↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

In-context learning (ICL), where models learn from examples without parameter updates, is a significant area in machine learning. While prior research suggests Transformers might approximate gradient descent during ICL, this paper challenges that notion. A core issue is understanding the mechanism behind Transformers’ success in ICL, particularly its efficiency and ability to handle complex data. Previous models primarily focused on first-order methods, limiting the understanding of Transformers’ unique learning capabilities.

This research investigated Transformers’ behavior in the context of linear regression. The researchers found that, contrary to expectations, Transformers do not perform gradient descent. Instead, they approximate second-order optimization methods, exhibiting convergence rates similar to Iterative Newton’s Method—significantly faster than gradient descent. This is supported by both empirical observations matching Transformer layers to Newton’s Method iterations and a theoretical proof. The findings also demonstrate the robustness of Transformers to ill-conditioned data, a scenario where gradient descent often struggles.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the prevailing assumption that Transformers perform in-context learning through gradient descent, offering a novel perspective and opening avenues for more efficient and powerful algorithms. It also demonstrates that Transformers’ in-context learning ability extends to ill-conditioned data, a setting where gradient-based methods often struggle. This expands our understanding of Transformers’ capabilities and could lead to improvements in various machine learning applications.

Visual Insights#

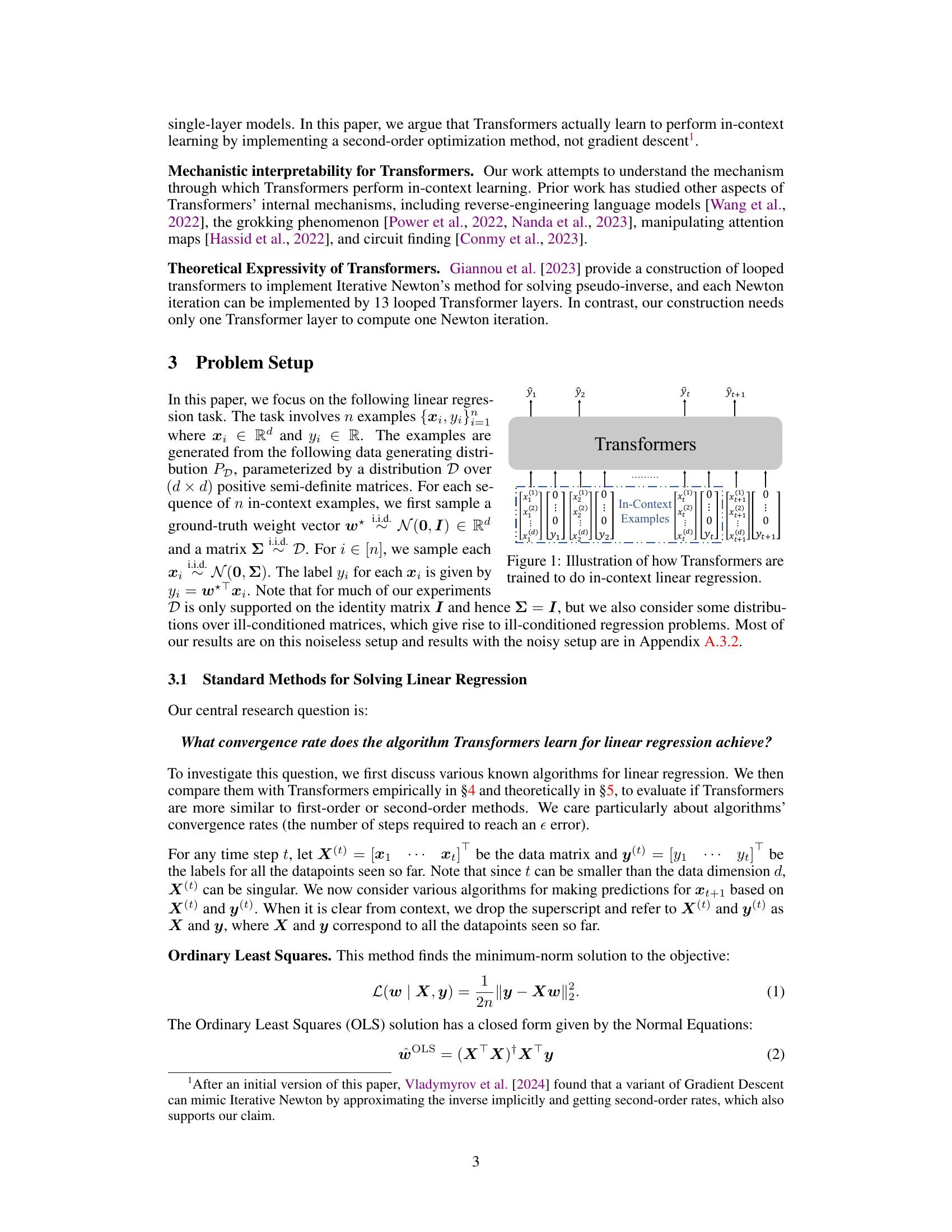

This figure illustrates the in-context learning process for linear regression using Transformers. The input consists of a sequence of in-context examples, where each example is a pair of input features (x) and its corresponding output label (y). These examples are presented to the transformer model, which then learns to make predictions on new unseen input data (xt+1) without explicit parameter updates. The figure shows how the Transformer processes the input examples and generates a prediction for the new input data, effectively performing in-context learning.

