↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

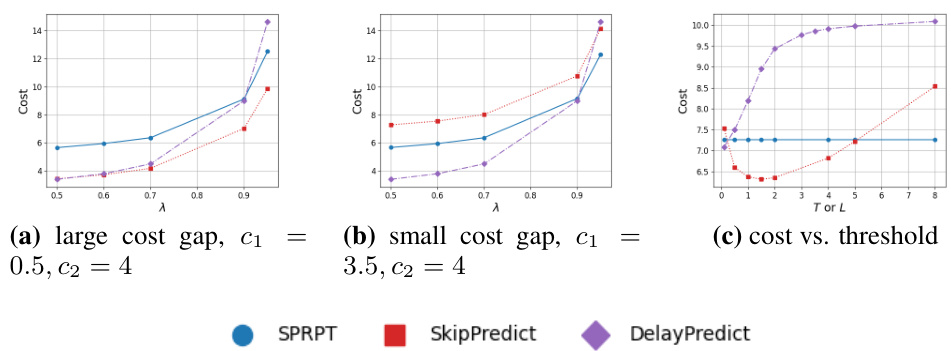

TL;DR#

Existing research on scheduling often assumes predictions are free. However, obtaining predictions incurs costs, which may outweigh the benefits. This paper addresses this limitation by analyzing the effects of prediction costs on scheduling performance. It also introduces the practical implications of the cost of predictions for queueing systems and challenges existing assumptions in prior research.

To tackle this, the paper introduces SkipPredict, a new scheduling policy that strategically uses predictions. SkipPredict categorizes jobs as short or long using a cheap prediction and prioritizes short jobs. For long jobs, more expensive predictions are applied to further optimize scheduling. The authors derive closed-form formulas to calculate mean response times considering prediction costs and demonstrate SkipPredict’s effectiveness using both real-world and synthetic datasets through comprehensive analysis and simulation. SkipPredict outperforms existing methods by reducing costs, especially when there’s a significant cost difference between cheap and expensive predictions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical gap in existing research on scheduling algorithms by explicitly considering the cost of predictions. This is highly relevant to real-world applications where prediction costs are significant, such as data centers and cloud computing. The findings could lead to more efficient and cost-effective scheduling strategies in various resource-constrained environments. The introduction of SkipPredict provides a new direction for future research into cost-aware learning-augmented algorithms.

