↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

State-space models are crucial for understanding temporal data but existing probabilistic methods struggle with scalability and flexibility in large, nonlinear systems. Current approaches often sacrifice accuracy or model expressiveness to achieve scalability, hindering accurate forecasts and generative modeling. This significantly limits their applications in fields dealing with complex, high-dimensional time-series data, like neuroscience.

This paper introduces XFADS, a novel framework that leverages low-rank structured variational autoencoders to address these issues. XFADS’s inference algorithm exploits inherent covariance structures, enabling approximate variational smoothing with linear time complexity in the state dimension. Empirical results demonstrate its superior predictive capabilities compared to existing deep state-space models across various datasets, highlighting its potential for advancing research in diverse areas dealing with complex temporal data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents XFADS, a novel framework for large-scale nonlinear Gaussian state-space modeling. It addresses limitations of existing methods by enabling the learning of generative models capable of capturing complex spatiotemporal data structures with improved predictive accuracy. This opens avenues for research in diverse fields dealing with complex time-series data, including neuroscience and signal processing.

Visual Insights#

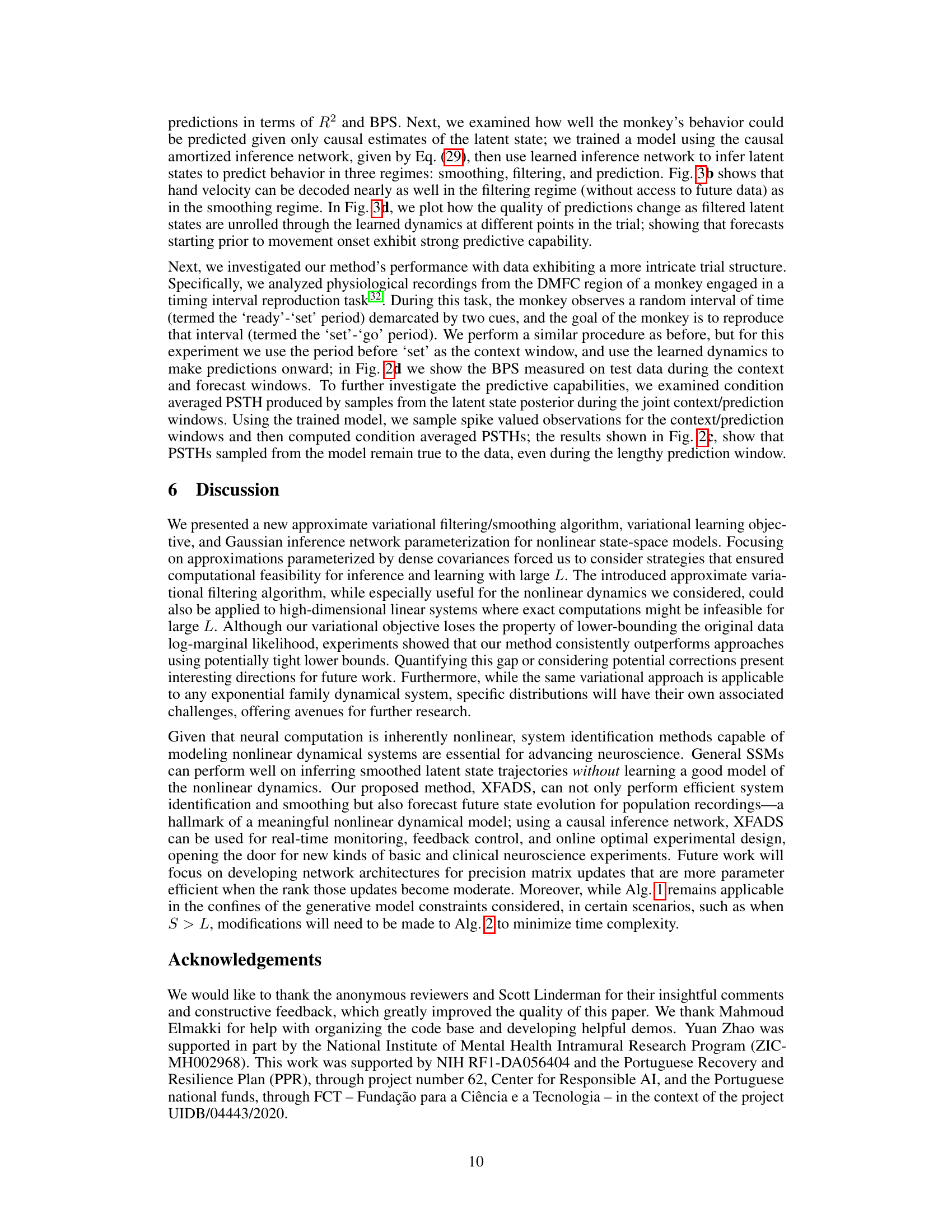

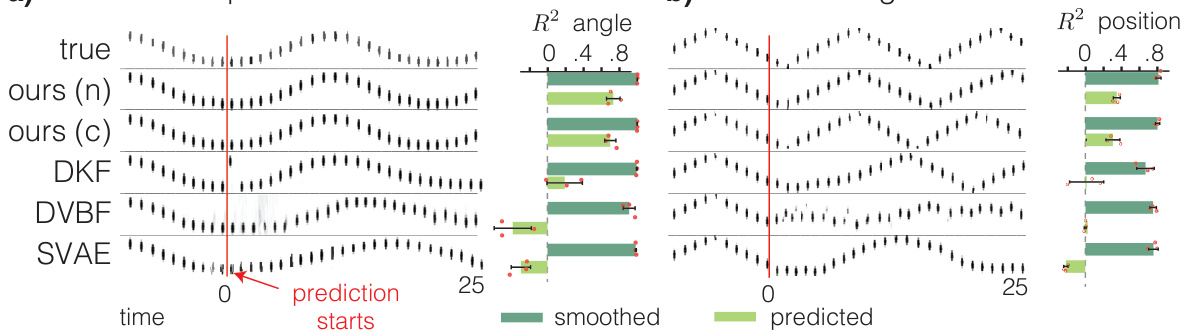

This figure compares the smoothing and predictive performance of the proposed method (XFADS) against several other state-of-the-art methods on two datasets: a pendulum and a bouncing ball. The left side of the red line in each subplot shows the smoothed posterior, which represents the model’s estimate of the system’s state during the observation window. The right side shows predictions made by unrolling the learned dynamics from the end of the observed data. The figure highlights that while several methods perform comparably at smoothing, XFADS significantly outperforms them in predictive accuracy, as measured by the R-squared (R2) value.

