↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Accurately predicting protein fitness is crucial for designing novel functional proteins, but existing methods have limitations. Previous attempts to combine sequence and structural information have yielded only incremental improvements. Also, surface topology, which influences protein functionality, was mostly overlooked.

This paper introduces the Sequence-Structure-Surface Fitness (S3F) model, a novel approach that integrates protein features at multiple scales: protein sequences (using a language model), protein backbone structures (using Geometric Vector Perceptrons), and detailed surface topology. S3F achieves state-of-the-art results on the ProteinGym benchmark, outperforming previous methods, and provides insights into the determinants of protein function. Its efficiency and adaptability makes S3F a valuable tool for future protein design and engineering research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in protein design and representation learning. It introduces a novel multi-scale model (S3F) that significantly improves protein fitness prediction, surpassing existing methods and offering a more efficient approach. The findings open new avenues for understanding protein function and engineering proteins with desired characteristics. Its readily adaptable nature also makes it beneficial for researchers working with different protein language models.

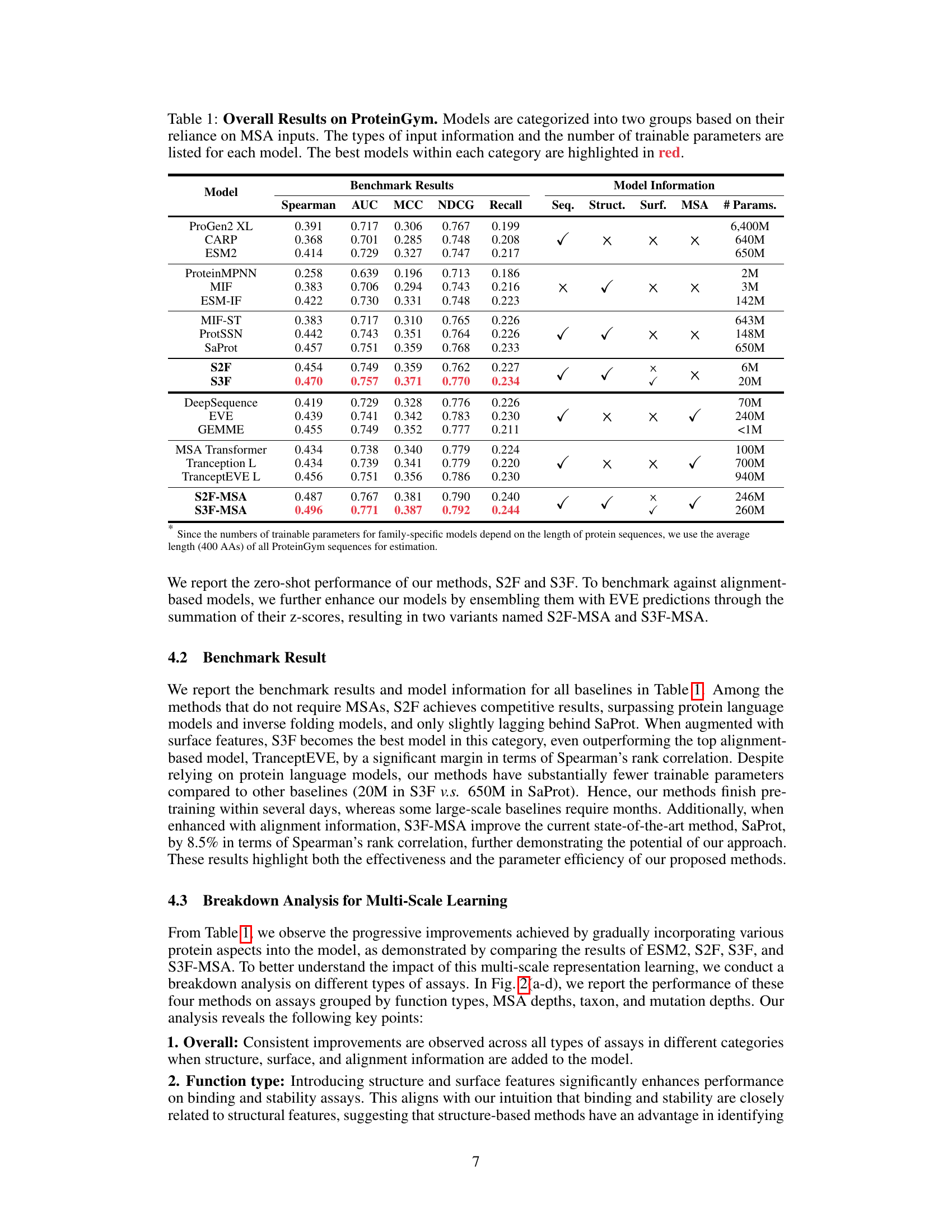

Visual Insights#

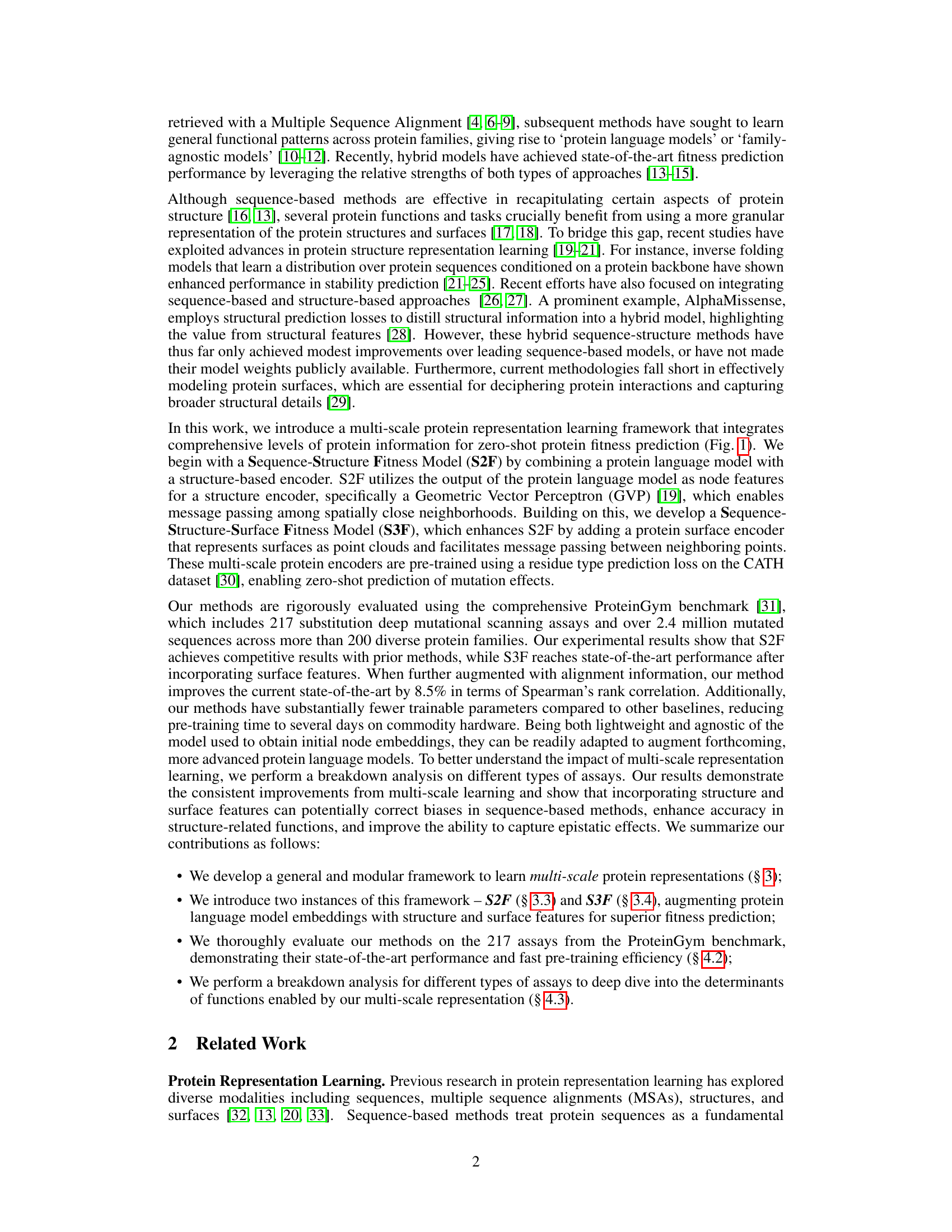

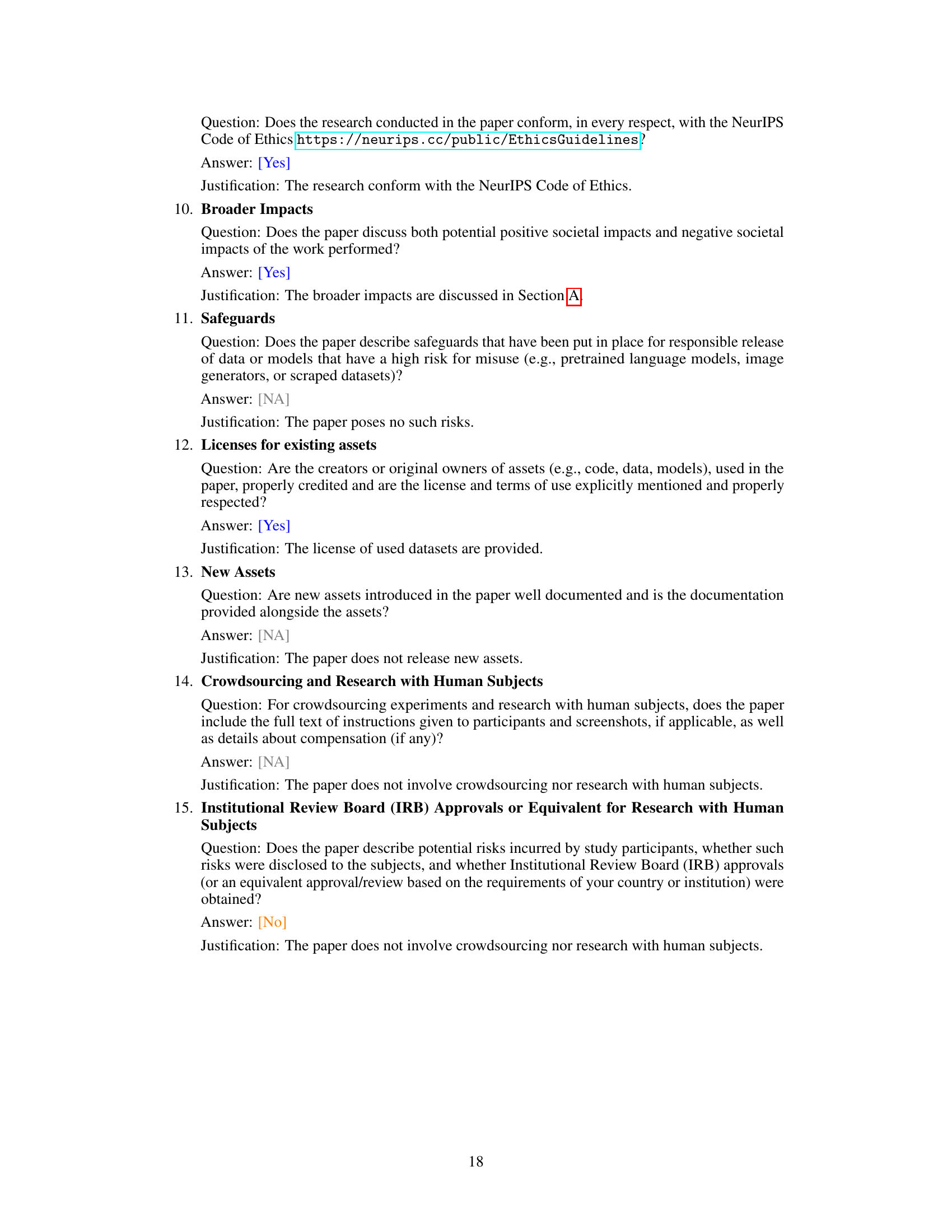

This figure illustrates the multi-scale pre-training and inference frameworks used for protein fitness prediction. During pre-training, protein sequences and structures are sampled from a database, with 15% of residue types randomly masked. These sequences are fed into a protein language model (ESM-2-650M). The resulting residue representations are then used to initialize node features in structure and surface encoders. Through message passing on structure and surface graphs, the methods S2F (Sequence-Structure Fitness Model) and S3F (Sequence-Structure-Surface Fitness Model) accurately predict the residue type distribution at each masked position. This distribution is subsequently used for mutation preferences in downstream fitness prediction tasks.

