↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a powerful machine learning technique, but different approaches to RL have varying levels of complexity. This paper focuses on three main types of RL: model-based, policy-based, and value-based. Each approach tries to learn something different about the environment: the model-based approach learns a simulation model of the environment, the policy-based approach learns the best actions to take, and the value-based approach learns how good each possible state is.

The paper uses theoretical analysis and experiments to show that learning a good simulation model of the environment is easier than learning the best actions to take. And both of these are easier than learning how good each possible state is. These findings suggest that model-based RL approaches may be most efficient for some problems, policy-based approaches for other problems and that value-based methods might be most suitable in other cases. This hierarchy has implications for algorithm design and resource allocation in RL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals a potential hierarchy in the representation complexity of different reinforcement learning (RL) paradigms. Understanding this hierarchy can significantly improve RL algorithm design, leading to more efficient and sample-efficient learning. The paper bridges theoretical complexity analysis with practical deep RL, offering a novel perspective on representation limitations and suggesting future research directions.

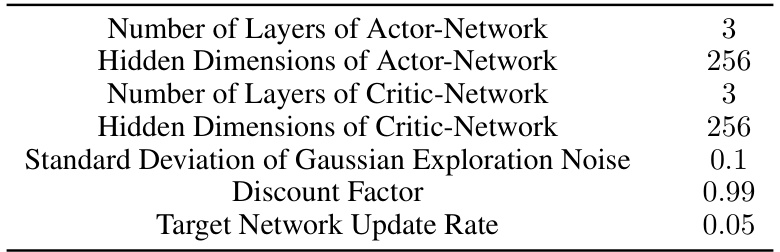

Visual Insights#

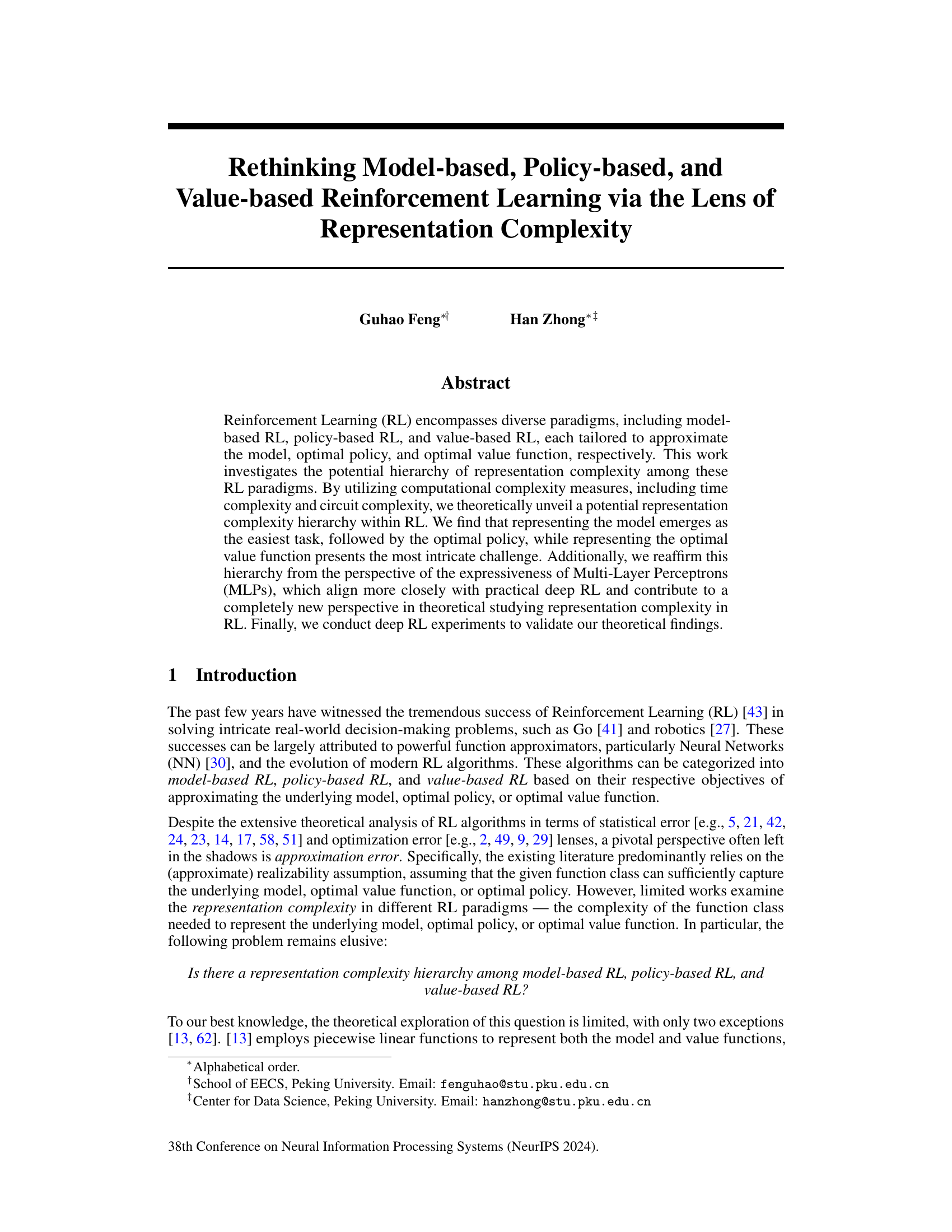

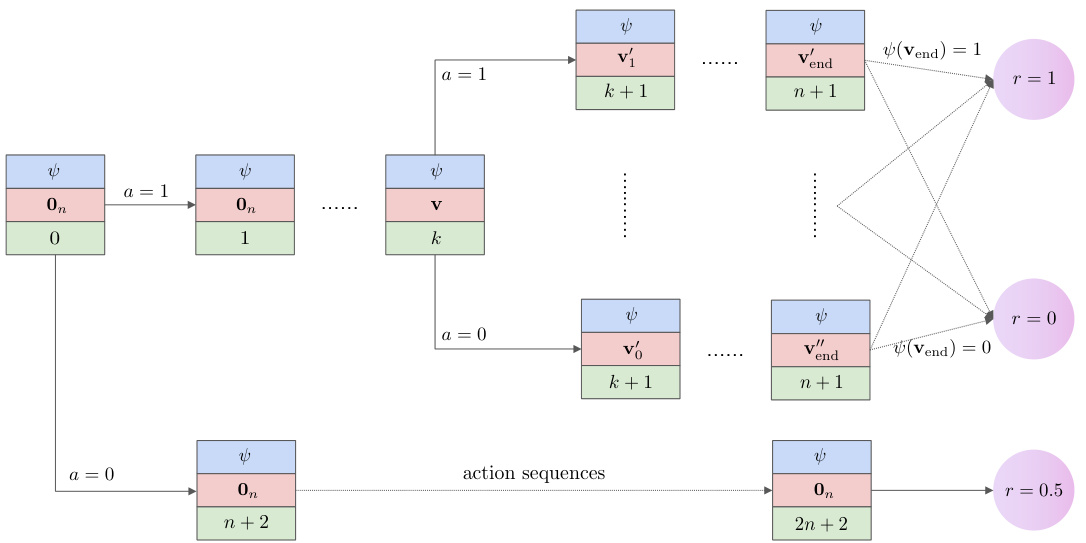

This figure visualizes a 3-SAT Markov Decision Process (MDP). It illustrates how the state transitions and rewards are structured to encode the 3-SAT problem. The state includes a 3-CNF formula (ψ), a binary vector (v) representing variable assignments, and a step counter (k). Actions (a) change the assignment (v), and the reward is 1 if a satisfying assignment is found at the end of the episode. The structure helps demonstrate the complexity of finding the optimal policy and value function compared to the simple representation of the model.

