↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Drug discovery is hampered by the vast chemical space and slow processing speeds of 3D structure-based drug design (3D-SBDD) models. Scaffold hopping is a promising strategy to narrow this space, but existing 3D-SBDD generative models are too slow for practical use.

This research introduces TurboHopp, an accelerated 3D scaffold hopping model that uses consistency models to achieve up to 30x faster inference speed than existing methods, without sacrificing quality. It also uses reinforcement learning to further optimize the model output. TurboHopp addresses the speed bottleneck of 3D-SBDD models, significantly improving efficiency in drug discovery and enabling new optimization strategies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in drug discovery. It introduces TurboHopp, a significantly faster and higher-quality 3D scaffold hopping model, addressing a major bottleneck in the field. The integration of reinforcement learning for further optimization opens exciting new avenues for accelerating drug development and offers a powerful tool for exploring diverse molecular settings.

Visual Insights#

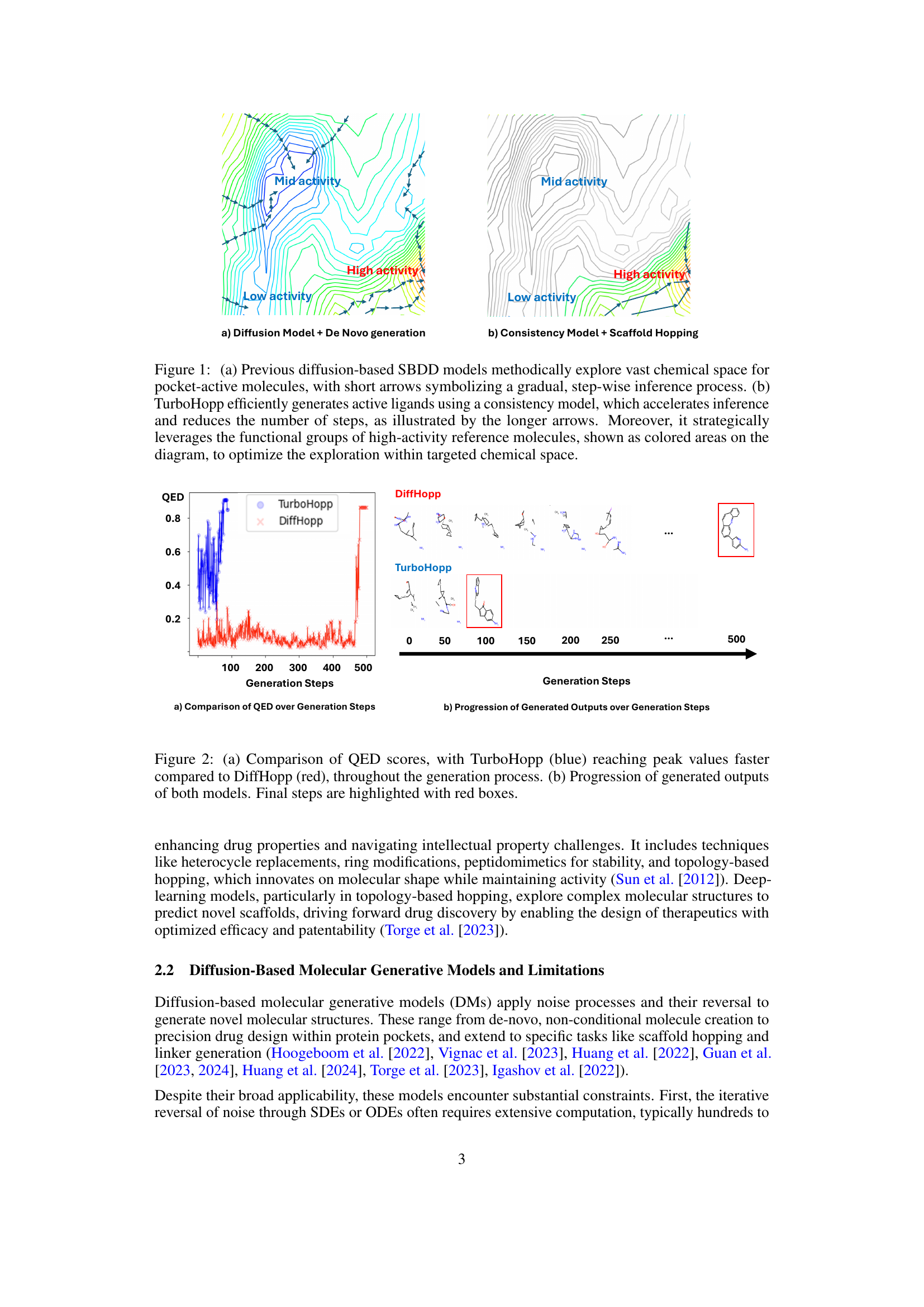

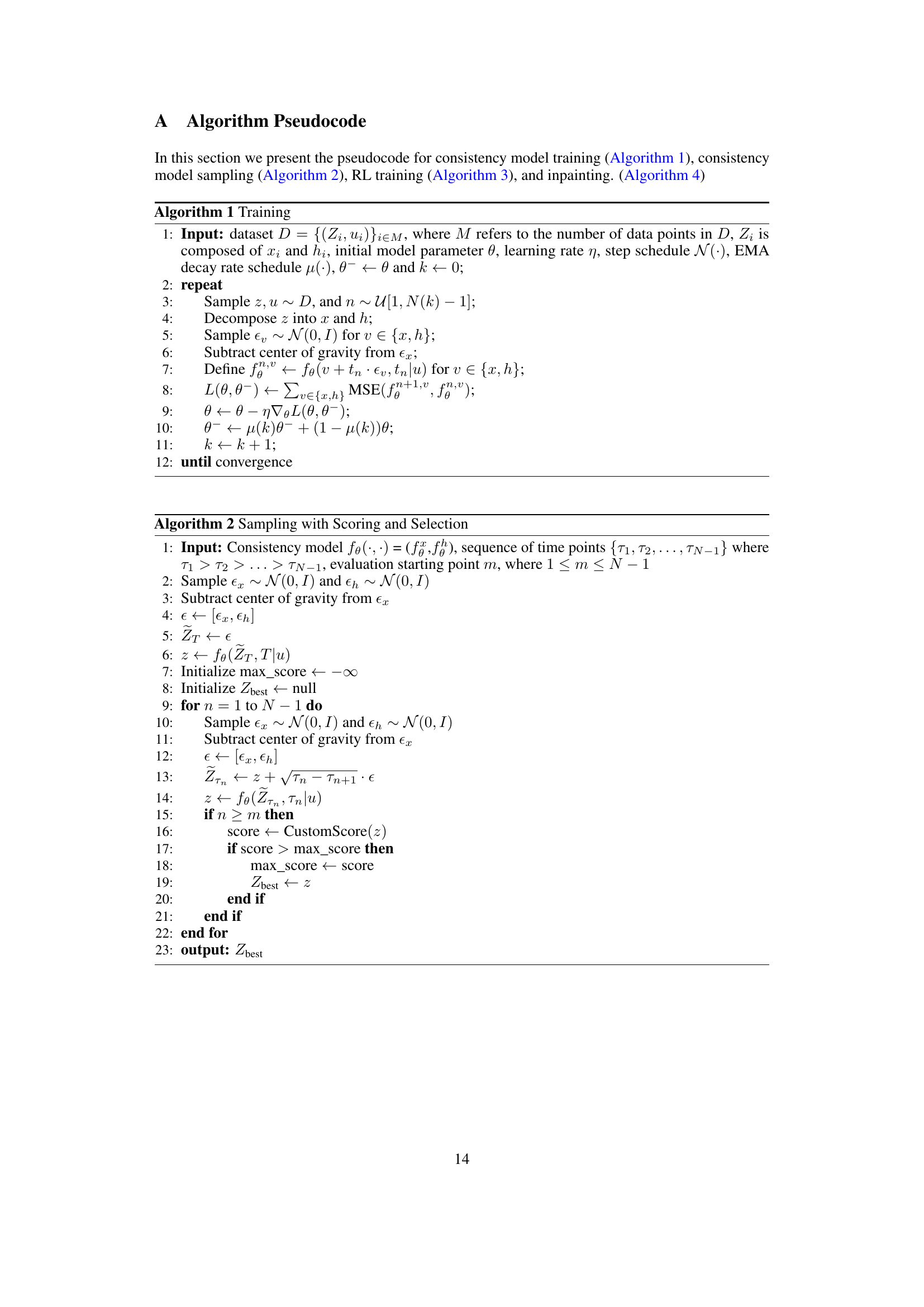

This figure compares two different approaches to molecule generation in the context of structure-based drug design. Panel (a) shows the traditional diffusion model approach, where the model iteratively refines a molecule through many small steps, represented by short arrows. This approach is thorough but slow. Panel (b) shows the TurboHopp method, which uses a consistency model to generate molecules more rapidly. The longer arrows indicate the fewer steps involved. Furthermore, TurboHopp leverages functional groups from known high-activity molecules (colored areas) to guide the generation process and focus the search on more promising regions of chemical space.

