↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Online regression, crucial for handling streaming data, often struggles with optimal threshold selection in algorithms like Passive-Aggressive (PA) and adapting to scenarios with multiple performance metrics beyond accuracy. Existing methods face challenges in balancing real-time accuracy with long-term performance and effectively utilizing side information.

The proposed APAS framework innovatively addresses these issues. It leverages side information for finer weight adjustments, adaptively selects the optimal threshold, and incorporates an efficient algorithm for faster computation. Theoretical guarantees, in the form of a regret bound, ensure its robustness. Empirical results demonstrate APAS’s superior performance across various scenarios, highlighting significant improvements over traditional methods in terms of both accuracy and performance associated with side information.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents APAS, a novel adaptive framework that significantly improves online regression by integrating side information and adapting thresholds. This addresses a critical limitation of traditional methods like Passive-Aggressive algorithms, paving the way for better performance in applications involving streaming data and multiple performance metrics. The efficient algorithm and theoretical regret bound further enhance its practicality and reliability, opening new avenues for research in online learning and related fields.

Visual Insights#

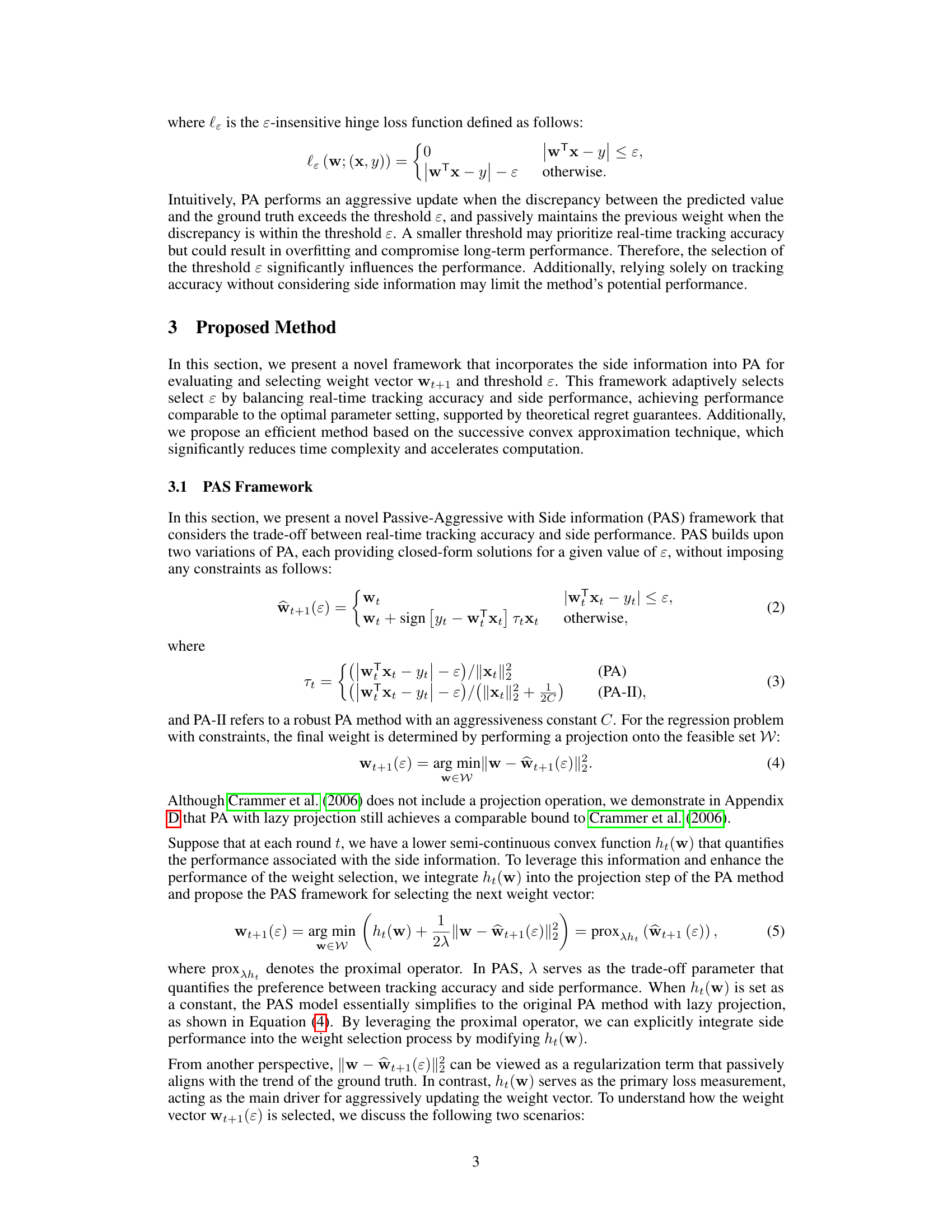

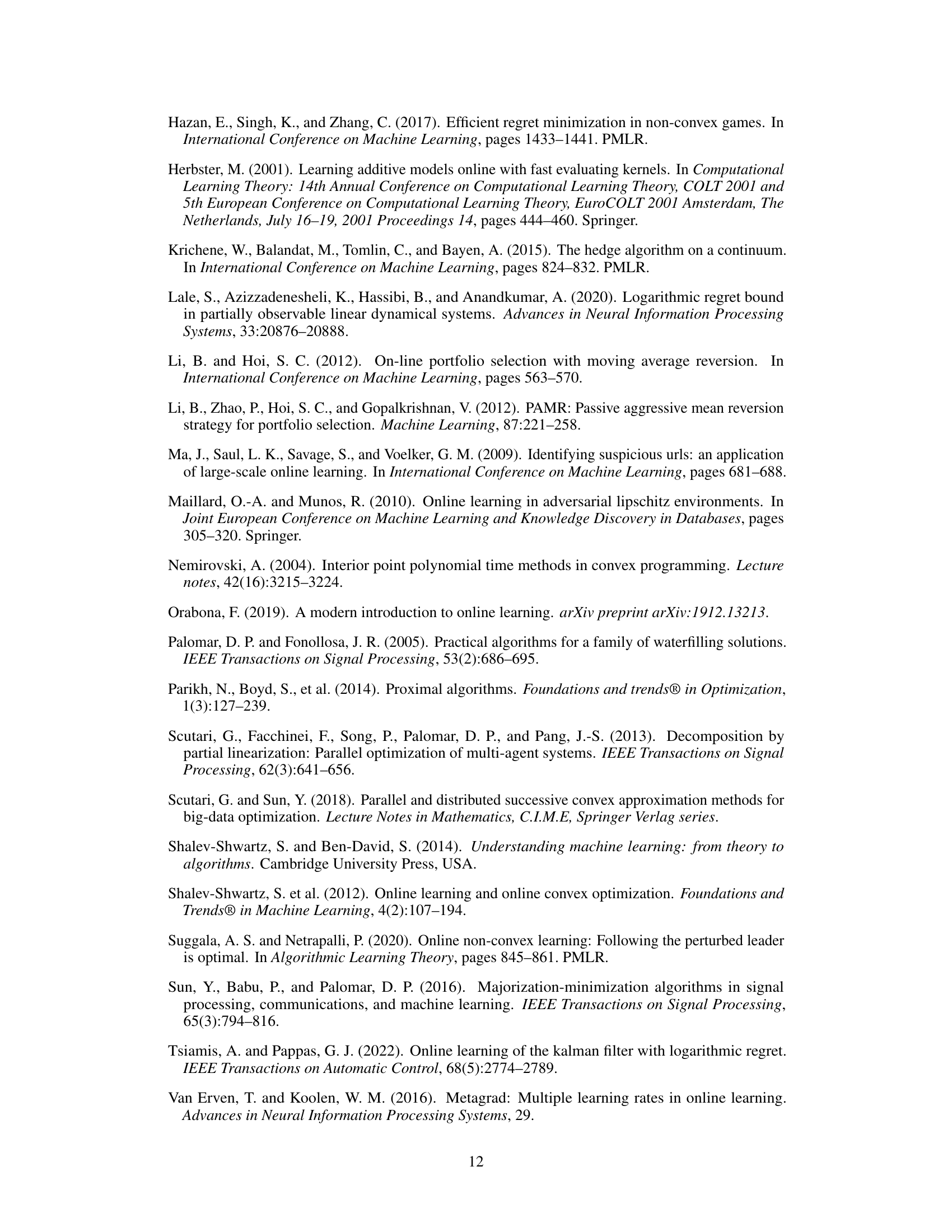

This figure illustrates the adaptive learning process of the proposed Adaptive Passive-Aggressive online regression framework with Side information (APAS). It starts with side information, ht(.), which is then used to calculate the proximal operator, proxλht(ŵt+1(ɛt)), to generate the weight vector, ŵt+1(ɛt), based on the passive-aggressive weight update. Then, Moreau Envelope, Mλht(ŵt+1(ɛt)), is used to calculate the loss function ft(ɛt), which finally determines the update of ɛt+1. This iterative process shows how APAS adapts to different scenarios by adjusting the threshold parameter dynamically, ensuring balance between real-time tracking accuracy and side performance.

