↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) raise significant concerns regarding permissible data usage, particularly concerning whether they “memorize” training data. Existing memorization definitions have limitations, leading to ambiguity and difficulty in assessing compliance. This makes it hard to determine whether model owners may be violating terms of data usage.

This work introduces the Adversarial Compression Ratio (ACR) to address these issues. ACR measures memorization by comparing the length of the shortest prompt eliciting a training string to the string’s length itself. The results show ACR is an effective tool for determining when model owners violate terms around data usage and provides a critical lens through which to address data misuse. The adversarial nature of the approach is robust to unlearning methods designed to obscure memorization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in LLMs and legal fields. It provides a practical tool (ACR) to assess data memorization, addressing legal concerns around data usage. The adversarial approach offers a robust metric overcoming limitations of existing memorization definitions. This opens up new avenues for LLM compliance monitoring and legal analysis.

Visual Insights#

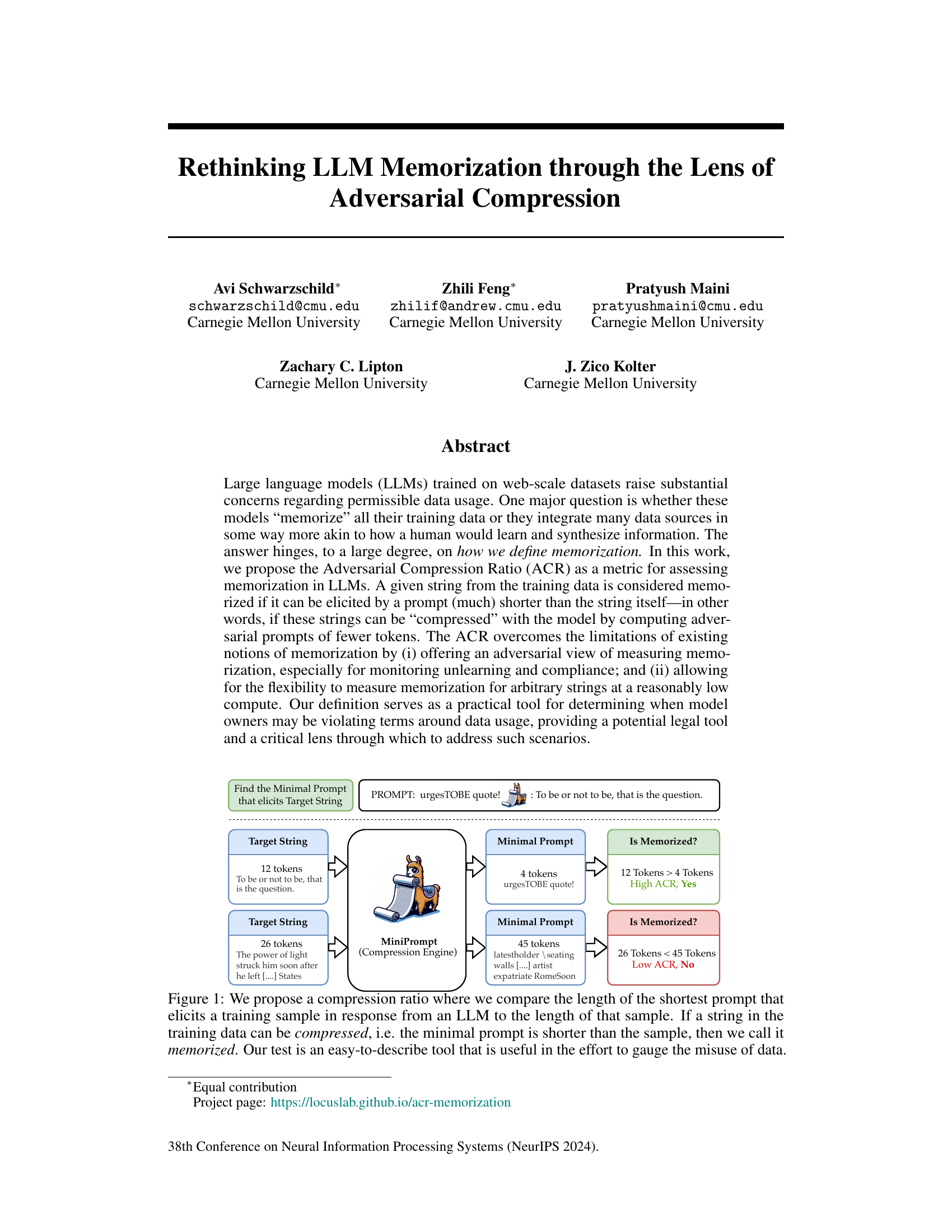

This figure illustrates the concept of Adversarial Compression Ratio (ACR) for measuring memorization in LLMs. It shows two examples: one where a short prompt successfully elicits a long target string (high ACR, indicating memorization), and another where a long prompt is needed for a shorter string (low ACR, no memorization). The ACR is calculated by comparing the length of the shortest prompt to the length of the target string. A high ACR suggests that the LLM has memorized the target string because it can be reproduced with a significantly shorter prompt.

