↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The secretary problem, a fundamental online decision-making challenge, has a well-known optimal competitive ratio of 1/e. This paper challenges this established limit by introducing a novel variation: the secretary problem with a predicted additive gap. This variant assumes the algorithm receives advance knowledge of the difference between the highest and k-th highest weight. This seemingly weak piece of information is shown to be sufficient to surpass the 1/e barrier.

The core contribution of the paper lies in demonstrating the significant improvement achievable using only this limited predictive information. It presents a deterministic online algorithm that consistently outperforms the classical 1/e bound. Furthermore, the paper extends its analysis to scenarios with inaccurate gap predictions, showcasing algorithm robustness and introducing consistency-robustness trade-offs. This is achieved through a cleverly designed algorithm that adapts its threshold based on the provided gap information and an adaptive waiting period.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper significantly advances the field of online decision-making by demonstrating that even weak predictive information can substantially improve algorithm performance. It introduces a novel problem variant and provides robust, theoretically-grounded algorithms that beat long-standing performance bounds. This opens avenues for exploring the value of weak predictions in other online problems and refining the theoretical understanding of prediction’s impact.

Visual Insights#

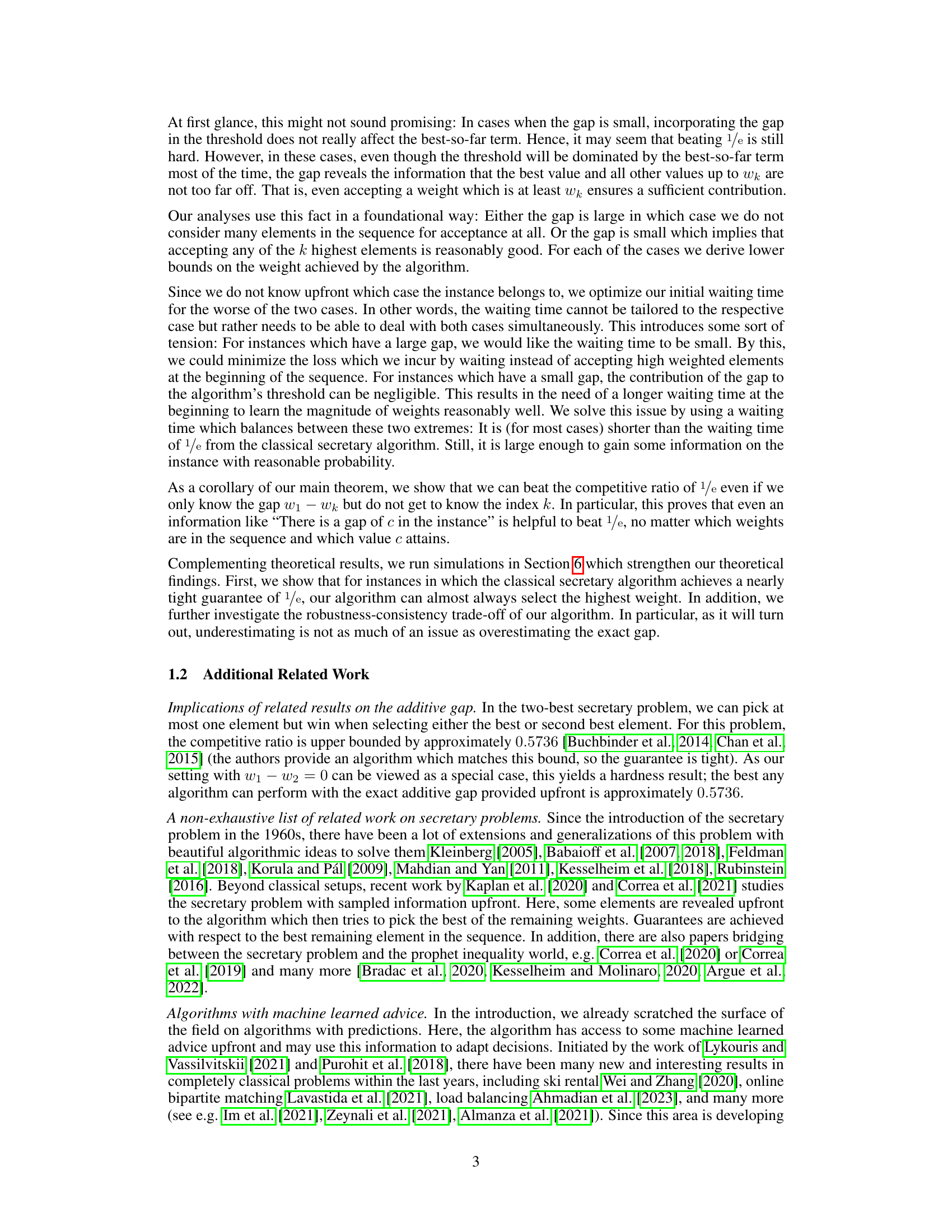

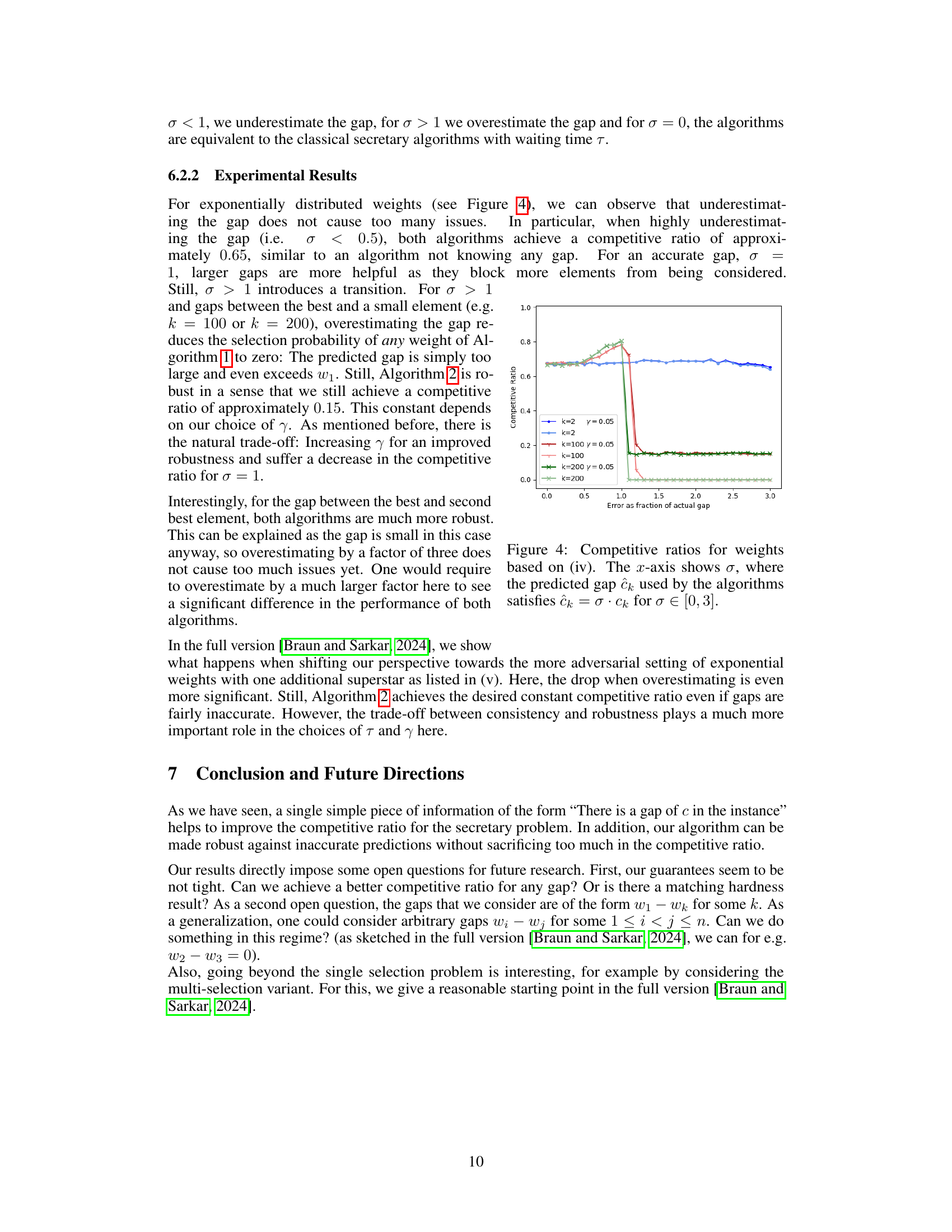

