↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing controllers for complex fluid systems, especially those with dynamic boundaries (like artificial hearts or microfluidic devices), is notoriously difficult. Existing methods struggle with the interplay of fluid dynamics, solid mechanics, and optimization constraints. Traditional control algorithms, designed for solid systems, often fail to handle the infinite degrees of freedom inherent in fluid flows.

NeuralFluid offers a novel solution by integrating a fast, differentiable Navier-Stokes solver with a low-dimensional geometry representation and a control-shape co-design algorithm. This end-to-end differentiable framework allows gradient-based optimization, enabling efficient exploration of the design space and leading to designs and controllers that outperform gradient-free methods in various benchmark tasks. The framework’s Gym-like simulation environments make it easily accessible for researchers.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents NeuralFluid, a novel framework for designing and controlling complex fluidic systems. This addresses a significant challenge in various engineering and scientific fields by providing a fast differentiable Navier-Stokes solver and a co-design algorithm that enables efficient exploration of optimal designs and control strategies. The provided benchmark tasks and Gym-like environments also facilitate further research and development in fluidic control.

Visual Insights#

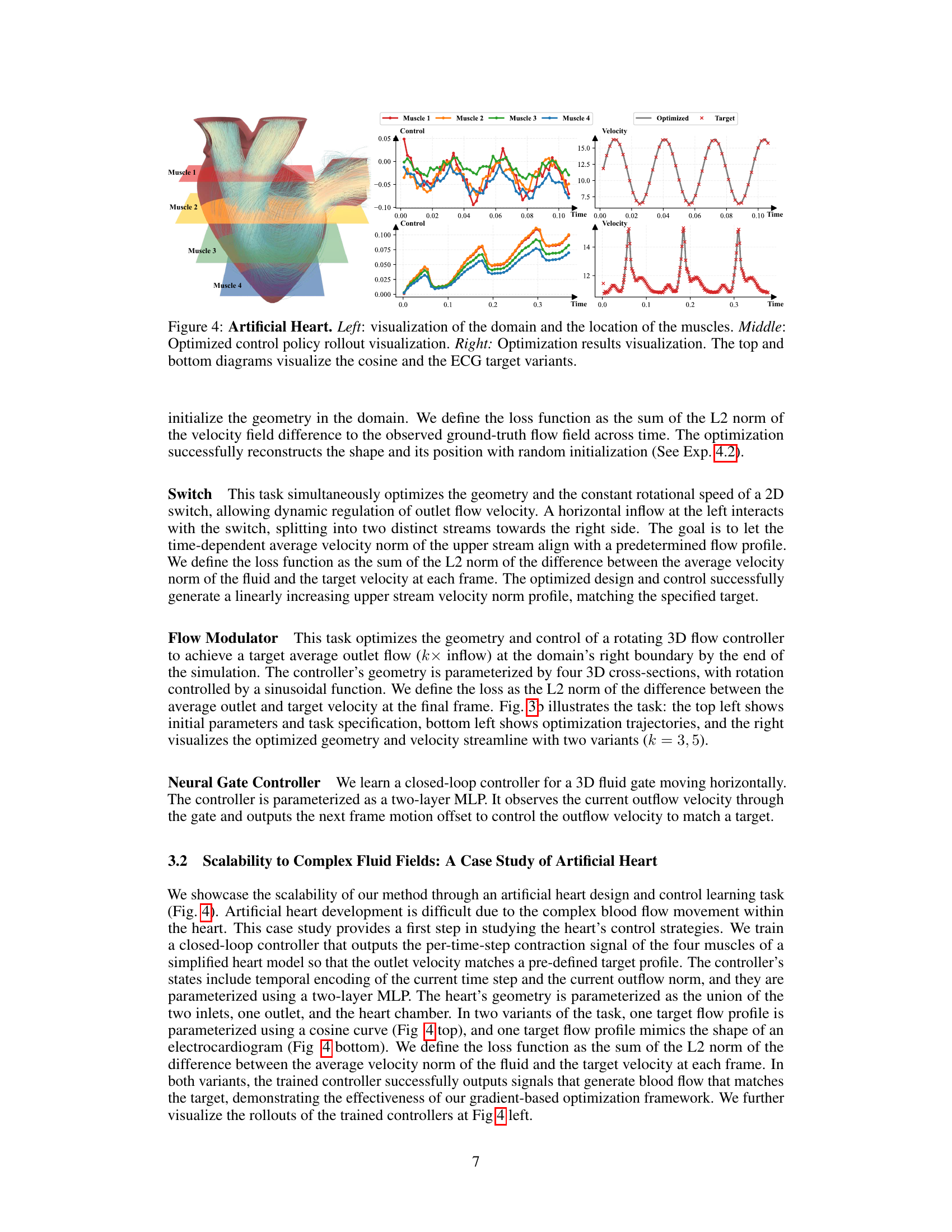

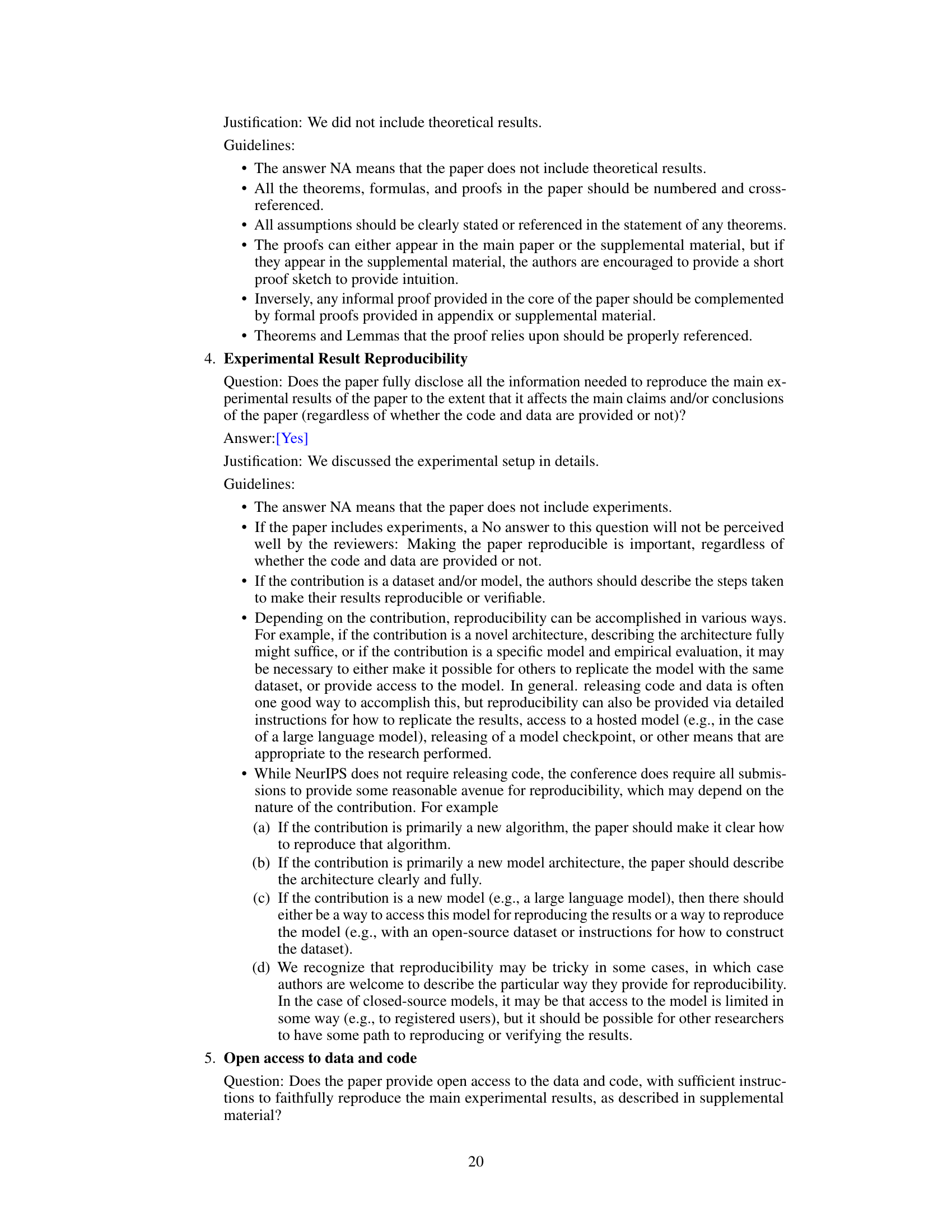

This figure demonstrates the artificial heart experiment. The left panel shows the domain and muscle locations. The middle panel visualizes the optimized control policy rollout. The right panel shows the optimization results, comparing the target and optimized outputs (cosine and ECG).

