↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning pre-trained models often leads to underperformance outside their specific domains. Model merging, integrating multiple models fine-tuned for different tasks, offers a solution but faces challenges in addressing parameter-level conflicts. Existing methods struggle to effectively balance parameter competition, limiting their efficiency and generalizability.

This paper introduces PCB-MERGING, a novel training-free method that resolves this issue by adjusting parameter coefficients. It employs intra-balancing to gauge parameter significance within individual tasks and inter-balancing to assess similarities across tasks. Less important parameters are dropped, and the remaining ones are rescaled. Experiments show substantial performance improvements across various modalities, domains, and model sizes, outperforming existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on model merging and multi-task learning. It offers a novel, training-free method that significantly improves performance compared to existing techniques. The findings are broadly applicable across various domains and models, opening up new avenues for efficient and privacy-preserving model fusion, and enhancing the generalizability of models. It also provides a clear framework for understanding and managing parameter competition, an area that has been largely overlooked in previous studies.

Visual Insights#

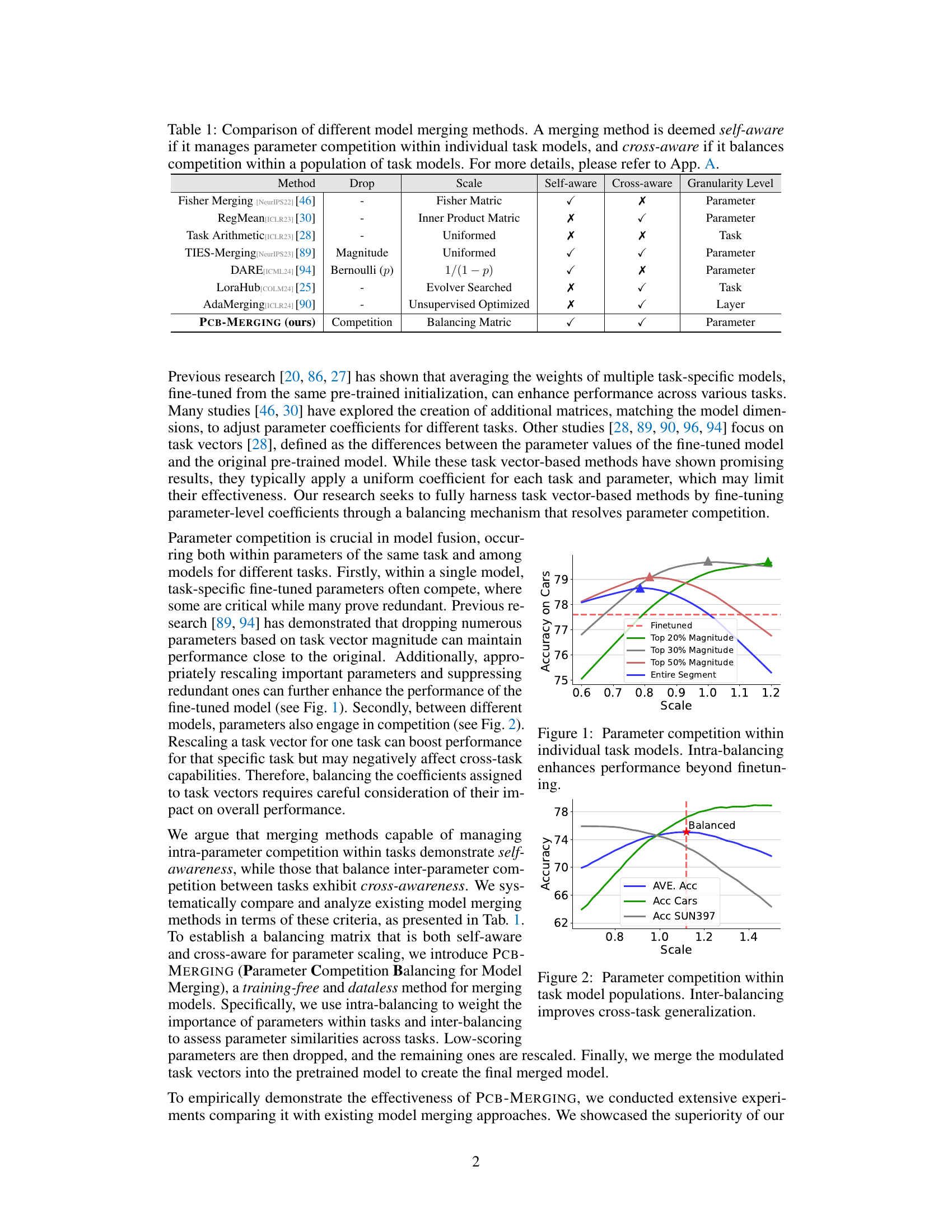

🔼 This figure shows how intra-balancing, a technique used in PCB-MERGING, improves the performance of individual task models by addressing parameter competition. The x-axis represents the scale factor applied to parameters, while the y-axis shows the accuracy on the ‘Cars’ task. Different lines represent different parameter selection strategies: using the top 20%, 30%, and 50% of parameters with the highest magnitude, and using all parameters (Entire Segment). The figure demonstrates that selectively keeping a subset of parameters (intra-balancing) often yields better results than using all parameters, implying that some parameters are more important than others in contributing to the final accuracy. The dashed red line shows the accuracy achieved by simply fine-tuning the model.

read the caption

Figure 1: Parameter competition within individual task models. Intra-balancing enhances performance beyond finetuning.