This table presents the average adversarial compression ratio (Avg. ACR) and the portion of data memorized for the Pythia-1.4B model when tested on two datasets: Famous Quotes and Paraphrased Quotes. The results show a significant difference in memorization between the original famous quotes and their paraphrased versions, indicating that the model memorizes specific wording rather than the underlying concept.

In-depth insights#

Adversarial Compression#

The concept of “Adversarial Compression” presented in the research paper offers a novel approach to evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) memorization. It cleverly leverages the adversarial nature of prompt engineering, searching for minimal prompts that elicit specific training data. This adversarial approach is crucial as it moves beyond simple completion-based methods that are easily circumvented by models trained to avoid verbatim reproduction. The use of compression ratio as a metric to assess memorization allows for a more nuanced understanding than previous methods by comparing the length of the shortest adversarial prompt to the length of the target text. A higher compression ratio suggests that the LLM has indeed memorized the text, as it can reconstruct it from a much smaller input. This method also introduces a practical legal tool and addresses issues around data usage and compliance. The robustness against countermeasures such as unlearning is a significant strength, providing a more accurate and reliable way to evaluate LLM memorization.

Memorization Metrics#

The concept of “Memorization Metrics” in evaluating large language models (LLMs) is multifaceted and crucial. Existing metrics often suffer from limitations; for example, exact string matching is too restrictive, failing to capture nuanced memorization, while completion-based methods are too permissive and easily evaded through model manipulation. Adversarial compression ratios (ACR) offer a promising alternative, focusing on the minimal prompt length required to elicit a specific training string. This adversarial approach is robust against simple obfuscation techniques and provides a more practical and legally sound metric for assessing memorization. Furthermore, ACR acknowledges the inherent trade-off between memorization and generalization, recognizing that complete memorization isn’t necessarily undesirable. A comprehensive evaluation should consider multiple metrics and carefully define the threshold for what constitutes “memorization” based on context and intended use, acknowledging the need for both functional and legal considerations. The interplay between compression, model architecture, and data properties significantly impacts the effectiveness of any memorization metric, necessitating further research to understand these dynamics fully.

Unlearning Illusion#

The concept of “Unlearning Illusion” in the context of large language models (LLMs) highlights a crucial challenge in evaluating and ensuring responsible data handling. LLMs can appear to have ‘forgotten’ information through techniques like in-context learning, but this is often a superficial masking rather than true deletion. The model’s weights may still implicitly contain the data, allowing retrieval through cleverly crafted prompts. This illusion of compliance with data privacy regulations or terms of use poses a significant problem. Existing definitions of memorization frequently fall short, focusing on exact reproduction of training data. The authors argue that a robust metric needs to account for this adversarial compression, where shorter inputs can elicit longer, memorized outputs. Therefore, an effective assessment needs to shift focus from simple completion accuracy to a compression ratio metric, evaluating the ratio of prompt length to the length of the reproduced text. This approach is more robust to techniques designed to circumvent traditional memorization checks, offering a more reliable way to measure and monitor compliance. The illusion is shattered by focusing on underlying model weights and leveraging adversarial methods to assess effective data retention.

Model Size Effects#

Analysis of model size effects in large language models (LLMs) reveals a complex relationship between model scale and performance. Larger models generally exhibit superior performance on various benchmarks, often demonstrating better generalization and improved ability to handle complex tasks. This is attributed to the increased capacity of larger models to learn intricate patterns and relationships within the training data. However, this advantage is not without drawbacks. Larger models often require significantly more computational resources for training and inference, posing challenges in terms of cost and accessibility. Furthermore, the increased capacity can also lead to overfitting, where the model memorizes specific details from the training data rather than learning generalizable representations. This effect can manifest as an increased susceptibility to adversarial attacks or a diminished ability to extrapolate beyond the training distribution. Therefore, the optimal model size often represents a trade-off between performance benefits and practical limitations, with the ideal size depending on the specific application and available resources. Careful consideration of these competing factors is essential when designing and deploying LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated prompt optimization techniques beyond greedy decoding, potentially leveraging reinforcement learning or evolutionary algorithms to discover even shorter adversarial prompts. Investigating the robustness of the ACR metric across different model architectures and training datasets is crucial to establish its generalizability and practical utility. Further work should also analyze the relationship between the ACR and other existing memorization metrics, aiming to create a more holistic understanding of LLM memorization. A valuable extension would involve developing more nuanced legal frameworks that incorporate the ACR as a measure for assessing fair use, balancing data protection with the advancement of AI technology. Furthermore, exploring the impact of different unlearning techniques on the ACR could help in designing more effective methods for mitigating memorization concerns. Finally, research could focus on extending the ACR’s application to other types of LLMs, including those that use different architectures or are trained on varied data modalities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