This table lists symbols used in the paper and their corresponding descriptions. It includes abbreviations for state-space models (SSM and LGSSM), notations for variational approximations and their parameters (π(zt), λt, μt, mt/Pt), update parameters (at, βt+1), and parameters of the dynamics and observation models (θ, pθ(zt|zt−1), pθ(z1), ψ, pψ(yt|zt)).

In-depth insights#

Nonlinear SSMs#

Nonlinear state-space models (SSMs) offer a powerful framework for modeling complex systems exhibiting non-linear dynamics. Their ability to capture intricate relationships between latent states and observations makes them particularly well-suited for applications where linear models fall short. A key challenge in working with nonlinear SSMs lies in inference, as exact inference is typically intractable. Therefore, approximate inference methods, such as variational inference, are commonly employed. These techniques introduce approximations to make inference computationally feasible, but the accuracy of these approximations needs careful consideration. The choice of approximating family, the structure imposed on the approximate posterior, and the optimization algorithm all play crucial roles in determining the effectiveness and scalability of the inference process. Moreover, the expressiveness of the dynamics model, often a neural network, directly impacts the model’s capacity to capture complex nonlinear behaviors. Balancing model expressiveness with computational tractability is a delicate art, requiring careful consideration of architectural choices and training strategies. The research of nonlinear SSMs is an active field of research, with ongoing efforts to develop more efficient and accurate inference algorithms and more expressive dynamics models.