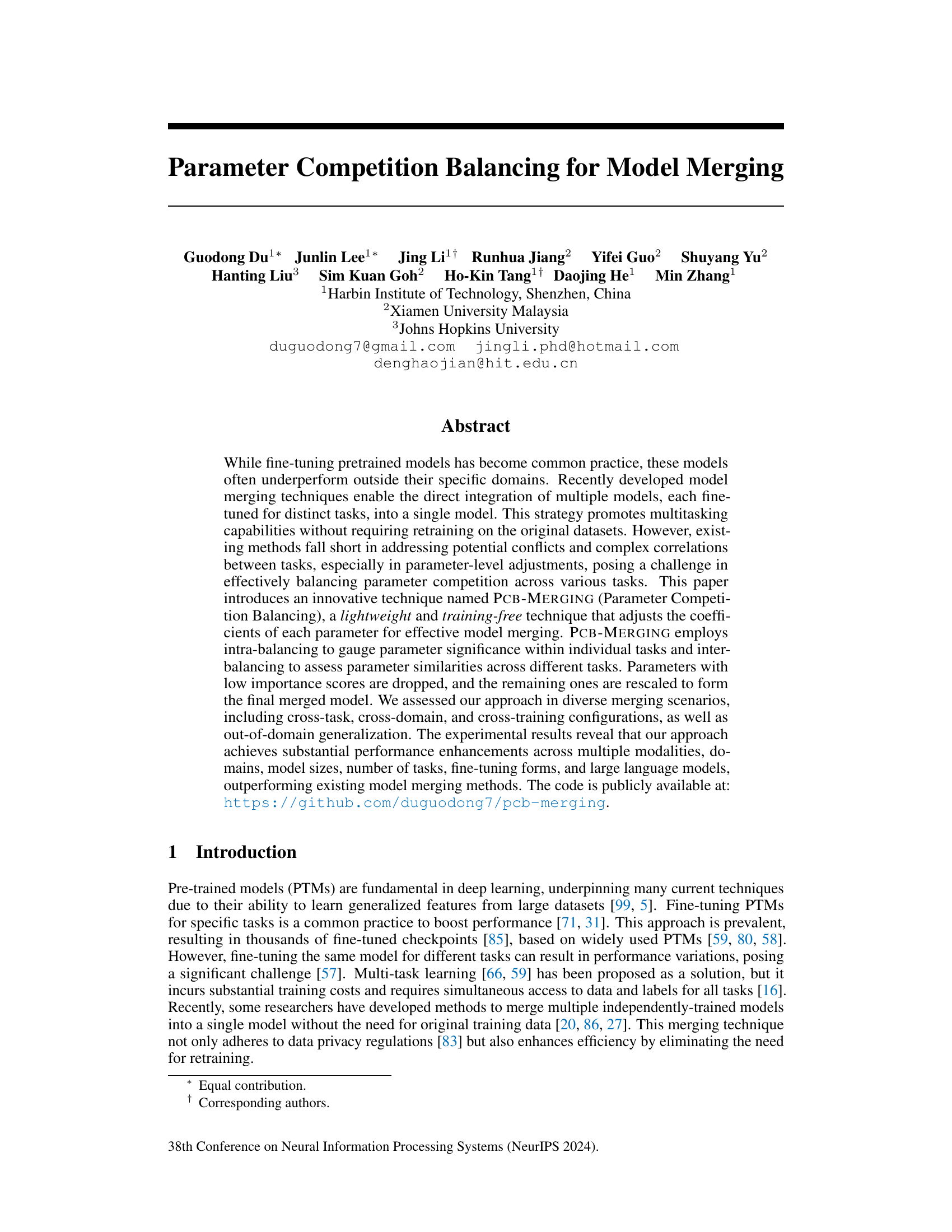

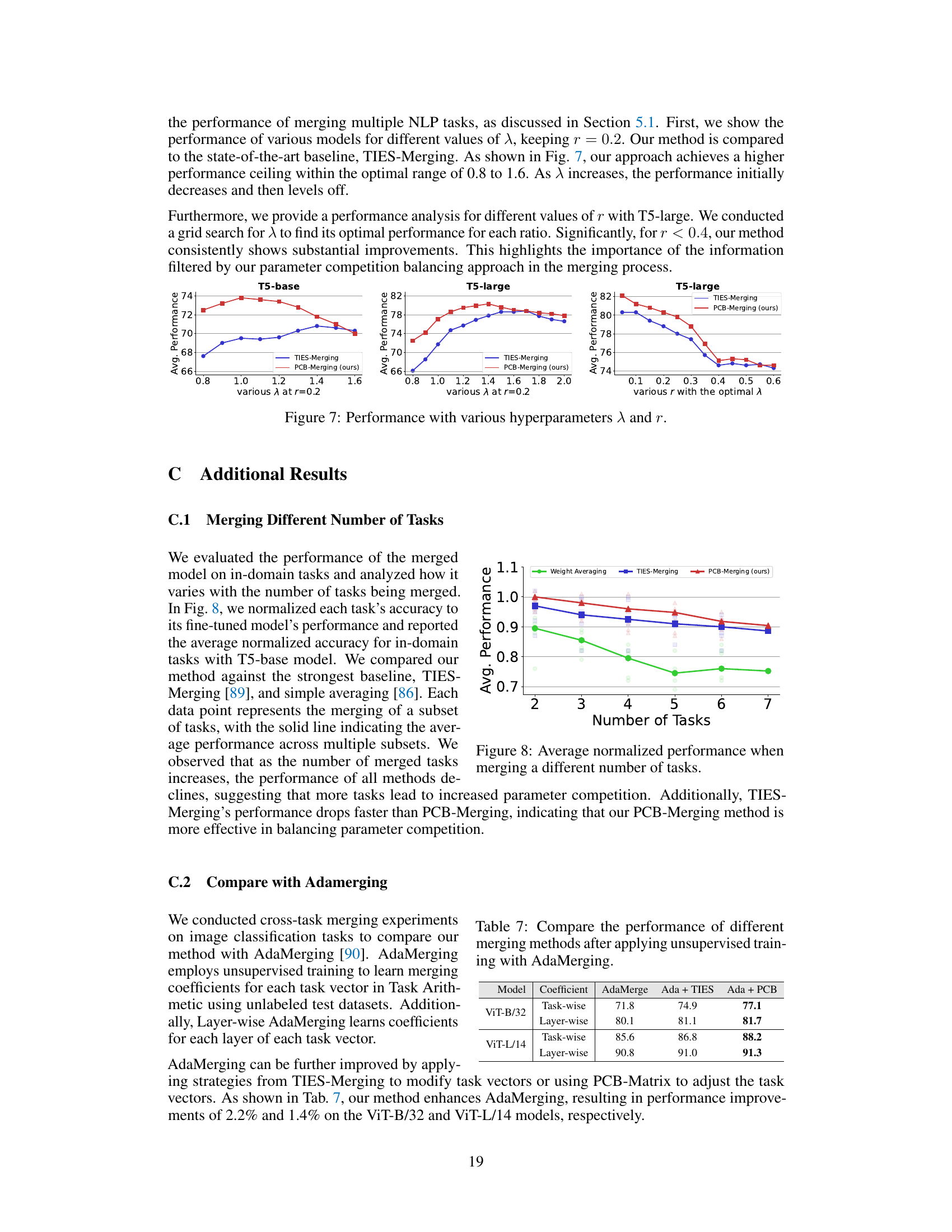

🔼 This table compares different model merging methods based on their ability to manage parameter competition within individual tasks (self-aware) and across multiple tasks (cross-aware). It also shows the granularity level at which the method operates (parameter, task, or layer). The table helps to understand the differences between various existing approaches and highlights the unique aspects of PCB-MERGING.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of different model merging methods. A merging method is deemed self-aware if it manages parameter competition within individual task models, and cross-aware if it balances competition within a population of task models. For more details, please refer to App. A.

In-depth insights#

Model Fusion Methods#

Model fusion methods aim to combine predictions from multiple models to improve overall performance. Simple averaging is the most straightforward approach, but it often underperforms more sophisticated methods. Weighted averaging techniques assign weights to individual models based on their performance or other criteria, potentially yielding significant improvements. More advanced methods leverage sophisticated mathematical frameworks like Fisher information matrices or task vectors to weight model parameters, resulting in more nuanced and often superior performance. Self-awareness and cross-awareness are crucial aspects of effective model fusion: self-awareness refers to the ability to manage within-model parameter competition across tasks, while cross-awareness involves balancing parameter competition across models. The choice of method is critical and depends on factors such as model architecture, task complexity, and available resources. Further research should focus on developing techniques that better address parameter competition, reduce computational cost, and improve generalization ability.

PCB-Merging: Details#

A hypothetical section titled “PCB-Merging: Details” in a research paper would delve into the intricate workings of the Parameter Competition Balancing (PCB) model merging technique. It would likely begin by elaborating on the intra-balancing process, explaining how the algorithm gauges the significance of each parameter within individual tasks. The explanation would probably involve mathematical formulations and a description of how these scores are calculated, potentially referencing specific normalization or activation functions. Then, the section would shift focus to the inter-balancing aspect. This part would detail how the algorithm compares parameter similarities across different tasks, using a suitable similarity metric. It would likely illustrate the interaction between intra and inter-balancing, highlighting how both scores are combined to create a final parameter weight matrix. Crucially, this section should clearly describe the drop and rescale step: the process of removing less important parameters and adjusting the coefficients of the remaining ones to address parameter competition. Finally, this section would demonstrate how this weighted parameter matrix is used to integrate individual models into a single, unified model. A detailed explanation of the mathematical steps involved and any choices in hyperparameters should be present. Visual aids such as diagrams or flowcharts would be essential for clarity and to help readers fully understand the computational steps.

Cross-Domain Results#

A hypothetical ‘Cross-Domain Results’ section would present a crucial evaluation of a model’s generalizability. It would likely show how well a model trained on one domain (e.g., medical images) performs when tested on a different, yet related domain (e.g., satellite imagery). Strong cross-domain performance would signal a robust model capable of transferring learned knowledge effectively, indicating it generalizes well beyond the specific training data. Conversely, weak cross-domain performance might indicate overfitting to the training data or limitations in the model’s ability to extract domain-invariant features. The section should include a detailed comparison of metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score etc.) across different domains, highlighting both successes and shortcomings. It would also be important to discuss potential reasons for any performance differences, such as differences in data characteristics or task complexities. A strong cross-domain analysis would enhance the paper’s credibility and showcase the model’s practical applicability in diverse real-world scenarios. The inclusion of error bars or other measures of statistical significance would add rigor and trustworthiness.

