↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

In-context learning (ICL) allows large language models (LLMs) to perform tasks using only examples and instructions. However, how LLMs achieve this remains poorly understood. Many previous works treated LLMs as black boxes and focused on improving ICL through surface-level interventions like prompt engineering. This paper focuses on the internal mechanism of ICL to determine where the task is encoded and attention to context is no longer needed. This is important since many researchers focus on prompt engineering without fully understanding the internal mechanism.

The researchers employed a novel layer-wise context-masking technique to investigate the internal mechanism of in-context learning. They conducted experiments on several LLMs across machine translation and code generation tasks, revealing a “task recognition” layer where the task is encoded. This finding enabled a significant reduction in computational cost by up to 45% because subsequent layers become redundant after the task recognition point. The study also demonstrated differences across various LLMs and task types.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it provides insights into the inner workings of in-context learning. Understanding where and how LLMs process contextual information will lead to more efficient models and open up new avenues of research for optimization and improving resource management. It also challenges existing assumptions about in-context learning by suggesting a model for how the task recognition happens in the model.

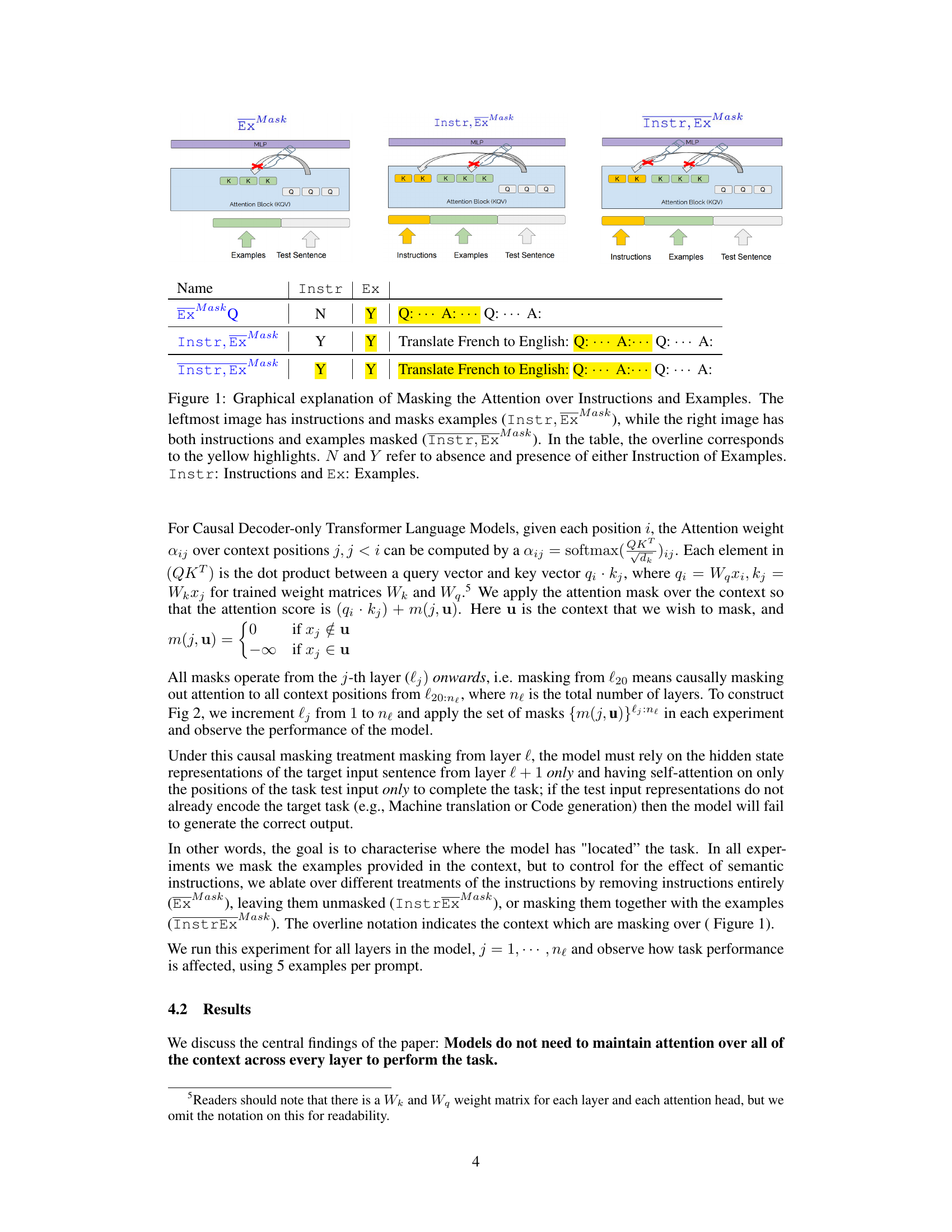

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates how the attention mechanism in transformer language models can be masked to study the effect of removing context (instructions or examples) from a certain layer in the network. Three masking scenarios are shown: the first masks only examples, the second masks both instructions and examples, and the third masks only instructions. The yellow highlights in the diagrams correspond to the masked sections. The table summarizes the presence (Y) or absence (N) of instructions and examples in each masking scenario.

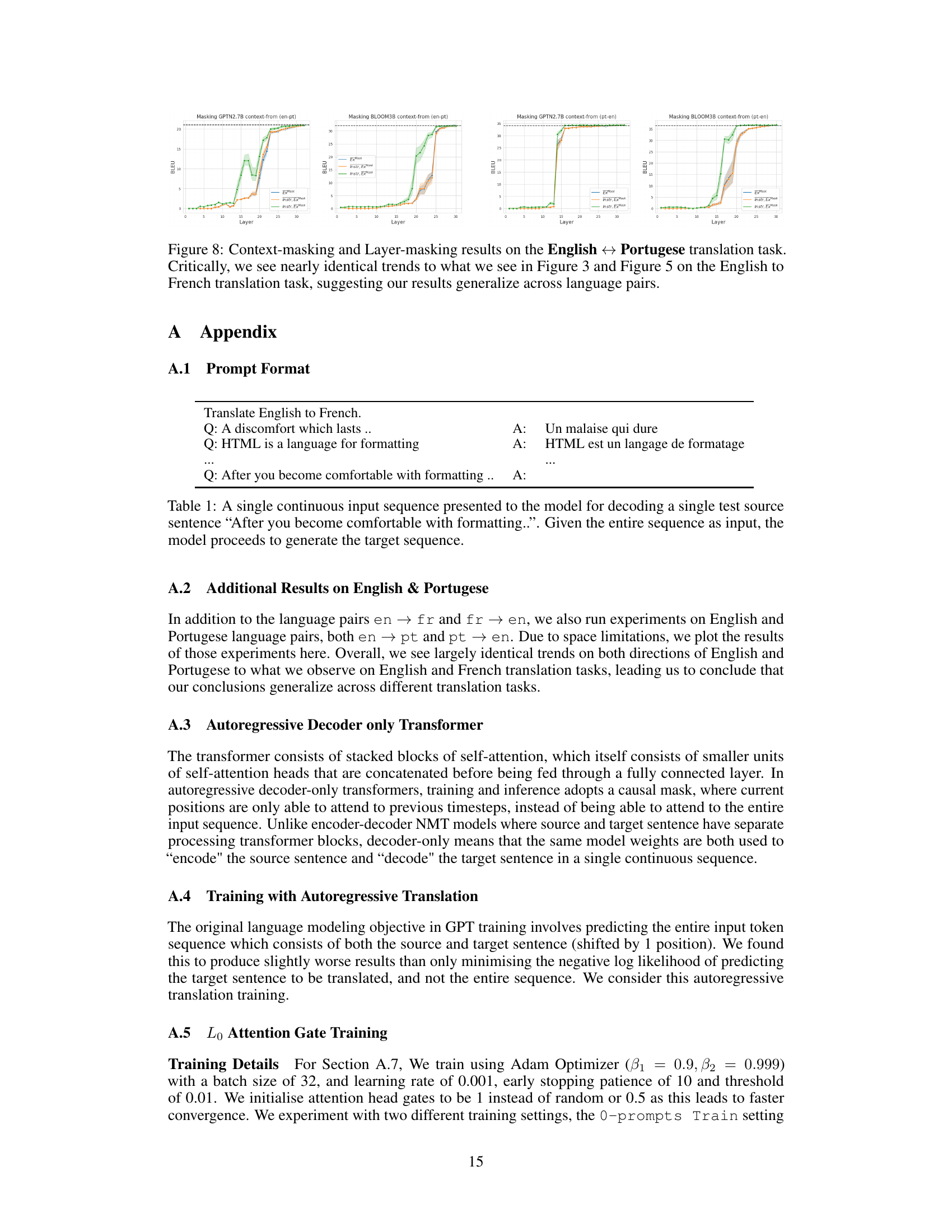

This table shows an example of a single continuous input sequence used for prompt examples in machine translation. The model receives the entire sequence as input and is expected to generate the target sequence.

