↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current visual object tracking algorithms struggle to match human performance, particularly in complex scenarios with spatio-temporal discontinuities. This is partly due to the limitations of existing benchmarks and the lack of human-like modeling in algorithms. This paper introduces CPDTrack, a novel visual tracking algorithm inspired by the Central-Peripheral Dichotomy (CPD) theory of human vision. CPDTrack uses a central vision module for precise localization and a peripheral vision module for global awareness, improving the tracker’s ability to handle complex scenes and maintain tracking over time. It also introduces the STDChallenge Benchmark, a new dataset designed to specifically assess trackers’ visual search abilities in scenarios with spatio-temporal discontinuities, including a human baseline for comparison.

CPDTrack significantly outperforms state-of-the-art trackers on the STDChallenge Benchmark and exhibits strong generalizability across other benchmarks. The results highlight the importance of human-like modeling in visual tracking and demonstrate that incorporating human-centered design principles can lead to more robust and efficient algorithms. The STDChallenge benchmark and human baseline provides a high-quality environment for evaluating trackers’ capabilities. The CPDTrack algorithm demonstrates the significant advantages of human-like modeling by closing the gap between machine and human performance in complex visual tracking tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses limitations in existing visual tracking algorithms by incorporating insights from human visual processing. The proposed CPDTrack model significantly improves tracking performance, especially in challenging scenarios with spatio-temporal discontinuities. It introduces a novel benchmark and evaluation method that fosters more human-centered design in the field. This work is highly relevant to current research trends in visual object tracking and cognitive neuroscience, potentially influencing the development of more robust and generalizable visual tracking systems. The approach paves the way for exploring human-like modeling strategies to further advance the field.

Visual Insights#

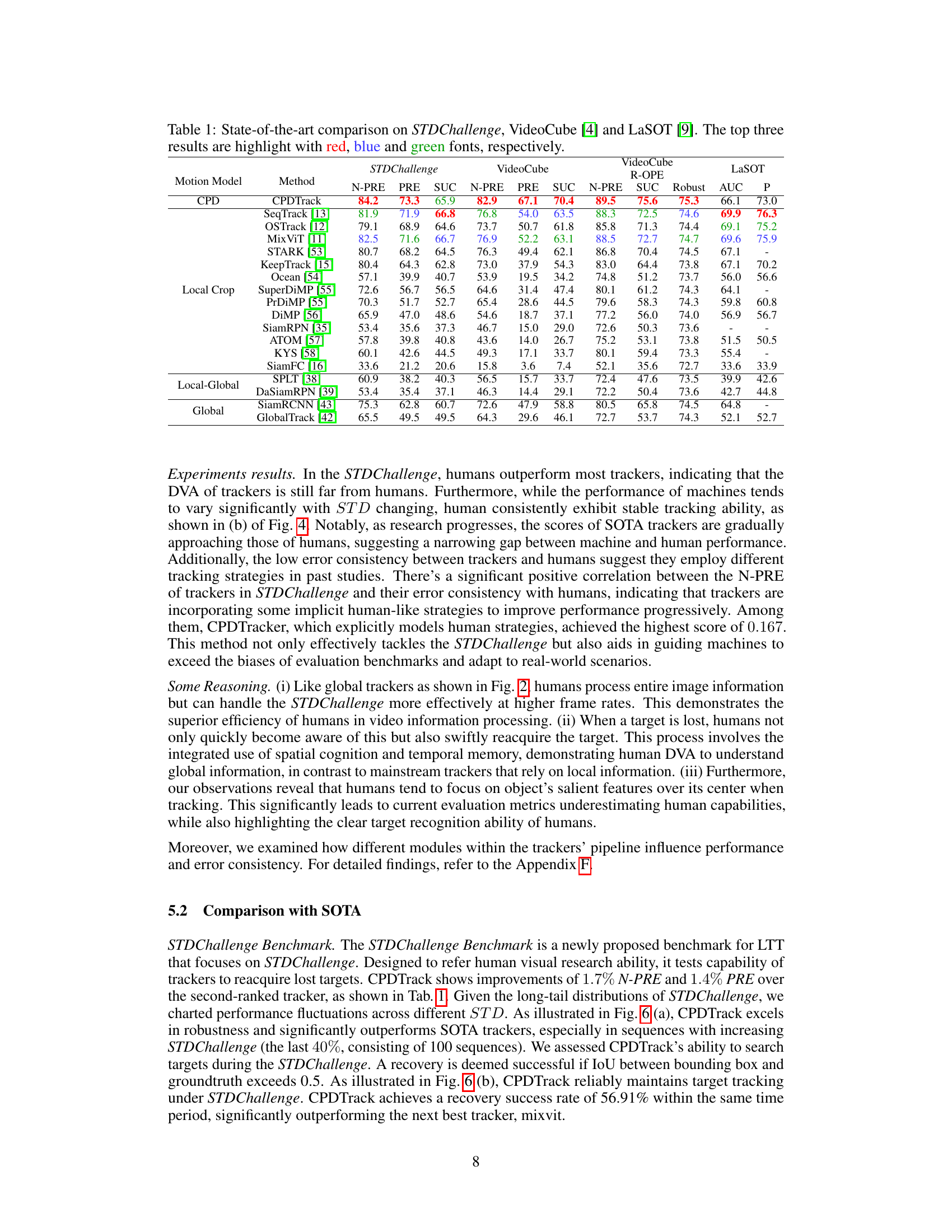

This figure illustrates the challenges of the STDChallenge benchmark for visual object trackers. The top row shows examples of video frames from the benchmark highlighting different scenarios, including instances where trackers fail (absent targets and abrupt changes or shotcut). The bottom row shows a graph plotting the tracker status (‘present’ or ‘absent’) over time for a specific sequence, highlighting the superiority of the proposed CPDTrack (in maintaining consistent tracking even under challenging conditions).