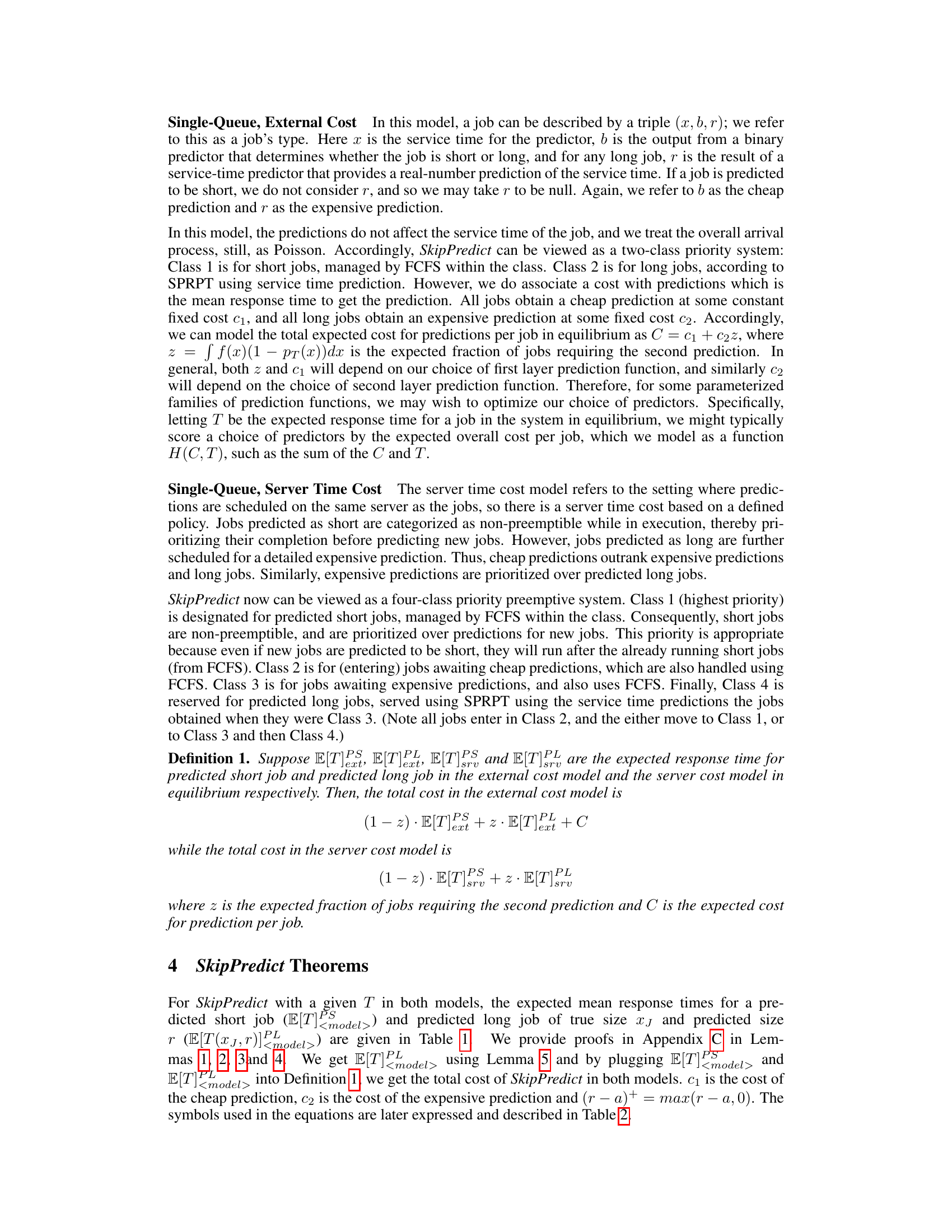

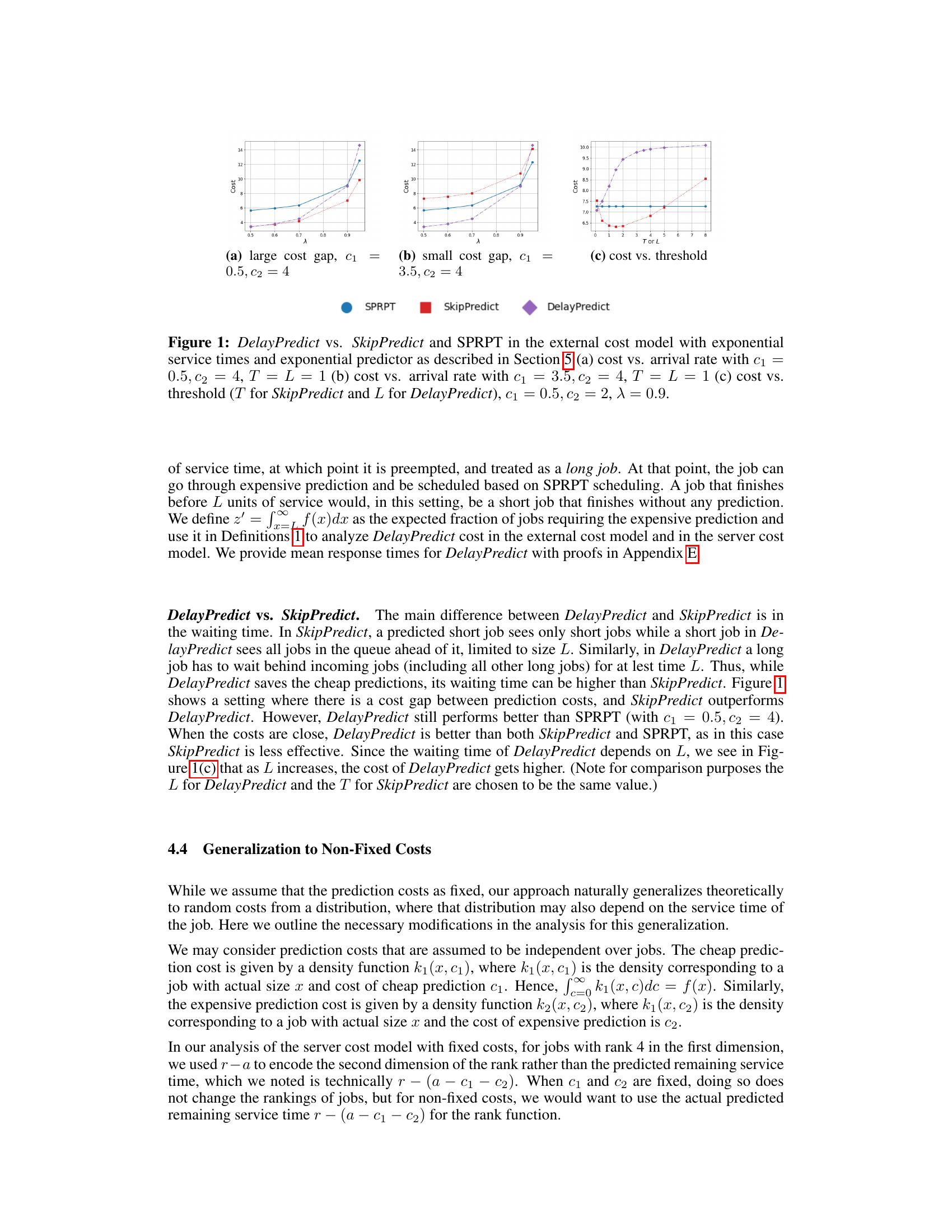

Visual Insights#

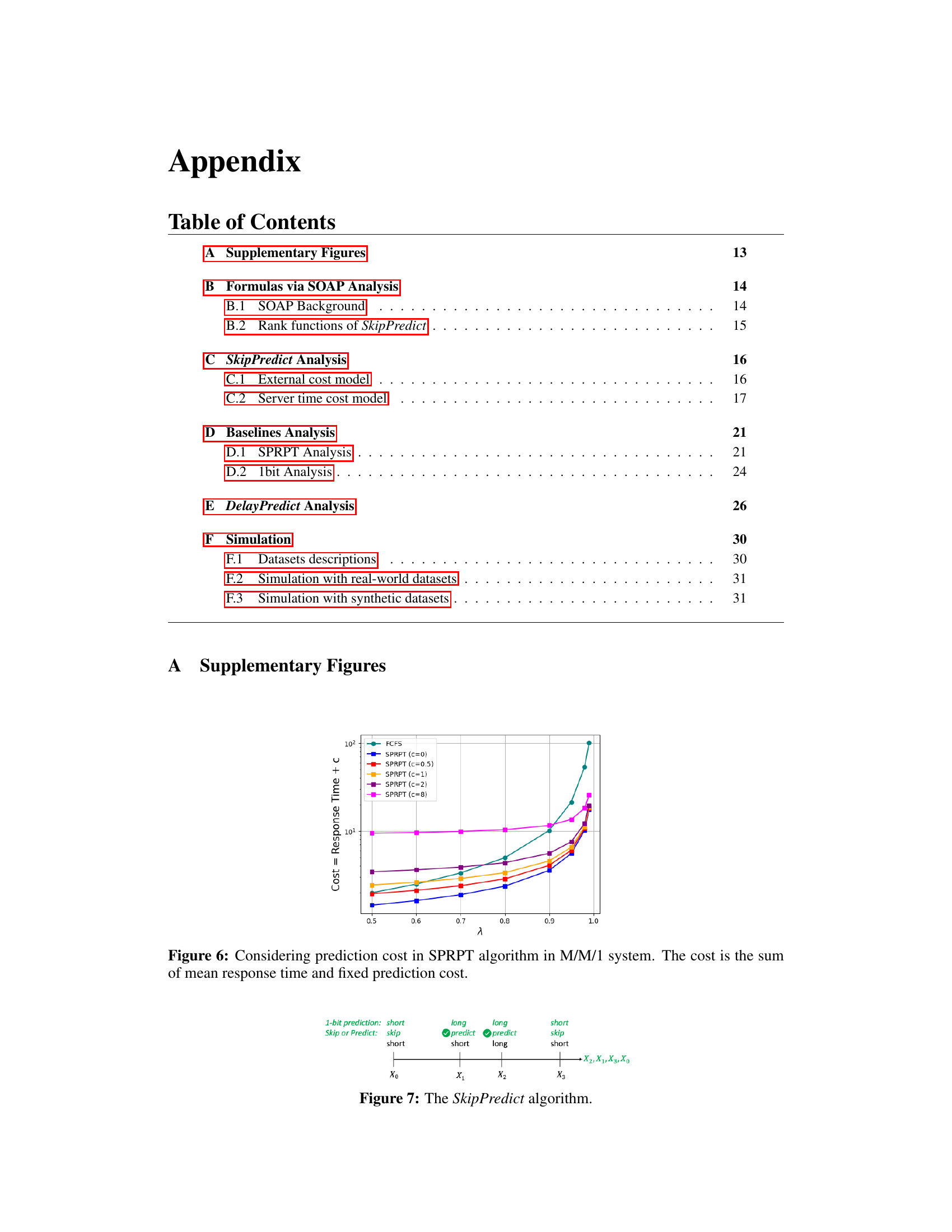

This figure compares the performance of three scheduling policies: SkipPredict, SPRPT, and DelayPredict under the external cost model with exponentially distributed service times and an exponential predictor. It shows cost versus arrival rate (λ) for two different cost scenarios (large and small cost gaps between cheap and expensive predictions) and cost versus the threshold (T or L) for a specific arrival rate (λ = 0.9). The figure helps illustrate how the choice of scheduling policy and the cost of predictions impact the overall cost of the queueing system.