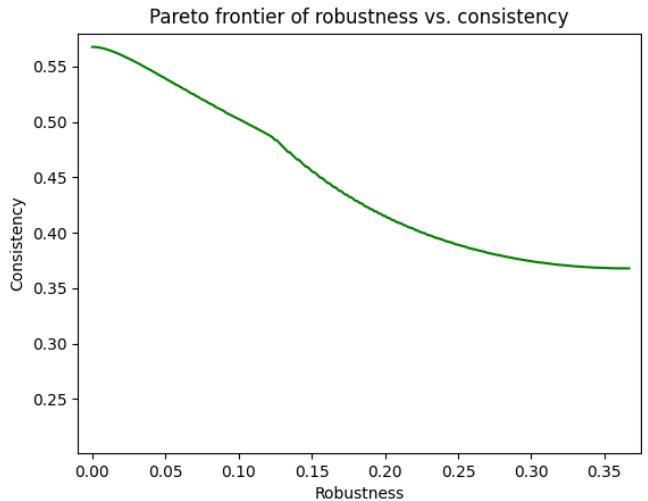

This figure shows the Pareto frontier of robustness versus consistency for Algorithm 2, which is a modified version of the secretary algorithm that incorporates a predicted additive gap. The x-axis represents the robustness (the algorithm’s competitive ratio when the predicted gap is inaccurate), and the y-axis represents the consistency (the algorithm’s competitive ratio when the predicted gap is accurate). The curve shows the trade-off between robustness and consistency: as robustness increases, consistency decreases. The figure helps to understand the optimal balance between robustness and consistency that can be achieved by tuning parameters τ and γ.

This figure shows a Pareto frontier of robustness and consistency tradeoffs for Algorithm 2. For a given level of robustness (tolerance for error in the predicted gap), the plot indicates the maximum achievable consistency (performance with an accurate prediction). This illustrates the algorithm’s ability to balance robustness and accuracy.

In-depth insights#

Additive Gap Impact#

The concept of ‘Additive Gap Impact’ in the context of a secretary problem centers on how the difference between the highest and k-th highest values affects algorithmic performance. A smaller additive gap implies that many values are clustered near the top, making the problem harder because identifying the absolute best becomes more challenging. Conversely, a larger gap suggests that the top value is significantly better than the rest, simplifying the search. The analysis likely explores how algorithms leveraging this gap information (either exact or estimated) can outperform traditional secretary problem algorithms, which operate without such knowledge. The research probably investigates whether the knowledge of an additive gap provides a robustness-consistency trade-off, such that when the additive gap is precisely known, the performance is very high, but even if there’s an error in the prediction, the performance remains competitive. Understanding this trade-off is crucial for practical applications where exact prediction of the gap might be unrealistic. The findings will reveal the minimum information content needed to surpass the classical 1/e barrier in competitive ratios, demonstrating that even weak, indirect information can provide a considerable advantage in the online decision-making process.

Algorithmic Robustness#

Algorithmic robustness examines how well an algorithm performs under various perturbations or unexpected inputs. A robust algorithm gracefully handles noisy data, incomplete information, or adversarial attacks, maintaining acceptable performance levels. The paper likely explores different robustness metrics, analyzing the algorithm’s resilience to variations in input data, parameters, or even underlying assumptions. Important considerations might include sensitivity analysis, error bounds, and worst-case performance guarantees. The analysis likely aims to quantify the algorithm’s robustness, perhaps by measuring how much perturbation it can tolerate before failure or degradation. This could be compared to other algorithms or baselines, showcasing potential advantages in scenarios with noisy or unpredictable data. Ultimately, robust algorithms are crucial for real-world applications where perfect conditions are rarely met.

