↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models lack transparency, making it hard to understand how they arrive at their predictions. Feature attribution methods aim to solve this by assigning importance scores to different input features. However, these methods often fail when unobservable factors influence the outcome. This is problematic because these unobservable confounders can lead to incorrect conclusions about feature importance.

This paper introduces a new technique called “data-faithful feature attribution” to overcome this. It uses instrumental variables—observed variables that are correlated with the unobservable confounders but don’t directly affect the outcome—to create a model that is free from the confounding effects. By using this confounder-free model, the researchers can obtain more accurate feature importance scores that better reflect the real-world relationships between features and outcomes. Their experiments showed that the new approach performs better than existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical limitation of existing feature attribution methods, which often misinterpret results due to unobservable confounders. By introducing a novel approach using instrumental variables, it enhances the reliability and accuracy of feature attributions, particularly important for applications requiring data fidelity, such as in healthcare or finance. This opens avenues for more robust and trustworthy model interpretations.

Visual Insights#

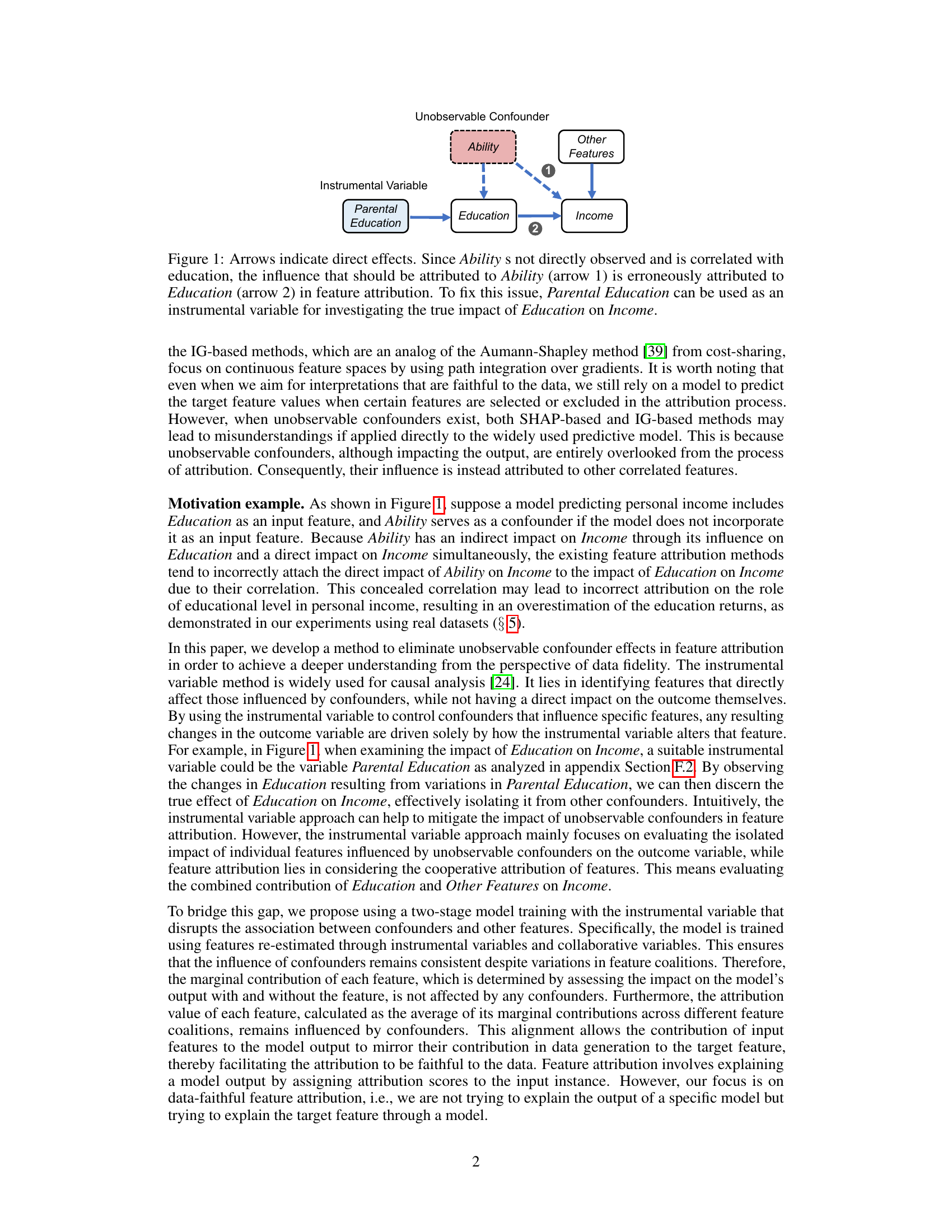

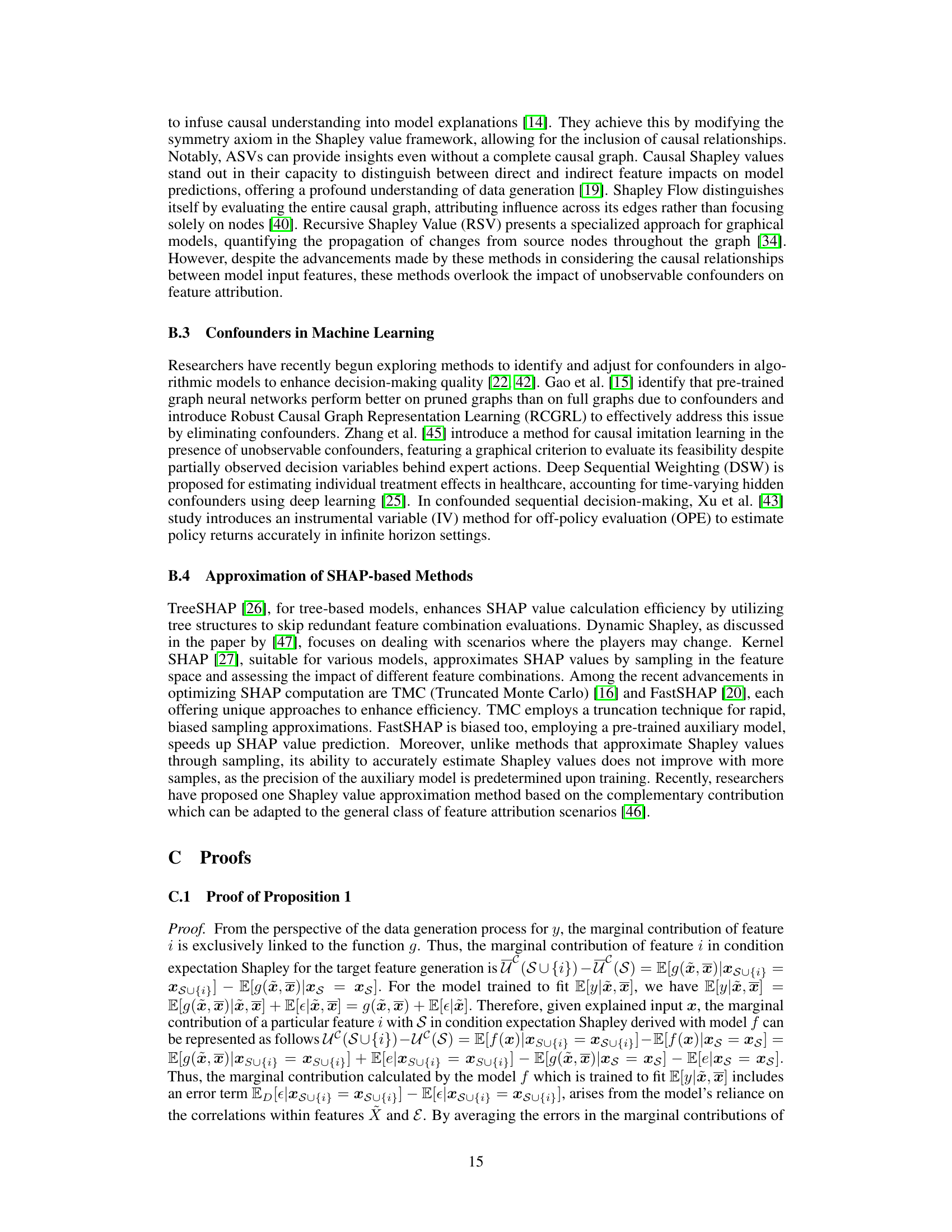

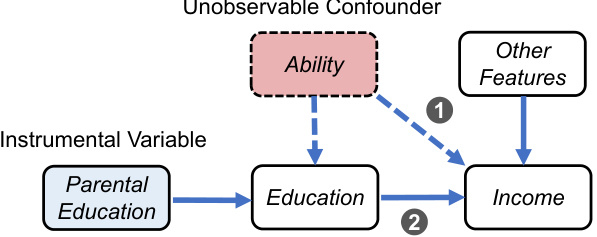

This figure illustrates the problem of unobservable confounders in feature attribution. Ability, an unobserved variable, influences both Education and Income. Because Ability and Education are correlated, standard feature attribution methods mistakenly attribute the effect of Ability on Income to Education. The solution proposed is to use Parental Education as an instrumental variable, which affects Education but not directly Income, to isolate the true effect of Education on Income.

