TL;DR#

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) aims to learn rewards from expert demonstrations, but ensuring the learned reward generalizes to new situations (transferability) is challenging. Previous work made strong assumptions, like having full access to expert policies. This often doesn’t hold in practice. A key issue is that a reward that perfectly explains one expert’s behavior isn’t unique; many rewards can work.

This paper tackles the transferability challenge head-on. Instead of relying on restrictive binary conditions, it proposes using principal angles—a more nuanced measure of similarity between different environments—to determine transferability. The authors establish sufficient conditions for learning transferable rewards even with limited access to expert demonstrations. They introduce a new probably approximately correct (PAC) algorithm with end-to-end guarantees. This significantly advances IRL’s practical applicability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning and related fields because it addresses a critical challenge of transferability in inverse reinforcement learning (IRL). The novel approach using principal angles offers a more practical and robust way to learn transferable rewards, moving beyond previous limitations of full policy access. This work opens new avenues for developing more reliable and efficient IRL algorithms, impacting various applications such as robotics and autonomous driving where reward transferability is essential.

Visual Insights#

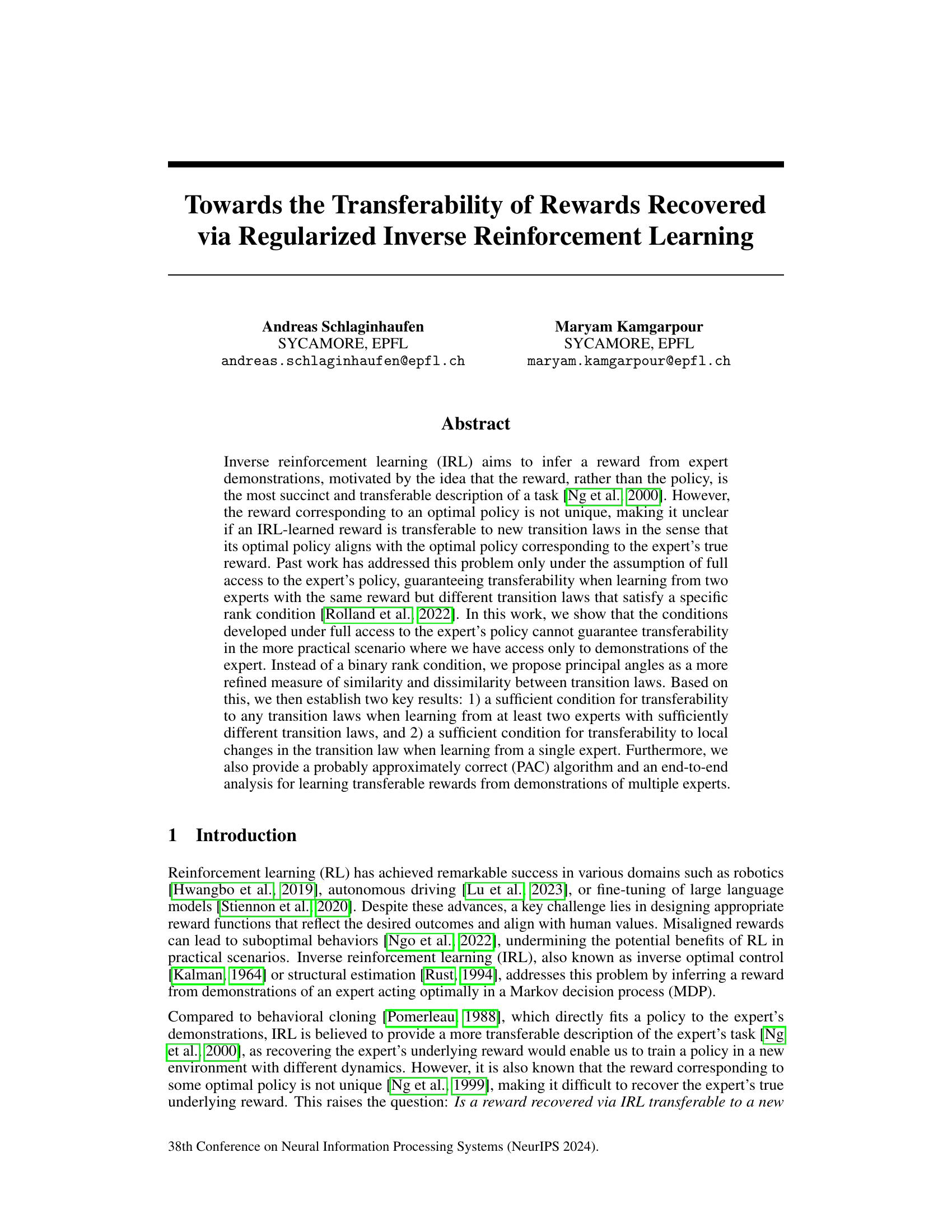

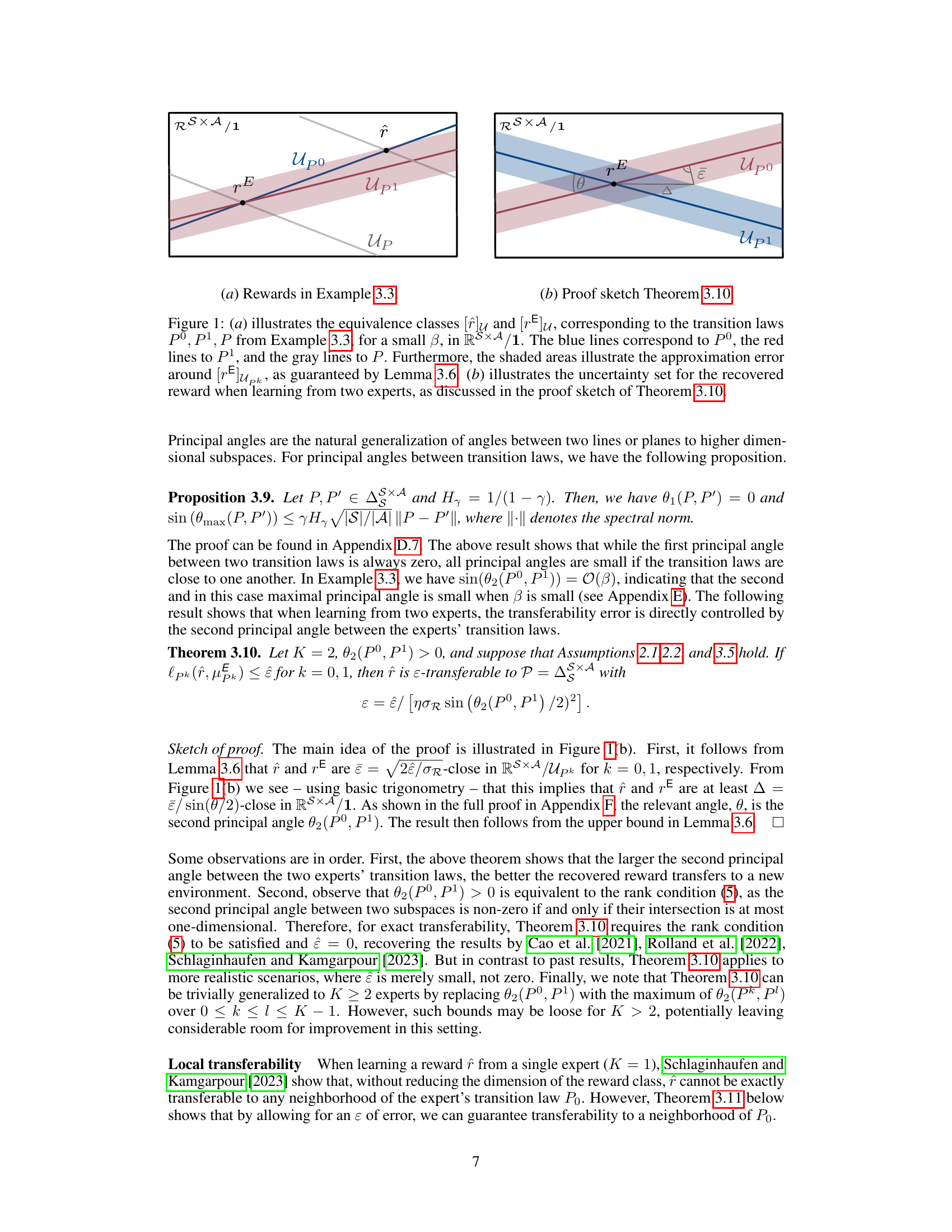

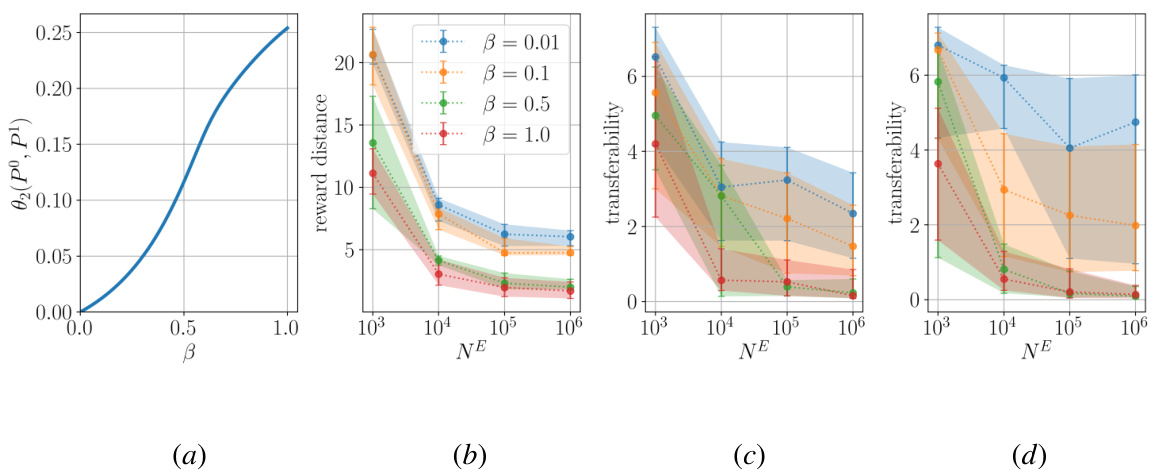

🔼 Figure 1(a) shows the reward equivalence classes for Example 3.3 in the quotient space RS×A/1, illustrating how the closeness of the recovered reward to the expert reward depends on the principal angles between the transition laws. Figure 1(b) illustrates Theorem 3.10’s proof sketch by showing the uncertainty set for the reward recovered from two experts.