↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Neuroscientists use recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to model neural circuit dynamics from experimental recordings. However, these recordings often capture only a small fraction of the neurons. This study investigates whether this partial observation might lead to mechanistic mismatches between real circuits and their data-constrained models.

The researchers found that partial observation can indeed induce mechanistic mismatches, even when the models accurately reproduce the dynamics of individual neurons. Specifically, partially observed models of low-dimensional circuits can exhibit spurious attractor structures, which are not present in the complete system. This highlights that existing approaches may be inadequate for identifying the true mechanisms underlying neural behavior.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals a critical limitation in current neuroscience modeling techniques. By highlighting how partial observation leads to inaccurate mechanistic insights, it urges researchers to adopt more rigorous validation methods and consider alternative experimental designs for studying neural dynamics.

Visual Insights#

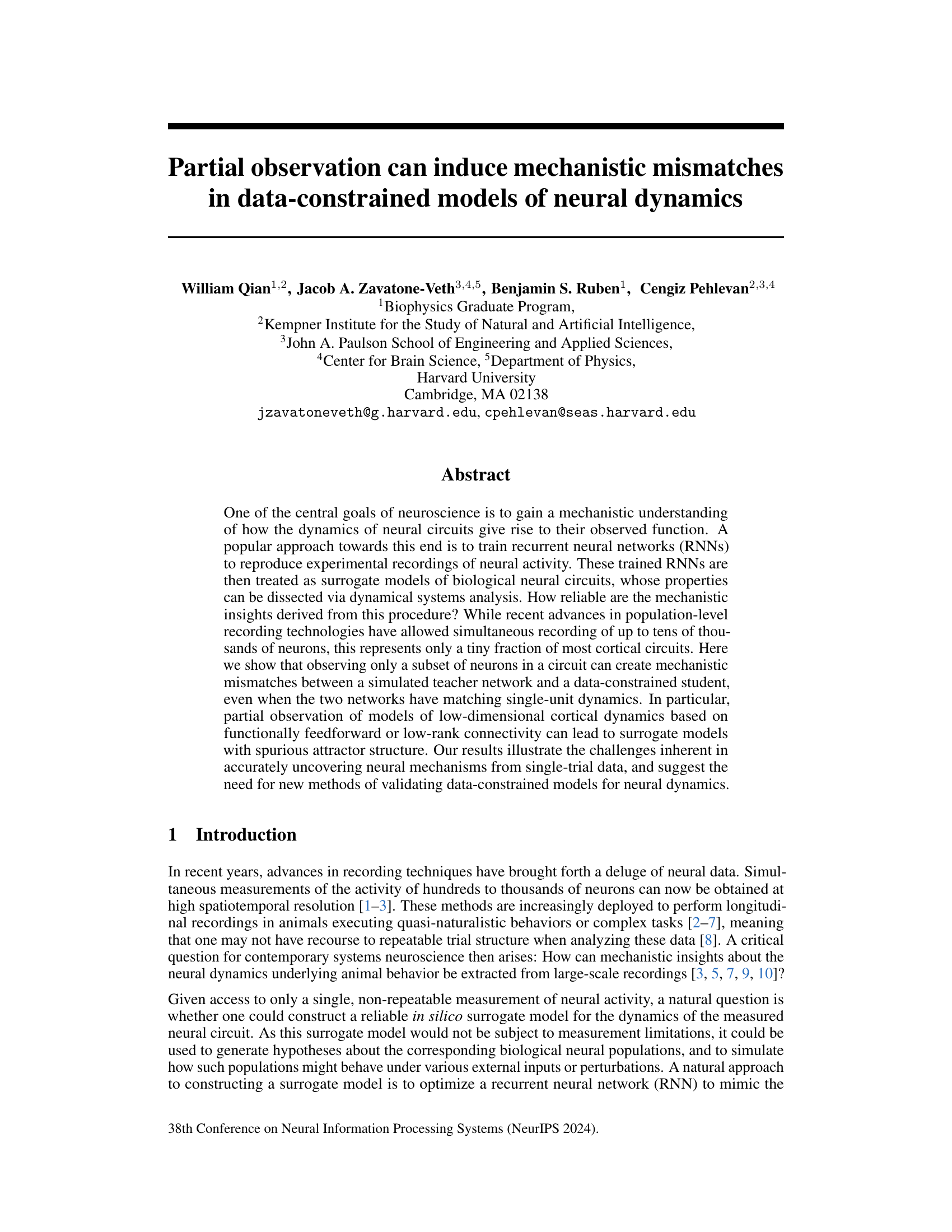

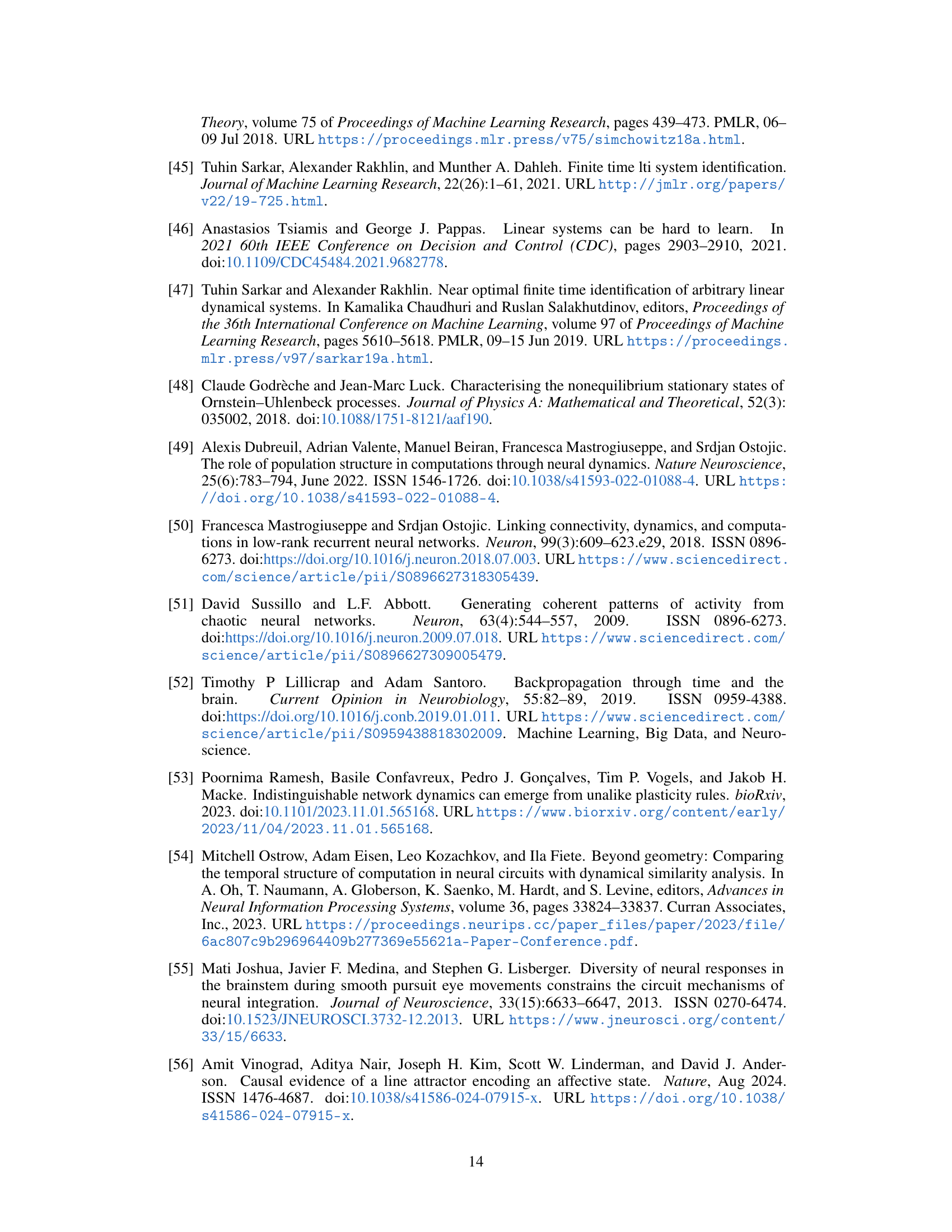

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between two different types of integrator circuits: a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator circuit. Despite successfully reproducing the observed activity, the data-constrained models misinterpret the underlying mechanistic dynamics of the feedforward circuit, highlighting the challenges of inferring mechanisms from partially observed data.

In-depth insights#

Partial Obs. Effects#

The heading ‘Partial Obs. Effects’ likely refers to a section analyzing how observing only a subset of neurons in a neural circuit affects data-driven models of neural dynamics. The core argument is that partial observation can lead to mechanistic mismatches, even when the model accurately reproduces the observed activity of the visible neurons. This