↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research uses powerful generative models to decode images and text from brain activity, aiming to improve the reconstruction of these stimuli. However, this improved fidelity could stem from multiple factors, such as better understanding the distribution of stimuli, enhancing image and text reconstruction capabilities, or simply exploiting weaknesses in evaluation metrics. This makes it hard to know if these improvements stem from actually decoding more of the brain or other factors.

To address these issues, the researchers introduce BrainBits, a new method utilizing an information bottleneck. By varying the amount of neural recording information used, they evaluated the reconstruction fidelity. BrainBits indicates that state-of-the-art reconstruction methods surprisingly achieve high-fidelity results with minimal neural data, underscoring the significant role of generative models’ prior knowledge. This finding implies that improving reconstruction fidelity might not directly translate to improved understanding of brain processing and suggests a need for more comprehensive evaluation metrics in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common assumption that higher-fidelity brain-based reconstructions directly imply a deeper understanding of the brain. By introducing a novel bottleneck method, it reveals that state-of-the-art models often rely more on their prior knowledge than on the neural data itself, urging researchers to focus on improving the actual use of brain signals.

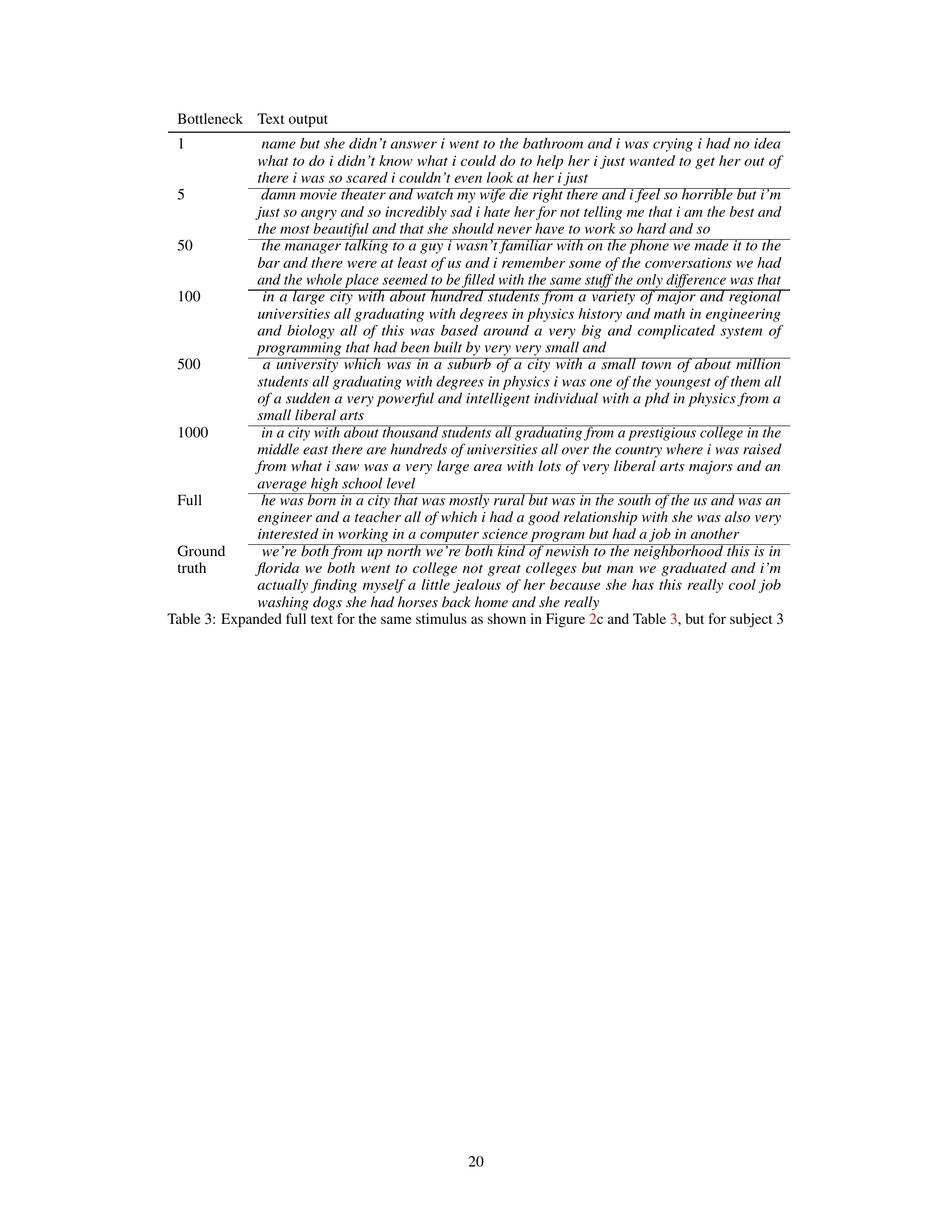

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the BrainBits framework applied to the BrainDiffuser model. It shows how brain signals are compressed through an adjustable information bottleneck (gL) into a lower-dimensional representation. This reduced representation, along with CLIP-text and CLIP-vision embeddings, is then used to predict VDVAE latents. Finally, these latents are fed into a Versatile Diffusion model to generate the reconstructed image. The size of the bottleneck (L) is varied to assess how much brain information is necessary for successful reconstruction. The goal is to understand how much of the reconstruction is due to information from the brain, versus reliance on the generative model’s prior knowledge.

