↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications need interpretable models that allow human users to intervene and influence the prediction process. However, achieving this with complex, black-box models poses significant challenges. Existing methods, such as concept bottleneck models, often require extensive data annotation or limit intervention capabilities. This paper tackles these challenges by proposing a novel approach for making black-box models more intervenable. The core problem is that black box models are not designed for interpretability, and methods to make them interpretable often require significant extra labeled data, or only work in limited contexts.

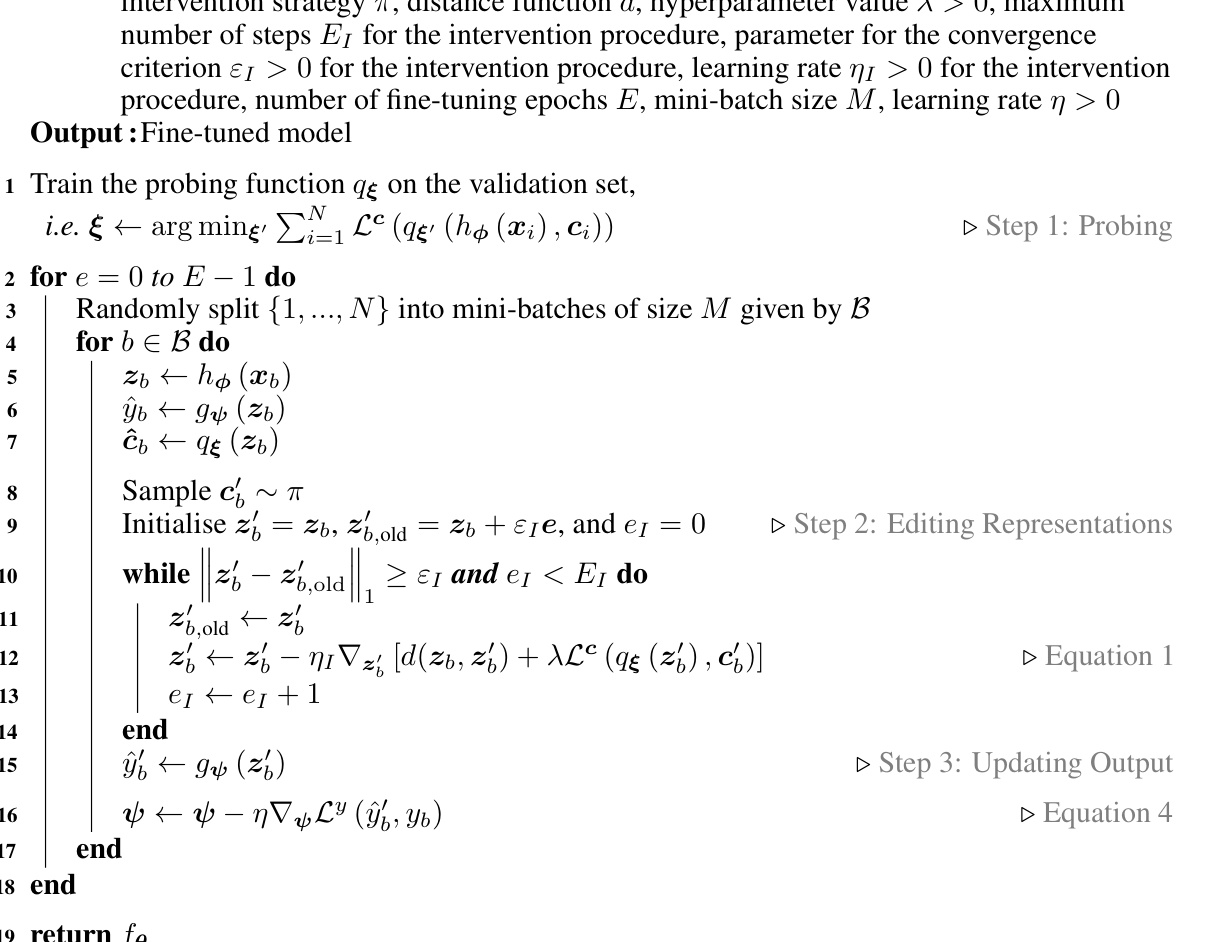

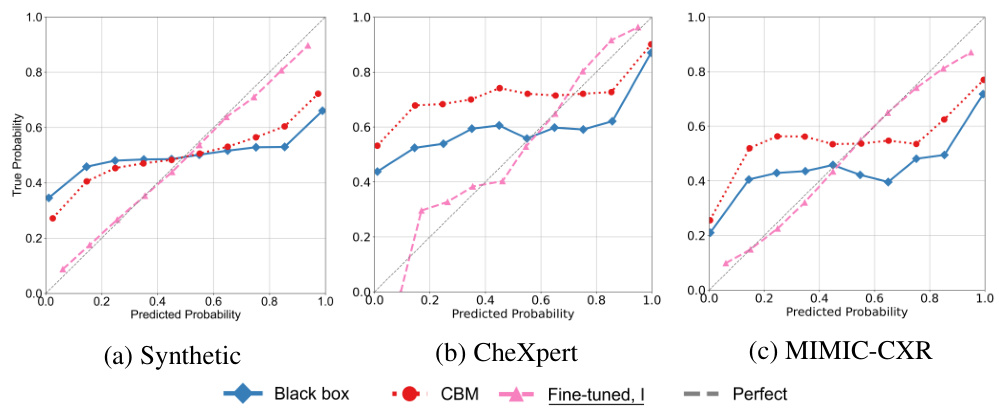

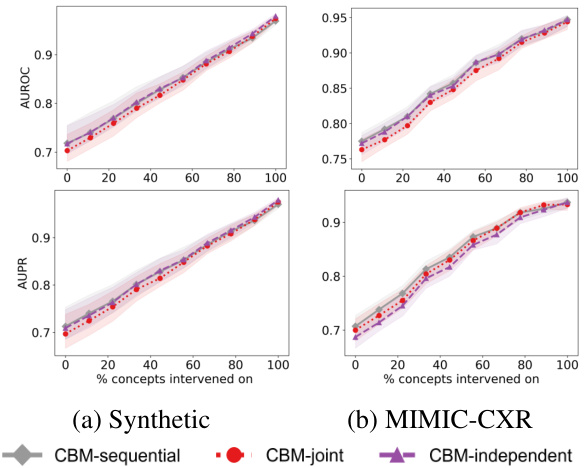

The authors introduce a simple procedure for performing instance-specific interventions directly on pre-trained black-box models using a small validation set with concept labels. The method involves training a ‘probe’ to map the model’s internal representations to concept values. Then, the method edits these representations to align with the desired concept values, resulting in an updated prediction. The effectiveness of this approach is evaluated using a new formal measure of intervenability. Importantly, the paper shows how fine-tuning the black-box model, using intervenability as a loss, improves intervention effectiveness and often yields better-calibrated predictions. This is empirically demonstrated on various benchmarks, including chest X-ray classification, showcasing the practical utility of the proposed approach. The methods prove effective even when using vision-language-model based concept annotations instead of human-annotated ones.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in interpretable machine learning and related fields because it introduces a novel method for making black-box models more intervenable, addresses the limitations of existing concept bottleneck models, and provides a formal measure of intervenability. This opens new avenues for research, particularly in high-stakes decision-making applications where human-model interaction is critical, such as healthcare. The findings challenge existing assumptions about the interpretability of black-box models and suggest new directions for improving their explainability and usability.