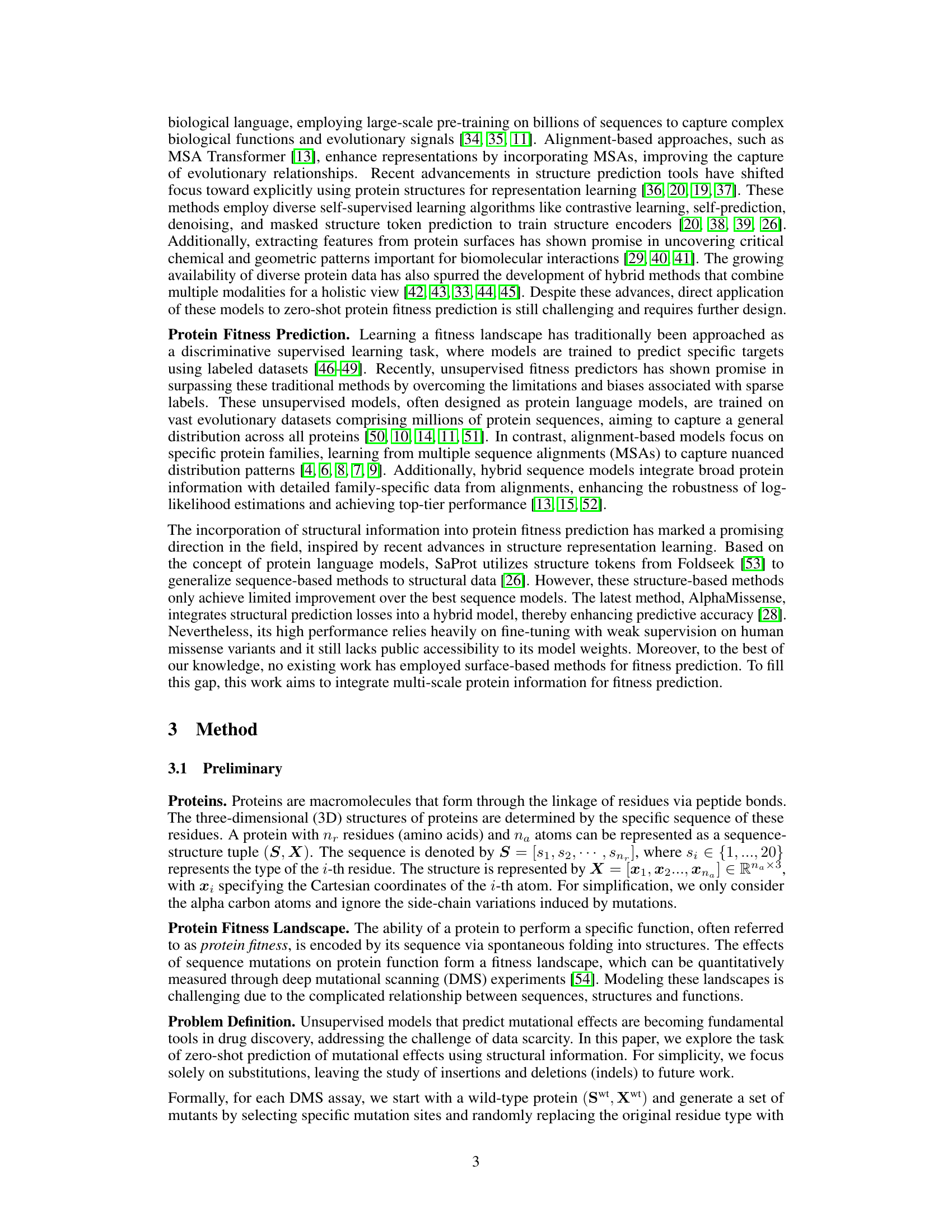

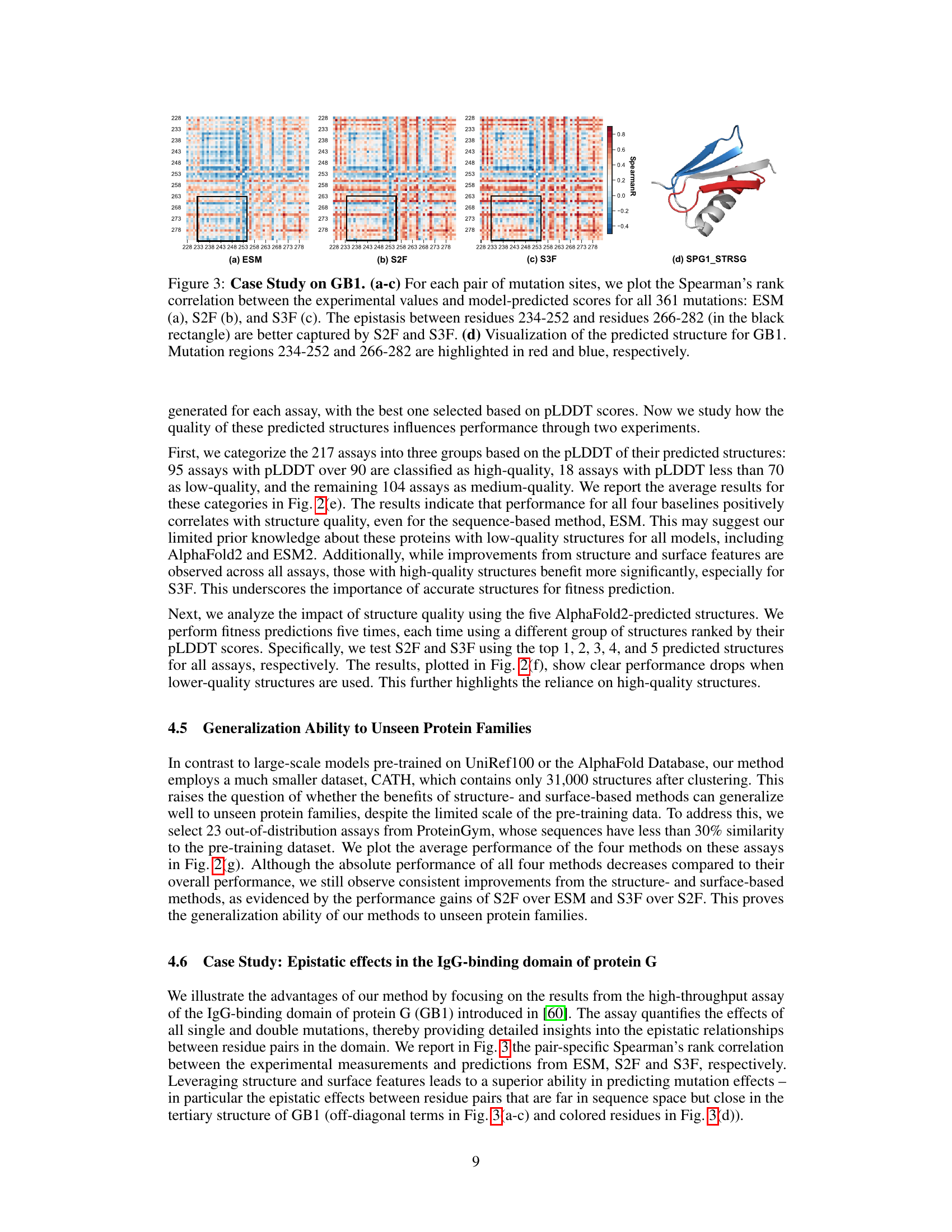

This table presents the overall performance of various protein fitness prediction models on the ProteinGym benchmark. Models are grouped by their use of Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs). For each model, the table shows the Spearman correlation, AUC, MCC, NDCG, and Recall metrics. The number of trainable parameters and the types of input data (sequence, structure, surface, MSA) used by each model are also listed. The best-performing models in each group are highlighted in red.

In-depth insights#

Multi-Scale Fitness#

The concept of “Multi-Scale Fitness” in protein design suggests that fitness is not solely determined by a single level of analysis (e.g., sequence alone), but rather emerges from an interplay of features across multiple scales. Sequence-based methods, while valuable, often miss crucial context provided by 3D structure and surface properties. A multi-scale approach therefore integrates information from various levels, including sequence, backbone structure, and surface topology to create a holistic representation of protein fitness. This holistic perspective helps capture crucial interactions with the environment, binding partners, and internal dynamics of the protein that are not apparent when considering individual aspects in isolation. Higher resolution data like surface properties, for example, could reveal subtle interactions crucial for protein function, and would thus need to be included in a comprehensive fitness evaluation. Successfully integrating these various scales of information will improve predictive accuracy and facilitate better protein design.