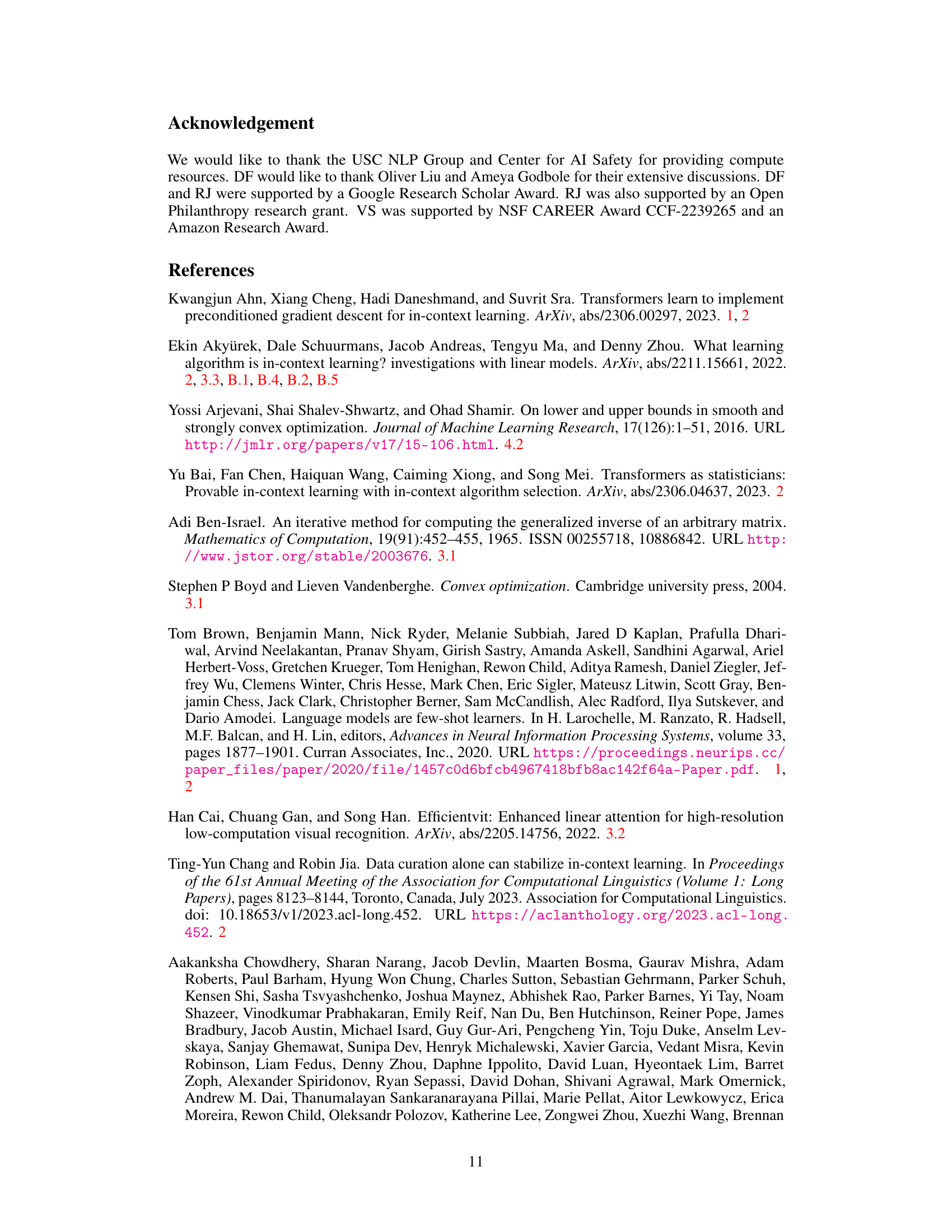

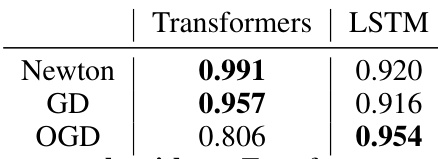

This table presents the cosine similarity scores between the prediction errors of Transformers and LSTMs against those of three different linear regression algorithms: Iterative Newton’s Method, Gradient Descent, and Online Gradient Descent. Higher scores indicate greater similarity. The results show that Transformers’ error patterns are much more closely aligned with those of Newton’s Method and Gradient Descent (full-observation methods), whereas LSTMs are more similar to Online Gradient Descent (an online learning method). This supports the paper’s argument that Transformers learn to approximate second-order optimization methods.

In-depth insights#

Transformer ICL#

The concept of “Transformer ICL” (In-Context Learning) investigates how transformer-based models, known for their success in natural language processing, achieve impressive performance on tasks without explicit parameter updates during the learning phase. Key insights revolve around the idea that transformers implicitly perform optimization algorithms, potentially approximating second-order methods like Iterative Newton’s Method rather than first-order methods like Gradient Descent. This contrasts with previous hypotheses suggesting a reliance on first-order optimization. Empirical evidence supports the claim of second-order approximation, showing a faster convergence rate similar to Iterative Newton’s Method in linear regression tasks. This is further corroborated by theoretical analysis demonstrating the capacity of transformer architectures to implement specific iterative optimization steps within their layered structure. The finding that transformers excel even on ill-conditioned data (where gradient descent struggles) further reinforces the idea of a second-order mechanism at play. However, limitations still exist, particularly the need for a larger number of layers compared to the theoretical minimum to implement the full iterative optimization, highlighting areas for future investigation. Overall, the exploration of “Transformer ICL” provides a deeper mechanistic understanding of these models’ capabilities, moving beyond the simple gradient descent narrative.

Second-Order Opt#

The concept of “Second-Order Opt,” likely referring to second-order optimization methods in the context of transformer neural networks, presents a compelling alternative to the prevailing first-order (gradient descent) perspective on in-context learning. Second-order methods, such as Newton’s method, leverage curvature information to achieve faster convergence, making them particularly attractive for complex learning tasks. The paper likely explores how transformers, despite their inherent architecture, might implicitly or explicitly emulate these sophisticated methods. This contrasts with simpler gradient-based explanations, potentially offering a deeper understanding of transformers’ remarkable performance in few-shot learning. The research would likely include empirical evidence demonstrating the similarity between transformers’ layer-wise updates and the iterative steps of a second-order algorithm, possibly using metrics like error convergence rates or similarity in induced weight vectors. Furthermore, theoretical analysis might delve into the computational capabilities of transformer architectures to implement second-order algorithms, possibly showing how certain layer configurations could approximate iterative methods with a polynomial number of layers. This would be a significant advancement, providing a more complete and mechanistic explanation of transformers’ learning behavior.

Algorithmic Sim#

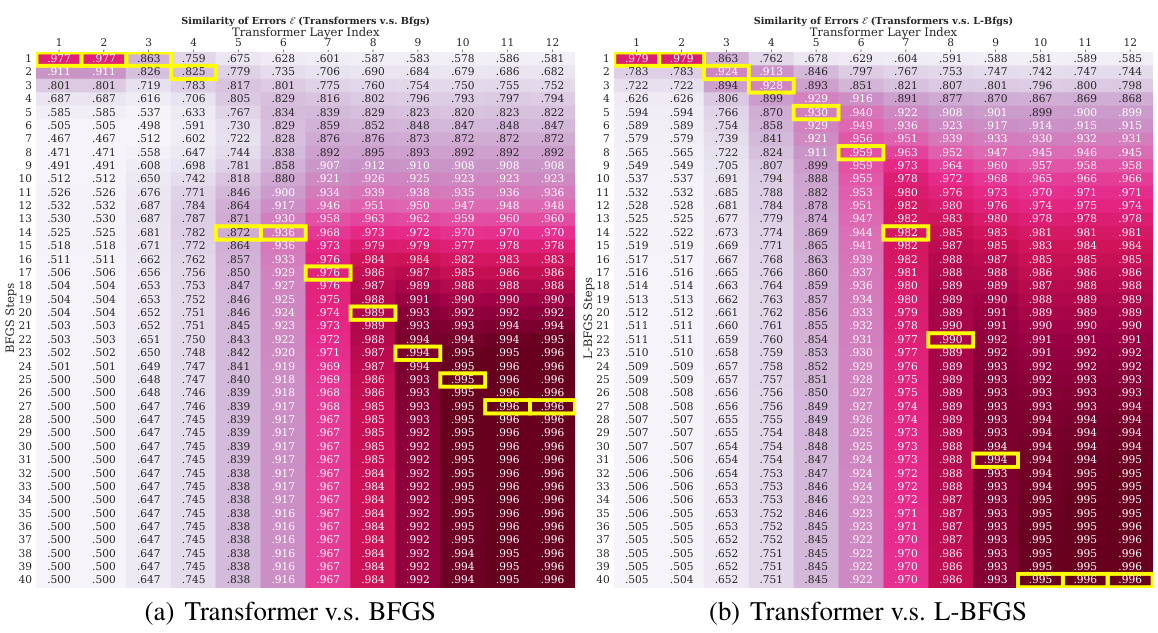

An in-depth analysis of ‘Algorithmic Similarity’ in a research paper would explore the methods used to compare the behavior of different algorithms. This likely involves defining metrics to quantify similarity, such as comparing prediction errors or analyzing the convergence rate. The choice of metrics is crucial, as it dictates what aspects of algorithmic behavior are considered important. A sophisticated approach might incorporate multiple metrics, capturing both quantitative and qualitative differences. Visualizations, such as heatmaps, could also reveal underlying patterns and relationships between algorithms, potentially highlighting unexpected similarities or differences. Furthermore, the analysis might delve into the theoretical underpinnings of the chosen metrics, examining their limitations and assumptions. A thorough investigation could uncover whether algorithms, despite structural differences, exhibit similar underlying mechanisms, hinting at unifying principles or suggesting potential avenues for algorithmic improvement or refinement. Finally, the study could investigate the robustness of the similarity metrics across diverse datasets or problem settings, establishing the generalizability of the findings.

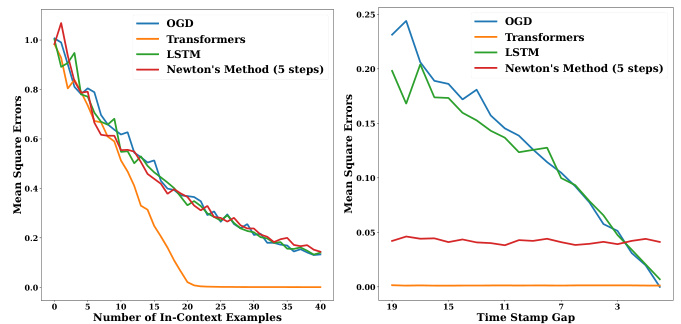

Ill-Conditioned Data#

The section on ill-conditioned data is crucial because it tests the robustness of the model’s approach. Ill-conditioned data, where the input features are highly correlated or linearly dependent, poses a significant challenge to many optimization algorithms, including gradient descent. The authors’ experiments demonstrate that Transformers, unlike gradient descent, are not significantly affected by ill-conditioning. This is a key finding because it highlights the potential advantages of Transformers in real-world applications where data is often noisy, incomplete, and complex. The superior performance under ill-conditioned circumstances is linked to the model’s implicit use of second-order optimization methods, which handle such conditions more effectively than first-order methods. This observation supports the paper’s central hypothesis and underscores the unique learning capabilities of Transformers, making them particularly useful for in-context learning scenarios with suboptimal data.