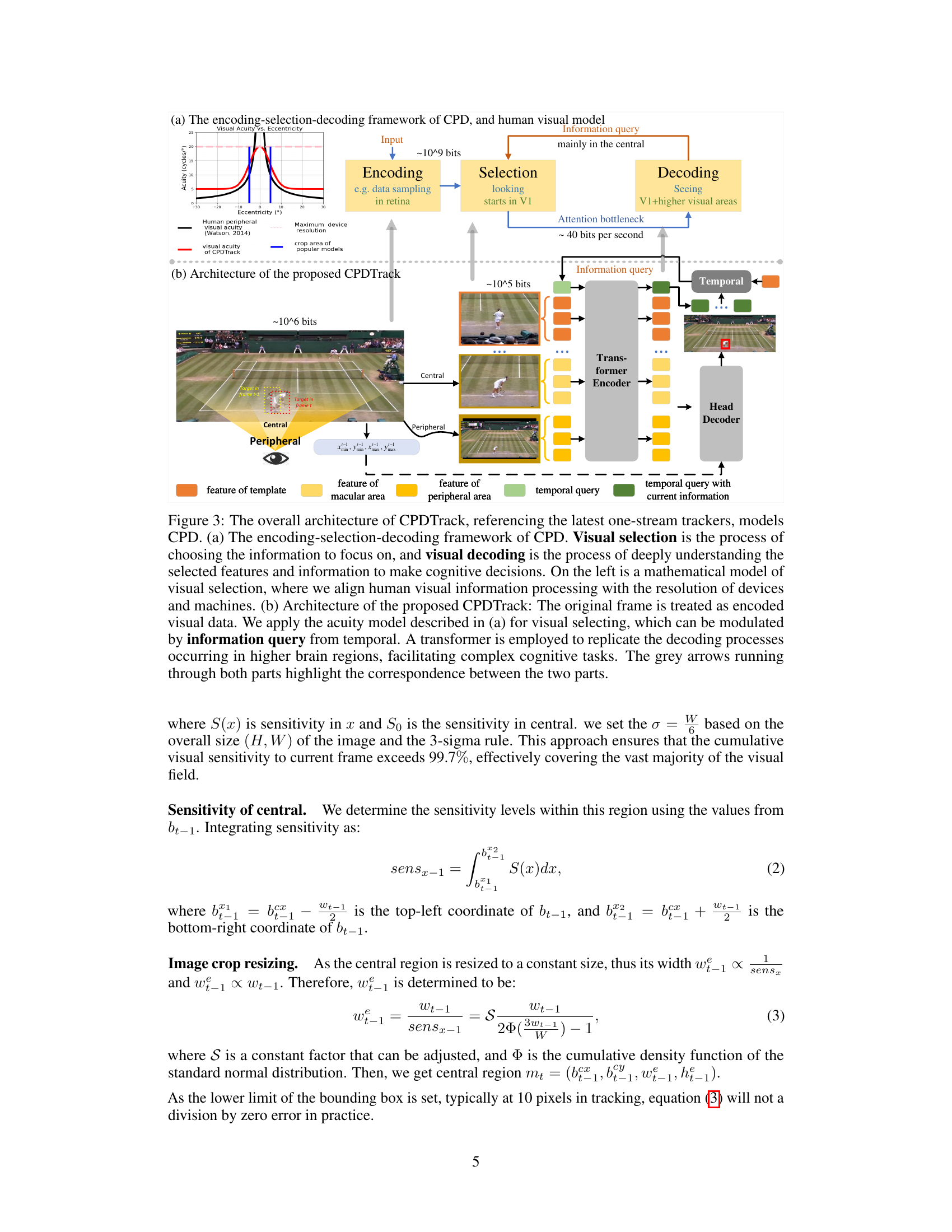

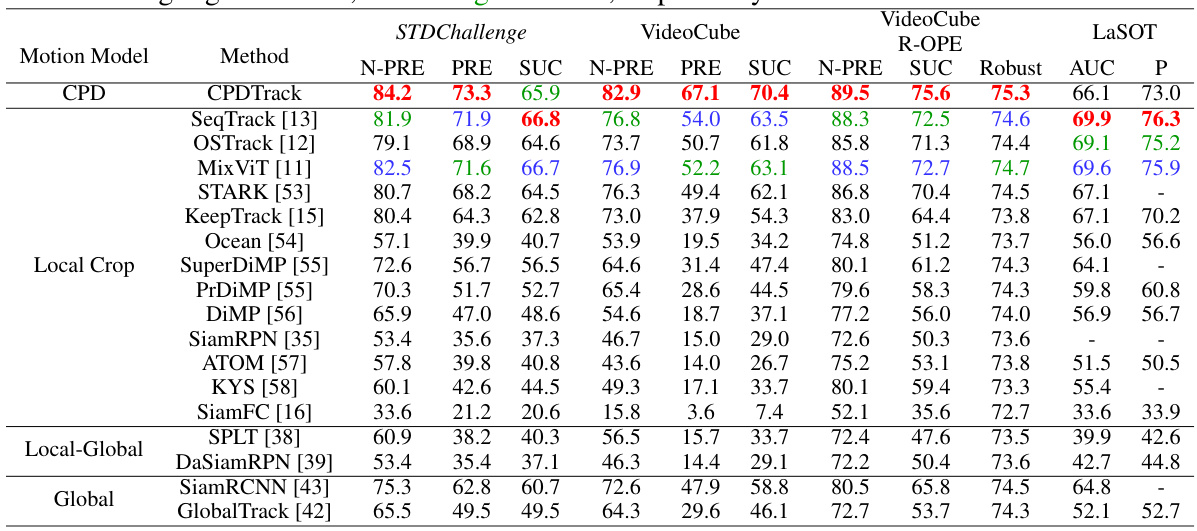

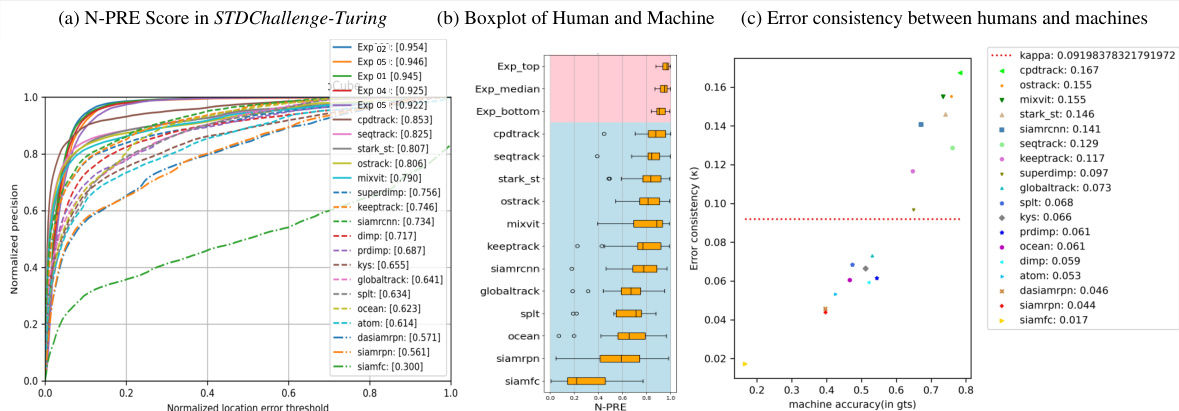

This table compares the performance of CPDTrack against other state-of-the-art (SOTA) trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. The table shows the N-PRE, PRE, SUC, and Robustness scores for each tracker on each benchmark. The top three performing trackers for each metric on each benchmark are highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively. This allows for a comprehensive comparison of CPDTrack’s performance against existing trackers across various tracking challenges.

In-depth insights#

Human-like Visual Search#

The concept of “Human-like Visual Search” in visual object tracking centers on designing algorithms that mimic human visual processing capabilities. Humans excel at tracking moving objects, even amidst complex backgrounds and temporary occlusions, due to their sophisticated visual search mechanisms. Central-Peripheral Dichotomy (CPD) is a key theory explaining human visual processing, highlighting the roles of central vision for detailed interpretation and peripheral vision for swift detection of changes. Algorithms aiming for human-like search should incorporate these aspects, such as using attention mechanisms mimicking foveal vision (high-resolution central processing) and incorporating a broader field of view to simulate the peripheral awareness of motion. Creating benchmarks that include challenging scenarios with spatio-temporal discontinuities is crucial, as standard benchmarks often underestimate human ability by focusing on simplified, continuous tracking tasks. Human-in-the-loop evaluations, comparing machine performance against human visual trackers, offer crucial insight into the success of the human-like modeling approach. Measuring error consistency further refines this comparison by evaluating behavioral similarity.

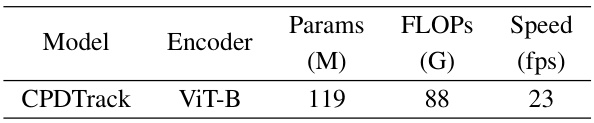

CPDTrack Algorithm#

The CPDTrack algorithm presents a novel approach to visual object tracking, drawing inspiration from the Central-Peripheral Dichotomy (CPD) theory of human vision. Its core innovation lies in mimicking the human visual system’s dual processing pathways: a central vision stream focusing on precise localization using spatio-temporal continuity, and a peripheral vision stream providing broader contextual awareness for robust object detection, especially when handling spatio-temporal discontinuities (STD). This dual-stream design allows CPDTrack to gracefully handle challenges like target absence and reappearance, which are common limitations of traditional single-stream trackers. The incorporation of an information query mechanism further enhances the algorithm’s performance, enabling a top-down control that dynamically adjusts the focus of attention. CPDTrack’s superior performance over existing trackers on STDChallenge Benchmark highlights its ability to address the limitations of existing methods, effectively bridging the gap between machine and human visual search abilities. However, further research is needed to assess its generalization to diverse datasets and scenarios beyond the benchmark while mitigating potential computational overhead.

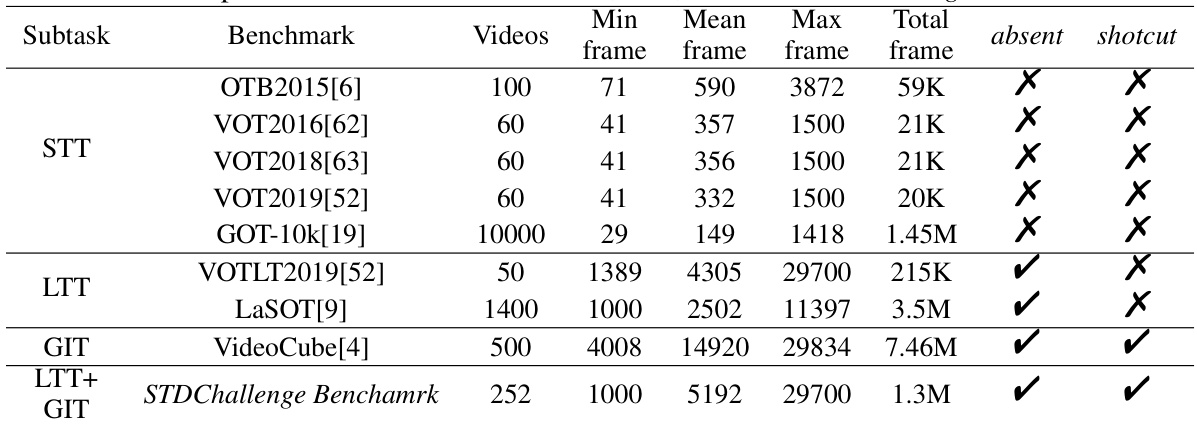

STDChallenge Benchmark#

The STDChallenge Benchmark is a novel contribution designed to evaluate visual tracking algorithms’ ability to handle spatio-temporal discontinuities (STDs). Unlike prior benchmarks that primarily focus on short-term, continuous tracking, STDChallenge incorporates scenarios with target absence, reappearance, and abrupt viewpoint shifts—challenges that more closely reflect real-world tracking scenarios. This is achieved by intelligently selecting sequences from established benchmarks like LaSOT, VOT, and VideoCube, creating a composite dataset that emphasizes the STD. The benchmark demonstrates the shortcomings of existing trackers that rely heavily on spatio-temporal continuity, underscoring the importance of robust visual search abilities for robust tracking. By incorporating human performance as a baseline, STDChallenge offers a rigorous and valuable tool for evaluating and comparing both human-like and machine-based trackers. The inclusion of human performance via the Visual Turing Test provides a direct comparison for algorithmic advancements, guiding future research toward more robust and human-like visual tracking systems.

