TL;DR#

Many real-world prediction problems involve scenarios where confidently making predictions is challenging and costly. The classical EXP4 algorithm, which is frequently used in such scenarios, doesn’t account for this. Consequently, it often leads to suboptimal decisions, resulting in accumulated losses. This paper introduces the problem of prediction with expert advice under bandit feedback, specifically focusing on scenarios where abstaining from making a prediction is an option. The existing approaches have limitations in handling this abstention efficiently.

The paper proposes a novel algorithm called Confidence-Rated Bandits with Abstentions (CBA). CBA specifically incorporates the abstention action, leading to significantly improved reward bounds compared to EXP4. The researchers demonstrate the effectiveness of CBA both theoretically through improved regret bounds and experimentally on various datasets. Furthermore, they extend CBA to address the complex problem of adversarial contextual bandits, showcasing its applicability across different contexts and its superior performance over previous methods. CBA also achieves a runtime reduction for certain types of data, making it more efficient for high-dimensional problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves the classical EXP4 algorithm for prediction with expert advice under bandit feedback by incorporating an abstention action. This advance has theoretical implications in improving reward bounds and practical applications in adversarial contextual bandits, particularly in scenarios with high-dimensional or complex data where abstention is crucial.

Visual Insights#

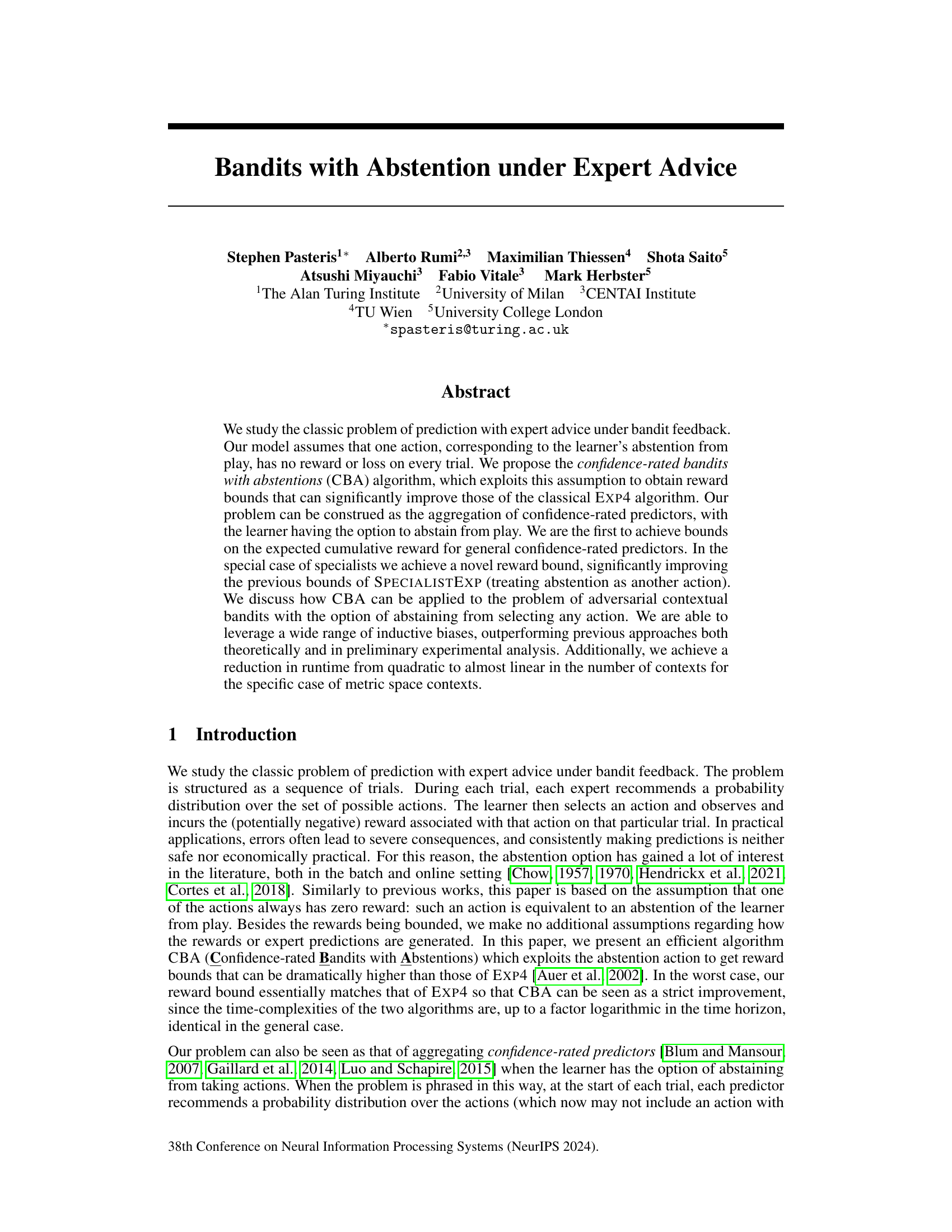

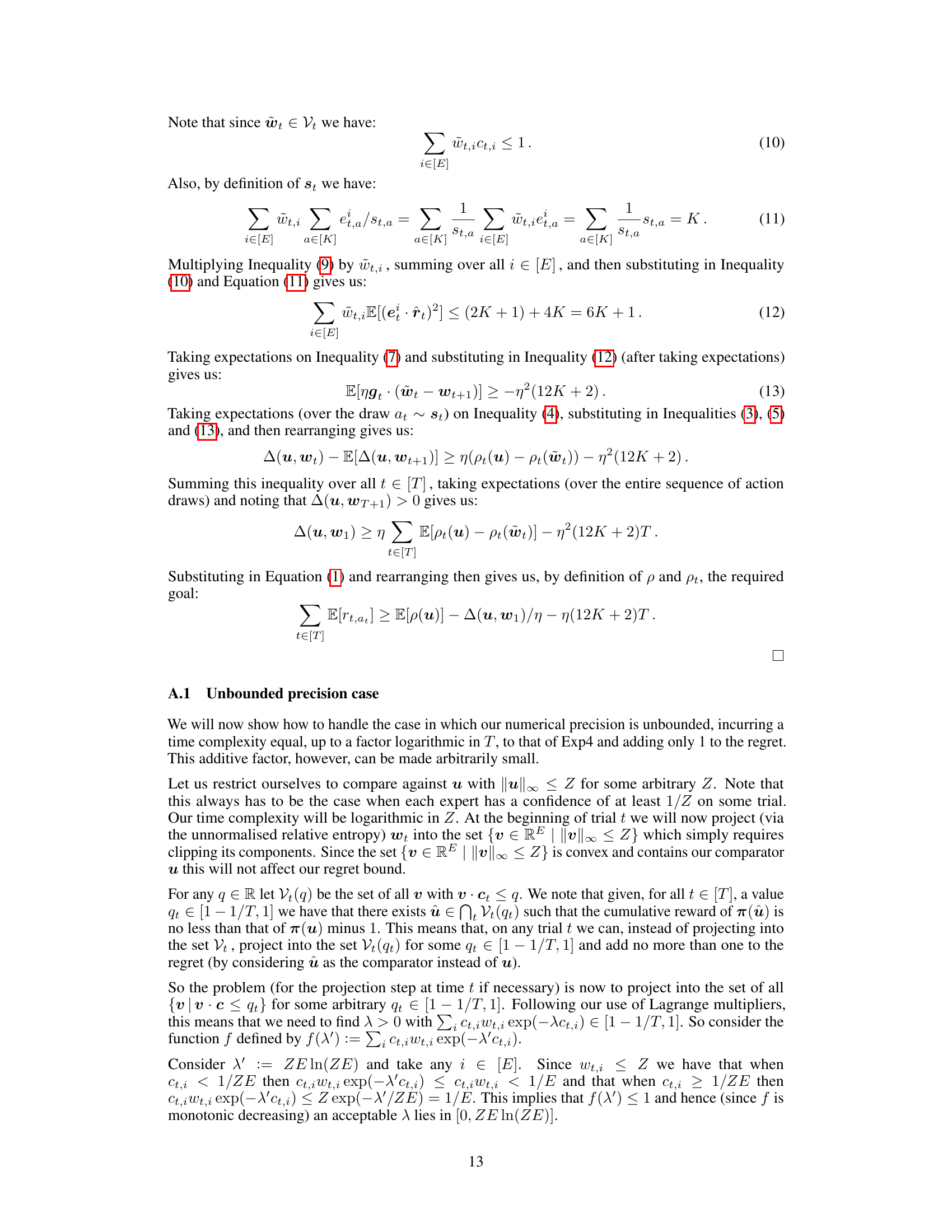

🔼 This figure illustrates the advantage of using abstention in contextual bandits. It shows two scenarios: one where abstention allows efficient coverage of foreground classes with fewer balls, and another where treating the background as a class requires significantly more balls. This highlights how abstention improves reward bounds.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustrative example of abstention where we cover the foreground and background classes with metric balls. We consider two clusters (blue and orange) as the foreground and one background class (white), using the shortest path do metric. Using abstention, we can cover two clusters with one ball for each and abstain the background with no balls required (Fig. 1(a)). In contrast, if we treat the background class as another class, it would require significantly more balls to cover the background class, as seen by the 10 gray balls in Fig. 1(b). If the number of balls to cover significantly increases like in this case, the bound involving the number of balls also gets significantly worse.