In-depth insights#

In-context Learning#

In-context learning (ICL) is a fascinating phenomenon where large language models (LLMs) perform tasks not explicitly trained for, by utilizing examples presented within the input context. This ability to learn from demonstrations rather than explicit training data has revolutionized how we approach NLP tasks. The paper delves into understanding the location of ICL within the LLM architecture, discovering a “task recognition” point where the model transitions from identifying the task to performing it. This implies a division of labor within the neural network, with certain layers prioritizing task comprehension while others execute it. The research cleverly uses layer-wise masking to identify this critical layer, shedding light on the underlying mechanisms and offering significant potential for computational optimization. By identifying redundant layers, the process can be significantly sped up, which is vital in deploying these resource-intensive models in practical applications. Ultimately, this research moves beyond treating LLMs as black boxes and provides crucial insight into their internal functionality, paving the way for more efficient and effective use of these powerful tools.

Layer-wise Masking#

Layer-wise masking is a crucial technique employed to investigate the internal mechanisms of in-context learning within large language models. By systematically masking or removing attention weights at different layers, researchers gain insights into where and how tasks are recognized and processed. This method helps determine the critical layers responsible for task encoding before execution begins, separating the task identification stage from the execution phase. The approach allows researchers to observe how model performance changes as layers are masked, revealing layers that are essential for task comprehension and those with redundant computations. Identifying task-critical layers allows for computational optimization by eliminating unnecessary layers in the model without significantly impacting performance. This approach significantly contributes to a deeper understanding of the black-box nature of LLMs and their internal workings, facilitating improved model design and efficiency.

Task Recognition#

The concept of “Task Recognition” in the context of large language models (LLMs) is crucial. It refers to the point where the model successfully identifies the task it’s supposed to perform, transitioning from interpreting the prompt and examples to actually executing the task. This recognition isn’t a singular event but rather a process occurring across multiple layers of the model. The paper investigates this by masking attention weights to context at different layers, revealing a critical layer range where task performance is highly sensitive to the context. Beyond this point, the model can seemingly perform the task even without fully attending to the input context, suggesting the task has been successfully encoded into internal representations. This is a significant finding with strong implications for computational efficiency and model design. The identification of a specific layer or set of layers responsible for task recognition opens new avenues for optimizing model architecture and reducing redundant computations. This work highlights that LLM understanding goes beyond simple pattern matching and moves into the realm of nuanced task interpretation and execution.

Inference Efficiency#

The study’s section on “Inference Efficiency” presents a compelling argument for optimizing large language model (LLM) inference. By identifying the “task recognition point”—the layer in the model where the task is encoded, and further processing of the context is no longer crucial—the authors propose substantial computational savings. This is achieved by strategically masking out attention weights to the context after the task recognition layer, eliminating redundant computations. Significant speedups are possible, as demonstrated by the 45% efficiency gain in LLAMA7B. The findings highlight the potential for efficient LLM deployment in resource-constrained environments, opening avenues for developing faster and more cost-effective applications. Furthermore, the approach directly addresses the challenge of long context windows, a prevalent issue in LLM processing, by allowing models to ignore unnecessary input information after the task recognition point. The work’s implication is that we may not need to process the entire context through the full depth of the model for every task. This opens doors to future development in speeding up the inference time, without sacrificing performance.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore the generalizability of the findings across a wider range of language models and tasks. Investigating the impact of model architecture and training data on the location of task recognition would provide valuable insights. Furthermore, a deeper investigation into the redundancy of different layers and attention heads is warranted. This could involve developing more sophisticated methods for identifying and quantifying redundancy, potentially leading to significant improvements in model efficiency. Theoretical frameworks are needed to explain the observed phenomena of task recognition and layer redundancy. Such frameworks could leverage insights from cognitive science and machine learning theory. Finally, research should address the implications of these findings for prompt engineering and other techniques aimed at improving the effectiveness of large language models. Understanding how task recognition interacts with prompt design could lead to more effective and efficient methods for utilizing these powerful tools.

