TL;DR#

Deep neural networks (DNNs) are susceptible to adversarial attacks, and adversarial training (AT) is used to mitigate this issue. However, the resulting models often exhibit strong robustness for some classes (’easy’ classes) and weak robustness for others (‘hard’ classes), a phenomenon known as robust fairness. Existing works attempted to solve this issue by re-weighting the training samples, ignoring the information embedded in the labels that guide the model training process. This paper introduces an in-depth analysis of this phenomenon.

The paper proposes Anti-Bias Soft Label Distillation (ABSLD), a new method that addresses this issue. ABSLD operates within the knowledge distillation (KD) framework, modifying how the ’teacher’ model’s soft labels are used to train the ‘student’ model. ABSLD selectively sharpens soft labels for hard classes and smoothes them for easy classes. This is achieved by assigning different temperatures to the KD process for different classes, effectively controlling the class-wise smoothness of soft labels. The results of extensive experiments demonstrate that ABSLD outperforms other state-of-the-art methods in terms of both robustness and fairness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers working on adversarial robustness and fairness. It addresses a critical issue of imbalanced robustness across different classes, offering a novel approach that improves both robustness and fairness. The proposed method, ABSLD, provides a new avenue for enhancing model security and reliability, impacting various applications of deep learning. This research paves the way for more secure and equitable AI systems.

