↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems require transitioning between solutions incrementally, minimizing disruption. This is particularly relevant in dynamic settings such as disaster recovery or online content management where step-by-step changes are crucial. The paper explores this concept within computational social choice using multi-winner elections, focusing on how to smoothly transition between committees (subsets of alternatives). This problem, termed multi-winner reconfiguration, presents significant computational challenges.

The paper analyzes the complexity of multi-winner reconfiguration under four different approval-based voting rules. It finds that the problem exhibits computational intractability under some rules but polynomial solvability under others. Furthermore, a detailed parameterized complexity analysis is provided, highlighting the existence of efficient algorithms under specific conditions. These findings provide both theoretical insights and practical guidance for tackling real-world reconfiguration problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computational social choice and related fields. It introduces a novel framework for analyzing the complexity of transitioning between different solutions in dynamic systems, specifically focusing on multi-winner elections. The findings are significant for developing efficient algorithms for various applications dealing with dynamic system reconfigurations and provide a solid theoretical foundation for further research in this domain. The parameterized complexity analysis is particularly valuable for understanding the problem’s challenges under different computational resource constraints.

Visual Insights#

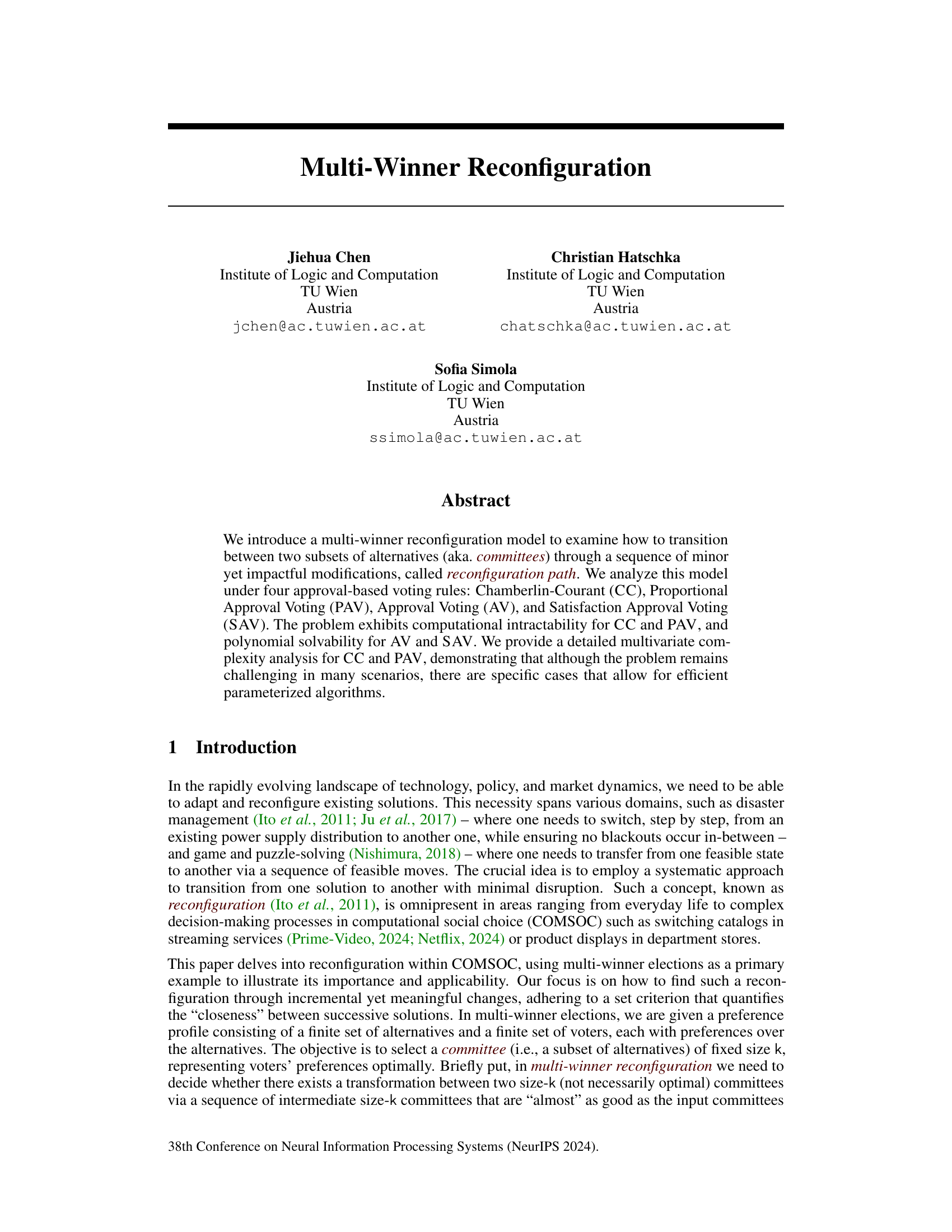

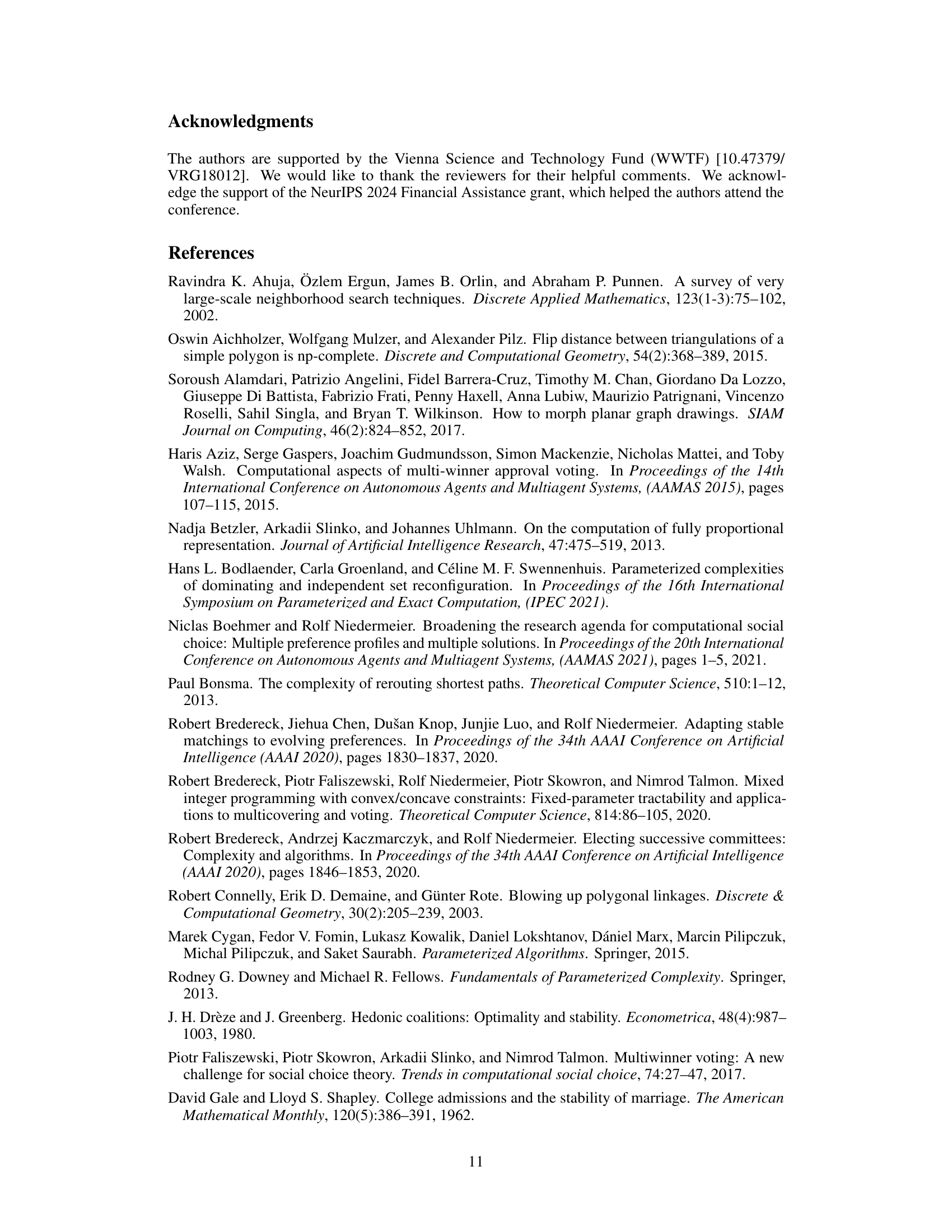

This figure is used in the proof of Lemma 1 in the paper. It illustrates two cases for constructing a reconfiguration path between two committees, W and W’, under the Chamberlin-Courant (CC) voting rule. The figure shows how to make incremental changes to the committee W to reach the committee W’, while maintaining a certain closeness criteria (d-adjacency) between consecutive committees in the sequence. Case 1 represents a scenario where the difference between W and W’ is large, and Case 2 represents a scenario where the difference is small. The colored regions show the sets of alternatives that are added, removed, or remain unchanged during the transitions between committees.

