TL;DR#

MaxEnt RL methods for continuous action spaces typically use actor-critic frameworks, which involves separate policy evaluation and policy improvement steps. Estimating the soft Q-function, essential in MaxEnt RL, often requires computationally expensive Monte Carlo approximations, leading to inefficiencies and approximation errors. These limitations motivate the search for more efficient and accurate approaches.

This paper introduces MEow, a new MaxEnt RL framework that addresses these issues. MEow uses energy-based normalizing flows (EBFlow) to unify policy evaluation and improvement. This unified approach allows for the exact calculation of the soft value function, eliminating the need for computationally expensive Monte Carlo methods. The proposed framework also supports multi-modal action distributions and enables efficient action sampling, improving both accuracy and efficiency. Experiments demonstrate that MEow outperforms existing baselines on MuJoCo and Omniverse Isaac Gym benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel MaxEnt RL framework, MEow, that significantly improves upon existing methods by offering a unified training process and enabling the exact calculation of the soft value function, thus leading to superior performance in various robotic tasks. It also introduces innovative training techniques and opens avenues for future research in MaxEnt RL.

Visual Insights#

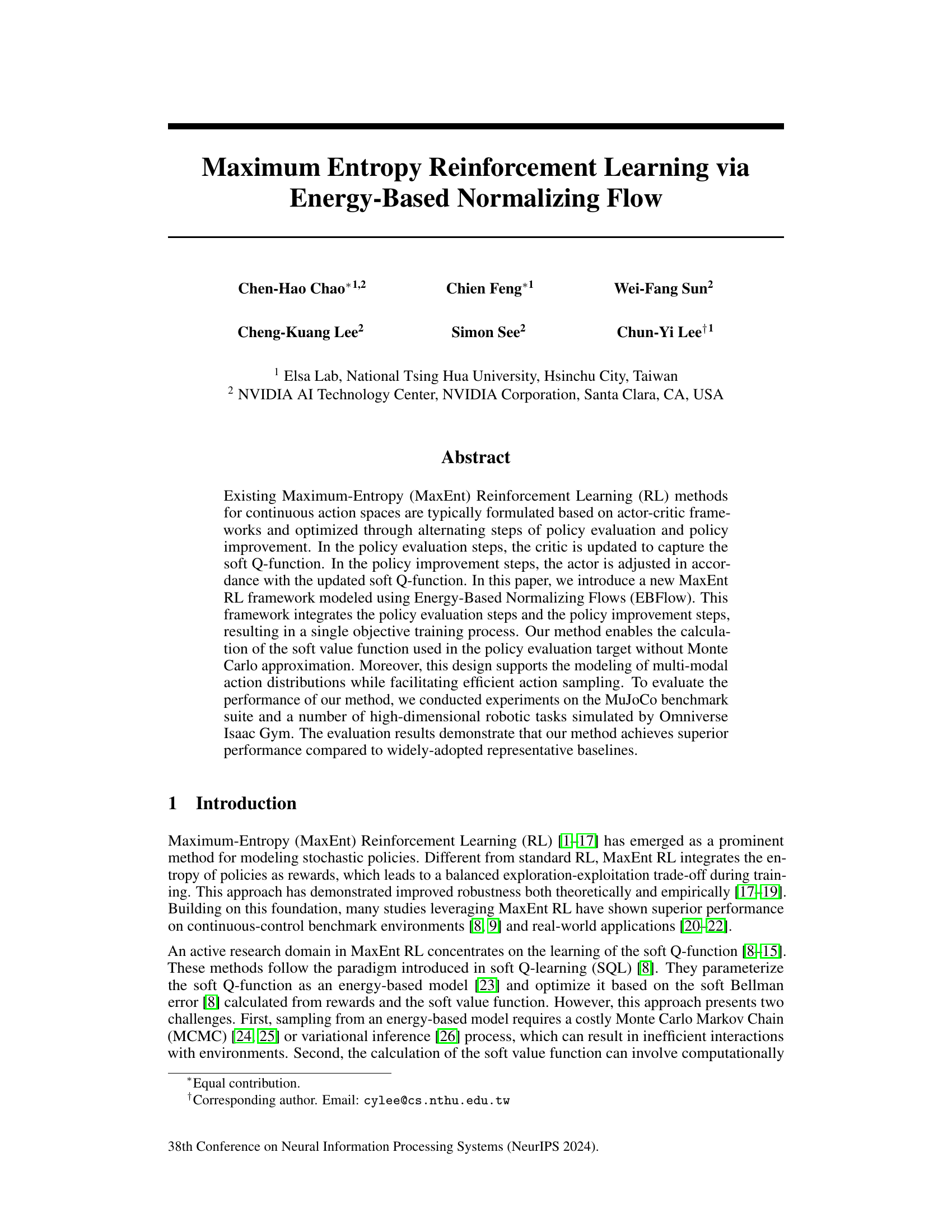

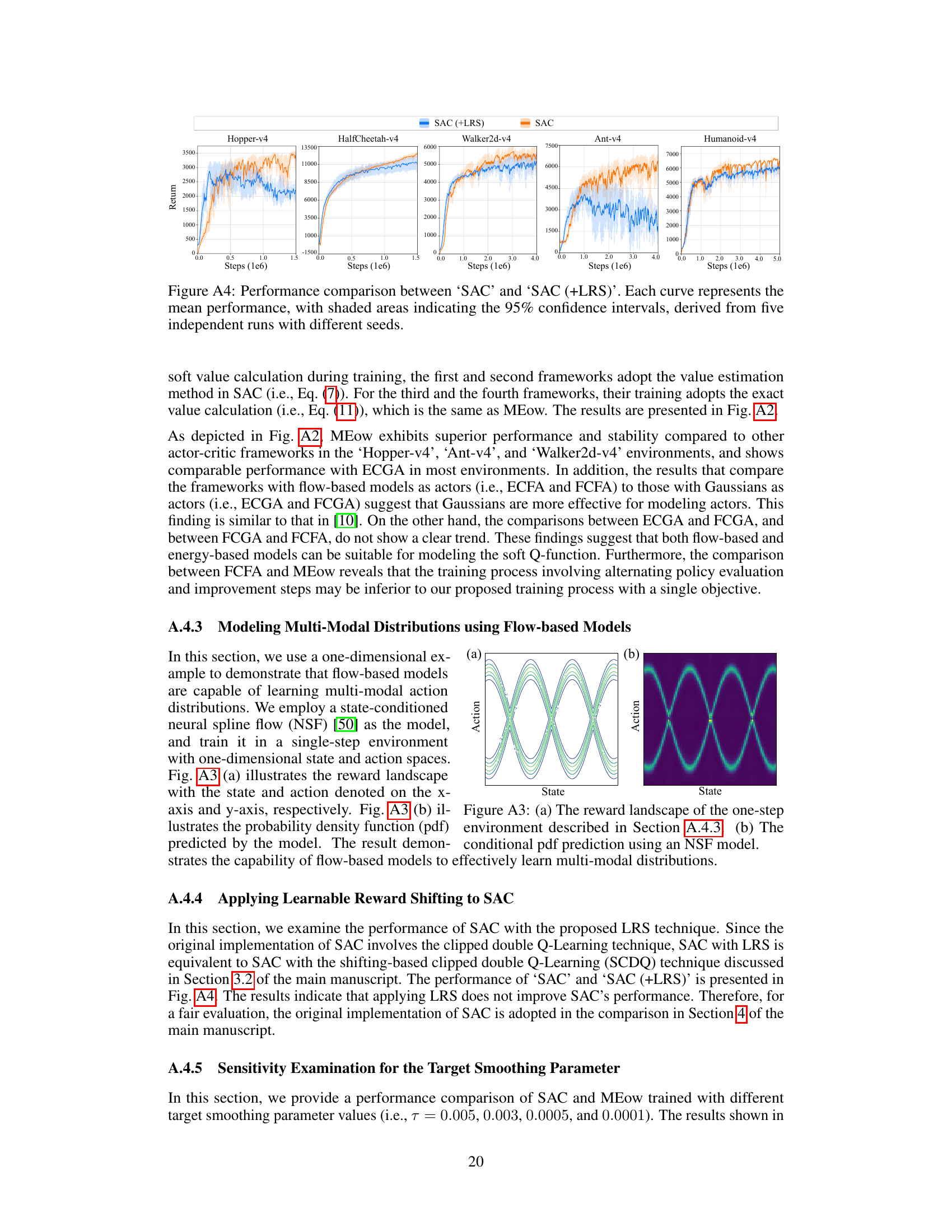

🔼 This figure shows the Jacobian determinant products of the linear and non-linear transformations used in the MEow model during training on the Hopper-v4 environment. The non-linear transformations exhibit a significant growth and decay, while the linear transformations show more stability. The learnable reward shifting (LRS) technique is shown to mitigate the instability in the non-linear transformations.

read the caption

Figure 1: The Jacobian determinant products for (a) the non-linear and (b) the linear transformations, evaluated during training in the Hopper-v4 environment. Subfigure (b) is presented on a log scale for better visualization. This experiment adopt the affine coupling layers [47] as the nonlinear transformations.