Prediction Error Bounds#

The concept of ‘Prediction Error Bounds’ in a research paper would typically involve exploring the accuracy and reliability of predictive models. A key aspect would be defining a metric for measuring prediction error, such as mean squared error or mean absolute error. The analysis might involve deriving theoretical bounds on the expected error, perhaps based on assumptions about the data distribution or model complexity. The paper could investigate how factors like sample size and model parameters influence these bounds. Furthermore, empirical evaluations through simulations or real-world datasets would be essential to demonstrate the tightness of the theoretical bounds and assess the model’s performance under various conditions. A significant contribution would involve establishing conditions under which prediction errors remain within acceptable limits, ensuring the model’s practical applicability and robustness. Finally, the discussion should address the limitations of the error bounds, acknowledging any simplifying assumptions or challenges in achieving tight error estimates in real-world settings.

Simulation Experiments#

In a research paper’s ‘Simulation Experiments’ section, the authors would typically detail their computational experiments. This involves describing the simulated environment, including the parameters and algorithms used. Crucially, the methodology should be clearly explained, allowing others to reproduce the results. The choice of parameters is also vital, and the rationale behind it should be justified. Transparency is paramount; any assumptions or limitations affecting the experiments must be clearly stated. Results should be presented effectively, often using graphs or tables, accompanied by appropriate statistical analysis and error bars to assess the significance of findings. The section should also discuss the computational resources required and any challenges encountered during the simulations. Finally, the authors should analyze the implications of the experimental findings and connect them to the theoretical aspects of the paper. A well-executed ‘Simulation Experiments’ section demonstrates the robustness and validity of the research, increasing its reliability and impact.

Future Research#

The paper’s discussion on future research directions highlights several promising avenues. Tightening the competitive ratio bounds is a key area, as the current 0.4 bound may not be optimal. Exploring generalized gap structures, beyond the specific additive gap used, could significantly broaden the applicability and impact of the findings. This includes investigating arbitrary gaps between any two weights (wᵢ - wⱼ), not just between the highest and k-th highest. Another important area is extending the single-selection secretary problem to the multi-selection variant, which would increase the real-world applicability. Finally, a deeper investigation into the robustness-consistency trade-off for inaccurate gap predictions is crucial, exploring various prediction error models and developing more sophisticated algorithms. Addressing these areas would solidify and significantly expand upon the current results.

More visual insights#

More on figures

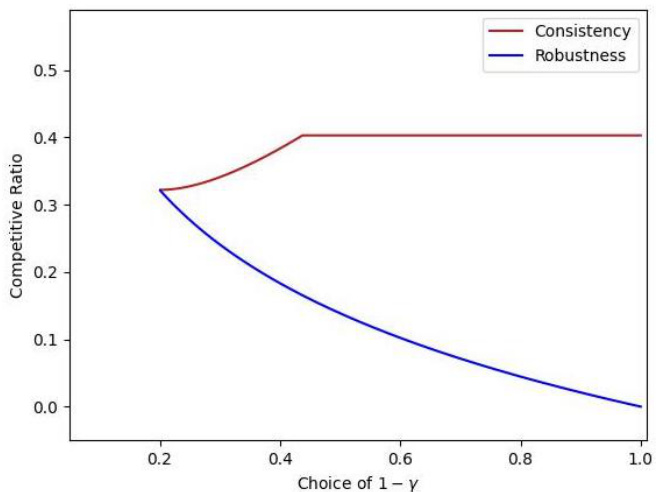

This figure shows the Pareto frontier of robustness versus consistency for Algorithm 2, which is a modified version of the secretary algorithm designed to be robust to errors in the predicted additive gap. The x-axis represents the choice of 1−γ, which is a parameter controlling the robustness of the algorithm (higher values mean more robustness). The y-axis represents the consistency, which is a measure of how well the algorithm performs when the predicted gap is accurate. The curve indicates the tradeoff between robustness and consistency; as robustness increases, consistency decreases, and vice versa. This plot helps to select optimal parameter values based on the desired balance between these two properties.