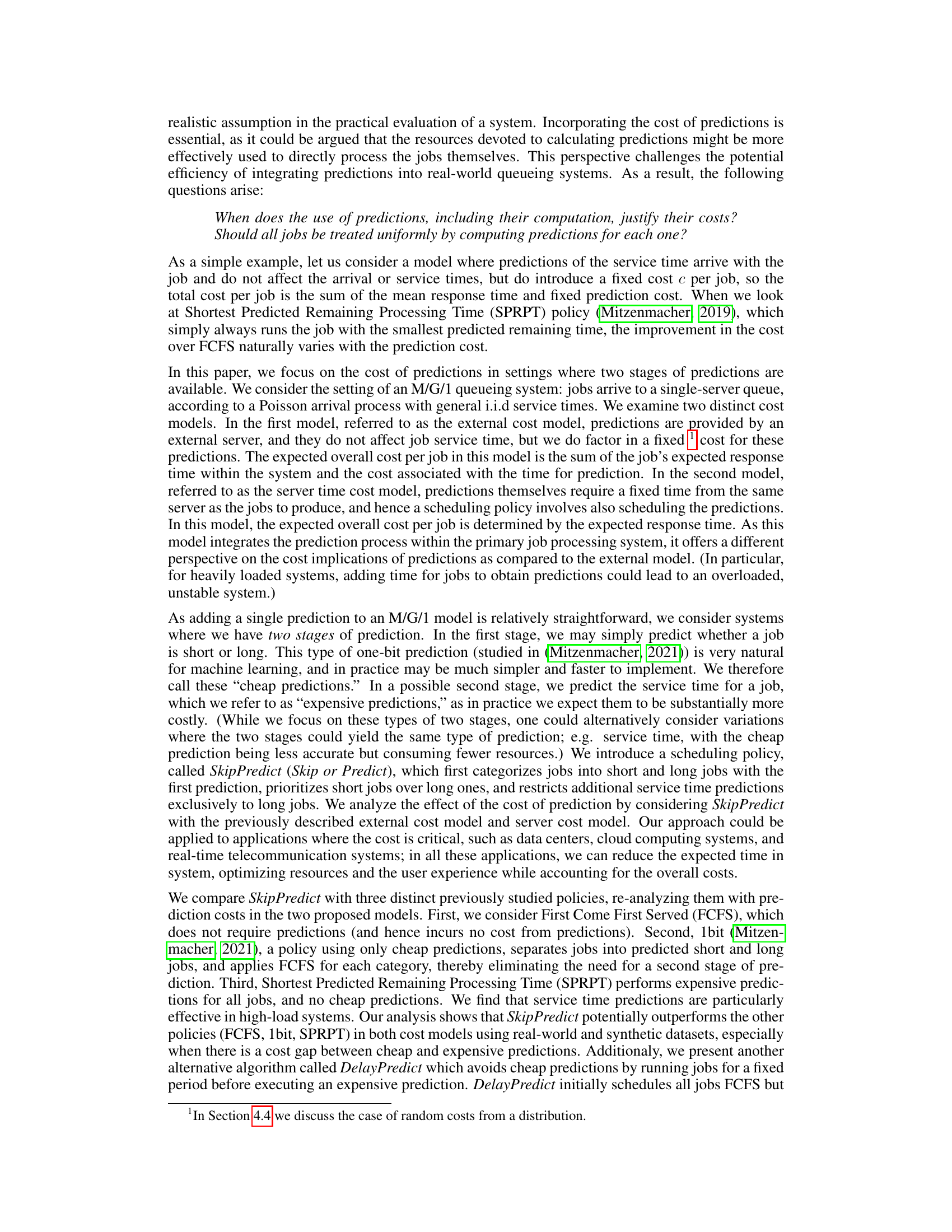

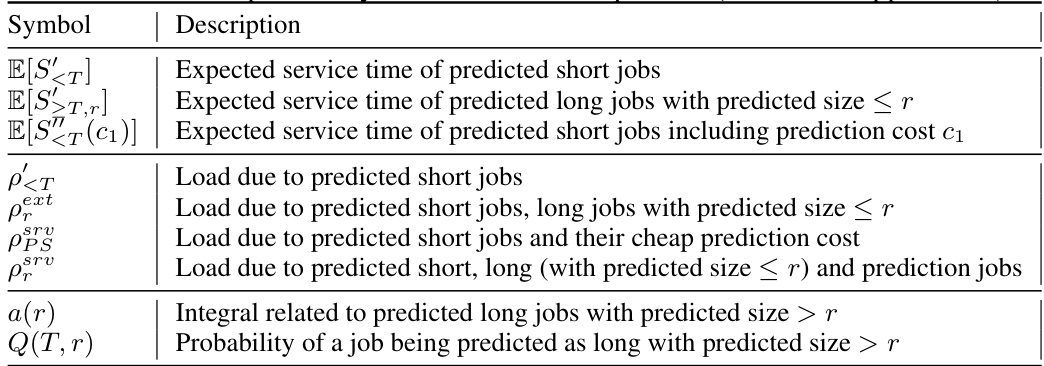

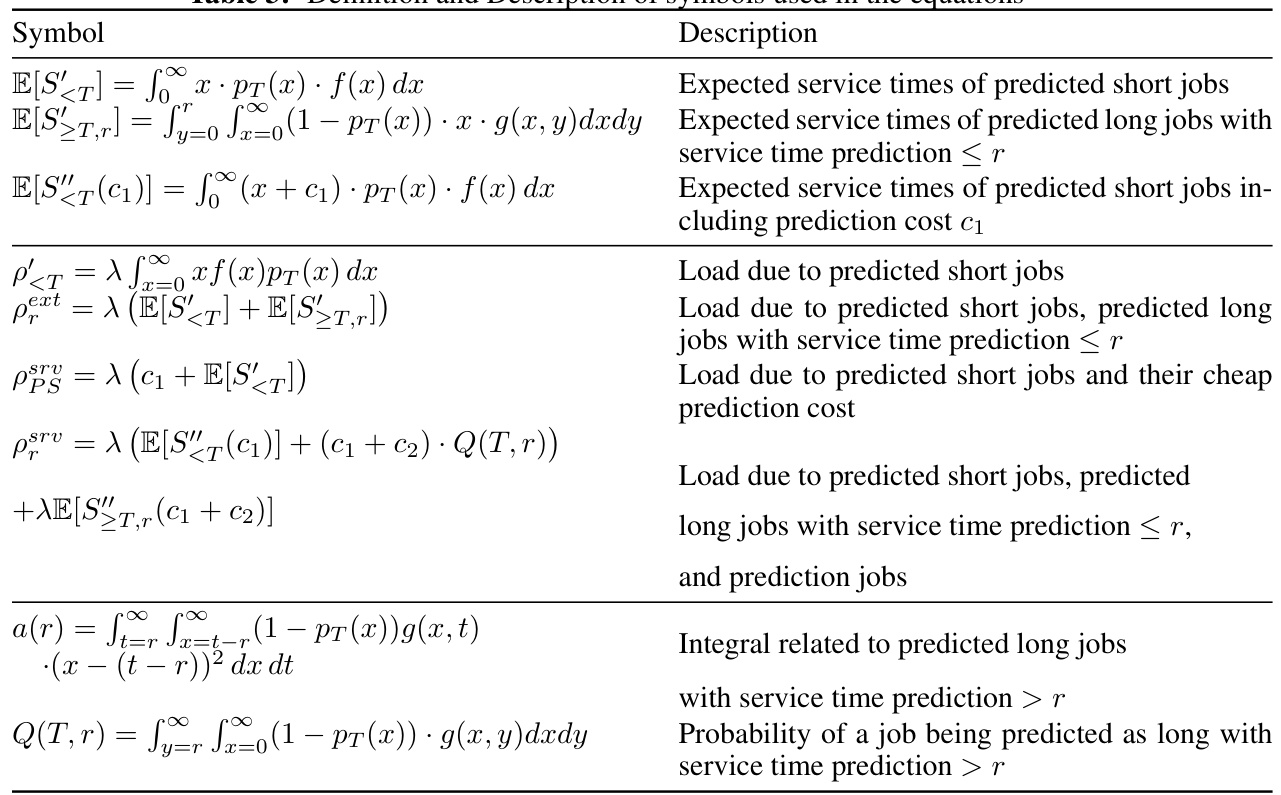

This table presents the core equations for calculating the expected mean response times for predicted short and long jobs within the SkipPredict scheduling algorithm. It shows separate formulas for both an external cost model (where prediction costs are independent of job processing) and a server time cost model (where prediction processing time consumes server resources). For short jobs, the equations are relatively straightforward. For long jobs, the equations are more complex, incorporating additional factors related to preemption and the distribution of predicted service times.

In-depth insights#

Prediction Cost Models#

The core of this research lies in its novel approach to handling prediction costs in scheduling algorithms. The authors cleverly avoid the typical assumption of free predictions by introducing two distinct cost models: an external cost model, where predictions are generated by an external server incurring a fixed cost per prediction; and a server time cost model, where prediction generation consumes server processing time, impacting job scheduling. This dual-model approach offers a more realistic and nuanced perspective on prediction costs in real-world systems. The choice between these models affects not only the total expected cost but also the overall system stability, particularly under heavy load. By incorporating the cost of prediction, the authors enable a more comprehensive evaluation of scheduling policies, allowing for comparisons that reflect real-world resource constraints and operational expenses. This meticulous modeling is a key strength of the paper, offering valuable insights into the practical trade-offs involved in using prediction-augmented scheduling algorithms.

SkipPredict Algorithm#

The SkipPredict algorithm presents a novel approach to scheduling in queueing systems by strategically using predictions to improve efficiency. Instead of uniformly applying predictions to all jobs, it categorizes jobs as ‘short’ or ’long’ using inexpensive, one-bit predictions. This categorization allows SkipPredict to prioritize predicted short jobs while applying more costly, detailed predictions only to the longer jobs. This two-stage approach addresses the inherent cost of predictions, a crucial factor often overlooked in previous research. The algorithm considers two distinct cost models: an external cost model where predictions are generated externally and a server time cost model where prediction generation consumes server resources. SkipPredict’s effectiveness is analyzed through closed-form formulas that incorporate prediction costs, ultimately aiming to minimize the overall cost (response time + prediction cost). The key insight is that using predictions judiciously based on predicted job length yields cost savings and improves performance, especially in high-load settings. The algorithm’s performance is also compared to other standard scheduling policies, highlighting its potential advantages in resource-constrained environments.