Visual Insights#

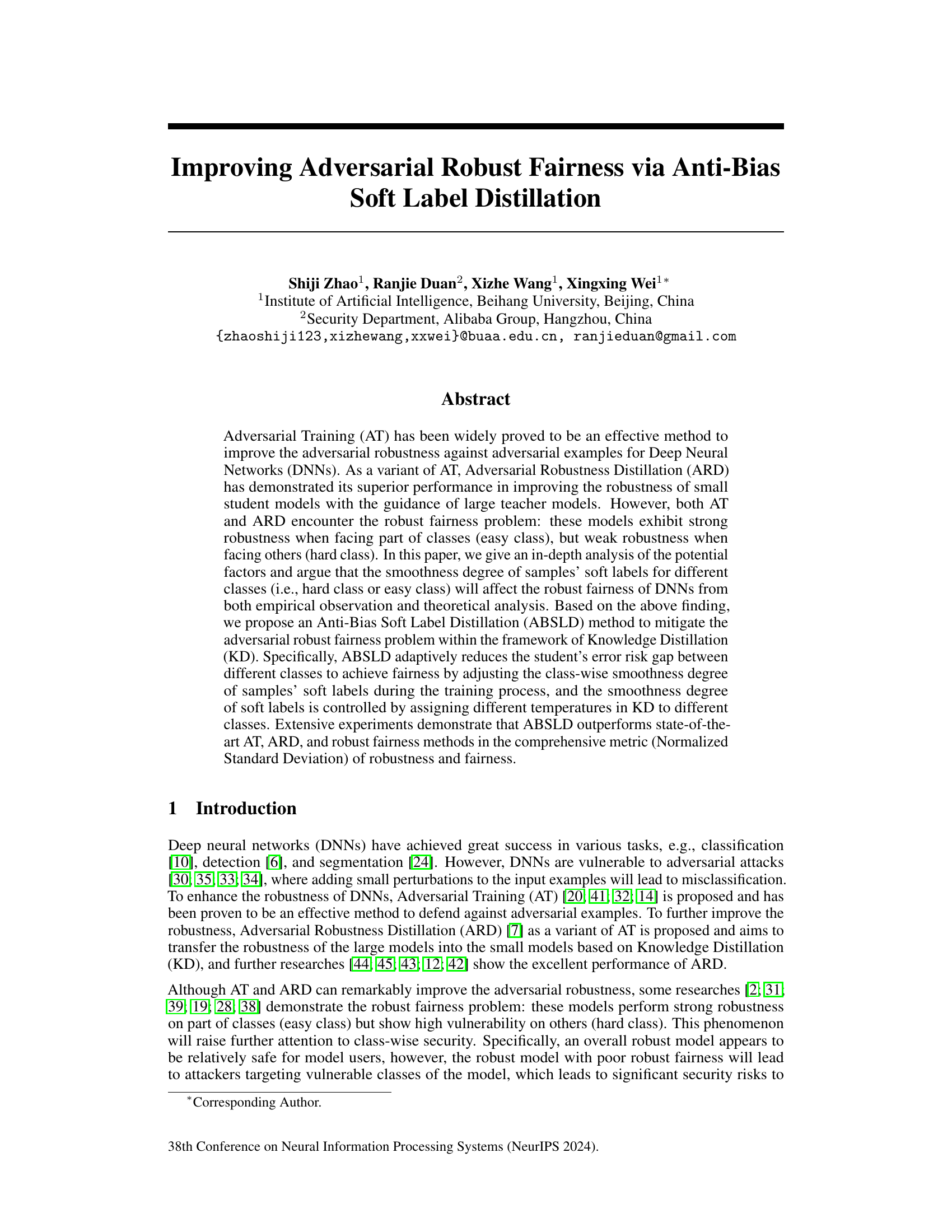

🔼 This figure compares two approaches to achieving fairness in adversarial training. The left side (a) shows sample-based fair adversarial training, where the model’s bias is addressed by re-weighting training samples based on their contribution to fairness. Samples from hard classes (those the model struggles to classify correctly) are weighted more heavily. The right side (b) illustrates the proposed label-based approach. It focuses on modifying the soft labels (probability distributions over classes) rather than sample weights. The smoothness of the soft labels is adjusted; harder classes receive sharper (less smooth) labels and easier classes receive smoother labels, influencing the model’s learning process and mitigating bias.

read the caption

Figure 1: The comparison between the sample-based fair adversarial training and our label-based fair adversarial training. For the former ideology in (a), the trained model's bias is avoided by re-weighting the sample's importance according to the different contribution to fairness. For the latter ideology in (b), the trained model's bias is avoided by re-temperating the smoothness degree of soft labels for different classes.