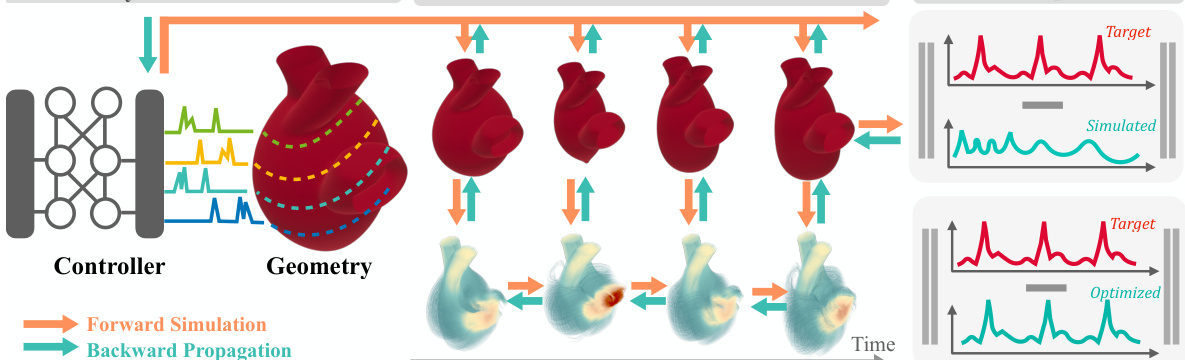

This table summarizes the simulation and optimization configurations for six different fluidic design tasks. For each task, it provides the resolution, number of frames simulated, number of parameters used in the geometry and control design, whether gradient-based optimization was used for both design and control, and the initial and optimized loss values. The note clarifies that the actual number of simulation steps is higher due to the CFL stability condition.

In-depth insights#

Diff. Fluid Solver#

A differentiable fluid solver is a crucial component for enabling gradient-based optimization in fluid dynamics simulations. Its differentiability allows for the computation of gradients through the simulation, enabling the optimization of various design parameters or control strategies. The accuracy of this solver is paramount, as inaccurate gradients can lead to ineffective or unstable optimization processes. Efficient implementation is also critical, as differentiable fluid simulations can be computationally expensive, especially for high-resolution simulations. The solver should handle complex boundary conditions and fluid-solid interactions accurately and efficiently, to model realistic scenarios. The design of a robust differentiable fluid solver requires careful consideration of numerical methods, discretization schemes, and stability analysis. Its speed significantly impacts the overall optimization workflow. Therefore, balancing accuracy and computational cost is essential in the development of a practical differentiable fluid solver for use in applications such as fluidic system design, control and optimization.