Multi-Stage Predictions#

The concept of “Multi-Stage Predictions” in scheduling algorithms offers a powerful approach to balancing prediction accuracy and resource consumption. A multi-stage approach allows for a hierarchical refinement of predictions, starting with quick, inexpensive methods to filter out easily-classified jobs, such as short ones. Subsequently, more computationally intensive methods can be selectively applied to the more challenging cases. This strategy addresses the trade-off between improved scheduling performance—enabled by better predictions—and the cost associated with prediction itself. Efficient categorization and prioritization are essential; for example, prioritizing jobs likely to be short based on cheap predictions can significantly decrease overall response time. Analyzing the cost of predictions is crucial; different cost models (e.g., external vs. server-time cost) can reveal different optimal strategies. The effectiveness of multi-stage predictions hinges on the reliability and cost of each stage; poor prediction accuracy, particularly in early stages, could negate the benefits, potentially leading to worse performance than using no predictions at all. Furthermore, the design should incorporate robustness to prediction inaccuracies to avoid catastrophic failures due to unreliable predictions.

Real-World Datasets#

The utilization of real-world datasets is crucial for evaluating the practical applicability and effectiveness of the SkipPredict algorithm. The paper leverages three diverse real-world datasets: TwoSigma, Google, and Trinity. TwoSigma offers insights into financial data analytics, Google provides a broader perspective on general-purpose workloads, while Trinity focuses on high-performance computing environments. This variety is important as it allows for a more robust evaluation across a wider range of job characteristics and system conditions, showing the generalizability of SkipPredict beyond synthetic scenarios. The inclusion of real-world data significantly strengthens the paper’s claims, demonstrating the potential impact of SkipPredict on actual performance in different settings. However, the paper should also discuss any limitations imposed by the real-world data, especially concerning data quality, potential biases, or any constraints that might affect the results.