S3F Model Details#

The hypothetical ‘S3F Model Details’ section would delve into the architecture and functionality of the Sequence-Structure-Surface Fitness (S3F) model. It would likely begin by describing the multimodal nature of S3F, explaining how it integrates sequence information (perhaps from a protein language model like ESM), structural information (potentially from GVPs processing backbone coordinates), and surface topology data (likely derived from point cloud representations). A key aspect would be detailing the interaction between these modalities, describing how the model fuses these different data types to generate a comprehensive protein representation. The section should discuss the specific neural network layers used—encoders for each modality, possibly attention mechanisms for integration, and the final prediction layer that outputs a fitness score. Furthermore, training procedures, including loss functions (likely related to fitness prediction accuracy), optimization strategies, and the use of any pre-training datasets, would be elucidated. Finally, the section should provide specifics on how the model’s parameters and hyperparameters were selected and tuned, highlighting techniques such as cross-validation or hyperparameter optimization. In summary, the ‘S3F Model Details’ would present a rigorous and exhaustive explanation of the model’s design and training for researchers to understand and potentially replicate the results.

Benchmark Results#

The Benchmark Results section would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed model’s performance against existing state-of-the-art methods. This would involve reporting key metrics such as Spearman’s rank correlation, AUC, MCC, NDCG, and Top-10% recall. A table clearly showing these metrics for both the new model and the baselines is crucial for easy comparison. Crucially, the choice of benchmarks should be justified, highlighting the relevance and comprehensiveness of the selected datasets. The analysis shouldn’t just present raw numbers but should also include a discussion of statistical significance, perhaps through p-values or confidence intervals. Furthermore, error bars in any visualization would enhance clarity. A deeper analysis focusing on specific subsets of the data or particular aspects of the fitness landscape would add further value, perhaps revealing where the model excels or underperforms. Finally, a discussion of the computational cost and efficiency of the model compared to baselines would provide a holistic view.

Limitations#

The research, while groundbreaking in achieving state-of-the-art results using a lightweight model, acknowledges key limitations. Data limitations are a primary concern; the model’s pre-training on a relatively small subset of experimentally determined protein structures might hinder its generalizability to unseen protein families. The study also notes simplifying assumptions made during model design, such as ignoring side-chain information and assuming backbone structures remain static post-mutation. These assumptions, while necessary for computational efficiency, could limit the model’s accuracy and applicability. Finally, the scope of the model is currently restricted to substitution effects, excluding insertions and deletions, thus requiring future work to enhance its predictive capabilities for a broader range of mutations.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the accuracy and generalizability of fitness prediction is paramount, perhaps by incorporating more diverse and extensive datasets encompassing a wider range of protein families and functional annotations. Advanced representation learning techniques, beyond those presented, like incorporating evolutionary information or utilizing graph neural networks to model protein interactions more comprehensively, warrant investigation. Furthermore, exploring the impact of different mutation types (insertions, deletions) and integrating this with existing substitution models would enhance model scope and applicability. Finally, developing more robust and efficient methods for handling uncertainty, particularly when dealing with AlphaFold2 structural predictions of variable quality, remains crucial for reliable fitness landscape estimations. This could involve incorporating confidence scores from structure prediction into the model itself.

