↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems can be modeled as Vehicle Routing Problems (VRPs), which often involve complex constraints that are difficult for existing neural methods to handle effectively. Current neural approaches rely on feasibility masking, but this approach struggles with complex constraints where checking feasibility itself is computationally expensive. This paper addresses this limitation.

The paper introduces a new framework, called Proactive Infeasibility Prevention (PIP), which uses the Lagrangian multiplier method and a novel preventative infeasibility masking technique to guide the search towards feasible solutions more effectively. It also introduces an enhanced version called PIP-D, which uses an auxiliary decoder and adaptive strategies to further improve efficiency. Extensive experiments demonstrate that PIP and PIP-D significantly improve solution quality and reduce infeasibility rates across various VRP benchmarks and neural models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the critical challenge of handling complex constraints in vehicle routing problems (VRPs), a ubiquitous issue limiting the applicability of neural methods in real-world logistics. The proposed PIP framework offers a generic solution boosting various neural approaches, making it highly relevant to researchers working on VRP optimization and other combinatorial problems. Its findings pave the way for more efficient and accurate solutions, impacting logistics, supply chain management and beyond.

Visual Insights#

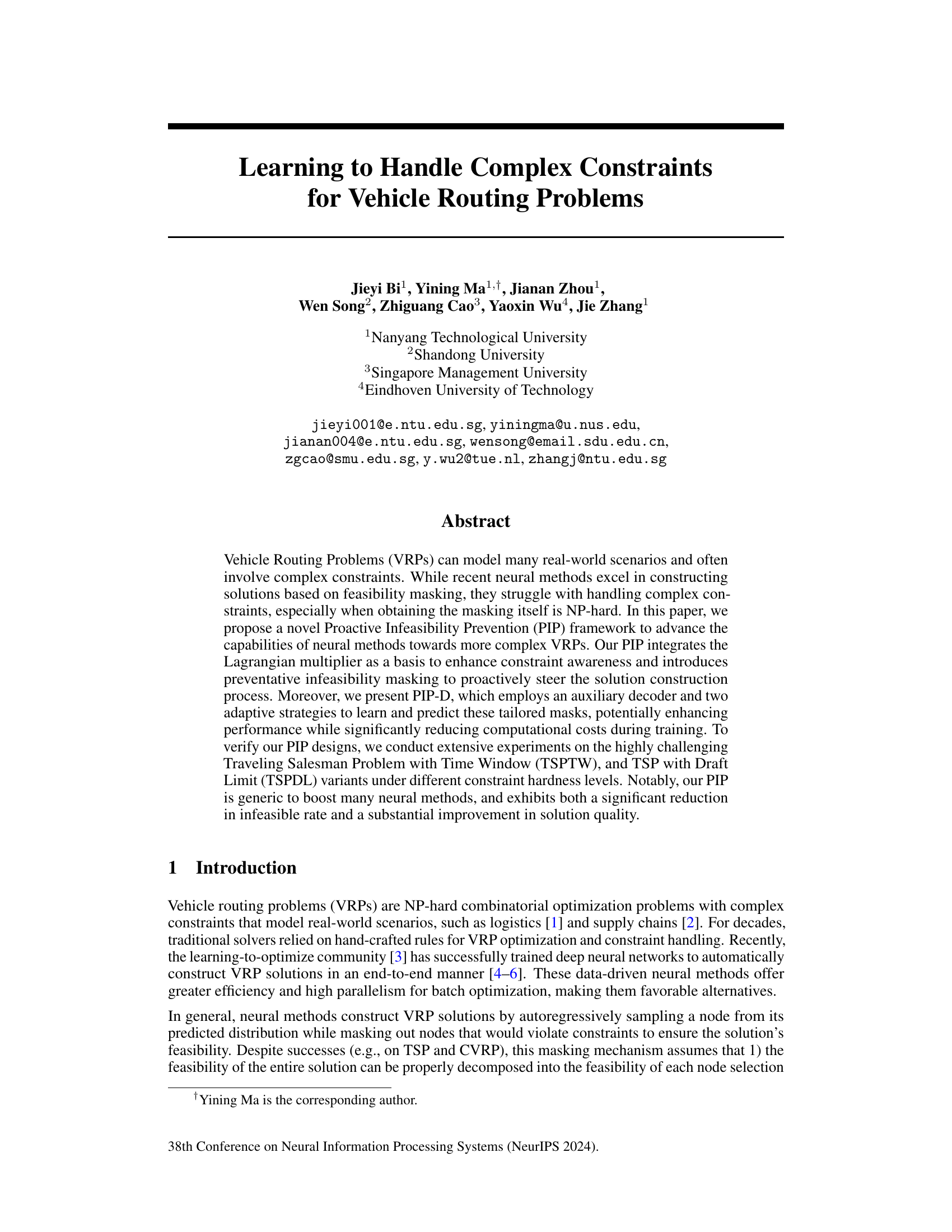

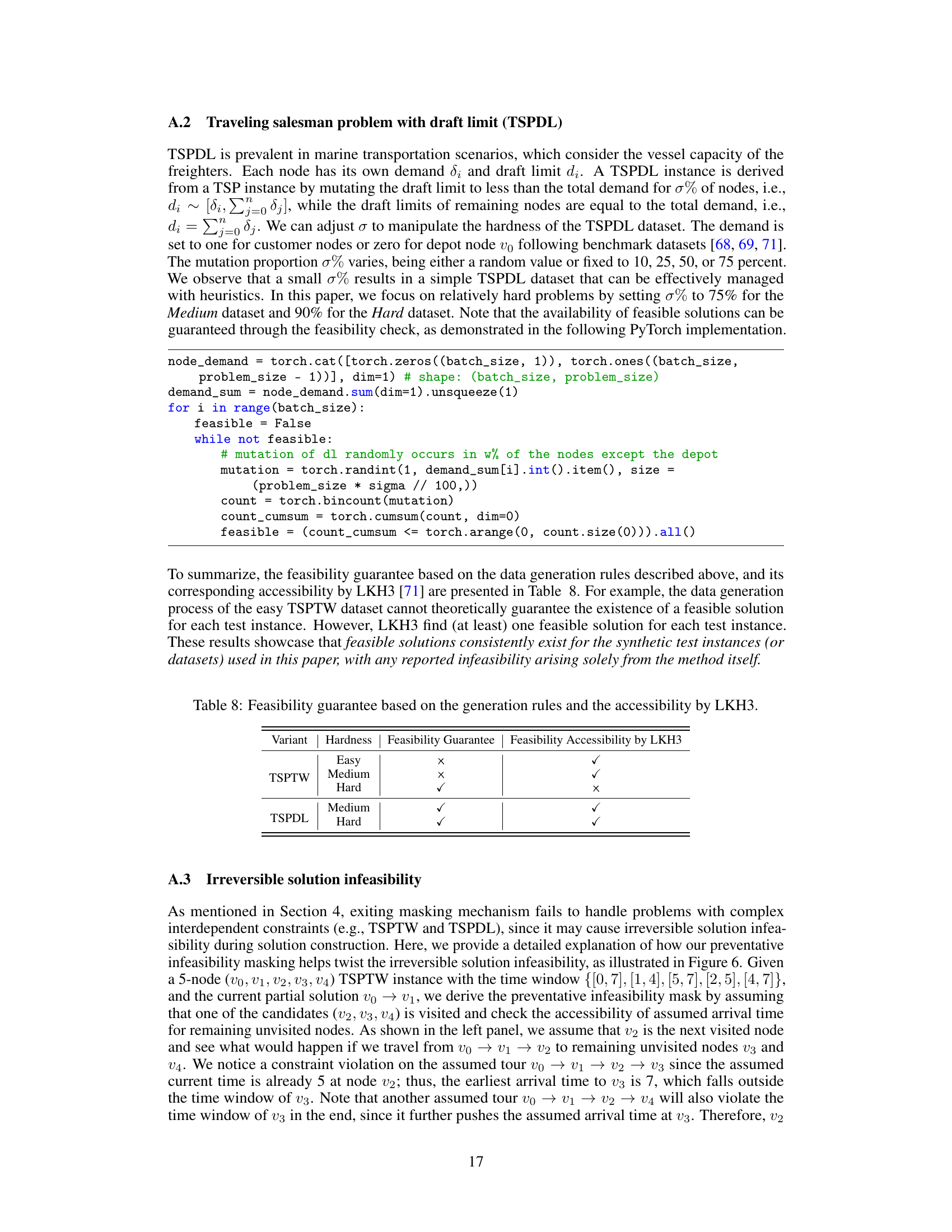

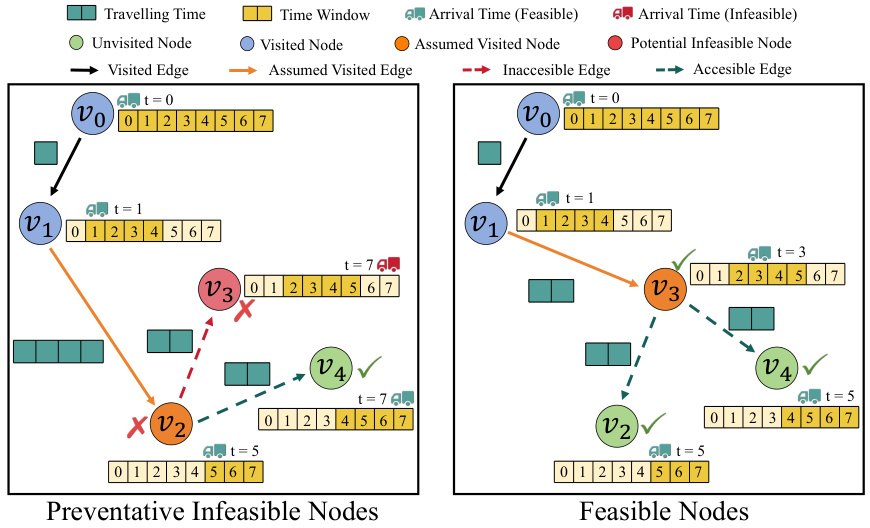

This figure demonstrates the limitations of existing feasibility masking methods in solving VRPs with complex constraints, specifically using TSPTW as an example. The left three panels show how locally feasible node selections (v2 and v3 after selecting v0 and v1) can lead to an irreversible global infeasible solution (when v3 is chosen). The right panel illustrates the NP-hard nature of computing global feasibility masks which need to account for all future impacts of a node selection.