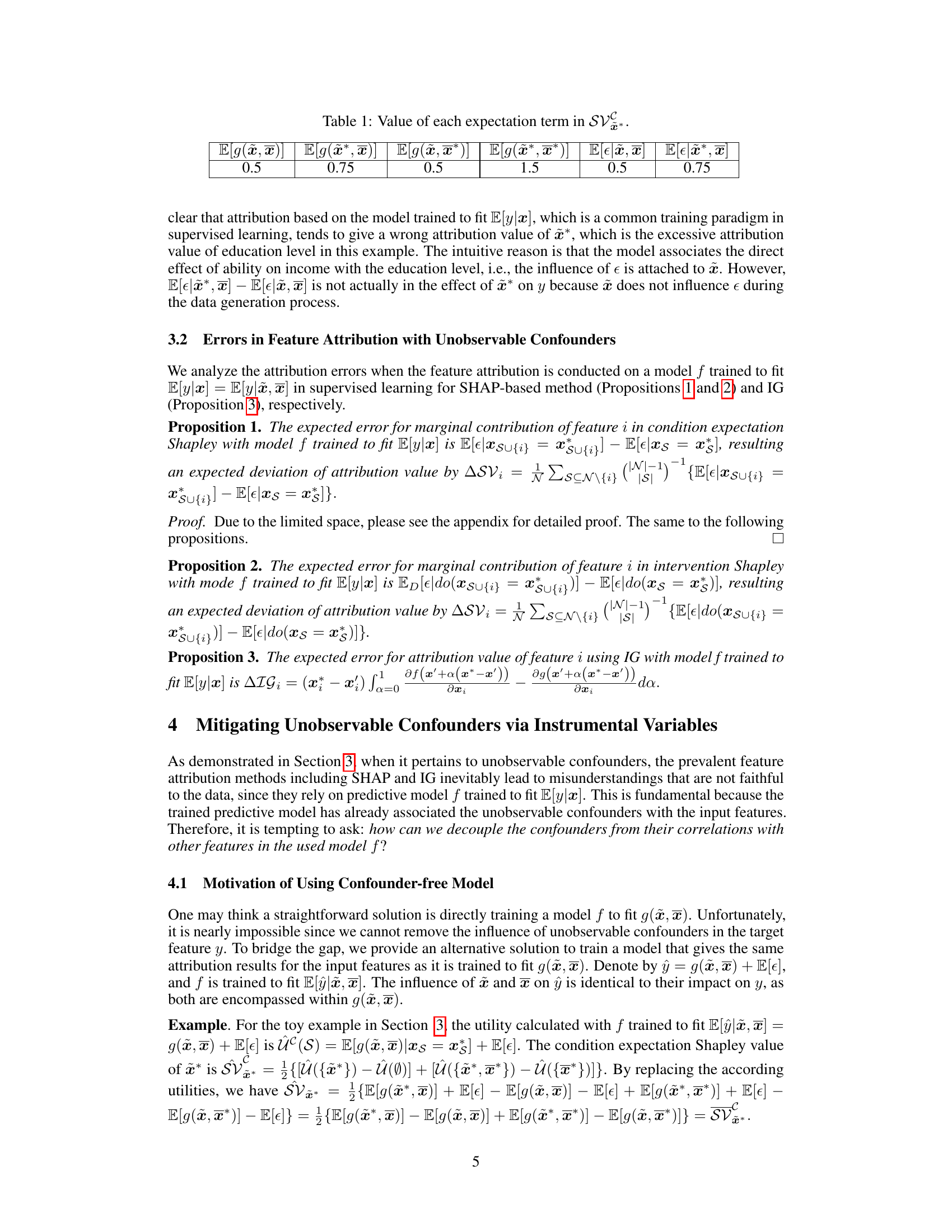

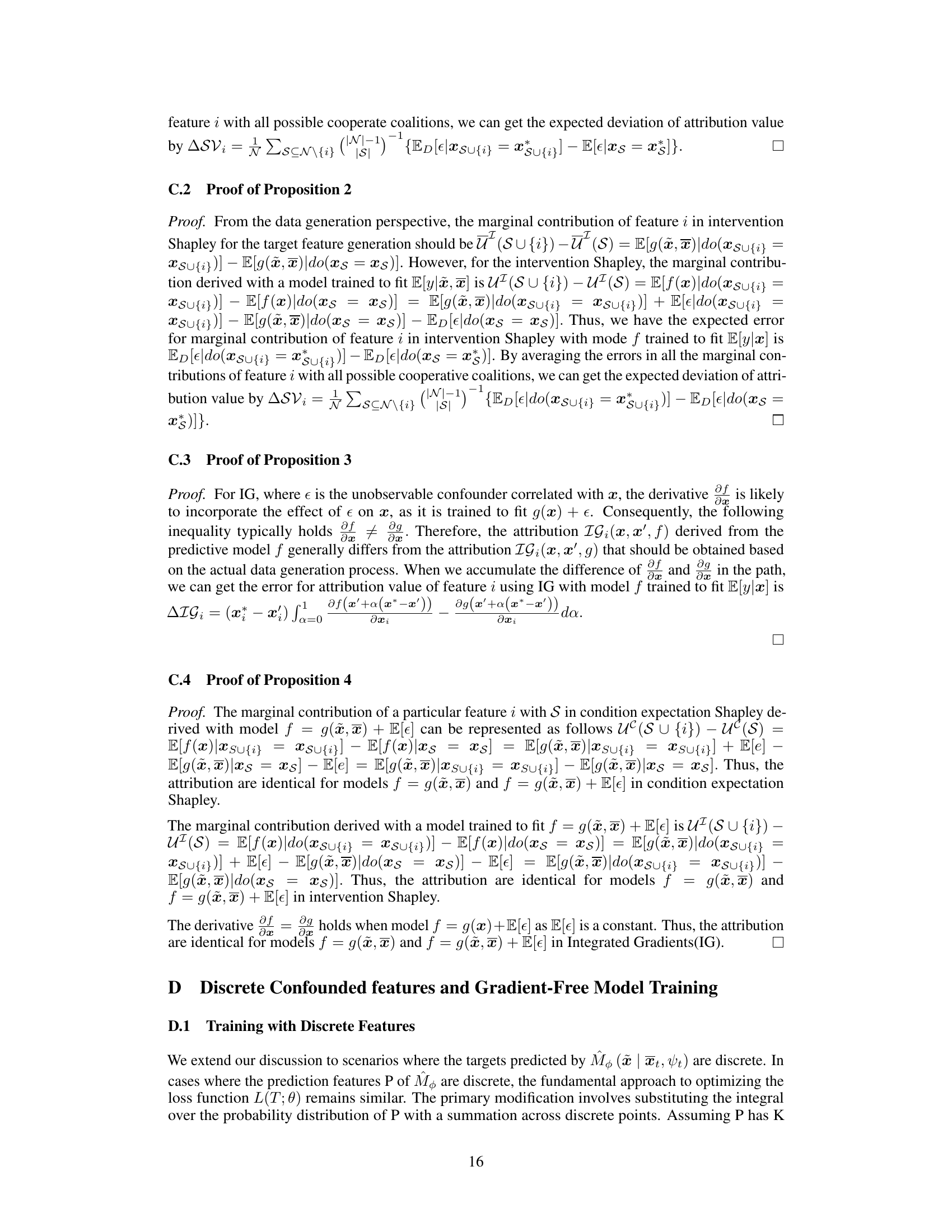

This table shows the calculated values for each expectation term used in the Shapley value calculation (SV*) within a specific example scenario described in Section 3.1 of the paper. The scenario involves a simplified model to illustrate how unobservable confounders lead to errors in feature attribution. The values represent the expected values of different functions of the input features (x, x) given different conditioning subsets of features. The values are used to compute the Shapley values to demonstrate the misattribution caused by the unobservable confounders.