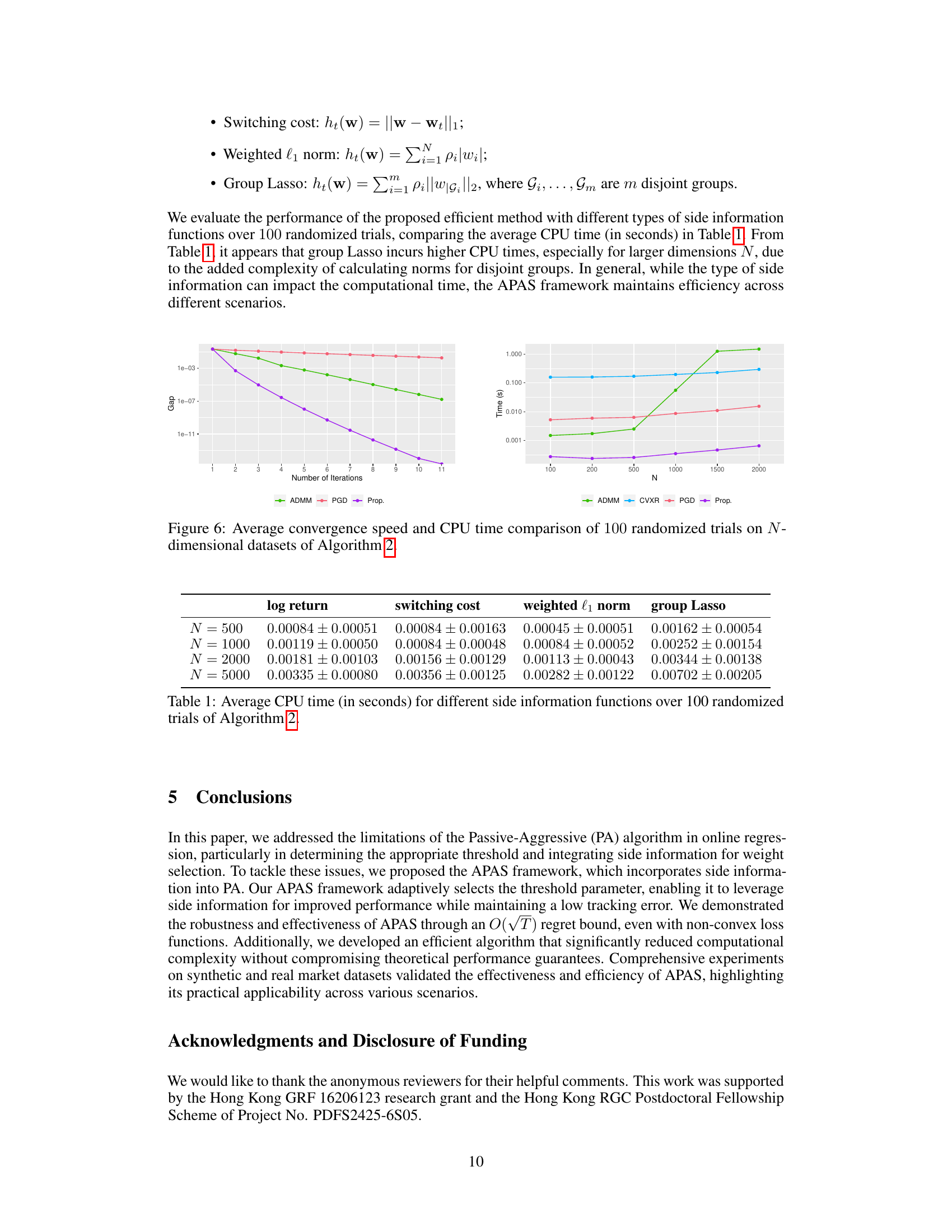

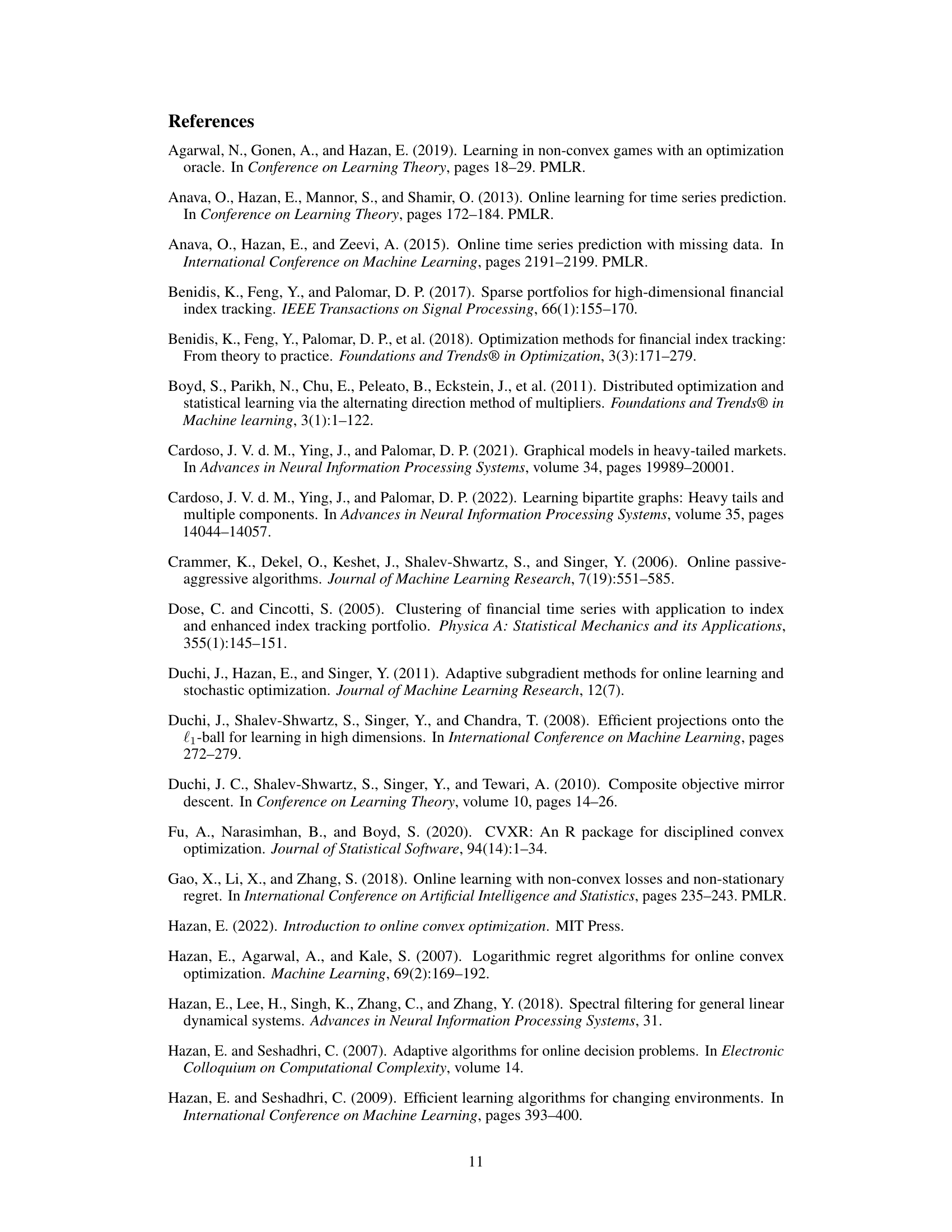

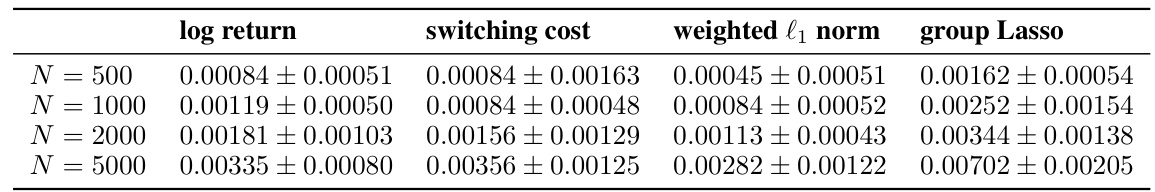

This table shows the average CPU time in seconds taken by Algorithm 2 for different side information functions across 100 randomized trials. The different functions compared are log return, switching cost, weighted l1 norm, and group lasso. The table shows results for different problem dimensions (N = 500, 1000, 2000, 5000). The results demonstrate the computational efficiency of Algorithm 2, which leverages the successive convex approximation technique to accelerate computation.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive PA#

The concept of “Adaptive PA”, likely referring to an adaptive passive-aggressive algorithm, presents a significant advancement in online learning. Standard passive-aggressive methods suffer from the challenge of selecting an optimal threshold for parameter updates. Adaptive PA addresses this limitation by dynamically adjusting the threshold based on factors such as observed error and side information. This dynamic adjustment allows the algorithm to be more responsive to changing data patterns and incorporate additional contextual information for more nuanced decision-making. The benefits include improved accuracy, robustness, and the ability to optimize for multiple competing objectives (e.g. real-time tracking and long-term accuracy). A key aspect is the use of side information, which allows the algorithm to leverage additional data beyond the primary training data to inform the threshold adaptation. This strategy enhances learning and enables more efficient and accurate weight selection, thereby improving overall performance. The theoretical analysis of the algorithm likely involves regret bounds, demonstrating that performance remains competitive with optimal static strategies. Efficient implementation using techniques like successive convex approximation (SCA) reduces computational complexity further enhancing practical applicability.

Side Info Use#

The utilization of side information is a crucial aspect of the presented adaptive passive-aggressive framework. The framework leverages additional information, beyond just tracking accuracy, to make more informed decisions during weight updates in the online regression process. This allows for a finer level of control over the model’s behavior, and potentially leads to improved performance in scenarios where solely focusing on minimization of tracking error is insufficient. Adaptive selection of the threshold parameter based on side information is a key feature, enhancing the model’s ability to generalize and perform well across different settings. However, the specific nature of the side information used and how it’s integrated might impact performance, highlighting the importance of careful selection and design. The theoretical convergence and empirical validation of this approach show its effectiveness in balancing tracking error with the valuable insights gleaned from the supplemental data. Future work might explore other kinds of side information, and the potential for more complex relationships between the side information and the model’s primary objective.