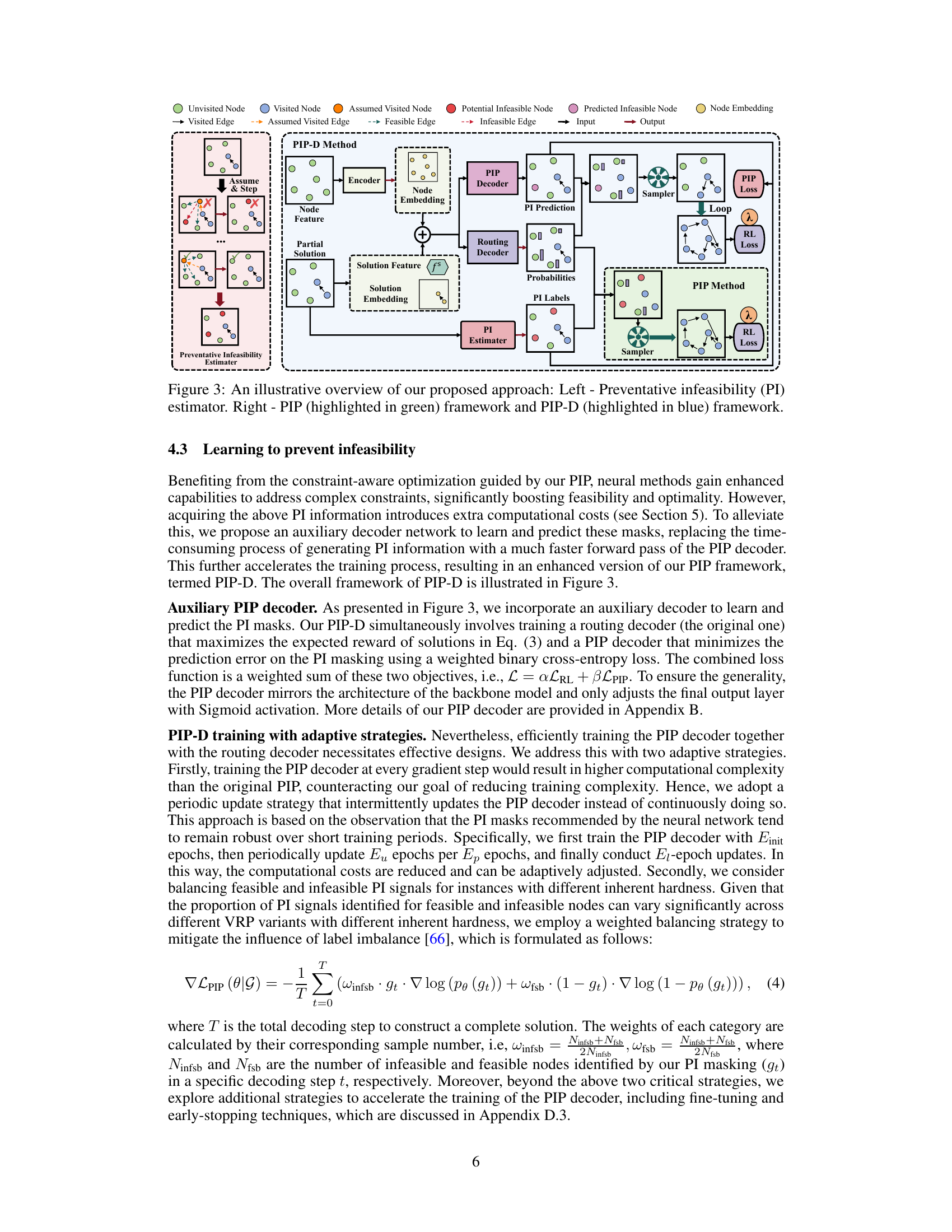

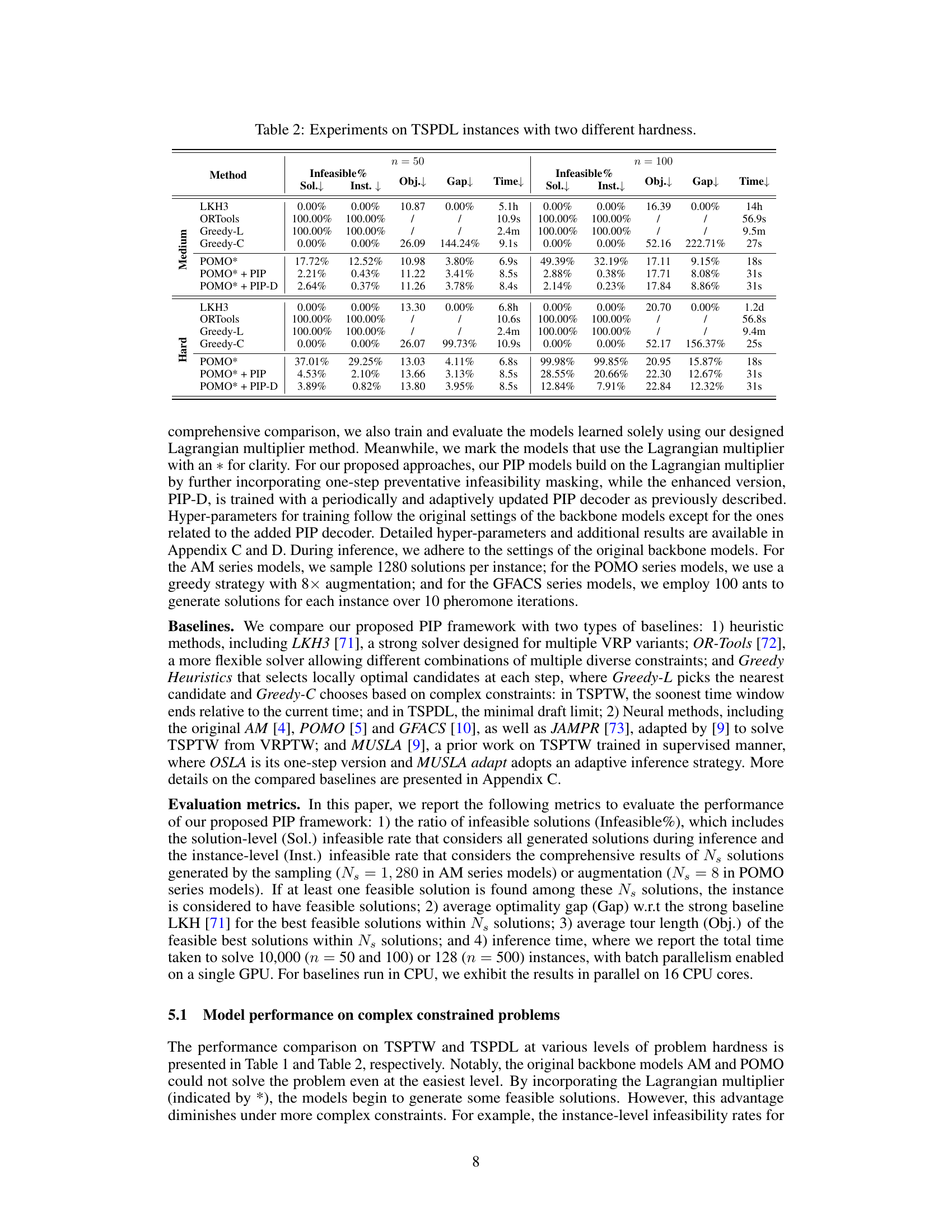

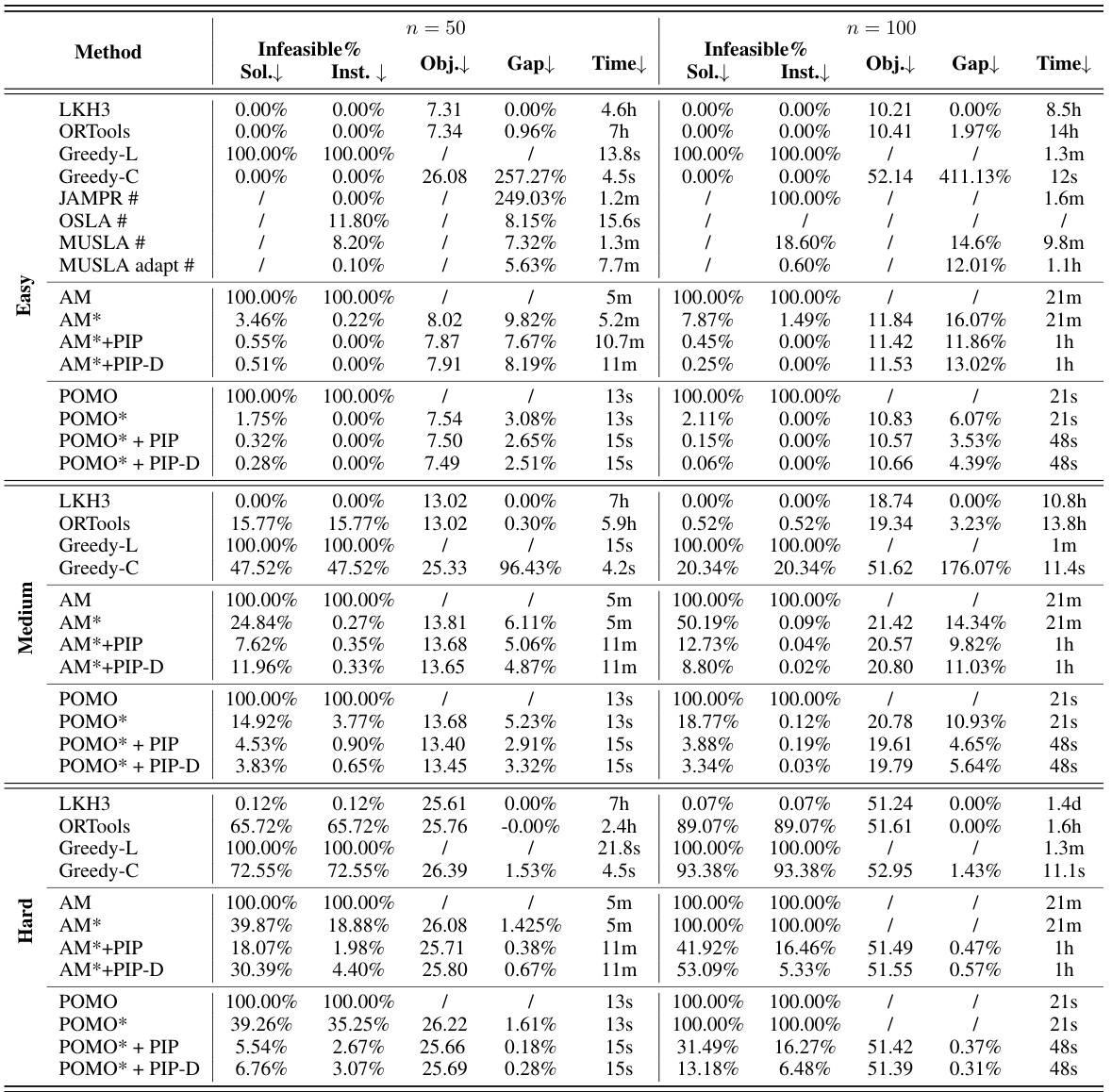

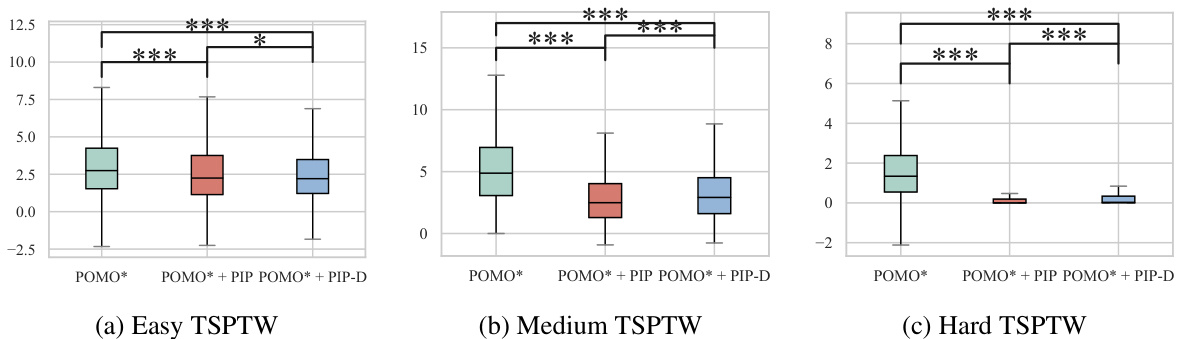

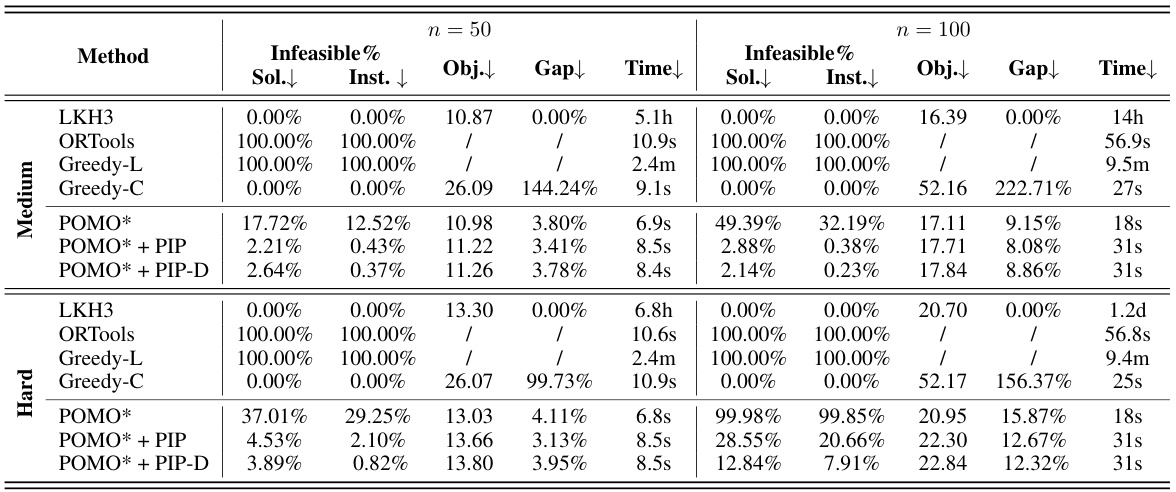

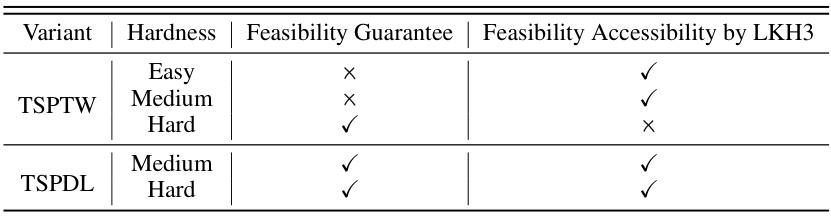

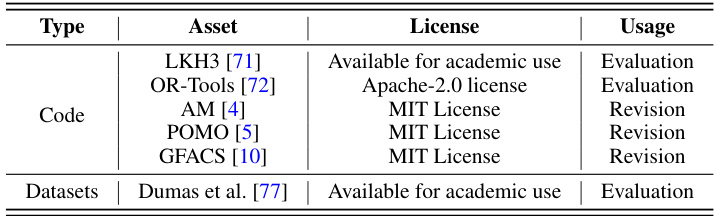

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). It compares the performance of various methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy), previous neural network approaches (AM, POMO, GFACS, JAMPR, OSLA, MUSLA), and the proposed PIP and PIP-D methods. The metrics reported include the infeasible rate (both solution and instance level), optimality gap, objective value (tour length), and computation time. The table demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed PIP and PIP-D frameworks in handling complex constraints, particularly in harder problem instances.

In-depth insights#

Constraint Handling#

The effective handling of constraints is crucial in solving vehicle routing problems (VRPs). Traditional approaches relied on hand-crafted rules, which struggled with complex, interdependent constraints. Neural methods offer a more flexible approach, often employing feasibility masking to prevent the construction of infeasible solutions. However, generating accurate feasibility masks can itself be NP-hard for complex VRPs. This paper tackles this challenge by proposing a Proactive Infeasibility Prevention (PIP) framework. PIP incorporates Lagrangian multipliers to improve constraint awareness during the solution construction process, guiding the search toward feasible regions. Additionally, a novel preventative infeasibility masking technique proactively steers the search, avoiding irreversible infeasible paths. The introduction of an auxiliary decoder further enhances PIP’s efficiency, learning to predict the masks and reducing computational costs during training. The framework’s effectiveness is empirically demonstrated across multiple challenging VRP variants, significantly improving solution quality and feasibility. The generic nature of PIP, as demonstrated by successful integration with various neural architectures, makes it widely applicable for improving constraint handling in numerous complex optimization problems.

