↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

High-dimensional data analysis often relies on spectral algorithms like Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR). However, KRR’s performance can be limited, especially for smooth functions, failing to reach the optimal convergence rates predicted by information theory. This phenomenon, known as the saturation effect, has been extensively studied but lacks rigorous proof in high-dimensional settings.

This research addresses this gap by proving the saturation effect of KRR in high dimensions. The authors achieve this using an improved minimax lower bound and demonstrate that gradient flow with early stopping attains the lower bound. Further analysis of a large class of spectral algorithms reveals the exact convergence rates, exhibiting periodic plateau behavior and polynomial approximation barriers. This comprehensive analysis fully characterizes the saturation effects of spectral algorithms in high-dimensional settings, providing valuable insights for algorithm design and theoretical understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it rigorously proves the saturation effect of Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) in high dimensions, a phenomenon observed for two decades but lacking rigorous proof. This significantly impacts the understanding and development of spectral algorithms in machine learning, particularly concerning the choice of algorithms when dealing with smooth regression functions and high-dimensional data. The findings open avenues for improved algorithm design and theoretical analysis.

Visual Insights#

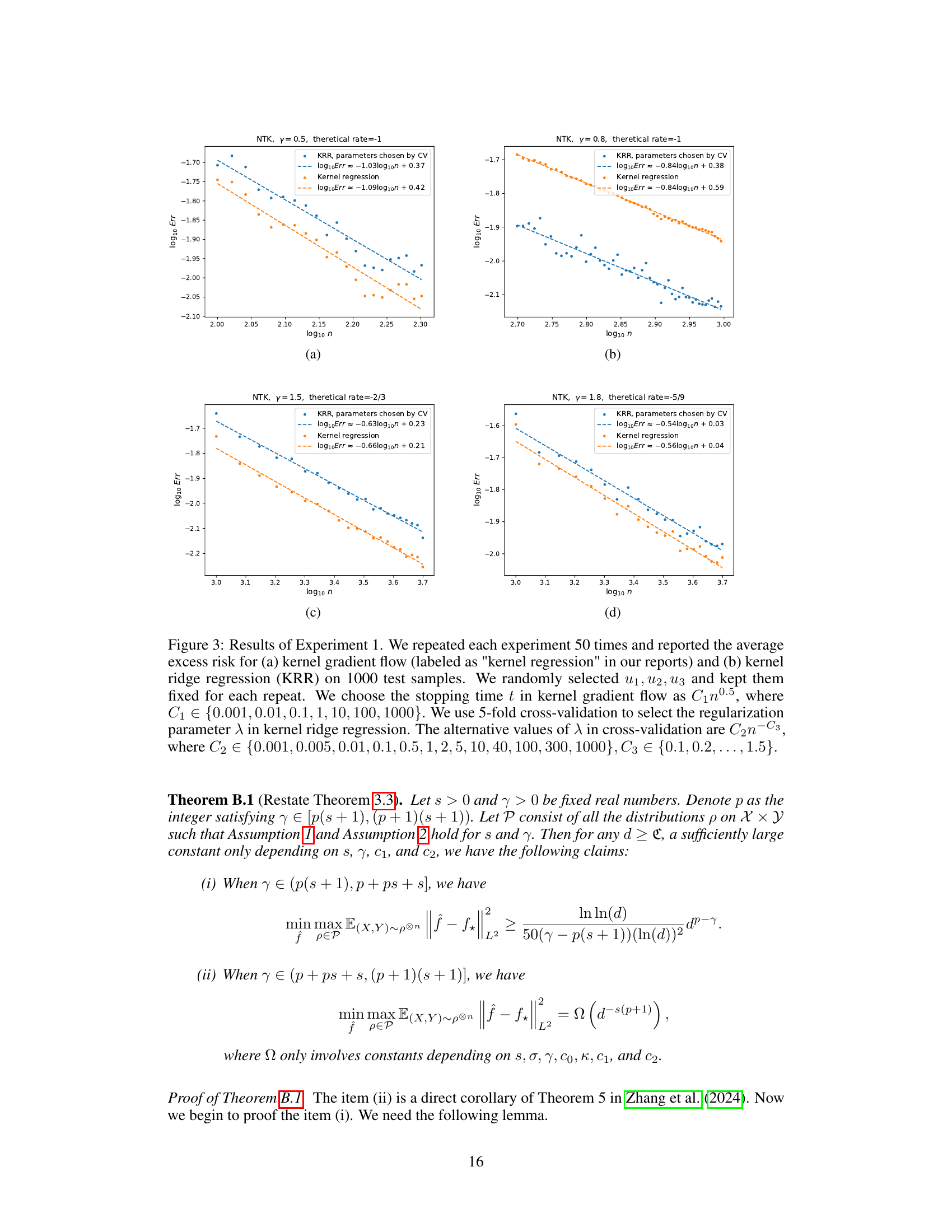

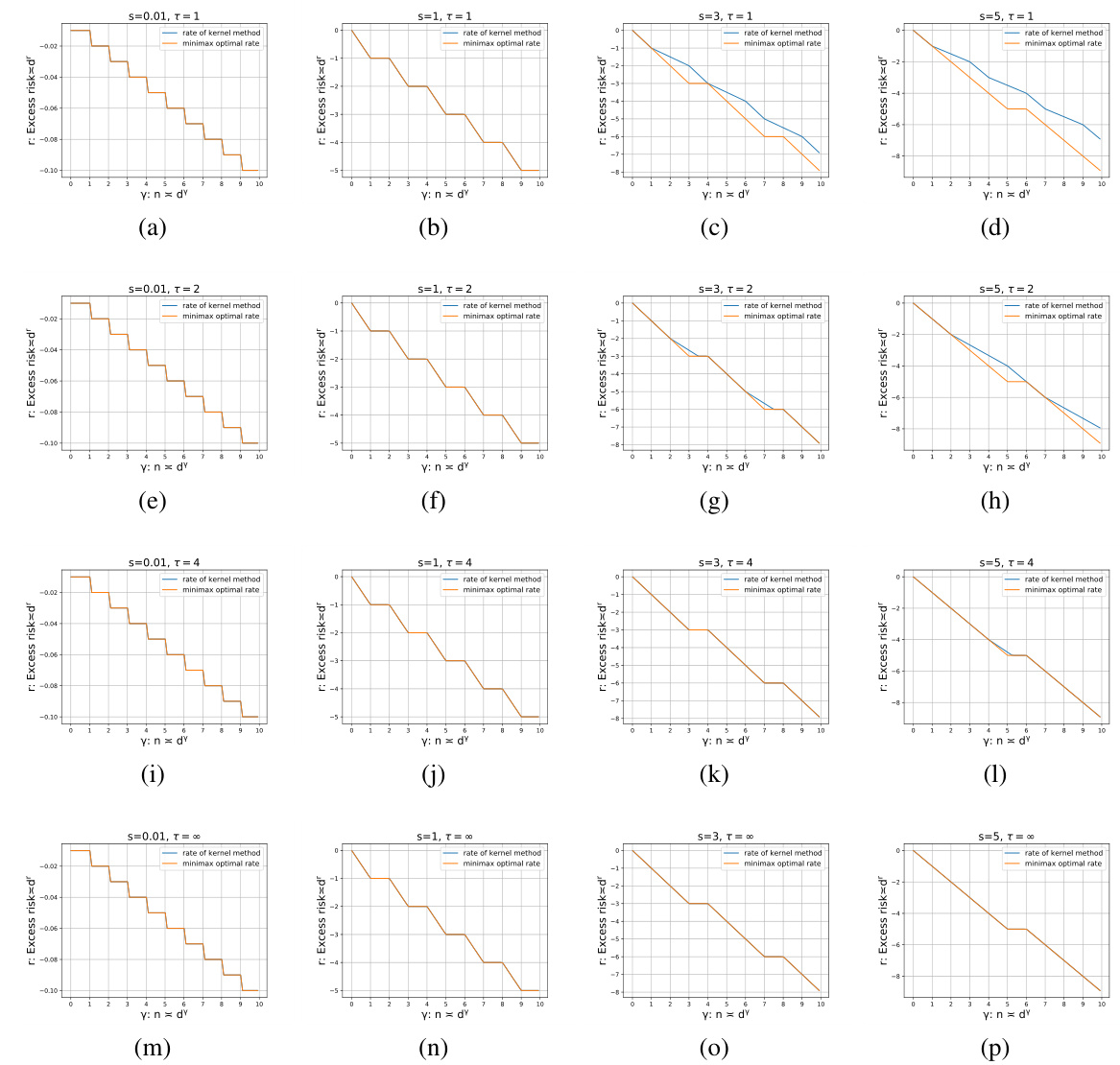