mismatch arises because the model compensates for missing information in ways that don’t reflect the true underlying neural mechanisms. Surrogate models trained on partially observed data might exhibit spurious attractor structures or misrepresent the true timescales of the system, leading to inaccurate conclusions about its functional architecture. The research likely investigates this effect across different neural circuit models and network architectures, potentially highlighting the limitations of current data-driven modeling approaches in neuroscience when dealing with incomplete data. New methods to validate data-constrained models are proposed as a necessity given these limitations. The discussion emphasizes the critical need for experimental techniques that go beyond simple recording of neural activity to validate mechanistic hypotheses inferred from partially observed data.

RNN Surrogate Models#

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for creating surrogate models of neural circuits. These models are trained on experimental data to mimic the observed activity of neural populations, enabling researchers to probe circuit dynamics. A key advantage of RNN surrogate models is their capacity for simulation, allowing investigation of circuit behavior under various conditions not easily achievable experimentally. However, the reliability of mechanistic insights from RNN surrogates depends critically on data quality and completeness. Partial observation of neuronal activity is a significant limitation, potentially leading to spurious attractor structures and other mismatches between the model and the biological system. The ability of RNNs to accurately reflect the underlying neural mechanisms is thus strongly influenced by factors like data quality, the extent of partial observation, and the nature of circuit connectivity. Validation techniques that go beyond simple data fitting are essential to ensure that the model’s behavior is indeed a true reflection of the biological circuit, thus enhancing the trustworthiness of any mechanistic conclusions derived from these surrogate models.

