↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

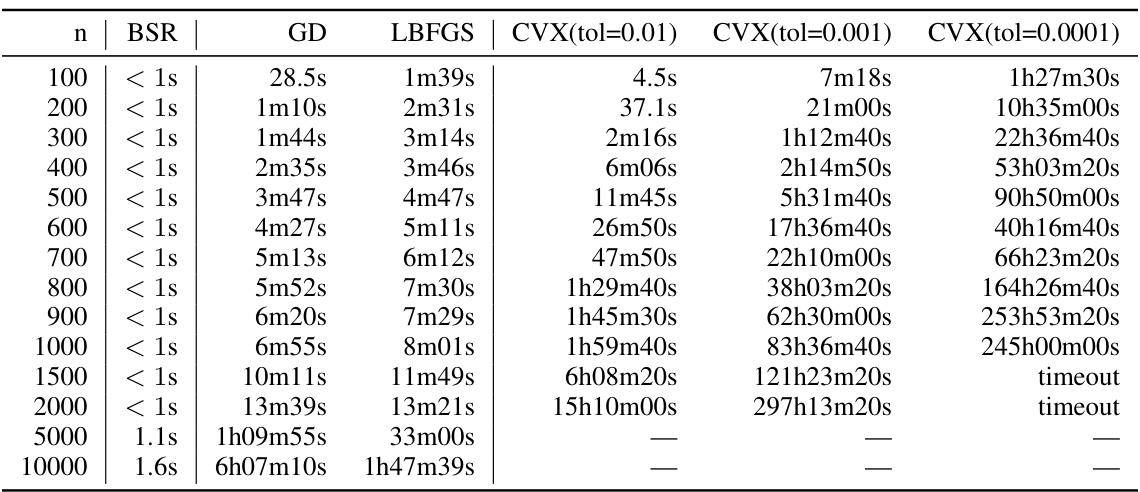

Differentially private model training using matrix factorization methods often involves computationally intensive optimization to find an optimal factorization before training. Existing methods struggle with scalability, hindering their application to large datasets. This research tackles this challenge by proposing a new matrix factorization technique, the banded square root (BSR) method.

BSR cleverly leverages the properties of the matrix square root to efficiently compute a factorization, dramatically reducing computational costs. The method demonstrates strong performance in both centralized and federated learning settings, achieving comparable accuracy to the best existing methods while avoiding the computational burden. The paper rigorously proves bounds on approximation quality and shows numerical experiments validating the efficiency and efficacy of BSR. This is a significant advancement in differentially private model training, promising more scalable and practical private AI solutions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in differential privacy and machine learning. It offers a computationally efficient solution to a long-standing challenge in private model training, enabling the development of more accurate and scalable private AI systems. The findings are highly relevant to current research trends in federated learning and privacy-preserving machine learning and may help improve privacy-utility tradeoffs. The novel factorization technique opens new avenues for investigating optimal factorization methods and their applications.