Neural VRP Solvers#

Neural Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) solvers represent a significant advancement in addressing complex logistics challenges. These methods leverage the power of deep learning to automatically construct near-optimal solutions, often surpassing traditional methods in efficiency and scalability. Constructive solvers build solutions iteratively, learning policies to guide the selection of nodes while respecting constraints, while iterative solvers refine initial solutions through learned refinement policies. A key challenge involves handling complex interdependent constraints where a node’s selection impact future choices. Current approaches often rely on feasibility masking, but this can be computationally expensive and may fail with highly complex scenarios. Future research should focus on improving constraint handling techniques, developing more robust and adaptable methods, exploring the potential of reinforcement learning with advanced architectures, and addressing challenges related to scalability and generalization to diverse real-world problems. The field shows tremendous promise for optimizing complex logistical operations while opening avenues for further innovation in solving NP-hard combinatorial optimization problems.

PIP Framework#

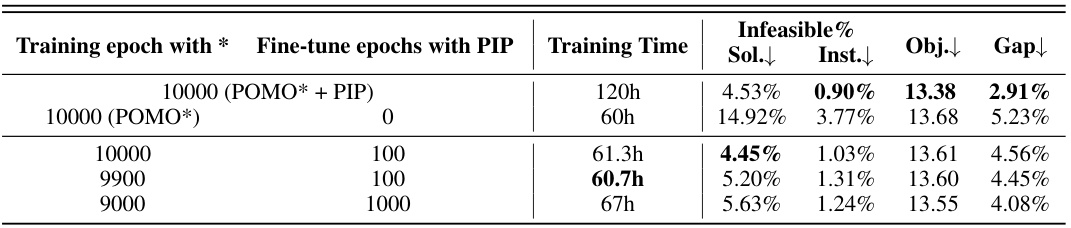

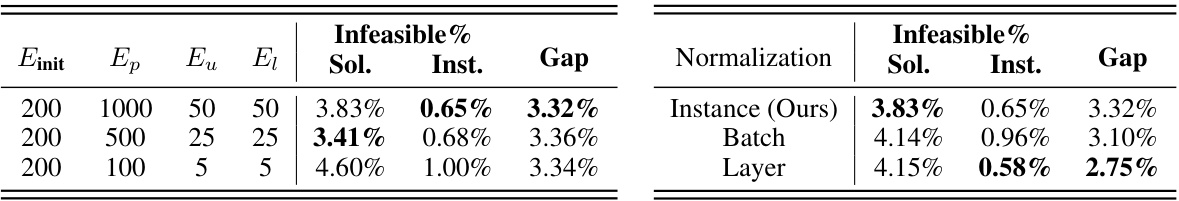

The Proactive Infeasibility Prevention (PIP) framework is a novel approach to enhance neural methods for solving complex Vehicle Routing Problems (VRPs). PIP addresses the limitations of traditional feasibility masking by integrating Lagrangian multipliers to improve constraint awareness. Instead of relying solely on masking infeasible actions, PIP proactively steers the solution construction process towards feasibility. This is achieved through preventative infeasibility masking, which