More visual insights#

More on figures

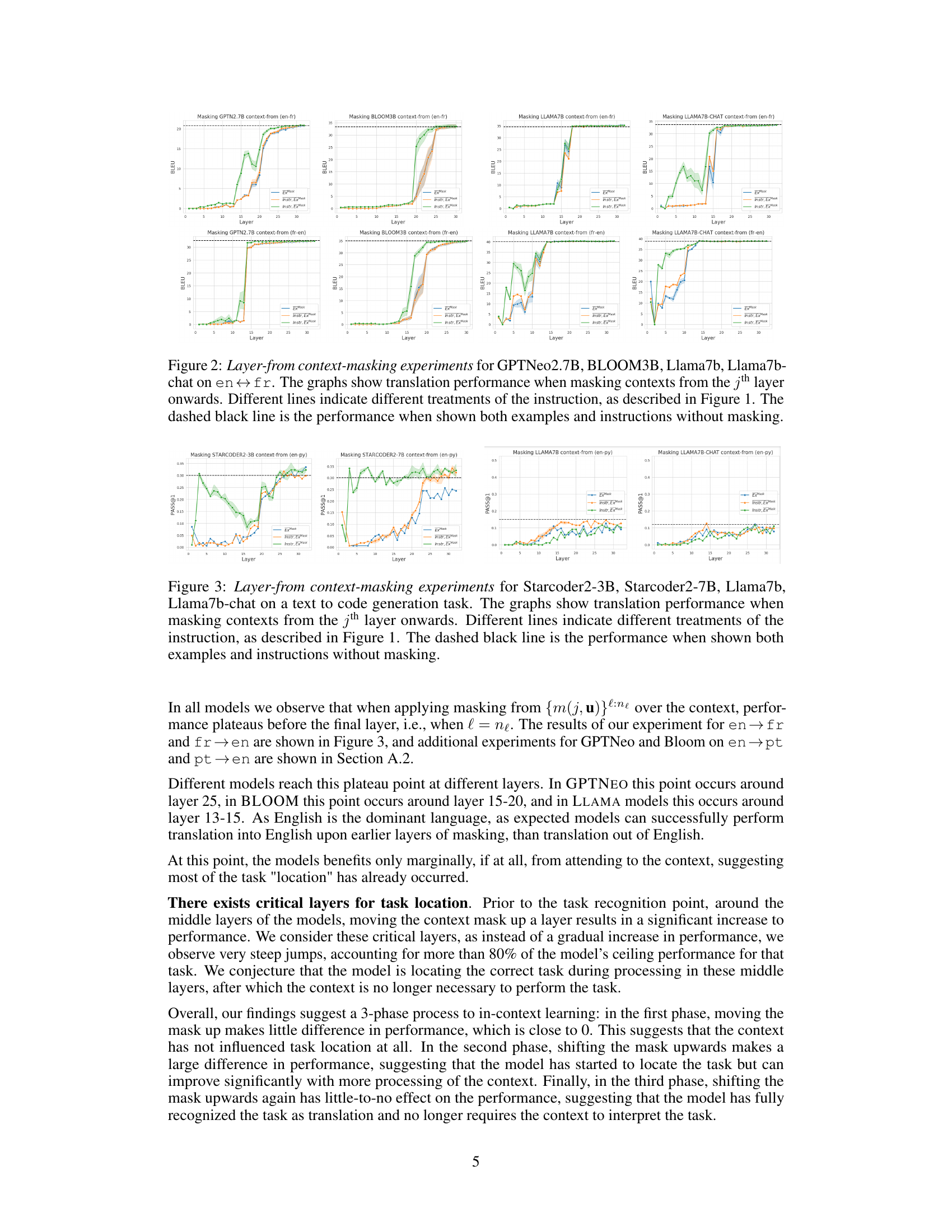

This figure presents the results of layer-wise context masking experiments conducted on four different large language models (GPTNeo2.7B, BLOOM3B, Llama7b, and Llama7b-chat) for machine translation between English and French. The experiments mask out attention weights to the context (instructions or examples) from a specific layer onwards. Each graph shows the translation performance (BLEU score) as the masking layer changes. Different colored lines represent different conditions of including instructions and/or examples. The dashed black line serves as a baseline representing the performance without any masking.

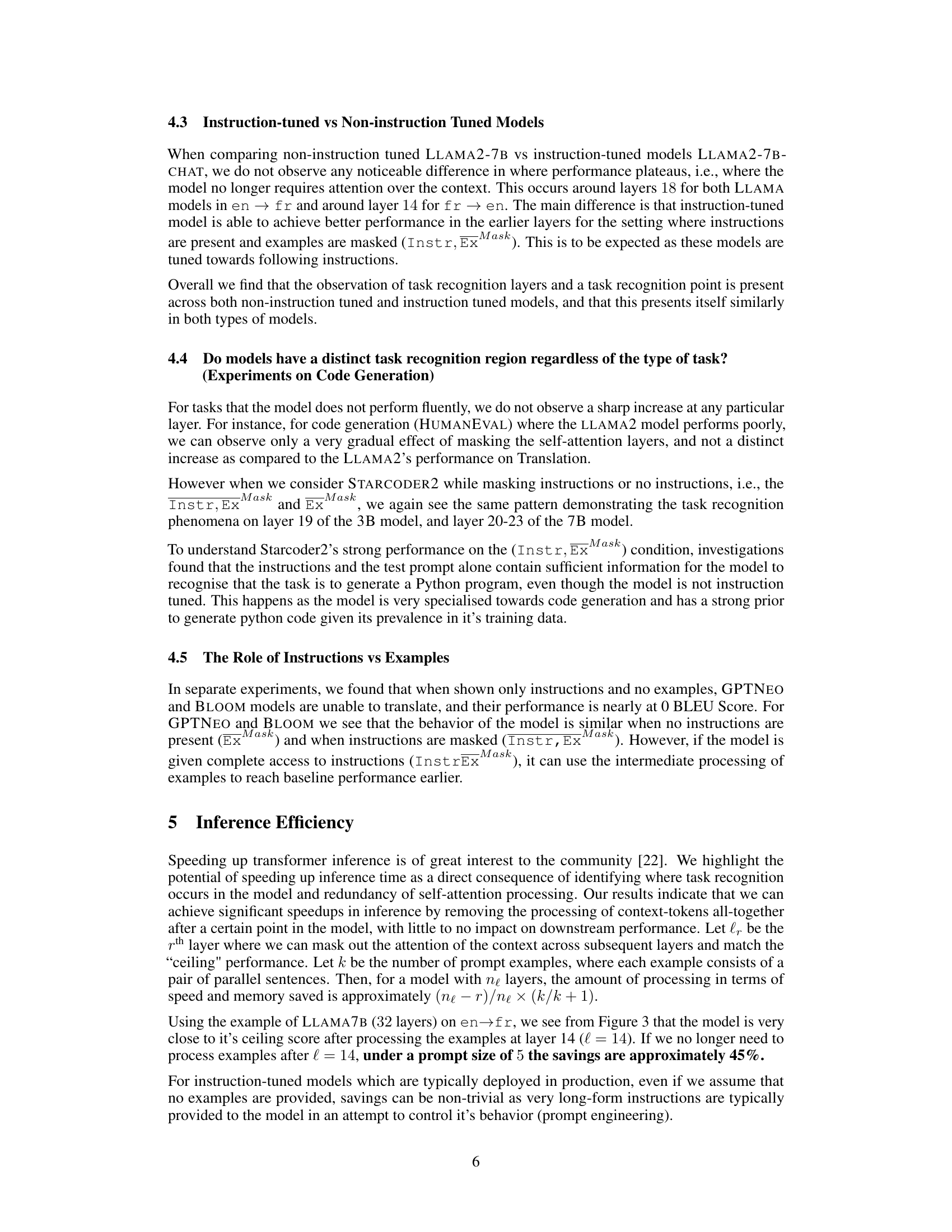

This figure displays the results of layer-wise context masking experiments conducted on four different large language models (LLMs) for a code generation task. The experiment masks out the attention weights to the context (instructions or examples) from a specific layer onwards to determine where in the model’s layers the ’task recognition’ occurs. The graphs present the performance (PASS@1) for each LLM when different parts of the context are masked, showing how the performance changes as more layers are masked. The different colored lines represent different combinations of instructions and examples in the context. A black dashed line indicates the performance without masking.

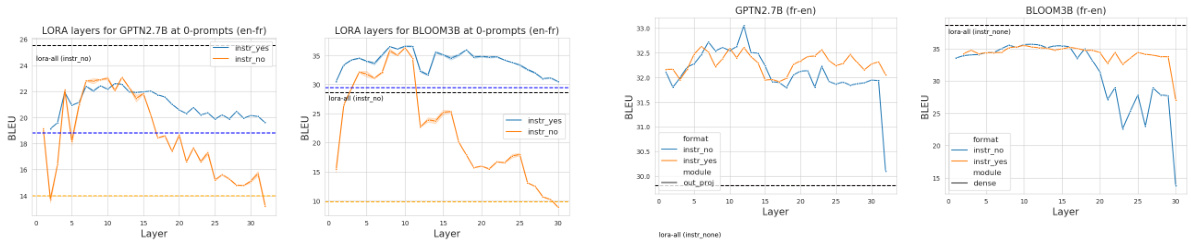

This figure shows the results of layer-wise context masking experiments on four different language models (GPTNeo2.7B, BLOOM3B, Llama 7B, Llama 7B-chat) for English-to-French translation. The x-axis represents the layer from which context masking begins (masking later layers). The y-axis represents BLEU score, a measure of translation quality. Different colored lines show the effect of masking with different combinations of instructions and examples (as defined in Figure 1 of the paper). The black dashed line shows the baseline performance with no masking.