Visual Turing Test#

The proposed ‘Visual Turing Test’ offers a novel approach to evaluating visual tracking algorithms by directly comparing their performance to that of humans. This is a significant departure from traditional benchmark-based evaluations, which often rely on proxy metrics that may not fully capture the complexities of human visual perception. The core idea is to create a benchmark where human and machine performance can be directly compared, using a methodology that more closely resembles human visual search strategies. This approach is crucial because it moves beyond simple accuracy metrics and considers factors like error consistency and the ability to recover from challenging situations (spatio-temporal discontinuities). The test focuses on scenarios that particularly challenge current trackers, such as those involving temporary target disappearance and changes in viewpoint or scene. By incorporating human subjects and analyzing their behavior, the researchers aim to establish a more robust and meaningful baseline for evaluating the intelligence of tracking algorithms. The results will not only provide an assessment of the current capabilities of machines but also offer insights into the areas where improvement is most needed to develop truly human-like visual tracking systems. The focus on human-like modeling suggests a shift from solely optimizing for accuracy to also emphasizing the qualitative aspects of visual perception.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending CPDTrack’s capabilities to handle even more challenging scenarios, such as those involving extreme occlusion, rapid viewpoint changes, or significant scale variations, is crucial for real-world applicability. Improving computational efficiency remains a key objective, potentially through model compression techniques or architectural modifications. Investigating the integration of additional sensory modalities, such as auditory or depth information, could enhance tracking robustness. Furthermore, exploring the application of the CPD framework to other visual tasks, like object detection and segmentation, would be highly valuable. A deeper investigation into the human visual search strategies that CPDTrack mimics is warranted, enabling the development of even more human-like and robust tracking algorithms. Finally, creating a more comprehensive and diverse benchmark that more accurately reflects real-world visual complexity is necessary to ensure reliable and generalizable evaluation of tracking methods. Addressing these avenues for future research would significantly advance the field of visual object tracking.

More visual insights#

More on figures

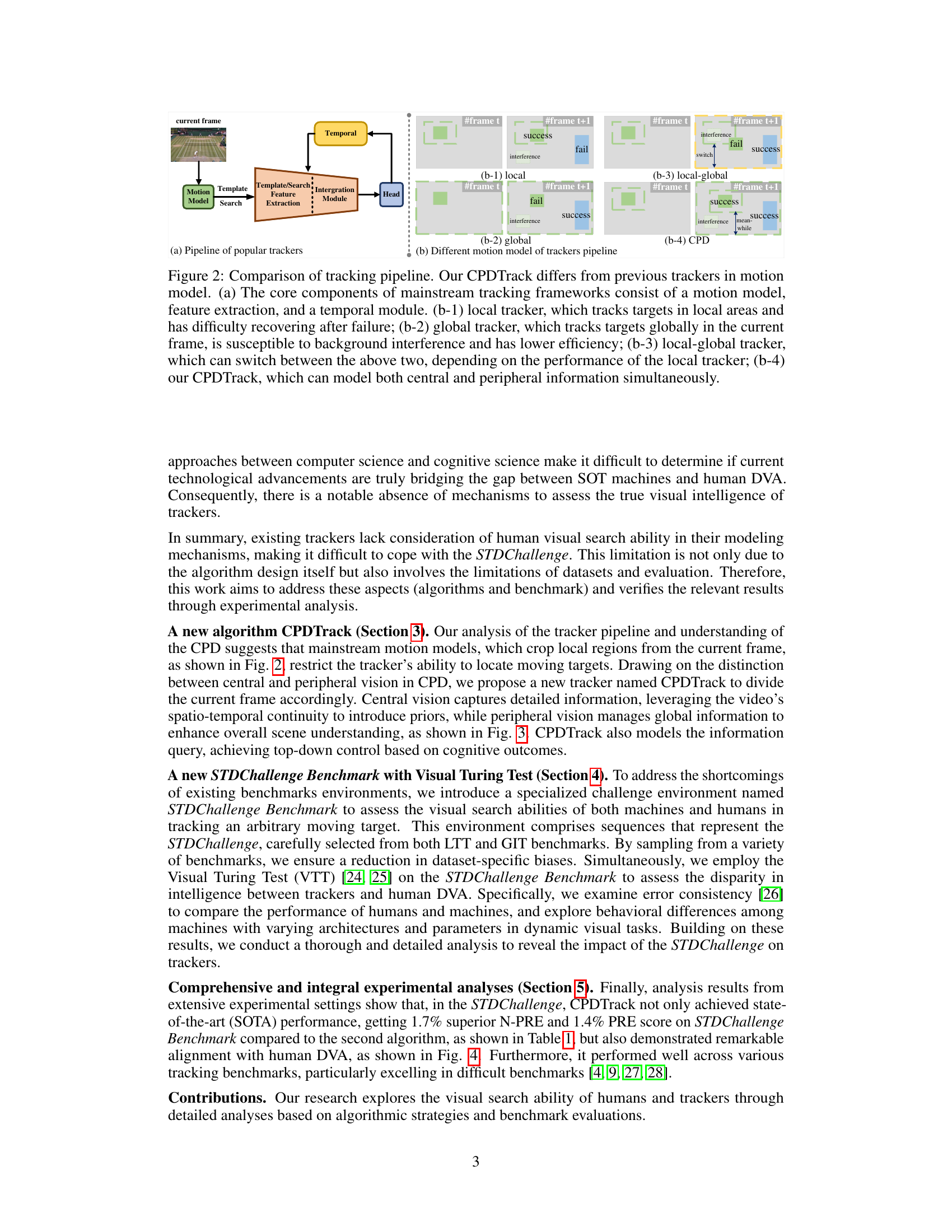

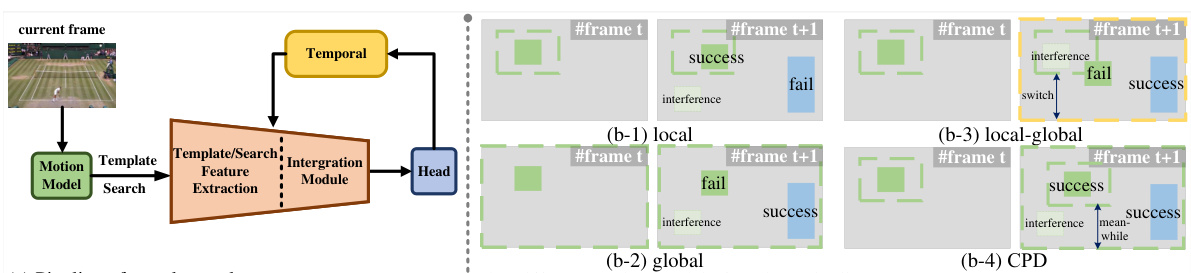

This figure compares different tracking pipeline architectures, highlighting the differences in motion models. It shows that mainstream trackers typically use either a local approach (tracking only a small area around the target), a global approach (tracking the entire image), or a hybrid approach that switches between these two. The authors’ proposed CPDTrack is presented as a superior alternative that combines central and peripheral vision for improved robustness and efficiency.