More visual insights#

More on figures

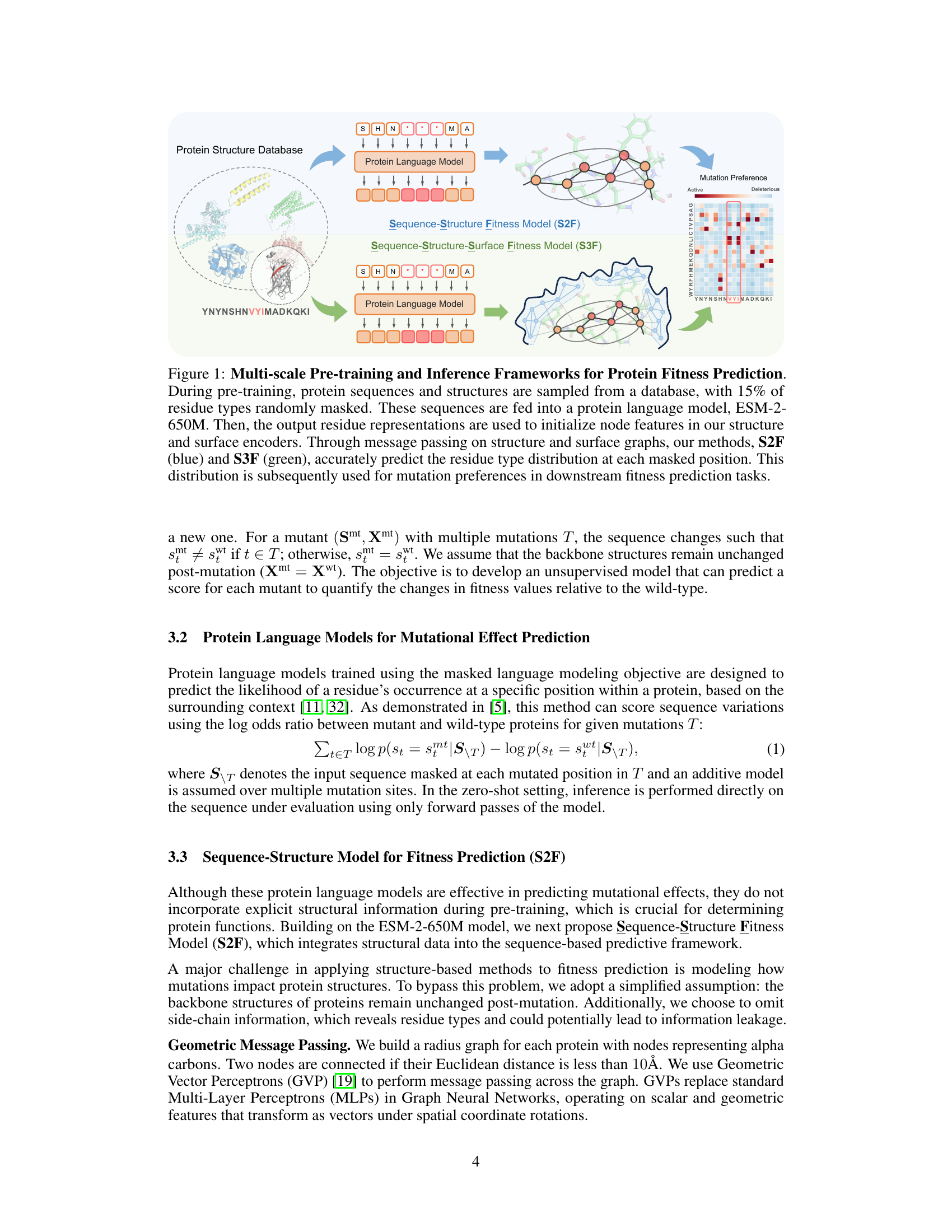

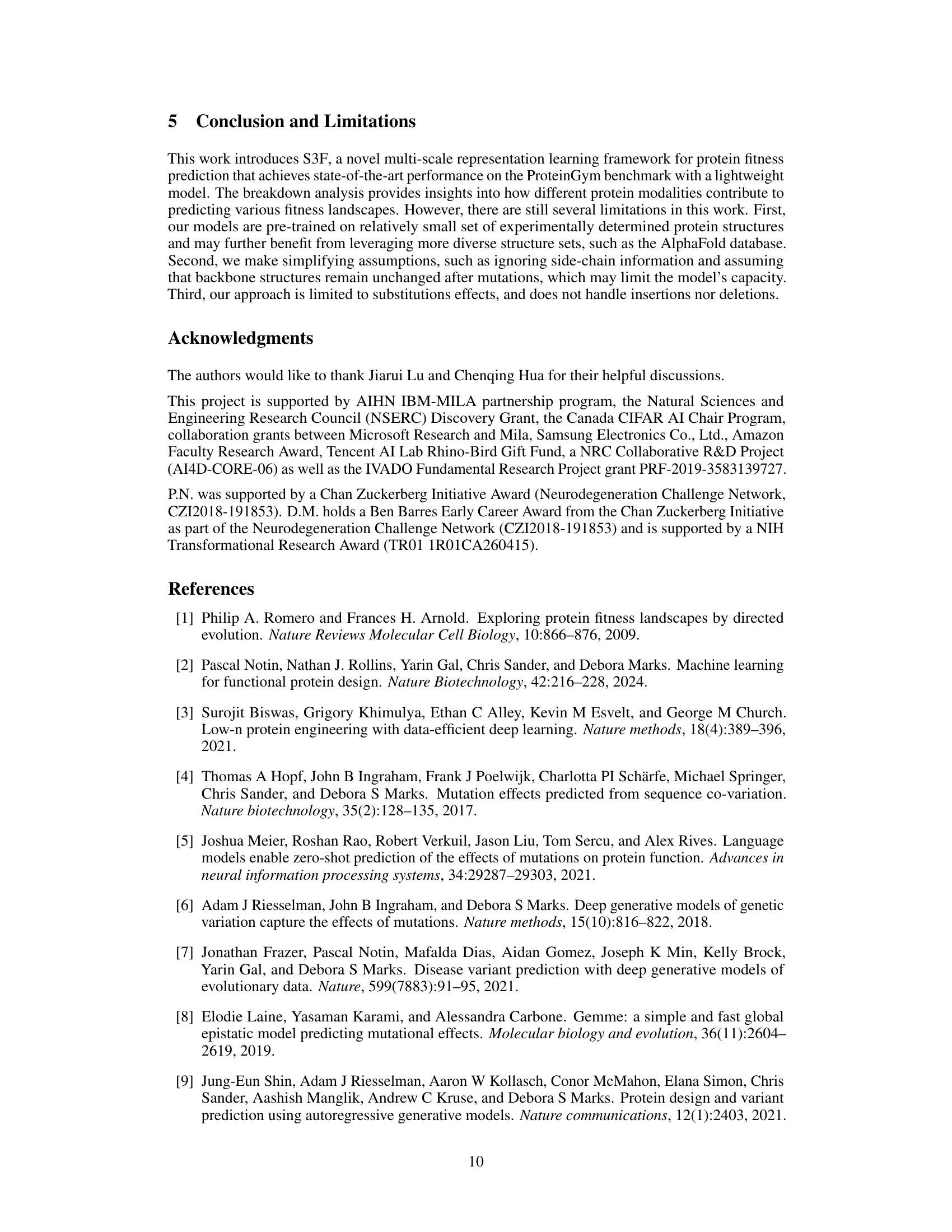

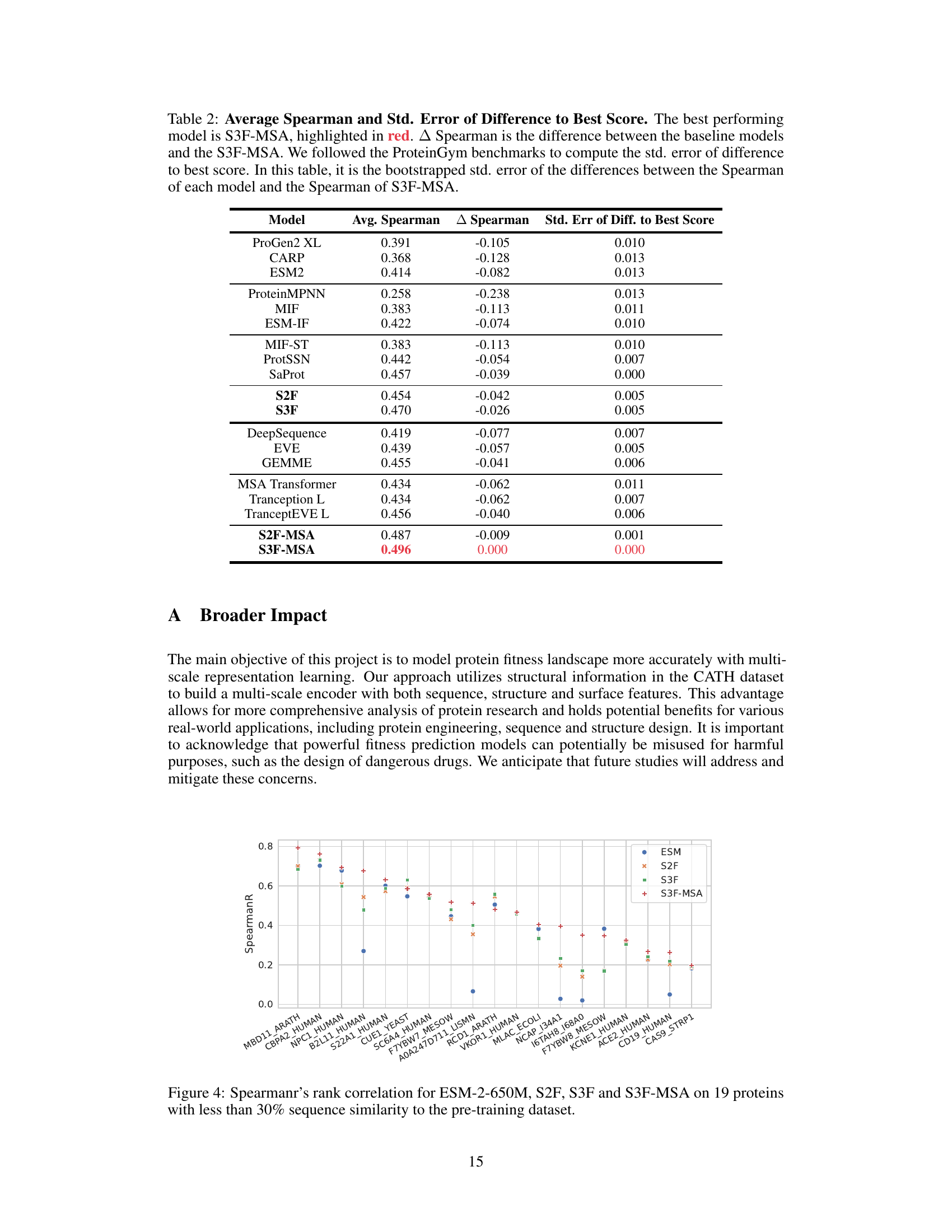

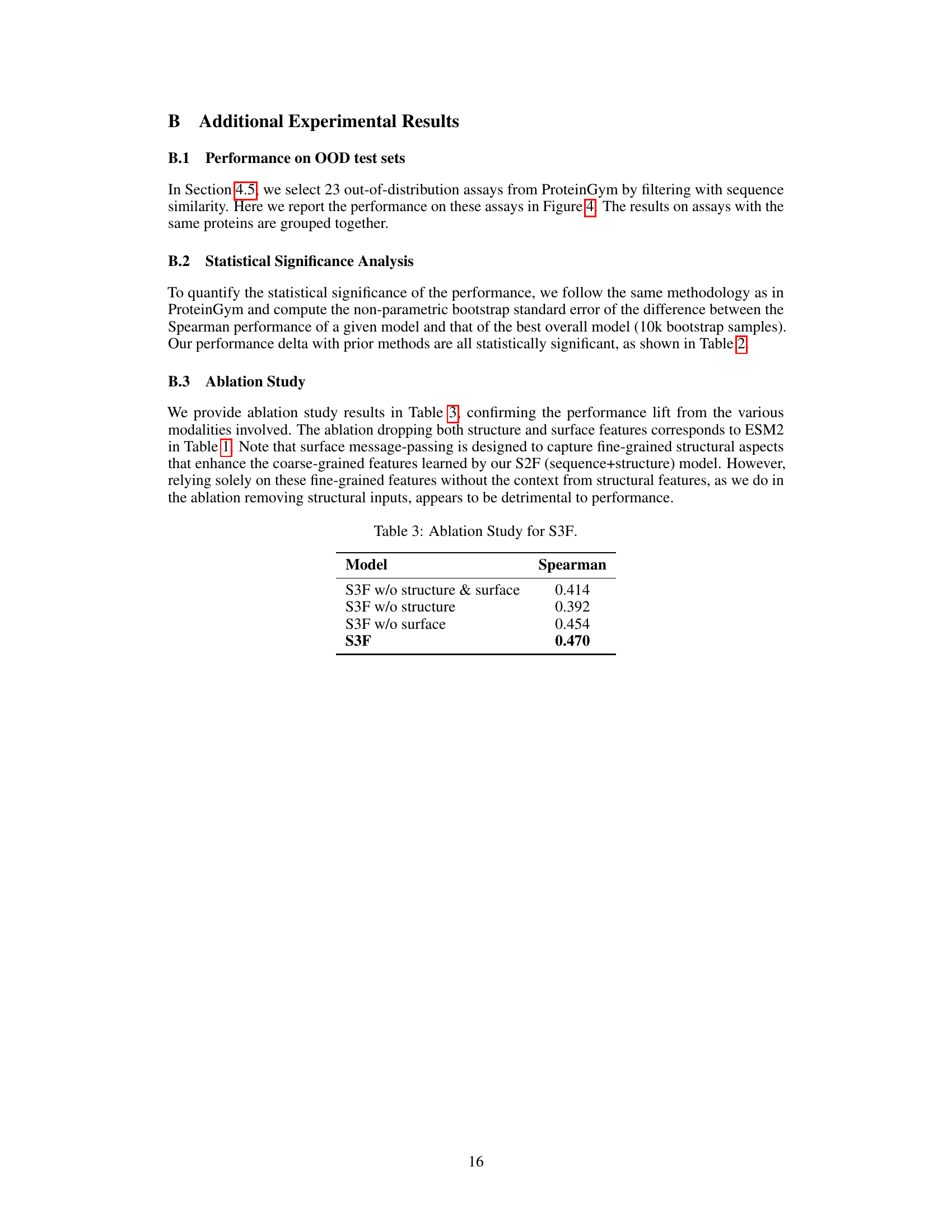

This figure presents a breakdown analysis of the performance of four different methods (ESM-2-650M, S2F, S3F, and S3F-MSA) on protein fitness prediction, categorized by various factors such as function type, MSA depth, taxon, mutation depth, and structure quality. It demonstrates how incorporating structural and surface information progressively improves prediction accuracy, particularly for assays with high-quality structures and those with complex epistatic interactions.

