↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) sometimes produce unreliable outputs, known as hallucinations. These hallucinations stem from two types of uncertainty: epistemic uncertainty (lack of knowledge) and aleatoric uncertainty (irreducible randomness). Current methods struggle to differentiate between these, especially in situations with multiple correct answers. This makes it difficult to reliably identify and flag unreliable outputs.

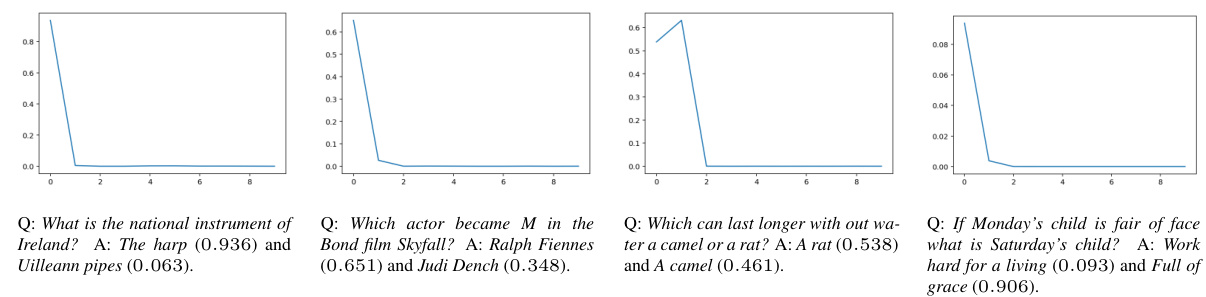

This research proposes a new approach using iterative prompting to quantify uncertainty. By repeatedly asking the LLM the same question, incorporating previous responses into the prompt, the researchers developed a way to measure how much the LLM’s response changes based on the context. A new information-theoretic metric is then used to quantify the distance between this iterative LLM-generated distribution and the expected ground truth distribution. Results show their approach outperforms existing methods, especially when dealing with multiple correct answers, offering a valuable tool for enhancing LLM reliability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large language models (LLMs) and uncertainty quantification. It offers a novel approach to identify hallucination in LLMs by decoupling epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty, which is a significant advancement in the field. The proposed method uses iterative prompting and an information-theoretic metric, providing a robust and practical solution for detecting unreliable LLM outputs. This work opens up new avenues for improving LLM reliability and trustworthiness, leading to more reliable and trustworthy AI systems.

Visual Insights#

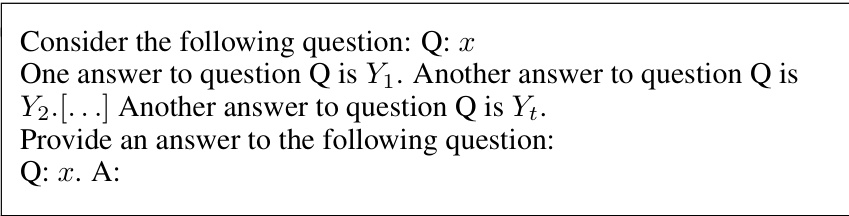

This figure shows the results of an experiment where the model is given a single-label query with low epistemic uncertainty. The model is then prompted with the correct answer and multiple repetitions of an incorrect answer. The normalized probability of the correct response is plotted against the number of repetitions of the incorrect answer. The results demonstrate that even with many repetitions of the incorrect answer, the probability of the correct response remains relatively high, indicating low epistemic uncertainty. Each subplot represents a different query.