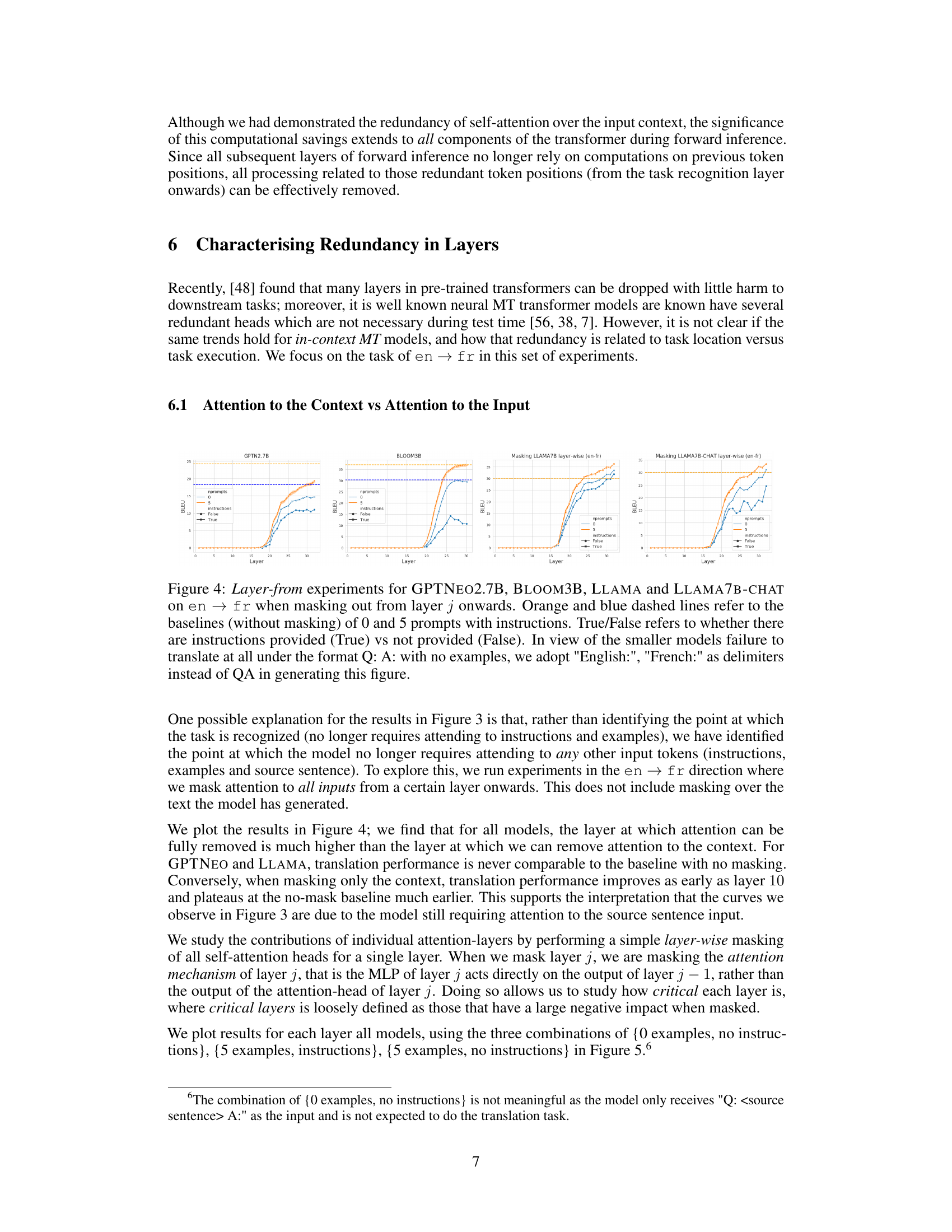

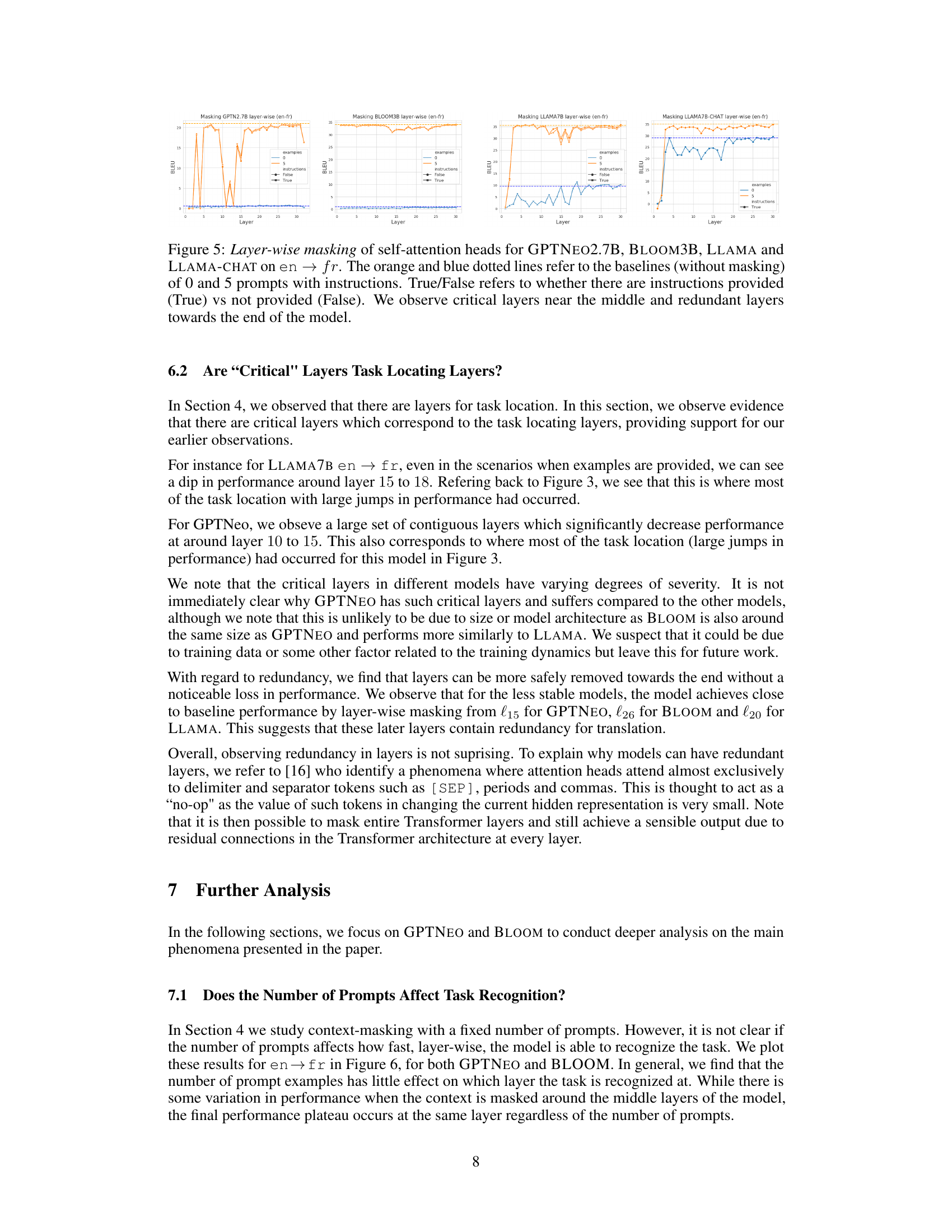

This figure displays the results of experiments where self-attention heads were masked layer by layer in four different language models (GPTNeo2.7B, BLOOM3B, LLAMA7B, and LLAMA7B-CHAT) during English-to-French translation. The models were tested with and without instructions and with 0 or 5 examples. The graph shows the BLEU score (translation quality) as the number of masked layers increases. The orange and blue lines represent experiments with and without instructions, respectively. The key observation is the identification of ‘critical layers’ (near the middle) where masking leads to a substantial drop in performance and ‘redundant layers’ (towards the end) where masking has little impact on performance. This supports the paper’s claim that the task recognition happens in specific model layers.