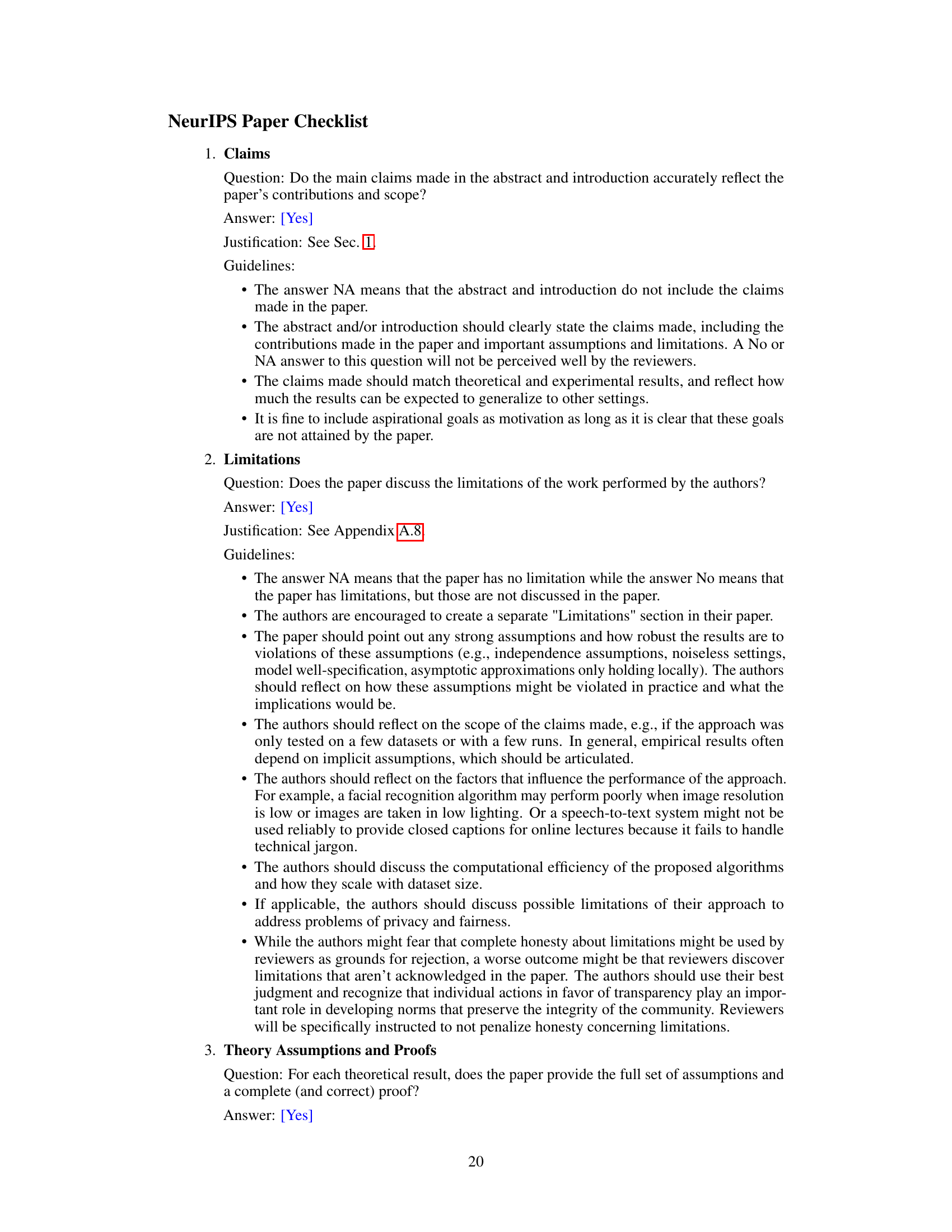

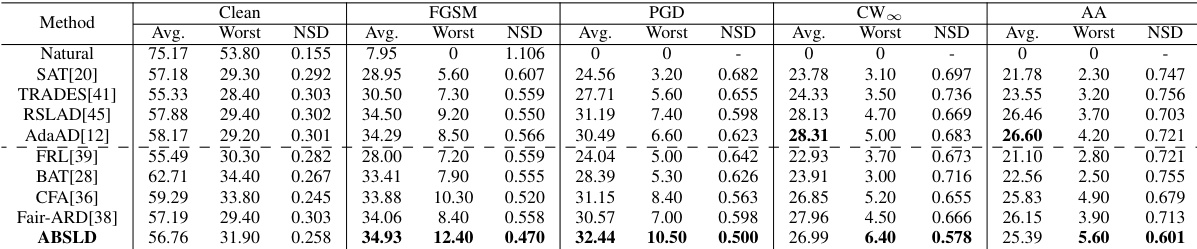

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different adversarial robustness methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset using ResNet-18 as the model. The metrics used are average robustness (higher is better), worst-case robustness (higher is better), and normalized standard deviation (NSD, lower is better). The NSD metric is used to assess robust fairness, where a lower value indicates better fairness. The results show the performance under various attacks (Clean, FGSM, PGD, CW∞, AA).

read the caption

Table 1: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on CIFAR-10 of ResNet-18.

In-depth insights#

Anti-Bias Distillation#

Anti-bias distillation, in the context of adversarial robustness, addresses the inherent fairness issue in existing training methods. Standard adversarial training often results in models robust against attacks for certain classes (easy classes) but vulnerable to others (hard classes), leading to biased security. Anti-bias distillation aims to mitigate this bias by manipulating the soft labels used during the knowledge distillation process. Instead of equally weighting all classes, it adjusts the “smoothness” of soft labels, providing sharper labels for hard classes and smoother ones for easy classes. This targeted approach ensures that the student model learns equally well from all classes, improving overall robustness while preventing the model from being unfairly vulnerable to specific classes. This technique directly tackles the optimization objective function, impacting the learning process and achieving greater fairness without significantly sacrificing overall robustness. It differs from sample-re-weighting strategies by focusing on label manipulation, offering a potentially more efficient and effective approach to enhance model fairness in adversarial settings. The key to this approach lies in adaptively adjusting the temperature of the soft labels for different classes, thereby influencing the learning intensity for each class. This adaptive temperature adjustment based on the student’s error risk is crucial, ensuring that harder classes receive sufficient attention and are not ignored during training. The method allows for improved robustness and fairness metrics, especially focusing on the worst-performing classes, making it a valuable technique in the development of robust and fair deep learning models.

Robust Fairness#

The concept of “Robust Fairness” in machine learning addresses the critical issue of algorithmic bias, particularly within the context of adversarial attacks. Standard adversarial training methods often improve overall model robustness but may exacerbate existing biases, leading to unfair outcomes for certain demographic groups. Robust fairness seeks to mitigate this by developing models that are both robust against adversarial examples and fair across different subgroups. This necessitates moving beyond simple accuracy metrics and incorporating fairness-aware evaluations during model development and training. Key challenges include identifying and quantifying fairness, defining appropriate fairness metrics for specific applications, and developing efficient training strategies that balance robustness and fairness without compromising accuracy. Research in this area often explores techniques such as re-weighting samples, adjusting loss functions, or using fairness-aware regularization methods. The long-term goal is to create models that are not only accurate and resilient to manipulation but also provide equitable outcomes for all users, regardless of their membership in a protected group.

