↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Procedure learning from videos is challenging due to temporal variations (non-monotonic actions, background frames) and inconsistencies across videos. Existing methods often rely on frame-to-frame matching or assume monotonic alignment, leading to suboptimal results. This limits the ability to accurately identify key steps and their sequential order in a complex task.

To address these challenges, the authors propose OPEL, a novel procedure learning framework that uses optimal transport (OT) to model the distance between video frames as samples from unknown distributions. This allows for the relaxation of strict temporal assumptions. OPEL further incorporates optimality and temporal priors, regularized by inverse difference moment and KL-divergence, to enhance the OT formulation and improve temporal smoothness. The resulting framework outperforms the state-of-the-art on benchmark datasets, achieving significant improvements in both accuracy and F1-score.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to procedure learning that significantly outperforms current state-of-the-art methods. It addresses key limitations of existing techniques by leveraging optimal transport, offering a more robust and flexible solution for analyzing video data. This opens new avenues for research in various applications requiring procedure understanding, such as autonomous agents, human-robot collaboration, and educational technology. The proposed optimal transport guided procedure learning framework (OPEL) has the potential to substantially improve the performance of systems that need to learn and replicate complex human actions from video data.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the challenges in procedure learning. It shows three example videos (V1, V2, V3) of someone making brownies. Each video shows the same five key steps (break egg, mix egg, add water, add oil, mix contents), but the order and timing of the steps vary across videos. Some videos include extra frames that are not part of the main procedure (background frames), while others show steps that are out of order (non-monotonic frames). The figure also shows how OPEL addresses these issues by learning an embedding space where frames with the same semantics (representing the same key step) are grouped together, regardless of temporal inconsistencies or extra frames.