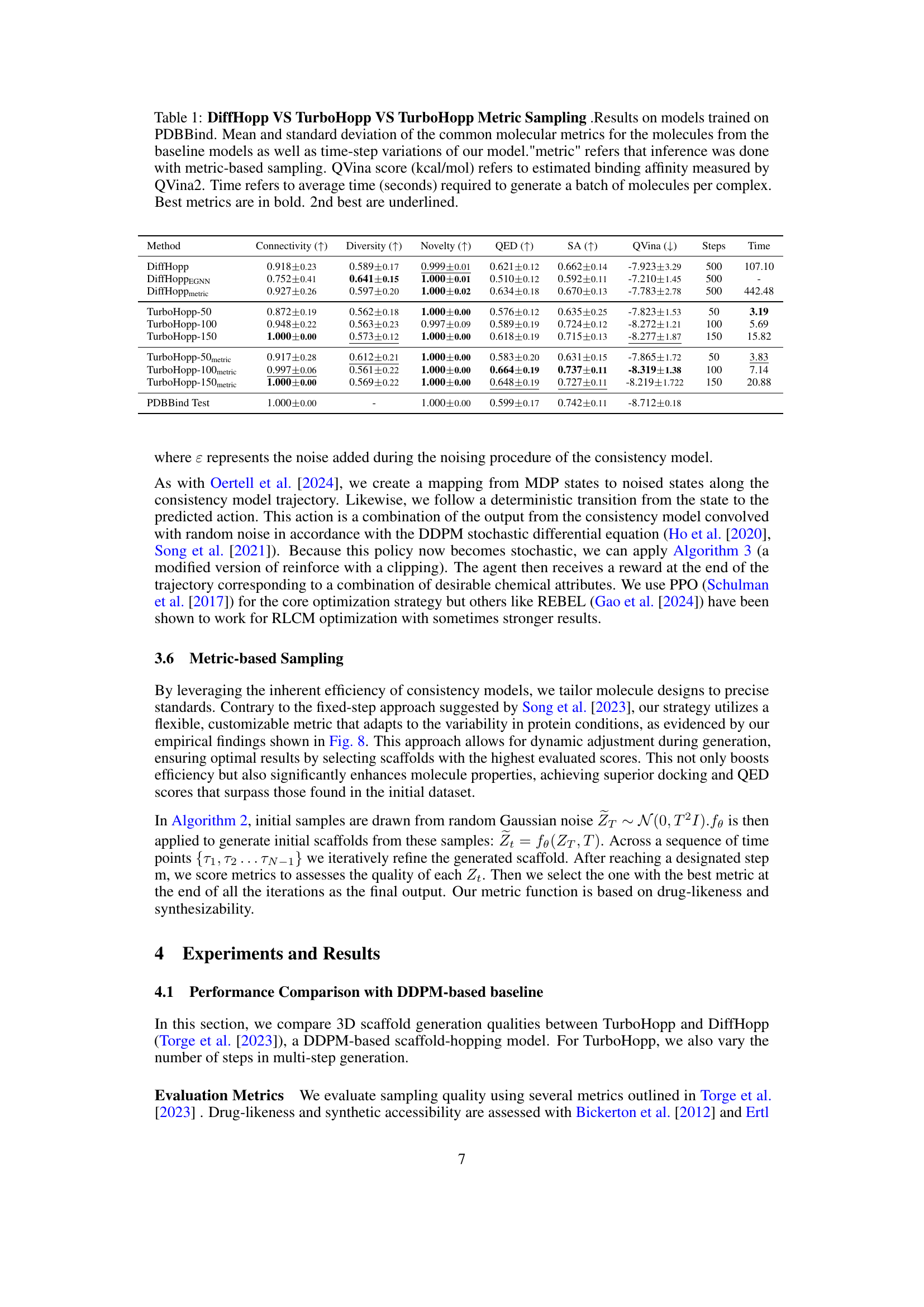

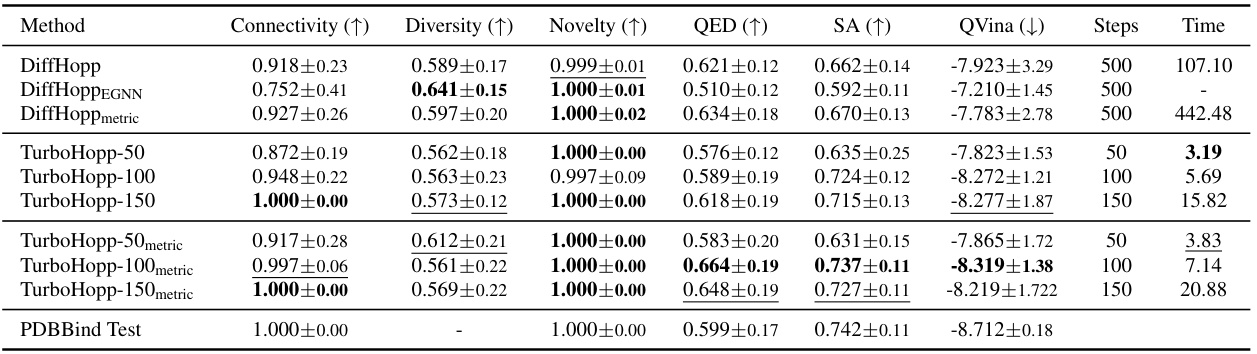

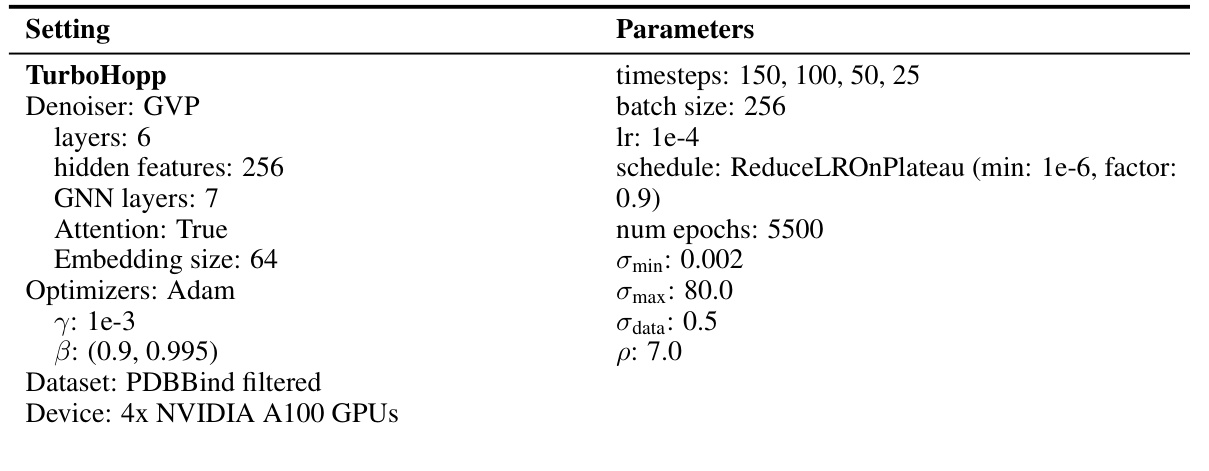

This table compares the performance of three different models: DiffHopp, TurboHopp with different numbers of steps (50, 100, 150), and TurboHopp with metric-based sampling. The comparison is based on several key molecular metrics including connectivity, diversity, novelty, QED (quantitative estimate of drug-likeness), synthetic accessibility (SA), and QVina binding affinity scores. The table also shows the number of steps in the generation process and the average generation time for each model. Bold numbers indicate the best result for a given metric, while underlined numbers represent the second-best.

