↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) usually struggle with detailed region description and reasoning due to their reliance on coarse image-level alignment. Traditional methods for integrating referring abilities into MLLMs are typically expensive and require substantial training. This limits their adaptability and generalizability to new domains.

This paper introduces ControlMLLM, a training-free method that injects visual prompts into MLLMs by optimizing a learnable latent variable. By controlling the attention response during inference, the model effectively attends to visual tokens in referring regions. This approach enables detailed regional description and reasoning, supporting various prompt types (box, mask, scribble, point) without extensive training. The results show ControlMLLM’s effectiveness across domains and its improved interpretability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multimodal large language models because it presents a training-free method for injecting visual prompts into models. This is significant because it overcomes the limitations of traditional training-based approaches, which are expensive and may not generalize well to new domains. The proposed method shows promise for enhancing the capabilities of MLLMs in tasks requiring visual and textual understanding, thus opening up new research directions in the field.

Visual Insights#

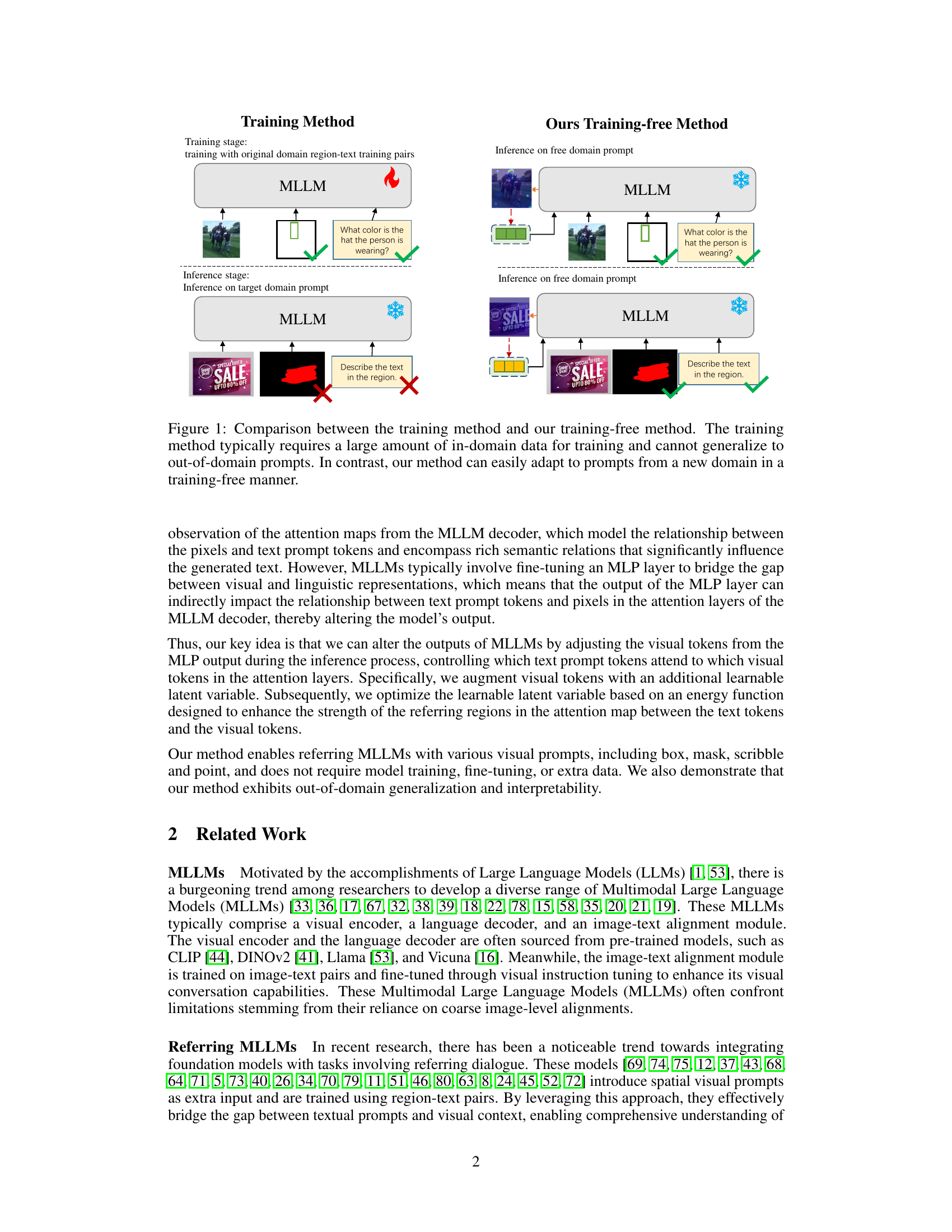

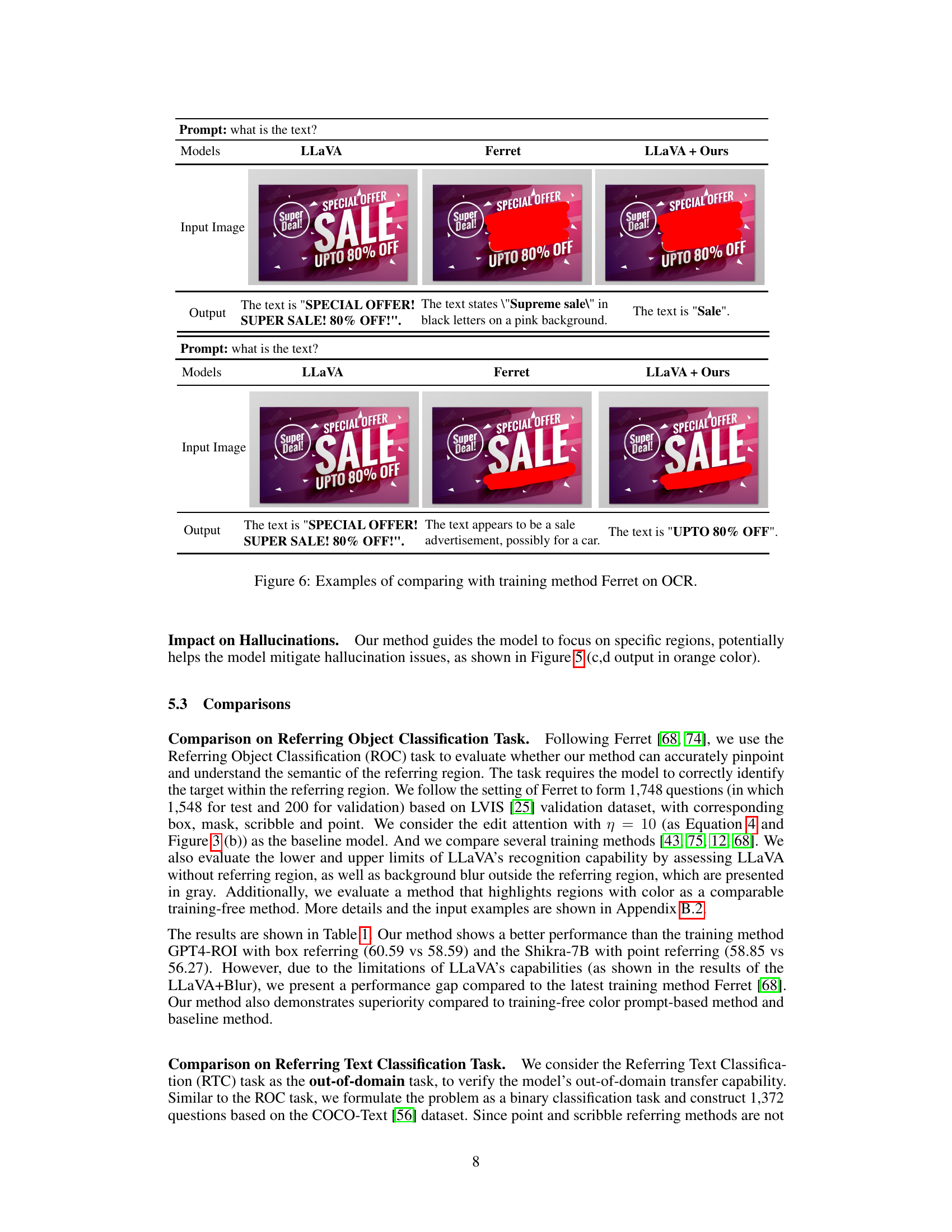

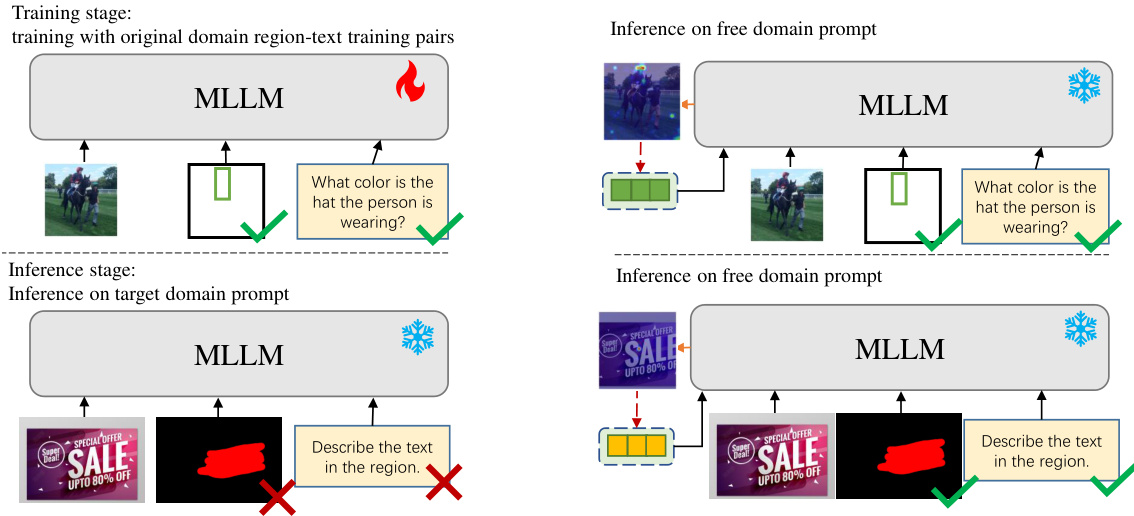

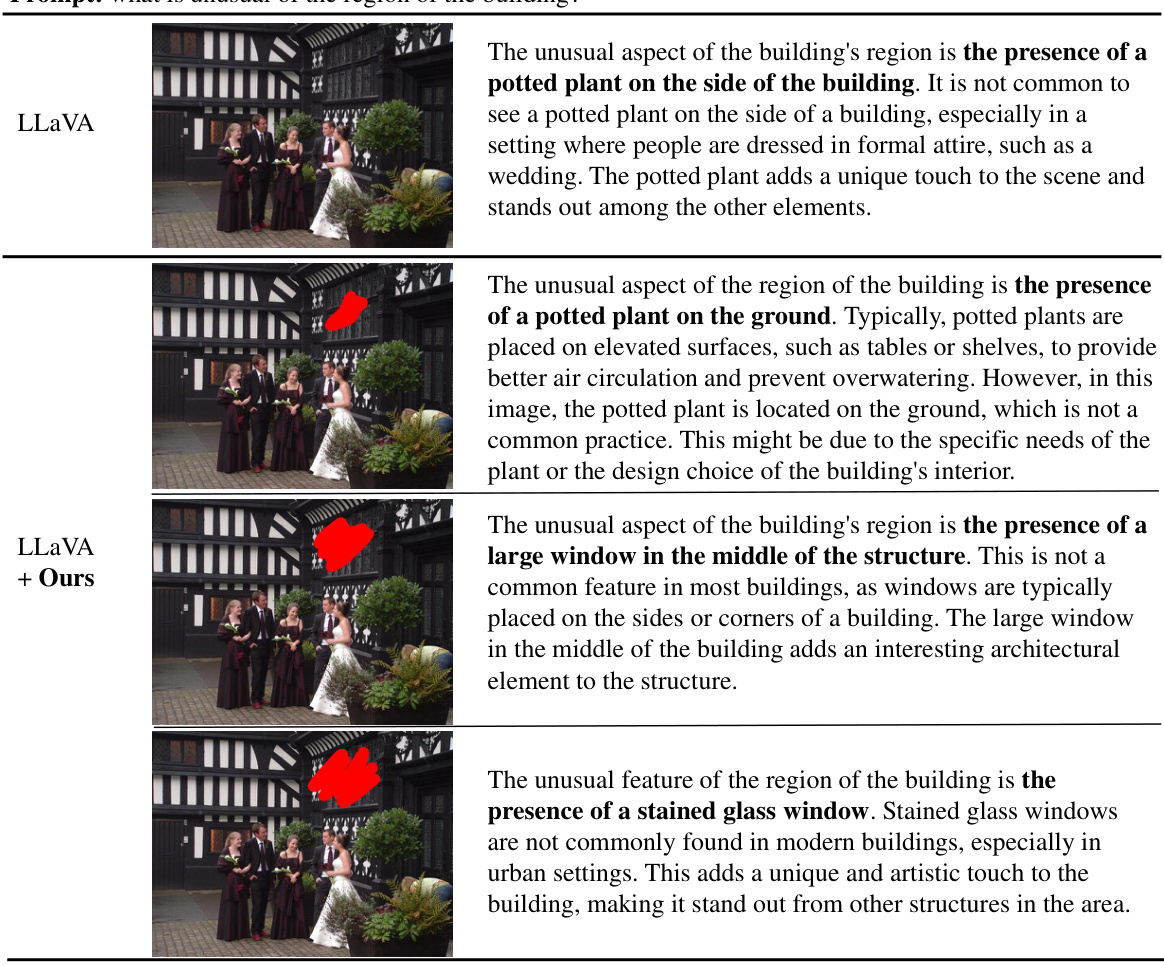

This figure compares traditional training methods for Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) with the proposed training-free method. The traditional method requires extensive in-domain training data and struggles with out-of-domain generalization. In contrast, the training-free approach leverages learnable latent variables to adapt to new domains without retraining, showcasing its flexibility and efficiency.