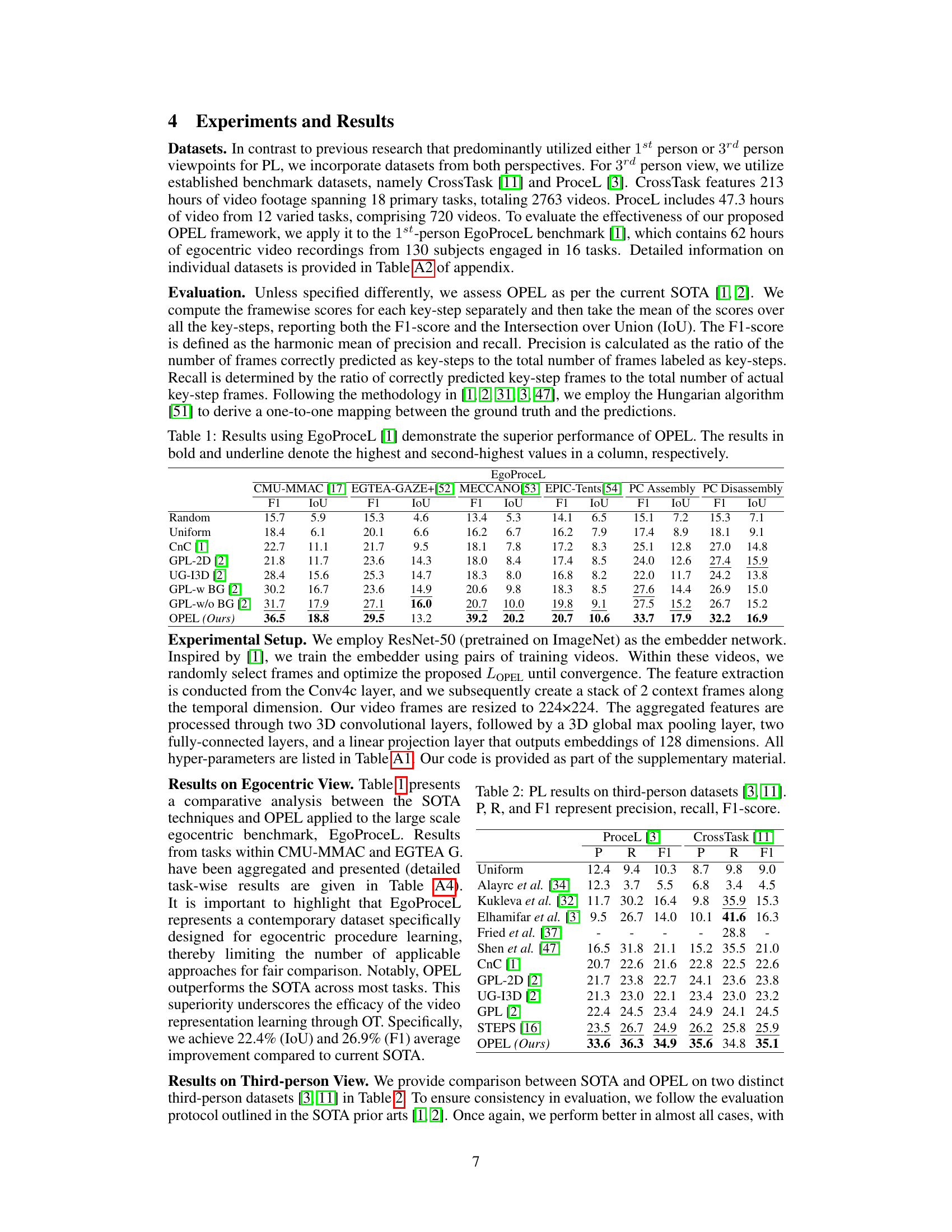

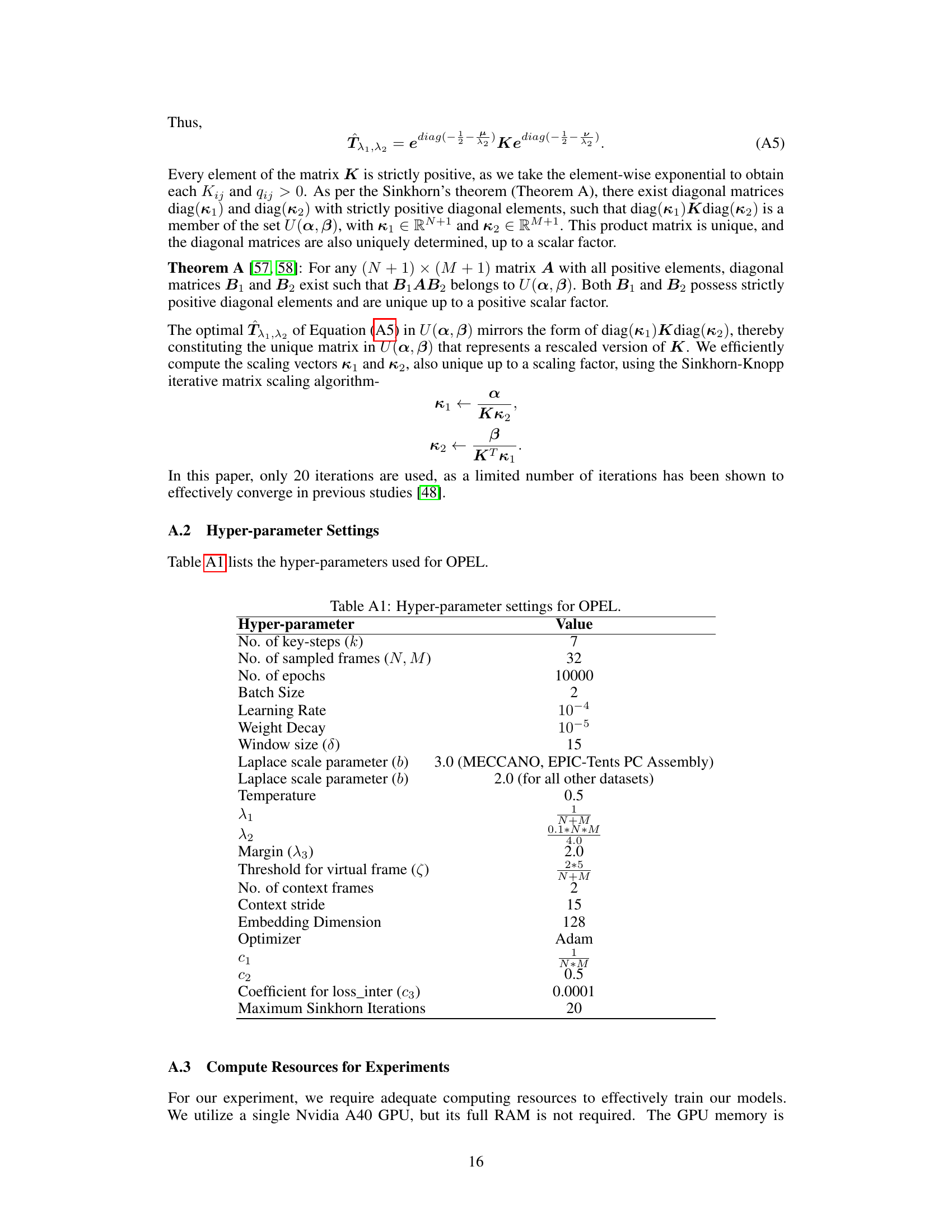

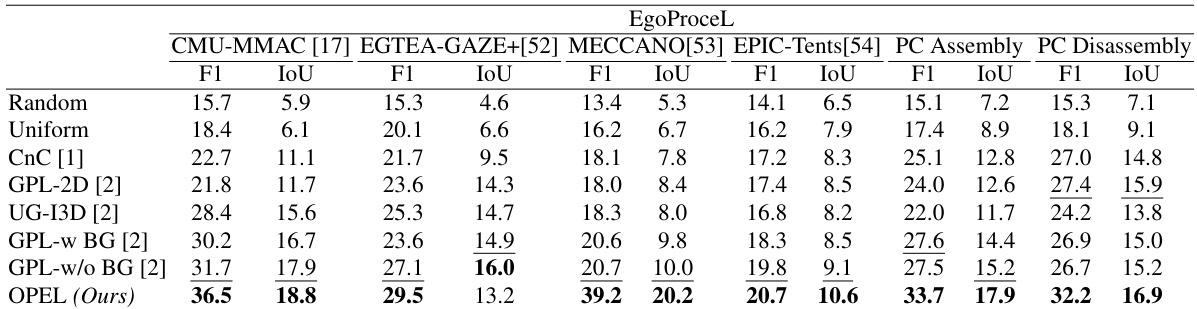

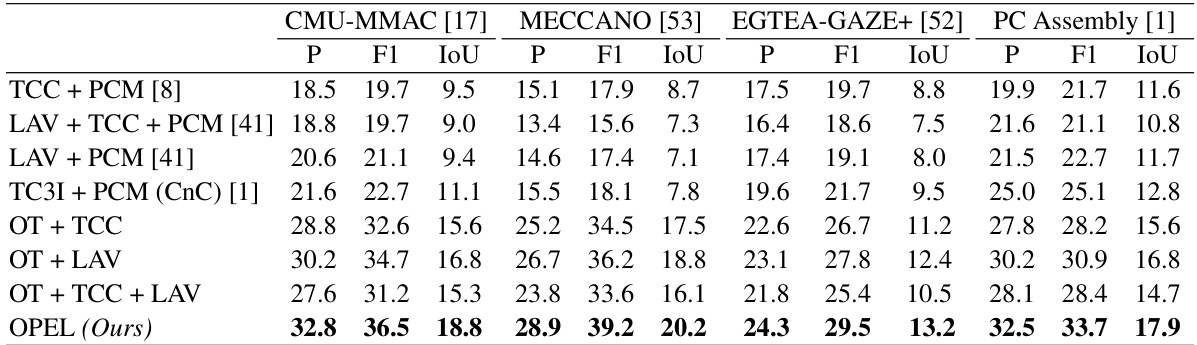

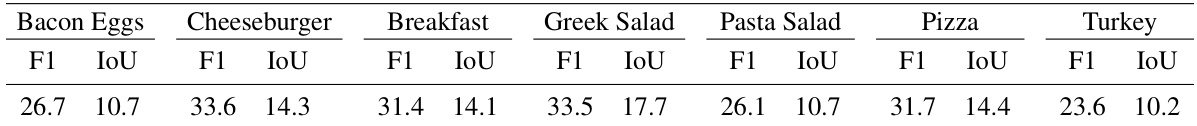

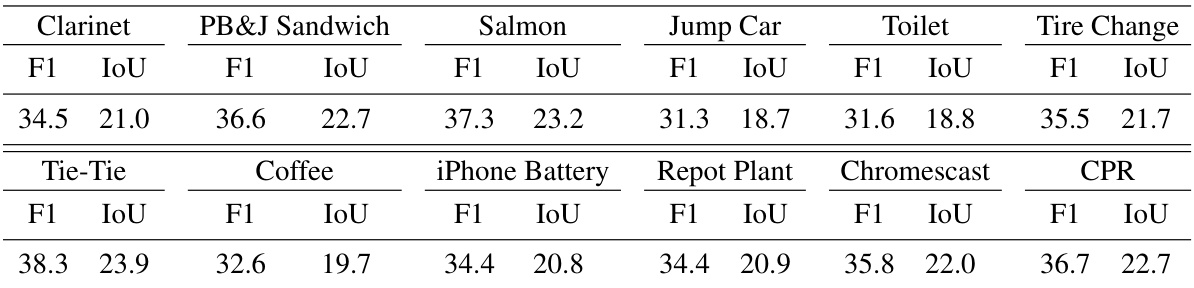

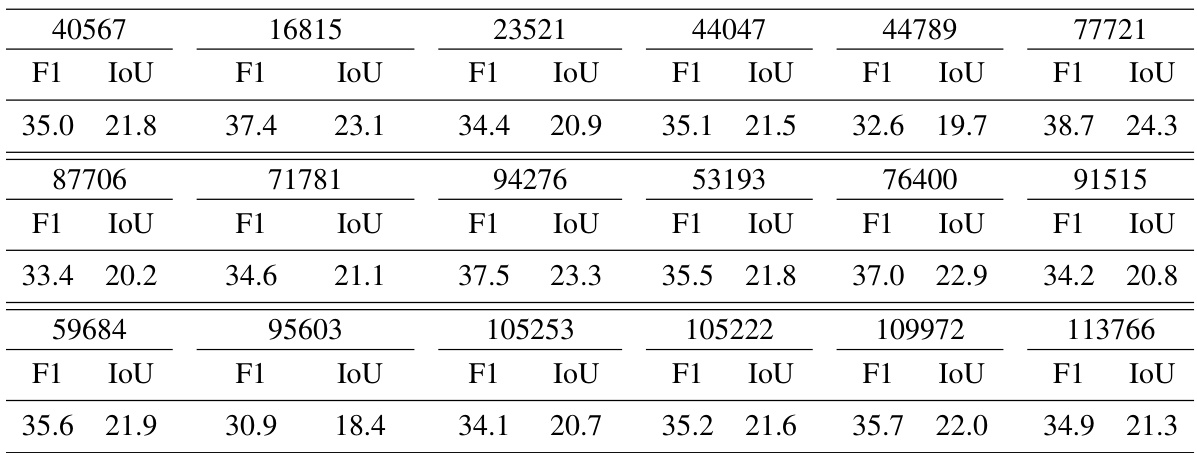

This table presents a comparison of the proposed OPEL method against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches for egocentric procedure learning on the EgoProceL benchmark dataset. The table shows the F1-score and Intersection over Union (IoU) metrics for each method across various tasks. The results highlight that OPEL significantly outperforms other methods across all tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness in solving the challenging problem of procedure learning from egocentric videos.