Soft Label Impact#

The concept of ‘Soft Label Impact’ in a research paper would likely explore how the use of soft labels, as opposed to hard labels (one-hot encodings), affects various aspects of model training and performance. A key area would be robustness: soft labels, being probabilistic, might make the model more resilient to adversarial attacks or noisy data, leading to better generalization and decreased overfitting. Another crucial area would be fairness: the smoothing effect of soft labels might mitigate bias by reducing the emphasis on sharp class boundaries, potentially leading to more equitable treatment of different classes. The impact on training efficiency is also an important consideration, as soft labels can influence convergence speed and stability. Finally, the paper would likely explore the interpretability of models trained with soft labels, focusing on whether the inherent uncertainty represented by soft labels translates to better human understanding of the model’s decision-making process. The impact of different soft label generation methods and the sensitivity to temperature hyperparameters would also be investigated. Theoretical analysis supporting the empirical findings would likely involve information theory concepts and loss function analyses. Overall, a comprehensive study of ‘Soft Label Impact’ would reveal the multifaceted influence of soft labels on model behavior, providing valuable insights for improving machine learning model development.

ABSLD Framework#

The ABSLD framework presents a novel approach to enhancing adversarial robustness and fairness in deep neural networks. It leverages knowledge distillation, a technique where a smaller student network learns from a larger, more robust teacher network. However, unlike traditional knowledge distillation, ABSLD focuses on manipulating the smoothness of soft labels provided by the teacher. By adaptively adjusting the temperature parameter in the knowledge distillation process for different classes, ABSLD aims to reduce the disparity in robustness between easy and hard classes. This adaptive temperature adjustment is crucial, as it allows the model to learn more effectively from challenging samples without sacrificing overall performance. ABSLD’s core innovation lies in its class-wise treatment of soft label smoothness, addressing the root cause of adversarial robust fairness issues. Unlike other methods that focus on re-weighting samples or penalizing specific characteristics, ABSLD directly tackles the optimization process, leading to a model that is both robust and fair.

Future of Fairness#

The “Future of Fairness” in AI necessitates a multi-pronged approach. Robustness and fairness are intertwined, meaning improvements in one area should not compromise the other. Future research must move beyond simple metrics and explore contextual fairness, adapting to diverse datasets and user groups. Explainability will play a crucial role, allowing us to understand why AI systems make specific decisions and uncover hidden biases. Algorithmic transparency and auditable decision-making processes are crucial for building trust and accountability. Furthermore, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers, ethicists, social scientists, and policymakers is vital to navigate the complex societal implications of fairness in AI. Finally, ongoing monitoring and evaluation are essential to ensure that fairness remains a central consideration throughout the AI lifecycle, adapting to changing societal norms and emerging challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