This figure shows the convergence rates of spectral algorithms with qualification τ=2 for four different source conditions (s = 0.01, 1, 3, 5). Each subplot shows the convergence rate curves for kernel methods against the minimax optimal rate, as a function of the asymptotic scaling γ (n=dγ). The plots illustrate several key phenomena observed in large-dimensional spectral algorithms including the polynomial approximation barrier, periodic plateau behavior, and the saturation effect. The x-axis represents the asymptotic scaling, and the y-axis represents the convergence rate of the excess risk.

In-depth insights#

Spectral Saturation#

Spectral saturation, a phenomenon observed in spectral algorithms like kernel ridge regression, describes the limitation where increasing the smoothness of the target function beyond a certain threshold does not result in improved estimation accuracy. This is because the algorithm’s performance is bound by its inherent spectral properties, specifically the rate at which the eigenvalues decay. While spectral methods excel in leveraging function smoothness, overly smooth functions saturate the algorithm’s ability to exploit that smoothness; yielding convergence rates that fail to attain the information-theoretical lower bound. Understanding spectral saturation is critical for algorithm selection, especially in high-dimensional settings where data scarcity exacerbates the limitations. Research into this area focuses on developing modifications to spectral algorithms that mitigate saturation effects, such as employing gradient flow methods or carefully selecting regularization parameters. The consequences of spectral saturation are convergence rates that plateau despite increasing data or computational resources, hindering the effectiveness of the algorithm.

High-D Effects#

The heading ‘High-D Effects’ suggests an exploration of phenomena arising in high-dimensional data analysis, specifically concerning the behavior of spectral algorithms. A key aspect would likely involve understanding how the performance of these algorithms changes as the dimensionality (d) of the data