↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Differential privacy (DP) safeguards sensitive data by injecting noise, controlled by a privacy budget (ε). Choosing an appropriate ε is crucial as it balances data utility and privacy. Current methods struggle to offer intuitive guidance for setting ε, and existing approaches often prove inflexible or overly simplistic. This leads to difficulty in practical application.

This research presents a novel Bayesian framework for setting ε. It leverages the relationship between DP and Bayesian disclosure risk, enabling agencies to define acceptable posterior-to-prior risk ratios at different prior risk levels, thereby determining an optimal ε. The framework is versatile and works with any DP mechanism, offering closed-form solutions for certain risk profiles and a general solution for more complex scenarios. This approach eliminates the need for subjective parameter choices, enhancing DP’s practical usability and ensuring a better balance between data utility and privacy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with differential privacy, a technique to protect sensitive data. It offers a novel, practical framework for setting the privacy budget (ε), a critical parameter influencing the trade-off between data utility and privacy. This framework enhances the understanding and application of differential privacy, significantly impacting various research areas dealing with sensitive data analysis.

Visual Insights#

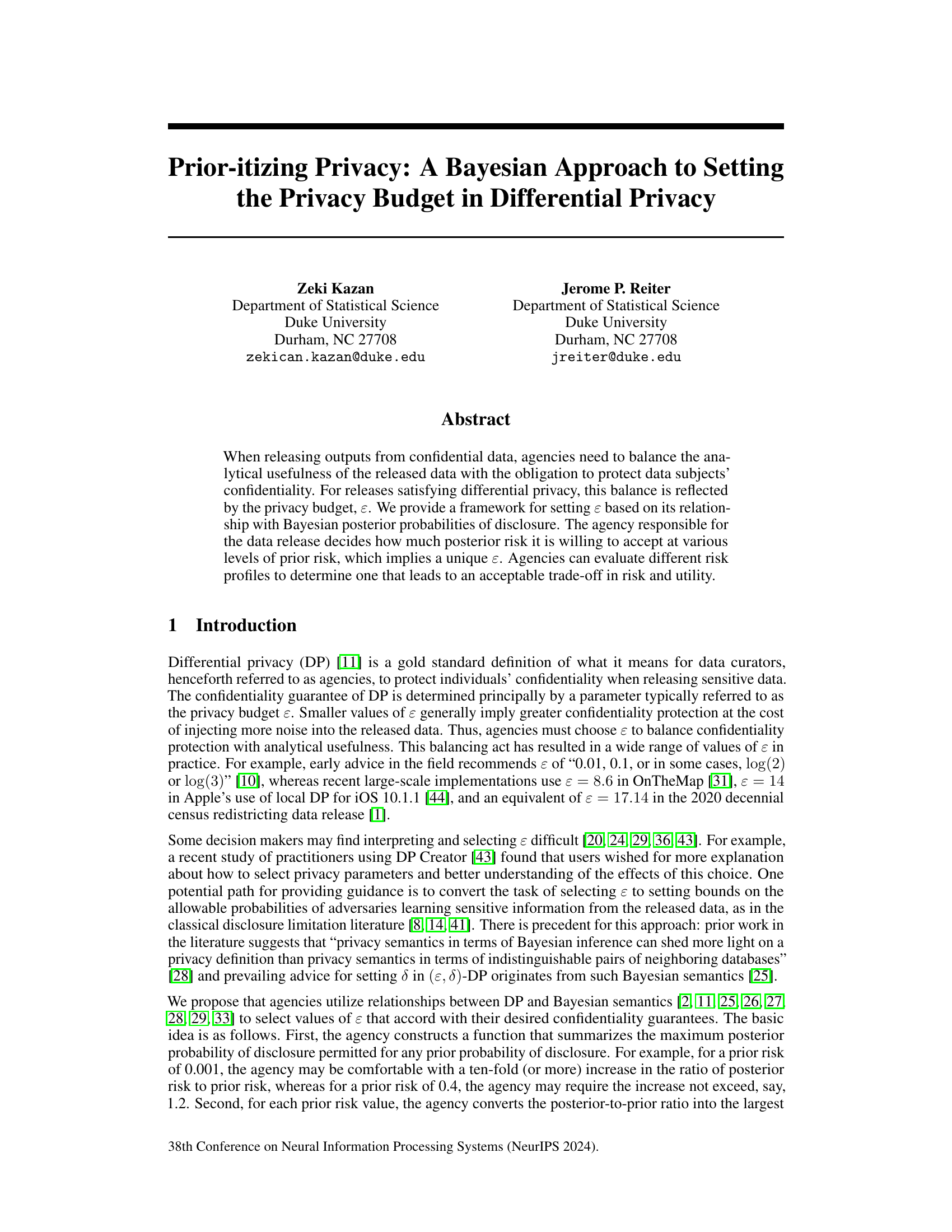

This figure shows two examples of risk profiles and their corresponding maximal allowable epsilon values for each prior probability. Agency 1’s risk profile is based on a constant bound on the relative risk except for low prior probabilities where it bounds the absolute risk. Agency 2’s profile bounds the relative risk for high prior probabilities and bounds the absolute risk for low prior probabilities. The plots illustrate the tradeoff between risk and data utility; higher epsilon allows greater data utility but increases disclosure risk.