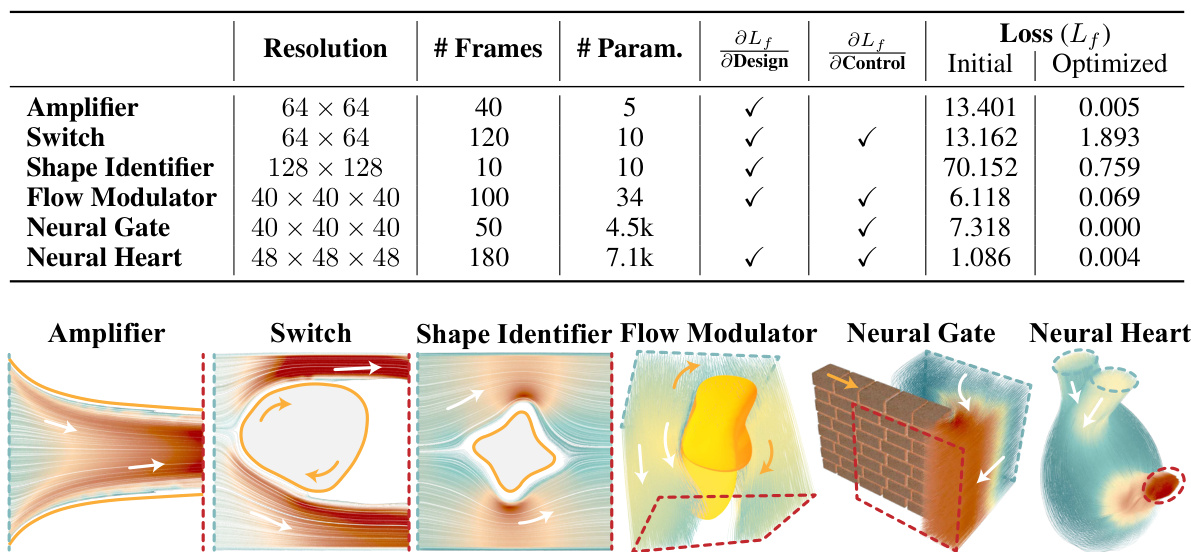

NeuralFluid Design#

NeuralFluid Design presents a novel framework for designing and controlling complex fluidic systems with dynamic boundaries, leveraging differentiable simulation. It introduces a low-dimensional, differentiable parametric geometry representation for efficient shape exploration, coupled with a fast, differentiable Navier-Stokes solver capable of handling fluid-solid interactions. A key aspect is the co-design algorithm, which simultaneously optimizes both the geometry and control policies. The framework is validated through benchmark tasks, demonstrating successful design, control, and learning results that surpass gradient-free methods. Differentiability is key to the approach, enabling gradient-based optimization for efficient exploration of the design space. This method excels in handling the complex interplay between geometry, control, and dynamic fluid behavior, making it a powerful tool for designing advanced fluidic systems with applications in robotics and engineering. The work significantly advances differentiable fluid simulation and neural control, paving the way for more sophisticated designs of complex fluid-structure interaction systems.

Co-design Method#

A co-design method, in the context of fluidic systems, seamlessly integrates neural network controllers with differentiable fluid simulations. This approach allows for simultaneous optimization of both the geometry of the system and its control parameters. The framework likely leverages gradient-based optimization techniques, enabling efficient exploration of the combined design space. Differentiable physics simulation is crucial, allowing the computation of gradients through the fluid dynamics, facilitating co-optimization by backpropagating errors from simulation outputs to both geometry and controller parameters. A key advantage is the ability to move beyond traditional, gradient-free optimization approaches, which often struggle with the high dimensionality and complexity inherent in fluidic systems. The method’s success hinges on the accuracy and efficiency of the underlying differentiable Navier-Stokes solver and its ability to handle complex solid-fluid interfaces. It is expected that the co-design approach results in superior performance compared to separate design and control optimization strategies. This is made possible by explicitly accounting for the interactions between geometry and control within the optimization process.

Benchmark Tasks#

The benchmark tasks section of a research paper is crucial for evaluating the proposed method’s effectiveness and generalizability. A strong benchmark should include tasks that are challenging yet representative of real-world applications. The tasks should push the boundaries of existing methods and highlight the unique strengths of the new approach. Ideally, the tasks would vary in complexity and data characteristics to demonstrate robustness across diverse scenarios. Quantitative metrics are essential to objectively measure the performance across these tasks and facilitate comparisons with existing state-of-the-art techniques. Qualitative analysis may also be beneficial to explain unexpected results and provide deeper insights. Proper task selection is critical; selecting overly simplistic tasks will not fully assess capabilities, while exceedingly complex tasks could overshadow the true contributions. The choice of benchmark tasks significantly influences the paper’s impact and credibility, requiring meticulous consideration.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize extending NeuralFluid’s capabilities to handle non-Newtonian fluids and complex multi-physics interactions, moving beyond the limitations of the Navier-Stokes model for Newtonian fluids. Addressing the challenges of high-dimensional or discontinuous parameterizations in complex design spaces is crucial, potentially by exploring alternative optimization techniques or incorporating surrogate models for more efficient exploration. Validating the pipeline against real-world physical experiments is essential to establish its reliability and generalizability. Investigating the impact of different numerical methods and their inherent limitations on both accuracy and computational cost will further enhance NeuralFluid’s robustness and efficiency. Finally, exploring the potential for closed-loop control with complex, adaptive controllers and applying it to more realistic and challenging benchmark applications will strengthen its practical value.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure provides a visual overview of six different fluidic design and control tasks explored in the paper. Each task is illustrated with a schematic showing the inlet and outlet, flow direction, and the initial geometry of the system being controlled. The tasks include amplifying flow, controlling a switch, identifying shapes, modulating flow, controlling a neural gate, and controlling an artificial heart. The diagrams visually highlight the key components and the goal of each task.

This figure provides a visual overview of six different fluidic design and control tasks explored in the paper. Each task is illustrated with a diagram showing the inlet, outlet, flow direction, and the shape and motion of the relevant geometry. These tasks serve as benchmarks for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed NeuralFluid framework.

This figure shows an overview of six different fluidic design and control tasks. Each task is visually represented with a schematic diagram, illustrating the inlet and outlet positions, flow direction, and the geometry being manipulated. The tasks demonstrate the versatility of the NeuralFluid framework in addressing various fluid control challenges, including amplification, switching, shape identification, flow modulation, neural gating, and artificial heart control.