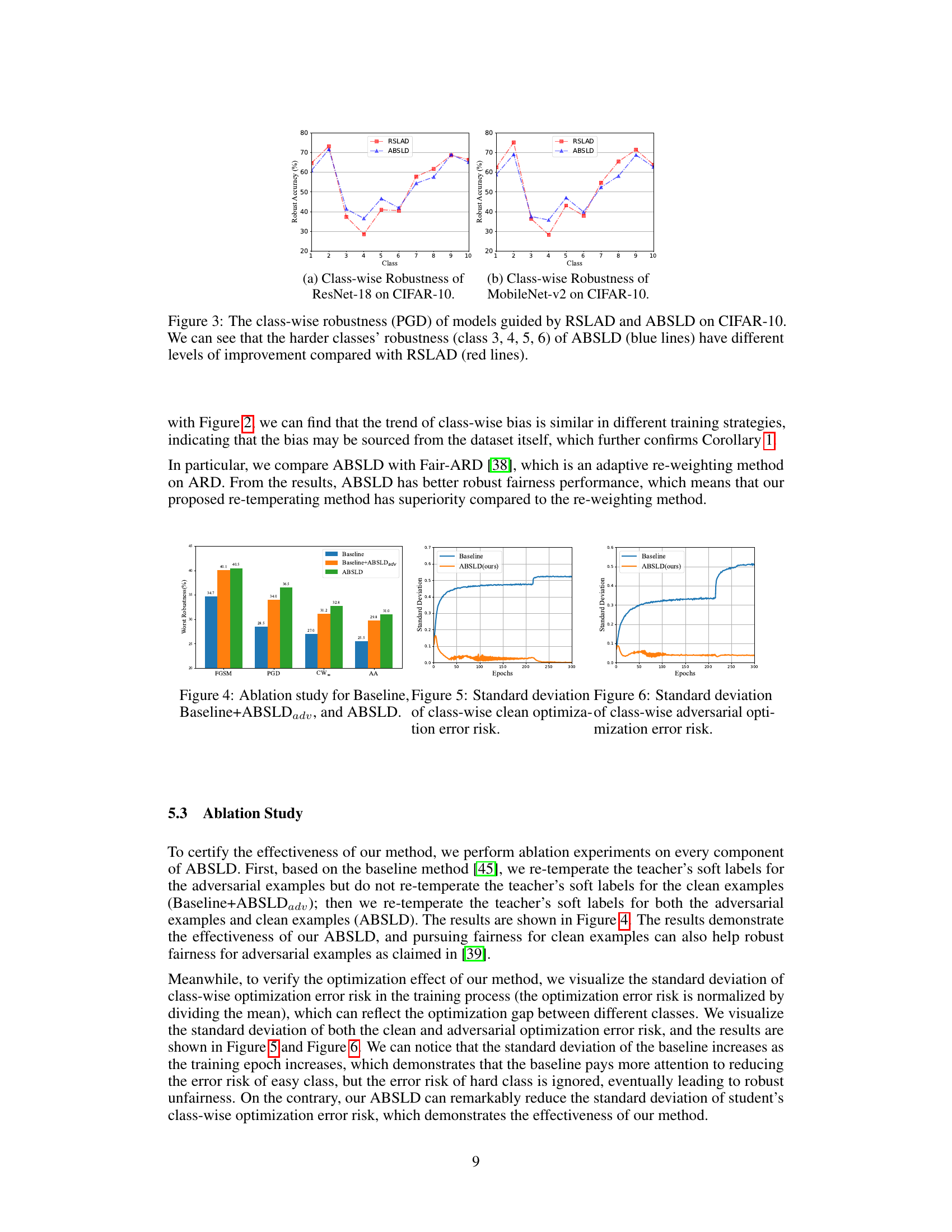

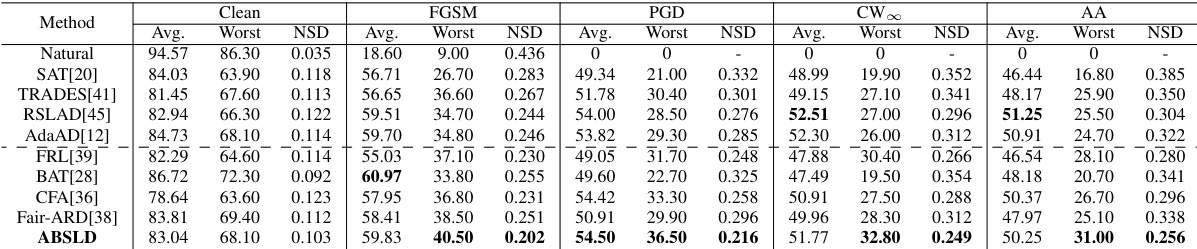

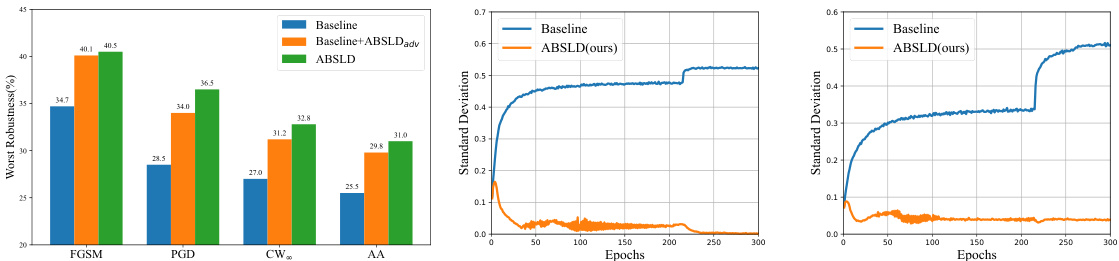

🔼 This figure compares the class-wise robustness of two different models (ResNet-18 and MobileNetV2) trained with soft labels having either the same or different smoothness degrees across classes. Using sharper soft labels for harder classes and smoother ones for easier classes improves the worst-case robustness without significantly affecting the average robustness, indicating that adjusting the smoothness of soft labels can help mitigate the robust fairness problem.

read the caption

Figure 2: The class-wise and average robustness of DNNs guided by soft labels with the same smoothness degree (SSD) and different smoothness degree (DSD) for different classes, respectively. For the soft labels with different smoothness degrees, we use sharper soft labels for hard classes and use smoother soft labels for easy classes. We select two DNNs (ResNet-18 and MobileNet-v2) trained by SAT [20] on CIFAR-10. The robust accuracy is evaluated based on PGD. The checkpoint is selected based on the best checkpoint of the highest mean value of all-class average robustness and the worst class robustness following [36]. We see that blue lines and red lines have similar average robustness, but the worst robustness of blue lines are remarkably improved compared with red lines.