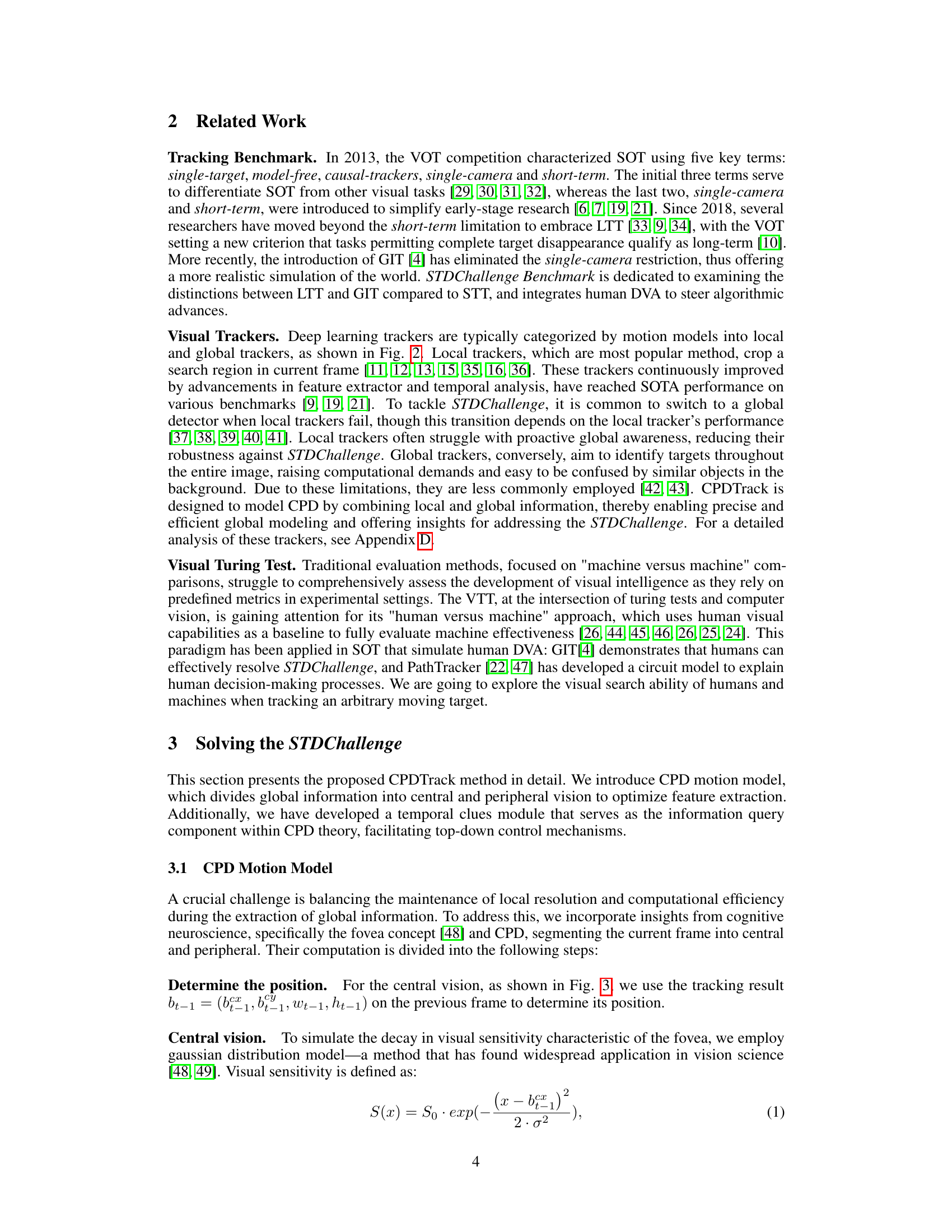

This figure illustrates the architecture of CPDTrack, a new tracker inspired by the Central-Peripheral Dichotomy (CPD) theory of human vision. The (a) part shows the encoding, selection, and decoding framework of CPD, highlighting how human vision processes information. The (b) part details the CPDTrack architecture, dividing the input frame into central and peripheral vision. Central vision uses spatio-temporal information for precise localization, while peripheral vision enhances global awareness. A transformer processes this information, mimicking higher-level cognitive functions.

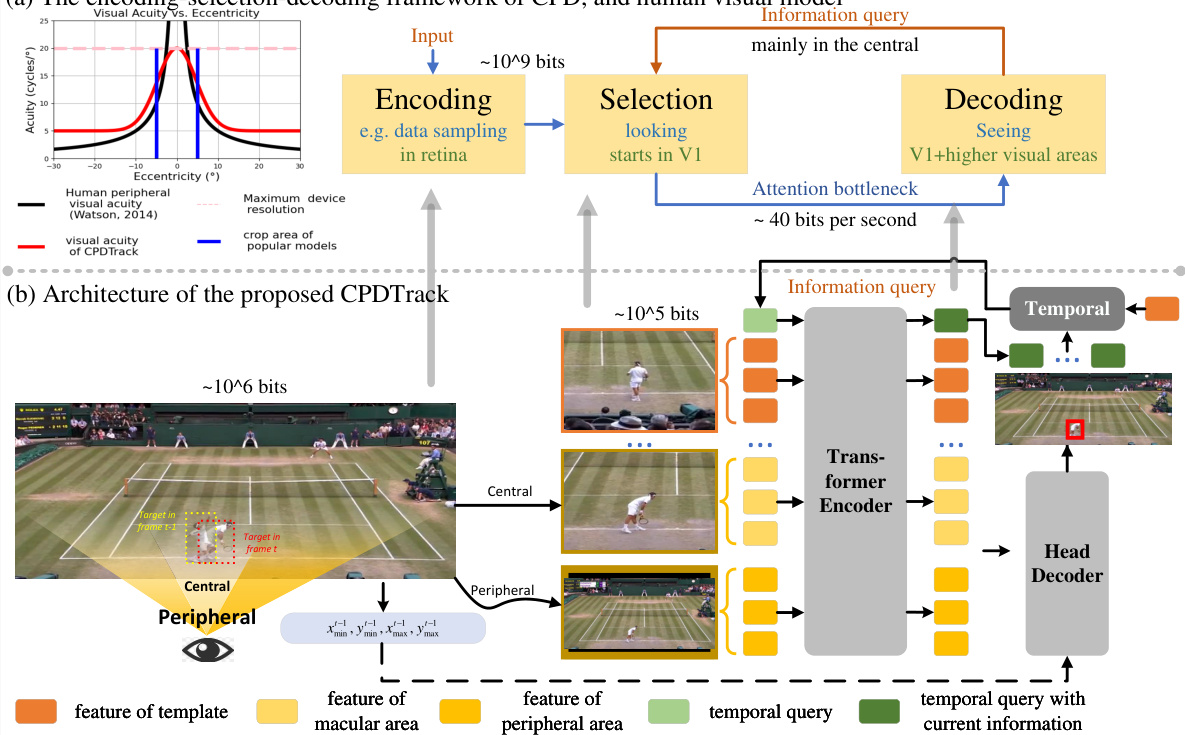

This figure presents a quantitative comparison of CPDTrack’s performance against other trackers and humans in the STDChallenge-Turing benchmark. It uses three key metrics: (a) the N-PRE score (Normalized Precision), showing CPDTrack’s superior performance; (b) boxplots illustrating the distribution of N-PRE scores across various sequences, highlighting CPDTrack’s consistent performance and greater similarity to human performance; and (c) a scatter plot showcasing the error consistency (kappa coefficient) between different trackers and humans, further demonstrating CPDTrack’s closer alignment with human visual search behavior.

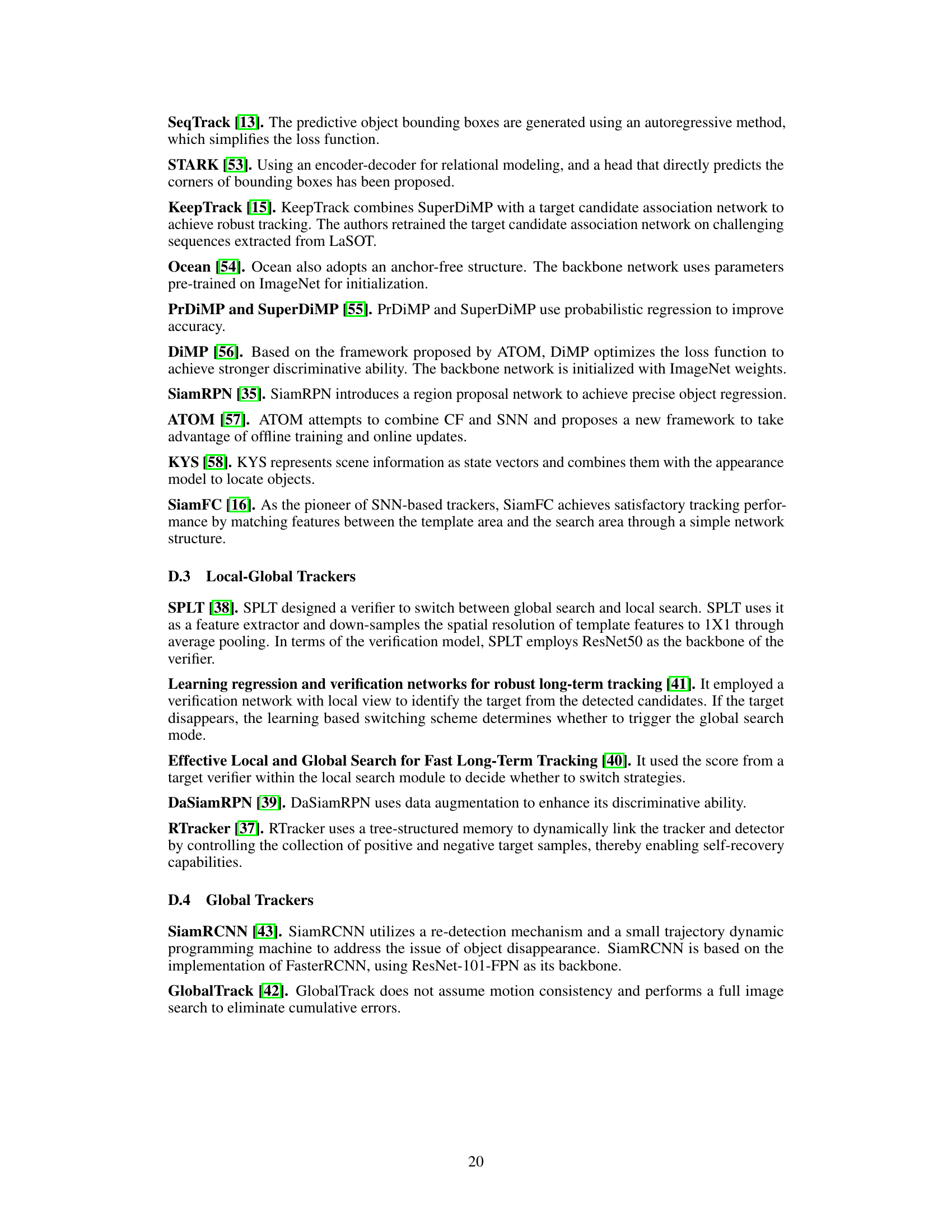

This figure shows example results from humans and several trackers on the STDChallenge sequences. The top row demonstrates that even when the target is temporarily absent (indicated by ‘absent’) or there’s a shotcut (indicated by ‘shotcut’), humans are able to successfully re-identify and track the target based on contextual understanding. They can leverage environmental cues to track the target even after loss or shotcut. The bottom row highlights the robustness of human visual tracking in the face of occlusions; humans can successfully locate the target even when it is partially obscured. The figure contrasts the human’s performance to that of several state-of-the-art trackers, which show a higher failure rate in these challenging scenarios.