This figure visualizes the results of applying the NeuralFluid framework to the design and control of an artificial heart. The left panel shows a 3D model of the artificial heart, highlighting the placement of four muscles that control blood flow. The middle panel displays the optimized control signals for each muscle over time, showing how they work together to achieve the desired heart function. The right panel compares the resulting velocity of blood flow to a target pattern, demonstrating the effectiveness of the optimized control signals. The top and bottom plots on the right-hand side showcase results using a cosine waveform and an electrocardiogram (ECG) as the target flow pattern, respectively.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of initialization and compare the performance of the gradient-based method with gradient-free optimization techniques. The left panel shows optimization trajectories for a neural heart model with 7100 parameters across five different random initializations, highlighting the robustness of the method to initial conditions. The right panel shows the log-scaled loss-iteration curves for the gradient-based method and two gradient-free methods (PPO and CMA-ES) on the Neural Heart task, demonstrating the superior convergence rate of the proposed gradient-based approach.

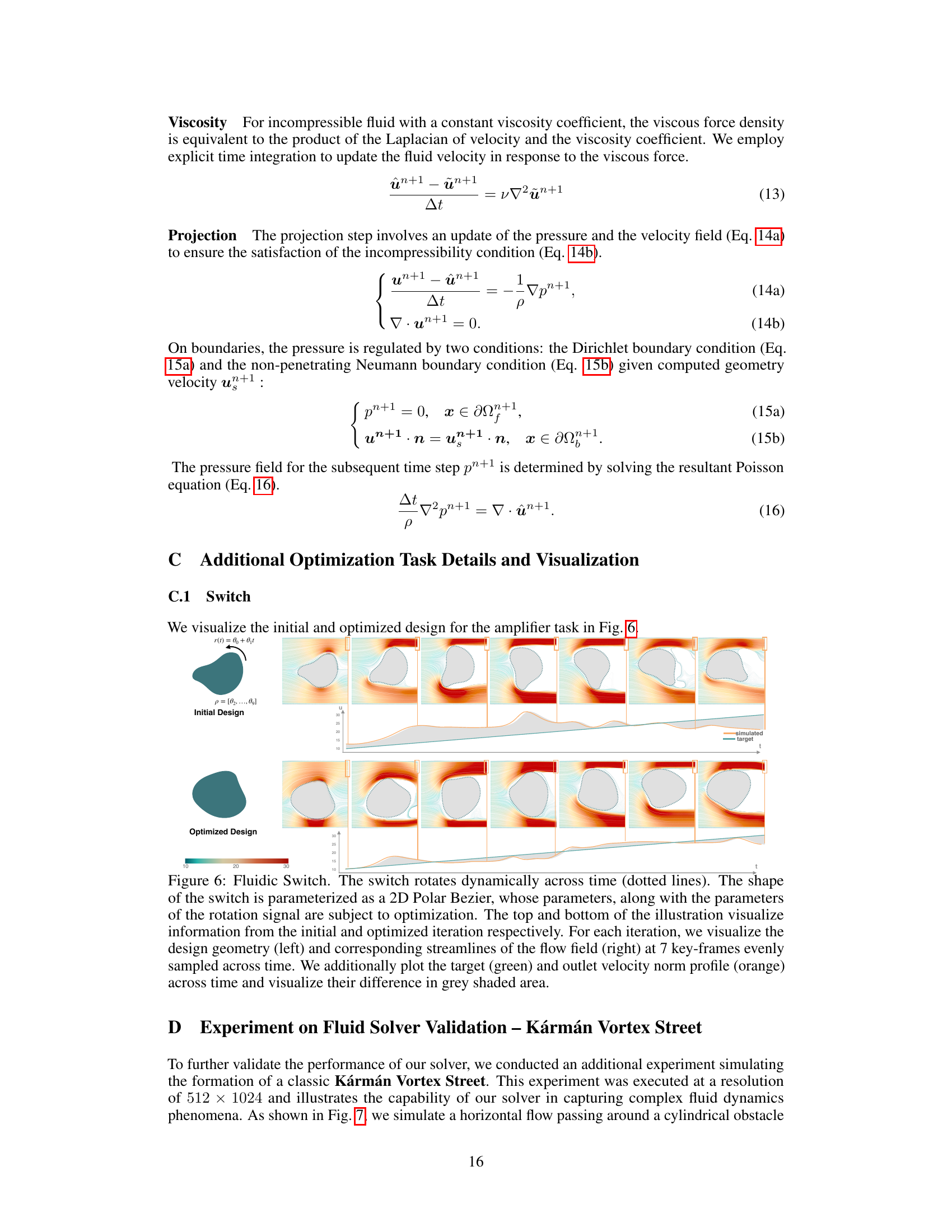

This figure shows the initial and optimized design for the fluidic switch task. The switch’s shape is parameterized using a 2D polar Bézier curve, and its rotation speed is controlled by a time-dependent signal. The top and bottom halves show the initial and optimized designs respectively. For each design, streamlines of the flow field are shown at 7 keyframes. Plots below show the simulated and target outlet velocity profiles over time.