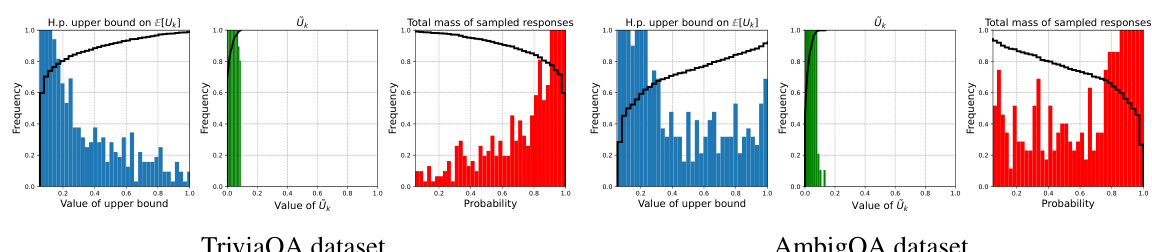

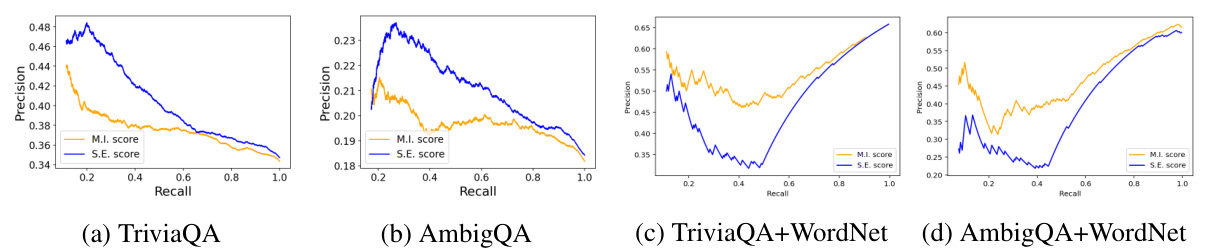

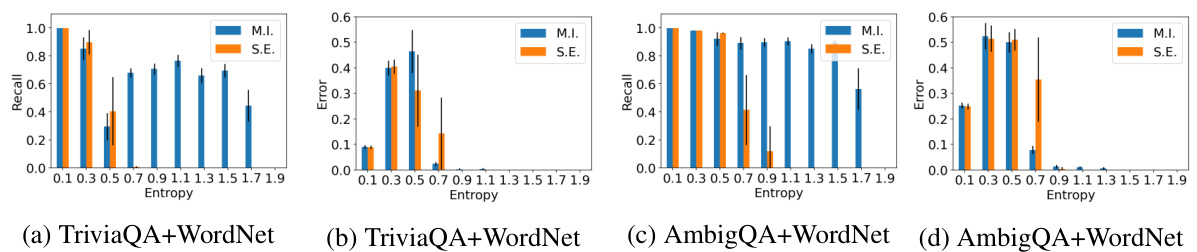

This figure compares several methods for detecting hallucination in LLMs. It shows precision-recall curves for four different methods on four different datasets. The datasets vary in the proportion of single-label vs. multi-label queries. The methods compared are: greedy response probability (T0), semantic entropy (S.E.), the proposed mutual information (M.I.), and self-verification (S.V.). The results show that M.I. and S.E. perform similarly on datasets with primarily single-label queries but that M.I. outperforms S.E. on datasets with a significant number of multi-label queries.

In-depth insights#

Epistemic Uncertainty#

Epistemic uncertainty, a core concept in the research paper, focuses on the lack of knowledge about the ground truth. It’s contrasted with aleatoric uncertainty, which stems from irreducible randomness. The paper investigates how to reliably detect when only epistemic uncertainty is high, indicating unreliable model outputs, potentially hallucinations. This detection isn’t straightforward, particularly in multi-answer scenarios, where standard methods often fail. The authors propose iterative prompting as a key technique. By repeatedly prompting the model, they identify situations where responses are heavily influenced by prior answers, a sign of high epistemic uncertainty. This innovative approach offers a novel solution to a crucial problem in large language model reliability, enabling more effective uncertainty quantification and, ultimately, improved trust in AI outputs.

Iterative Prompting#

The core idea revolves around iteratively prompting large language models (LLMs) to better understand and quantify their uncertainty, especially epistemic uncertainty (knowledge gaps). Instead of a single query, iterative prompting involves a sequence of prompts, each building upon the previous LLM response. This approach helps disentangle aleatoric uncertainty (inherent randomness) from epistemic uncertainty. By analyzing how the LLM’s responses change with each iteration, researchers can gauge the model’s confidence. A key observation is that if the model’s responses become insensitive to previous answers, it indicates high epistemic uncertainty, potentially suggesting hallucinations or unreliable outputs. Conversely, consistent responses suggest low epistemic uncertainty and greater reliability. This technique provides a novel method for identifying when LLMs are exhibiting high epistemic uncertainty, surpassing the limitations of traditional uncertainty quantification methods that struggle with multi-response scenarios or hallucination detection. The information-theoretic metric derived from this process offers a robust and quantifiable measure for assessing epistemic uncertainty in LLMs.