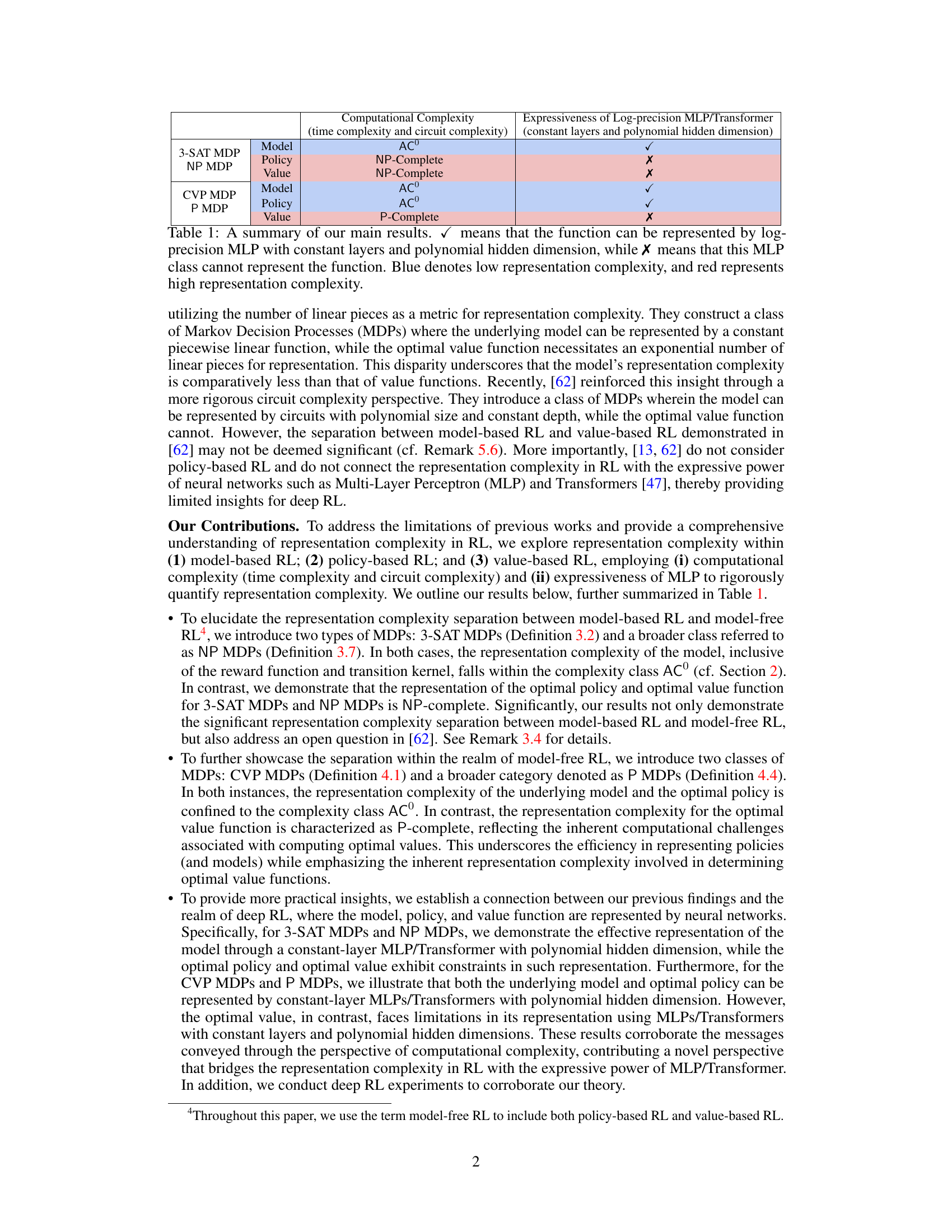

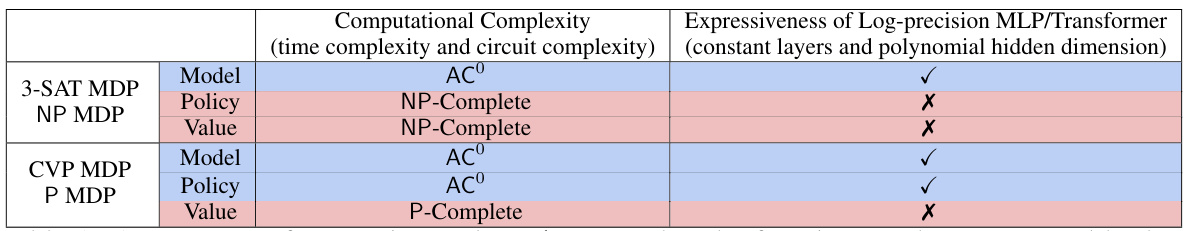

This table summarizes the main findings of the paper regarding the representation complexity of different reinforcement learning paradigms. It shows whether the model, policy, and value function of different types of MDPs (3-SAT MDP, NP MDP, CVP MDP, and P MDP) can be represented using log-precision MLPs with constant layers and polynomial hidden dimensions. A checkmark (✓) indicates representability, while an X indicates non-representability. The color-coding (blue for low complexity, red for high complexity) further emphasizes the representation complexity hierarchy identified by the study.

In-depth insights#

RL Complexity#

Reinforcement Learning (RL) complexity is a multifaceted area of research focusing on understanding the computational and sample-efficiency challenges inherent in various RL paradigms. Model-based RL, aiming to approximate the environment’s dynamics, often shows lower complexity than model-free methods (policy-based and value-based RL). Model-free approaches, focused on directly optimizing policies or value functions, can face significantly higher complexity, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional state and action spaces or sparse rewards. Representation complexity, the difficulty of approximating the model, policy, or value function with a given function class, plays a critical role. Theoretical analyses often reveal a hierarchy of complexity: models are easier to represent than policies, which are in turn easier than value functions. This hierarchy is further validated by examining the expressive power of neural networks commonly used in deep RL, suggesting that approximating value functions remains a significant challenge even for deep learning models. The study of RL complexity provides crucial insights into algorithm design, sample efficiency, and the overall scalability of RL methods. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated complexity measures that better reflect the challenges of real-world RL applications.

MLP Expressiveness#

The section on “MLP Expressiveness” likely explores the capacity of Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) to represent different RL components (model, policy, value function). The authors probably demonstrate a hierarchy of representation complexity, showing that MLPs can easily approximate the model but struggle with the value function, with the policy falling somewhere in between. This aligns with their theoretical findings that model-based RL is representationally simpler than model-free RL (policy and value-based), a key insight potentially supported by empirical results using deep RL. The limitations of MLPs in representing complex value functions might be discussed, possibly in relation to specific function classes or computational complexity measures. This would further strengthen their argument regarding the inherent difficulty of value function approximation in deep RL. The analysis likely bridges the theoretical and practical aspects of representation learning in RL, connecting computational complexity to the expressive power of neural networks.

Deep RL Hierarchy#