In-depth insights#

Optimal Transport PL#

Optimal Transport Procedure Learning (PL) presents a novel approach to procedure learning by framing the problem within the context of optimal transport. This method moves beyond traditional frame-to-frame comparisons, allowing for more flexible and robust alignment of video sequences, even in the presence of variations in speed, non-monotonic actions, or irrelevant frames. By treating video frames as samples from probability distributions, the technique calculates distances using optimal transport, promoting alignment of semantically similar frames across different videos. The integration of optimality and temporal priors further enhances the method’s ability to handle temporal irregularities. The use of a contrastive loss prevents trivial solutions and improves overall performance. This approach demonstrates significant improvements over state-of-the-art methods on various benchmark datasets. The advantages stem from its ability to account for diverse temporal dynamics, making it more adaptable to real-world scenarios.

Prioritized OT Alignment#

Prioritized Optimal Transport (OT) alignment is a crucial concept for tasks involving the alignment of sequences with varying lengths or non-monotonic relationships. Standard OT struggles with these scenarios, often leading to suboptimal or misleading alignments. A prioritized approach addresses this by incorporating a mechanism to weight or rank the importance of different alignment matches. This prioritization could leverage external information, such as temporal proximity, semantic similarity, or confidence scores derived from other modules of a larger system. The weights would then be integrated into the OT cost matrix, influencing the final transport plan. This method allows for a more robust and accurate alignment, especially in complex scenarios involving noise or missing data, making it particularly valuable in applications like video alignment or procedural learning. Prioritization offers flexibility, enabling the integration of various heuristics or domain-specific knowledge to guide the alignment process beyond basic distance metrics. However, careful design of the prioritization scheme is essential, to avoid introducing bias or unintended consequences. A poorly designed prioritization could overshadow important, albeit less salient, matches. Therefore, effective prioritization necessitates careful consideration of the specific application and potential sources of bias in the data.

Egocentric & Exocentric PL#

A comparative analysis of egocentric and exocentric perspectives in procedure learning (PL) reveals crucial differences in data acquisition and model training. Egocentric PL, using first-person viewpoints, captures the learner’s subjective experience, potentially including irrelevant details, while exocentric PL, employing third-person views, offers a more objective perspective, focusing on task-relevant actions. However, egocentric data may reflect natural human behavior and provide richer contextual information that exocentric data might miss. Model training strategies should be tailored to each perspective’s strengths and weaknesses; egocentric models may benefit from techniques to filter out irrelevant information, while exocentric models may need to incorporate methods to infer hidden contextual clues from observed actions. Comparative evaluations across both perspectives are critical for developing robust and generalizable PL models that can adapt to various scenarios and capture the full spectrum of human procedure execution.

OPEL Framework#

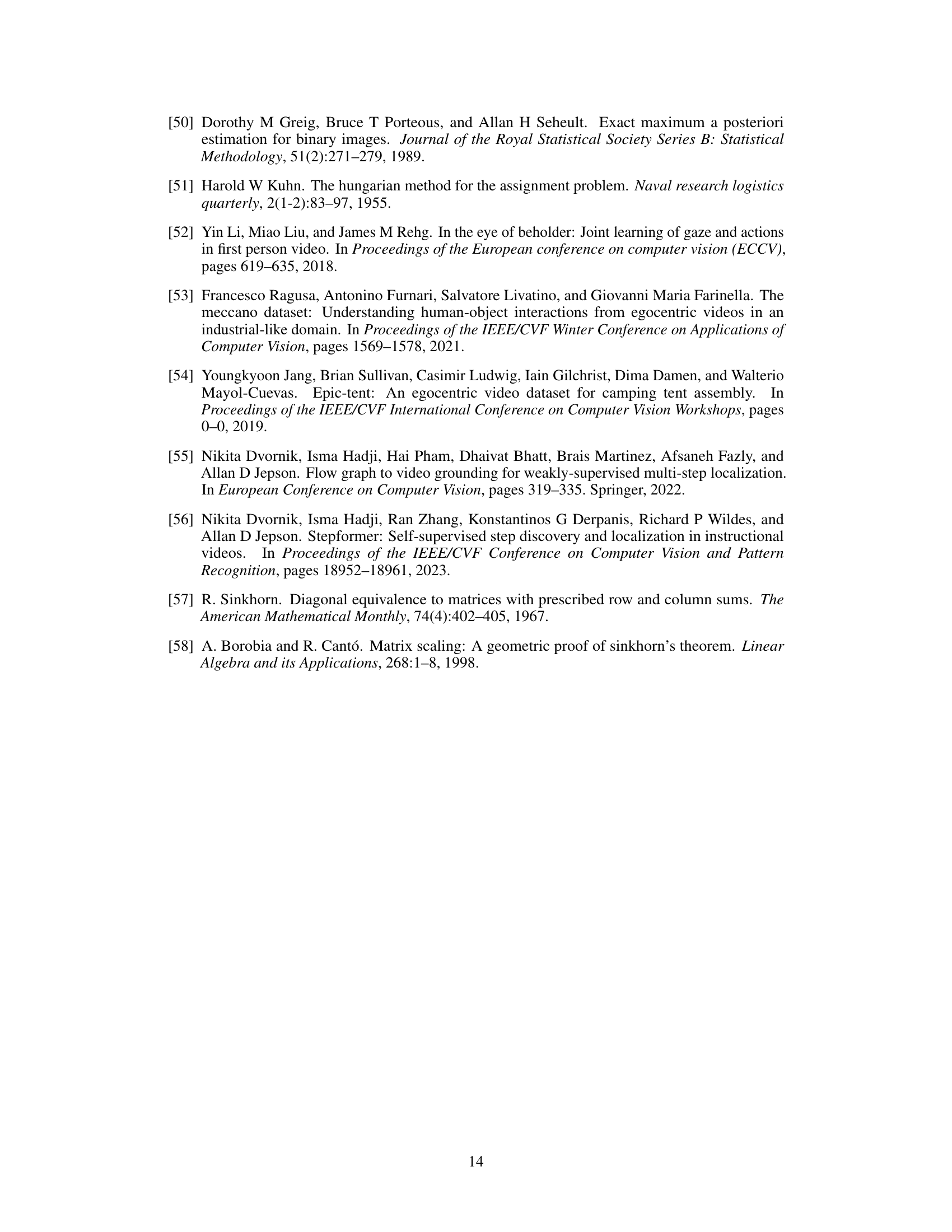

The OPEL framework, as described in the research paper, centers around optimal transport (OT) for procedure learning. It innovatively treats video frames as samples from distributions, calculating distances using OT. This approach elegantly handles temporal irregularities in videos, such as non-monotonic actions or irrelevant frames. Two regularization terms enhance the OT formulation. The first, inverse difference moment regularization, promotes alignment of homogeneous frames in embedding space that are also temporally close. The second, KL-divergence based regularization, prioritizes alignment conformity to the OT solution while enforcing temporal priors. The framework outperforms current state-of-the-art methods on various benchmarks. A key component involves integrating an additional virtual frame in the OT matrix to specifically handle background or redundant frames, improving accuracy. Ultimately, OPEL showcases the power of OT for procedure learning by successfully addressing limitations of previous approaches that relied on strict assumptions or suboptimal alignment strategies.