In-depth insights#

Confounder Effects#

Confounding effects in research represent a significant challenge, as they introduce spurious associations between variables, obscuring true causal relationships. Unobserved confounders, in particular, pose a serious threat because their impact cannot be directly measured or controlled for in statistical analyses. The consequences of such effects include biased estimates of causal effects, rendering conclusions unreliable and potentially leading to incorrect interpretations. Mitigating these effects requires careful study design, potentially incorporating techniques like instrumental variables to isolate the effects of the variable of interest, or adjusting for observable confounders through statistical modeling. Data-faithful feature attribution methods offer a robust approach to counter the impact of confounders by focusing on interpretations consistent with the underlying data generation process. Ultimately, a thorough understanding and thoughtful mitigation of confounding effects is essential for drawing valid conclusions in research.

IV-based Attribution#

Instrumental variable (IV) methods offer a powerful approach to address the challenge of unobservable confounders in feature attribution. IV-based attribution leverages instrumental variables, which are correlated with the features of interest but not directly with the outcome, to isolate the causal effects of those features. By using a two-stage model, where the first stage estimates the feature values adjusted for confounders using the instrumental variables and the second stage builds a model using the adjusted features, IV-based methods decouple the effects of confounders from the true feature contributions. This approach leads to more accurate and reliable attribution results, particularly when data fidelity is crucial. The effectiveness of IV-based methods hinges on the validity of the instrumental variable assumptions: relevance, exogeneity, and exclusion restriction. Satisfying these assumptions is essential for obtaining unbiased and meaningful attributions. While IV-based approaches provide a robust solution for mitigating confounding, the practical limitation lies in the requirement of appropriate instrumental variables, which can be challenging to find in real-world scenarios. Therefore, careful consideration is needed in selecting and validating instrumental variables before employing this technique.

Data Fidelity Focus#

A ‘Data Fidelity Focus’ in a research paper would emphasize the importance of aligning feature attributions with the actual data generation process. This contrasts with a model-centric approach that prioritizes consistency with model predictions. Data fidelity ensures attributions reflect the true causal relationships and not merely the model’s learned correlations. The key is to avoid misinterpretations arising from unobservable confounders; these hidden variables can distort the influence of measured features, leading to inaccurate attributions. Therefore, a ‘Data Fidelity Focus’ likely involves methods to mitigate confounder bias to ensure that results accurately represent the underlying data structure and causal mechanisms, rather than artifacts of the model. This might include techniques like instrumental variables or causal inference methods to improve the robustness and reliability of the feature attribution. Such a focus is critical for applications where accurate causal understanding is paramount, such as in medical diagnosis or policy decisions, where decisions rely on the true impact of features, rather than model-specific biases.

Method Limitations#

The effectiveness of data-faithful feature attribution, while promising, is intrinsically linked to several limitations. The reliance on instrumental variables is a crucial constraint, as finding suitable instruments that meet the strict requirements of relevance, exogeneity, and exclusion restriction can be challenging in real-world scenarios. The linearity assumption underlying the theoretical analysis may not always hold, especially when dealing with complex, non-linear relationships in data generation. This could lead to misinterpretations of feature contributions, particularly in instances of non-linear confounder effects. Furthermore, robustness to the violation of instrumental variable assumptions warrants further investigation, as deviations from these assumptions could diminish the effectiveness of the approach. Finally, the computational cost associated with the two-stage modeling procedure, particularly for high-dimensional datasets, could present a practical limitation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore refining data-faithful feature attribution by addressing limitations such as dependence on instrumental variables and the assumption of linear confounding effects. Developing methods robust to non-linear relationships and capable of handling scenarios without readily available instrumental variables would significantly broaden applicability. Investigating the impact of correlated input features on data fidelity is crucial, necessitating the development of techniques that effectively account for these correlations. Furthermore, extending the framework to handle various model types, beyond neural networks, and enhancing the efficiency of approximation algorithms for large datasets are important considerations. Finally, rigorous empirical evaluations across diverse real-world datasets, encompassing different types of confounders and feature distributions, are vital for demonstrating the generalizability and robustness of the proposed approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