Cost-Accuracy Tradeoff#

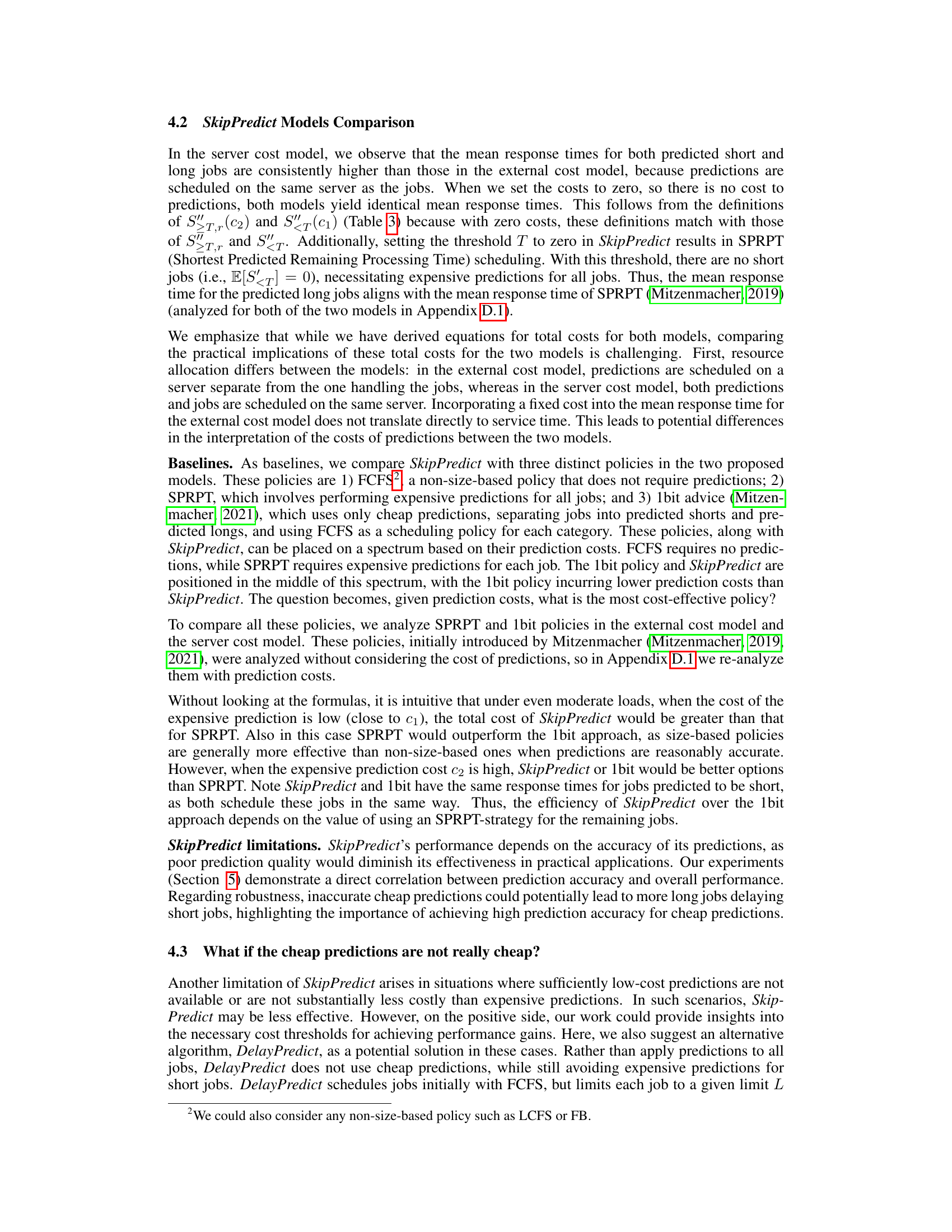

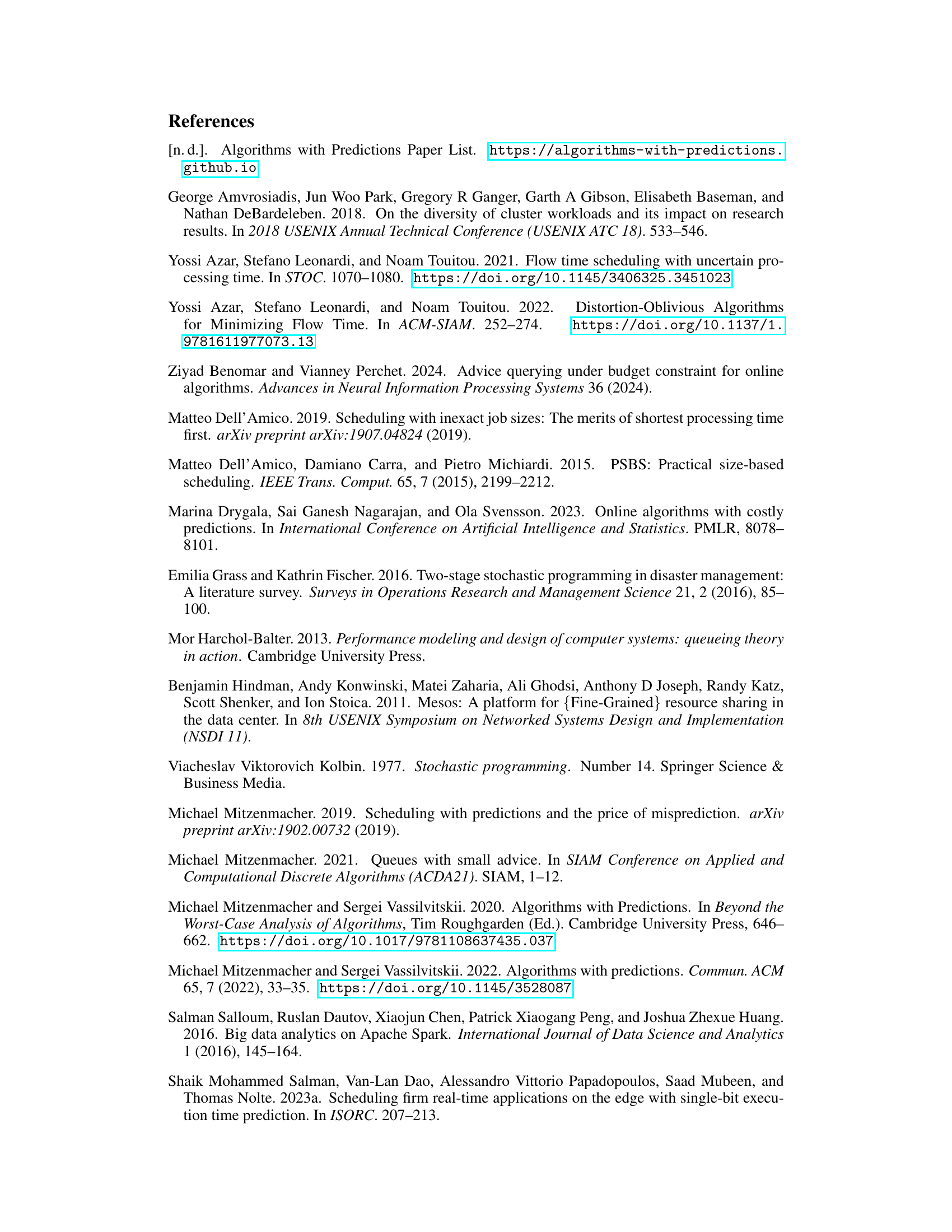

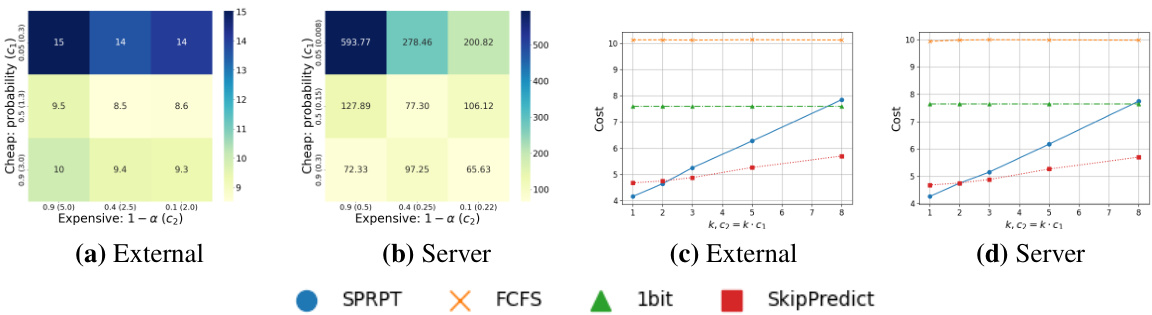

The Cost-Accuracy Tradeoff section is crucial for assessing the practical applicability of the SkipPredict algorithm. It acknowledges that prediction accuracy directly impacts performance. Higher accuracy generally leads to better scheduling decisions but comes with higher costs. The authors astutely investigate this tradeoff by experimentally varying prediction accuracy levels and associating them with their corresponding costs. This allows for a nuanced cost-benefit analysis, demonstrating that SkipPredict’s effectiveness is particularly pronounced when there’s a significant cost gap between cheap and expensive predictions. When the difference in cost is minimal, simpler, less expensive strategies might be superior. The experimental heatmap visualizations effectively illustrate this tradeoff, revealing the optimal balance point for specific accuracy-cost combinations. This detailed analysis highlights the practical considerations necessary for deploying prediction-based scheduling and contributes significantly to the practical value of the proposed algorithm.