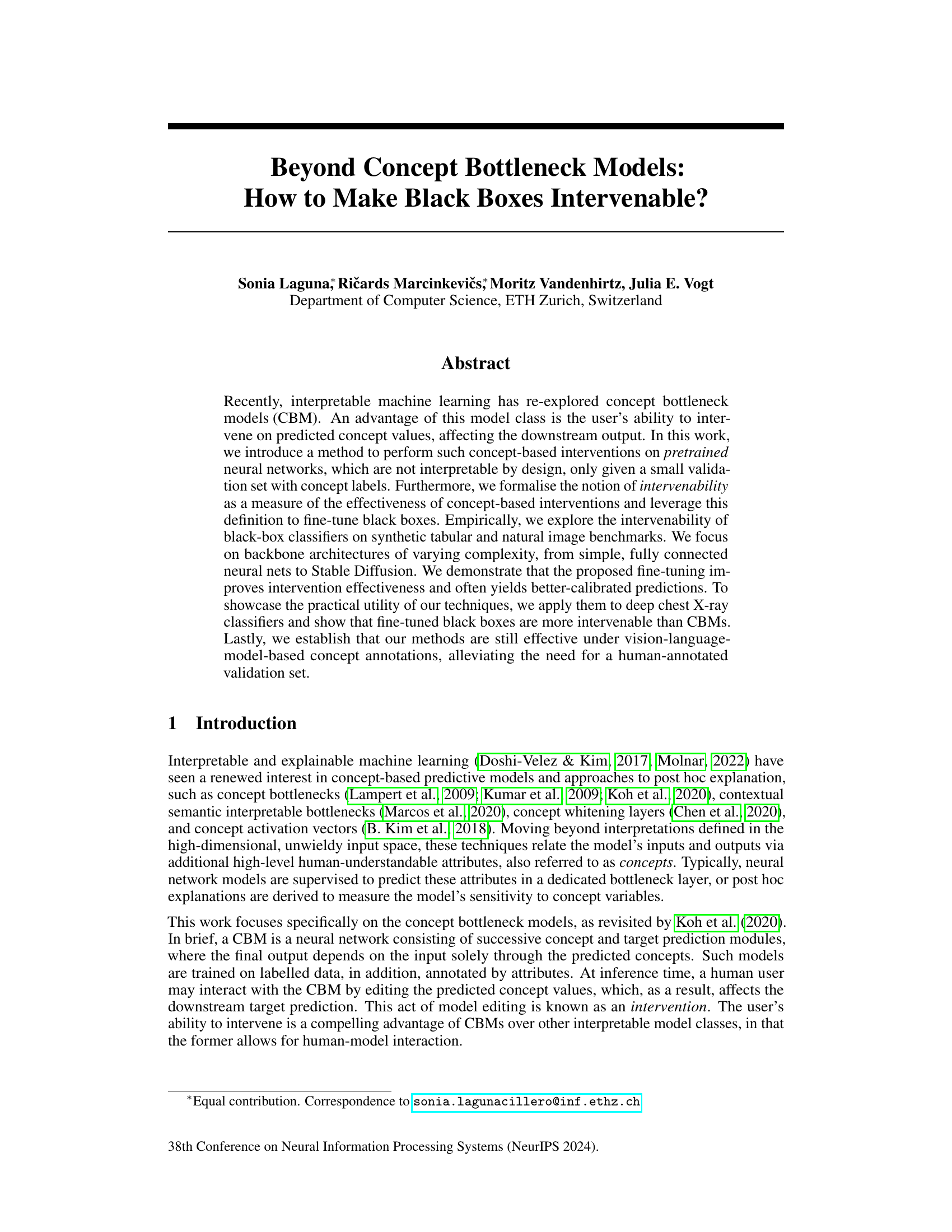

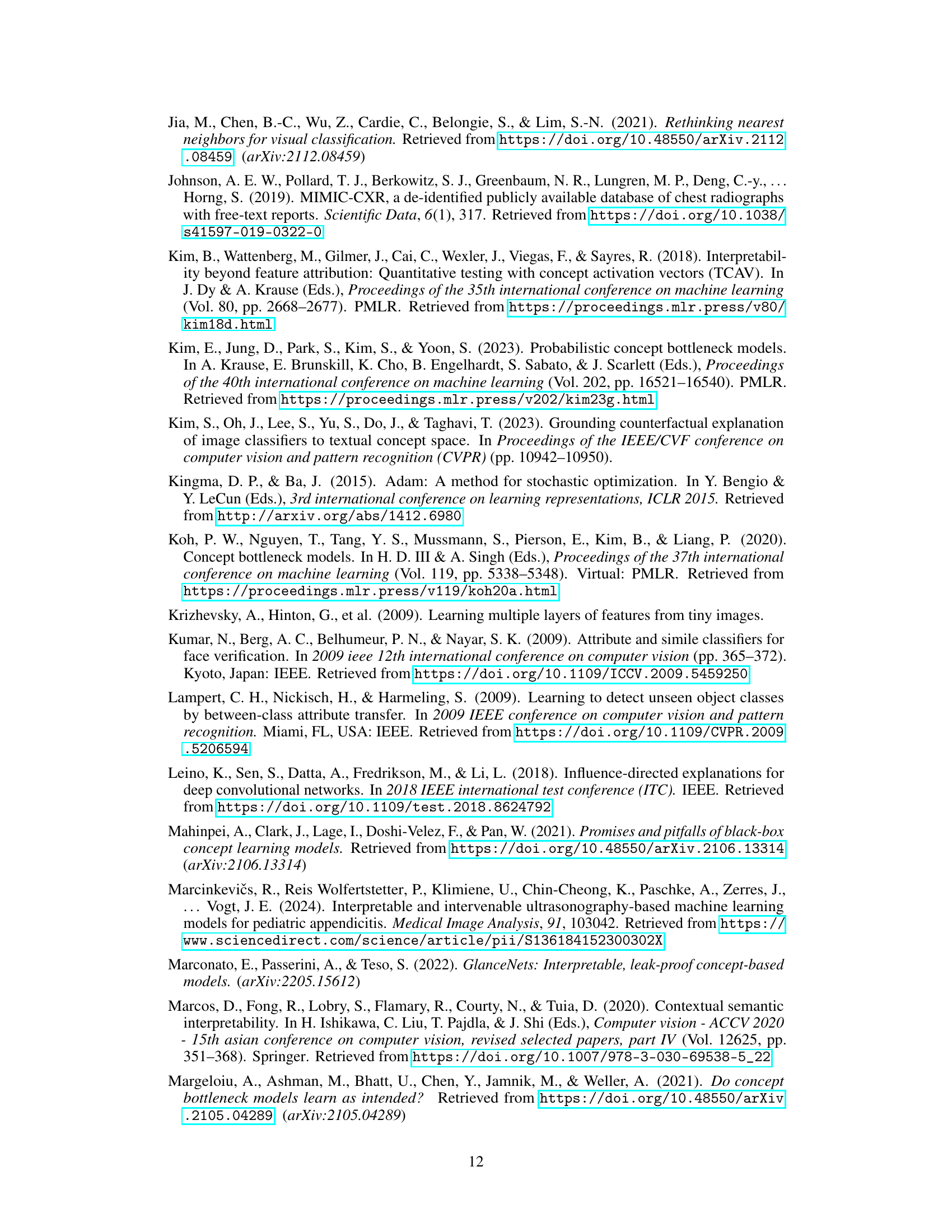

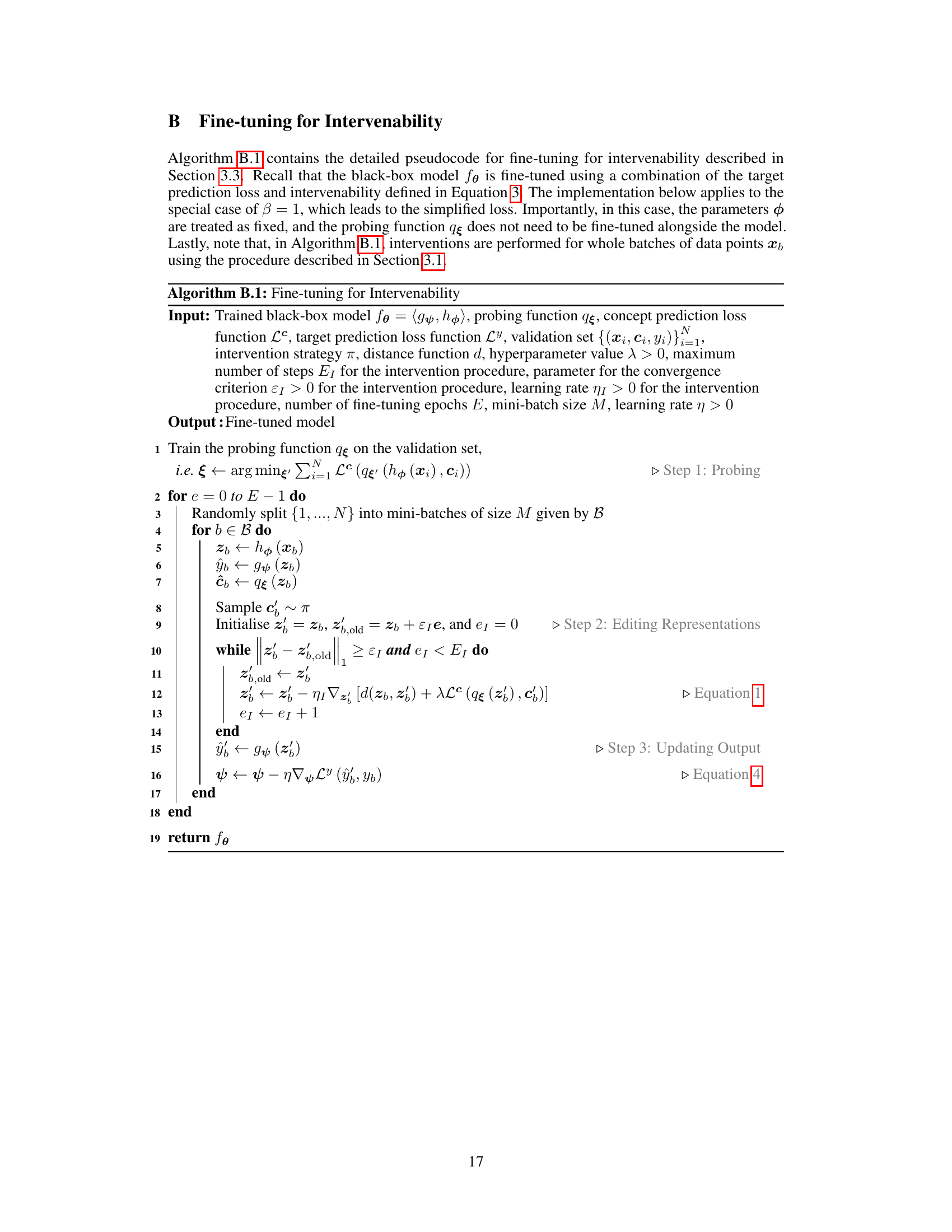

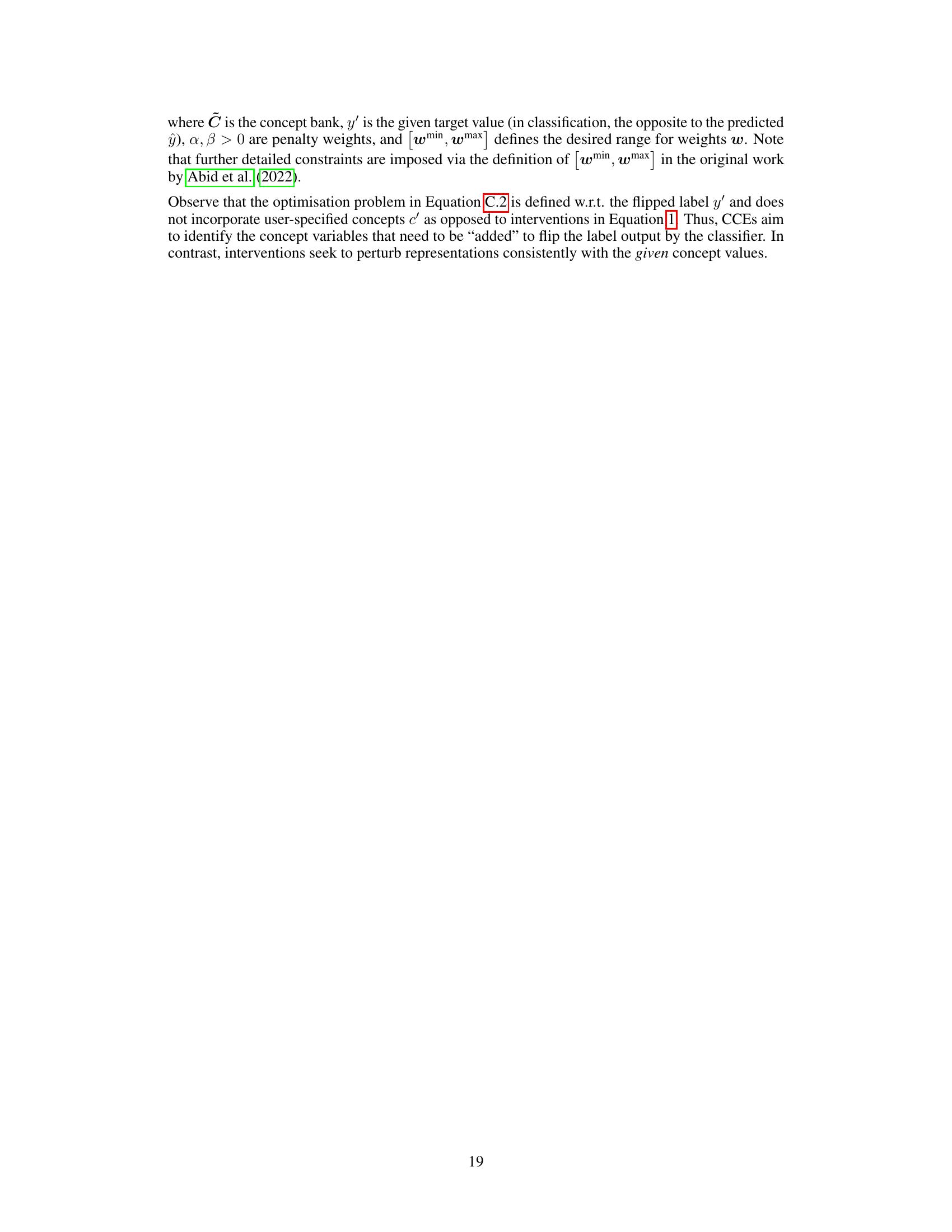

Visual Insights#

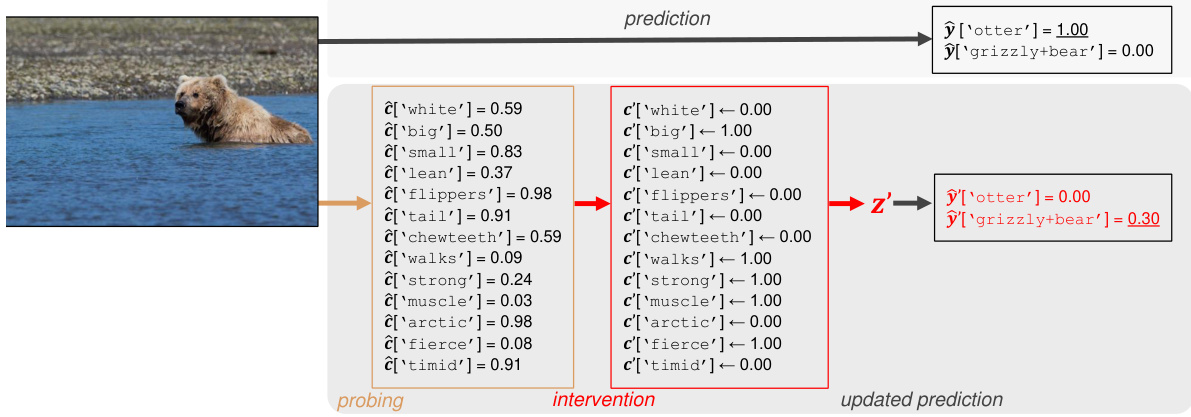

The figure shows an example of how the proposed method can be used to correct a misclassification by intervening on the predicted concept values. The initial prediction is for ‘otter’, while the actual image is a grizzly bear. By changing the values of concepts such as ‘fierce’, ’timid’, ‘muscle’, and ‘walks’, the model’s prediction is changed to ‘grizzly bear’. This demonstrates the model’s ability to perform instance-specific interventions and illustrates the basic idea behind the concept-based intervention method.

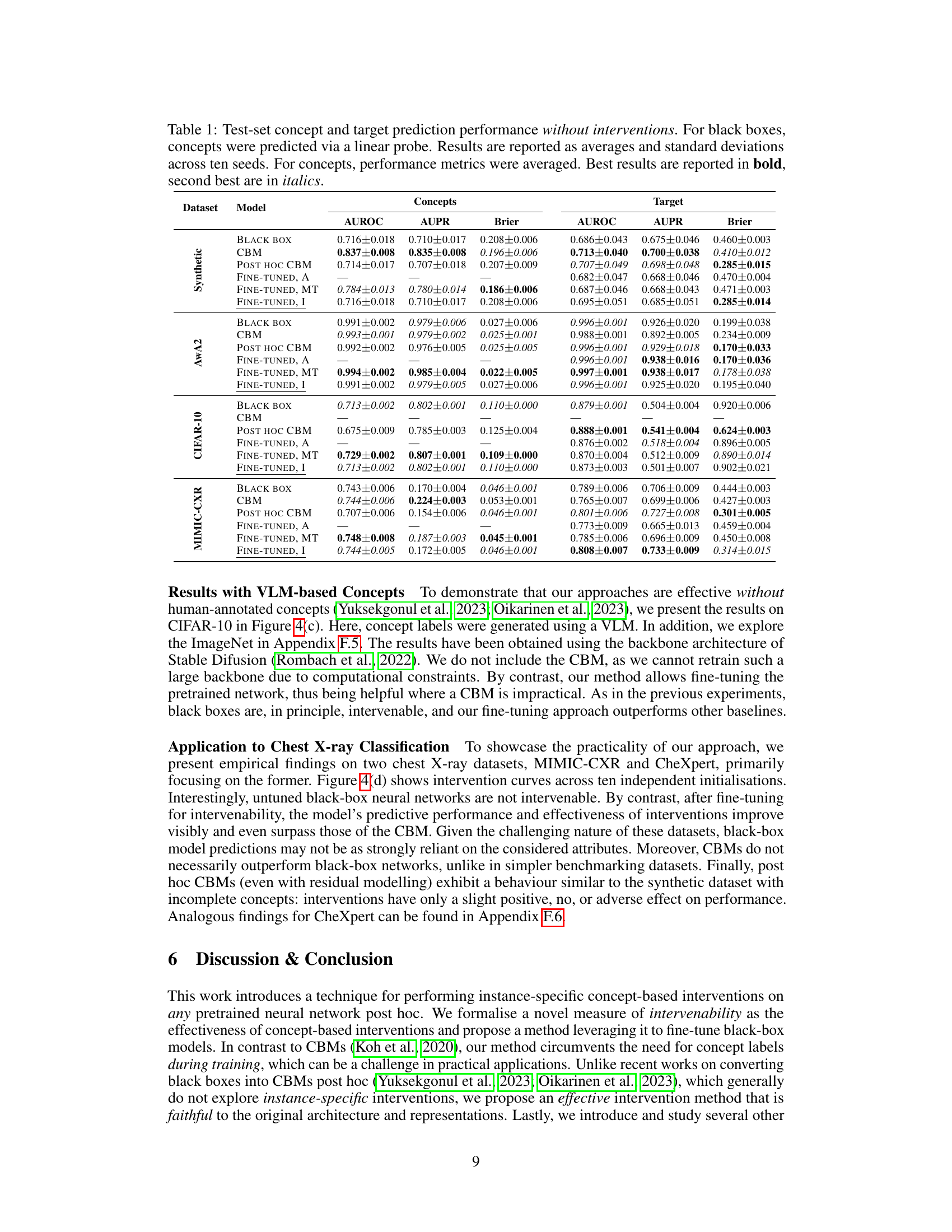

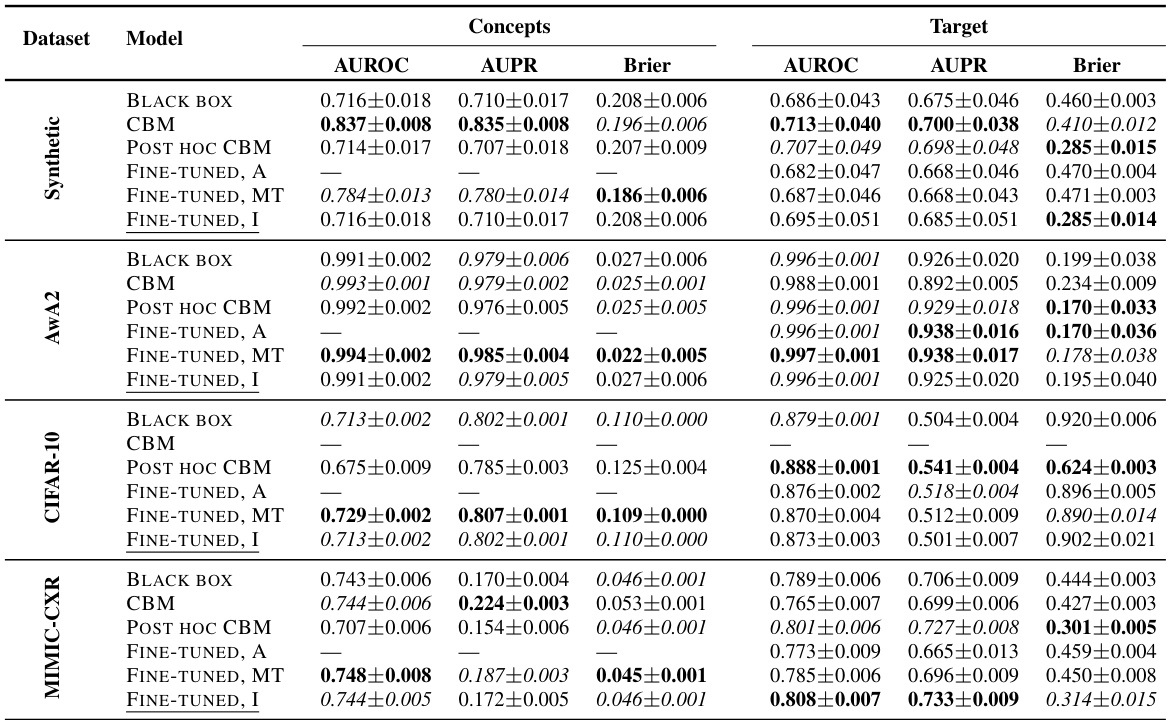

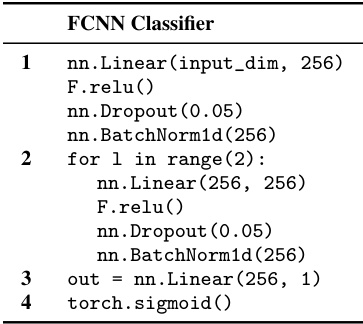

This table presents the performance of different models on various datasets in terms of AUROC, AUPR, and Brier score for both concept and target prediction tasks, without performing any interventions. It compares the performance of a standard black-box model against a concept bottleneck model (CBM), a post-hoc CBM, and several fine-tuned variants of the black-box model. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

Concept Intervention#

Concept intervention, within the context of machine learning, focuses on manipulating a model’s internal representations to influence its predictions based on high-level concepts. It moves beyond simply interpreting model outputs by allowing direct interaction and modification of the decision-making process. This approach offers several advantages, including the potential for improved model explainability and the opportunity to correct biased or erroneous predictions. For instance, in medical diagnosis, a doctor might intervene by adjusting predicted concepts like “lung opacity” or “edema,” thereby altering the model’s overall assessment. However, successful concept intervention requires carefully designed methods for probing the model’s internal states and for effectively manipulating those states based on user-specified concept values. Moreover, intervenability itself, or the effectiveness of interventions, needs to be rigorously defined and measured to evaluate the success of the method. The ability to fine-tune models for optimal intervenability is crucial, ensuring the changes are meaningful and predictable, and not simply random adjustments.