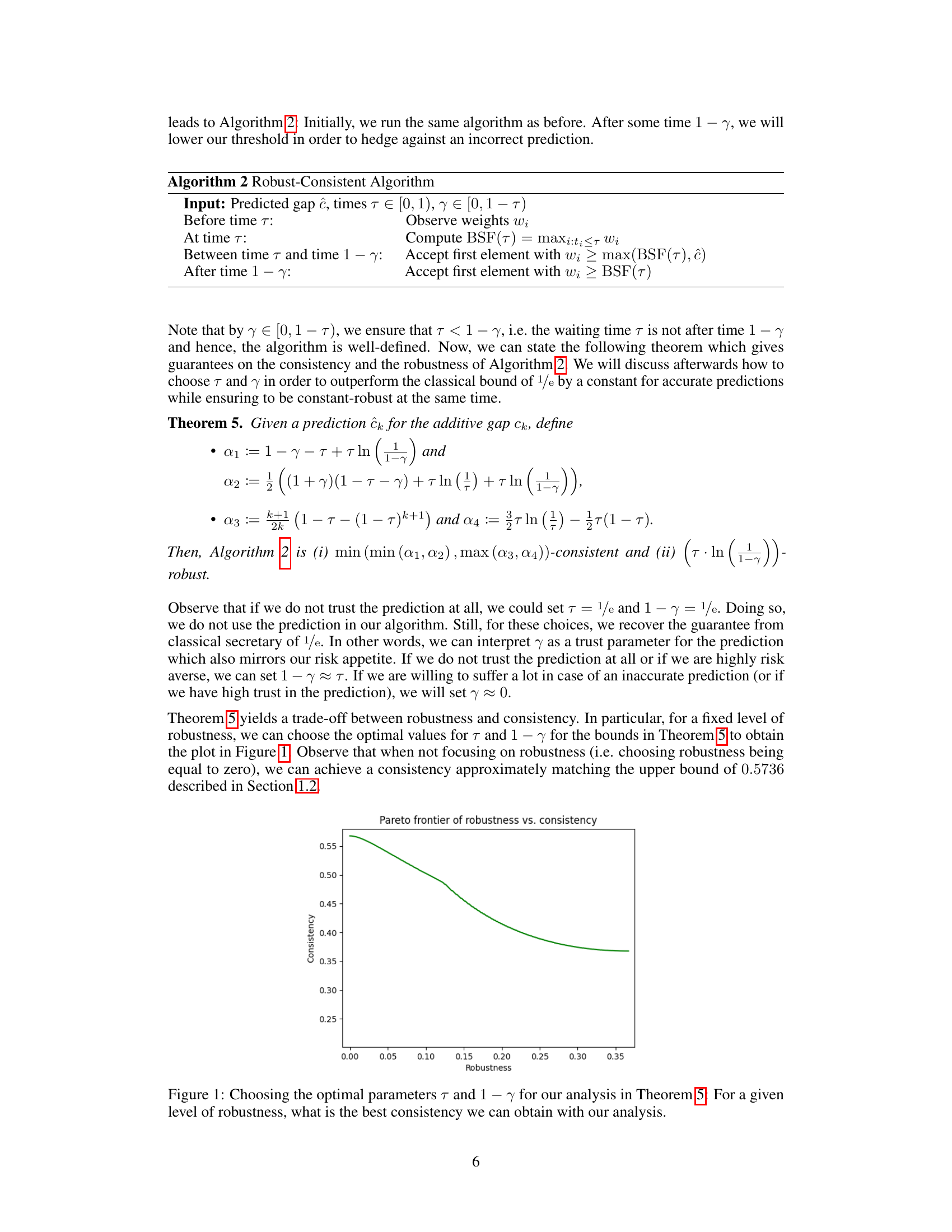

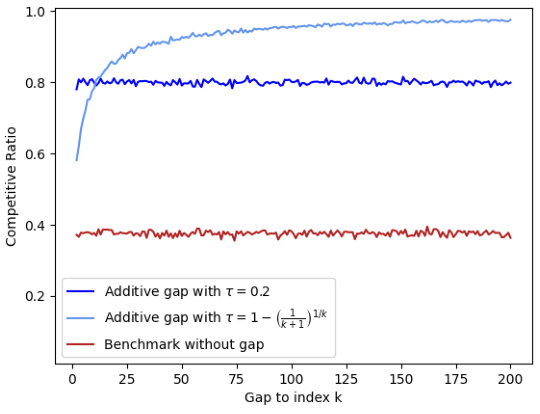

This figure compares the competitive ratios achieved by three different algorithms for weights sampled according to the Pareto distribution (i). The x-axis represents the gap’s index k (ranging from 2 to 200). The y-axis displays the corresponding competitive ratios. Three lines are plotted: one for the proposed algorithm with a fixed waiting time (τ = 0.2), another for the proposed algorithm with a waiting time that depends on k (τ = 1 − (1/(k+1))^(1/k)), and a final line for the classical secretary algorithm (without gap information). The figure showcases the improvement of the proposed algorithm, especially for larger values of k, when compared against the classical secretary algorithm.