Ablation & Future Work#

An ‘Ablation & Future Work’ section would critically analyze the impact of individual components within the proposed optimal transport guided procedure learning (OPEL) framework. Ablation studies would systematically remove or alter parts of OPEL (e.g., the optimality prior, temporal prior, contrastive loss) to assess their individual contributions and the overall system’s robustness. This would help determine the relative importance of each module and justify design choices. The future work section could then explore promising avenues of improvement. This might include investigating alternative distance metrics beyond optimal transport for frame alignment; exploring ways to incorporate additional modalities (e.g., audio, text) to enhance accuracy and generalization; and developing methods to handle more complex scenarios, such as those with significant variations in speed, actions, or objects between demonstrations. Addressing the limitations of relying on similar object usage for successful key-step identification across videos is crucial for broader applicability. Ultimately, this section should position OPEL for future advances and suggest directions for broader impact within the field of procedure learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the OPEL framework. (A) shows how the encoder generates frame embeddings for videos. (B) showcases different alignment scenarios from perfectly synchronized to various temporal variations and non-monotonic cases. (C) demonstrates how the optimality and temporal priors align a single frame from Video 2 with its best match in Video 1 using Laplace distribution. (D) visualizes the overall optimal frame sequence alignment based on these priors.

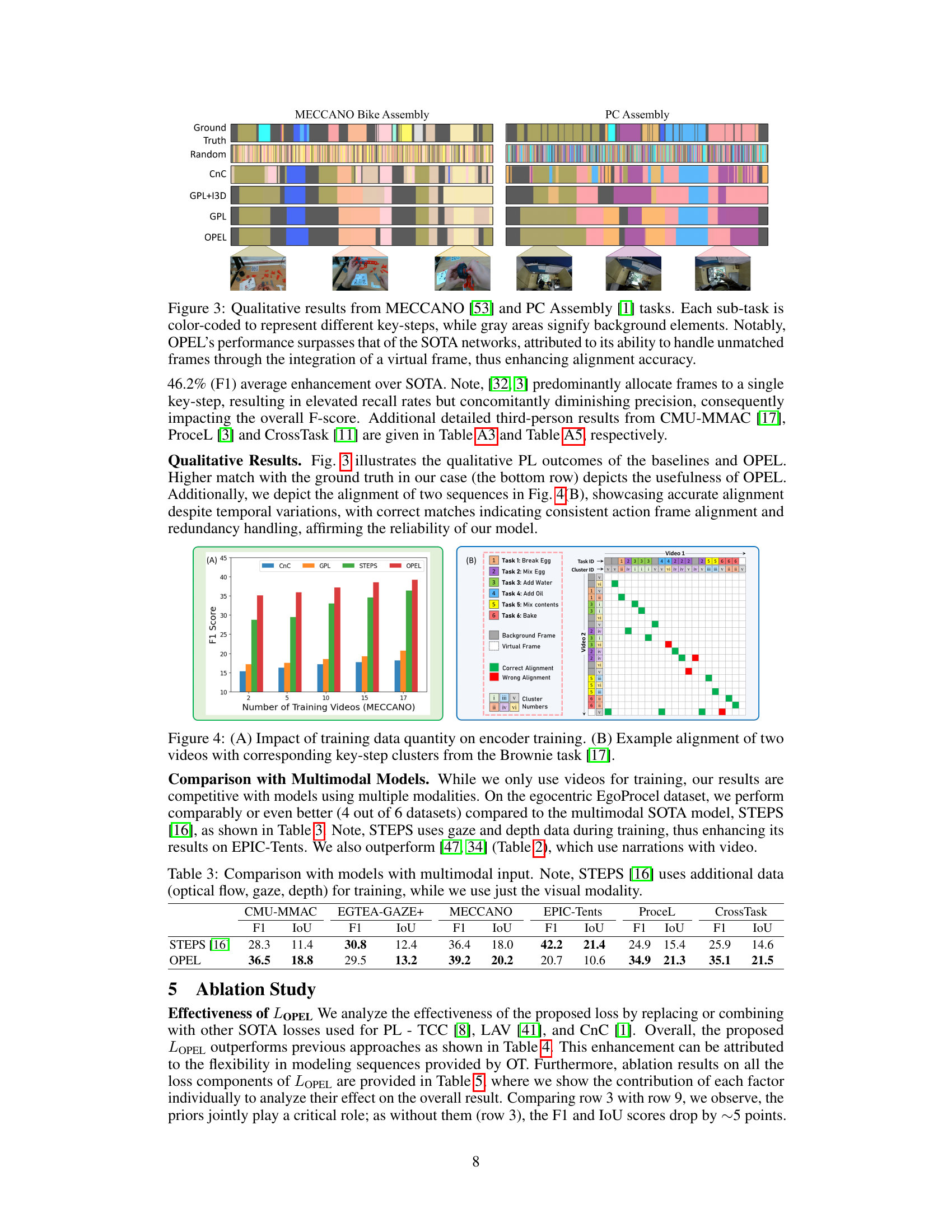

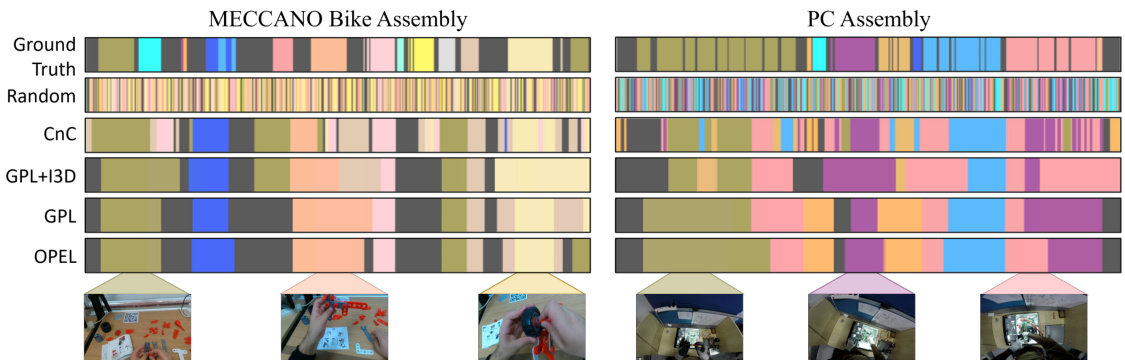

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of the proposed OPEL method against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches for procedure learning on two benchmark datasets: MECCANO and PC Assembly. Each row represents a different method (Ground Truth, Random, CnC, GPL+I3D, GPL, and OPEL), and each column shows the results for one of the datasets. Within each row and dataset, the vertical bars represent the frames of the video, and each color corresponds to a different key-step in the procedure. Gray represents frames that were not assigned to a key-step. The figure shows that OPEL significantly improves the accuracy of key-step identification and alignment compared to the SOTA methods. This improvement is attributed to OPEL’s ability to handle unmatched frames through the use of a virtual frame in its optimal transport formulation.

