BBH). The x-axis represents the evaluation budget, and the y-axis represents the estimation error. The different colored lines represent different variations of the PromptEval method, allowing for a comparison of their performance under varying conditions. The shaded area around each line indicates the uncertainty in the estimation.

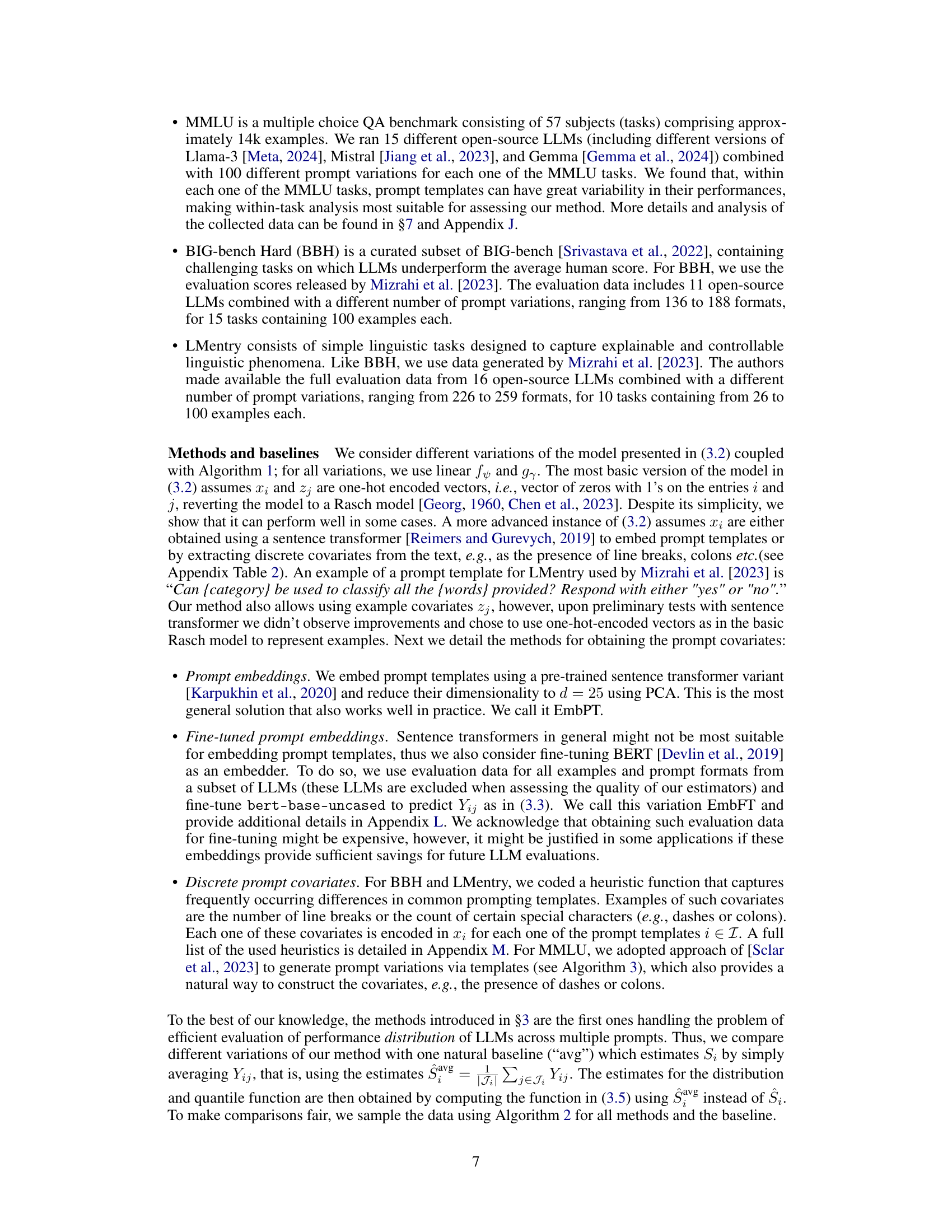

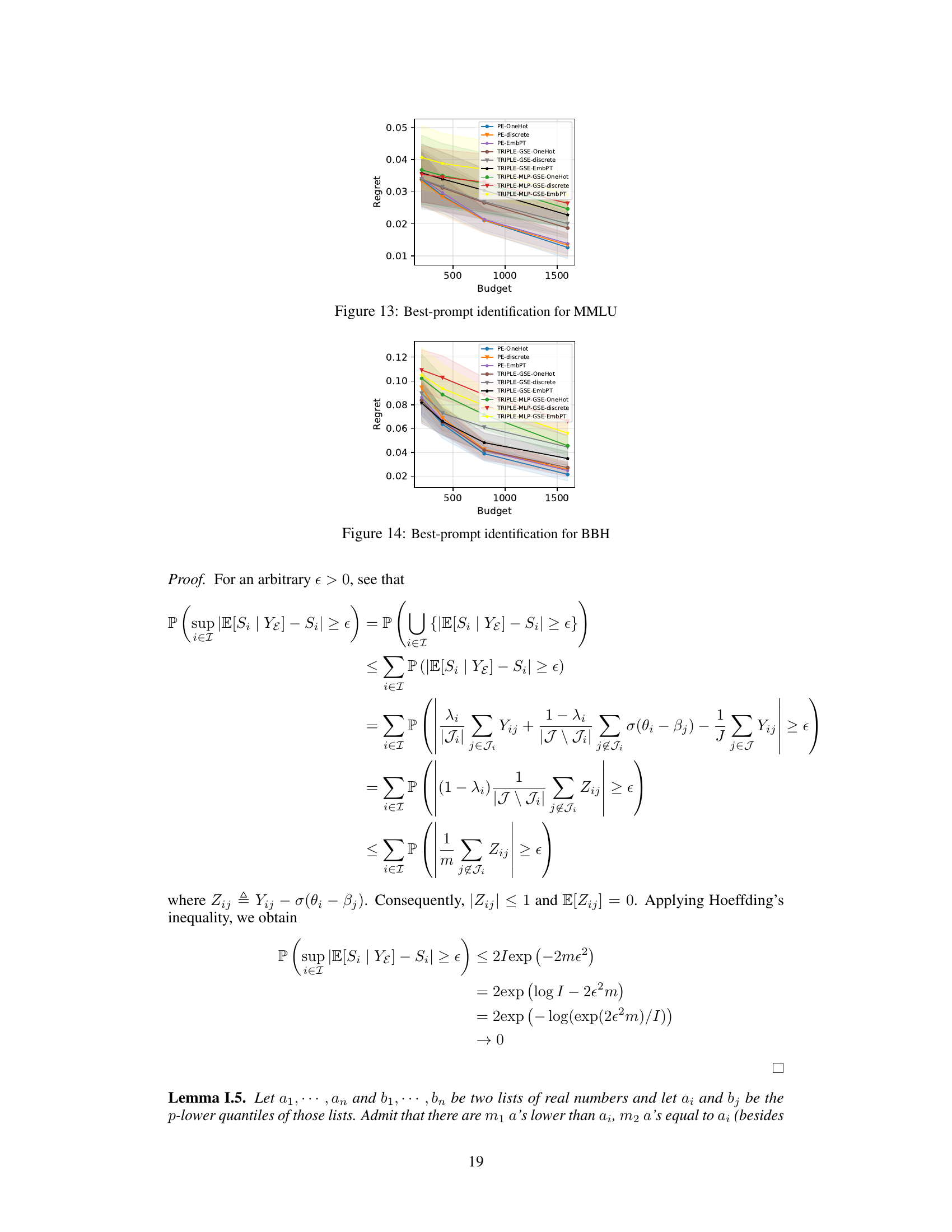

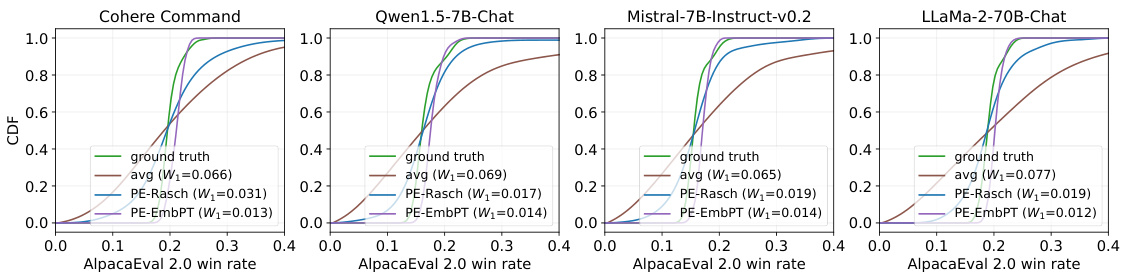

