TL;DR#

Many machine learning applications rely on solving the submodular maximization problem, a computationally challenging task. Existing algorithms often face a difficult trade-off: either strong theoretical guarantees (high approximation ratios) but impractical computational cost, or practical efficiency but weaker guarantees. This makes deploying these algorithms in real-world applications difficult.

This research introduces a novel algorithm that tackles this trade-off head-on. The algorithm combines a 0.385-approximation ratio (better than existing practical options) with a low query complexity of O(n + k²), improving both practical efficiency and theoretical guarantees. This was empirically validated via experiments across movie recommendation, image summarization, and revenue maximization applications, showcasing superior performance against current state-of-the-art algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and optimization. It significantly advances the state-of-the-art in submodular maximization, a problem fundamental to many applications. By offering a practically efficient algorithm with improved approximation guarantees, it opens doors for broader adoption of these techniques and inspires further research into developing even more efficient and effective algorithms for similar problems.

Visual Insights#

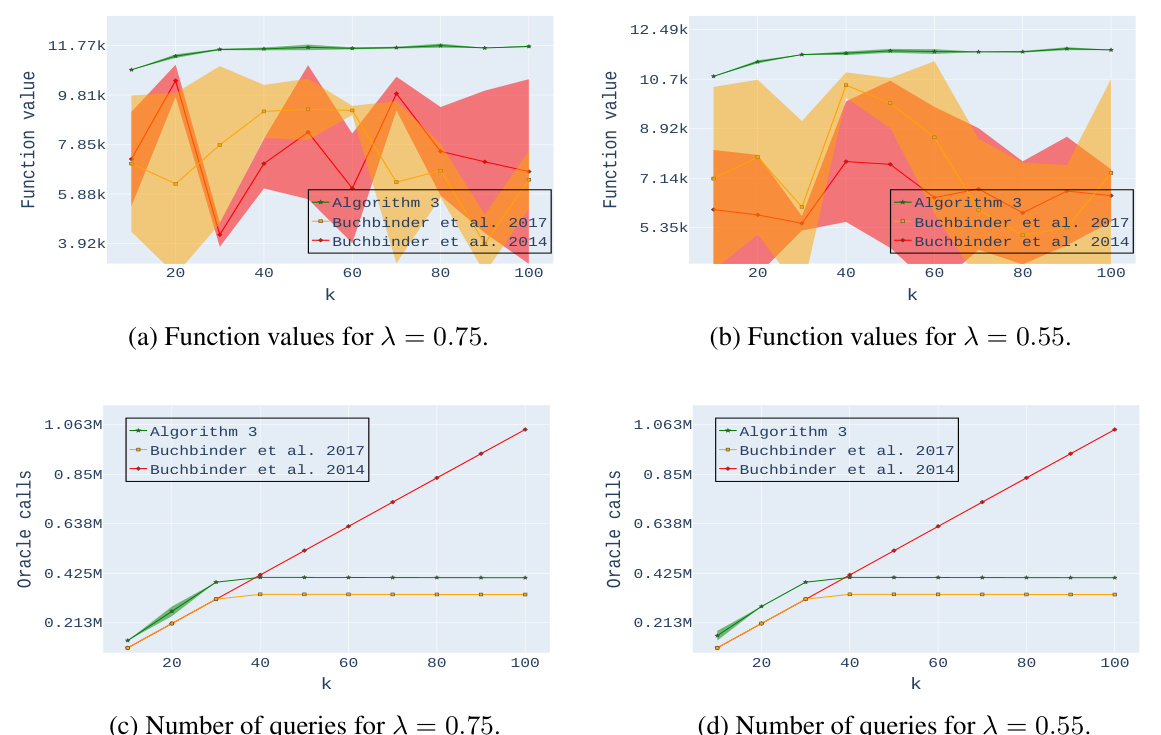

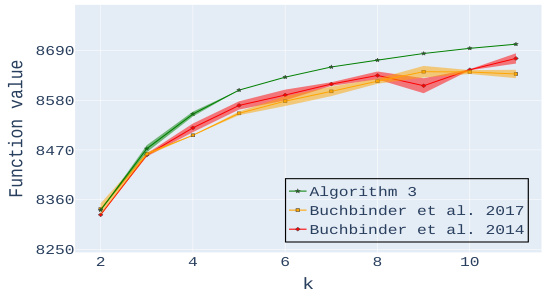

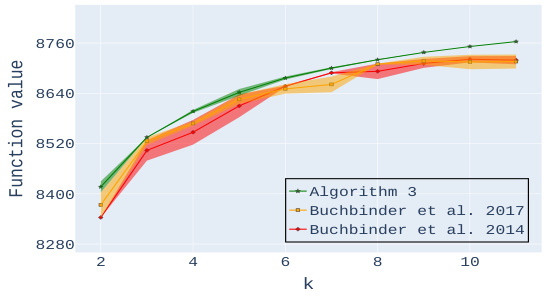

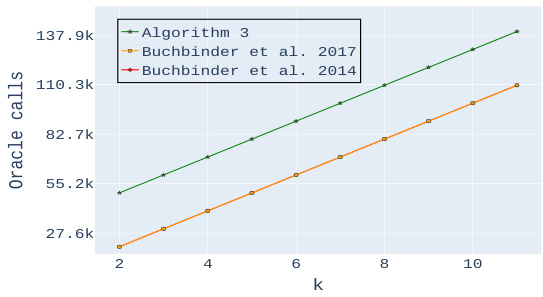

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments on a movie recommendation task. Plots (a) and (b) compare the function values achieved by the proposed algorithm (Algorithm 3) and two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014) for different values of k (the number of movies) and λ (a parameter controlling the balance between coverage and diversity). Plots (c) and (d) show the corresponding number of oracle calls (queries to the objective function) made by each algorithm. The results show that Algorithm 3 consistently outperforms the benchmark algorithms in terms of function value, while using a comparable or even smaller number of queries.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments on a personalized movie recommendation task. It compares the performance of the proposed algorithm (Algorithm 3) against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2014 and 2017) across different values of k (the number of movies) and λ (a parameter controlling the importance of diversity). Plots (a) and (b) show the function values (quality of the movie subsets) obtained by each algorithm, while (c) and (d) display the number of oracle queries (objective function evaluations) required by each method.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