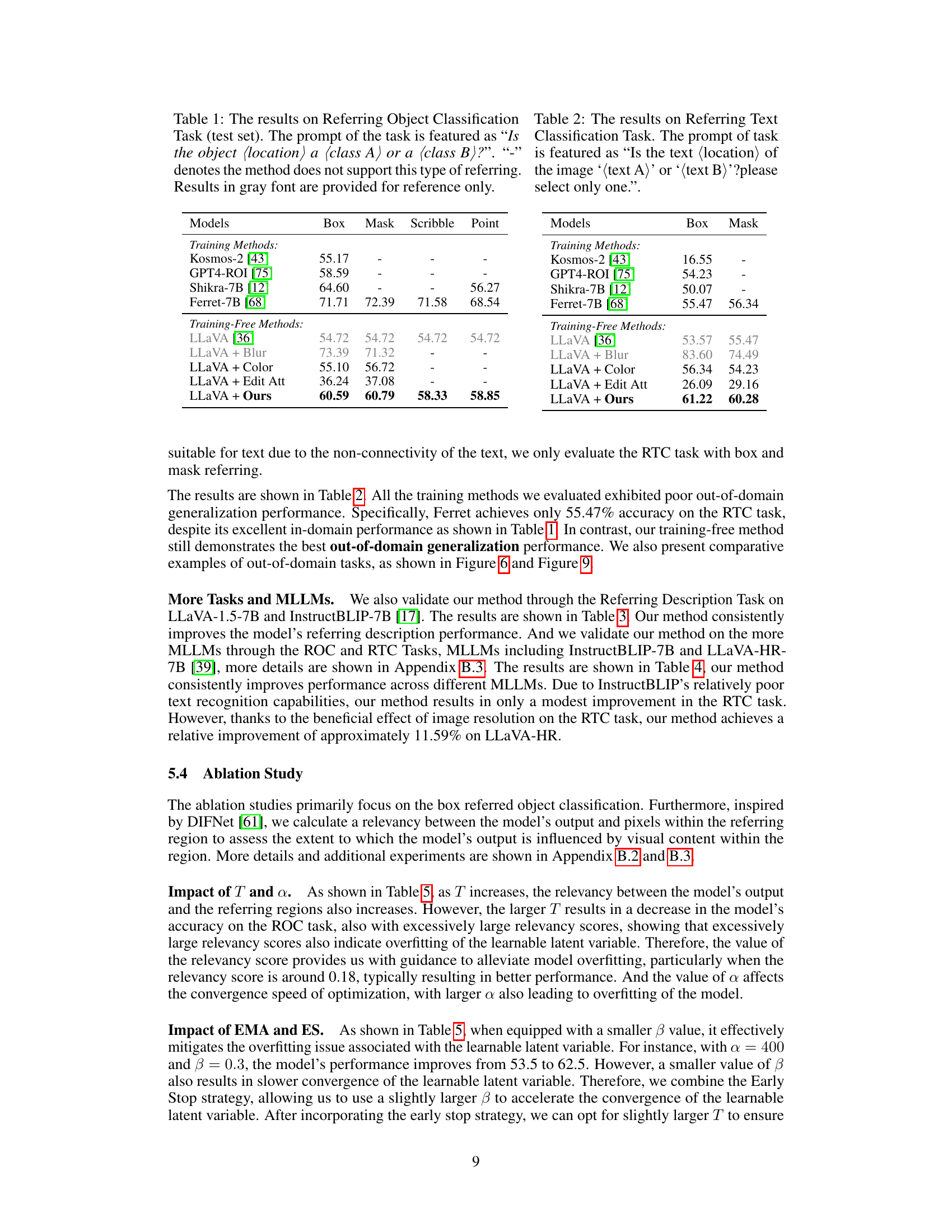

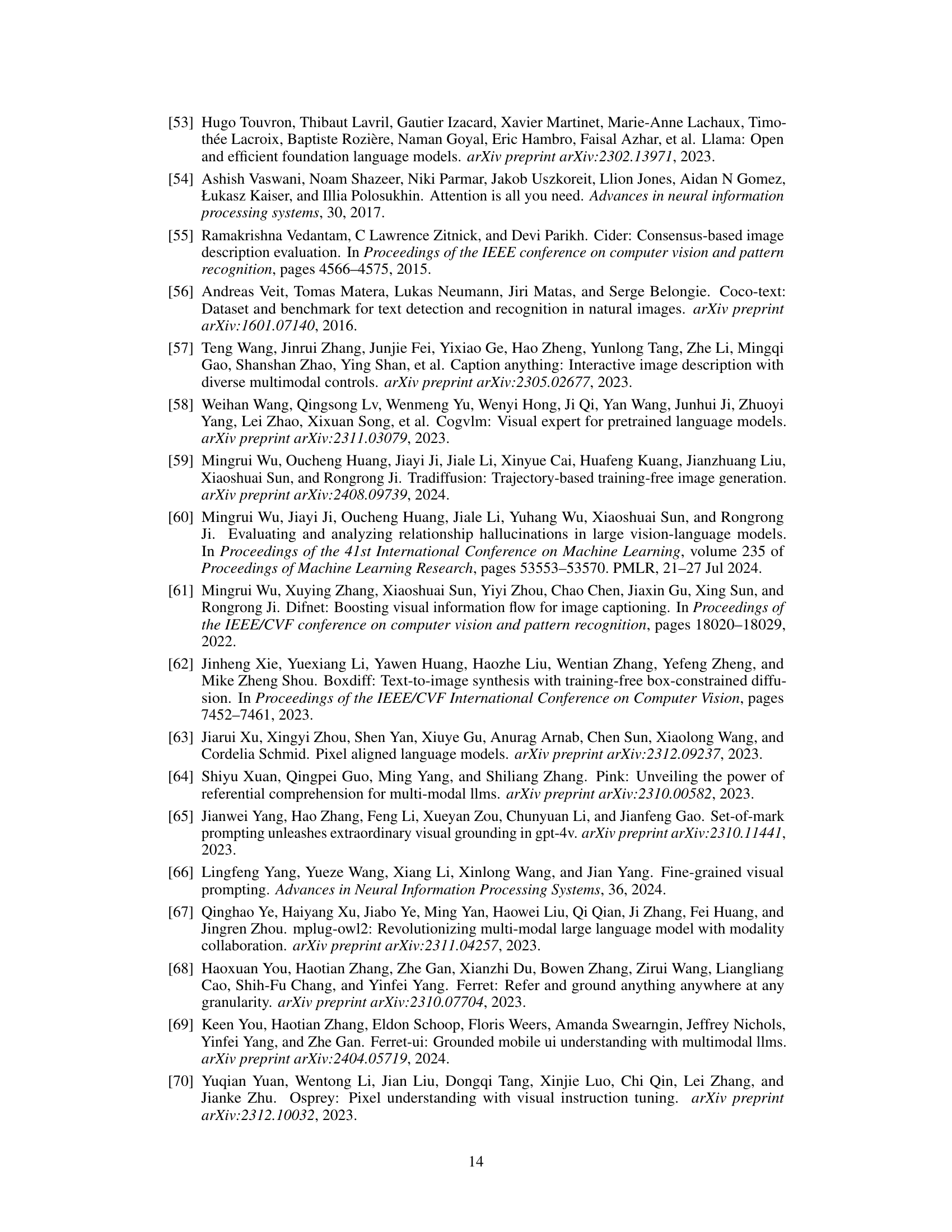

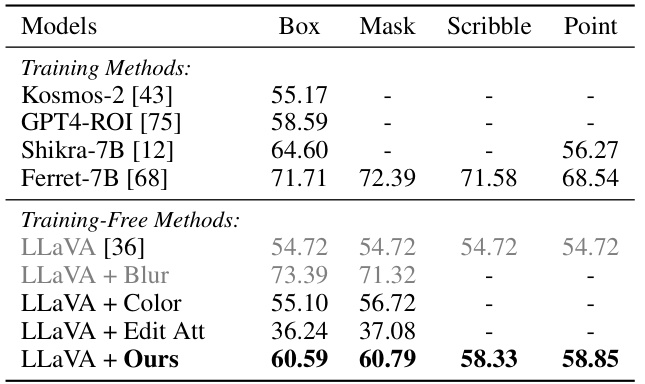

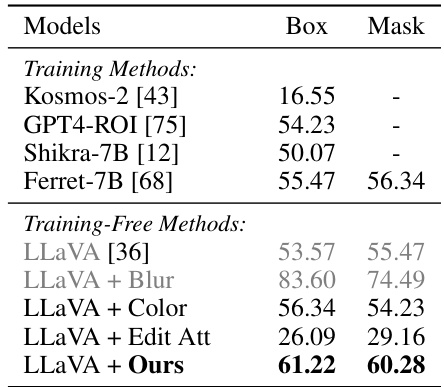

This table presents the results of the Referring Object Classification task on a test set. The task involves determining whether an object in a specified location within an image is of class A or class B. The table compares various methods, both training-based and training-free, assessing their performance across different types of referring inputs (box, mask, scribble, point). The numbers represent the accuracy of each method, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed training-free method, especially when compared to existing training-based methods.

In-depth insights#

Visual Prompt Tuning#

Visual prompt tuning represents a significant advancement in multimodal learning, bridging the gap between visual and textual information within large language models (LLMs). It addresses the limitations of traditional methods that rely heavily on extensive training data and fine-tuning, often hindering generalization and adaptability to new domains. By directly manipulating visual tokens within the LLM inference process, visual prompt tuning offers a training-free approach. This is achieved by optimizing a learnable latent variable, modifying the attention mechanisms to guide the model’s focus towards specific regions of the input image as indicated by the visual prompt. This allows for greater control and interpretability, enabling detailed region description and reasoning without retraining. The effectiveness of visual prompt tuning is demonstrated across various visual prompt types (box, mask, scribble, point) and its applicability to out-of-domain tasks shows its potential as a robust and flexible method for enhancing the referring capabilities of MLLMs.

Latent Variable Opt.#

The concept of ‘Latent Variable Optimization’ within the context of a multimodal large language model (MLLM) is a powerful technique for training-free visual prompt learning. It leverages the existing attention mechanisms of the MLLM, avoiding the need for retraining or fine-tuning. By introducing a learnable latent variable and optimizing it based on an energy function, the model can effectively control the attention weights to focus on specific regions of interest within the input image. This allows for more precise and nuanced interactions with the visual input, enabling finer-grained region description and reasoning. The training-free nature is crucial as it allows for seamless adaptation to different visual inputs and domains, enhancing the model’s flexibility and generalization capabilities. However, successful application depends on carefully designed energy functions and effective optimization strategies. Interpretability is also improved as the attention maps can now more clearly reflect the influence of the visual prompt. A key challenge lies in efficiently optimizing the latent variable, as the computational cost could scale depending on the complexity of the energy function and the number of optimization steps required. Furthermore, careful consideration is needed to avoid overfitting during the optimization process.

Attention Mechanism#

Attention mechanisms are crucial in modern deep learning, particularly within large language models (LLMs) and multimodal LLMs (MLLMs). They allow the model to focus on specific parts of the input, weighting different elements based on their relevance to the current task. In LLMs, attention helps weigh different words in a sentence, determining which words are most crucial for understanding the overall meaning or generating a response. In MLLMs, the attention mechanism bridges the gap between visual and textual data, enabling the model to relate visual elements (pixels, objects) to words in the textual input, and thereby generating descriptions or answering questions that reflect a detailed understanding of both modalities. A key challenge with MLLMs is enabling fine-grained control of attention, directing it to specific regions of interest within the visual input. This requires methods for effectively injecting visual prompts or cues to guide the attention mechanism. The paper explores training-free approaches for MLLM to improve this fine-grained attention control, leveraging the inherent attention capabilities without the need for extensive retraining, leading to improved interpretability and adaptability. This is a significant area of research, as it seeks to enhance the ability of MLLMs to precisely process complex multimodal inputs and to generate more accurate and nuanced outputs.**