Future Work#

Future research could explore extending these findings to more complex tasks beyond linear regression, such as classification or natural language processing. Investigating how different Transformer architectures and training regimes affect the learned optimization strategy would also be valuable. A deeper analysis into the role of attention mechanisms and the interaction between layers in approximating higher-order methods is warranted. Further theoretical work to provide a more rigorous proof of convergence and to characterize the limitations of the proposed approximation would strengthen the understanding of the phenomenon. Exploring the effects of various hyperparameter choices on the learned optimization method could reveal important insights into the model’s behavior and inform future model designs. Finally, investigating the relationship between the learned optimization method and the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data is essential for advancing our understanding of in-context learning.

More visual insights#

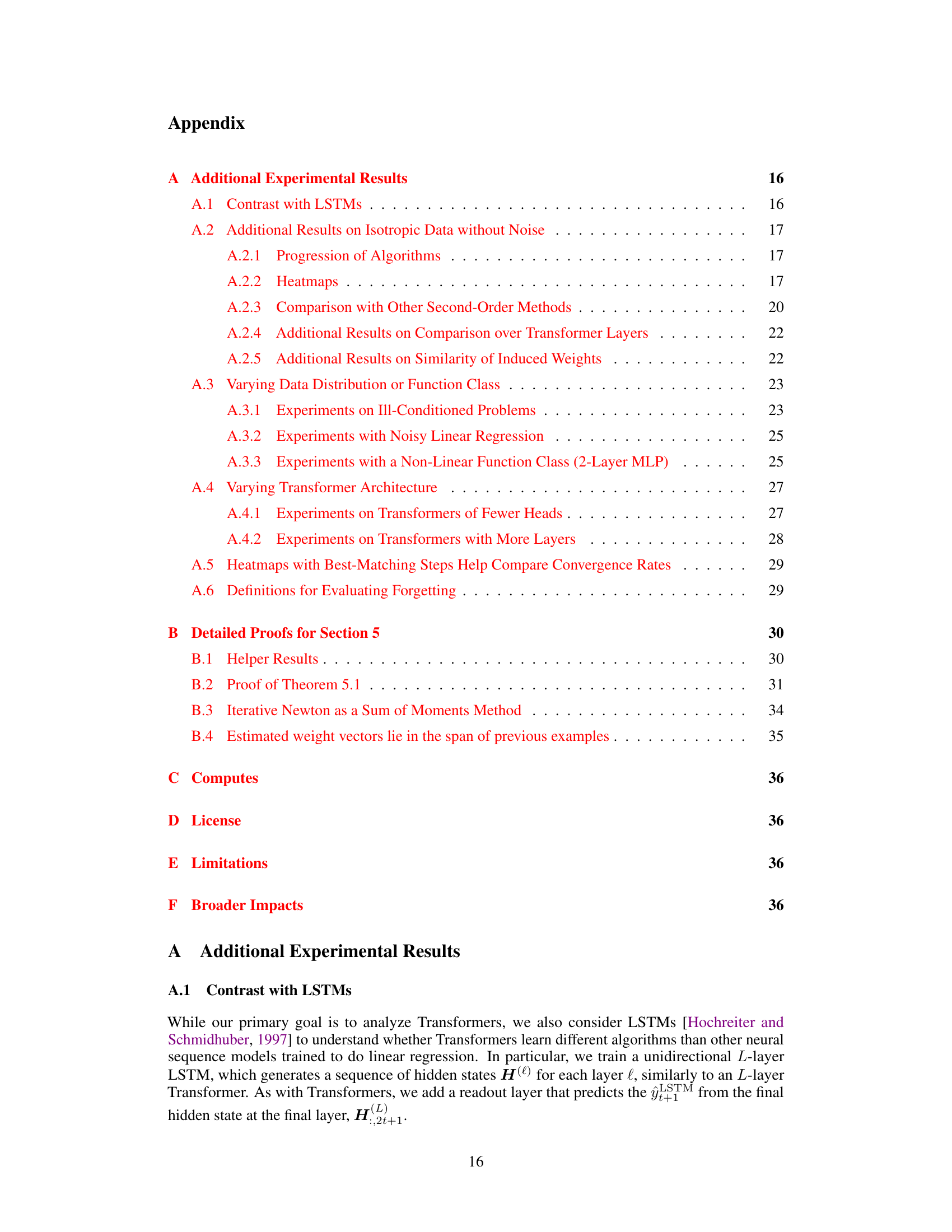

More on figures

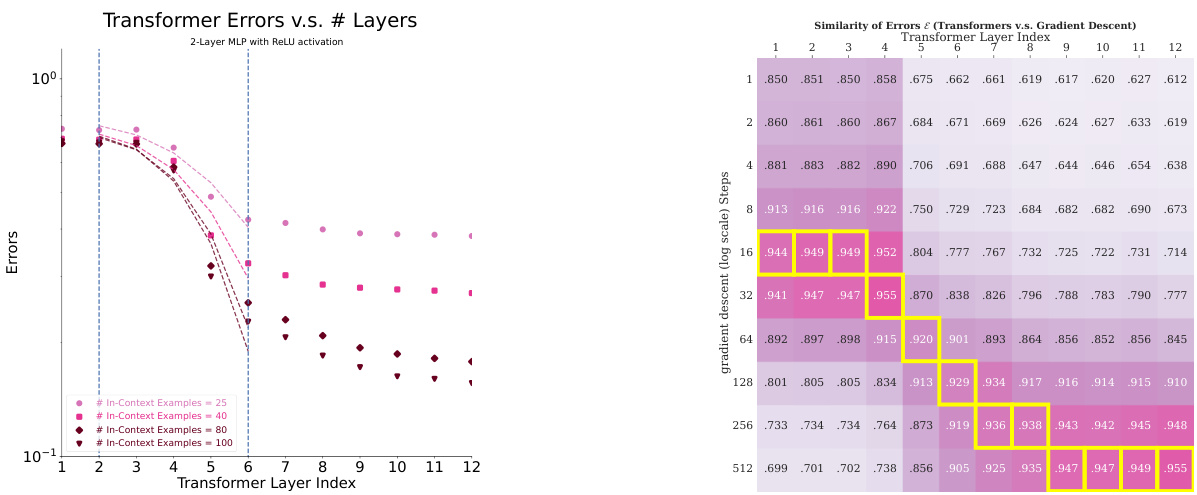

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method exhibit superlinear convergence (meaning that the error decreases faster than linearly with each iteration or layer), while Gradient Descent shows sublinear convergence. The convergence rate of Transformers is similar to that of Iterative Newton’s Method, significantly faster than that of Gradient Descent, especially in the middle layers. Later Transformer layers show a slower convergence, potentially due to the error already being very small, and thus they have little incentive to continue precise optimization.

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression. It shows how the error decreases as the number of layers (Transformers), iterations (Iterative Newton), or steps (Gradient Descent) increases. The results demonstrate that Transformers achieve a superlinear convergence rate similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, which is significantly faster than the sublinear convergence rate of Gradient Descent, especially in the middle layers. Later Transformer layers show slower convergence because the error is already very small.