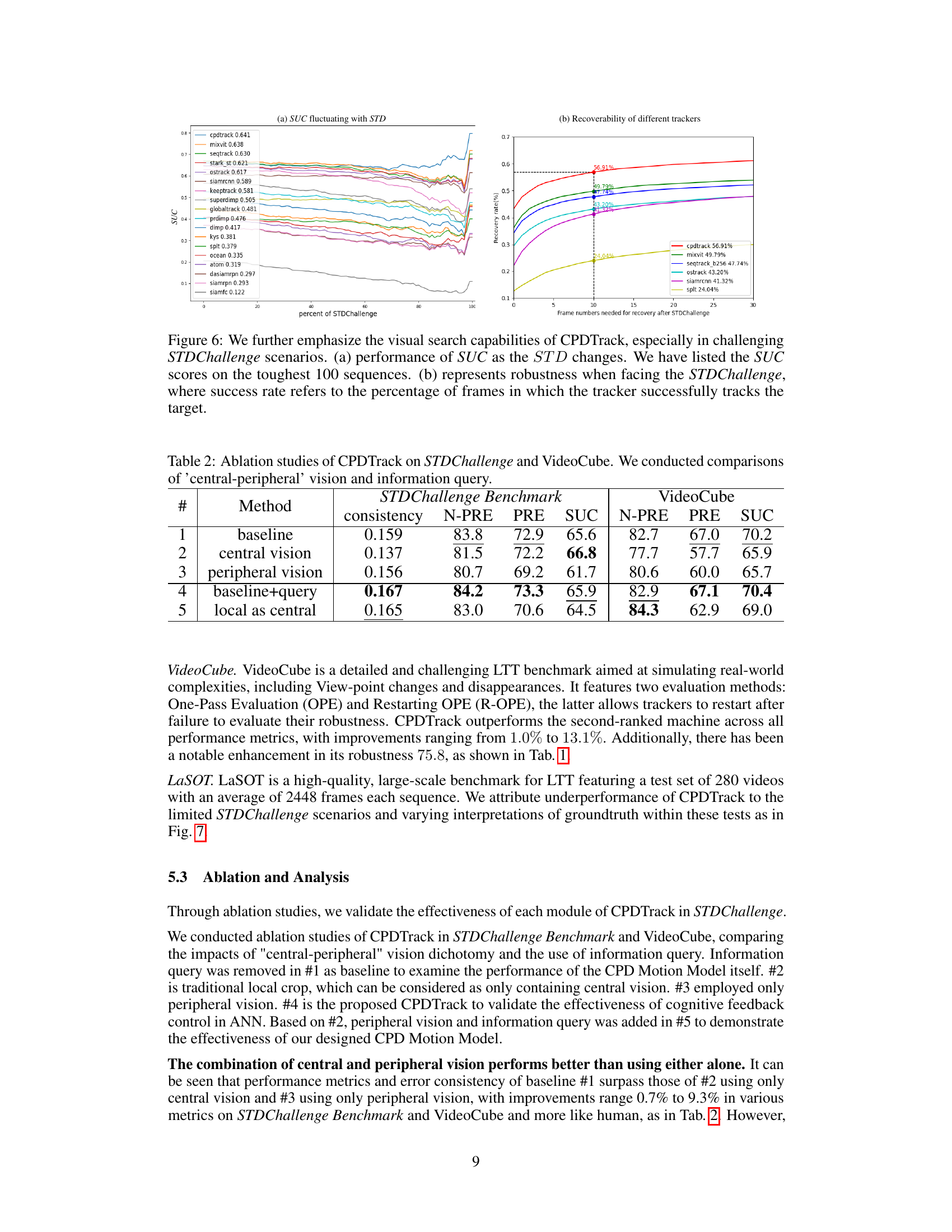

This figure shows two graphs that evaluate the performance of CPDTrack and other trackers under the STDChallenge. The first graph (a) displays the SUC (Success rate) fluctuating with the STD (Spatio-temporal Discontinuity) across various challenging sequences. It illustrates the robustness of CPDTrack compared to other methods, especially in highly challenging scenarios with high STD values. The second graph (b) shows the recovery rate (percentage of frames where successful tracking was maintained after a STDChallenge) over the frame numbers needed to recover. It showcases the swift recovery ability of CPDTrack in comparison to other trackers.

This figure shows the tracking results of CPDTrack and three other trackers (OSTrack, SeqTrack, MixViT) on two video sequences: one featuring a lion and another a helicopter. The results highlight CPDTrack’s tendency to encompass the entire target object within the bounding box, even parts that might be considered secondary or peripheral to the main body of the object (e.g., lion’s tail or helicopter rotor). The paper argues this is not a failure, but rather a reflection of CPDTrack’s incorporation of global context and a more human-like visual search strategy, as opposed to the more focused local approach of other trackers. The difference in bounding boxes illustrates the distinctions in these approaches.

