↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current face recognition models struggle with overfitting and the negative impact of hard-to-classify samples on model generalization. This often leads to poor performance on unseen data. Topological data analysis offers a potential solution by encoding the underlying structure of the data to improve generalization.

TopoFR leverages persistent homology to align the topological structures of the input and latent spaces. This unique approach ensures that the crucial structural information of the input data is preserved in the model’s learned representation. In addition, a new hard sample mining strategy focuses the model’s learning on the most challenging samples, further enhancing its ability to generalize. The results show TopoFR outperforms current state-of-the-art methods on multiple benchmark datasets, showcasing its effectiveness and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of current face recognition models by leveraging topological structure information. It introduces novel methods for topological structure alignment and hard sample mining, improving model generalization and performance. This work opens new avenues for research in unsupervised learning and topological data analysis within the context of face recognition. It also achieved a top-tier ranking in a major face recognition challenge.

Visual Insights#

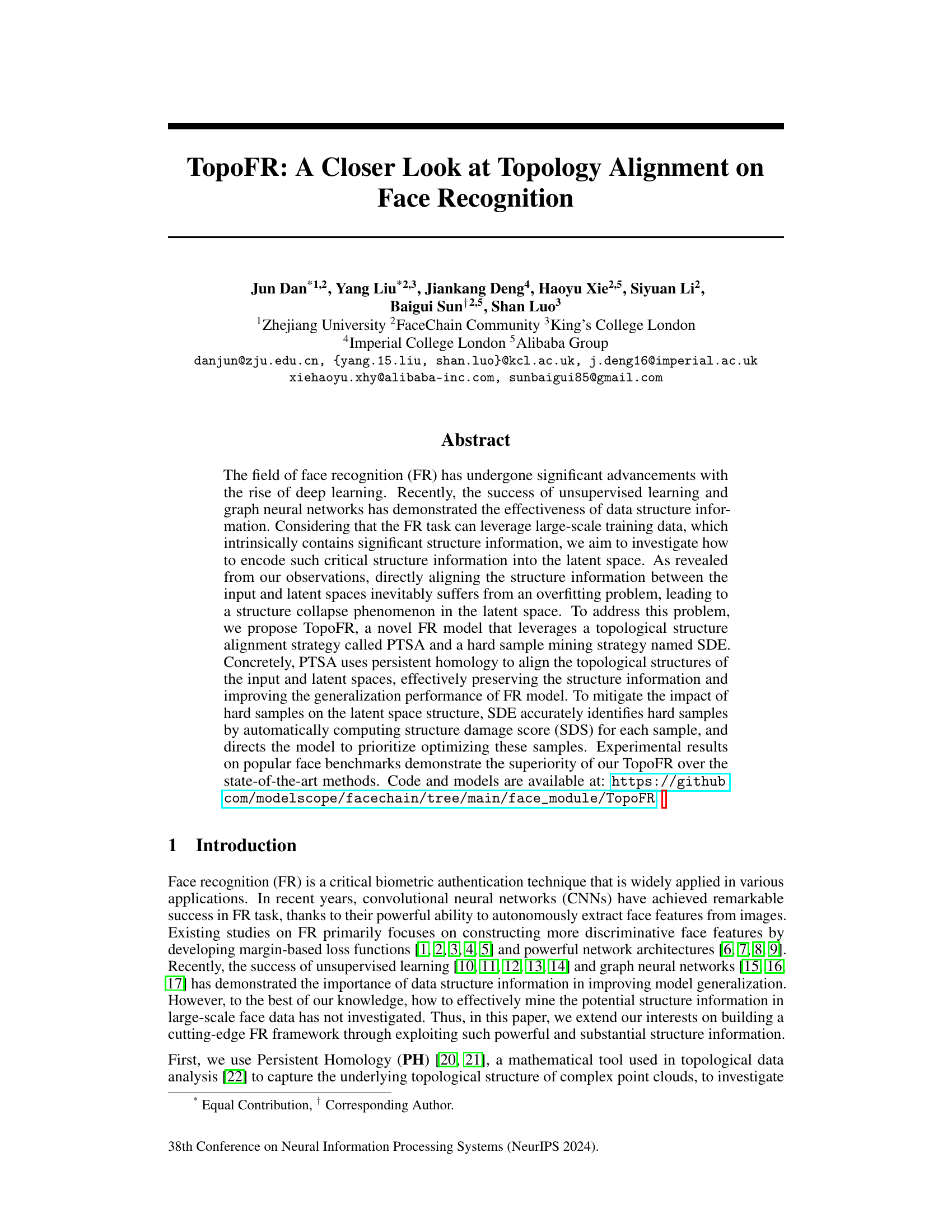

This figure shows persistence diagrams of face images sampled from the MS1MV2 dataset with different sizes (1000, 5000, 10000, and 100000 images). The diagrams illustrate the topological structure of the data, showing an increase in the number of higher-dimensional holes (represented by Hj) as the dataset size grows. This visually demonstrates that larger datasets have more complex underlying topological structures.

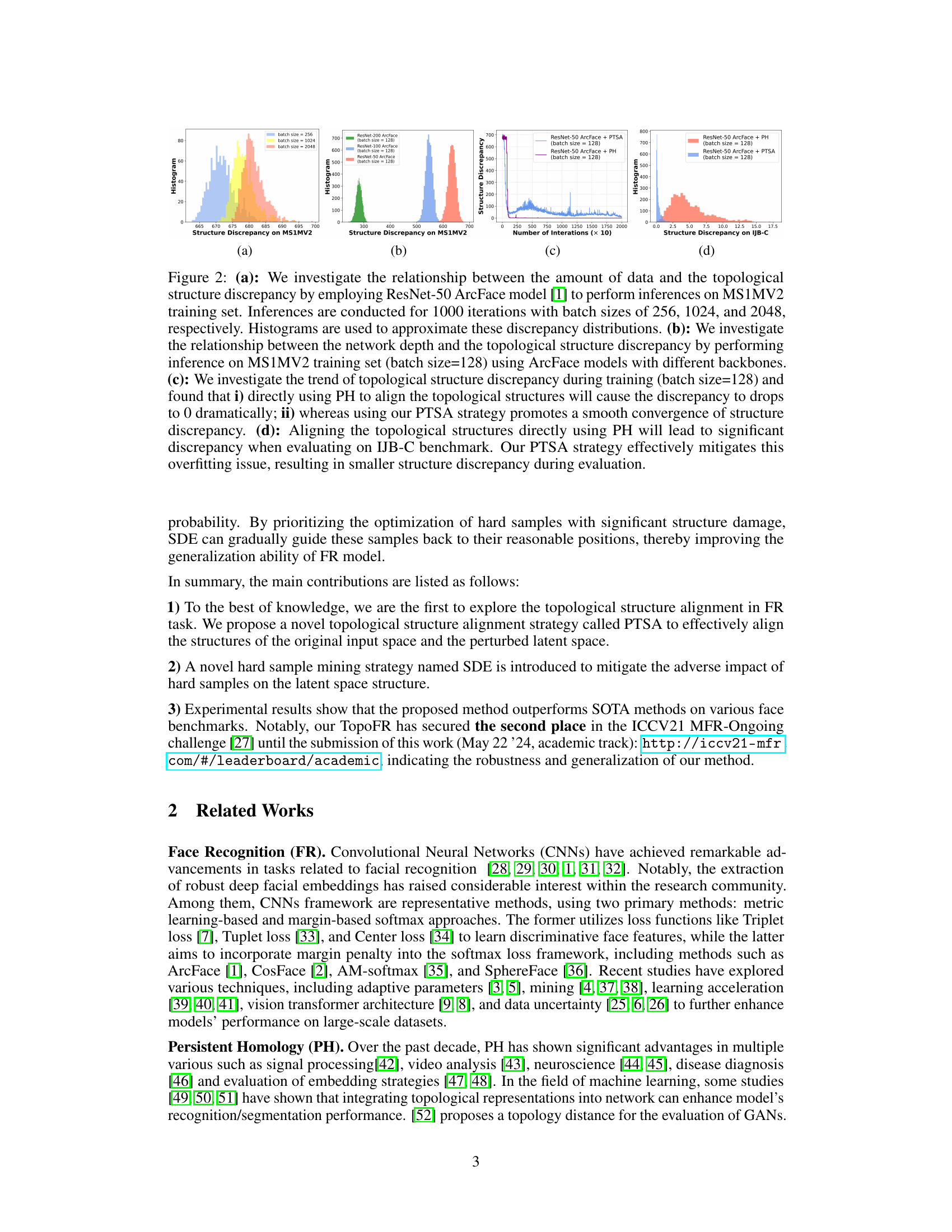

This table presents the verification accuracy results of different face recognition models on the challenging Masked Face Recognition (MFR) ongoing benchmark. The benchmark includes various subsets focusing on different aspects of face recognition such as masked faces, children’s faces, and faces from different ethnic backgrounds. The table compares the performance of the proposed TopoFR model against state-of-the-art methods on different sub-challenges within the MFR benchmark, showing its superior accuracy compared to other models.