In-depth insights#

Submodular Max#

The heading ‘Submodular Max’ likely refers to the optimization problem of maximizing a submodular function. Submodular functions, exhibiting the property of diminishing returns, are prevalent in various machine learning applications such as data summarization, feature selection, and influence maximization. The core challenge in ‘Submodular Max’ lies in efficiently finding a subset of elements that maximizes the submodular function, often subject to constraints like cardinality limitations (subset size). Algorithms designed for ‘Submodular Max’ often balance approximation guarantees (how close the solution is to the true optimum) and computational complexity. Greedy algorithms are common approaches, known for efficiency but potentially suboptimal results. More sophisticated algorithms aim for better approximations, sometimes at the cost of increased complexity. The research in this area explores new algorithms improving the tradeoff between the approximation ratio and the computational cost, often focusing on addressing non-monotone submodular functions, which add significant challenges.

0.385 Approx Algo#

The heading ‘0.385 Approx Algo’ likely refers to a novel 0.385-approximation algorithm presented in the research paper for solving a submodular maximization problem with cardinality constraints. This algorithm is significant because it offers a strong approximation guarantee (0.385) while maintaining practical efficiency. Existing algorithms often struggle with a trade-off between these two aspects; highly accurate methods are computationally expensive, whereas faster ones sacrifice accuracy. The paper’s contribution lies in achieving a balance, offering a substantial improvement over the previously best practical algorithms (achieving only a 1/e approximation) and also improving upon the state-of-the-art theoretical algorithm, which, despite offering superior approximation ratio, is too computationally expensive to be practical. The algorithm’s effectiveness likely gets validated empirically by the authors through experiments on real-world machine learning applications, demonstrating that its superior theoretical guarantees translate into significant performance gains. The practical query complexity of O(n+k²) is also crucial, indicating the algorithm’s scalability for large datasets where n represents the data size and k is the solution’s maximum size.