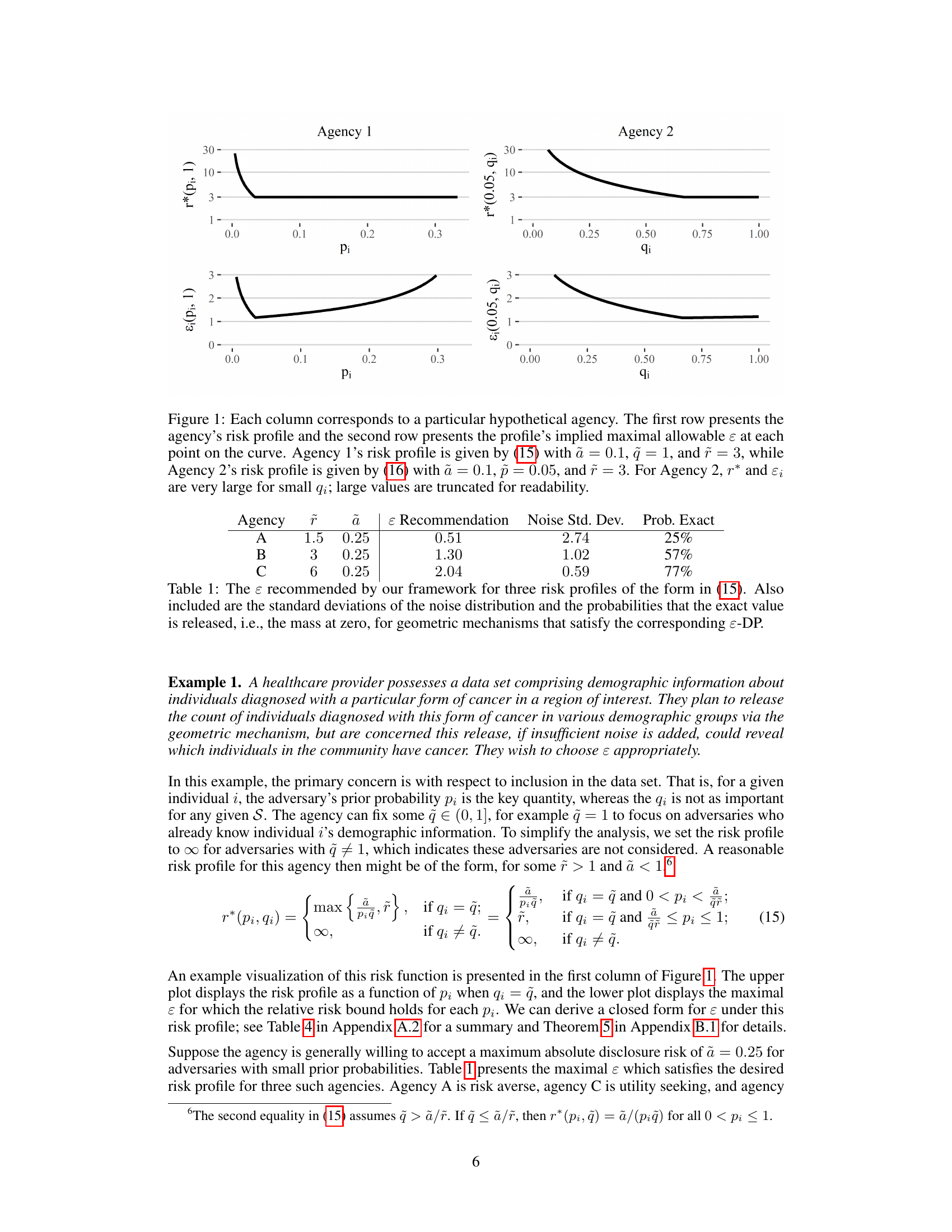

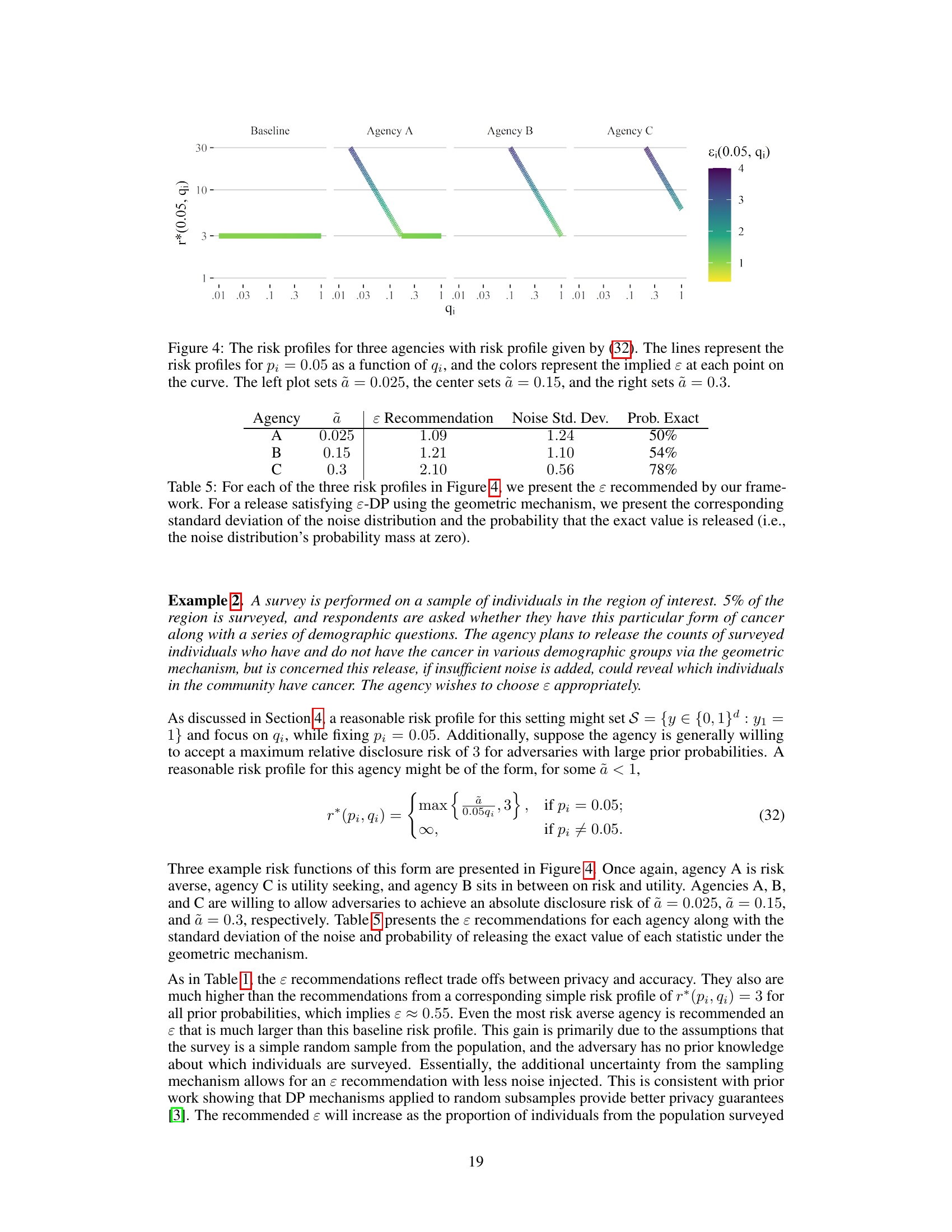

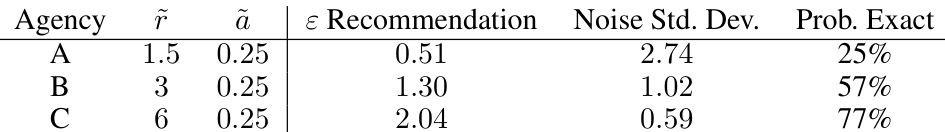

This table presents the epsilon (ɛ) values recommended by the proposed framework for three different risk profiles, along with the corresponding standard deviations of the added noise and the probabilities of obtaining the exact value from a geometric mechanism satisfying ɛ-DP. The risk profiles are defined in equation (15) and represent varying degrees of risk aversion.

In-depth insights#

Bayesian DP#

Bayesian Differential Privacy (DP) offers a novel approach to address the inherent tension between data utility and individual privacy in DP mechanisms. It leverages Bayesian statistics to model the adversary’s knowledge and beliefs about sensitive data. Instead of solely focusing on worst-case scenarios, Bayesian DP considers the adversary’s prior information to refine privacy guarantees, leading to potentially more useful data releases while still maintaining privacy. By incorporating prior knowledge, the Bayesian framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of the risk associated with releasing differentially private data. This could lead to improvements in the selection of privacy parameters. However, a key challenge lies in accurately modeling the adversary’s prior knowledge, a task that can be subjective and depend heavily on context-specific information. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to selecting appropriate prior distributions that accurately represent the adversary’s potential knowledge and capabilities. Another important factor is the computational complexity that arises from incorporating Bayesian methods into DP; this is particularly true for high-dimensional data. It also requires further research to investigate how Bayesian DP performs in various practical data release settings. The efficacy and practicality of this approach are critical aspects that demand attention.

Risk Profiles#

The concept of ‘Risk Profiles’ in the context of differential privacy is crucial for balancing the trade-off between data utility and individual privacy. It allows agencies to define acceptable levels of disclosure risk, not as a fixed constant, but rather as a function of the prior probability of disclosure. This approach acknowledges that different prior risks may warrant different levels of acceptable posterior risks. A risk-averse agency, for instance, might impose stricter limits on the increase in disclosure risk (posterior-to-prior ratio) for high prior risks, while being more lenient with lower prior risks. This flexibility makes the framework more adaptable to various privacy sensitivities depending on the context. The selection of a risk profile is subjective and reflects the agency’s risk tolerance and values; it is not a purely technical or data-driven decision but rather a policy choice that requires careful consideration and justification.