The concept of a “Deep RL Hierarchy” proposes a structured relationship between different reinforcement learning approaches based on their representation complexity. Model-based RL, aiming to learn an environment model, is hypothesized to have the lowest complexity, requiring less representational power. Policy-based RL, focusing on directly optimizing the policy, occupies an intermediate level of complexity. Finally, value-based RL, which learns optimal value functions, is posited to exhibit the highest representation complexity. This hierarchy is supported by analyzing the computational resources needed to represent the model, policy, and value function, often using measures like time and circuit complexity. The expressiveness of neural networks, particularly Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), can further validate this hierarchy in the context of deep RL. This framework offers a novel perspective on understanding the inherent challenges and trade-offs in various deep RL approaches, potentially guiding the choice of algorithm based on the complexity of the target task and available resources. Empirical validation, through experiments on benchmark problems, is crucial to confirm this proposed hierarchy and its practical implications.

Theoretical Limits#

A theoretical limits analysis in a research paper would deeply investigate the fundamental constraints and boundaries of a system or method. It would explore questions such as: What are the absolute best-case performance levels achievable? What inherent limitations exist regardless of algorithmic improvements or resource increases? For instance, a theoretical limit might be a fundamental bound on the accuracy achievable by a machine learning model due to noise inherent in the data or the model’s complexity. This analysis often involves proving theorems or deriving mathematical bounds, rather than relying solely on empirical observations. It offers crucial insights by revealing the ultimate potential and inherent limitations, setting realistic expectations for progress and guiding the design of more efficient and effective approaches. The study might examine information-theoretic limits, sample complexity bounds, or computational complexity barriers, providing a rigorous mathematical foundation for understanding the system’s ultimate capabilities and its inherent limitations.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the representation complexity hierarchy to more complex RL settings, such as partially observable MDPs (POMDPs) and continuous MDPs, investigating how the representation complexity changes with the increase in observation uncertainty and state-action space dimensionality. Another direction is to empirically verify the representation complexity hierarchy across a wider range of RL algorithms and environments including those with continuous action spaces, non-Markovian dynamics, or more intricate reward structures. Investigating the relationship between representation complexity, sample efficiency and generalization capabilities of various RL algorithms is also crucial. Finally, exploring how the findings can guide the design of more sample-efficient and robust deep RL algorithms by tailoring function approximation techniques to the inherent representation complexities of different RL paradigms would be valuable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