Empirical Eval#

An empirical evaluation section in a research paper is crucial for validating theoretical claims. It should present a robust methodology, clearly describing datasets used, metrics employed, and baseline algorithms for comparison. A strong empirical evaluation would demonstrate the proposed method’s performance advantages over existing state-of-the-art approaches. The results should be statistically sound, using proper error bars and significance tests to support claims. Visualizations, such as graphs and tables, are important for conveying the results effectively and highlighting key trends. Clear explanations of parameter choices and experimental setups ensure reproducibility. It is also vital to address limitations of the experiments and discuss any potential confounding factors that could influence the results. A comprehensive analysis that incorporates both quantitative and qualitative insights enhances the overall trustworthiness and impact of the findings. Finally, a discussion on the generalizability of the results to different settings or larger-scale applications is crucial for the paper’s long-term value.

Future Work#

Future work in this area could explore several promising avenues. Improving the query complexity of the algorithm beyond O(n+k²) to achieve a truly linear time algorithm is a significant goal. This would require innovative techniques to reduce the number of function evaluations required while maintaining the approximation guarantee. Extending the algorithm to handle more complex constraints such as multiple matroids or more general constraints would broaden its applicability. Investigating the theoretical limitations of the 0.385 approximation ratio, determining if it is tight or if further improvement is possible, would be a valuable contribution. Developing robust heuristics to improve practical performance would complement the theoretical results and make the algorithm even more efficient in real-world scenarios. Finally, a comprehensive study across a wider range of applications, including those with non-standard submodular functions, would demonstrate its effectiveness and versatility.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the ‘Limitations’ section of a research paper necessitates a thorough examination of potential shortcomings. Missing limitations significantly weaken the paper’s credibility, as it implies an oversight in acknowledging potential flaws or alternative interpretations of the presented data. Conversely, a comprehensive discussion of limitations, acknowledging the study’s scope, methodological constraints, and underlying assumptions, enhances transparency and allows for a more nuanced understanding of the study’s contributions. The presence of limitations is not inherently negative; rather, a well-articulated acknowledgment demonstrates critical engagement and fosters a more robust interpretation. Overly broad limitations, however, could undermine the study’s overall contribution by suggesting a lack of specific, actionable insights. Specific, well-defined limitations, on the other hand, contribute to the overall impact, indicating the authors’ self-awareness and providing avenues for future research. Ultimately, a well-crafted ‘Limitations’ section ensures the paper’s results are placed in proper context, fostering trust and promoting a more objective analysis of the work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