In-depth insights#

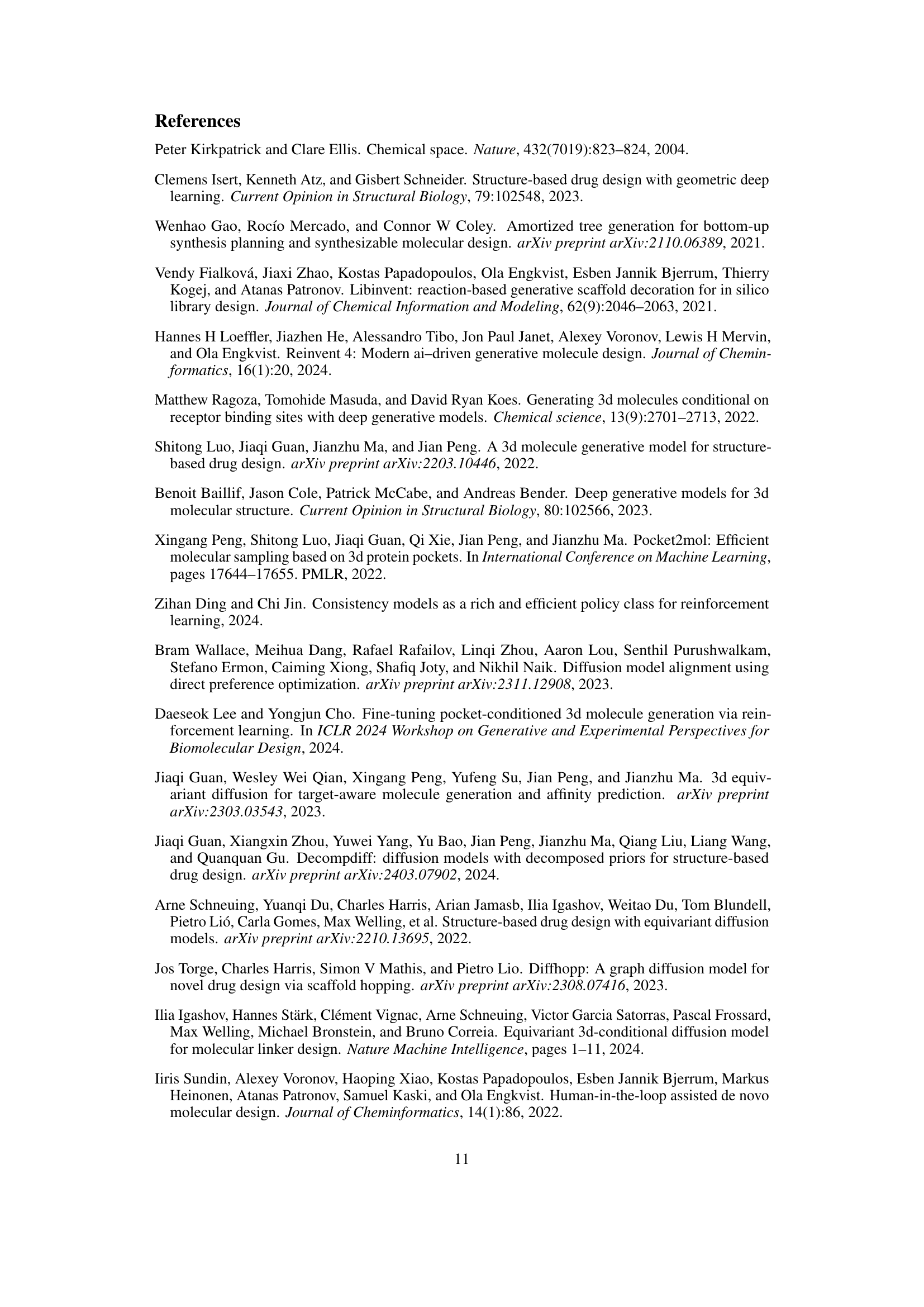

3D Scaffold Hopping#

3D scaffold hopping is a crucial technique in drug discovery that leverages the three-dimensional structure of molecules to identify novel compounds with similar biological activity but different scaffolds. This approach significantly accelerates the drug discovery process by strategically exploring the vast chemical space more efficiently compared to traditional methods. The core challenge lies in the computational cost associated with 3D molecule generation and evaluation, which can be quite intensive. The paper introduces a method that addresses this challenge using consistency models, offering a significant speed improvement over traditional diffusion models, while maintaining or improving the quality of generated molecules. Combining this speed enhancement with scaffold hopping strategies is key to creating a powerful approach for identifying novel drug candidates. The use of reinforcement learning further optimizes the model’s ability to generate molecules with desired properties, highlighting the potential of this integrated approach for impactful advancements in the field.

Consistency Models#

Consistency models, as discussed in the context of this research paper, offer a compelling advancement in generative modeling, especially within the computationally intensive field of 3D molecular design. Their key advantage lies in their significantly faster inference speeds compared to traditional diffusion models. This speed increase is achieved by directly transforming noise into data, thereby circumventing the iterative sampling process inherent in diffusion models. This efficiency is crucial for drug discovery applications, enabling faster exploration of chemical space, iterative model refinement, and real-time interactions with human experts. However, the paper highlights the limited exploration of these accelerated models within 3D drug design, underscoring the novelty and significance of their work. The incorporation of consistency models promises not only efficiency but also improved generation quality, as demonstrated by faster convergence to optimal QED scores and superior performance across multiple drug discovery scenarios. The synergy between consistency models and scaffold hopping further enhances the ability to strategically navigate the vast chemical space for more effective drug discovery.

RLCM Optimization#

The heading ‘RLCM Optimization’ suggests the application of Reinforcement Learning for Consistency Models (RLCM) to enhance the performance of a generative model. This implies a methodology where an RL agent learns to guide the consistency model’s generation process, optimizing for specific desired properties or metrics. The use of RLCM is particularly advantageous because consistency models offer significantly faster inference speeds compared to diffusion models. This speedup is crucial, especially in computationally expensive applications like drug discovery, allowing for more iterative refinement and exploration of the chemical space. The RL agent’s role is to define a reward function reflecting the desirability of generated molecules based on factors like drug-likeness, binding affinity, synthesizability, and fewer steric clashes. By maximizing this reward, the RLCM algorithm fine-tunes the consistency model towards producing molecules with improved properties beyond what could be achieved by direct model training alone. This approach represents a significant advance in leveraging the efficiency of consistency models while still achieving the targeted design objectives.

Performance Metrics#

The heading ‘Performance Metrics’ in a research paper would detail the methods used to evaluate the success of a model or technique. A thoughtful analysis would expect a discussion of metrics relevant to the research question, such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC for classification tasks, or RMSE, MAE, or R-squared for regression tasks. Beyond these standard metrics, a strong paper would highlight domain-specific metrics relevant to the application, and critically analyze their strengths and weaknesses. The choice of metrics should be justified by connecting them to the research goals. For example, a drug discovery paper might include metrics such as drug-likeness scores, synthesizability predictions, and binding affinity, reflecting the specific challenges in that field. A comprehensive discussion would also acknowledge the limitations of the chosen metrics, discussing the potential biases they may reveal, or other important factors that the chosen metrics might not capture. Comparison to existing benchmarks or state-of-the-art methods is crucial; this should be based on well-established and relevant metrics and clearly state the context of any differences. Finally, a thorough section on performance metrics would present results clearly and concisely, ideally using visuals such as tables and graphs, helping the reader understand the model’s performance and its implications.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize enhancing the model’s ability to handle diverse molecular scenarios and improve the efficiency of the sampling process. Exploring alternative reward functions for RLCM is crucial to address complex objectives such as synthesizability and binding affinity effectively. Incorporating bond diffusion and hydrogen atoms in the model could significantly improve the accuracy and realism of the generated molecules. Furthermore, investigating alternative loss functions and optimization strategies for consistency models, such as pseudo-Huber loss and noise scheduling, can potentially enhance model stability and efficiency. Finally, developing comprehensive methods for evaluating and benchmarking 3D generative models is essential to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of results and facilitate the advancement of structure-based drug discovery.