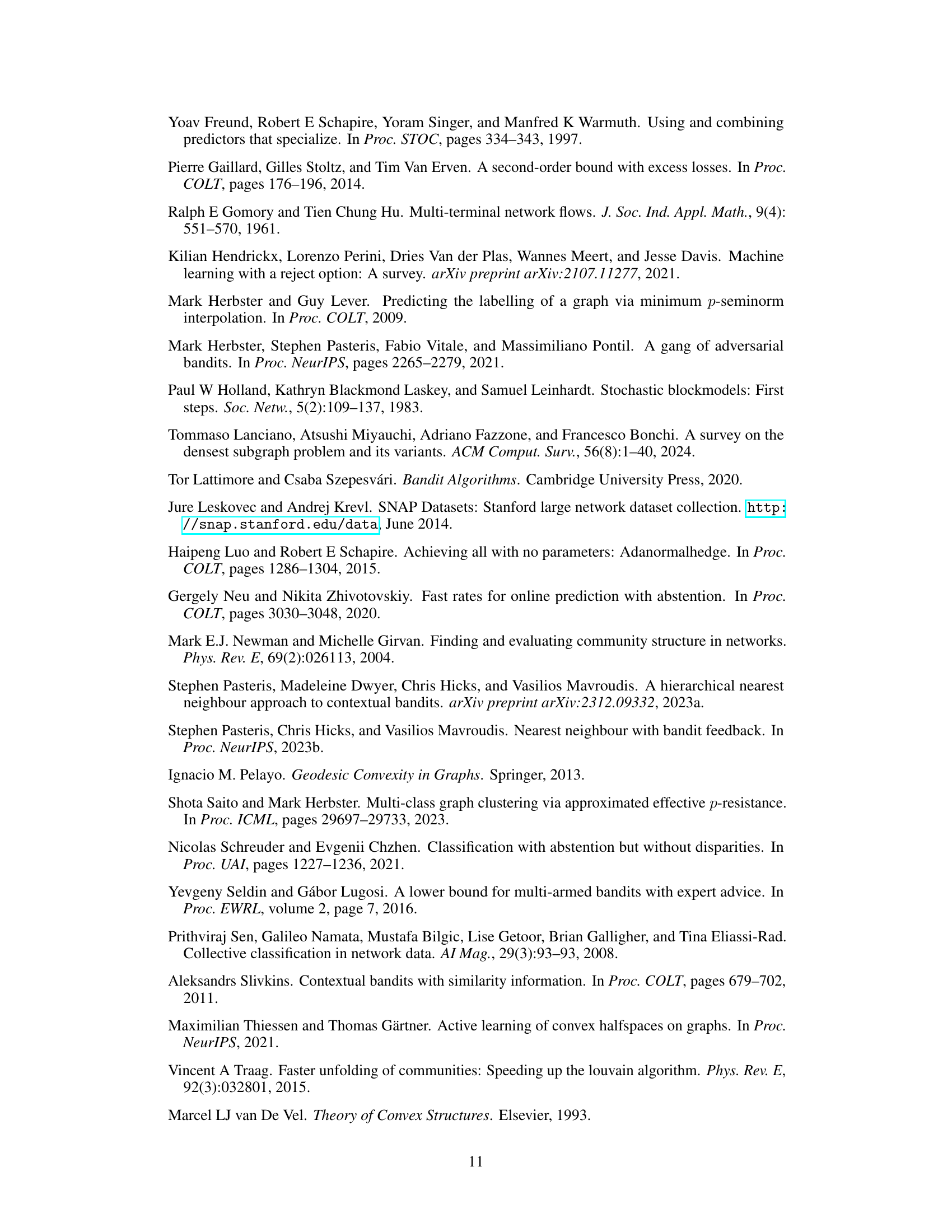

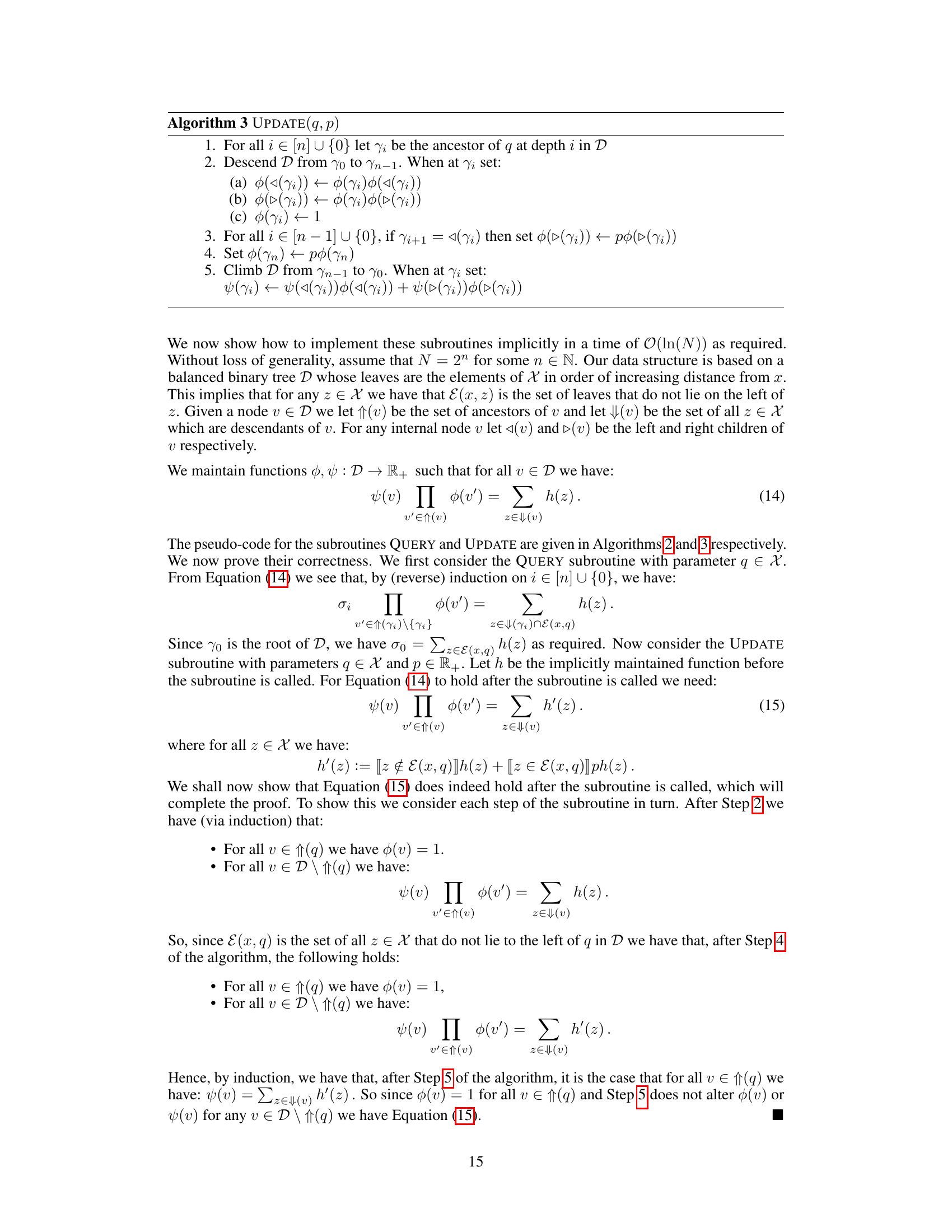

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments using the Stochastic Block Model. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents the number of mistakes made. Multiple lines are shown, with dotted lines representing different baseline algorithms and solid lines representing the results of the proposed CBA algorithm using different basis functions. The variations in the solid lines demonstrate the impact of different basis choices on the algorithm’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: Stochastic Block Model results, dotted lines represent different baselines, while solid lines are used to represent various results.