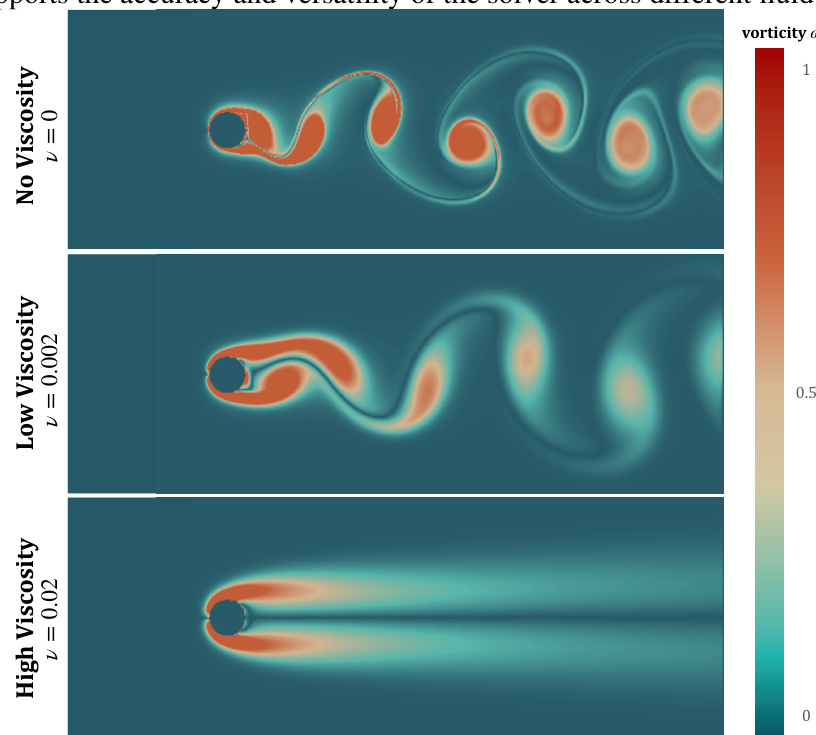

This figure shows the results of a simulation of the Kármán vortex street phenomenon under three different kinematic viscosity values (0.0, 0.002, and 0.02). The simulation uses a differentiable solver and demonstrates the impact of viscosity on vortex formation and dissipation.