Training-Free Method#

The concept of a ‘Training-Free Method’ in the context of multimodal large language models (MLLMs) is intriguing. It suggests a paradigm shift away from traditional, data-hungry training regimes. Such a method would likely leverage the pre-trained knowledge of the MLLM to adapt to new visual prompts without requiring additional training data or model retraining. This could involve techniques like prompt engineering, attention manipulation, or learnable latent variable optimization. A key challenge would be achieving comparable performance to traditional fine-tuning methods while remaining training-free. The success of such a method would depend on the inherent capabilities of the pre-trained MLLM and the effectiveness of the chosen adaptation strategy. Interpretability and generalization to unseen domains are crucial considerations for evaluation. Ultimately, a training-free approach offers potential for faster, more efficient, and potentially more cost-effective MLLM deployment, but achieving this while maintaining accuracy and robustness is a substantial hurdle.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this training-free visual prompt learning method for MLLMs are plentiful. Improving the efficiency of the latent variable optimization process is key; exploring alternative optimization algorithms or more efficient energy functions could significantly reduce inference time. Extending the approach to handle multiple visual prompts simultaneously would enhance the model’s ability to understand complex scenes and respond to more nuanced queries. The current method focuses on a single referring region; enabling the handling of multiple regions would broaden applicability. Investigating different visual prompt modalities beyond box, mask, scribble, and point to cover diverse user interactions is crucial, such as free-form sketches or natural language descriptions of regions. Further study should explore the model’s robustness to noise in visual inputs and variations in image quality. Finally, a thorough evaluation across a wider range of MLLMs and benchmarking against state-of-the-art referring methods is needed to confirm the generality and effectiveness of the proposed approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

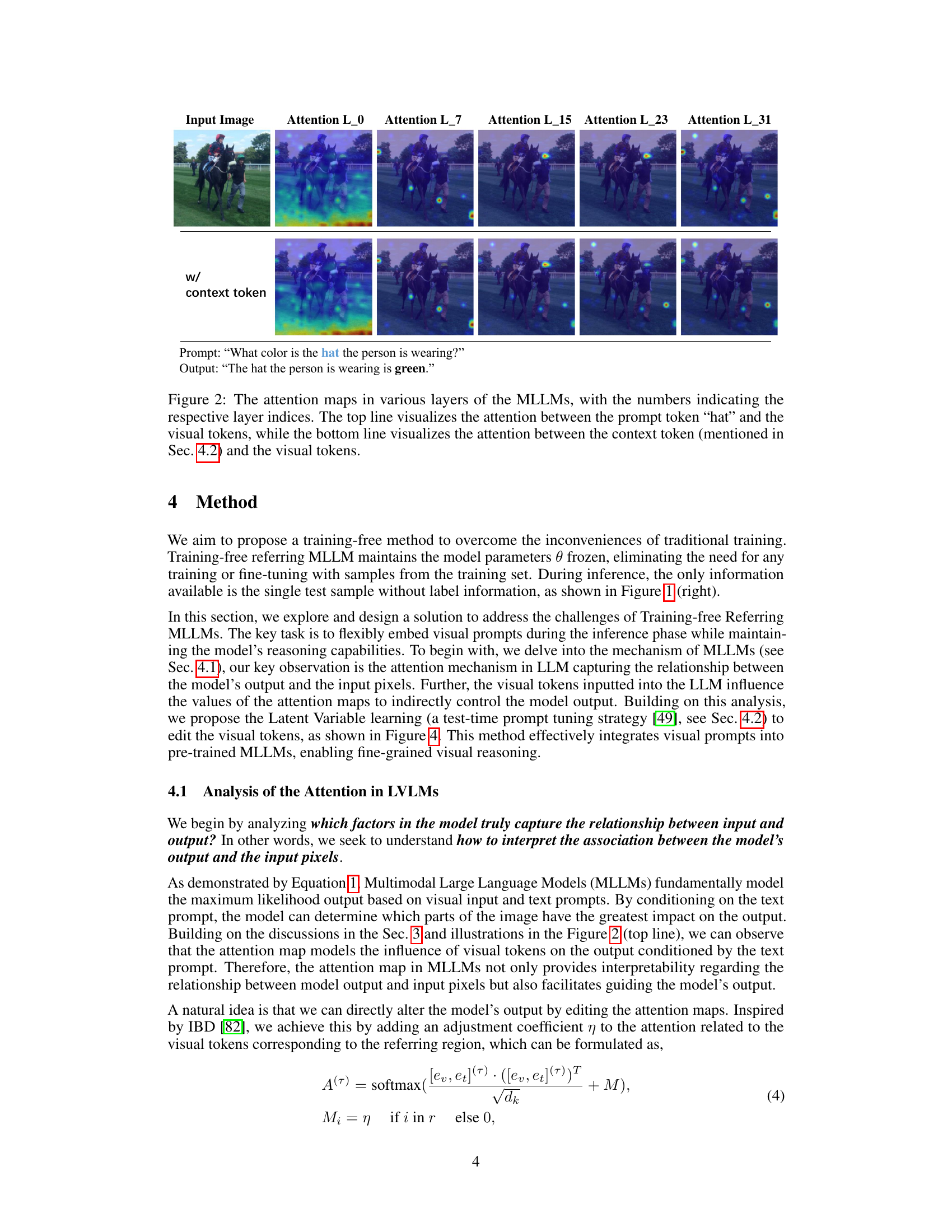

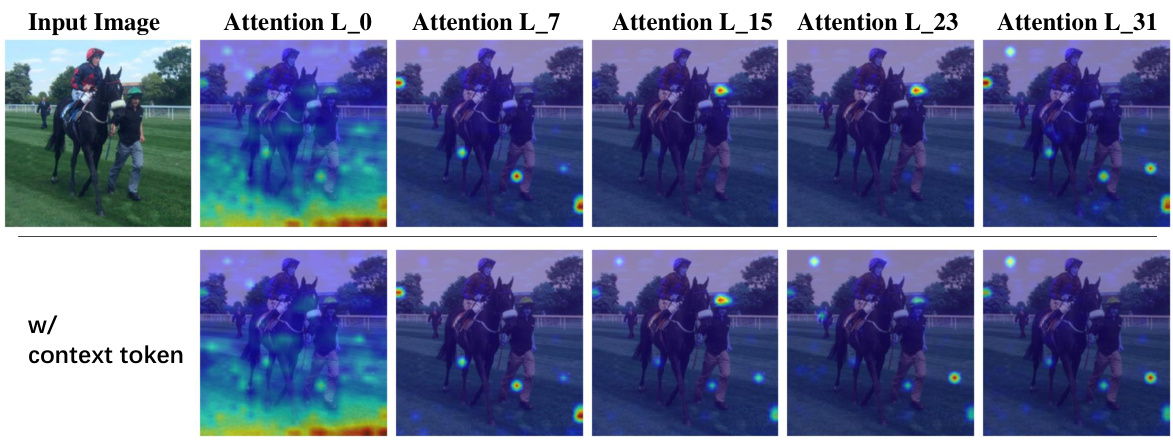

This figure shows the attention maps at different layers (L_0, L_7, L_15, L_23, L_31) of a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM). The top row displays the attention between the word ‘hat’ from the prompt and the visual tokens. The bottom row shows the attention between a context token (not specified in the caption) and the visual tokens. The attention maps highlight which parts of the image the model focuses on when processing the prompt. The varying attention patterns across different layers illustrate the multi-stage processing of the MLLM.