Variational Filtering#

Variational filtering offers a principled approach to approximate inference in state-space models, particularly valuable when dealing with nonlinear dynamics where exact solutions are intractable. The core idea involves iteratively refining a belief distribution over the latent states, leveraging the model’s dynamics and observations. A key innovation lies in framing the approximate smoothing problem as an iterative filtering process, effectively circumventing the complexities of backward message passing. The algorithm relies on differentiable approximate message passing, enabling efficient gradient-based learning. The use of pseudo-observations (data-dependent Gaussian potentials) allows the incorporation of both prior information and current/future data to construct an informed posterior. This method’s efficacy hinges on its capacity to capture complex, dense covariance structures crucial for accurately representing the spatiotemporal dynamics of the latent states. Low-rank structure facilitates scalability, making this approach computationally feasible for large-scale problems. The method’s application to neural physiological recordings demonstrates its ability to model intricate spatiotemporal dependencies, achieving predictive performance superior to existing state-of-the-art deep state-space models.

Low-Rank Inference#

Low-rank inference methods offer a powerful approach to address the computational challenges of high-dimensional data analysis by approximating full-rank matrices with low-rank decompositions. This significantly reduces the number of parameters needed, leading to faster computation and decreased memory requirements. The core idea is that many high-dimensional datasets exhibit low-rank structure, implying that the data’s essential information lies within a lower-dimensional subspace. By leveraging this structure, low-rank techniques can efficiently capture the underlying relationships while reducing redundancy. This is particularly beneficial for real-time applications where computational efficiency is crucial, such as online filtering, and for large-scale problems where full-rank methods become intractable. However, reducing the rank introduces a trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. The choice of rank involves a careful balance, needing a sufficient number of parameters to represent the salient data features accurately while avoiding overfitting or losing important information. Moreover, effective low-rank algorithms require careful consideration of the specific problem structure to optimize approximation quality. Adaptive methods that adjust the rank dynamically can offer advantages by automatically adapting to the data’s complexity while retaining computational efficiency. Therefore, low-rank inference is a versatile technique with great potential for tackling high-dimensional problems; however, its success hinges on proper rank selection and efficient algorithms to handle the inherent approximation.

Predictive Dynamics#

Predictive dynamics, in the context of this research paper, likely refers to the model’s capacity to forecast future states of a system based on past observations. The core idea revolves around learning the underlying dynamical laws that govern the system from data, enabling the model to generate accurate predictions beyond the observed timeframe. This involves two crucial aspects: a generative model that captures the system’s evolution and an inference network capable of extracting meaningful representations from the observed data. The model’s predictive accuracy is a strong indicator of its ability to learn not just the static properties of the system but also its temporal dynamics. Successful predictive dynamics would likely showcase an understanding of complex relationships, allowing for robust extrapolations and a deeper grasp of causality within the system. The research likely evaluates this capacity through metrics like forecasting accuracy, compared against alternative state-of-the-art models, possibly highlighting the benefits of the proposed approach in handling high-dimensional and non-linear systems. Low-rank structured variational autoencoding, as mentioned in the abstract, suggests a focus on efficient computation, potentially allowing for better scaling with higher dimensionality, leading to more reliable and comprehensive predictive capabilities.