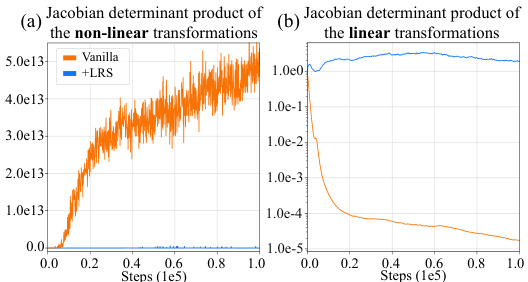

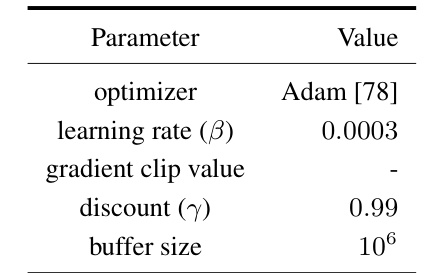

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters shared by all the experiments using the MEow model, including the optimizer, learning rate, gradient clip value, discount factor, and buffer size. These parameters were kept consistent across different environments and tasks to ensure a fair comparison.

read the caption

Table A1: Shared hyperparameters of MEow.

In-depth insights#

MaxEnt RL via EBFlow#

The proposed framework, “MaxEnt RL via EBFlow,” presents a novel approach to maximum entropy reinforcement learning by leveraging energy-based normalizing flows. This method uniquely combines policy evaluation and improvement into a single objective, eliminating the need for alternating optimization steps found in traditional actor-critic methods. By using EBFlow, the method bypasses the computationally expensive Monte Carlo approximation commonly used for soft value function estimation, resulting in greater efficiency and potentially improved accuracy. Furthermore, the ability of EBFlows to model multi-modal action distributions is a significant advantage, offering the potential for more robust and adaptable policies in complex environments. The approach’s integration of sampling and energy function calculation within a single framework streamlines the learning process, enhancing both theoretical understanding and practical performance. While promising, further investigation into the scalability and robustness of the EBFlow architecture in high-dimensional settings is crucial for assessing its broad applicability and potential limitations.

MEow Framework#

The MEow framework presents a novel approach to Maximum Entropy Reinforcement Learning (MaxEnt RL) by integrating policy evaluation and improvement steps within a unified Energy-Based Normalizing Flow (EBFlow) model. This single-objective training process avoids the alternating optimization of actor-critic methods, potentially leading to improved stability and efficiency. Key advantages include the ability to calculate the soft value function without Monte Carlo approximation, offering a more precise and efficient solution compared to previous methods. Furthermore, EBFlow’s inherent ability to model multi-modal action distributions facilitates efficient sampling and enhanced exploration. The framework’s unified structure and exact calculations contribute to potentially superior performance, particularly in high-dimensional environments as demonstrated in the experimental results. However, limitations exist regarding the computational cost of flow-based models and the reliance on specific assumptions for efficient deterministic inference. The effectiveness of learnable reward shifting and shifting-based clipped double Q-learning in enhancing performance is also a key aspect worthy of further investigation.

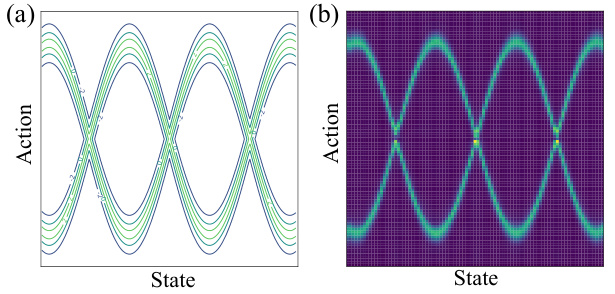

Multimodal Actions#

The concept of “Multimodal Actions” in reinforcement learning signifies a significant departure from traditional approaches that assume unimodal action distributions. Multimodality acknowledges that optimal actions in a given state might not be singular but rather a collection of distinct, equally valid choices. This is particularly crucial in complex environments where a single “best” action might be insufficient to capture the nuances of the problem. For example, in a robotic navigation task, multiple paths could lead to the same goal. A multimodal action representation is capable of capturing the inherent uncertainty in such scenarios and promoting exploration of diverse strategies. This contrasts with unimodal methods, which may converge to a suboptimal solution because of a limited search space. The inherent exploration-exploitation trade-off is thus improved with multimodal action learning as it allows the agent to explore a wider range of options, leading to more robust and adaptive behavior. Moreover, the capability of representing multimodal actions directly impacts the design of the policy network and the optimization algorithms employed. Techniques such as mixture models or flow-based models are often used to approximate the probability distribution of these multimodal actions. Further research into more efficient and accurate ways to learn and represent multimodal actions remains an important area of development in reinforcement learning.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a reinforcement learning paper, this might involve removing or altering key features, such as the actor network, critic network, entropy term, or specific reward shaping mechanisms. By observing how performance changes with each ablation, the researchers can quantify the impact of each component and validate design choices. A well-executed ablation study is crucial for establishing the effectiveness of the proposed approach and building confidence in its robustness. It’s important to note the selection of ablated components; researchers should carefully select features for removal based on existing literature and a sound theoretical justification. A thorough ablation study often involves multiple trials, each with different configurations to reduce noise and increase reliability of results. Finally, the results of the ablation study should be clearly presented and analyzed, illustrating the importance of specific components to the overall performance of the model.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this MaxEnt RL framework, MEow, could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of the flow-based model’s inference is crucial for faster training and broader applicability. Investigating alternative flow architectures beyond additive coupling layers could enhance performance and model capacity. Addressing the hyperparameter sensitivity, particularly the target smoothing factor (τ), through automated tuning or more robust parameterization strategies, is also needed. A deeper investigation into the theoretical underpinnings of MEow’s success, particularly in high-dimensional spaces, could provide valuable insights. Extending MEow’s capabilities to handle partial observability and non-Markov environments would significantly broaden its real-world relevance. Finally, exploring the integration of MEow with other advanced RL techniques, such as hierarchical RL or meta-RL, could unlock even more powerful solutions to complex problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