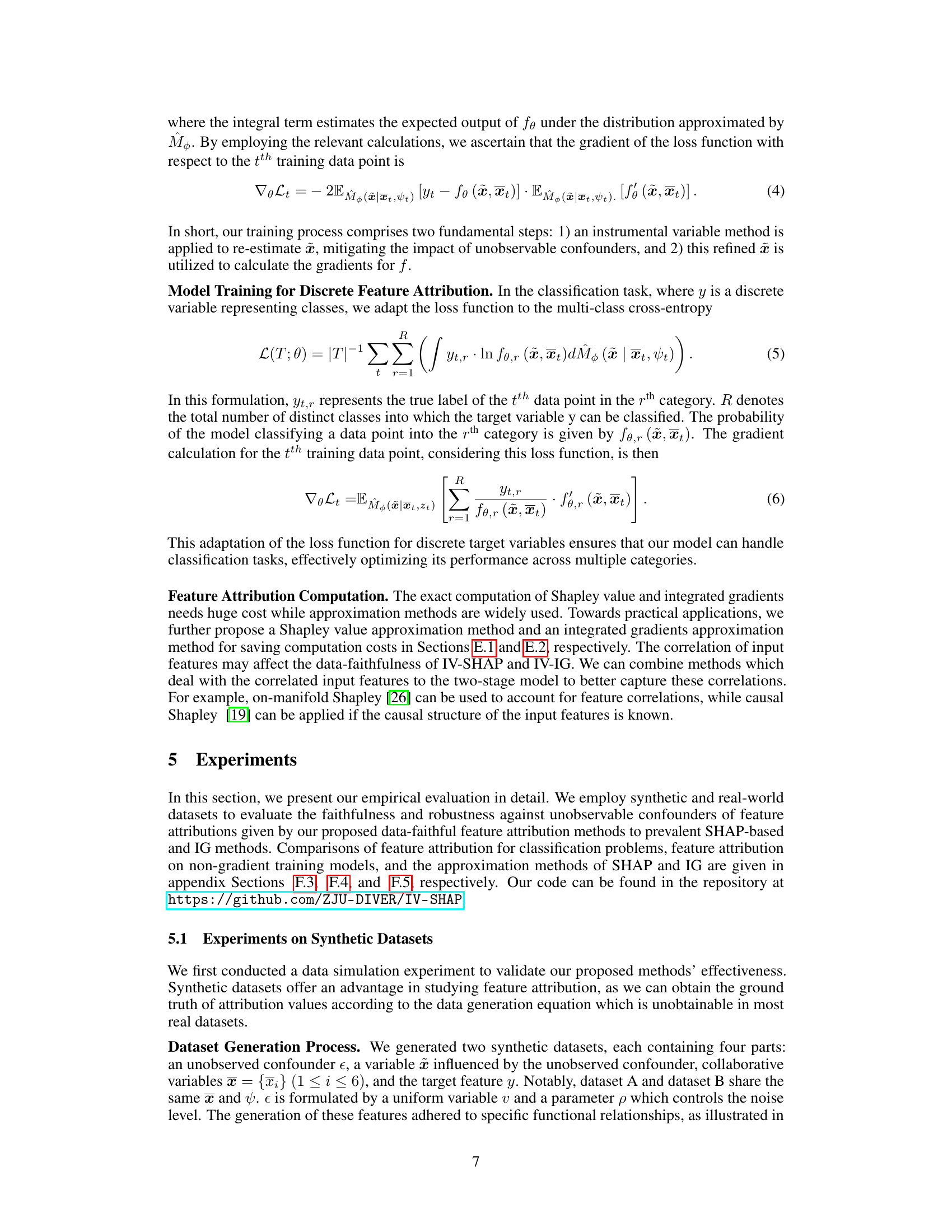

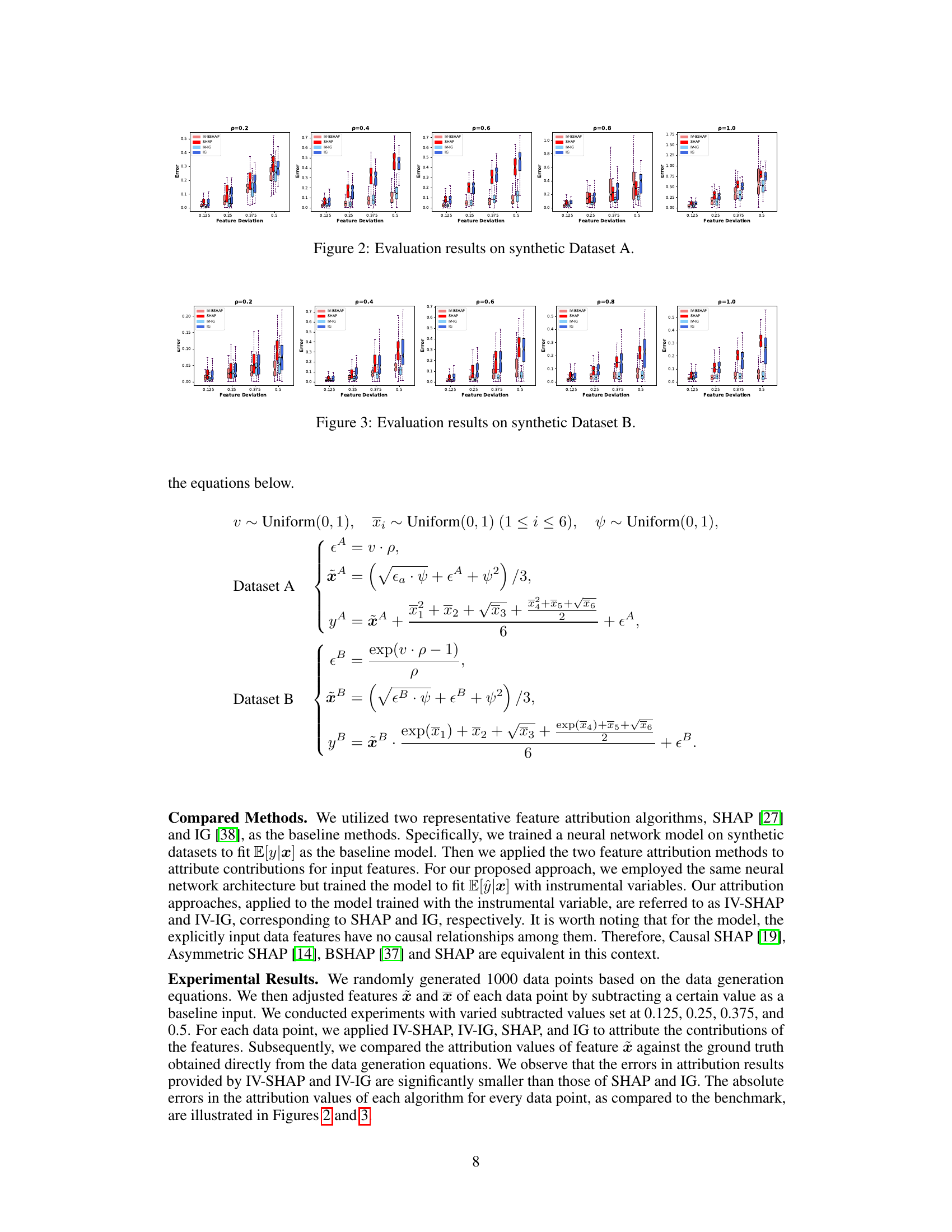

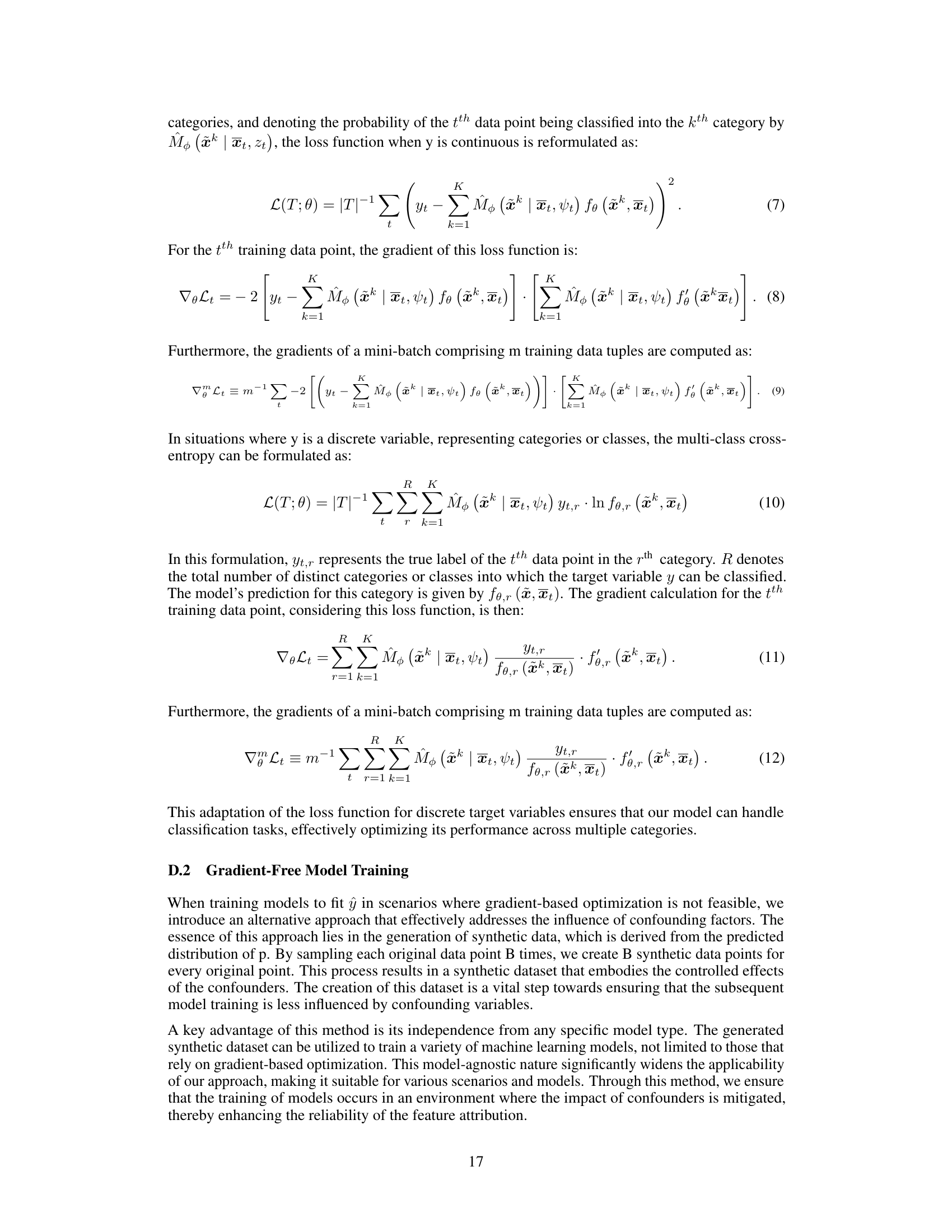

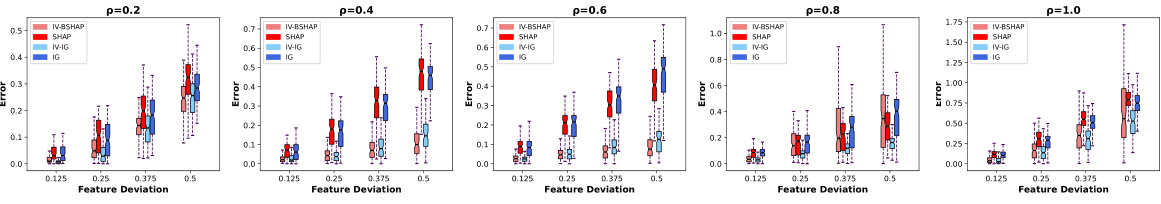

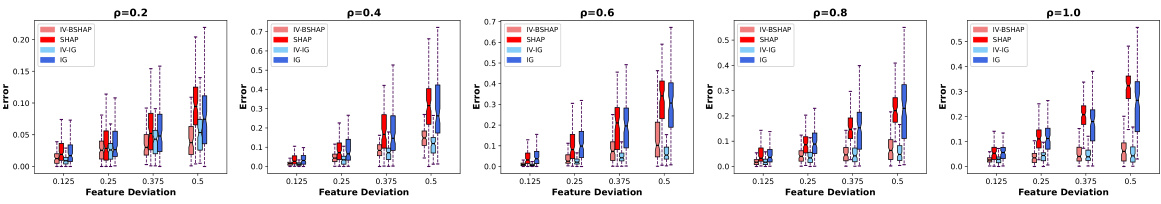

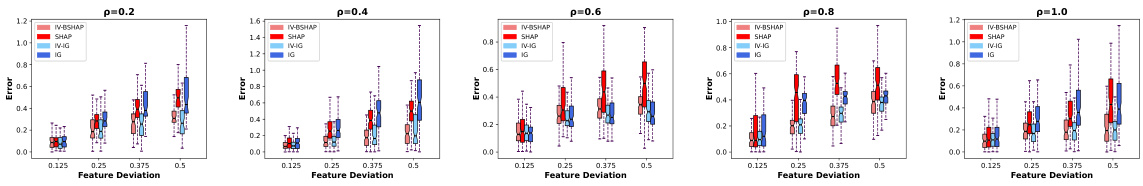

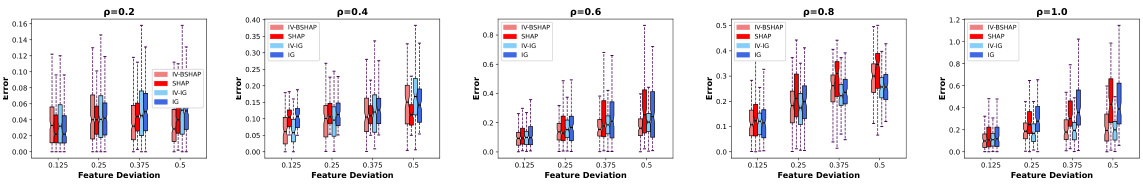

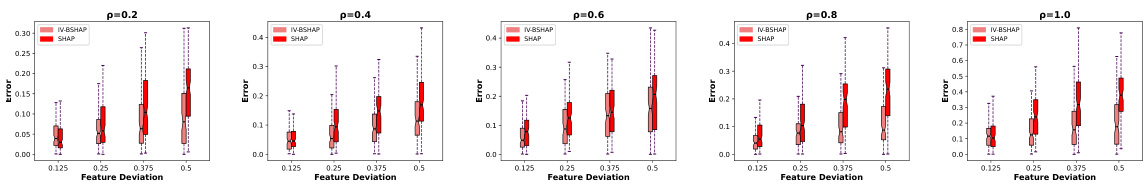

This figure displays the evaluation results for four feature attribution methods (IV-BSHAP, SHAP, IV-IG, and IG) on synthetic Dataset A. The results are presented as box plots, showing the distribution of errors in feature attribution for each method across various levels of feature deviation (0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5) and different values of parameter p (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0). The box plots show the median, quartiles, and range of the errors. This visual representation allows for a comparison of the performance of the different methods under varying conditions, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed data-faithful feature attribution methods (IV-BSHAP and IV-IG) in mitigating the effects of unobservable confounders.

This figure presents the error rates of different feature attribution methods (IV-BSHAP, SHAP, IV-IG, IG) on synthetic dataset A, categorized by the feature deviation and the parameter p (which controls the noise level). Each box plot represents the distribution of errors for each method at each combination of feature deviation and parameter p. The plot aims to show the effectiveness of the proposed data-faithful feature attribution method (IV-BSHAP, IV-IG) compared to the standard methods (SHAP, IG) in reducing errors in the presence of unobservable confounders.