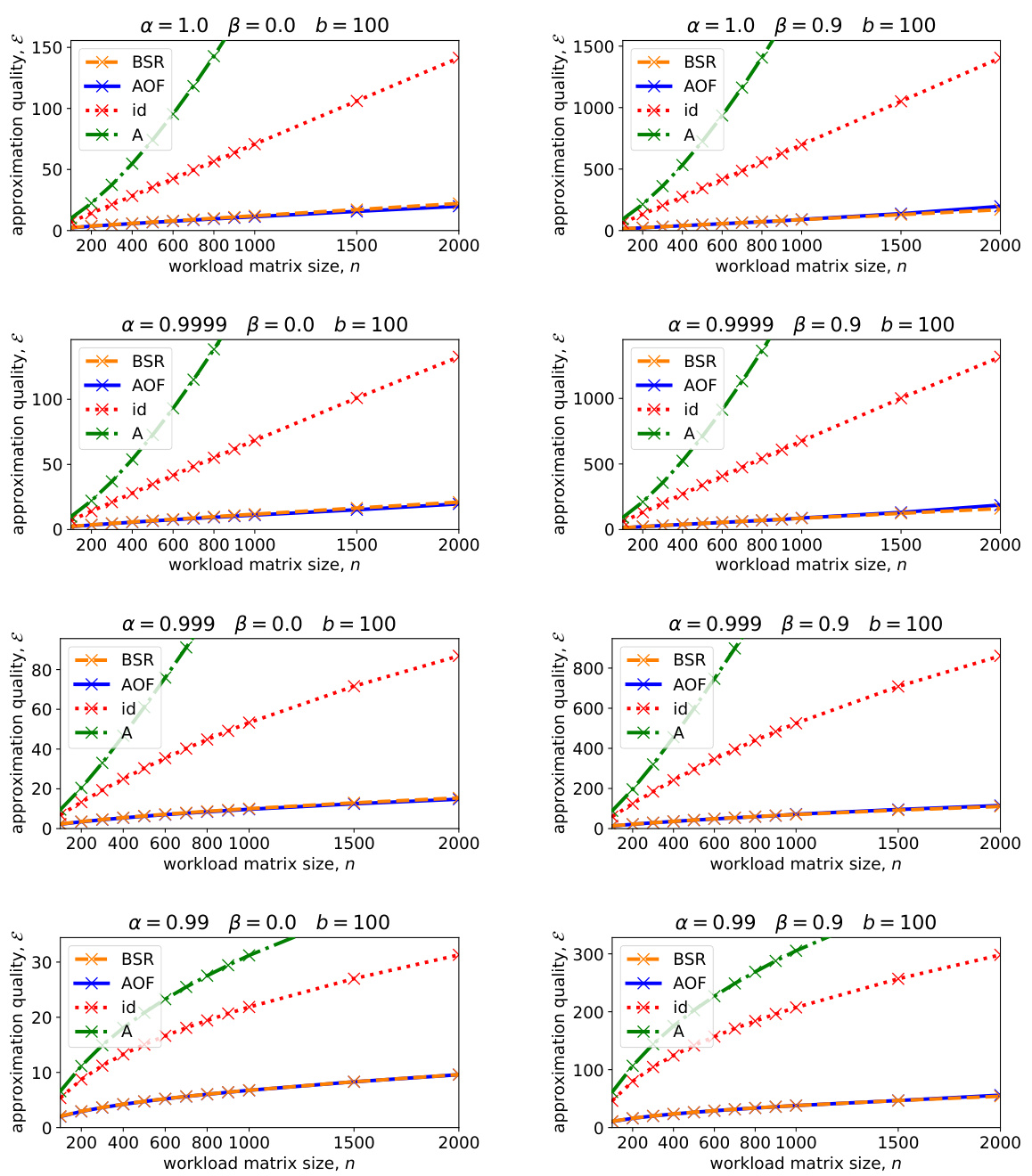

Visual Insights#

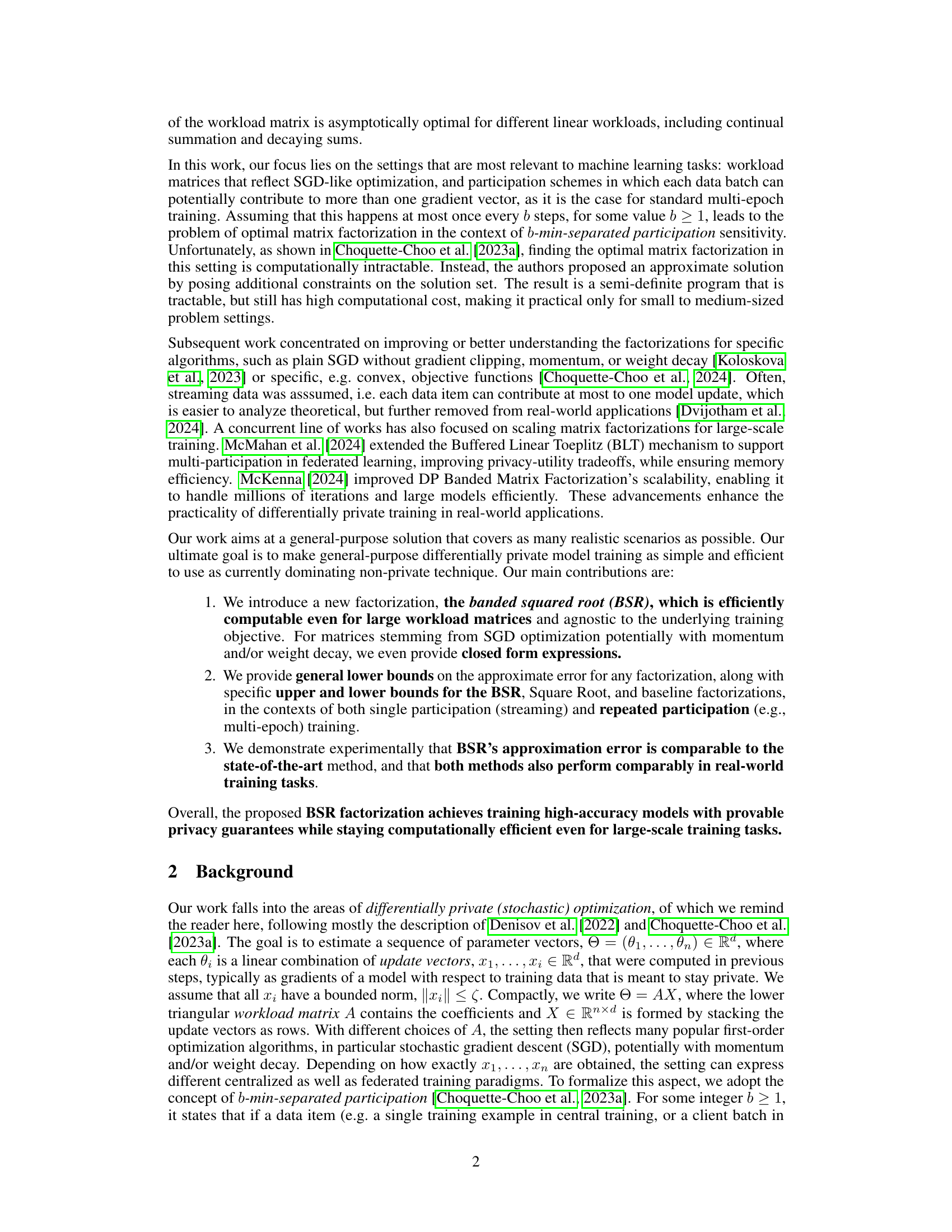

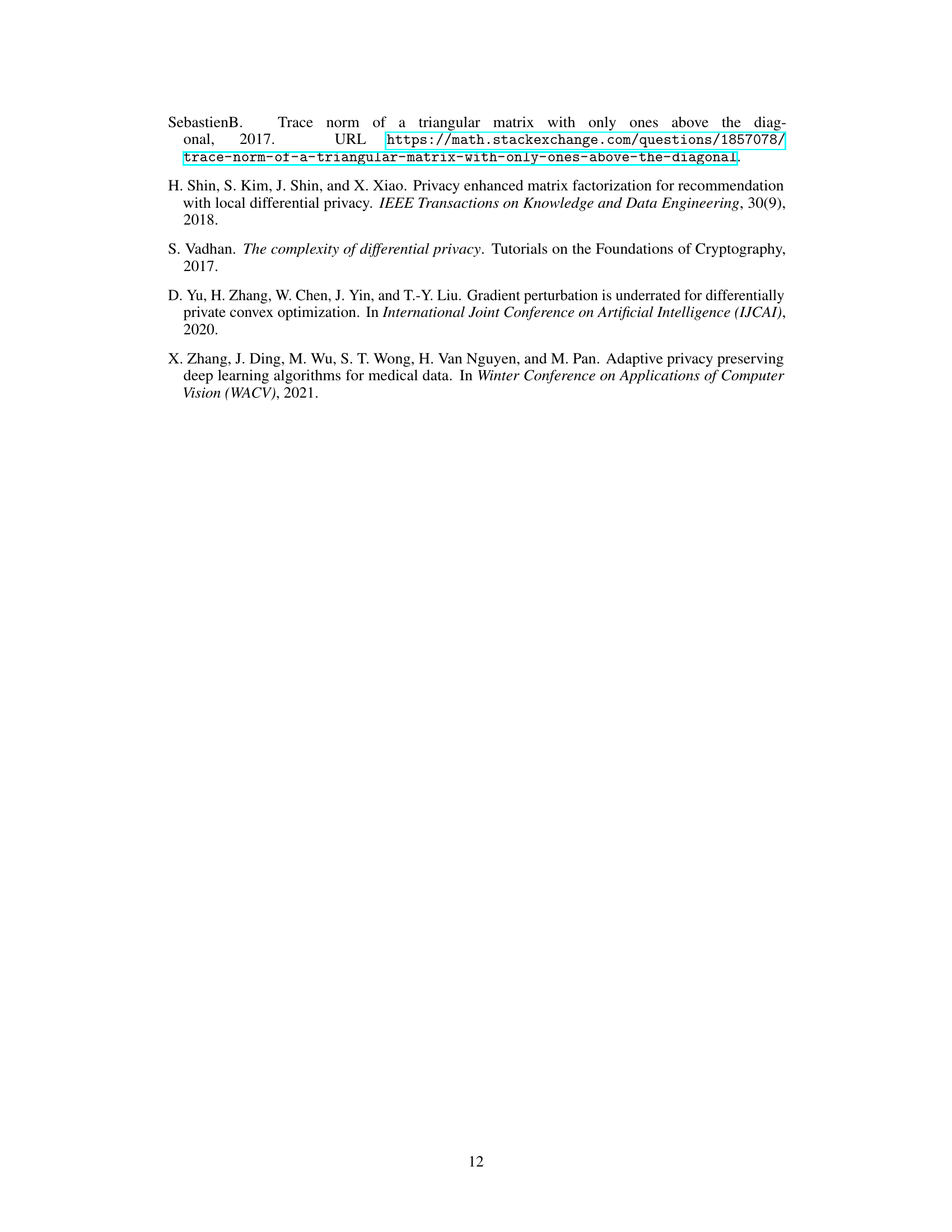

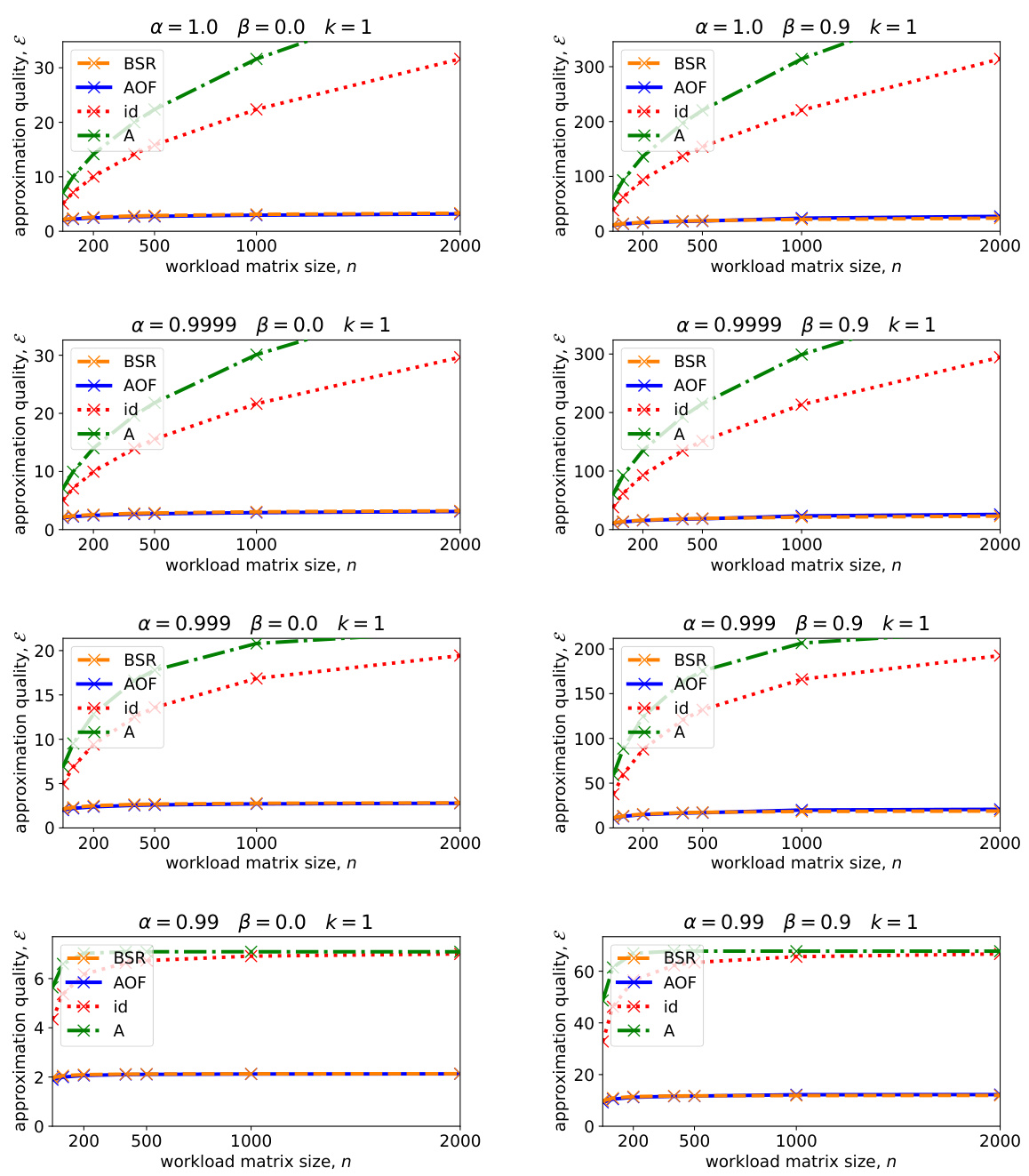

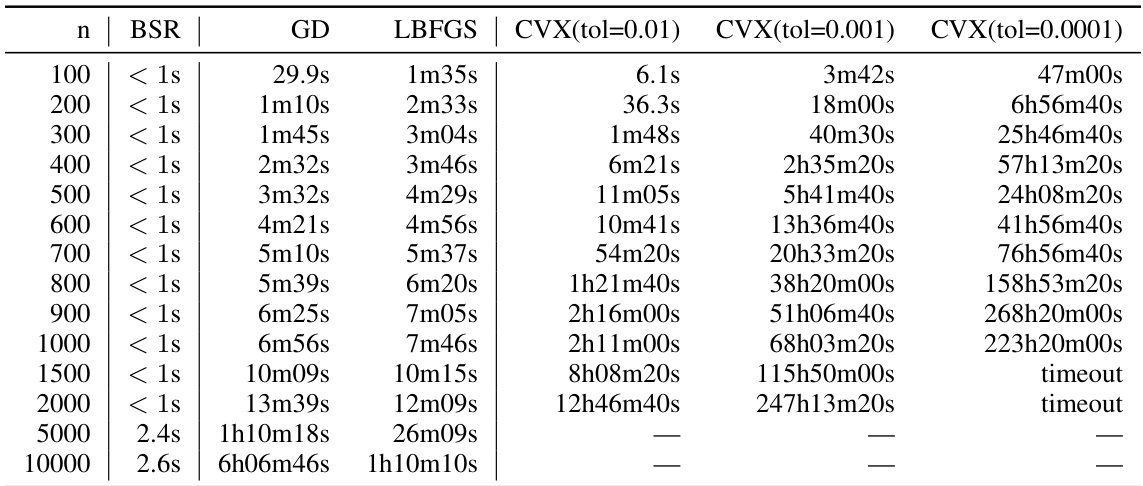

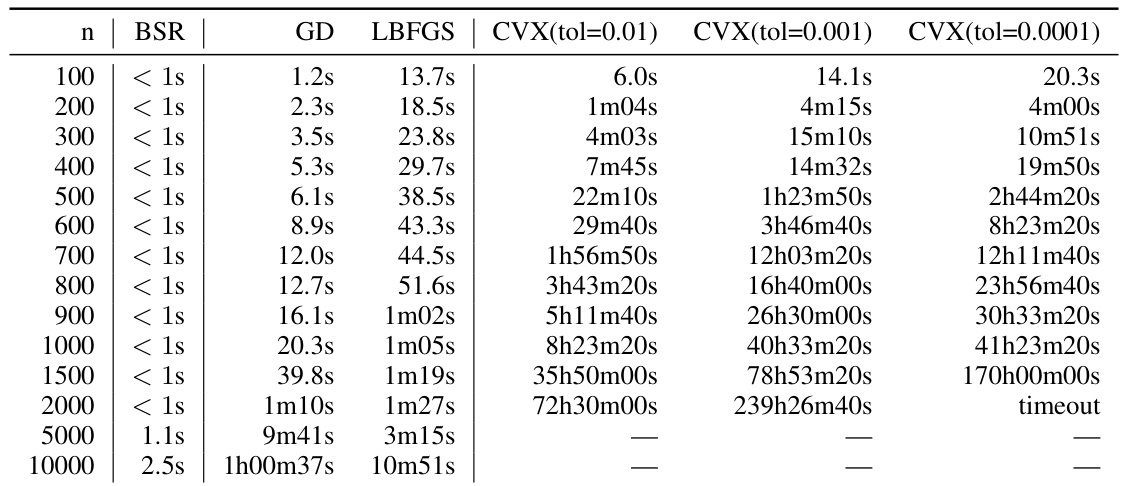

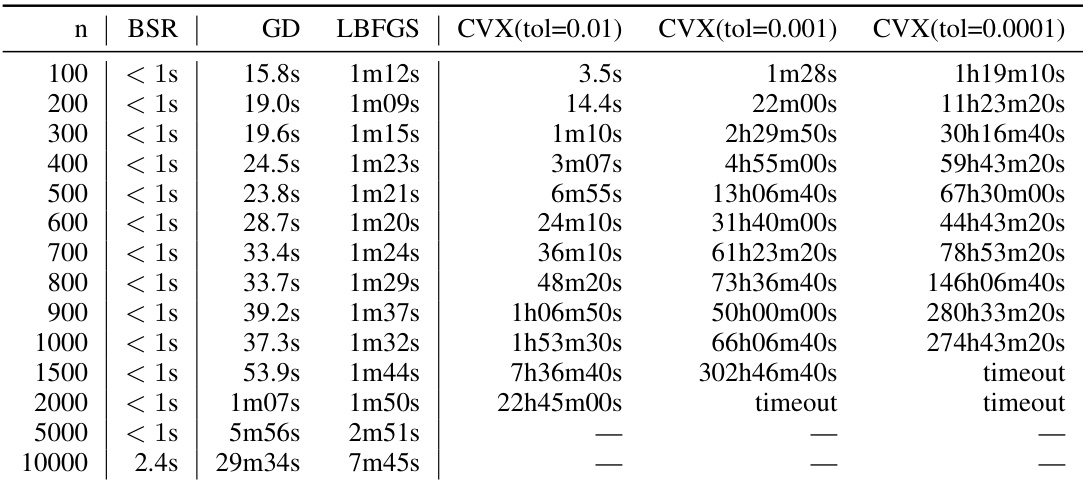

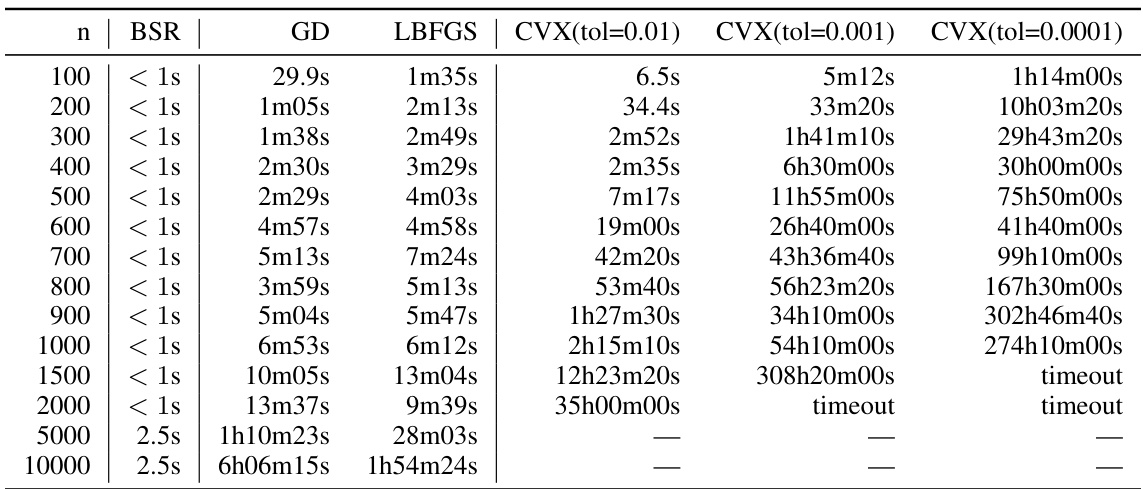

The figure shows the expected approximation error for different matrix factorization methods (BSR, AOF, Id, A) with two different sets of hyperparameters for SGD optimization (α and β). The left plot uses α = 0.999 and β = 0, while the right plot uses α = 1 and β = 0.9. Both plots consider the setting of repeated participation where b = 100 and k = n/100. The x-axis represents the workload matrix size (n), and the y-axis represents the expected approximation error. The plot demonstrates that BSR achieves approximation error comparable to AOF, while significantly outperforming the baseline factorizations (Id and A).