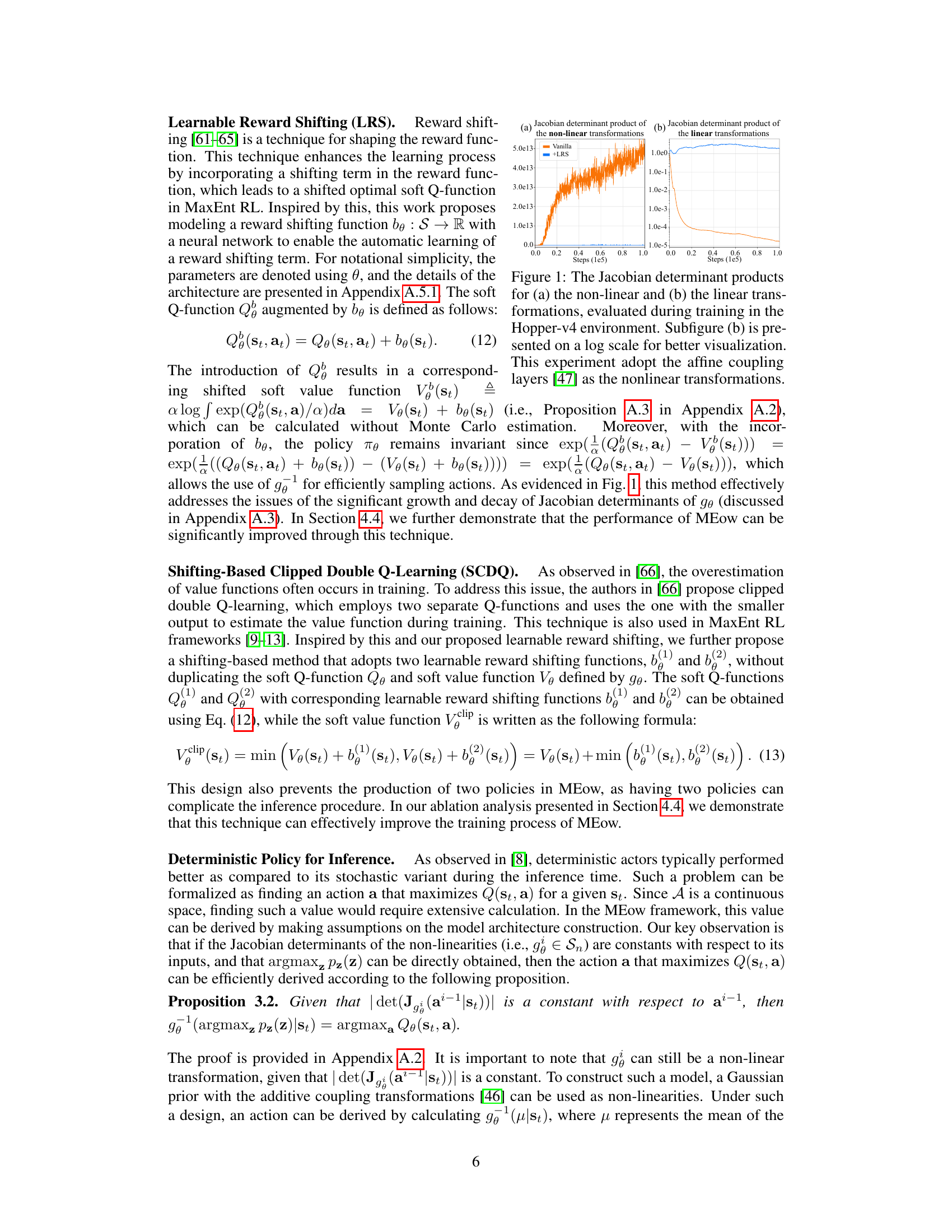

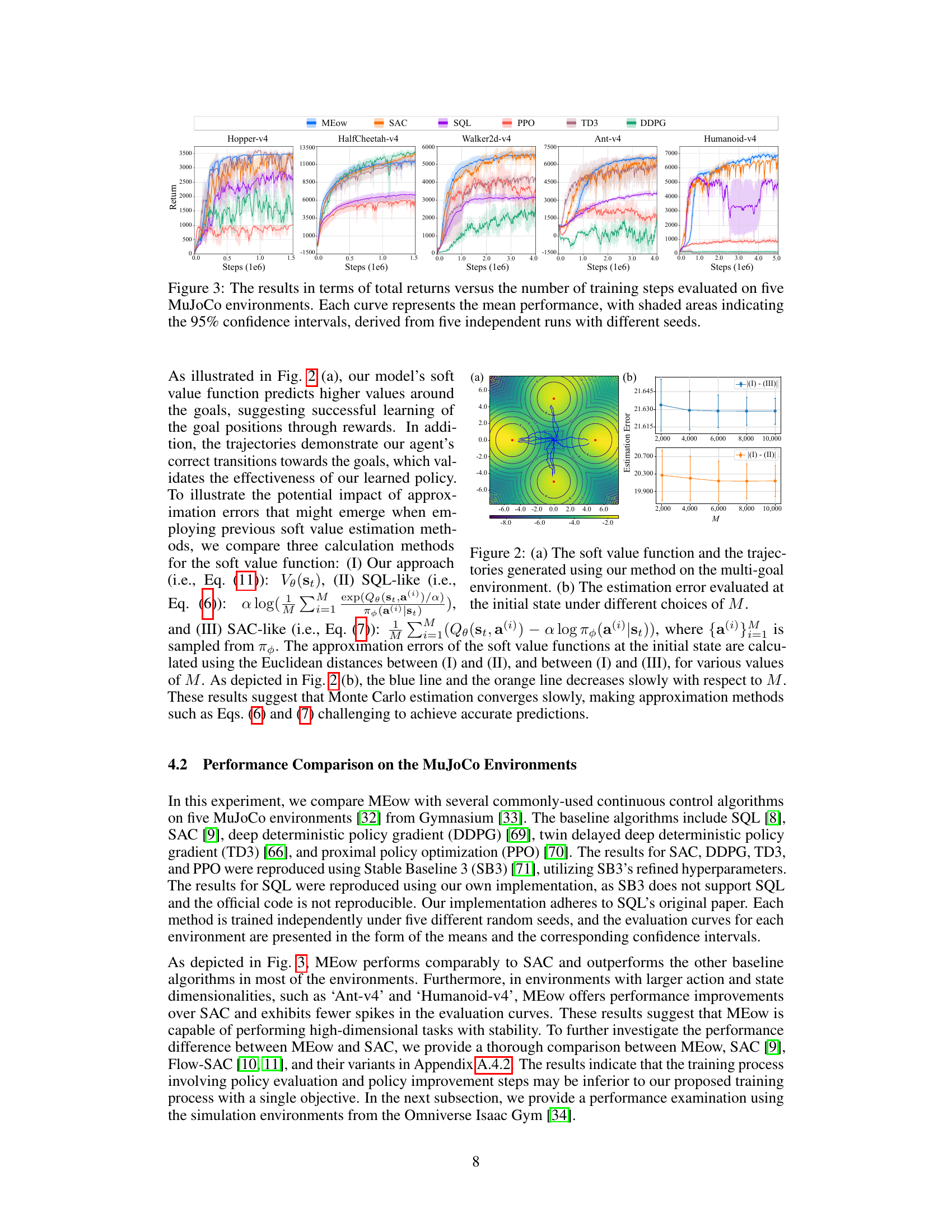

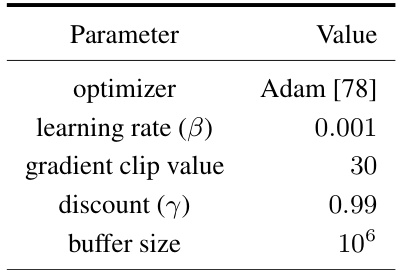

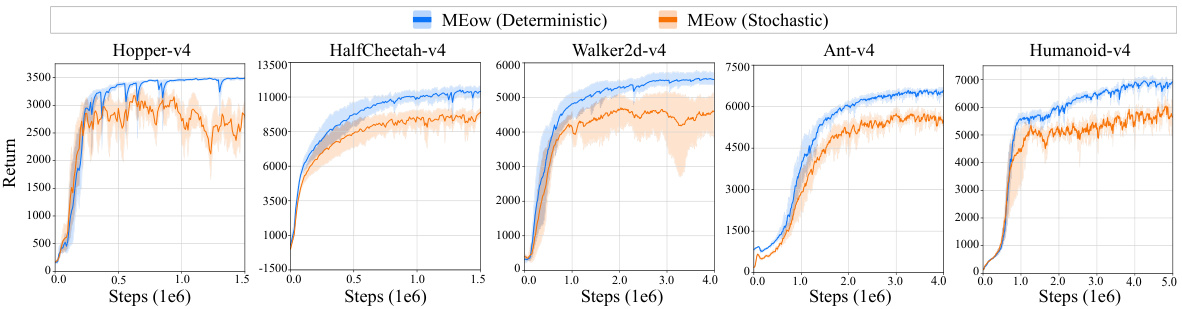

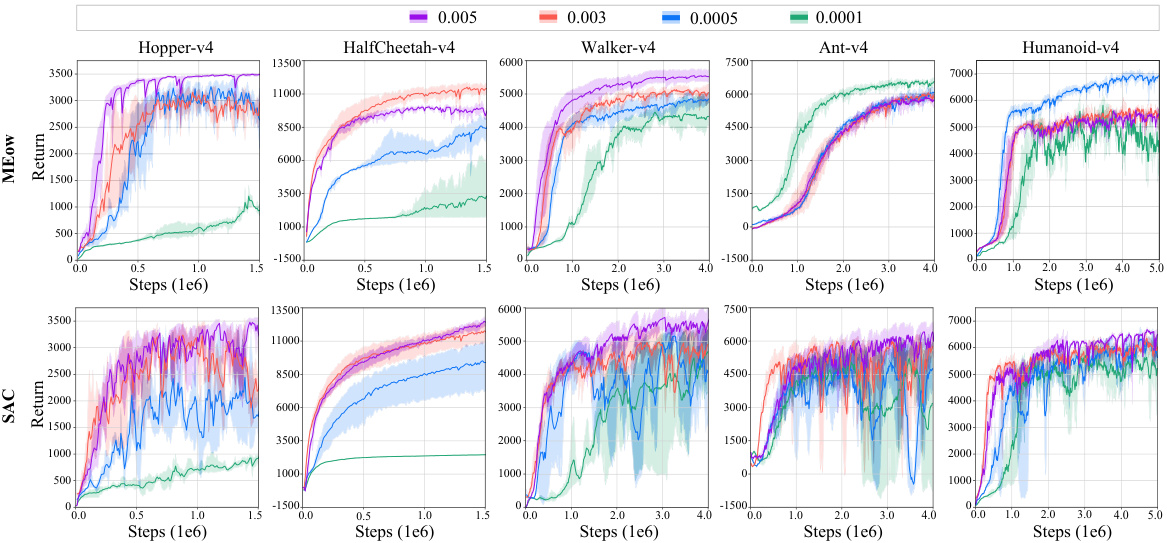

🔼 This figure compares the performance of MEow against several other reinforcement learning algorithms on five different MuJoCo environments. Each environment is represented by a separate graph. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis shows the total returns. Each line represents the mean performance of MEow and its comparison algorithms, averaged over five independent training runs with different random seeds. The shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals, providing a measure of uncertainty in the results. The graphs illustrate how the total return varies over time and how the performance of MEow compares with that of other algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 3: The results in terms of total returns versus the number of training steps evaluated on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