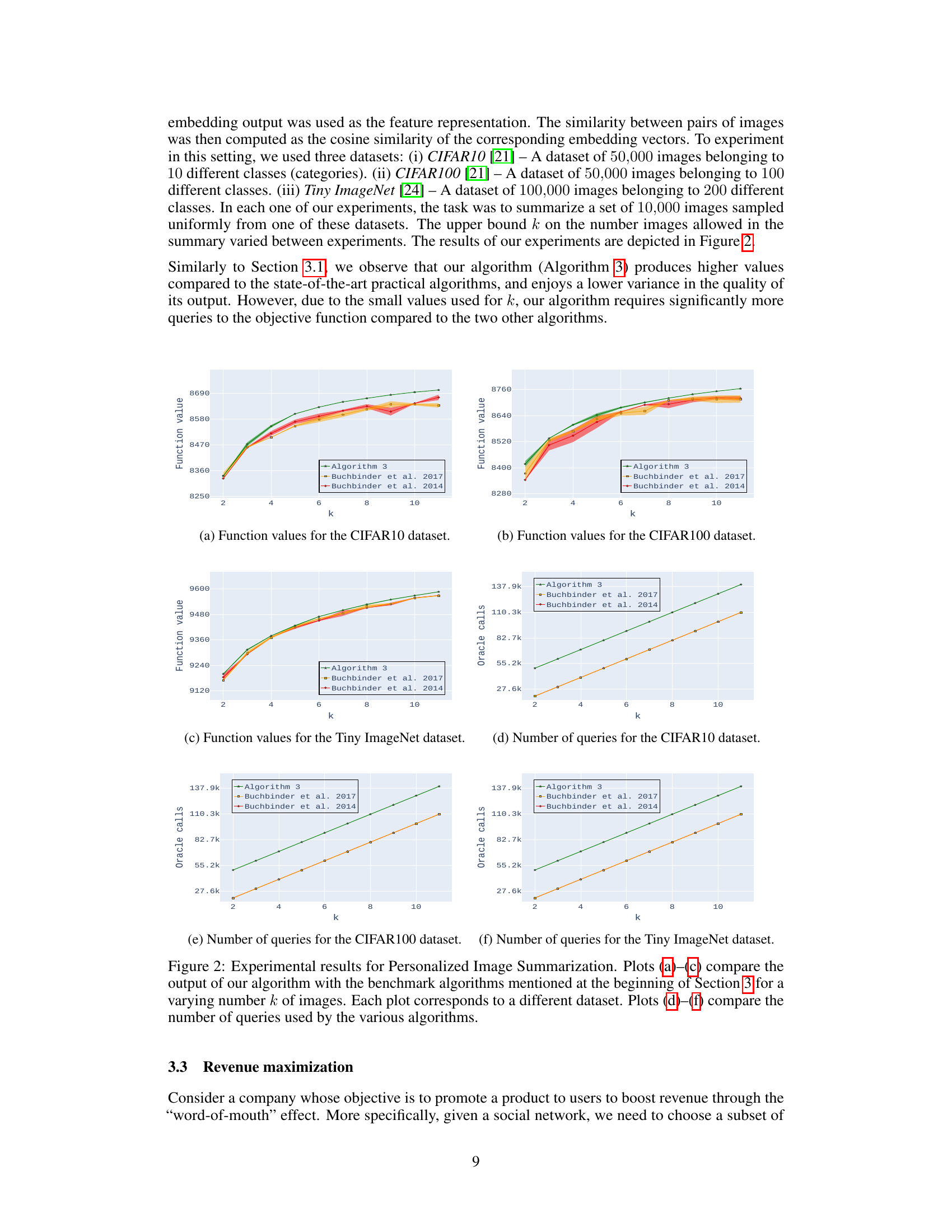

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results for the personalized image summarization task, comparing the performance of the proposed Algorithm 3 against two benchmark algorithms: Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014. The results are shown across three different datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and Tiny ImageNet), varying the maximum number of images (k) allowed in the summary. Plots (a)-(c) display the function values achieved by each algorithm for different values of k on each dataset, illustrating the superior performance of Algorithm 3 in terms of output quality and stability. Plots (d)-(f) compare the number of queries required by each algorithm to achieve these results, showing the query efficiency of Algorithm 3, especially when k is larger.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experimental results for Personalized Image Summarization. Plots (a)-(c) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a varying number k of images. Each plot corresponds to a different dataset. Plots (d)-(f) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed algorithm (Algorithm 3) against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al., 2014 and Buchbinder et al., 2017) for the personalized movie recommendation task. Plots (a) and (b) show the function values achieved by each algorithm for different values of k (the number of movies selected), with plots (c) and (d) showing the corresponding number of queries to the objective function required by each method. The results demonstrate that Algorithm 3 achieves higher function values and lower variance in performance compared to the benchmark algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results for the Personalized Movie Recommendation task. Plots (a) and (b) show a comparison of the function values achieved by Algorithm 3 and two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014) for different values of k (the number of movies selected) and two different values of λ (diversity parameter). Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries required by each algorithm to achieve these results, indicating efficiency differences.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments on personalized image summarization using three different datasets (CIFAR10, CIFAR100, and Tiny ImageNet). The plots compare the performance of Algorithm 3 against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014) in terms of function value and number of oracle queries. The function value represents the quality of the generated summary, while the number of oracle queries reflects the computational efficiency. The results show Algorithm 3 consistently outperforms the benchmarks in function value, although it requires more queries.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experimental results for Personalized Image Summarization. Plots (a)-(c) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a varying number k of images. Each plot corresponds to a different dataset. Plots (d)-(f) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results for the Personalized Image Summarization task. It compares the performance of Algorithm 3 against two other benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al., 2014 and Buchbinder et al., 2017). The comparison is done across three different image datasets (CIFAR10, CIFAR100, and Tiny ImageNet) and for different values of k (the maximum number of images in the summary). Plots (a)-(c) show the function values (quality of the summarization) achieved by each algorithm for each dataset and k value. Plots (d)-(f) display the number of oracle calls (queries to the objective function) required by each algorithm for each dataset and k value.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experimental results for Personalized Image Summarization. Plots (a)-(c) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a varying number k of images. Each plot corresponds to a different dataset. Plots (d)-(f) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure displays the performance comparison between Algorithm 3 (the proposed algorithm) and two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al., 2017 and Buchbinder et al., 2014) in terms of both objective function value and the number of oracle calls (queries) required. The experiments are conducted on three datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and Tiny ImageNet, each with a varying number of images (k). The plots (a)-(c) show the objective function values achieved by each algorithm across different values of k for each dataset. The plots (d)-(f) show the number of queries made by each algorithm for each dataset and value of k. The results demonstrate the superiority of Algorithm 3 in achieving higher objective function values with a relatively low number of queries, particularly as k increases.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experimental results for Personalized Image Summarization. Plots (a)-(c) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a varying number k of images. Each plot corresponds to a different dataset. Plots (d)-(f) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results for the personalized movie recommendation task. Plots (a) and (b) show a comparison of the function values achieved by the proposed Algorithm 3 and two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014) across different values of k (the number of movies) and two different values of λ (a parameter that controls the balance between coverage and diversity in the selected movie set). Plots (c) and (d) show the number of oracle queries required by each algorithm for the same range of k values and the two λ values. The results indicate that Algorithm 3 performs better than the benchmarks, with a smaller variance in the function values, and a comparable number of queries to the best-performing benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

