↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications, like healthcare and education, benefit from personalized reinforcement learning (RL) models. However, individual characteristics often influence state transitions in ways that are not directly observable, creating a significant challenge. This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on identifying these hidden, individual-specific factors that affect state transitions. It does so by introducing a new framework that explicitly incorporates these latent factors, ensuring that the model considers individual differences when learning policies.

The authors propose a two-stage approach: First, a novel framework, Individualized Markov Decision Processes (iMDP), is developed to model individualized decision-making by integrating latent individual-specific factors into state-transition processes. This enables them to prove the identifiability of the latent factors under certain conditions. Second, a generative model is designed to estimate these factors from observed data, allowing for accurate and effective policy learning for each individual. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated through extensive experiments on various datasets, showing its potential to improve the performance and personalization of RL policies in various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on individualized reinforcement learning and related fields. It offers theoretical guarantees for identifying latent factors affecting state transitions, which is a significant challenge in personalizing RL policies. The proposed method is practical, and the findings open up new avenues for research in personalized healthcare, education, and other domains. Its novel theoretical framework, practical algorithms, and real-world applications make it highly relevant to various fields.

Visual Insights#

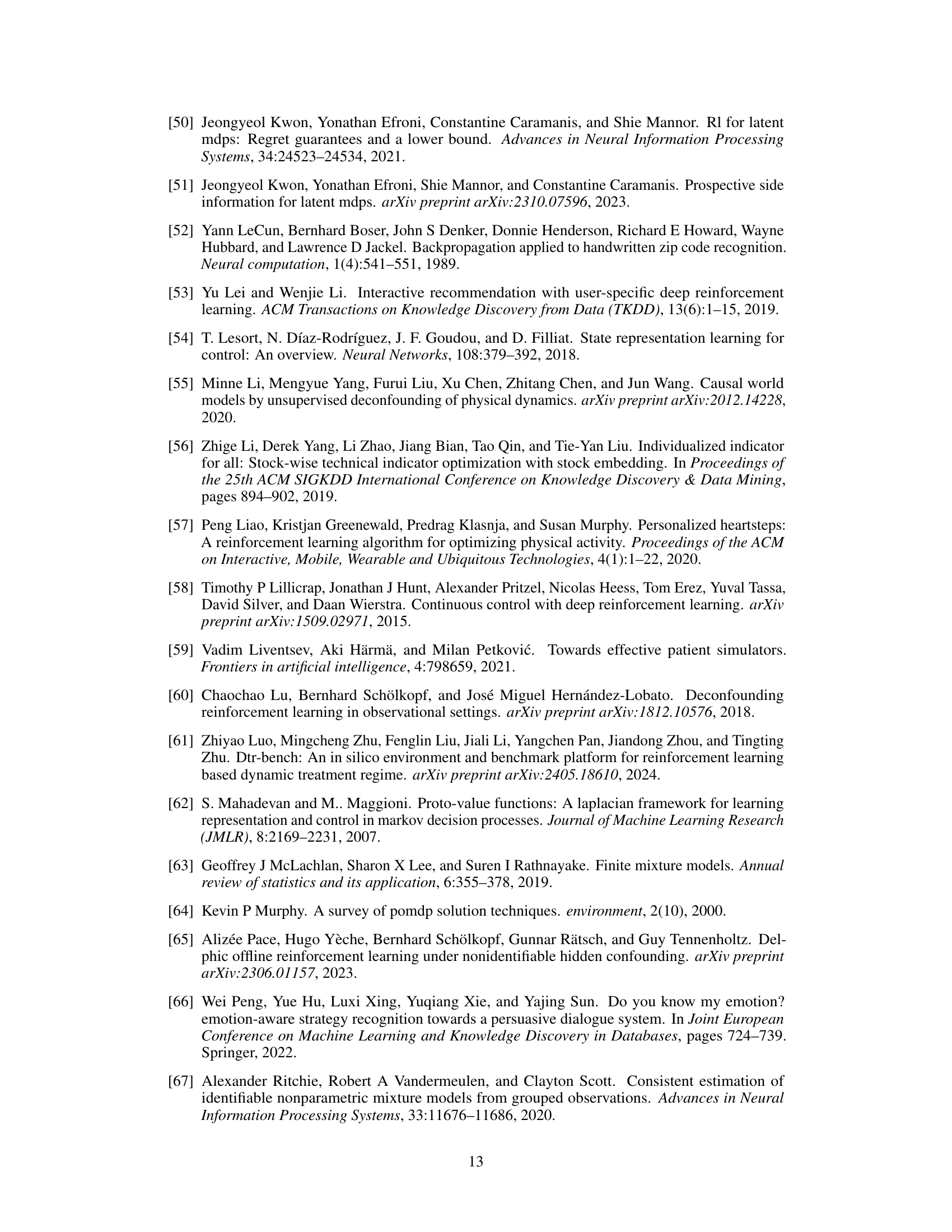

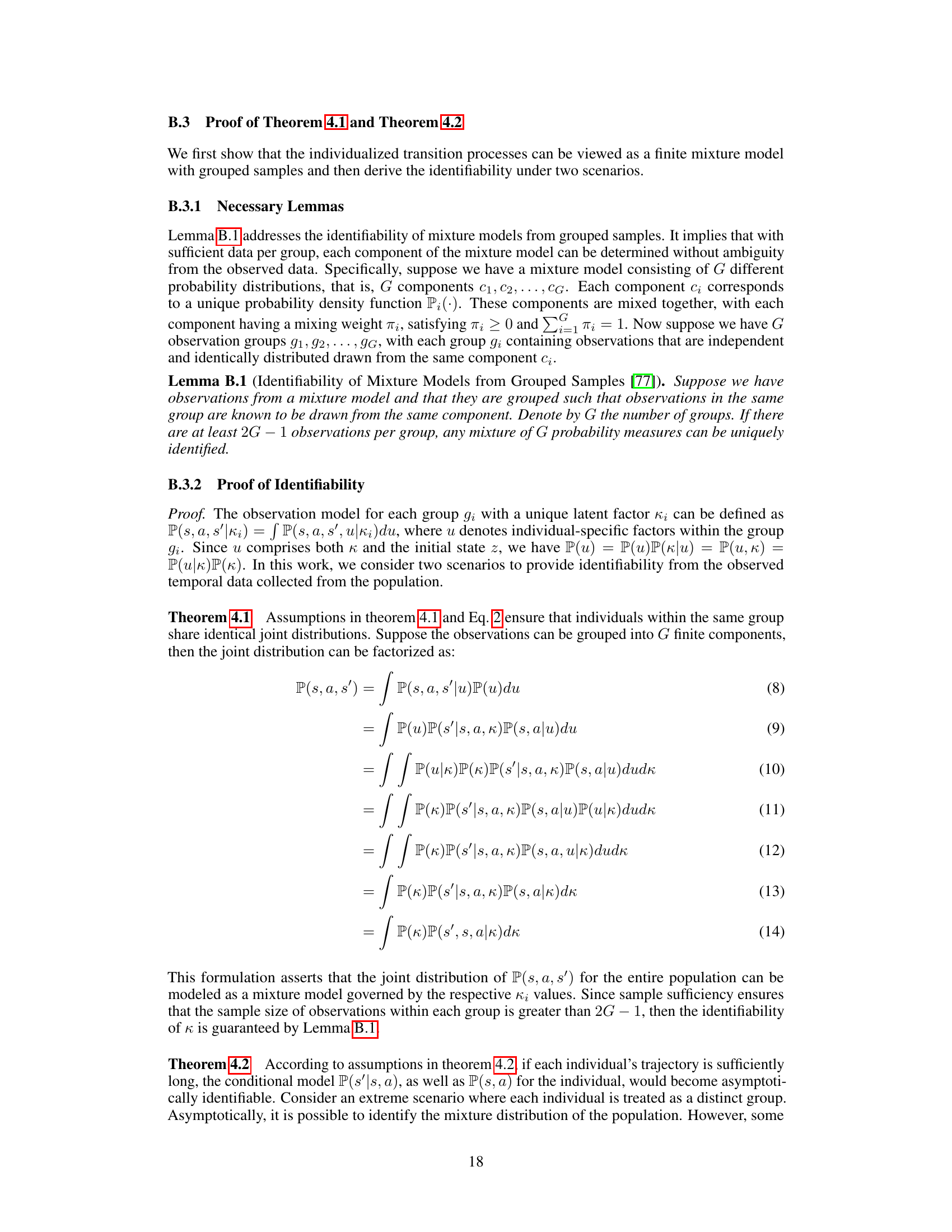

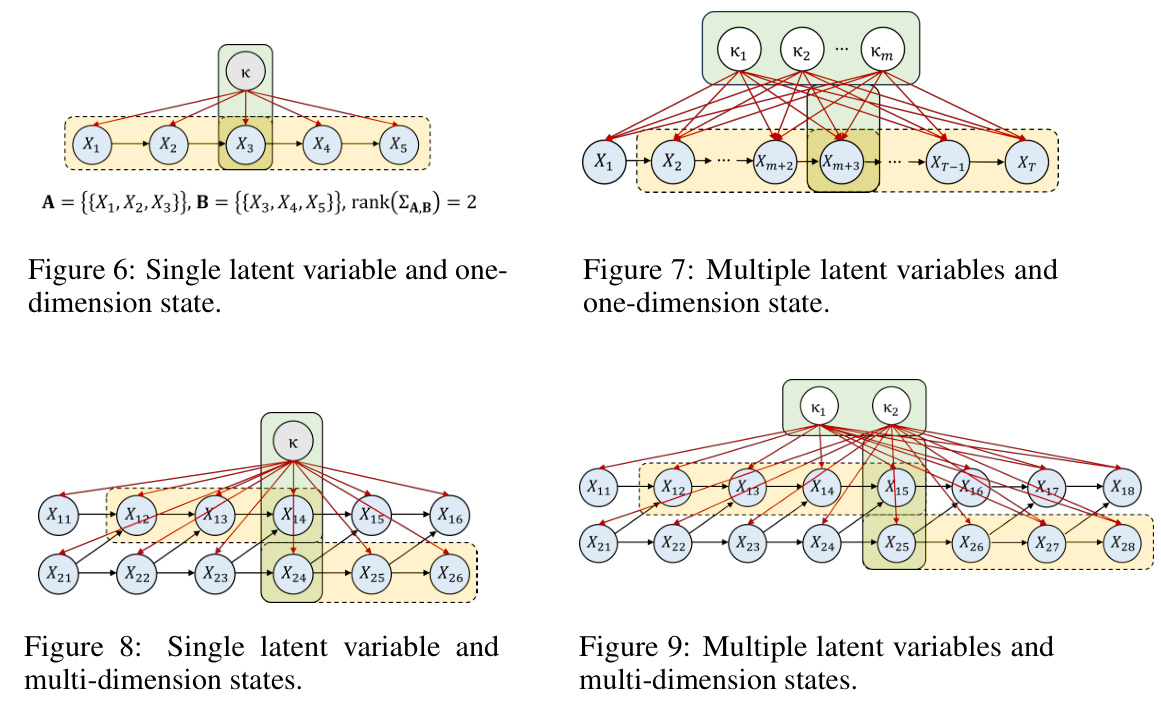

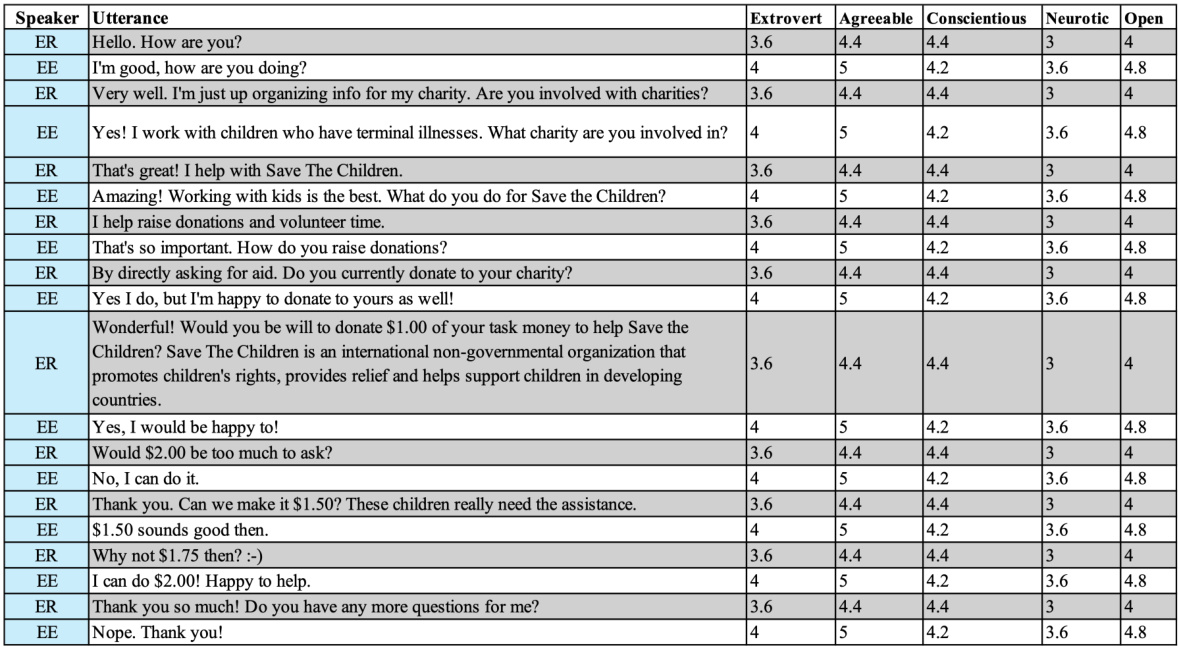

This figure compares three different state transition process models. (a) shows an individualized MDP (iMDP) model where each individual m has its own initial state (s_m0), individual-specific factor (κ_m), and state-transition process (T_m). Latent factors influence state transitions. (b) depicts a latent causal process model where unobserved latent variables (Z_t) causally influence observed state transitions over time. (c) illustrates a factored non-stationary MDP model with time-varying latent factors (θ_t) that influence both states and actions. This model is distinct from the iMDP in its allowance for changing latent factors, reflecting potential changes in individual characteristics over time. The grey color highlights the latent variables in each model.