anticipates and prevents infeasible actions from being chosen. A key innovation is PIP-D, which introduces an auxiliary decoder and adaptive training strategies to efficiently learn and predict these tailored masks, significantly reducing computational costs. The overall framework demonstrates a substantial improvement in solution quality and a significant reduction in infeasible solutions across various VRP variants and neural architectures. The adaptability and generic nature of PIP to enhance many existing neural solvers is a notable strength. The effectiveness of PIP and PIP-D is validated through extensive experiments, showcasing a significant improvement over traditional methods.

Adaptive PIP-D#

An adaptive PIP-D framework for addressing complex Vehicle Routing Problems (VRPs) would likely involve dynamically adjusting the preventative infeasibility masking based on the problem’s characteristics and the solution construction progress. This could entail learning to predict masks not just locally, but also considering global feasibility and potential future constraint violations. Adaptive strategies might involve periodically updating the PIP decoder’s parameters to better balance exploration and exploitation. This could enable the system to handle varying constraint hardness levels efficiently. Another aspect could focus on contextual adaptation: the system may learn to adjust its masking strategy depending on the current state of the solution being constructed (e.g., the remaining time window capacity in TSPTW, or cumulative draft limit in TSPDL). A key element will be efficient computation: any adaptive mechanism must avoid excessive computational overhead during both training and inference to be practical. Therefore, the design will likely leverage efficient neural network architectures and carefully designed training procedures. Finally, a crucial element of adaptive PIP-D would be comprehensive evaluation across diverse VRP benchmarks and constraint levels to demonstrate its effectiveness in handling complex real-world scenarios.