Intervenability Metric#

The concept of an ‘Intervenability Metric’ in the context of a research paper on machine learning models is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of human-in-the-loop interventions. It assesses how well a model’s predictions respond to changes in intermediate representations guided by user-specified concepts. A well-designed metric should quantify the impact of these interventions on model performance, ideally showing improvement with more accurate concept inputs. This would involve comparing the model’s original prediction with the revised prediction after intervention and assessing the change in prediction accuracy or error. A robust intervenability metric would need to account for several factors, including different types of interventions, varying degrees of concept certainty, and model architecture. The metric could then be used to guide model training or fine-tuning, enabling the development of models more amenable to human oversight and control. The challenge lies in designing a metric that is both computationally feasible and meaningful across various datasets and tasks, ensuring it captures the true impact of human intervention without confounding factors.

Black Box Tuning#

Black box tuning, in the context of machine learning, refers to the process of improving the performance or interpretability of a pre-trained model whose inner workings are opaque. The core challenge lies in optimizing a model without direct access to its internal parameters or representations. Techniques often involve methods that leverage external information or surrogate objectives. For instance, concept-based interventions might involve adjusting the model’s outputs by modifying activations at intermediate layers to align with high-level human-understandable attributes. Another approach might be to use a validation set with concept labels to fine-tune the model’s behavior, enhancing its intervenability – the effectiveness of such adjustments. The success of black box tuning strongly depends on the availability of appropriate external data and the chosen optimization strategy. Fine-tuning methods must carefully balance improving target performance with maintaining the model’s overall behavior and structure, to be useful in practical applications. Evaluating the effectiveness relies on metrics that quantify how well interventions affect downstream predictions. In summary, black box tuning presents a multifaceted area of research with considerable potential, but also significant challenges in terms of methodology and evaluation.

VLM Concept Use#

The utilization of Vision-Language Models (VLMs) for concept annotation presents a significant advancement in interpretable machine learning. Traditional methods often rely on laborious and expensive human annotation of validation sets with concept labels. VLMs automate this process, leveraging their ability to understand both visual and textual information to generate concept labels for images. This automation is particularly beneficial when dealing with large datasets where human annotation would be impractical. However, relying on VLMs introduces potential biases and limitations inherent in the models themselves, which may affect the accuracy and reliability of the derived concepts. Further research is needed to investigate and mitigate these biases, as well as explore the impact of VLM-derived concepts on the overall performance and intervenability of black-box models. The effectiveness of the proposed intervention techniques will depend heavily on the quality and relevance of these automatically generated concepts.

Future Work#

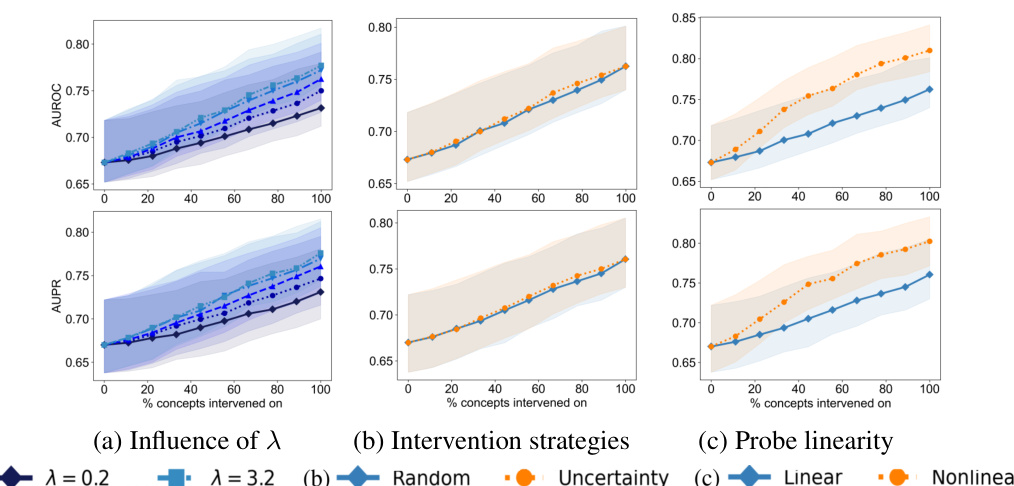

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section suggests several promising avenues for extending the current research. Addressing the limitations of the current fine-tuning procedure is paramount, particularly exploring a more comprehensive end-to-end fine-tuning approach that optimizes both the model and probing function simultaneously. A deeper investigation into the influence of hyperparameters, intervention strategies, and the choice of distance function are needed to refine the intervention process. Further research is also needed to develop optimal intervention strategies. The current work focuses on a single fixed strategy; developing adaptive strategies would significantly improve the system’s capability. The study primarily uses classification tasks; applying the proposed intervenability measure and techniques to generative models is an important next step, along with comparing effectiveness across different model architectures. Finally, expanding the types of datasets used, particularly with more nuanced real-world scenarios, will yield more robust and generalizable results. The ultimate goal is to move beyond the current limitations and establish intervenability as a reliable metric for evaluating and improving the interpretability of machine learning models.