More visual insights#

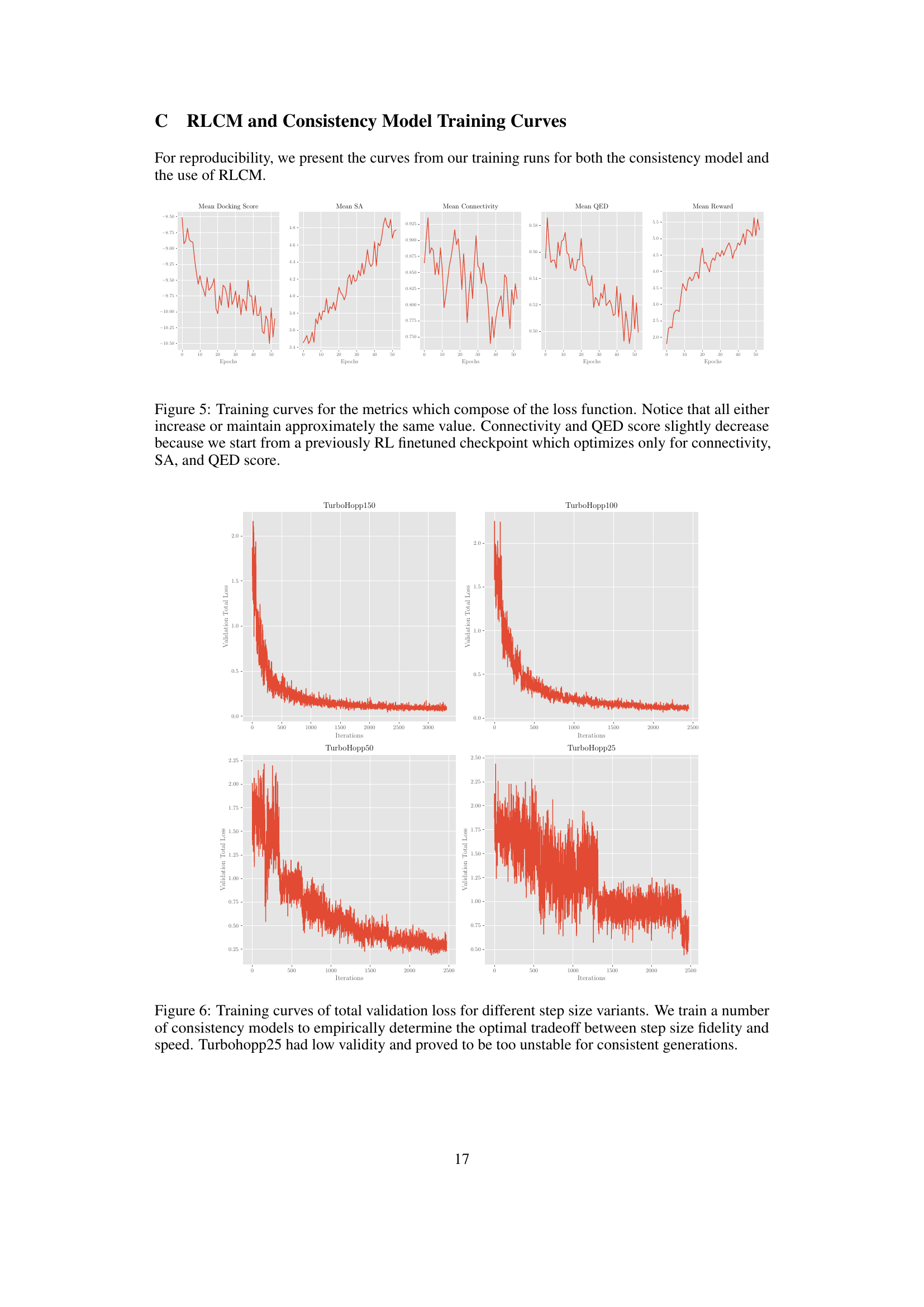

More on figures

This figure illustrates the difference between traditional diffusion-based SBDD models and the proposed TurboHopp model for 3D scaffold hopping. Panel (a) shows the traditional approach, where models gradually explore chemical space in a step-wise manner, represented by short arrows. Panel (b) demonstrates the efficiency of TurboHopp, using a consistency model to significantly speed up the generation of active ligands. The longer arrows in (b) highlight the increased speed, and the colored areas represent the strategic use of functional groups from high-activity reference molecules to focus the search within the targeted chemical space.

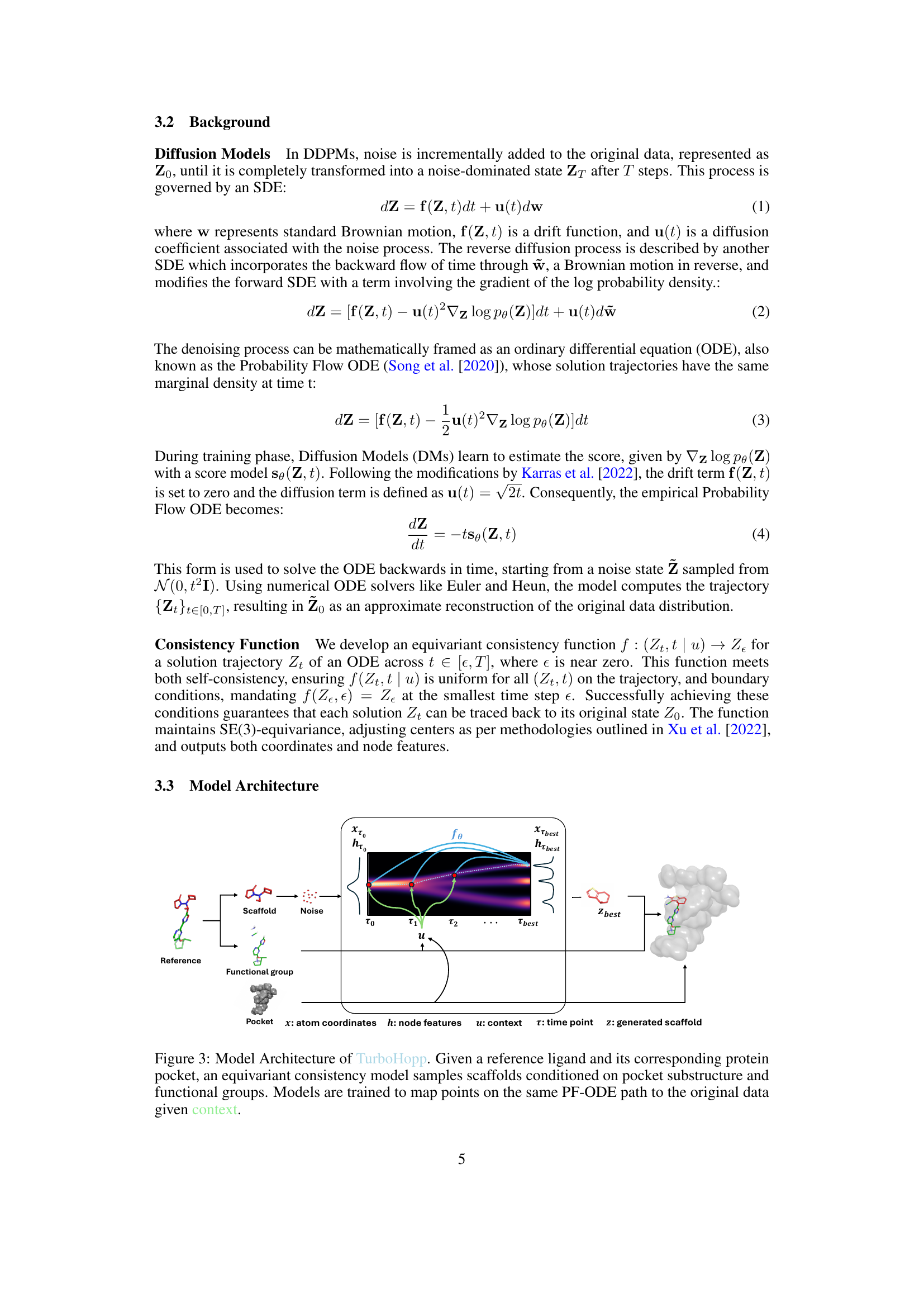

This figure compares the Quality-of-Estimation (QED) scores and the progression of generated molecular outputs for both TurboHopp and DiffHopp models over the generation steps. The left panel (a) shows that TurboHopp achieves higher QED scores faster than DiffHopp. The right panel (b) visually demonstrates the generated molecules at different stages of the process, highlighting the final outputs with red boxes, suggesting a better quality and faster convergence for TurboHopp.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the TurboHopp model. It takes as input a reference ligand, its functional groups, and the protein pocket’s structure. An equivariant consistency model then samples scaffolds based on this context information. The model is trained to map various points along a probability flow ordinary differential equation (PF-ODE) path back to the original data distribution, ensuring consistent and high-quality scaffold generation. The output is a generated scaffold, ready for further refinement or analysis.