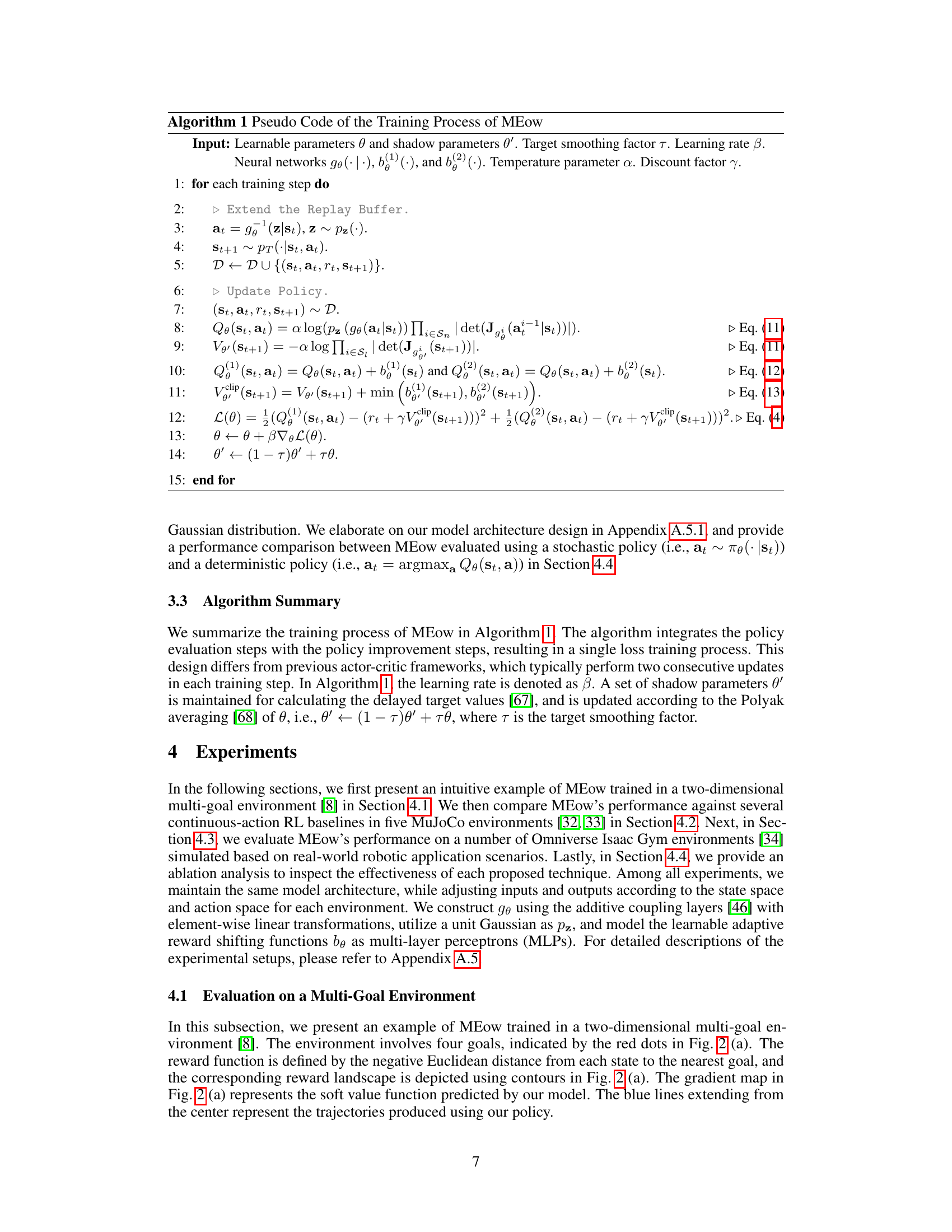

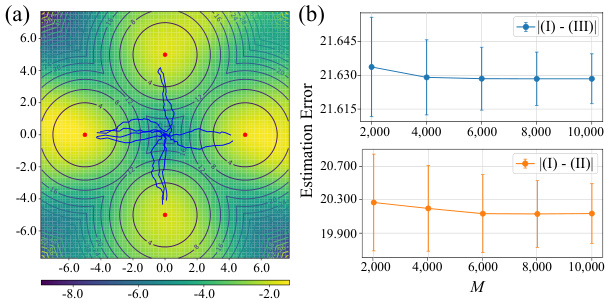

🔼 Figure 2(a) shows a contour plot of the soft value function learned by the proposed method in a 2D multi-goal environment. The blue lines represent the trajectories followed by the agent, clearly demonstrating the successful learning and proper transitions toward the goals. Figure 2(b) illustrates the impact of using Monte Carlo methods to estimate the soft value function by plotting the estimation errors with respect to the number of samples (M) used for different approximation methods. The results highlight the slow convergence of Monte Carlo estimation.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) The soft value function and the trajectories generated using our method on the multi-goal environment. (b) The estimation error evaluated at the initial state under different choices of M.