Linear Network Analysis#

Linear network analysis offers a simplified yet powerful framework for understanding neural dynamics. By modeling neural circuits as linear systems, researchers can leverage established mathematical tools to analyze stability, response properties, and information processing capabilities. This approach allows for tractable analysis of phenomena such as attractor dynamics, which are crucial for understanding persistent neural activity underlying memory and decision-making. Linearization techniques can also be applied to study the behavior of complex nonlinear circuits near fixed points or equilibrium states. However, the limitations of linear models are significant. Linear models inherently disregard the complex nonlinearities inherent in biological neural systems, which can drastically impact network behavior, particularly concerning emergent phenomena like chaotic dynamics or multi-stability. Therefore, while linear analysis provides valuable insights into simpler models and local circuit dynamics, the results should be interpreted cautiously and complemented by techniques capable of capturing nonlinear effects for a complete understanding of neural circuit function.

Nonlinear Dynamics#

The study of nonlinear dynamics in neural systems is crucial because neural processes are inherently nonlinear. Linear models, while mathematically convenient, often fail to capture essential features of neural activity, such as the presence of multiple stable states, complex bifurcations, and chaotic behavior. Nonlinear dynamical systems analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding how these nonlinear interactions give rise to emergent phenomena in the brain, including things like memory, decision-making, and cognitive function. The paper highlights the challenge of inferring nonlinear mechanisms from data, especially when observations are limited. Partial observation, a common limitation in neuroscience, can lead to inaccurate mechanistic inferences. This limitation is especially concerning given that many interesting dynamical phenomena in neuroscience are inherently nonlinear, and often require complete knowledge of the systems’ dynamics to accurately characterize.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Extending the analytical framework to nonlinear systems is crucial, as real neural dynamics are inherently nonlinear. This would involve developing new mathematical tools to analyze the impact of partial observation on the attractor structure of nonlinear RNNs. Investigating the role of different network architectures and connectivity patterns beyond those considered here is also warranted, especially examining networks with more complex motifs and heterogeneous connectivity. Developing new methods to validate data-constrained models, possibly incorporating direct perturbations of neural activity, is essential for improving the reliability of mechanistic insights. Finally, exploring the influence of additional factors, such as noisy inputs and unobserved inputs, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges in uncovering neural mechanisms from data alone. These future investigations will refine the current understanding and address the limitations of data-driven modeling in neuroscience.