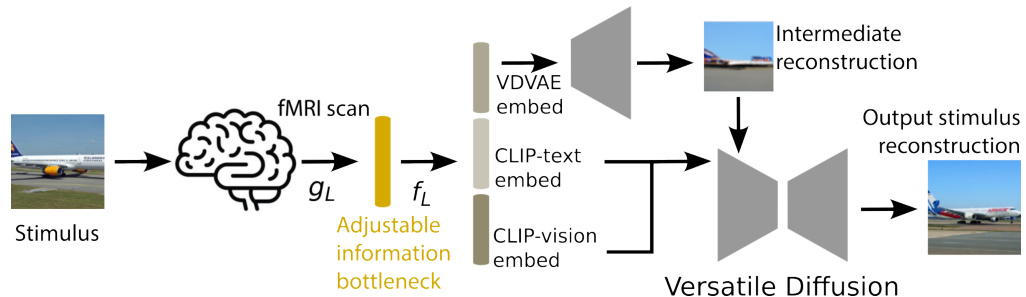

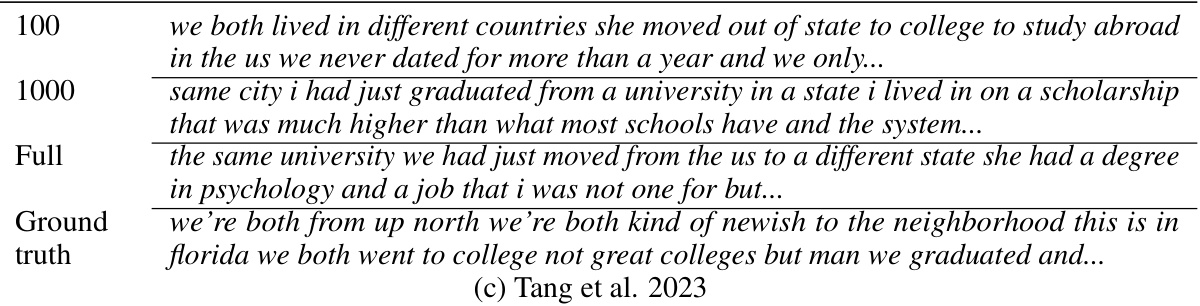

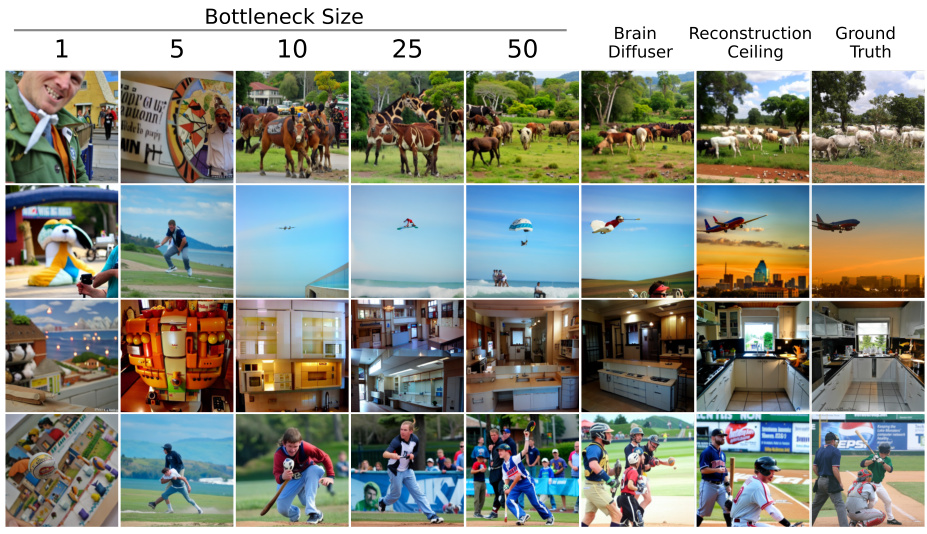

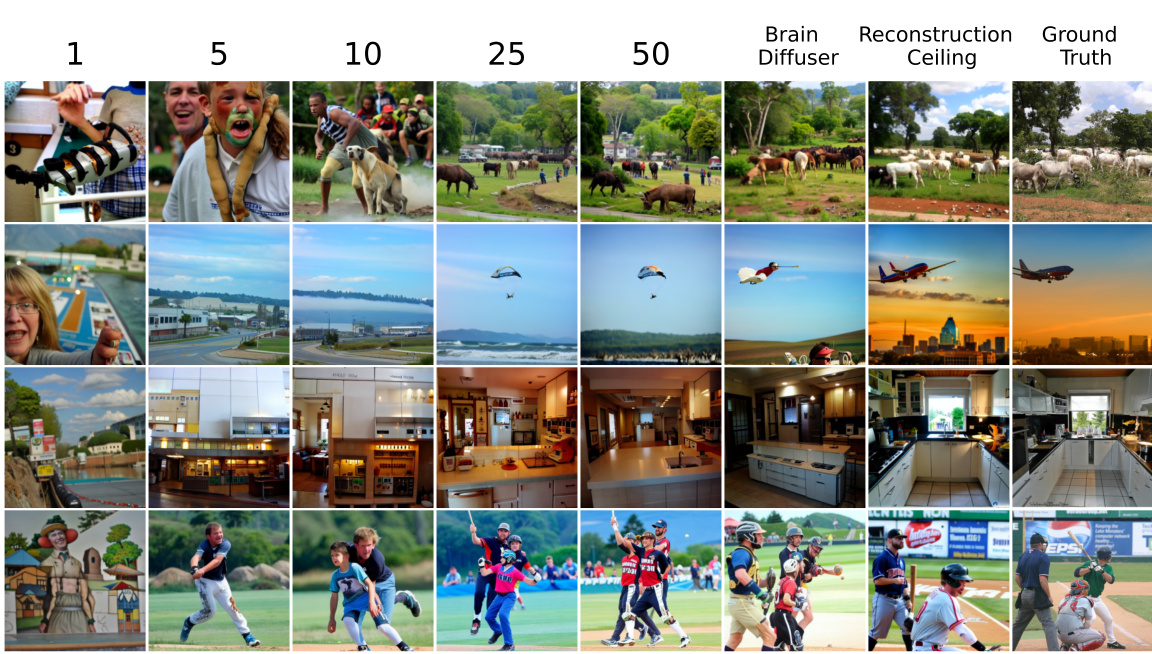

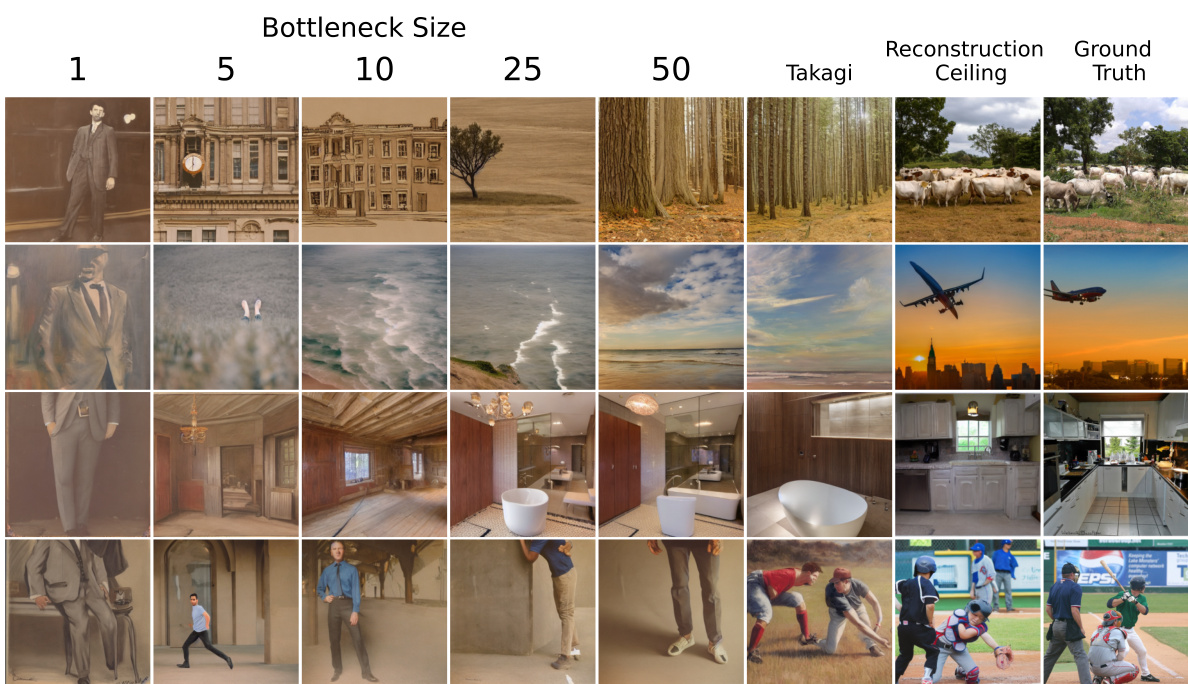

This figure shows examples of image and text reconstruction results from three different methods (BrainDiffuser, Takagi & Nishimoto 2023, and Tang et al. 2023) at different bottleneck sizes. It demonstrates that high-fidelity reconstructions can be achieved even with a small fraction of the available brain data, highlighting the power of the generative models’ priors.

In-depth insights#

Generative Model Priors#

Generative model priors play a crucial, often underestimated role in reconstructing stimuli from brain activity. These priors, learned from large datasets of images and text, act as powerful internal models, shaping the reconstruction even when limited neural data is available. The paper highlights that high-fidelity reconstructions don’t necessarily imply a deep understanding of brain processes, but rather might reflect the strength of the generative model’s prior. The reliance on priors can mask the actual amount of brain signal being used, leading to an overestimation of our understanding of neurobiological mechanisms. This emphasizes the need for careful evaluation metrics, accounting for the contribution of priors, and to focus on methods that demonstrably utilize more of the neural recordings. BrainBits, as proposed, offers a way to quantify this prior influence, and the performance curve generated as a function of the bottleneck size. This allows researchers to distinguish progress in signal extraction from advances in generative models, enabling a more accurate and nuanced assessment of actual neuroscientific progress. Ultimately, responsible reporting should include method-specific baselines and ceilings, facilitating a clearer view of how much brain information truly drives reconstruction accuracy.

BrainBits Bottleneck#

The concept of “BrainBits Bottleneck” presents a novel approach to evaluating generative models in neuroscience. It cleverly addresses the issue of overfitting and the inherent limitations of current evaluation metrics by introducing an information bottleneck. By systematically restricting the amount of neural data used as input to the generative model, BrainBits allows researchers to quantify how much of the reconstruction’s fidelity is actually attributable to the brain signal versus the model’s pre-existing priors. This methodology is crucial for disentangling true neuroscientific progress from improvements solely driven by increasingly powerful generative models. The use of a bottleneck enables the identification of a method-specific random baseline and reconstruction ceiling, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of model performance. The approach is further enhanced by its interpretability, allowing examination of which brain regions contribute most to reconstruction at varying bottleneck sizes. The study highlights the surprising finding that even small amounts of neural data are sufficient to drive high-fidelity reconstruction in many cases, suggesting the critical importance of focusing on improving the utilization of neural recordings rather than merely enhancing generative model capabilities.

Reconstruction Metrics#

Reconstruction metrics are crucial for evaluating the performance of brain-to-image/text generative models. However, standard metrics like SSIM, pixel correlation, or BLEU may not fully capture the nuances of reconstruction quality, especially when powerful generative priors are involved. A model might achieve high scores by leveraging its prior knowledge rather than effectively using neural data. Therefore, it’s vital to carefully consider the limitations of these standard metrics and introduce complementary evaluations, such as the BrainBits bottleneck analysis that quantifies the actual signal dependency. In addition, understanding the impact of the generative models’ prior and establishing meaningful baselines are essential for fair comparison and accurate interpretation of reconstruction success. Simply focusing on reducing reconstruction error might be misleading, potentially overlooking the importance of maximizing brain signal utilization and generating genuinely novel results beyond the model’s prior expectations. Future research needs more sophisticated and nuanced metrics to capture the quality of generative models’ outputs in the context of neural decoding.

Brain Region Analysis#

A hypothetical ‘Brain Region Analysis’ section in a neuroscience paper would likely explore the neural correlates of specific cognitive functions by examining patterns of brain activity across different regions. Advanced neuroimaging techniques like fMRI or EEG would be instrumental in identifying which brain areas show increased activation during various tasks. The analysis may involve comparing activation levels between experimental and control conditions to determine regions specifically involved in processing stimuli or performing specific actions. Statistical analysis would play a significant role, helping researchers determine the statistical significance of observed activation patterns and control for potential confounding variables. Sophisticated methods such as voxel-wise comparisons, region of interest (ROI) analysis, or graph theoretical approaches could be used to analyze the relationships between different brain regions, thus revealing the intricate network of communication necessary for complex cognitive functions. Finally, the findings would be interpreted in the context of existing neuroscientific literature, offering valuable insights into the specific roles of various brain areas in cognition.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more sophisticated bottleneck methods beyond simple linear transformations, potentially leveraging vector quantization or autoencoders to better capture the underlying structure of neural data. Investigating the impact of different neural recording modalities (EEG, ECoG) on bottleneck size and reconstruction fidelity would broaden the applicability of this framework. Furthermore, a deeper dive into interpretability is needed—understanding which specific features are encoded at different bottleneck sizes and how these features relate to cognitive processes is crucial. Finally, developing more robust evaluation metrics that account for generative model priors is essential for assessing the true contribution of brain signals to reconstruction accuracy. This will necessitate further research into quantitative measures that accurately reflect neural information extraction.