Future Extensions#

Future research could explore extending the model to handle missing data more robustly, perhaps by incorporating techniques like imputation or developing a more sophisticated inference network architecture that can inherently handle incomplete observations. Another promising direction is to investigate the model’s scalability to even larger-scale problems, especially in high-dimensional settings. This could involve exploring more efficient low-rank approximations of the covariance matrices or developing more efficient inference algorithms. Furthermore, research could focus on applying the model to a wider variety of datasets and domains to further validate its generalizability and uncover potential limitations. Finally, a key area for future work is to develop a deeper theoretical understanding of the model’s properties, including its convergence behavior and its ability to generalize to unseen data. This might involve analyzing the model’s capacity to capture complex nonlinear dynamics and investigating its relationship to other existing state-space models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

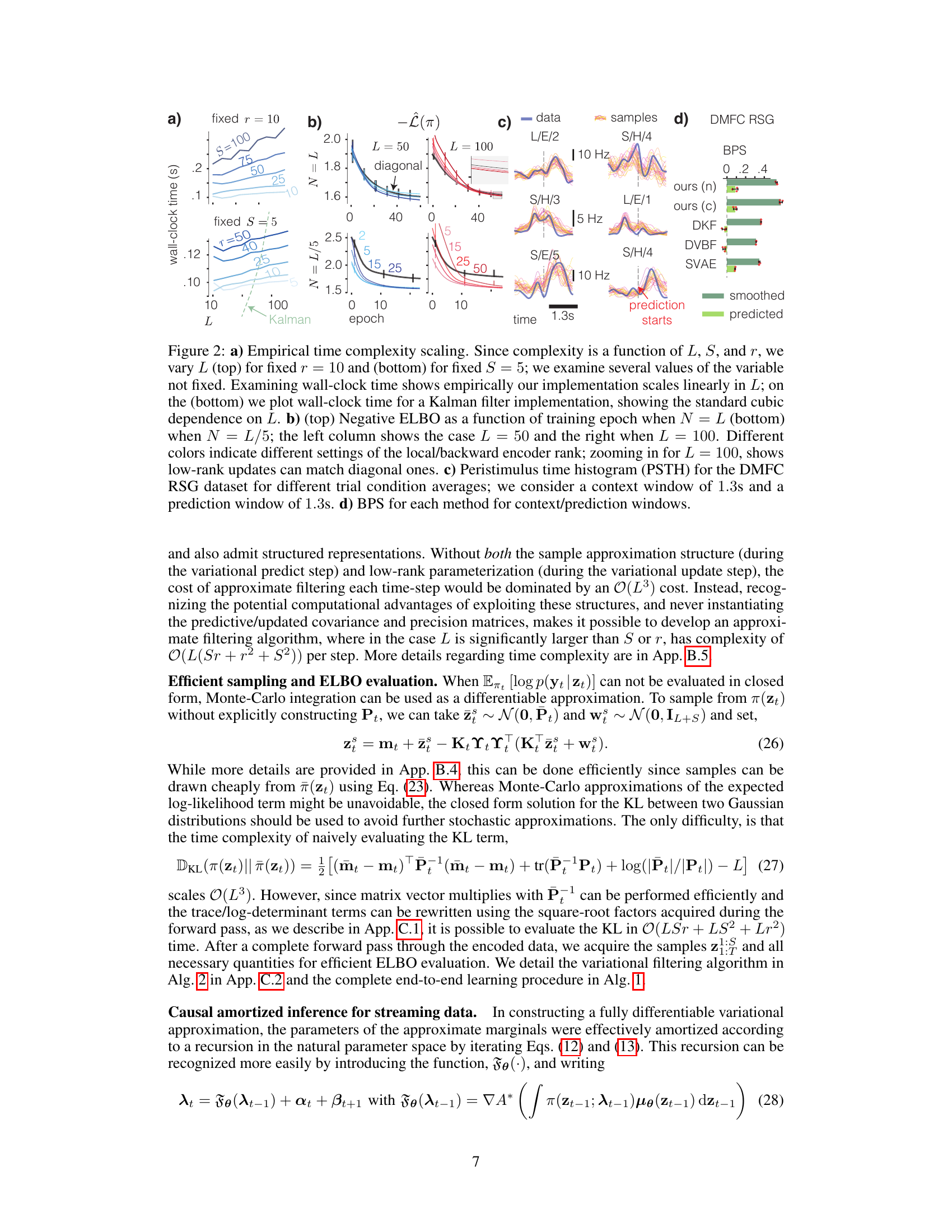

Figure 2 presents an empirical analysis of the proposed method’s time complexity and performance. Panel (a) demonstrates the linear scaling of the method’s time complexity with the latent state dimension (L), contrasting with the cubic scaling of a Kalman filter. Panel (b) shows the negative ELBO’s convergence over training epochs for different rank configurations of the local/backward encoder, illustrating that low-rank updates can achieve comparable performance to diagonal updates. Panel (c) displays peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) for different trial conditions of the DMFC RSG dataset, illustrating the ability of the method to capture and predict neural dynamics. Finally, panel (d) provides a comparison of bits-per-spike (BPS) values across different methods and conditions.