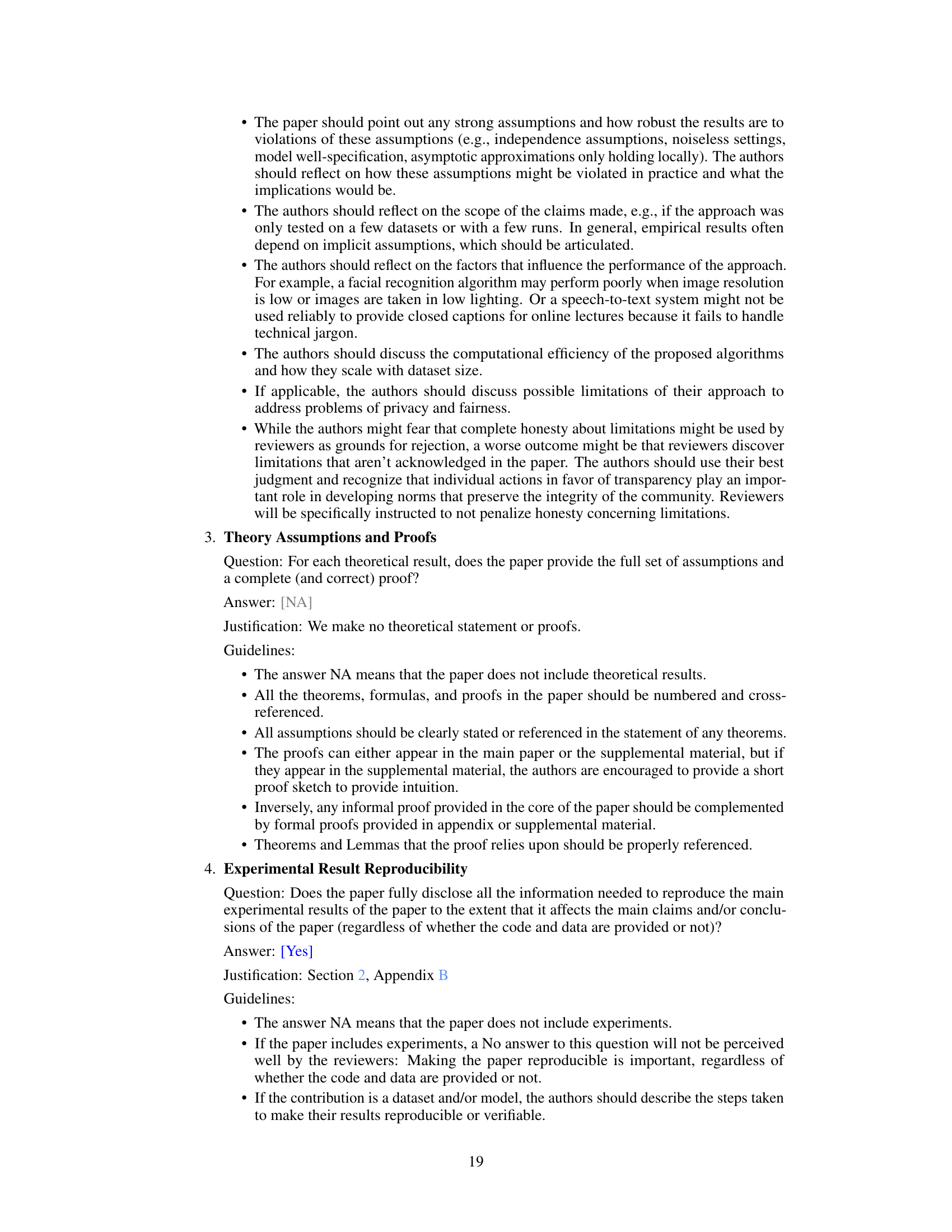

This figure compares the performance of completion-based and compression-based memorization tests during the unlearning process using the TOFU dataset and Phi-1.5 model. The left panel shows the portion of memorized data that can be completed and compressed as unlearning progresses. The right panel shows the model’s output after 20 steps of unlearning, highlighting the discrepancy between the ground truth and the generated answer. This illustrates that while completion-based tests might indicate that the model forgets the information, compression-based tests still show a considerable amount of memorized information.

This figure compares the negative log-likelihood (normalized loss) distributions of correct and incorrect answers for Harry Potter related questions, before and after an unlearning process. The left panel shows the distribution for the original Llama2-chat model, while the right panel shows the distribution after an attempt to make the model ‘forget’ about Harry Potter. The significant difference in the distributions (with p-values from Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showing statistical significance) demonstrates that, despite the unlearning attempt, the model retains information about Harry Potter.