Parameter Balancing#

Parameter balancing, in the context of model merging, is a crucial technique for effectively integrating multiple pre-trained models. It addresses the inherent challenge of conflicting parameters when combining models fine-tuned for different tasks. Without careful balancing, merging can lead to performance degradation, as competing parameters interfere with each other, hindering the model’s ability to perform well across tasks. Successful parameter balancing methods prioritize important parameters while suppressing redundant or conflicting ones. This might involve techniques like weighting parameters based on their significance within individual tasks and across the overall model. Intra- and inter-balancing strategies are often employed. Intra-balancing focuses on harmonizing parameters within a single model, while inter-balancing aims to align parameters across different models, resolving conflicts and improving generalization. The effectiveness of a parameter balancing method is assessed through improvements in the merged model’s performance on multiple tasks and domains compared to individual models or simpler merging techniques. The ideal method should be lightweight and training-free, improving efficiency. Research in this area is actively exploring new approaches and techniques to achieve optimal parameter balancing and model merging.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this parameter competition balancing method for model merging could explore several key areas. Extending PCB-MERGING’s applicability to diverse model architectures beyond those with identical structures is crucial. This would involve investigating techniques to handle variations in layer depths, parameter dimensions, and overall network design. Addressing the theoretical underpinnings of the method is also vital. While empirically effective, a deeper understanding of parameter competition dynamics and how the balancing mechanism affects generalization is needed. Developing more sophisticated intra- and inter-balancing strategies is another promising direction, perhaps incorporating more nuanced measures of parameter significance and relationships between tasks. Investigating the optimal balance between dropping and rescaling parameters would fine-tune the approach further, possibly employing adaptive strategies based on task characteristics. Finally, research into the efficacy of the method with significantly larger models is essential to validate its scalability and potential for real-world applications. Addressing these research questions would solidify PCB-MERGING as a robust and versatile technique.

More visual insights#

More on figures

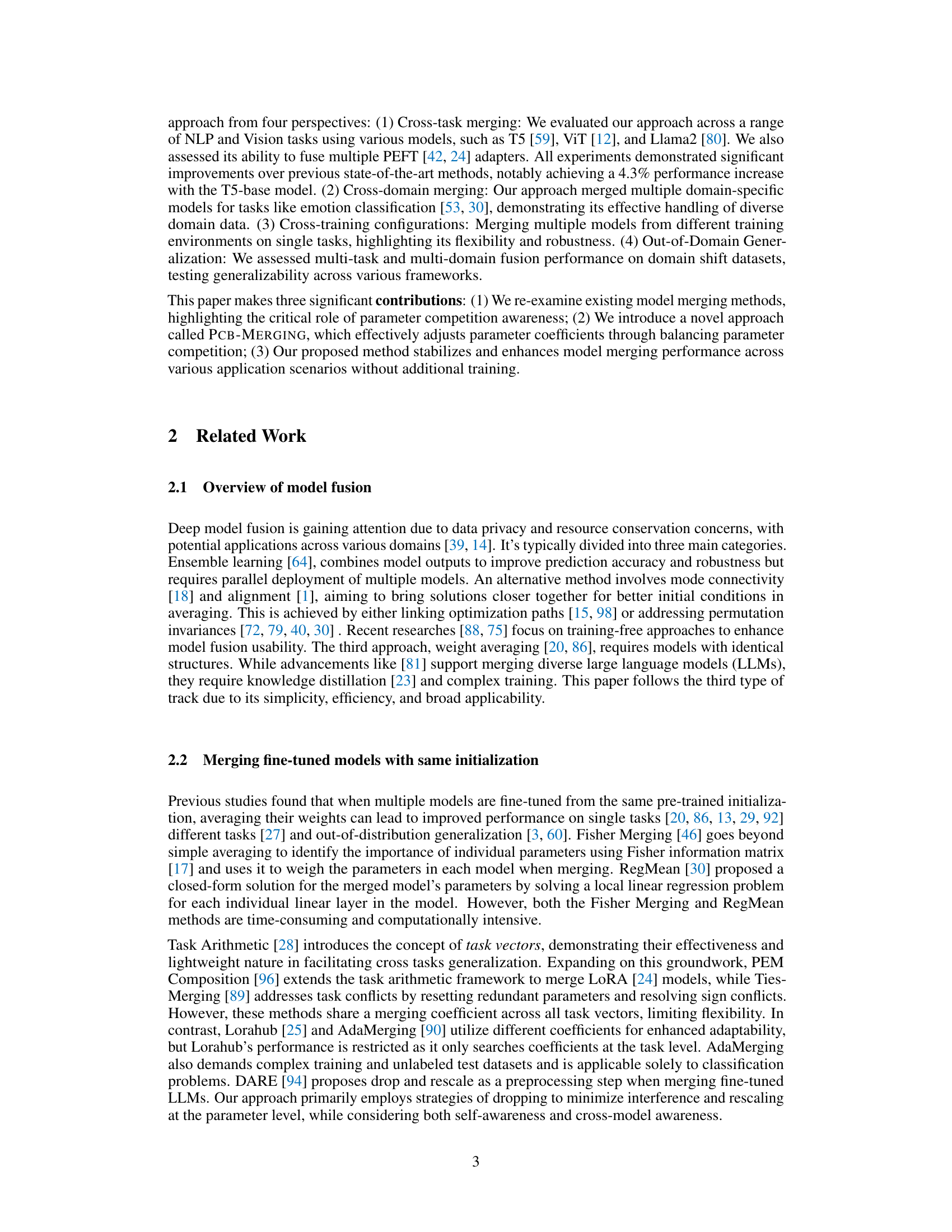

🔼 This figure shows the impact of inter-balancing on cross-task generalization performance. The x-axis represents the scaling factor applied to the task vectors during model merging. The y-axis shows the average accuracy across multiple tasks (AVE. Acc), the accuracy on the ‘Cars’ task (Acc Cars), and the accuracy on the ‘SUN397’ task (Acc SUN397). The red dashed line indicates the optimal scaling factor, where the inter-balancing technique achieves the best balanced performance across all three metrics. The results illustrate that carefully balancing parameter competition between tasks improves cross-task generalization and overall performance. The optimal scaling factor is determined by the point at which the lines representing the individual task accuracies intersect.

read the caption

Figure 2: Parameter competition within task model populations. Inter-balancing improves cross-task generalization.