More visual insights#

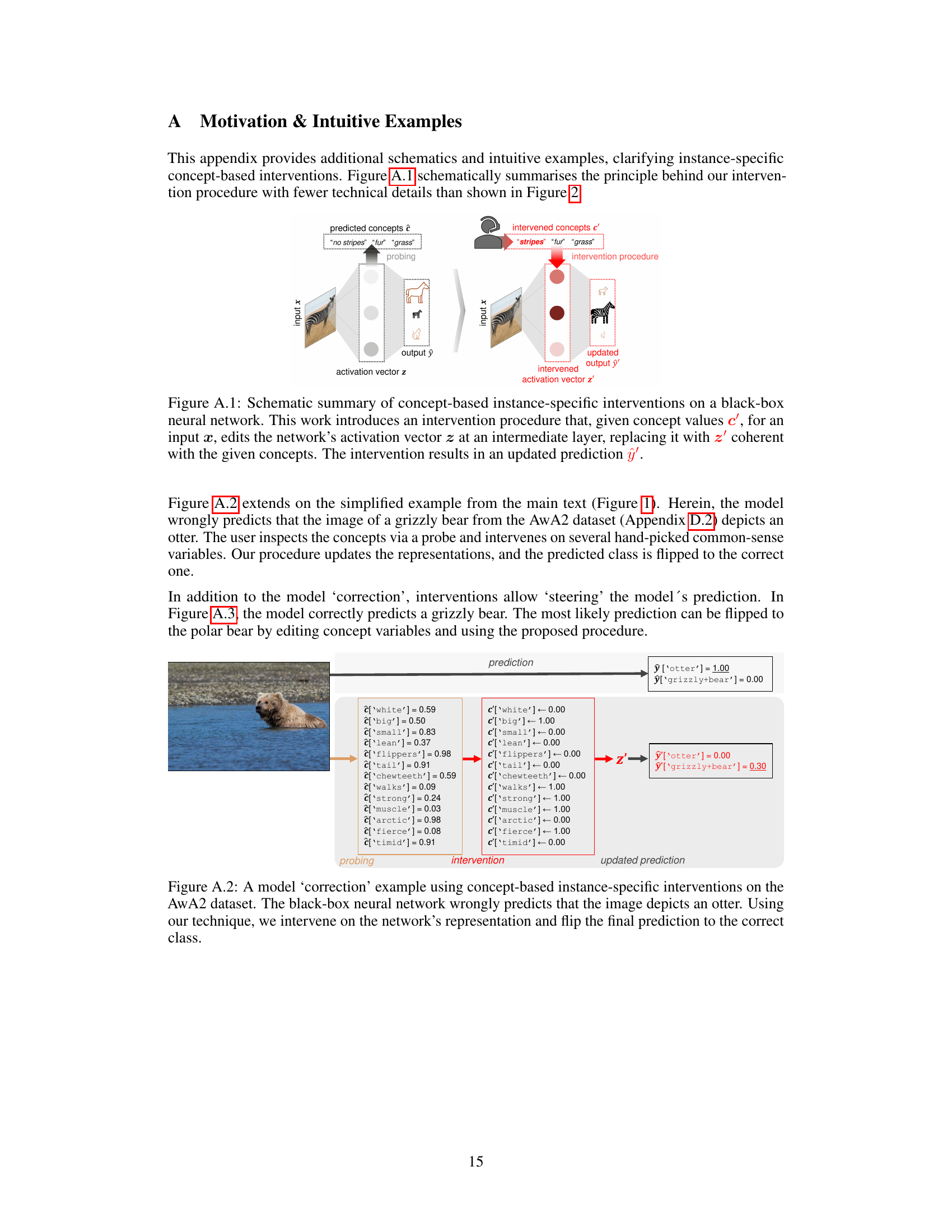

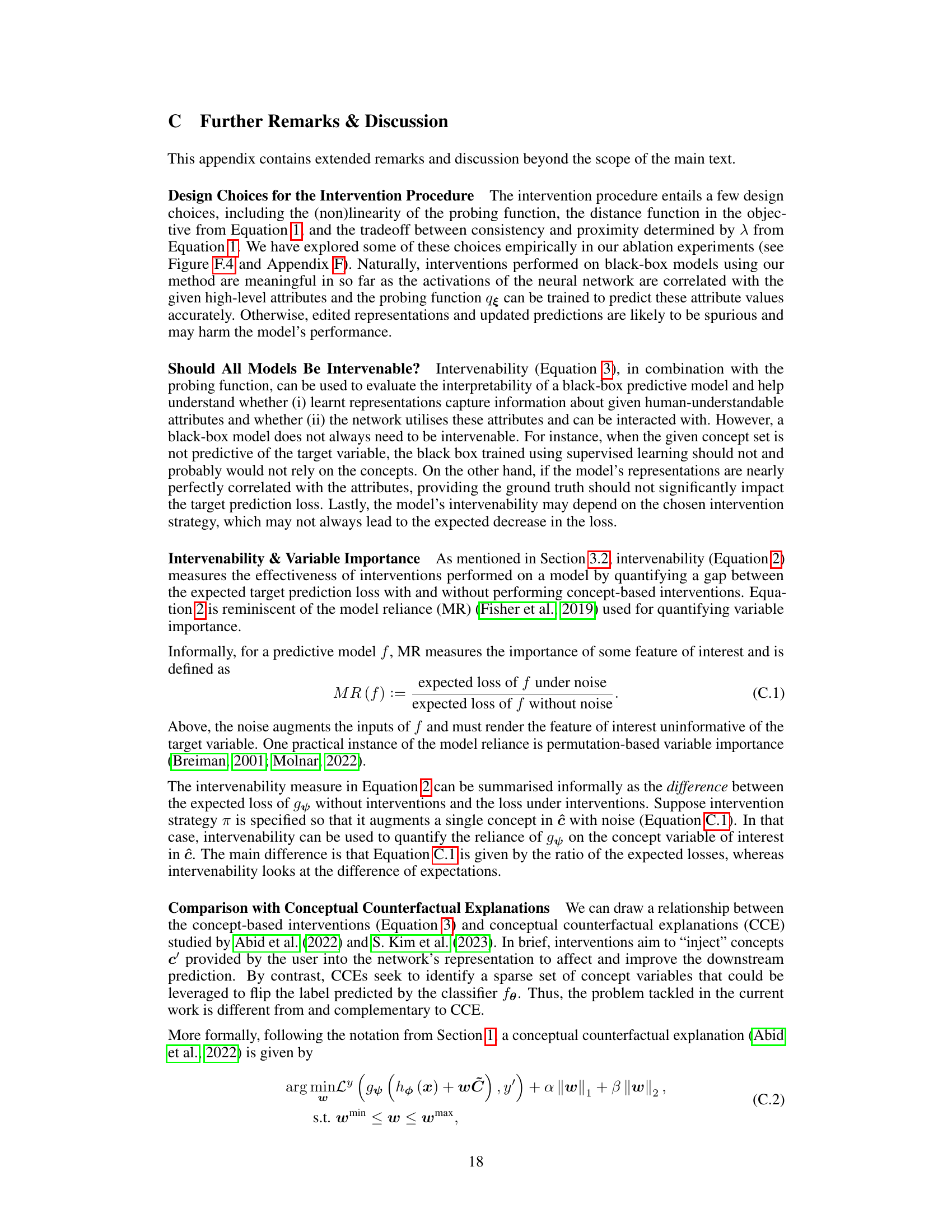

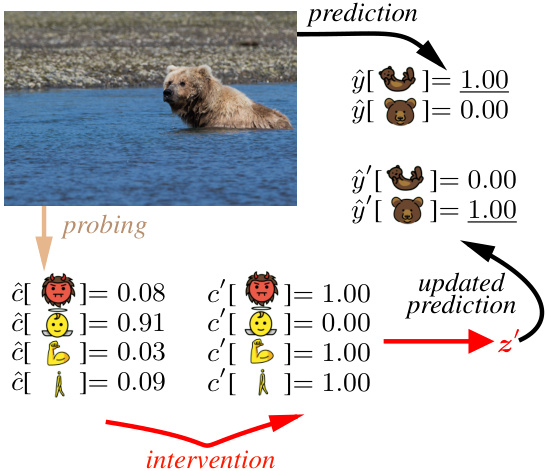

More on figures

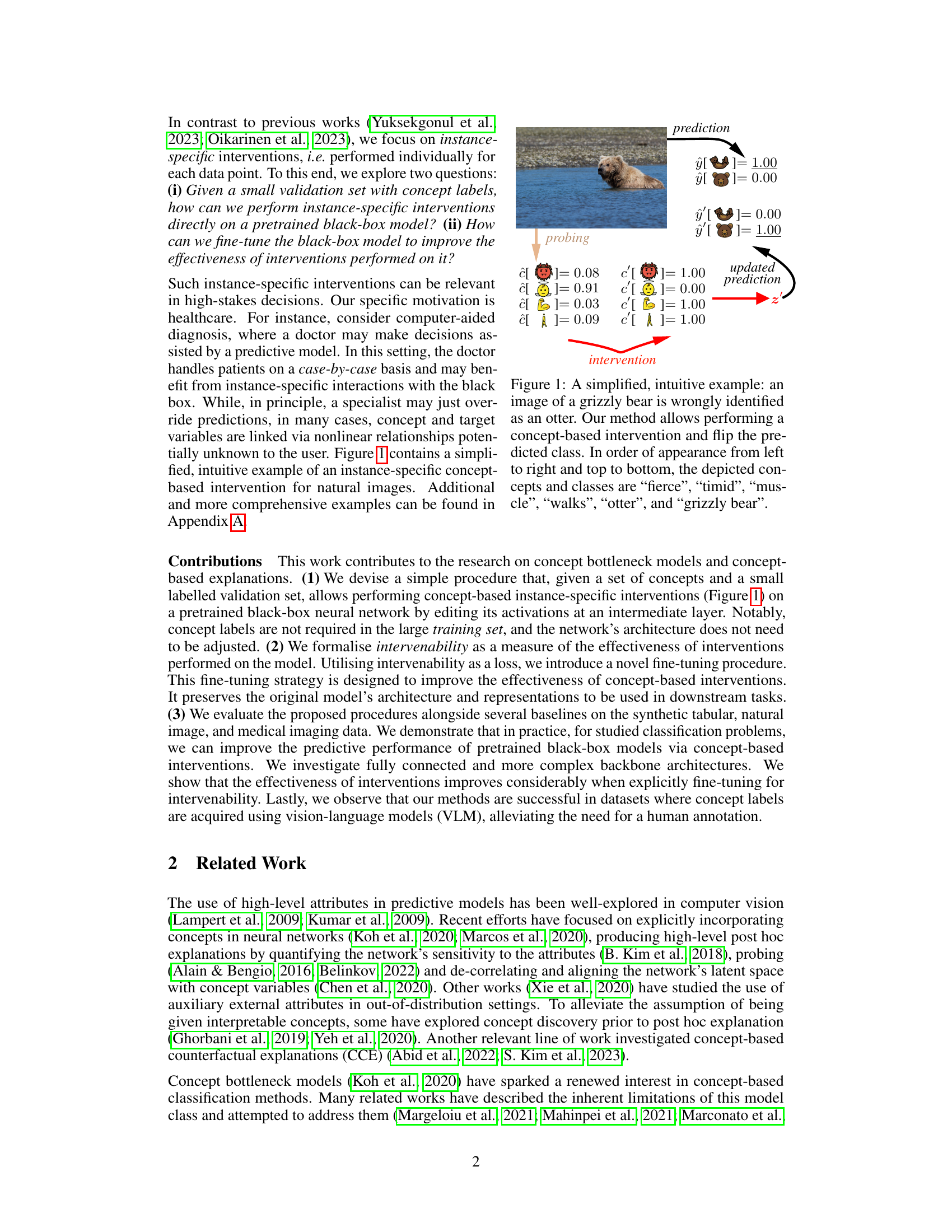

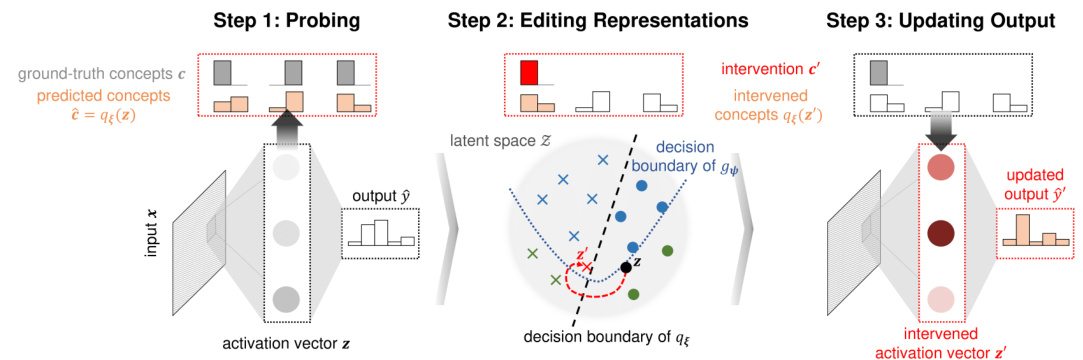

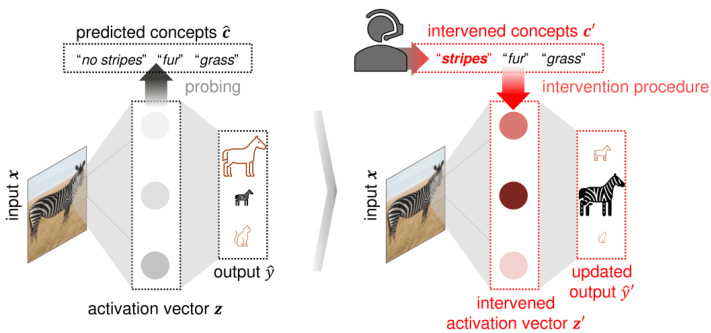

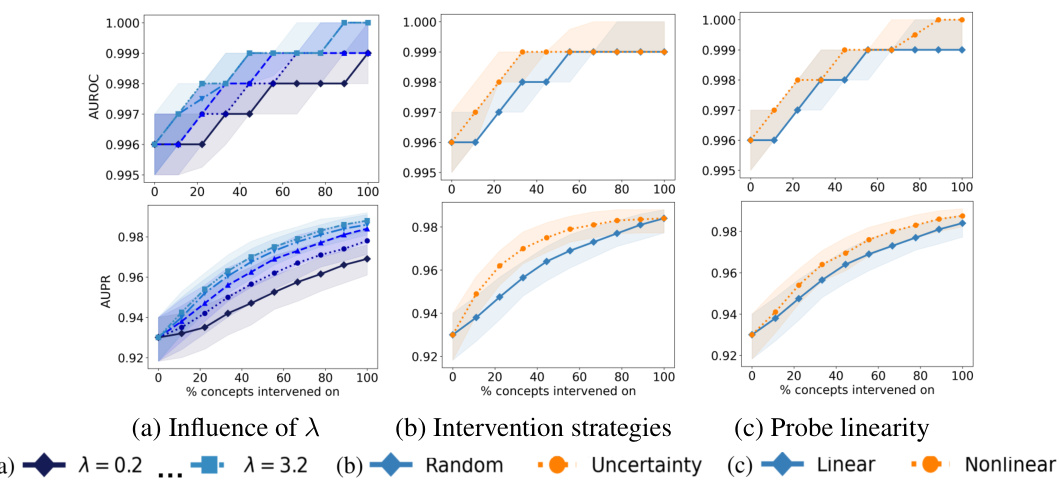

This figure illustrates the three steps involved in the intervention procedure. First, a probe is trained to predict concepts from the model’s internal representation (activation vector). Second, the representation is edited to align with the desired concept values using a distance function and a hyperparameter that balances the tradeoff between the intervention’s validity and its proximity to the original representation. Third, this edited representation is used to update the model’s final prediction. The figure uses diagrams to represent the input, internal representation, and output of the model.