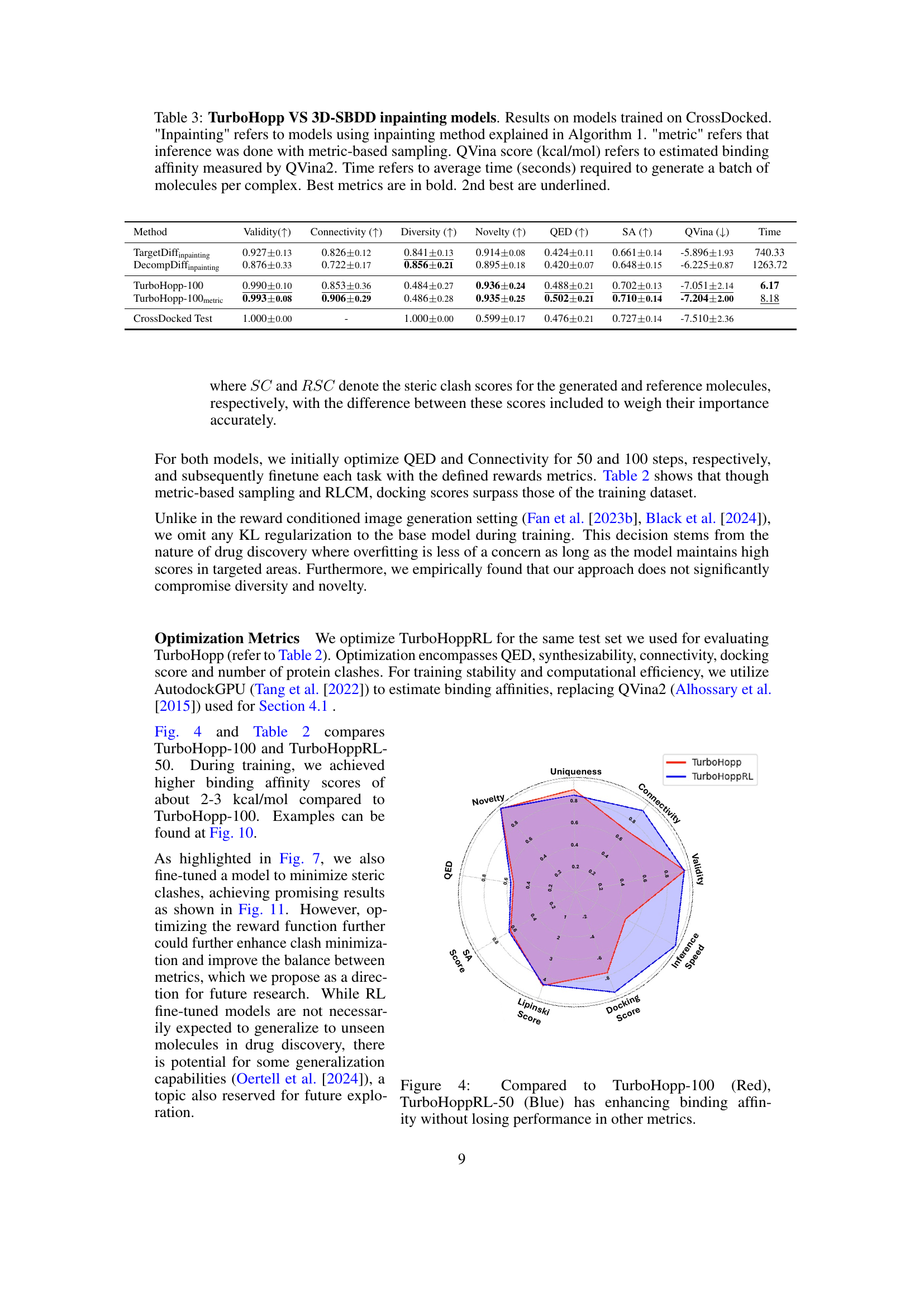

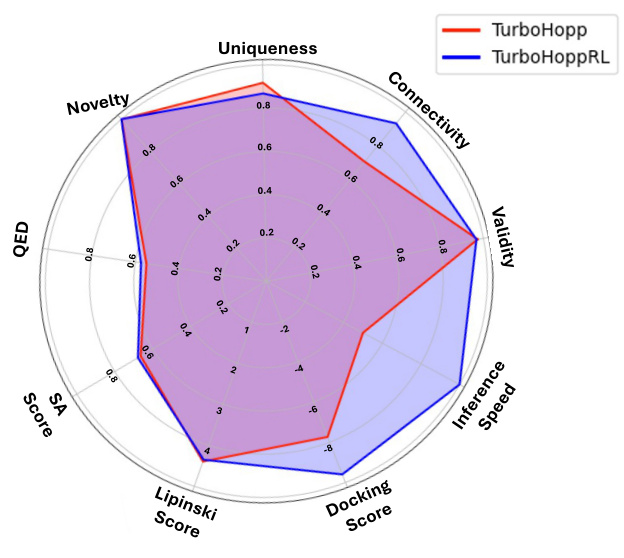

This radar chart compares the performance of TurboHopp and TurboHoppRL across several key metrics: Uniqueness, Novelty, QED, SA Score, Lipinski Score, Docking Score, Validity, Connectivity, and Inference Speed. Each axis represents one of these metrics, and the further a point is from the center, the higher the value. The chart shows that TurboHoppRL generally outperforms TurboHopp in most metrics, particularly in docking score and inference speed, while maintaining comparable performance in other areas.

This figure compares two approaches for molecule generation in the context of structure-based drug design. (a) shows the traditional diffusion model approach, which explores the vast chemical space gradually and requires many steps. (b) illustrates the TurboHopp method, utilizing a consistency model, which significantly speeds up the generation process and strategically uses the functional groups of known active molecules to focus the search within a specific chemical space.

This figure compares two approaches to scaffold hopping in drug discovery. (a) shows the traditional diffusion model approach, which explores the vast chemical space gradually and requires many steps. (b) shows the TurboHopp approach, which uses a consistency model to generate molecules more efficiently and strategically. TurboHopp leverages functional groups from high-activity molecules to guide the process and focus on more promising areas of chemical space.

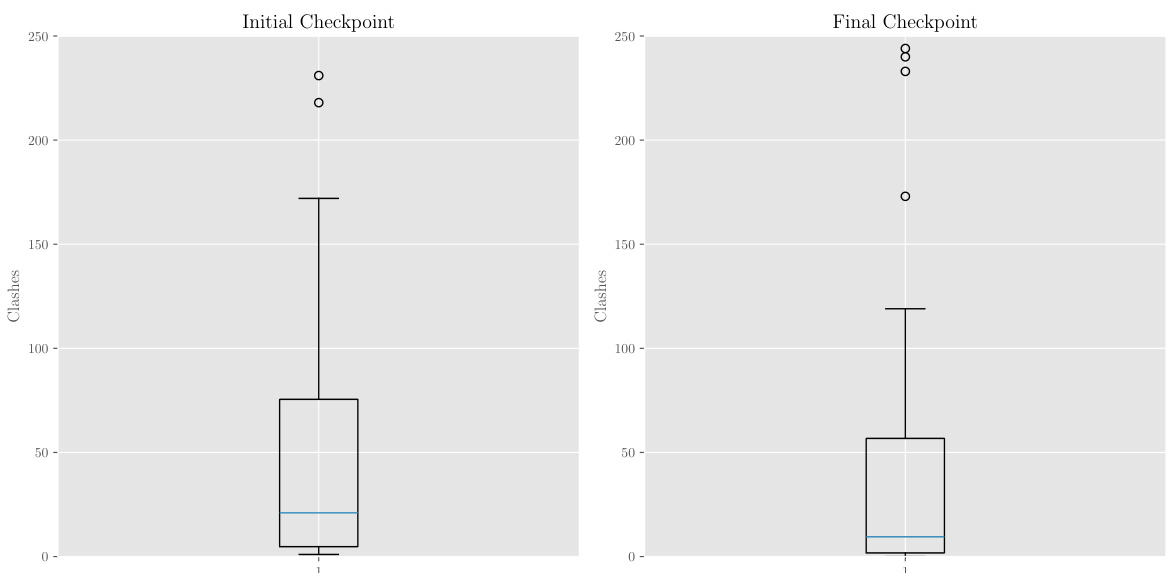

This figure shows box plots that compare the number of steric clashes between protein and ligand before and after fine-tuning the TurboHopp-100 model using a reinforcement learning reward function. The reward function was designed to improve binding affinity while considering other desirable properties like connectivity, QED, and synthesizability. The plot clearly shows that the fine-tuning process reduced the number of steric clashes, indicating that the model learned to generate molecules with improved fit and fewer unfavorable interactions with the protein.