More visual insights#

More on figures

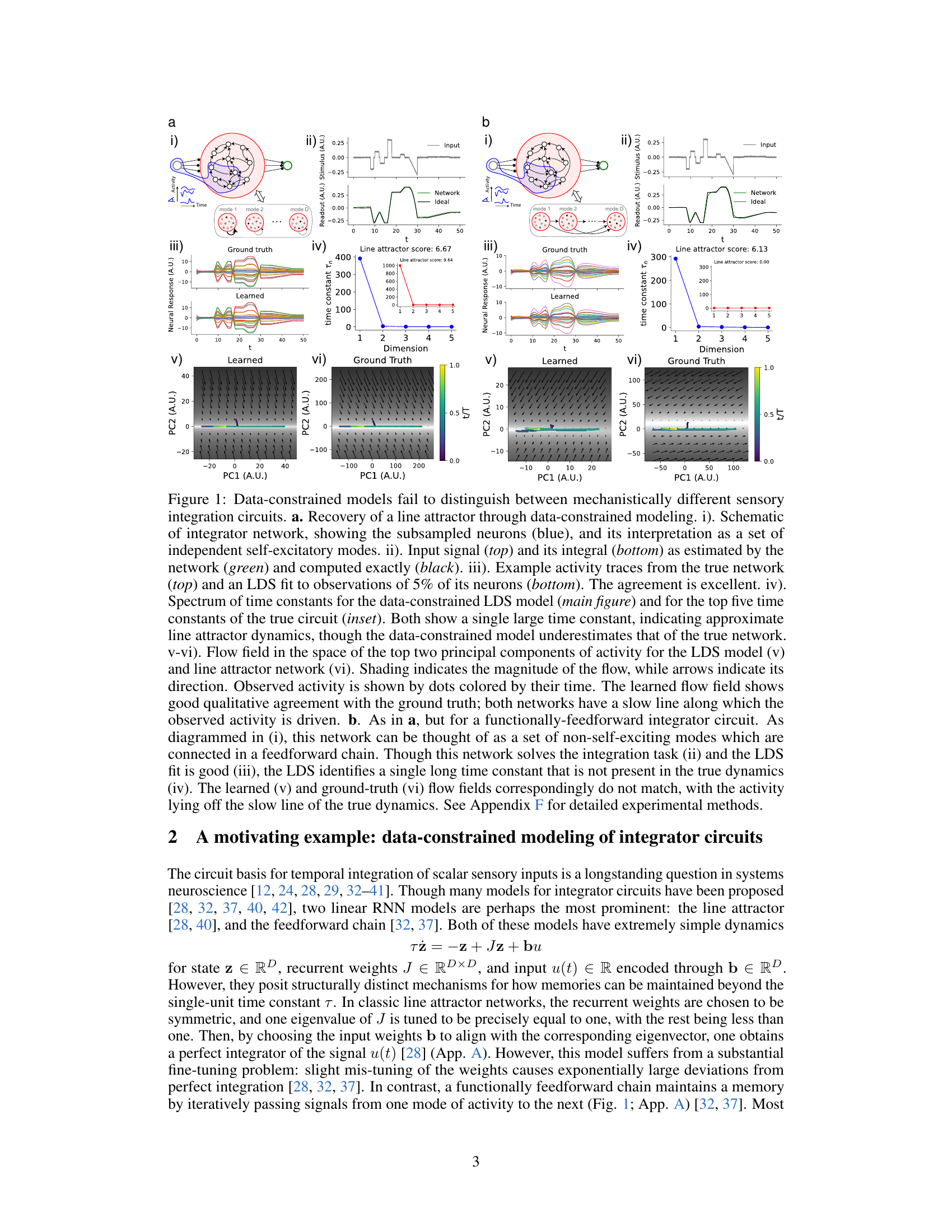

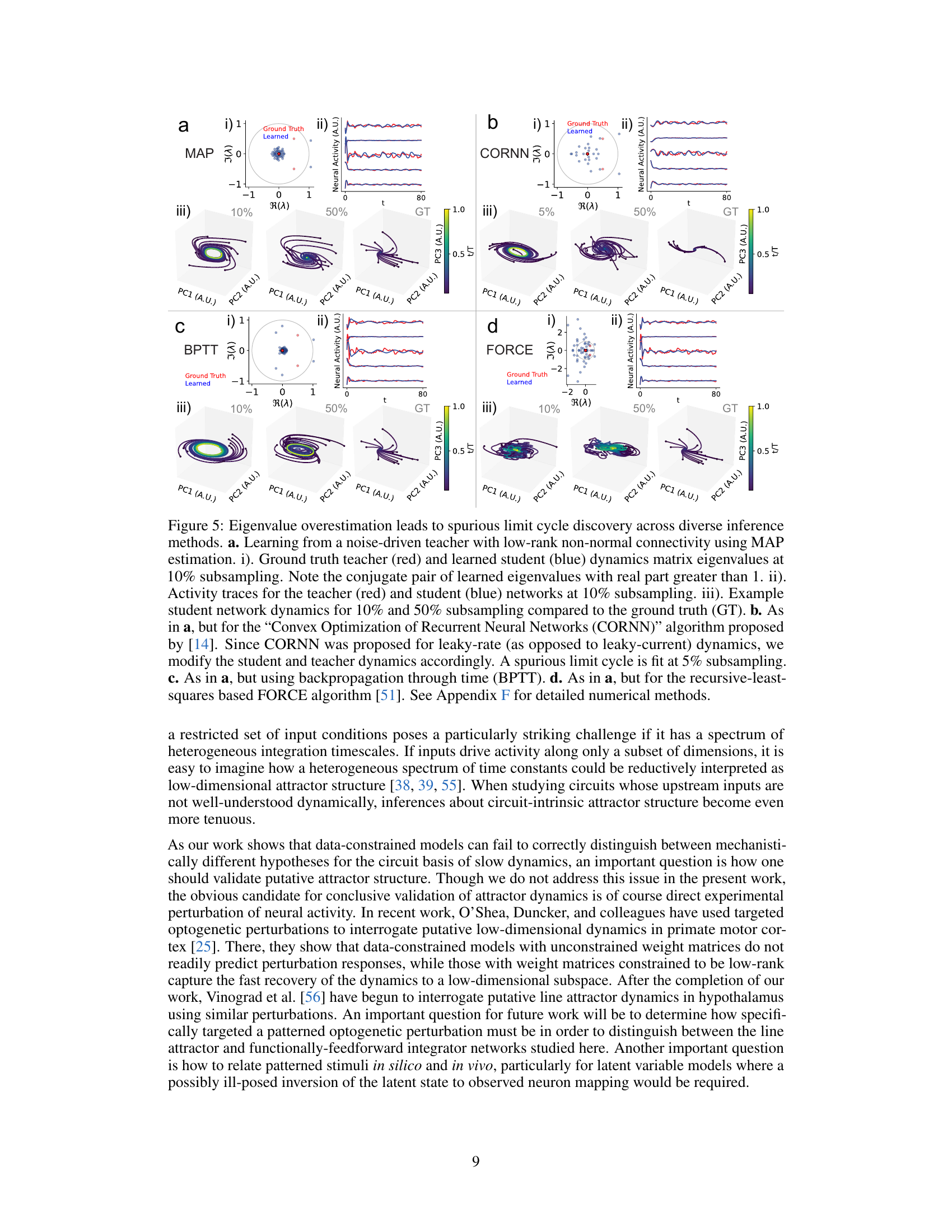

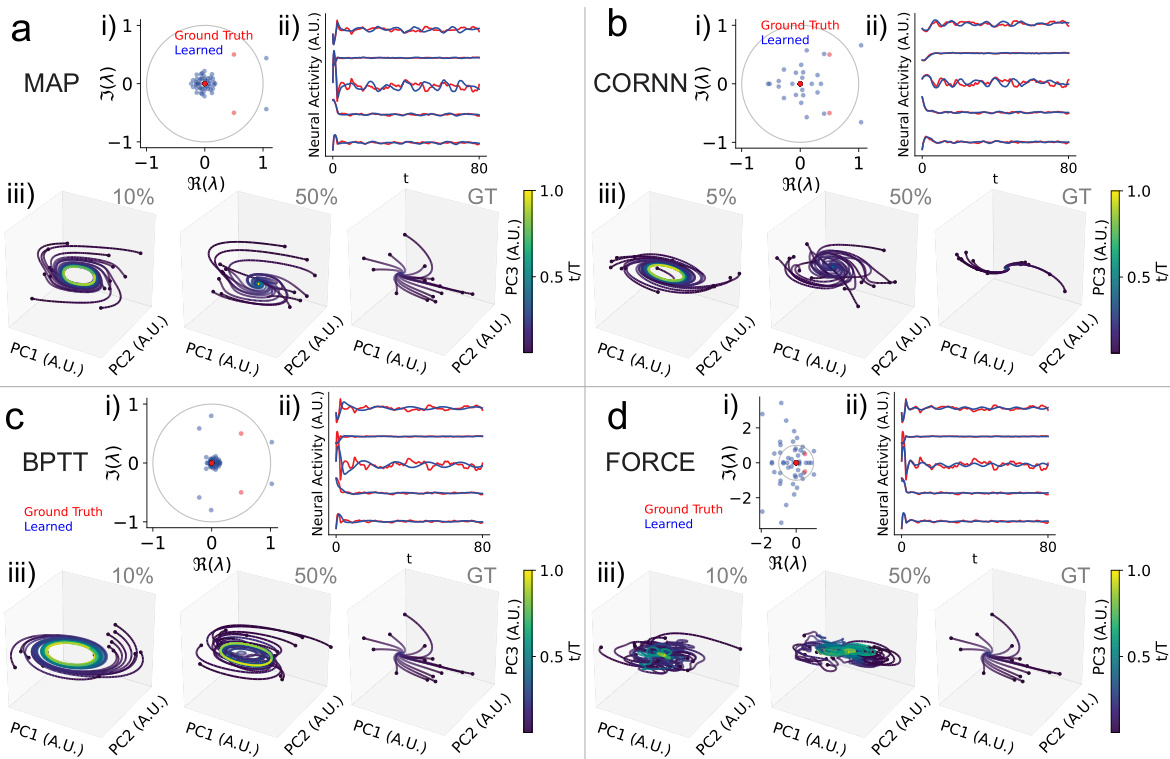

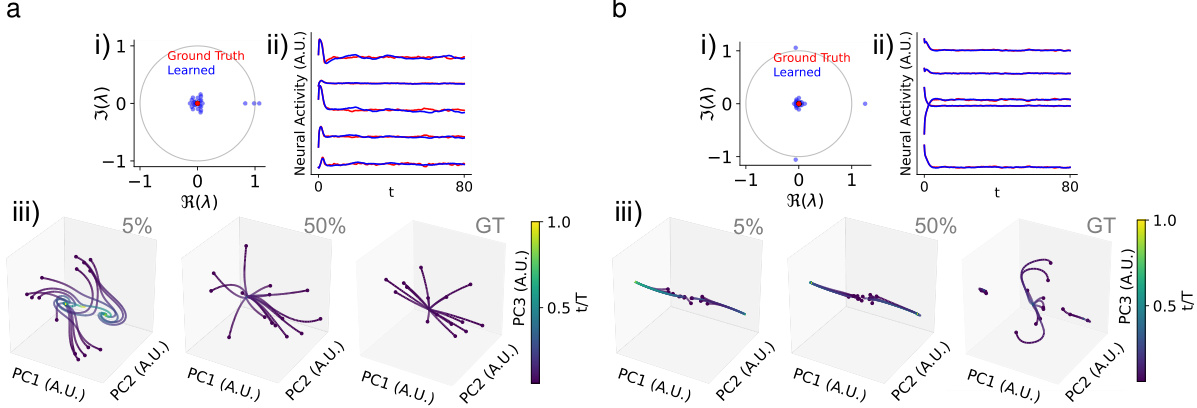

The figure demonstrates that data-constrained models, even with excellent fits to the data, can fail to capture the underlying mechanistic differences between two networks that solve the same task. It shows two different network architectures: a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator circuit. Each network’s activity is analyzed to demonstrate their distinct dynamical properties. The comparison highlights the limitations of using data-driven models to infer true neural mechanisms.