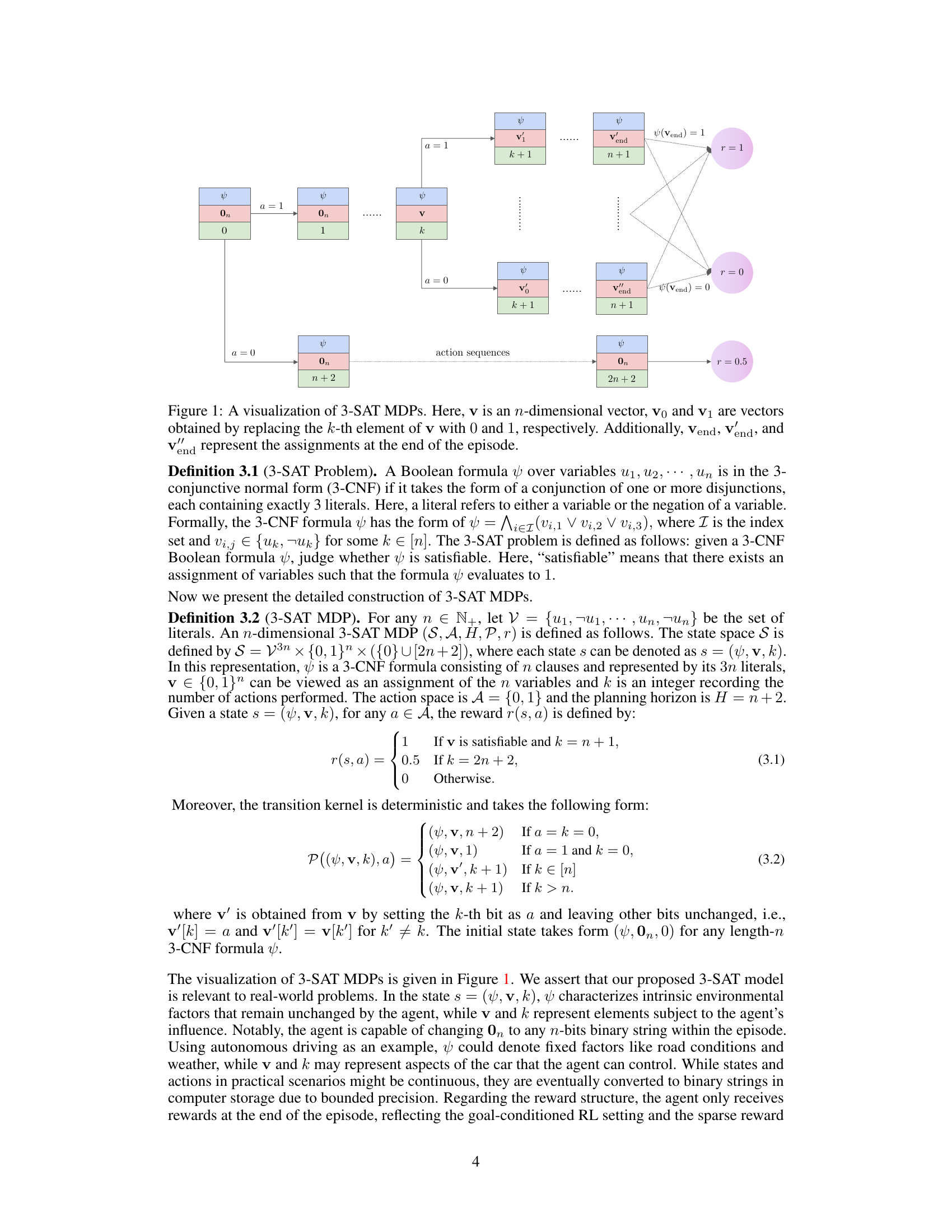

This figure visualizes a 3-SAT Markov Decision Process (MDP). It shows how the MDP models the 3-SAT problem by representing variable assignments as vectors (v). The agent’s actions (a=0 or a=1) modify these vectors, leading to different states. The episode ends when the agent has made n+2 actions. The reward (r) reflects whether the final variable assignment (vend) satisfies the 3-SAT formula (ψ), providing a reward of 1 if satisfied, 0 if not satisfied, and 0.5 if the agent chooses to give up early.