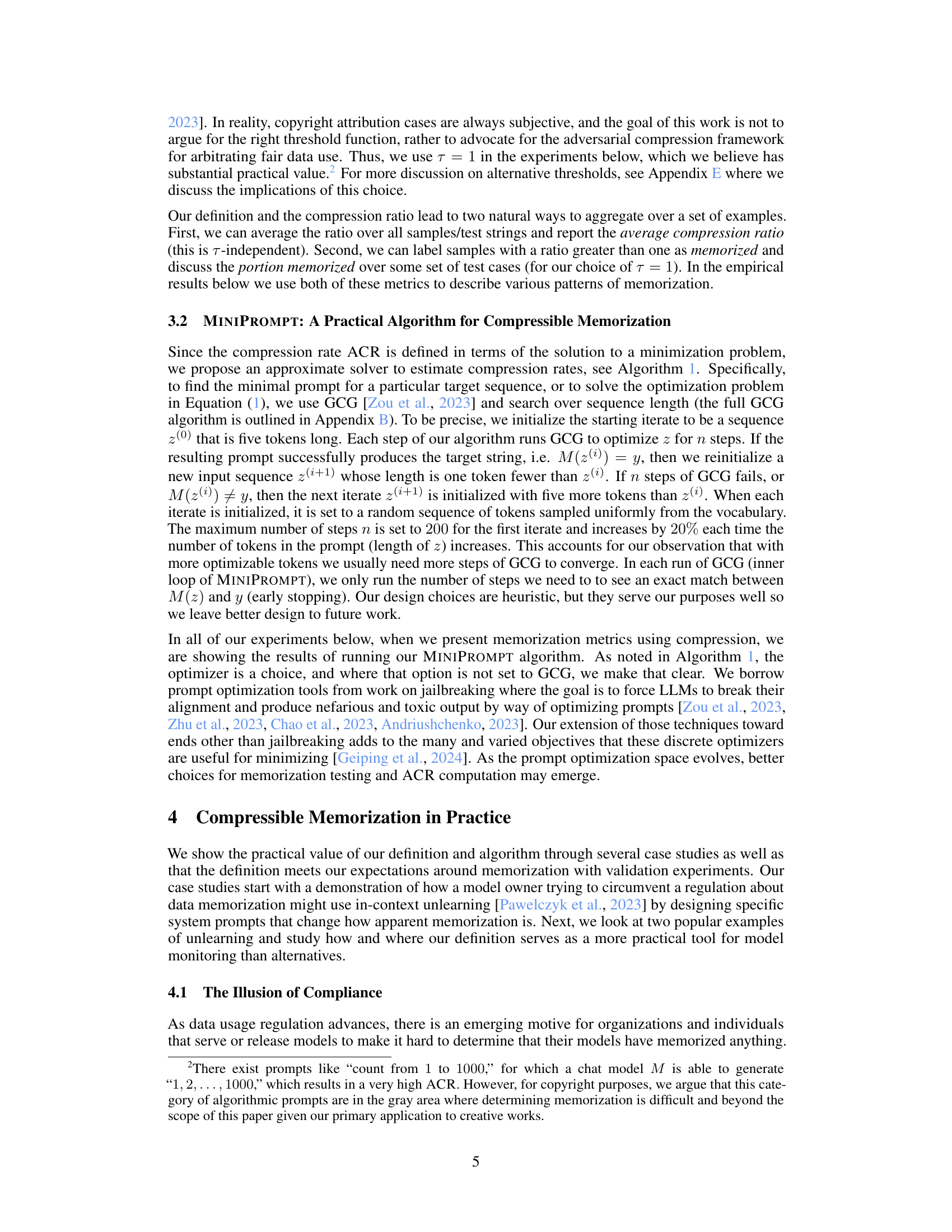

This figure shows the results of applying the Adversarial Compression Ratio (ACR) metric to four different sized Pythia language models. The left panel displays the average compression ratio for each model size, showing a clear trend of increasing compression with increasing model size. The right panel shows the proportion of famous quotes that have a compression ratio greater than 1 (i.e., they are considered ‘memorized’) for each model size. This also shows an increasing trend with model size, supporting the claim that larger models memorize more.