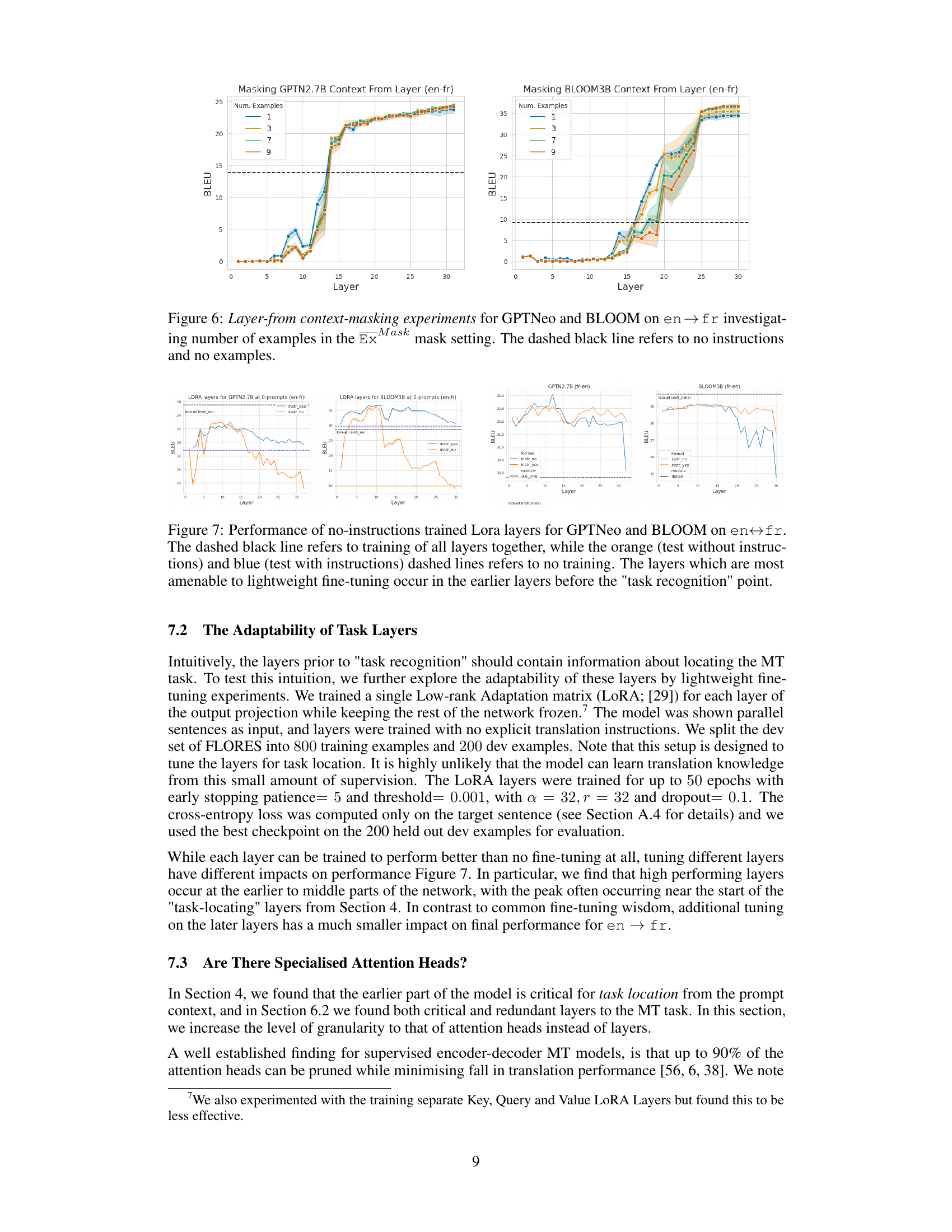

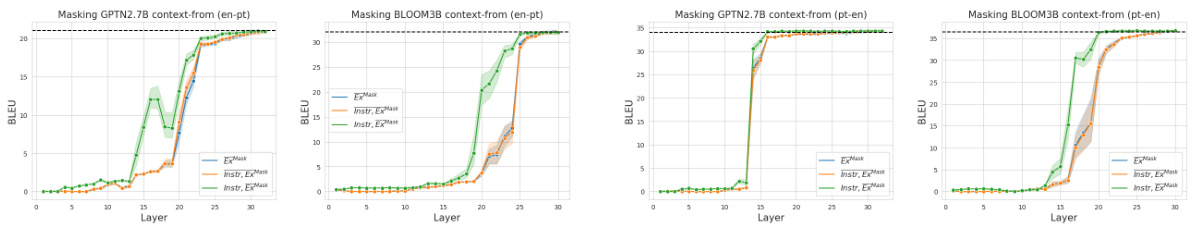

The figure shows the results of layer-from context-masking experiments performed on GPTNeo and BLOOM models for English-to-French translation. The experiments varied the number of examples provided in the context (1, 3, 7, and 9). The y-axis represents the BLEU score (a metric for evaluating machine translation quality), and the x-axis represents the layer number in the model from which context masking was applied. The dashed black line indicates the baseline performance with no context masking and no instructions. The shaded regions represent the standard deviations across multiple runs. The graph illustrates how model performance changes depending on the layer at which context masking starts and the number of examples provided, providing insights into where the model begins to rely less on the examples for successful translation.

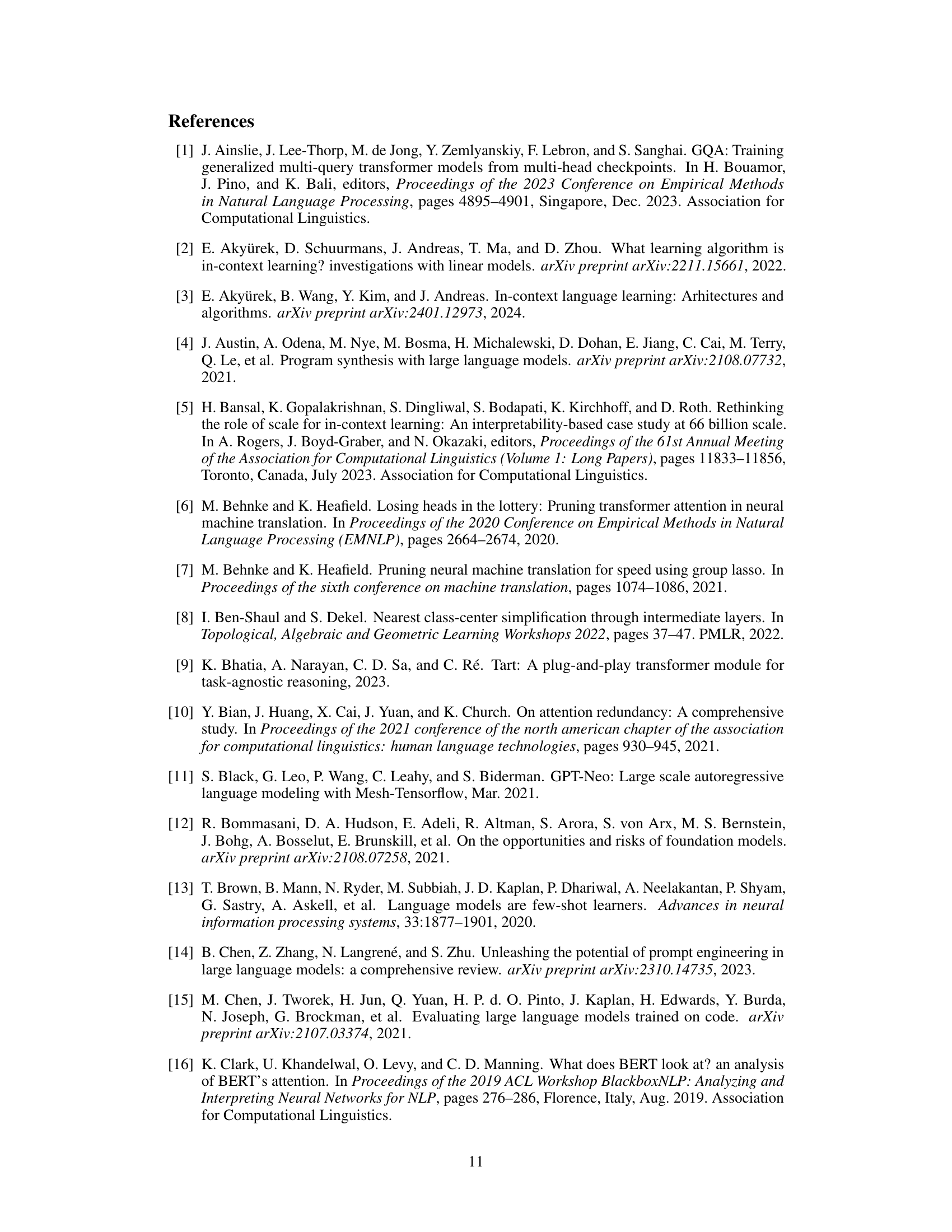

This figure shows the performance of lightweight fine-tuning (using LoRA) on different layers of GPTNeo and BLOOM models for the English-French translation task. The dashed black line represents the performance when all layers are trained together. The orange and blue lines show performance with and without training instructions, respectively, when only some layers are fine-tuned using LoRA. The results indicate that the earlier layers (before the task recognition point) are more amenable to lightweight fine-tuning.