In-depth insights#

Topological FR#

The concept of “Topological FR” (Face Recognition) introduces a novel approach that leverages topological data analysis to improve the robustness and generalizability of face recognition models. This method focuses on encoding the intrinsic structure of face data into the latent space of a model. Instead of relying solely on feature extraction, Topological FR incorporates information about the global arrangement and relationships between facial features, capturing a more holistic representation of faces. This is achieved by aligning the topological structures of the input and latent spaces, preserving crucial structural information even during model training. The approach addresses issues like overfitting and structure collapse observed in traditional methods. By prioritizing the optimization of hard samples (samples that are difficult for the model to classify correctly), this technique enhances the generalization ability and results in better performance on benchmark datasets. Topological FR offers a new paradigm in face recognition, moving beyond simple feature comparison to a more sophisticated understanding of face data structure. However, limitations exist, including the computational cost of topological analysis and the potential impact of noise or low-quality data on topological structure calculation.

PTSA Strategy#

The Perturbation-guided Topological Structure Alignment (PTSA) strategy is a crucial innovation in TopoFR, addressing the limitations of directly aligning topological structures in face recognition. PTSA cleverly uses persistent homology to compare the topological structures of the input and latent spaces. This comparison is not made directly but rather on a perturbed latent space. The perturbation is crucial as it prevents overfitting and structure collapse, a common problem when directly aligning complex structures. The use of a random structure perturbation (RSP) mechanism before the alignment step is key to injecting variability into the latent space and enabling the alignment to generalize better, preventing the collapse observed in prior approaches which attempted similar direct alignment methods. The invariant structure alignment (ISA) component of PTSA is computationally efficient, directly comparing topological features using a fast method that is robust to outliers. This method contrasts with the computationally expensive bottleneck distance or Wasserstein distance methods typically used in this domain. The combination of perturbation and the efficient comparison method makes PTSA a highly effective and practical strategy for structure preservation in face recognition.

SDE Method#

The Structure Damage Estimation (SDE) method, as described in the context, is a novel hard sample mining strategy designed to improve the robustness and generalization of face recognition models. SDE addresses the detrimental effect of low-quality or ‘hard’ samples which tend to cluster near decision boundaries in the latent feature space, disrupting the topological structure. It accomplishes this by assigning a Structure Damage Score (SDS) to each sample, based on both prediction uncertainty and accuracy. Samples with high prediction uncertainty (near the decision boundary) and low prediction accuracy are deemed more damaging and receive a higher SDS. The model then prioritizes the optimization of these high-SDS samples, effectively guiding them towards their correct positions and improving overall latent space organization. This targeted approach is crucial as directly aligning input and latent space structure can lead to overfitting and structure collapse. Therefore, SDE enhances generalization by mitigating the negative impact of hard samples on the topological structure of the latent space, complementing the overall topological structure alignment strategy.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a face recognition model, this might involve removing or disabling elements like the topological structure alignment strategy (PTSA) or the hard sample mining strategy (SDE). By observing the impact on metrics such as accuracy and generalization performance after each removal, researchers can determine the effectiveness of each component. A well-designed ablation study should clearly show the relative importance of each module, offering valuable insights into the model’s architecture and the efficacy of its core components. For instance, a significant drop in accuracy after removing PTSA might highlight the critical role of topological information in improving recognition performance. Conversely, if removing SDE has minimal effect, it suggests that the chosen hard sample mining strategy may be less crucial for the model’s success. Furthermore, an ablation study allows comparison of different variants of a method, e.g., using different distance metrics or topological structure alignment techniques. This facilitates a comprehensive understanding of a model’s strengths and weaknesses, helping to refine its design and ultimately achieve better performance.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this topological face recognition work could involve exploring more sophisticated topological methods beyond persistent homology, such as persistent cohomology or fiberwise topology, to capture richer structural information. Investigating the impact of different distance metrics and their effect on topological alignment accuracy is crucial. Furthermore, extending TopoFR to other biometric recognition tasks, like fingerprint or iris recognition, would be valuable to ascertain the generalizability of the topological approach. A deeper analysis of hard sample identification using alternative methods, possibly incorporating uncertainty estimation beyond prediction entropy, is warranted to improve model robustness and accuracy. Finally, combining topological methods with other structure-aware techniques, such as graph neural networks, could lead to novel architectures with enhanced performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

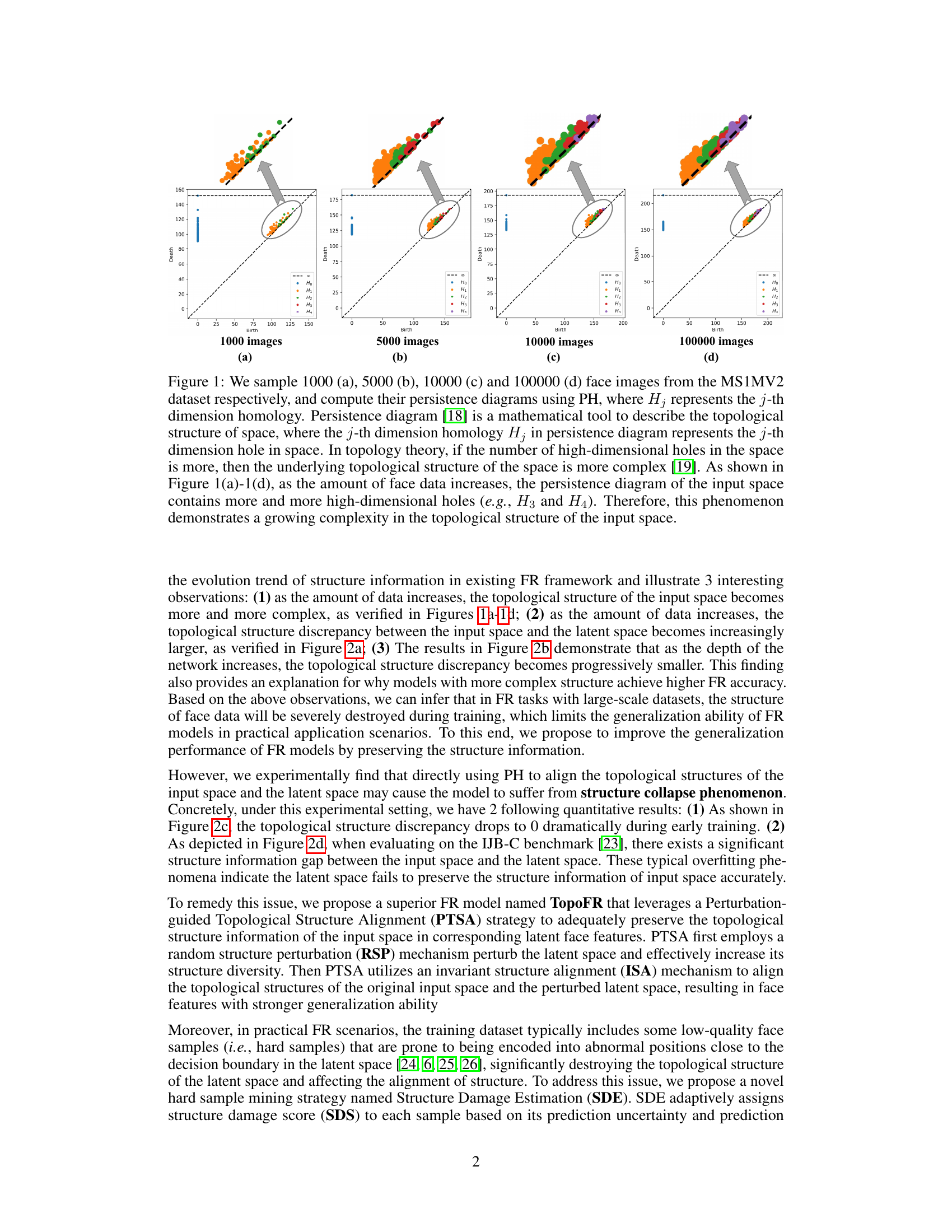

This figure investigates the relationship between data amount, network depth, and training iterations with topological structure discrepancy in face recognition. It uses ResNet-50 ArcFace model and MS1MV2 training set for experiments. The results show that directly aligning topological structures without PTSA can lead to overfitting, while PTSA mitigates this problem.