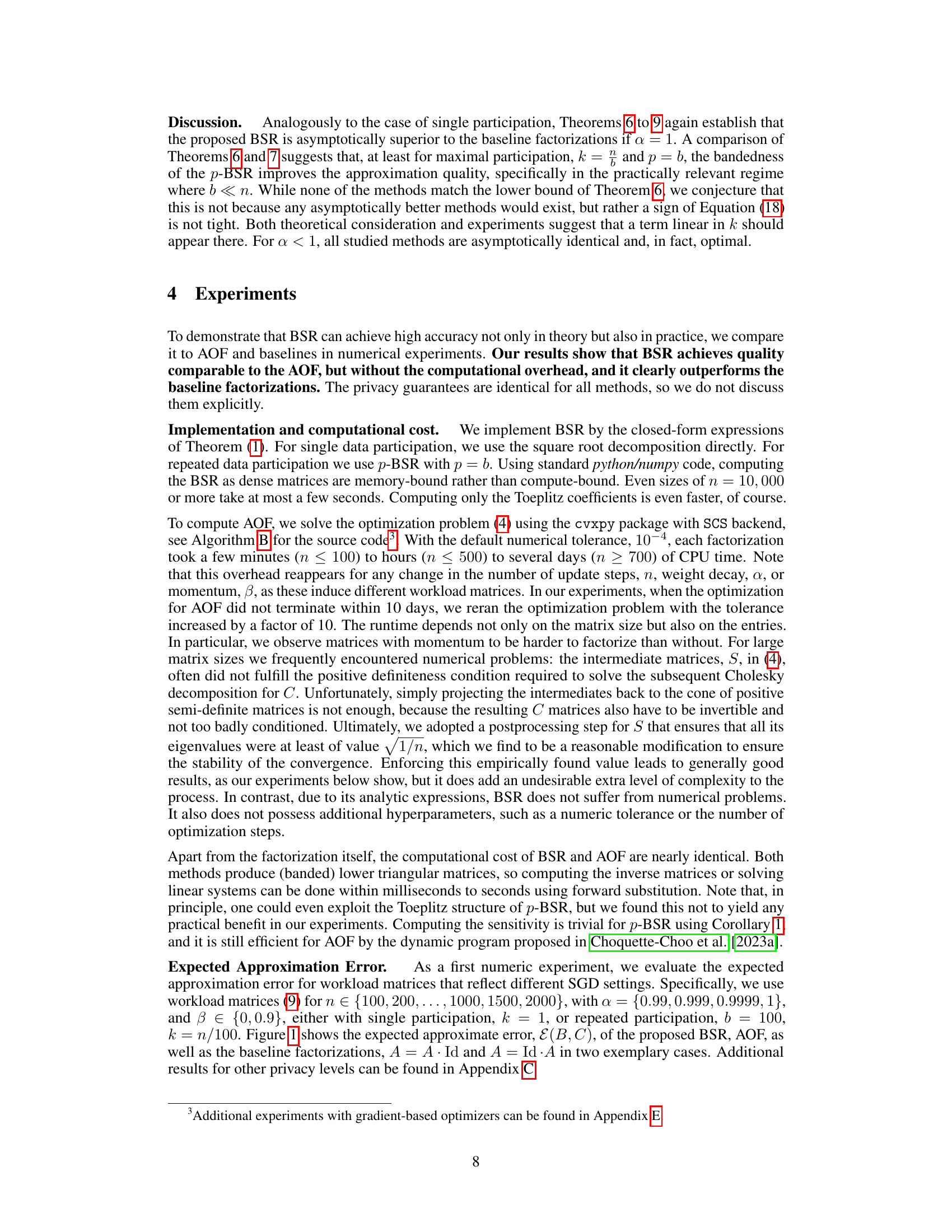

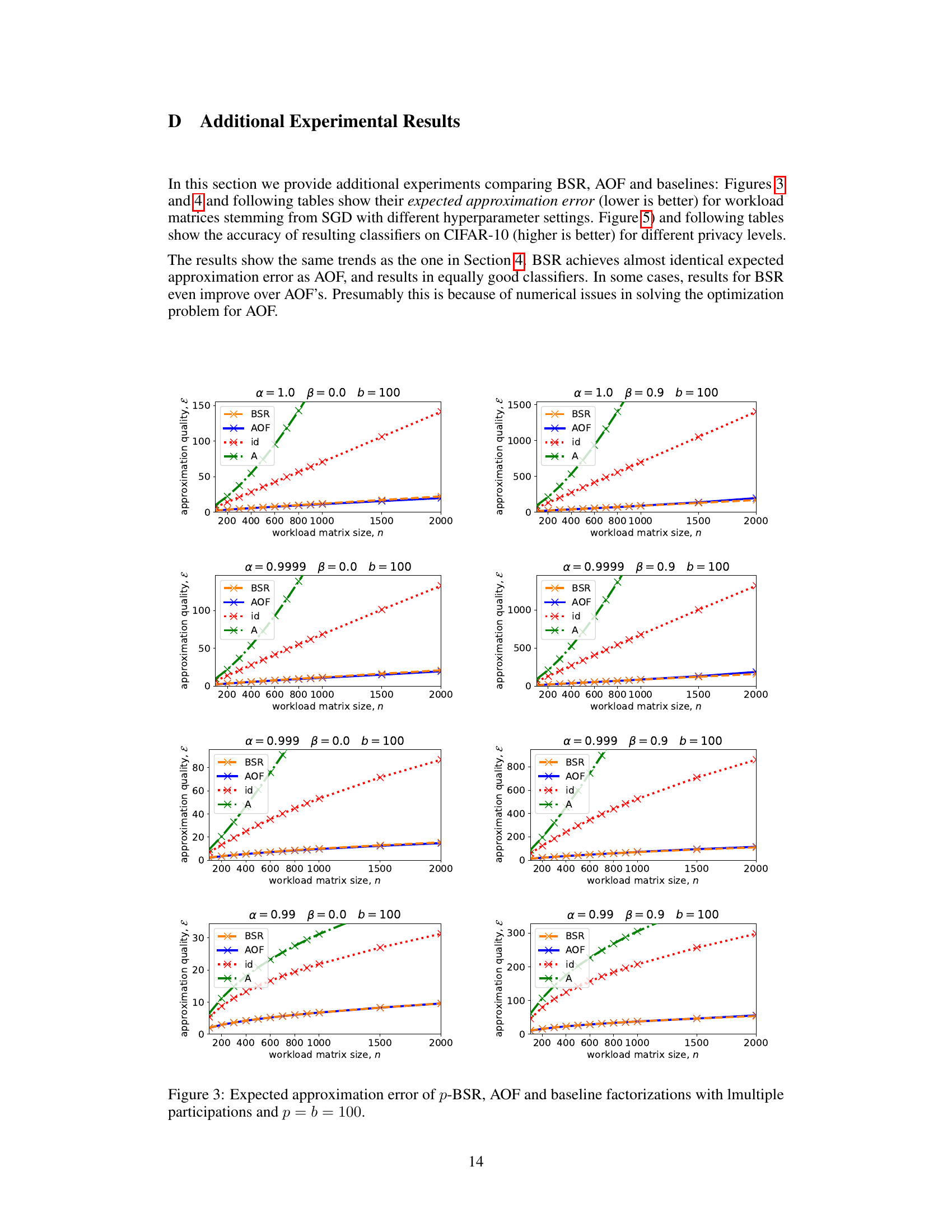

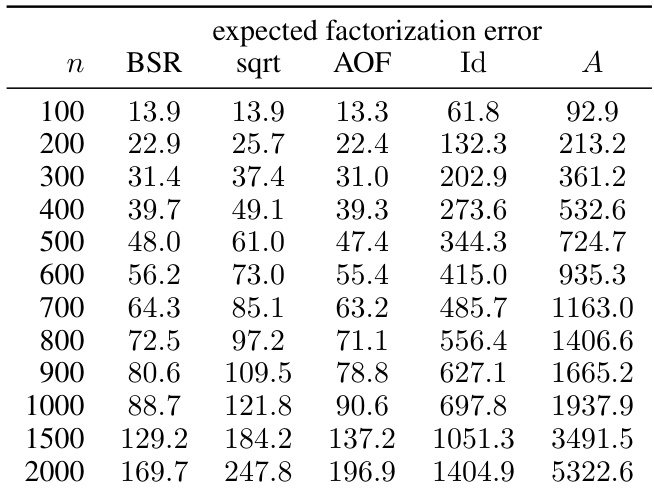

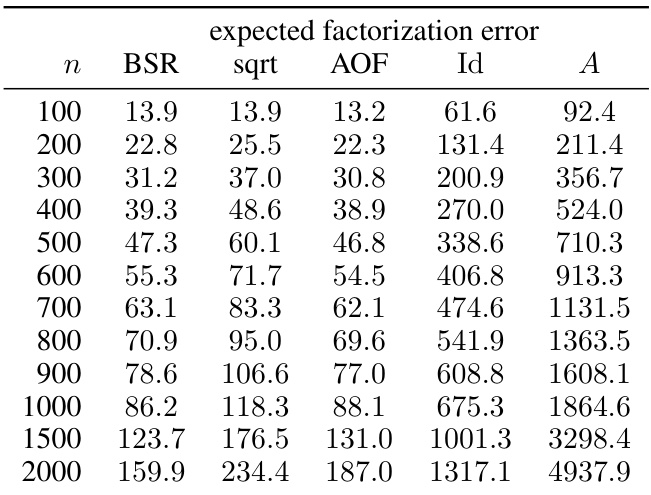

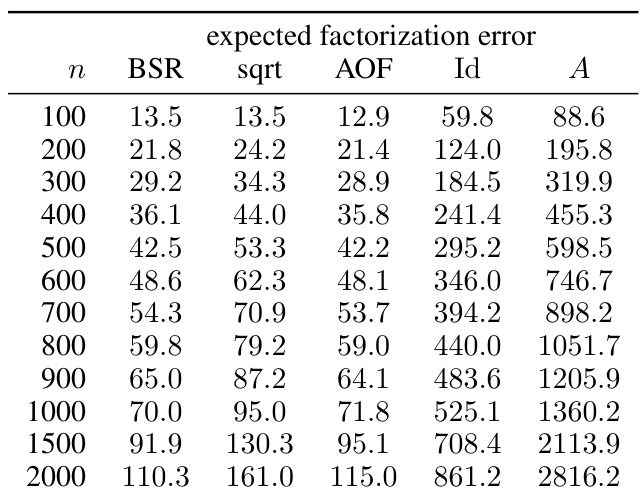

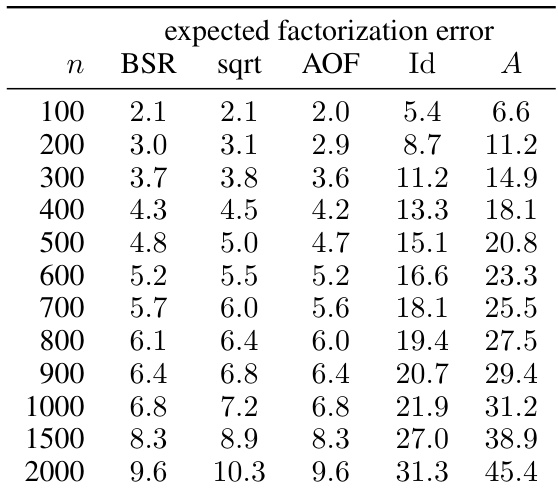

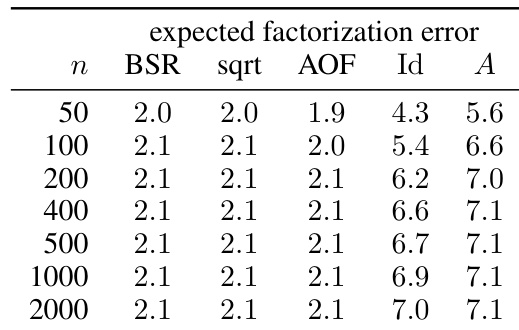

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The settings used were α = 1, β = 0 (no momentum), k = 1 (single participation), and b = k/n. The privacy parameters were ε = 1.18 and δ = ε/n. The results are shown graphically in Figure 3.

In-depth insights#

DP-SGD Matrix Fact#

Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent (DP-SGD) methods enhance the privacy of training data in machine learning. A common approach involves matrix factorization to manage noise addition strategically. The DP-SGD Matrix Fact technique likely leverages this, representing the iterative updates of the SGD algorithm as a matrix multiplication. This matrix is then factorized, allowing for noise to be injected efficiently while preserving privacy guarantees. The factors might be designed to minimize noise amplification during matrix multiplication, optimizing privacy-utility trade-offs. Computational efficiency is a crucial aspect as matrix operations can become expensive with large datasets. Therefore, the method likely explores techniques to reduce computation complexity during factorization and subsequent operations. A key focus is likely on providing theoretical guarantees on the accuracy of the approximate factorization and its impact on the overall model’s utility and privacy. The effectiveness likely depends on the choice of factorization and noise mechanism, necessitating careful consideration. Federated learning settings, where data is distributed across multiple parties, would benefit greatly from efficient matrix factorization to minimize communication overhead. Finally, a comprehensive approach would incorporate rigorous analysis of privacy and utility bounds.

BSR Factorization#

The proposed Banded Square Root (BSR) factorization offers a computationally efficient alternative to existing matrix factorization techniques for differentially private model training. BSR leverages the properties of the matrix square root, allowing for efficient computation, especially for large-scale problems. Analytical expressions for BSR are derived for common SGD scenarios, including momentum and weight decay, minimizing computational overhead. Theoretical analysis provides bounds on the approximation quality, demonstrating that BSR’s performance is comparable to state-of-the-art methods while completely avoiding their computational bottlenecks. The efficiency and provable privacy guarantees make BSR a promising approach for enhancing the practicality and scalability of differentially private machine learning.

Approximation Error#

The concept of ‘Approximation Error’ is crucial in evaluating the performance of differentially private model training. The paper centers on a novel matrix factorization technique (BSR) aiming to reduce computational overhead while maintaining high accuracy. The ‘Approximation Error’ quantifies how well BSR approximates the optimal factorization. Lower error indicates better performance, aligning with the desired balance of privacy and utility. The analysis includes theoretical bounds on the error for both single and repeated data participation, highlighting BSR’s asymptotic optimality in specific scenarios. The experimental results show BSR achieving comparable accuracy to state-of-the-art methods (AOF) but with significantly reduced computational cost. This is a key contribution, as the computationally expensive optimization problem in AOF limits its scalability. By carefully analyzing approximation error, the paper demonstrates BSR’s efficacy and practicality as a general-purpose solution for differentially private machine learning.