Regret Bound#

The concept of a ‘Regret Bound’ in online learning is crucial for evaluating the performance of algorithms that learn sequentially from data streams. A regret bound provides a theoretical guarantee on the cumulative difference between the algorithm’s performance and that of the optimal, fixed strategy in hindsight. In the context of the described paper, the derivation of a regret bound for their novel Adaptive Passive-Aggressive framework with side information (APAS) is a significant theoretical contribution. The O(√T) regret bound achieved is optimal for non-convex loss functions, which is a challenging setting. This result theoretically validates the robustness and effectiveness of the APAS method and demonstrates its ability to perform well even when faced with complex scenarios and non-convex loss landscapes. The derivation likely involves sophisticated mathematical analysis, leveraging techniques from online convex optimization theory and potentially incorporating properties of the specific loss function used. Obtaining an optimal regret bound in a non-convex setting is particularly noteworthy; it contrasts the challenges usually encountered with non-convexity, thereby highlighting the strength of the APAS theoretical foundations.

Efficient Algo#

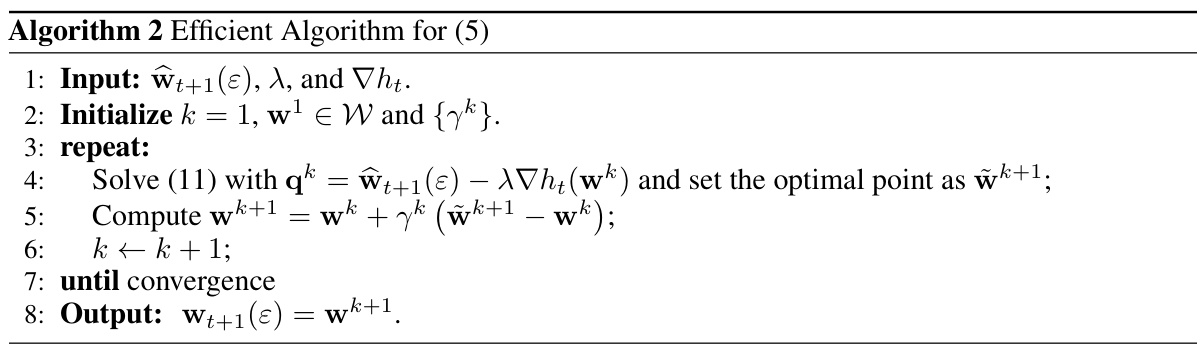

The heading ‘Efficient Algo’ likely refers to a section detailing the computational efficiency of the proposed method. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the specific algorithms employed, comparing their time and space complexities to existing methods. The core of the discussion should focus on how the algorithm’s design contributes to its efficiency. This might involve discussing techniques like successive convex approximation (SCA), used to accelerate computations by iteratively optimizing a simpler surrogate function. A comparison against other relevant algorithms (e.g., interior point methods) would provide a clearer picture of the proposed method’s computational advantage. The analysis should also address the scalability of the algorithm, highlighting its ability to handle large-scale datasets. Finally, empirical results supporting the claims of efficiency should be presented, likely including runtime and memory usage data across different problem sizes, demonstrating a significant speedup compared to baseline methods. The discussion would need to consider how specific choices in algorithmic design impact the runtime and memory requirements, providing a comprehensive understanding of the method’s efficiency.