In-depth insights#

Abstention Bandits#

Abstention bandits represent a compelling extension of classic multi-armed bandit problems. The core innovation lies in allowing the learning agent to abstain from making a decision on any given trial, rather than being forced to select an action with potentially negative consequences. This abstention option introduces significant strategic considerations, requiring the algorithm to balance exploration (learning about rewards) with exploitation (choosing the best action) and the strategic use of abstention (avoiding losses by inaction). The introduction of abstention changes the regret calculation substantially, moving beyond simple comparisons against always-choosing policies and into scenarios where abstention itself has value. Analyzing the regret necessitates considering the tradeoffs between the expected rewards of actions, the costs associated with incorrect action choices, and the benefits derived from the intelligent use of abstention. Effective algorithms for abstention bandits must learn not only the value of different actions but also when to refrain from acting entirely. This often involves learning complex probability distributions over actions and carefully managing confidence levels, which can influence whether abstention or an action is the better option. The problem’s difficulty lies in finding optimal strategies that are robust to uncertainty about rewards and adept at discerning when the ‘cost of choosing’ outweighs the ‘benefit of playing’.

CBA Algorithm#

The Confidence-Rated Bandits with Abstentions (CBA) algorithm represents a novel approach to the classic prediction problem with expert advice under bandit feedback. Its key innovation lies in explicitly incorporating an abstention action, which incurs zero reward or loss, allowing the algorithm to strategically avoid making predictions when confidence is low. This abstention capability is leveraged to derive significantly improved reward bounds compared to the classical EXP4 algorithm. The algorithm’s design incorporates elements of mirror descent, but with a crucial modification: it uses an unbiased estimator of the gradient, inspired by the EXP3 algorithm, and projects the weight vector into a feasible set at each trial. This projection step ensures that the algorithm always generates valid probability distributions over actions, including the abstention option. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that CBA achieves strong regret bounds, particularly outperforming previous methods when dealing with confidence-rated predictors. Furthermore, CBA’s adaptability allows its application to the more challenging setting of adversarial contextual bandits, where it shows promise for improving both theoretical and empirical performance.

Contextual Bandits#

Contextual bandits extend the classic multi-armed bandit problem by incorporating contextual information available at each decision point. This adds significant complexity as the optimal action becomes context-dependent, requiring the algorithm to learn a policy that maps contexts to actions. Effective algorithms must balance exploration (trying different actions in various contexts to learn their value) and exploitation (choosing the seemingly best action given current knowledge). The challenge lies in efficiently learning the optimal policy in a dynamic environment with potentially noisy or adversarial feedback. Common approaches involve leveraging function approximation or representation learning to generalize across contexts, often relying on techniques like linear models, neural networks, or decision trees. The performance of contextual bandit algorithms is evaluated through metrics like cumulative regret (the difference between the rewards obtained and the rewards of an optimal policy). Applications are widespread, encompassing personalized recommendations, online advertising, clinical trials, and resource allocation.

Metric Space#

The concept of ‘Metric Space’ in the context of a research paper likely involves the application of distance metrics to analyze and model relationships between data points. This is particularly relevant in machine learning where algorithms often rely on notions of similarity and proximity. Metric spaces allow for the formalization of these concepts, providing a mathematical framework for measuring distances and applying algorithms designed for such spaces. Different distance metrics (Euclidean, Manhattan, etc.) can capture distinct notions of proximity, influencing the outcome of algorithms dependent on distance computations. The choice of metric is crucial and depends on the nature of the data and the task at hand. In the context of a research paper, the discussion of ‘Metric Space’ might involve a theoretical analysis of an algorithm’s performance in various metric spaces or a comparison of different metrics on a specific dataset. This could include analysis of the algorithm’s computational efficiency in different metric spaces or how the choice of metric can impact the generalizability of the model. Overall, a detailed treatment of ‘Metric Space’ would showcase the algorithm’s robustness and effectiveness across a range of data characteristics.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on bandits with abstention under expert advice could explore several avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to incorporate more complex reward structures and settings beyond the basic adversarial contextual bandit framework would be valuable. This could involve examining settings with delayed rewards, partial feedback, or non-stationary environments. Another promising direction would be to develop more sophisticated algorithms that can adapt to different types of inductive biases expressed through the choice of basis functions. This might involve the design of adaptive algorithms that automatically learn and leverage the most effective basis for a given task. Investigating the empirical performance of the proposed CBA algorithm on a wider range of real-world datasets and applications is also crucial to establishing its practical utility. Finally, a thorough exploration of the trade-offs between the computational cost of the algorithm and the quality of the obtained reward bounds would help in determining the most suitable settings for its deployment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