Hallucination Detection#

The research paper delves into the crucial problem of hallucination detection in large language models (LLMs). Hallucinations, or the generation of factually incorrect or nonsensical outputs, pose a significant challenge to the trustworthiness and reliability of LLMs. The paper proposes a novel approach that focuses on quantifying epistemic uncertainty, which represents the model’s lack of knowledge about the ground truth, as opposed to aleatoric uncertainty (irreducible randomness). This is achieved through iterative prompting, where the model is repeatedly prompted with its previous responses, allowing the detection of inconsistencies and amplification of epistemic uncertainty. A key contribution is the derivation of an information-theoretic metric based on the mutual information between multiple responses, enabling a more reliable assessment of epistemic uncertainty and hallucination. Experiments across various datasets highlight the proposed method’s effectiveness in detecting hallucinations, particularly in scenarios with multiple valid responses. The research also offers mechanistic explanations for why iterative prompting amplifies epistemic uncertainty within the context of transformer architectures. The paper advances the understanding and detection of LLMs’ hallucinations by providing a principled, information-theoretic approach that directly addresses the limitations of existing techniques.

MI-based Approach#

The core idea revolves around using mutual information (MI) as a metric to quantify epistemic uncertainty in large language models (LLMs). The MI-based approach cleverly leverages iterative prompting, generating multiple responses to the same query. By analyzing the dependencies between these responses, the method aims to distinguish between aleatoric uncertainty (inherent randomness) and epistemic uncertainty (lack of knowledge). A key strength lies in its ability to handle multi-response queries, unlike many traditional methods that struggle with scenarios where multiple answers are valid. The approach proposes a finite-sample estimator for MI, accounting for the potential infinity of possible LLM outputs. This estimator is shown to provide a computable lower bound on epistemic uncertainty, making it practical for applications like hallucination detection. The effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments comparing this MI-based approach to existing baselines on various question-answering benchmarks, often showing superior performance, especially in datasets with a mix of single and multi-label queries, proving its robustness and utility in real-world applications.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the iterative prompting framework to encompass more complex reasoning tasks and diverse LLM architectures is crucial. Investigating the influence of various prompt engineering techniques on the accuracy of epistemic uncertainty estimation would yield valuable insights. Furthermore, a deeper dive into the underlying mechanisms of LLMs, particularly how iterative prompting affects internal representations and attention weights, is needed to better understand the observed phenomena. Developing more robust and reliable metrics for quantifying both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty in LLMs remains a key challenge. Finally, applying these findings to practical applications such as improved hallucination detection and trustworthy AI systems should be a priority. The work on iterative prompting and epistemic uncertainty presents a solid foundation for future advancements in the field of trustworthy and reliable large language models.