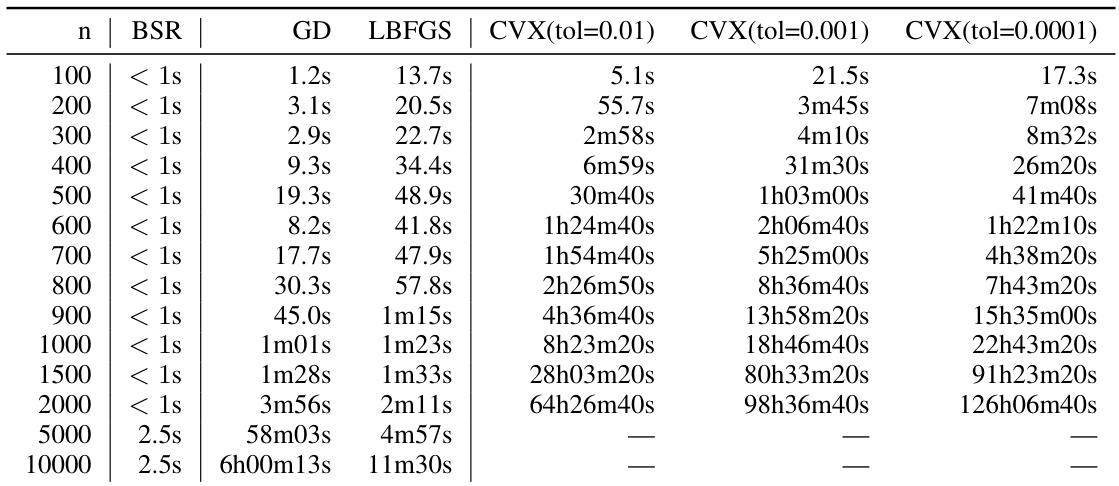

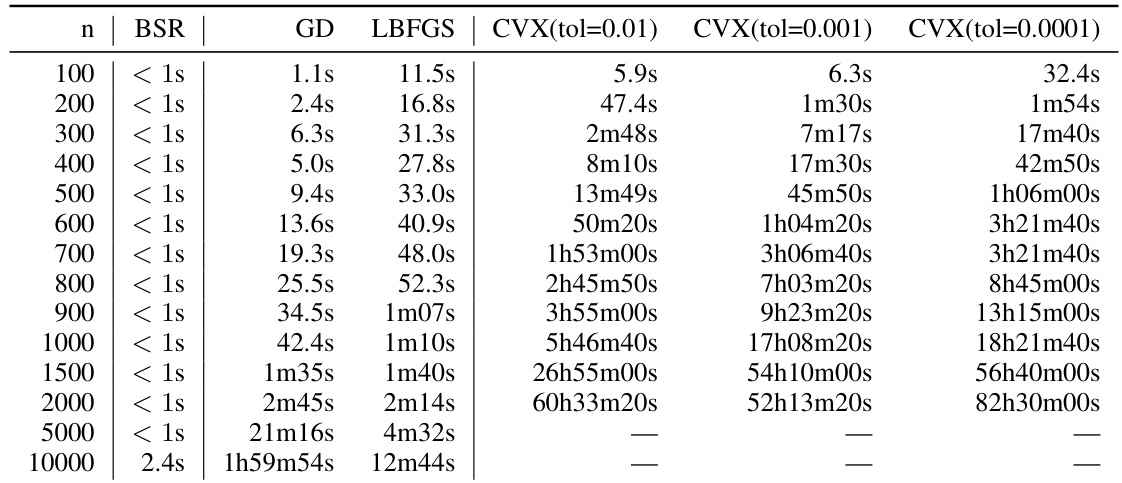

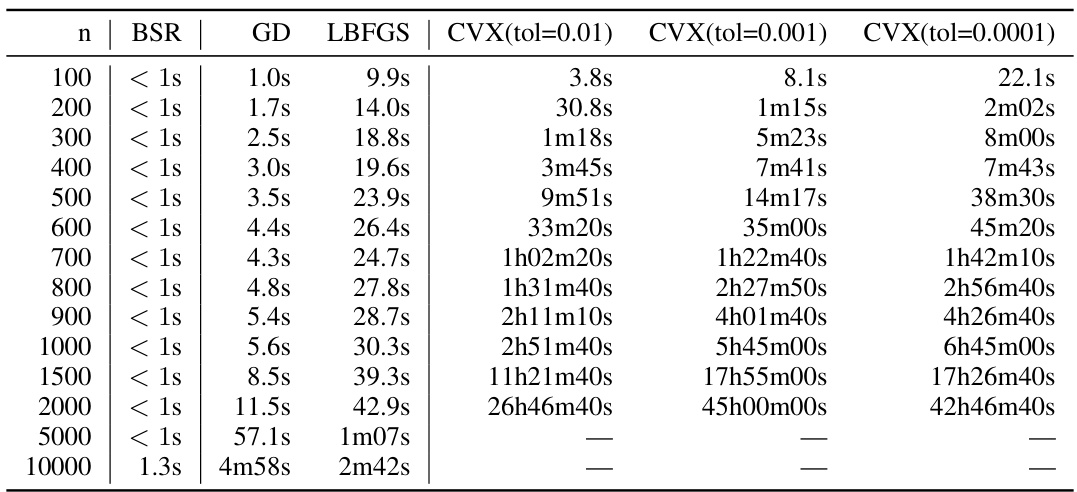

Efficiency Analysis#

An efficiency analysis of a machine learning model should meticulously examine computational cost, memory usage, and training time. For large-scale models, computational complexity becomes paramount, so algorithms with lower time complexity (e.g., linear vs. quadratic) are preferred. Memory usage is critical; techniques like gradient checkpointing or model parallelism can mitigate excessive memory demands. Training time should be assessed across various hardware setups, considering factors such as CPU cores, GPU acceleration, and distributed computing environments. A comprehensive analysis necessitates comparing the chosen model’s efficiency to established benchmarks and state-of-the-art techniques, quantifying the performance gains or tradeoffs. Furthermore, scalability across differing datasets and model sizes is essential. The analysis should also discuss factors that impact efficiency, such as hyperparameter tuning and data preprocessing steps. The goal is to present a detailed, quantitative evaluation of the model’s efficiency to guide its practical application.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to encompass more complex scenarios, such as variable learning rates or adaptive optimization algorithms, would strengthen the theoretical foundation. Empirical evaluations on a broader range of datasets and model architectures are needed to confirm the generalizability of the proposed BSR factorization. Furthermore, investigating the robustness of BSR to various forms of data corruption or adversarial attacks is crucial for real-world applications. Finally, research could focus on developing efficient techniques for handling extremely large-scale datasets that are beyond the computational capabilities of current methods, potentially leveraging distributed or federated learning paradigms. This would significantly enhance the practicality of differentially private machine learning.

More visual insights#

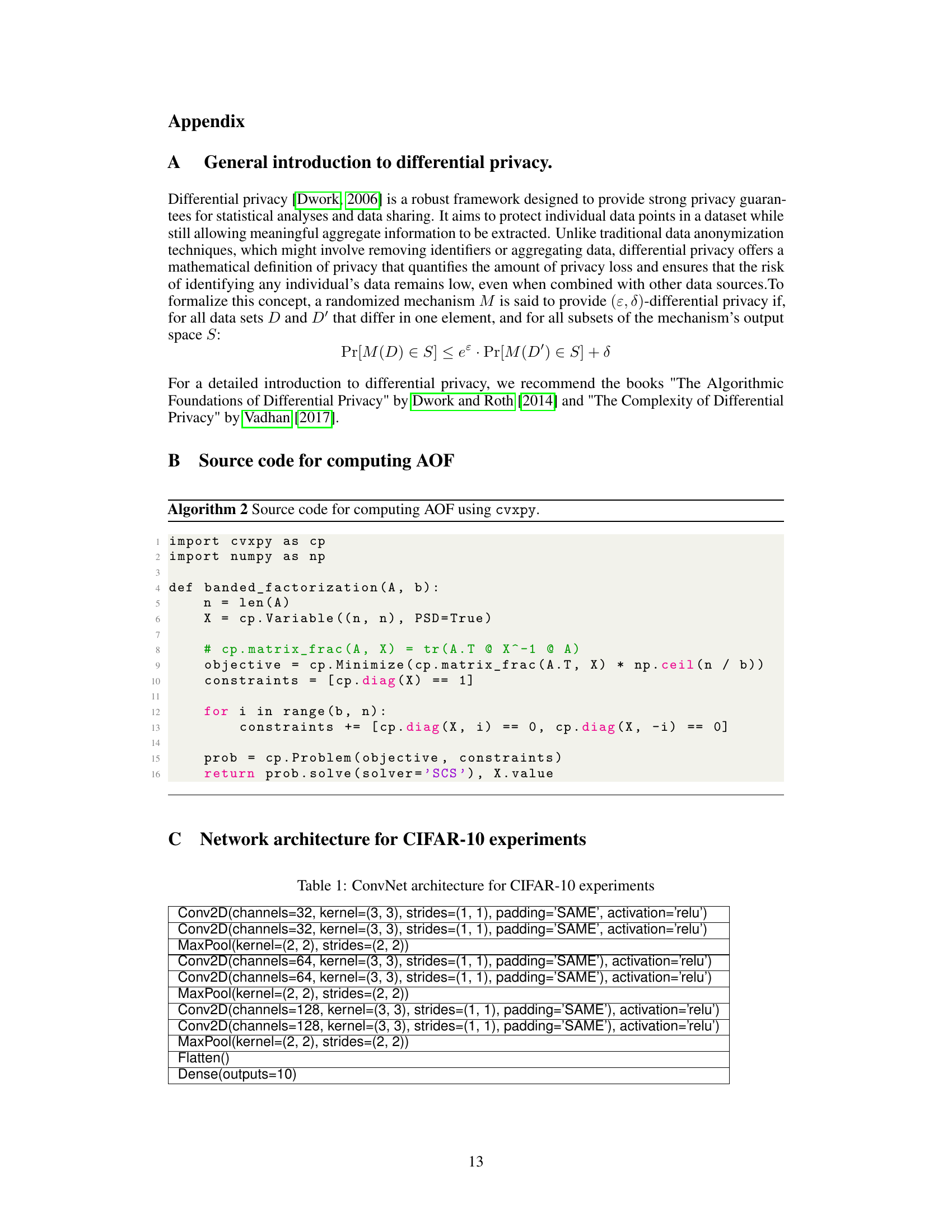

More on figures

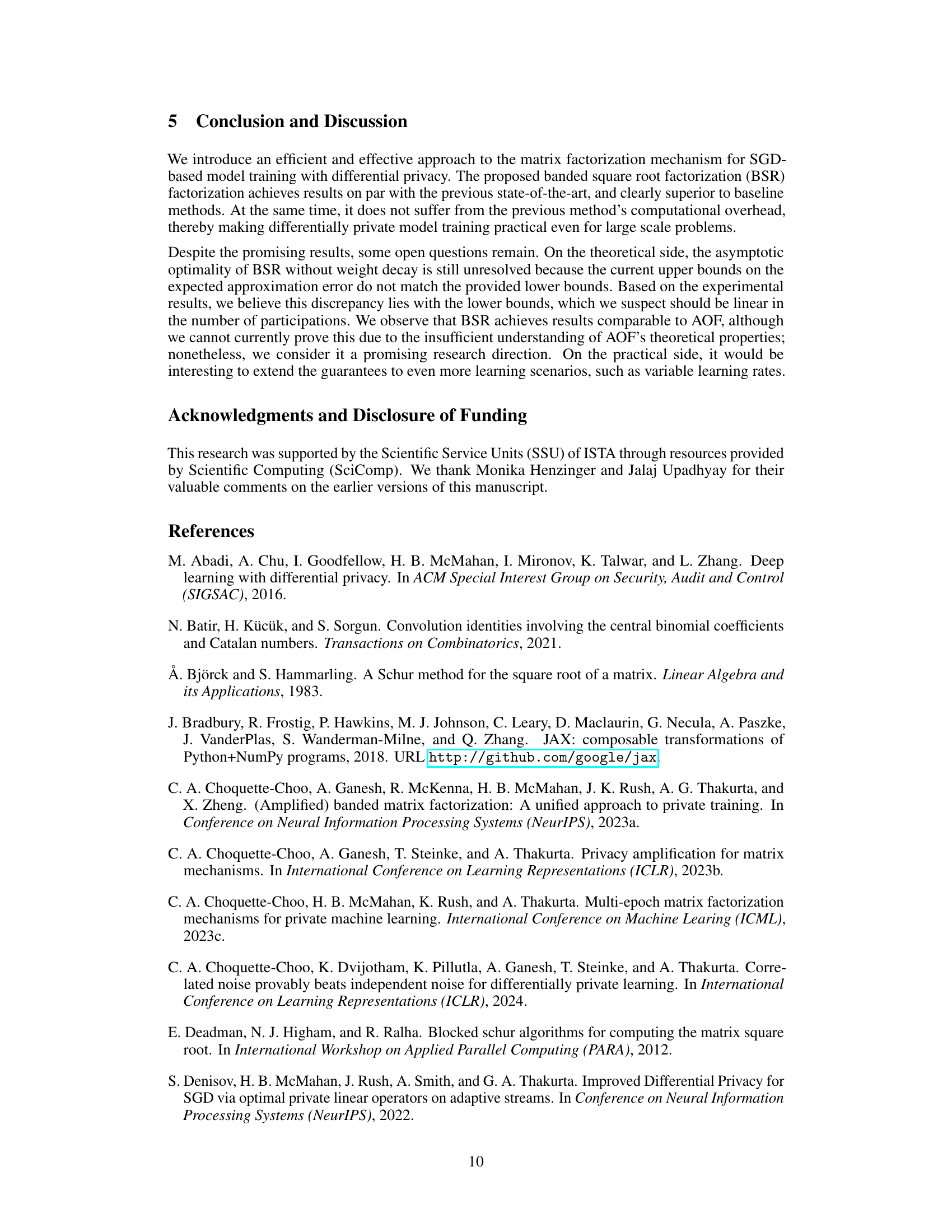

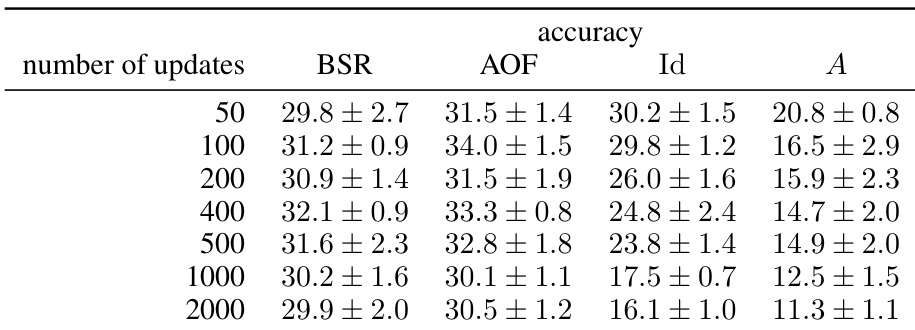

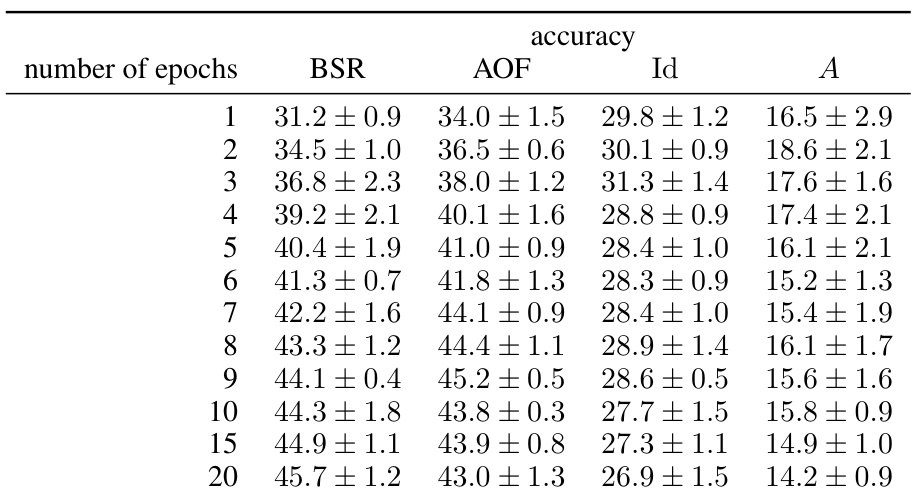

This figure compares the classification accuracy of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, AOF, Id, A) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left plot shows the accuracy when training for a single epoch with varying batch sizes. The right plot illustrates the results obtained when using a fixed batch size but changing the number of epochs.