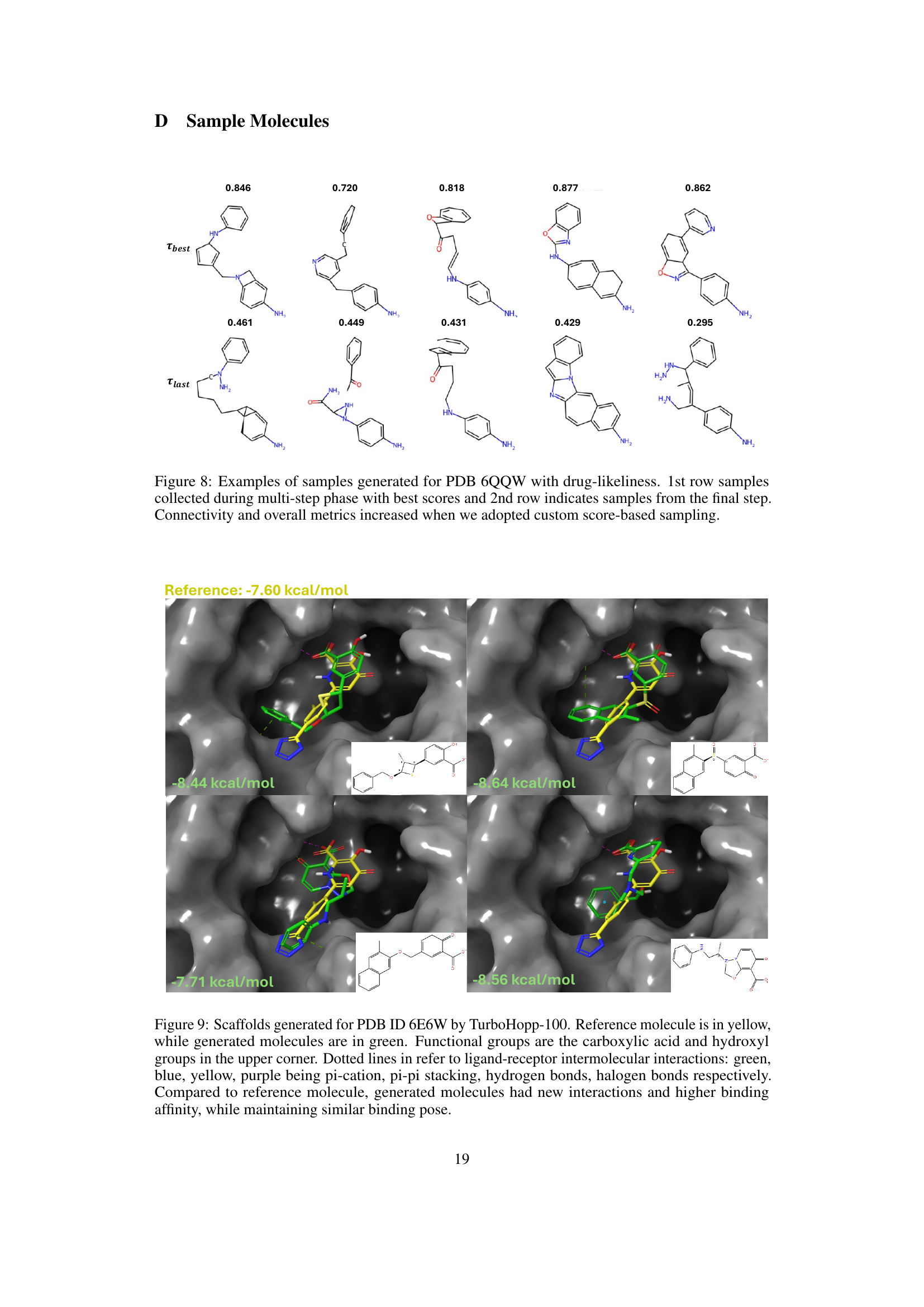

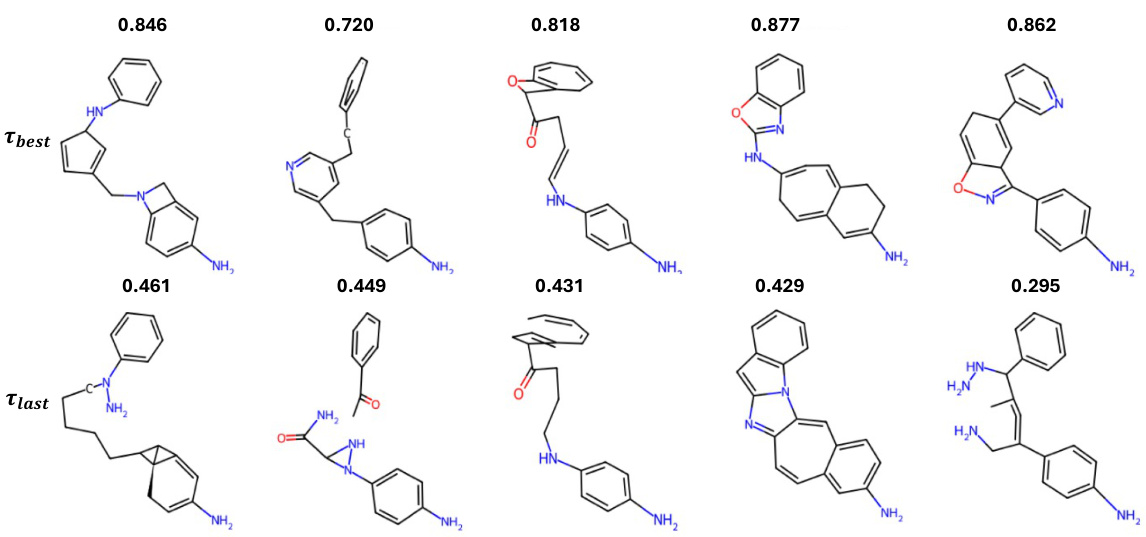

This figure showcases examples of molecular structures generated for PDB ID 6QQW using the TurboHopp model. The top row displays molecules sampled during the multi-step generation process, specifically those with the highest scores (based on a custom metric combining drug-likeness and other properties). The bottom row shows the final molecules generated in each respective run. The comparison highlights how the use of custom score-based sampling improves the overall quality of the generated molecules, leading to better connectivity and other desired metrics.