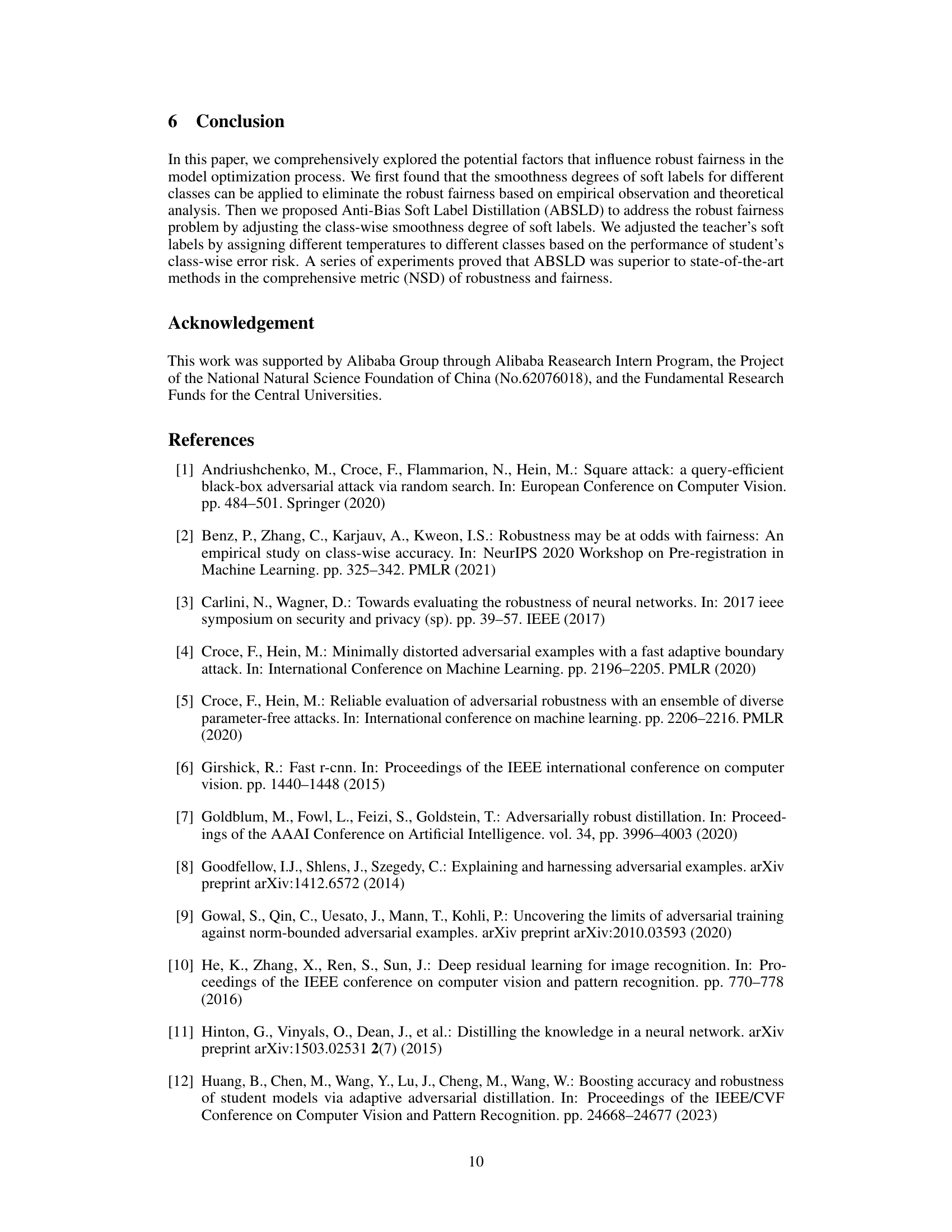

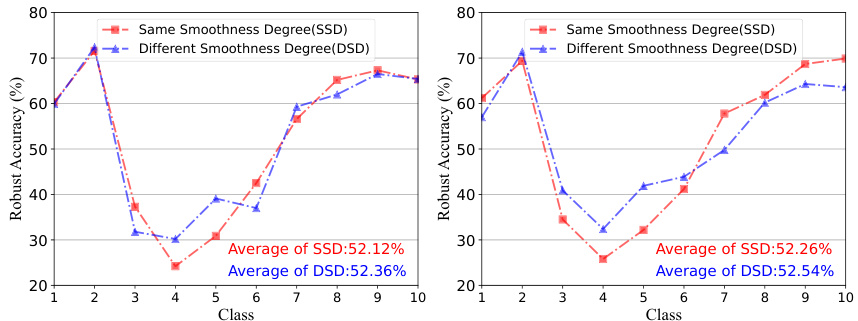

🔼 This figure shows the class-wise robustness of ResNet-18 and MobileNet-v2 models trained using RSLAD and ABSLD methods against PGD attacks on CIFAR-10 dataset. It compares the robustness of each class individually, highlighting that ABSLD significantly improves the robustness of harder classes (classes 3-6) compared to RSLAD.

read the caption

Figure 3: The class-wise robustness (PGD) of models guided by RSLAD and ABSLD on CIFAR-10. We can see that the harder classes' robustness (class 3, 4, 5, 6) of ABSLD (blue lines) have different levels of improvement compared with RSLAD (red lines).

🔼 This figure compares the class-wise robustness of ResNet-18 and MobileNet-v2 models trained using RSLAD and ABSLD against PGD attacks. It shows that ABSLD improves the robustness of harder classes more than RSLAD, indicating its effectiveness in addressing the robust fairness problem. The x-axis represents the class index and the y-axis represents the robust accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 3: The class-wise robustness (PGD) of models guided by RSLAD and ABSLD on CIFAR-10. We can see that the harder classes' robustness (class 3, 4, 5, 6) of ABSLD (blue lines) have different levels of improvement compared with RSLAD (red lines).

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of different adversarial training methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset using ResNet-18 as the model. It compares the average robustness, the worst-case robustness (robustness on the hardest class), and the normalized standard deviation (NSD) of robustness across classes. Lower NSD values indicate better fairness. The metrics are evaluated under four different attacks: FGSM, PGD, CW∞, and Auto-Attack (AA).

read the caption