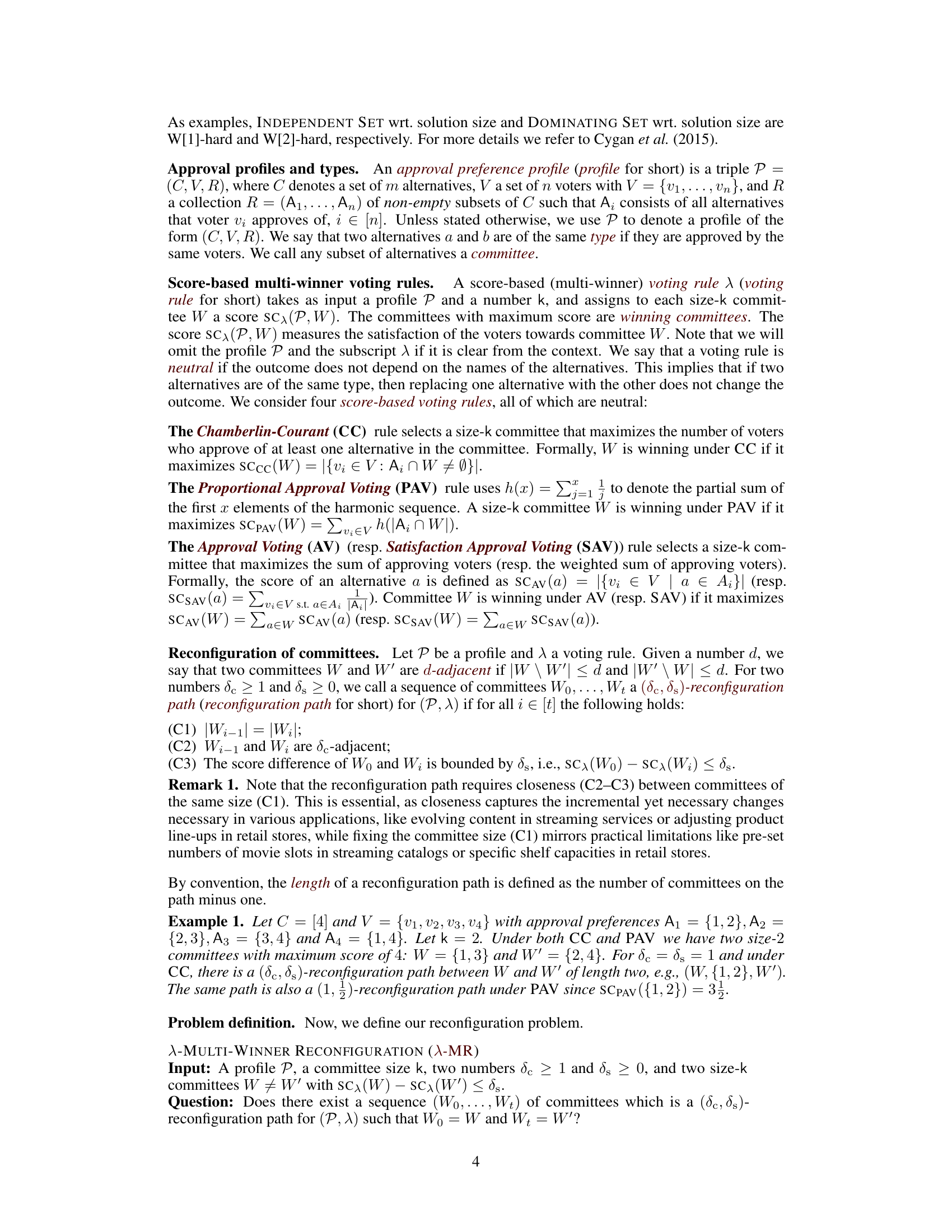

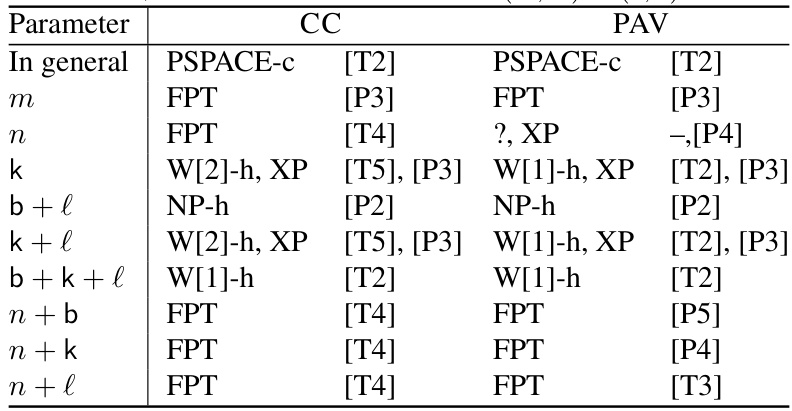

This table summarizes the computational and parameterized complexity results for the multi-winner reconfiguration problem under four different voting rules (Chamberlin-Courant, Proportional Approval Voting, Approval Voting, and Satisfaction Approval Voting). It shows the complexity (PSPACE-complete, FPT, XP, NP-hard, W[1]-hard, W[2]-hard) based on different parameters (number of alternatives, voters, committee size, maximum number of approved alternatives per voter, length of shortest reconfiguration path). Results for Approval Voting and Satisfaction Approval Voting are omitted as they are polynomial-time solvable.

In-depth insights#

Multi-Winner Reconfig#

The heading “Multi-Winner Reconfiguration” suggests a research area focusing on the dynamic reallocation of resources or positions among multiple winners. It likely involves scenarios where an initial allocation exists and needs to transition to a different allocation through a series of smaller, incremental changes. The “multi-winner” aspect implies a setting where multiple entities or candidates are involved. The reconfiguration process likely seeks optimality, perhaps aiming for minimal disruption or cost during the transition. This could involve applications in diverse fields like resource allocation, committee formation, or political transitions. The research likely explores the computational complexity of finding optimal or near-optimal reconfiguration paths, potentially identifying efficient algorithms or heuristics for practical scenarios. Approaches might utilize graph-based models or parameterized complexity analyses to tackle the problem. The work likely contributes valuable theoretical insights and practical methodologies for managing dynamic resource allocation and committee assignments.

Complexity Analysis#

The complexity analysis section of a research paper is crucial for evaluating the feasibility and scalability of proposed algorithms or models. A thorough analysis would typically investigate the time and space complexity, often using Big O notation to express how the resource requirements scale with the size of the input. Computational complexity classes, such as P, NP, and PSPACE, would be used to categorize the problem’s inherent difficulty. Parameterized complexity may also be explored, analyzing the runtime’s dependence on specific parameters, leading to FPT (fixed-parameter tractable) or W[i]-hard results. For multi-winner reconfiguration problems, the analysis is particularly important because the space of possible solutions can be large, and the process of finding optimal or near-optimal solutions is challenging. Different voting rules would have different complexities associated with them, some showing polynomial-time solvability while others exhibit NP-hardness or even PSPACE-completeness. The paper likely details trade-offs between computational cost and solution quality, possibly highlighting scenarios where efficient algorithms exist. A good analysis identifies limitations, suggesting avenues for future research to improve efficiency. Parameterized results, focusing on key parameters like the number of alternatives, voters, or committee size, provide crucial insight into when efficient solutions might be possible.