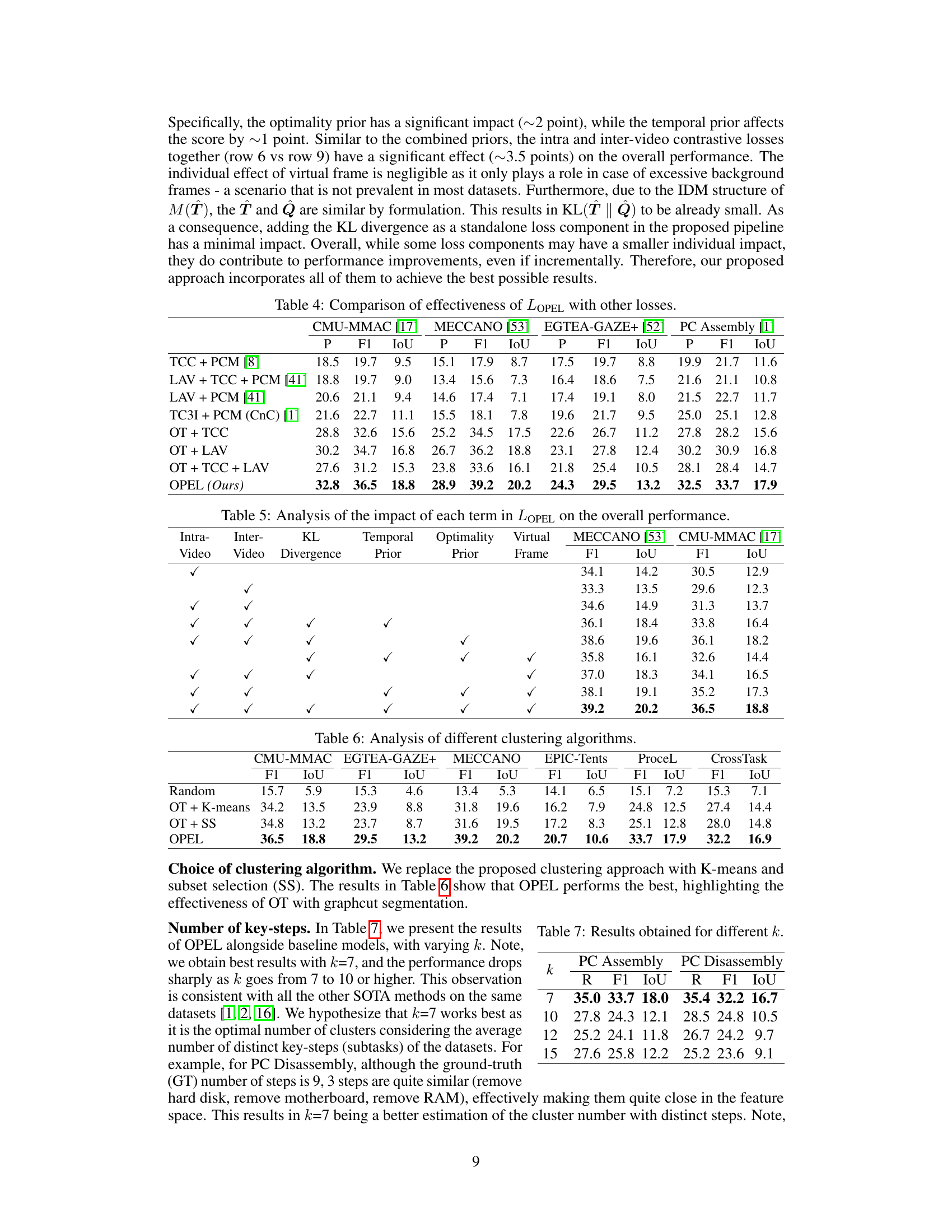

Figure 4(A) shows the effect of varying the number of training videos on the F1 score using the MECCANO dataset. It demonstrates that OPEL consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art methods, even with a small number of training videos. Figure 4(B) illustrates the alignment between two videos of the brownie-making process, showing how OPEL accurately identifies corresponding key-steps despite temporal variations. The visualization uses color-coding to highlight correct and incorrect alignments, and also visualizes background and virtual frames.

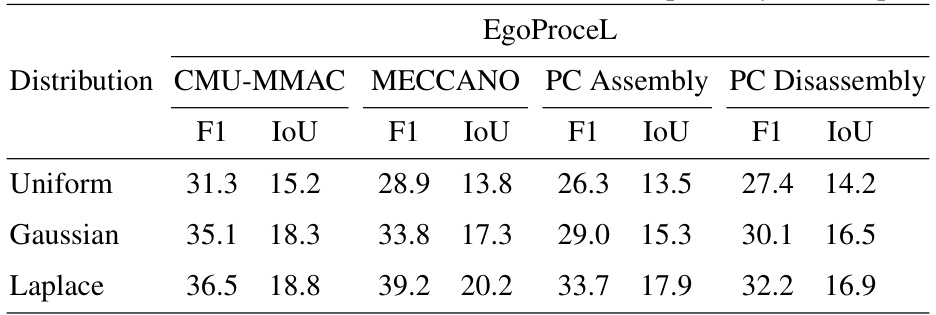

This figure compares the probability density functions (PDFs) of Laplace, Gaussian, and Uniform distributions. It highlights that the Laplace distribution is better suited for modeling the alignment of video frames because it has heavy tails, which can better capture outliers or non-monotonic alignments that deviate significantly from the mean. The Gaussian distribution is more sensitive to outliers and lacks the ability to capture such deviations, while the Uniform distribution does not accurately reflect the true distribution of frame alignments, which is likely to be skewed.