This figure shows the overall architecture of the TopoFR model. It consists of a feature extractor (F) that takes a mini-batch of face images as input. These images are preprocessed using various augmentation techniques such as Gaussian Blur, Grayscale, Random Erasing, and ColorJitter, collectively referred to as Random Structure Perturbation (RSP). The feature extractor generates latent features. These features are then passed through a classifier (C) to produce a prediction probability. The prediction probability is used to calculate the prediction entropy. Both the prediction entropy and prediction probability are used in a structure damage estimation (SDE) process. This SDE process uses a Gaussian Uniform Mixture (GUM) model to calculate a structure damage score (SDS), which is a weighting factor for the focal loss (Lcls). Additionally, the topological structures of the input and latent spaces are aligned using a strategy called Invariant Structure Alignment, resulting in a topological structure alignment loss (Lsa). The final loss function of the model is a combination of Lcls and Lsa.

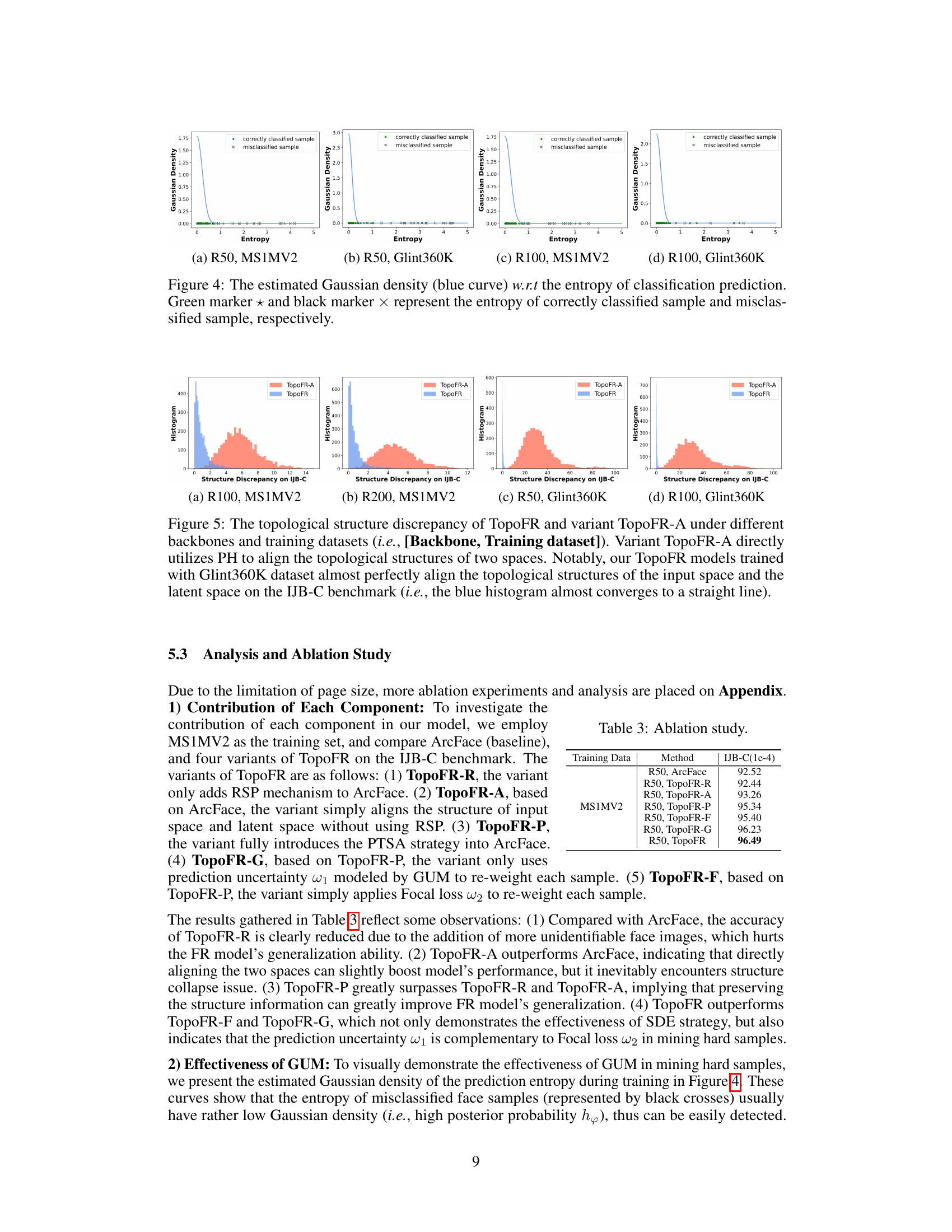

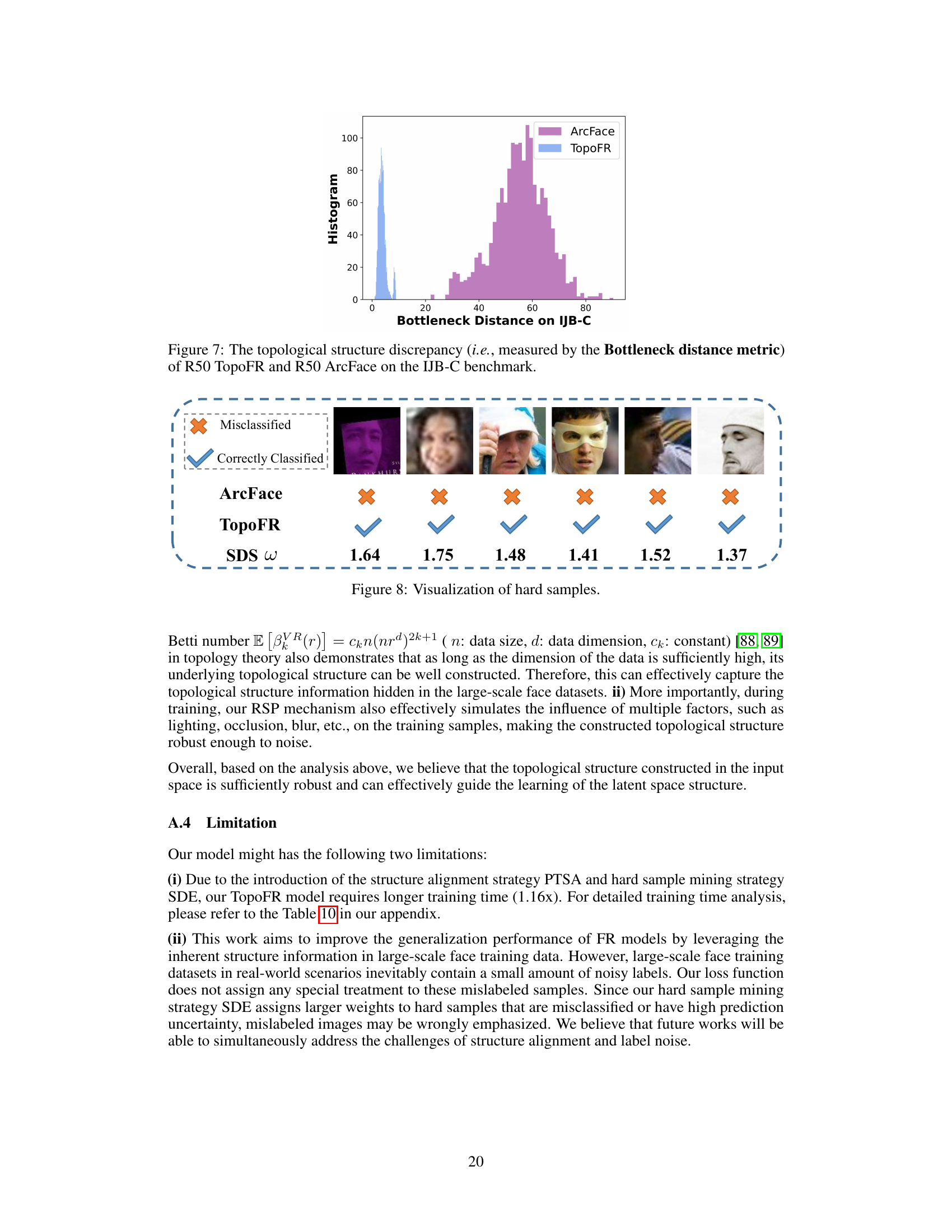

This figure visualizes the Gaussian density distribution of prediction entropy for both correctly and incorrectly classified samples. The x-axis represents the entropy of the classification prediction probability, and the y-axis represents the Gaussian density. The green markers (*) indicate correctly classified samples, and the black markers (×) indicate misclassified samples. The figure shows that misclassified samples tend to have lower Gaussian density and higher entropy.