Algorithmic Results#

The Algorithmic Results section would ideally present a detailed analysis of the algorithms used to solve the multi-winner reconfiguration problem. This would include a discussion of the algorithms’ time and space complexity, focusing on their scalability with respect to key problem parameters (number of alternatives, voters, committee size, etc.). Crucially, the runtime analysis should consider different voting rules (CC, PAV, AV, SAV), highlighting where efficient algorithms exist and where computational intractability arises. The section should also examine the effectiveness of any parameterized algorithms, specifying the parameters used and the resulting complexity classes (FPT, XP, W[1]-hard, etc.). A comparison of the algorithmic performance of different approaches across various parameter settings would be beneficial, showcasing the practical implications of the theoretical complexity analysis. Finally, a discussion on the trade-offs between different algorithmic approaches in terms of efficiency and solution quality would add valuable insight, possibly presenting experimental evidence to support the theoretical findings.

Reconfiguration Paths#

The concept of “Reconfiguration Paths” in the context of multi-winner elections offers a novel perspective on transitioning between different winning committees. It moves beyond simply identifying optimal committees to explore the process of incremental change, examining how to smoothly shift from one winning set to another through a sequence of intermediate committees. This approach is particularly relevant in dynamic environments where abrupt changes are undesirable. The computational complexity analysis associated with finding these paths under various voting rules highlights the challenging nature of this problem. The theoretical analysis reveals a range of complexities, from polynomial solvability to PSPACE-completeness, depending on the specific voting rule employed and the parameters involved. The study also introduces parameterized algorithms to address the computational challenges in specific scenarios. The practical implications of this framework extend beyond theoretical analysis, demonstrating its applicability in real-world scenarios such as optimizing streaming service catalogs or product displays, where maintaining user satisfaction during transitions is crucial.

Future Research#

The “Future Research” section of this paper would ideally explore several promising avenues. Extending the reconfiguration framework to non-score-based rules is crucial, perhaps by adapting the closeness measure or focusing on paths between winning committees only. Investigating the parameterized complexity for PAV with respect to n remains a key open question. The development of efficient heuristics and approximation algorithms for CC and PAV is warranted, given their computational intractability in many scenarios. Empirical research should delve deeper into real-world data, considering different data distributions and committee sizes, to determine the effectiveness of the proposed algorithms and heuristics in practice. Finally, the application of this framework to other social choice problems like fair division and coalition formation could unlock valuable insights, expanding the framework’s influence beyond multi-winner elections.