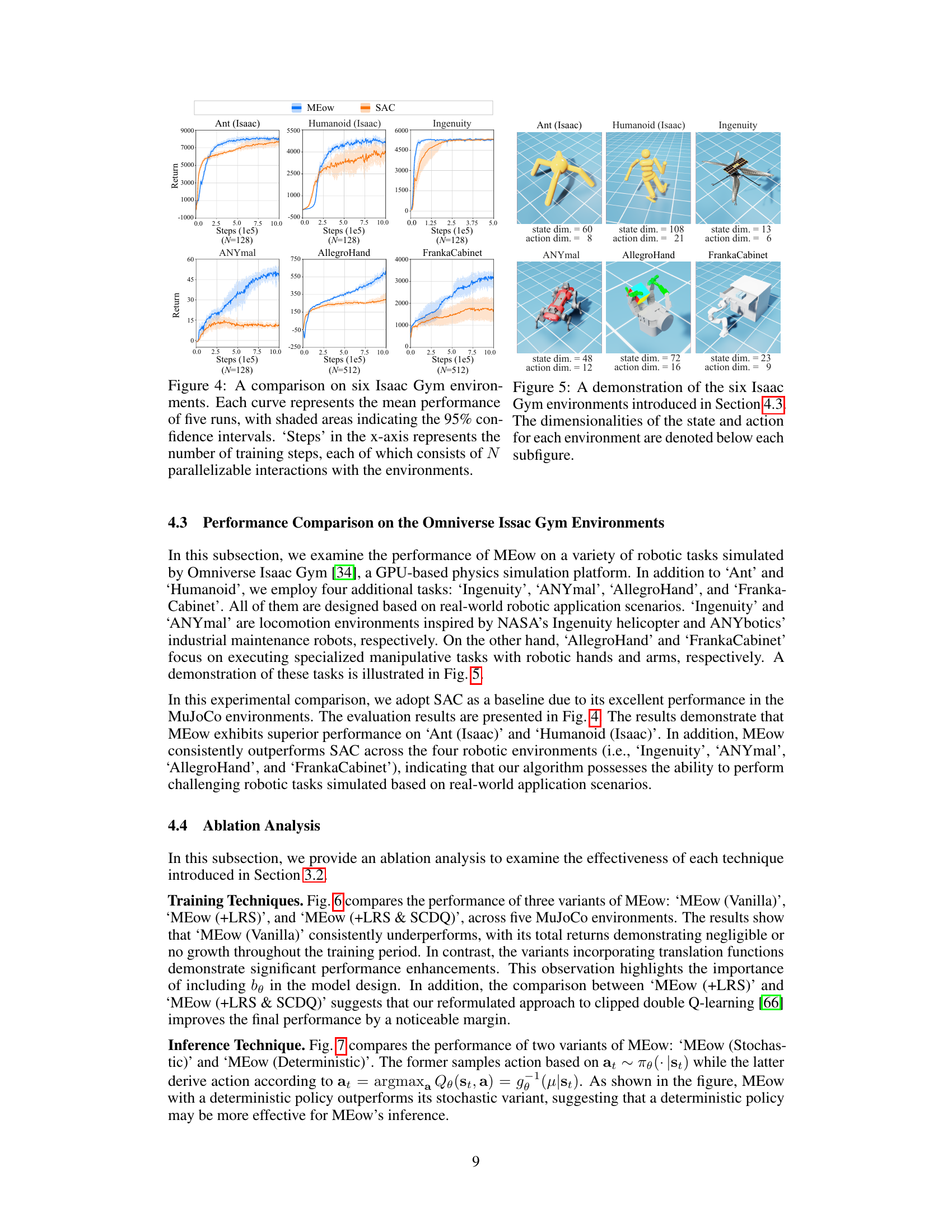

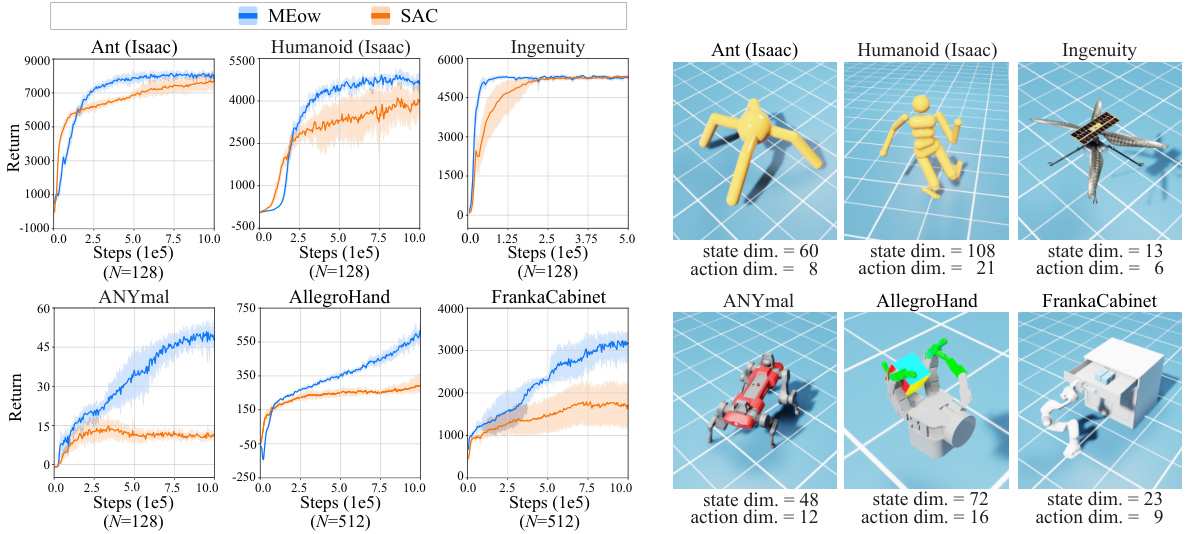

🔼 The figure shows the performance comparison between MEow and SAC on six different robotic tasks simulated using Omniverse Isaac Gym. The tasks vary in complexity and dimensionality, showcasing MEow’s ability to handle high-dimensional and complex robotic control problems. The plots show the total return over training steps for each environment. The shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals, indicating statistical significance. The number of parallelizable interactions (N) differs between some tasks, illustrating variations in computational load.

read the caption

Figure 4: A comparison on six Isaac Gym environments. Each curve represents the mean performance of five runs, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals. ‘Steps’ in the x-axis represents the number of training steps, each of which consists of N parallelizable interactions with the environments.

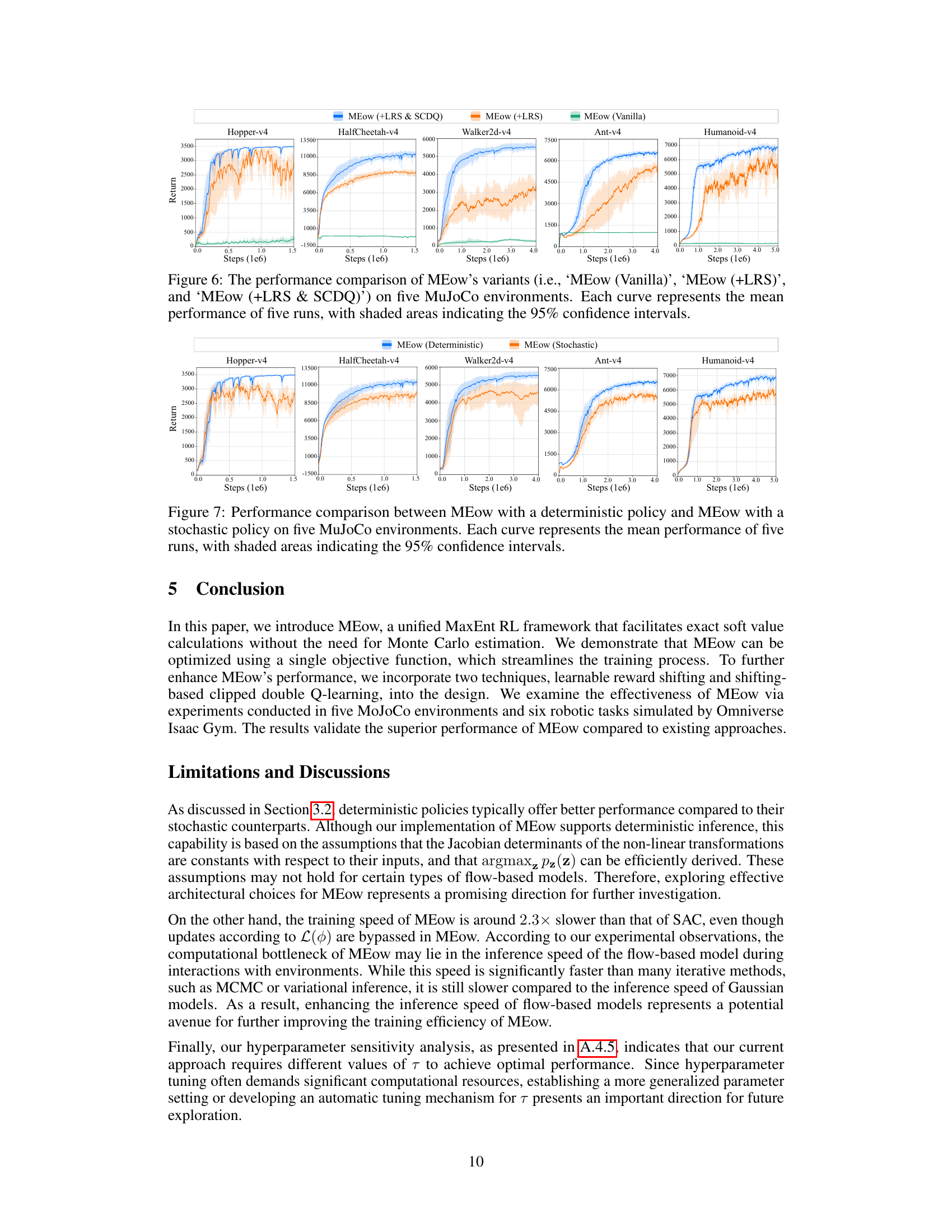

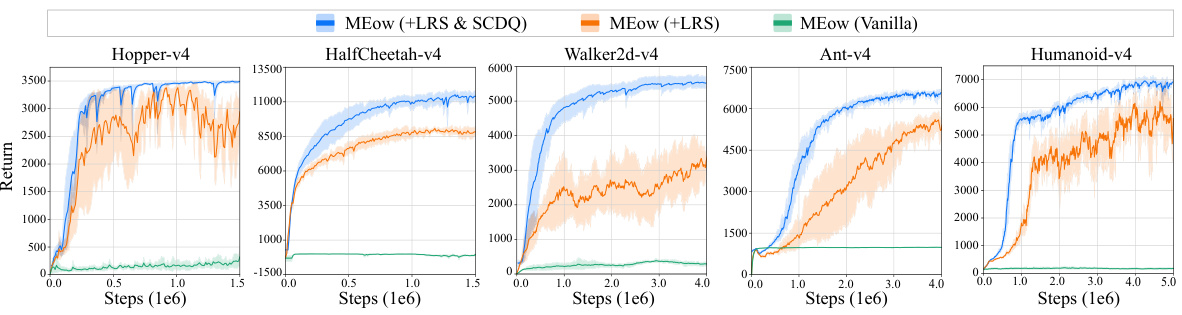

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three variants of the MEow algorithm across five MuJoCo benchmark environments. The three variants are: MEow (Vanilla), MEow with Learnable Reward Shifting (+LRS), and MEow with both Learnable Reward Shifting and Shifting-Based Clipped Double Q-Learning (+LRS & SCDQ). Each line shows the mean average return over five independent runs with different random seeds, and the shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. The figure demonstrates the significant performance improvement achieved by incorporating the proposed training techniques (LRS and SCDQ).

read the caption

Figure 6: The performance comparison of MEow’s variants (i.e., ‘MEow (Vanilla)', ‘MEow (+LRS)', and 'MEow (+LRS & SCDQ)') on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance of five runs, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals.