Future Research#

The paper’s “Future Research” section could explore several promising avenues. Extending PIP to encompass a wider range of neural architectures and VRP variants is crucial to establish its generalizability and practical impact. Investigating more sophisticated masking strategies, potentially incorporating multi-step or global feasibility considerations, could improve performance on highly complex problems. A deeper investigation into the adaptive strategies within PIP-D, especially the periodic updates and weighted balancing mechanisms, is also warranted. This could involve exploring alternative update schedules or weighting schemes, perhaps informed by theoretical analysis. Finally, a thorough exploration of the hybrid approach combining PIP with established heuristics like LKH3 is needed. This could lead to a more practical and efficient solution for real-world applications, combining the strengths of neural methods with the effectiveness of classical heuristics. The overall aim should be to make the framework even more robust, efficient, and readily adaptable to a wider array of practical problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

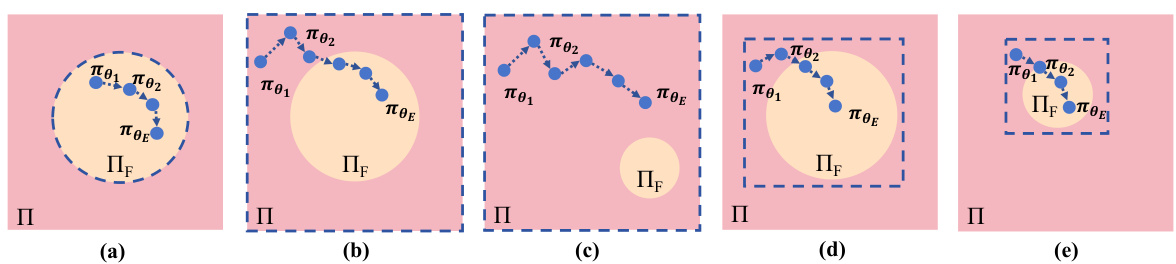

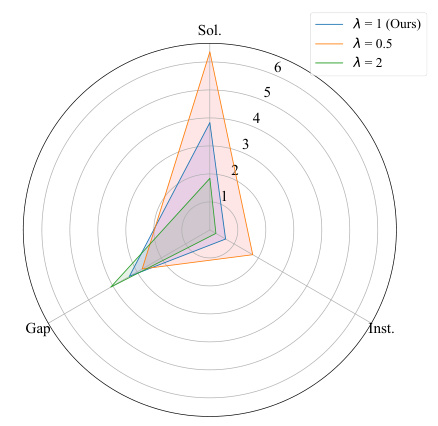

This figure illustrates the policy optimization trajectories for different constraint handling methods on VRPs with varying difficulty levels. It compares feasibility masking, Lagrangian multipliers, and the proposed PIP method. The orange circle represents the feasible policy space, while the dotted line shows the actual search space explored by the neural network’s policies. The panels (a), (b), and (d) show easy problem instances, while (c) and (e) depict hard ones, highlighting how PIP effectively constrains the search space to near-feasible regions, especially in challenging scenarios.

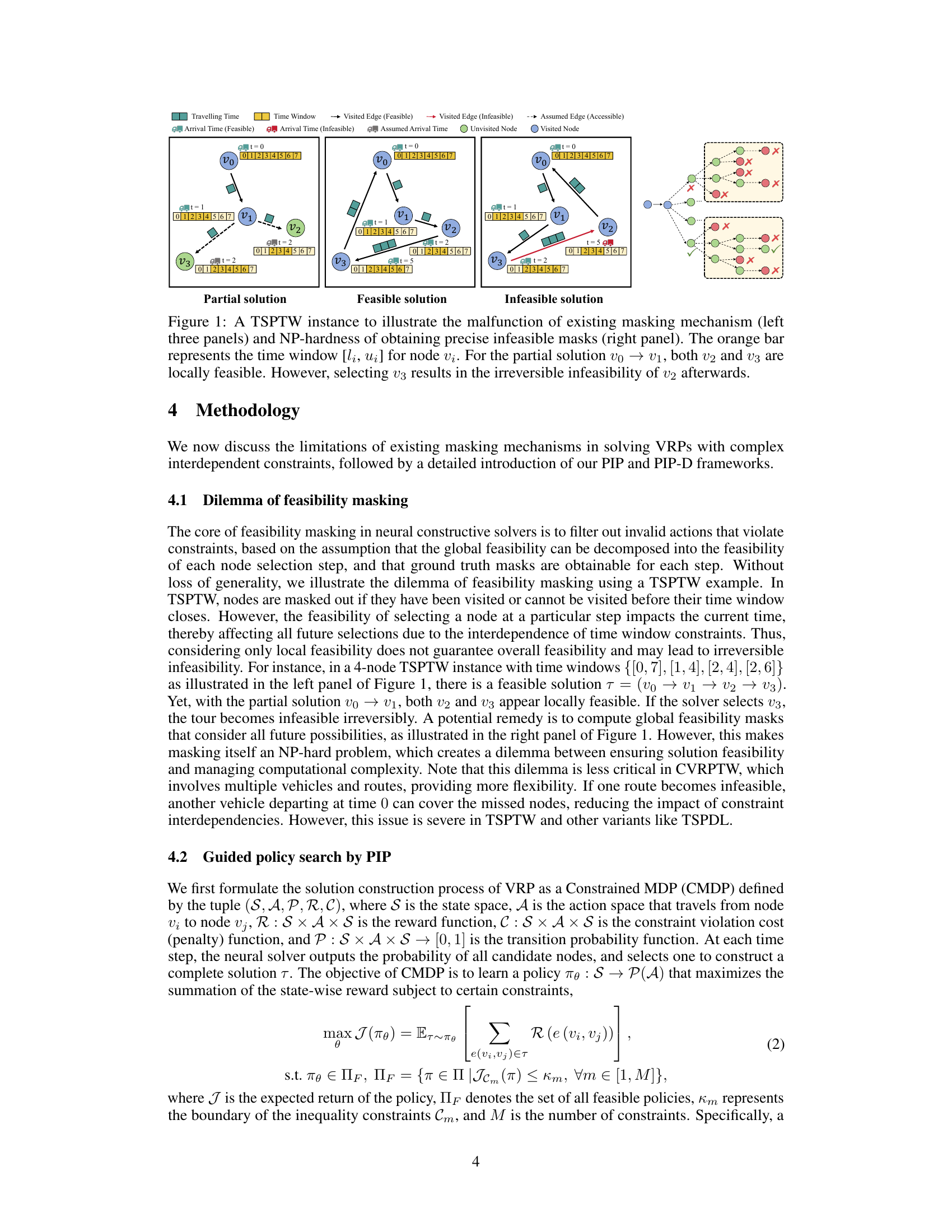

This figure illustrates the proposed Proactive Infeasibility Prevention (PIP) and its enhanced version PIP-D. The left panel shows the preventative infeasibility estimator, which identifies potentially infeasible nodes during the solution construction process. The right panel details the PIP and PIP-D frameworks. Both leverage an auxiliary decoder to predict the preventative infeasibility masks, reducing computational costs. However, PIP-D incorporates adaptive strategies to balance feasible and infeasible masking information and periodically update the model, leading to improved performance, particularly on larger and more constrained problems. Both methods integrate the Lagrangian multiplier method for enhanced constraint awareness.