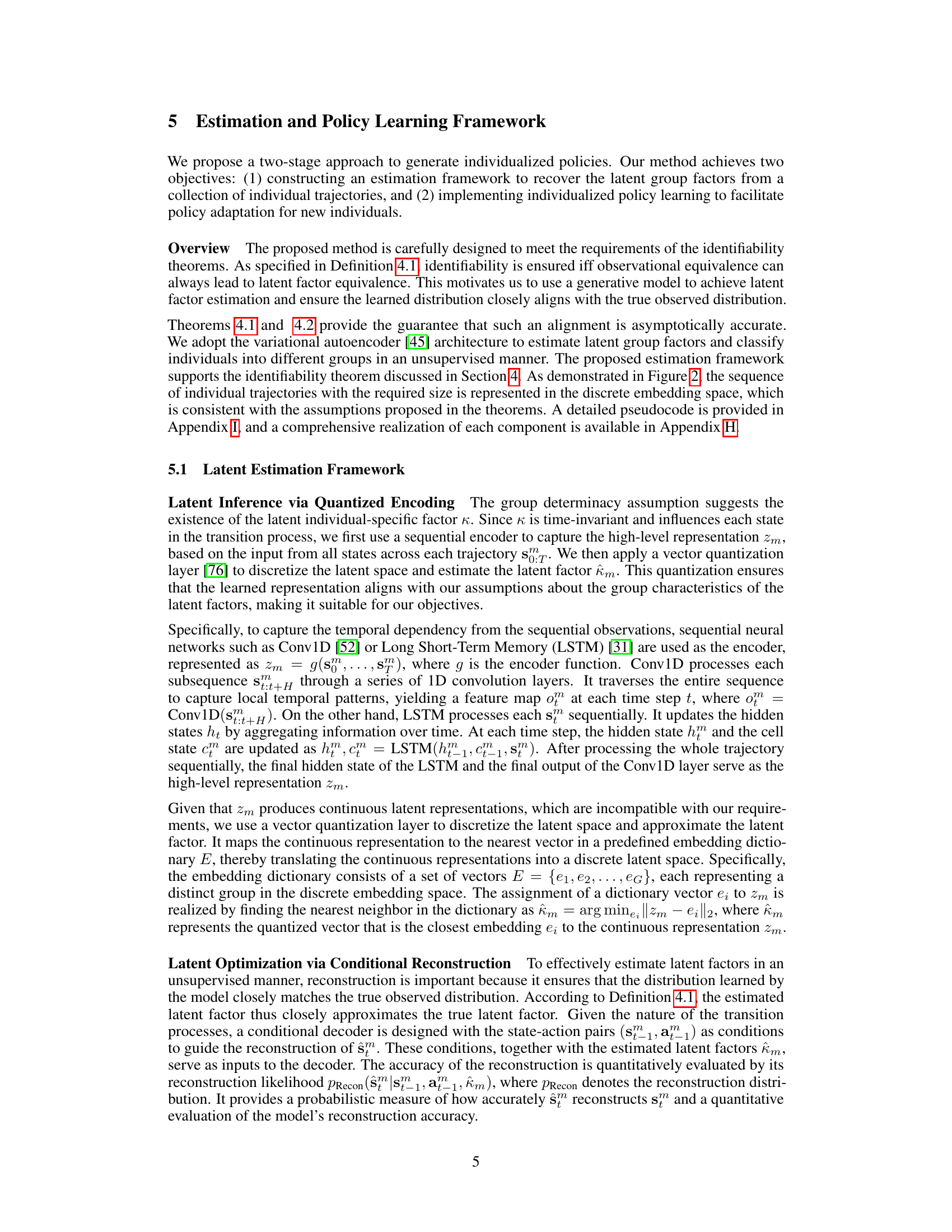

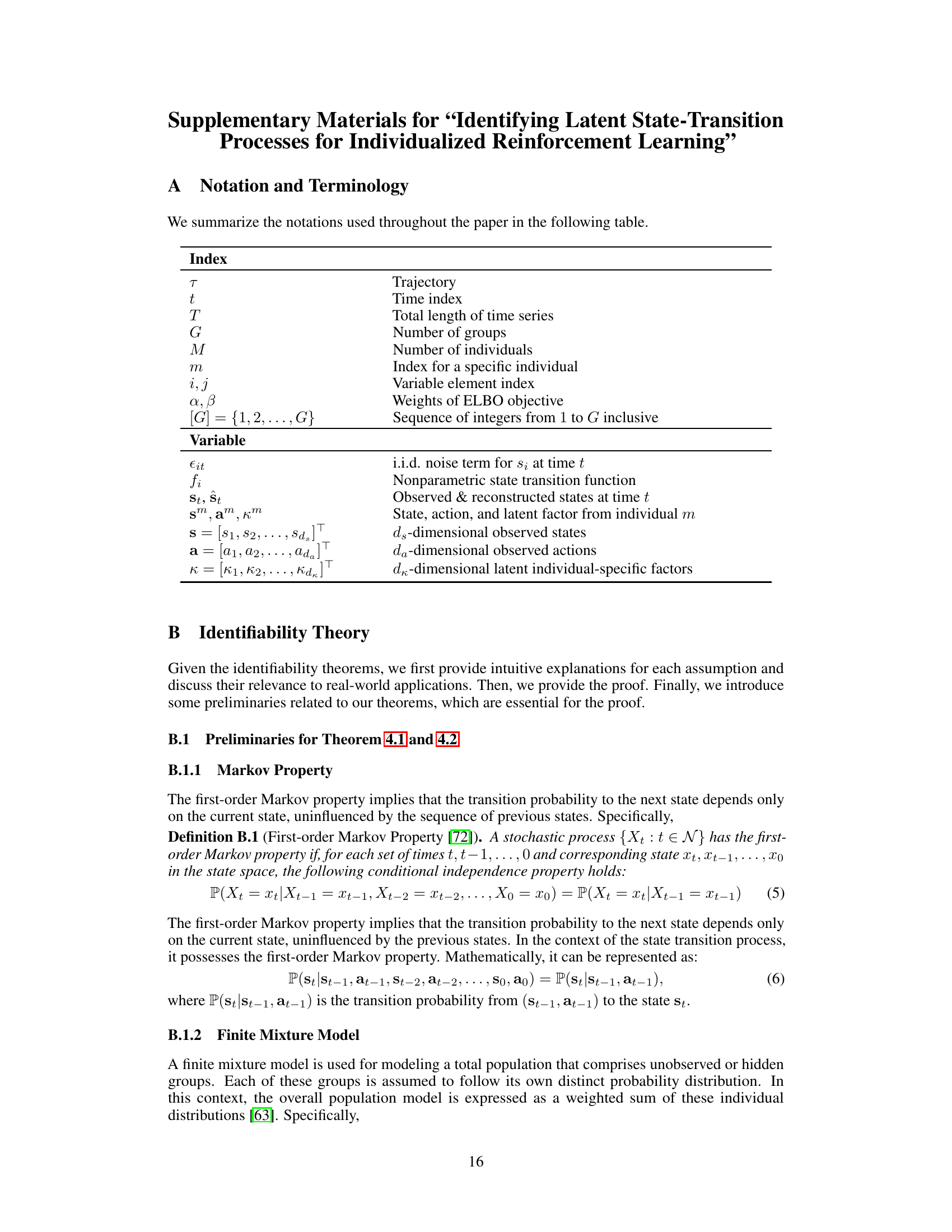

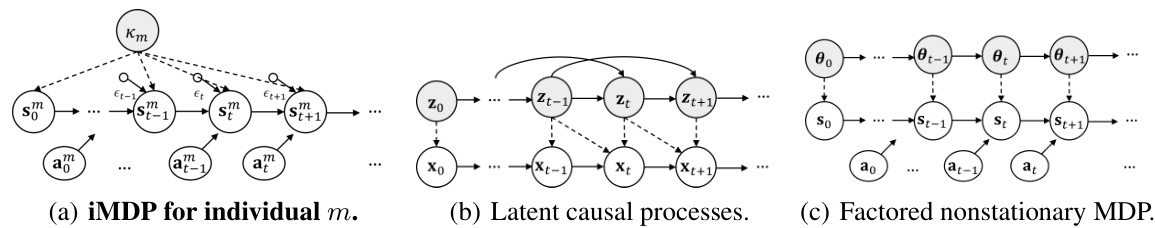

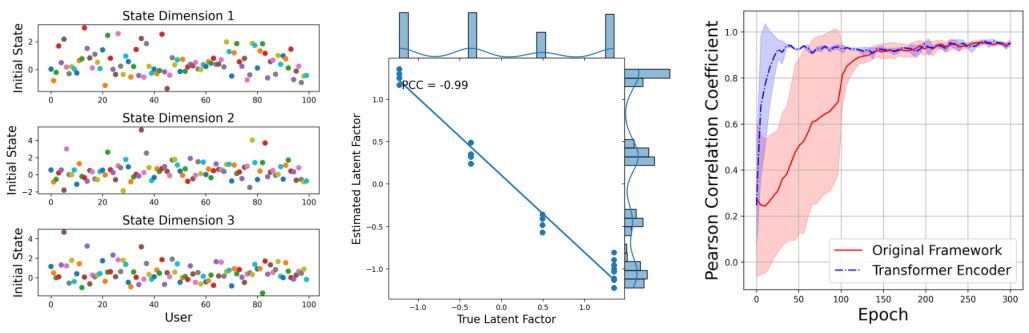

This table presents the ablation study results showing the impact of different components on the performance of the latent estimation framework. It compares three models: a basic model using only quantized encoding and two augmented models with sequential encoders and a noise estimator, respectively. For each model, the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) and bias between the true latent factors and their estimated counterparts are reported. The results demonstrate that the incorporation of sequential encoders and noise estimators significantly improves the performance of the latent estimation framework, resulting in higher PCC values and lower bias.

In-depth insights#

Latent Factor ID#

Identifying latent factors is crucial for individualized reinforcement learning because individual differences significantly influence state transition processes. A key challenge is that these factors are often unobservable. The proposed method addresses this by establishing the identifiability of these latent factors, even when they are time-invariant and influence state transitions in a non-linear manner. This is achieved through a novel framework that leverages group information from observed state-action trajectories, providing a theoretical basis for the identification process. The identifiability results hold for both finite and infinite numbers of latent factors, covering various scenarios and enhancing the practical applicability of the method. A practical algorithm is presented for estimating the latent factors, integrating a quantized encoding technique and a conditional reconstruction approach to capture the time-invariant nature of the latent factors effectively. The algorithm’s performance is validated empirically, highlighting its effectiveness in identifying latent factors across diverse datasets and improving the accuracy of individualized policies.

iMDP Framework#