Real Data Test#

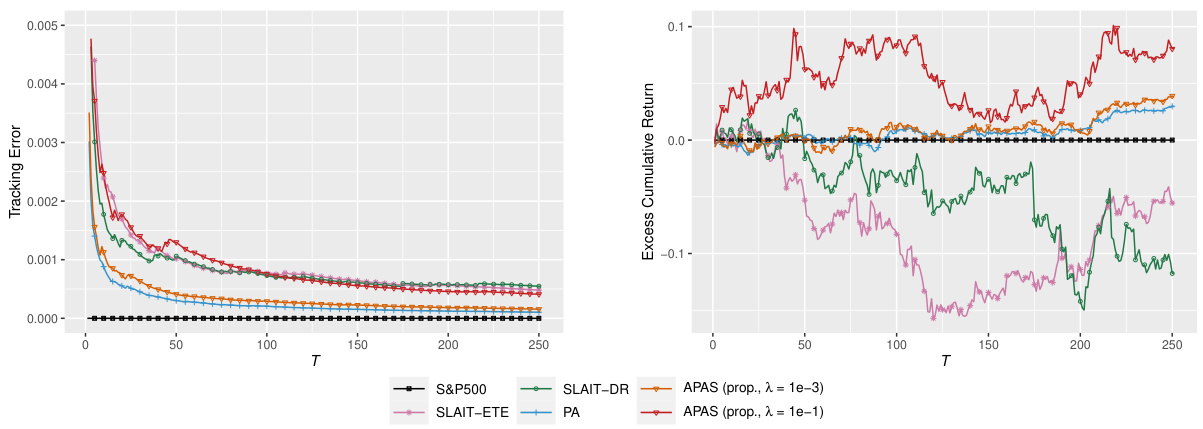

A robust ‘Real Data Test’ section in a research paper would go beyond simply applying the proposed method to real-world datasets. It should demonstrate the model’s performance against established baselines, quantifying improvements with appropriate metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC, depending on the task. A strong test would also include an analysis of the model’s behavior under different conditions or subsets of the data, showing its robustness and generalizability. For example, comparing performance on various time periods or market conditions would provide insights into its reliability. Crucially, the section should acknowledge limitations and potential weaknesses exposed by real-world data, and offer insights into areas for future work based on the testing results. The use of visualization tools such as graphs and charts to present the findings effectively is also crucial for a convincing ‘Real Data Test’.