More visual insights#

More on figures

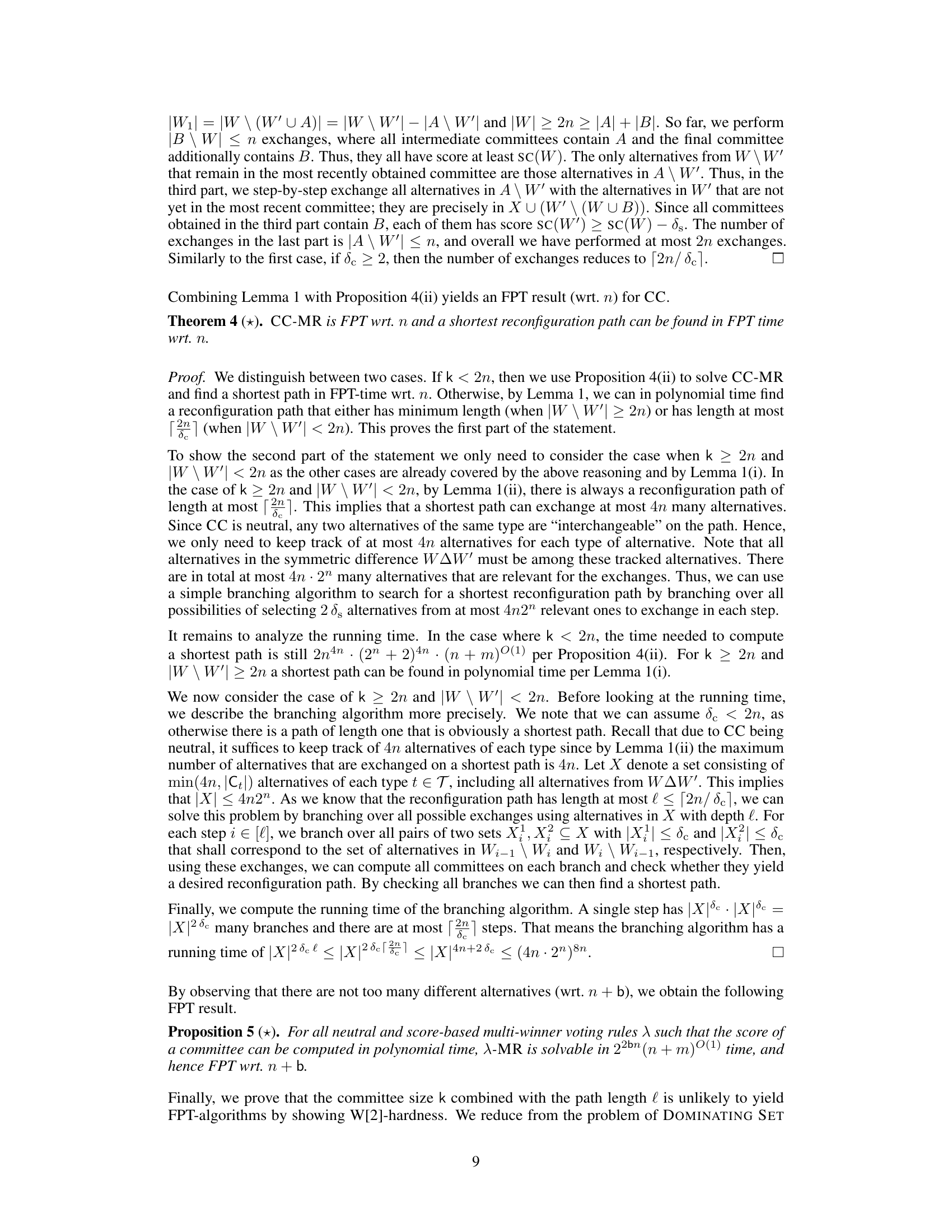

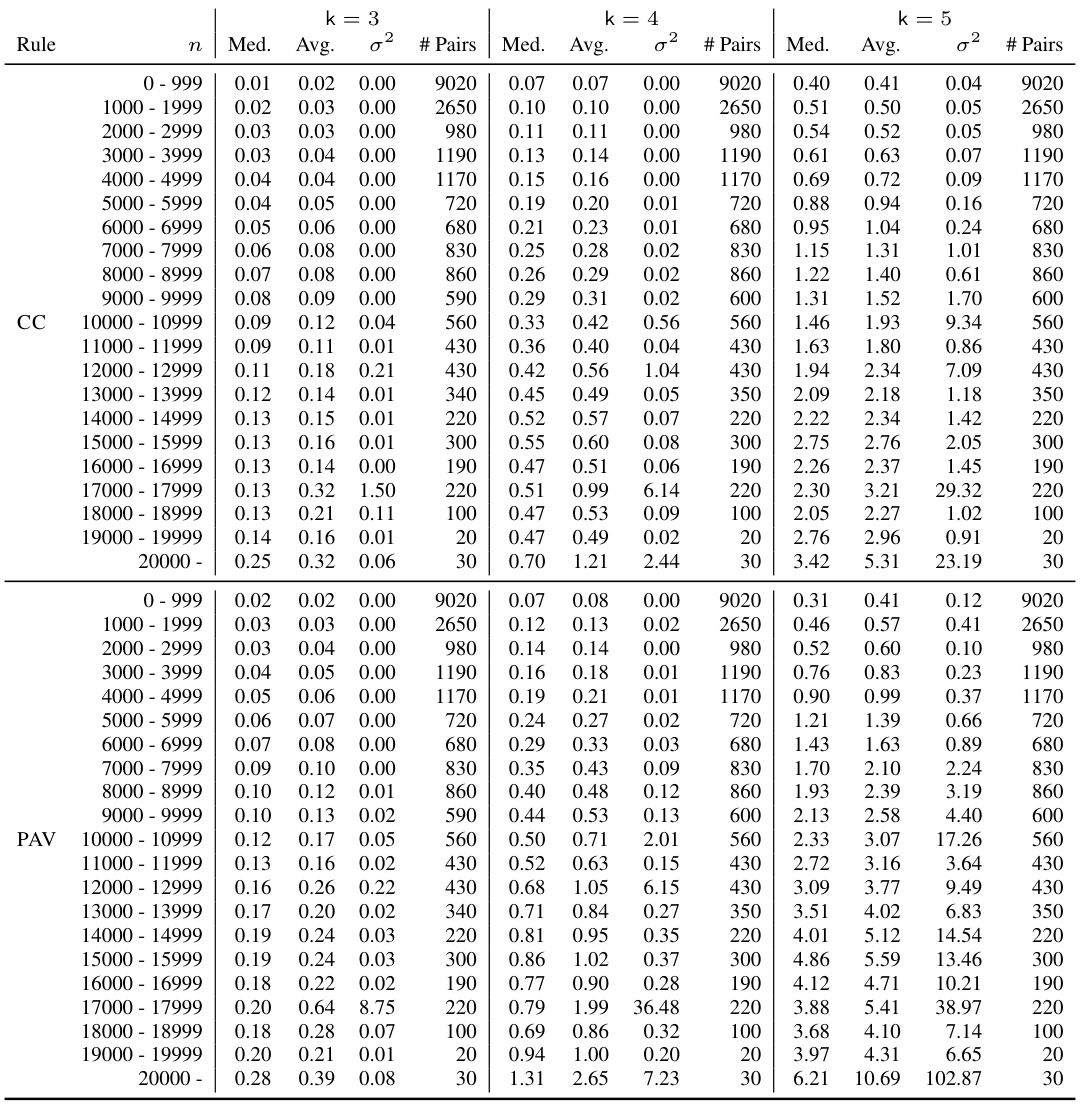

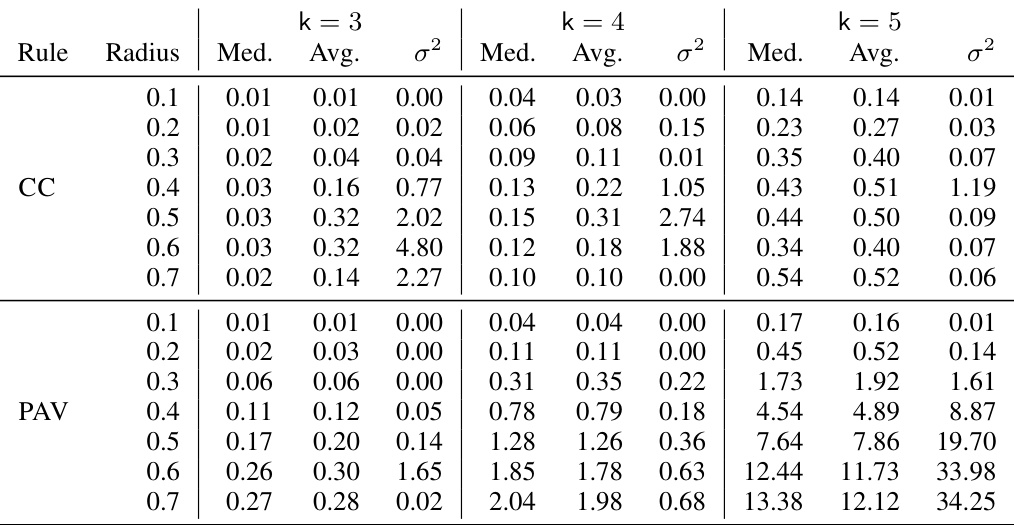

The left subplot shows the median running time (in seconds) to find a reconfiguration path plotted against the number of voters for Netflix data. Different colors represent different committee sizes (k=3, 4, 5) for both Chamberlin-Courant (CC) and Proportional Approval Voting (PAV) rules. The right subplot shows the same median running time but this time plotted against the radius of the Manhattan data, again showing different colors for different committee sizes and voting rules.