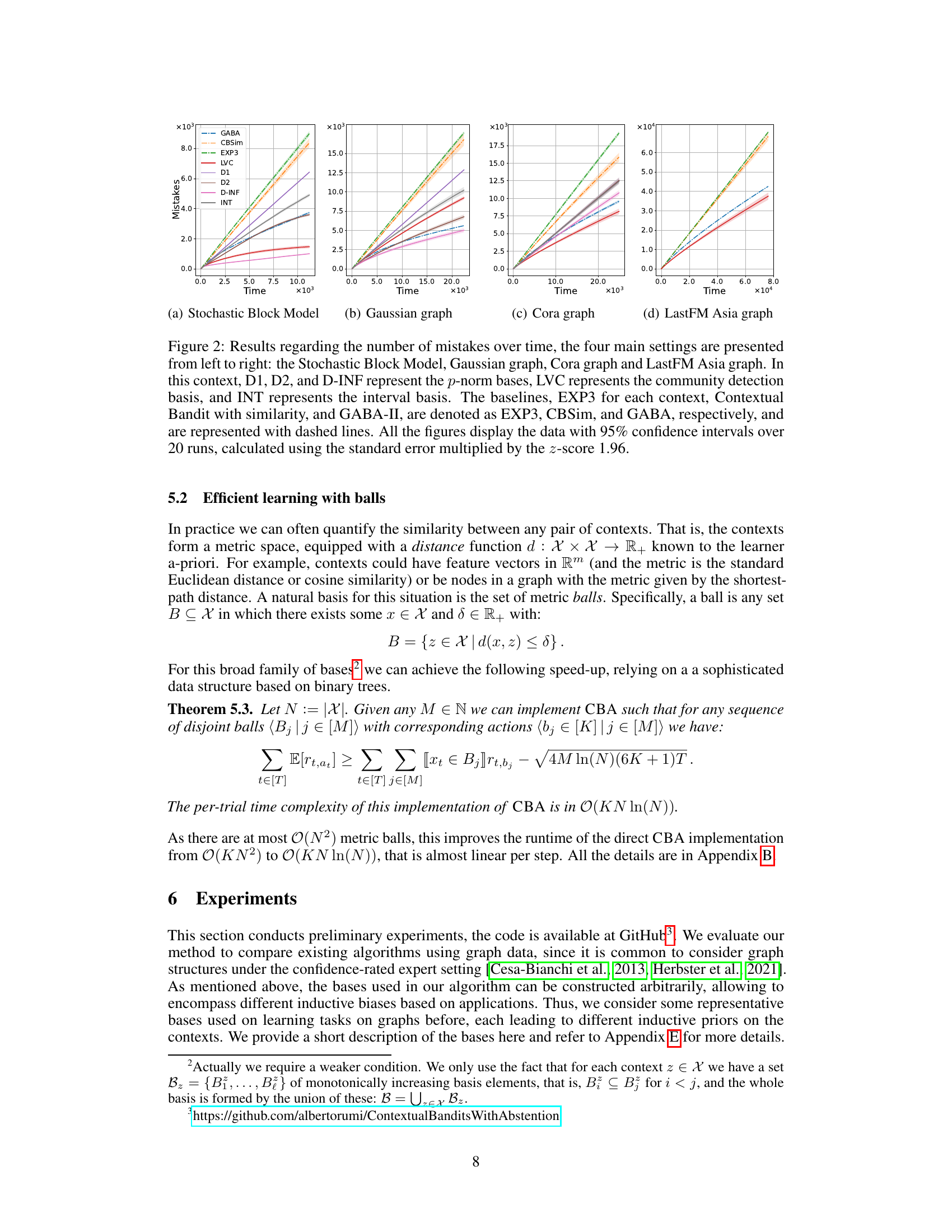

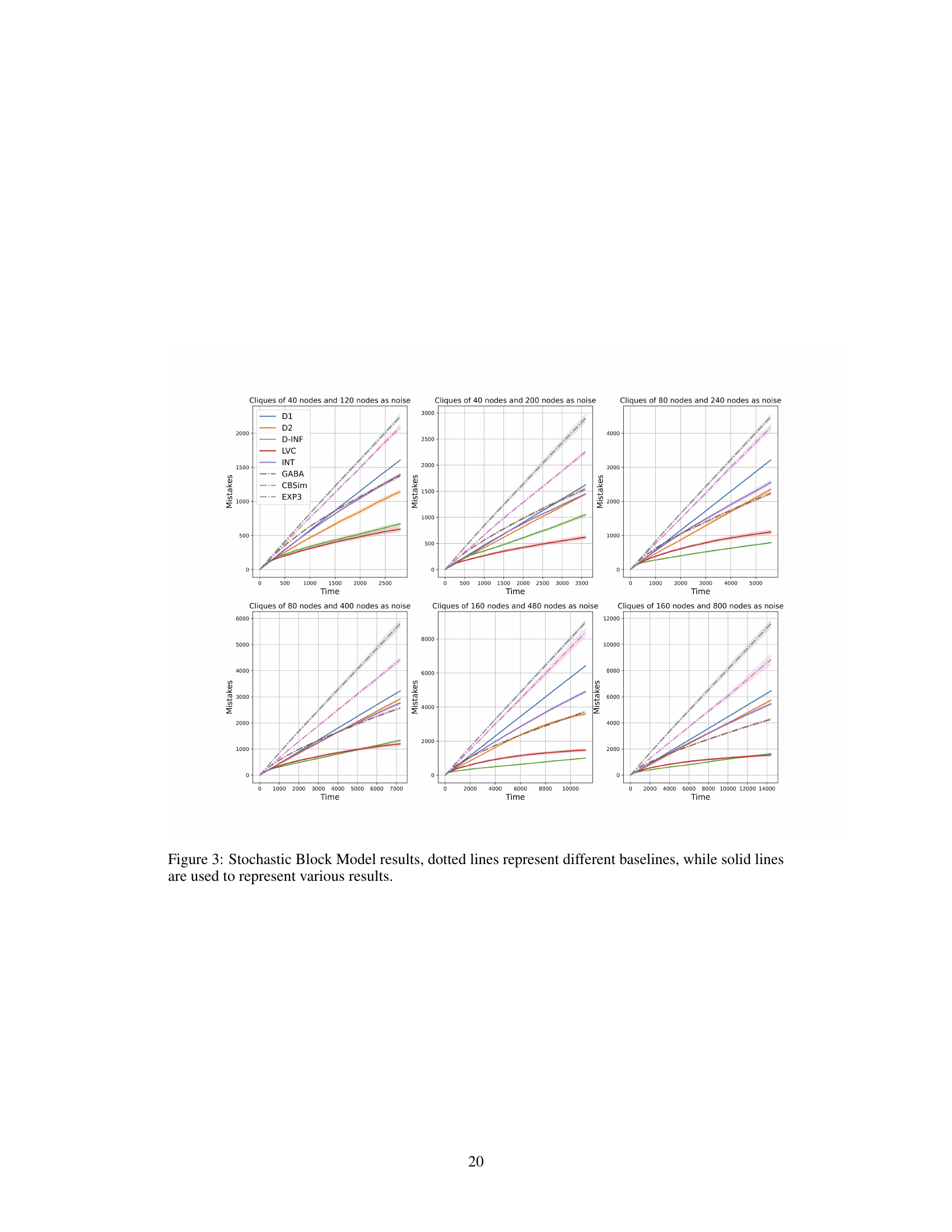

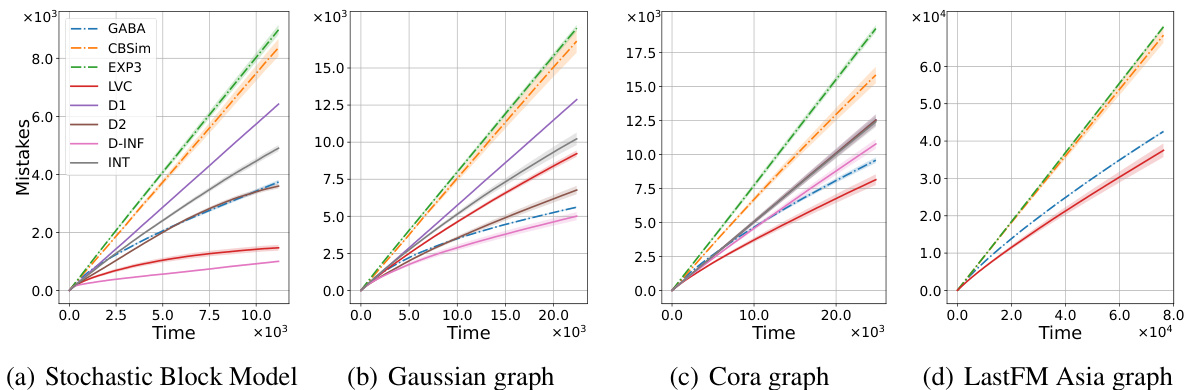

🔼 This figure displays the results of an experiment comparing the performance of several algorithms for contextual bandits with abstention on four different graph datasets. Each subplot shows the cumulative number of mistakes made by each algorithm over time. The algorithms are CBA with different basis functions (D1, D2, D-INF, LVC, INT), and three baselines (EXP3, CBSim, GABA). The different graph datasets represent varying levels of complexity and structure. Error bars are shown for 95% confidence intervals.

read the caption

Figure 2: Results regarding the number of mistakes over time, the four main settings are presented from left to right: the Stochastic Block Model, Gaussian graph, Cora graph and LastFM Asia graph. In this context, D1, D2, and D-INF represent the p-norm bases, LVC represents the community detection basis, and INT represents the interval basis. The baselines, EXP3 for each context, Contextual Bandit with similarity, and GABA-II, are denoted as EXP3, CBSim, and GABA, respectively, and are represented with dashed lines. All the figures display the data with 95% confidence intervals over 20 runs, calculated using the standard error multiplied by the z-score 1.96.