The iMDP (Individualized Markov Decision Process) framework presents a novel approach to reinforcement learning by explicitly modeling individual-specific latent factors that influence state transitions. Its core innovation lies in integrating these latent factors, denoted as κ, directly into the state-transition process. This differs significantly from standard RL models, which often treat individuals as homogenous entities. The framework is not just a conceptual advancement but also provides theoretical guarantees on the identifiability of these latent factors under specific conditions, either by leveraging group determinacy or by imposing functional constraints. This theoretical foundation is crucial because it demonstrates the possibility of recovering individual-specific characteristics from observed data, a key challenge in individualized RL. Further, the iMDP framework incorporates a practical generative method that effectively learns these latent processes from observed state-action trajectories. The two-stage approach (latent factor estimation and policy learning) is a pragmatic implementation of the theoretical framework, offering a robust path to individualized policy creation and adaptation. The framework’s significance lies not only in its theoretical contributions but also in its potential applications across diverse domains requiring personalized RL policies, thereby paving the way for more effective individualized interventions.

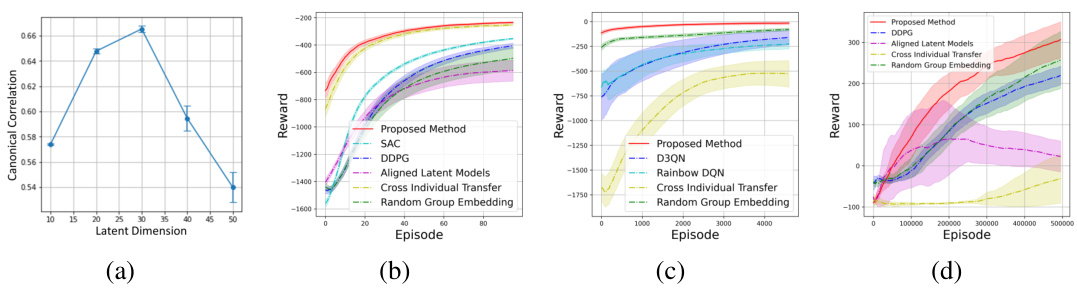

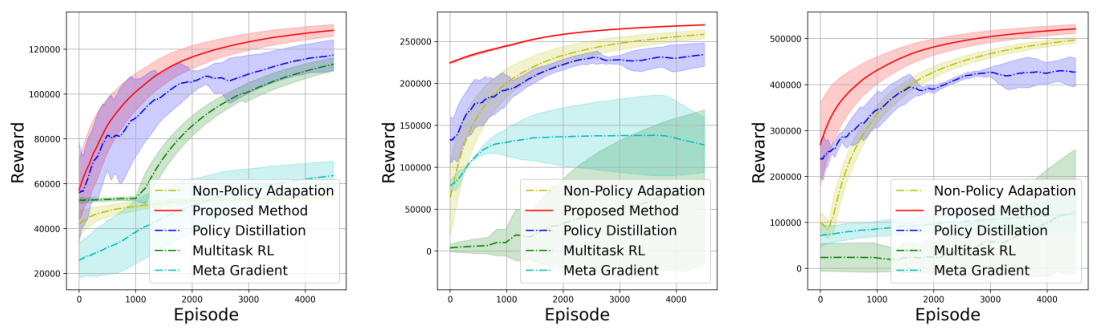

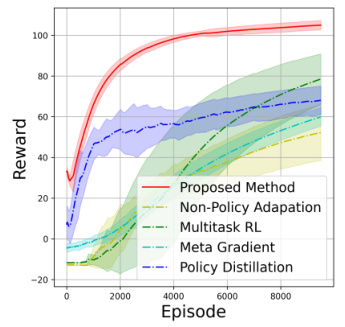

Policy Learning#

The research paper’s ‘Policy Learning’ section likely details how the learned latent factors are integrated into reinforcement learning (RL) for individualized policy optimization. It likely begins by describing the methodology for training RL agents, which might involve techniques like Q-learning or actor-critic methods adapted to leverage the estimated latent group factors. The process would likely involve augmenting the state representation with the latent factor, thereby enabling the RL agent to learn distinct policies tailored to each individual’s characteristics. A key aspect is how new individuals are incorporated. The algorithm likely leverages the estimated group membership to initialize the policy for new individuals using a pre-trained policy specific to their group, significantly improving efficiency over training from scratch. The paper likely presents evaluation metrics such as jumpstart (initial performance improvement) and cumulative reward to demonstrate the efficacy of this individualized approach in adapting to new individuals and achieving superior performance compared to non-individualized strategies.