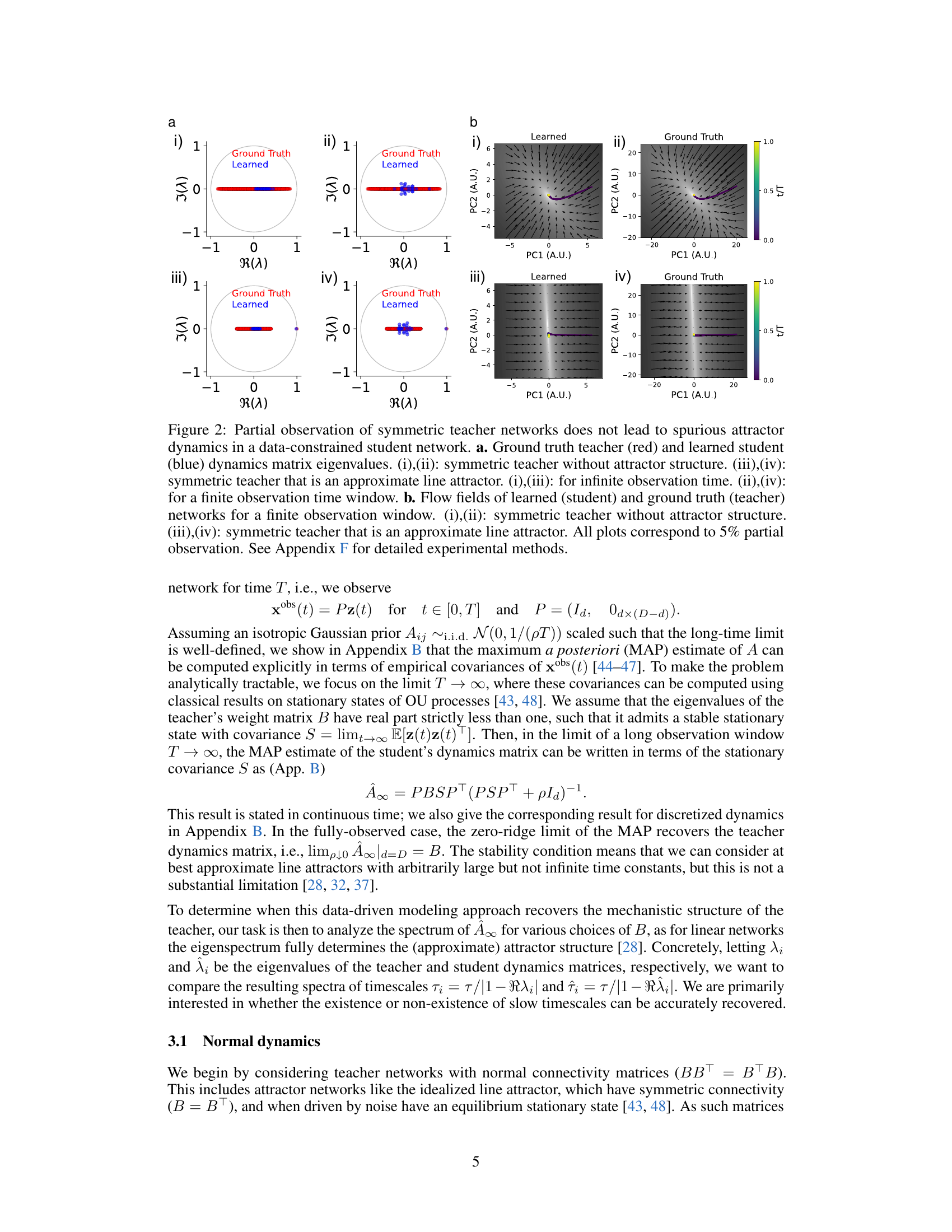

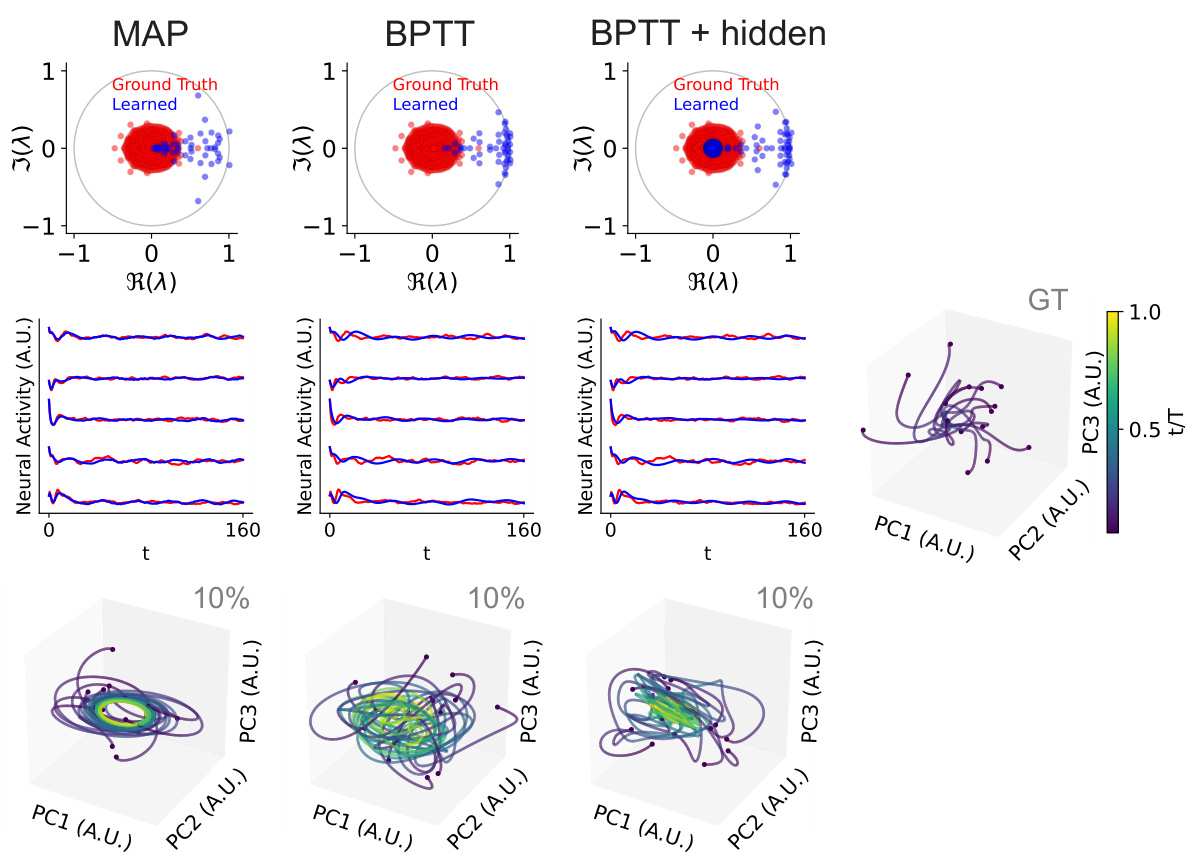

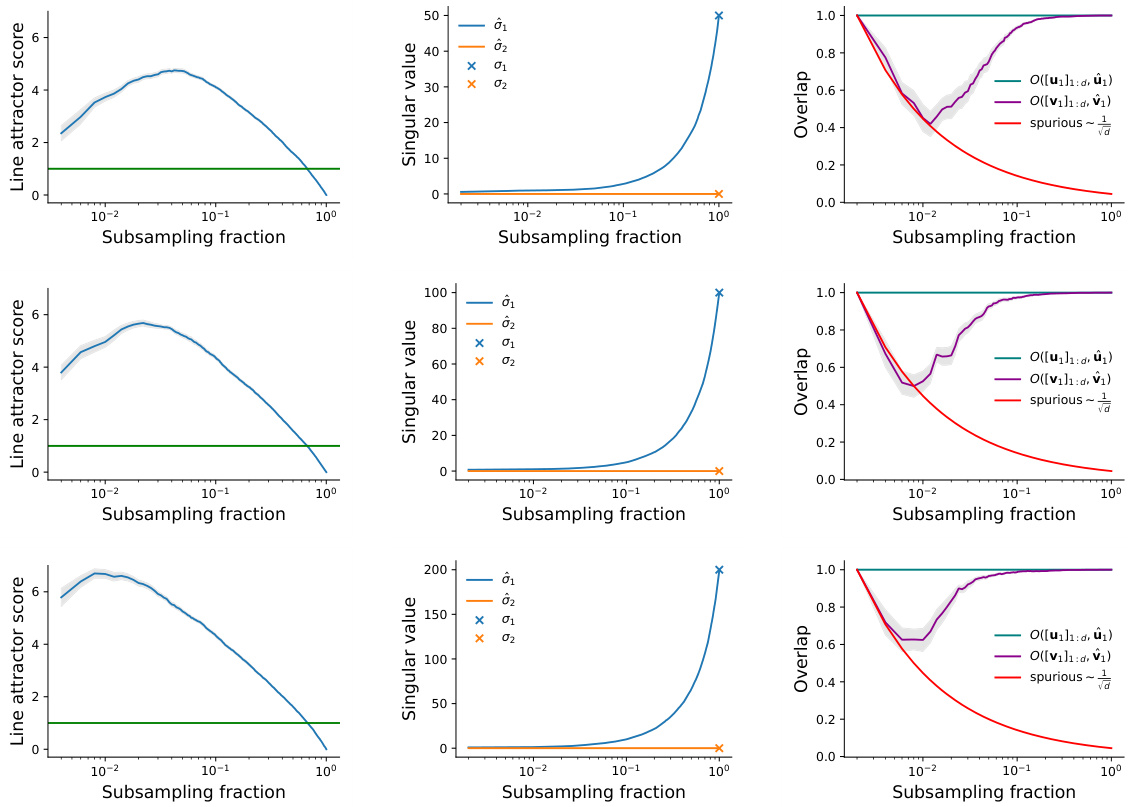

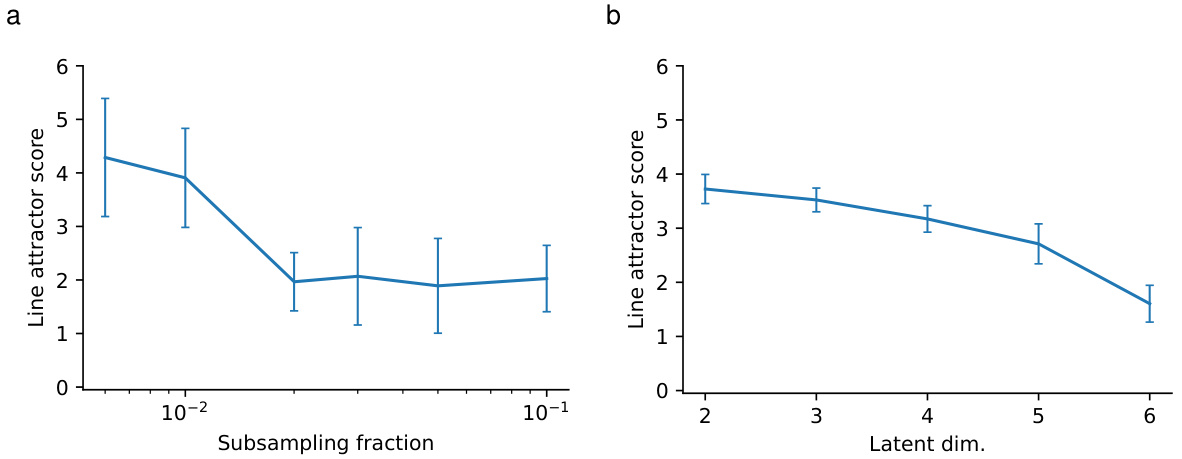

This figure shows that heavily subsampling a feedforward chain leads to line-attractor-like student dynamics. The line attractor score increases as the subsampling fraction decreases, indicating that the student network is more likely to learn line attractor dynamics when fewer neurons are observed. The real parts of the top two eigenvalues of the student’s dynamics matrix increase as the teacher network size increases, and the time constants corresponding to these eigenvalues show a similar trend. The results demonstrate that partial observation can induce mechanistic mismatches, even when the single-unit dynamics of the student and teacher networks match.