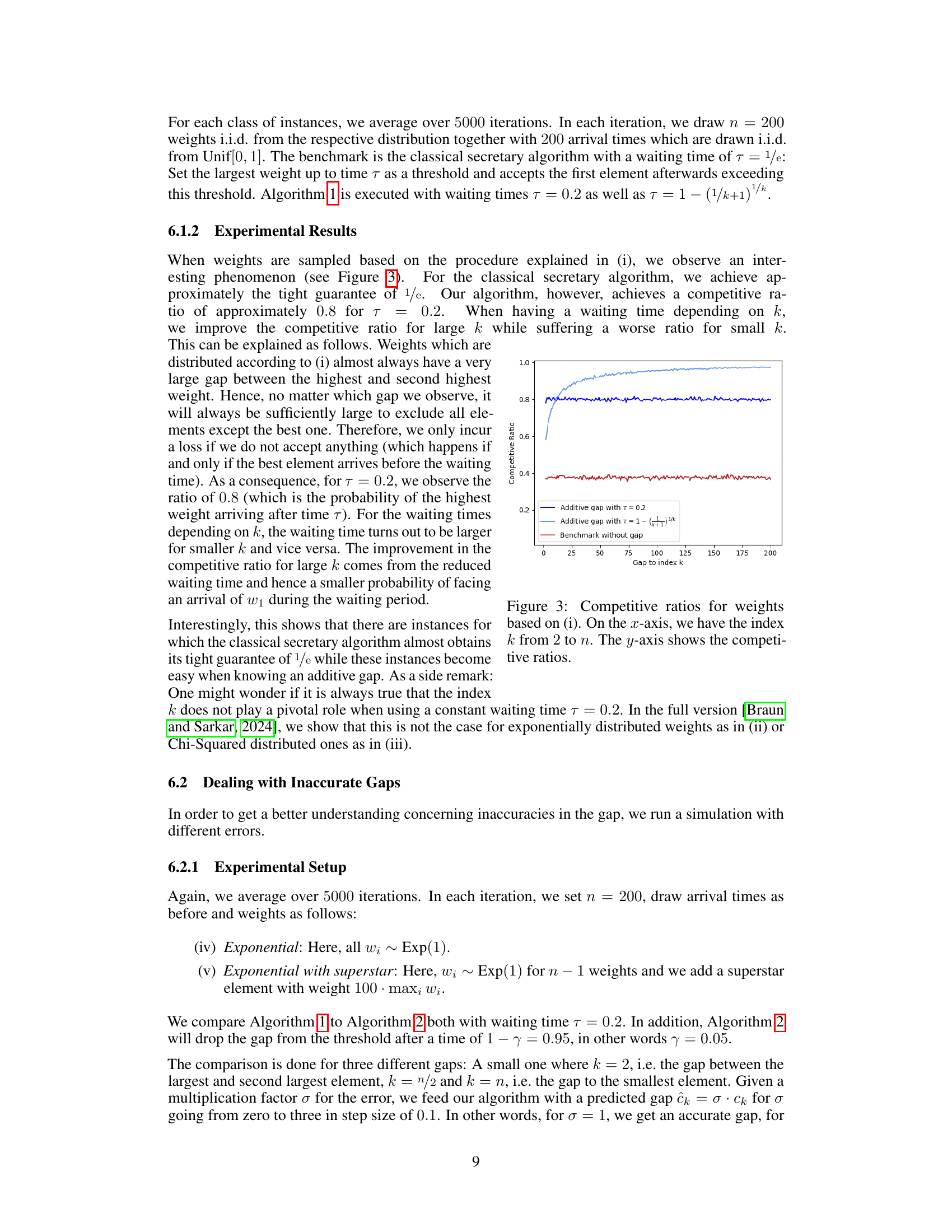

The figure shows the results of simulations comparing Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, both using a waiting time of τ = 0.2. The x-axis represents the error in the predicted gap (σ), ranging from no error (σ=1) to overestimation (σ > 1) and underestimation (σ < 1). The y-axis shows the competitive ratio achieved. Different lines represent different gap indices (k=2, k=100, k=200). The results indicate that underestimation of the gap has less impact on the competitive ratio than overestimation, with Algorithm 2 showing better robustness when overestimation occurs. Note that weights are sampled according to (iv) Experimental Setup in section 6.2.1, meaning weights are sampled from an exponential distribution.

More on tables

This figure shows the Pareto frontier of robustness versus consistency for Algorithm 2, a modified secretary algorithm that incorporates a predicted additive gap. The x-axis represents the level of