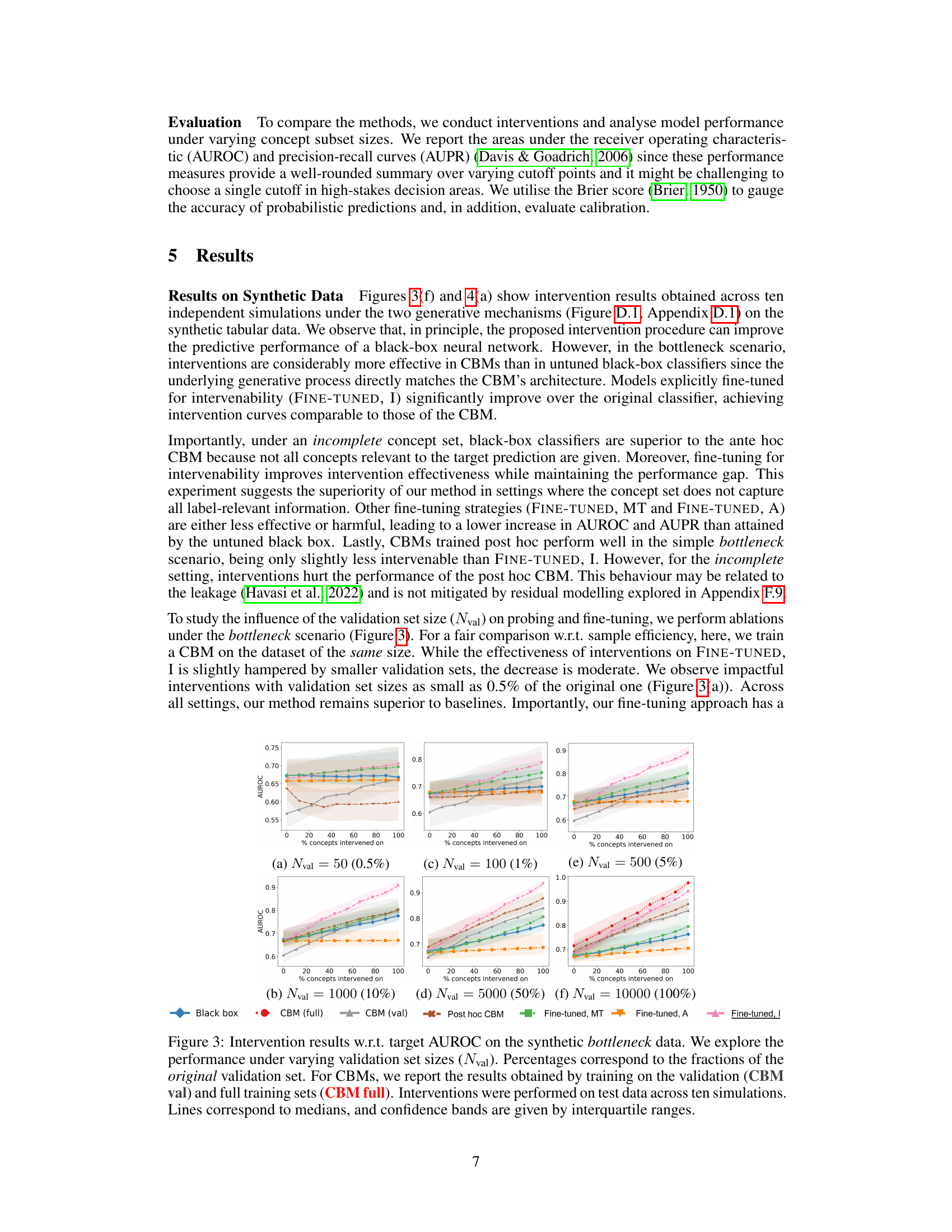

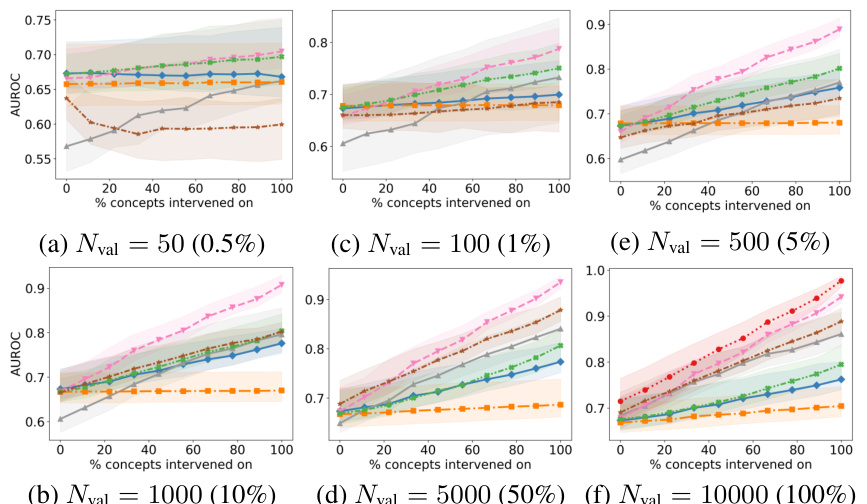

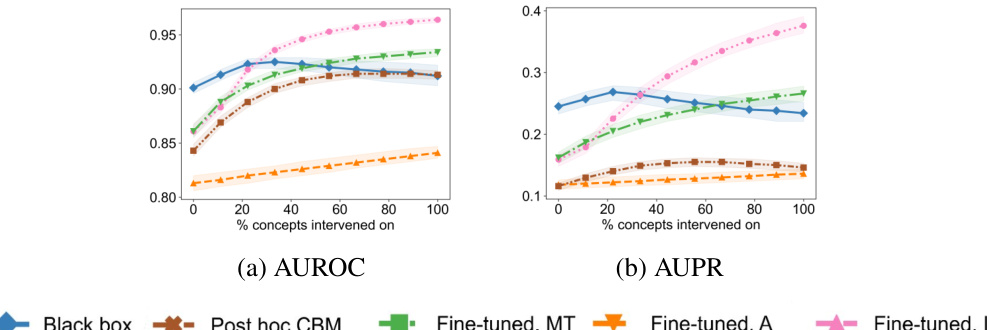

This figure displays the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) for different methods on synthetic bottleneck data, comparing how well interventions work when changing different numbers of concept values. It shows the impact of the validation set size (Nval) on the performance of several methods including black-box models, concept bottleneck models (CBM), and variations of fine-tuned models. The plots show the median AUROC across multiple trials, with error bars representing the interquartile range.