More on tables

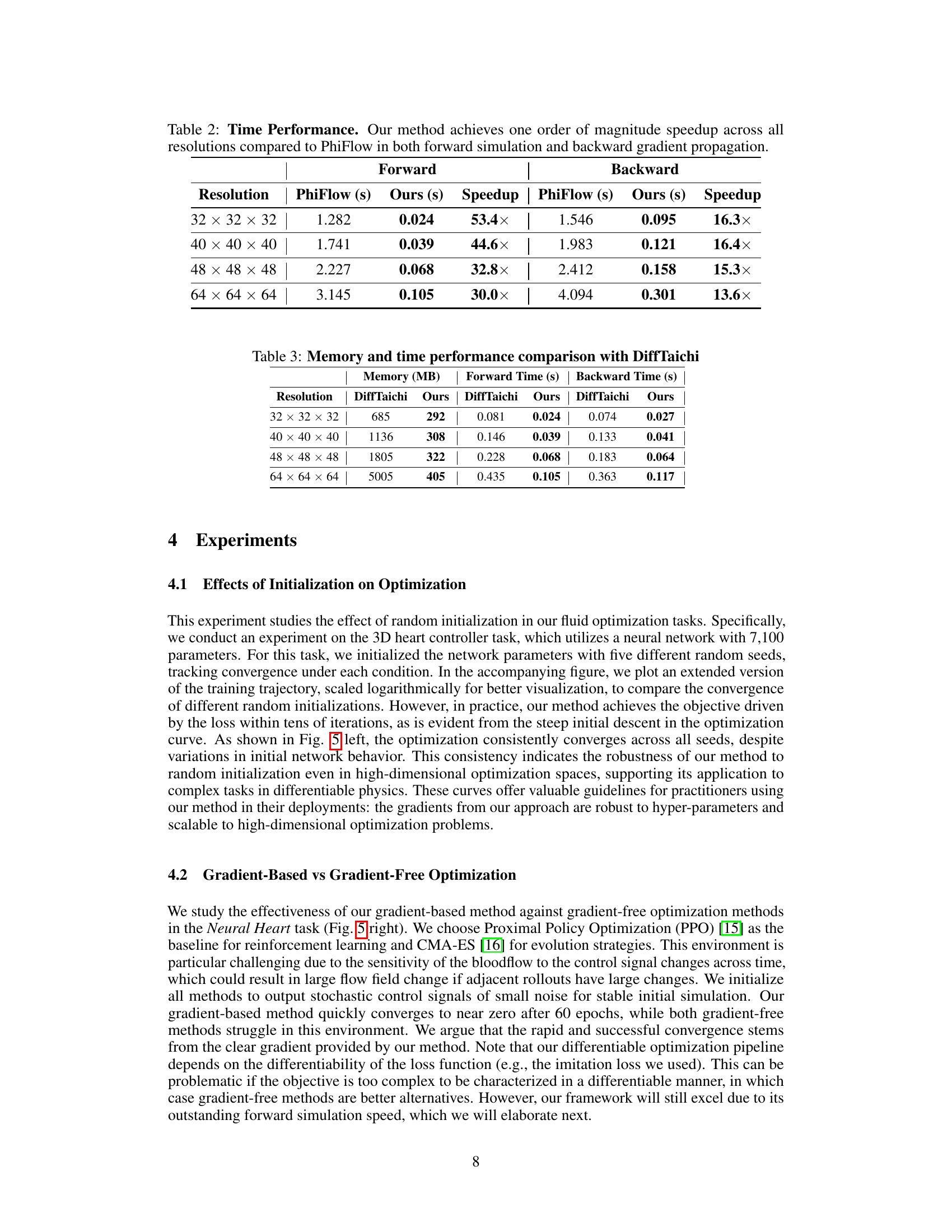

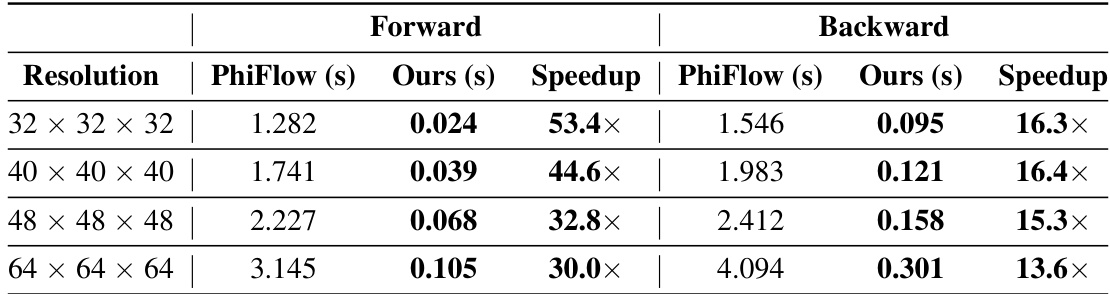

This table compares the computation time of forward simulation and backward gradient propagation between the proposed method (Ours) and PhiFlow across different resolutions (32x32x32, 40x40x40, 48x48x48, and 64x64x64). It demonstrates that the proposed method significantly outperforms PhiFlow in terms of speed, achieving speedups ranging from 13.6x to 53.4x for forward simulation and 15.3x to 16.4x for backward propagation.

This table compares the memory usage (in MB) and computation time (in seconds) for both forward and backward passes of the NeuralFluid simulator against the DiffTaichi framework. The comparison is shown across four different resolutions (32x32x32, 40x40x40, 48x48x48, and 64x64x64), highlighting the memory efficiency and speed advantage of the NeuralFluid simulator.