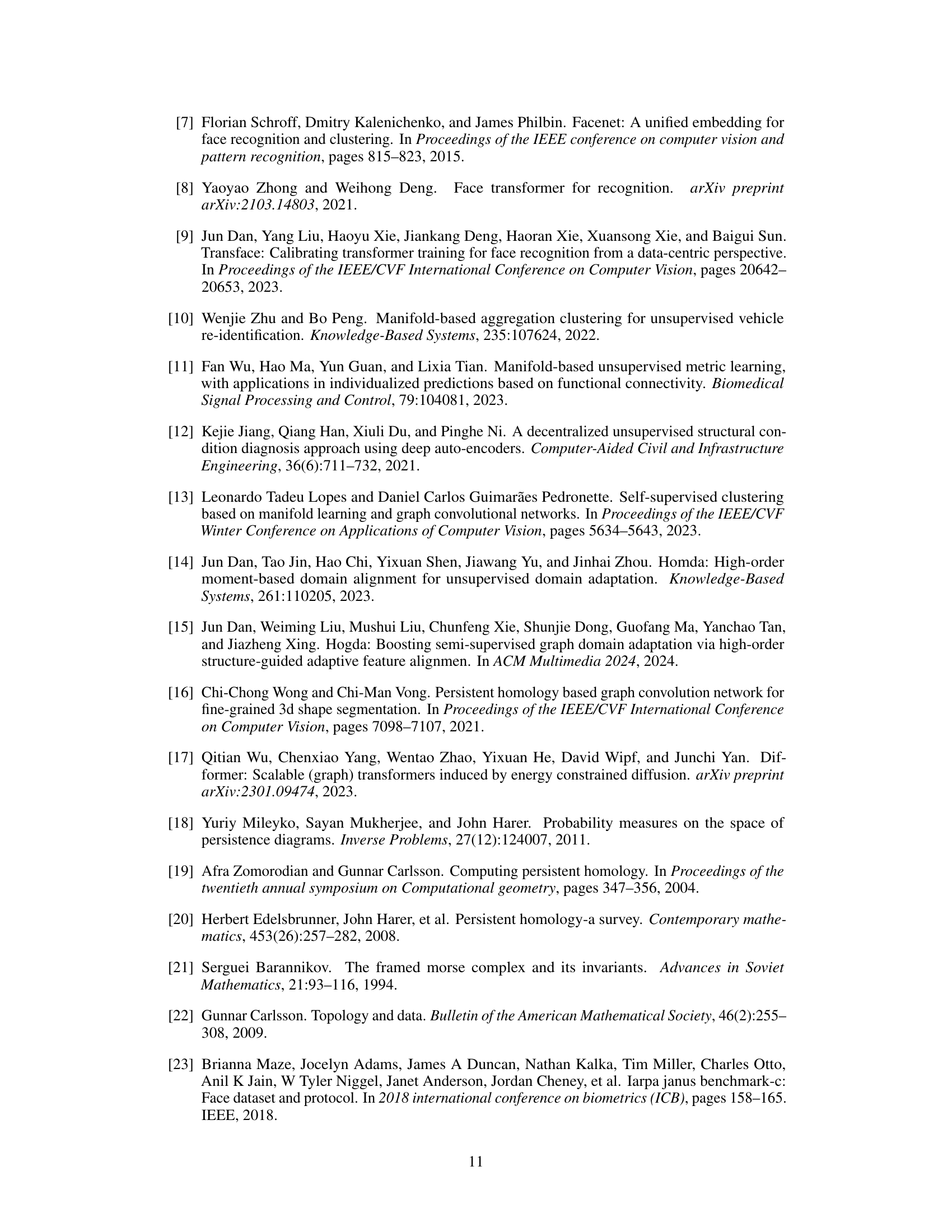

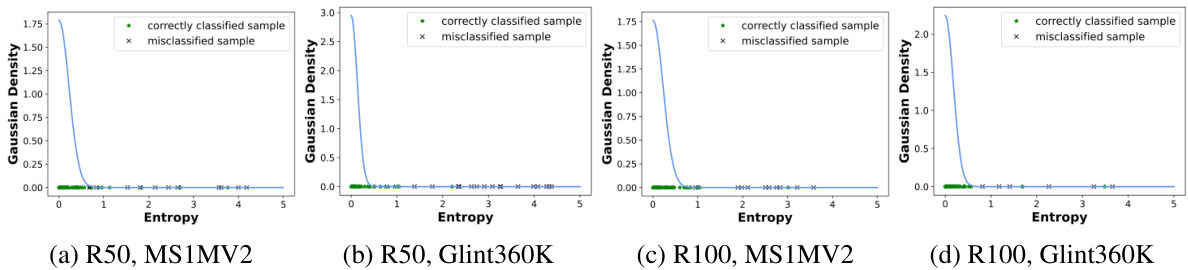

This figure compares the topological structure discrepancy between TopoFR and TopoFR-A (a variant that directly uses PH for alignment) under different network backbones (R50, R100, R200) and training datasets (MS1MV2, Glint360K). TopoFR-A suffers from structure collapse, while TopoFR effectively aligns the topological structures, especially when trained on Glint360K, showing a near-perfect alignment on the IJB-C benchmark.