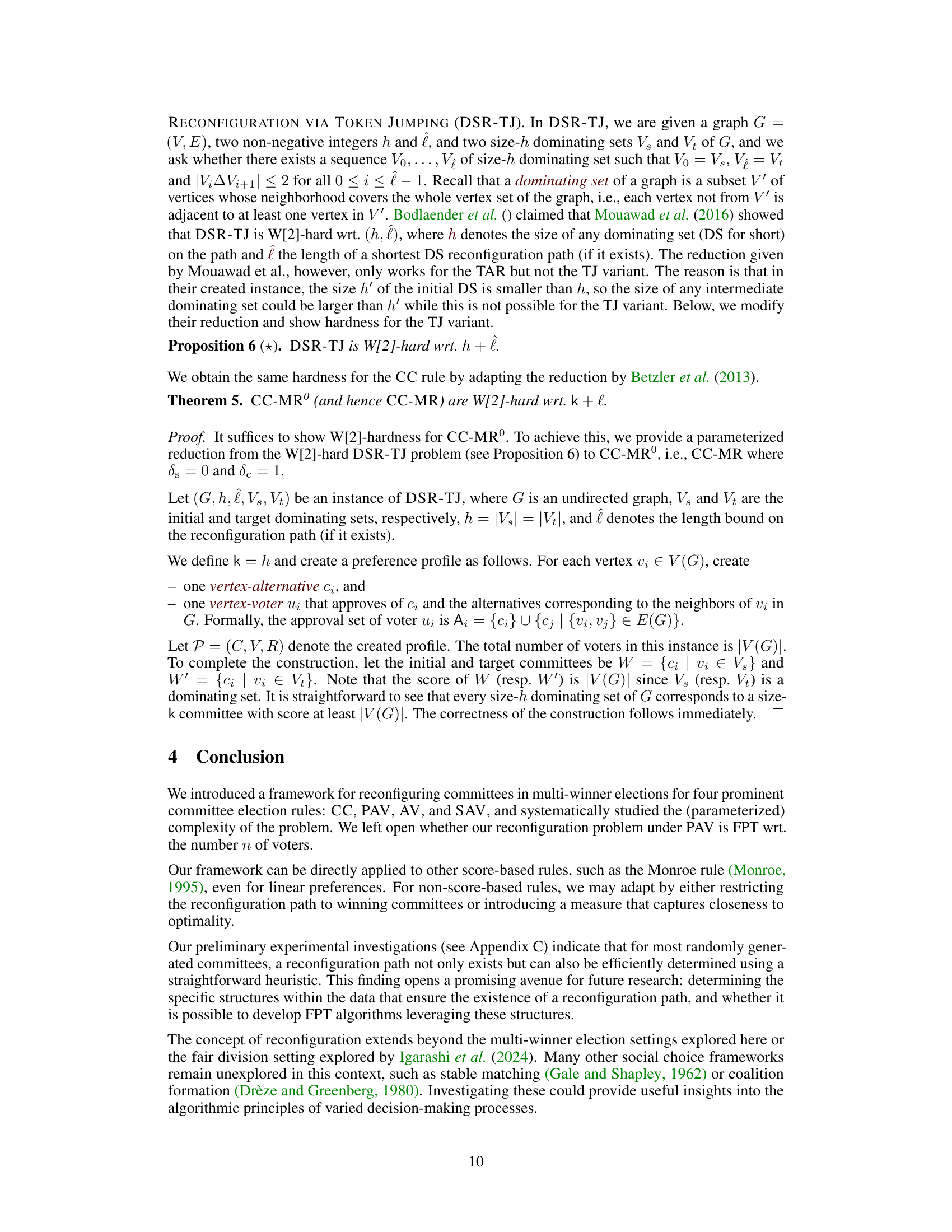

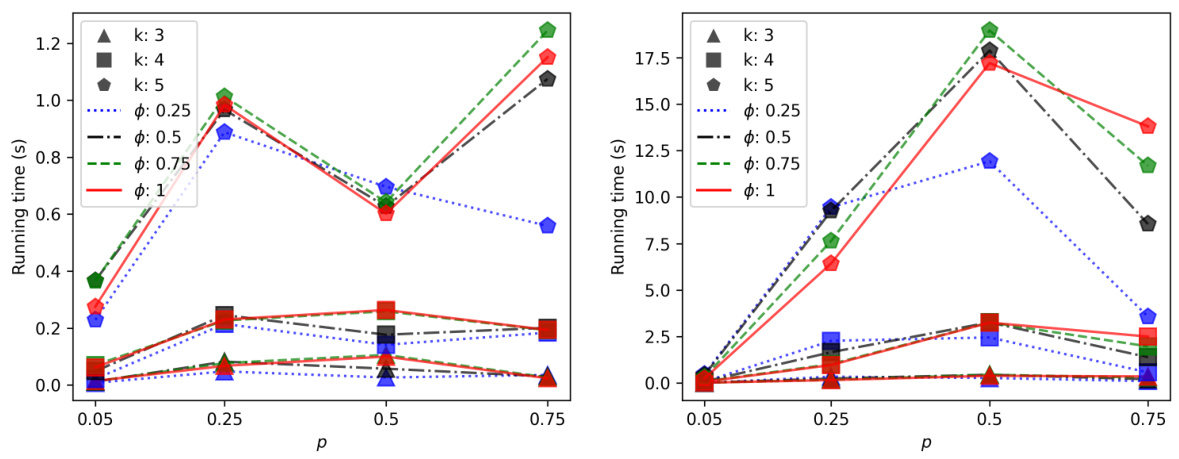

This figure shows the median running time to find a reconfiguration path using two different multi-winner voting rules (Chamberlin-Courant and Proportional Approval Voting) under different parameter settings. The x-axis represents the approval probability (p), and different lines represent different values of dissimilarity (φ) and different committee sizes (k). Each point represents the median running time across multiple trials. The figure demonstrates how the running time varies with different probability parameters and voting rules.

More on tables

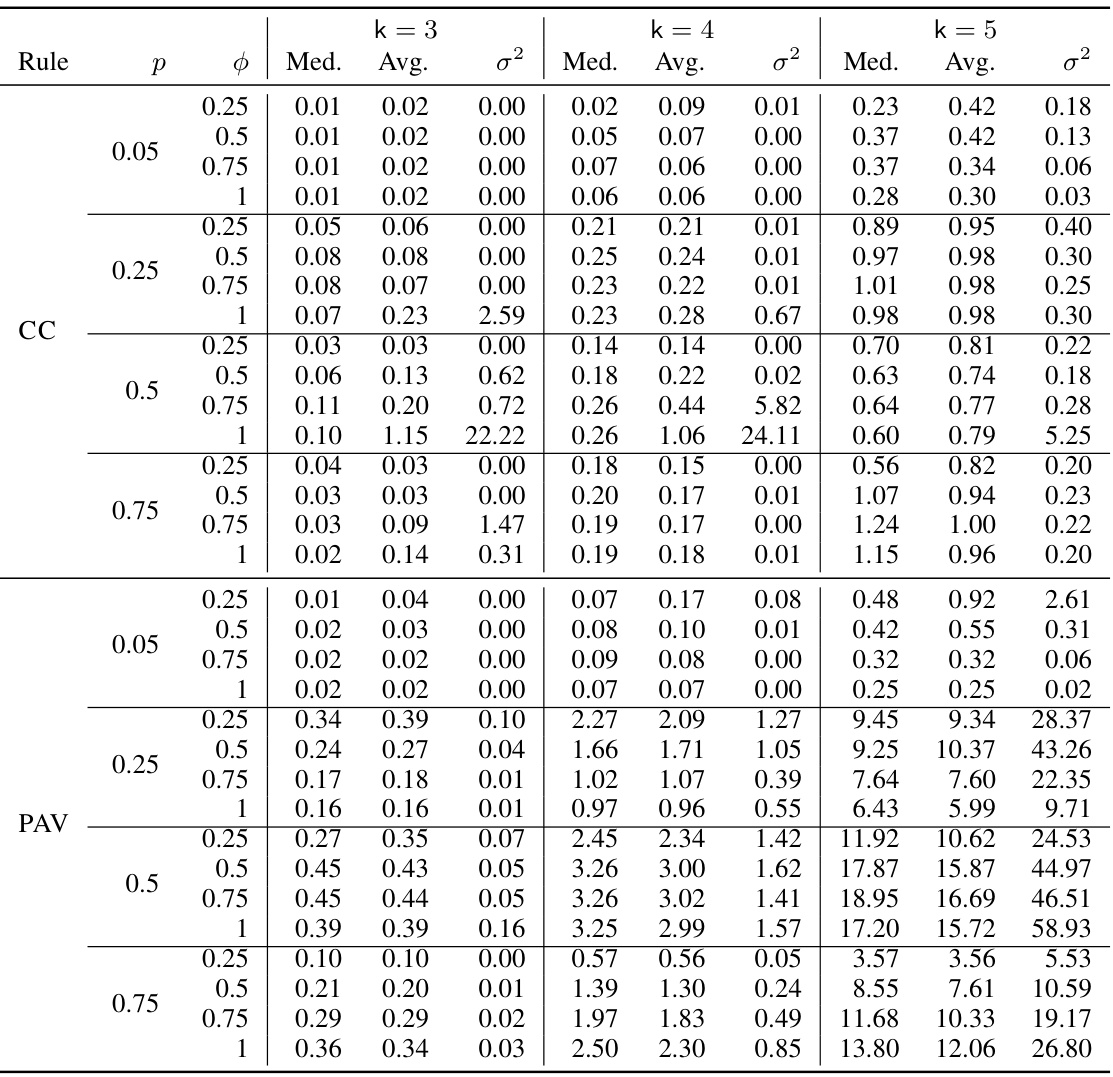

This table summarizes the parameterized complexity results for the multi-winner reconfiguration problem under four different voting rules (Chamberlin-Courant, Proportional Approval Voting, Approval Voting, and Satisfaction Approval Voting). It shows the complexity (FPT, XP, W[1]-hard, W[2]-hard, PSPACE-complete) with respect to several parameters, including the number of alternatives (m), voters (n), committee size (k), maximum number of approved alternatives per voter (b), and the length of the shortest reconfiguration path (l). The table highlights that while the problem is computationally intractable for Chamberlin-Courant and Proportional Approval Voting in the general case, Approval Voting and Satisfaction Approval Voting are solvable in polynomial time. For Chamberlin-Courant and Proportional Approval Voting, the table details the parameterized complexity based on different combinations of parameters, revealing specific scenarios allowing for efficient parameterized algorithms.