More visual insights#

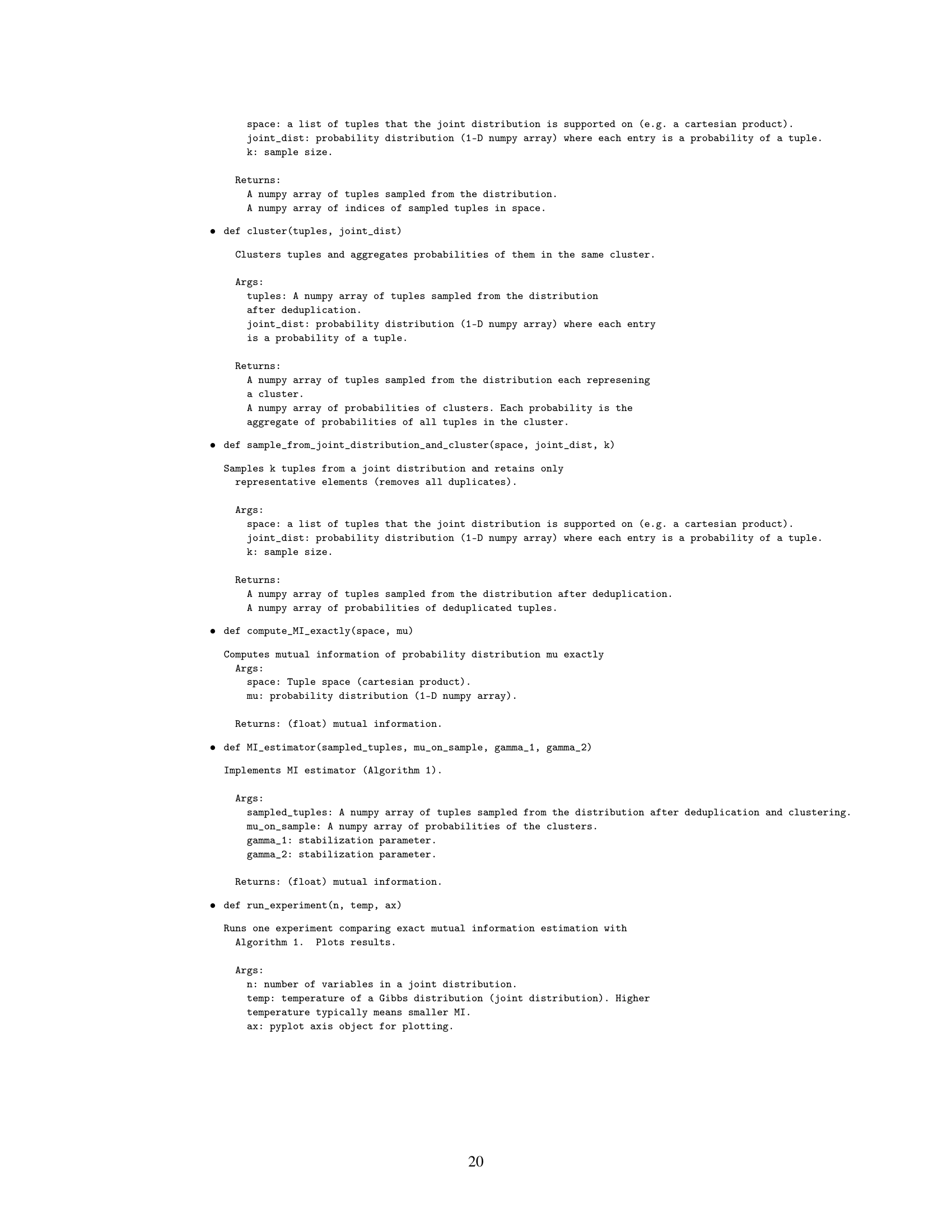

More on figures

This figure displays four examples of single-label queries where the language model exhibits high epistemic uncertainty. The graphs show how the normalized probability of the correct answer changes as an incorrect response is repeatedly added to the prompt. In each case, the correct answer’s probability significantly decreases as the incorrect response is repeated, indicating a lack of robust knowledge from the model.

This figure shows four examples of multi-label queries with high aleatoric uncertainty. The normalized probability of the first (correct) response is plotted against the number of repetitions of the second (also correct) response in the prompt. The results demonstrate that even when multiple correct answers exist, the probability of a correct answer does not collapse to zero as the incorrect answer is repeated in the prompt. This contrasts with the behavior observed in single-label queries with high epistemic uncertainty, where the probability of the correct answer decreases significantly as the incorrect answer is repeated.

This figure displays the results of an experiment on single-label queries with low epistemic uncertainty. The normalized probability of the correct answer is shown, given varying numbers of repetitions of an incorrect answer in the prompt. Each subplot represents a different query, showing the initial probabilities of the correct and incorrect answers. The x-axis represents the number of repetitions of the incorrect answer, and the y-axis represents the normalized probability of the correct answer. The low drop in probability of the correct response even with many repetitions of the incorrect response highlights that the model has low epistemic uncertainty regarding these queries.

This figure presents the precision-recall curves for four different methods used for hallucination detection on four different datasets. The methods are compared based on their precision and recall in detecting hallucinated responses. The datasets used are TriviaQA, AmbigQA, TriviaQA+WordNet, and AmbigQA+WordNet. The results show that the proposed mutual information (MI) method performs comparably to the semantic entropy (S.E.) method on single-label datasets (TriviaQA and AmbigQA), but significantly outperforms it on multi-label datasets (TriviaQA+WordNet and AmbigQA+WordNet). The difference in performance is more pronounced when the recall is high.