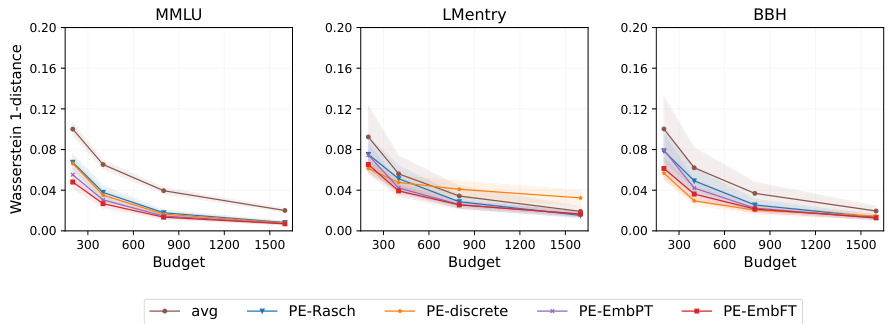

This figure shows the performance distribution estimations using different methods (ground truth, average, PromptEval using Rasch model, and PromptEval using pre-trained embeddings) for four different LLMs (Cohere Command, Qwen1.5-7B-Chat, Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, LLaMa-2-70B-Chat) on the AlpacaEval 2.0 benchmark with 100 prompt variations. The Wasserstein-1 distance (W1) is used to measure the estimation error for each method.