Privacy-Utility Tradeoff#

The inherent tension between privacy and utility is a central theme in differential privacy. Balancing the need for robust privacy guarantees with the desire to extract meaningful insights from data is crucial. The paper’s framework for setting the privacy budget (ε) acknowledges this trade-off by enabling agencies to define their acceptable levels of disclosure risk. This approach is a shift away from simply choosing an arbitrary ε, offering a more nuanced risk-utility balancing approach. The framework allows agencies to customize the risk profiles based on their risk tolerance, potentially allowing for more utility in data releases without compromising privacy where acceptable. However, careful consideration must be given to the chosen risk profiles, especially when considering the impacts on various groups and the potential for inequitable treatment. The method proposed emphasizes a thoughtful selection of ε, preventing an over-restrictive approach that may unnecessarily sacrifice data utility, which is an essential consideration in practical applications of differential privacy.

DP Mechanism Choice#

The choice of DP mechanism significantly impacts the privacy-utility trade-off. The geometric mechanism, for instance, is popular for its simplicity and applicability to count queries, but its unbounded noise can lead to significant variance in the released data, particularly with low privacy budgets. Conversely, mechanisms like the Laplace mechanism offer a different balance, providing bounded noise for numerical data but often resulting in less utility. Advanced composition theorems allow for combining multiple differentially private mechanisms, but careful consideration of their individual privacy parameters (epsilon and delta) is crucial to avoid excessive noise accumulation. The optimal mechanism selection is therefore highly context-dependent and requires balancing the data type, query type, desired accuracy, and acceptable level of noise. Future work should investigate adaptive mechanisms that adjust their parameters based on the data characteristics and query responses to further optimize privacy and utility. Exploring alternative mechanisms tailored to specific data types and query structures is also important for maximizing the practical value of differential privacy.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle continuous data would broaden its applicability significantly. Currently, the framework focuses on discrete data, limiting its use in many real-world scenarios where continuous variables are prevalent. Another key area for future work is investigating the robustness of the assumptions underlying the framework, particularly Assumption 2. While the authors argue that their assumptions are milder than those in prior work, a detailed analysis of sensitivity to deviations from these assumptions is crucial. Finally, exploring alternative risk profiles beyond the ones examined could reveal more nuanced and effective strategies for balancing privacy and utility, leading to a richer understanding of the trade-offs involved. Developing user-friendly tools that implement the framework would be a valuable contribution, enabling practitioners to readily apply these methods in real-world data release processes.