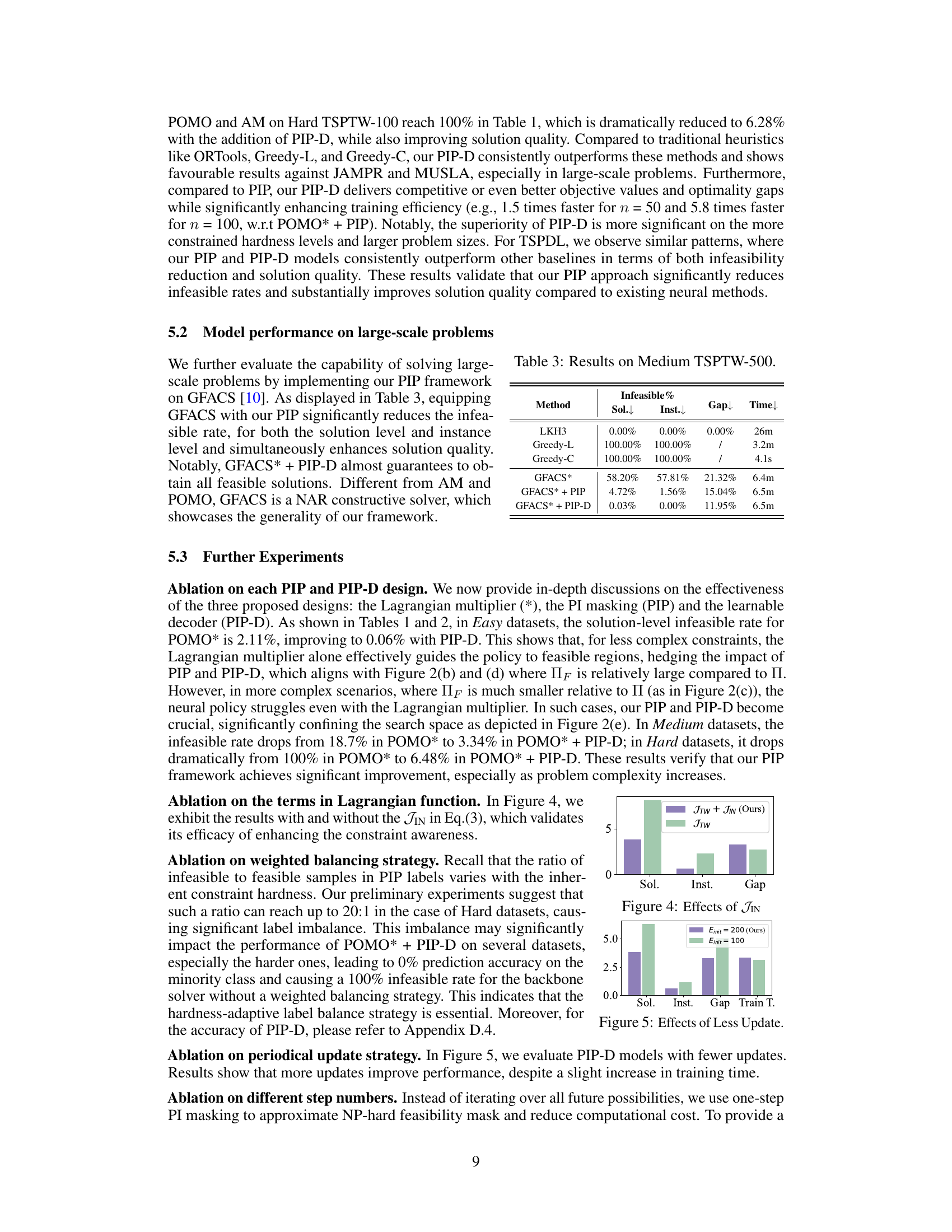

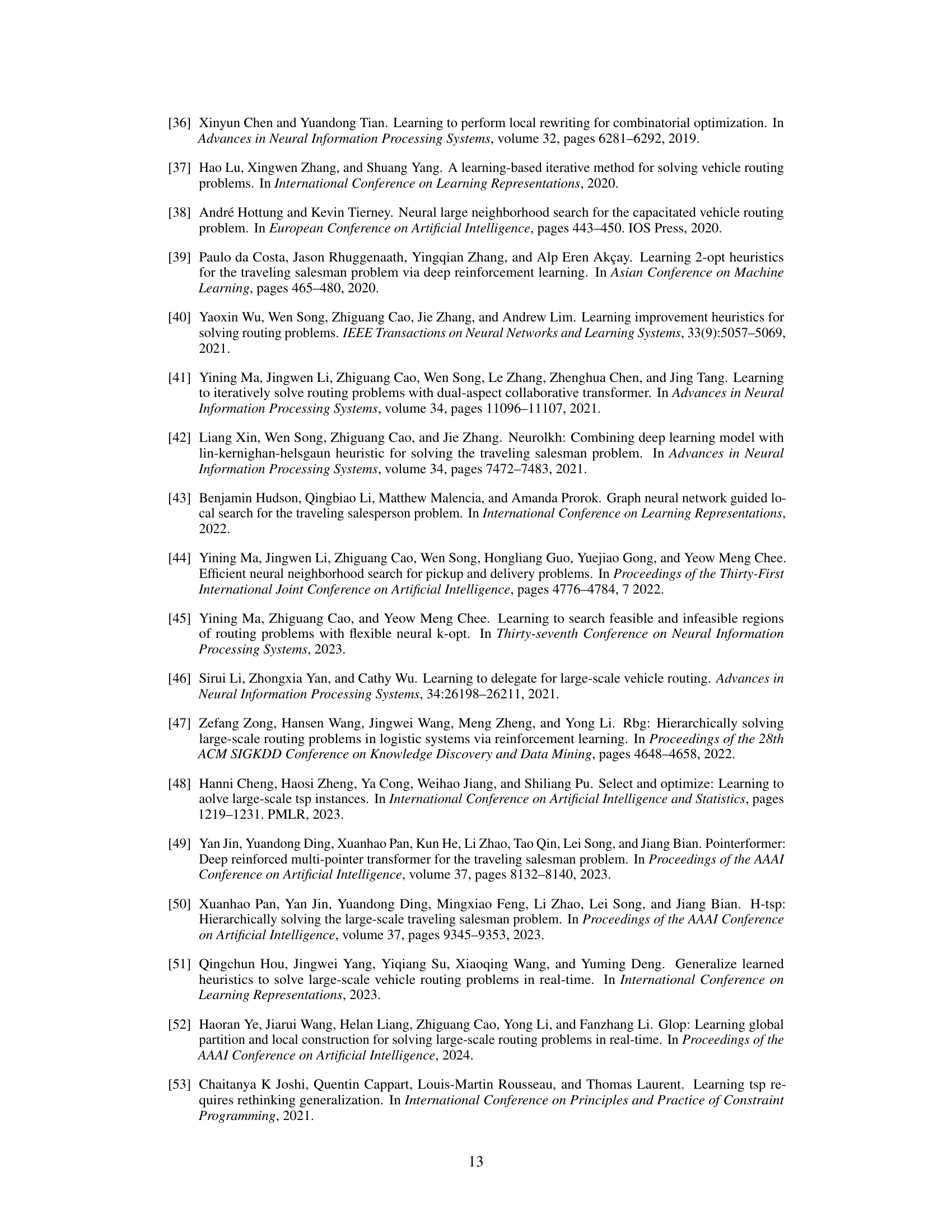

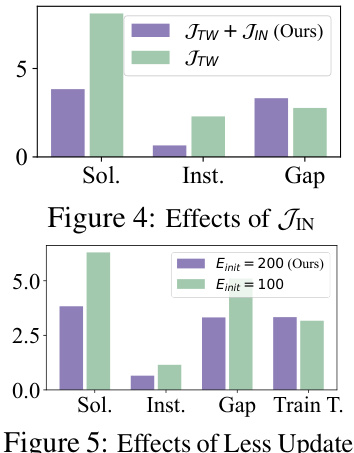

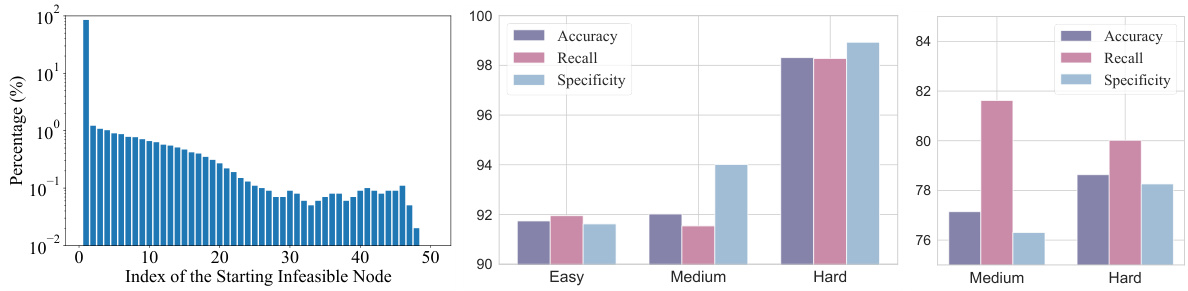

The bar chart compares the model performance with and without the JIN term added to the Lagrangian function, demonstrating the impact of JIN on improving solution feasibility, reducing infeasible rates, and optimizing the optimality gap.

