↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications of contextual linear optimization (CLO) face the challenge of bandit feedback, where only the cost of the chosen decision is observed, not the costs of other potential choices. This limitation significantly hinders the application of existing CLO algorithms, which assume full cost observation for all potential decisions. This makes the accurate prediction of costs and optimization of policies challenging and creates a need for new methods and theories.

This research addresses this challenge by proposing induced empirical risk minimization (IERM), a novel offline learning framework for CLO with bandit feedback. The core contribution of the paper is a fast-rate regret bound for IERM, demonstrating that even with partially observed data and potentially misspecified models, the algorithms can still achieve near-optimal performance. Furthermore, computationally tractable surrogate losses are introduced to simplify the implementation of IERM, thereby making it more suitable for real-world deployment. The effectiveness of the IERM framework is numerically validated through a simulation study, demonstrating its practical utility in improving decision-making in settings with limited data availability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between contextual linear optimization (CLO) theory and practical application by addressing the realistic scenario of bandit feedback. It offers novel algorithms, theoretical guarantees, and practical insights, pushing the boundaries of CLO research and enabling more effective decision-making in various real-world settings with limited data.

Visual Insights#

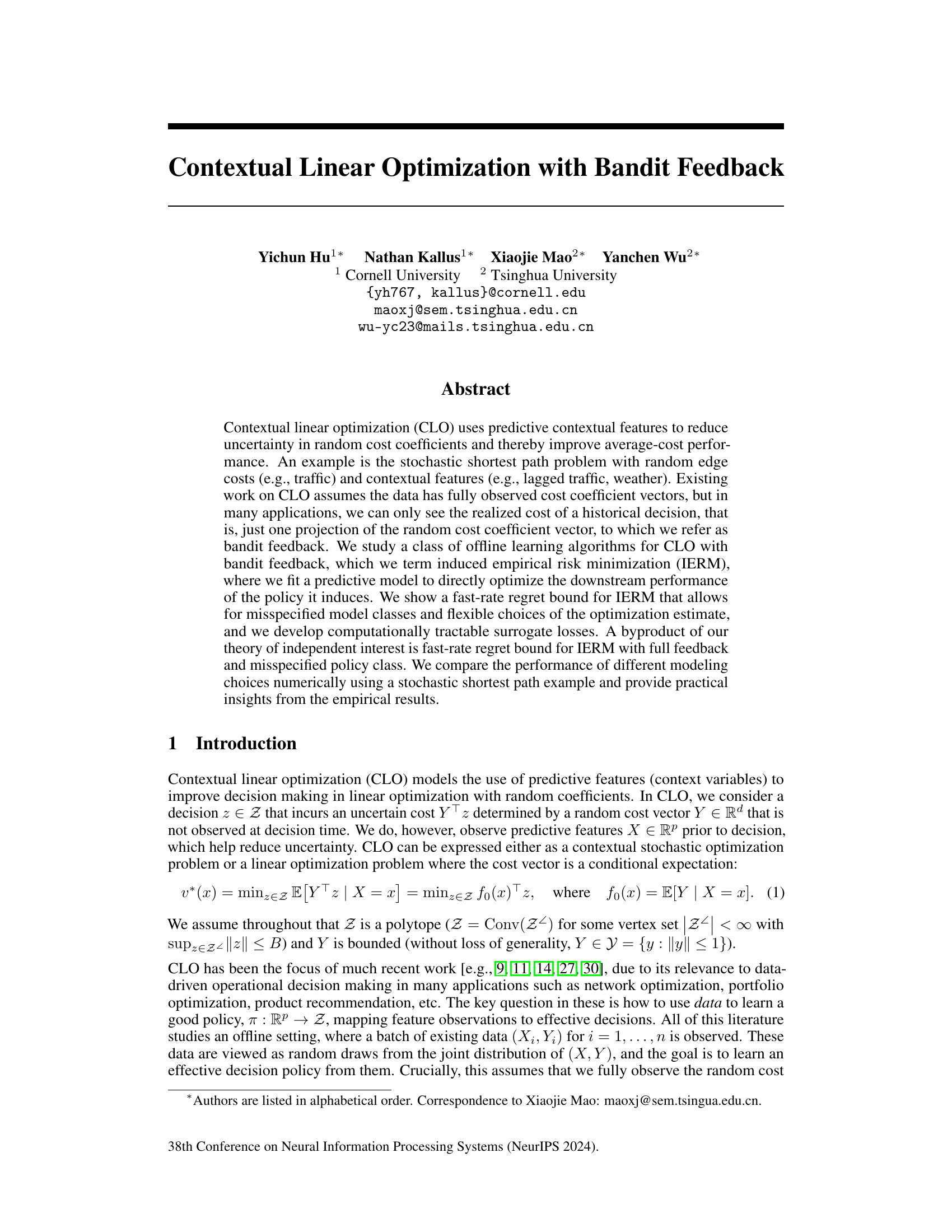

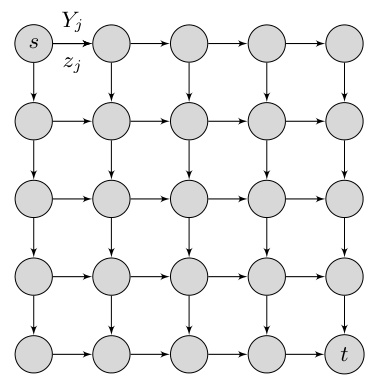

This figure shows a 5x5 grid representing a stochastic shortest path problem. Each circle node represents a location, with ’s’ as the starting point and ’t’ as the destination. Each edge connecting two nodes has an associated random cost Yj, where ‘j’ is the index for the edge. The decision variable zj is binary (0 or 1), representing whether or not to traverse the edge ‘j’. The goal is to find the shortest path from ’s’ to ’t’, considering the uncertain costs on each edge.