More visual insights#

More on figures

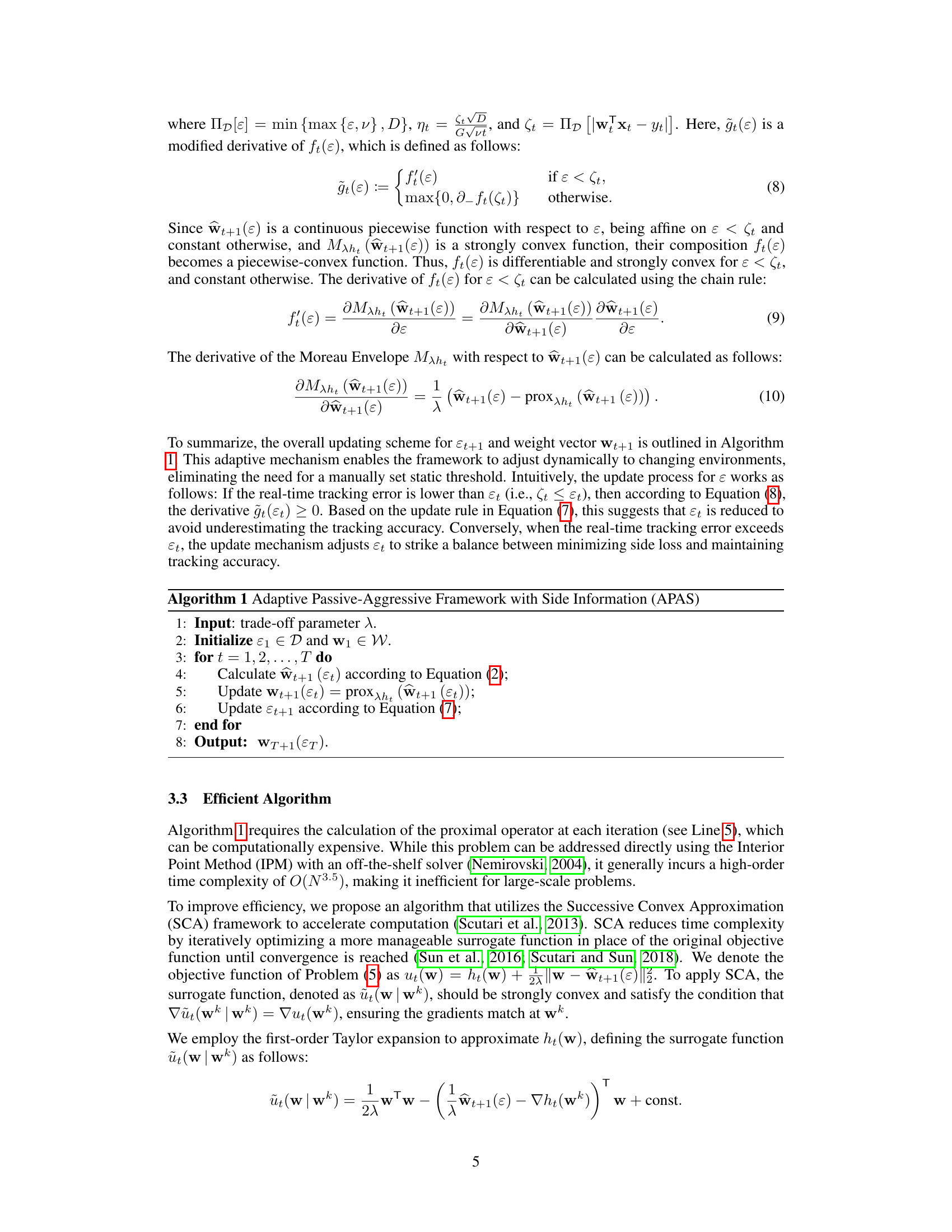

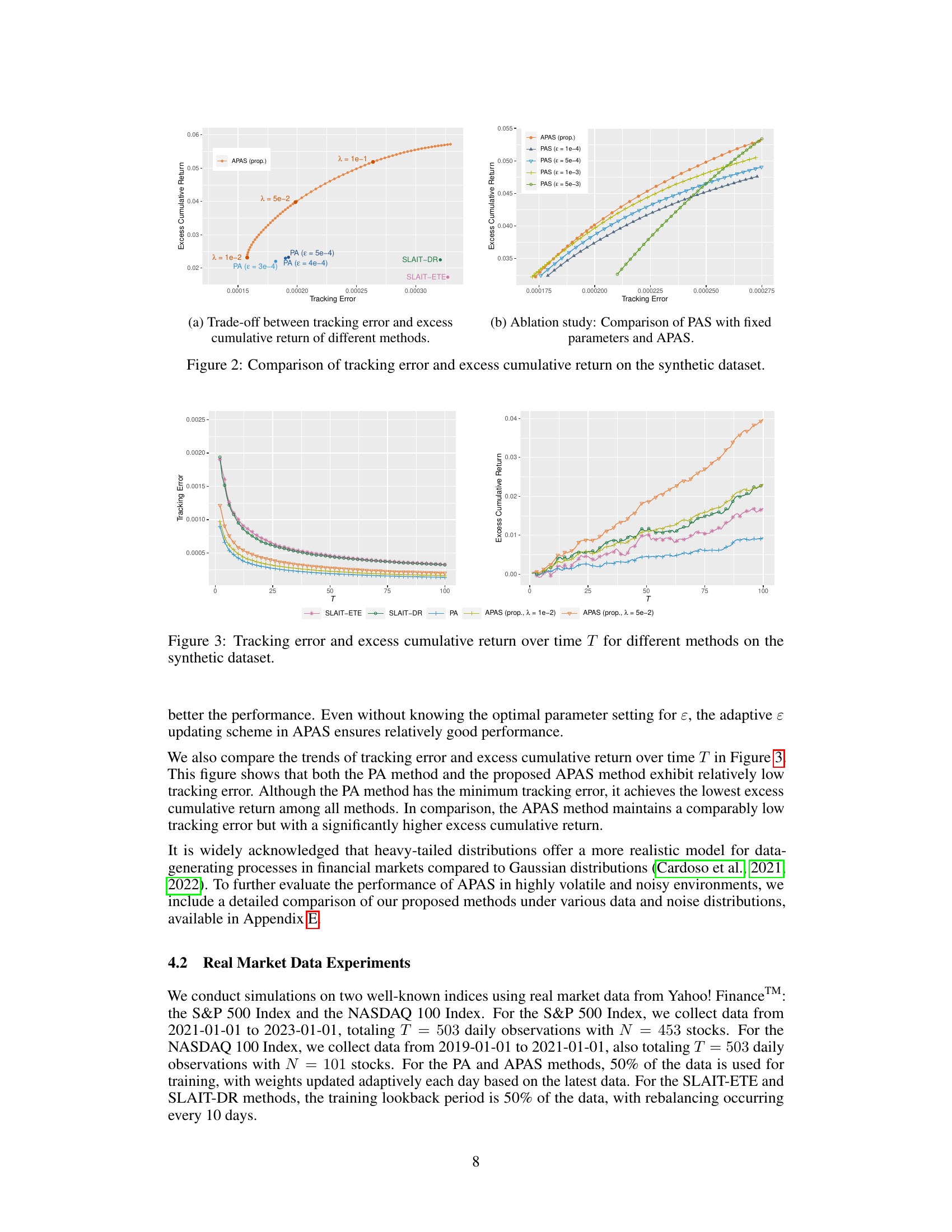

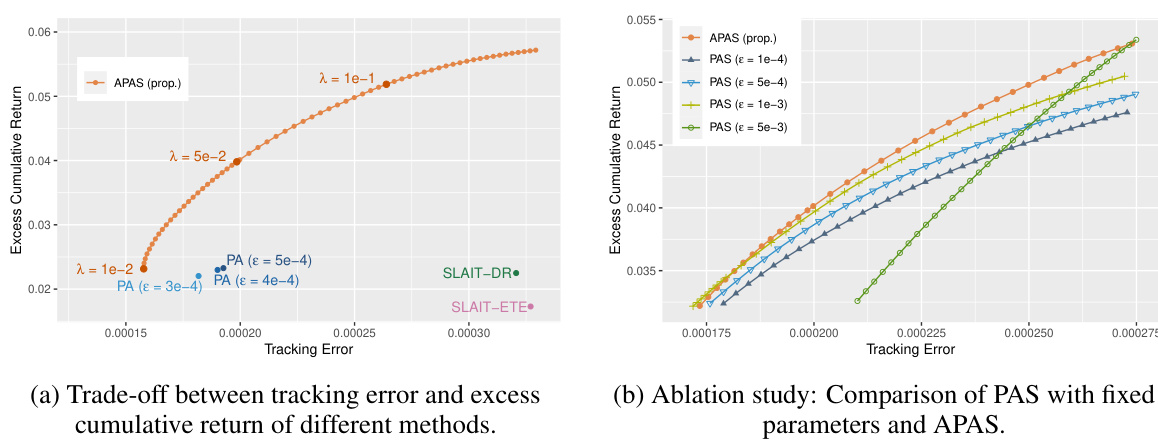

This figure shows the performance comparison of the proposed APAS framework against several benchmark methods on a synthetic dataset. Subfigure (a) presents a trade-off curve between tracking error and excess cumulative return for APAS (with different lambda values) and the benchmarks. It demonstrates that APAS achieves higher excess cumulative returns for a given level of tracking error compared to the benchmarks. Subfigure (b) provides an ablation study comparing the adaptive APAS with a non-adaptive PAS (Passive-Aggressive with Side information) that uses fixed epsilon values. This highlights the benefit of APAS’s adaptive epsilon selection in balancing tracking accuracy and side performance.

This figure compares the tracking error and excess cumulative return of different methods on a synthetic dataset. Panel (a) shows a trade-off curve between tracking error and excess cumulative return for the proposed APAS method (with different lambda values) and other benchmark methods. Panel (b) shows an ablation study comparing APAS (adaptive threshold) with a non-adaptive version of PAS (fixed threshold) demonstrating improved performance of APAS.

This figure shows the performance comparison of different methods on a synthetic dataset. The left subplot displays the trade-off between tracking error and excess cumulative return. The adaptive APAS method achieves higher excess cumulative return for the same level of tracking error and lower tracking error for the same level of excess cumulative return, compared to the benchmarks (PA, SLAIT-ETE, and SLAIT-DR). The right subplot shows an ablation study comparing the adaptive APAS with different fixed threshold parameter settings (PAS). It highlights how the adaptive parameter selection in APAS leads to superior performance compared to manually setting the threshold parameter in PAS.