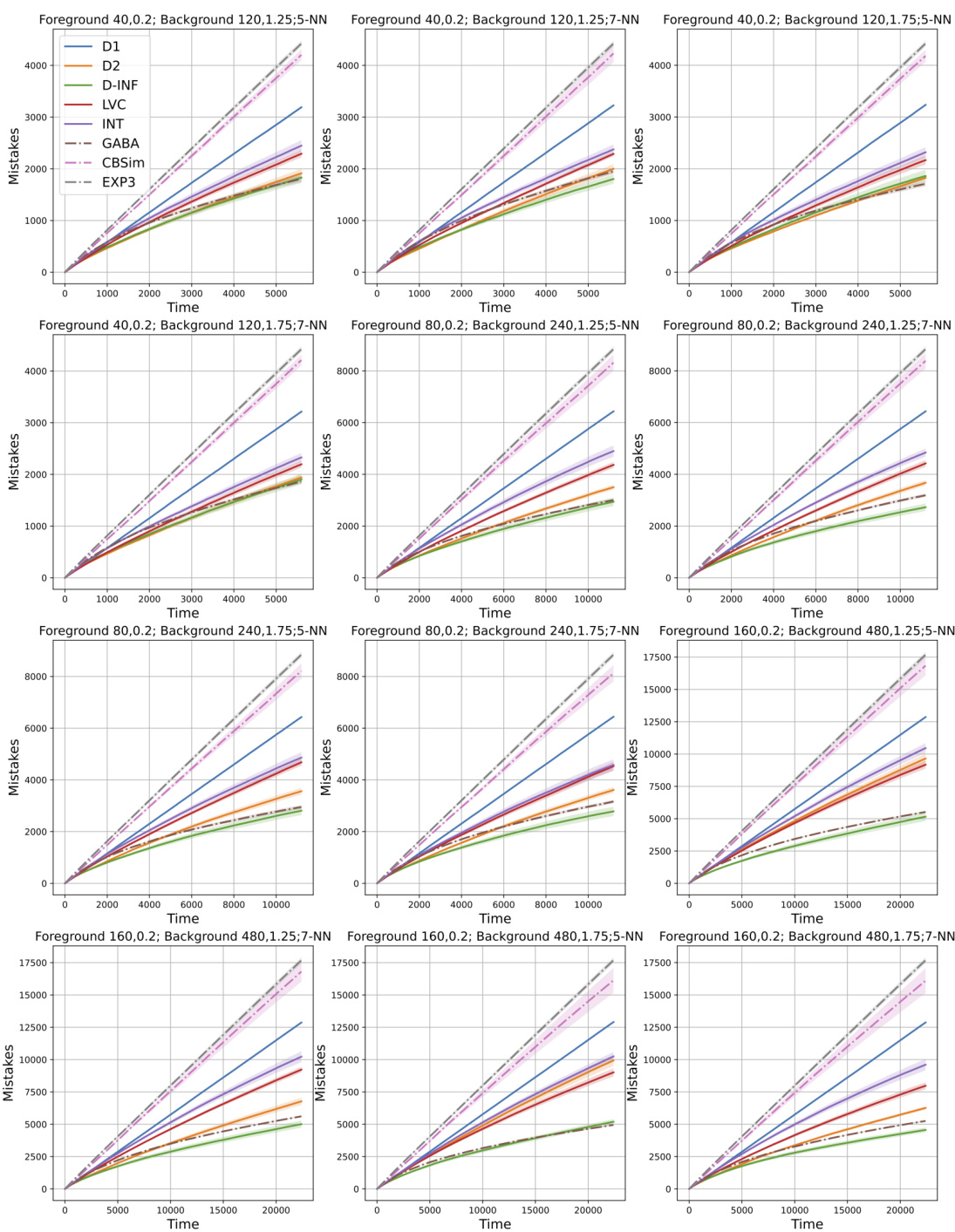

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments conducted using the Stochastic Block Model. It compares the performance of the CBA algorithm (solid lines) against several baseline algorithms (dotted lines) in terms of the number of mistakes made over time. Different line styles represent different algorithms (CBA with various bases and baselines). The plot shows that CBA consistently outperforms baseline algorithms, showcasing its effectiveness in the Stochastic Block Model setting.

read the caption

Figure 3: Stochastic Block Model results, dotted lines represent different baselines, while solid lines are used to represent various results.

🔼 The figure shows the performance of the CBA algorithm on four different graph datasets: Stochastic Block Model, Gaussian graph, Cora graph, and LastFM Asia graph. Four different baselines (EXP3, CBSim, GABA, and various p-norm, community detection, and interval bases) are compared against the CBA algorithm. The y-axis represents the number of mistakes, and the x-axis represents time. The results are shown with 95% confidence intervals across 20 runs. The figure demonstrates that the CBA algorithm outperforms baselines on all datasets when the appropriate basis is selected.

read the caption

Figure 2: Results regarding the number of mistakes over time, the four main settings are presented from left to right: the Stochastic Block Model, Gaussian graph, Cora graph and LastFM Asia graph. In this context, D1, D2, and D-INF represent the p-norm bases, LVC represents the community detection basis, and INT represents the interval basis. The baselines, EXP3 for each context, Contextual Bandit with similarity, and GABA-II, are denoted as EXP3, CBSim, and GABA, respectively, and are represented with dashed lines. All the figures display the data with 95% confidence intervals over 20 runs, calculated using the standard error multiplied by the z-score 1.96.