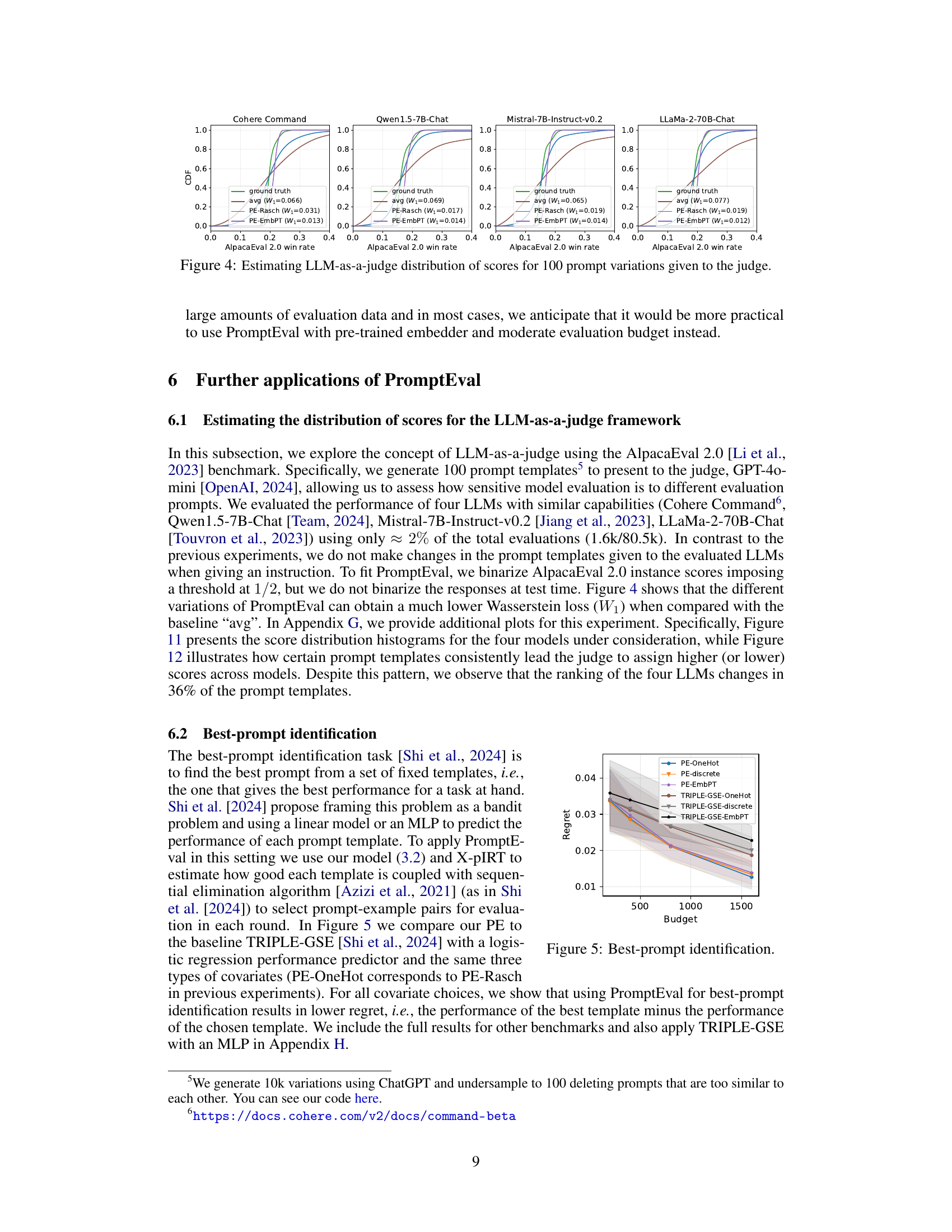

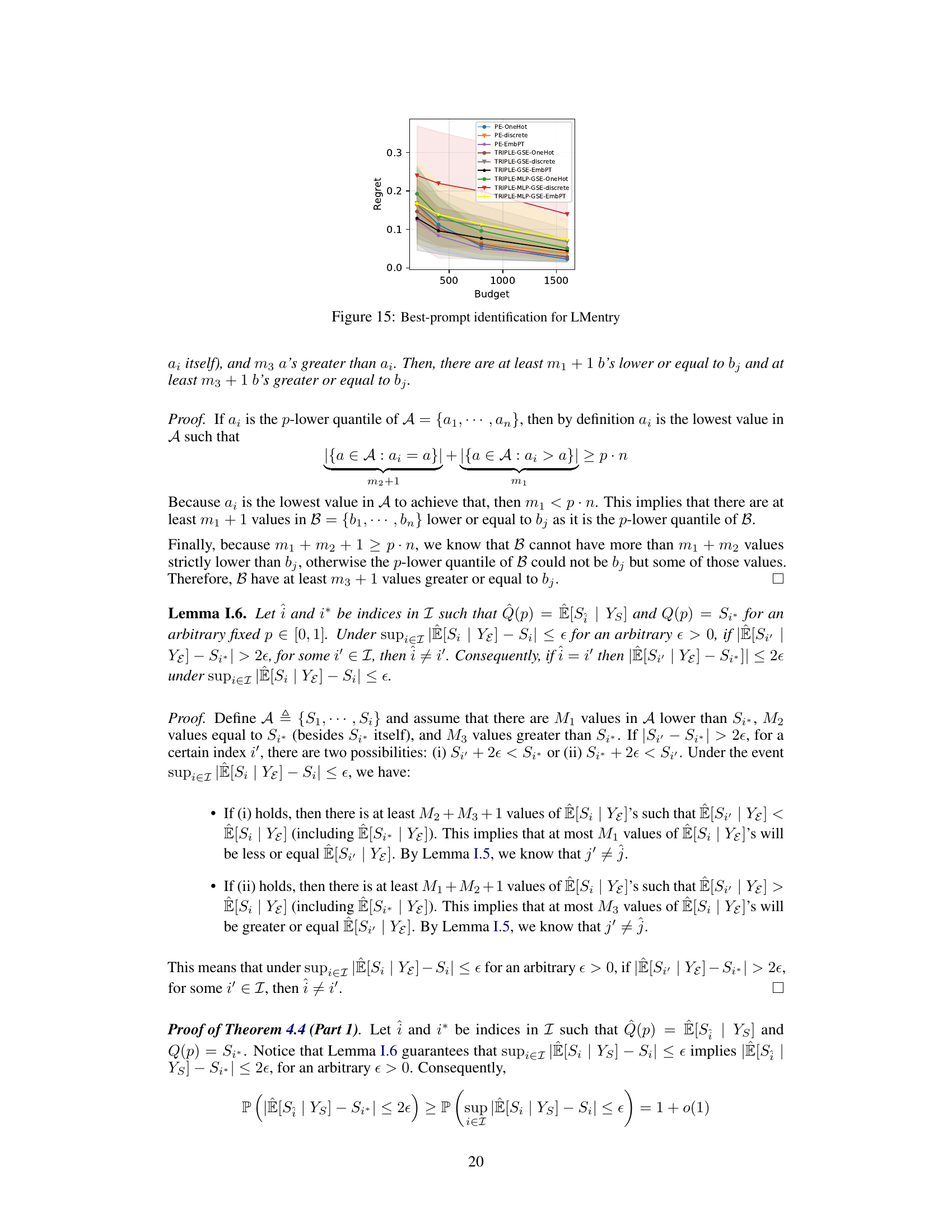

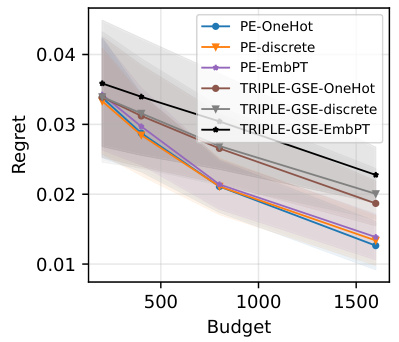

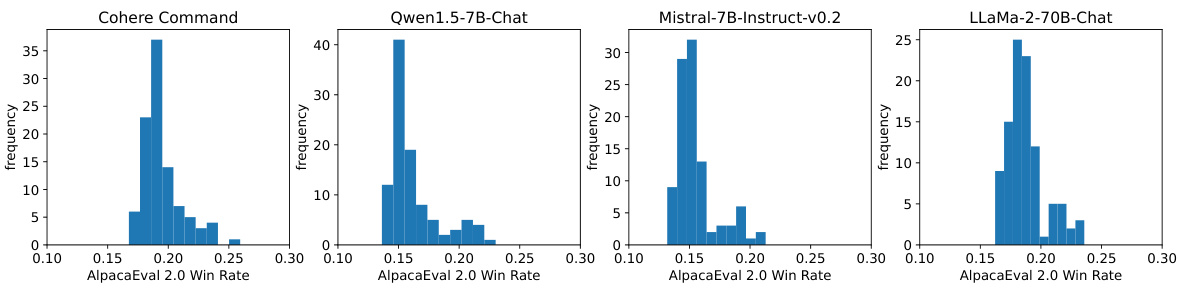

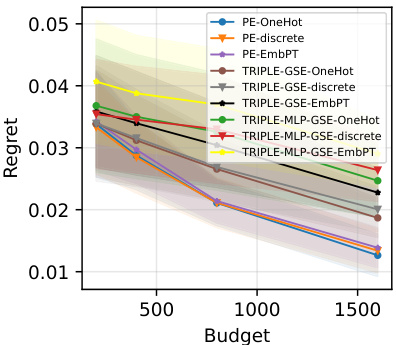

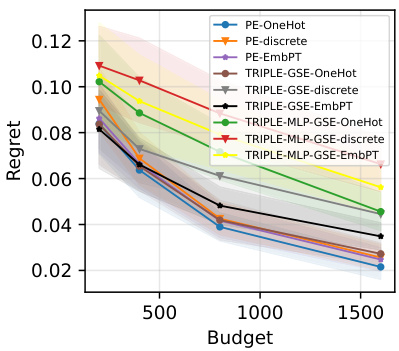

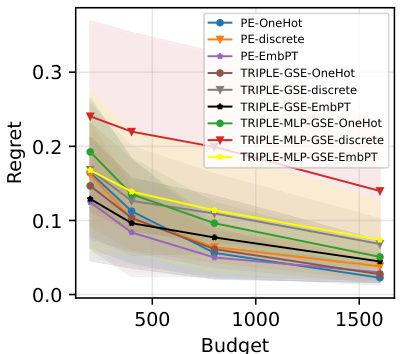

This figure compares the performance of PromptEval against the TRIPLE-GSE baseline in a best-prompt identification task. It shows the regret (difference between the best prompt’s performance and the chosen prompt’s performance) across different evaluation budgets. Different versions of PromptEval (using different types of prompt covariates) are compared, demonstrating its superior performance across various settings.