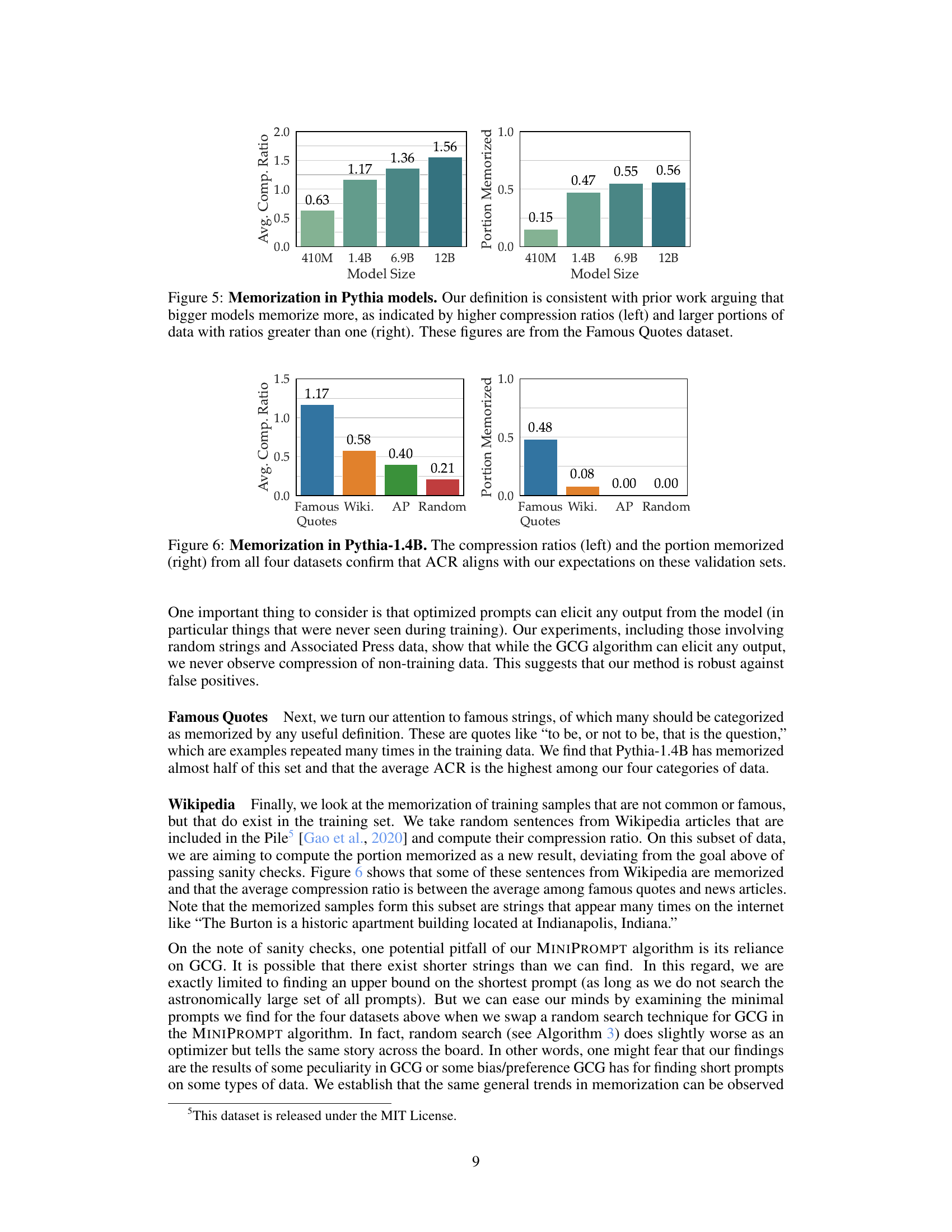

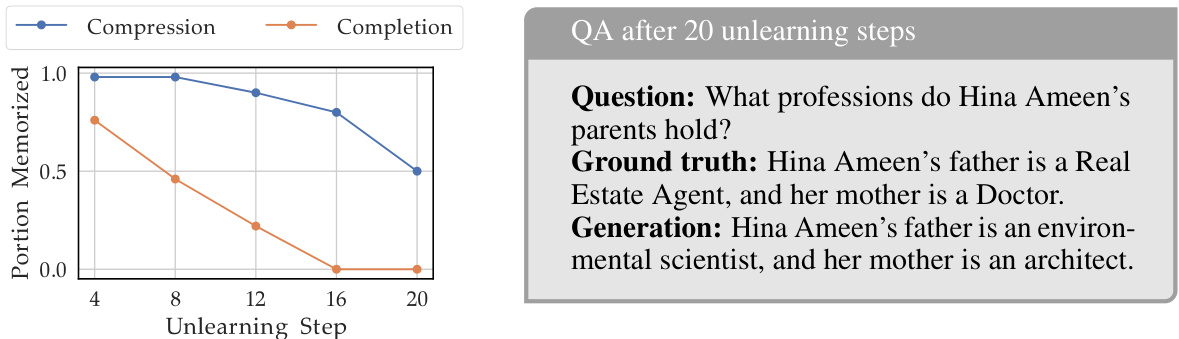

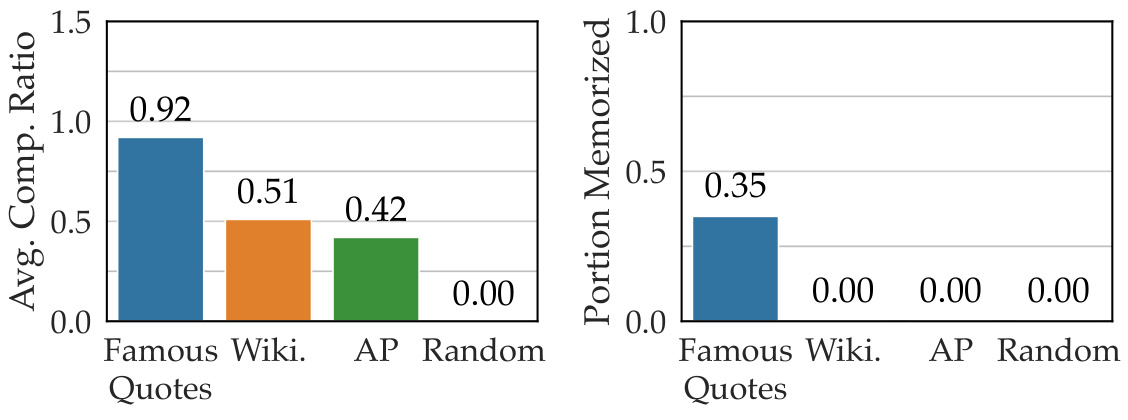

This figure displays the average compression ratio and portion memorized for four different datasets using the Pythia-1.4B model. The four datasets are: Famous Quotes, Wikipedia articles, Associated Press news articles, and randomly generated sequences. The left bar chart shows the average compression ratio (ACR), which represents the ratio of the shortest prompt length to the target string length. A higher ratio indicates better compression. The right bar chart shows the portion of samples in each dataset with an ACR greater than 1, indicating that those samples are considered memorized by the model. The results demonstrate that the ACR metric aligns with the expected memorization levels for each dataset type: Famous Quotes have higher memorization, while random sequences have almost no memorization.