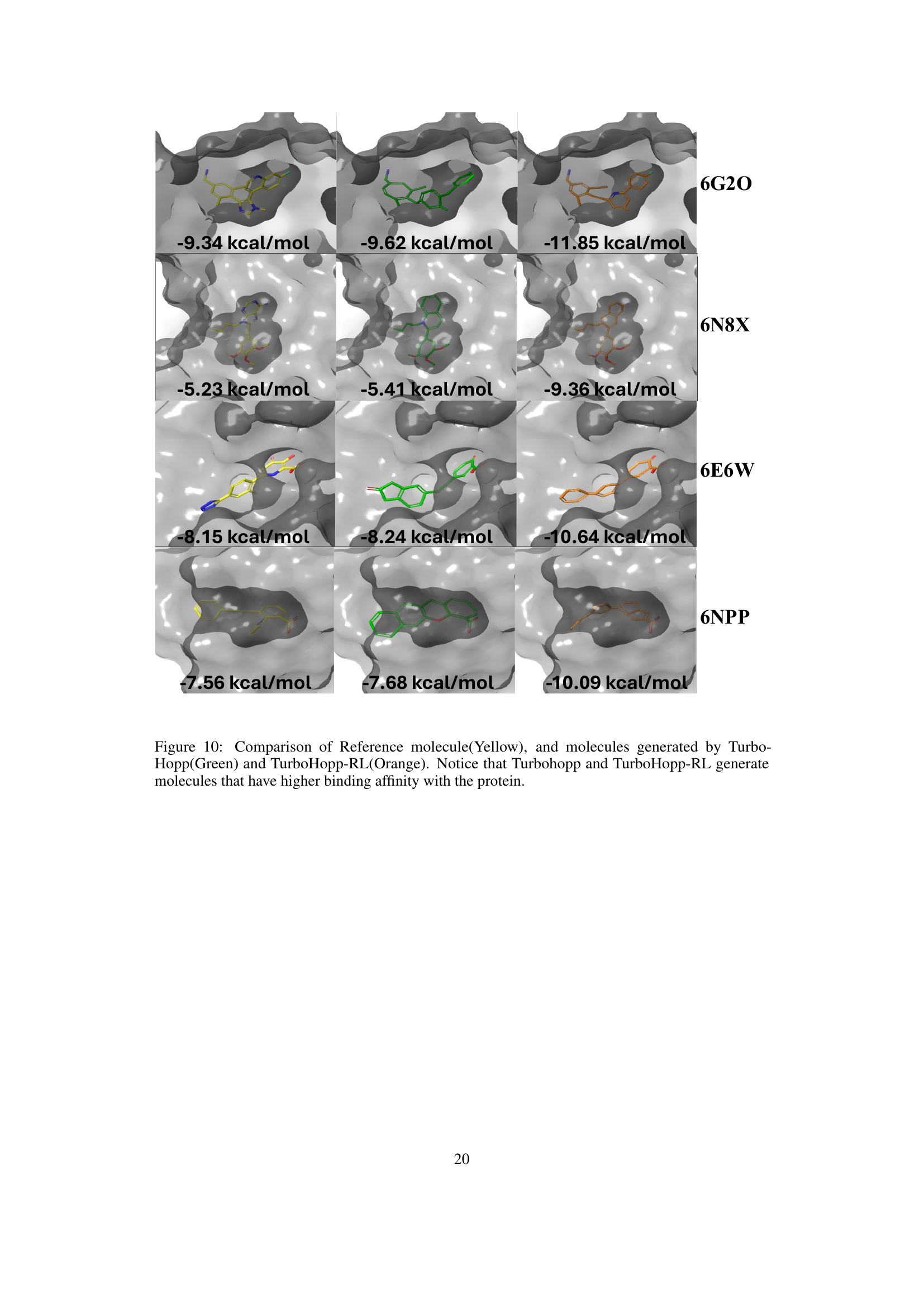

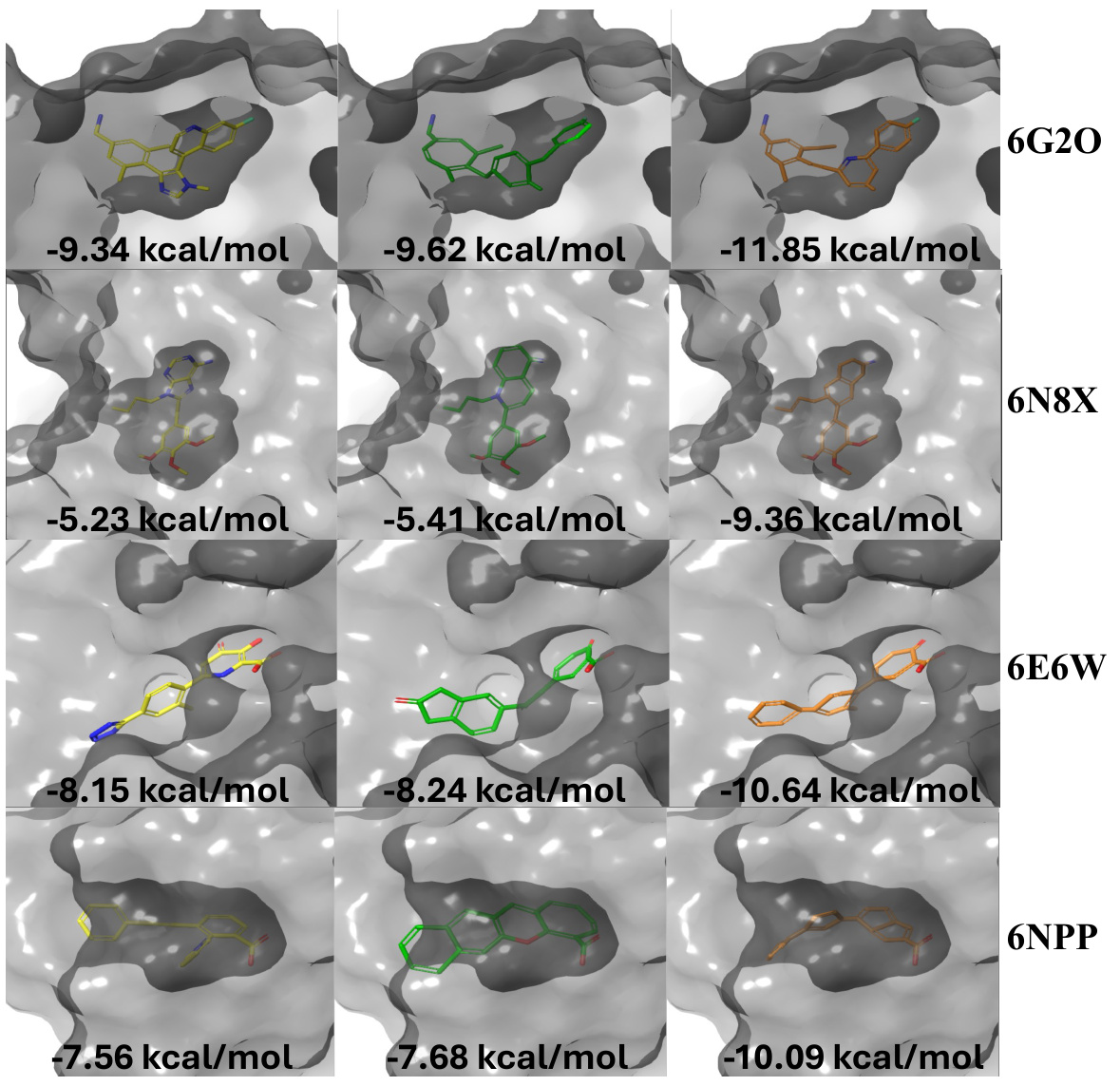

This figure compares the binding poses of reference molecules (yellow) to those generated by TurboHopp (green) and TurboHopp-RL (orange). It visually demonstrates that TurboHopp and its RL-optimized version, TurboHopp-RL, produce molecules with improved binding affinity compared to the reference molecules. The visualization highlights the spatial arrangements of the molecules within the protein binding pocket, illustrating the differences in binding interactions that lead to enhanced binding affinity.

This figure compares the binding poses of reference molecules (in yellow) with those generated by TurboHopp (in green) and TurboHopp-RL (in orange) for four different proteins (6G2O, 6N8X, 6E6W, and 6NPP). The binding affinity (in kcal/mol) is shown for each molecule, demonstrating that TurboHopp and especially TurboHopp-RL produce molecules with improved binding affinities compared to the references.

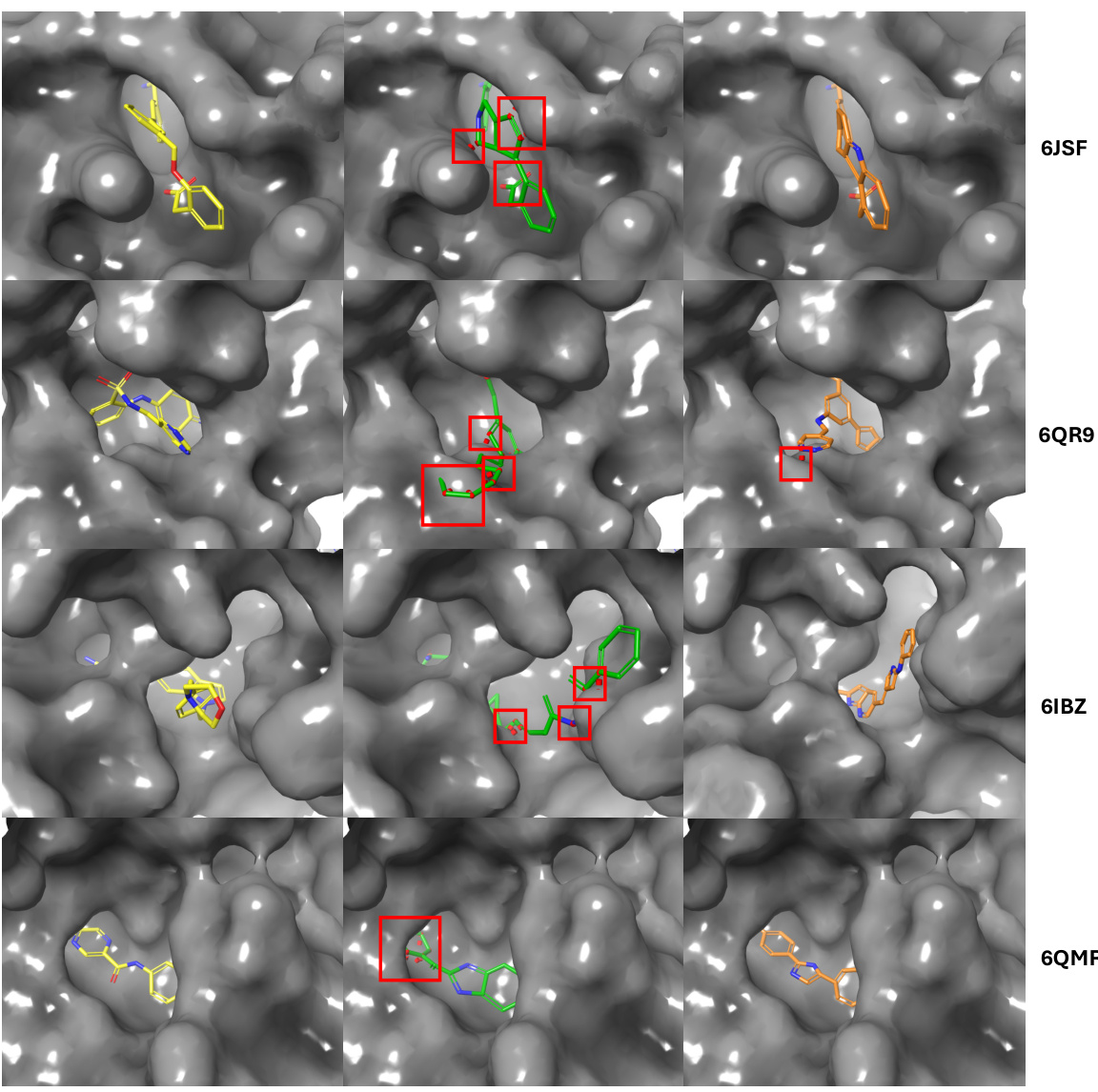

This figure compares the generated molecules by TurboHopp and TurboHopp-RL with the reference molecule. The red boxes highlight steric clashes between the generated molecules and the protein. It visually demonstrates that TurboHopp-RL, which incorporates reinforcement learning, produces molecules with fewer clashes compared to TurboHopp.