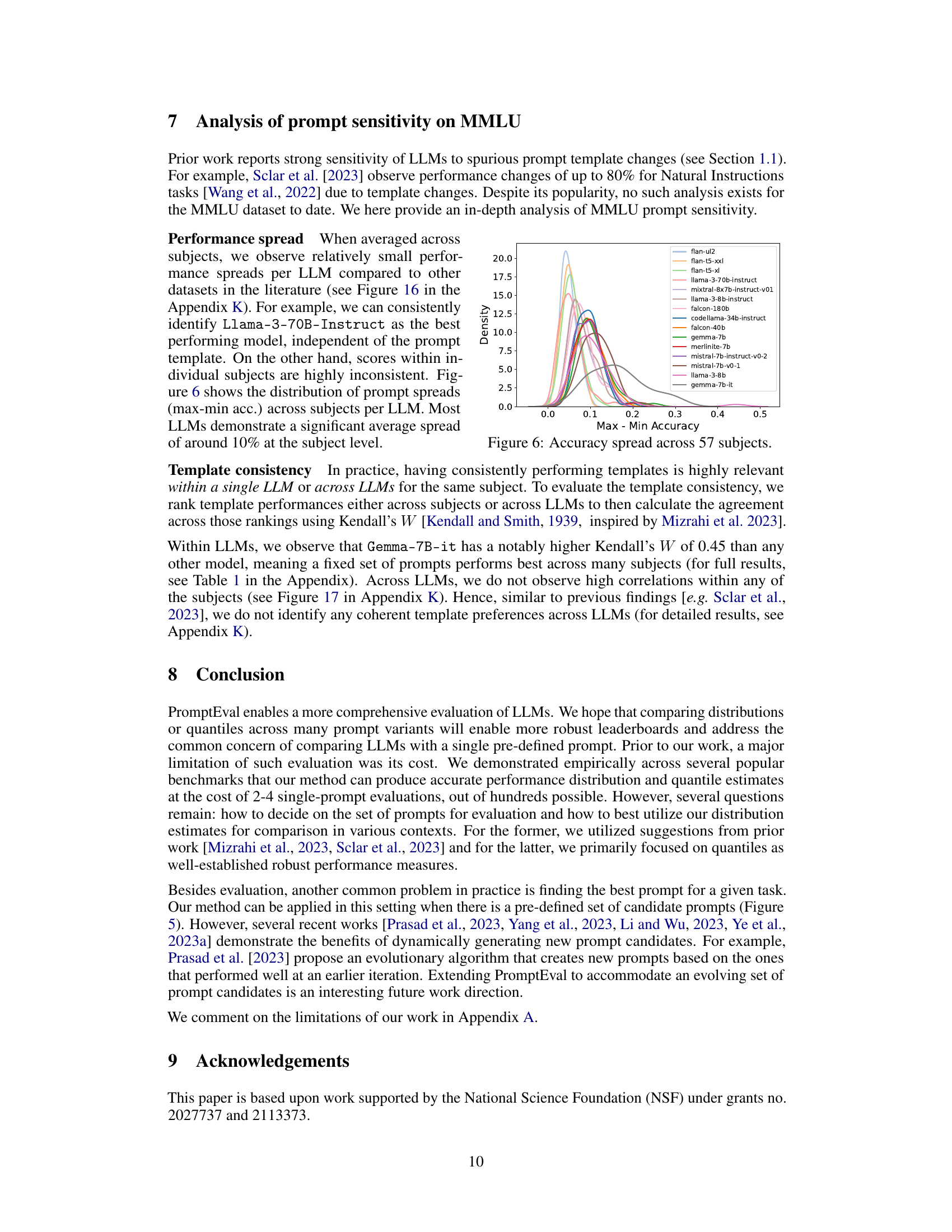

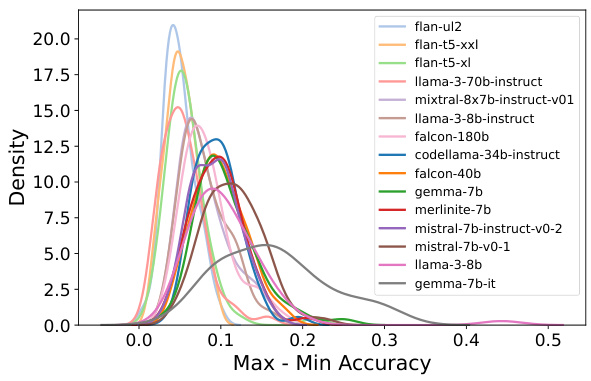

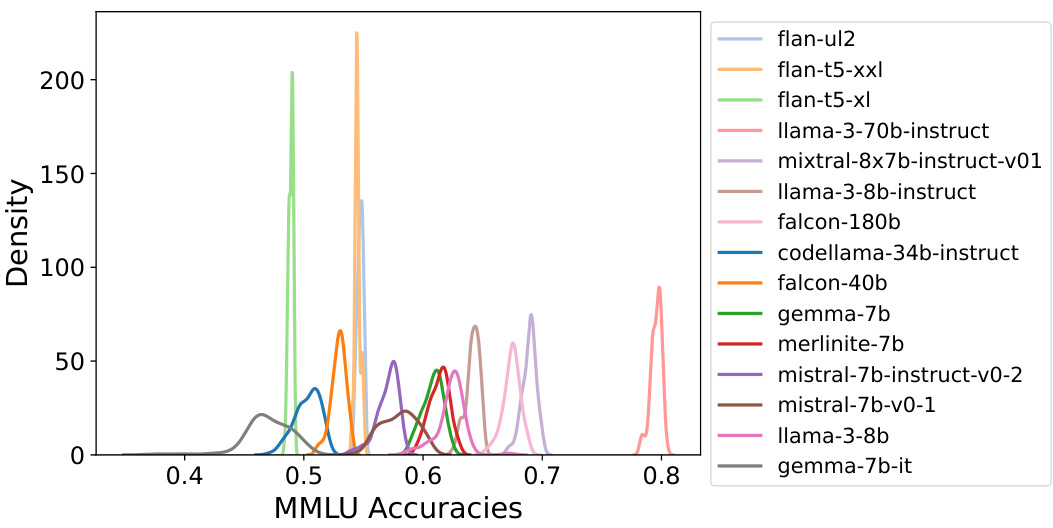

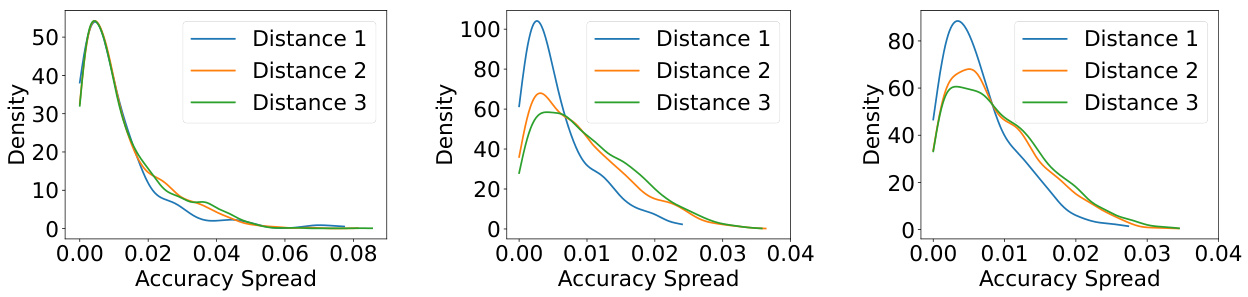

The figure shows the distribution of accuracy spreads (the difference between the maximum and minimum accuracy across different prompt templates) for various LLMs across the 57 subjects in the MMLU benchmark. The x-axis represents the spread in accuracy, and the y-axis represents the density. Each curve represents a different LLM. The figure illustrates the variability in LLM performance depending on the prompt used, even within a single subject. This variability highlights the importance of methods like PromptEval, which aim to estimate LLM performance across a range of prompts.

The figure shows the Wasserstein-1 distance between the estimated and true performance distributions for three different benchmarks (MMLU, BIG-bench Hard, and LMentry). It compares the performance of PromptEval against a baseline method (‘avg’). Different variations of PromptEval are shown, each using a different method to estimate performance. The x-axis shows the evaluation budget and the y-axis represents the Wasserstein-1 distance which measures the difference between distributions. Lower values indicate better estimation accuracy. The results show PromptEval outperforms the baseline across all benchmarks and budget levels.

This figure compares the performance of PromptEval against a baseline method in estimating the performance distribution of LLMs across different prompt templates. It shows the Wasserstein-1 distance, a metric quantifying the difference between the true and estimated performance distributions for three benchmarks (MMLU, BBH, and LMentry) across various evaluation budgets. The different colored lines represent different variations of the PromptEval method, highlighting their effectiveness in accurately estimating the LLM performance distribution, even with limited evaluations.