Table 1: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on CIFAR-10 of ResNet-18.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using the ResNet-18 model. It compares various adversarial robustness methods (including the proposed ABSLD) across multiple attack types (FGSM, PGD, CW∞, and AA). The metrics used are average robustness (higher is better), worst-case robustness (higher is better), and normalized standard deviation (NSD, lower is better, reflecting fairness).

read the caption

Table 1: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on CIFAR-10 of ResNet-18.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different adversarial training and robustness methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset using ResNet-18 as the model. The metrics used for comparison are average robustness (higher is better), worst-case robustness (higher is better), and normalized standard deviation (NSD, lower is better). The NSD metric is specifically designed to capture the fairness of the model’s robustness across different classes. Lower values of NSD indicate better fairness. The table shows that ABSLD outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on CIFAR-10 of ResNet-18.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the Tiny-ImageNet dataset using the PreActResNet-18 model. The metrics evaluated include average robustness (higher is better), worst-case robustness (higher is better), and normalized standard deviation (NSD, lower is better). The average robustness represents the overall performance of the model across all classes. The worst-case robustness focuses on the model’s performance on the most vulnerable class. The NSD measures the fairness of the model, indicating whether the model is equally robust across all classes. The table compares three different models: RSLAD, CFA, and ABSLD (the proposed method).

read the caption

Table 5: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on Tiny-ImageNet of PreActResNet-18.