More on tables

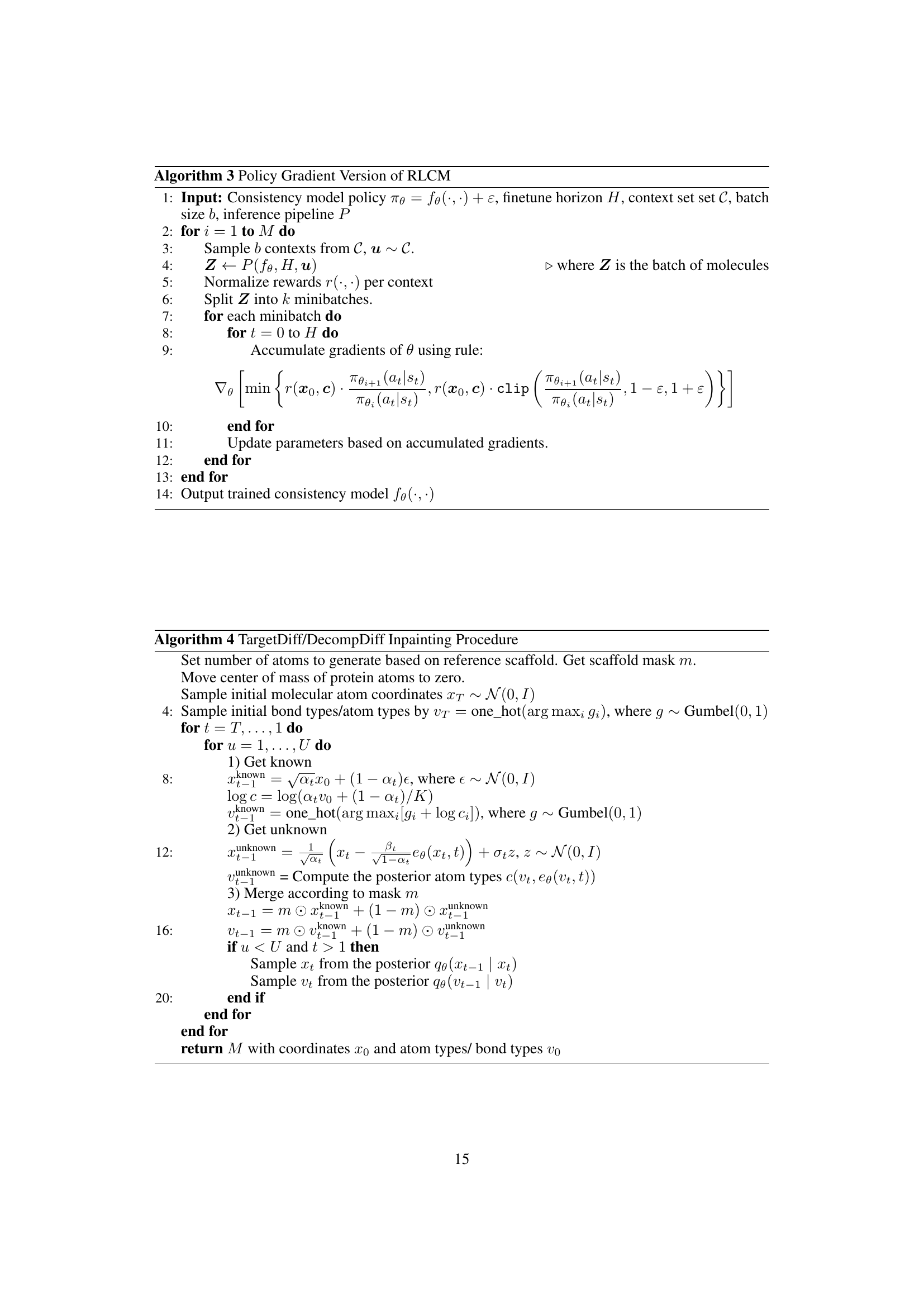

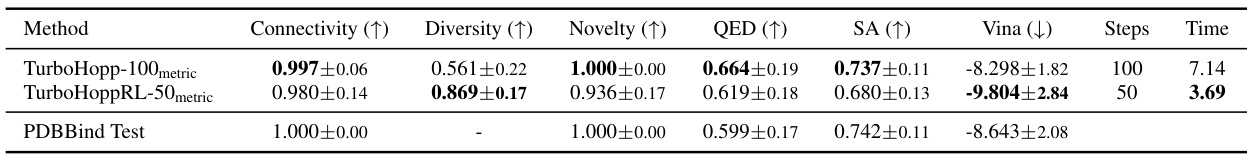

This table compares the performance of the TurboHopp-100 model with and without reinforcement learning (RLCM) optimization, using metric-based sampling. The RLCM-optimized model (TurboHoppRL-50metric) shows improved binding affinity (Vina score), while maintaining good drug-likeness (QED and SA scores) and connectivity. The faster inference speed of the consistency model enables the application of RLCM, which would be computationally expensive for diffusion models.

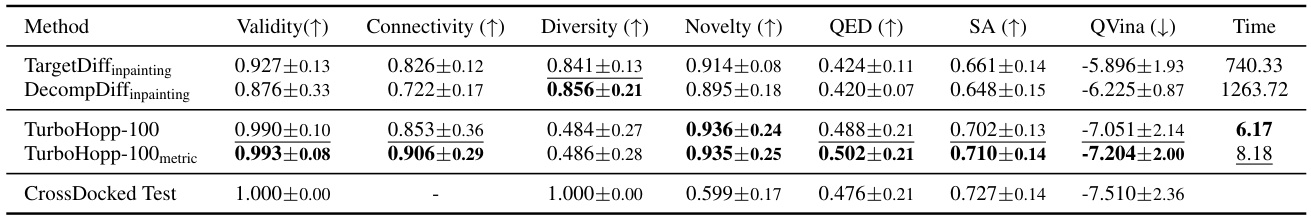

This table compares the performance of TurboHopp with two other diffusion-based 3D-SBDD inpainting models (TargetDiffInpainting and DecompDiffInpainting) on the CrossDocked dataset. The metrics evaluated include Validity, Connectivity, Diversity, Novelty, QED, SA, QVina score, and generation Time. The table highlights TurboHopp’s superior performance in most metrics, particularly its significantly faster generation time.

This table compares the performance of three different models: DiffHopp, TurboHopp with different numbers of generation steps (50, 100, 150), and TurboHopp with metric-based sampling. The models were trained on the PDBBind dataset. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of several key molecular metrics including connectivity, diversity, novelty, QED (quantitative estimate of drug-likeness), synthetic accessibility (SA), and QVina score (binding affinity). The number of generation steps and the average generation time are also shown. Bold values indicate the best performance for each metric, while underlined values indicate the second-best performance.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three different models: DiffHopp, TurboHopp with various numbers of generation steps, and TurboHopp using metric-based sampling. The performance is evaluated using several metrics: Connectivity, Diversity, Novelty, QED, SA, QVina score, and generation time. The table highlights that TurboHopp, especially with metric-based sampling, significantly outperforms DiffHopp in terms of speed and various molecular properties.

This table compares the performance of DiffHopp, TurboHopp with different numbers of steps (50, 100, 150), and TurboHopp using metric-based sampling. The metrics evaluated include connectivity, diversity, novelty, QED, synthetic accessibility (SA), QVina score (binding affinity), number of steps in the generation process, and inference time. The results highlight TurboHopp’s superior efficiency and comparable or better quality compared to DiffHopp.

This table compares the performance of three different models: DiffHopp, TurboHopp with different numbers of generation steps (50, 100, 150), and TurboHopp using metric-based sampling. It shows the mean and standard deviation for several key molecular metrics (Connectivity, Diversity, Novelty, QED, SA, QVina score) and the average inference time. The results highlight TurboHopp’s superior speed and comparable or improved quality compared to DiffHopp.

This table compares the performance of three different models: DiffHopp, TurboHopp with different numbers of generation steps (50, 100, 150), and TurboHopp using metric-based sampling. The models are evaluated using several metrics: connectivity, diversity, novelty, QED, synthetic accessibility (SA), QVina score (binding affinity), number of generation steps, and the average inference time. The results highlight that TurboHopp, particularly with metric-based sampling, achieves faster generation speeds and improved scores in various metrics compared to DiffHopp.

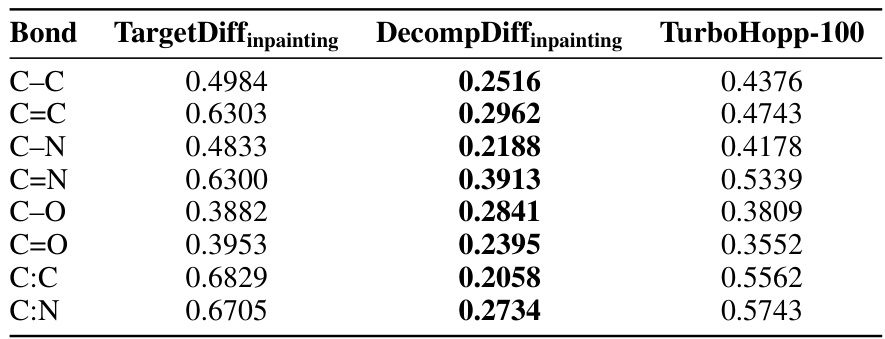

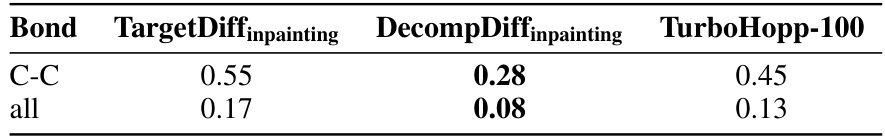

This table presents the Jensen-Shannon divergence values, which quantify the difference in the distributions of top three torsion angles between molecules generated by different models (TargetDiffInpainting, DecompDiffInpainting, and TurboHopp) and the reference molecules from the CrossDocked dataset. Lower divergence values indicate higher similarity between the generated and reference molecule distributions. The torsion angles are characterized by four atom types (e.g., CCNC).

This table compares the performance of TurboHopp with two other diffusion-based 3D-SBDD inpainting models (TargetDiff and DecompDiff) on the CrossDocked dataset. The comparison includes various metrics such as connectivity, diversity, novelty, QED, synthetic accessibility (SA), QVina score (binding affinity), and generation time. The table highlights TurboHopp’s superior performance in many metrics, particularly its speed, while acknowledging that other models might excel in specific areas like diversity.

Full paper#