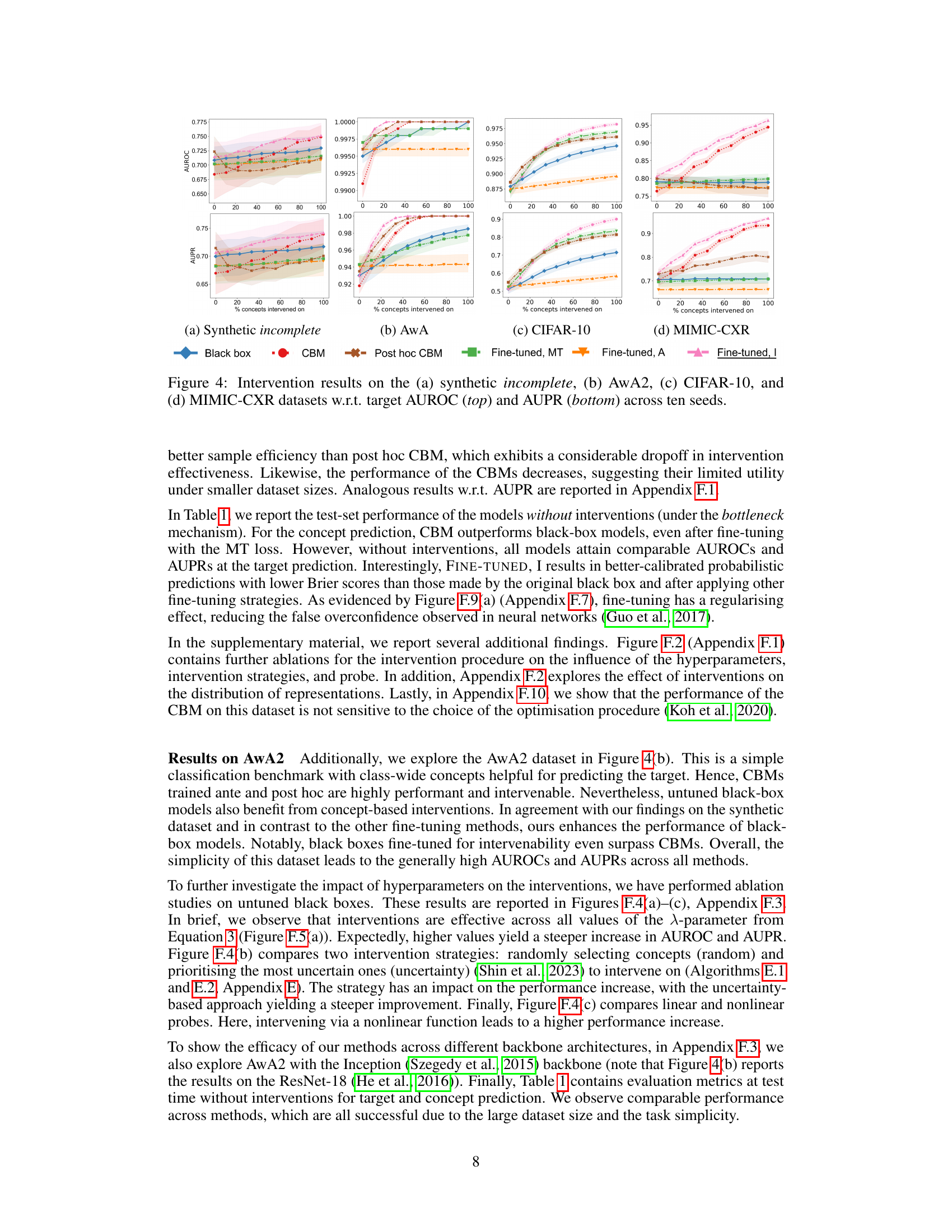

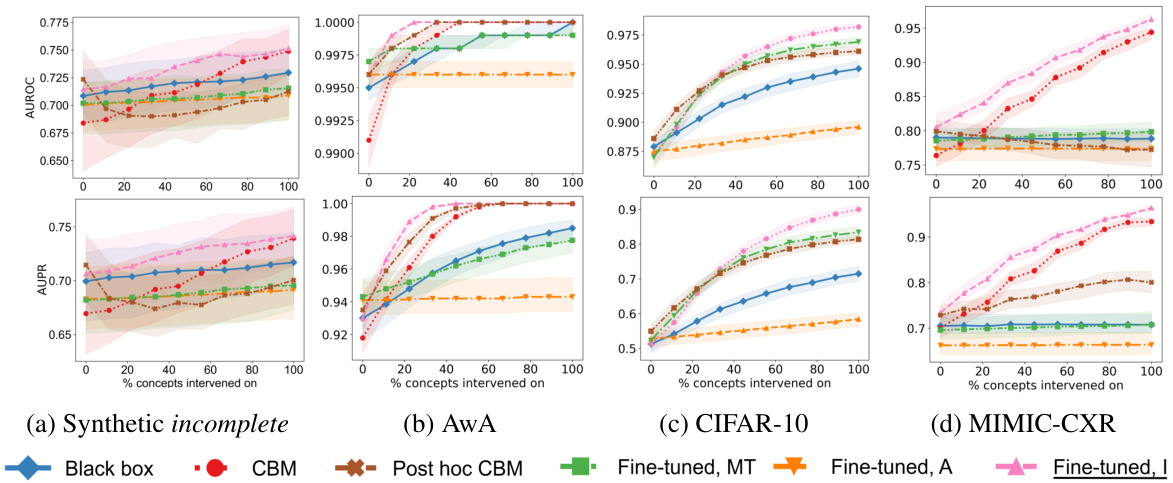

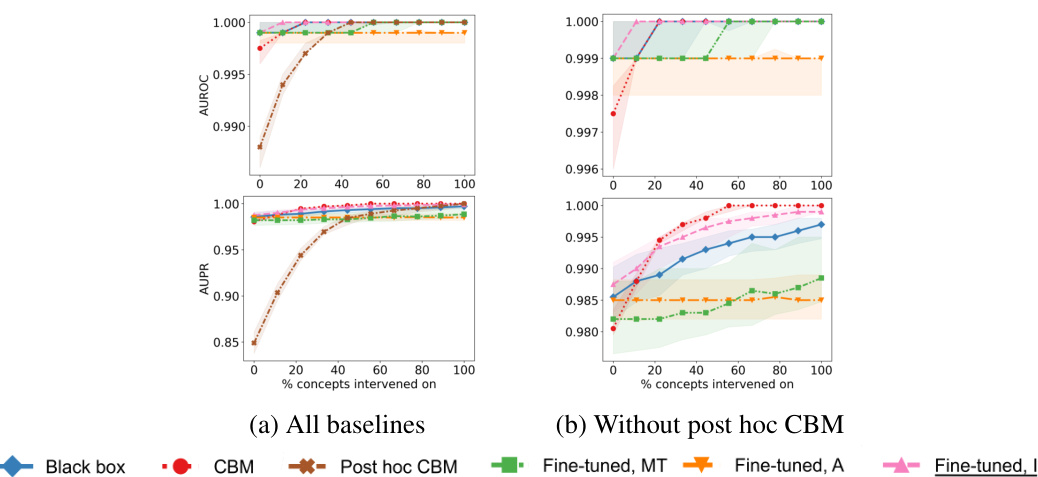

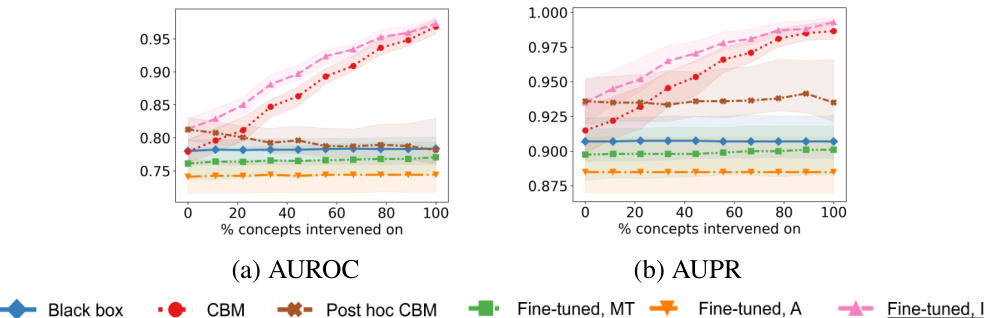

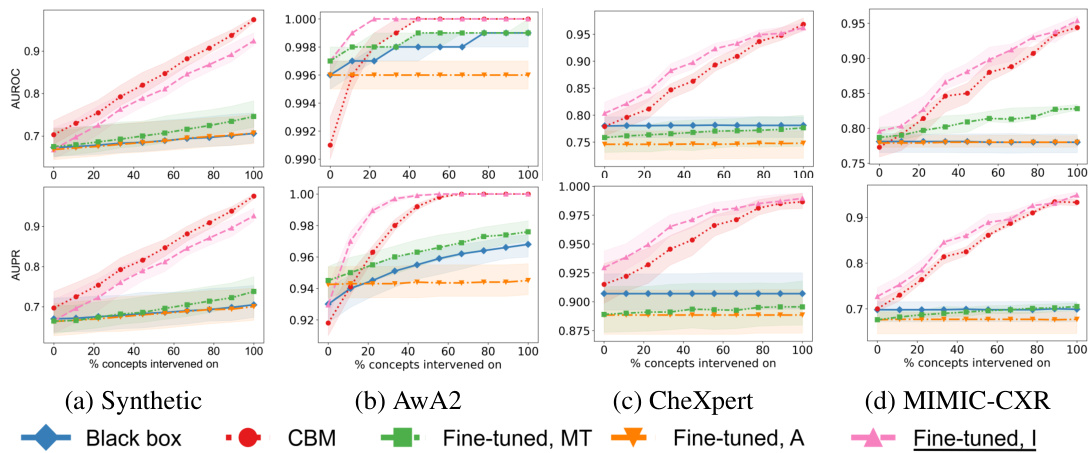

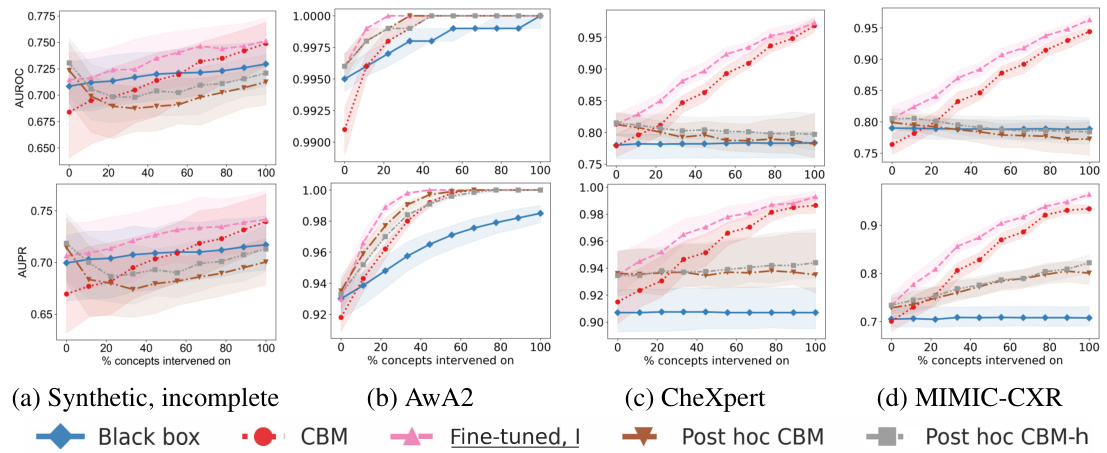

This figure displays the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the Area Under the Precision-Recall curve (AUPR) for four different datasets (synthetic incomplete, AwA2, CIFAR-10, and MIMIC-CXR). Each plot shows the performance of different intervention methods (Black box, CBM, Post hoc CBM, Fine-tuned, MT, Fine-tuned, A, and Fine-tuned, I) as the percentage of concepts intervened upon increases. The top row shows AUROC, while the bottom row shows AUPR. Each data point represents an average across 10 runs. This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed fine-tuning for intervenability method compared to other baseline methods in various datasets.

This figure illustrates the three steps involved in the intervention procedure used in the paper. First, a probe is trained to predict concepts from the activation vector of a neural network. Then, the representation is edited to align with the desired concept values, using a method that balances similarity to the original representation and consistency with the desired concept. Finally, the model’s output is updated based on the edited representation.

The figure shows an example of how the proposed intervention method can correct a misclassification by a black-box model. The model initially misclassifies a grizzly bear as an otter. The user then intervenes by modifying the predicted concept values (e.g., changing ‘flippers’ from 0.98 to 0.00 and ‘strong’ from 0.24 to 1.00). This intervention alters the model’s internal representation, resulting in a corrected prediction of ‘grizzly bear’. The example highlights the ability to correct errors in black-box models using instance-specific concept-based interventions.