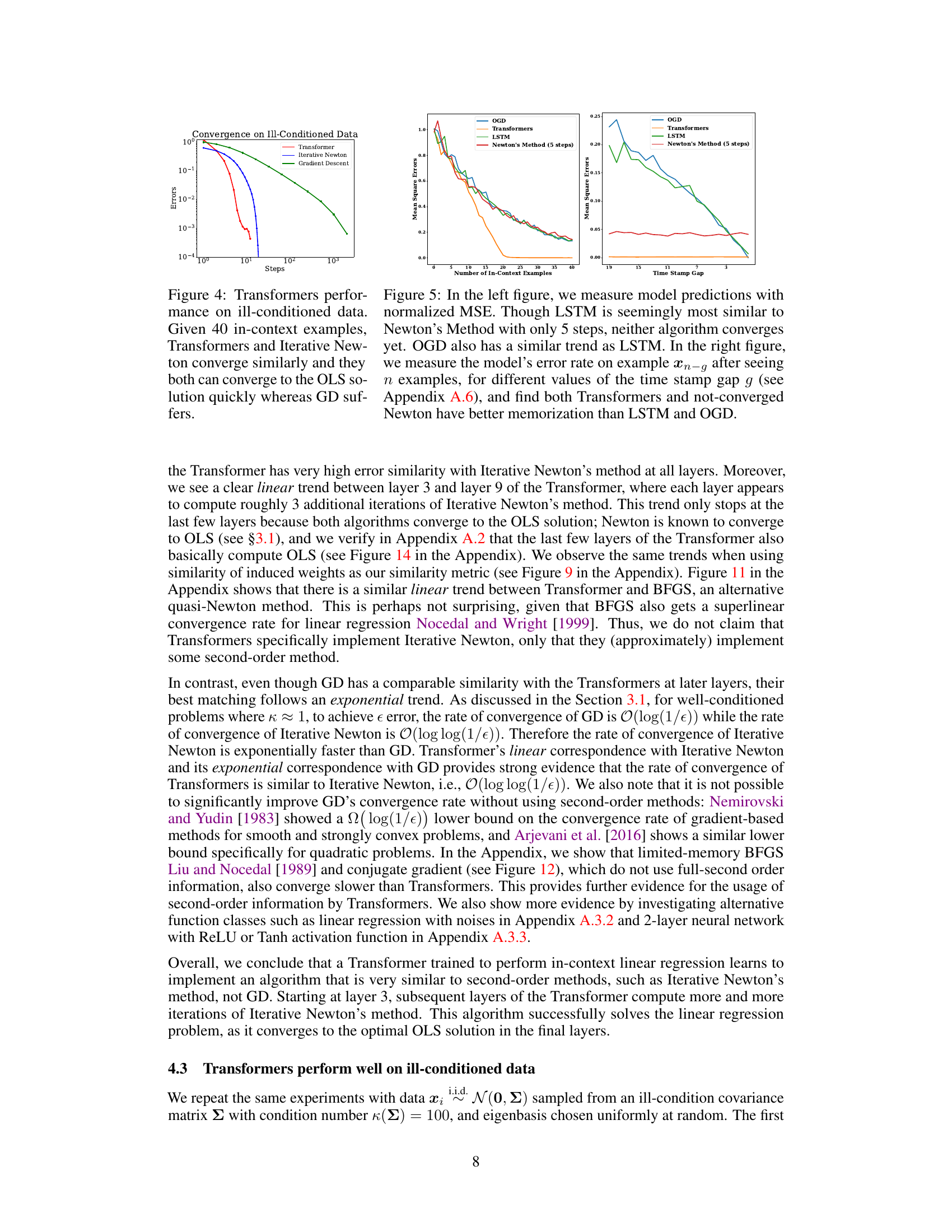

This figure compares the convergence performance of Transformers, Iterative Newton’s method, and Gradient Descent on ill-conditioned data for linear regression. The x-axis represents the number of steps/layers, and the y-axis shows the error. It demonstrates that Transformers and Iterative Newton converge much faster (superlinearly) to the optimal solution (Ordinary Least Squares) than Gradient Descent (sublinearly), even when dealing with ill-conditioned data where Gradient Descent struggles.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression. The x-axis represents the number of layers (Transformers), steps (Iterative Newton’s Method), or steps (Gradient Descent), and the y-axis represents the mean squared error. The figure demonstrates that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method achieve a superlinear convergence rate that’s significantly faster than Gradient Descent, particularly when the number of in-context examples exceeds the data dimensionality (n > d). The plots also show that the predictions of successive Transformer layers closely match Iterative Newton’s method at different iteration steps, indicating that Transformer layers efficiently approximate steps of the second-order optimization method. For comparison, later transformer layers show a slight decrease in convergence speed as the error nears zero. A 24-layer model shows similar behaviour as described in Appendix A.4.2.

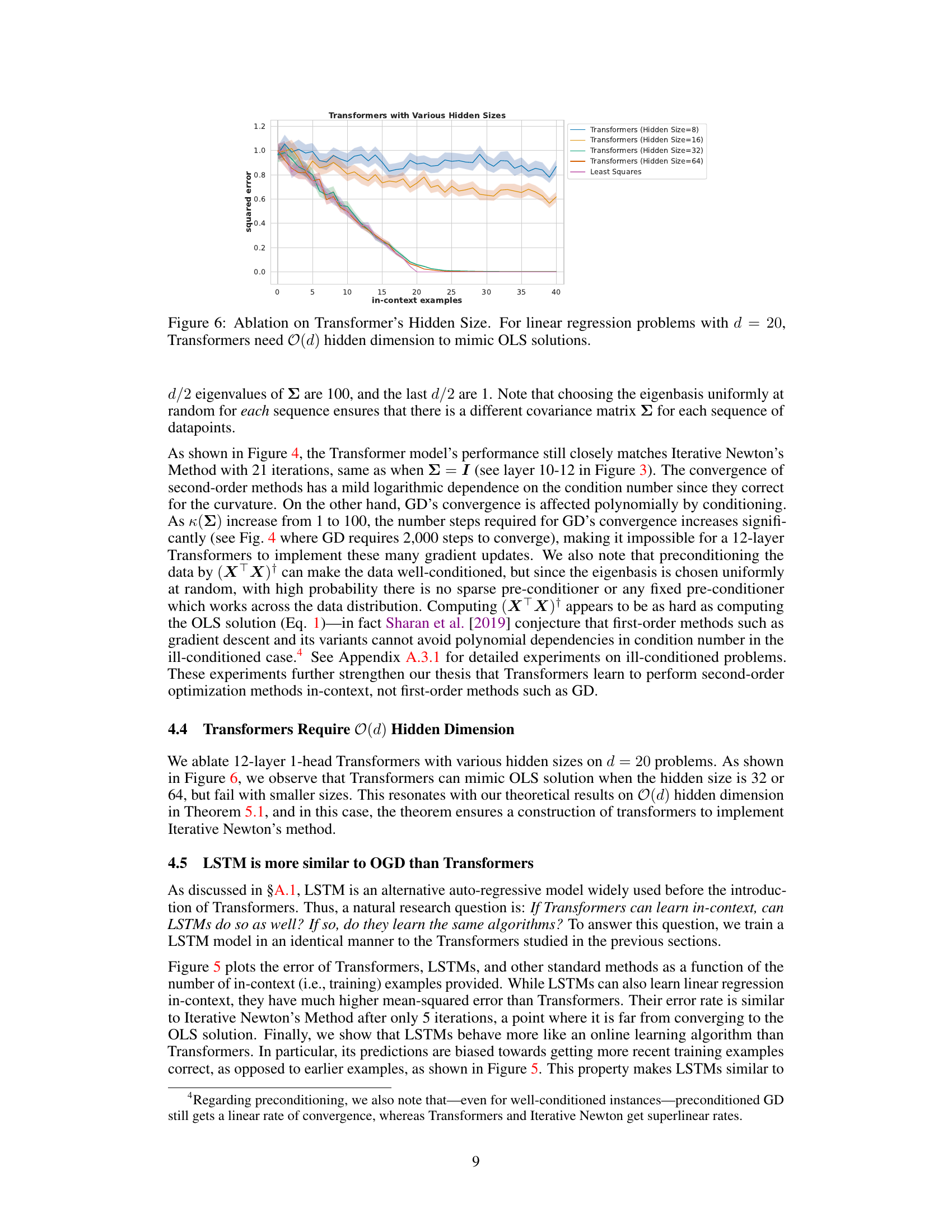

This figure shows the ablation study on the hidden size of the Transformer model for linear regression problems with dimension d=20. The results indicate that Transformers need a hidden dimension of O(d) to accurately approximate the ordinary least squares (OLS) solutions. Smaller hidden sizes lead to significantly higher errors.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that for in-context linear regression tasks where the number of data points exceeds the data dimension, Transformers exhibit superlinear convergence, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, and significantly faster than Gradient Descent’s sublinear convergence. The convergence speed of Transformers slows in later layers, likely because there is less incentive to compute the algorithm precisely when the error is already small.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three different algorithms for linear regression: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that for a sufficiently large number of in-context examples (n > d), the Transformer’s error decreases superlinearly with the layer index, similar to Iterative Newton’s method. Gradient descent, on the other hand, shows sublinear convergence. The figure also suggests that the later layers of the transformer exhibit slower convergence because the error is already very small, thus reducing the incentive to precisely implement the algorithm.