More visual insights#

More on figures

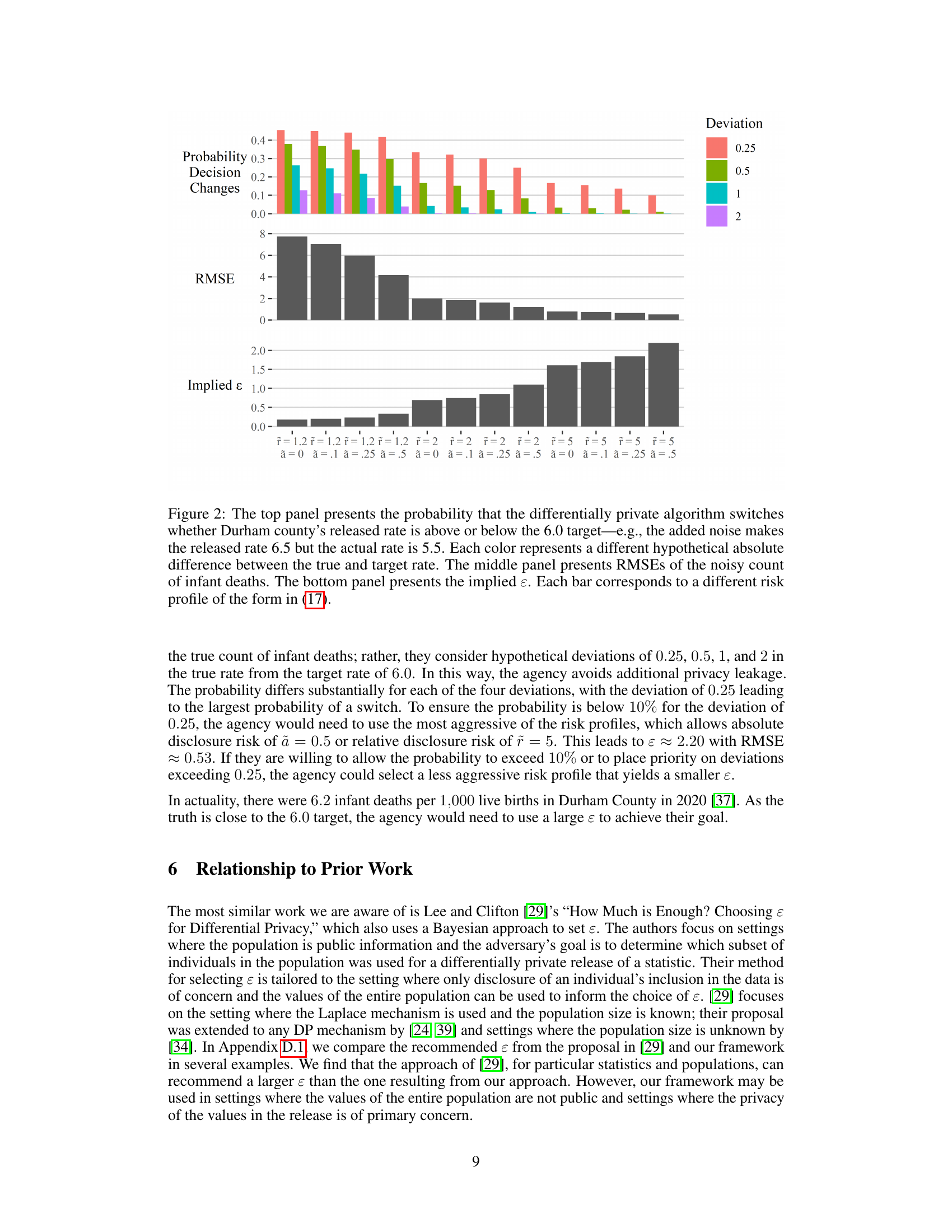

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed framework to a real-world example involving infant mortality data in Durham County, NC. The top panel displays the probability that the differentially private mechanism will change the classification of the infant mortality rate as above or below the target rate (6.0 deaths per 1000 live births). The middle panel shows the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the noisy data for different risk profiles, while the bottom panel presents the corresponding implied epsilon (ε) values. Each bar represents a different risk profile of the form defined in equation (17), illustrating how different risk tolerances affect the privacy-utility trade-off.

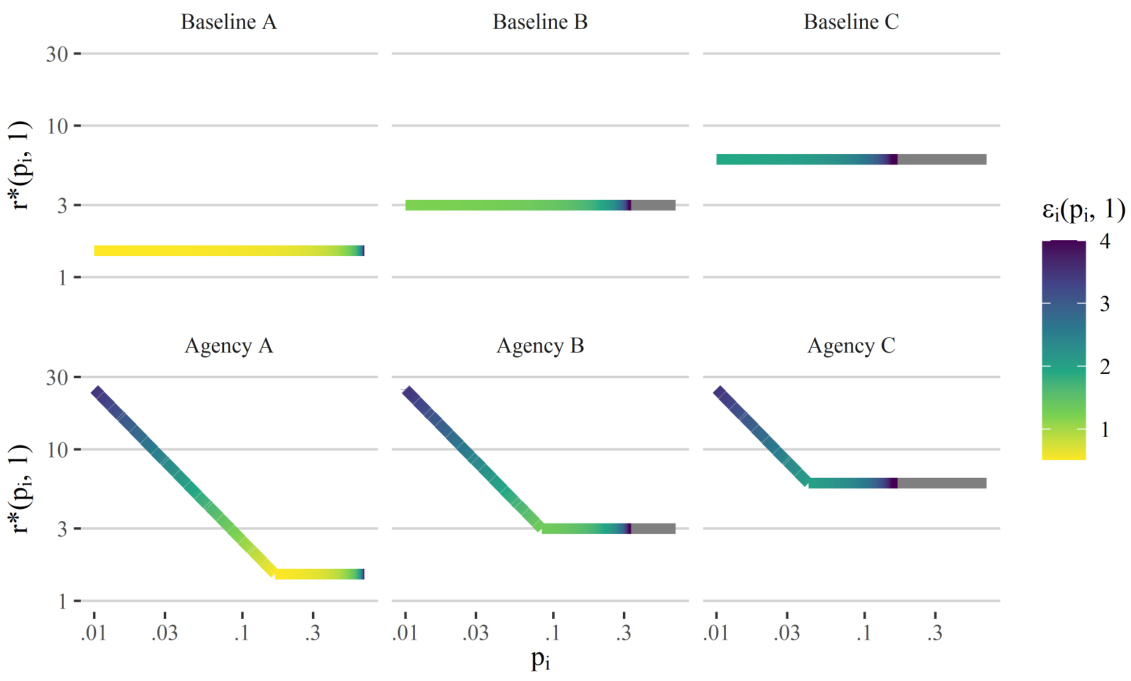

This figure illustrates three different risk profiles (Agency A, B, and C) with varying risk aversion levels. Each panel shows the risk profile r*(pi,1) as a function of pi (prior probability) for qi = 1. The lower panels display the maximal allowable ε for each pi under each agency’s profile. The color intensity represents the magnitude of ε. The upper panels show the baseline risk profile r*(pi, 1) = r where r is a constant value for different risk tolerance (r=1.5, 3, and 6). This visualizes how the choice of risk profile (reflecting the agency’s tolerance for different levels of risk) directly impacts the recommended value of ε.