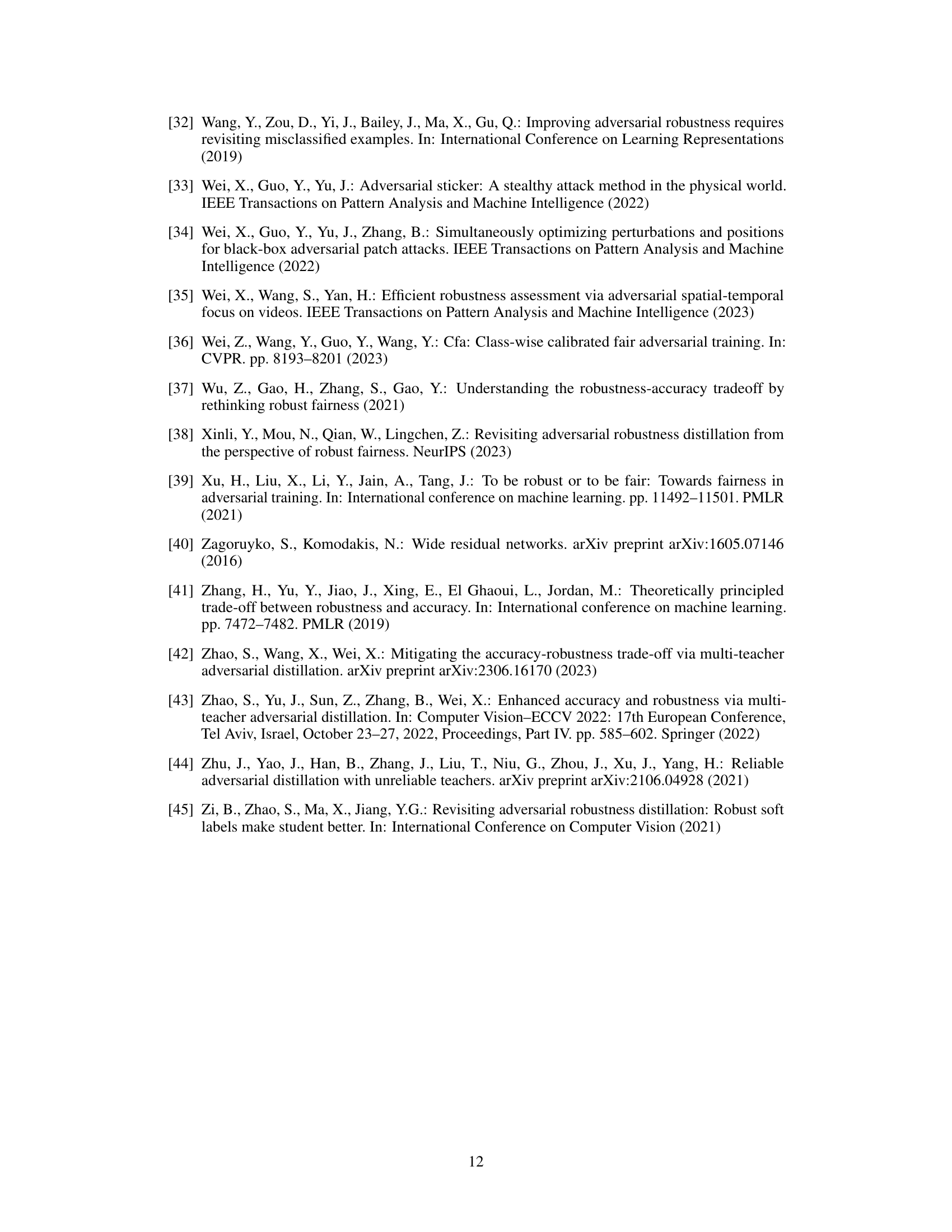

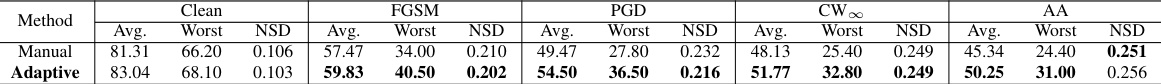

🔼 This table presents the results of average robustness, worst-case robustness, and normalized standard deviation (NSD) on the CIFAR-10 dataset using ResNet-18. It compares the performance of two methods: Manual and Adaptive. The Manual method uses a static temperature for different classes, while the Adaptive method uses a self-adaptive temperature adjustment strategy. Higher average and worst robustness values are better, while a lower NSD value indicates better fairness.

read the caption

Table 6: Result in average robustness(%) (Avg.↑), worst robustness(%) (Worst↑), and normalized standard deviation (NSD↓) on CIFAR-10 of ResNet-18.

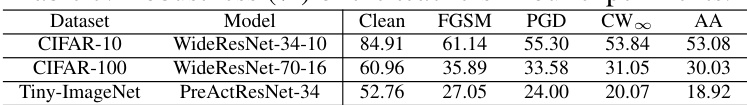

🔼 This table presents the robustness of the teacher models used in the ABSLD experiments. The robustness is measured under various attacks (clean, FGSM, PGD, CW∞, AA) for three different datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and Tiny-ImageNet. Each dataset uses a different teacher model architecture tailored for optimal performance on that dataset.

read the caption

Table 7: Robustness (%) of the teachers in our experiments.

Full paper#