Real-world Tests#

A dedicated ‘Real-world Tests’ section in a research paper would ideally demonstrate the practical applicability and generalizability of the presented methodology beyond simulated or controlled environments. It should feature experiments using realistic, complex datasets, potentially obtained from diverse sources, reflecting real-world complexities and challenges. Rigorous evaluation metrics suitable for such data should be applied, going beyond simple accuracy measures to encompass factors like robustness, efficiency, and fairness. The results should be carefully analyzed to highlight strengths and limitations, including potential biases or failure modes encountered in real-world settings. A strong ‘Real-world Tests’ section provides crucial validation of the research, demonstrating its value and potential impact. It effectively bridges the gap between theoretical claims and practical utility, providing evidence for broader adoption and informing future improvements. The inclusion of case studies or detailed descriptions of the tested settings would further enhance the credibility and understanding of the real-world applications.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on individualized reinforcement learning with latent state transitions could involve extending the identifiability results to handle continuous latent factors and time-varying latent factors. Addressing the nonparametric setting for infinite latent factors is crucial, as this would broaden the applicability of the framework. Further investigation into the impact of various assumptions, particularly regarding data distribution and sample size, on the identifiability and accuracy of the method is needed. Developing efficient algorithms for high-dimensional data and scaling the approach to handle massive datasets are essential for real-world applications. Finally, exploring the integration of causality concepts within the framework would enhance interpretability and facilitate the uncovering of causal relationships among latent factors, states, and actions. Investigating privacy-preserving techniques to address concerns around handling sensitive individual data is critical. Addressing these key limitations and extending the framework to handle real-world complexities would significantly enhance the impact and usability of this research for individualized RL.