increases, perhaps relative to the sample size (n). The discussion might reveal deviations from theoretical predictions made for lower dimensions, highlighting the challenges posed by high dimensionality. For instance, there might be a focus on the impact of high dimensionality on convergence rates, generalization error, and the computational cost of spectral methods. The analysis could also compare the performance of different spectral algorithms in high dimensions, noting which ones are more robust or exhibit different forms of ‘saturation effects’ than those seen in lower dimensions. A crucial element would be identifying the critical relationships between d and n, and how these affect algorithm performance. It’s likely the analysis identifies instances of ‘benign overfitting’ or other unusual high-dimensional behaviors.

Minimax Optimality#

Minimax optimality, a central concept in statistical decision theory, signifies achieving the best possible performance under the worst-case scenario. In the context of this research paper, it likely refers to the optimal convergence rate of spectral algorithms in high-dimensional settings. The authors aim to demonstrate that certain algorithms achieve the minimax optimal rate, meaning they perform as well as any other algorithm under the least favorable conditions. This is particularly important in high dimensions where classical theoretical guarantees often fail. Demonstrating minimax optimality provides strong evidence of the algorithm’s robustness and efficiency. The analysis might involve proving both upper and lower bounds on the convergence rate, showcasing that the developed algorithm’s rate matches the theoretical limit. The paper likely focuses on how the algorithm’s performance scales with the dimensionality (d) and sample size (n), showing the algorithm’s resilience to the curse of dimensionality, a significant contribution in large-scale machine learning.