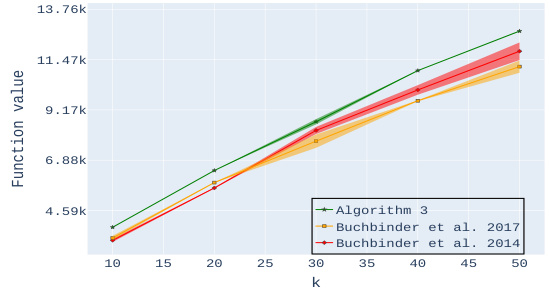

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of the proposed Algorithm 3 against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014) for a revenue maximization problem. Plots (a) and (b) show the function values achieved by each algorithm for different values of k (the maximum number of users to select) on the Advogato and Facebook network datasets respectively. Plots (c) and (d) show the number of queries required by each algorithm for the same experiments, indicating computational efficiency. The results demonstrate the superior performance and lower variance of the proposed Algorithm 3 in both revenue and query count.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experimental results for Revenue Maximization. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a varying number k of images on the Advogato and Facebook network datasets. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Algorithm 3 (the proposed algorithm) against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al., 2017 and Buchbinder et al., 2014) in a movie recommendation task. Plots (a) and (b) show the function values achieved by each algorithm for different values of k (the number of movies) and λ (a parameter controlling the importance of diversity). Plots (c) and (d) show the number of oracle queries (function evaluations) required by each algorithm for the same settings.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments conducted for a personalized movie recommendation task. The experiments compare the performance of the proposed algorithm (Algorithm 3) against two benchmark algorithms (Buchbinder et al. 2017 and Buchbinder et al. 2014). Plots (a) and (b) show the function values achieved by each algorithm for different values of k (the number of movies selected), with the parameter λ (controlling the balance between coverage and diversity) set to 0.75 and 0.55 respectively. Plots (c) and (d) illustrate the number of oracle calls (queries to the objective function) required by each algorithm for different values of k.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results for Personalized Movie Recommendation. Plots (a) and (b) compare the output of our algorithm with the benchmark algorithms mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 for a particular value of the parameter λ and a varying number k of movies. Plots (c) and (d) compare the number of queries used by the various algorithms.

Full paper#