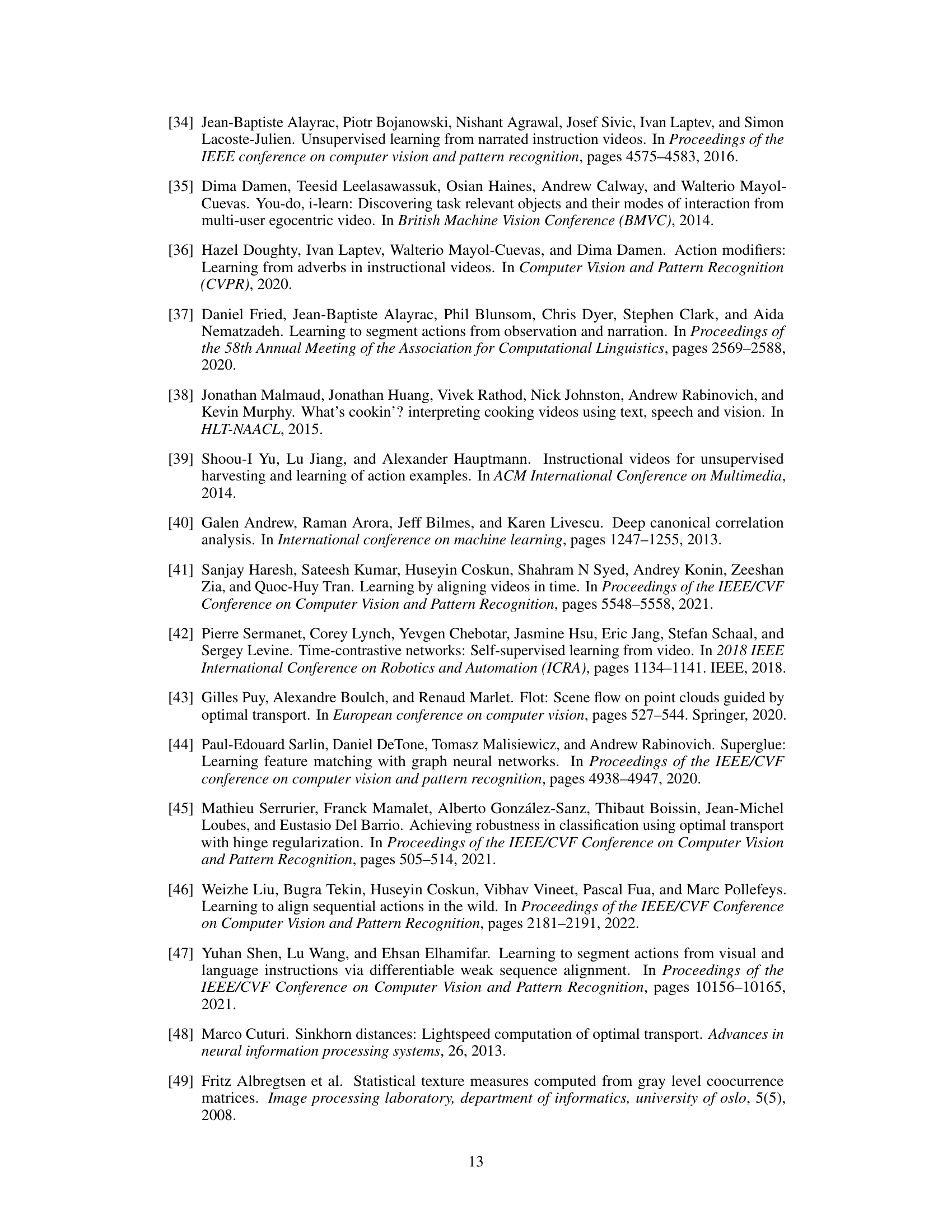

More on tables

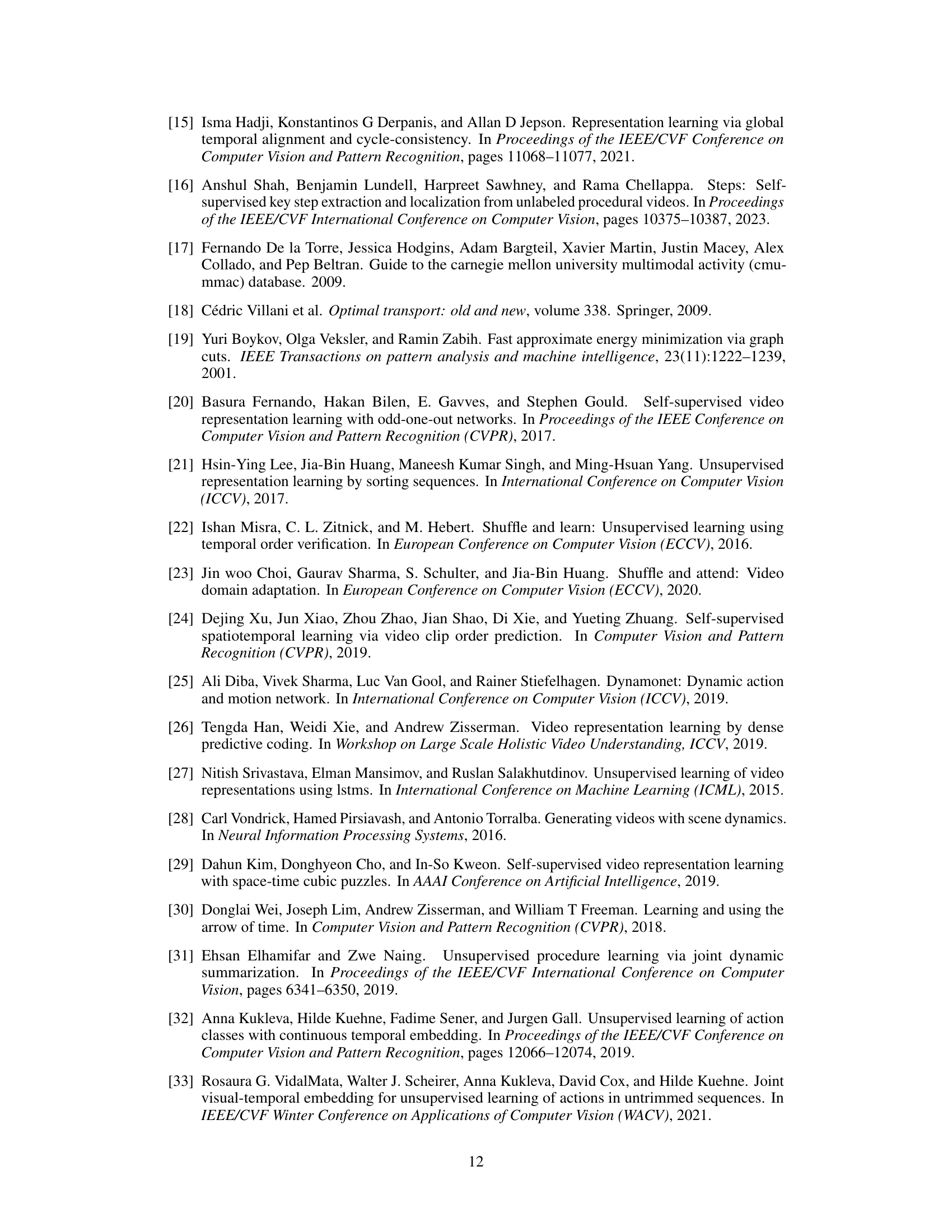

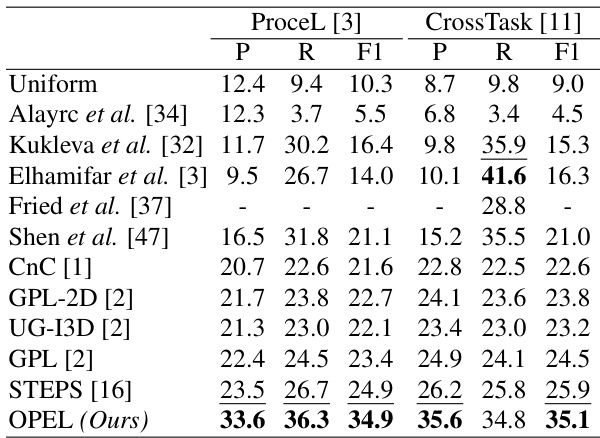

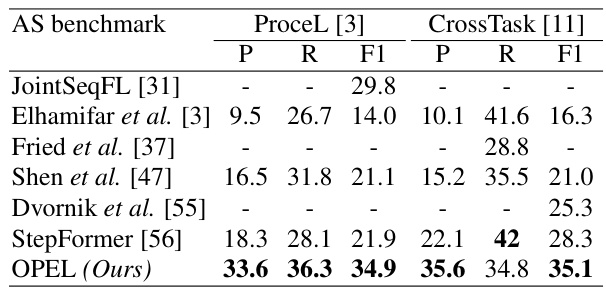

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed OPEL method against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on two benchmark datasets for procedure learning: ProceL and CrossTask. Both datasets involve third-person (exocentric) videos. The table shows the precision (P), recall (R), and F1-score (F1) for each method on both datasets. The results demonstrate that OPEL significantly outperforms the SOTA methods on both datasets.