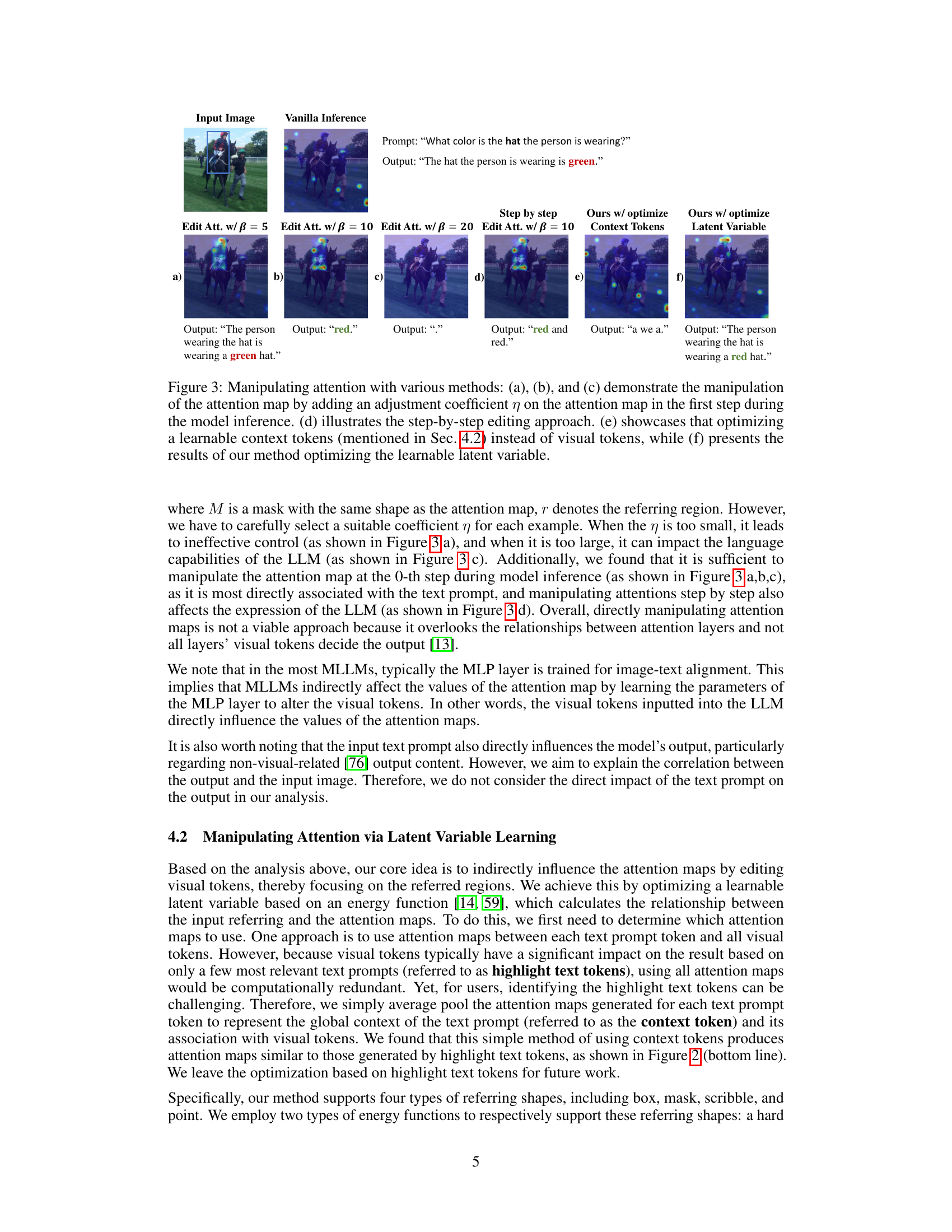

This figure compares different methods for manipulating attention in a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM). (a)-(c) show the impact of directly adjusting the attention map with varying strengths (β) of a coefficient. (d) demonstrates a step-by-step adjustment approach. (e) shows the effect of optimizing learnable context tokens. Finally, (f) presents the results of the authors’ proposed method using latent variable optimization.

This figure illustrates the training-free visual prompt learning method proposed in the paper. It shows how a visual prompt (e.g., a bounding box) is converted into a mask and used to compute a mask-based energy function. This function measures the relationship between the mask and a pooled attention map (an average pooling of attention maps from multiple layers of the Multimodal Large Language Model). Backpropagation is then used to optimize a learnable latent variable, which is added to the visual tokens before feeding into the LLM. This process is repeated multiple times (T iterations) at the 0th step of the inference process, allowing the model to effectively incorporate the visual prompt without retraining.

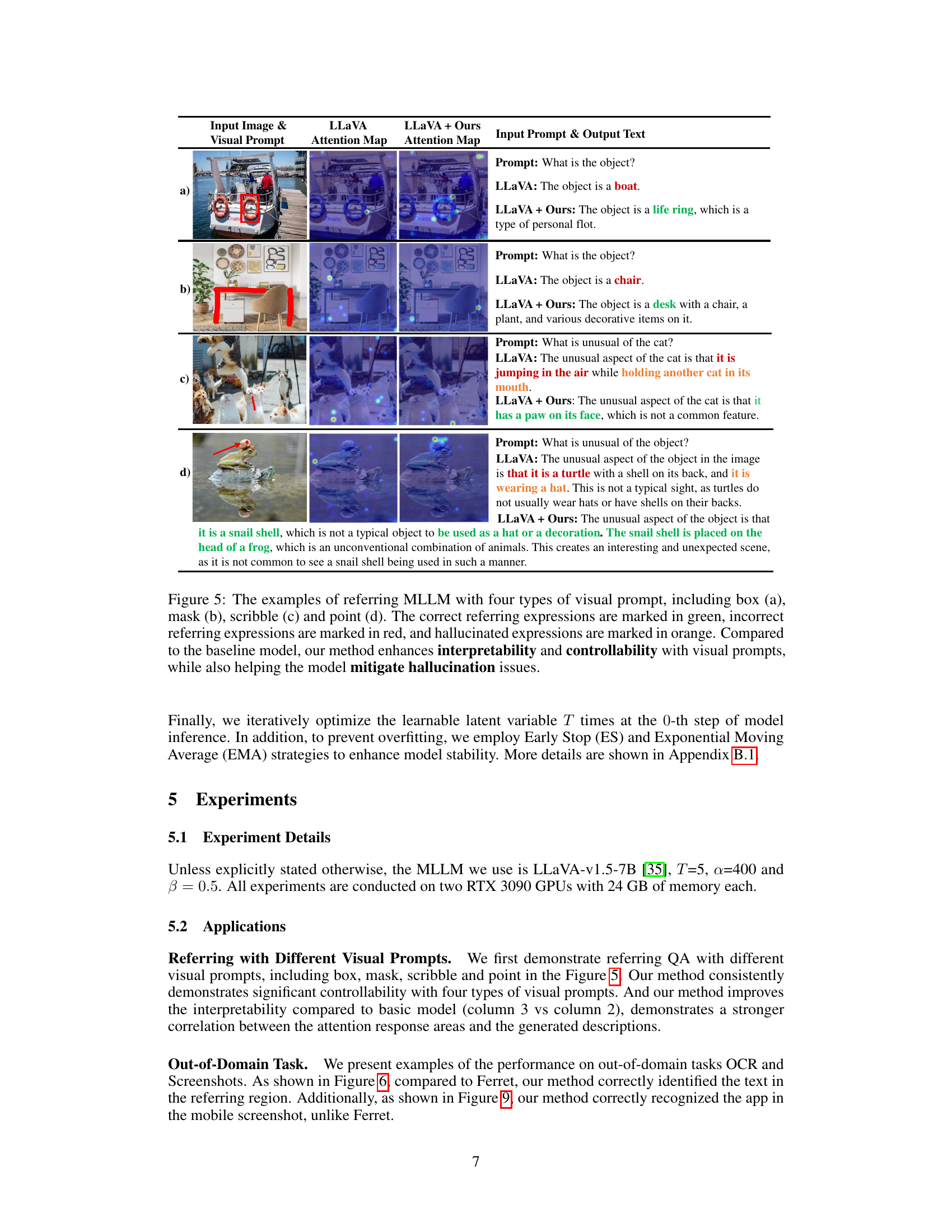

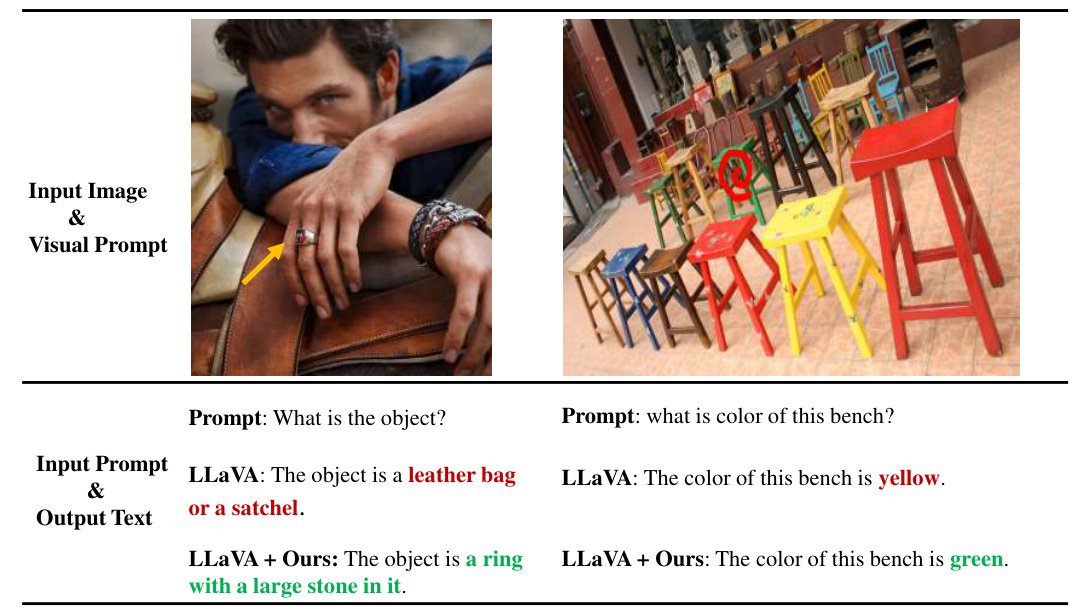

This figure showcases four examples of referring MLLMs using different visual prompt types: box, mask, scribble, and point. Each example includes the input image and visual prompt, attention maps from both the baseline LLaVA model and the proposed ControlMLLM method, and the corresponding output text. Correct, incorrect, and hallucinated output text are highlighted in green, red, and orange respectively. The figure demonstrates how the proposed method improves interpretability and controllability and reduces hallucinations when using visual prompts.

This figure compares traditional training-based multimodal large language model (MLLM) methods with the proposed training-free approach. Traditional methods require extensive in-domain data for training and struggle to adapt to unseen prompts or domains. The authors’ training-free method, however, is shown to readily handle prompts from new domains without additional training.