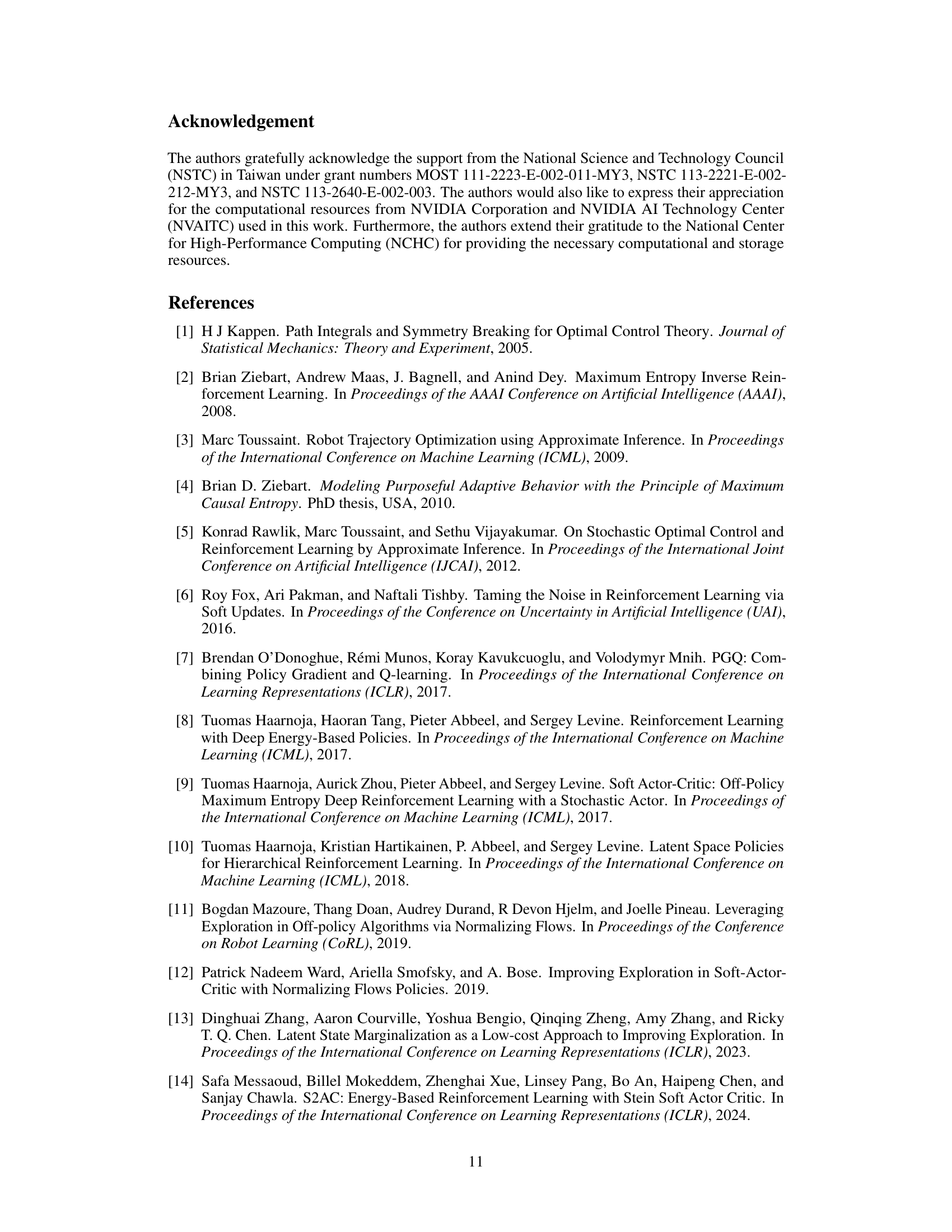

🔼 This figure displays the results of the experiments conducted on five different MuJoCo environments. For each environment, the total returns over the training steps are presented in terms of mean performance and 95% confidence intervals. Five independent runs with different random seeds were used for each environment. The x-axis represents the number of training steps (in millions), and the y-axis represents the total return.

read the caption

Figure 3: The results in terms of total returns versus the number of training steps evaluated on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

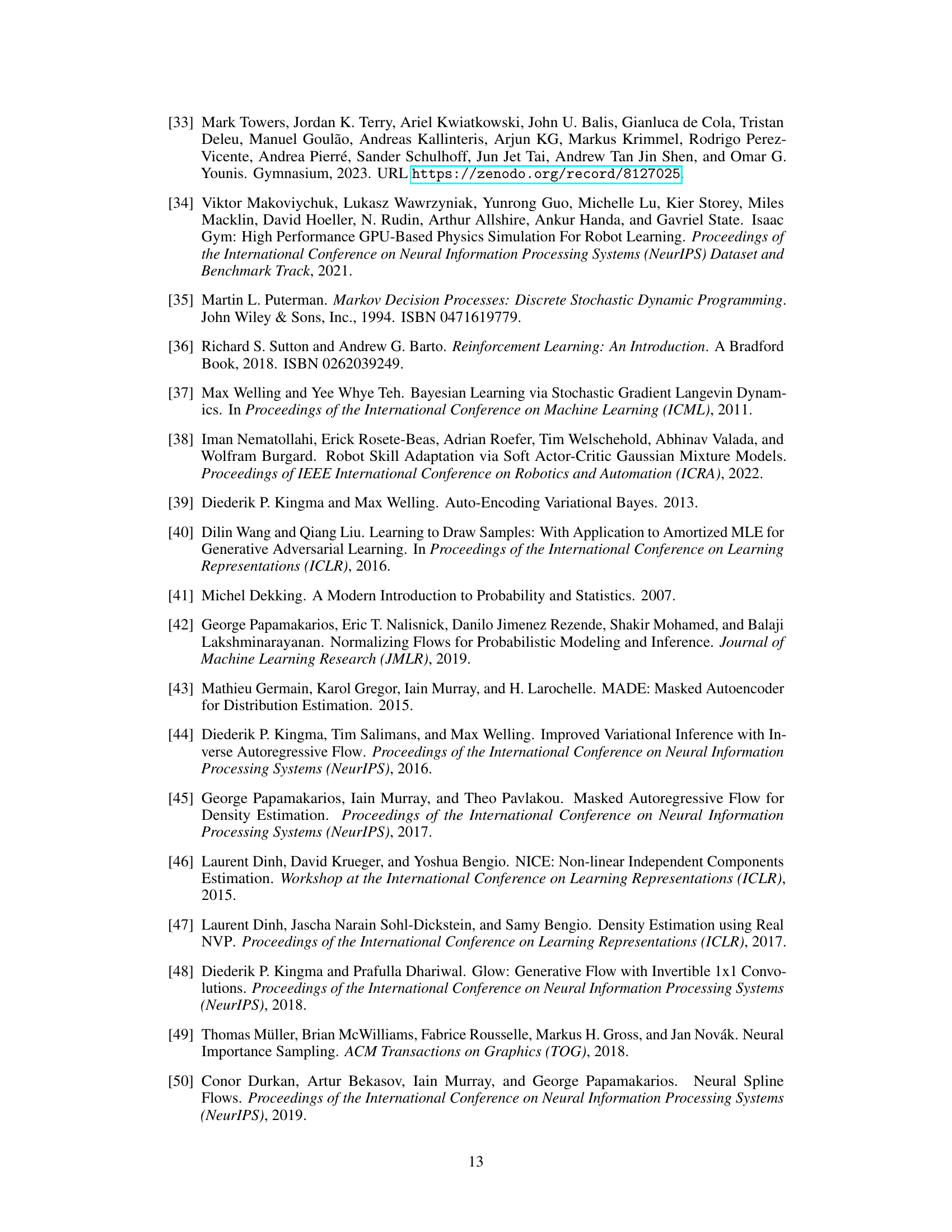

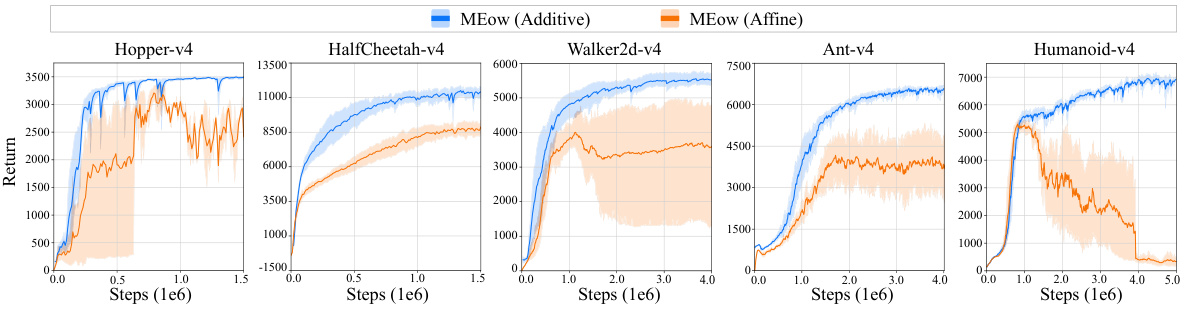

🔼 This figure compares the performance of MEow using two different types of coupling layers in the normalizing flow: additive coupling and affine coupling. The results are shown across five MuJoCo benchmark environments (Hopper-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, Walker2d-v4, Ant-v4, and Humanoid-v4). Each line represents the average performance across five independent training runs, with the shaded area showing the 95% confidence interval, illustrating the variability in performance.