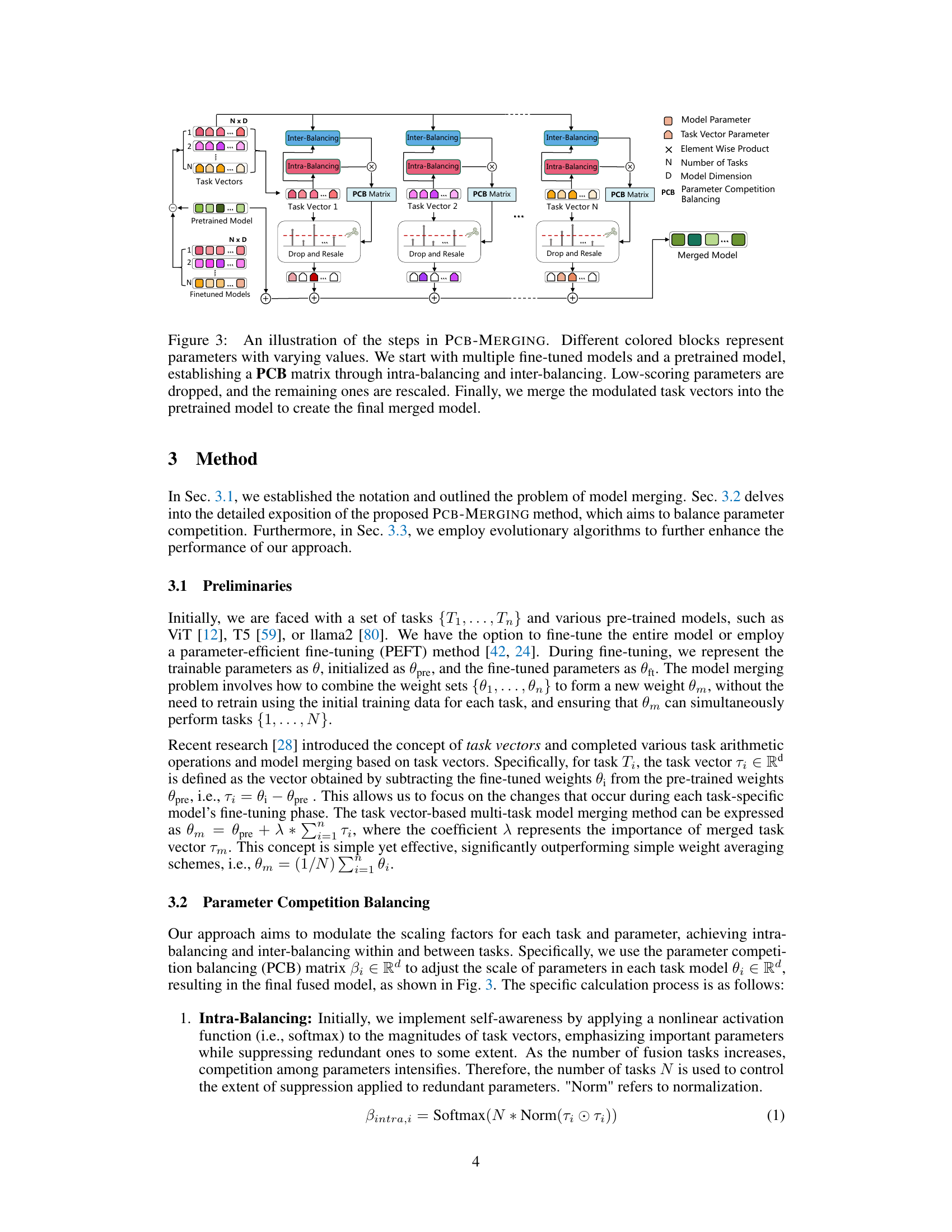

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of PCB-MERGING. It starts with multiple fine-tuned models and a pre-trained model. Intra-balancing and inter-balancing are used to create a PCB matrix, which weights the importance of parameters within and across tasks. Low-scoring parameters are dropped, and remaining ones are rescaled. Finally, modulated task vectors are merged into the pre-trained model to create the final merged model.

read the caption

Figure 3: An illustration of the steps in PCB-MERGING. Different colored blocks represent parameters with varying values. We start with multiple fine-tuned models and a pretrained model, establishing a PCB matrix through intra-balancing and inter-balancing. Low-scoring parameters are dropped, and the remaining ones are rescaled. Finally, we merge the modulated task vectors into the pretrained model to create the final merged model.

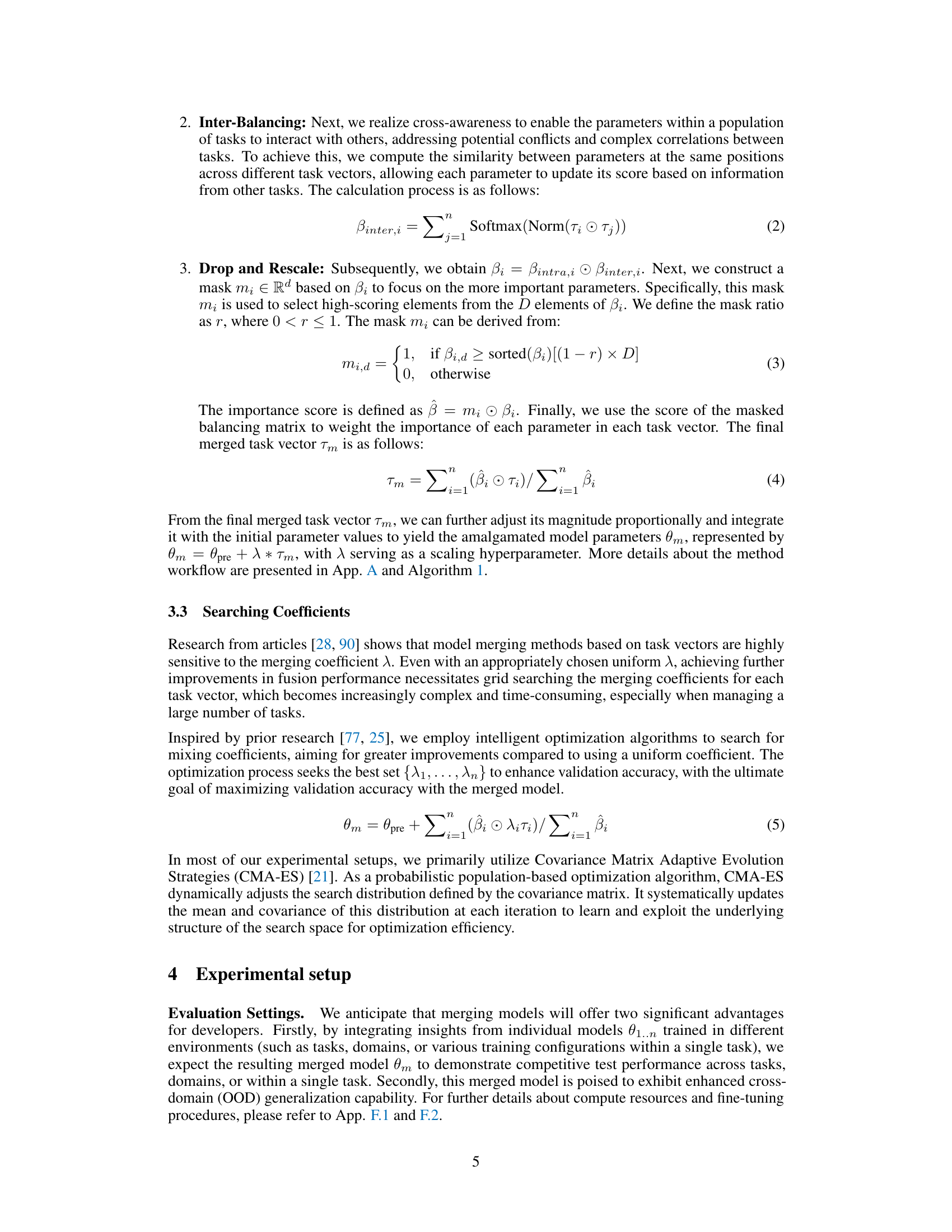

🔼 This figure compares the average out-of-domain (OOD) performance against the average in-domain performance for different model merging methods on 7 in-domain and 6 held-out datasets. It shows that PCB-Merging (the authors’ method) generally outperforms other methods, especially as in-domain performance increases, particularly for the T5-large model.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of average performance on 7 in-domain and 6 held-out datasets after cross-task merging.