This figure shows the results of context-masking and layer-masking experiments performed on the English to Portuguese translation task. The graphs illustrate how the translation performance changes when masking the attention weights to the context (instructions and examples) from a certain layer onward. The results in this figure mirror those found in Figures 3 and 5, suggesting that the observed trends generalize across different language pairs. This reinforces the paper’s findings about where task recognition occurs within the language model.

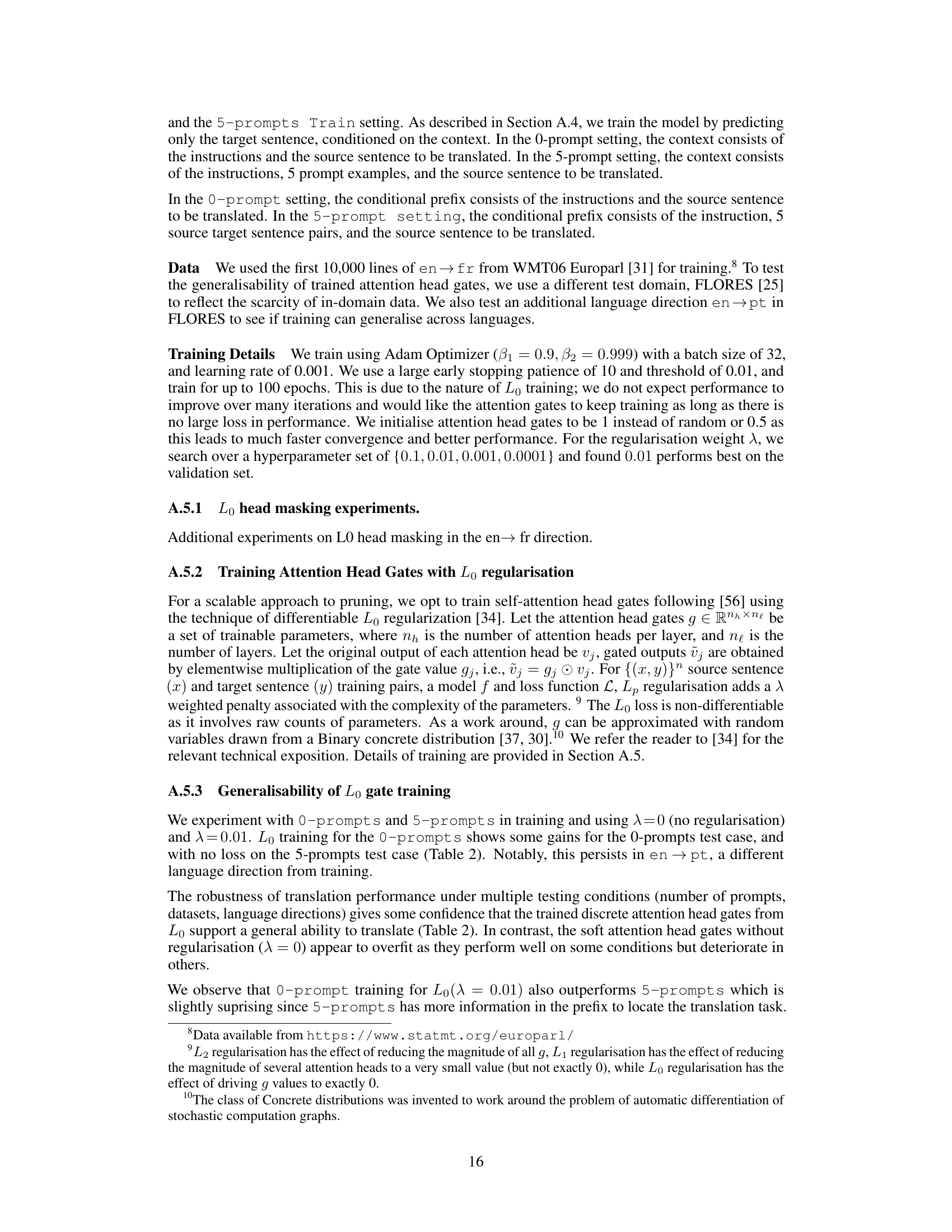

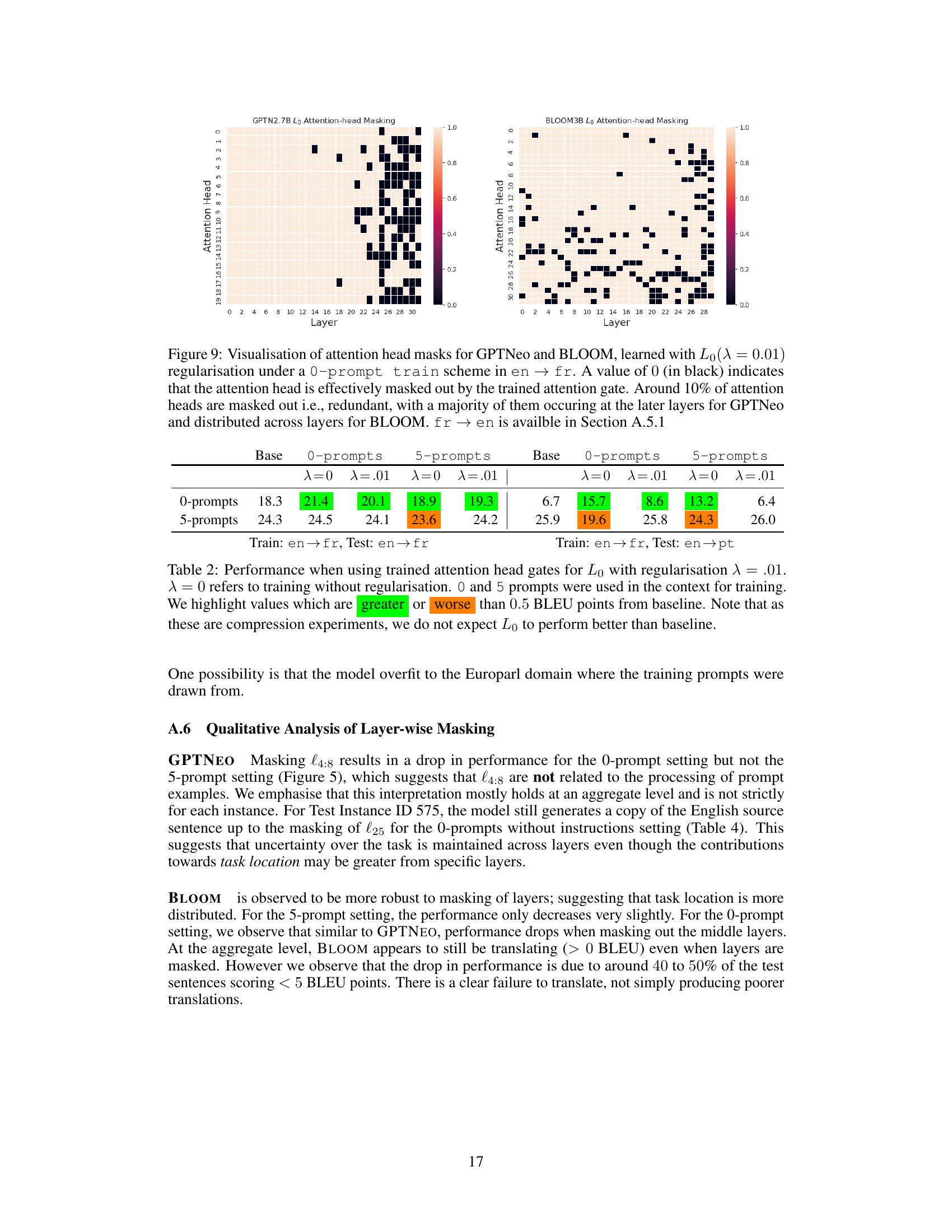

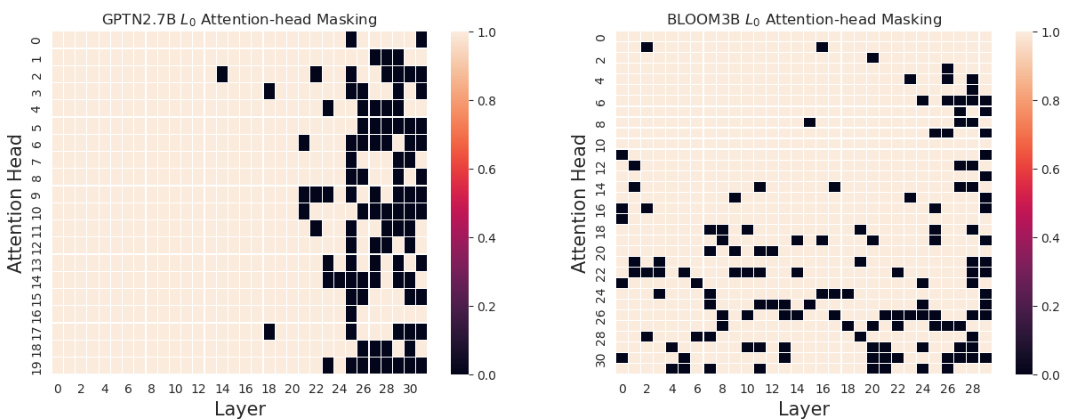

This figure visualizes the attention head masks learned for GPTNeo and BLOOM using L0 regularization with a 0-prompt training scheme for English-to-French translation. Black squares represent masked-out (redundant) attention heads. Approximately 10% of attention heads were masked, showing redundancy primarily in later layers for GPTNeo, and more evenly distributed across layers for BLOOM. Results for French-to-English translation are available in Appendix section A.5.1.

More on tables

This table presents the BLEU scores achieved using different training methods on the English-to-French and English-to-Portuguese translation tasks. The training methods involve using 0 or 5 prompts, with or without L0 regularization (λ=0 or λ=0.01). The table highlights the performance differences (greater than or less than 0.5 BLEU points) compared to the baseline.