More visual insights#

More on figures

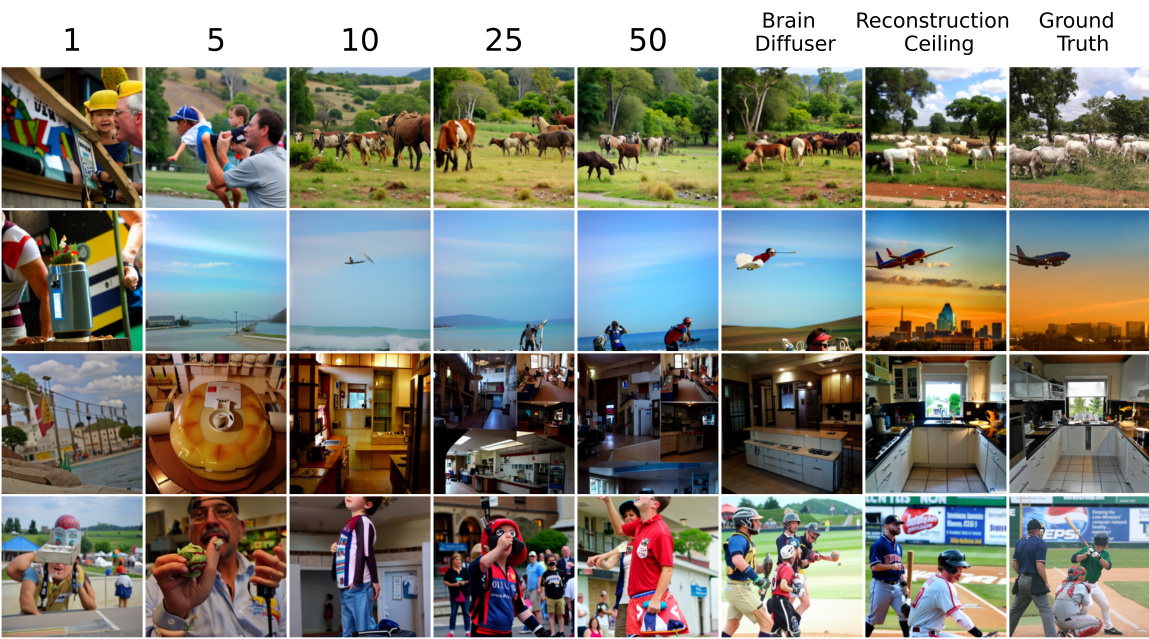

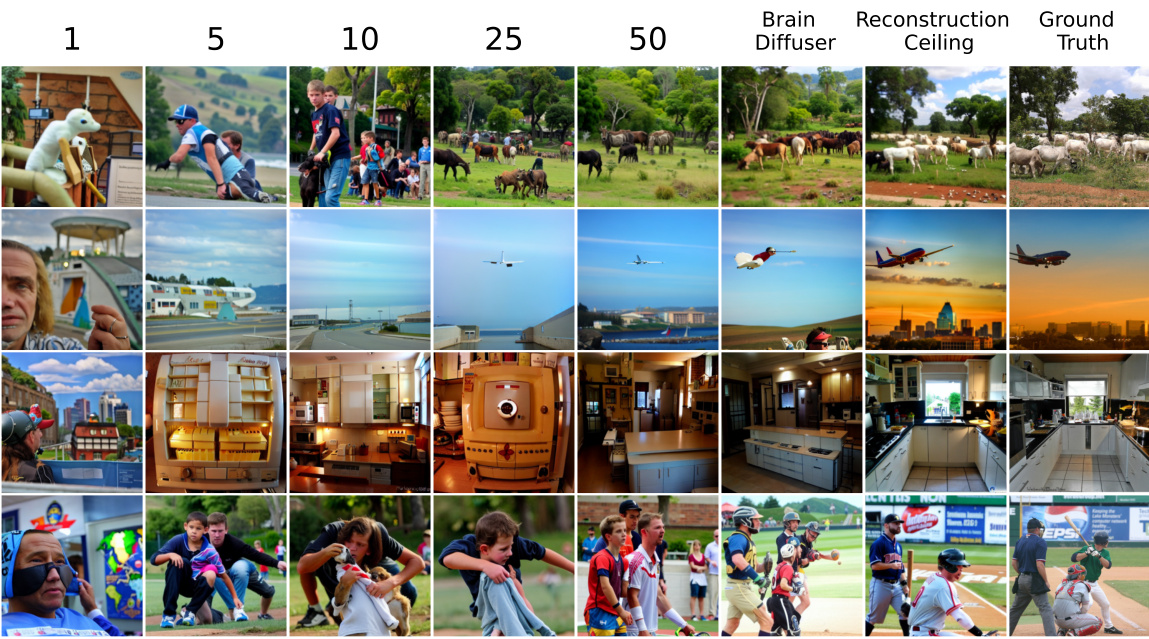

This figure shows the results of applying the BrainBits method to three different stimulus reconstruction methods: BrainDiffuser, Takagi & Nishimoto 2023, and Tang et al. 2023. It demonstrates that high-fidelity image and text reconstructions can be achieved even when using only a small fraction of the available neural data (bottleneck size). The figure visually compares reconstructions at different bottleneck sizes, highlighting that the quality of the reconstructions increases as more neural data is used, but even with a small fraction the reconstructions are surprisingly good, suggesting that model priors play a significant role.