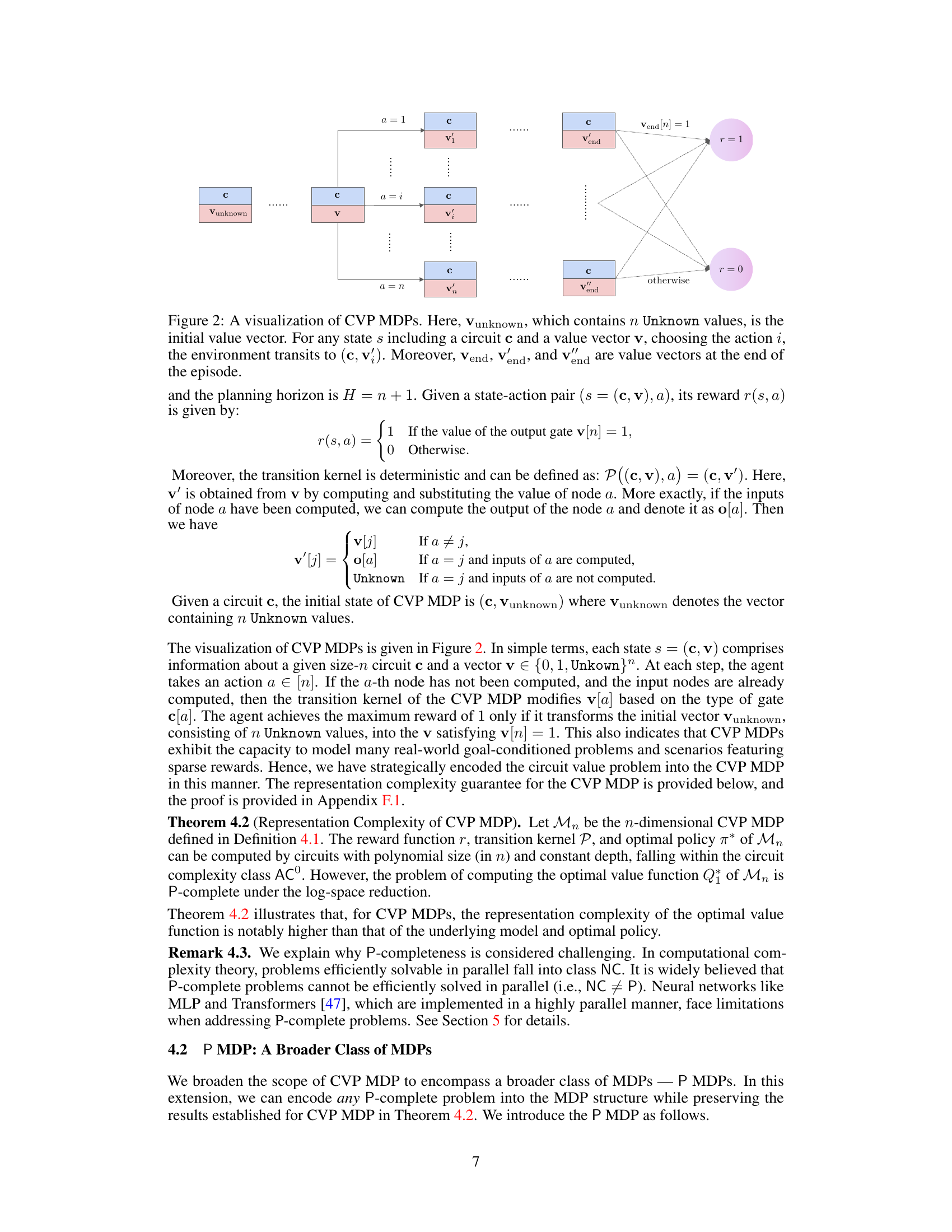

This figure visualizes the CVP MDP, a Markov Decision Process (MDP) designed to model the circuit value problem. The figure shows the states and transitions of the MDP. Each state consists of a circuit and a vector representing the values of the nodes in the circuit. The initial state is (c, vunknown), where vunknown is a vector of n Unknown values. The agent can take action i, which updates the value of the i-th node. The MDP ends in one of two terminal states, one with a reward of 1 (if the output of the circuit is 1) and one with a reward of 0 (otherwise). The transitions show the deterministic update of the value vector based on the chosen action. The process continues until all node values are computed or the terminal states are reached.