This figure illustrates a causal diagram showing the relationship between education, income, and an unobservable confounder, ability. It highlights the problem of misattribution in feature attribution methods. Because ability is correlated with education, and directly affects income, feature attribution methods may mistakenly attribute the effect of ability on income to education. The solution shown is to use parental education as an instrumental variable, which affects education but not income directly, to isolate the true effect of education on income.

This figure displays the evaluation results for four different feature attribution methods (IV-BSHAP, SHAP, IV-IG, IG) on synthetic dataset A. Each subplot represents a different level of feature deviation (0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5), and within each subplot are boxplots showing the error of each method at that deviation level, for five different values of parameter p (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0). The boxplots help visualize the distribution of the errors. The figure is designed to demonstrate how the proposed methods (IV-BSHAP, IV-IG) perform against baseline methods (SHAP, IG) under different conditions.

The figure displays the evaluation results on synthetic dataset A for various feature deviation values (0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5) and different values of parameter p (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0). It shows the error in attribution values for four different methods: IV-BSHAP, SHAP, IV-IG, and IG. The box plots illustrate the distribution of errors for each method across different scenarios, allowing comparison of their accuracy in feature attribution.

The figure shows the error in feature attribution for different feature deviation values on synthetic dataset A. The error is calculated as the absolute difference between the attribution values from the proposed method and the ground truth. The proposed method is shown to have lower error than SHAP and IG in most cases.

This figure presents the evaluation results on synthetic Dataset A, comparing the performance of IV-BSHAP, SHAP, and IV-IG across different feature deviations (0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5) and different values of p (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0). Each box plot shows the distribution of errors for a specific feature deviation and p value. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed methods (IV-BSHAP and IV-IG) compared to the baseline method (SHAP) in reducing errors, especially when the feature deviation and p values are higher.

More on tables

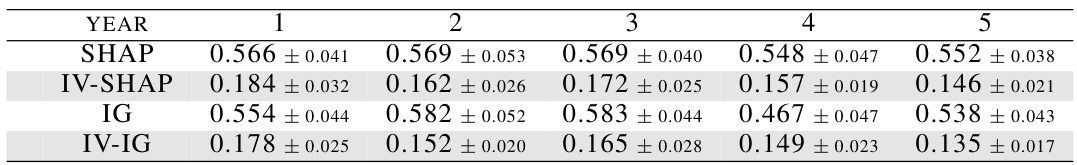

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the relative error for five independent runs of four different feature attribution methods (SHAP, IV-SHAP, IG, IV-IG) across five different years. The relative error quantifies the difference between the attribution values produced by each method and a benchmark attribution value, providing a measure of the accuracy of each method in capturing the true impact of the feature. Lower values indicate greater accuracy. The data used for this table came from the Griliches76 real-world dataset.