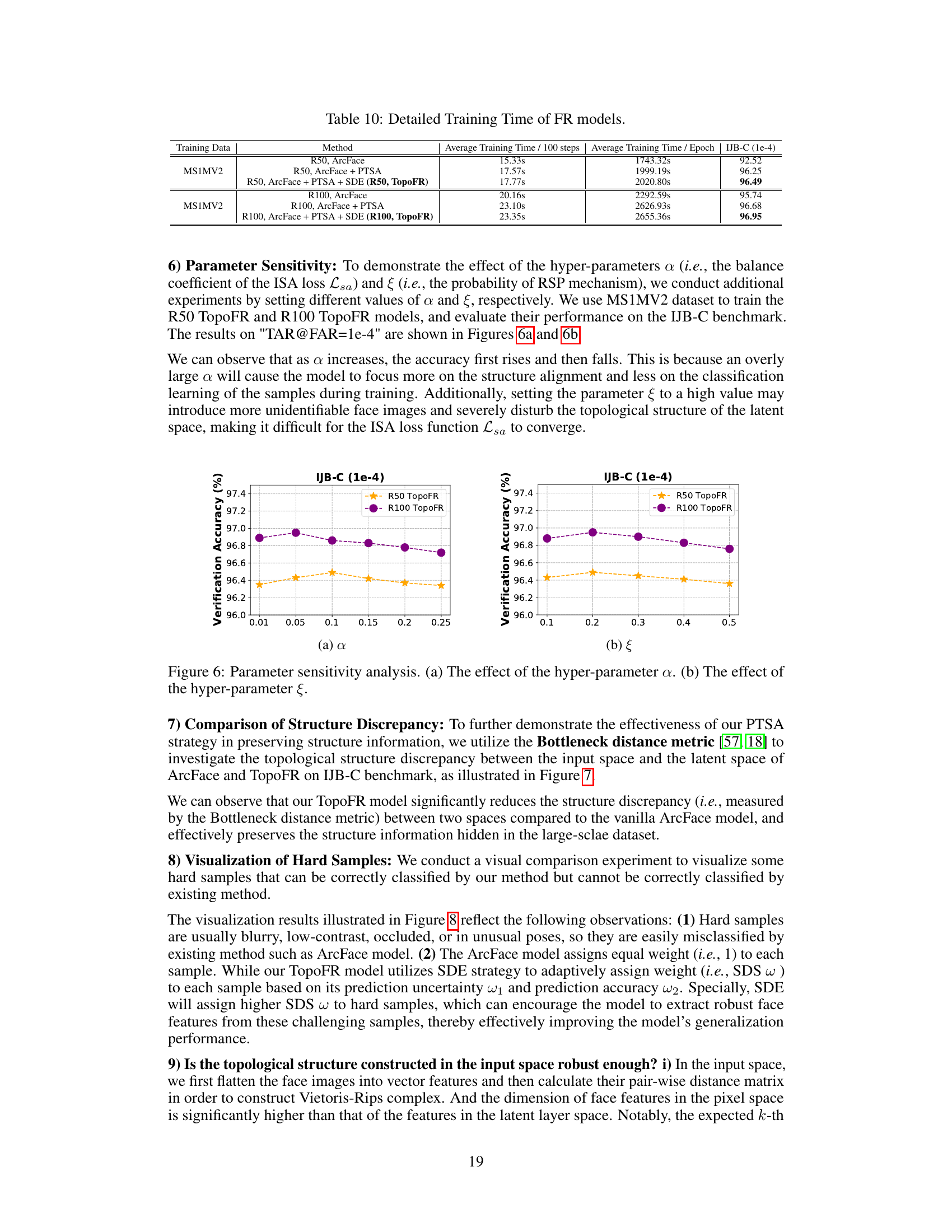

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of two hyperparameters: α (alpha) and ξ (xi). Parameter α balances the contributions of the classification loss and the topological structure alignment loss in the TopoFR model. Parameter ξ controls the probability of applying a random structure perturbation (RSP) to each training sample. The plots show the verification accuracy on the IJB-C benchmark at different values of α and ξ, demonstrating how these parameters impact the model’s performance. The optimal values of α and ξ are identified through the highest accuracy achieved, indicating the impact of structure alignment and data augmentation on the model’s generalization ability.

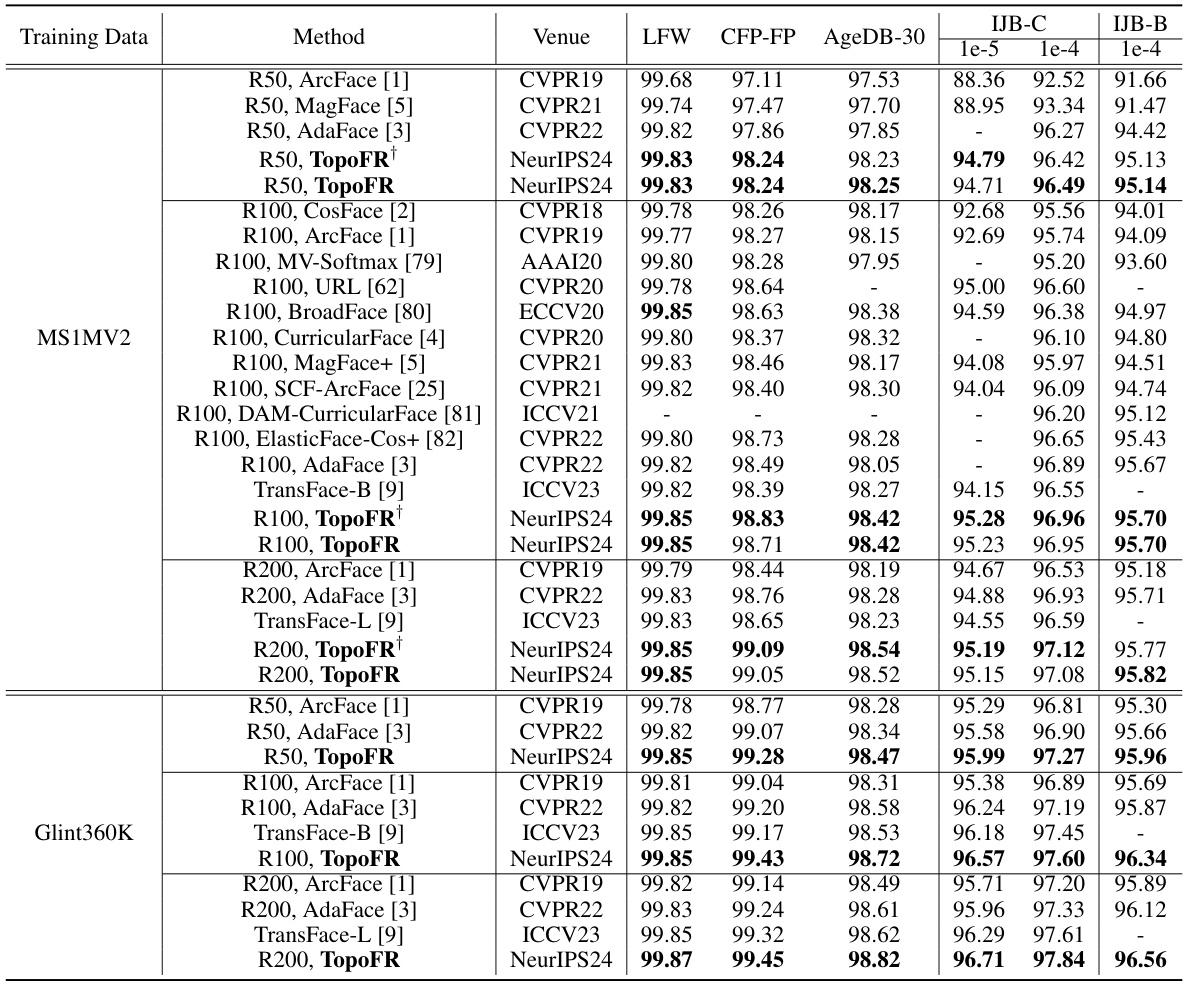

This figure compares the topological structure discrepancy between the input space and the latent space for both R50 TopoFR and R50 ArcFace models on the IJB-C benchmark. The Bottleneck distance is used as a metric to quantify this discrepancy. The histogram visually represents the distribution of these distances. A smaller bottleneck distance indicates a better alignment between the topological structures of the input and latent spaces, suggesting that TopoFR preserves the structure information more effectively than ArcFace.

This figure visualizes some hard samples that are correctly classified by TopoFR but misclassified by ArcFace. It shows that hard samples tend to be blurry, low-contrast, occluded, or in unusual poses. TopoFR uses a Structure Damage Score (SDS) to assign weights to each sample based on its prediction uncertainty and accuracy. This allows TopoFR to better handle these challenging samples, leading to improved generalization performance.

More on tables

This table presents the verification accuracy results on the Masked Face Recognition (MFR) Ongoing challenge benchmark. It compares the performance of TopoFR against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods. The results are broken down by various sub-benchmarks within MFR-Ongoing (Mask, Children, African, Caucasian, South Asian, East Asian, and Multi-Racial) as well as IJB-C (Face dataset and protocol). This allows for a detailed comparison of TopoFR’s performance in different scenarios and demographic groups.