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) illustrates the equivalence classes [r]U and [rE]U, corresponding to the transition laws P0, P1, P from Example 3.3, for a small β, in RS×A/1. The blue lines correspond to P0, the red lines to P1, and the gray lines to P. Furthermore, the shaded areas illustrate the approximation error around [rE]Upk, as guaranteed by Lemma 3.6. (b) illustrates the uncertainty set for the recovered reward when learning from two experts, as discussed in the proof sketch of Theorem 3.10.

🔼 This table provides a list of notations used throughout the paper. It includes mathematical symbols, set definitions, and function notations related to reinforcement learning, inverse reinforcement learning, and the mathematical framework used in the study.

read the caption

Table 1: Notations.

In-depth insights#

Transferability Limits#

The concept of ‘Transferability Limits’ in the context of reinforcement learning (RL) is crucial. It explores the boundaries of an RL agent’s ability to apply knowledge gained in one environment to another. Reward function design is key; a reward function optimized for a specific setting might not generalize well, leading to suboptimal performance in a new scenario. This limitation highlights the need for reward functions that capture task essence rather than specific environmental details. Domain adaptation techniques become vital to address this challenge, bridging the gap between source and target environments. The research area actively investigates methods to enhance transferability, perhaps through feature engineering or meta-learning approaches, but fundamental limits imposed by the nature of the environments themselves remain a core research question.

PAC Algorithm for IRL#

A Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) algorithm for Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) is a significant advancement because it addresses the challenge of inferring a reward function from limited expert demonstrations. Standard IRL methods often lack guarantees on the quality of the learned reward. A PAC algorithm, however, provides a probabilistic guarantee that, given enough data, the learned reward will be close to the true reward within a specified