TL;DR#

Estimating Conditional Average Treatment Effects (CATE) is crucial for personalized decision-making but challenging due to the unavailability of counterfactual outcomes and the numerous CATE estimators. Existing selection methods (plug-in and pseudo-outcome metrics) require fitting models for nuisance parameters and lack focus on robustness. This creates difficulties in selecting the best estimator for a given task.

This paper introduces a Distributionally Robust Metric (DRM) for selecting CATE estimators. DRM is nuisance-free, meaning it doesn’t require fitting those complex models, significantly simplifying the process. The method prioritizes the selection of distributionally robust estimators, those less affected by data distribution shifts. Experiments show DRM effectively selects robust CATE estimators, demonstrating its practicality and value in improving the reliability of causal inference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with causal inference and personalized decision-making. It directly addresses the significant challenge of CATE estimator selection, offering a novel, robust method that is nuisance-free and distributionally robust. This work is highly relevant to current trends in causal machine learning and opens up new avenues for developing more reliable and effective causal inference methods.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure presents a stacked bar chart visualizing the distribution of selected estimator ranks across different ranking intervals ([1-3], [4-11], [12-19], [20-27], [28-36]) for each evaluation metric. The color intensity represents the frequency of a given rank within the interval. Darker green indicates higher ranking (among the best 3), while darker red signifies lower ranking (among the worst 9). This allows for a visual comparison of how frequently different selectors choose estimators of varying quality, assessing their robustness and ranking accuracy across various experimental settings.

read the caption

Figure 1: The stacked bar chart showing the distribution of the selected estimator's rank for each evaluation metric across rank intervals: [1-3], [4-11], [12-19], [20-27], and [28-36]. The greener (or redder) color indicates that the selected estimator ranks higher (or lower). For example, the dark red (or green) indicates the percentage of cases (out of 100 experiments) where the selected estimator ranks among the worst 9 estimators, specifically as ranks 28, 29, ..., or 36 (or among the best 3 estimators, specifically as ranks 1, 2, or 3).