robustness (the algorithm’s competitive ratio when the predicted gap is inaccurate), and the y-axis represents the level of consistency (the algorithm’s competitive ratio when the predicted gap is accurate). The curve illustrates the trade-off between robustness and consistency; improving one often requires sacrificing the other. The optimal choice of parameters τ and γ (which control the algorithm’s behavior) depends on the desired balance between robustness and consistency.

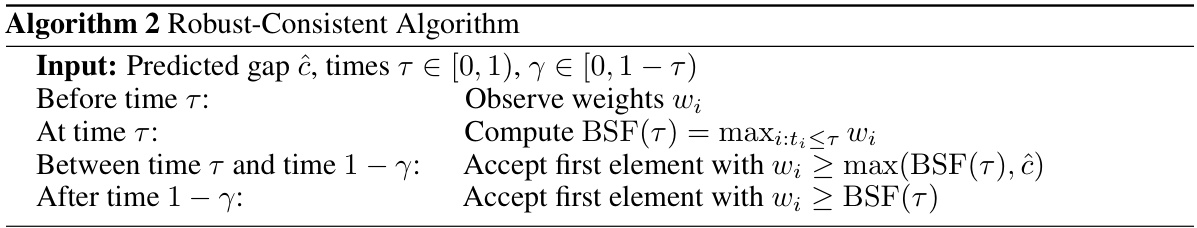

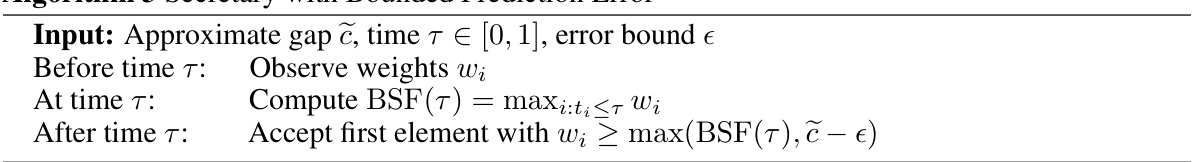

This algorithm is a modification of the secretary problem algorithm that incorporates a bounded error in the predicted additive gap. It observes weights up to a time τ, computes the best-so-far (BSF) value, and then accepts the first element whose weight exceeds the maximum of the BSF and the predicted gap minus the error bound (ẽ - є). This modification aims to improve robustness against inaccurate gap predictions.

Full paper#