More visual insights#

More on figures

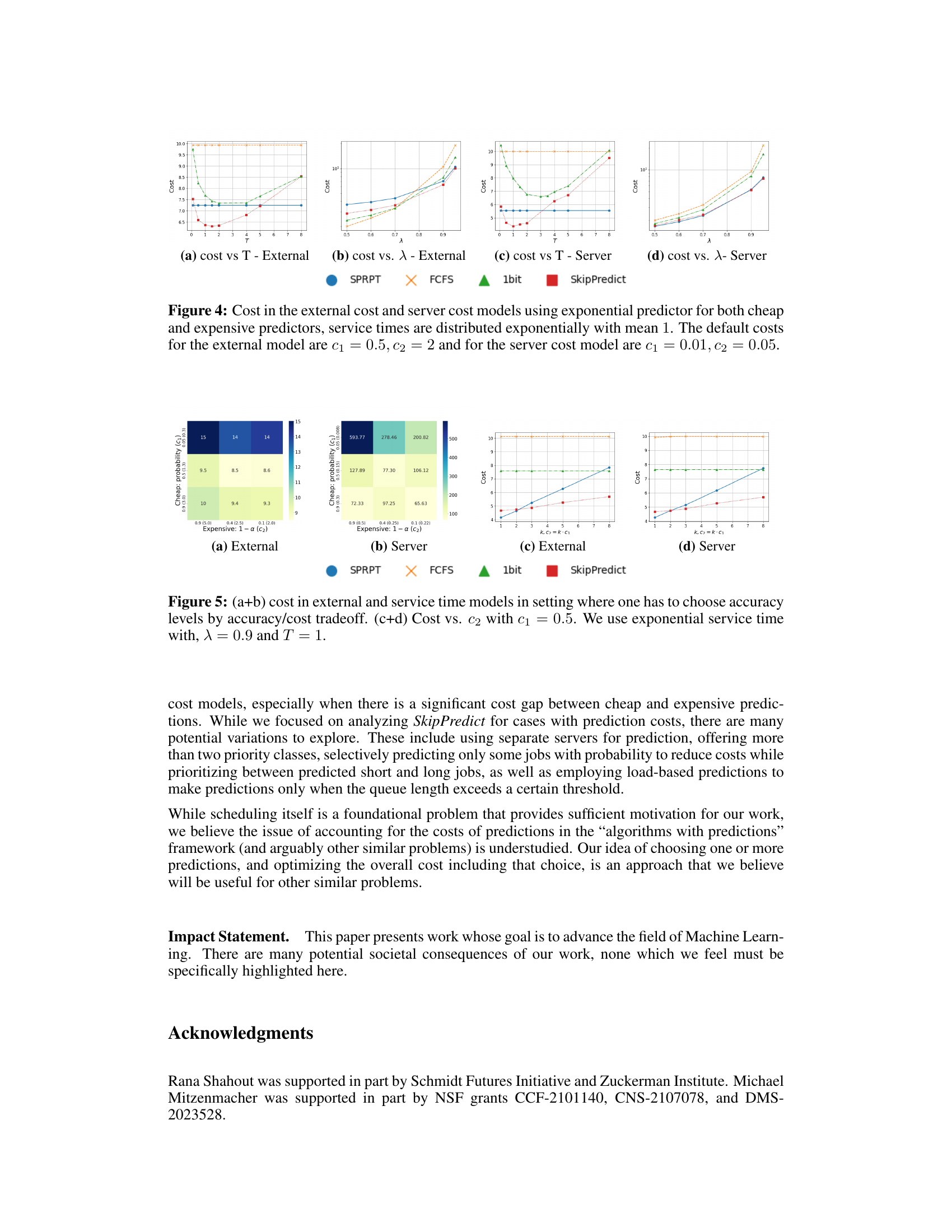

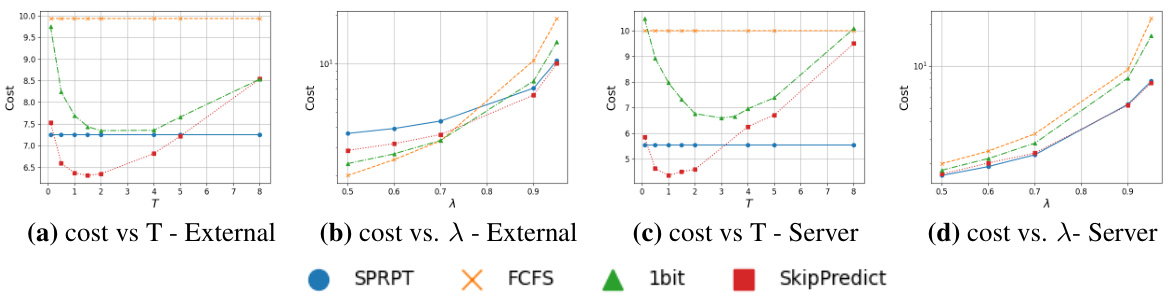

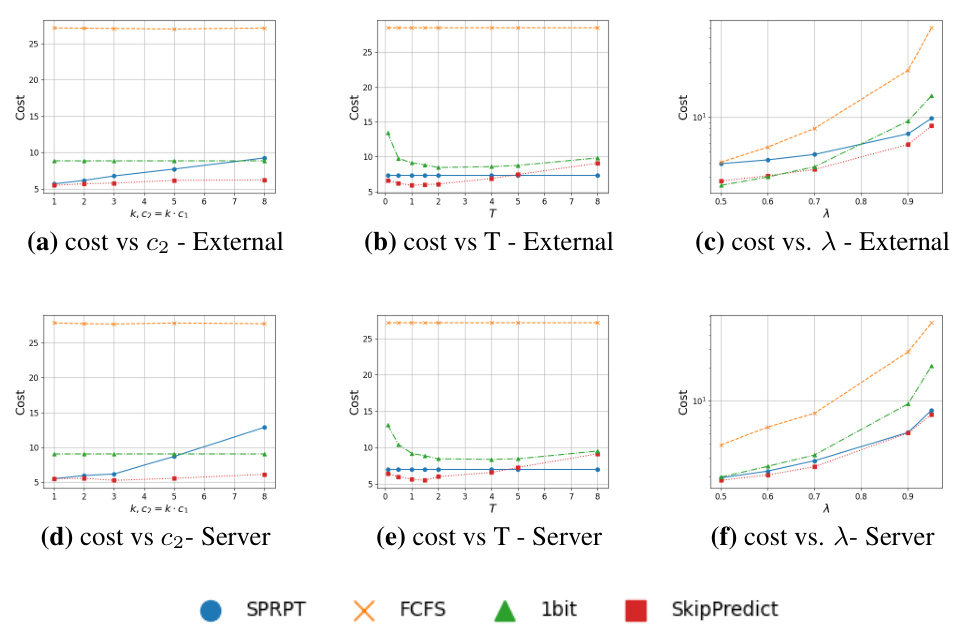

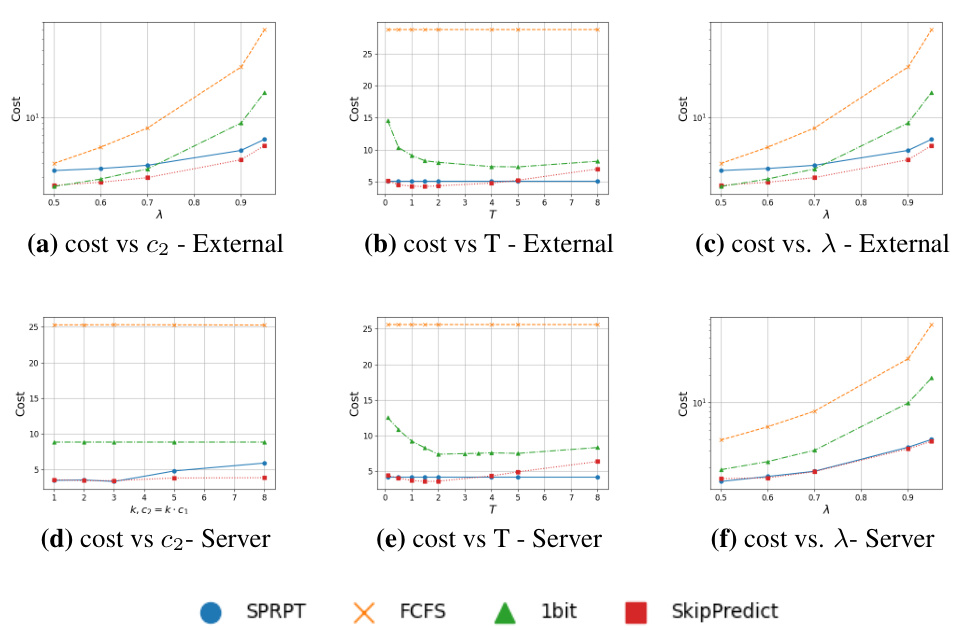

This figure compares the cost of different scheduling policies (SPRPT, FCFS, 1bit, SkipPredict) across two cost models (external cost and server time cost) using real-world datasets (TwoSigma, Google, Trinity). Subplots (a) through (f) show the cost versus the arrival rate (λ) for each dataset and cost model, with T (threshold) fixed at 4. Subplots (g) and (h) specifically focus on the Trinity dataset and illustrate the relationship between cost and the threshold T, with the arrival rate (λ) set to 0.6. Different colors represent different scheduling policies. The default prediction costs (c1 and c2) are specified for both models.

This figure compares the performance of three scheduling policies: SkipPredict, DelayPredict, and SPRPT, under the external cost model with exponential service times. The x-axis and y-axis represent the arrival rate (λ) and cost, respectively. The three subfigures show the cost-effectiveness of the policies under different parameter settings. (a) shows the effect of arrival rate on cost when there is a large difference between the cost of cheap and expensive predictions. (b) shows the impact of arrival rate on cost when the difference is small. (c) demonstrates how the choice of the threshold (T for SkipPredict and L for DelayPredict) affects the overall cost. The results illustrate that the choice of policy significantly impacts cost-effectiveness depending on the system parameters and the cost differential between prediction types.

This figure compares the performance of three scheduling policies: DelayPredict, SkipPredict, and SPRPT, under the external cost model with exponential service times and an exponential predictor. The comparison is shown across different arrival rates (λ) and threshold values (T for SkipPredict, L for DelayPredict). Subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate the cost versus arrival rate with different cost gaps between cheap and expensive predictions (c₁ and c₂), while subfigure (c) depicts how the cost varies with the threshold. The figure shows that the optimal policy depends on the cost of predictions and the system load.

This figure displays the cost trade-off analysis of SkipPredict against other scheduling policies (SPRPT, FCFS, and 1bit). Subfigures (a) and (b) are heatmaps showing the total cost for different combinations of cheap prediction accuracy and expensive prediction accuracy in the external and server cost models, respectively. Subfigures (c) and (d) are line graphs showing the cost versus the expensive prediction cost (C2) in both models. The plots illustrate how SkipPredict’s cost-effectiveness changes depending on the accuracy of predictions and the relative costs of cheap and expensive predictions. The results highlight that SkipPredict is particularly beneficial when there’s a significant cost difference between the two types of predictions.