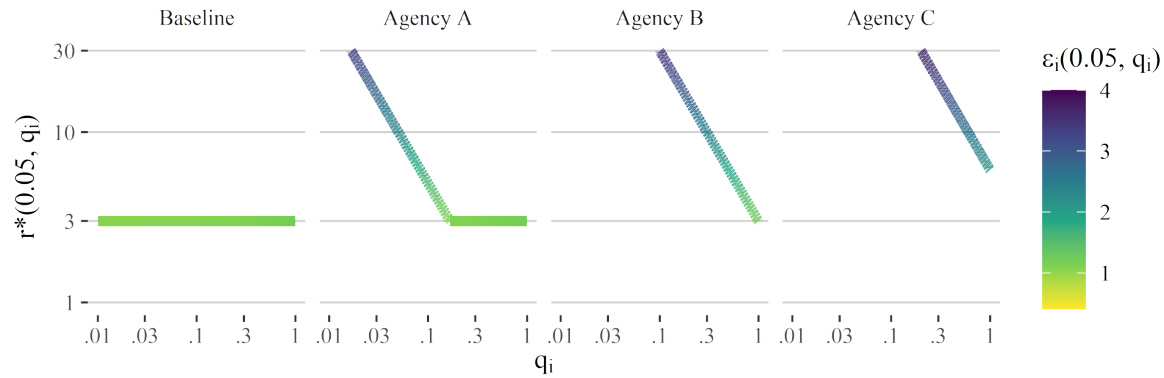

This figure shows three different risk profiles, with varying levels of risk aversion, and the corresponding values of epsilon (ε). The x-axis represents the prior probability of disclosure (qi), given a prior probability of inclusion (pi) of 0.05. The y-axis shows the maximum acceptable posterior-to-prior risk ratio (r*(0.05, qi)) for each agency, defining their risk tolerance. The color intensity represents the implied epsilon (ε) calculated based on the risk profile using the framework presented in the paper.

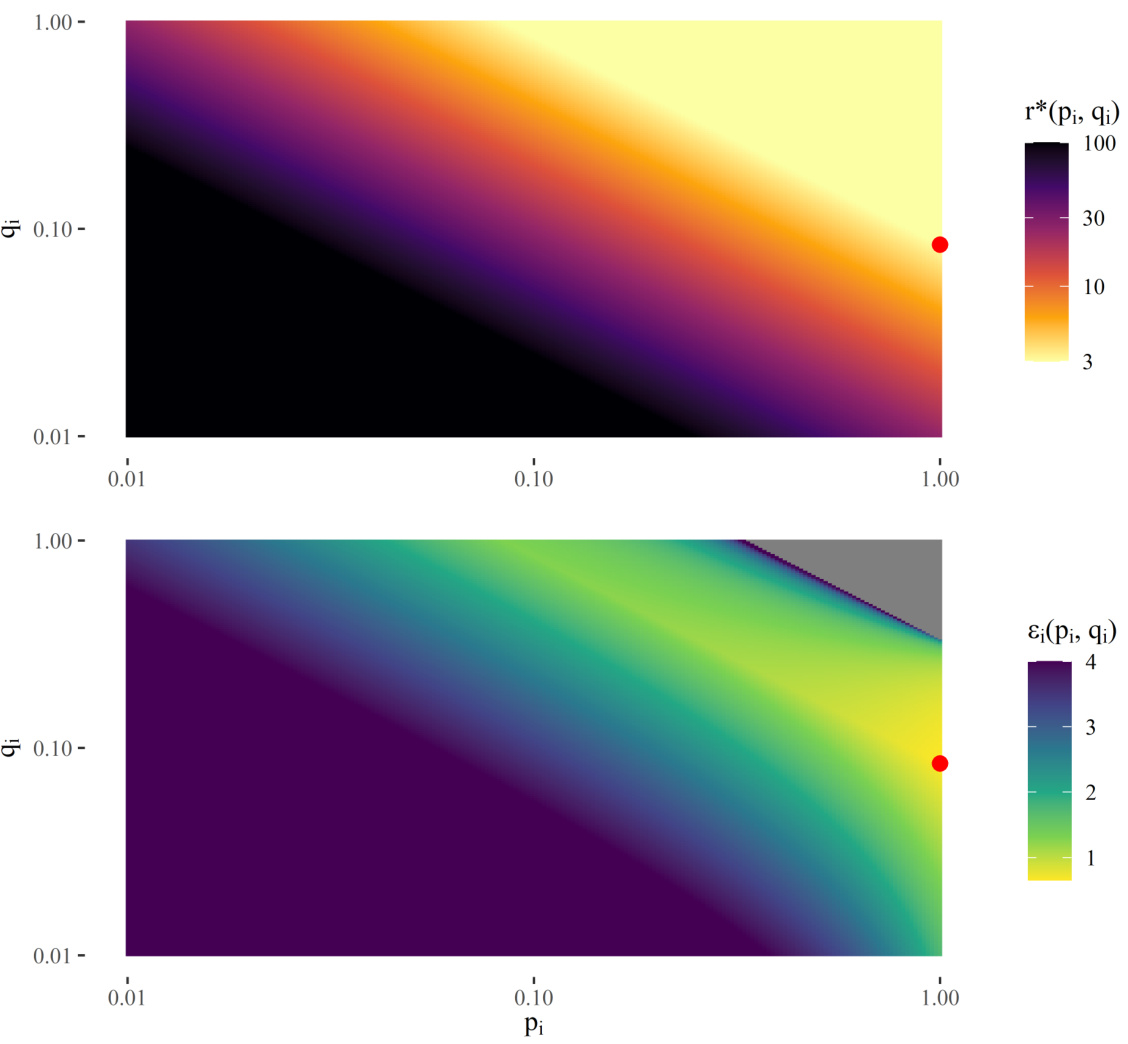

This figure shows a two-dimensional visualization of the risk profile and the implied epsilon values. The top panel displays the risk profile r*(pi, qi) as a heatmap, where the color intensity represents the value of r*. The bottom panel shows the corresponding epsilon values ɛi(pi, qi), again as a heatmap. The red dot marks the point (pi, qi) that minimizes ɛi(pi, qi), representing the optimal epsilon according to the defined risk profile.