More visual insights#

More on figures

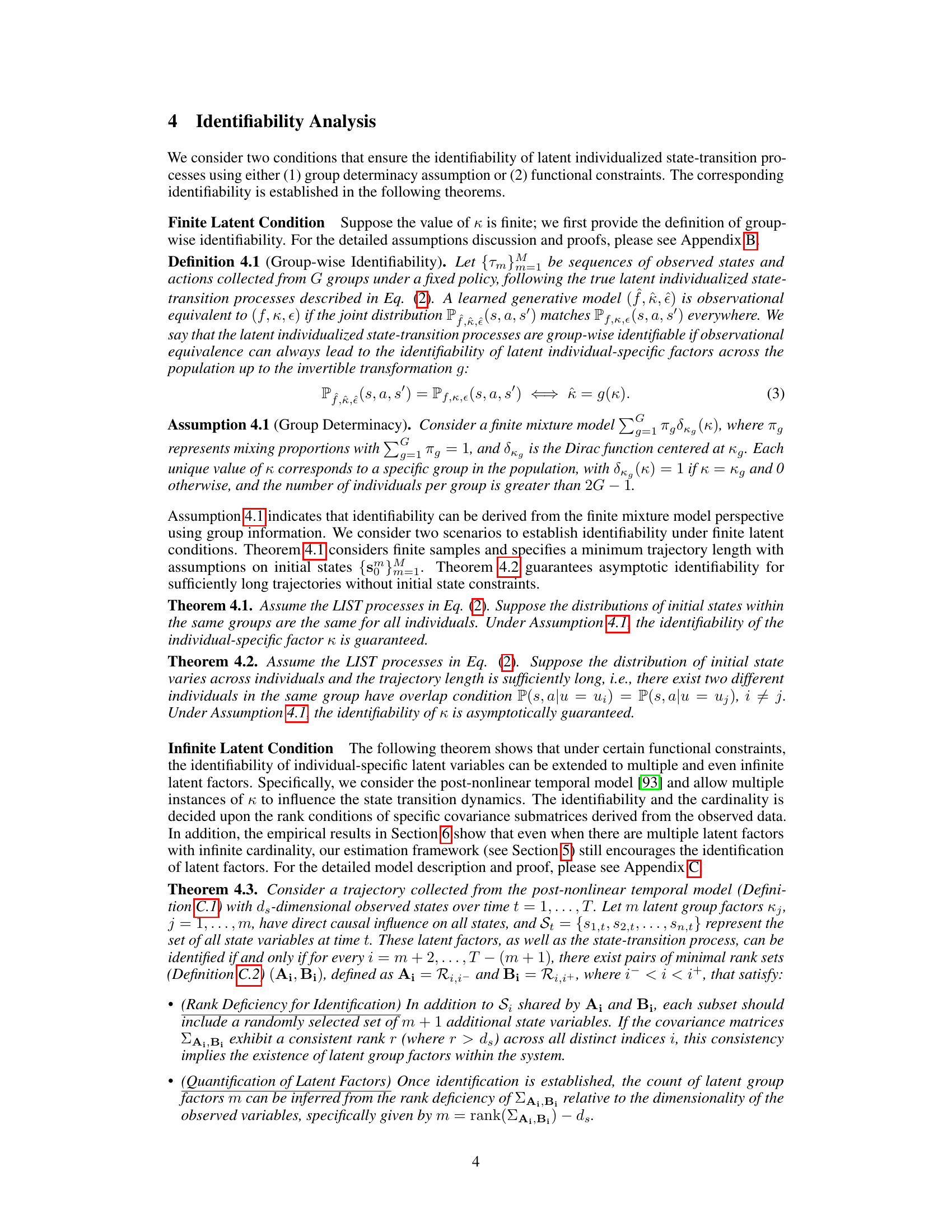

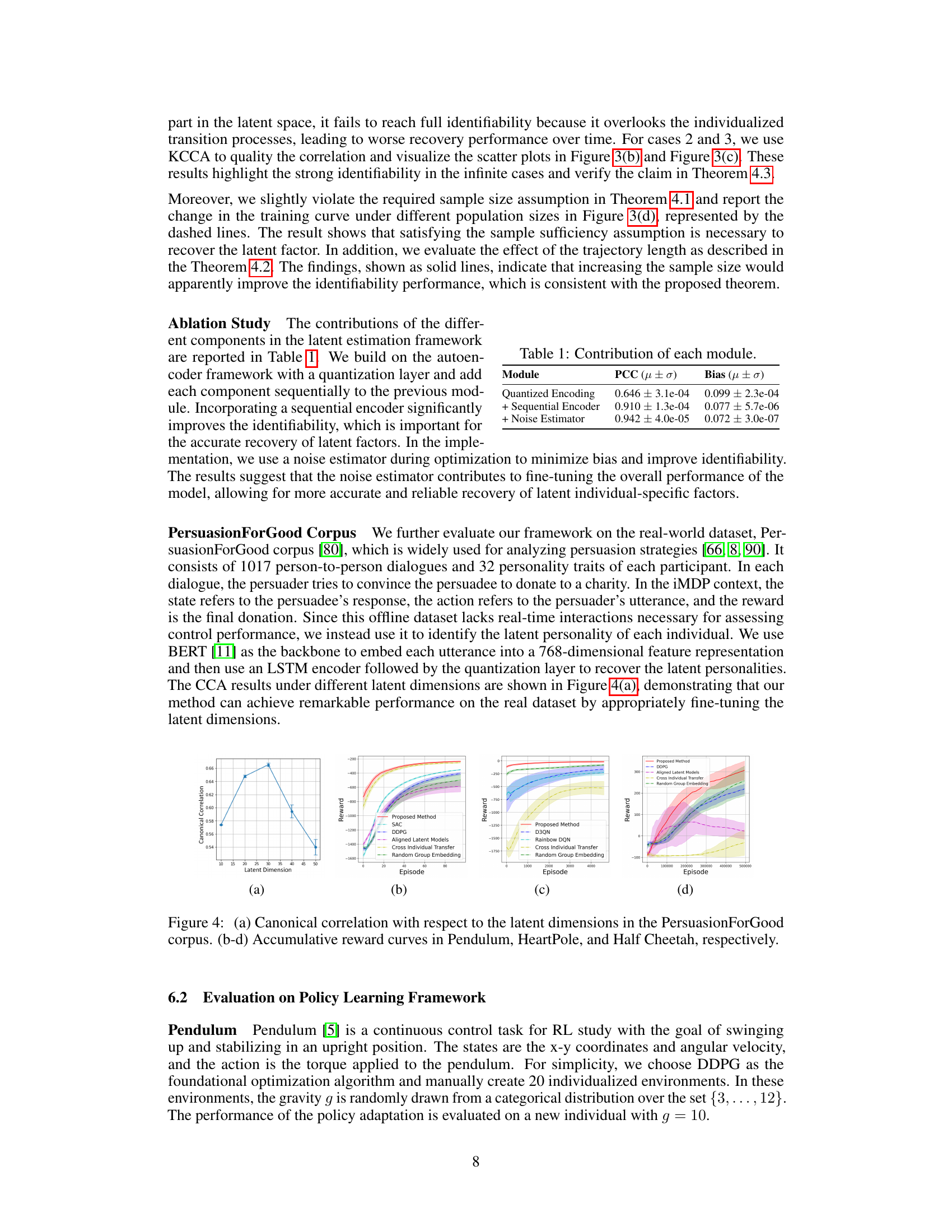

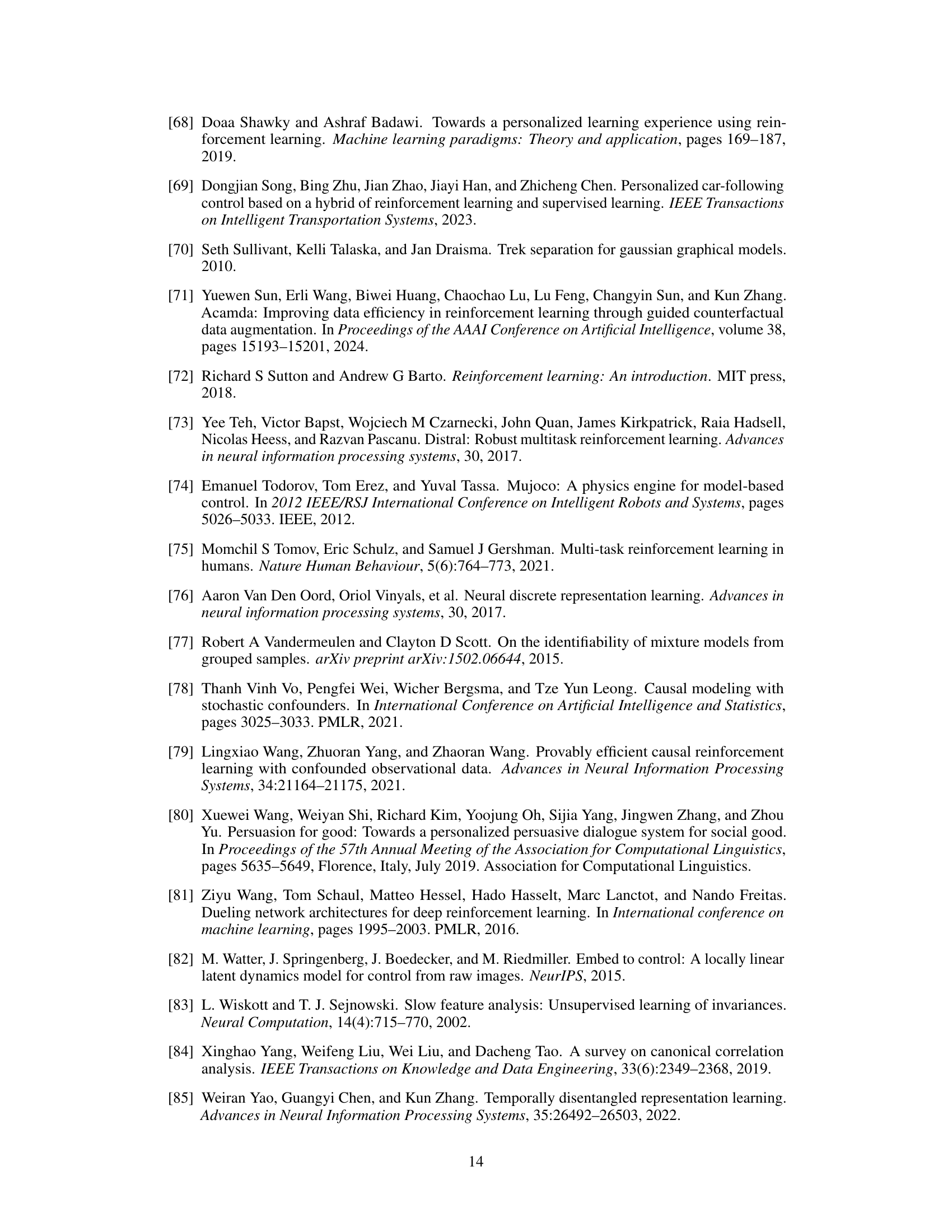

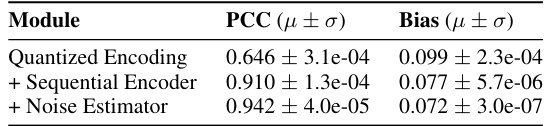

This figure illustrates the two-stage approach proposed in the paper for generating individualized policies. The first stage (a) focuses on latent factor estimation. It uses a quantized encoder to process each individual’s trajectory and estimate their latent factor. Then, it uses a conditional decoder to reconstruct the state transitions, using previous state-action pairs and the estimated latent factor as input. The second stage (b) is the policy learning stage. It incorporates the estimated latent factors to learn individualized policies using augmented labels, and adapts policies for new individuals.