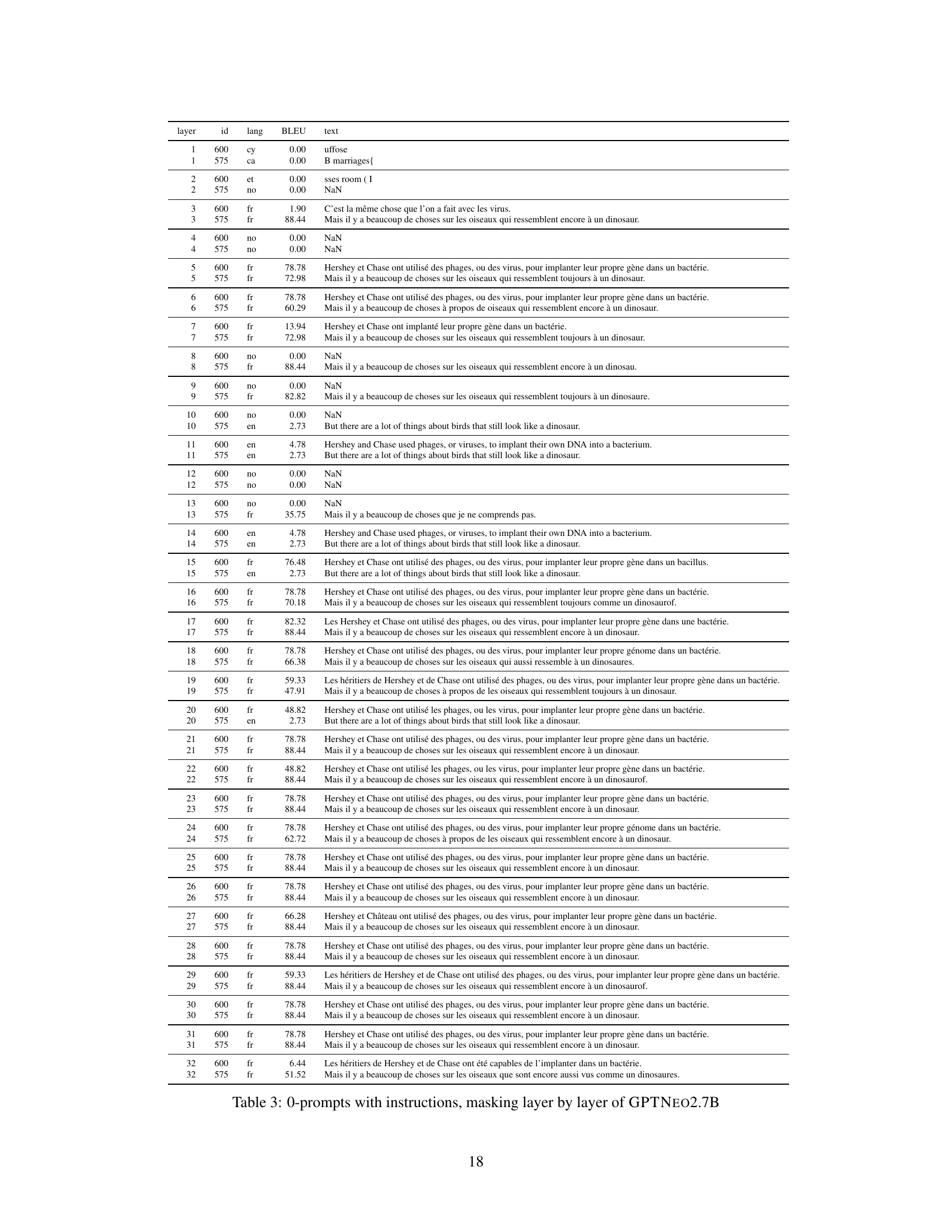

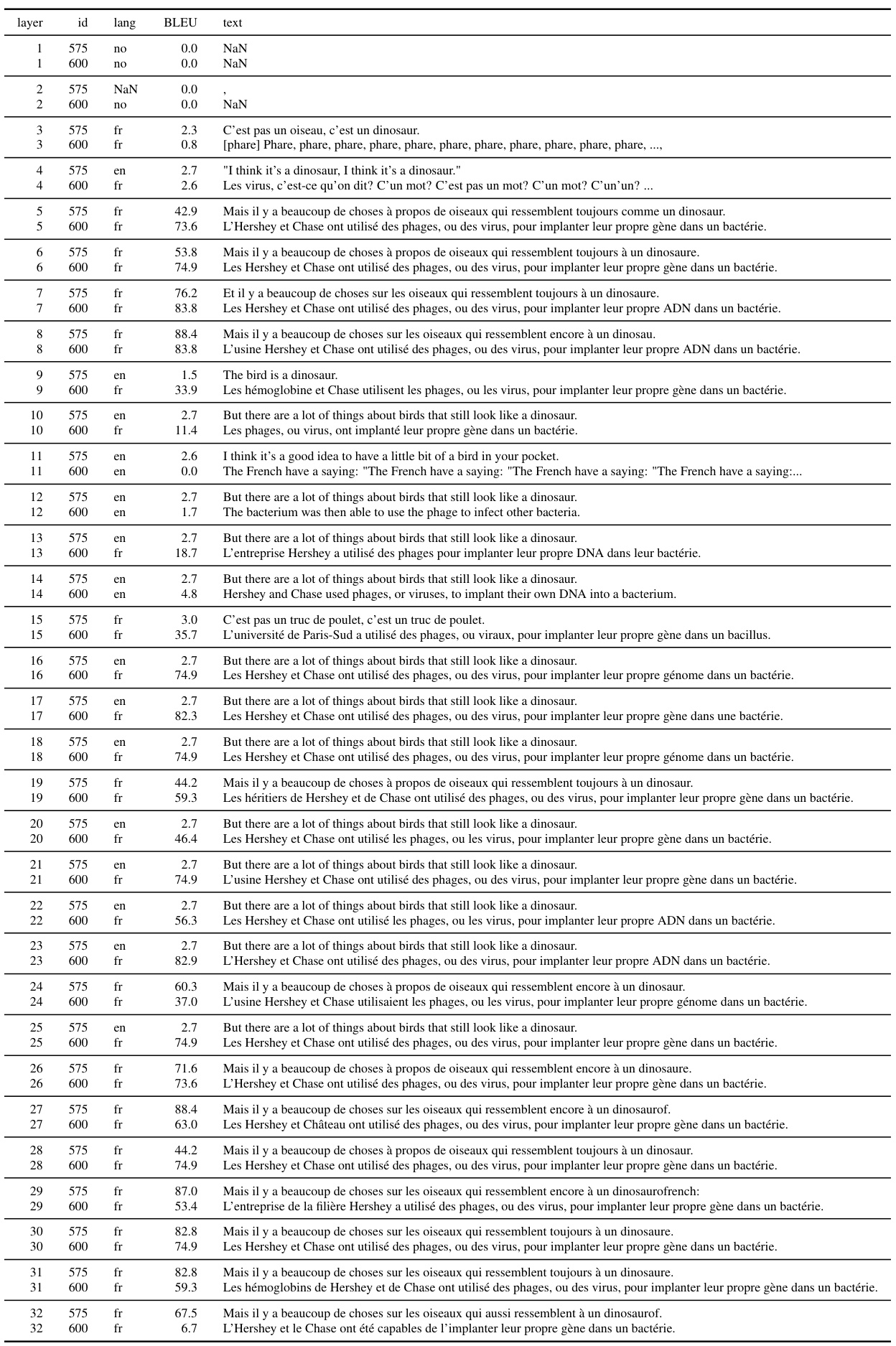

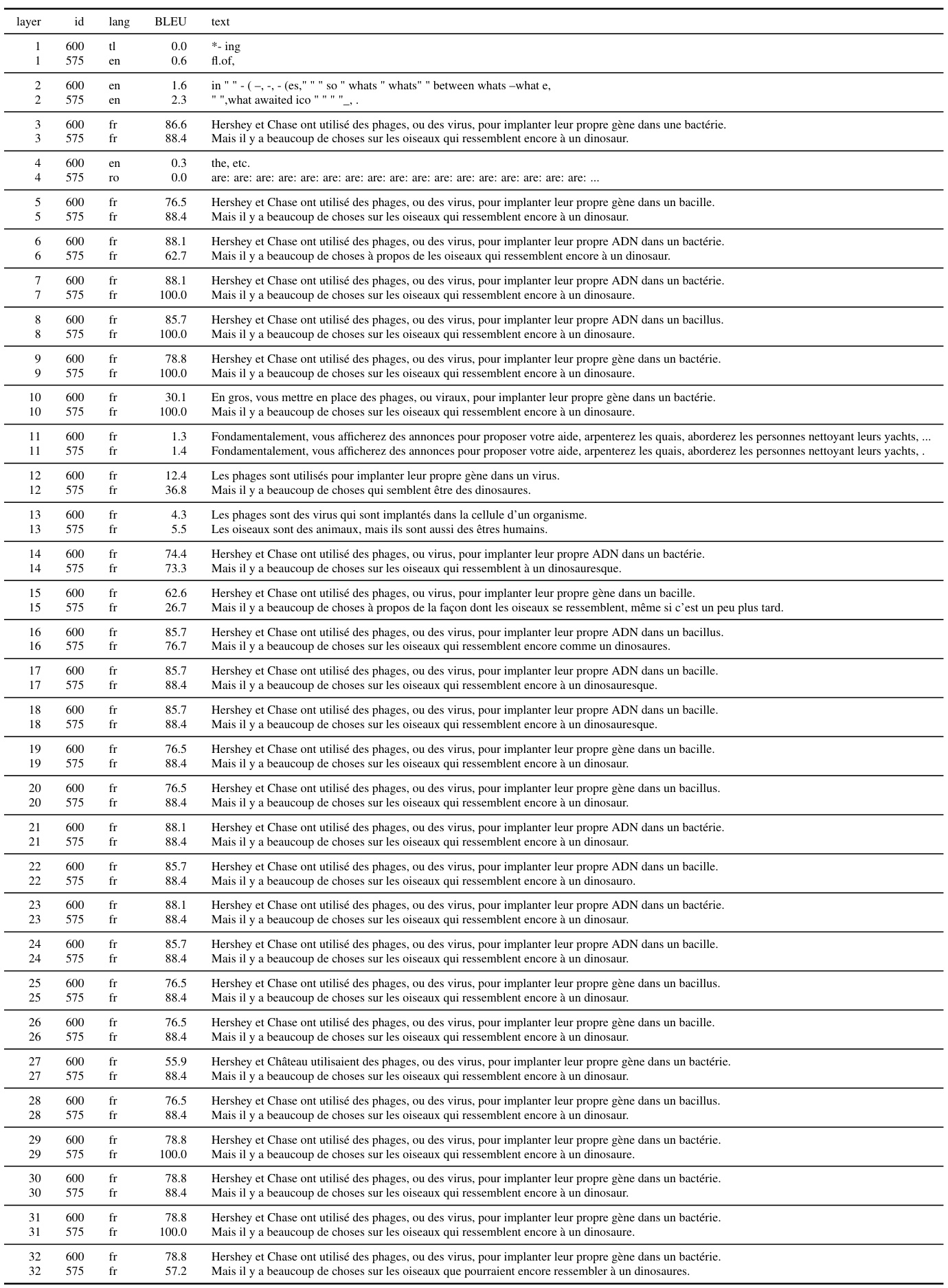

This table presents the results of an experiment where the GPT-NEO 2.7B model was tested with 0 prompts (no examples) and instructions, while masking out different layers of the model. The table shows the layer ID, language of translation, BLEU score, and the generated text for each layer. This helps illustrate the performance change at each layer when the context (examples and instructions) is incrementally removed from the attention process in the model.

This table presents the results of an experiment using the GPTNEO2.7B model. The experiment involved masking different layers of the model while performing machine translation from English to French. The prompt consisted of instructions but no examples. The table shows the layer ID, language, BLEU score, and the model’s generated text for each layer, allowing analysis of how masking different layers impacted translation performance. The presence of ‘NaN’ in the text column indicates that the model did not generate any coherent French translation.

This table presents the results of an experiment where the GPTNEO 2.7B model was tested with 0 prompts and instructions, with layer-wise masking applied. Each row represents a specific layer, and the columns show the layer ID, language of the generated text, BLEU score, and the generated text itself. The experiment aims to understand how the model’s performance changes as different layers of the model are masked.

This table presents the results of an experiment where the GPTNEO 2.7B model was tested with zero prompts and instructions, with layer-wise masking applied. The table shows the layer ID, language, BLEU score, and the generated text for each layer. This allows for an analysis of how the model’s performance changes as different layers of the network are masked, providing insights into the role of individual layers in the translation process.

Full paper#