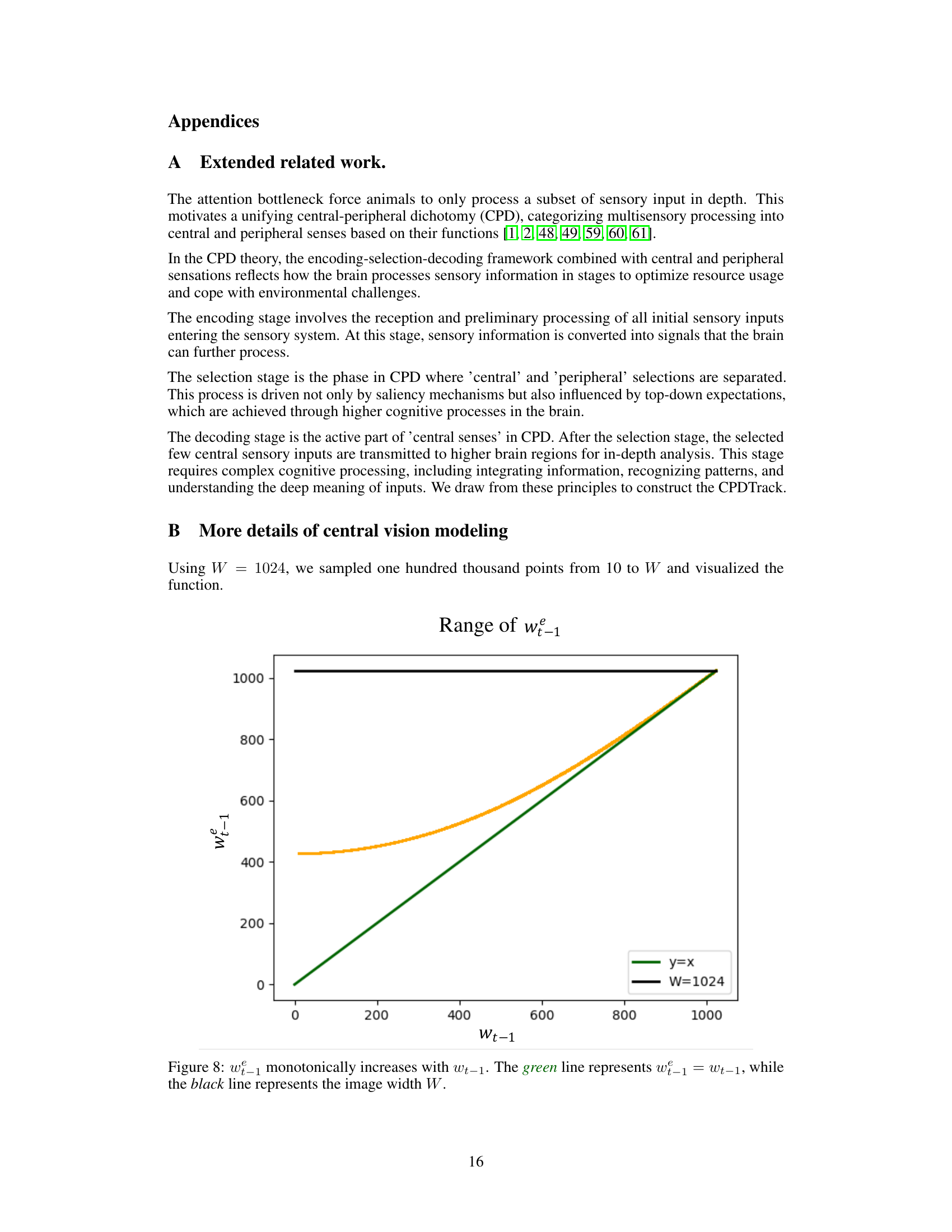

This figure shows the relationship between wt-1 (the width of the central region in the previous frame) and wt-1 (the width of the central region in the current frame) for the CPDTrack algorithm. The graph shows that wt-1 increases monotonically with wt-1, meaning that the width of the central region in the current frame is always greater than or equal to the width of the central region in the previous frame. The green line represents a linear relationship where the width of the central region in the current frame is equal to the width of the central region in the previous frame. The black line represents a horizontal line where the width of the central region is equal to the total image width (W = 1024). The orange line shows the actual calculated value of wt-1 using the Gaussian model in the paper, which represents the calculated width of the central region after taking visual sensitivity into account. The function of the orange line shows that the central region’s size is adjusted based on its sensitivity which is calculated based on the previous frame’s tracking result. This demonstrates that the CPDTrack algorithm adaptively adjusts the size of the central region based on the visual sensitivity.

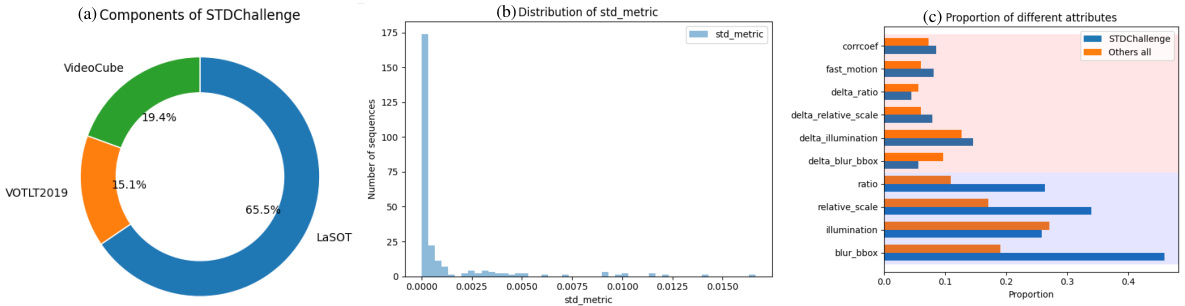

This figure illustrates the composition and characteristics of the STDChallenge benchmark dataset. Panel (a) shows a donut chart breaking down the proportion of sequences sourced from three different benchmark datasets: LaSOT, VOTLT2019, and VideoCube. Panel (b) is a histogram displaying the distribution of the STD metric across all sequences in the benchmark. Finally, Panel (c) presents a bar chart comparing the proportion of different attributes (e.g., ‘corrcoef’, ‘fast motion’, etc.) found in STDChallenge sequences versus those found in sequences from other datasets. The long tail in the STD metric distribution highlights the challenge the benchmark presents, showing that many sequences contain fewer challenges while a smaller number contain a higher number of challenges.

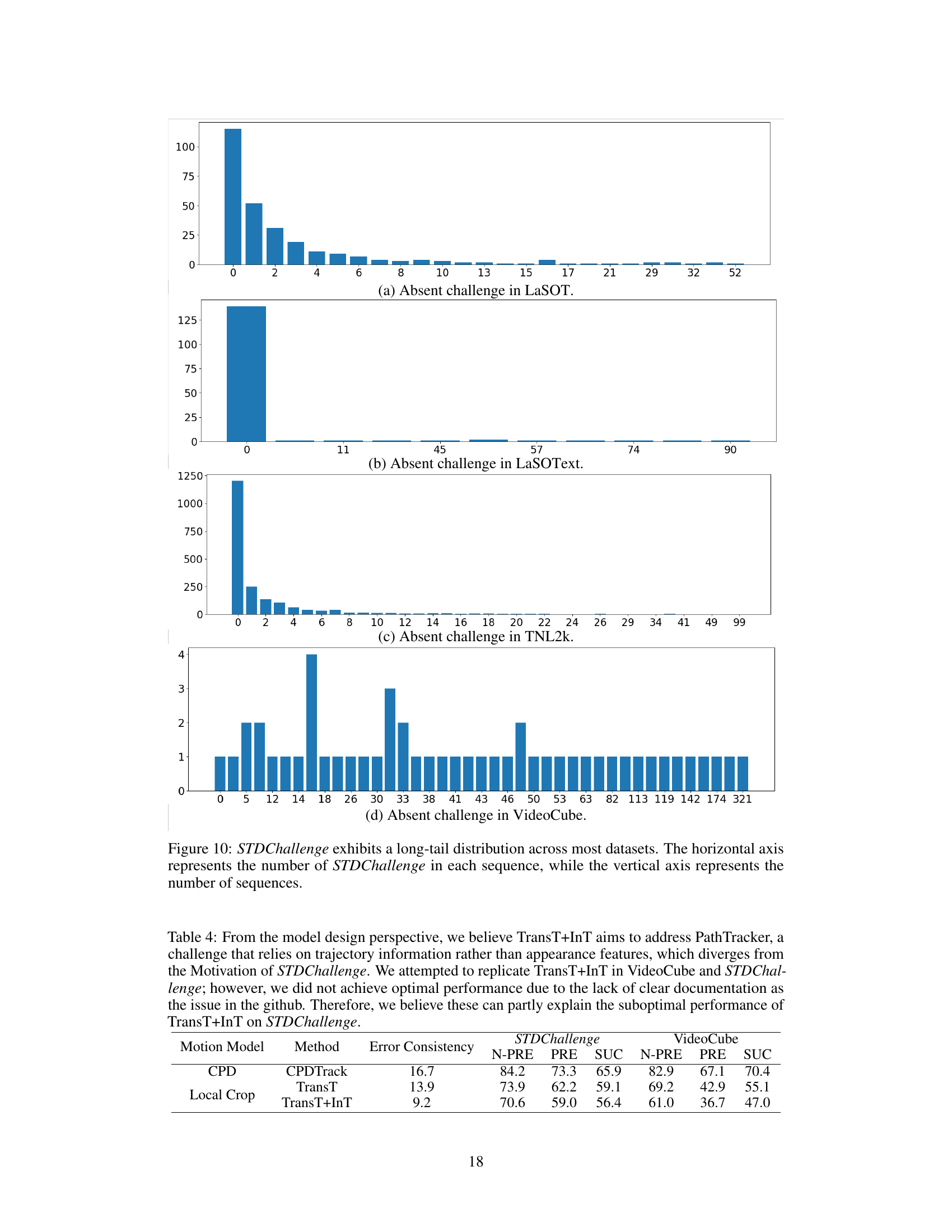

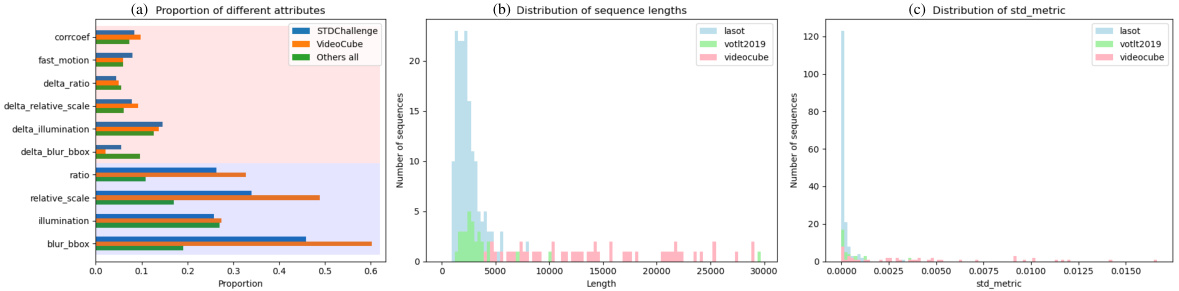

This figure shows the distribution of the number of STDChallenge (spatio-temporal discontinuity) events within each sequence across four different datasets used in the STDChallenge benchmark. The long tail indicates that many sequences contain few STDChallenge events, while a smaller number have a very large number. This highlights the challenge of ensuring adequate representation of real-world scenarios with high variability in the number of such events during dataset creation and highlights the non-uniform distribution of challenges in existing benchmarks.