This figure displays precision-recall curves for four different methods used to detect hallucination in language models. The methods are compared on four different datasets: TriviaQA, AmbigQA, TriviaQA+WordNet, and AmbigQA+WordNet. The TriviaQA and AmbigQA datasets consist primarily of single-label queries, while the TriviaQA+WordNet and AmbigQA+WordNet datasets contain a mix of single-label and multi-label queries. The results show that the mutual information (MI) and semantic entropy (SE) methods perform similarly well on the datasets with mainly single-label queries, significantly outperforming the baseline methods. However, on datasets containing a substantial proportion of multi-label queries, the MI method surpasses the SE method.

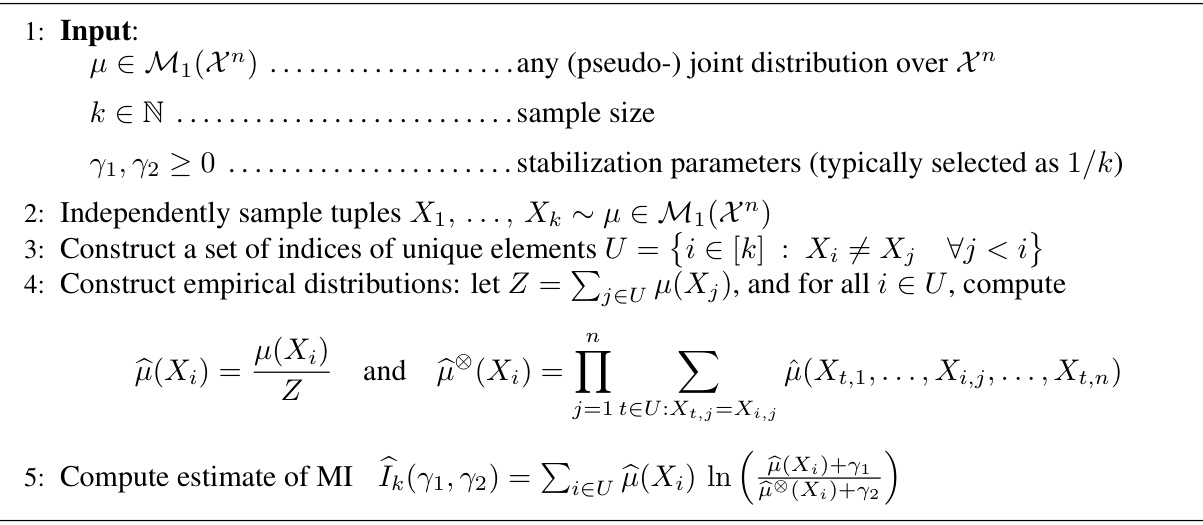

This figure shows the empirical distributions of three different quantities related to the missing mass for TriviaQA and AmbigQA datasets. The leftmost plot displays the distribution of upper bounds on the expected missing mass E[Uk]. The central plot shows the distribution of the missing mass Ūk, computed using a finite support approximation of the LLM’s output. Finally, the rightmost plot displays the distribution of the cumulative probabilities of all responses generated by the LLM.

This figure compares the performance of different methods for detecting hallucination in LLMs across four datasets: TriviaQA, AmbigQA, TriviaQA+WordNet, and AmbigQA+WordNet. The plots show precision-recall curves, where precision represents the accuracy of the hallucination detection, and recall represents the percentage of queries correctly identified as hallucinations. The results indicate that the mutual information (MI) based method performs similarly to the semantic entropy (SE) method on datasets with mostly single-label queries but outperforms it significantly on datasets with a higher proportion of multi-label queries, highlighting the MI-based method’s advantage in handling multiple valid answers.

This figure presents the Precision-Recall (PR) curves for four different methods used for hallucination detection in LLMs: the proposed mutual information (M.I.) method, semantic entropy (S.E.), greedy response probability (T0), and self-verification (S.V.). The results are shown for four datasets: TriviaQA, AmbigQA, TriviaQA+WordNet (TriviaQA combined with WordNet data), and AmbigQA+WordNet (AmbigQA combined with WordNet data). The graphs show that the M.I. and S.E. methods generally outperform T0 and S.V., particularly on datasets with high entropy multi-label queries. The near-identical performance of M.I. and S.E. on the TriviaQA and AmbigQA datasets is explained by the fact that responses to many queries cluster closely, resulting in similar entropy and mutual information scores.

Full paper#