This table compares the performance of OPEL against state-of-the-art (SOTA) multimodal models on various datasets. It highlights that OPEL, which only uses visual data, performs comparably to or better than these multimodal models (which use additional modalities such as gaze and depth information) in several benchmarks. This shows the effectiveness of OPEL’s visual-only approach.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed LOPEL framework against other state-of-the-art loss functions on four different datasets: CMU-MMAC, MECCANO, EGTEA-GAZE+, and PC Assembly. The results showcase the superior performance of LOPEL across multiple metrics (P, F1, IoU) demonstrating its efficacy in procedure learning. The different loss functions represent various approaches to handling temporal and semantic aspects of video data, highlighting the advantages of OPEL’s approach.

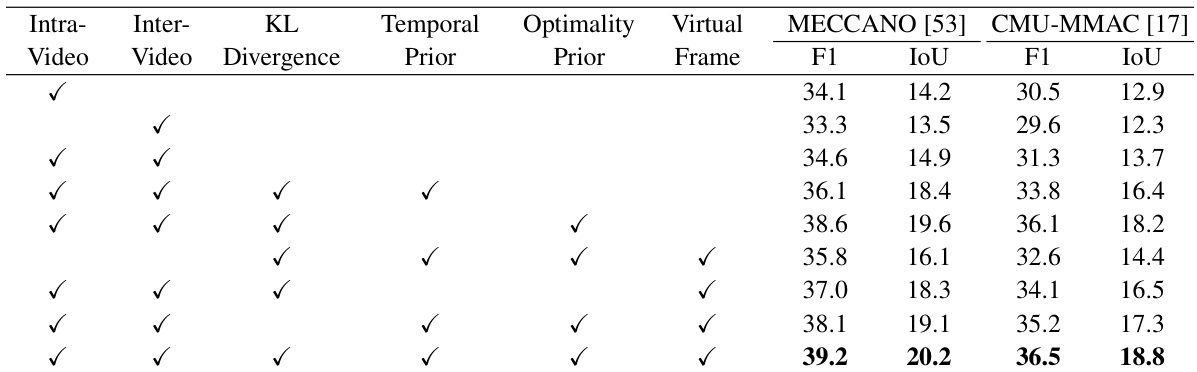

This table presents an ablation study analyzing the contribution of each component of the proposed LOPEL loss function. It shows the performance (F1 and IoU scores) on the MECCANO [53] and CMU-MMAC [17] datasets when different components (intra-video, inter-video contrastive loss, KL divergence, temporal prior, optimality prior, and virtual frame) are included or excluded. This helps to understand the relative importance of each component in improving the overall performance of the OPEL framework.

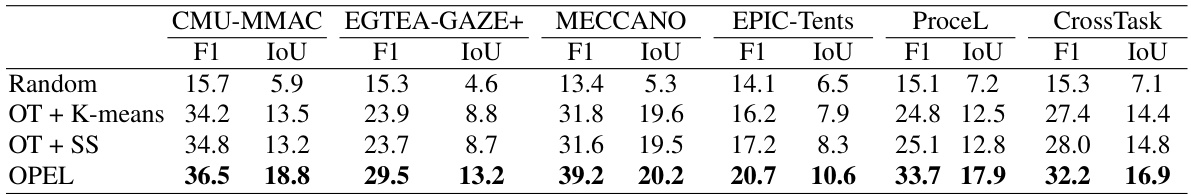

This table presents a comparison of the proposed OPEL framework’s performance against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the EgoProceL benchmark dataset for egocentric procedure learning. The metrics used for comparison are F1-score and Intersection over Union (IoU). The table highlights OPEL’s significant performance gains compared to the SOTA methods across various metrics, showcasing its effectiveness in handling egocentric videos.

This table presents the results of OPEL and baseline models with varying numbers of key-steps (k). The best results are obtained with k=7, and the performance decreases significantly as k deviates from 7. The results are consistent across all datasets. This observation is consistent with other SOTA methods on the same datasets [1, 2, 16]. It is hypothesized that k=7 is optimal because it represents the average number of distinct key-steps (subtasks) in the datasets.

This table compares the performance of OPEL against state-of-the-art unsupervised action segmentation (AS) models on the ProceL and CrossTask datasets. The table highlights that OPEL significantly outperforms existing AS methods in terms of precision (P), recall (R), and F1-score, demonstrating its superiority in handling the complexities of real-world video data and showcasing the benefits of its optimal transport approach. The ‘-’ indicates that some previous methods did not report results for all metrics.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed OPEL model’s performance against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the EgoProceL benchmark dataset for egocentric procedure learning. It shows the F1-score and Intersection over Union (IoU) metrics for each method across multiple datasets (CMU-MMAC, EGTEA-GAZE+, MECCANO, EPIC-Tents, PC Assembly, PC Disassembly). The results highlight OPEL’s significant improvement over the SOTA in both F1-score and IoU.

This table presents a statistical analysis of the EgoProceL dataset, breaking down the number of videos, key-steps, foreground ratio (proportion of video time dedicated to key-steps), missing key-steps, and repeated key-steps for each of the 16 tasks included in the dataset. The foreground ratio helps understand the amount of irrelevant background activity in each task. Missing key-steps and repeated key-steps are metrics indicating variations in the execution of tasks across videos.