This table summarizes the parameterized complexity results for the multi-winner reconfiguration problem under different voting rules (Chamberlin-Courant and Proportional Approval Voting). It shows the complexity (e.g., FPT, XP, W[1]-hard, W[2]-hard, PSPACE-complete) based on various parameters such as the number of alternatives (m), the number of voters (n), the committee size (k), the maximum number of approved alternatives per voter (b), and the length of the shortest reconfiguration path (l). The results highlight the computational intractability for Chamberlin-Courant and PAV, contrasting with the polynomial solvability for Approval Voting and Satisfaction Approval Voting. The table also specifies the conditions under which the hardness results hold.

This table summarizes the parameterized complexity results for the multi-winner reconfiguration problem under the Chamberlin-Courant (CC) and Proportional Approval Voting (PAV) rules. It shows the complexity of the problem with respect to various parameters: the number of alternatives (m), the number of voters (n), the committee size (k), the maximum number of approved alternatives per voter (b), and the length of the shortest reconfiguration path (l). The table indicates whether the problem is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT), in XP, or hard for certain complexity classes (e.g., NP-hard, W[1]-hard, W[2]-hard, PSPACE-complete) for each parameter combination. Approval Voting (AV) and Satisfaction Approval Voting (SAV) are omitted because they are polynomially solvable.

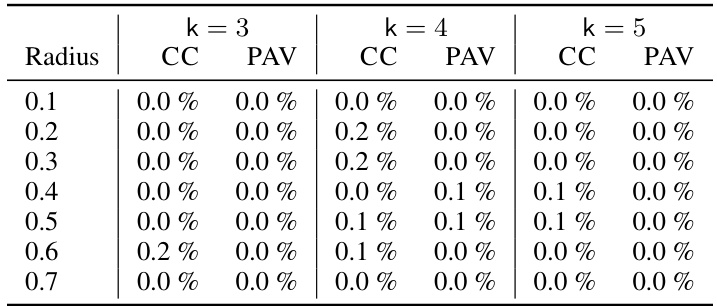

This table shows the percentage of committee pairs that exceeded the 60-second timeout limit for the Manhattan dataset, categorized by the radius (distance between voters and alternatives), committee size (k), and voting rule (CC or PAV). A higher percentage indicates more computational difficulty in finding a reconfiguration path within the time constraint.

This table presents a summary of the computational and parameterized complexity results for the multi-winner reconfiguration problem under four different voting rules (Chamberlin-Courant, Proportional Approval Voting, Approval Voting, and Satisfaction Approval Voting). It shows whether the problem is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) or W[i]-hard for various parameters (number of alternatives, voters, committee size, maximum number of approved alternatives per voter, and path length), indicating the problem’s difficulty depending on these factors. The results highlight the contrast between the computationally hard cases for Chamberlin-Courant and Proportional Approval Voting and the easy cases for Approval Voting and Satisfaction Approval Voting.

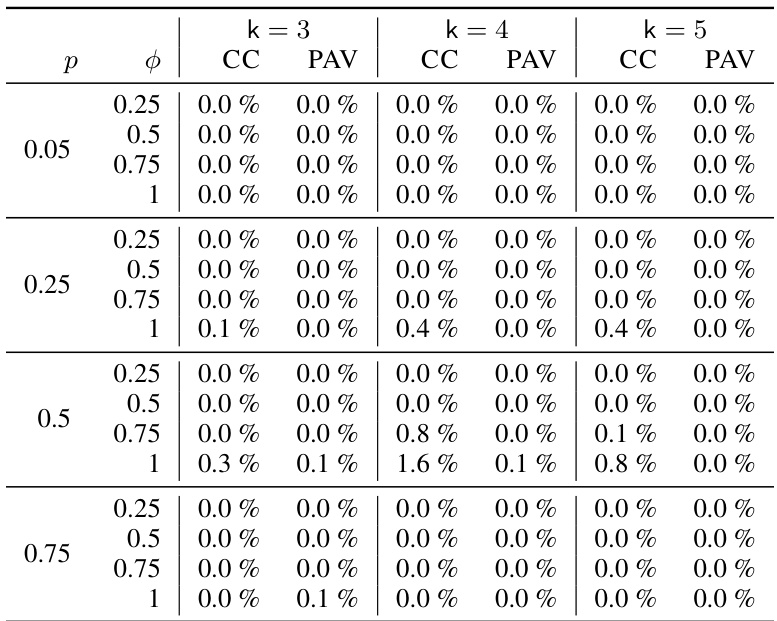

This table shows the percentage of committee pairs that timed out (took longer than 60 seconds to find a reconfiguration path) for different ranges of the number of voters (n) and for different committee sizes (k=3, 4, 5) under both CC and PAV voting rules. The data highlights the impact of the number of voters and committee size on the computation time for finding reconfiguration paths.

Full paper#