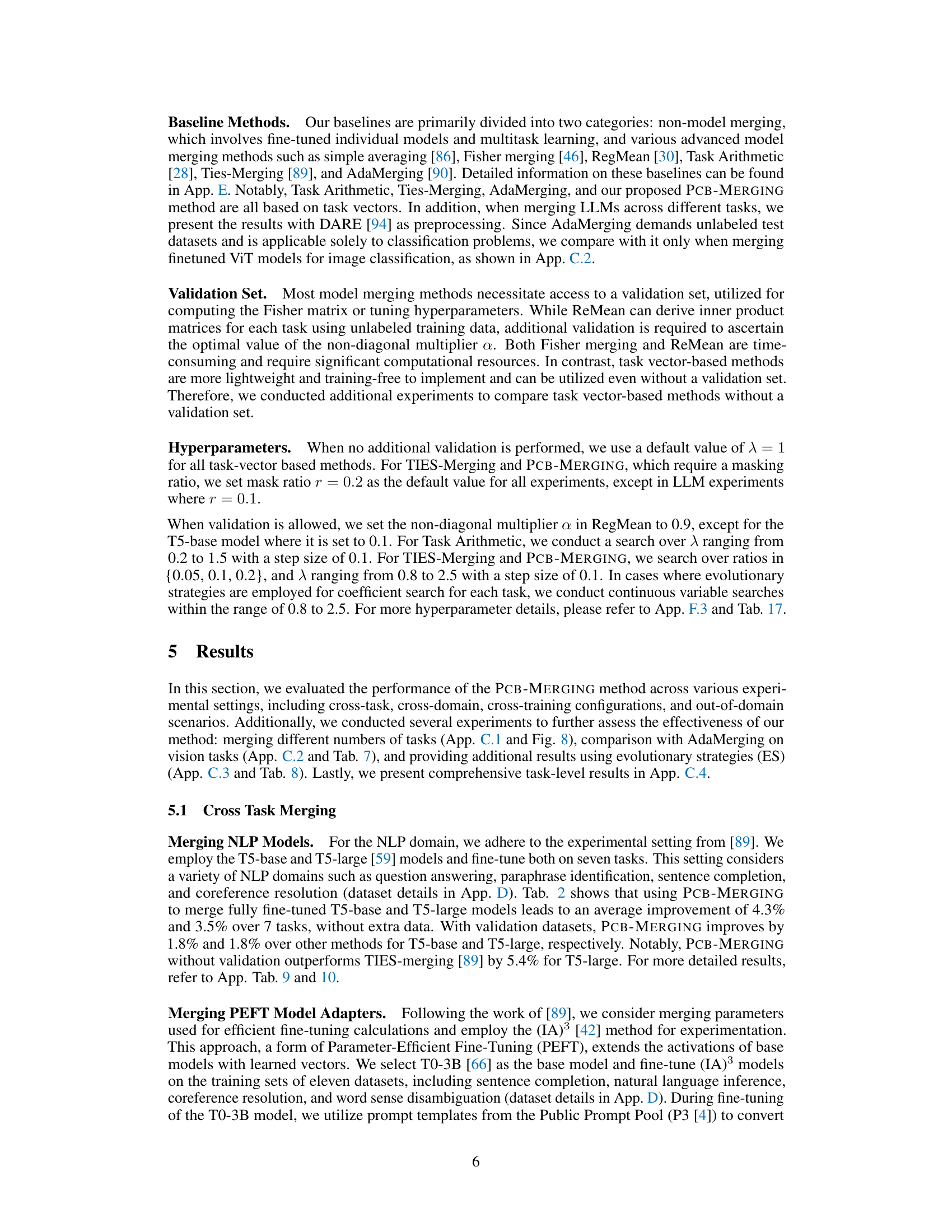

🔼 This figure compares the average out-of-domain (OOD) performance against the average in-domain performance of different model merging methods (Simple Averaging, Fisher Merging, RegMean, TIES-Merging, and PCB-Merging) using two base models, Roberta-base and T5-base, across five in-domain and five distribution shift datasets for emotion classification. The x-axis represents the average in-domain performance, and the y-axis represents the average OOD performance. The results show that PCB-Merging consistently outperforms other methods in both in-domain and OOD settings, demonstrating its effectiveness in cross-domain generalization.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparison of average performance on 5 in-domain and 5 distribution shift datasets after cross-domain merging.

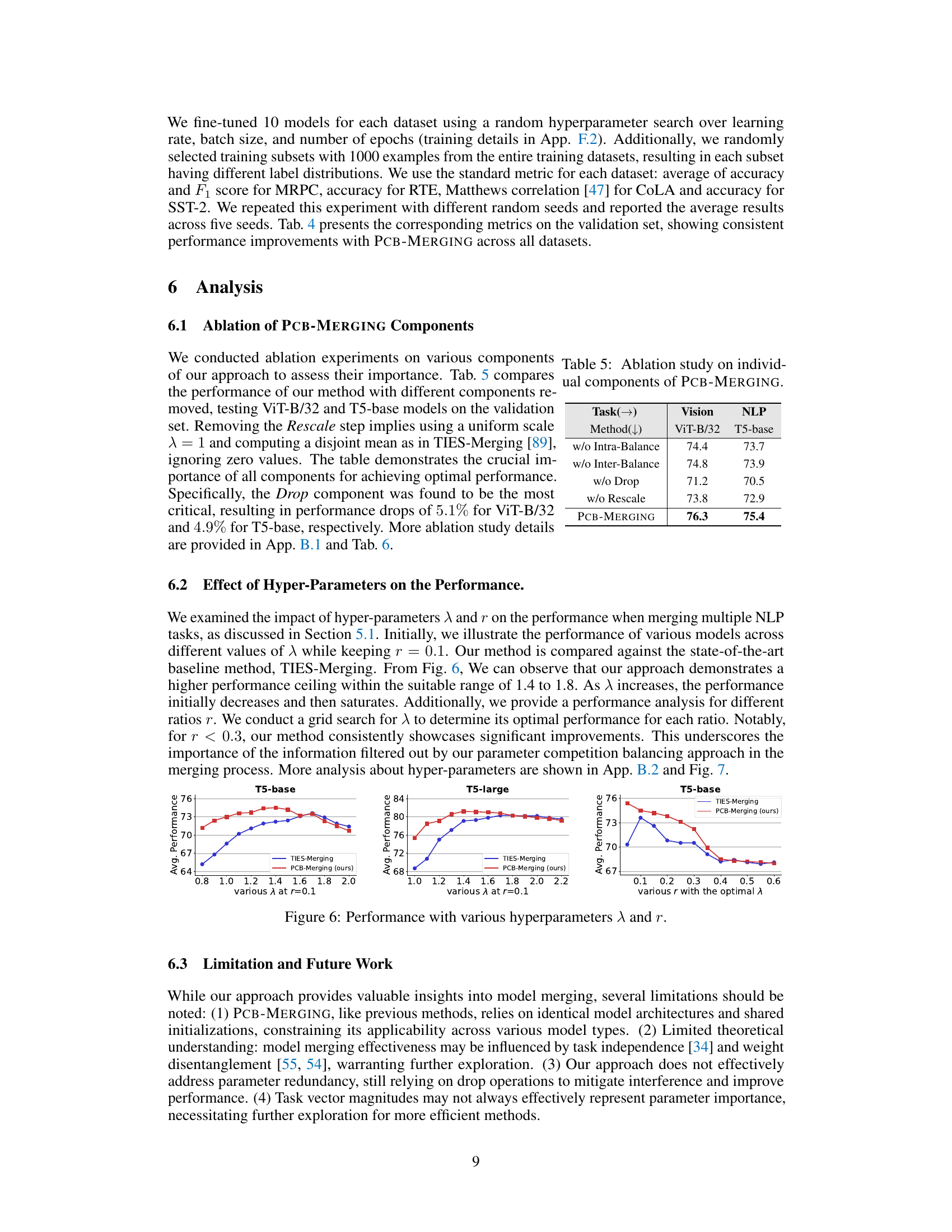

🔼 This figure shows the performance of different models across various values of lambda (λ) while keeping r constant at 0.1, and for various values of r with optimal lambda. It compares the performance of the proposed PCB-Merging method against the TIES-Merging baseline, showing that PCB-Merging achieves higher performance within a suitable range of parameters.

read the caption

Figure 6: Performance with various hyperparameters λ and r.