Convergence Rates#

Analyzing convergence rates in machine learning reveals crucial insights into algorithm efficiency and generalization performance. Faster convergence indicates quicker model training, while slower rates might suggest challenges in optimization. Examining convergence rates across different algorithms, hyperparameters, and datasets helps determine optimal settings and identify potential bottlenecks. Theoretical analysis provides rigorous bounds on convergence speeds, offering valuable guidance for algorithm design and performance prediction. However, practical considerations often deviate from theoretical results due to factors like data noise, model complexity, and computational limitations. Thus, empirical studies are vital in evaluating convergence behavior in realistic settings. Careful analysis of both theoretical and empirical results helps researchers understand the trade-offs between model training speed and generalization capacity, leading to more robust and effective machine learning models.

Improved Bounds#

The concept of “Improved Bounds” in a research paper typically refers to advancements in establishing tighter or more accurate estimations of a particular quantity. This could involve refining existing upper and lower bounds, or perhaps deriving entirely new ones. Improved bounds often lead to stronger theoretical results because they reduce uncertainty and provide a more precise understanding of the phenomenon being studied. In the context of a research paper, the specific meaning will depend on the field. For example, in machine learning, it might involve improved error bounds for a learning algorithm, offering a more accurate prediction of its generalization performance. In other areas, it could refer to tighter constraints on the solution of a mathematical problem or improved estimations of physical constants. The significance of “improved bounds” lies in their ability to enhance the precision of theoretical analyses and guide future research efforts by identifying areas where further exploration may be particularly fruitful. Ultimately, improved bounds represent a significant step forward in understanding the underlying problem.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure presents a graphical illustration of the convergence rates of several spectral algorithms (KRR, iterated ridge regression, kernel gradient flow) in large dimensions. It shows how these rates change depending on the smoothness of the regression function (source condition s) and the relationship between the sample size and dimension (asymptotic scaling γ). The figure highlights the polynomial approximation barrier, periodic plateau behavior, and saturation effect observed in large-dimensional spectral algorithms.