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms (Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent) for in-context linear regression. It shows that Transformers exhibit a superlinear convergence rate similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, significantly faster than the sublinear rate of Gradient Descent, especially in the middle layers (3-8). Later Transformer layers show slower convergence, likely because the error is already small.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that for linear regression problems, as the number of layers in a Transformer increases, its prediction error decreases superlinearly, similarly to Iterative Newton’s Method. Gradient Descent, on the other hand, exhibits a much slower sublinear convergence rate. This suggests that Transformers internally approximate second-order optimization methods.

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that Transformers exhibit a superlinear convergence rate similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, significantly outperforming Gradient Descent, especially in the middle layers. Later Transformer layers show slower convergence, likely because the error is already small.

The figure shows the convergence speed comparison of three algorithms: Transformer, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It plots the error against the number of layers (Transformer), steps (Iterative Newton’s Method), and steps (Gradient Descent). The results demonstrate that the Transformer’s convergence rate is superlinear and similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, significantly faster than Gradient Descent’s sublinear rate, especially in the initial layers. This suggests that Transformers learn second-order optimization strategies.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that as the number of layers increases in the Transformer model (and the number of steps in Iterative Newton’s method), the error decreases superlinearly. Conversely, Gradient Descent shows a much slower, sublinear convergence. The results suggest that Transformers learn to approximate a second-order optimization method, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, rather than a first-order method like Gradient Descent.

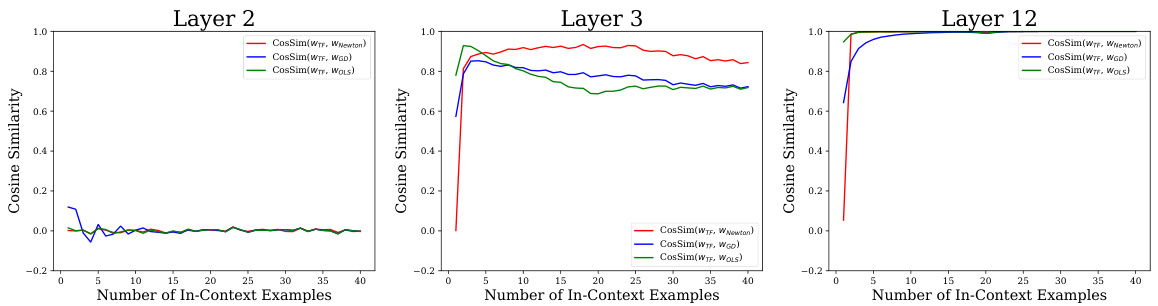

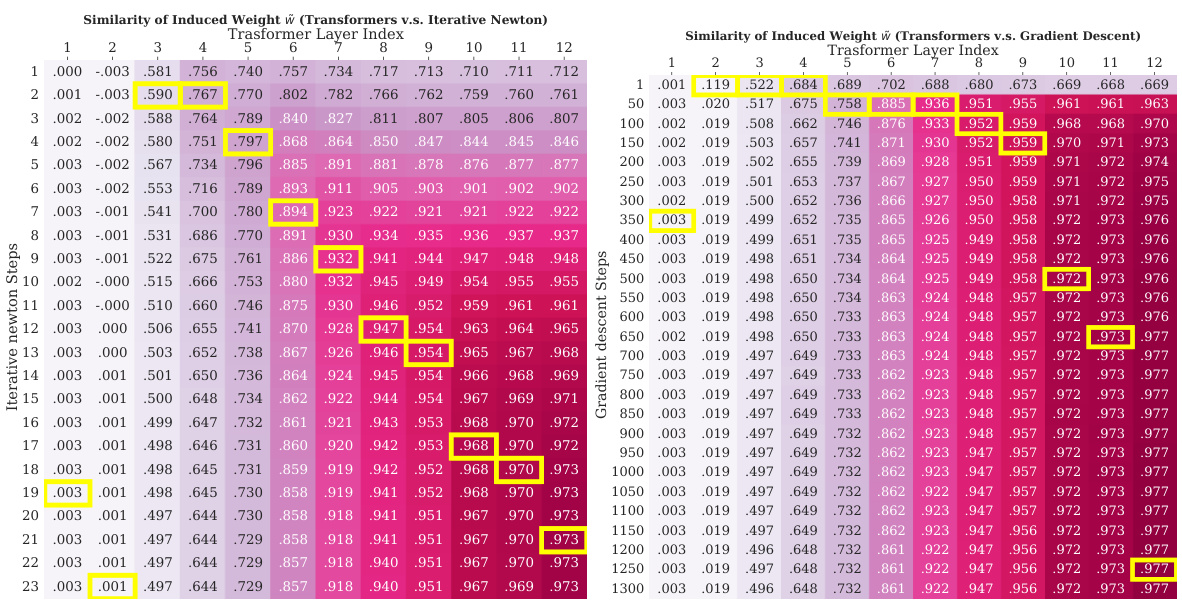

This figure shows the cosine similarity between the induced weight vectors of Transformers and three other algorithms (Iterative Newton’s Method, Gradient Descent, and Ordinary Least Squares) across different numbers of in-context examples. It demonstrates how the similarity of Transformers’ weights changes as it processes more data, illustrating its transition from resembling OLS to Iterative Newton’s Method in later layers, which is consistent with a second-order optimization approach. The dip around n=d (data dimension) for OLS similarity highlights a double descent phenomenon that is less prominent in Transformers and Iterative Newton.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three different algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that as the number of layers increases in a Transformer model (when the number of data points exceeds the number of features), its performance improves at a superlinear rate, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method which is also a second-order optimization method, but much faster than Gradient Descent (a first-order optimization method). The convergence rate of Gradient Descent is sublinear; as the number of steps increase, the improvement becomes gradually smaller. The Transformer’s convergence slows in later layers because the error is already very small, diminishing the incentive for the model to precisely implement the optimization algorithm.

The figure compares the convergence speed of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression tasks. It shows that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method exhibit similar superlinear convergence rates, significantly faster than Gradient Descent’s sublinear convergence. The plots illustrate how the error decreases as the number of layers (Transformers), steps (Iterative Newton), or steps (Gradient Descent) increases. The results suggest that Transformers learn an optimization strategy closer to second-order methods than to first-order methods.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that the error decreases as the number of layers (for Transformers), iterations (for Iterative Newton’s Method), and steps (for Gradient Descent) increases. Importantly, it demonstrates that Transformers exhibit a superlinear convergence rate similar to Iterative Newton’s Method for in-context linear regression problems where the number of examples (n) exceeds the dimensionality of the data (d), whereas Gradient Descent converges sublinearly. The plot suggests that Transformers internally approximate a second-order optimization method, unlike the first-order Gradient Descent.

This figure compares the convergence rate of three different algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows how the error decreases as the number of layers (for Transformers), iterations (for Iterative Newton), and steps (for Gradient Descent) increases. The results demonstrate that Transformers converge at a similar rate to Iterative Newton’s Method, which is significantly faster than Gradient Descent, especially when the number of data points exceeds the data dimension (n>d). The superlinear convergence of Transformers and Iterative Newton’s method is highlighted, while Gradient Descent’s convergence is shown to be sublinear. The later layers of the transformer show a slower convergence because the error is already small.