read the caption

Figure A1: Performance comparison between MEow with additive coupling transformations in gθ and MEow with affine coupling transformations in gθ on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

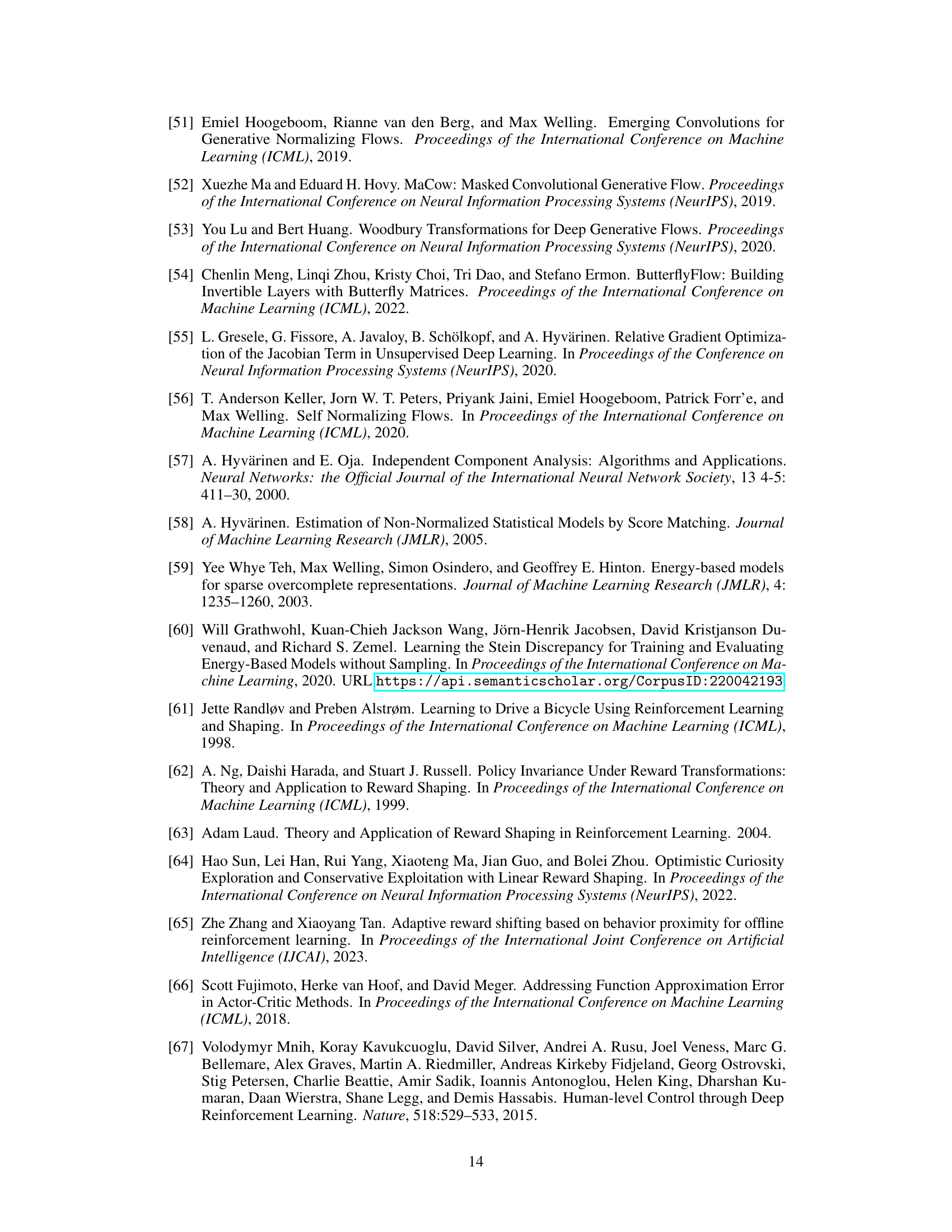

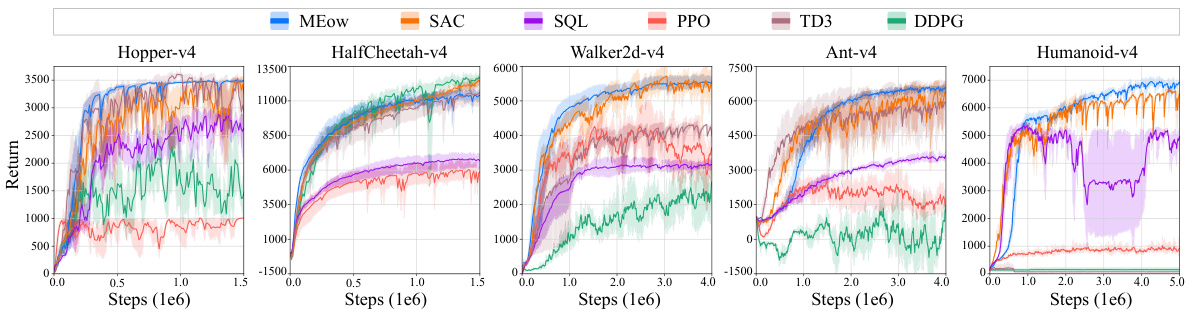

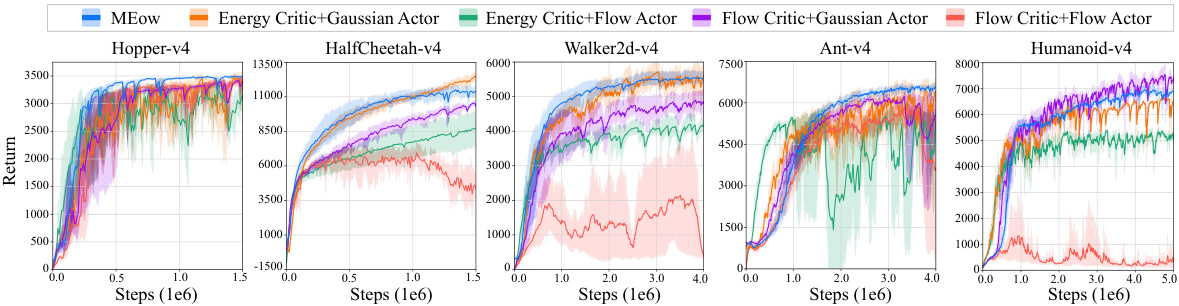

🔼 This figure compares the performance of MEow against four different actor-critic frameworks formulated based on prior works [9-11]. The frameworks include: (1) SAC [9], with the critic modeled as an energy-based model and the actor as a Gaussian; (2) [10, 11], where the critic is also an energy-based model, but the actor is a flow-based model; (3) flow-based model for the critic and Gaussian for the actor; (4) flow-based model for both the critic and the actor. The results are presented for five MuJoCo environments: Hopper-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, Walker2d-v4, Ant-v4, and Humanoid-v4. Each curve represents the mean performance derived from five independent runs, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals.

read the caption

Figure A2: Performance comparison between ‘MEow’, ‘Energy Critic+Gaussian Actor’ (ECGA), ‘Energy Critic+Flow Actor’ (ECFA), ‘Flow Critic+Gaussian Actor’ (FCGA), and ‘Flow Critic+Flow Actor’ (FCFA) on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

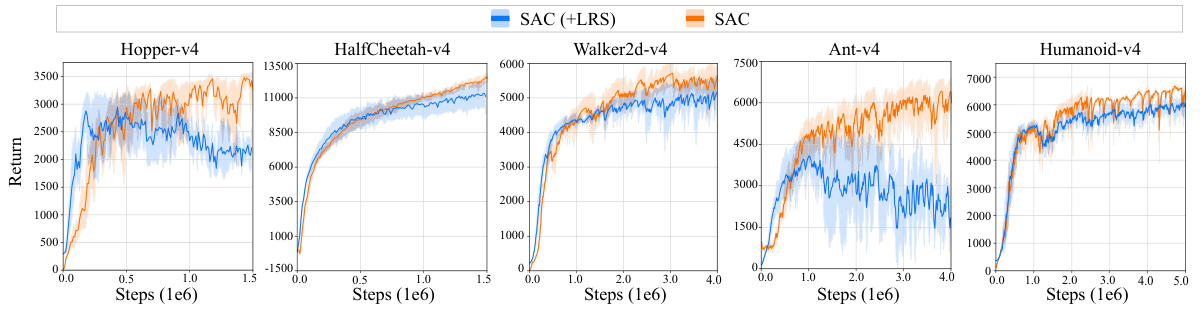

🔼 This figure presents the learning curves of five different reinforcement learning algorithms on five benchmark MuJoCo environments. The y-axis shows the total returns (average reward per episode), while the x-axis shows the number of training steps. Each line represents the average performance of an algorithm across five independent runs, and the shaded region represents the 95% confidence interval. This demonstrates the performance comparison and stability of the algorithms across various tasks.