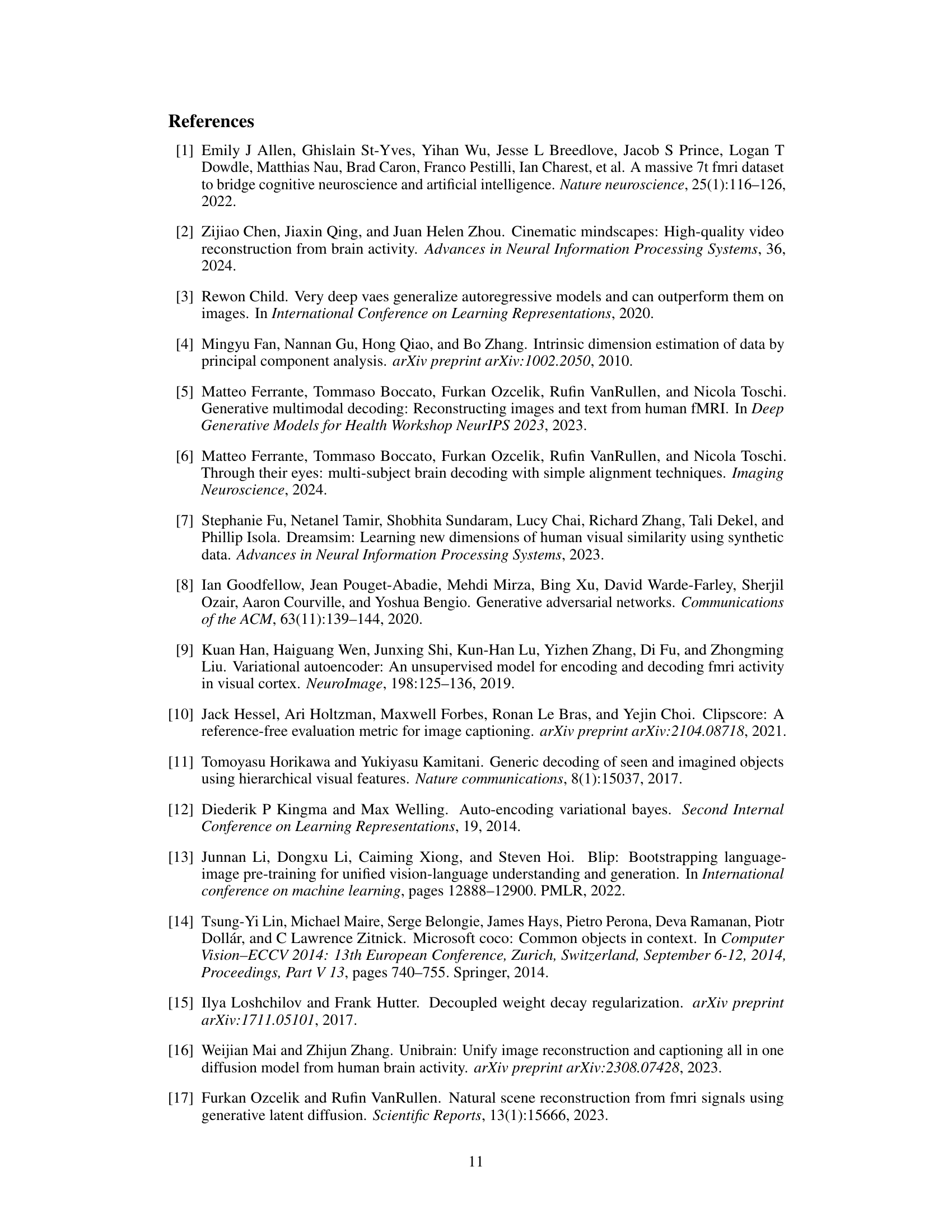

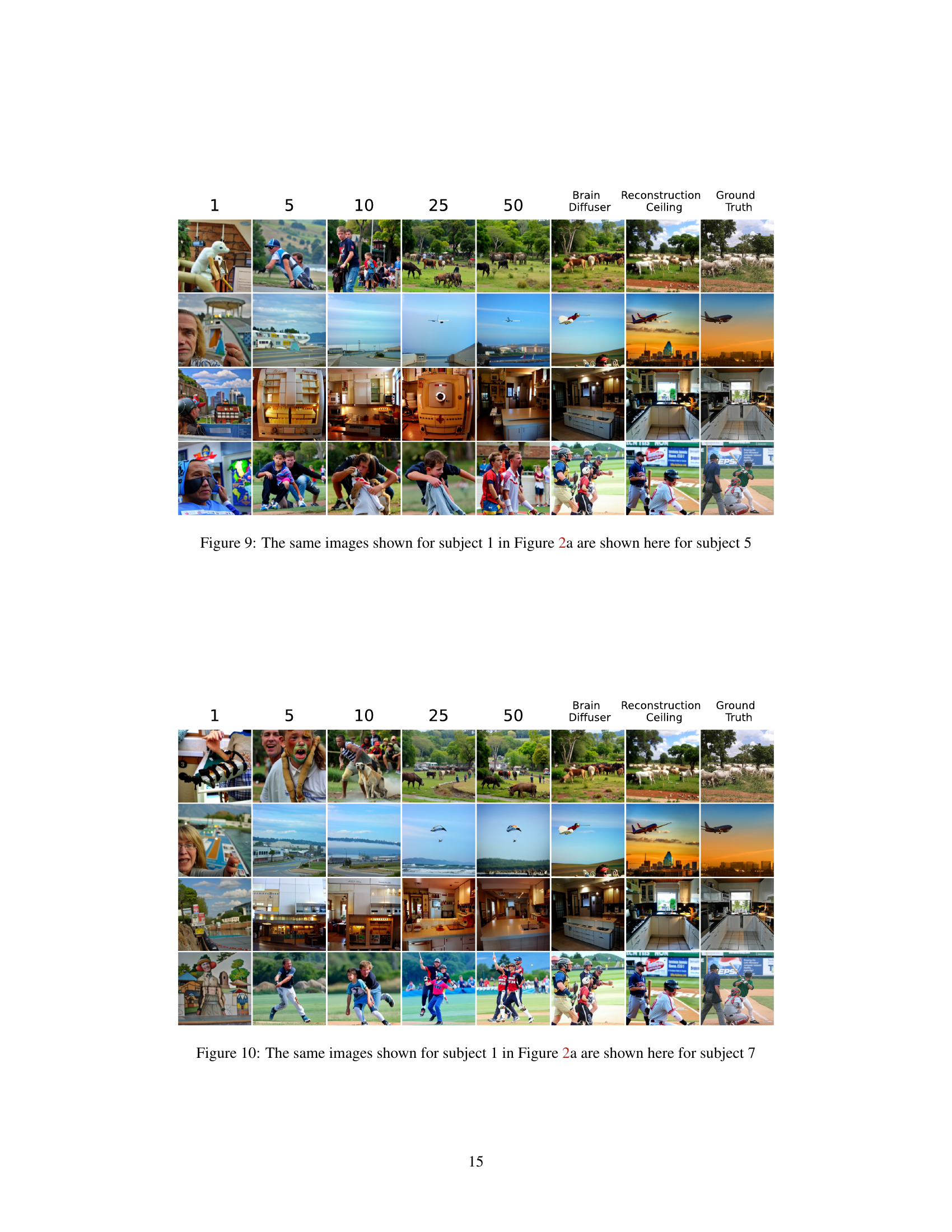

This figure demonstrates the application of the BrainBits method to Takagi & Nishimoto’s image reconstruction approach. It shows a grid of images reconstructed at various bottleneck sizes (1, 5, 10, 25, 50), comparing them to Takagi’s reconstruction ceiling (i.e., reconstruction if the model had perfect access to latent information) and the ground truth images. The goal is to visually illustrate how much of the image information can be accurately recovered even with a small amount of neural data, highlighting the role of generative model priors in these high-fidelity reconstructions.

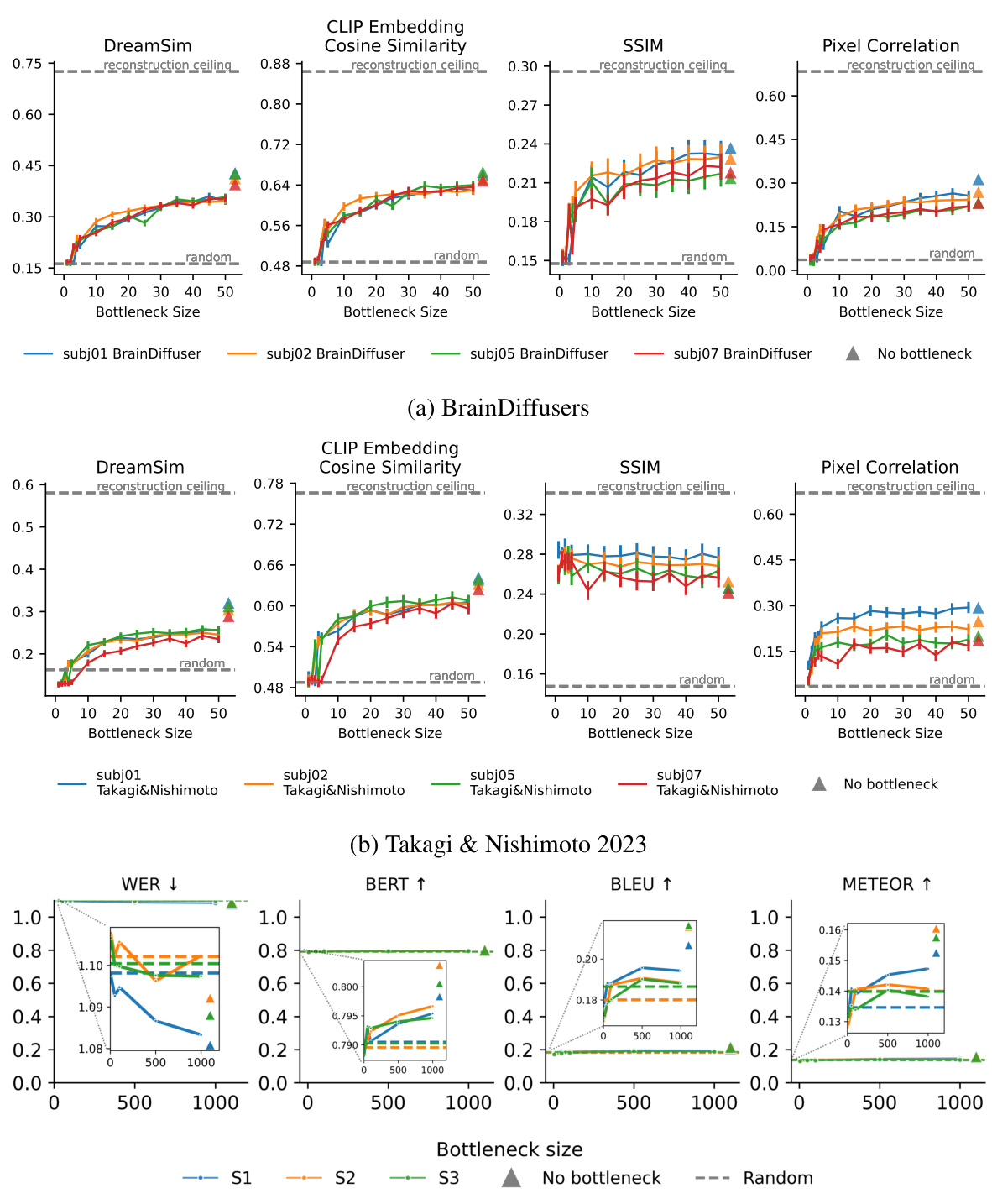

This figure quantitatively shows how the performance of three different reconstruction methods changes as the amount of brain data used is reduced. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small amount of neural data is sufficient for high-fidelity reconstruction, with performance reaching a plateau quickly. The figure uses different evaluation metrics for image (DreamSim, CLIP embedding cosine similarity, SSIM, and pixel correlation) and text (WER, BERT, BLEU, and METEOR) reconstruction. It highlights that vision reconstruction methods perform significantly better than language reconstruction methods, and that language methods rely more heavily on generative model priors than neural data.

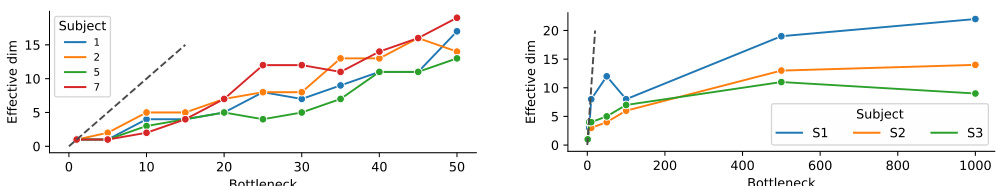

This figure shows two plots visualizing the effective dimensionality of bottlenecks for vision and language reconstruction methods. The left plot (BrainDiffuser) shows that the effective dimensionality closely follows the bottleneck size for vision, indicating that a substantial amount of information is used from the neural recordings. Conversely, the right plot (language) illustrates that for language tasks, the effective dimensionality remains low even with large bottlenecks, suggesting that only a small fraction of the neural signal is being used. The dashed lines in the plots indicate the expected dimensionality if all the dimensions were used effectively.