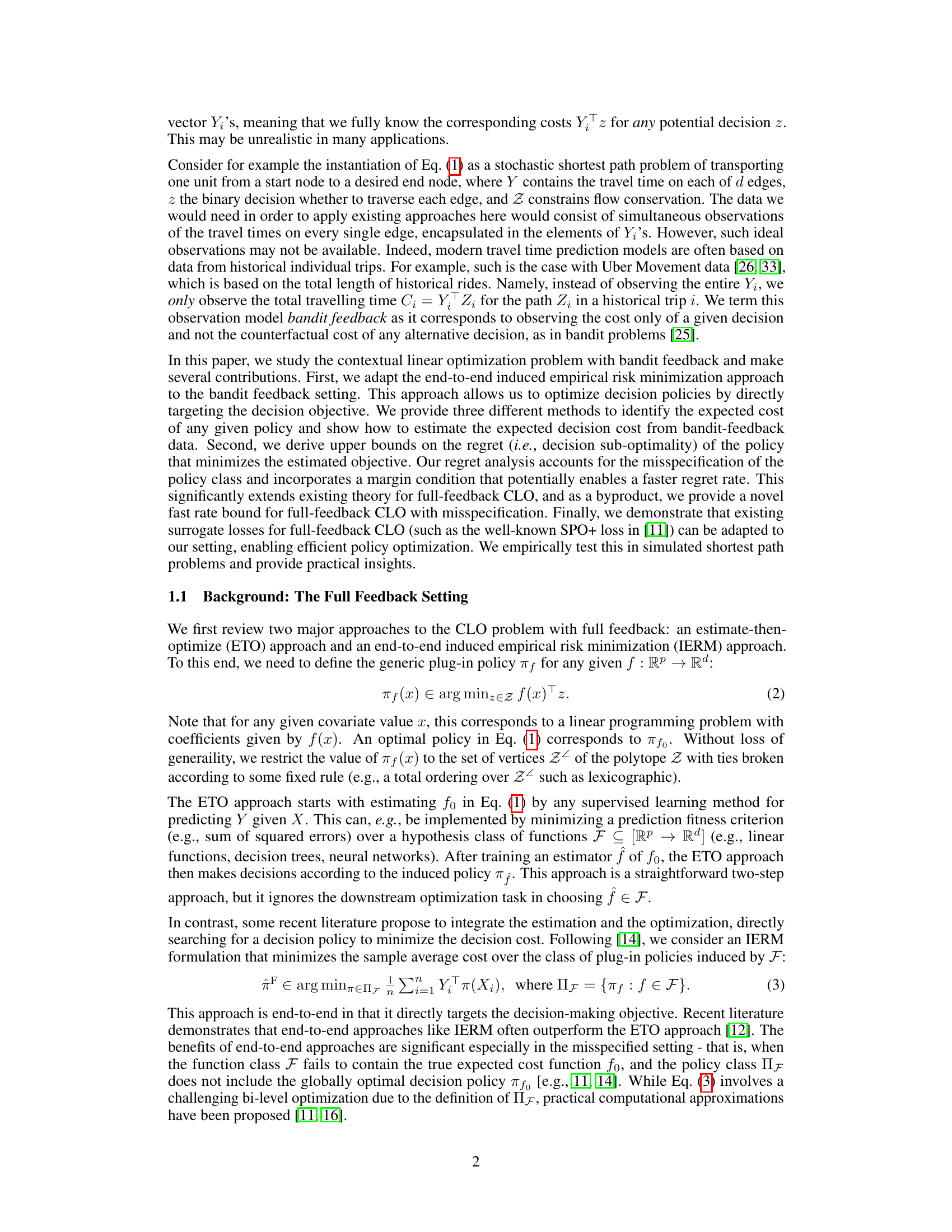

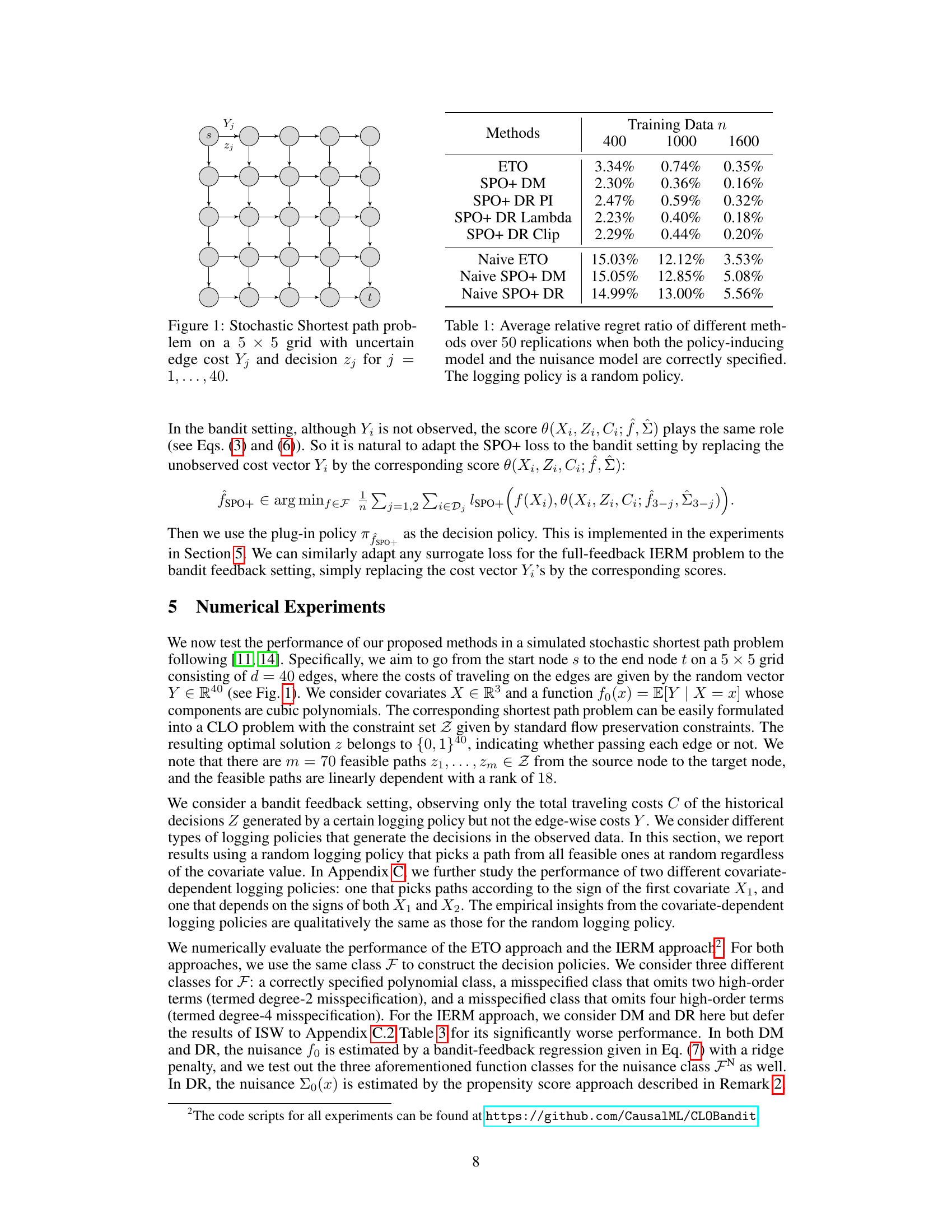

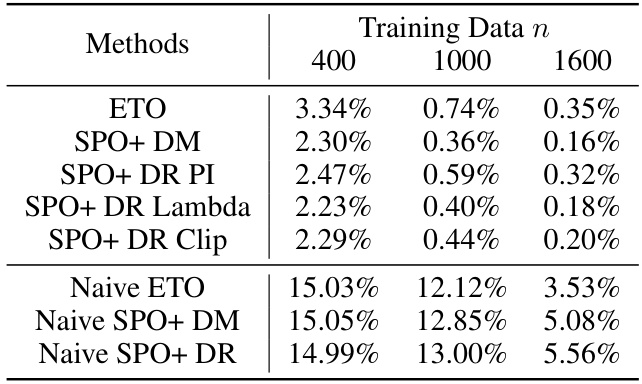

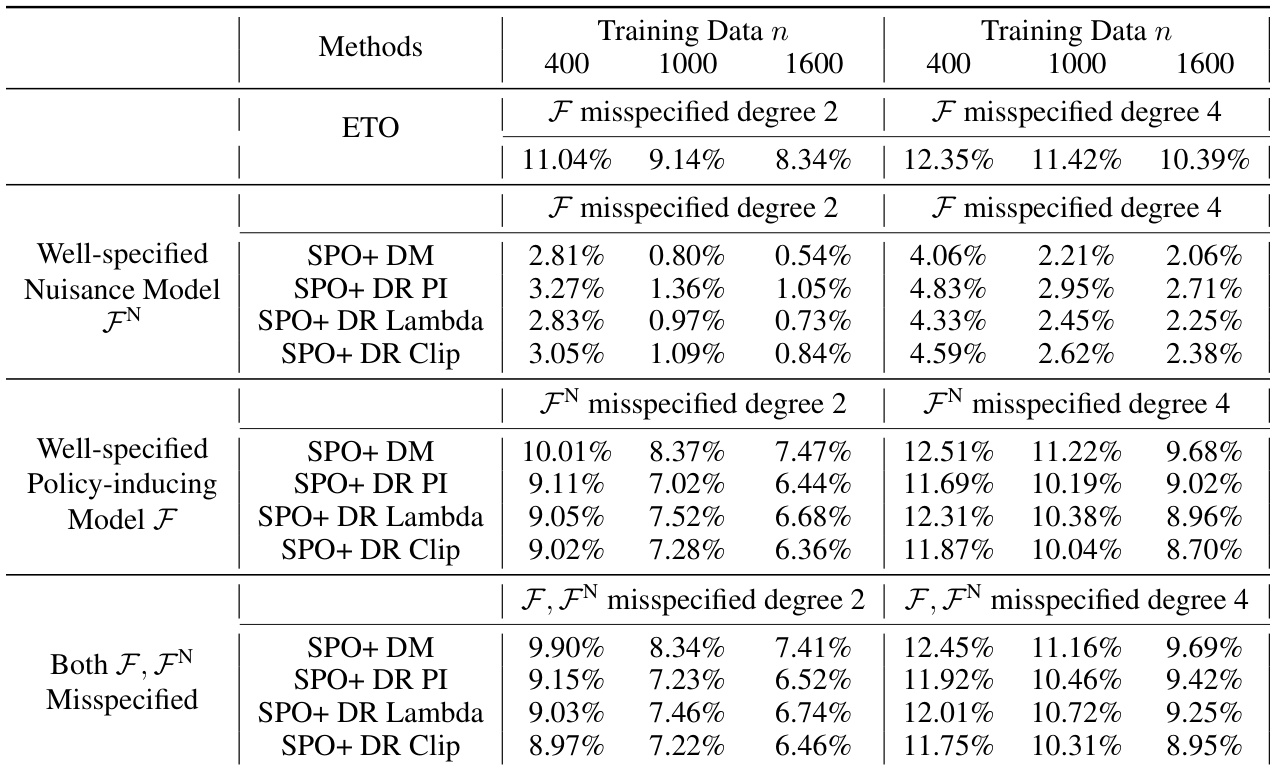

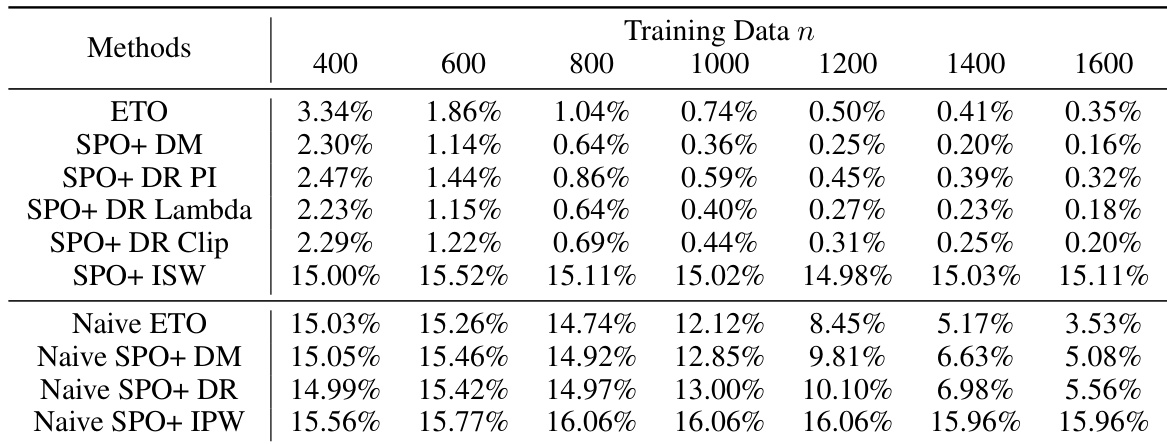

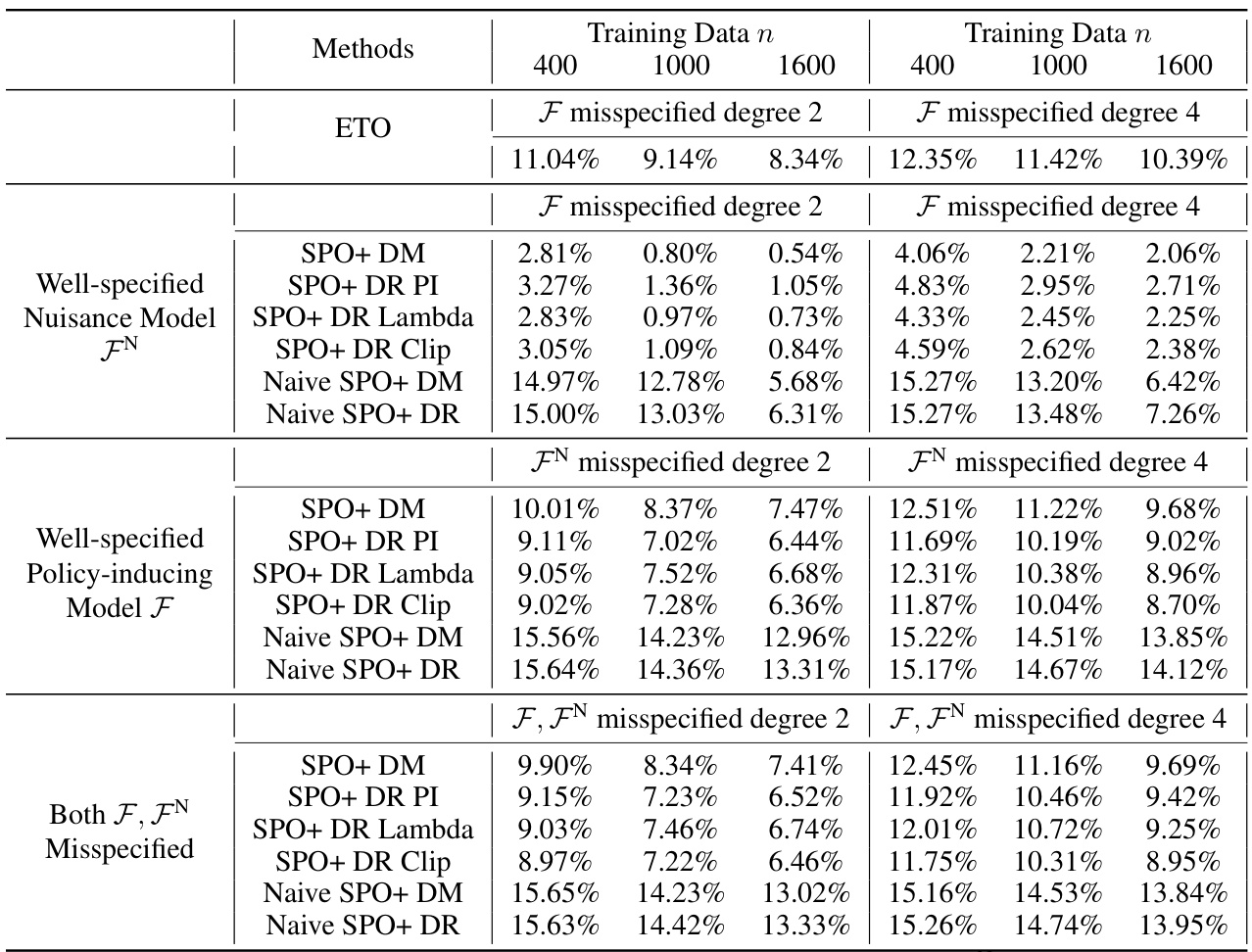

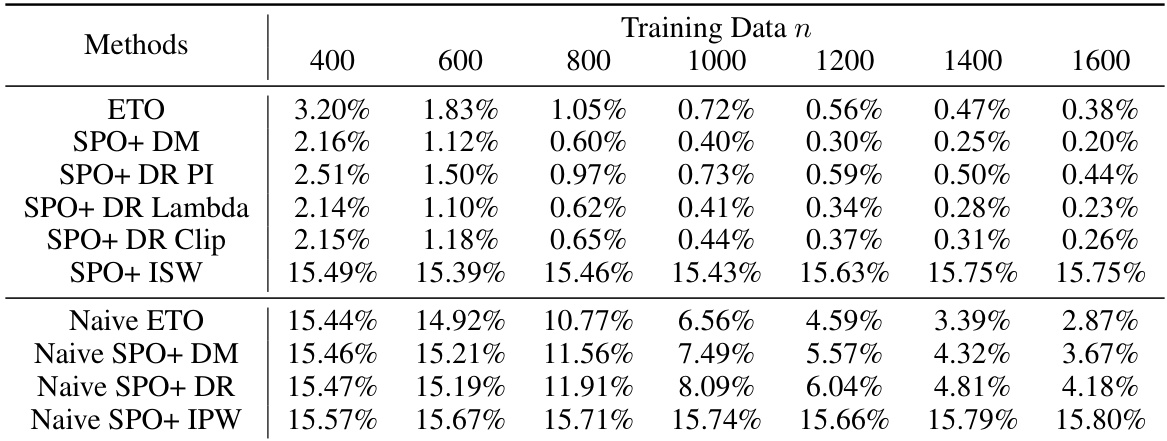

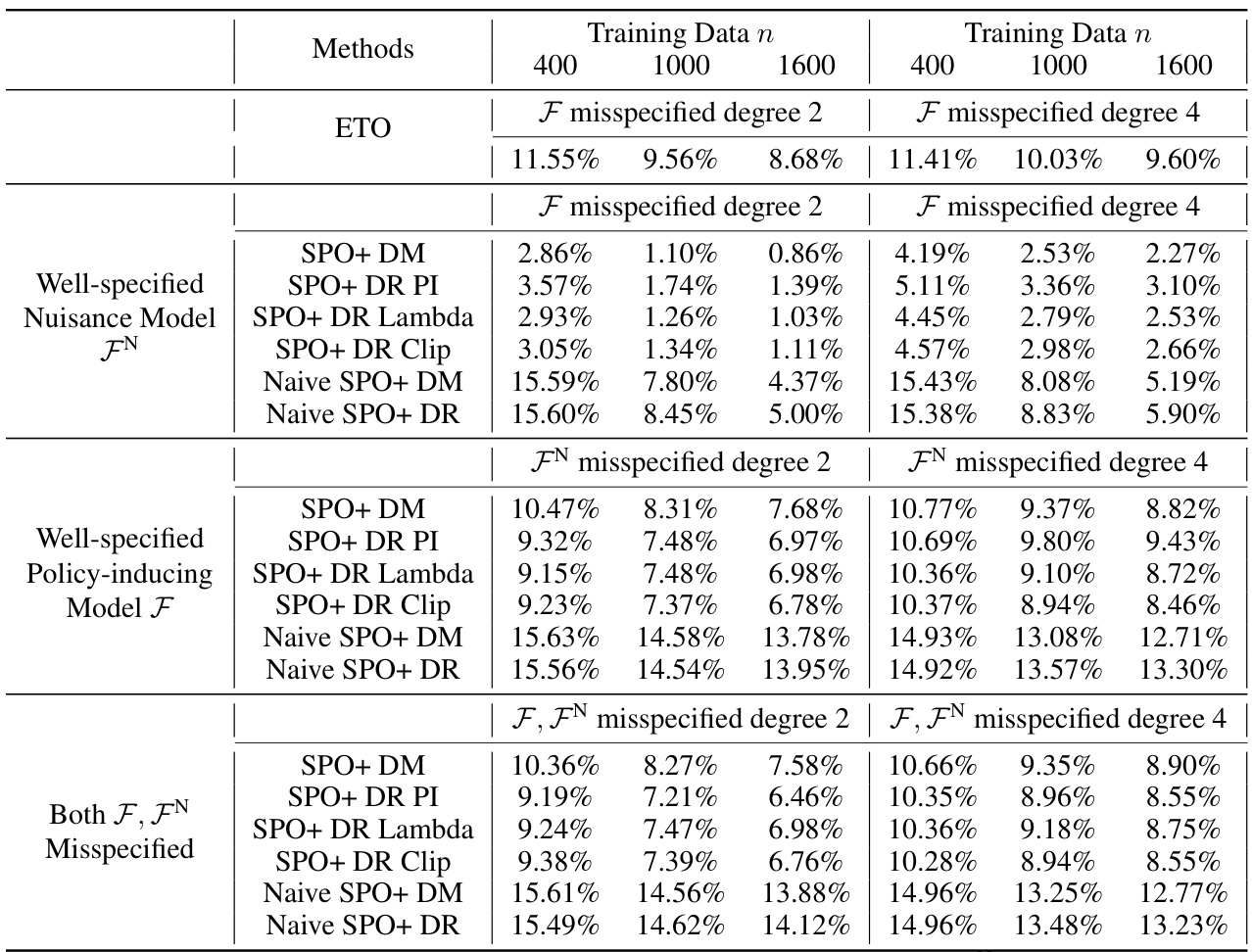

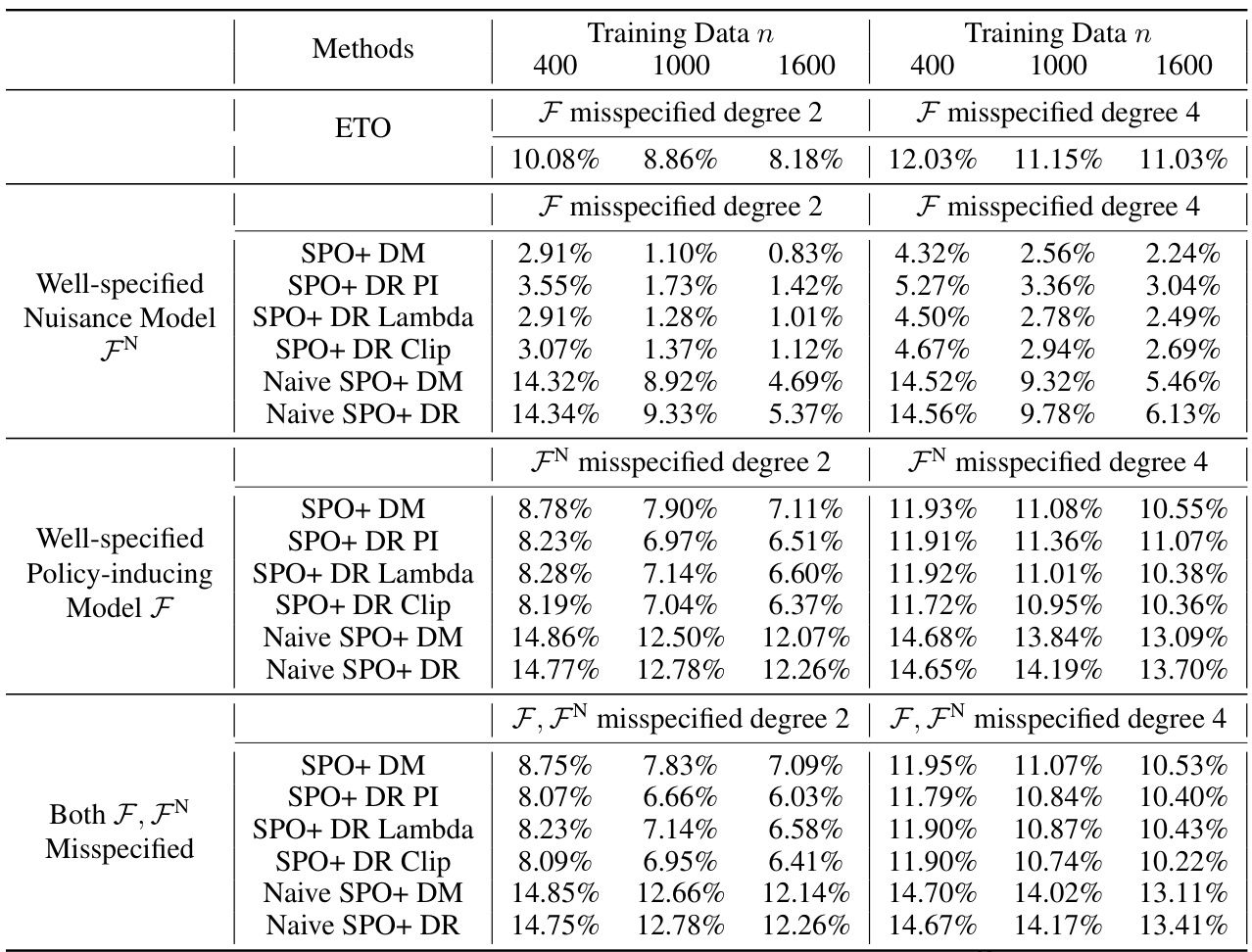

This table presents the average relative regret ratio for various methods across 50 replications of an experiment. The results are shown for different training dataset sizes (400, 