This figure demonstrates the limitations of existing feasibility masking mechanisms in handling complex interdependent constraints in vehicle routing problems (VRPs), specifically using a Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) example. The left panels show that considering only local feasibility when selecting a node can lead to irreversible infeasible solutions, as the choice of one node impacts the feasibility of subsequent nodes due to time window constraints. The right panel illustrates that obtaining precise infeasible masks considering all future impacts is an NP-hard problem.

This figure compares the policy optimization trajectories of different constraint handling methods for VRPs with varying difficulty levels. Feasibility masking (a) confines the search to feasible regions but struggles with complex constraints. Lagrangian multipliers (b,c) improve constraint awareness but may still leave a large infeasible search space. The proposed PIP framework (d,e) combines the Lagrangian multiplier with preventative infeasibility masking, significantly reducing the infeasible search space and enhancing solution quality in both easy and hard instances.

This figure shows the instance-level infeasibility rate over time for three different methods: LKH3, POMO*+PIP-D, and a hybrid approach combining POMO*+PIP-D with LKH3. The graph illustrates that the hybrid approach and POMO*+PIP-D significantly reduce the infeasibility rate compared to LKH3, particularly within the first few seconds of the inference process. The inset graph provides a zoomed-in view of the initial few seconds, highlighting the dramatic improvement in the first part of the solution construction process. The dotted line is a visual aid to emphasize the contrast between the methods’ performance.

This figure illustrates the limitations of existing feasibility masking mechanisms in handling complex interdependent constraints in Vehicle Routing Problems (VRPs), specifically focusing on the Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW). The left panels depict how a locally feasible node selection can lead to an irreversible infeasible solution later in the process due to the interconnected nature of time window constraints. The right panel visually demonstrates that determining globally feasible masks accounting for all future impacts is an NP-hard problem. This highlights the masking dilemma mentioned in the paper.

This figure illustrates the concept of preventative infeasibility masking using a TSPTW example. It demonstrates how considering only local feasibility can lead to irreversible infeasibility during the solution construction process. The figure shows that choosing a node that appears locally feasible can render other nodes inaccessible due to time window constraints, preventing a complete feasible solution from being constructed. Preventative infeasibility masking helps identify such situations proactively, steering the search towards near-feasible regions, thus enhancing the effectiveness of constraint handling in neural solvers.

This figure demonstrates the limitations of existing feasibility masking mechanisms in handling complex constraints in vehicle routing problems (VRPs). The left three panels illustrate how local feasibility checks are insufficient to guarantee overall feasibility. A seemingly feasible local choice can lead to an infeasible solution. The right panel shows that determining true infeasible masks is computationally intractable (NP-hard), because it requires considering all future possibilities, which makes the masking problem itself NP-hard.

More on tables

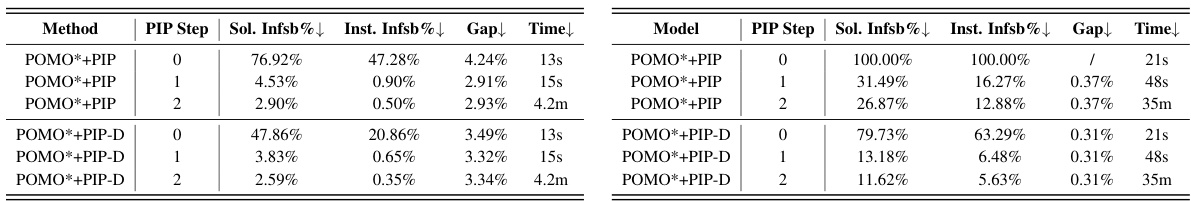

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). The results are compared across several methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, greedy heuristics), prior neural approaches (AM, POMO, JAMPR, MUSLA), and the proposed methods (AM*+PIP, AM*+PIP-D, POMO*+PIP, POMO*+PIP-D). Metrics reported include the percentage of infeasible solutions (Infeasible%, both at the solution and instance level), objective function values (Obj.), optimality gap (Gap) relative to the LKH3 solver, and computation time (Time). The table shows how the proposed methods improve solution feasibility and quality compared to existing approaches, particularly for more challenging instances.

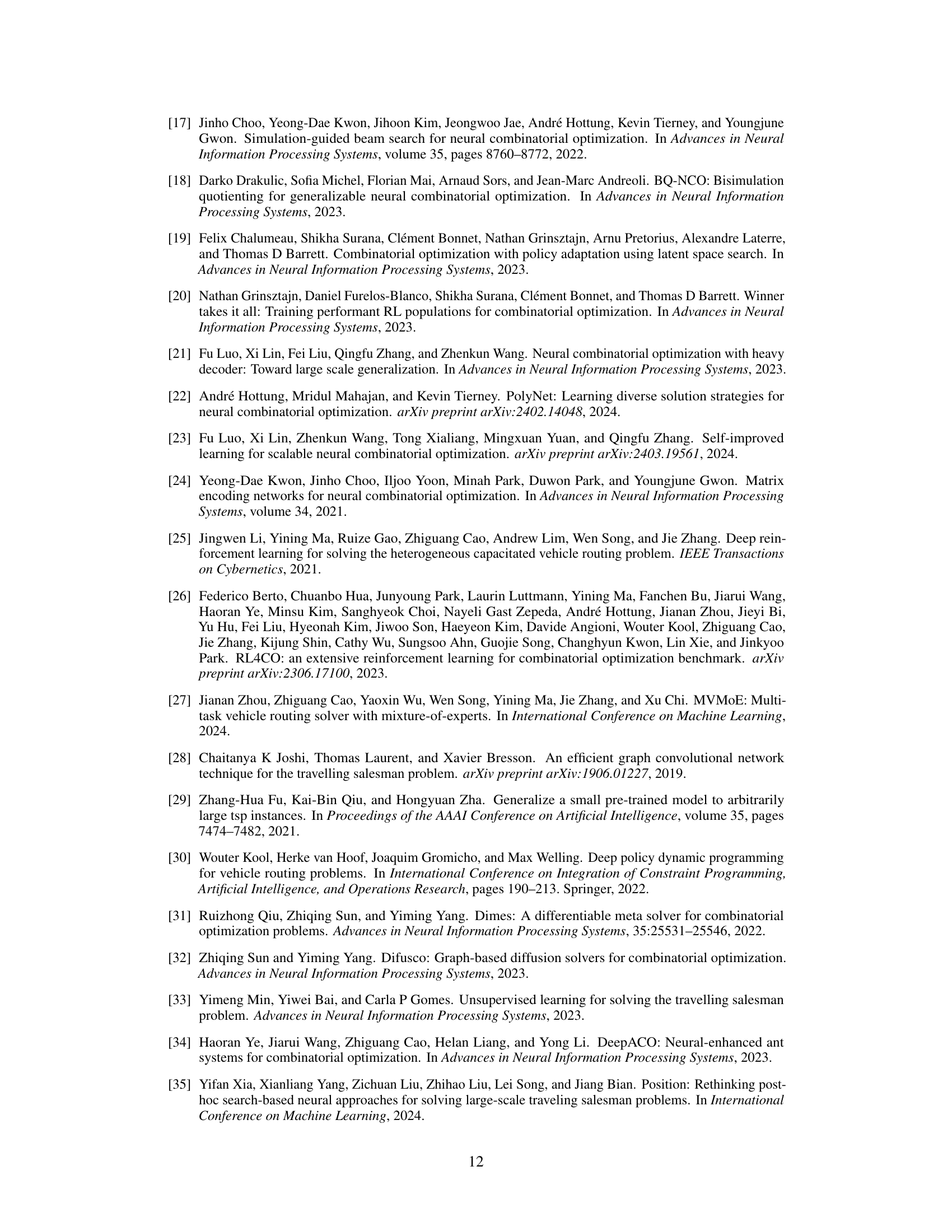

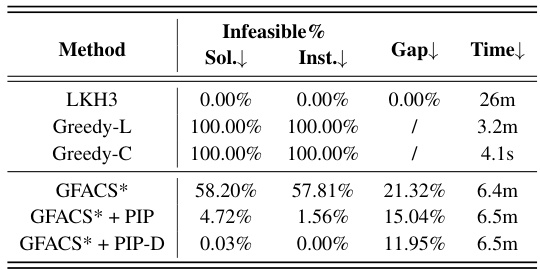

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on medium-level TSPTW instances with 500 nodes. It compares the performance of three methods: LKH3, GFACS*, and GFACS* + PIP-D. The metrics shown are infeasible rate at the solution and instance levels, optimality gap compared to LKH3, and inference time. This table highlights the effectiveness of the PIP-D framework in improving the feasibility and solution quality of the GFACS* method, especially on larger and more complex problem instances.