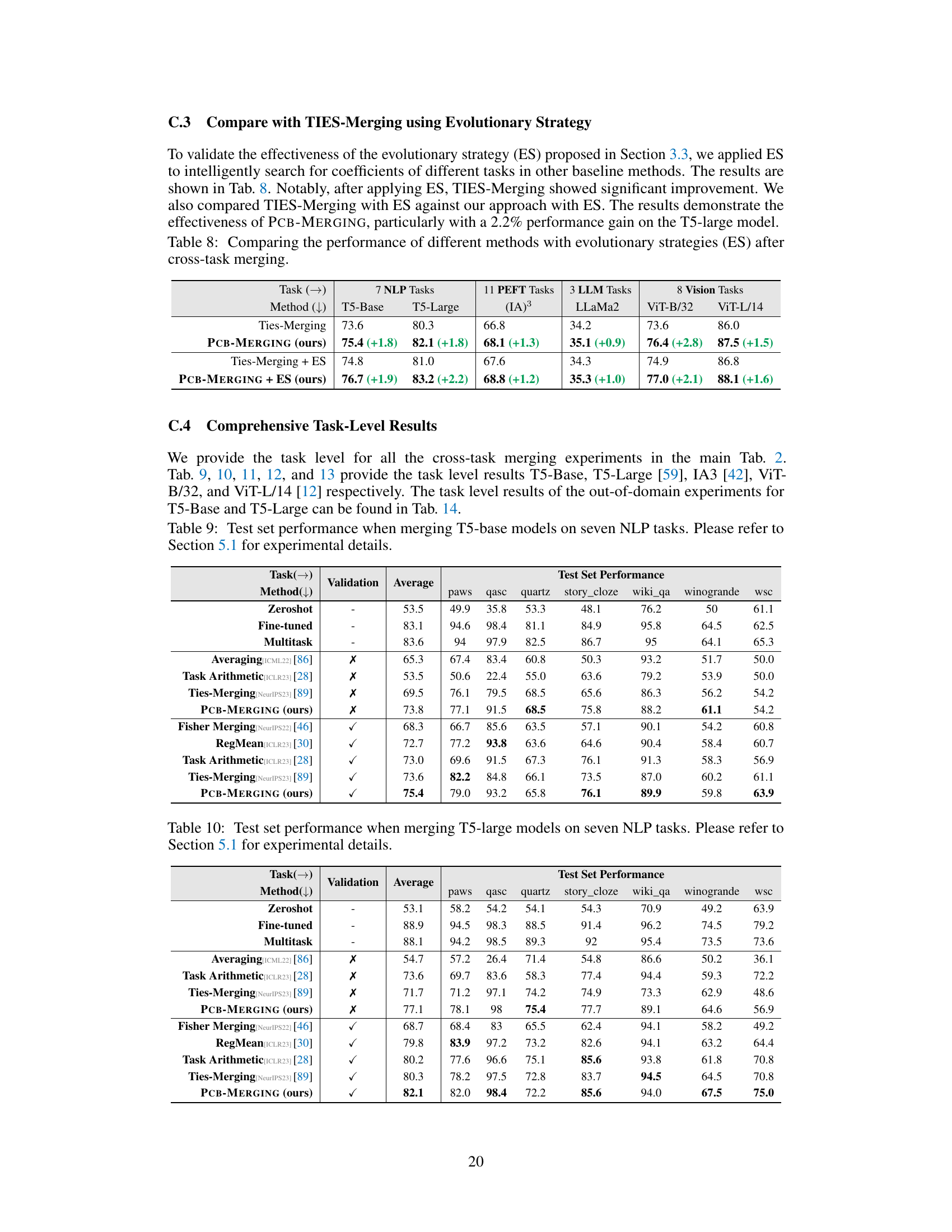

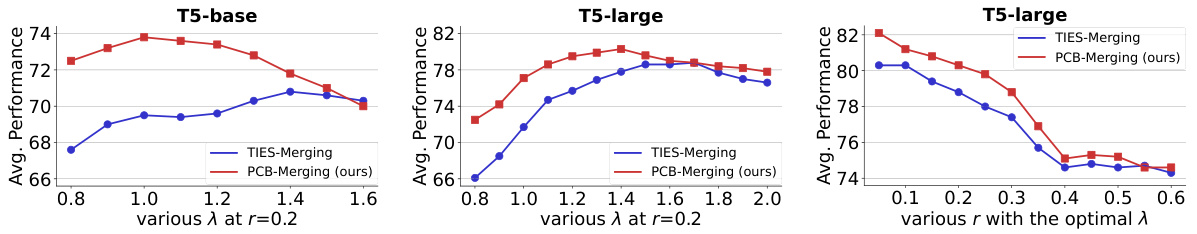

🔼 This figure shows the impact of hyperparameters λ (lambda) and r on the performance of merging multiple NLP tasks. The left and center plots show how performance varies with different values of λ for T5-base and T5-large models, respectively, while keeping r constant at 0.2. The right plot displays how performance changes with different values of r for the T5-large model, with the optimal λ determined for each r value. The results indicate that performance is highly sensitive to these hyperparameters and there exists an optimal range where the performance is maximized.

read the caption

Figure 6: Performance with various hyperparameters λ and r.

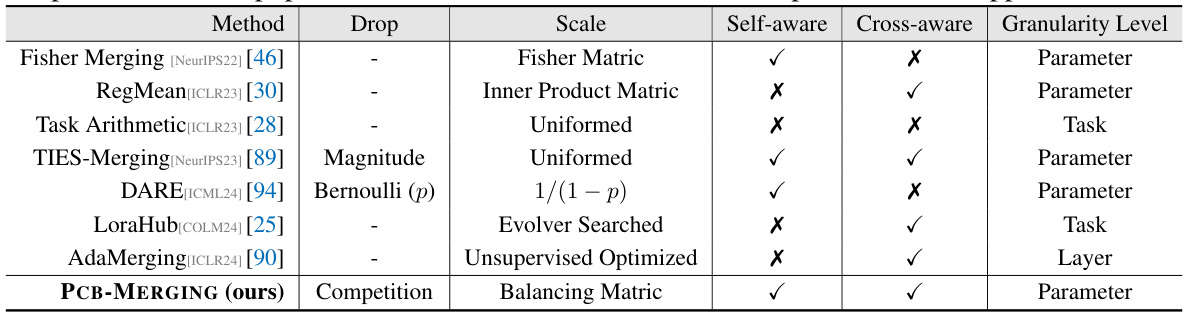

🔼 This figure shows the average normalized performance of different model merging methods (Weight Averaging, TIES-Merging, and PCB-Merging) across varying numbers of tasks (from 2 to 7). The performance is normalized to the individual fine-tuned model’s performance for each task. The results indicate that as the number of merged tasks increases, performance decreases for all methods. This is likely due to increased parameter competition among tasks. Importantly, PCB-Merging shows a slower performance decline compared to the other methods, highlighting its effectiveness in managing parameter competition during model merging.

read the caption

Figure 8: Average normalized performance when merging a different number of tasks.