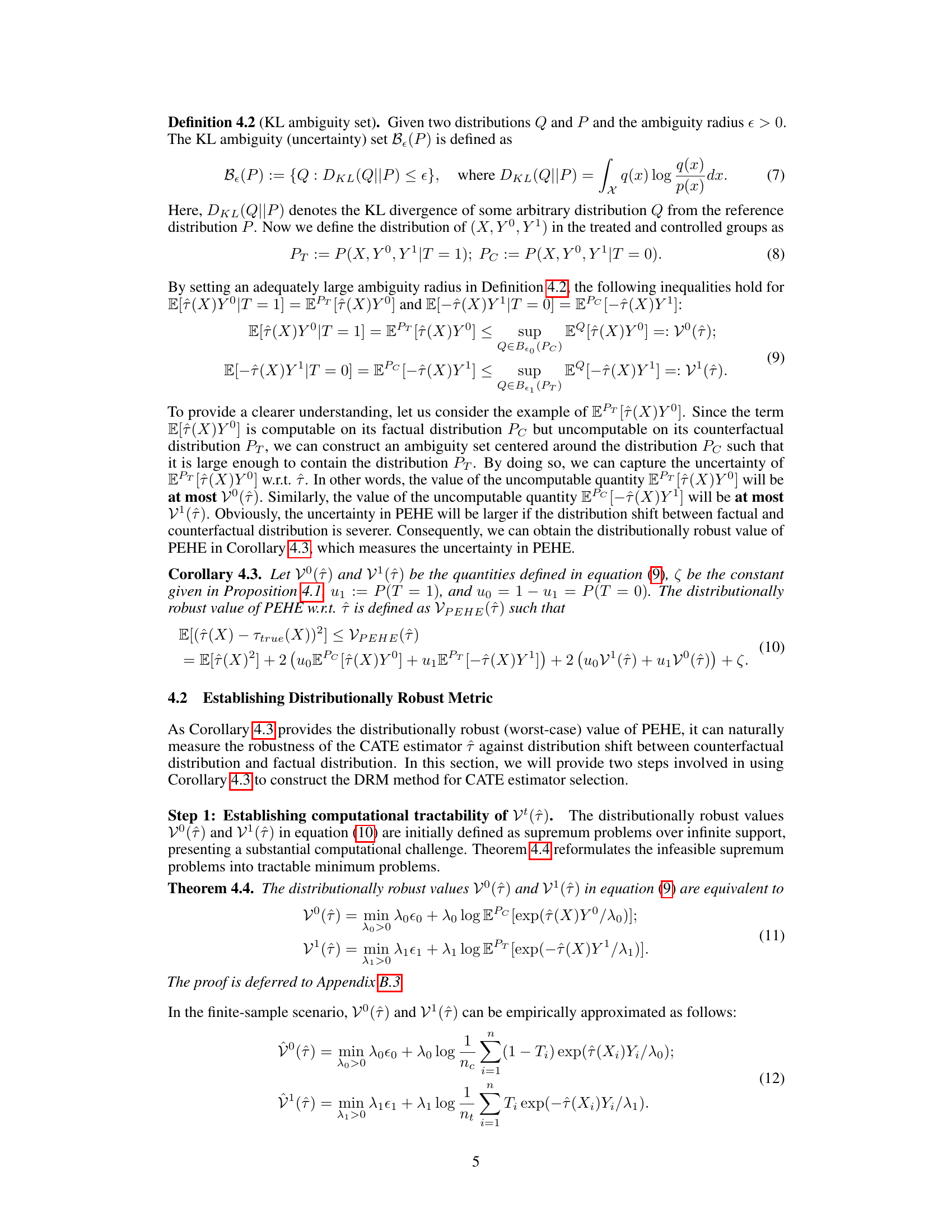

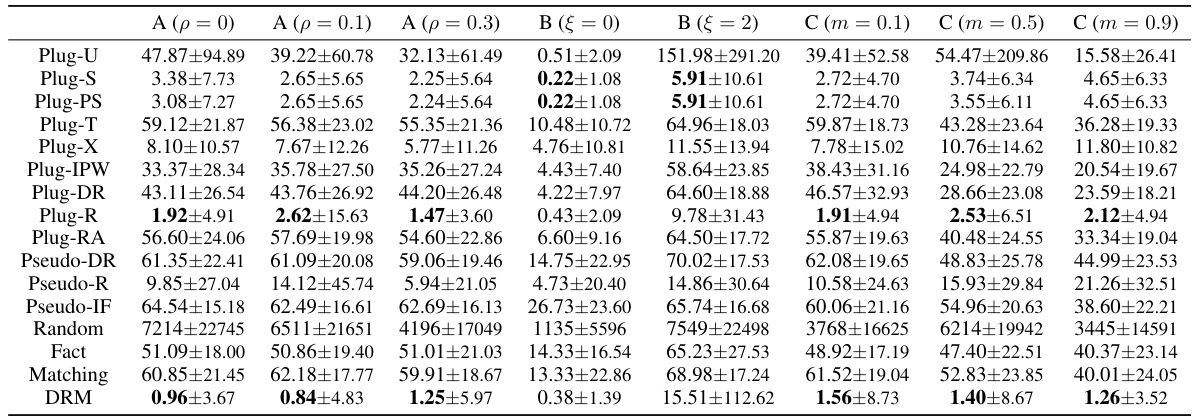

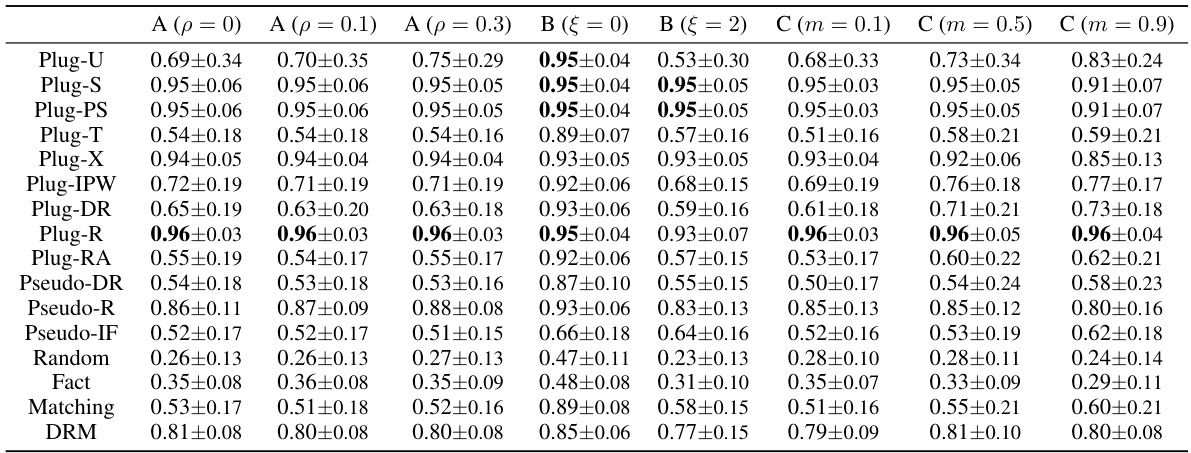

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the regret values for various CATE (Conditional Average Treatment Effect) estimator selection methods across three different settings (A, B, and C). Setting A varies the complexity of the CATE function, setting B introduces selection bias, and setting C simulates hidden confounders. For each setting, the table shows the mean and standard deviation of the regret, calculated over 100 experiments for each method. The best three performing methods for each setting are highlighted in bold. Smaller regret values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Regret for different selectors across Settings A, B, and C (Note that B (ξ = 1) matches A (p = 0.1)). Reported values (mean ± standard deviation) are computed over 100 experiments. Bold denotes the best three results among all selectors. Smaller value is better.