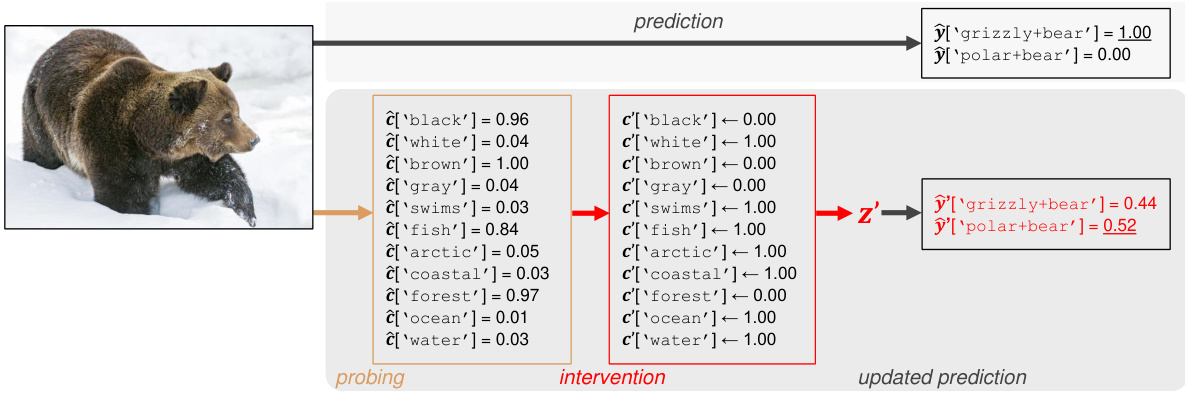

This figure shows an example of how the proposed intervention method can be used to influence the model’s prediction by editing the predicted concept values. The original image is a grizzly bear, and the model initially predicts it as a grizzly bear. However, by changing some of the predicted concept values (e.g., changing ‘black’ to ‘white’, ‘swims’ to 1.00, etc.), the model’s prediction is changed to polar bear. This demonstrates the ability of the proposed method to steer the model’s predictions by manipulating its high-level attributes.

This figure shows the three steps of the intervention procedure applied to a black-box model. First, a probe is trained to predict concepts from the activation vector. Second, the representations are edited to align with the desired concept values. Finally, the prediction is updated based on these edited representations. This procedure allows for instance-specific interventions by modifying the model’s internal representations to reflect the user’s input, thereby changing the model’s output.

This figure illustrates the three steps involved in the intervention procedure. Firstly, a probe is trained to predict concepts from the activation vector. Secondly, the representation is edited to align with the desired concept values. Lastly, the final prediction is updated based on the edited representation. This process allows for concept-based instance-specific interventions on black-box models.

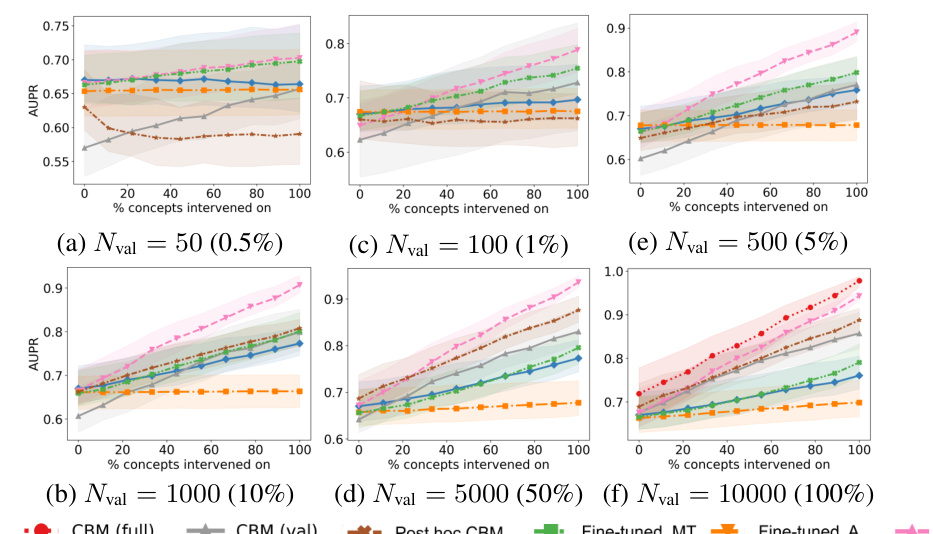

This figure shows the results of intervention experiments on synthetic data with different validation set sizes. It compares the performance of several methods, including CBMs (trained on the full and validation datasets), a post-hoc CBM, and black-box models (with various fine-tuning strategies) in terms of Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC). The x-axis represents the percentage of concepts intervened on, and the y-axis represents the AUROC. The plot displays the median AUROC and interquartile range (error bars) for each method and validation set size, highlighting the impact of different approaches and data availability on intervention effectiveness.

This figure displays the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) for interventions performed on the synthetic bottleneck dataset. The performance is shown for various sizes of the validation set used to train the probing function (Nval), which maps intermediate layer activations to concepts. The results for the Concept Bottleneck Model (CBM) are shown both when trained on the validation set only, and when trained on the full dataset. Other lines represent multiple baseline methods.

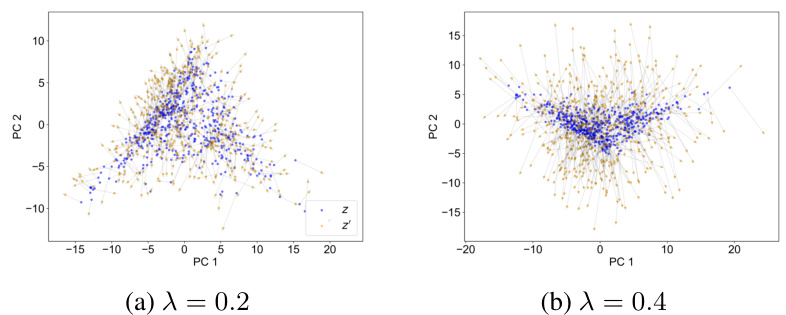

This figure shows the effect of interventions on the model’s internal representation. It uses principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space and visualizes the original representations (z) and the modified representations (z’) after the intervention. The two subfigures (a) and (b) show different levels of the hyperparameter λ which controls the trade-off between the closeness of the modified representation to the original and its consistency with the intervened concepts. (a) shows λ=0.2 where the modified representations are close to the original while (b) with λ=0.4 shows a larger shift in distribution, indicating stronger modifications.

This figure shows the results of the intervention experiments on synthetic data under the bottleneck mechanism. It displays the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve for different sizes of validation sets and varying numbers of intervened-on concepts. It compares the performance of black-box models with and without fine-tuning, comparing them to Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs). The results demonstrate that the proposed fine-tuning improves intervention effectiveness, bringing performance closer to the CBMs.

This figure shows the results of intervention experiments on synthetic data using different validation set sizes. It compares the performance of different methods (black box, CBM, and fine-tuned models) as the number of intervened concepts increases. The results show the impact of validation set size on the effectiveness of concept-based interventions.

This figure displays the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curves for different models under varying validation set sizes in a bottleneck scenario. It shows how the performance of interventions varies with the percentage of concepts intervened upon. The models include a black-box model, a concept bottleneck model (CBM), a post hoc CBM, and three fine-tuned models. The figure also demonstrates that the proposed fine-tuning strategy improves the intervention effectiveness and achieves comparable results to CBM, outperforming baseline models.

This figure displays the results of intervention experiments on synthetic data, focusing on the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) metric. It shows how the performance changes as the percentage of concepts intervened upon varies, comparing different model types (black box, CBM, and fine-tuned variations). The impact of validation set size on performance is also explored. Each line represents the median AUROC across ten simulations, with confidence intervals showing variability.

This figure shows the results of intervention experiments on synthetic data with different sizes of validation sets. The results are presented as AUROC curves showing the model performance after interventions. It compares the performance of black box models, CBMs (trained on full and validation sets), post hoc CBMs, and black box models fine-tuned with different methods (MT, A, I). The plot shows that fine-tuning for intervenability (I) yields the best results, closely matching the performance of CBMs trained on the full dataset, especially with larger validation sets.

This figure shows the results of intervention experiments performed on a synthetic dataset using different validation set sizes. The x-axis represents the percentage of concepts intervened upon, and the y-axis shows the AUROC. The plot shows that the fine-tuned model (FINE-TUNED, I) significantly outperforms the other methods, especially when the validation set size is small.

This figure shows the results of the intervention experiments on the synthetic dataset, in which the validation set size is varied. The x-axis represents the percentage of concepts intervened, and the y-axis shows the AUROC. The results show that the proposed fine-tuning method improves the effectiveness of interventions, especially when the validation set size is small.

This figure presents the results of intervention experiments on four different datasets: synthetic incomplete, AwA2, CIFAR-10 and MIMIC-CXR. For each dataset, it shows AUROC and AUPR curves for different methods, comparing the performance of black-box models, concept bottleneck models (CBMs), post-hoc CBMs, and fine-tuned models. The x-axis represents the percentage of concepts intervened on, while the y-axis shows AUROC and AUPR. The results illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed fine-tuning method in improving the performance of interventions, especially in datasets with complex relationships between concepts and targets.

This figure shows the results of intervention experiments performed on a synthetic dataset with varying validation set sizes. The x-axis represents the percentage of concepts intervened on, while the y-axis represents the AUROC. The different lines represent different models (black box, CBM trained on validation set, CBM trained on full set, and three fine-tuned models). The shaded regions represent confidence intervals. The results demonstrate the impact of validation set size and model type on the effectiveness of interventions.

More on tables

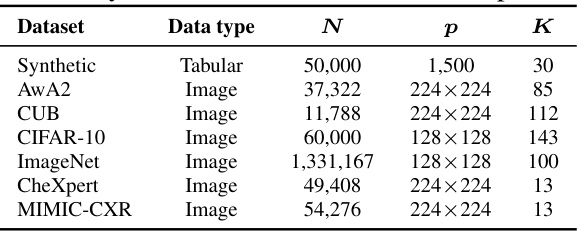

This table summarizes the characteristics of the seven datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it provides the data type (tabular or image), the total number of data points (N), the input dimensionality (p), and the number of concept variables (K). The datasets include synthetic data, image data from various sources (AwA2, CUB, CIFAR-10, ImageNet), and medical image data (CheXpert, MIMIC-CXR). The table is crucial for understanding the scope and diversity of data used to evaluate the proposed method.

This table shows the performance of different models on several datasets without any interventions. It compares a standard black box model, concept bottleneck models (CBM), post-hoc CBMs, and various fine-tuned versions of the black box model. The metrics reported include AUROC, AUPR, and Brier score for both concept and target prediction. Best results are highlighted in bold, and the second best are in italics.

Full paper#