1000, and 1600 data points) when the model used to induce the policy and the nuisance model are correctly specified and the logging policy is random. The relative regret is a measure of how suboptimal a given policy is in comparison to the best possible policy.

In-depth insights#

Contextual Bandit CLO#

Contextual Bandit CLO integrates contextual information and bandit feedback mechanisms within the framework of contextual linear optimization (CLO). The core idea is to leverage contextual features to improve the efficiency of decision-making in scenarios where the cost of actions is uncertain and only partially observable. This differs from standard CLO, which typically assumes full observability of cost vectors. Bandit feedback, where only the realized cost of the chosen action is observed, introduces significant challenges. The key contribution of this approach lies in the development of algorithms that effectively learn optimal policies despite the limited information. This requires addressing the trade-off between exploration (gathering more information) and exploitation (optimizing performance based on current knowledge). Algorithms would likely involve techniques such as inverse probability weighting, doubly robust estimation, or other methods designed to handle missing data and uncertainty. The combination of contextual information and bandit feedback allows for more adaptive and efficient decision-making, making this a valuable area of research with applications in various fields, such as online advertising, recommender systems and operations research.

IERM Regret Bounds#

Analyzing IERM regret bounds requires a nuanced understanding of the algorithm’s core mechanics. The regret, a measure of sub-optimality, is intrinsically linked to the complexity of the function class used in the induced empirical risk minimization (IERM) approach. A richer function class allows for a better approximation of the optimal policy, but introduces higher complexity, potentially leading to increased regret. The analysis often involves bounding the regret using Rademacher complexity, which quantifies the richness of the function class. Crucially, the analysis needs to address model misspecification, where the true optimal policy may not be contained within the function class. The regret bounds depend on the misspecification error, the complexity of the function class, and the quality of nuisance function estimates. Fast rates of convergence are often desired, and these depend on margin conditions which determine how easily the optimal policy is distinguished from suboptimal policies. The presence of bandit feedback, as opposed to full feedback, increases the analytical challenge, requiring more sophisticated techniques to handle partial observability of costs.