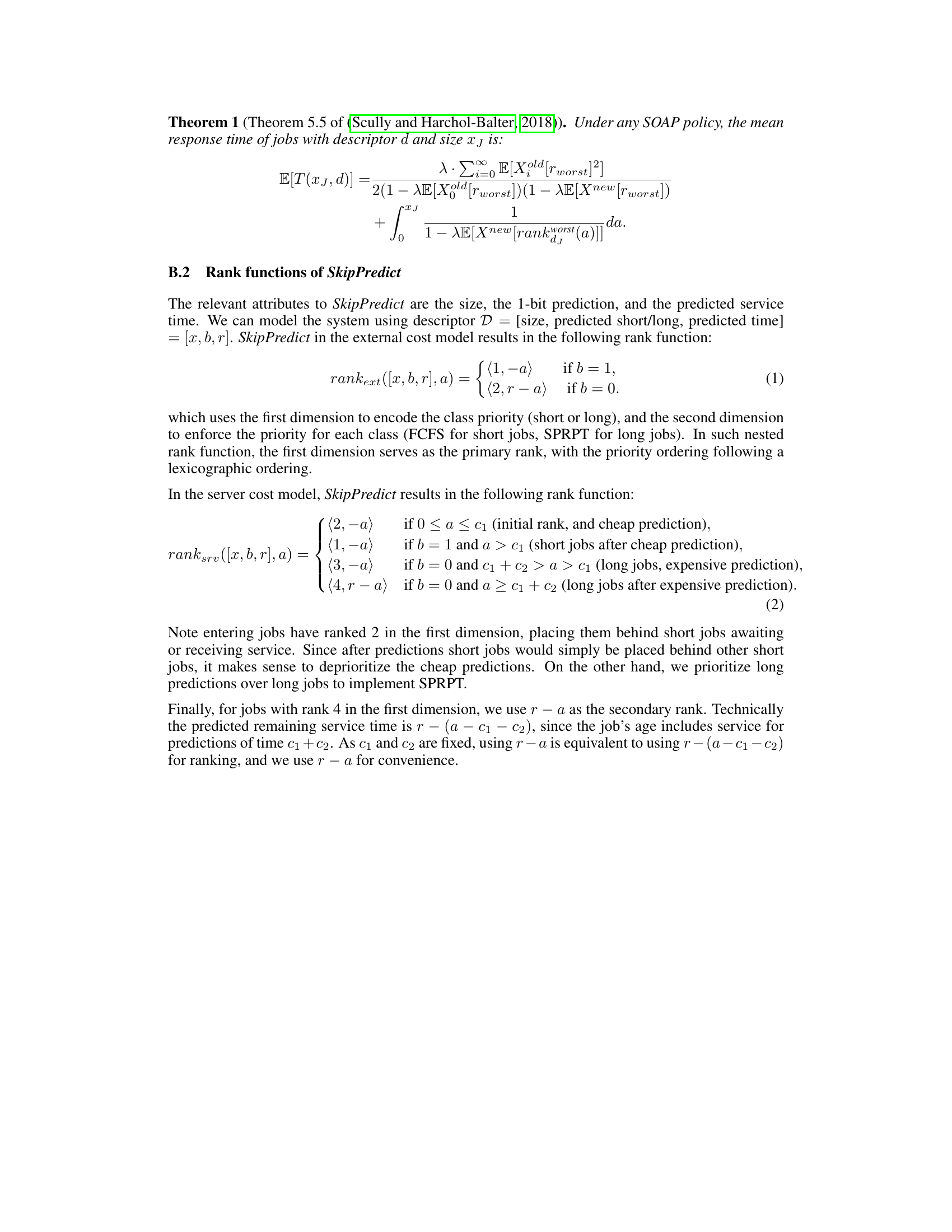

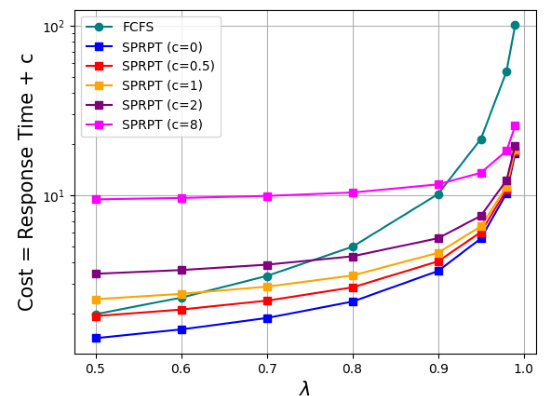

This figure illustrates the impact of prediction costs on the performance of the Shortest Predicted Remaining Processing Time (SPRPT) scheduling algorithm in an M/M/1 queueing system. The x-axis represents the arrival rate (λ), and the y-axis shows the total cost, which is the sum of the mean response time and a fixed prediction cost (c). Multiple lines are shown, each representing a different fixed prediction cost (c = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 8). The figure demonstrates how the total cost increases with the arrival rate and the prediction cost.

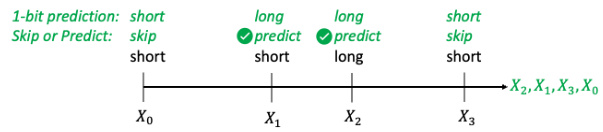

This figure illustrates the SkipPredict algorithm’s operation. It shows a timeline where jobs arrive sequentially. For each job, a 1-bit prediction determines if it’s short or long. SkipPredict then decides whether to skip further prediction (if short) or perform an expensive prediction to obtain an accurate predicted time (if long). The algorithm prioritizes short jobs. The figure visually represents how jobs are categorized and scheduled based on the cheap prediction, and how additional expensive predictions are strategically applied to longer jobs only.

This figure compares the performance of three scheduling policies: DelayPredict, SkipPredict, and SPRPT, under the external cost model with exponentially distributed service times and an exponential predictor. It explores the impact of varying arrival rates (λ) and a cost threshold (T for SkipPredict, L for DelayPredict) on overall cost. Three subfigures illustrate the cost versus arrival rate with different prediction cost gaps (c1 and c2), and a cost versus threshold comparison.

This figure compares the performance of different scheduling policies (SPRPT, FCFS, 1bit, and SkipPredict) across two cost models (external and server) using real-world datasets. Subplots (a) through (f) illustrate cost variation against the arrival rate (λ) while keeping the threshold (T) constant at 4. Subplots (g) and (h) show how cost changes with varying threshold (T) for the Trinity dataset at a fixed arrival rate (λ) of 0.6. Different line colors represent the different scheduling policies, allowing for a visual comparison of their cost-effectiveness under different conditions and datasets.

This figure presents a comparison of different scheduling policies (SPRPT, FCFS, 1bit, SkipPredict) under two cost models (external and server) when using Weibull distribution for service times and exponential predictor for both cheap and expensive predictions. The plots show the total cost (response time + prediction cost) against varying prediction cost (c2), threshold (T) and arrival rate (λ). Each plot shows the performance of the four policies under different conditions. This helps to understand the trade-off between prediction cost and scheduling performance under different parameters and system loads.

This figure compares the performance of different scheduling policies (SPRPT, FCFS, 1bit, SkipPredict) under two cost models (external and server) with Weibull distributed service times and exponential prediction models. It shows how the total cost varies with changes in the expensive prediction cost (c₂), the threshold parameter (T), and the arrival rate (λ).

More on tables

This table presents the equations for SkipPredict, a scheduling policy that incorporates the cost of predictions. It shows separate equations for the expected mean response time of predicted short jobs and predicted long jobs under two different cost models: external cost model and server time cost model. The equations account for various factors including the arrival rate, service time of jobs, and prediction costs. The equations help to calculate the overall cost, considering both prediction cost and response time, enabling informed decision-making about when predictions are beneficial.

This table presents the formulas derived for the expected mean response time for predicted short jobs and predicted long jobs in both the external cost model and the server cost model for SkipPredict. It shows how the equations account for the prediction cost (c1 for cheap predictions, c2 for expensive predictions) and the load in the system. The equations are essential for analyzing the performance and cost-effectiveness of the SkipPredict algorithm.

Full paper#