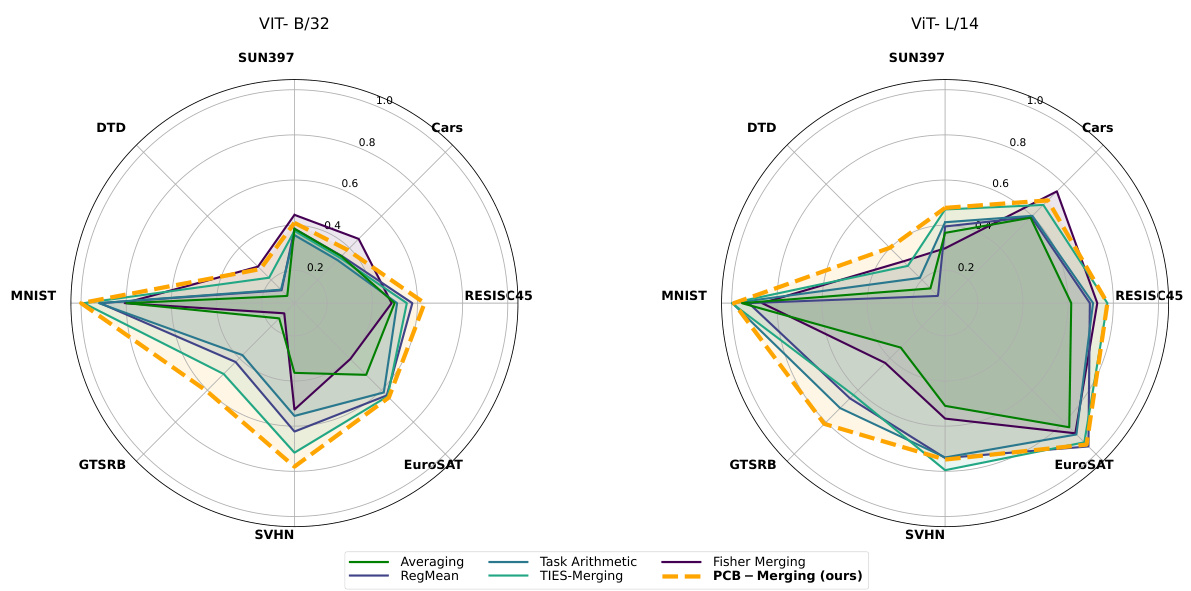

🔼 This figure shows radar charts visualizing the performance of different model merging methods on eight image classification tasks using two versions of the CLIP model (ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14) as visual encoders. Each axis represents a specific task (SUN397, Cars, RESISC45, EuroSAT, SVHN, GTSRB, MNIST, and DTD), and the radial distance from the center indicates the performance of each merging method on that task. The figure helps compare the performance of the different merging methods (Averaging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, TIES-Merging, Fisher Merging, and PCB-Merging) across multiple image classification tasks.

read the caption

Figure 9: Test set performance when merging ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14 models on eight image classification tasks.

More on tables

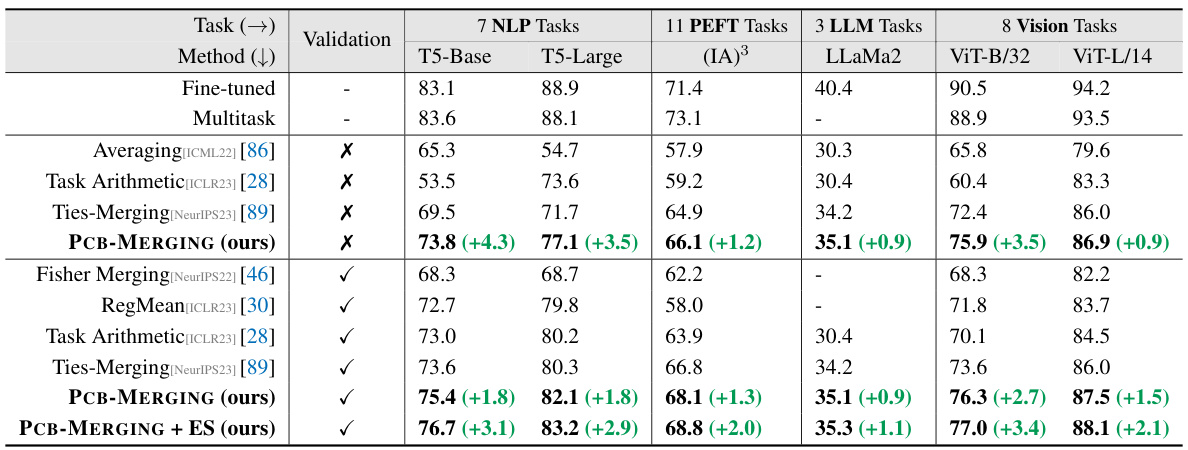

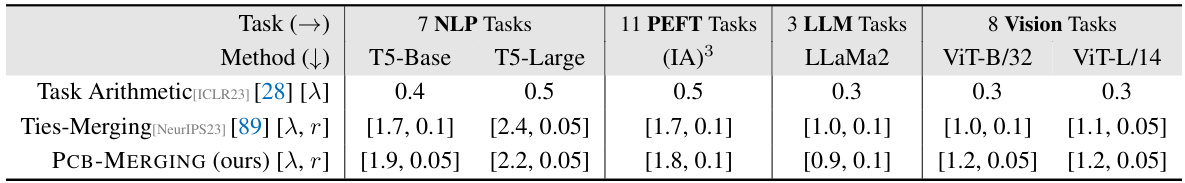

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP, PEFT, LLMs, and Vision). It shows the average performance improvement achieved by PCB-MERGING compared to several baseline methods, including simple averaging, Fisher merging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, and Ties-Merging. The table highlights PCB-MERGING’s consistent performance gains across various tasks and model types, demonstrating its effectiveness in different settings.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

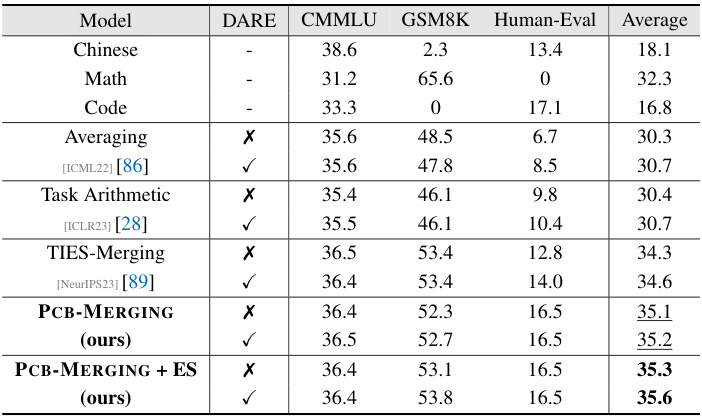

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods on three different tasks (Chinese language proficiency, mathematical reasoning, and code generation) after merging three large language models. The methods compared include averaging, Task Arithmetic, TIES-Merging, and PCB-MERGING (with and without DARE preprocessing). The table shows the average performance across the three tasks, highlighting PCB-MERGING’s improved performance, especially with the inclusion of DARE preprocessing.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of the performance of different methods on 3 datasets after merging LLMs.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP, PEFT, LLMs, and Vision). It shows the average performance of fine-tuned models, multi-task learning models and several advanced merging techniques including averaging, Fisher Merging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, TIES-Merging, and PCB-MERGING. The results are presented for different model sizes (T5-base, T5-large, ViT-B/32, ViT-L/14) and configurations, and highlight the superior performance of the proposed PCB-MERGING method across various settings, both with and without a validation set.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