This figure compares the expected approximation error for four different matrix factorization methods (BSR, AOF, Id, A) used in differentially private SGD model training. The comparison is done for two different sets of hyperparameters (α and β representing weight decay and momentum, respectively), each with repeated data participation (each data batch contributes multiple times). The x-axis represents the size of the workload matrix (n), and the y-axis represents the approximation error. The figure demonstrates that BSR achieves comparable accuracy to the best-performing existing method (AOF) while having much lower computational overhead. The baselines (Id and A) show significantly higher error.

This figure compares the expected approximation error of four different matrix factorization methods (BSR, AOF, Id, and A) for two different sets of hyperparameters (α and β) in the context of repeated participation in stochastic gradient descent (SGD) model training. The x-axis shows the size of the workload matrix, which increases as the number of SGD steps or training epochs increases. The y-axis shows the expected approximation error. The left plot uses hyperparameters α = 0.999 and β = 0, while the right plot uses α = 1 and β = 0.9. The results indicate that BSR has an approximation error comparable to that of AOF, and both perform better than the baseline methods.

The figure shows the expected approximation error for four different matrix factorization methods: BSR, AOF, Identity-left, and Identity-right. Two different hyperparameter settings are compared (α=0.999, β=0 and α=1, β=0.9). The x-axis represents the size of the workload matrix (n), and the y-axis represents the expected approximation error. The plot shows that BSR and AOF consistently outperform the baseline methods (Identity-left and Identity-right) across different matrix sizes and hyperparameters. BSR and AOF have similar approximation errors; BSR sometimes yields slightly better values than AOF, potentially due to numerical limitations in solving AOF for larger matrices.

The figure shows the expected approximation error for different matrix factorization methods used in differentially private SGD. Two sets of hyperparameters are shown: one with weight decay (α = 0.999, β = 0) and another without (α = 1, β = 0.9). The error is plotted against the size of the workload matrix (n). The results compare the banded square root (BSR) factorization to the approximately optimal factorization (AOF) and two baseline methods.

This figure compares the expected approximation errors of four different matrix factorization methods for differentially private SGD model training. Two different hyperparameter settings (momentum and weight decay) are tested in the context of repeated data participation. The methods compared are the proposed Banded Square Root (BSR) factorization, the Approximately Optimal Factorization (AOF), and two baseline methods (A = A * Id and A = Id * A). The figure shows that BSR achieves comparable performance to AOF while having a significantly lower computational cost.

This figure compares the expected approximation errors of four different matrix factorization methods for differentially private SGD model training: BSR (banded square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity matrix baseline), and A (workload matrix baseline). Two distinct hyperparameter settings are considered: one with weight decay (α=0.999, β=0) and another without (α=1, β=0.9). The results illustrate that BSR achieves comparable approximation error to AOF across a range of workload matrix sizes, while substantially outperforming the baselines. The repeated participation setting (b=100, k=n/100) implies that each data batch can contribute multiple times to the model updates, mirroring realistic multi-epoch training scenarios.

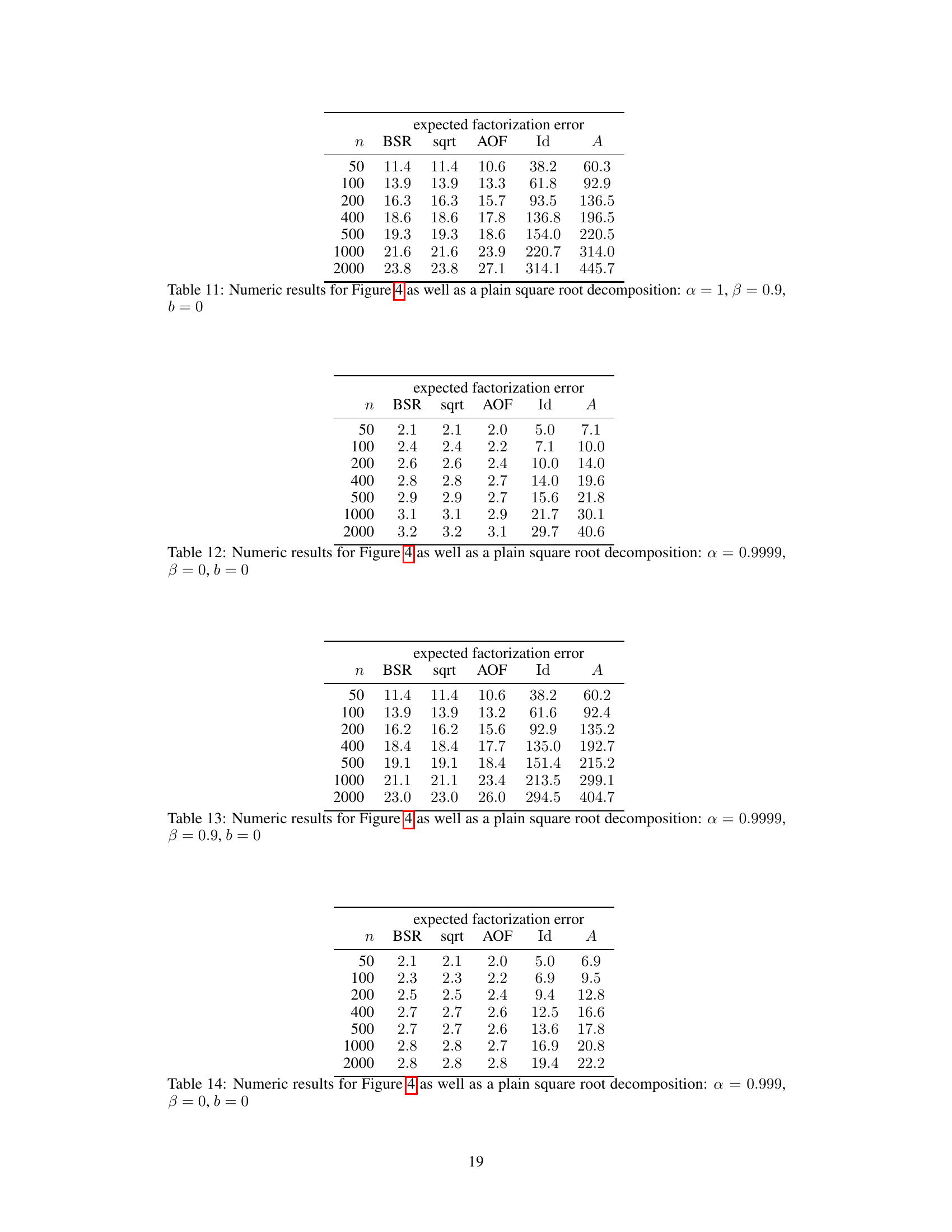

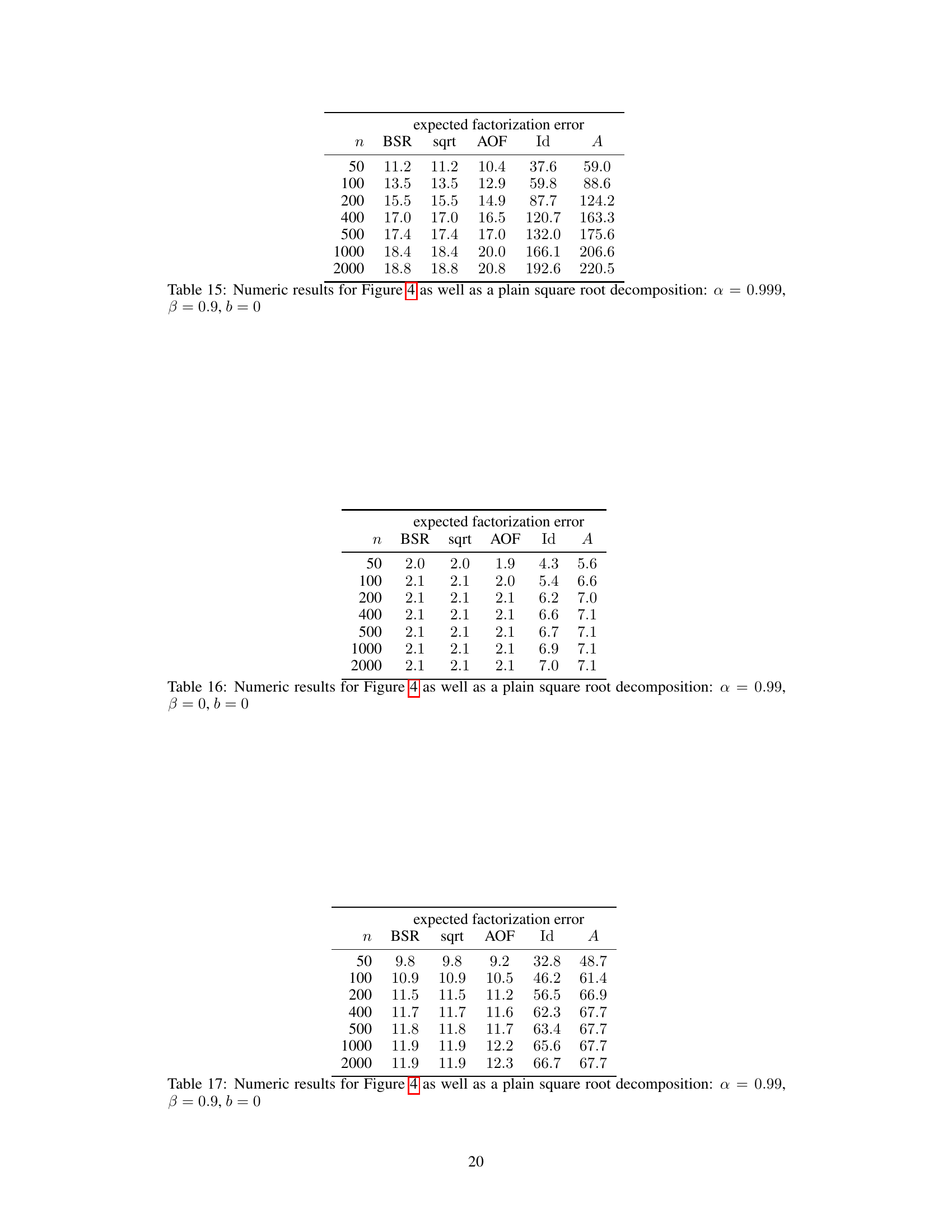

More on tables

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments shown in Figure 3 of the paper. It compares the expected factorization error for different matrix factorization methods: BSR, square root, AOF, Id, and A. The error is calculated for various workload matrix sizes (n) under specific hyperparameters (α=1, β=0, k=1, b=k/n). This illustrates the relative performance of these methods in terms of the approximation quality achieved when factoring the workload matrix.