tolerance. This is crucial because in real-world applications, it is often impossible to obtain an infinite number of perfect demonstrations. A PAC algorithm for IRL would require careful consideration of sample complexity (how much data is needed for a certain level of accuracy) and computational efficiency. The algorithm’s success hinges on assumptions about the underlying Markov Decision Process (MDP) and the reward function class. Furthermore, the design of such an algorithm would need to handle the non-uniqueness of optimal rewards, potentially incorporating regularization techniques or other constraints. The resulting PAC bounds would quantify the trade-off between the desired accuracy, the allowed error probability, and the amount of training data required. Ultimately, a PAC approach provides a strong theoretical foundation and ensures robust performance in uncertain conditions.

Principal Angle Metric#

The concept of a ‘Principal Angle Metric’ in the context of comparing transition laws within inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) offers a compelling approach to assess similarity and dissimilarity. Instead of relying on binary rank conditions, which may be too simplistic, principal angles provide a more nuanced measure of the relationship between different transition dynamics. This is crucial because the transferability of learned rewards depends significantly on how similar the new environment’s transition law is to those observed during training. By quantifying this similarity using principal angles, we gain a more refined understanding of reward generalizability. This approach moves beyond simple binary classifications (similar/dissimilar), allowing for a more granular assessment of transferability based on the degree of similarity. The choice of a principal angle metric is theoretically sound, offering a principled way to compare subspaces which represent the impact of different transition laws on the occupancy measure space. This enhances the practical applicability of IRL, making it more robust and reliable in real-world scenarios where transition laws are rarely identical.