The figure displays the effectiveness of different variations of PromptEval (PE) against the ‘avg’ baseline strategy in estimating the performance distribution across prompt templates. It shows Wasserstein-1 distance errors for performance distribution estimation on three benchmarks (MMLU, LMentry, and BBH) across different evaluation budgets. Five variations of PromptEval are compared: PE-Rasch, PE-discrete, PE-EmbPT, PE-EmbFT, and the average baseline. The results demonstrate that PromptEval consistently outperforms the baseline, particularly as the budget increases. The use of pre-trained embeddings (PE-EmbPT) shows promising results across benchmarks.

This figure displays the effectiveness of different variations of PromptEval (PE) against the ‘avg’ baseline strategy in estimating the performance distribution of LLMs across various prompt templates. The x-axis represents the evaluation budget (number of evaluations), and the y-axis shows the Wasserstein-1 distance, which measures the difference between the true performance distribution and the estimated distribution. The figure shows results for three benchmarks: MMLU, LMentry, and BBH. Each line represents a different method: ‘avg’ (simple average of scores), PE-Rasch (a basic IRT model), PE-discrete (using discrete prompt features), PE-EmbPT (using pre-trained embeddings for prompts), and PE-EmbFT (using fine-tuned embeddings for prompts). The shaded area around each line represents the standard deviation of the estimation errors across multiple runs.

This figure displays the effectiveness of different variations of PromptEval (PE) against a baseline strategy (‘avg’) in estimating the performance distribution of LLMs across various prompt templates. The x-axis represents the evaluation budget (in multiples of a single-prompt evaluation), and the y-axis represents the Wasserstein-1 distance, a measure of the error in estimating the performance distribution. The figure includes results for three benchmarks: MMLU, BIG-bench Hard (BBH), and LMentry. Each line represents a different method for estimating the distribution, with PE-Rasch, PE-discrete, PE-EmbPT, and PE-EmbFT representing variations of PromptEval, showcasing the use of different covariates.

This heatmap visualizes the consistency of prompt templates in influencing the judge’s scores across different LLMs. Each row represents a prompt template, and each column represents an LLM. The color intensity indicates the score assigned by the judge (GPT-4), ranging from lower scores (darker colors) to higher scores (brighter colors). The figure demonstrates that certain templates consistently elicit either higher or lower scores across all LLMs, suggesting a level of predictability in prompt influence.

The figure shows the comparison of regret between PromptEval and TRIPLE-GSE for best-prompt identification task across three different benchmarks. PromptEval consistently shows lower regret compared to TRIPLE-GSE, indicating its effectiveness in identifying the best prompt efficiently. The different line styles represent different variations of PromptEval and TRIPLE-GSE, each using different types of covariates. The x-axis represents the budget, and the y-axis represents the regret.

This figure compares the regret of PromptEval against the baseline TRIPLE-GSE [Shi et al., 2024] with a logistic regression performance predictor using one-hot encoding, discrete covariates, and pre-trained embeddings for covariates. It shows that using PromptEval for best-prompt identification results in lower regret, i.e., the performance of the best template minus the performance of the chosen template.

The figure presents the performance of different variations of PromptEval in estimating various quantiles (5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th) of the performance distribution across prompt templates. It displays the estimation error for three benchmark datasets (MMLU, LMentry, and BBH) across different evaluation budgets. Each point represents the average error across multiple trials, and error bars indicate variability. The figure allows for comparison of different PromptEval variations (including those utilizing different prompt embedding methods) and a baseline average method.

This figure shows the distribution of MMLU accuracy scores across 57 subjects for 15 different LLMs. Each distribution represents the accuracy of a single LLM across all subjects. The purpose is to visualize the performance consistency of each LLM across various subjects in MMLU. The x-axis represents the MMLU accuracy, and the y-axis shows the density of the distribution.

This figure shows the average estimation error for different performance quantiles (5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 95th) when estimating performance across 100 different prompt templates using a limited evaluation budget. The budget is represented as multiples of a single-prompt evaluation. The plot illustrates that PromptEval can accurately estimate performance quantiles even with a limited budget, outperforming the baseline method, particularly for higher quantiles.

This figure presents the results of experiments evaluating the performance of different PromptEval variations in estimating performance quantiles across various benchmarks (MMLU, BBH, LMentry). The plots show the average estimation errors for different quantiles (5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 95th) across multiple tasks and LLMs, for varying evaluation budgets. The error bars represent the average error across the LLMs. The figure illustrates the effectiveness of PromptEval in accurately estimating performance quantiles, even with limited evaluation budgets, particularly for the median (50th percentile).

Full paper#