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression. It shows that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s method exhibit a superlinear convergence rate (significantly faster than linear), while Gradient Descent converges sublinearly. The Transformer’s convergence rate is similar to Iterative Newton’s, particularly in the middle layers. Later layers of the Transformer show slower convergence, likely because the error is already small and there is less incentive for precise algorithm implementation.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms (Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent) for in-context linear regression. It shows that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method exhibit similar superlinear convergence, significantly faster than the sublinear convergence of Gradient Descent. The plots demonstrate that performance improves progressively as the number of layers (Transformers), steps (Iterative Newton), or steps (Gradient Descent) increase.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, on the task of in-context linear regression. The x-axis represents the number of layers for Transformers and the number of steps for Iterative Newton and Gradient Descent. The y-axis shows the error rate. The figure shows that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method exhibit similar, superlinear convergence rates (meaning the error decreases faster than linearly), while Gradient Descent demonstrates a slower, sublinear convergence rate. The superlinear convergence of Transformers is particularly evident in the middle layers (3-8). Later layers show reduced convergence as the error becomes very small.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression. The x-axis represents the number of layers (Transformers), steps (Iterative Newton), or steps (Gradient Descent), while the y-axis shows the error. The figure demonstrates that Transformers and Iterative Newton’s Method exhibit a similar superlinear convergence rate, significantly faster than the sublinear convergence of Gradient Descent. This supports the paper’s claim that Transformers learn to approximate second-order optimization methods.

This figure compares the convergence rate of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that the error decreases as the number of layers (for Transformers), steps (for Iterative Newton’s Method), and steps (for Gradient Descent) increases. The key finding is that Transformers exhibit a superlinear convergence rate, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, which is significantly faster than the sublinear rate of Gradient Descent, especially when the number of data points exceeds the data dimension.