Multi-Expert Analysis#

Multi-expert analysis in machine learning leverages the combined knowledge of multiple experts to improve model accuracy and robustness. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with complex tasks or ambiguous data, where a single expert’s perspective might be insufficient. In the context of reinforcement learning, for example, multiple expert demonstrations can help to overcome the challenge of reward function ambiguity, a critical problem in inverse reinforcement learning (IRL). By learning from the diverse experiences and strategies of multiple experts, the model can identify more robust and generalizable patterns, leading to better performance in unseen situations. This approach also enhances the transferability of learned knowledge. A reward function learned from diverse experts may generalize better across different environments, improving the deployment flexibility of the model. However, challenges exist in integrating multi-expert data, especially when dealing with conflicting or inconsistent information. The development of effective algorithms that can reconcile these discrepancies and learn from inconsistent data sources is a significant research area. Furthermore, the computational cost of multi-expert analysis can be substantial, particularly when working with large datasets or complex models, necessitating the design of efficient algorithms.

Gridworld Experiments#

In the hypothetical ‘Gridworld Experiments’ section, the authors likely detail the experimental setup, including a description of the gridworld environment (size, wind patterns, action space, etc.). They would then describe the methodology for generating expert demonstrations within this environment. This likely involved training agents using reinforcement learning with a known reward function, simulating expert behavior. The core of the experiments would focus on evaluating the transferability of rewards learned using inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) under various scenarios. Key metrics may include suboptimality of the IRL-recovered reward and performance of a new policy trained with this reward in a novel transition dynamics environment. The authors might vary parameters such as the wind strength or direction, or even the action space itself, to assess the robustness of the learned reward across diverse conditions. The results would likely show how the accuracy of reward transfer depends on factors such as the similarity of the transition laws, principal angles between transition dynamics, and the amount of expert data used in training. Successful results would provide strong empirical support for the theoretical findings, demonstrating the practical applicability and limitations of the proposed IRL method. The inclusion of error bars and statistical significance measures would further enhance the credibility of the experimental findings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 Figure 1(a) shows the equivalence classes of rewards corresponding to the transition laws P0, P1, and P from Example 3.3 in the quotient space RS×A/1. The shaded areas show the approximation error around the true reward [rE]Upk, as proved in Lemma 3.6. Figure 1(b) shows the uncertainty set of recovered rewards when using two experts, as shown in the proof of Theorem 3.10.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) illustrates the equivalence classes [r]U and [rE]U, corresponding to the transition laws P0, P1, P from Example 3.3, for a small β, in RS×A/1. The blue lines correspond to P0, the red lines to P1, and the gray lines to P. Furthermore, the shaded areas illustrate the approximation error around [rE]Upk, as guaranteed by Lemma 3.6. (b) illustrates the uncertainty set for the recovered reward when learning from two experts, as discussed in the proof sketch of Theorem 3.10.