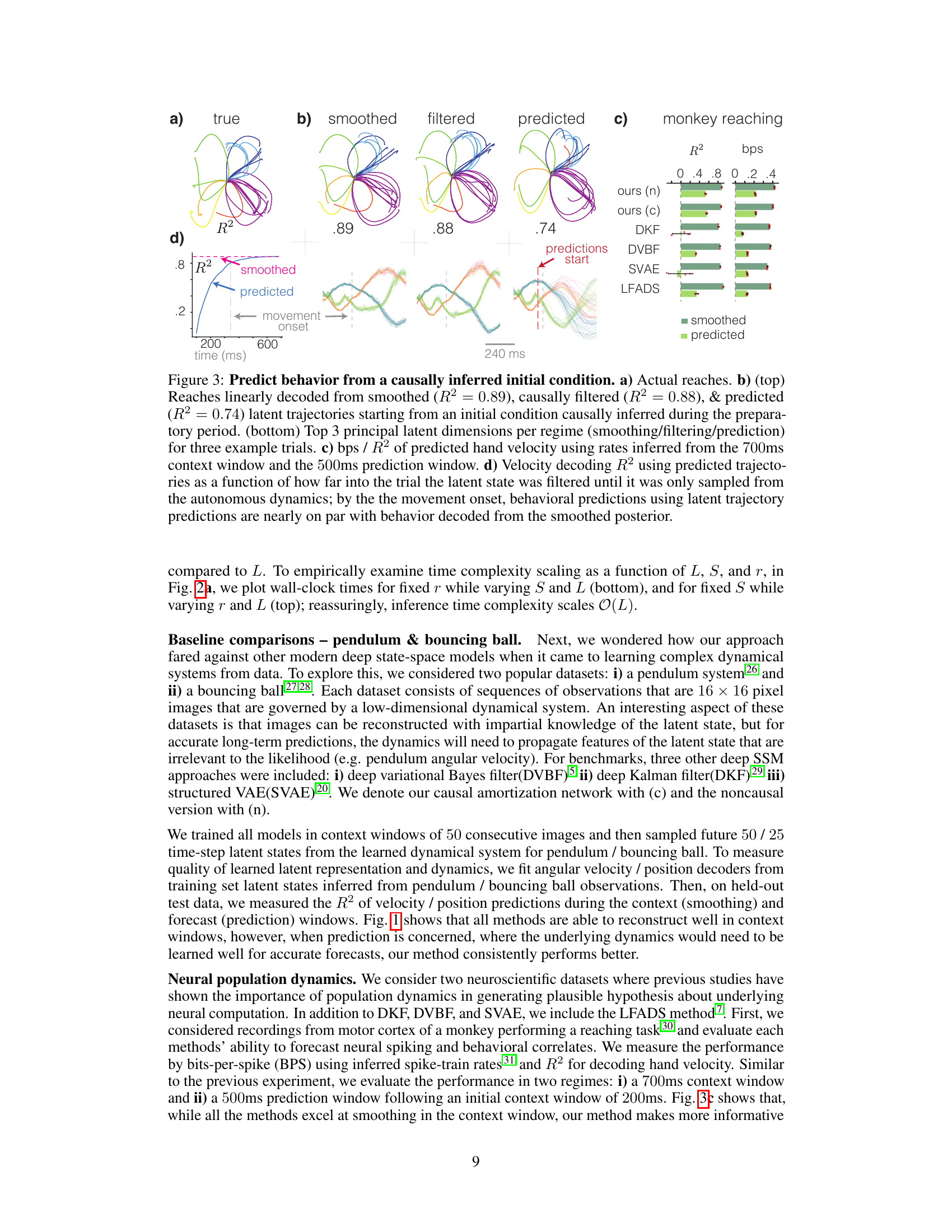

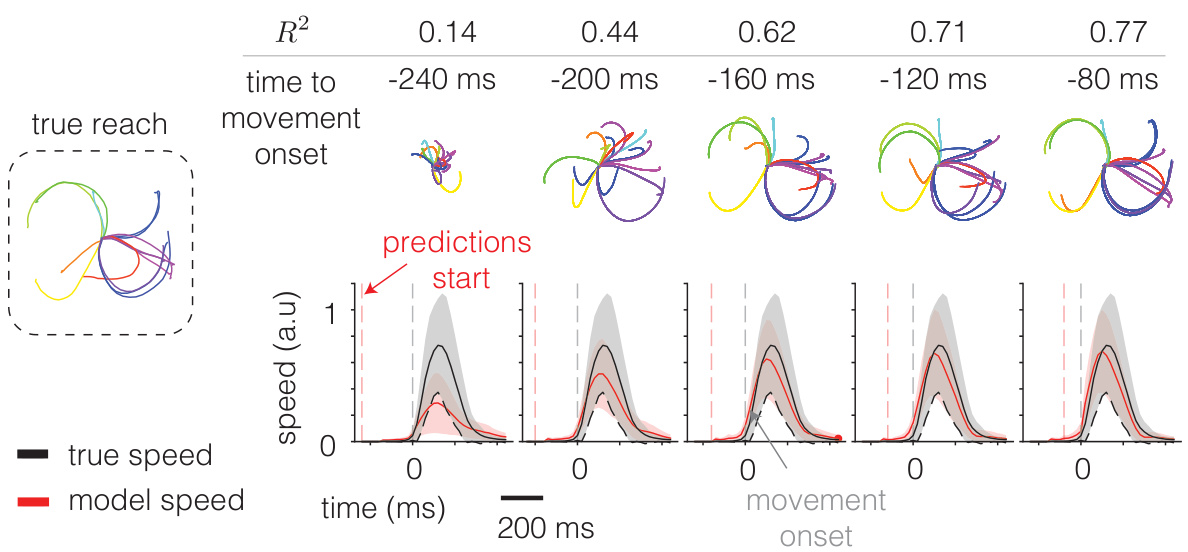

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to predict behavior from a causally inferred initial condition. Panel (a) shows actual monkey reaches. Panel (b) displays the reaches linearly decoded from the smoothed, causally filtered, and predicted latent trajectories. The top part shows the complete reaches, while the bottom part zooms into the top three principal latent dimensions to showcase the dynamics. Panel (c) provides a comparison of bits per spike (BPS) and R-squared (R2) values for predicted hand velocity using different context and prediction windows. Finally, panel (d) illustrates the predictive performance against the time into the trial, highlighting that predictions become comparable to the smoothed posterior at the movement onset.

This figure shows the predictive performance of the XFADS model on real monkey reaching data. The leftmost panel displays example reaches from the monkey. The remaining panels show the model’s ability to predict hand movement speed at different time points before the actual movement onset. The model uses increasing amounts of data (indicated by R² values and time to movement onset) to improve the prediction accuracy. The predicted hand movement speeds (red line) are compared to the true speeds (black line). The grey shading represents the variability/uncertainty in the model’s predictions.

Full paper#