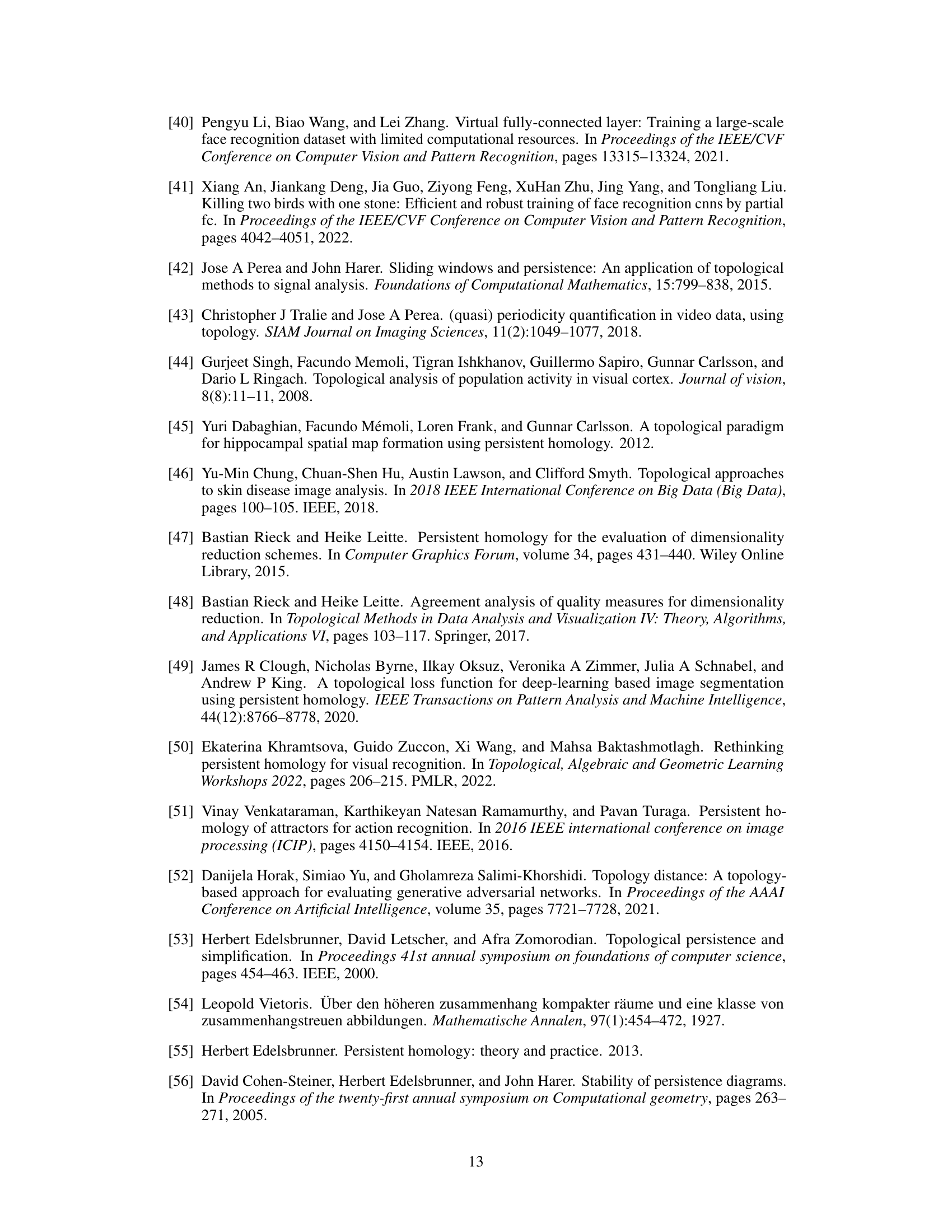

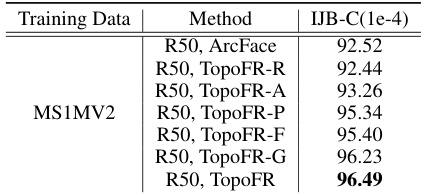

This table presents the ablation study results, comparing the performance of different variants of the TopoFR model on the IJB-C benchmark. The variants include ArcFace (baseline), TopoFR-R (with RSP), TopoFR-A (with PH alignment), TopoFR-P (with PTSA), TopoFR-F (with Focal loss), TopoFR-G (with GUM), and TopoFR (the complete model). The results show the contribution of each component to the overall performance improvement.