Bandit Feedback IERM#

Bandit feedback presents a unique challenge to contextual linear optimization (CLO) by limiting observability to only the realized cost of a chosen action, unlike full-feedback settings. Induced Empirical Risk Minimization (IERM), adapted to this bandit feedback scenario, becomes crucial. Instead of directly observing the full cost vector, IERM in this context learns a predictive model to estimate the expected cost of various actions given contextual features and then optimizes downstream performance based on these estimates. This indirect approach necessitates robust estimation techniques and careful consideration of model misspecification, which the authors address by proving a fast-rate regret bound, even under misspecified models and flexible optimization estimates. The development of tractable surrogate losses is also crucial for practical implementation. The effectiveness of IERM with bandit feedback is demonstrated through empirical results on a stochastic shortest path problem. This approach provides a powerful framework for tackling CLO problems where observing the full cost vector is infeasible.

Surrogate Loss#

The concept of a “Surrogate Loss” in the context of contextual linear optimization (CLO) with bandit feedback is crucial for efficient learning. Directly optimizing the IERM objective in CLO with bandit feedback is computationally intractable due to its non-convexity. Therefore, the authors explore surrogate loss functions, specifically highlighting the SPO+ loss as a computationally tractable alternative. SPO+ offers several advantages, including convexity with respect to the model parameters, enabling efficient optimization via techniques like gradient descent. The effectiveness of SPO+ is experimentally validated and it’s shown that its use directly addresses the computational challenges inherent in the IERM formulation. The paper’s contribution is not simply in proposing SPO+, but in demonstrating its practical applicability within the specific context of CLO and bandit feedback. Furthermore, the authors adapt SPO+ for use with different methods for estimating the expected cost (DM, ISW, DR), further highlighting its flexibility and robustness. The analysis of using these surrogate losses, in tandem with the theoretical regret bounds, suggests a pragmatic approach for tackling a previously difficult problem, paving the way for more efficient and scalable algorithms in contextual decision-making.

Empirical Analysis#

An empirical analysis section in a research paper would typically present the results of experiments or observational studies designed to test the paper’s hypotheses or claims. A strong empirical analysis would begin by clearly describing the data used, including its source, size, and relevant characteristics. Methodology would be detailed, specifying the experimental design, data collection methods, and any pre-processing steps. Results would be presented clearly and concisely, often using tables, figures, and statistical measures to summarize key findings. Statistical significance of any observed effects should be reported, along with measures of effect size. The analysis should directly address the research questions, and any limitations of the data or methods should be acknowledged. Finally, a thoughtful discussion interpreting the results in light of existing literature and the implications of the findings would be crucial for a robust empirical analysis. Visualizations are key, allowing readers to quickly grasp major trends and outliers.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table shows the average relative regret ratio for different methods across 50 replications of the experiment for a random logging policy. The results are shown for three different training data sizes (400, 1000, 1600). The methods compared include ETO, different variants of SPO+ (SPO+ DM, SPO+ DR PI, SPO+ DR Lambda, SPO+ DR Clip), and naive versions of ETO and SPO+. The correctly specified models provide a baseline for comparison.

This table presents the average relative regret ratio for various methods across 50 replications. The results are categorized by the size of the training data (400, 1000, 1600) and the method used (ETO, SPO+ variations, and Naive approaches). A correctly specified policy-inducing model and nuisance model are assumed, and a random logging policy is employed. The relative regret is calculated as a ratio to the expected cost of the globally optimal policy. Lower values indicate better performance.

This table presents the average relative regret ratio for various methods in a contextual linear optimization problem. The results are based on 50 replications of the experiment and show the performance when both the policy-inducing model and the nuisance model are correctly specified. The experiment uses a random logging policy to select decisions.

This table presents the average relative regret ratio for various methods across 50 replications, under the condition that both the policy-inducing model and the nuisance model are correctly specified. The results are categorized by the size of the training data (400, 1000, and 1600). A random policy is used as the logging policy. The relative regret is calculated as the ratio of the method’s regret to the expected cost of the globally optimal policy.

This table shows the average relative regret ratio for various methods in a contextual linear optimization problem with bandit feedback. The results are based on 50 replications of the experiment, and show the performance when both the model used to induce the policy and the nuisance model are correctly specified. The logging policy used to generate the data is a random policy. The lower the regret ratio, the better the method’s performance.

This table presents the average relative regret ratios for various methods in a contextual linear optimization problem with bandit feedback. The results are based on 50 replications of the experiment and show the performance when both the model used to induce the policy and the nuisance model are correctly specified. The logging policy, which determines how decisions are made in the data collection process, is a random policy.

This table presents the average relative regret ratio for various methods across 50 replications. The policy-inducing model and nuisance model are correctly specified. The results are separated by training data size (400, 1000, 1600) and show the performance when using a random logging policy.

Full paper#