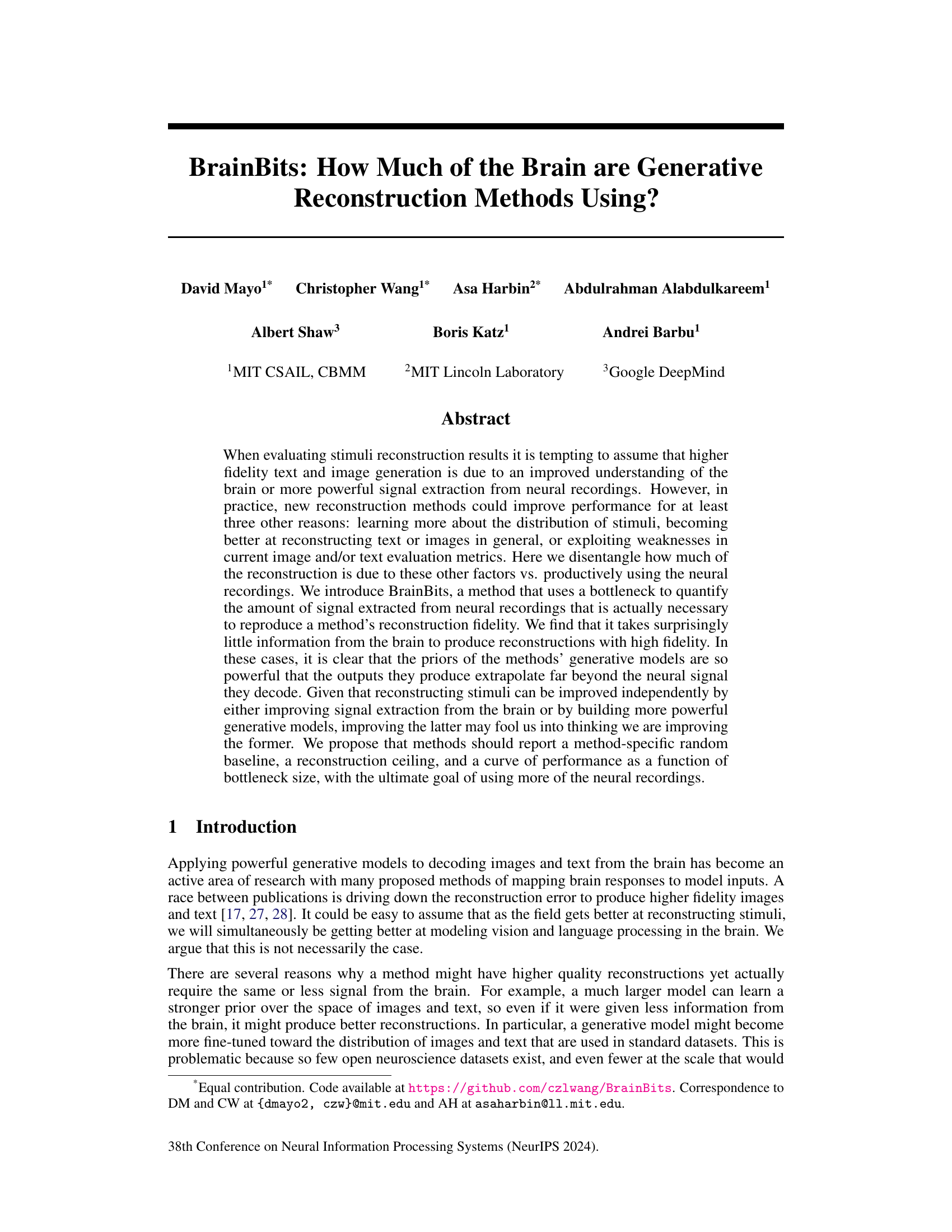

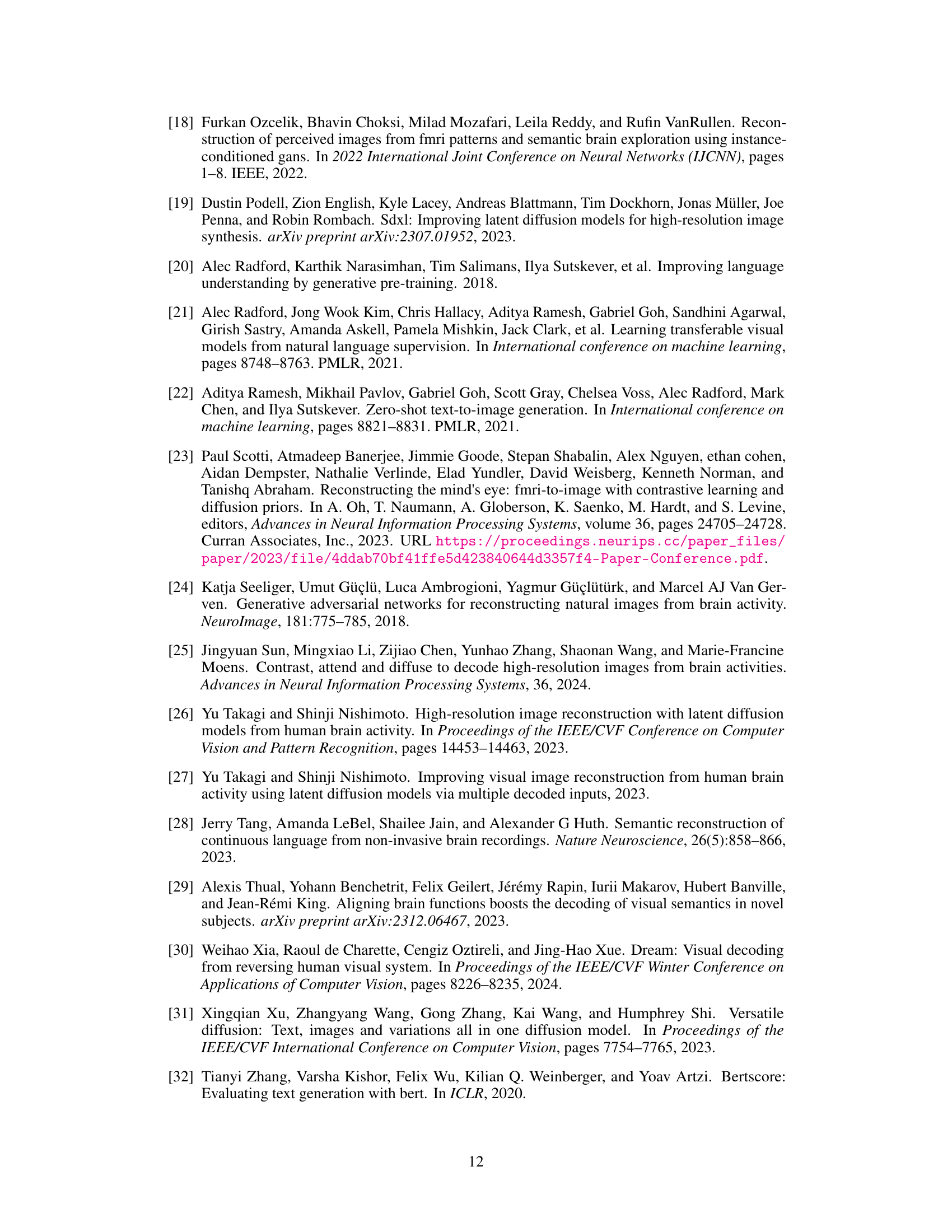

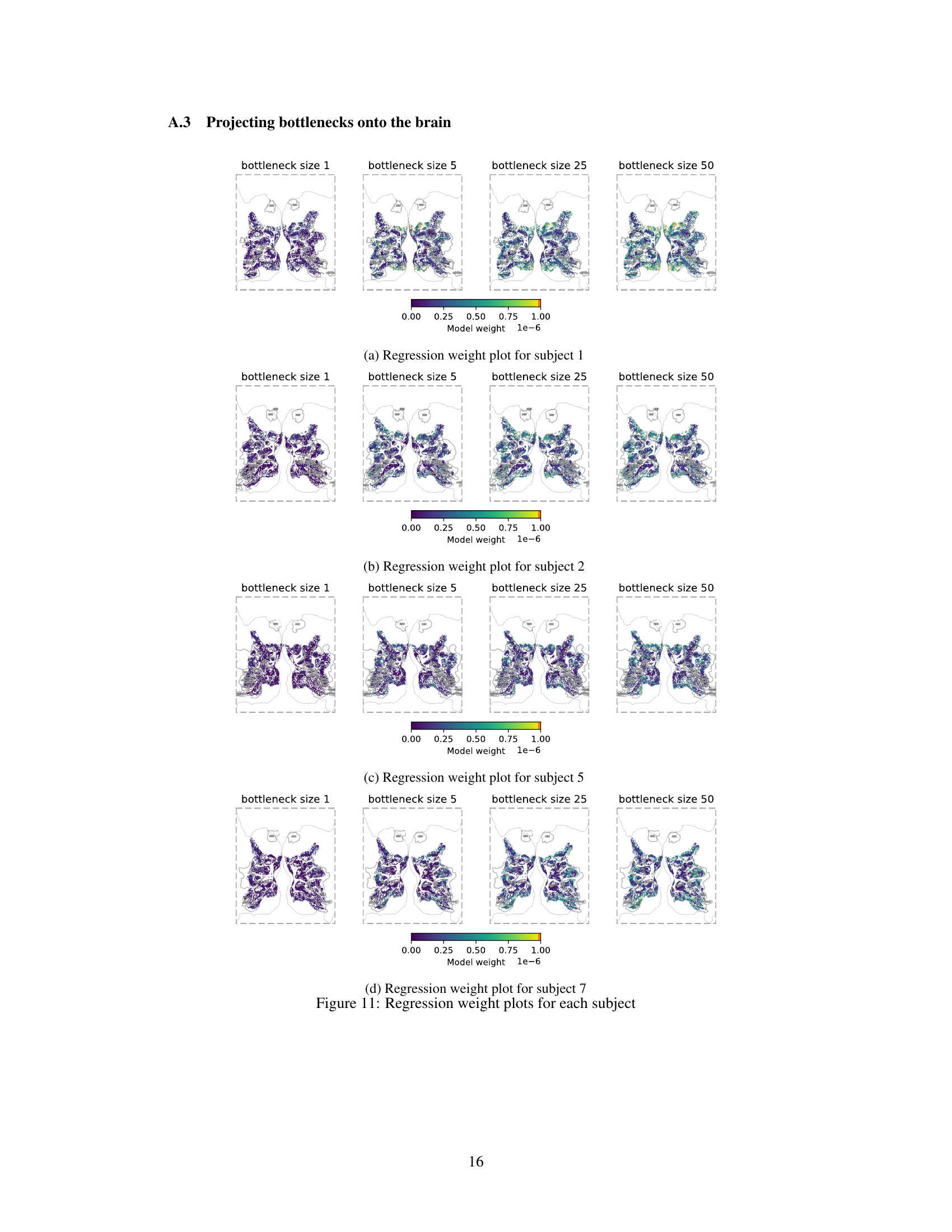

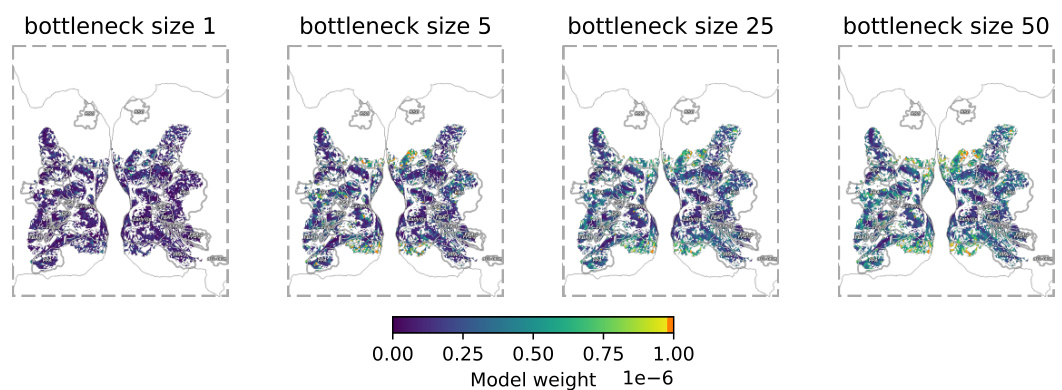

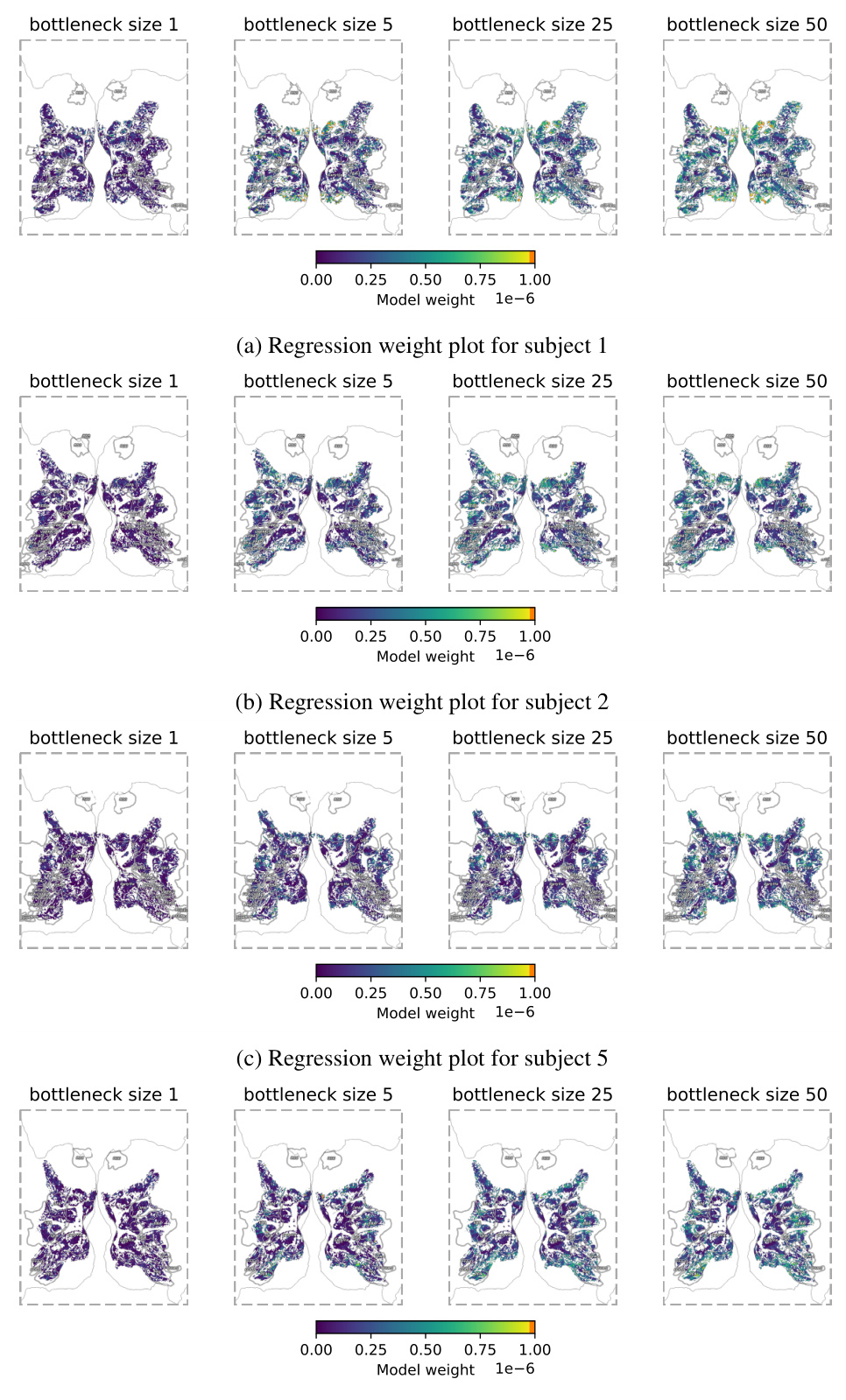

This figure shows the brain regions that contribute the most to the reconstruction of images at different bottleneck sizes using BrainDiffuser. The color intensity represents the weight of each brain region in the reconstruction. The figure highlights that while models quickly identify and utilize specific brain areas (in the early visual cortex) for reconstruction, they do not significantly expand their focus to other areas even with larger bottleneck sizes. This suggests that improving the generative models might have a bigger impact than improving the brain signal extraction.