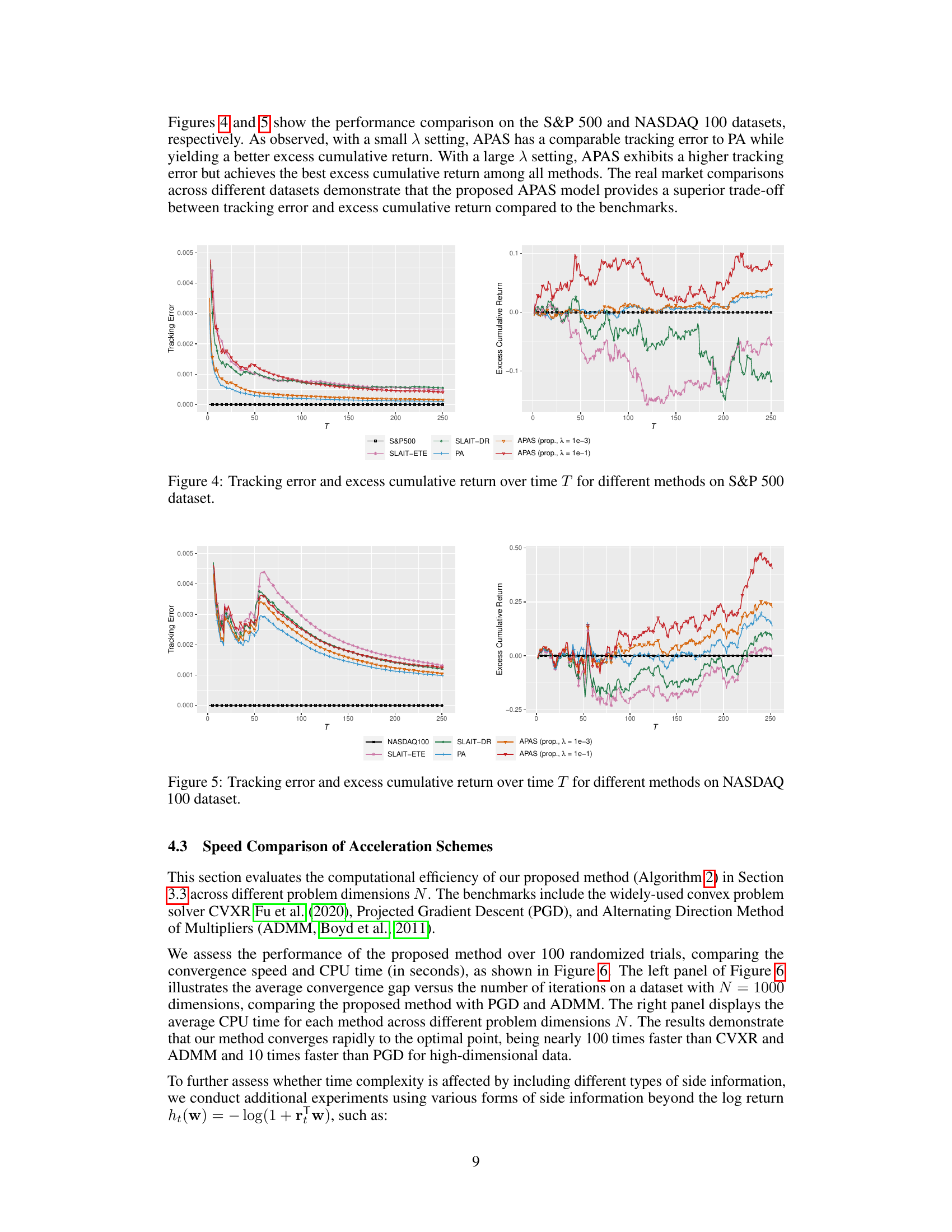

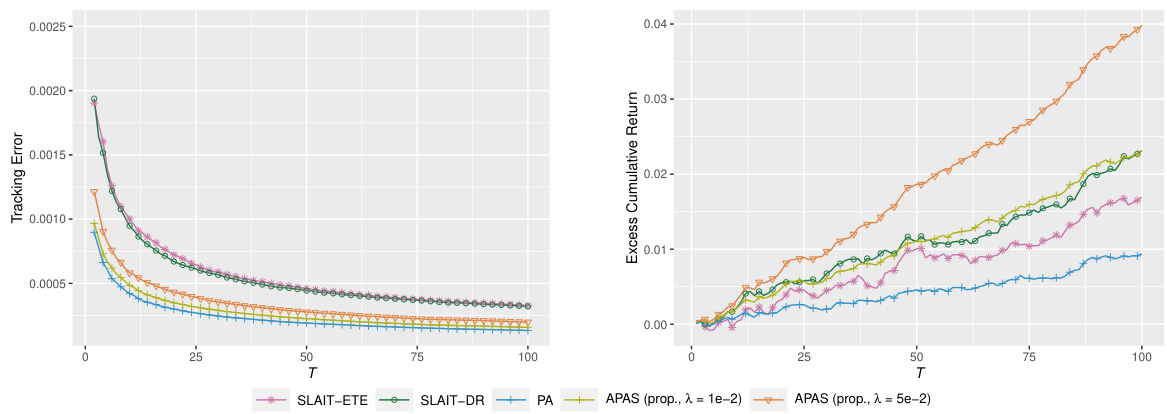

This figure compares the performance of different online regression methods (APAS with different lambda values, SLAIT-ETE, SLAIT-DR, and PA) on the NASDAQ 100 dataset in terms of tracking error and excess cumulative return over time. The x-axis represents the time step (T), while the y-axis shows the tracking error (left panel) and excess cumulative return (right panel). The results illustrate the trade-off between tracking accuracy and excess return achieved by different methods and parameter settings. APAS demonstrates a better balance between these two metrics, especially when a larger lambda value is used, indicating its effectiveness in achieving high excess returns without significantly sacrificing tracking accuracy.