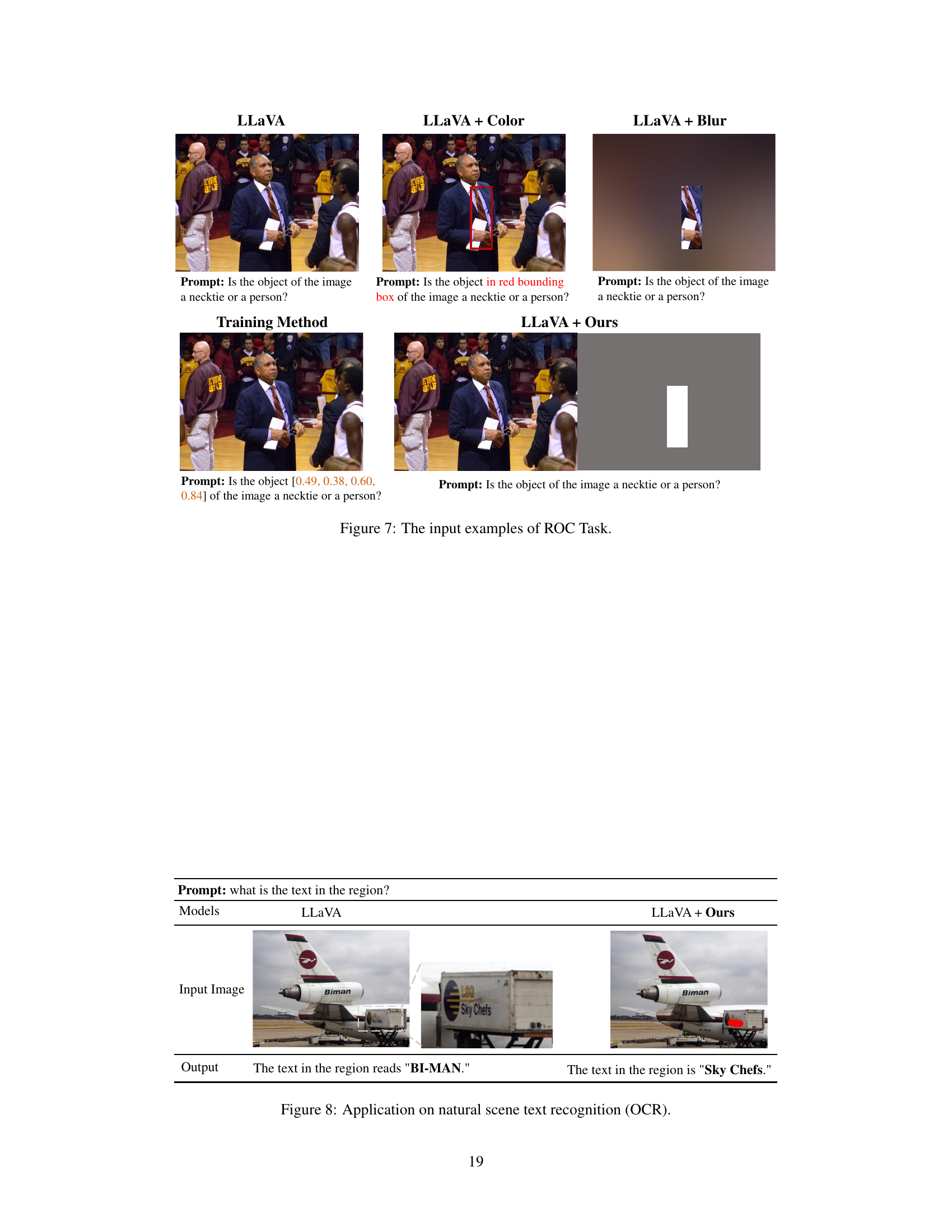

This figure shows input examples for the Referring Object Classification (ROC) task. It compares the performance of several methods: LLaVA, LLaVA + Color, LLaVA + Blur, and LLaVA + Ours. Each method is tested with different types of visual prompts: a simple question without a region specified, a question with a red bounding box around the region of interest, a blurred image with only the region of interest visible, and a question specifying the exact coordinates of the region. The goal is to evaluate how well each method can correctly classify the object within the specified region.

This figure shows four examples of referring expressions generated by a multimodal large language model (MLLM) using different types of visual prompts: box, mask, scribble, and point. The results demonstrate that the proposed training-free method improves the model’s ability to correctly identify and describe the referenced objects or regions within the image, reducing errors and hallucinations compared to the baseline model. The color coding highlights the correctness of the generated expressions (green: correct, red: incorrect, orange: hallucinated).

This figure shows the attention maps at different layers (L0, L7, L15, L23, L31) of a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM). The top row displays the attention between the word ‘hat’ in the prompt and the visual tokens. The bottom row shows the attention between a context token (not explicitly defined in the caption but implied by the image) and the visual tokens. The attention maps highlight which parts of the image the model focuses on when processing the prompt and context. This illustrates how the MLLM integrates visual and textual information.

This figure shows the results of using different sizes of visual prompts in the proposed method. It demonstrates that using a larger visual prompt results in improved performance. The larger prompt size likely provides more context for the model to understand the image, leading to better results.

This figure shows the attention maps at different layers of a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM). The top row highlights the attention between the word ‘hat’ from the prompt and the visual tokens, illustrating how the model focuses on relevant image regions. The bottom row displays the attention between a contextual token (not specified) and the visual tokens, showcasing a broader context understanding of the image. The different layers (L0, L7, L15, L23, L31) show how the attention shifts and refines as the model processes the information.

This figure compares the results of using either highlight text tokens or context tokens for the optimization process in the paper’s proposed training-free method for injecting visual prompts into Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). The table shows how the model’s output changes over multiple optimization steps (T=0 to T=5) when using the two different token types. It illustrates the impact of using averaged attention information (‘context tokens’) versus the attention from only the most relevant words (‘highlight tokens’) on the model’s ability to accurately describe the visual scene, specifically focusing on the relationship between textual prompts and visual context.

This figure compares different methods for manipulating attention in a multimodal large language model (MLLM). It shows how adding a coefficient to the attention map (a-c), step-by-step editing (d), optimizing learnable context tokens (e), and optimizing a learnable latent variable (f) affect the model’s output. The figure highlights the proposed method’s effectiveness in controlling attention and generating desired results.

This figure compares different methods of manipulating attention in a multimodal large language model (MLLM). It shows how adding a coefficient to the attention map (a-c), step-by-step editing (d), optimizing learnable context tokens (e), and optimizing a latent variable (f) impact the model’s output. The goal is to show the effectiveness of the proposed latent variable optimization method for controlling attention, thus improving the ability of the MLLM to focus on specific regions of interest within an image.

More on tables

This table presents the results of the Referring Text Classification task. The task evaluates the model’s ability to correctly identify whether the text within a specified region of an image matches text A or text B. The results are broken down by the method used, distinguishing between training methods and training-free methods. The table helps to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed training-free method in handling this task compared to various training-based methods.