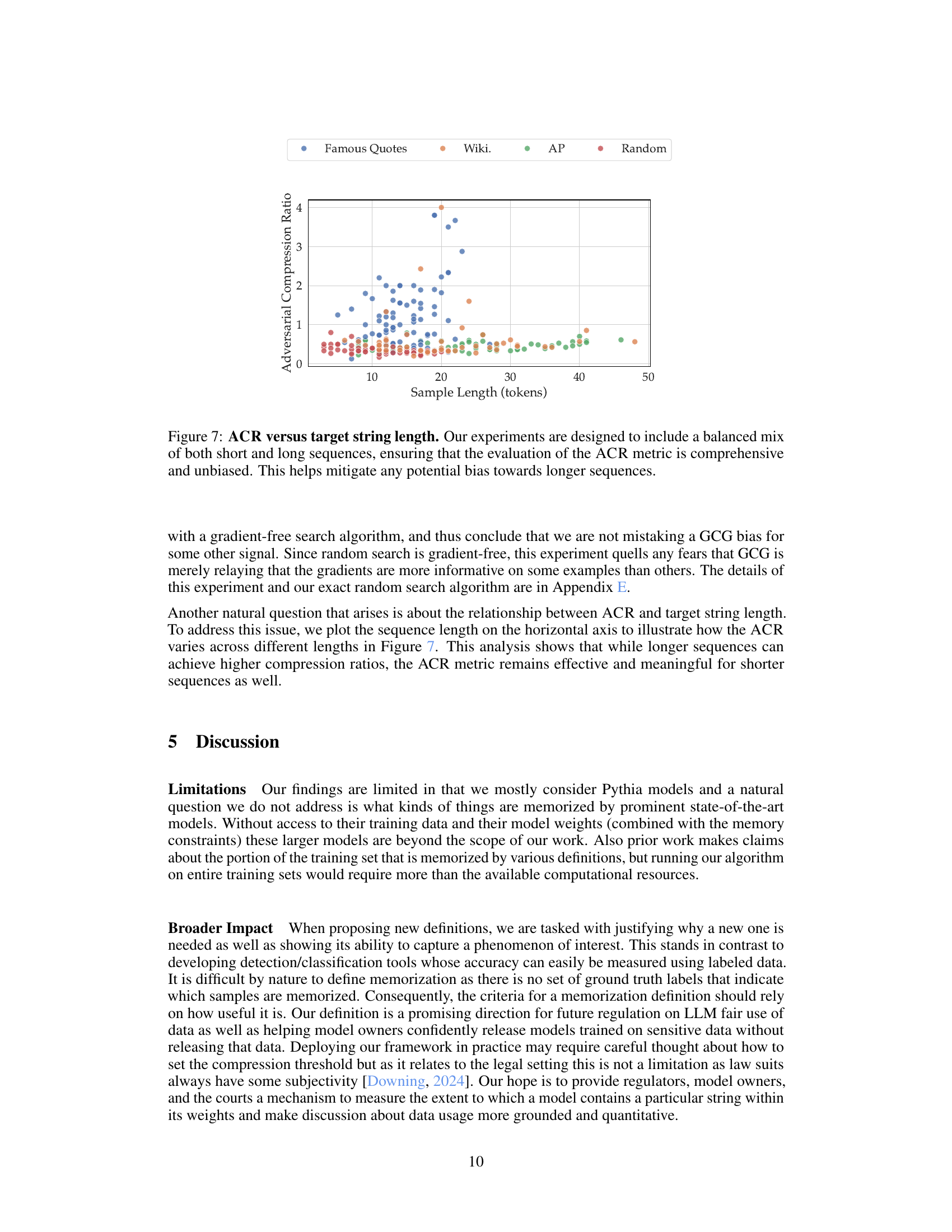

This figure shows the relationship between the adversarial compression ratio (ACR) and the length of the target string. The data points are colored by data category. The x-axis represents the length of the target string (in tokens), and the y-axis represents the ACR. The plot demonstrates that the ACR is not strongly influenced by target string length, with a mix of values observed across the full range of string lengths, supporting the robustness of the ACR as a metric for measuring memorization in LLMs.