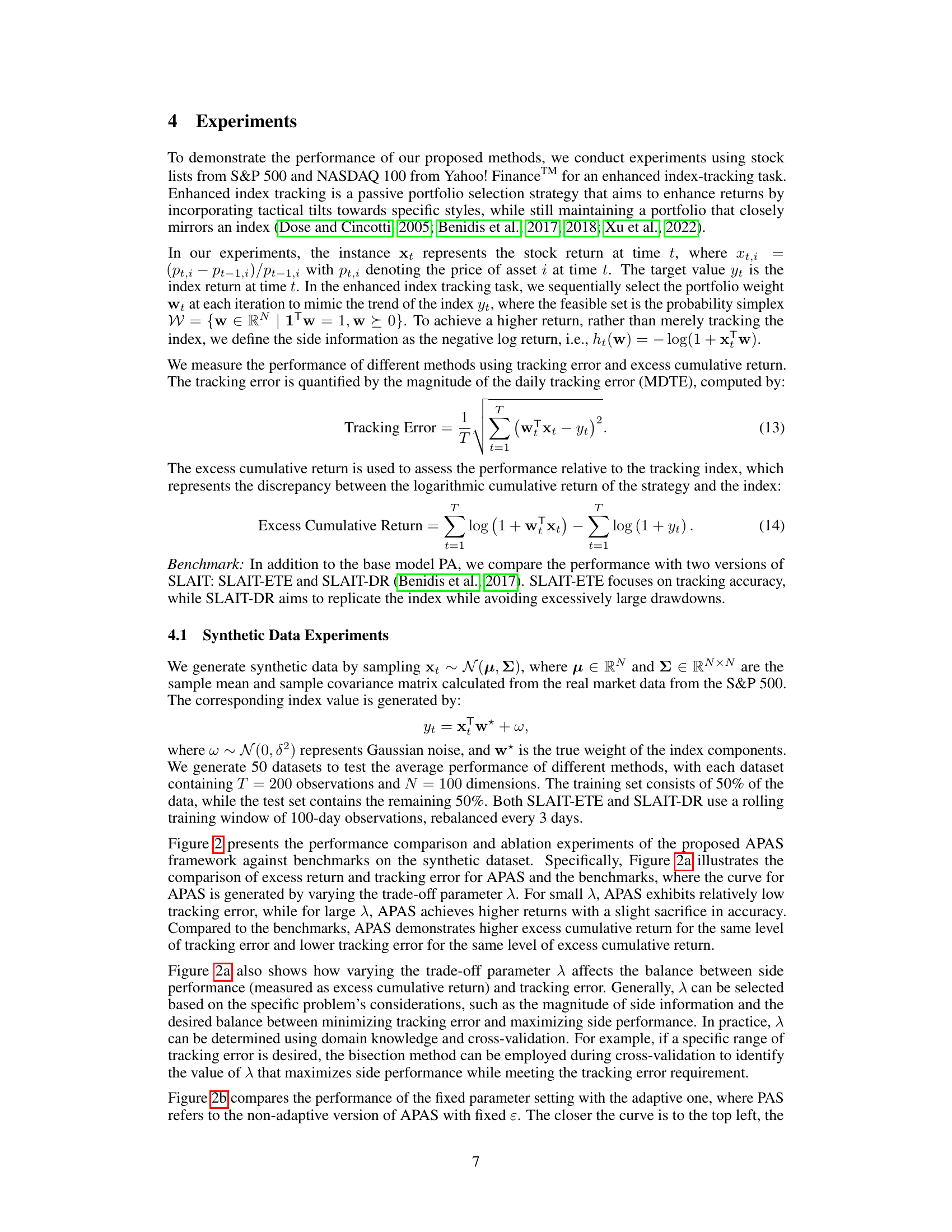

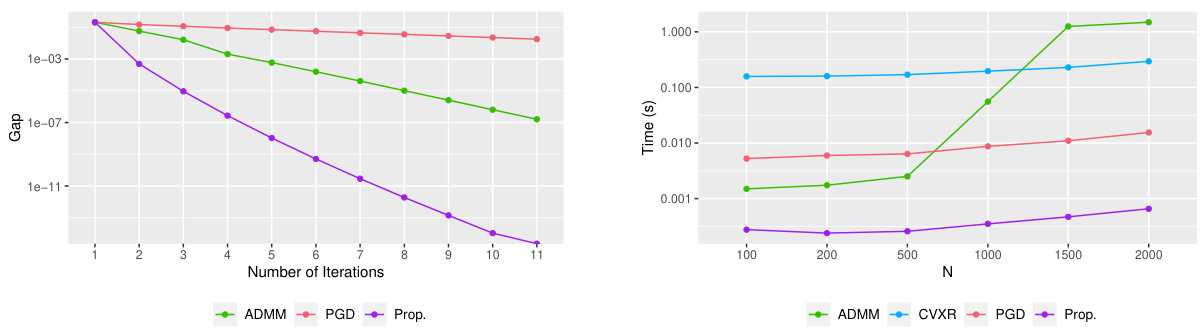

This figure compares the performance of four different algorithms (ADMM, CVXR, PGD, and the proposed algorithm) in terms of convergence speed and CPU time. The left panel shows the average convergence gap versus the number of iterations for a dataset with N = 1000 dimensions. The right panel illustrates the average CPU time for each method across various problem dimensions (N). The proposed algorithm demonstrates significantly faster convergence and lower CPU time compared to the other algorithms, especially for high-dimensional data.

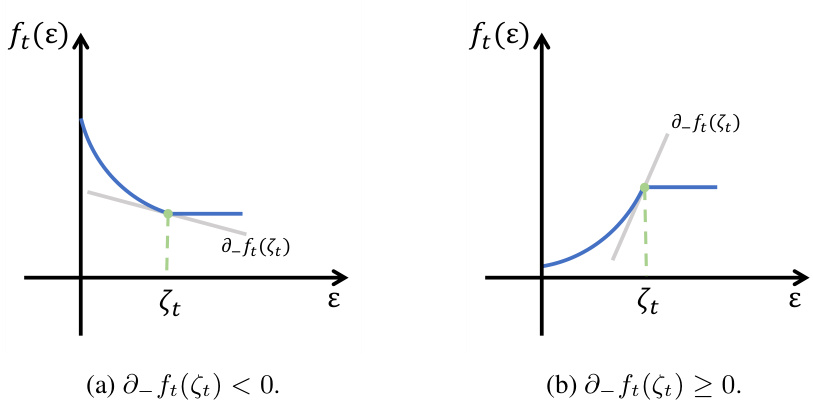

This figure illustrates two scenarios for the curves of the loss function ft(ε) when ν < ζt < D. The left panel (a) shows the case where the left derivative of ft(ε) at ζt is negative (∂_ft(ζt) < 0), resulting in a convex function. The right panel (b) shows the case where the left derivative of ft(ε) at ζt is non-negative (∂_ft(ζt) ≥ 0), resulting in a quasi-convex function. These scenarios are analyzed to verify the inequalities used in the proof of Proposition 3, which establishes a bound used in the regret analysis of the APAS algorithm.

More on tables

This table presents the average CPU time in seconds taken by Algorithm 2 for different side information functions over 100 randomized trials. The functions compared include ’log return’, ‘switching cost’, ‘weighted l1 norm’, and ‘group Lasso’. The results are shown for different problem dimensions (N = 500, 1000, 2000, 5000), demonstrating the effect of problem size on computation time for each function. The values are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

This table shows the average CPU time in seconds for Algorithm 2, which is an efficient algorithm for solving the weight selection problem in the APAS framework. The algorithm’s efficiency is evaluated using four different types of side information functions: log return, switching cost, weighted l1 norm, and group lasso. The experiment is run 100 times for four different problem dimensions (N = 500, 1000, 2000, and 5000), and the average CPU time and standard deviation are reported for each condition. This table demonstrates that the computational efficiency of the APAS algorithm is only slightly affected by the choice of side information function. Although group lasso shows increased computation time with increasing dimensionality N, the overall efficiency of the proposed method is demonstrated.