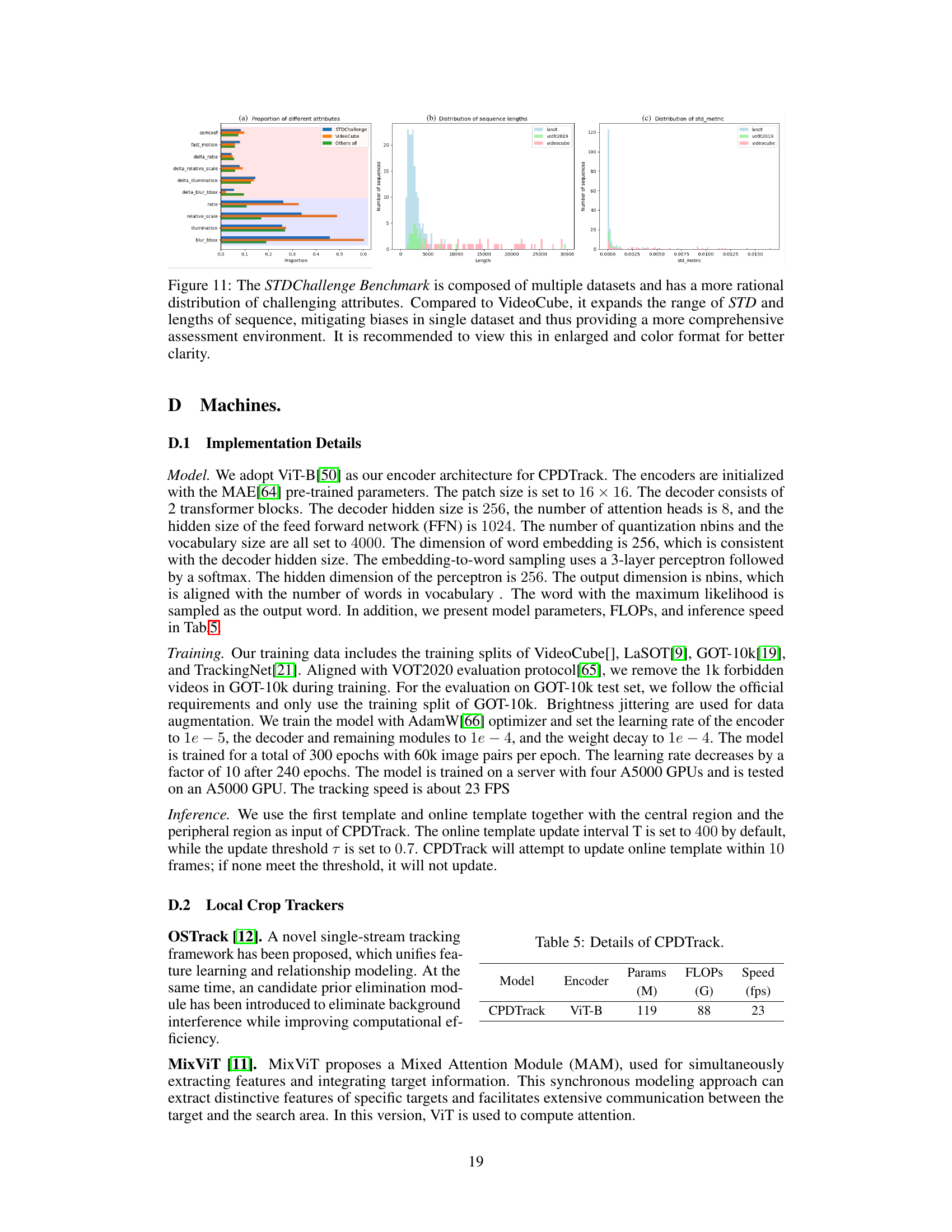

This figure shows a comparison of the STDChallenge Benchmark with other benchmarks, highlighting its improved distribution of challenging attributes and sequence lengths. It aims to address biases found in single-dataset benchmarks by incorporating data from multiple sources, creating a more realistic and comprehensive evaluation environment.

This figure shows example video sequences used in a visual Turing test to evaluate human performance on a visual tracking task. The sequences are from the STDChallenge benchmark and are categorized by difficulty: low, medium, and high. The difficulty is determined by factors like the frequency of the target disappearing (absent), the frequency of video cuts (shotcut), and the amount of scene changes. This helps demonstrate the range of challenges within the benchmark and how they compare to human ability.

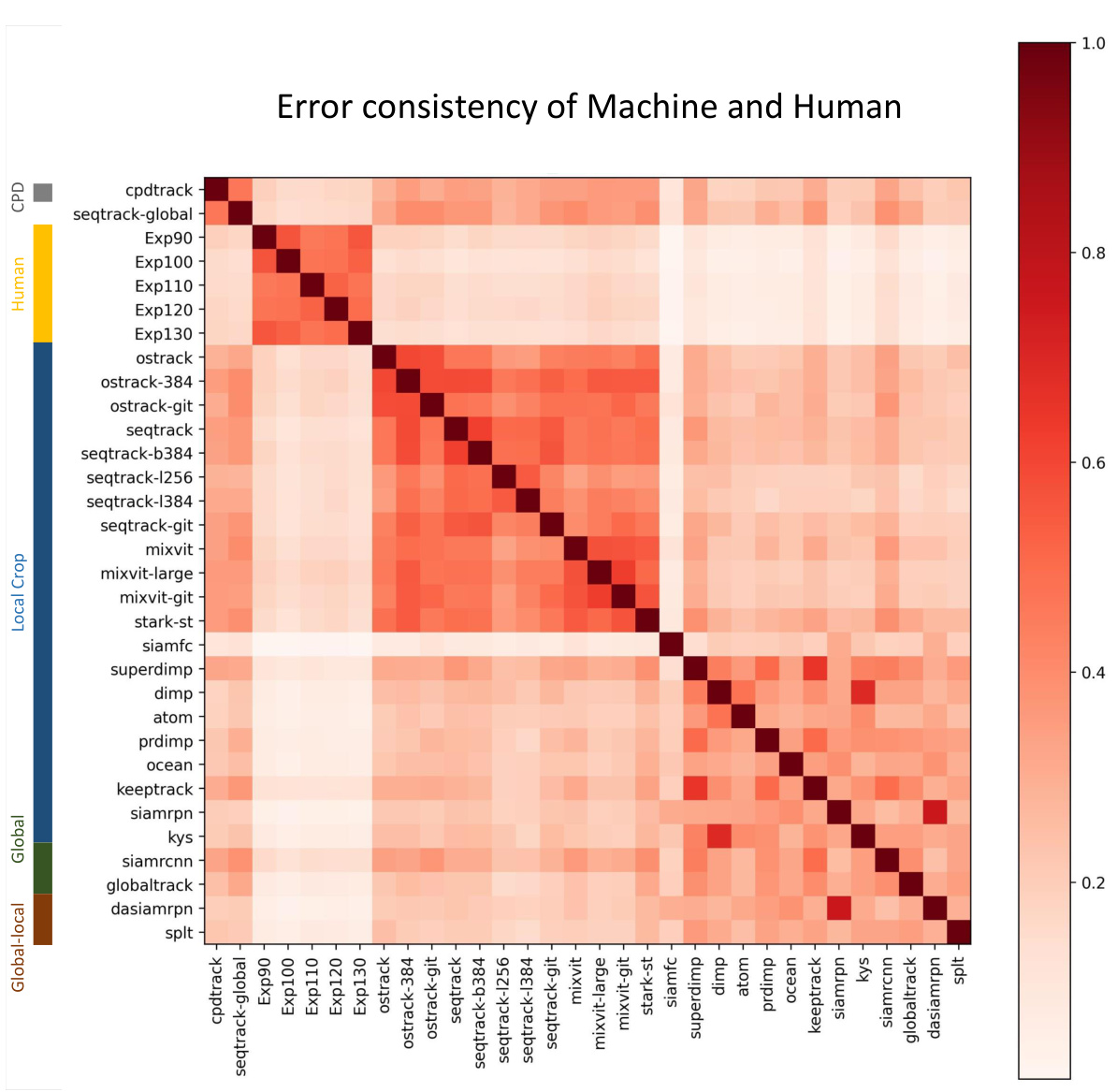

This heatmap visualizes the error consistency between human and machine trackers across various sequences in the STDChallenge-Turing benchmark. The color intensity represents the degree of similarity in error patterns, with darker colors indicating higher similarity. The figure helps assess how closely different tracking algorithms mimic human behavior in challenging scenarios characterized by spatio-temporal discontinuities.

This figure presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of different modules and settings on tracker performance. It includes subfigures demonstrating effects of the temporal module, architecture (customized, SNN+CF-SNN, one-stream), motion model (local crop, local-global, global, CPD), contextual ratio, model parameters (AlexNet, ResNet18, ResNet50, ViT-base, ViT-large), and training datasets (GOT-10k only, GOT-10k+COCO, GOT-10k+COCO+TrackingNet, GOT-10k+COCO+TrackingNet+LaSOT, GOT-10k+COCO+TrackingNet+LaSOT+VideoCube). Each subfigure displays the normalized precision score and error consistency, showing how changing these factors affects both tracking accuracy and the consistency of results compared to human performance.