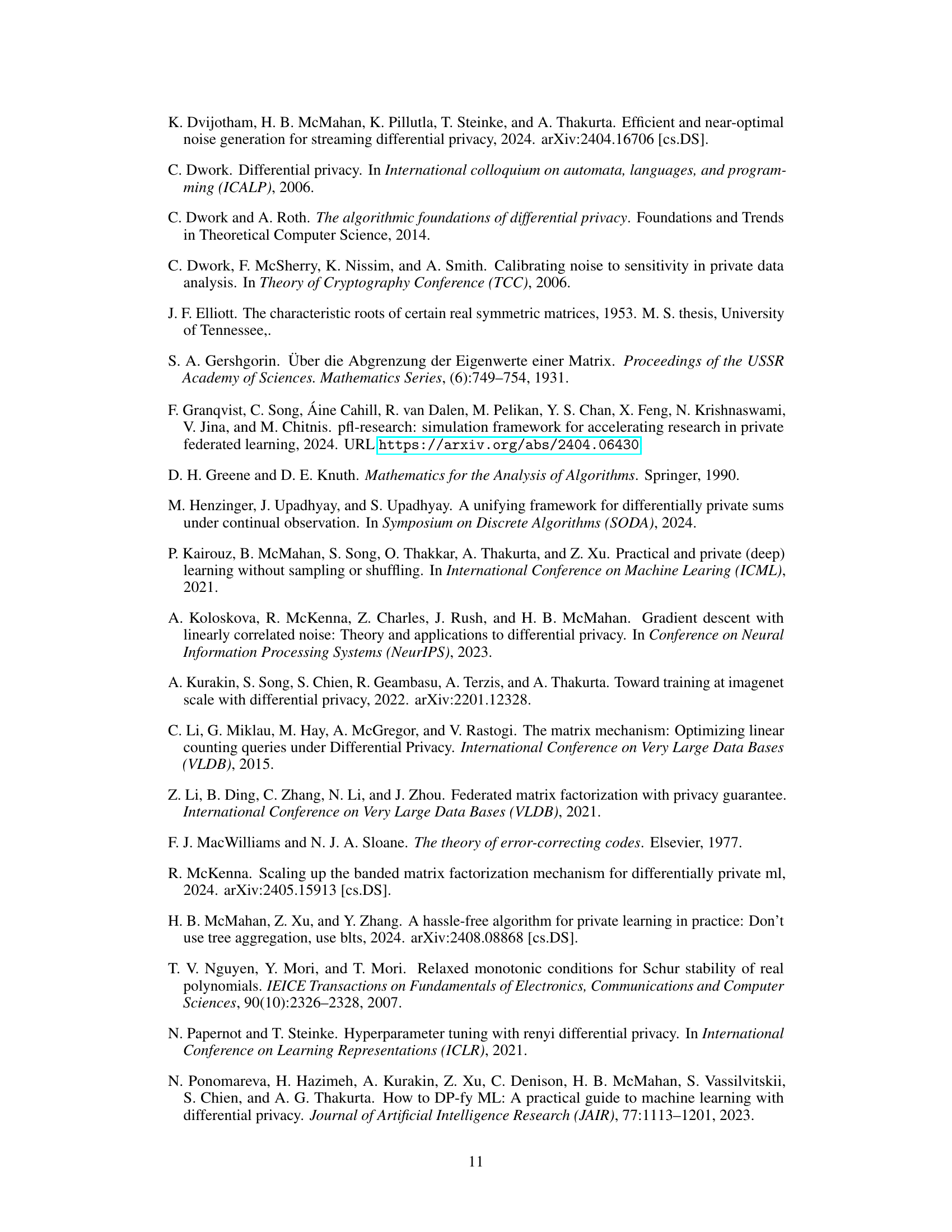

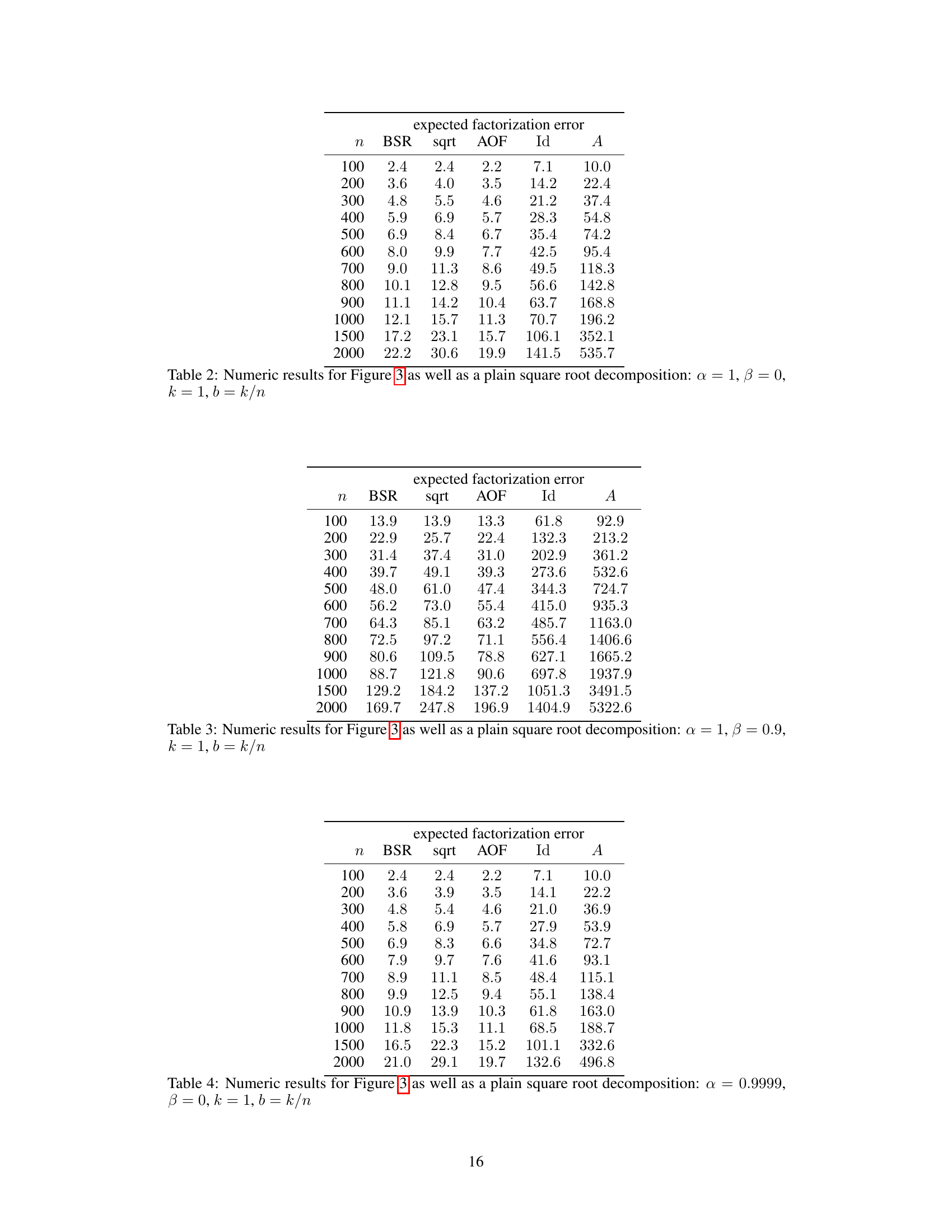

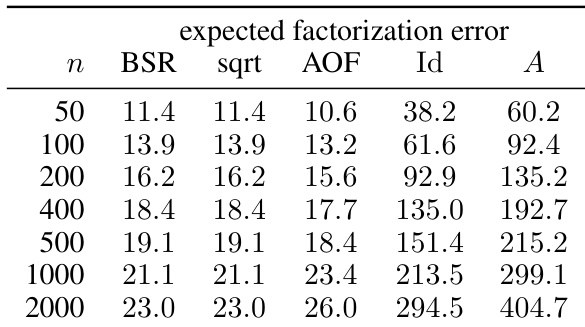

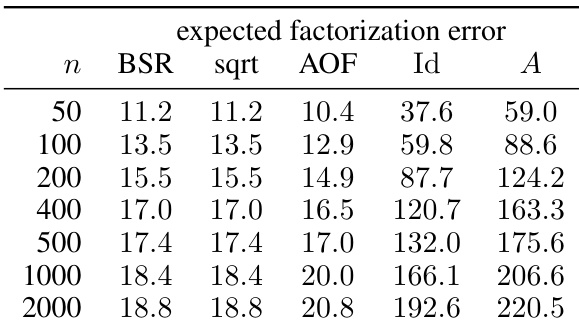

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error, comparing the banded square root (BSR) factorization with other methods such as approximately optimal factorization (AOF), identity factorization (Id), and factorization A (A). The results are categorized by workload matrix size (n) and show the error for each method under the specified settings (α = 1, β = 0.9, k = 1, b = k/n). These settings represent a specific scenario in stochastic gradient descent (SGD) model training with momentum and weight decay.

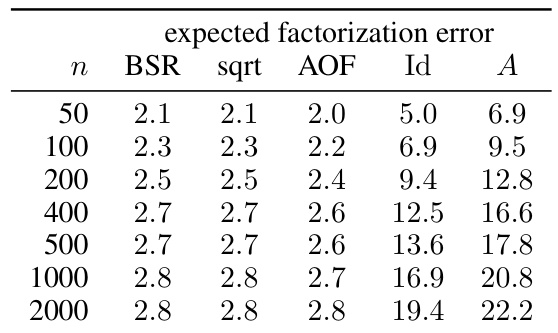

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error, comparing the proposed BSR method with the Approximately Optimal Factorization (AOF) and baseline methods. The results are shown for different workload matrix sizes (n), with α = 1 (no weight decay) and β = 0 (no momentum). The error is calculated using the Frobenius norm of the error matrix, which measures the overall approximation error of the factorization. The table specifically shows how the errors change as the matrix size is increased. The ‘sqrt’ column shows the results using a plain square root decomposition which is a common baseline.

This table presents numerical results comparing the expected factorization error for different matrix factorization methods. The workload matrices stem from SGD with momentum (β = 0.9) and weight decay (α = 1). It shows the results for different matrix sizes (n) in the single participation setting (k = 1, b = k/n). The methods compared include the banded square root (BSR) factorization, the plain square root factorization, the approximately optimal factorization (AOF), and two baselines. The privacy parameters are ε = 4 and δ = 10⁻⁵.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error, comparing the proposed BSR method against three others: a plain square root decomposition, the approximately optimal factorization (AOF), and a baseline method. The results are organized by workload matrix size (n) and show the error for each method. The values illustrate the performance of the different factorization approaches under the specific hyperparameter setting of α = 0.9999, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n (single participation). The lower the error, the better the performance of the factorization method.