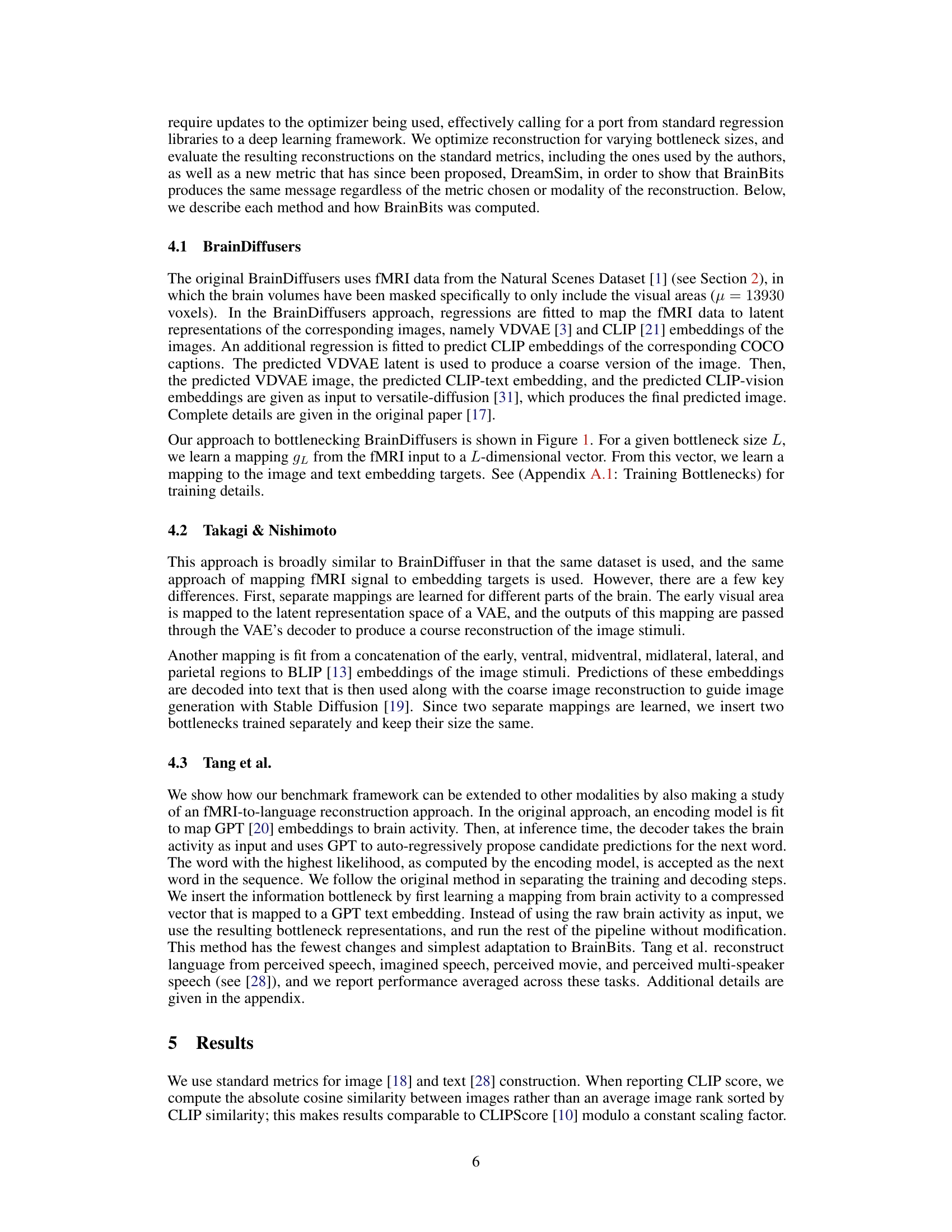

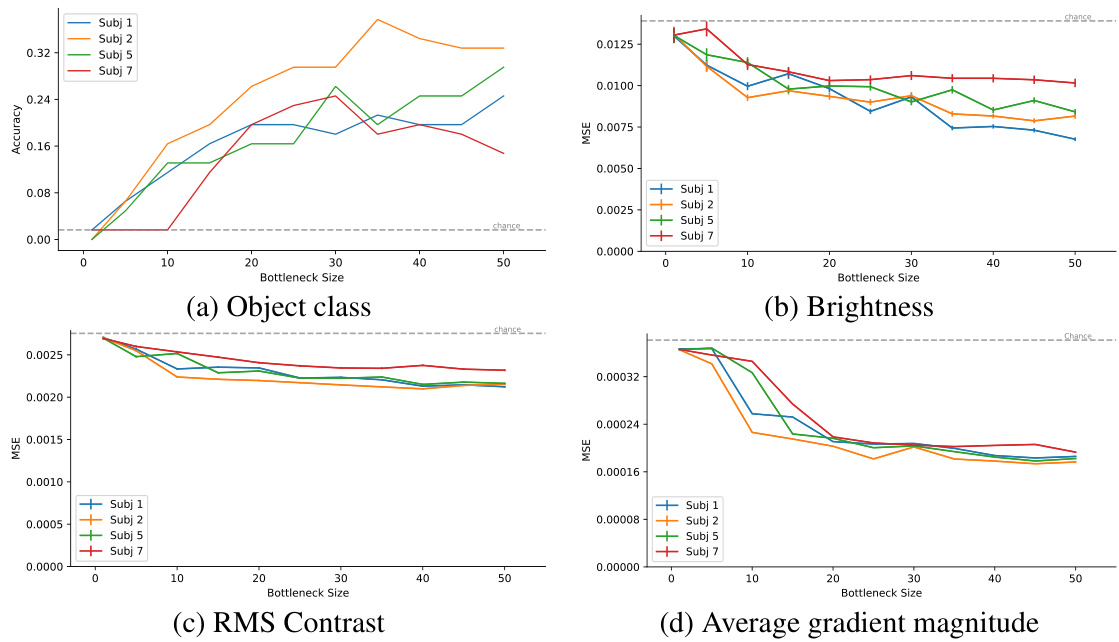

This figure shows the decodability of four different visual features (object class, brightness, RMS contrast, and average gradient magnitude) as a function of bottleneck size for the BrainDiffusers model. It demonstrates that low-level features like brightness and contrast are easily decoded even with small bottleneck sizes, while high-level features like object class require larger bottlenecks to achieve reliable decoding. This analysis helps understand what types of information are captured at different bottleneck sizes, providing insights into the model’s learning process.

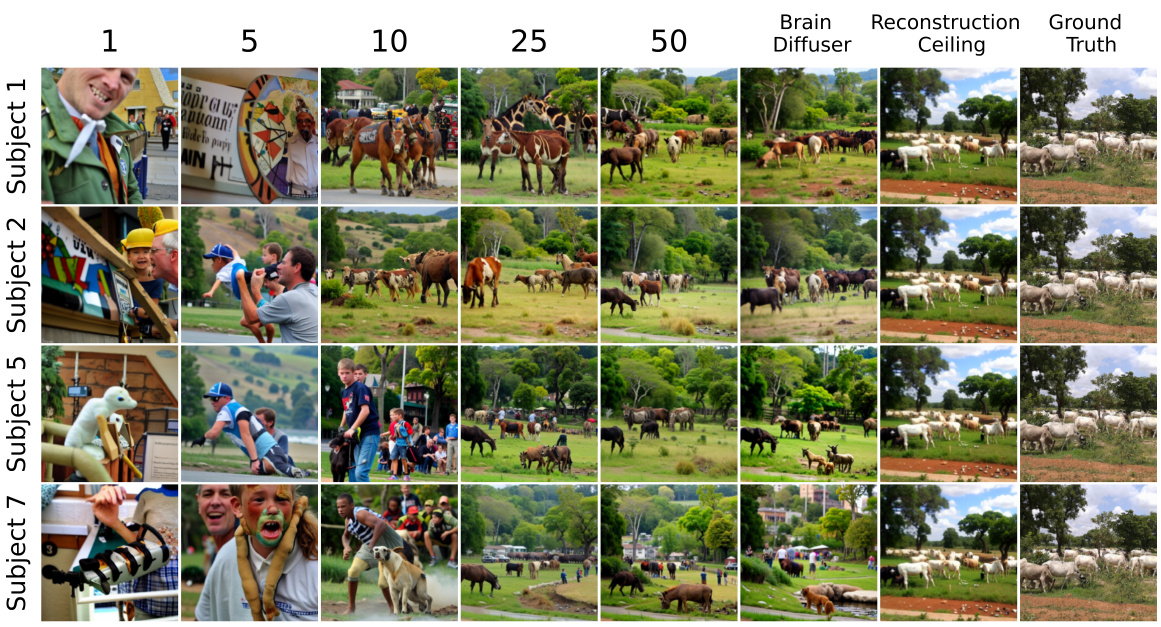

This figure shows the image reconstruction results from the BrainDiffuser model for four different subjects at various bottleneck sizes (1, 5, 10, 25, 50). Each row represents a different subject, and each column shows the reconstruction at a specific bottleneck size. The rightmost column shows the ground truth image. The figure demonstrates how the quality of image reconstruction improves with increasing bottleneck size.

This figure shows examples of image and text reconstructions from brain activity using different bottleneck sizes. It demonstrates that high-fidelity reconstructions can be achieved even when using a small fraction of the available brain data. The results suggest that generative models rely heavily on their internal priors, and only a small amount of neural information is needed to guide them towards high-quality reconstructions.

This figure shows examples of images and text reconstructed using different bottleneck sizes for three different reconstruction methods. The results demonstrate that high-quality reconstructions can be achieved using surprisingly little information from brain recordings, highlighting the power of generative models’ priors.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the BrainBits method in reconstructing high-fidelity images and text from a small fraction of brain data. It shows examples for three different reconstruction methods (BrainDiffuser, Takagi & Nishimoto 2023, Tang et al. 2023) and several bottleneck sizes. The results indicate that surprisingly little information from the brain is needed to achieve high-quality reconstructions, highlighting the role of generative model priors.

This figure visualizes the weights of the bottleneck mapping projected onto the brain for each subject (1, 2, 5, and 7) at different bottleneck sizes (1, 5, 25, and 50). The color intensity represents the magnitude of the weights, indicating the relative importance of different brain regions in the reconstruction process at varying levels of information compression. It shows how the model’s focus on specific brain areas changes as the amount of available brain data increases. The areas highlighted are ROIs (Regions Of Interest) in the brain related to visual processing.

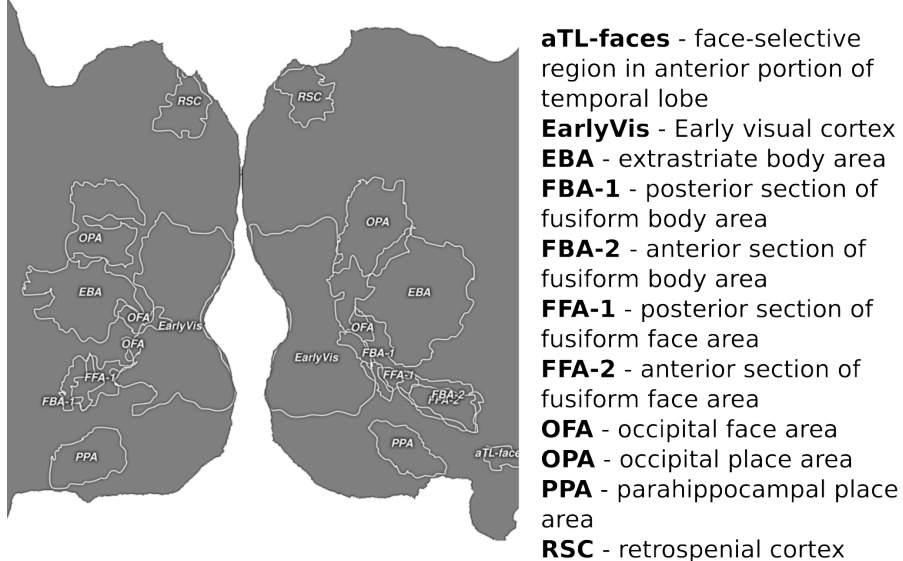

This figure shows the legend for the brain regions of interest (ROIs) used in Figures 5 and 11 of the paper. The legend provides abbreviations and full names for several brain regions involved in visual processing, including face-selective regions (aTL-faces), early visual cortex (EarlyVis), extrastriate body area (EBA), fusiform body area (FBA-1 and FBA-2), fusiform face area (FFA-1 and FFA-2), occipital face area (OFA), occipital place area (OPA), parahippocampal place area (PPA), and retrospenial cortex (RSC). The image displays the location of these ROIs within the brain.