More on tables

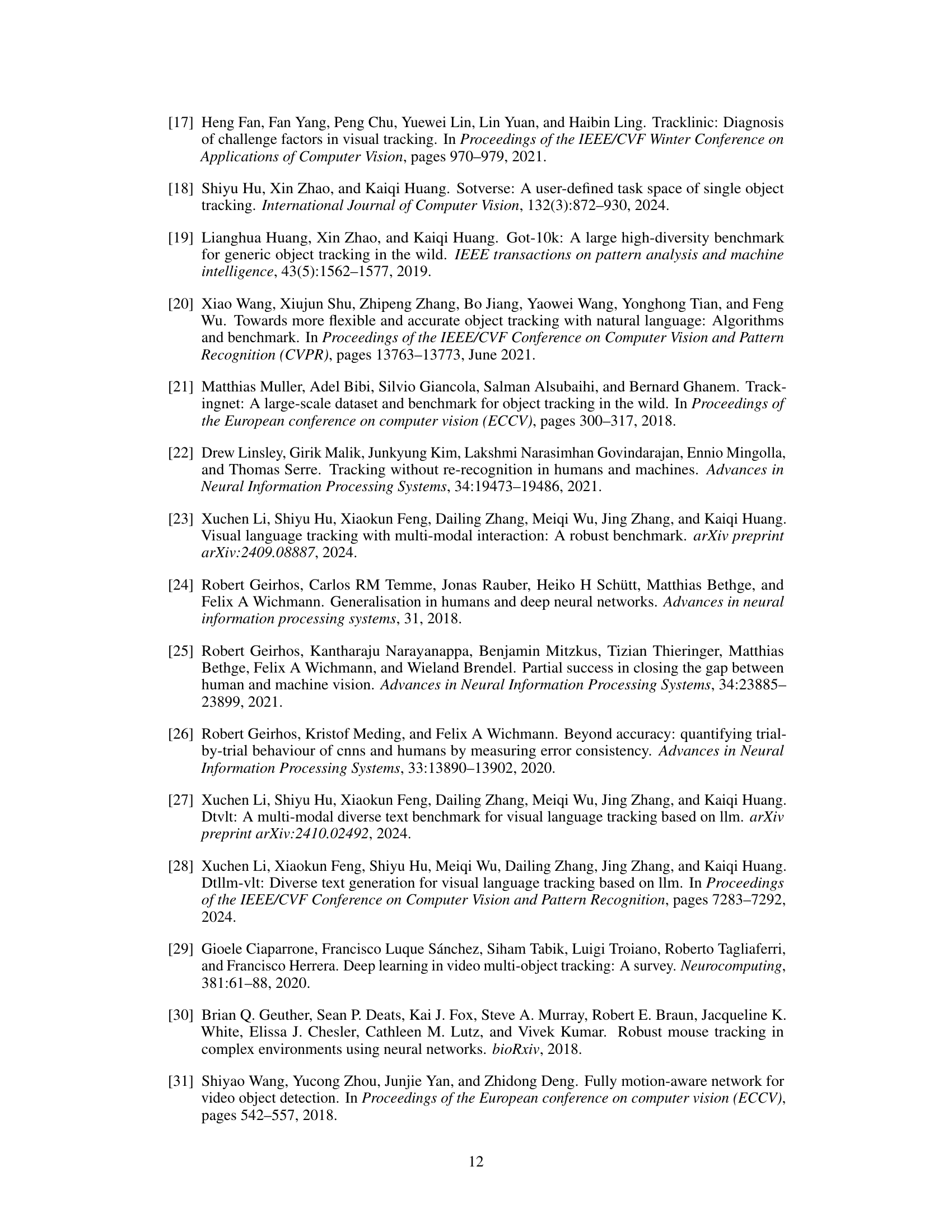

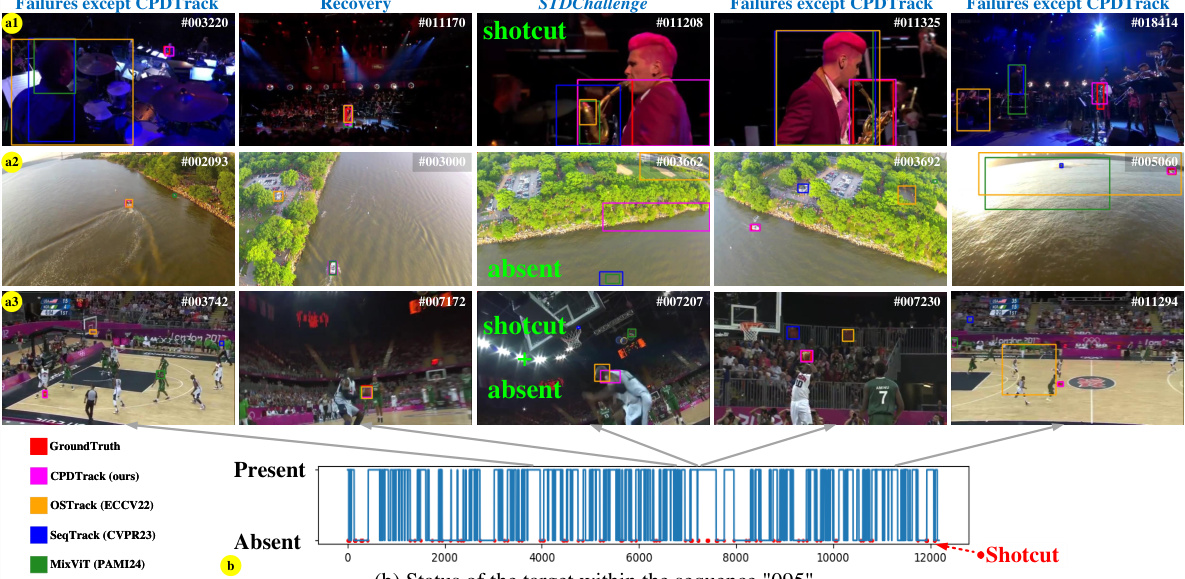

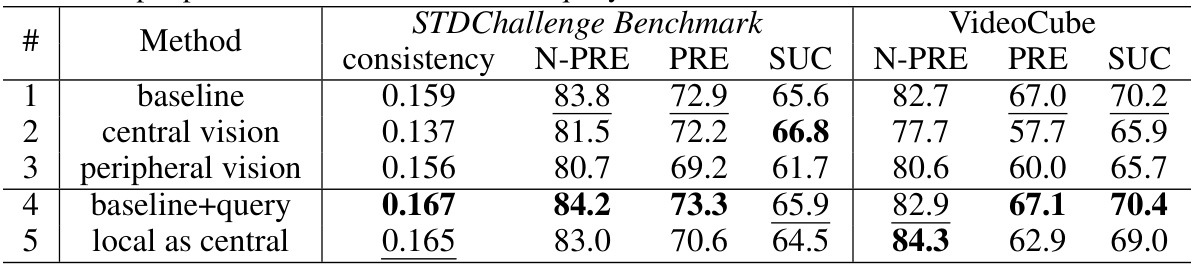

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted on the CPDTrack model using two benchmarks: STDChallenge and VideoCube. The goal was to evaluate the effectiveness of different components of the model, specifically the central and peripheral vision modules and the information query mechanism. The table shows the error consistency, and the performance metrics N-PRE, PRE, and SUC across various configurations. The ‘baseline’ row represents the full CPDTrack model. Subsequent rows show results when either central vision, peripheral vision, or the query mechanism is removed or modified. The final row explores using a local cropping method as an alternative to the central vision module.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed CPDTrack model’s performance against other state-of-the-art (SOTA) trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. The table shows the performance metrics (N-PRE, PRE, SUC, Robustness, AUC, P) for each tracker on each benchmark. The top three performing trackers are highlighted for each metric on each benchmark.

This table compares the performance of CPDTrack against other state-of-the-art trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. The metrics used for comparison are N-PRE, PRE, and SUC. The top three performing trackers for each benchmark are highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively, to show the relative performance of CPDTrack.

This table compares the performance of CPDTrack against other state-of-the-art trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. The metrics used for comparison include N-PRE, PRE, SUC, and AUC. The top three performing trackers for each benchmark are highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively. This allows for a direct comparison of CPDTrack’s performance against existing methods on various challenging tracking tasks.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed CPDTrack model with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. The table shows the performance of each tracker in terms of several metrics (N-PRE, PRE, SUC, Robustness, AUC, P). The top three performing trackers for each metric on each benchmark are highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively. This allows for a direct comparison of CPDTrack’s performance against existing methods across various tracking challenges.

This table compares the performance of CPDTrack against other state-of-the-art trackers on three different benchmarks: STDChallenge, VideoCube, and LaSOT. For each benchmark, it shows the performance metrics (N-PRE, PRE, SUC, and AUC) achieved by each tracker. The top three performing trackers for each metric are highlighted in red, blue, and green. The table provides a quantitative comparison of CPDTrack’s performance in relation to existing techniques across various tracking scenarios.

Full paper#