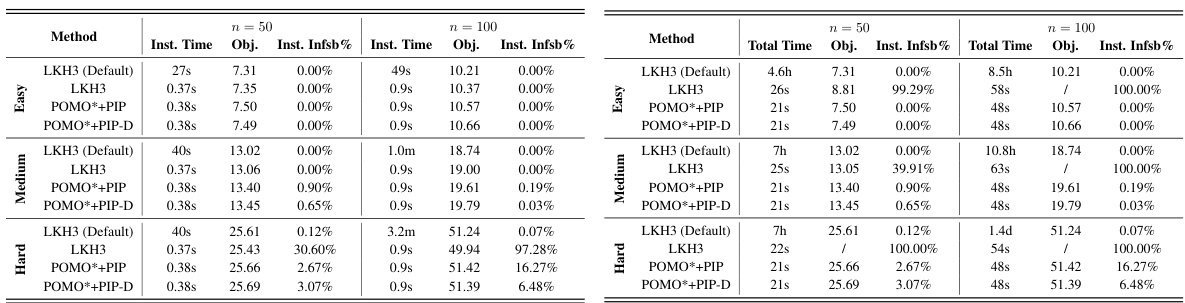

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with varying hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods are compared, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy-L, Greedy-C), prior neural approaches (JAMPR, OSLA, MUSLA, MUSLA adapt), and the proposed methods (AM*+PIP, AM*+PIP-D, POMO*+PIP, POMO*+PIP-D). The table shows the infeasible rate (at both solution and instance level), solution quality (objective value and optimality gap), and computation time for each method across different problem hardness levels. The results demonstrate that the proposed PIP and PIP-D methods significantly improve both solution feasibility and quality compared to baseline approaches.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on TSPTW instances with three different levels of hardness: Easy, Medium, and Hard. The table compares various methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy approaches) and neural network-based methods (AM, POMO, and their variants with the proposed PIP and PIP-D frameworks), across different problem scales (n=50, n=100). The metrics reported are the infeasibility rate (both at the solution and instance levels), the solution quality (optimality gap and objective value), and the computation time. The superscript † indicates a footnote.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on TSPTW instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy), a previous neural approach (MUSLA), and the proposed PIP and PIP-D methods applied to several neural network architectures (AM, POMO), are compared. The table shows the infeasible rate (both solution-level and instance-level), solution objective value (relative gap to the optimal solution obtained by LKH3), and the computational time taken for each method on each instance type. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of PIP and PIP-D in significantly reducing infeasible solutions and improving solution quality, particularly on harder instances.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on TSPTW instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods are compared, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy), prior neural approaches (AM, POMO, JAMPR, MUSLA), and the proposed methods (AM*+PIP, AM*+PIP-D, POMO*+PIP, POMO*+PIP-D). For each method, the table shows the infeasible rate (percentage of infeasible solutions), average solution objective value (Obj.), average optimality gap (Gap) compared to LKH3, and average solution time. The † symbol indicates that the average results are reported for instances where feasible solutions were found.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on TSPTW instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods are compared, including traditional solvers (LKH3, ORTools), greedy heuristics, and neural network-based methods (AM, POMO, and their variants with PIP and PIP-D). The table shows the infeasible rate (percentage of infeasible solutions), the average objective value (obtained solution quality), optimality gap, and computation time for each method and hardness level. The asterisk (*) denotes that the model is trained with the Lagrangian multiplier. The † symbol indicates that the values shown are averages for instances where feasible solutions were found.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with varying levels of hardness (Easy, Medium, Hard). The results compare the performance of various methods, including heuristic solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy-L, Greedy-C), previous neural network-based methods (JAMPR, OSLA, MUSLA, MUSLA adapt), and the proposed methods (AM*+PIP, AM*+PIP-D, POMO*+PIP, POMO*+PIP-D) across different problem sizes (n=50, n=100). Metrics include the percentage of infeasible solutions, the solution objective value (Obj.), the optimality gap compared to LKH3, and the computation time. The table highlights the effectiveness of the proposed PIP and PIP-D frameworks in improving solution quality and feasibility, especially in more challenging instances.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on TSPTW instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods are compared, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy), prior neural methods (JAMPR, OSLA, MUSLA, AM, POMO), and the proposed PIP and PIP-D methods. The metrics evaluated are infeasible rate (both solution-level and instance-level), solution quality (objective value and optimality gap), and computation time. This table is used to demonstrate the effectiveness of PIP and PIP-D in solving TSPTW problems under different constraint hardness.

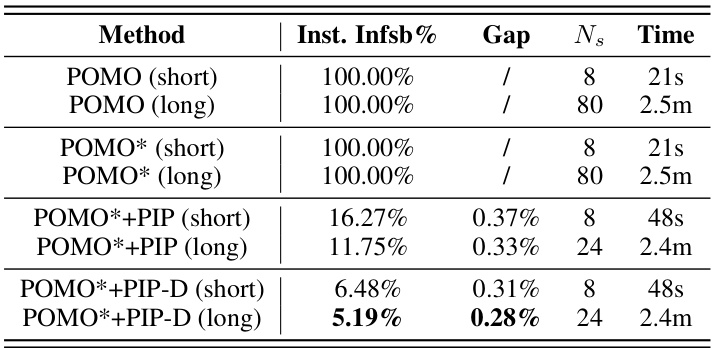

This table shows the results of experiments conducted on the Hard TSPTW-100 dataset under different inference time budgets. The results include instance-level infeasibility rate (Inst. Infsb%), optimality gap (Gap), the number of sampled solutions (Ns), and inference time. The table compares the performance of different variants of the POMO model (with and without PIP and PIP-D) under shorter (8 solutions) and longer (80 solutions) inference times. The results highlight the impact of inference time and the effectiveness of the proposed PIP and PIP-D frameworks in improving solution feasibility and optimality.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with three different hardness levels (easy, medium, hard). It compares the performance of several methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools), greedy approaches, and neural network-based methods (AM, POMO) with and without the proposed PIP and PIP-D frameworks. For each method and hardness level, the table shows the infeasible rate (percentage of solutions that violate constraints), the average solution objective value, the optimality gap (compared to LKH3), and the computation time. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the PIP and PIP-D frameworks in improving the solution quality and feasibility rate, particularly in the more challenging instances.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with three different hardness levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). Multiple methods are compared, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools, Greedy), prior neural network approaches (AM, POMO), and the proposed methods (AM*+PIP, AM*+PIP-D, POMO*+PIP, POMO*+PIP-D). The table shows the infeasible rate (at both the solution and instance level), the optimality gap compared to the optimal solution found by LKH3, the objective function value (total tour length), and the computation time. The results illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed PIP framework in improving the feasibility and solution quality of neural network-based methods for solving TSPTW problems with complex constraints.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows (TSPTW) instances with varying difficulty levels (Easy, Medium, Hard). It compares different methods, including traditional solvers (LKH3, OR-Tools), greedy heuristics, existing neural network methods (AM, POMO, others), and the proposed PIP and PIP-D methods. The metrics presented include the percentage of infeasible solutions, the objective function value (Obj.), the optimality gap (Gap), and the computation time (Time). The table helps to illustrate the performance of different approaches on TSPTW instances with various constraint hardness levels.

Full paper#