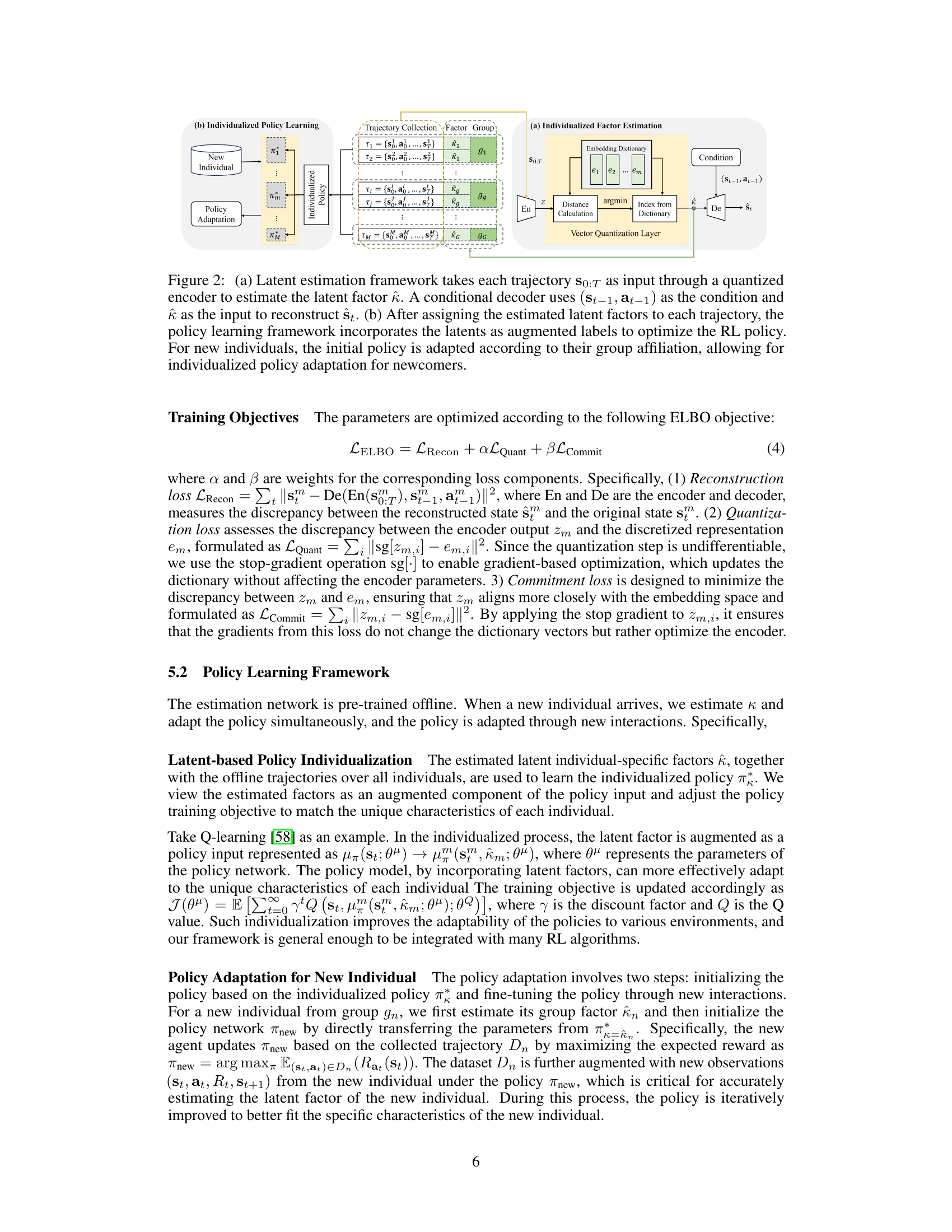

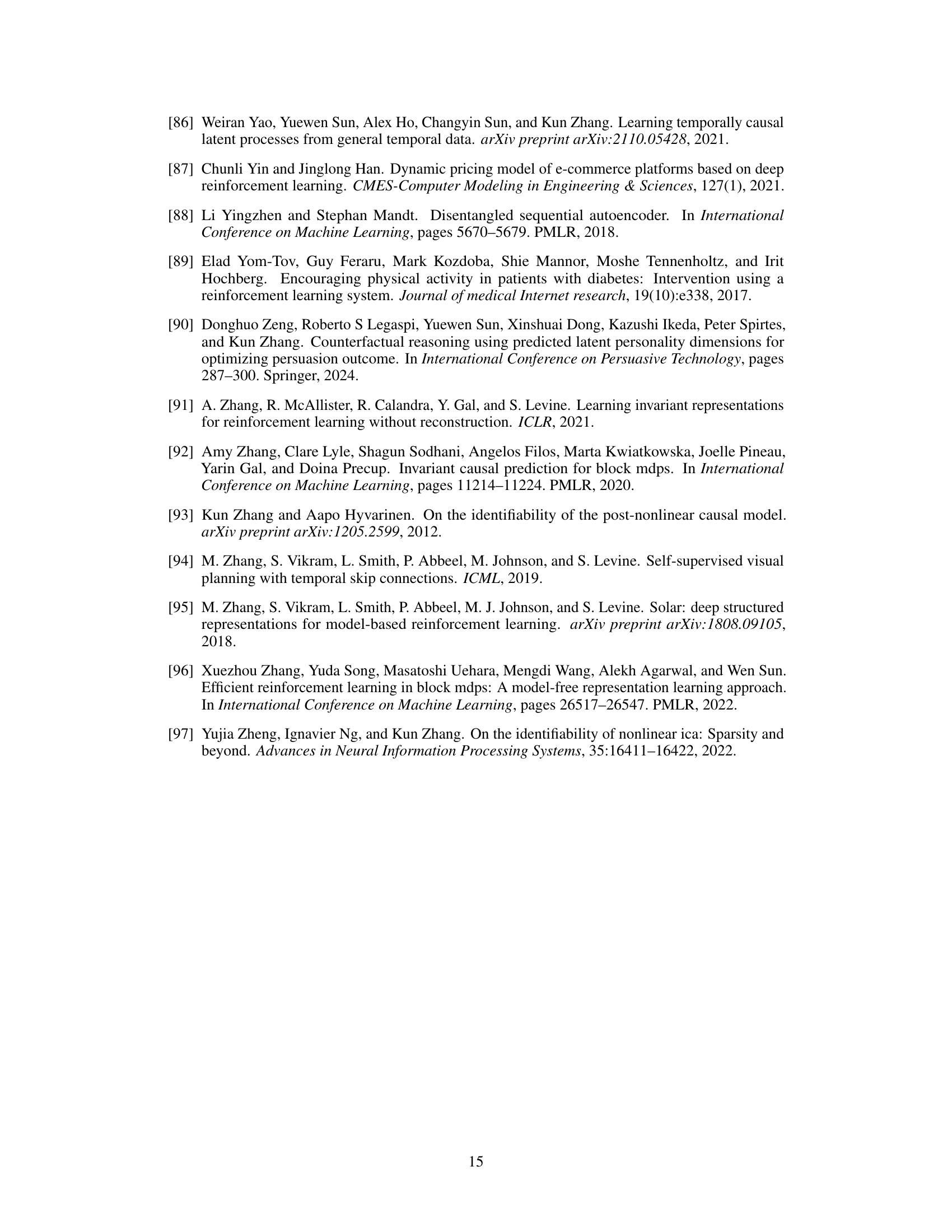

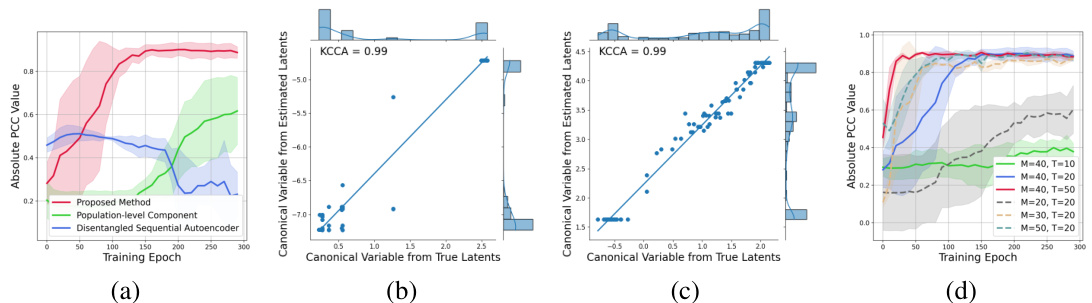

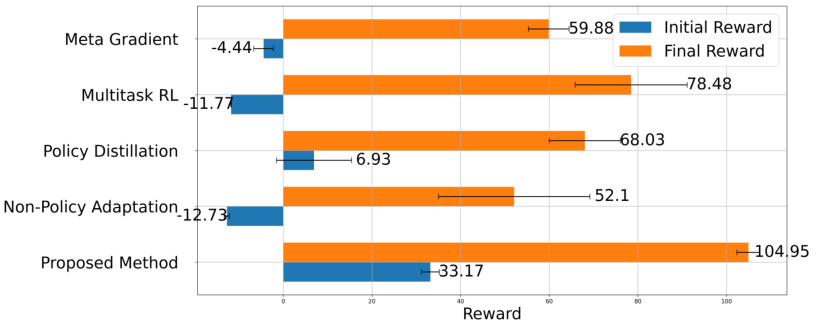

This figure presents the results of experiments on a synthetic dataset to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed latent estimation framework. Panel (a) shows the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) trajectories for Case 1 (finite latent factor), demonstrating the superior performance of the proposed method compared to baseline approaches like disentangled sequential autoencoders and population-level components. Panels (b) and (c) display scatter plots of the canonical variables from estimated and true latent factors for Case 2 (multi-dimensional finite latent factors) and Case 3 (multi-dimensional infinite latent factors), respectively. These illustrate strong correlation between estimated and true factors, indicating successful recovery. Panel (d) investigates the impact of sample size (number of individuals and trajectory length) on the identifiability of latent factors, demonstrating improvement with larger samples and trajectory lengths.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on a synthetic dataset to evaluate the performance of the proposed latent estimation framework. Subfigure (a) shows the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) trajectories over training epochs for Case 1 of the experiments (finite latent factor). Subfigures (b) and (c) display scatter plots of canonical variables from KCCA for Cases 2 and 3 (finite and infinite latent factors, respectively), illustrating the correlation between true and estimated latent factors. Finally, subfigure (d) demonstrates how the performance (identifiability) changes with varying sample sizes and trajectory lengths.

This figure illustrates the two-stage approach used in the paper for generating individualized policies. The first stage (a) shows the latent estimation framework. It uses a quantized encoder to process the individual trajectories and estimate the latent group factor (κ). A conditional decoder, given the previous state, action, and latent factor, reconstructs the next state. This helps to estimate the latent factors. The second stage (b) uses the estimated latent factors to optimize the RL policy. This is achieved by augmenting the latent factors as additional inputs to the policy network, leading to individualized policy learning that adapts well to new individuals based on their group affiliation.

This figure compares three different types of state-transition processes: (a) iMDP for individual m, showing individual-specific factors and state transitions; (b) Latent causal processes, illustrating latent causal relationships between latent and observed variables; (c) Factored nonstationary MDP, demonstrating latent factors that change over time influencing state transitions. Latent variables, which are unobserved, are shaded grey to highlight their influence on the observed processes. The figure visually represents how the individual-specific factors in an iMDP, compared to time-varying latent factors in other models, affect the state-transition process.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on a synthetic dataset to evaluate the performance of the proposed latent estimation framework. The experiments explore different scenarios with varying numbers of latent factors and sample sizes. (a) shows PCC trajectories over training epochs in a scenario with a single finite latent factor. (b-c) show scatterplots of canonical variables in scenarios with multiple finite latent factors (b) and infinite latent factors (c). The goal is to assess how well the framework can recover the latent factors under these different settings. (d) shows how identifiability performance changes with different sample sizes, demonstrating the impact of sufficient sample sizes in achieving higher identifiability.