More on tables

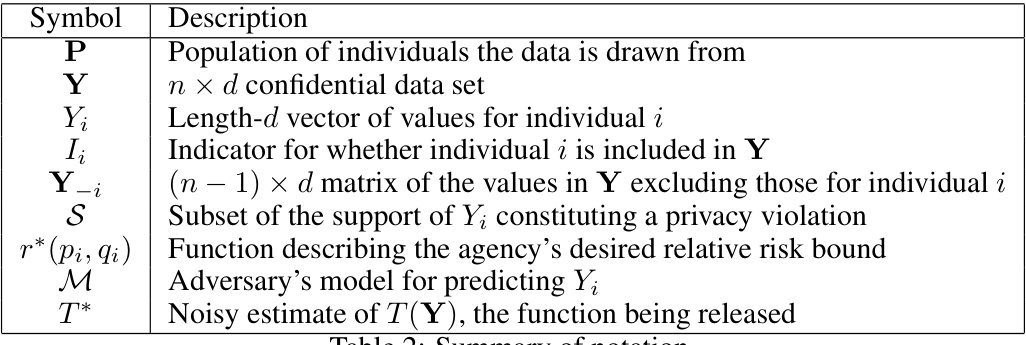

This table summarizes the notations used in the paper, specifying the meaning of symbols such as P (population), Y (data set), Yi (vector of values for individual i), Ii (indicator of inclusion of individual i), Y-i (matrix excluding values for individual i), S (subset of support for privacy violation), r*(pi,qi) (agency’s relative risk bound function), M (adversary’s predictive model), and T* (noisy estimate of the function being released).

This table presents the epsilon (ɛ) values recommended by the proposed framework for three different risk profiles, each designed to balance privacy and utility differently. The table also shows the corresponding standard deviation of the noise added to the data and the probability that the exact value of the statistic will be released, providing context on the impact of ɛ on both data utility and privacy.