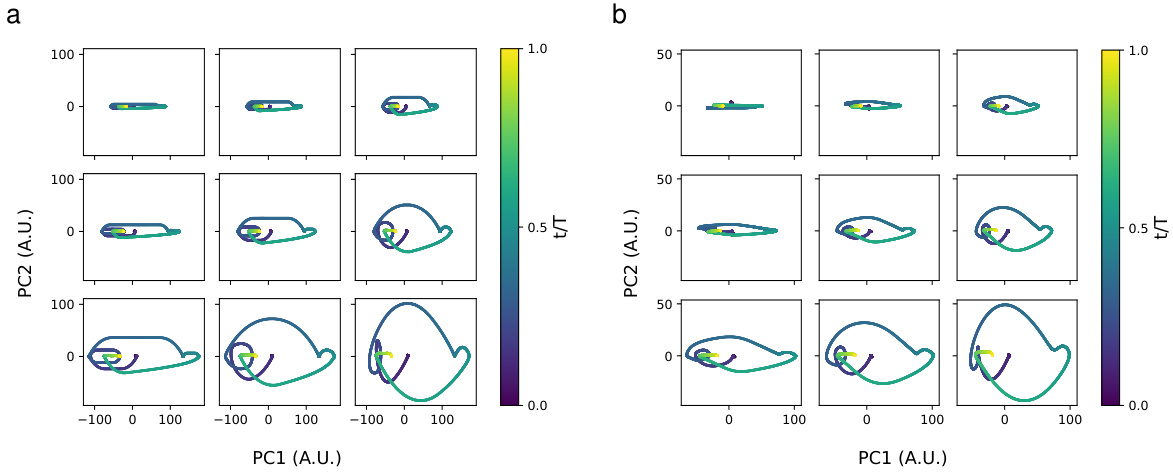

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between two mechanistically different models in a stimulus-integration task. Both a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward chain are identified as line attractors, highlighting a mechanistic mismatch induced by partial observation.

This figure demonstrates that data-constrained models struggle to differentiate between mechanistically distinct neural circuits performing a similar task (sensory integration). It compares a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator network. The data-constrained models successfully reproduce the activity, but dynamical systems analysis reveals mismatches in the underlying mechanisms. Specifically, it highlights how partial observations can lead to inaccurate inferences about the nature of attractor dynamics, even when single-unit dynamics are matched.

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between two mechanistically different sensory integration circuits: a line attractor and a functionally feedforward integrator. Even when the data-constrained model accurately reproduces the observed activity, its underlying dynamics can be qualitatively different from the true network. The figure compares the activity, time constants, and flow fields of both the true networks and their data-constrained models. This highlights the challenges inherent in accurately uncovering neural mechanisms from single-trial data.

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between two different types of neural integrator circuits: a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator network. Both circuits perform the same task, but the underlying mechanisms are different. The figure demonstrates how a data-constrained model (LDS) accurately captures the activity of both networks, but fails to identify the correct underlying mechanism because of partial observation of the network activity.

This figure shows that data-constrained models cannot distinguish between two mechanistically different models for sensory integration: a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator. Both models are trained on data from a subset of neurons, and the figure compares their performance to the full network activity for both types of networks, highlighting how partial observation can lead to misleading conclusions about the underlying mechanisms.

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between two mechanistically different models in a stimulus-integration task. The two models are a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward chain. Both models are identified as line attractors by data-constrained modeling, highlighting a mechanistic mismatch induced by partial observation.

This figure demonstrates that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between mechanistically different sensory integration circuits. It compares two models: a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward integrator network. Both models are trained to perform a stimulus integration task, and their performance is evaluated using various metrics, including activity traces, the spectrum of time constants, and flow fields. The results show that although the data-constrained model accurately reproduces the activity of both networks, it incorrectly identifies both as line attractors, despite their different underlying mechanisms. This highlights the challenges of inferring mechanistic insights from data-constrained models alone.

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between mechanistically different sensory integration circuits. The authors use two different types of integrator networks (line attractor and feedforward) and compare their performance with a data-constrained model (LDS). The results show that while both networks solve the integration task, the LDS model fails to distinguish between them mechanistically, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on data-driven models for understanding neural circuits.

This figure shows that data-constrained models cannot distinguish between two different models of neural integrator circuits, even though both models successfully perform an integration task. The models are a line attractor network and a functionally feedforward network. The figure compares the activity, spectrum of time constants, and flow fields of both true networks and their learned LDS (linear dynamical system) counterparts. The results highlight a failure of data-constrained models to identify the correct mechanistic structure, despite successful behavioral performance.

This figure shows that data-constrained models fail to distinguish between mechanistically different sensory integration circuits (line attractor vs. feedforward). Despite excellent fits to the observed activity, the learned models (LDS) misinterpret the underlying dynamics, highlighting the challenges of inferring mechanisms from limited data.

Full paper#