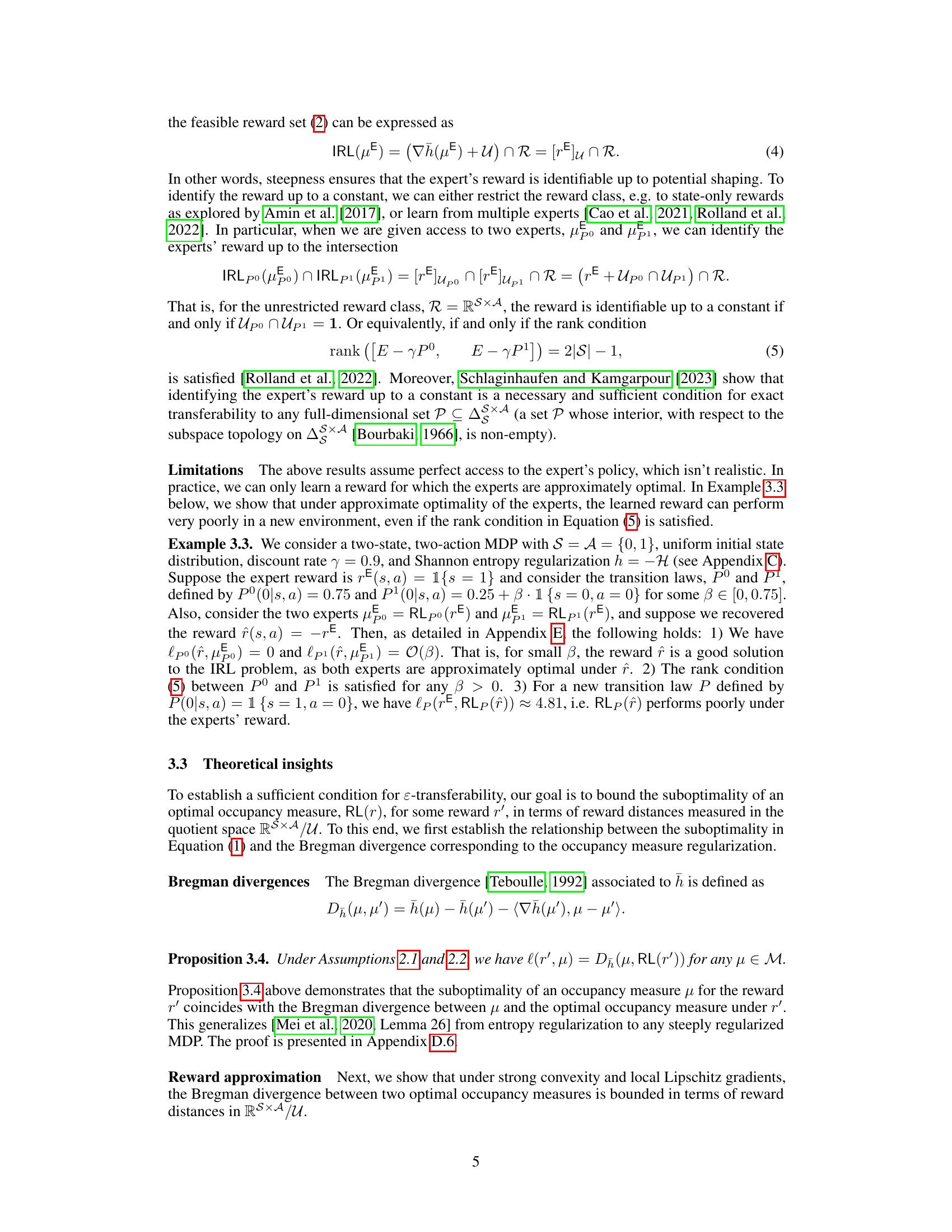

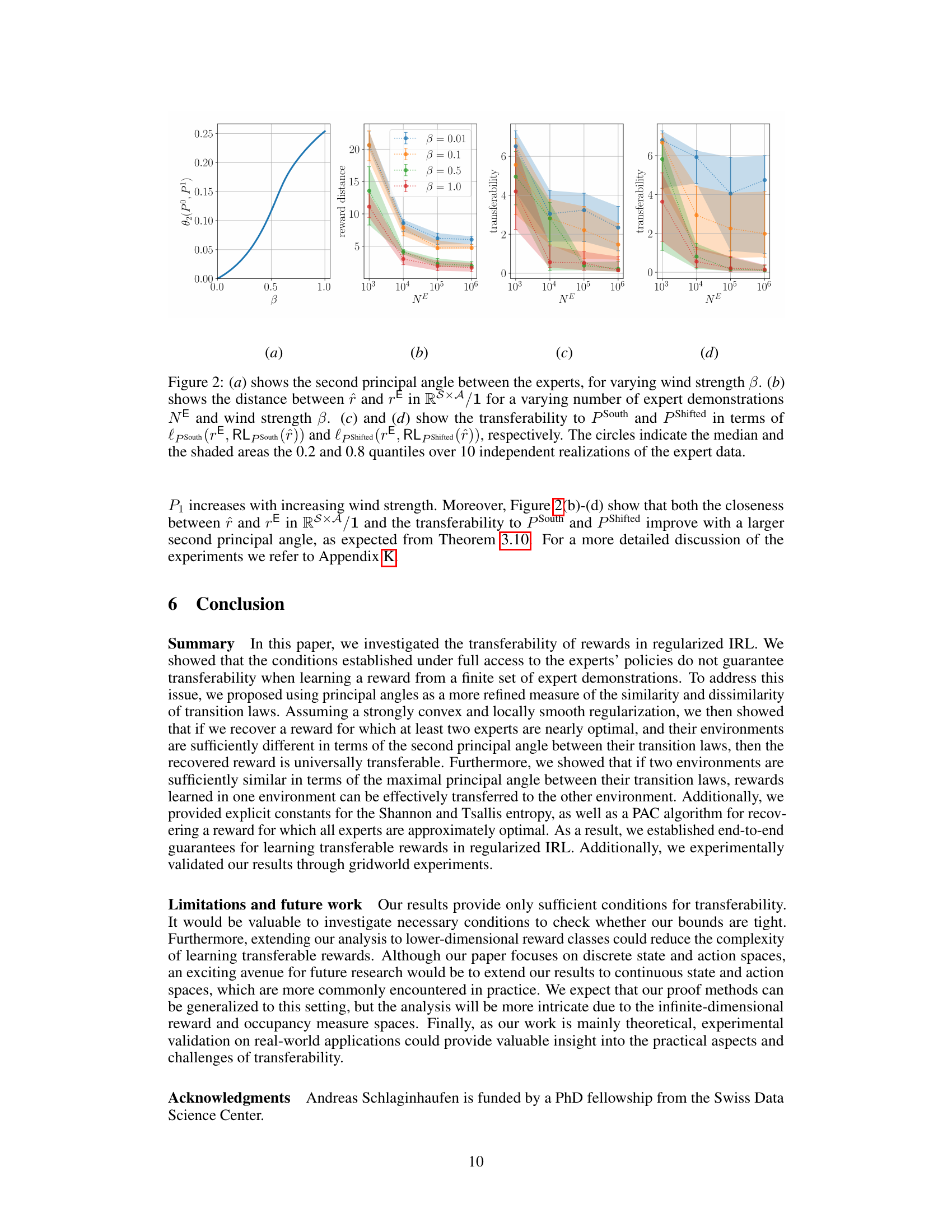

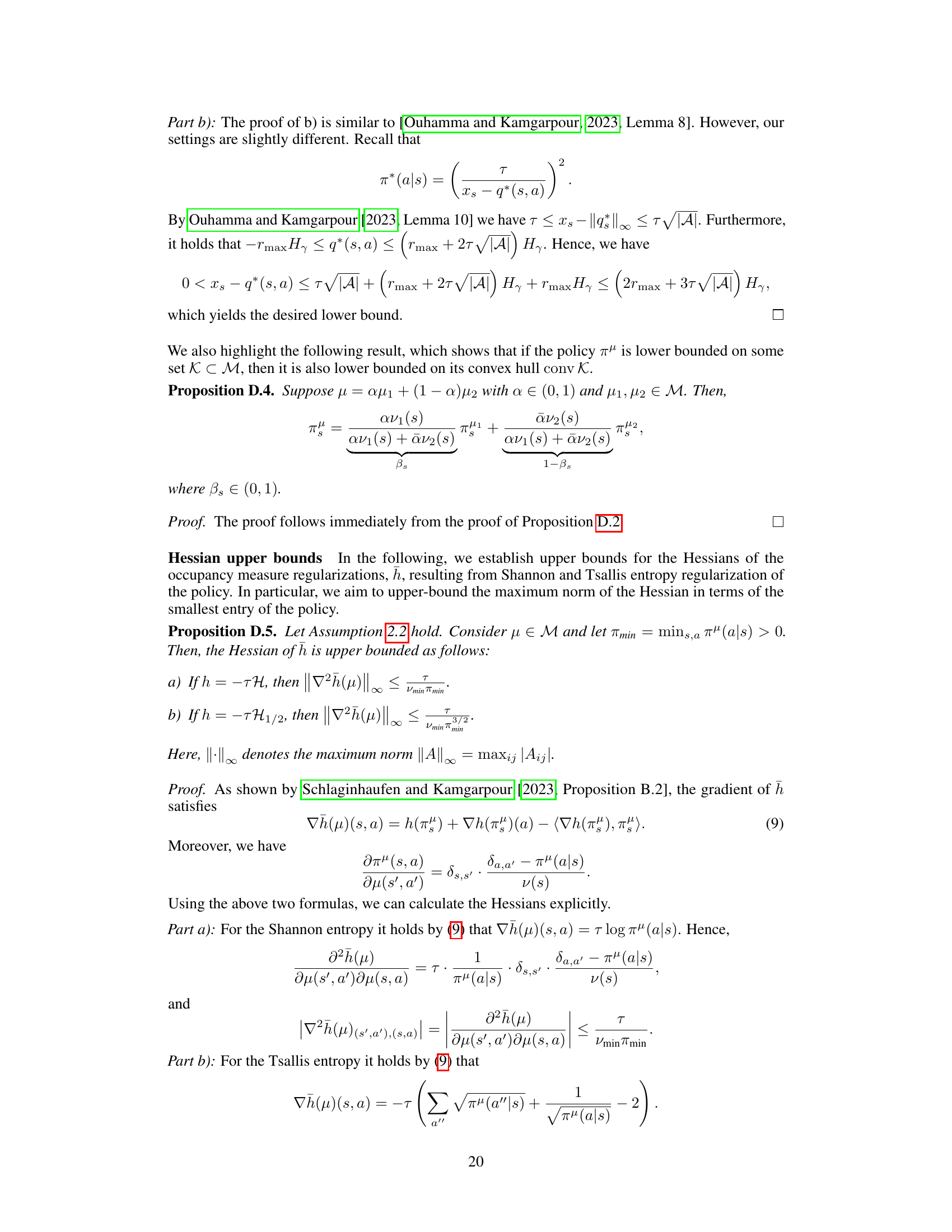

🔼 Figure 2 shows the results of experiments conducted to validate the transferability of rewards in a WindyGridworld environment. The plots illustrate how the second principal angle between two experts, the distance between the recovered reward and the true reward, and the transferability to different environments (with south wind and cyclically shifted actions) vary with changes in wind strength (β) and the number of expert demonstrations (NE). The shaded regions represent the 20th and 80th percentiles across 10 independent trials, demonstrating the variability of the results.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the second principal angle between the experts, for varying wind strength β. (b) shows the distance between r̂ and rE in RS×A/1 for a varying number of expert demonstrations NE and wind strength β. (c) and (d) show the transferability to PSouth and PShifted in terms of lpSouth(rE, RLpSouth(r̂)) and lpShifted(rE, RLpShifted(r̂)), respectively. The circles indicate the median and the shaded areas the 0.2 and 0.8 quantiles over 10 independent realizations of the expert data.