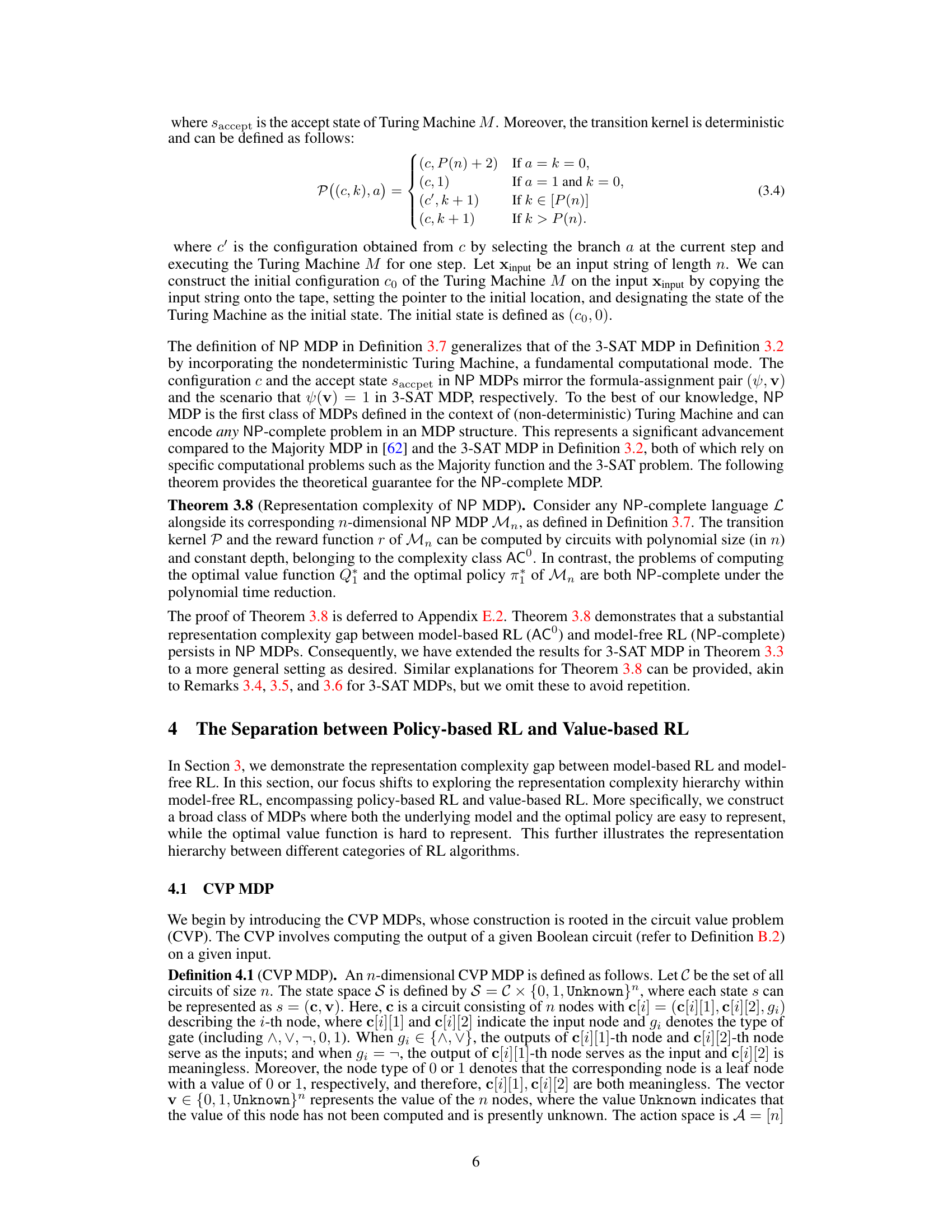

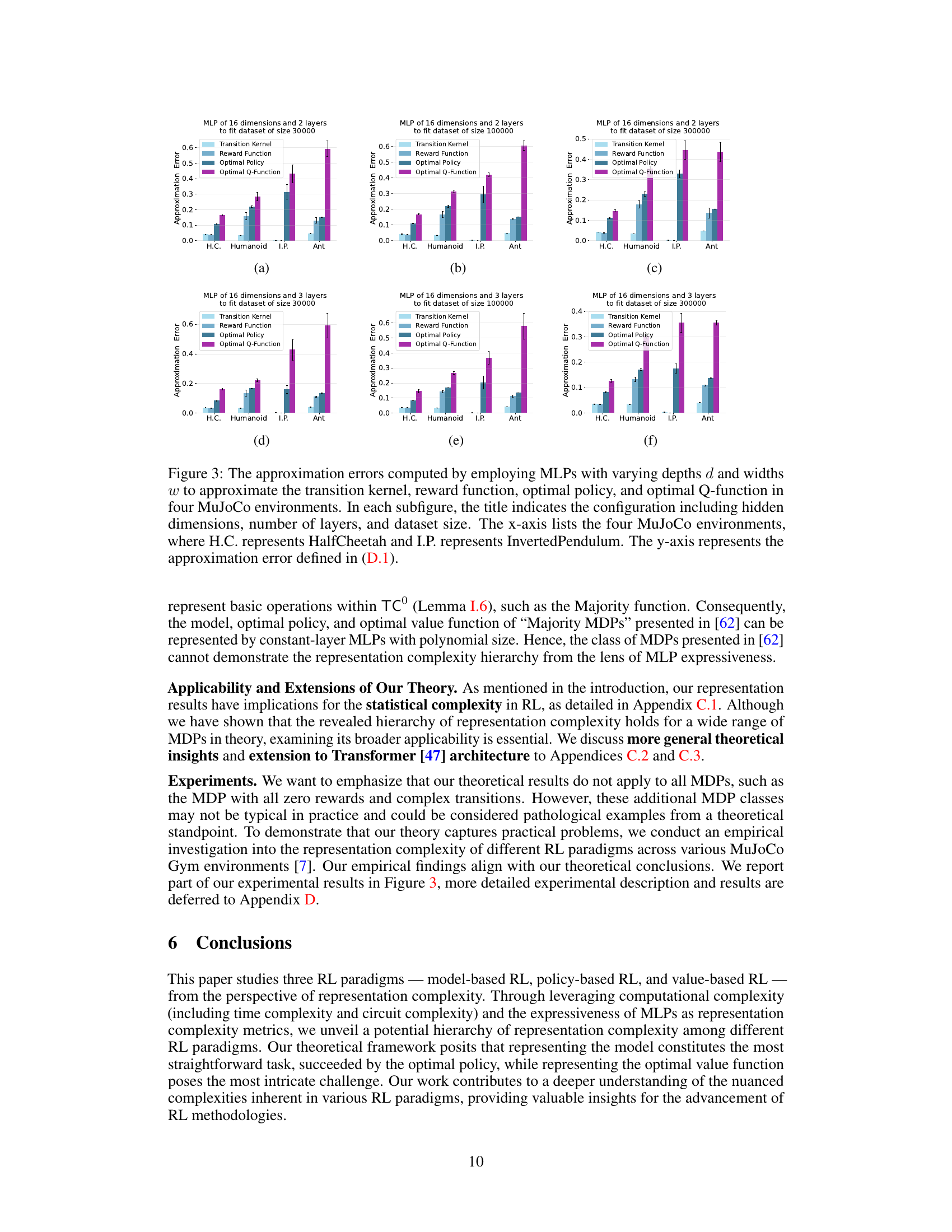

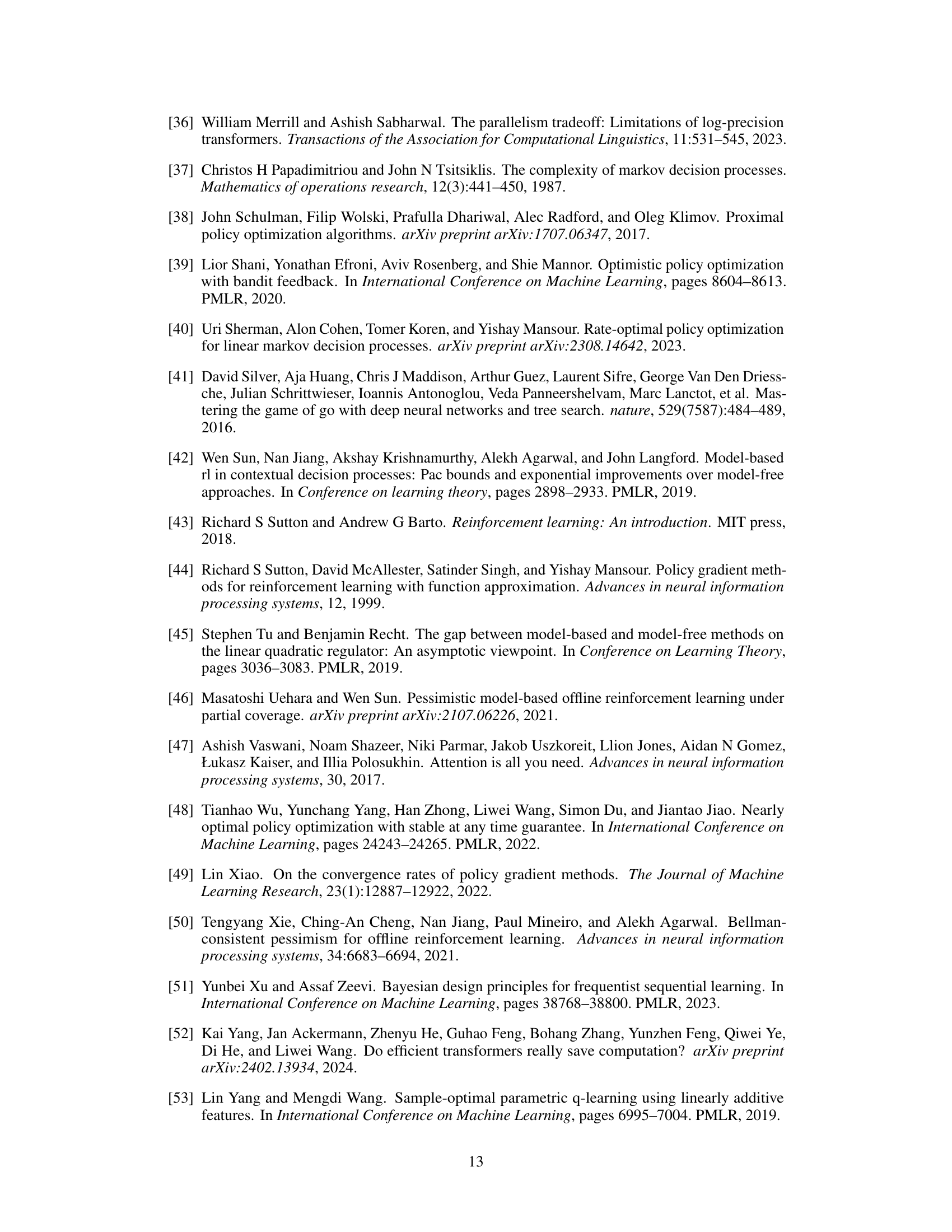

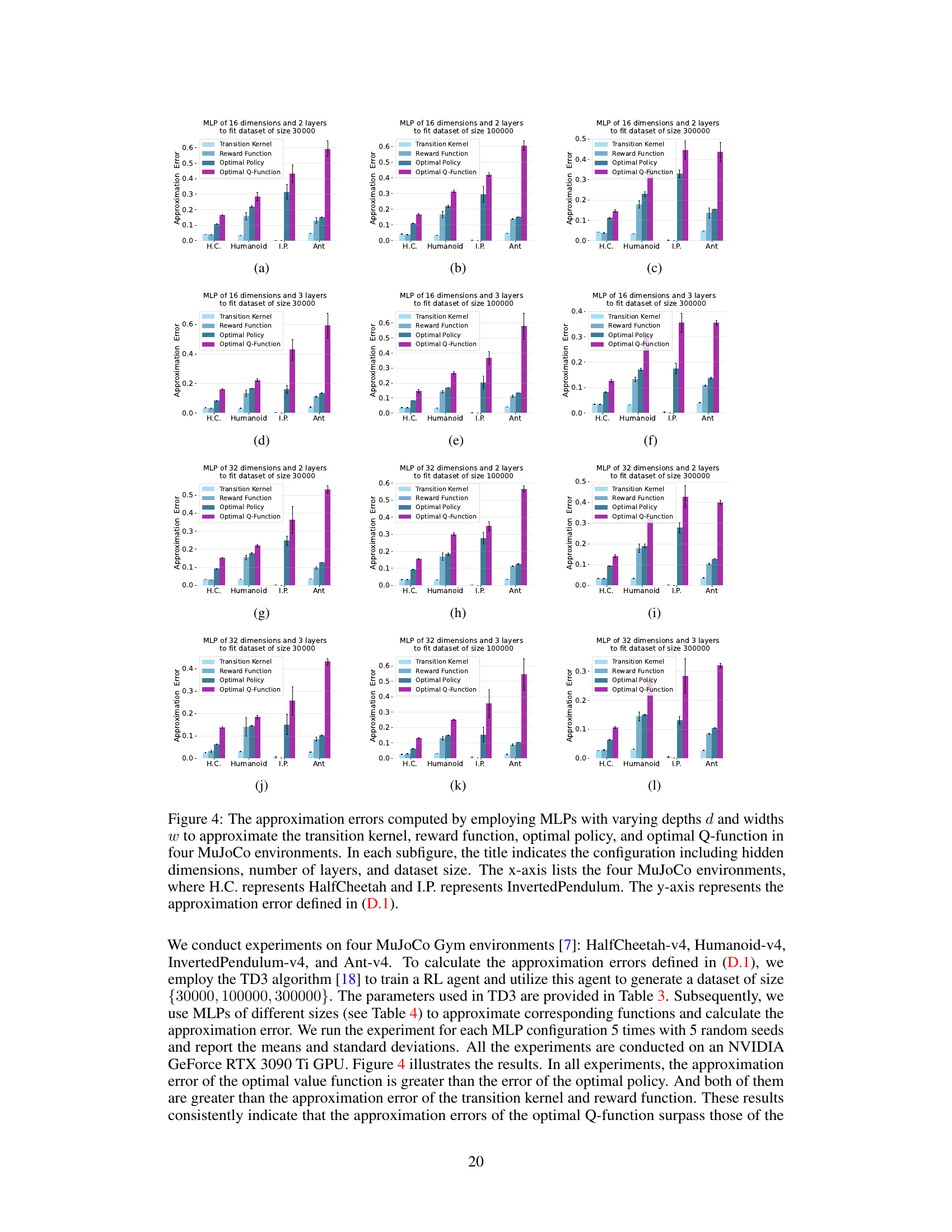

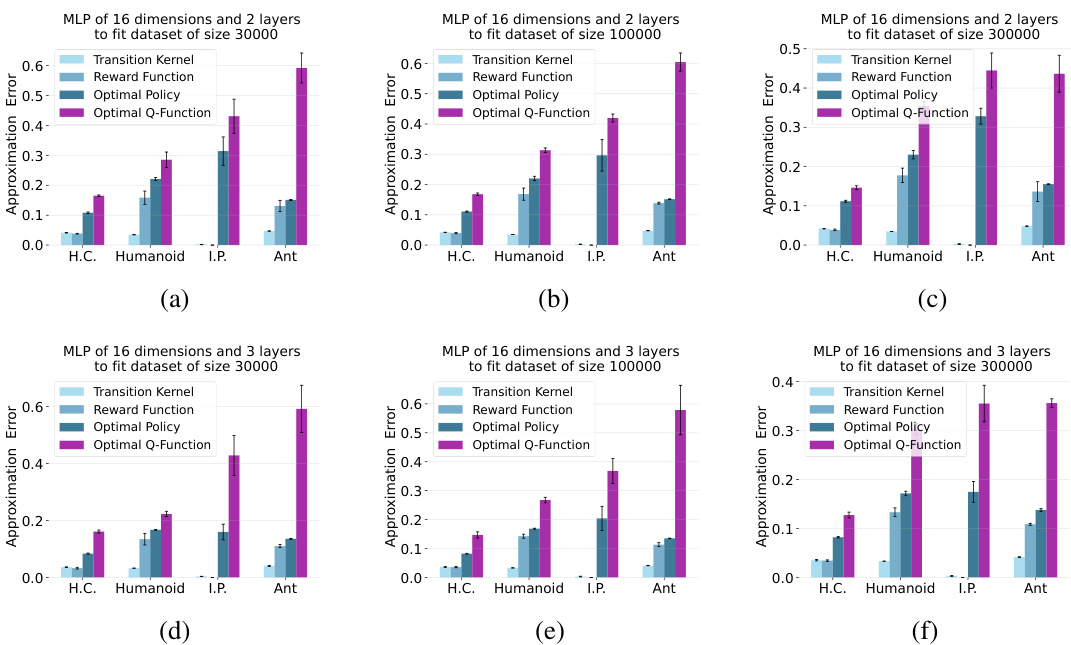

This figure shows the approximation errors when using MLPs with different depths and widths to approximate the transition kernel, reward function, optimal policy, and optimal Q-function in four MuJoCo environments (HalfCheetah, Humanoid, InvertedPendulum, and Ant). Each subfigure represents a different MLP configuration (hidden dimensions, number of layers, and dataset size). The x-axis shows the environment, and the y-axis shows the approximation error. The figure visually demonstrates the relative difficulty of approximating each component (model, policy, and value function).