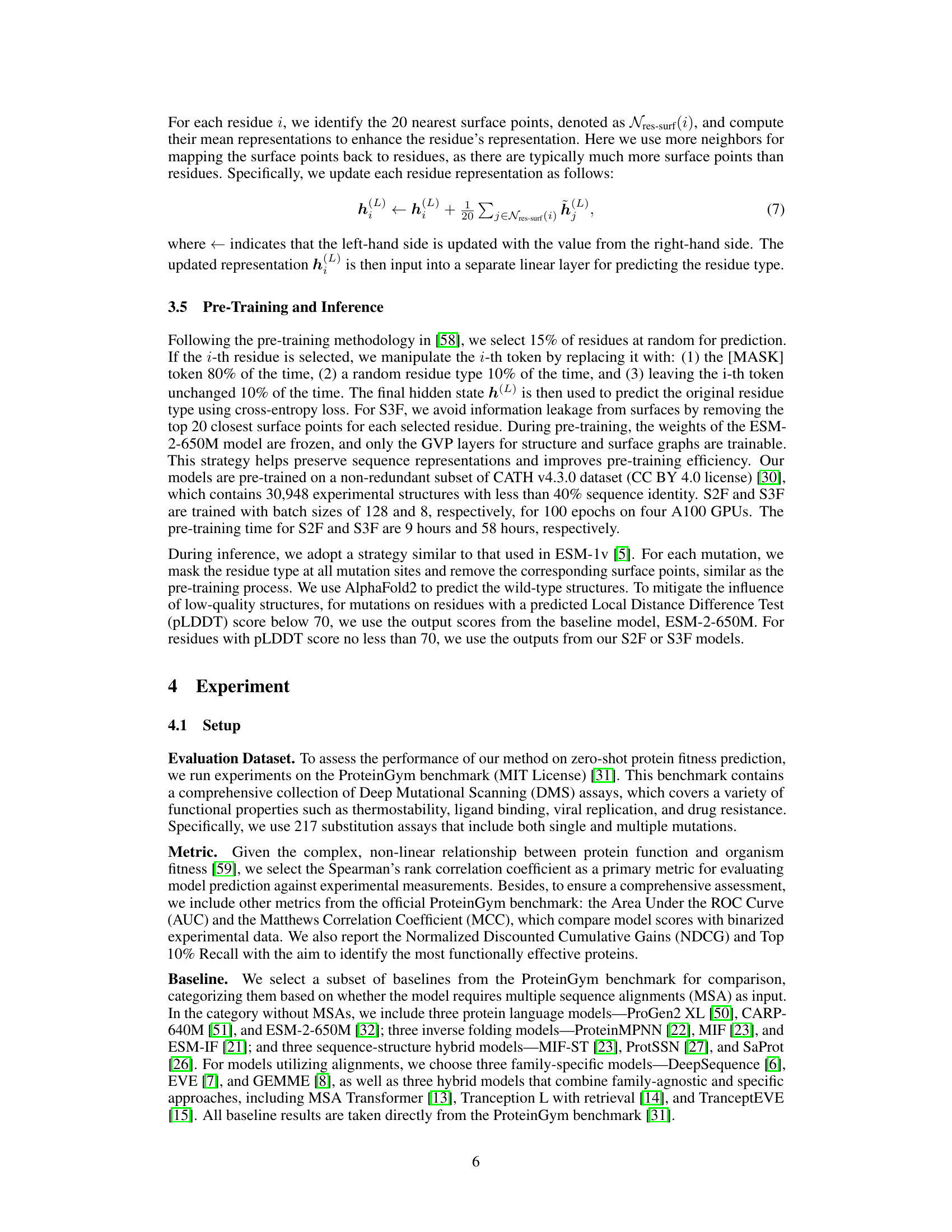

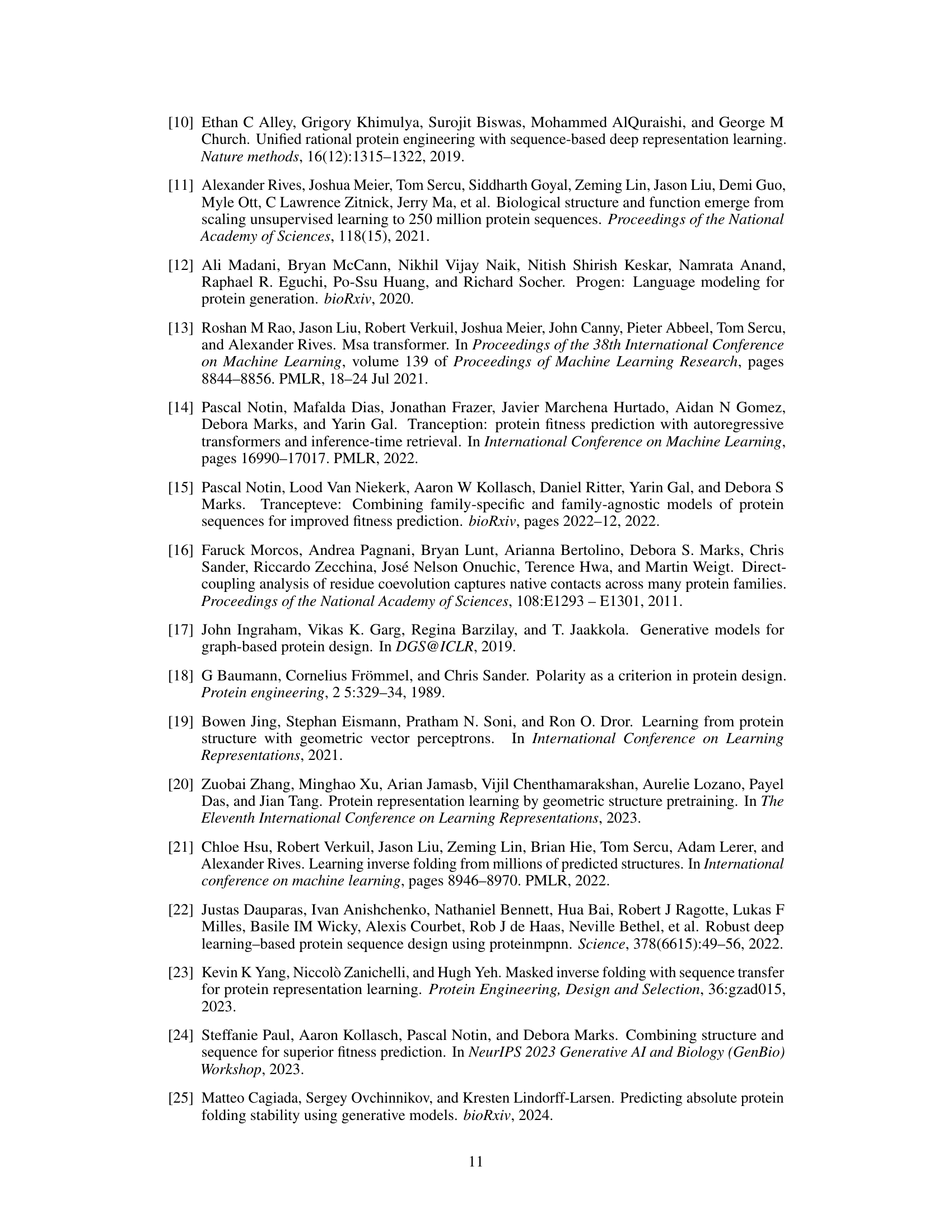

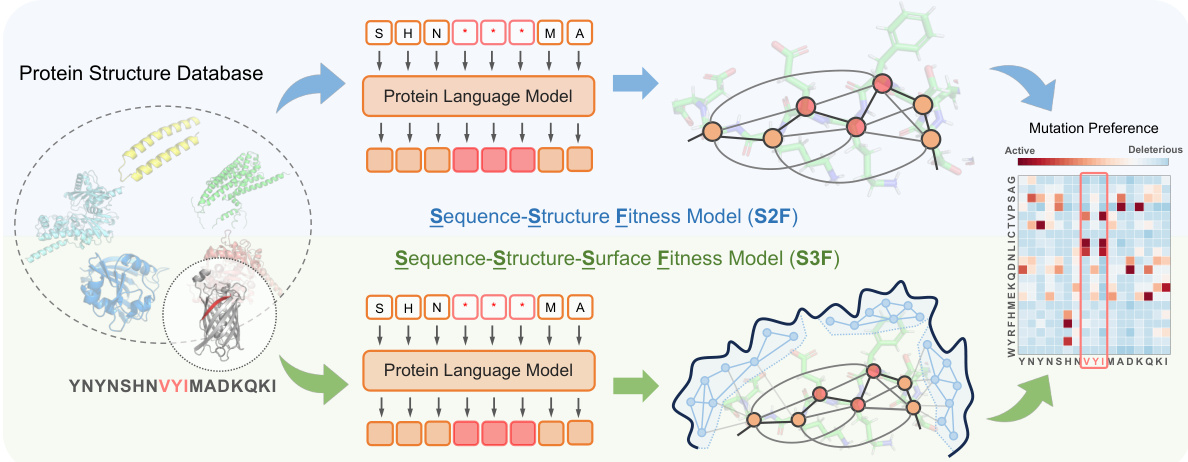

This figure presents a case study on the IgG-binding domain of protein G (GB1). It shows heatmaps comparing experimental and predicted mutation effects (Spearman’s rank correlation) for different models: ESM, S2F, and S3F. The heatmaps highlight epistatic interactions, particularly between residues 234-252 and 266-282, which are better captured by S2F and S3F. A 3D structure visualization of GB1 is also included, highlighting the spatial relationship between these residue regions.

This figure presents a breakdown analysis of the performance of four different methods (ESM-2-650M, S2F, S3F, and S3F-MSA) on various protein fitness prediction assays. Subplots (a-d) show performance categorized by function type, MSA depth, taxon, and mutation depth, respectively. Subplots (e-f) analyze the impact of protein structure quality on prediction accuracy. Subplot (g) compares performance on in-distribution and out-of-distribution assays. The results illustrate the incremental improvements achieved by incorporating structural and surface features into the model, as well as its robustness across diverse protein families and data characteristics.