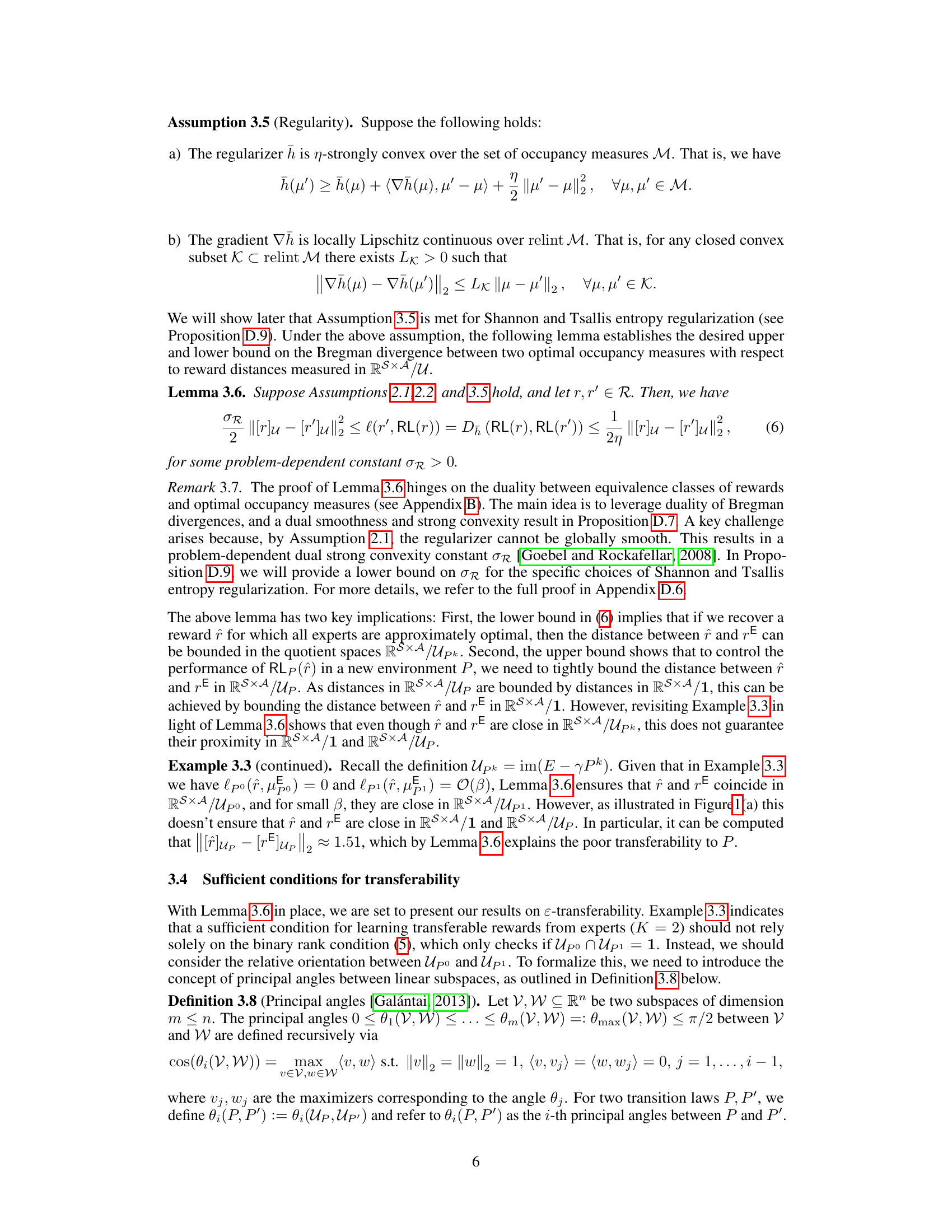

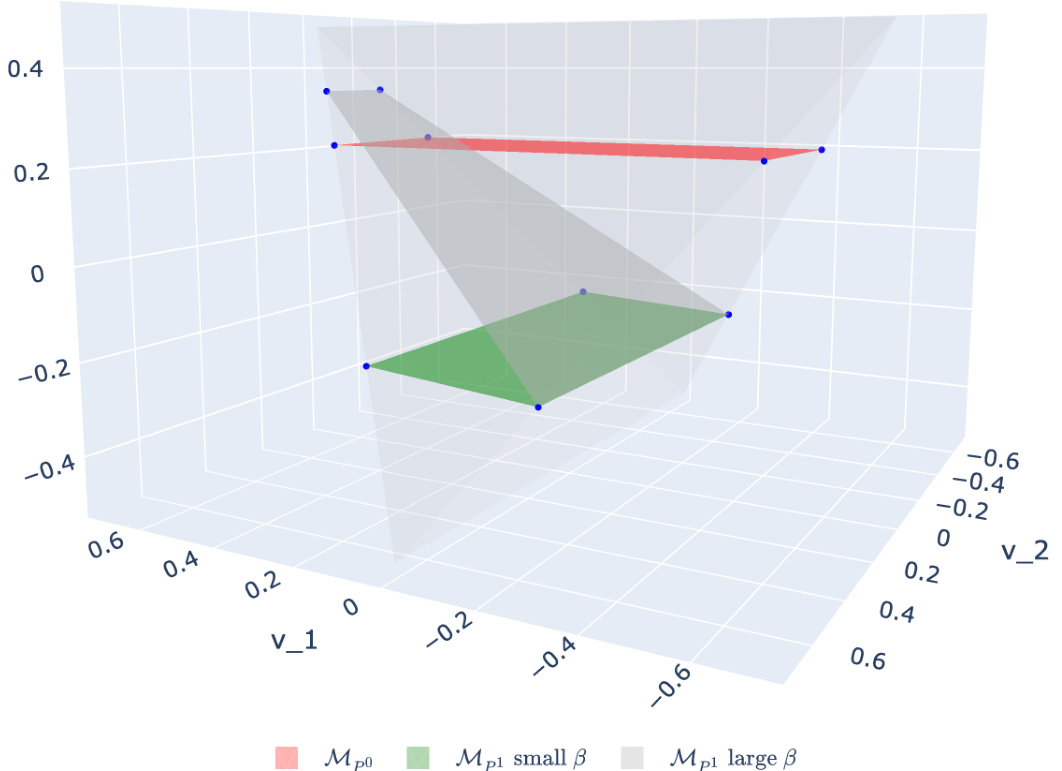

🔼 This figure shows the set of occupancy measures for two different transition laws (P⁰ and P¹), in the quotient space RS×A/1 (which is isomorphic to R¹ in this case). For a small β (parameter controlling the difference between the transition laws), the sets of occupancy measures Mpo and Mp1 are almost parallel, indicating high similarity between the transition laws. Conversely, as β increases, the sets become less parallel, visually representing increasing dissimilarity between P⁰ and P¹. The caption explains that this angle between the sets’ normal vectors (which are closely related to the potential shaping spaces Upo and Up1) is what really matters in determining the transferability of rewards learned via IRL.

read the caption

Figure 3: The set of occupancy measures Mpo and Mp1 are illustrated in RS×A/1 ≈ R¹. For a two-state-two-action MDP, the set of occupancy measures is given by the intersection of a two-dimensional affine subspace (a plane in RS×A/1) with the probability simplex in R⁴ (a tetrahedron in RS×A/1). We see that for a small β, the sets Mpo and Mp1 are approximately parallel. That is, the angle between their normal vectors, which span the potential shaping spaces Upo and Up1, is small. In contrast, for a large β the orientation of Mpo and Mp1 is very different, resulting in a large angle between the corresponding normal vectors.

🔼 Figure 2 shows the results of experiments on a WindyGridworld environment. Subfigure (a) shows how the second principal angle between two experts changes with wind strength. Subfigures (b), (c), and (d) show how reward distance and transferability to two different test environments change with the number of expert demonstrations and wind strength. The results show that increased wind strength leads to larger second principal angles, resulting in better transferability.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the second principal angle between the experts, for varying wind strength β. (b) shows the distance between r̂ and rE in RS×A/1 for a varying number of expert demonstrations NE and wind strength β. (c) and (d) show the transferability to PSouth and PShifted in terms of lPSouth(rE, RLPSouth(r̂)) and lPShifted(rE, RLPShifted(r̂)), respectively. The circles indicate the median and the shaded areas the 0.2 and 0.8 quantiles over 10 independent realizations of the expert data.

Full paper#