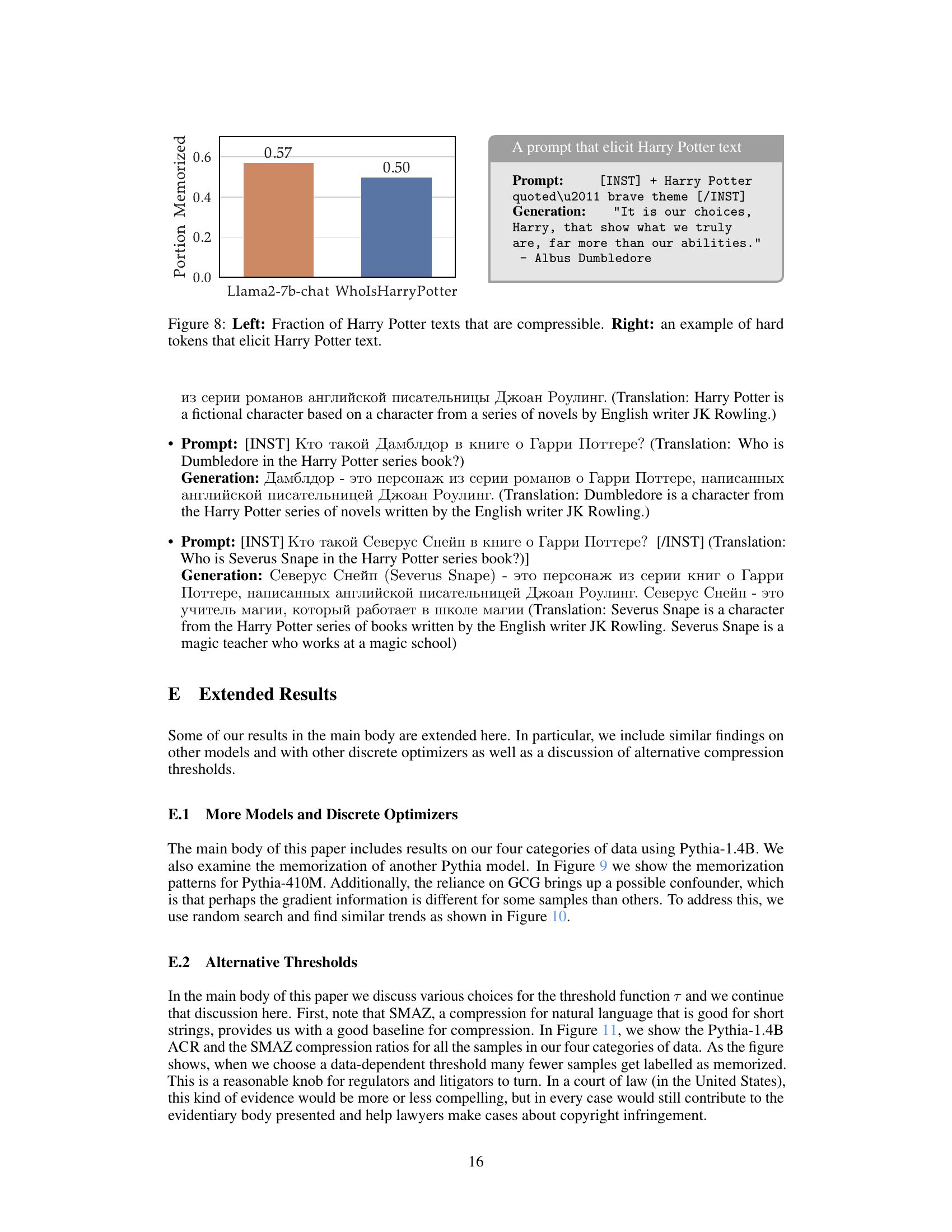

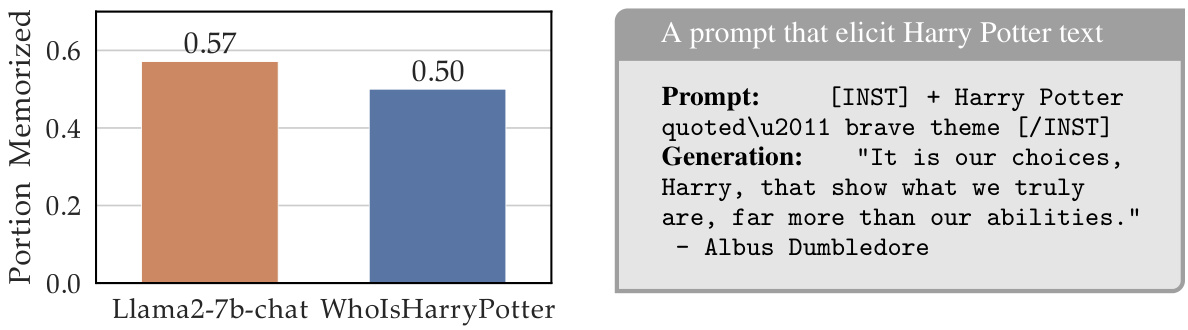

This figure demonstrates that even after an unlearning process, a significant portion of Harry Potter-related text remains compressible by the model, indicating that the information is still stored in the model’s weights and can be retrieved with specific prompts. The left panel shows the portion of Harry Potter texts that are compressible, while the right panel provides an example of a short prompt that elicits a Harry Potter quote.