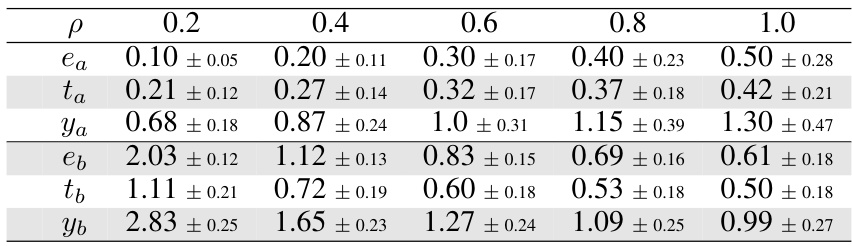

This table shows the mean and standard deviation of features (ea, ta, ya, eb, tb, yb) in the synthetic datasets for different values of parameter p (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0). These statistics provide insights into the data distribution and help in evaluating the results of the proposed feature attribution methods. The features represent an unobserved confounder, a variable influenced by the confounder, collaborative variables, and the target feature, respectively. The values show how the characteristics of these variables change with the variation in the parameter p, which controls the level of noise in the data generation process.

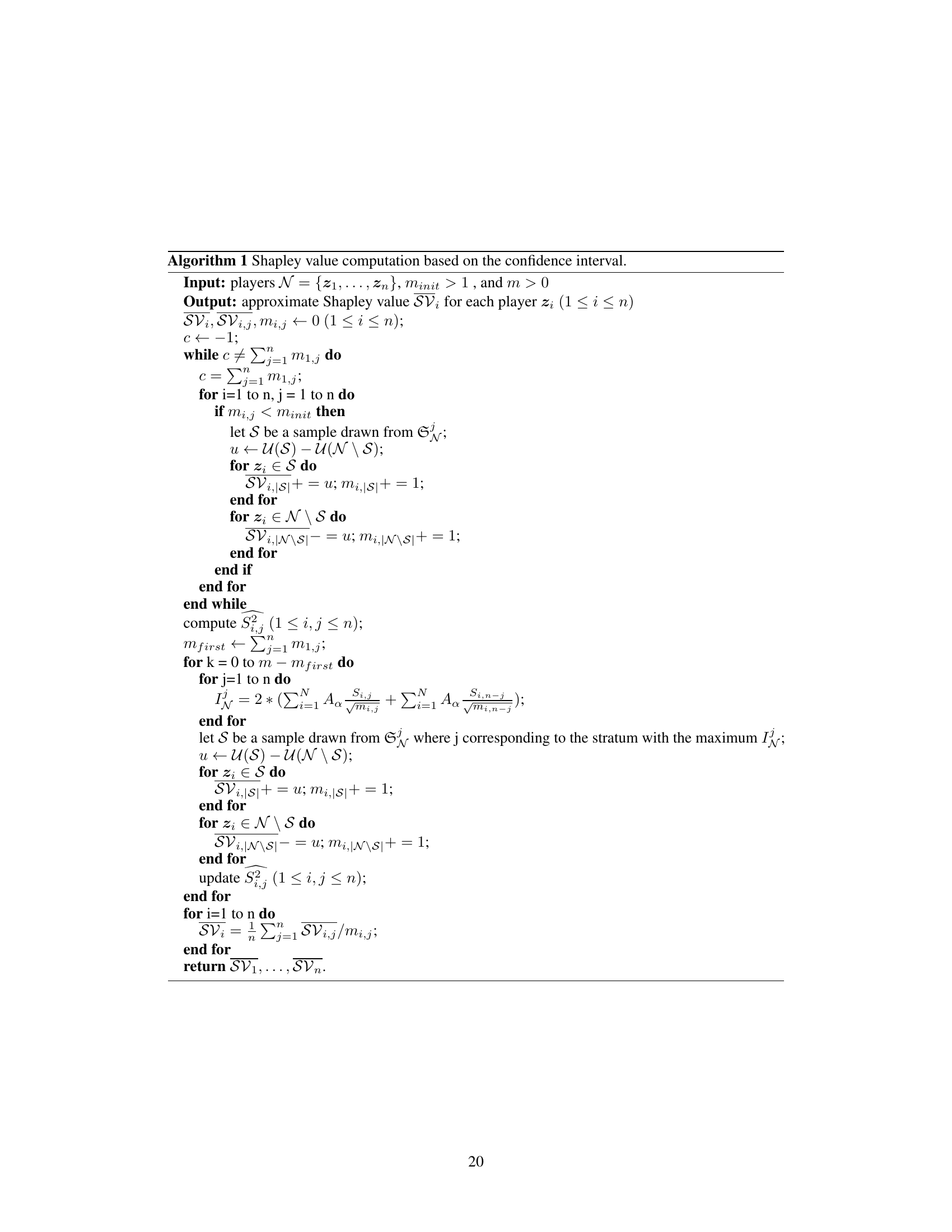

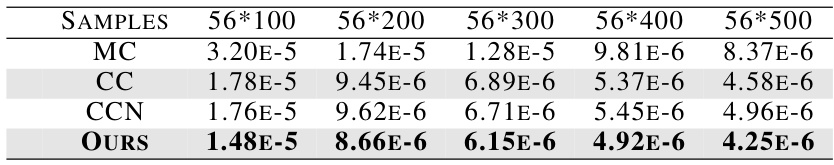

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of Shapley value estimations using different approximation methods (MC, CC, CCN, and OURS) with varying numbers of samples (56100, 56200, 56300, 56400, 56*500). The MSE is calculated against a benchmark obtained from extensive sampling using the CC method. Lower MSE values indicate better estimation accuracy. The table shows that the proposed method (OURS) consistently achieves the lowest MSE values across different sample sizes, indicating improved efficiency and accuracy compared to the baseline methods.

Full paper#