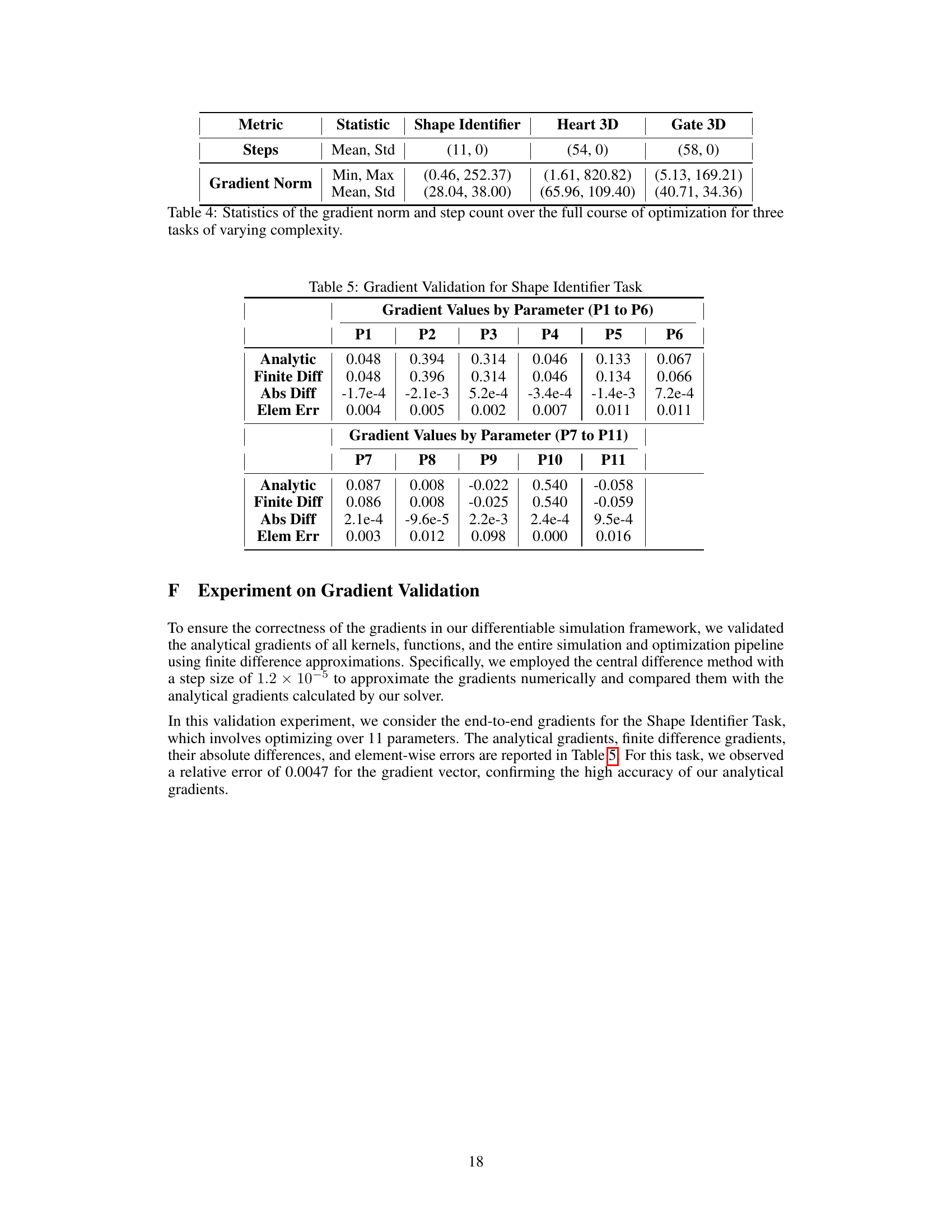

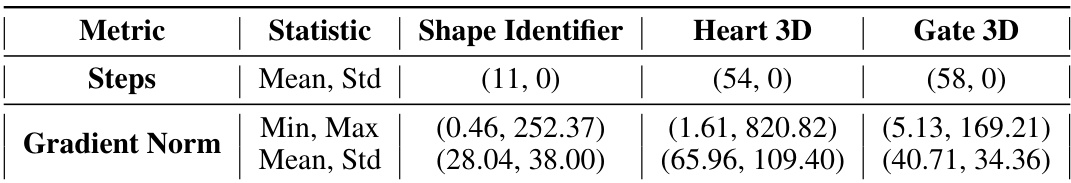

This table presents a statistical summary of gradient norms and the number of solver steps during the optimization process for three benchmark tasks: Shape Identifier, Heart 3D, and Gate 3D. For each task, it provides the mean and standard deviation of the number of steps and gradient norms. Additionally, it shows the minimum and maximum gradient norm values encountered during optimization. This data gives insights into the stability and efficiency of the optimization algorithm across different levels of complexity.

This table summarizes the simulation and optimization configurations used for six different fluidic design tasks presented in Section 3 of the paper. It shows the resolution of the simulation, the number of frames simulated, the number of parameters used in the optimization, whether design and/or control was optimized, and the initial and final loss values for each task. It also notes that the number of simulated and back-propagated frames might be higher than explicitly stated due to the CFL condition ensuring numerical stability.

Full paper#