This table presents numerical results from experiments evaluating the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n). The results are broken down for four different factorization methods: BSR (banded square root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity factorization), and A (baseline factorization). The settings for these experiments include α (weight decay parameter) = 1, β (momentum parameter) = 0, k (maximal number of data item participations) = 1, b (min-separation parameter) = k/n, ε (privacy parameter) = 1.8, and δ (privacy parameter) = ε/n. The table shows that BSR consistently achieves lower errors compared to the baseline methods (Id and A), and is often comparable to AOF.

This table presents numerical results comparing the expected factorization error for different matrix factorization methods. The methods compared are BSR (banded square root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity matrix), and A (workload matrix). The results are shown for different workload matrix sizes (n), specifically with parameters alpha (α) = 0.99, beta (β) = 0, k = 1 (single participation), and b = k/n. Lower values in the table indicate better approximation quality.

This table presents numerical results that validate the theoretical findings in Figure 3. It compares the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The settings used are α=1, β=0, k=1, b=k/n, ε=1.8, δ=ε/n. The ‘sqrt’ column represents a plain square root decomposition, which is used as a baseline.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of various matrix factorization methods, including BSR, square root, AOF, Id, and A. These results are obtained for different sizes (n) of the workload matrix and are visualized in Figure 3. The parameters a, β, k, and b are fixed to specific values (1, 0, 1, and k/n, respectively). The table illustrates the approximation error for each method at different problem scales.

This table presents the numeric results obtained from an experiment shown in Figure 3 of the paper. It compares the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods for specific hyperparameter settings (α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n). The methods compared include BSR (Banded Square Root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (Approximately Optimal Factorization), Id (Identity), and A (Workload Matrix). The table shows the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n). The values of ε and δ relate to the level of privacy achieved in the differentially private model training context.

This table presents numerical results comparing the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The specific setting used for this comparison is α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n. The table complements Figure 3 in the paper by providing the exact numerical values that the figure visualizes.

This table presents the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n) using various factorization methods: BSR (Banded Square Root), sqrt (square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity), and A (baseline). The results are based on the setting where α = 0.999, β = 0.9, k = 1, and b = 0. Lower error values indicate better performance.

This table presents the numerical results obtained for different workload matrix sizes (n) using four different factorization methods: Banded Square Root (BSR), plain square root, Approximately Optimal Factorization (AOF), and two baseline methods (Id and A). The expected factorization error is reported for each method. The parameters α (weight decay), β (momentum), k (maximal number of participation), and b (minimal separation) are set to 1, 0, 1, and k/n respectively. The privacy parameters ε and δ are 1.8 and ε/n respectively. The results illustrate how the approximation error changes as the size of the workload matrix increases.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods. The results are shown for different workload matrix sizes (n) and are compared across several methods: BSR (Banded Square Root), sqrt (square root), AOF (Approximately Optimal Factorization), Id (identity matrix factorization), and A (baseline factorization with A = A * Id). The values are obtained using parameter settings of alpha (α)=0.999 and beta (β)=0.9, with k=1 (single participation) and b=0. The table is part of the experimental results section. It helps to validate the theoretical findings and show the practical performance of the BSR compared to baseline and state-of-the-art methods.

This table presents the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n) using four factorization methods: BSR, square root, AOF, Id, and A. The results are for the specific setting of α (weight decay) = 1, β (momentum) = 0, k (maximal participation) = 1, and b (min-separation) = k/n. The privacy parameters (ε, δ) are also specified.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error using different factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The settings used are α = 1 (no weight decay), β = 0 (no momentum), k = 1 (single participation), and b = k/n (each data item contributes at most once). The privacy parameters are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n. The results demonstrate the relative approximation errors for each method compared to the optimal factorization (AOF).

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments for different workload matrix sizes (n). The expected factorization error is calculated for four different factorization methods: BSR (banded square root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity matrix), and A (original matrix). The experiment parameters are α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, ε = 1.18, and δ = ε/η. The results demonstrate the performance of different factorization methods and the impact of increasing the matrix size on the factorization error.

This table presents the numerical results obtained for the expected factorization error using different factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) on workload matrices from SGD with specific hyperparameters (α = 1, β = 0). The error is calculated for various sizes of workload matrices (n), considering single participation (k = 1) and repeated participation scenarios (b = k/n). The privacy parameters are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n.

This table presents numerical results that compare the expected factorization error of four different matrix factorization methods (BSR sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The hyperparameters used are α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n. The privacy parameters are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n. The results are visualized in Figure 3 of the paper. The table shows how the expected factorization error changes with increasing workload matrix size for each of the methods.

This table presents the numeric results obtained from experiments depicted in Figure 3. The experiments compare the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization techniques (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) in the setting where α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, ε = 1.8, and δ = ε/n. The table shows the error for various matrix sizes (n).

This table provides numerical values corresponding to the results shown in the bottom-left plot of Figure 5. The figure displays classification accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset with privacy parameters (ε, δ) = (8, 10⁻⁵) for a single epoch using varying batch sizes. This table breaks down the accuracy for BSR, AOF, Id, and A for different numbers of updates (50, 100, 200, 400, 500, 1000, 2000), showing the mean ± standard deviation over 5 independent training runs.

This table presents numerical results obtained from experiments comparing the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods for a specific setting of hyperparameters (α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n) and privacy parameters (ε = 1.8, δ = ε/n). The methods compared include BSR (banded square root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id (identity matrix), and A (workload matrix). The table shows the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n).

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods, including BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, and A, as shown in Figure 3 of the paper. The results are for the setting where α (weight decay parameter) = 1, β (momentum parameter) = 0, k (maximal number of data item participations) = 1, b (min-separation parameter) = k/n, and ε (privacy parameter) = 1.18ε/α. The table shows the error for different workload matrix sizes (n).

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments. The results are broken down according to the workload matrix size (n). For each size, the table lists the expected factorization error using four different methods: BSR (Banded Square Root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (Approximately Optimal Factorization), Id (baseline factorization), and A (baseline factorization). The experiment uses settings where alpha = 1, beta = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n, as specified in the caption.

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments comparing the approximation error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A). The experiment setting uses a workload matrix generated from SGD with parameters α = 1, β = 0, k=1, and b = k/n, where α is the weight decay, β is the momentum, k is the maximal number of participations, and b is the minimal separation. The privacy parameters are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n, representing the privacy level. The table shows the expected factorization error for different sizes of the workload matrix (n). The results illustrate the approximation quality of each factorization method, showing how well each method approximates the true workload matrix under the given settings.

This table presents numerical results from experiments comparing different matrix factorization methods for differentially private SGD model training. The results shown correspond to those plotted in Figure 3 for a specific setting: alpha (weight decay) =1, beta (momentum) = 0, with epsilon = 1.18ε/η. The table compares the expected approximation error for BSR (Banded Square Root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (Approximately Optimal Factorization), Id (identity matrix), and A (workload matrix) factorizations, across varying numbers (n) of update steps. Lower approximation error is better. This demonstrates the relative performance of these factorizations under specific hyperparameter conditions.

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments comparing the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The experimental setup involves single data participation (k=1), no momentum (β=0), and no weight decay (α=1). The results are shown for both the banded square root factorization (BSR) and for the ordinary square root. The table also includes the results for other baseline methods for comparison.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) under specific settings: α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, ε = 1.18 ε/η. The results are displayed for various workload matrix sizes (n). The ‘sqrt’ column likely indicates the results obtained using a plain square root decomposition. The table shows that BSR demonstrates comparable error to the AOF, generally outperforming other baseline methods. These results visually correspond to those illustrated in Figure 3 of the paper.

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments comparing different matrix factorization techniques, specifically the banded square root factorization (BSR) and others like AOF, Id, and A. The results are shown for different workload matrix sizes (n). The setup uses α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n, which represent specific parameter settings for stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum and weight decay. The error metrics used are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n, representing differential privacy parameters.

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error, comparing BSR, square root, AOF, Id, and A methods across various workload matrix sizes (n). The results are based on the setting described in Figure 3, with α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n. The privacy parameters used are ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/n. The table helps to understand the performance of each matrix factorization method in terms of approximation error.

This table presents the numerical results for the expected factorization error of four different factorization methods (BSR sqrt, AOF, Id, A) applied to the workload matrices from Figure 3. The experimental setting is for single participation (k=1) with α=1, β=0 and b=k/n. The privacy parameters are set to ε=1.8 and δ=ε/η. The results show the values of the expected factorization error for various workload matrix sizes (n).

This table presents the numerical results obtained from experiments comparing different matrix factorization methods for a specific setting where the workload matrix is characterized by α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, with privacy parameters ε = 1.18, and δ = ε/η. The results show the expected factorization error, a metric reflecting the quality of the factorization obtained by each method. The methods compared include BSR (banded square root), sqrt (plain square root), AOF (approximately optimal factorization), Id, and A (baseline factorizations). The table shows how the error changes as the workload matrix size, n, increases.

This table presents numerical results on the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n). It compares the performance of the Banded Square Root (BSR) factorization with the Approximately Optimal Factorization (AOF) and baseline methods (Id and A). The settings are α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, ε = 1.8, and δ = ε/n, which represent specific parameters related to the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm used in differentially private model training.

This table presents the numerical results obtained from the experiments shown in Figure 3. It compares the expected factorization error for different workload matrix sizes (n) using four methods: the banded square root (BSR) factorization, the plain square root factorization (sqrt), the approximately optimal factorization (AOF), and the baseline factorizations (Id, A). The hyperparameters used are α=1, β=0, k=1, b=k/n, ε=1.8, δ=ε/η. The results illustrate the relative performance of each method in terms of the approximation error as the workload matrix size increases.

This table shows the numeric results for the expected factorization error of the banded square root factorization (BSR), approximately optimal factorization (AOF), and baseline factorizations (Id and A). These results are obtained for different workload matrix sizes (n) with specific hyperparameters: α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, and b = k/n. The privacy parameters are set to ε = 1.8 and δ = ε/η. The table complements Figure 3, providing numerical values corresponding to the results shown graphically in the figure.

This table presents numerical results obtained from experiments comparing different matrix factorization methods. It includes the expected factorization error, calculated using the BSR factorization, the square root factorization, the AOF factorization, the identity factorization, and the baseline factorization. The experiment setting involves the parameters α=1, β=0, k=1, and b=k/n. The privacy parameters used are ε=1.8 and δ=ε/n.

This table presents the numerical results obtained for the expected factorization error using different factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for varying workload matrix sizes (n). The results are based on Figure 3 from the paper and uses a plain square root decomposition with specific hyperparameter settings (α = 1, β = 0, k = 1, b = k/n, ε = 1.8, δ = ε/n). The error is the expected approximation error, and the table shows how the performance varies for different workload sizes. The methods compared include the proposed Banded Square Root (BSR) factorization and several baselines (plain square root, approximately optimal factorization (AOF), identity matrices).

This table presents numerical results for the expected factorization error of different matrix factorization methods (BSR, sqrt, AOF, Id, A) for various workload matrix sizes (n). The setting used is single participation (k=1), with weight decay (α=1) and no momentum (β=0). The error is calculated for the square root decomposition, and the privacy parameter ε is set to 1.18ε/α.

Full paper#