More on tables

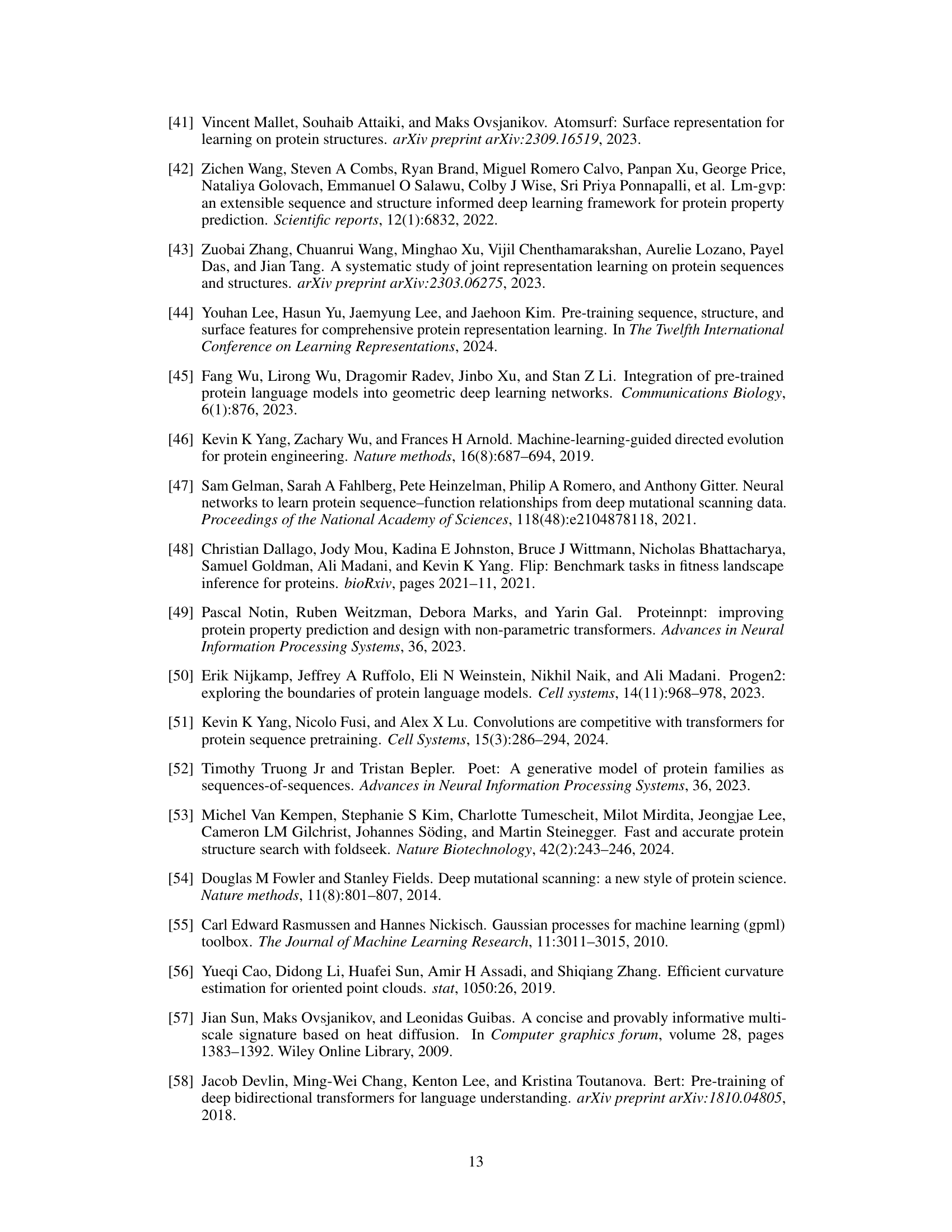

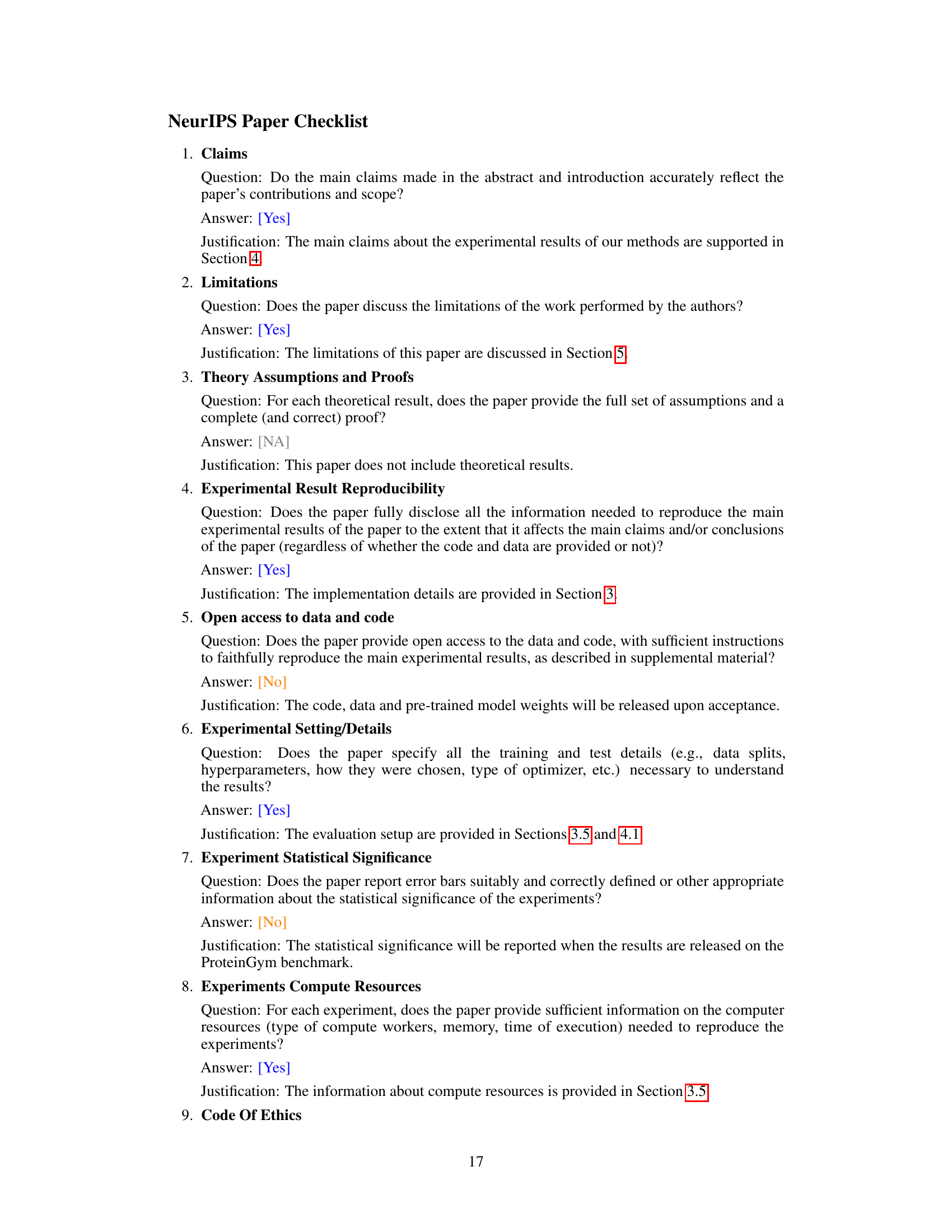

This table presents the average Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and their standard errors for various models on a protein fitness prediction task. It compares different models’ performances against the best-performing model (S3F-MSA), showing the differences and statistical significance.

This table presents the average Spearman correlation and standard error of the difference from the best-performing model (S3F-MSA) for various protein fitness prediction models. It compares the performance of different models against the top-performing model to highlight relative performance differences.

Full paper#