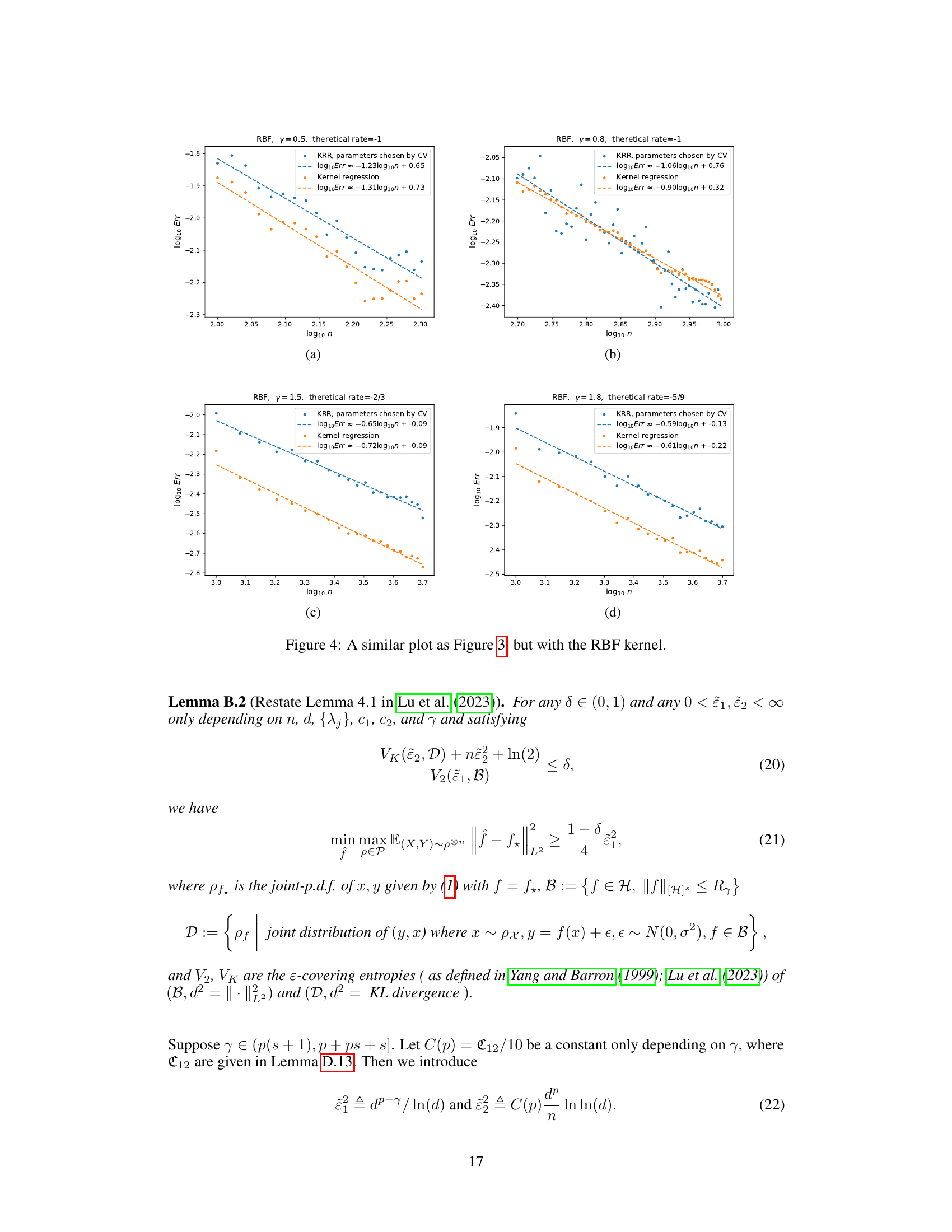

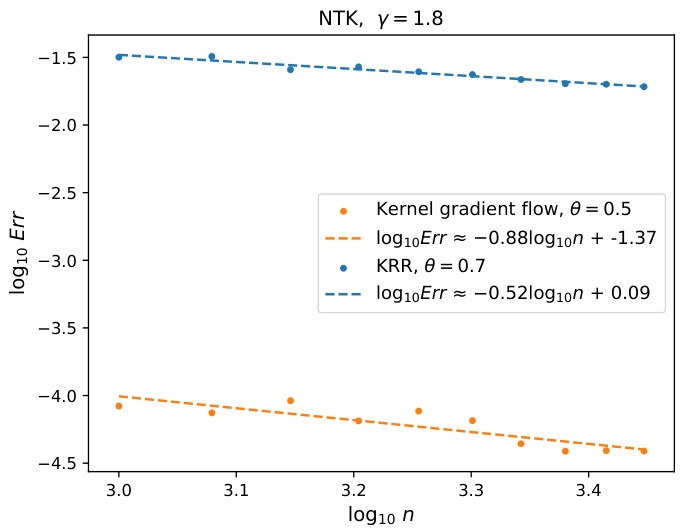

This figure shows the results of Experiment 1, comparing kernel gradient flow and kernel ridge regression. The experiment was repeated 50 times with 1000 test samples. The stopping time for gradient flow and regularization parameter for KRR were tuned using different methods. The figure shows the convergence rate of the excess risk for each method with different values of γ (n = dγ).

The figure displays the results of Experiment 1, which compares the performance of kernel gradient flow and kernel ridge regression (KRR) in terms of excess risk. The experiment was repeated 50 times, and the average excess risk was calculated for both algorithms using 1000 test samples. The stopping time t for kernel gradient flow was varied, and 5-fold cross-validation was used to select the regularization parameter λ for KRR. Four subfigures (a-d) are presented, each corresponding to a different value of γ (n=d^γ), showcasing the convergence rates of both algorithms under different scaling parameters. The x-axis represents the logarithmic scale of sample size (n), and the y-axis represents the logarithmic scale of excess risk.