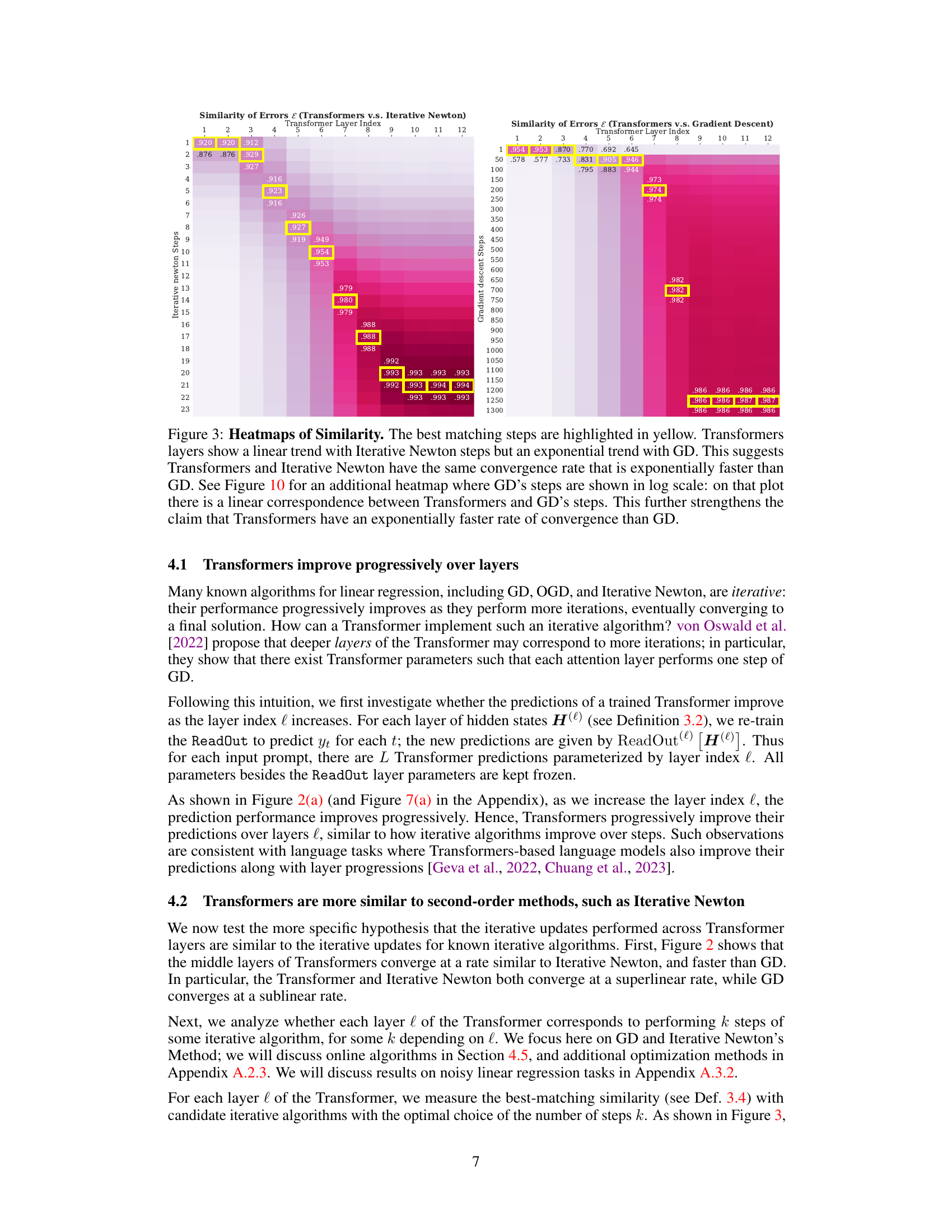

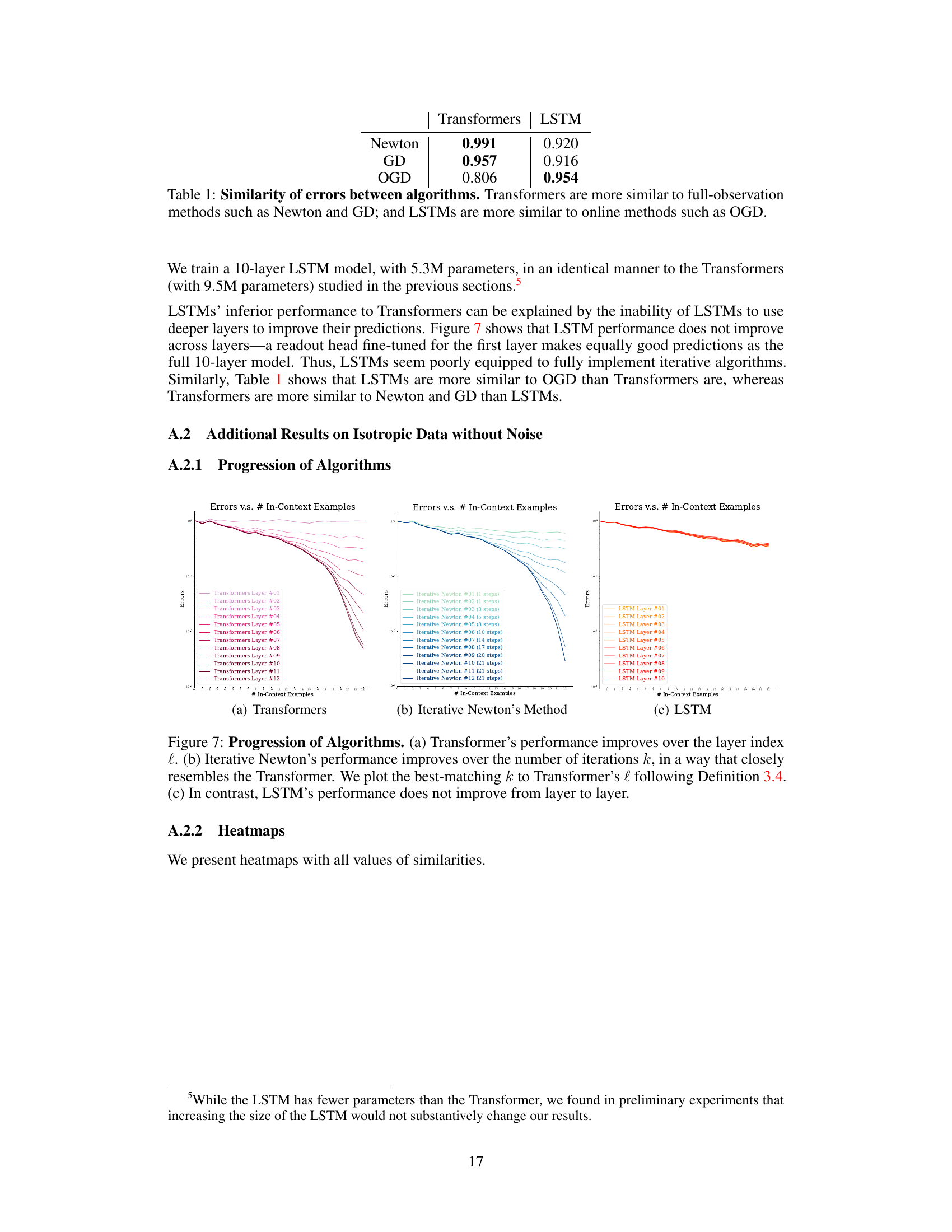

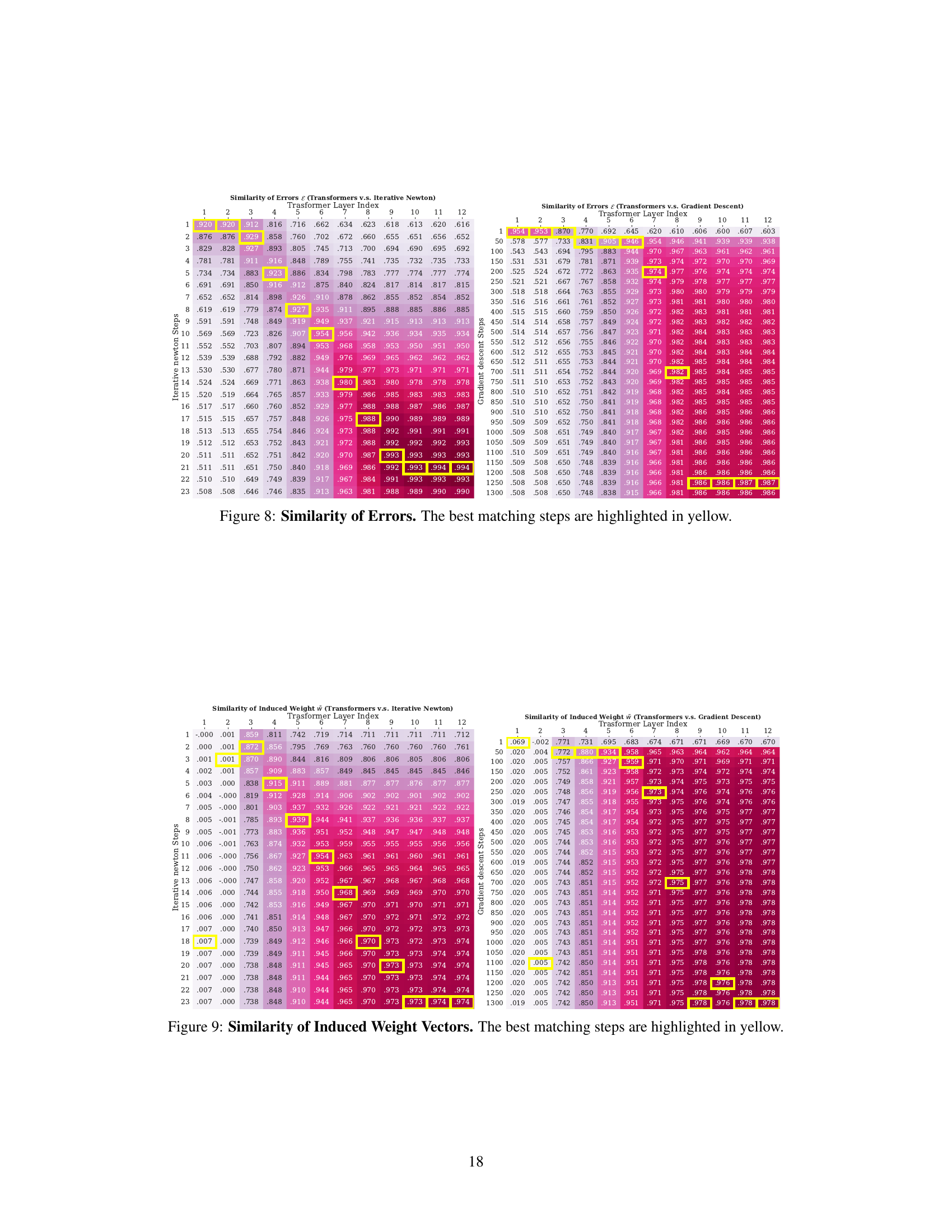

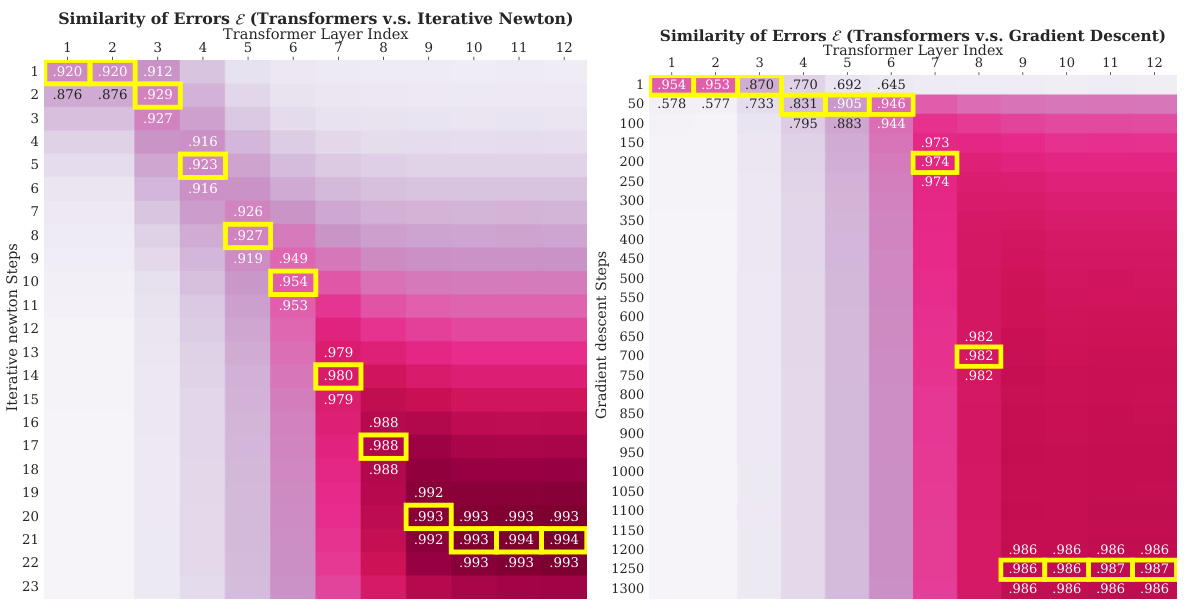

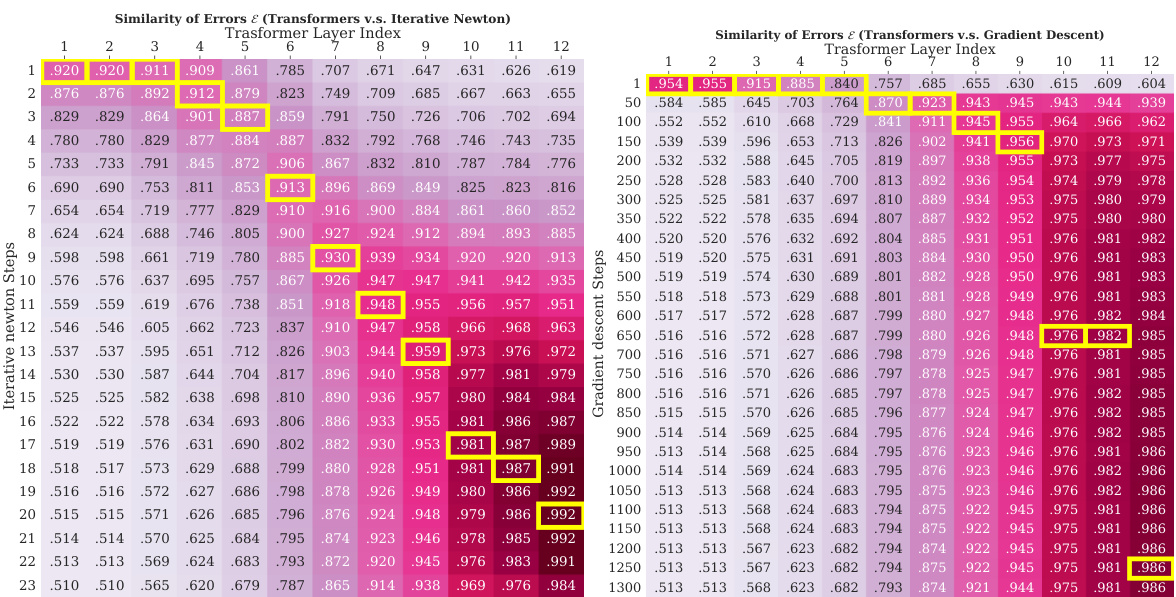

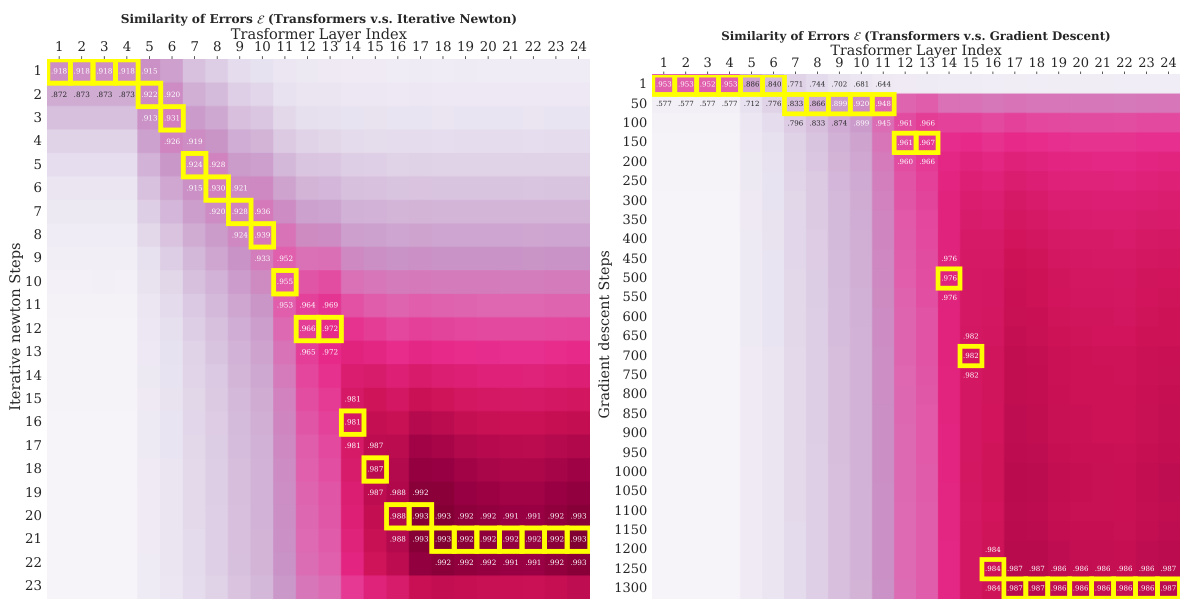

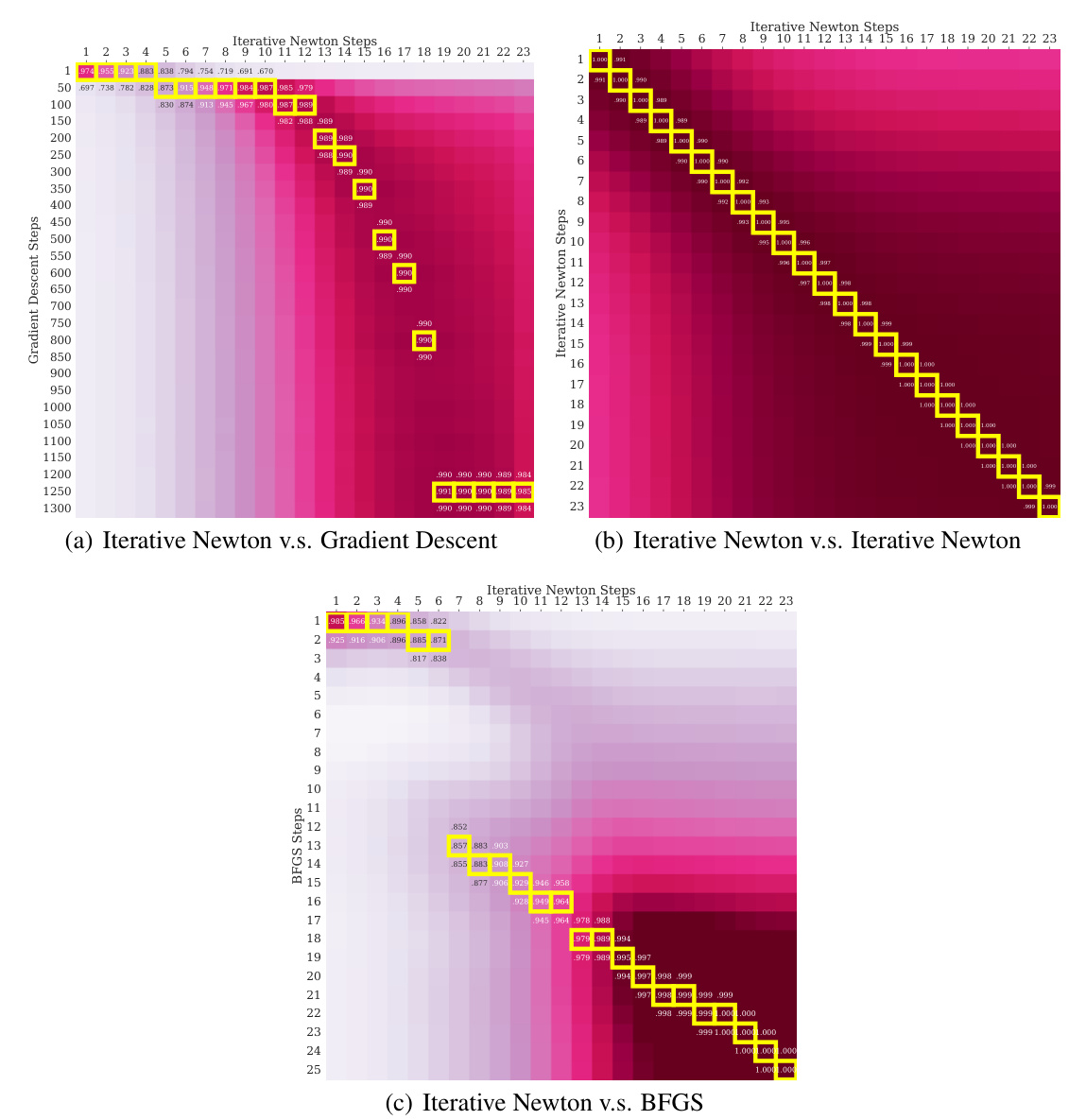

This figure presents heatmaps visualizing the similarity between Transformers and two optimization algorithms: Iterative Newton’s Method and Gradient Descent. The yellow highlights indicate the best-matching steps between the algorithms. The heatmaps show that Transformers’ performance improves linearly with the number of Iterative Newton steps and exponentially with the number of Gradient Descent steps, which indicates that Transformers learn a second-order optimization method similar to Iterative Newton’s Method and significantly faster than Gradient Descent.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that the Transformer’s error decreases superlinearly with the number of layers, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, but much faster than Gradient Descent. The plot suggests that Transformers may internally perform an optimization algorithm similar to a second-order method rather than gradient descent.

The figure compares the convergence rates of three algorithms: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s Method, and Gradient Descent, for in-context linear regression. It shows that Transformers’ performance improves superlinearly with the number of layers, similar to Iterative Newton’s Method, and significantly faster than Gradient Descent. The plots demonstrate how the predictions of successive Transformer layers closely approximate those of Iterative Newton’s Method after a corresponding number of iterations, supporting the claim that Transformers learn to approximate second-order optimization methods.

This figure compares the convergence rates of three different algorithms for linear regression: Transformers, Iterative Newton’s method, and Gradient Descent. It shows that as the number of layers increases in the Transformer model, the error decreases superlinearly (much faster than a linear rate), similar to Iterative Newton’s method. Gradient Descent, in contrast, shows a sublinear convergence rate. The results suggest that Transformers learn to approximate second-order optimization methods.

Full paper#