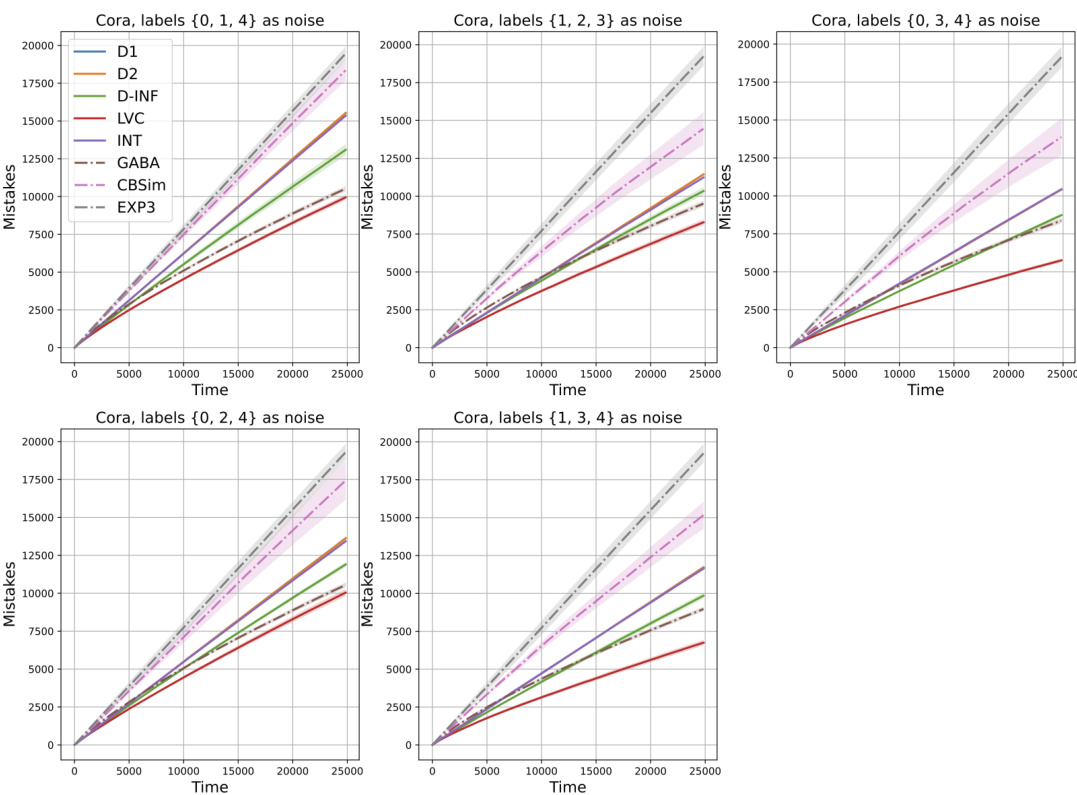

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different algorithms to the Cora dataset for node classification. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents the number of mistakes. Several different baselines are compared (dotted lines), and several variations of the CBA algorithm with different basis functions (solid lines) are shown. The different plots represent different selections of labels that were treated as ’noise’ in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 5: Cora results, dotted lines represent different baselines, while solid lines are used to represent various results

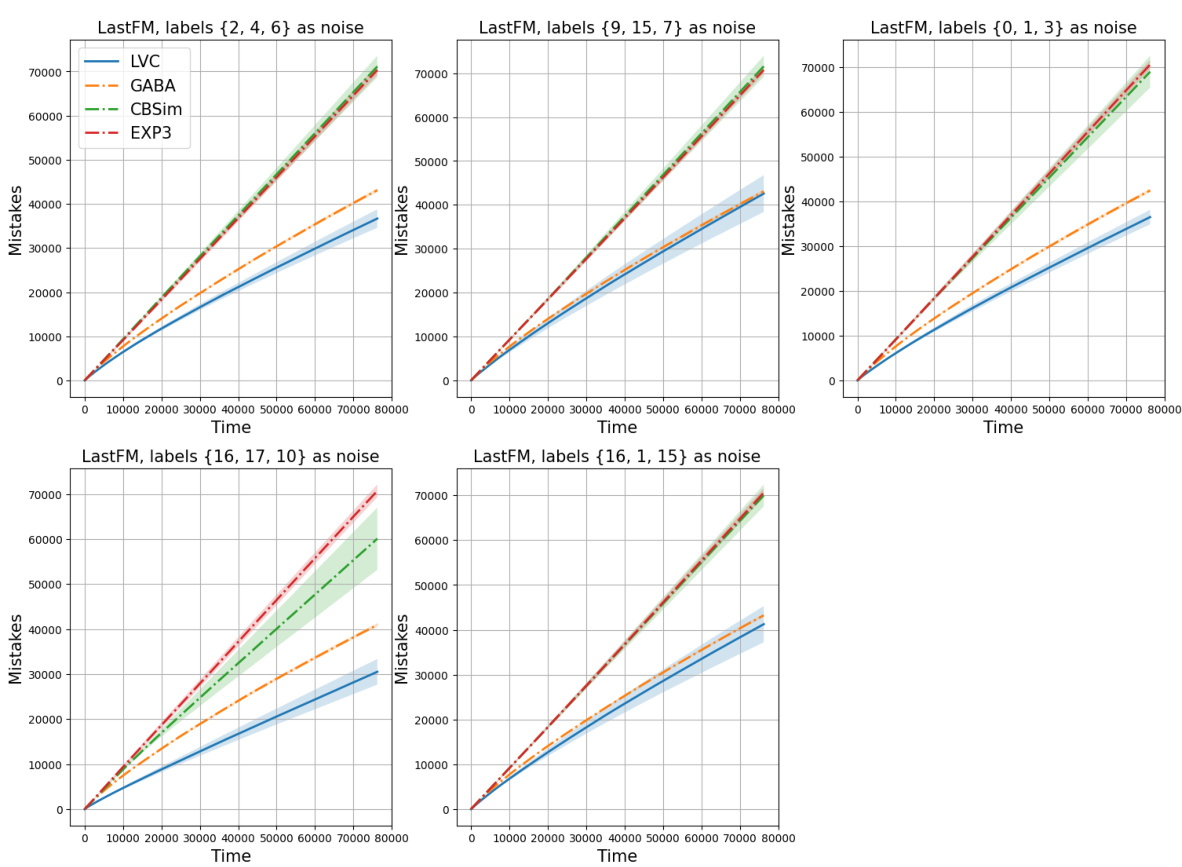

🔼 The figure shows the results of applying different algorithms (LVC, GABA, CBSim, EXP3) to the LastFM Asia dataset for different noise configurations. Each subplot represents a different set of labels chosen as noise, and the solid lines represent the performance of the CBA algorithm with different bases. The dotted lines show the performance of other baselines.

read the caption

Figure 6: LastFM Asia results, dotted lines represent different baselines, while solid lines are used to represent various results

Full paper#