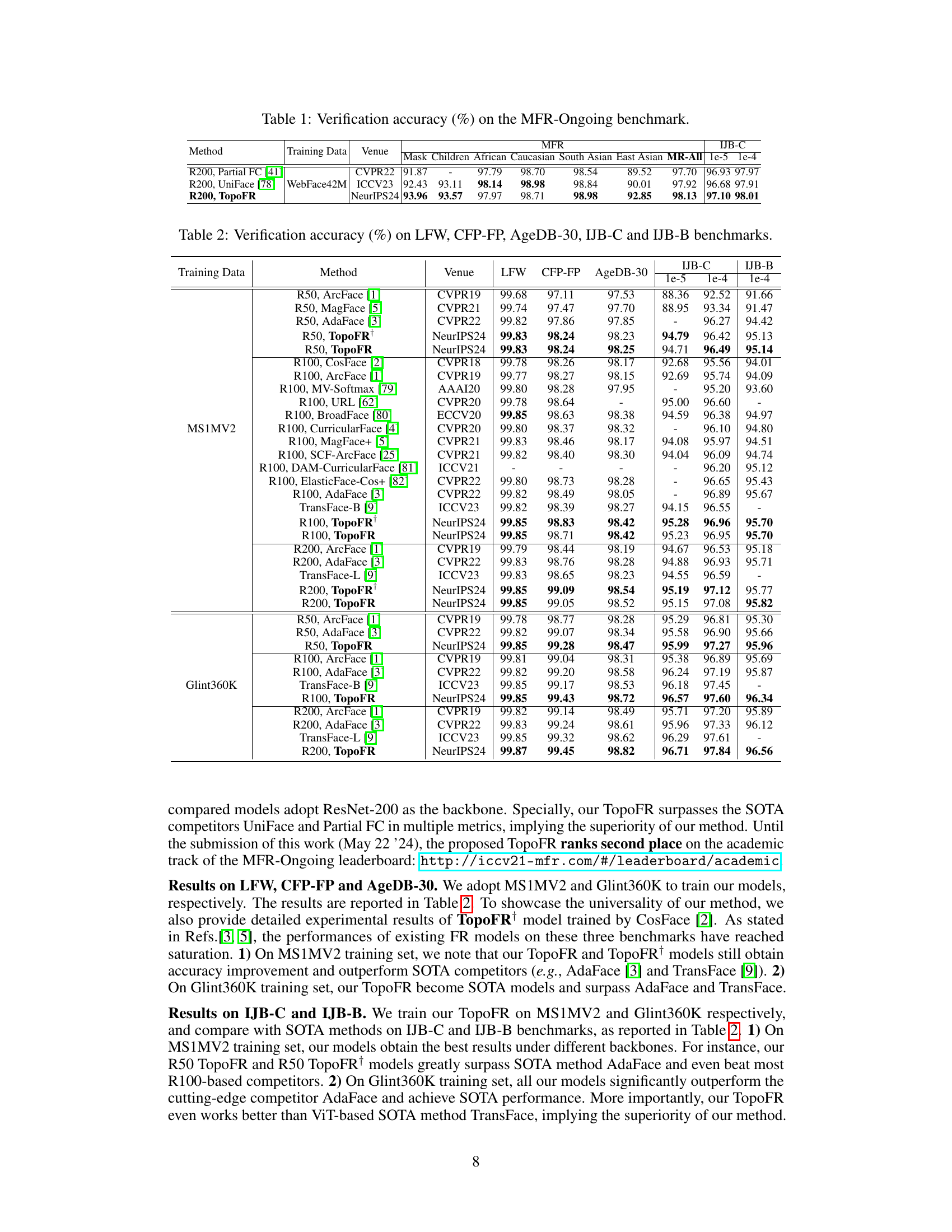

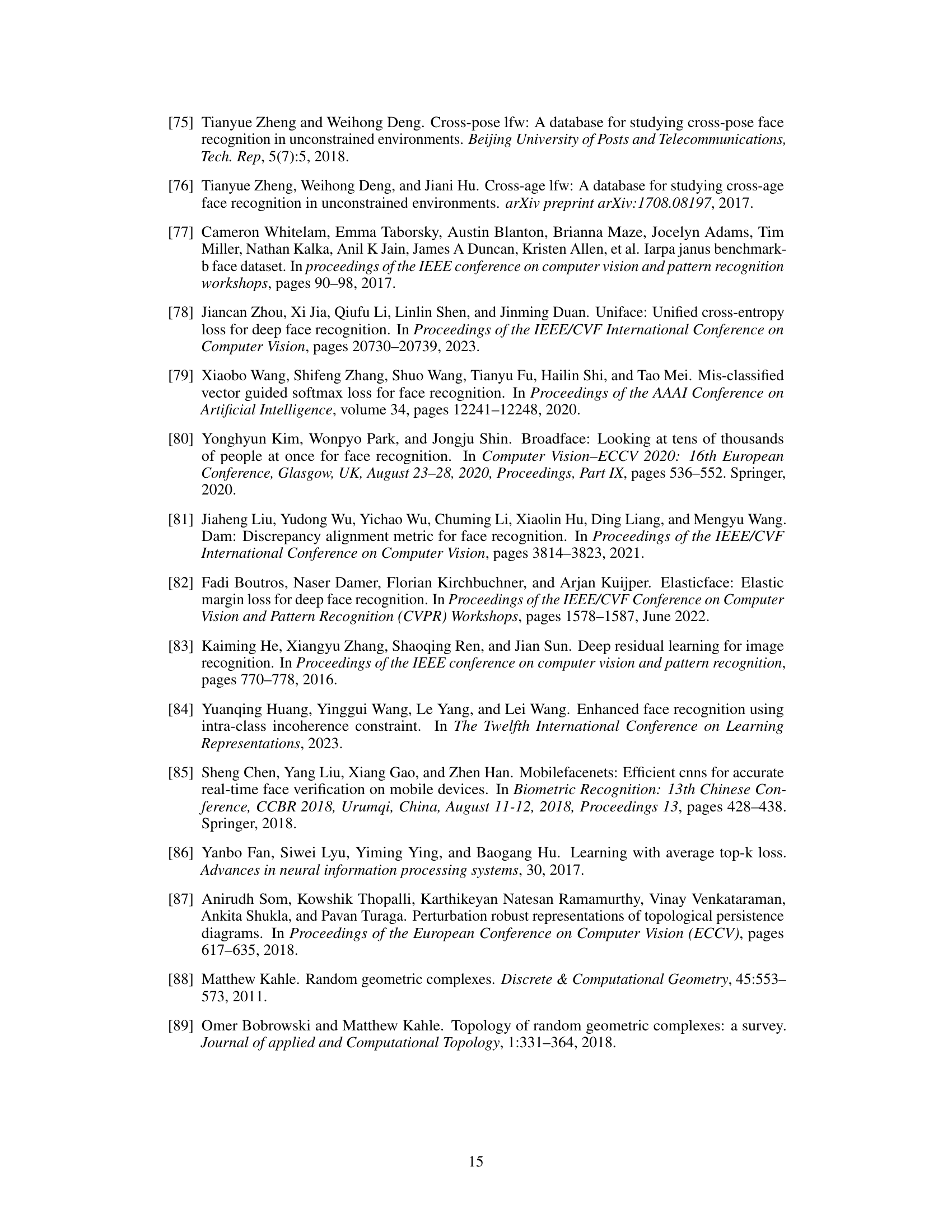

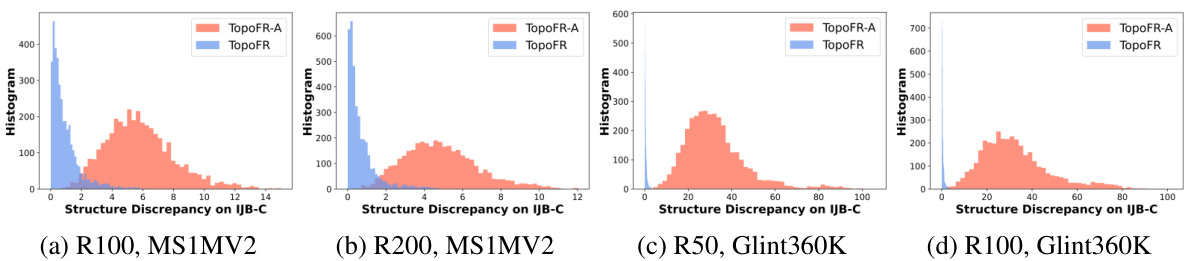

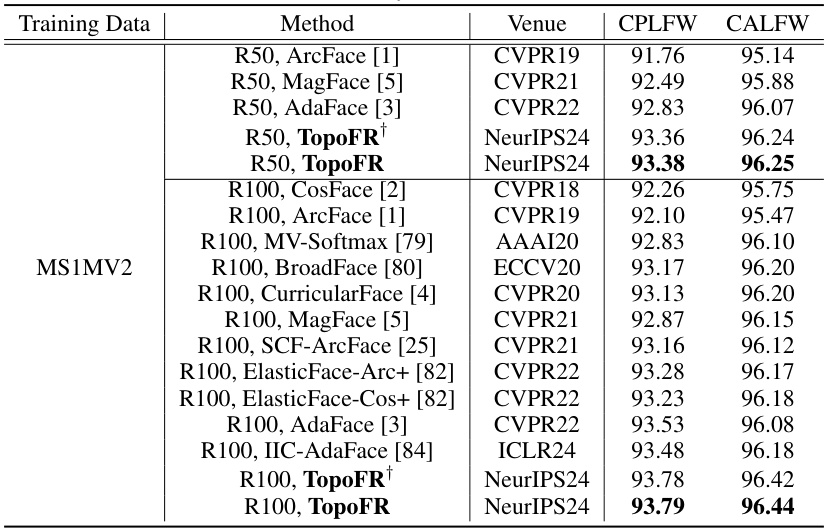

This table presents the verification accuracy achieved by various face recognition methods on five standard benchmarks: LFW, CFP-FP, AgeDB-30, IJB-C, and IJB-B. The results are broken down by the training data used (MS1MV2 and Glint360K) and the specific face recognition model. It showcases a comparison of the proposed TopoFR model against state-of-the-art methods across different network depths and datasets. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of TopoFR in achieving higher accuracy on these widely used benchmarks.

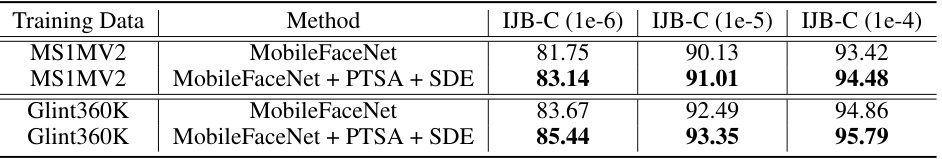

This table presents the verification performance of MobileFaceNet with and without PTSA and SDE on the IJB-C benchmark. The results show the improvement in accuracy achieved by incorporating the proposed topological structure alignment (PTSA) and hard sample mining (SDE) strategies. Two different training datasets, MS1MV2 and Glint360K, are used to train the models, demonstrating the robustness and generalization ability of the approach across different datasets.

This table presents the verification accuracy on the IJB-C benchmark dataset at three different false acceptance rates (FARs): 1e-6, 1e-5, and 1e-4. It compares the performance of R100, ArcFace with and without topological constraints. The experiments are divided into two groups: one with intra-class distance constraints removed, and another with inter-class distance constraints removed. In each case, the impact of adding a topological constraint is evaluated, demonstrating how topological structure alignment enhances performance.