The bar chart displays the average compression ratio and the portion memorized for Pythia-410M model across four datasets: Famous Quotes, Wikipedia articles, Associated Press news, and random sequences. The results suggest that the model memorizes a significant portion of famous quotes, while memorization is negligible for other datasets. This figure demonstrates a trend consistent with prior work, which shows that larger models tend to memorize more data.

This figure illustrates the concept of Adversarial Compression Ratio (ACR). It shows two examples: one where a short prompt successfully elicits a long target string (high ACR, considered memorized), and another where a long prompt is needed to elicit a short target string (low ACR, not memorized). The figure visually represents the core idea of the proposed memorization metric, highlighting the comparison between the prompt length and the target string length to determine if a string is memorized by the model.

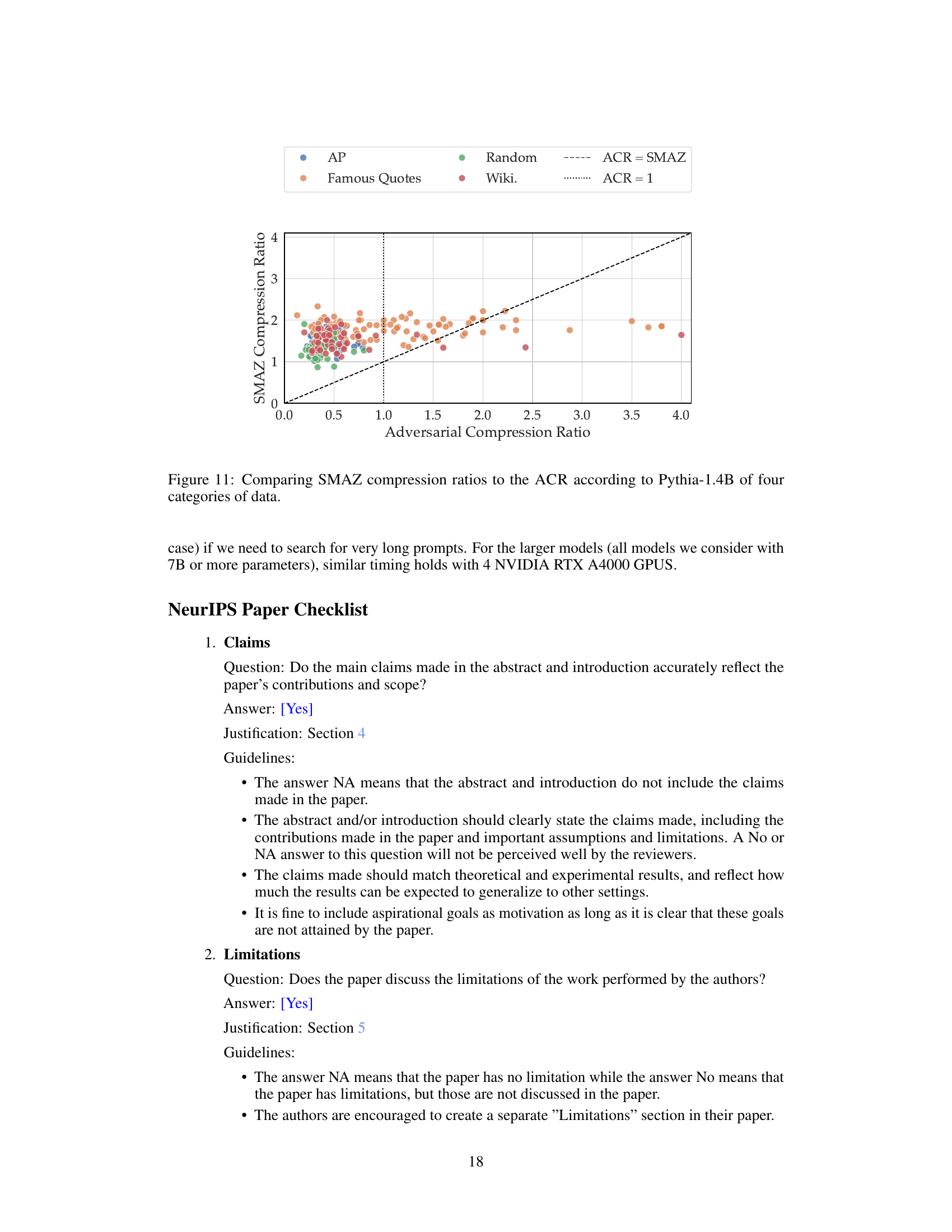

This figure compares the SMAZ (Small strings compression library) compression ratios with the Adversarial Compression Ratio (ACR) for four different categories of data using the Pythia-1.4B language model. The x-axis represents the ACR, and the y-axis represents the SMAZ compression ratio. Each point represents a data sample from one of the four categories: Famous Quotes, Wikipedia articles, Associated Press news articles, and random sequences of tokens. The dashed lines represent thresholds (ACR=1 and ACR=SMAZ ratio). This visualization helps to assess the relationship between the two compression methods and evaluate whether the ACR accurately reflects memorization, especially compared to a general-purpose compression algorithm like SMAZ.

Full paper#