This figure shows the approximation errors of using MLPs with different depths and widths to approximate transition kernel, reward function, optimal policy, and optimal Q-function in four MuJoCo environments. The results are shown for three different dataset sizes and two different numbers of layers in the MLP. The approximation error is lower for the model and policy than the value function, confirming the findings of the paper.

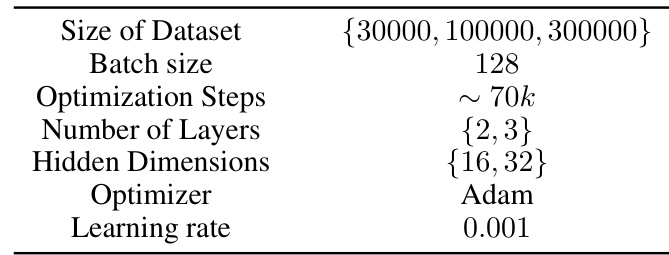

More on tables

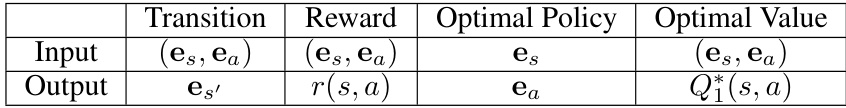

This table shows what input and output are used for training the MLPs for the model, policy, and value function. The input consists of state and action embeddings, and the outputs are the next state embedding, reward, optimal action embedding, and optimal Q-value, respectively. This is used to compare the representation complexity of each function type.

This table summarizes the main findings of the paper regarding the representation complexity of different RL paradigms (model-based, policy-based, and value-based RL) using log-precision MLPs with constant layers and polynomial hidden dimensions. It shows whether these MLPs can effectively represent the model, policy, and value function for each paradigm and highlights the complexity hierarchy uncovered in the study. The checkmark (✓) indicates representability, while the ‘X’ indicates non-representability. Blue and red colors visually represent low and high representation complexity, respectively.

This table summarizes the main findings of the paper regarding the representation complexity of different RL paradigms (model-based, policy-based, value-based) using computational complexity and the expressiveness of MLPs. It shows which RL paradigm’s function (model, policy, or value) can be easily represented with constant-layer MLPs with polynomial hidden dimensions, and which ones cannot.

Full paper#