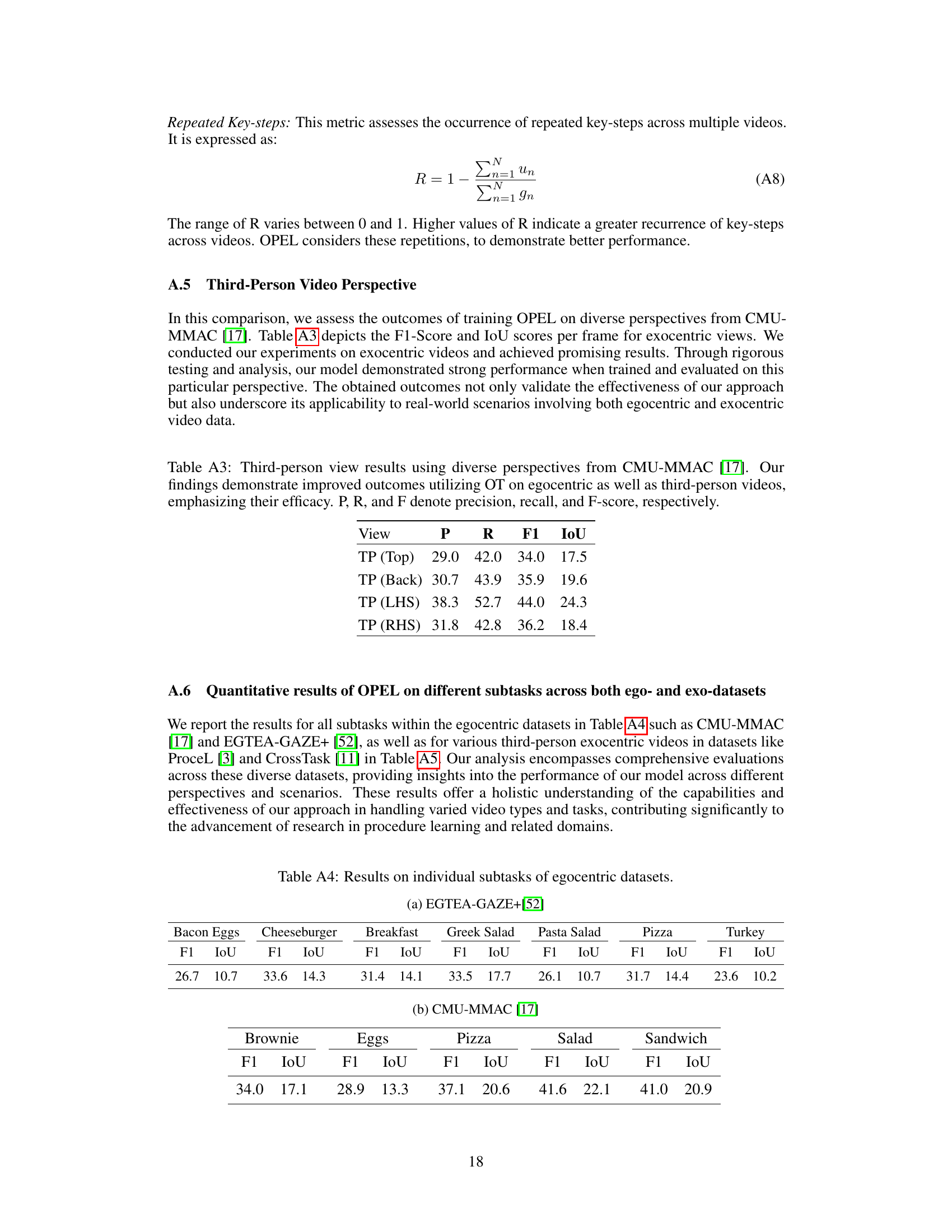

This table presents the results of the OPEL model applied to third-person videos from the CMU-MMAC dataset, offering a comparison of performance across different viewpoints (Top, Back, LHS, RHS). The metrics shown are Precision (P), Recall (R), F1-score (F1), and Intersection over Union (IoU), providing a comprehensive evaluation of OPEL’s effectiveness in handling various exocentric perspectives. This demonstrates OPEL’s generalization capabilities.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of the proposed OPEL model on individual subtasks within two egocentric datasets: EGTEA-GAZE+ and CMU-MMAC. It shows the F1-score and IoU for each subtask, allowing for a granular analysis of the model’s performance across various activities. This granular level of detail helps in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the model in different contexts.

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the OPEL model’s performance on individual subtasks within egocentric datasets. It shows the F1-score and IoU for each subtask across different egocentric datasets (EGTEA-GAZE+ and CMU-MMAC). This granular level of detail allows for a more nuanced understanding of the model’s strengths and weaknesses across various tasks and provides a more comprehensive evaluation than aggregate scores.

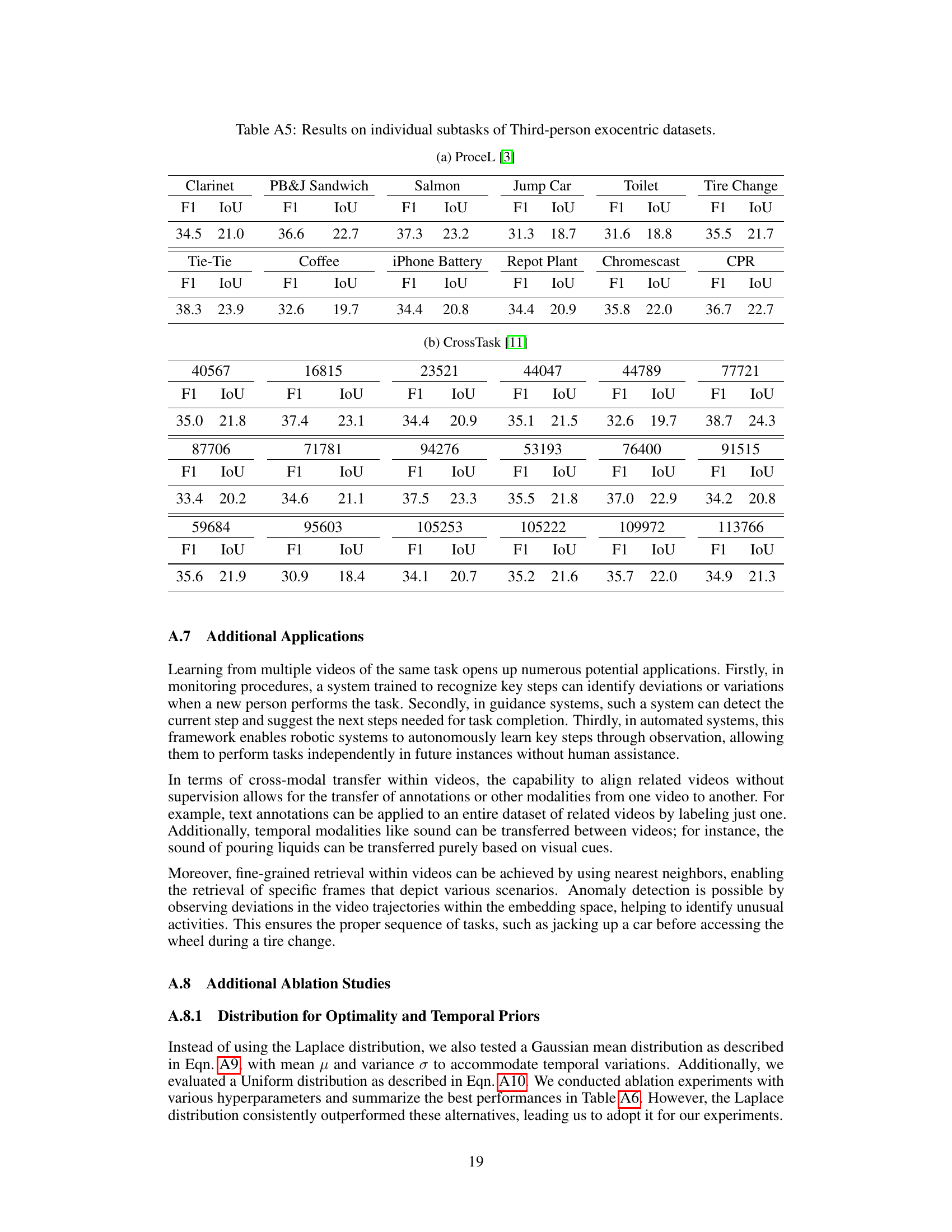

This table presents the performance of the proposed OPEL model and other state-of-the-art methods on individual subtasks within two third-person exocentric datasets: ProceL and CrossTask. The table shows the F1 score and IoU (Intersection over Union) for each subtask in each dataset, allowing for a granular comparison of model performance across different tasks and datasets.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed OPEL method against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches for procedure learning on the EgoProceL benchmark dataset. It shows the F1-score and IoU (Intersection over Union) achieved by each method for several different tasks. The superior performance of OPEL is highlighted.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of three different distribution functions (Uniform, Gaussian, and Laplace) used for the optimality and temporal priors in the OPEL framework. The results are shown for four different subtasks within the EgoProceL benchmark dataset: CMU-MMAC, MECCANO, PC Assembly, and PC Disassembly. Each subtask’s performance is evaluated using the F1 score and IoU metrics.

This table presents the ablation study on the impact of different values of hyperparameters λ₁ and λ₂ on the performance of the proposed OPEL model. It shows the F1-score and IoU for different values of these hyperparameters across four different datasets (CMU-MMAC, MECCANO, PC Assembly, and PC Disassembly) from the EgoProceL benchmark. The results illustrate the robustness of the model with respect to the choice of hyperparameters, indicating that the best performance is achieved with λ₁ = (N+M) and λ₂ = 0.1NM.

Full paper#