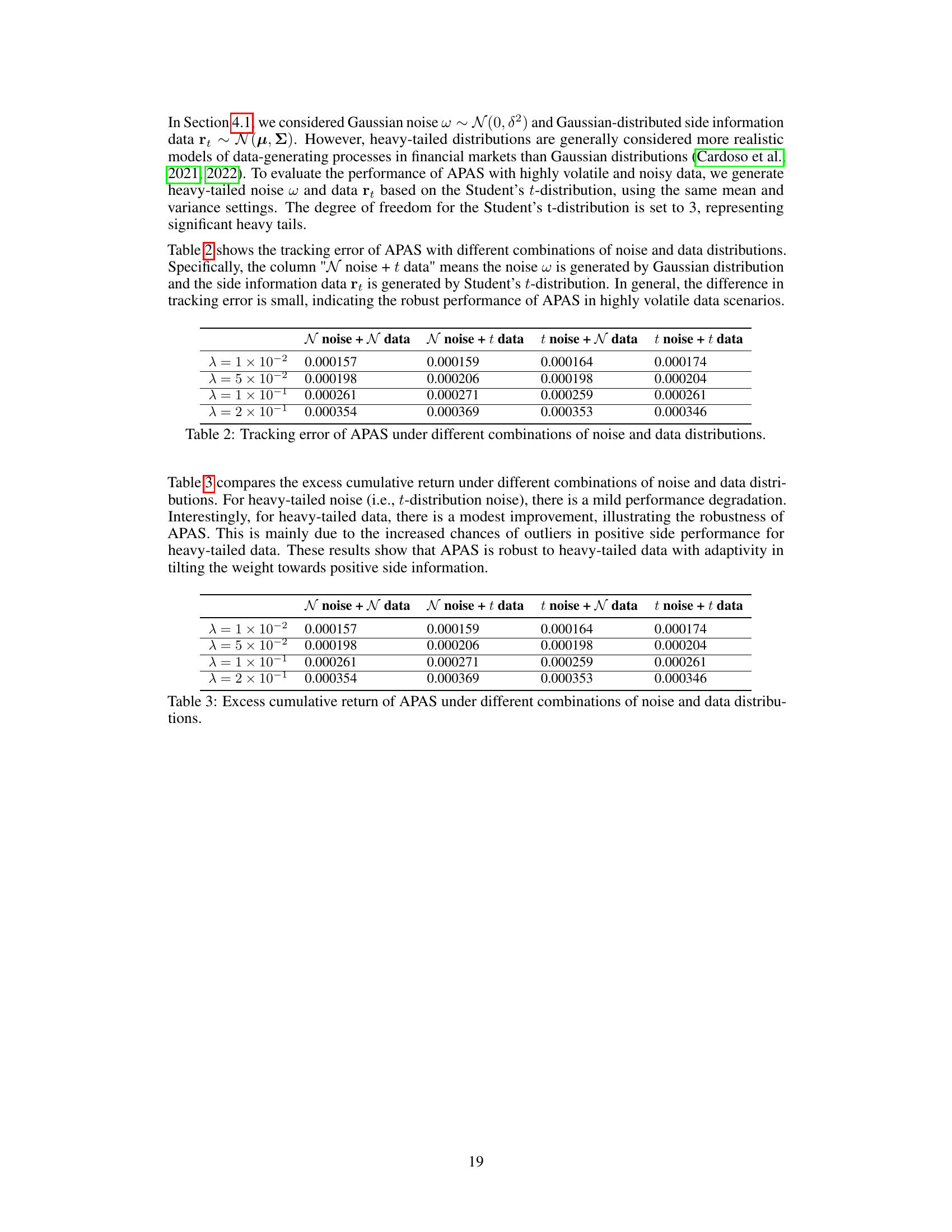

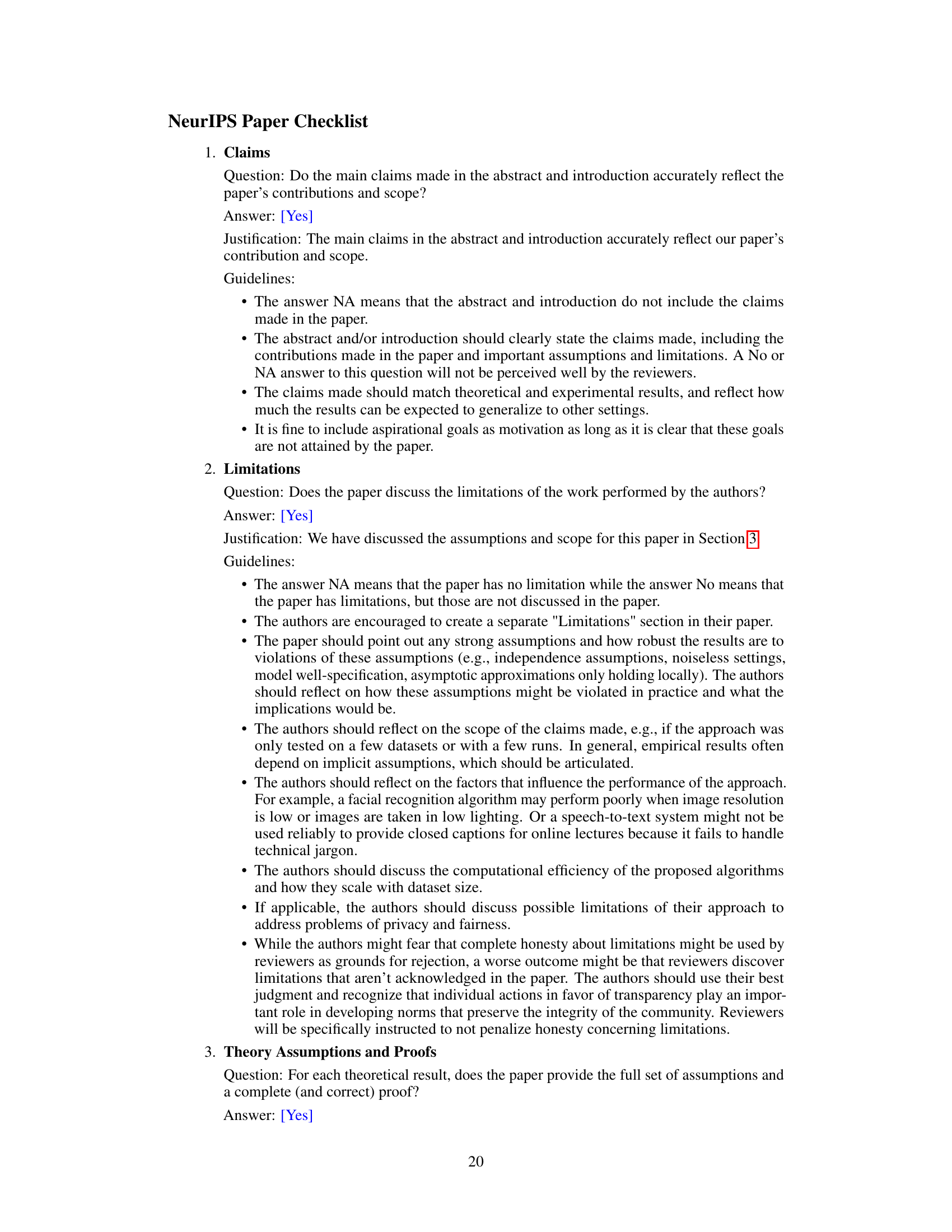

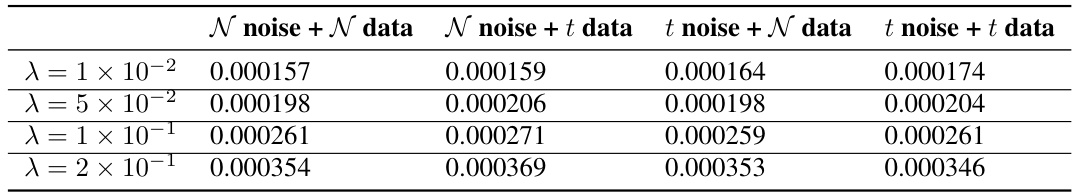

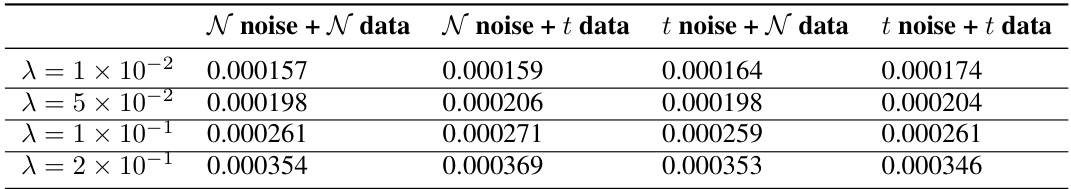

This table presents the tracking error results obtained from the Adaptive Passive-Aggressive online regression framework with Side information (APAS) model under various noise and data distribution conditions. The experiment compared four scenarios: both noise and data following a normal distribution, noise following a normal distribution and data following a Student’s t-distribution, noise following a Student’s t-distribution and data following a normal distribution, and both noise and data following a Student’s t-distribution. The results are shown for different values of lambda (λ), a trade-off parameter in the APAS model.

This table presents the tracking error results obtained from the APAS model under various combinations of noise and data distributions. Specifically, it shows how the tracking error changes when either the noise or the data (or both) are drawn from a heavy-tailed Student’s t-distribution, as compared to using only Gaussian distributions. Different values of the trade-off parameter (λ) are also included, showing its impact on the tracking error under different distribution scenarios.

Full paper#