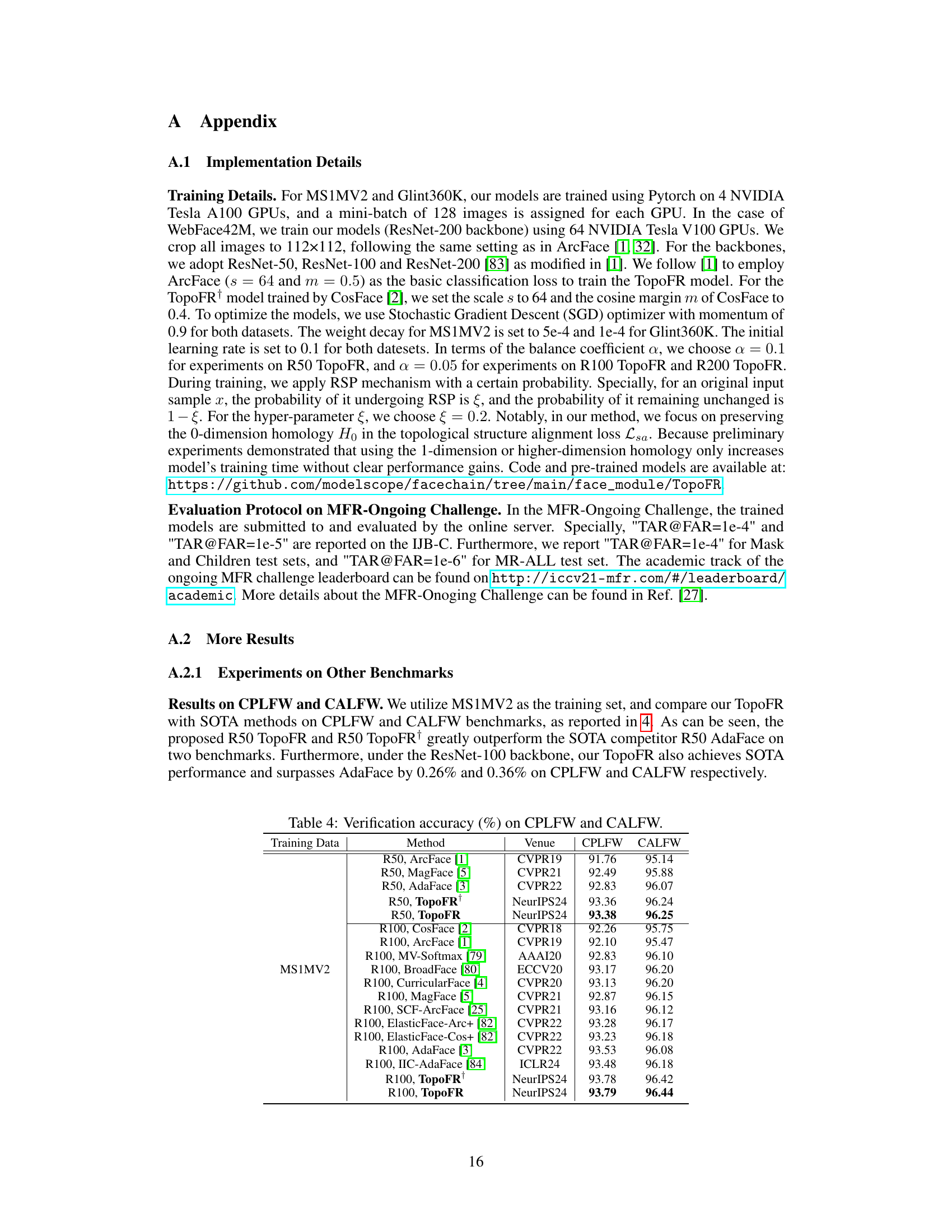

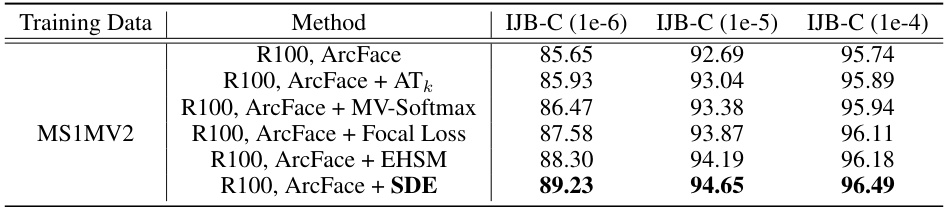

This table compares the performance of the proposed Structure Damage Estimation (SDE) method with other hard sample mining strategies (MV-Softmax, ATk loss, Focal Loss, and EHSM) on the IJB-C benchmark using ResNet-100 and MS1MV2 training data. The results show SDE outperforms existing methods in terms of verification accuracy at various false acceptance rates (FARs). This demonstrates SDE’s effectiveness in identifying and addressing hard samples to improve model generalization.

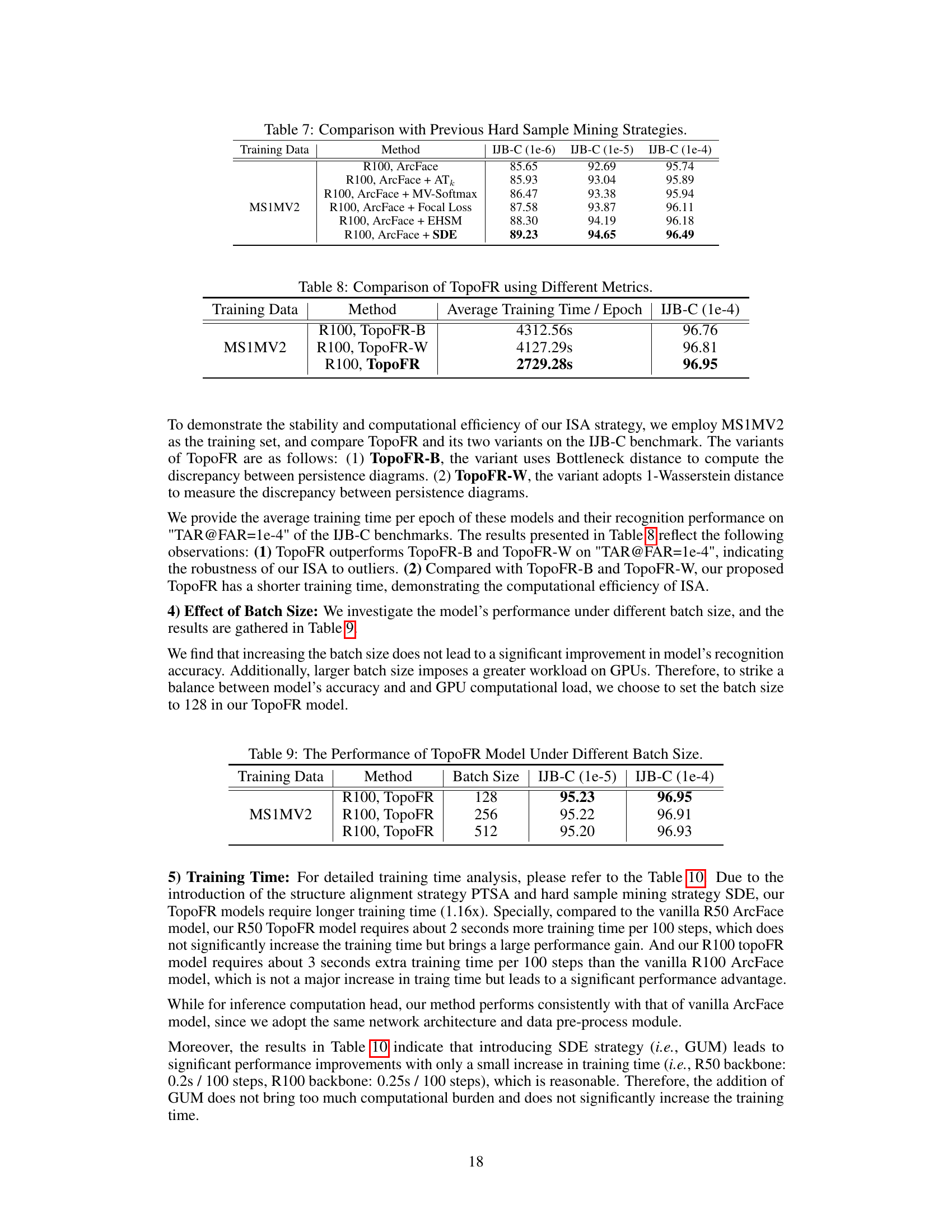

This table compares the performance and training time of three variants of the TopoFR model on the IJB-C benchmark. The variants differ in the metric used for measuring the topological structure discrepancy between input and latent spaces: Bottleneck distance (TopoFR-B), 1-Wasserstein distance (TopoFR-W), and the proposed method (TopoFR). The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves the highest accuracy (96.95%) while also exhibiting the lowest training time (2729.28 seconds per epoch).

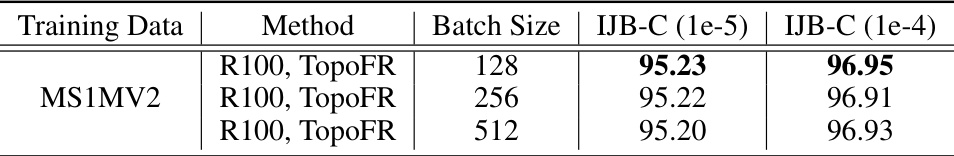

This table presents the performance of the TopoFR model on the IJB-C benchmark under different batch sizes (128, 256, and 512). The results show that varying the batch size does not significantly affect the model’s accuracy on this benchmark.

This table presents the average training time per 100 steps and per epoch for different face recognition (FR) models. It compares the training time of standard ArcFace models with TopoFR models (with and without PTSA and SDE). The results are broken down by ResNet-50 (R50) and ResNet-100 (R100) backbones and show the impact of the proposed methods on training efficiency. The IJB-C (1e-4) column shows the verification accuracy achieved by each model on the IJB-C benchmark at a False Acceptance Rate (FAR) of 1e-4. This demonstrates that the efficiency gains from TopoFR do not come at the cost of accuracy.

Full paper#