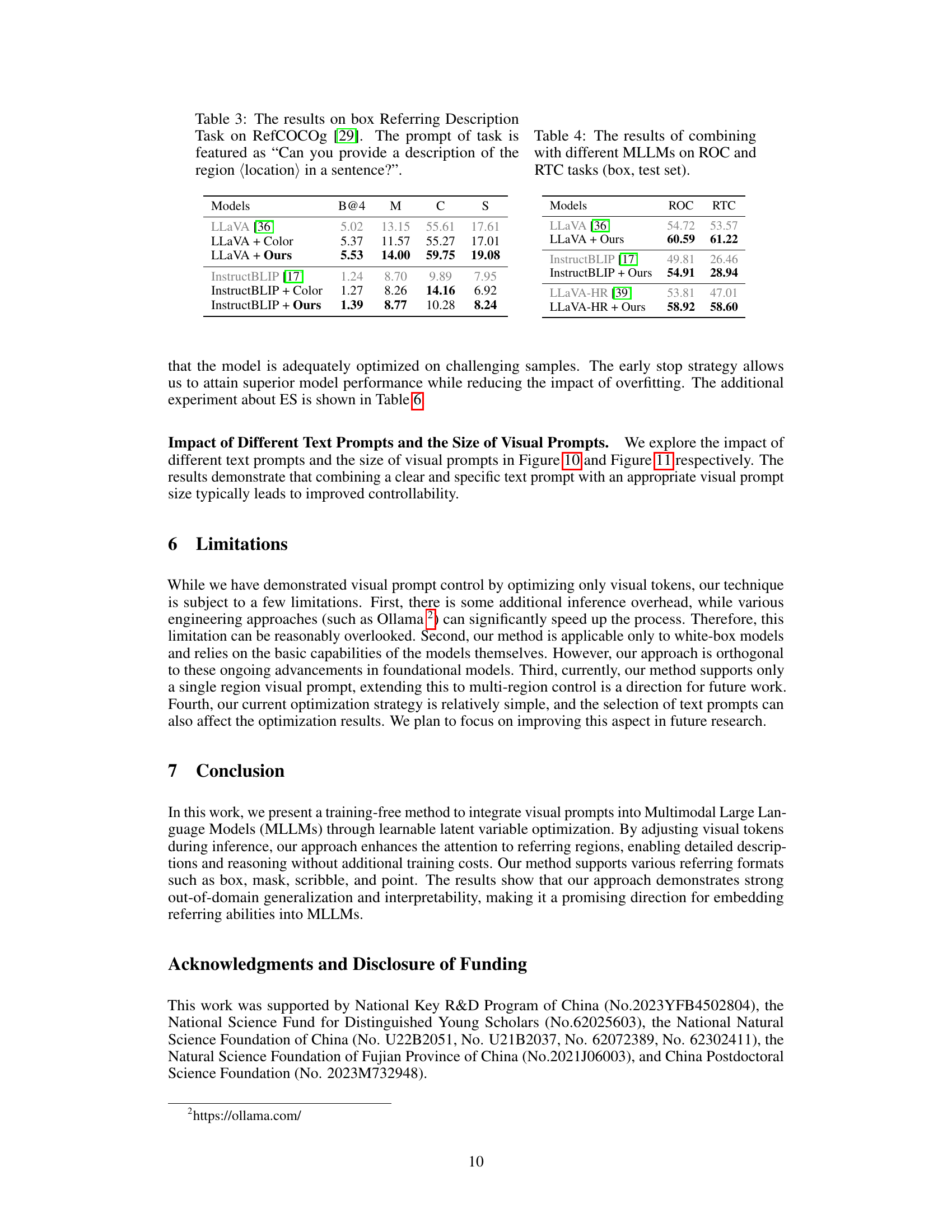

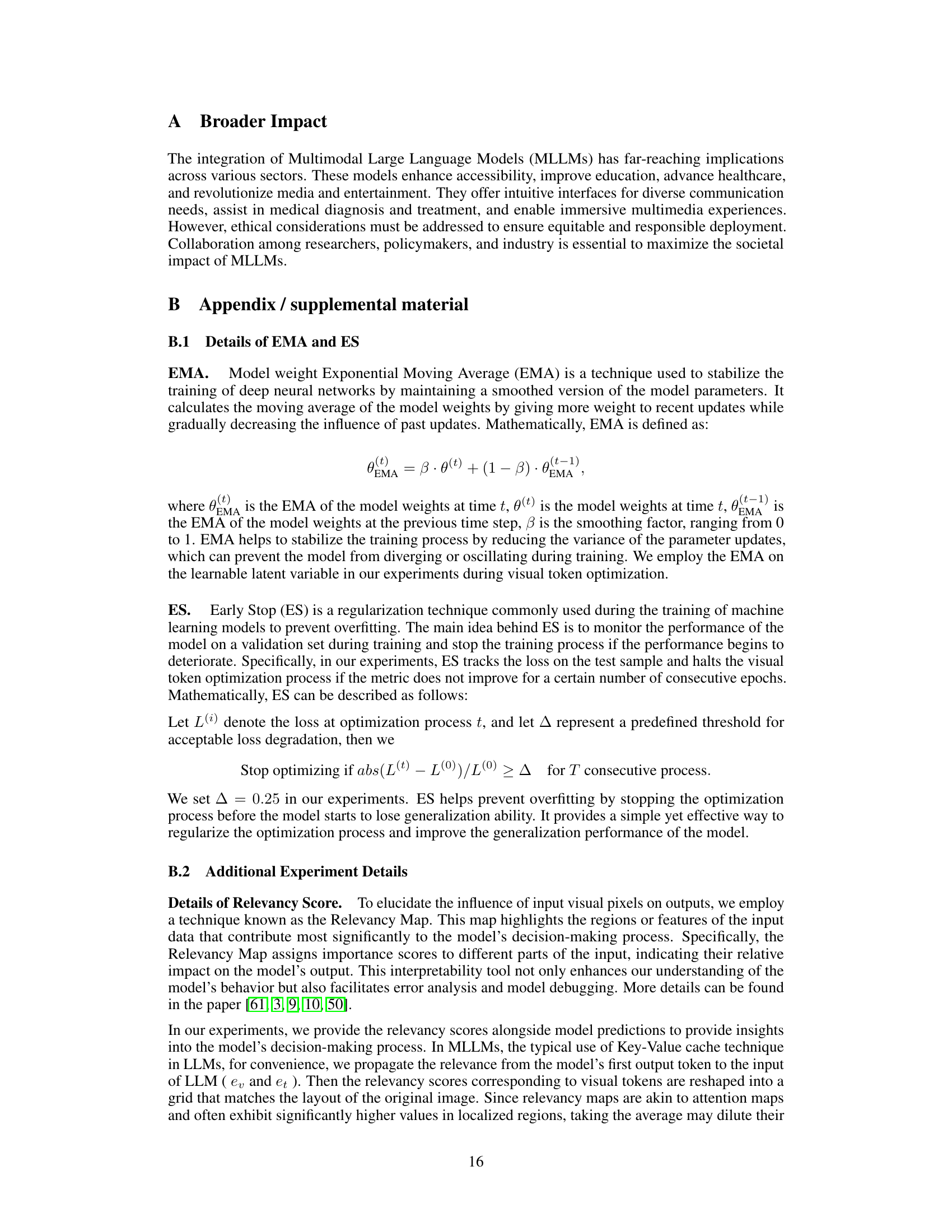

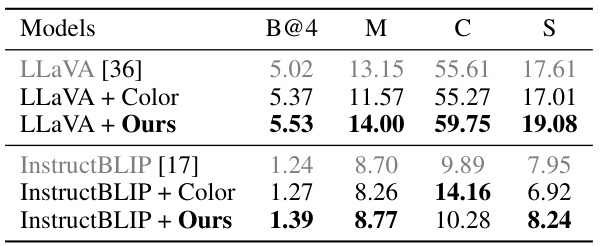

This table presents the results of the box Referring Description Task using the RefCOCOg dataset. The task is to generate a sentence describing a specific region of an image. The table compares the performance of the baseline LLaVA model, the LLaVA model with color added as visual prompt, and the LLaVA model with the proposed ControlMLLM method. The results are evaluated using four metrics: B@4, M, C, and S. Higher scores indicate better performance.