In-depth insights#

Robust CATE Choice#

The concept of ‘Robust CATE Choice’ centers on selecting a Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE) estimator that performs well even when faced with data imperfections or distributional shifts. Standard model selection methods often fail in causal inference due to the lack of counterfactual data. Therefore, a robust method should prioritize estimators that are less sensitive to variations in the data generating process. This robustness is particularly crucial when dealing with covariate shifts (differences in the distribution of covariates between treated and control groups) and hidden confounders (unobserved variables influencing both treatment and outcome). A robust CATE estimator would yield reliable results despite these challenges, contributing to more reliable personalized decision-making.

DRM for CATE#

The concept of “DRM for CATE” suggests a method using Distributionally Robust Metrics for selecting Conditional Average Treatment Effect estimators. This approach is innovative because traditional methods struggle with the lack of counterfactual data inherent in observational studies. The DRM method likely addresses this by focusing on the robustness of estimators to distributional shifts, making it less sensitive to model misspecification and covariate shifts, thus improving the reliability of CATE estimation. The key advantage is its nuisance-free nature, eliminating the need to model nuisance parameters which simplifies the process and reduces potential bias. This offers a significant advancement over previous approaches and could be especially valuable for personalized decision making where accurate CATE estimates are crucial. However, practical considerations such as setting the ambiguity radius for optimal performance and potential limitations in handling complex treatment effects warrant further investigation.

CATE Estimator Selection#

Selecting the optimal Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE) estimator is crucial for accurate causal inference. Traditional model validation is unsuitable due to the lack of counterfactual data. Existing methods, such as plug-in and pseudo-outcome metrics, suffer from limitations in determining metric forms and the need to fit nuisance parameters. Furthermore, they lack a specific focus on robustness. A key challenge is that CATE estimators often struggle with distribution shifts, stemming from covariate shifts or unobserved confounders. Robustness to such shifts should be a primary concern. Therefore, innovative approaches that prioritize selecting distributionally robust CATE estimators, potentially through techniques like distributionally robust metrics (DRM) which are nuisance-free, are highly desirable. This is because nuisance-free methods simplify the selection process and directly address the critical need for robustness in real-world applications. Furthermore, thorough evaluation of proposed methods should include examination of their performance in scenarios with various complexities of CATE functions and degrees of confounding to ensure generalizability and practical applicability.

Distributional Robustness#

Distributional robustness examines a model’s performance consistency across various data distributions. It’s crucial for real-world applications where the training data may not perfectly represent the future or unseen data. A robust model will maintain accuracy even with distribution shifts. This contrasts with standard methods focused on optimizing average performance, which can be misleading if the distribution changes. Techniques like distributionally robust optimization (DRO) aim to minimize worst-case performance across a set of possible distributions. This approach is valuable when dealing with uncertainty or adversarial scenarios. The tradeoff is between robustness and average performance. A highly robust model might sacrifice some average-case accuracy to ensure reliable behavior in the face of unexpected variations. The selection of a robust model often depends on the specific application, balancing the need for strong average-case performance with the risk of significant performance degradation under distribution shifts. Evaluating distributional robustness requires careful consideration of both theoretical guarantees and empirical validation across different datasets and scenarios.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several avenues. Improving the DRM’s ranking ability is crucial; while robust in selection, its ranking performance could benefit from refinement to better align with expected average performance. Investigating the effects of increased sample sizes and more complex CATE functions on the DRM’s performance is important to assess its generalizability. Furthermore, exploring the use of alternative divergence measures beyond KL-divergence, such as Wasserstein distance, could enhance the model’s robustness and allow for a wider range of counterfactual distribution considerations. Finally, a comparative analysis incorporating baselines specifically designed to handle hidden confounders, along with applying the DRM to real-world datasets in fields such as healthcare and economics, would significantly strengthen the overall impact and applicability of this research.

More visual insights#

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the Spearman rank correlation results for various CATE (Conditional Average Treatment Effect) estimator selection methods across three different experimental settings (A, B, and C). Setting A varies the complexity of the CATE function, setting B varies the level of selection bias, and setting C introduces hidden confounders. The rank correlation is a measure of how well each selector’s ranking of estimators aligns with the ranking based on the true, unobservable CATE values (oracle ranking). Higher values indicate better agreement with the oracle ranking, suggesting the method better identifies high-performing CATE estimators.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of rank correlation for different selectors across Settings A, B, and C (Note that B (ξ = 1) matches A (p = 0.1)). Bold denotes the best three results among all selectors. Reported values (mean ± standard deviation) are computed over 100 experiments. Larger is better.

🔼 This table presents the comparison of regret for various CATE (Conditional Average Treatment Effect) estimator selection methods across three different settings. Regret is calculated as the difference between the oracle risk (optimal estimator) and the risk of the selected estimator. The settings vary the level of selection bias and the complexity of the CATE function to evaluate the robustness of different selectors. Smaller regret values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Regret for different selectors across Settings A, B, and C (Note that B (ξ = 1) matches A (p = 0.1)). Reported values (mean ± standard deviation) are computed over 100 experiments. Bold denotes the best three results among all selectors. Smaller value is better.

Full paper#