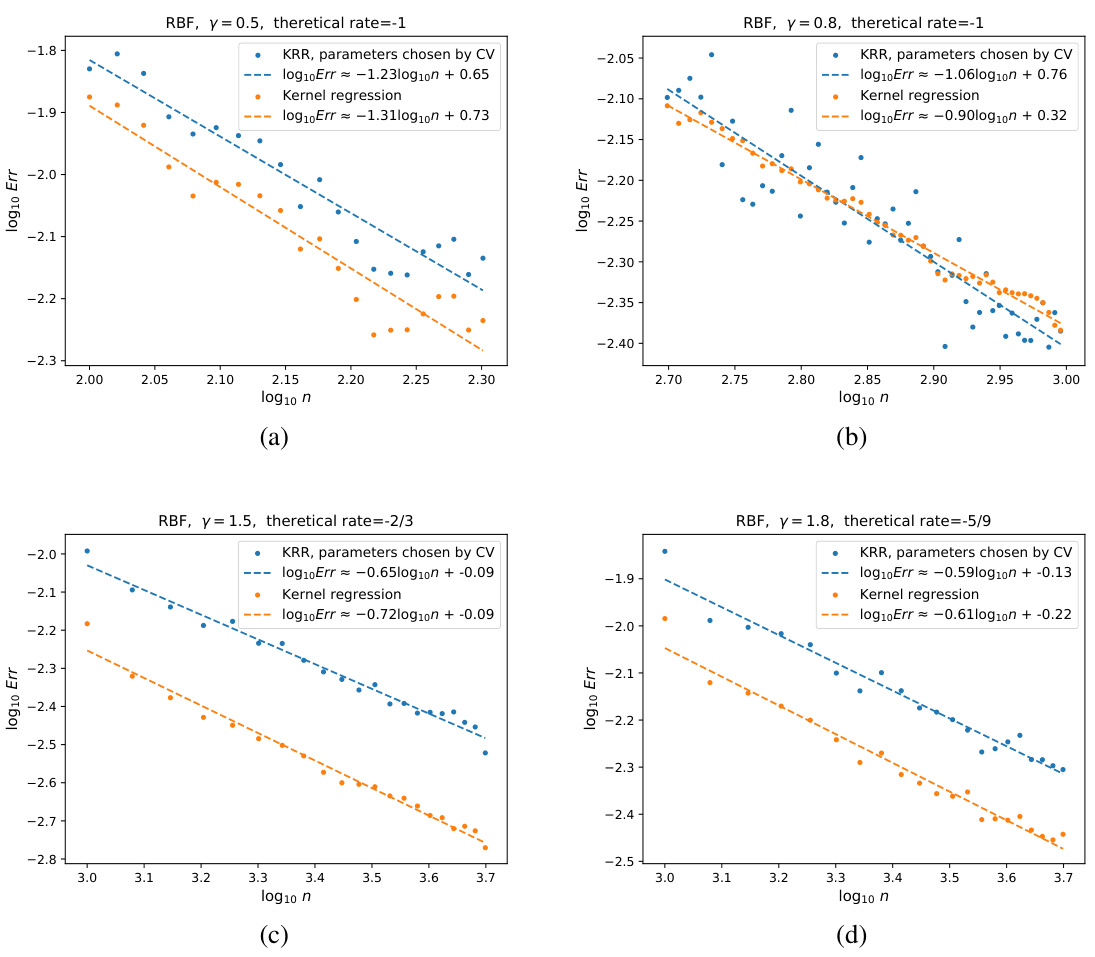

This figure shows the results of Experiment 2, which aimed to illustrate the saturation effect of KRR when s > 1. Two kernels were used: NTK and RBF. The x-axis represents the log10 of the sample size (n), and the y-axis represents the log10 of the excess risk. The figure compares the convergence rates of kernel gradient flow and KRR for a regression function with s = 1.9. The lines represent the fitted convergence rates. The results confirm that when the regression function is sufficiently smooth (s > 1), KRR’s convergence rate is slower than that of kernel gradient flow.

Full paper#