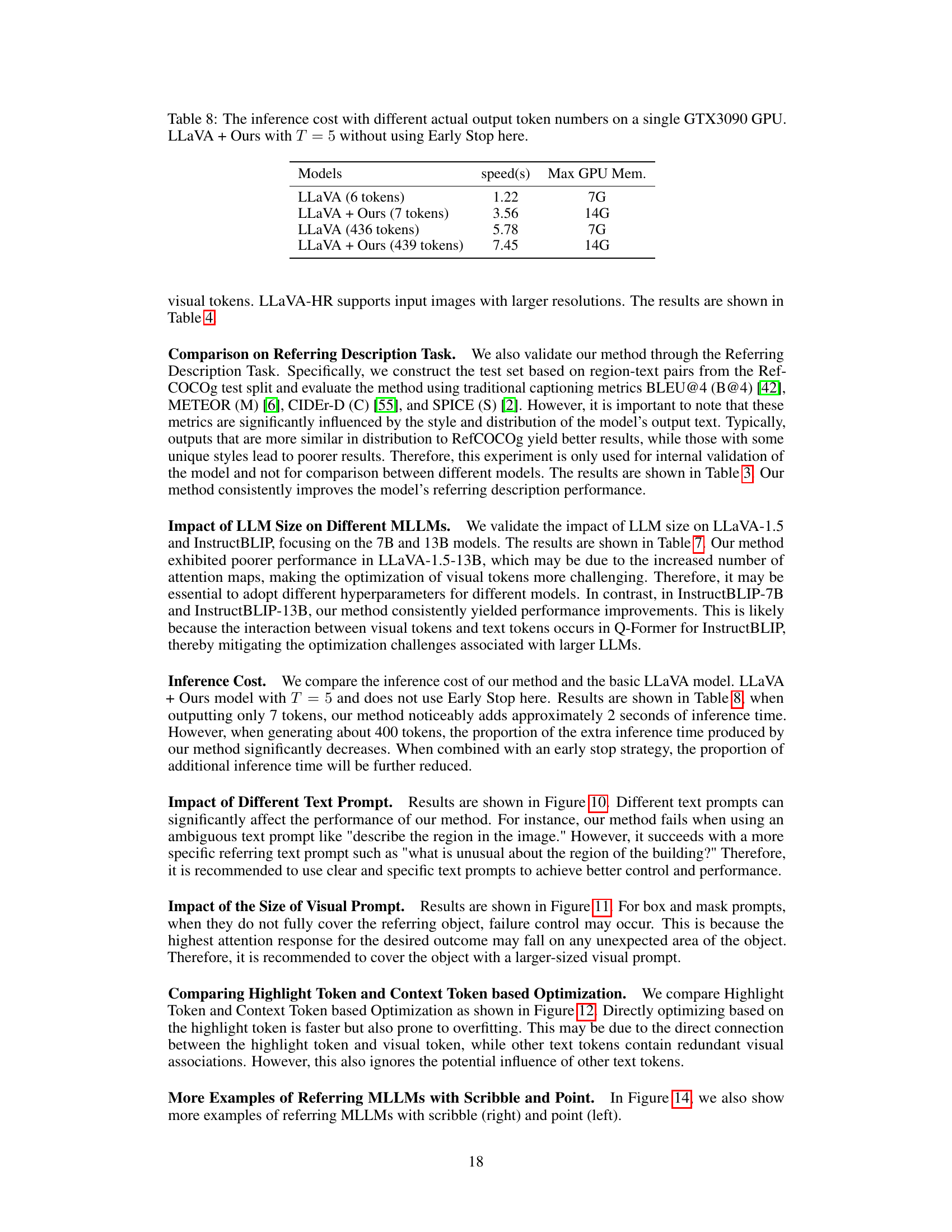

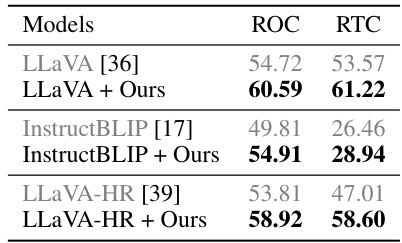

This table presents the results of applying the proposed training-free method to different Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for two distinct tasks: Referring Object Classification (ROC) and Referring Text Classification (RTC). It showcases the performance improvements achieved by the method on both tasks across various MLLMs using box-type visual prompts during testing. The table facilitates a comparison of the baseline MLLM performance with the performance enhancements obtained by incorporating the authors’ training-free method.

This table presents the results of the Referring Object Classification task, comparing various methods’ performance. The task involves determining whether an object at a specified location is of class A or class B. The table includes both training-based and training-free methods, highlighting the performance of the proposed method (‘LLaVA + Ours’) against state-of-the-art baselines. Results are presented for different types of referring expressions (box, mask, scribble, point). Grayed-out results indicate that a particular method does not support that referring type.

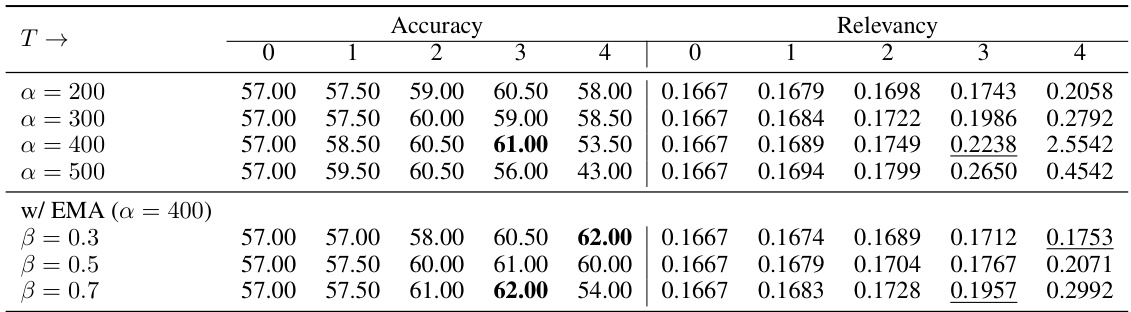

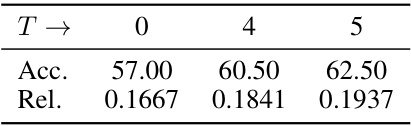

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of the early stopping (ES) technique on the model’s performance. The study varied the number of iterations (T) during the optimization process (0, 4, and 5), while keeping the hyperparameters alpha (α) and beta (β) constant. The table shows the accuracy (Acc.) and relevancy (Rel.) scores achieved in the validation set for each value of T. The relevancy score indicates the extent to which model output is influenced by visual content within the referring region. The results demonstrate how early stopping influences model performance, illustrating a tradeoff between accuracy and potential overfitting.

This table presents the results of the proposed method when combined with different Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) on two tasks: Referring Object Classification (ROC) and Referring Text Classification (RTC). The results are for the ‘box’ type of referring prompt, using test set data. It shows the performance improvement on ROC and RTC tasks achieved by the proposed training-free method compared to the baseline MLLMs (Vanilla). The higher the score indicates better performance.

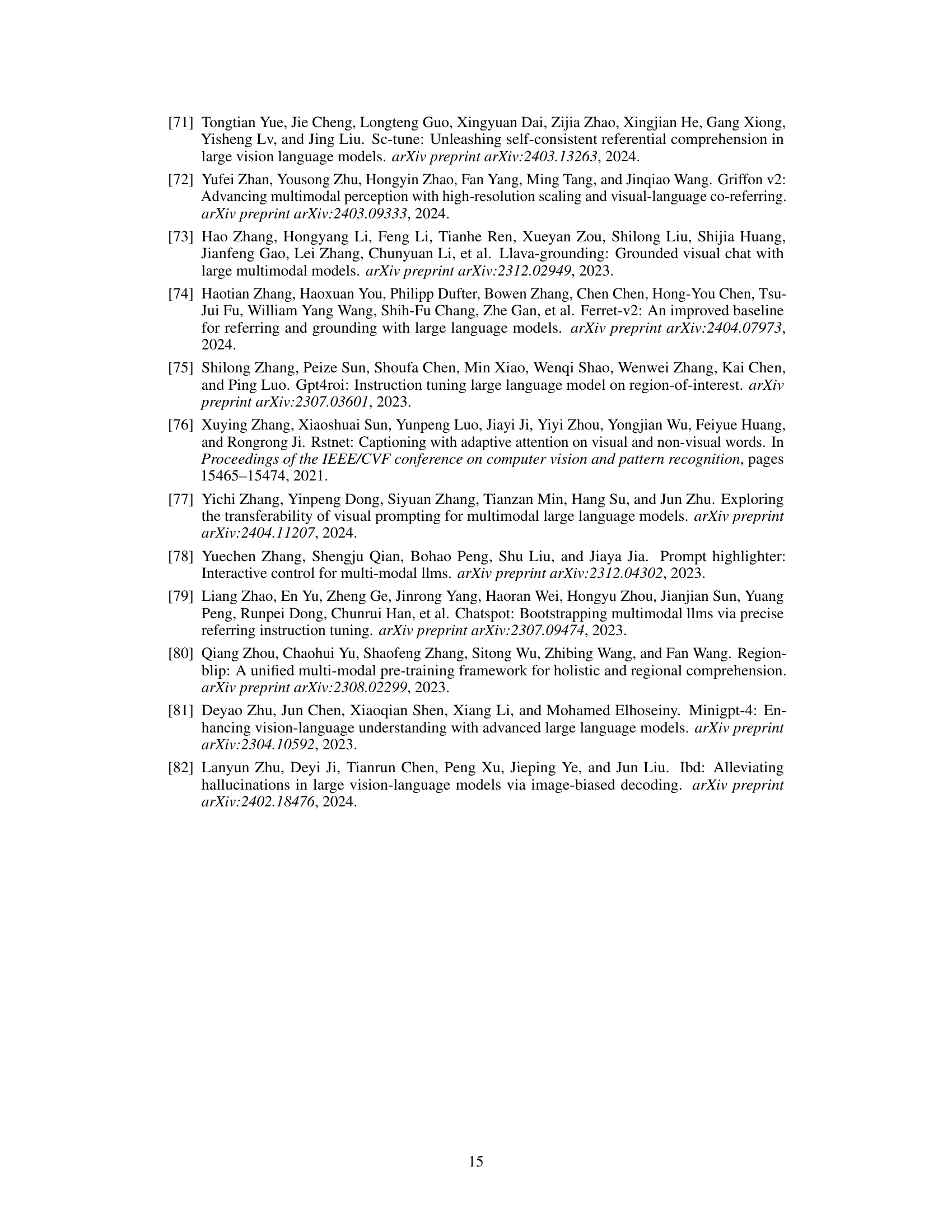

This table presents the inference time and maximum GPU memory usage for different model configurations. It compares the baseline LLaVA model with the proposed ControlMLLM method. The comparison is made for both a small number of output tokens (6 and 7) and a larger number of output tokens (436 and 439). The results show the increase in computation time and memory usage when using the proposed method, particularly with more tokens, demonstrating the trade-off between improved performance and computational cost. The absence of early stopping is noted, suggesting that the inference time could be further optimized with this strategy.

This table presents the results of the Referring Object Classification task on a test set. The task is a binary classification problem: given an image and a region of interest (specified by a box, mask, scribble, or point), determine whether the object in that region belongs to class A or class B. The table compares various methods—both training-based and training-free—evaluating their performance across different referring types. Training-free methods are particularly notable because they do not require additional training data for the referring task. The results are shown for different types of visual prompts, including boxes, masks, scribbles, and points, indicating which methods support each type. The table helps to assess how well different models and visual prompts perform on this fine-grained referential reasoning task.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on the Referring Object Classification task. The task is a binary classification problem where the model is asked to determine if an object at a specific location belongs to class A or class B. The table compares training-based methods and training-free methods, using different referring methods (box, mask, scribble, and point). The results indicate the accuracy of each method and show which methods do not support specific referring types. Results from a baseline model are provided for reference.

Full paper#