This figure presents the results of synthetic experiments evaluating the performance of the proposed latent estimation framework. Subfigure (a) shows the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) trajectories for Case 1 (finite latent factor), demonstrating the superior performance of the proposed method compared to baseline methods. Subfigures (b) and (c) show the scatter plots of canonical variables for Case 2 and Case 3 (multiple finite and infinite latent factors respectively) using Kernel Canonical Correlation Analysis (KCCA), further validating the effectiveness of the approach. Finally, subfigure (d) illustrates the identifiability performance as a function of the sample size, confirming that sufficient data is crucial for effective estimation.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on a synthetic dataset to evaluate the latent estimation framework. Panel (a) shows the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) trajectories for Case 1 (finite latent factor), demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method compared to baselines like disentangled sequential autoencoder and population-level component. Panels (b) and (c) display scatter plots of canonical variables from Kernel Canonical Correlation Analysis (KCCA) for Cases 2 and 3 (finite and infinite latent factors, respectively). Panel (d) illustrates how identifiability performance changes with varying sample sizes and trajectory lengths, further validating the theoretical findings.

This figure presents the results of experiments on synthetic data to evaluate the performance of the latent estimation framework. The first plot (a) compares PCC trajectories for the different baselines in Case 1 (finite latent factor), demonstrating that the proposed method accurately recovers latent factors. The scatter plots (b) and (c) in Case 2 and 3 (finite and infinite latent factors) visualize canonical variables to show the high correlation between estimated and true latent factors. The last plot (d) shows how identifiability improves as the sample size increases.

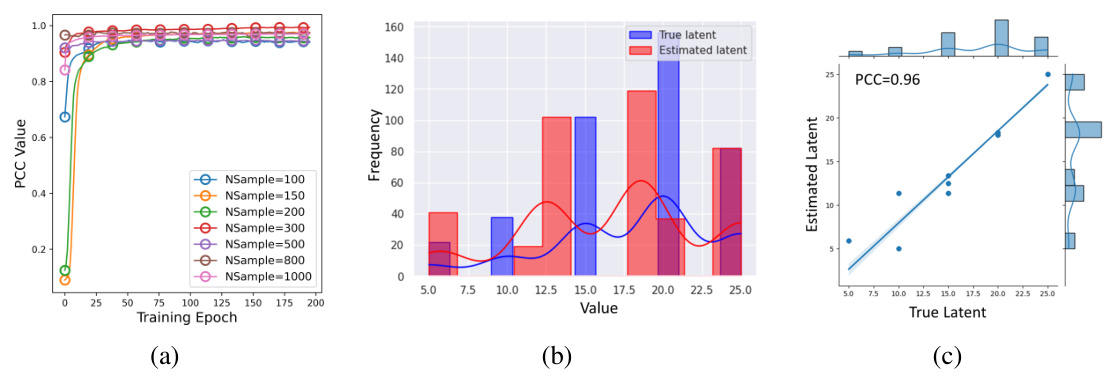

This figure demonstrates the impact of initial state variability and the effectiveness of using a transformer encoder in the proposed framework. Subfigure (a) and (b) show that despite high variability in initial states, the latent factors are still effectively estimated and clustered into four distinct groups. Subfigure (c) compares the performance of the original framework with a transformer-based encoder. The results indicate that the transformer encoder achieves faster convergence.

More on tables

This table shows the contribution of each module in the latent estimation framework. It demonstrates how the addition of sequential encoders and noise estimators significantly improves the performance (PCC) and reduces bias in estimating latent factors.

This table presents the ablation study results showing the contribution of each module in the latent estimation framework. It demonstrates a progressive increase in performance (measured by PCC and Bias) as more components are added. This highlights the importance of the sequential encoder and noise estimator for achieving high accuracy in latent factor recovery.

Full paper#