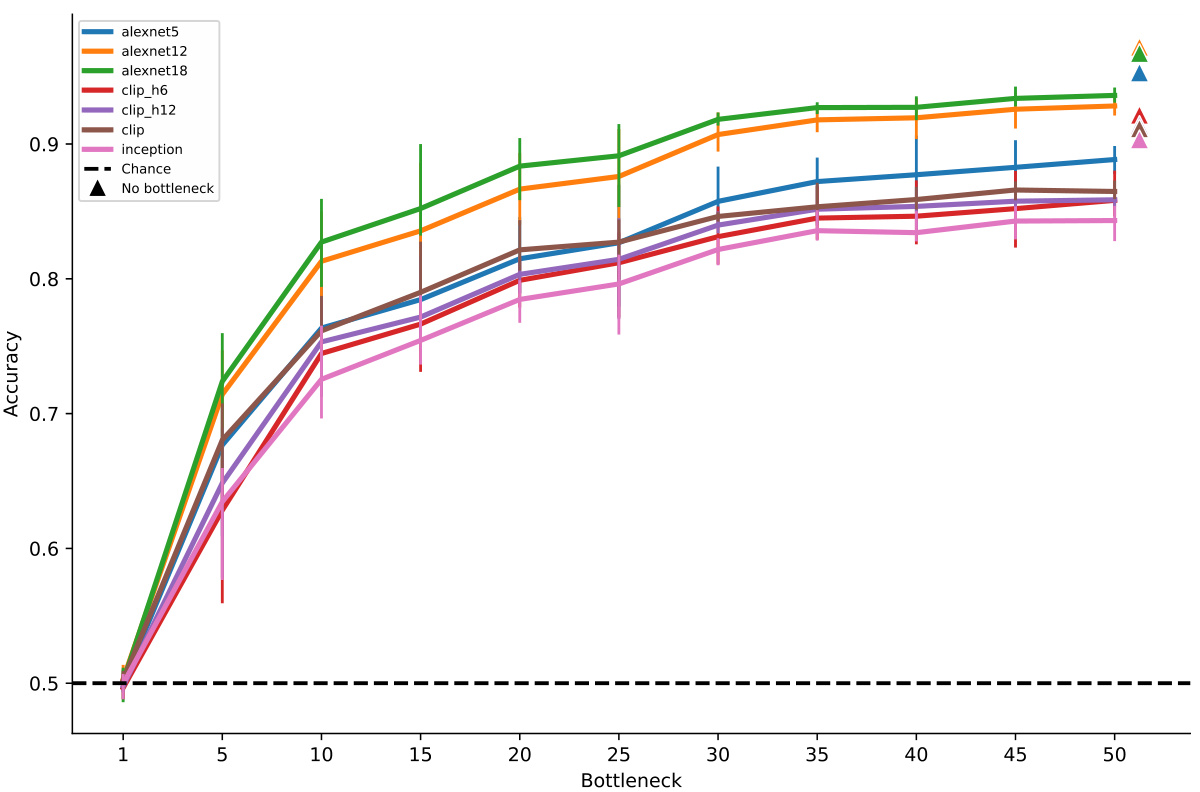

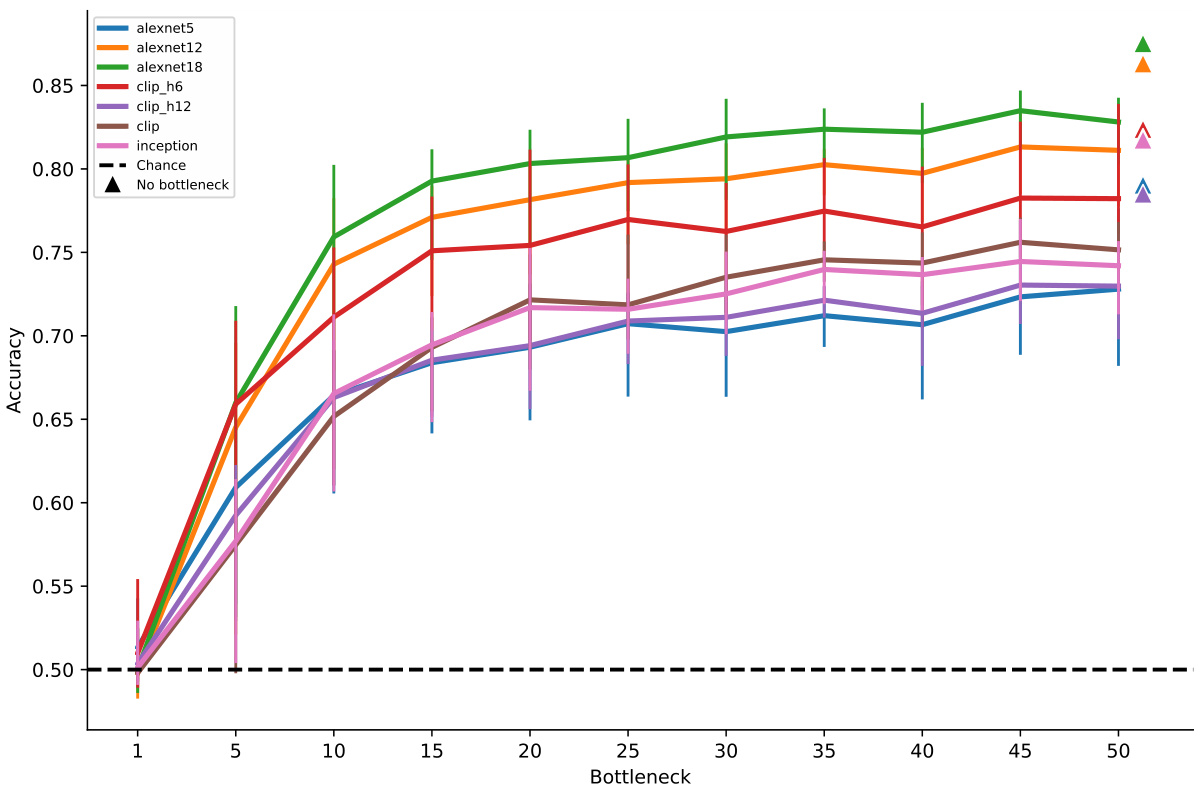

The figure shows the identification accuracy of the BrainDiffuser method as a function of bottleneck size. The identification accuracy is measured using the latent embeddings of ground-truth and decoded images. The chance level and the performance without bottleneck are also shown for comparison. Different image encoders (alexnet5, alexnet12, alexnet18, clip_h6, clip_h12, clip, inception) were used to evaluate the agreement between latent embeddings of the ground-truth and the decoded images. The results show that the identification accuracy increases with the bottleneck size, indicating that more information from the neural recordings is beneficial for improving the quality of the decoded images.

This figure shows the identification accuracy of the BrainDiffuser method across different bottleneck sizes. The identification accuracy is measured by comparing the latent embeddings of ground-truth and decoded images using a protocol described in a cited paper [26]. The graph displays how the accuracy changes as the size of the information bottleneck increases, indicating the amount of brain information needed to achieve a certain level of reconstruction accuracy. Several different models (alexnet5, alexnet12, etc.) are compared.

This figure shows the results of applying the BrainBits method to three different stimulus reconstruction methods (BrainDiffuser, Takagi & Nishimoto 2023, and Tang et al. 2023). It demonstrates that high-fidelity reconstructions of images and text can be achieved using only a small fraction of the full brain data. The figure visually compares reconstructions at different bottleneck sizes, highlighting the surprising similarity between reconstructions using a small bottleneck and the full brain data. It also shows that the reconstruction quality generally improves as the bottleneck size increases.

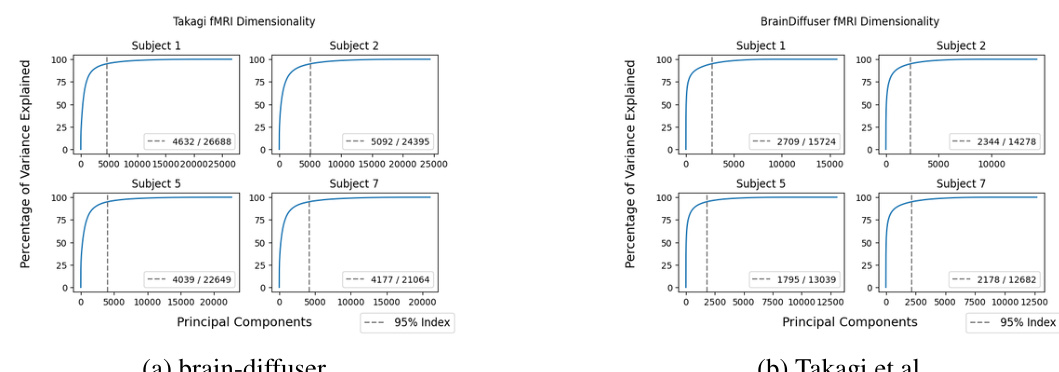

This figure shows the effective dimensionality of fMRI inputs for both BrainDiffuser and Takagi et al. methods. The effective dimensionality represents the number of dimensions needed to explain 95% of the variance in the fMRI data, as determined by Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The figure visually displays the cumulative variance explained by increasing numbers of principal components for each subject in both models, providing a comparison of how efficiently each method utilizes brain data. The dashed line represents the 95% variance explained threshold, and the intersection of the line and the curve shows the effective dimensionality for each subject.

Full paper#