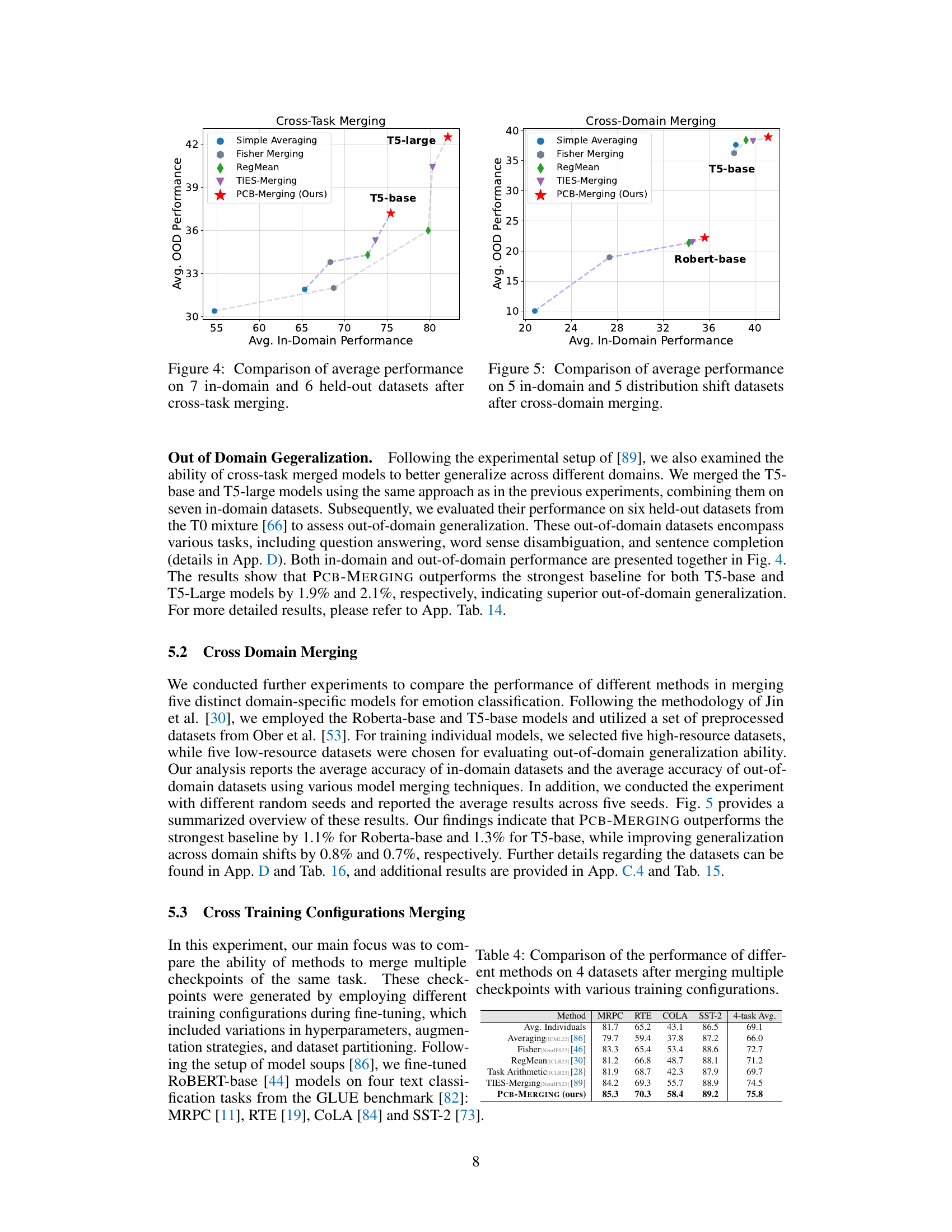

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation experiments conducted to evaluate the impact of individual components of the PCB-MERGING method. It shows the performance of the method when different components are removed, such as intra-balancing, inter-balancing, the drop mechanism, and rescaling. The results highlight the importance of each component for achieving optimal performance. The ablation experiments were performed on two model architectures: ViT-B/32 and T5-base.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study on individual components of PCB-MERGING.

🔼 This table compares the average performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP, PEFT, LLM, and Vision). It shows the performance gains achieved by PCB-MERGING over baseline methods such as simple averaging, Fisher Merging, and others, for both fine-tuned models and when using a validation set. The results demonstrate improved performance from PCB-MERGING across multiple modalities, task types, and training configurations.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

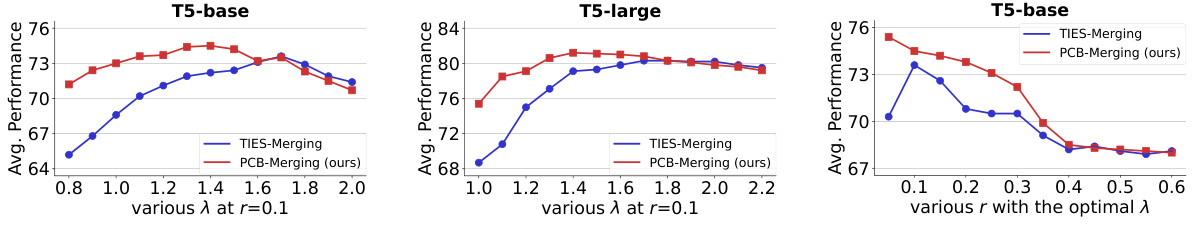

🔼 This table compares the performance of different model merging methods, specifically AdaMerging, AdaMerging combined with TIES-Merging, and AdaMerging combined with PCB-Merging. The comparison is done for both task-wise and layer-wise coefficient application on ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14 models. It highlights how PCB-Merging improves upon AdaMerging by further enhancing performance.

read the caption

Table 7: Compare the performance of different merging methods after applying unsupervised training with AdaMerging.

🔼 This table compares the performance of several model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP, PEFT, LLMs, and Vision). It shows the average performance of each method for multiple tasks using several different models (T5-Base, T5-Large, (IA)³, LLaMa2, ViT-B/32, and ViT-L/14). The numbers in parentheses indicate performance improvements compared to the ‘Fine-tuned’ baseline. The table highlights the superior performance of the PCB-MERGING method across various tasks and model types.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities. It shows the average performance for each method on seven NLP tasks using T5-base and T5-large models, eleven PEFT tasks using (IA)³ models, three LLM tasks using Llama2 models, and eight vision tasks using ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14 models. The results are presented with and without access to a validation set, demonstrating the impact of validation data on the methods’ performance. The table also highlights the improvements achieved by PCB-MERGING compared to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities, considering various fine-tuning configurations. The average performance is shown for different sets of tasks (NLP, PEFT, LLMs, and Vision). It provides a comparison to baselines such as fine-tuned models, multi-task learning, simple averaging, Fisher merging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, and Ties-Merging. The table highlights the improved performance of PCB-MERGING, particularly when a validation set is not available. Parenthetical values show percentage improvements over baseline methods for T5-base and T5-large models.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP and Vision). It shows the average performance for each method on several tasks, comparing fine-tuned, multitask, and different model merging methods. The results highlight the performance gains achieved by PCB-MERGING compared to baselines, particularly in cross-task, cross-domain, and out-of-domain scenarios. The table also indicates if a validation set was used and provides the average improvement obtained by PCB-MERGING compared to the top performing baseline.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the average performance of different model merging methods across various tasks and modalities. It shows the performance improvements achieved by PCB-MERGING (the authors’ method) compared to various baselines, such as simple averaging, Fisher merging, and Task Arithmetic. The results are broken down by modality (NLP, PEFT, LLM, Vision) and whether a validation set was used. The table highlights the superior performance of PCB-MERGING across multiple tasks, models, modalities, and training settings.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP and Vision). It shows the average performance of each method for several tasks after fine-tuning using different configurations. The table includes baseline methods (simple averaging, Fisher merging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, Ties-Merging) and the proposed PCB-MERGING method, allowing for a comparison of performance improvements.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and model types (NLP, PEFT, LLM, Vision). It shows the average performance of each method for each set of tasks, comparing against fine-tuned and multitask baselines. The table highlights the improvements achieved by PCB-MERGING, particularly on the T5-base and T5-large models.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities (NLP and Vision). It shows the average performance for several baseline methods (simple averaging, Fisher merging, RegMean, Task Arithmetic, Ties-Merging) and the proposed PCB-MERGING method. The table includes results with and without using a validation set. The results demonstrate that PCB-MERGING consistently outperforms existing methods in multiple scenarios.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various model merging methods across different tasks and modalities. It shows the average performance (accuracy or F1 score, depending on the task) for each method across seven NLP tasks (using T5-base and T5-large models), eleven PEFT tasks (using (IA)3 adapters and T0-3B models), three LLM tasks (using Llama2 models), and eight vision tasks (using ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14 models). Results are shown both with and without a validation set, highlighting the impact of validation data on model performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of PCB-MERGING with other model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities. It shows the average performance across multiple tasks for several different models (T5-Base, T5-Large, IA³ and Llama2 for NLP, and ViT-B/32 and ViT-L/14 for vision). The results demonstrate the improvement achieved by PCB-MERGING compared to baselines, highlighting its effectiveness across different scenarios and model types.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different model merging methods across various fine-tuning configurations and modalities, with average performance reported for different tasks.

Full paper#