read the caption

Figure 3: The results in terms of total returns versus the number of training steps evaluated on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

🔼 Figure 2(a) shows a contour plot of the soft value function learned by the model in a multi-goal environment. The blue lines represent the agent’s trajectories, clearly showing that it successfully learns to navigate to the goals. Figure 2(b) compares the soft value function estimates using different methods (the proposed method and two approximations, SQL-like and SAC-like) for varying numbers of Monte Carlo samples (M). The estimation error is calculated as the Euclidean distance between the true value and the approximation. This demonstrates that the proposed method is more efficient than the approximations.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) The soft value function and the trajectories generated using our method on the multi-goal environment. (b) The estimation error evaluated at the initial state under different choices of M.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed MEow algorithm against several baselines on five different MuJoCo environments (Hopper-v4, HalfCheetah-v4, Walker2d-v4, Ant-v4, and Humanoid-v4). Each environment’s results are shown in a separate subplot. The y-axis shows the total return, and the x-axis represents the number of training steps. Each line represents the average performance across five independent runs with different random seeds, and the shaded regions represent the 95% confidence intervals, giving a measure of uncertainty in the results.

read the caption

Figure 3: The results in terms of total returns versus the number of training steps evaluated on five MuJoCo environments. Each curve represents the mean performance, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals, derived from five independent runs with different seeds.

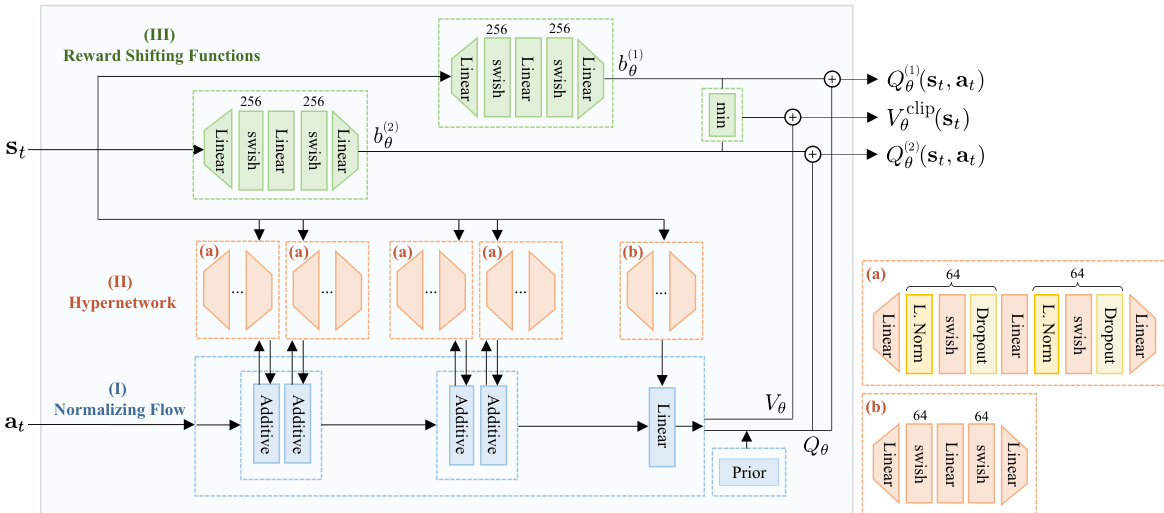

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the MEow model, which consists of three main parts: a normalizing flow for modeling the policy, a hypernetwork to generate parameters for the normalizing flow, and learnable reward shifting functions. The hypernetwork has two branches: one for non-linear transformations and one for linear transformations within the normalizing flow. The reward shifting functions help to stabilize the training process.

read the caption

Figure A6: The architecture adopted in MEow. This architecture consists of three primary components: (I) normalizing flow, (II) hypernetwork, and (III) reward shifting function. The hypernetwork includes two distinct types of networks, labeled as (a) and (b), which are responsible for generating weights for the non-linear and linear transformations within the normalizing flow, respectively. Layer normalization is denoted as 'L. Norm' in (a).

More on tables

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm in the experiments. These parameters were shared across all environments and remained consistent throughout the experiments. The optimizer used was Adam, with a learning rate of 0.0003, a discount factor of 0.99, and a buffer size of 106. Gradient clipping was not used (indicated by ‘-’).

read the caption

Table A2: Shared hyperparameters of SAC.

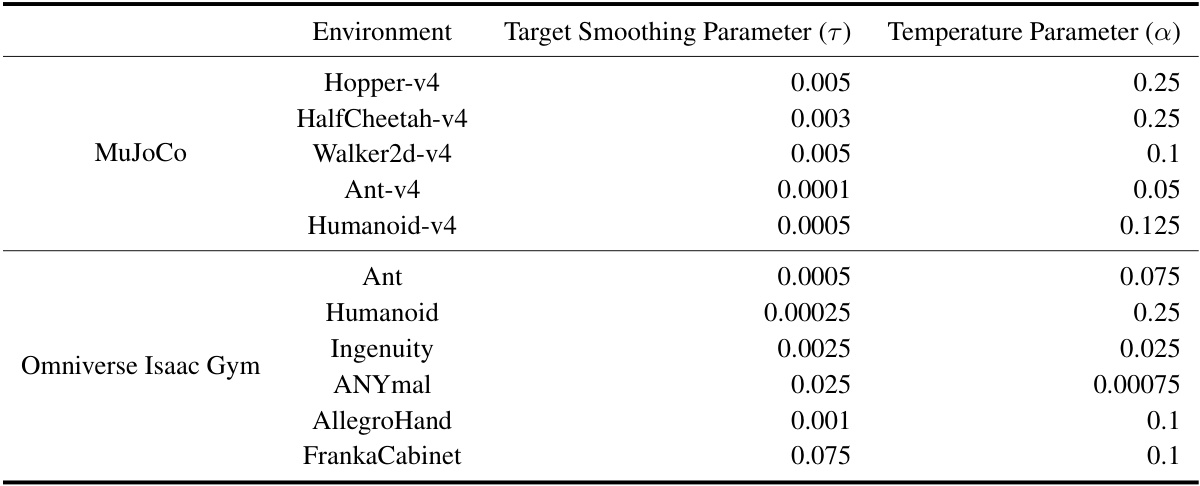

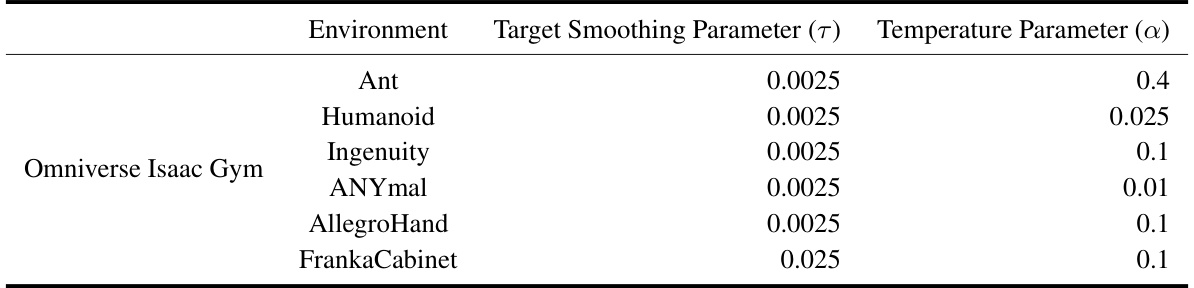

🔼 This table lists the target smoothing parameter (τ) and temperature parameter (α) used in the MEow algorithm for each of the MuJoCo and Omniverse Isaac Gym environments. These hyperparameters were tuned for each environment individually to achieve optimal performance.

read the caption

Table A3: A list of environment-specific hyperparameters used in MEow.

🔼 This table lists the target smoothing parameter (τ) and temperature parameter (α) used in the MEow algorithm for each of the six Omniverse Isaac Gym environments and five MuJoCo environments. These hyperparameters were tuned specifically for each environment to optimize performance. The target smoothing parameter controls the rate at which the target network is updated, balancing stability and responsiveness. The temperature parameter regulates exploration-exploitation in maximum entropy reinforcement learning.

read the caption

Table A3: A list of environment-specific hyperparameters used in MEow.

Full paper#