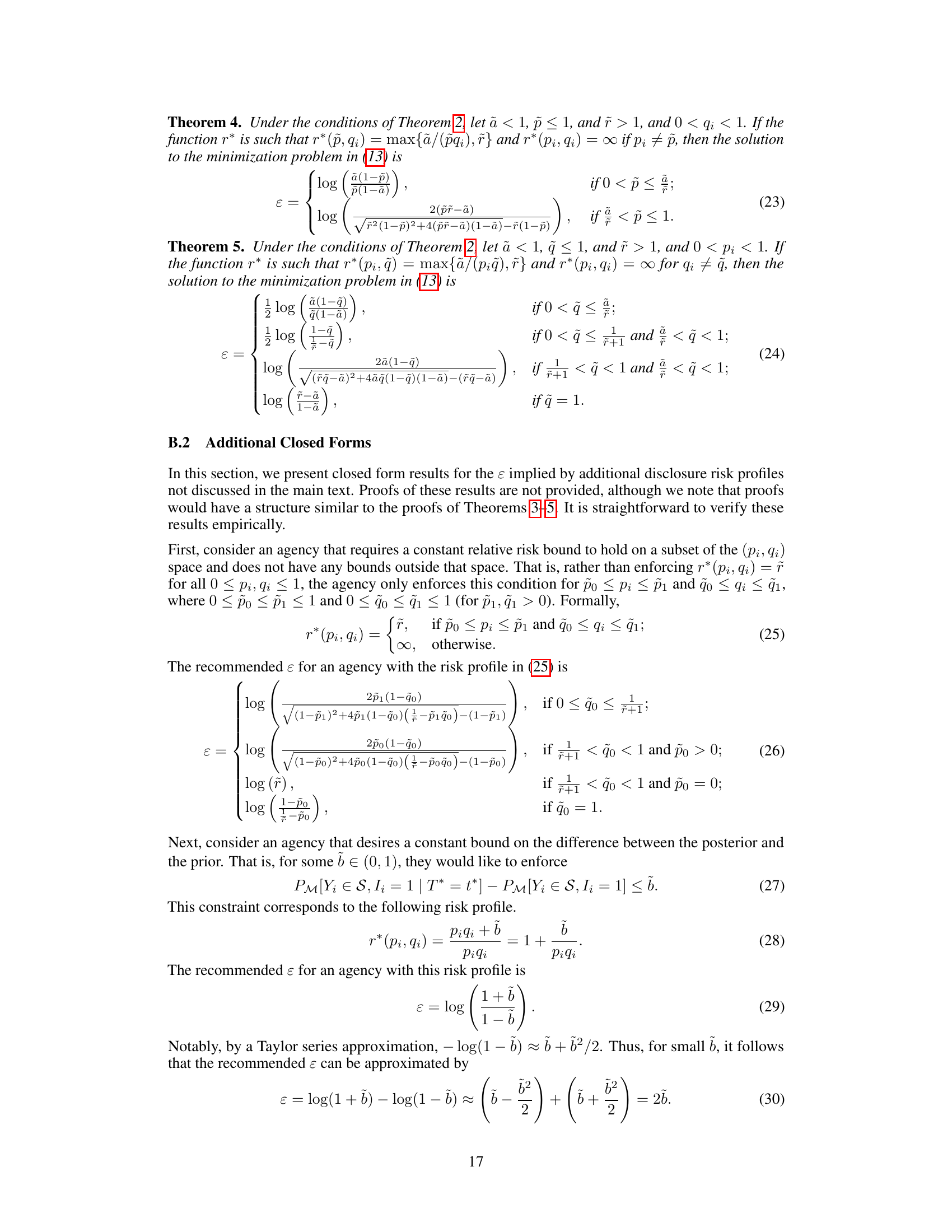

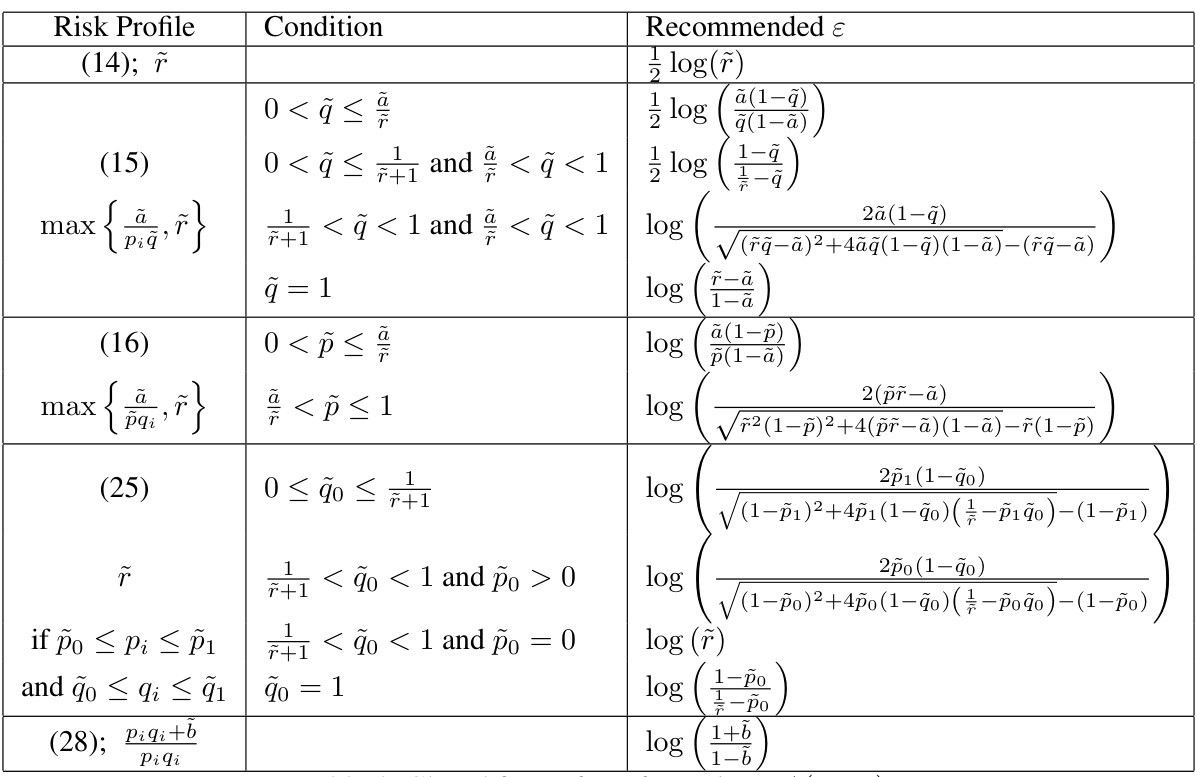

This table presents closed-form expressions for the privacy parameter epsilon (ε) under different risk profiles. The risk profiles define the acceptable trade-off between privacy and utility, specifying the maximum allowable increase in the ratio of posterior risk to prior risk for different levels of prior risk. The conditions column indicates the range of prior probabilities (pi and qi) for which each closed-form expression is valid. The table facilitates the selection of an appropriate epsilon value for a given risk profile by directly providing the formula for calculating it.

This table presents the recommended epsilon values (ε) for three different risk profiles, which reflect varying levels of risk aversion. Each risk profile is defined by a function that specifies an acceptable maximum level of relative disclosure risk. For each risk profile, the table shows the recommended epsilon, the standard deviation of the added noise, and the probability of releasing the exact value of the statistic. This illustrates how the choice of risk profile affects the level of privacy protection.

Full paper#