↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning, while promising for privacy-preserving machine learning, faces vulnerability to gradient inversion attacks. Existing attacks reconstruct training data accurately only for single data points (batch size 1), falling short for larger batches. This limitation hinders accurate privacy risk assessment and motivates the need for new defense mechanisms.

The research introduces SPEAR, a novel algorithm that addresses this issue. By exploiting the unique low-rank structure and sparsity of gradients in ReLU networks, SPEAR reconstructs entire data batches accurately and efficiently, even with high-dimensional data. The algorithm incorporates a sampling-based approach, leveraging ReLU-induced sparsity to filter out noise and improve reconstruction accuracy. SPEAR’s efficiency is further enhanced through GPU parallelization. The findings demonstrate that exact reconstruction is possible for batch sizes significantly larger than previously assumed, pushing the boundaries of privacy risk assessment in federated learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common assumption that reconstructing data from gradients is infeasible for batch sizes greater than 1 in federated learning. This opens up new avenues for research into improving data privacy and security in federated learning systems. It also provides a new benchmark for evaluating and improving the robustness of these systems against gradient inversion attacks.

Visual Insights#

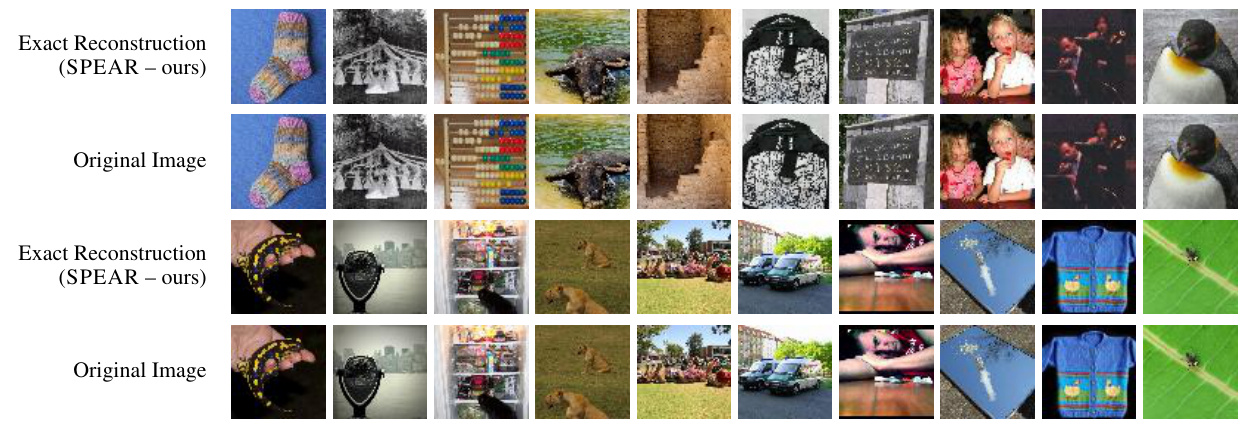

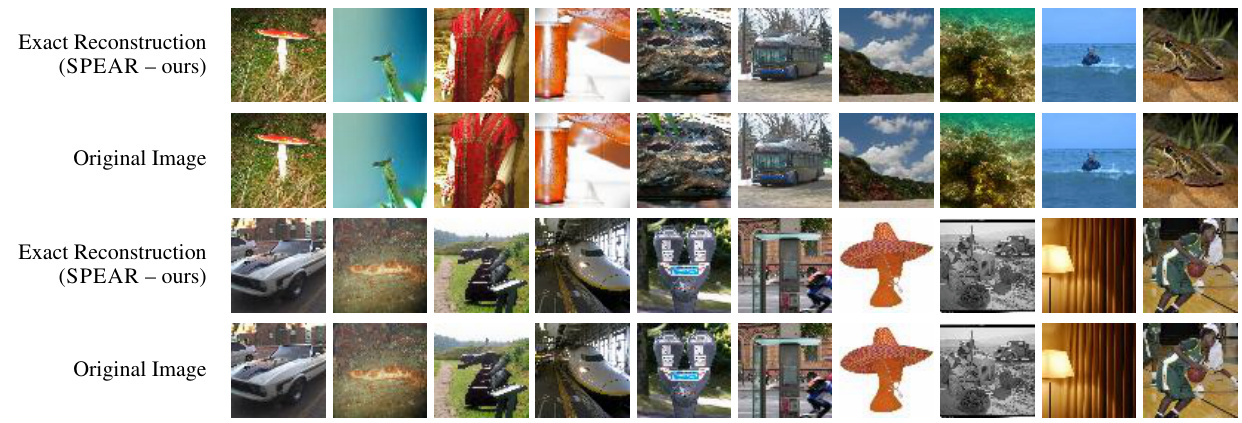

This figure shows a comparison of image reconstruction results from a batch of 20 images using three different methods: SPEAR (the proposed method), the previous state-of-the-art method by Geiping et al. [1], and the ground truth. The top row displays the images reconstructed by SPEAR, showing near-perfect reconstruction. The middle row shows the approximate reconstructions from the Geiping et al. method, which are noticeably blurrier and less accurate. The bottom row shows the original images.

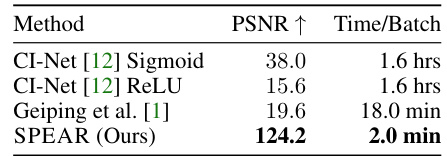

This table compares SPEAR’s performance against prior gradient inversion attacks on the ImageNet dataset. It shows that SPEAR achieves significantly higher PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) values, indicating better reconstruction quality, and is substantially faster than the other methods.

In-depth insights#

Exact Gradient Inversion#

The concept of “Exact Gradient Inversion” in the context of federated learning is a significant development in the field of privacy-preserving machine learning. Traditional gradient inversion attacks often resulted in only approximate reconstructions of the original data, especially when dealing with batches of multiple data samples (b>1). The primary challenge lies in the complexity of disentangling the aggregated gradients to isolate individual data points’ contributions. This novel approach achieves exact reconstruction of entire data batches, representing a substantial improvement over existing techniques and potentially posing a severe threat to the privacy guarantees of federated learning systems. The success hinges on leveraging the inherent low-rank structure and ReLU-induced sparsity within gradients, allowing for efficient filtering of incorrect samples and tractable reconstruction. While the computational cost scales exponentially with batch size, the authors demonstrate that the algorithm remains practical for surprisingly large batches, especially with GPU implementation. This work highlights the vulnerability of federated learning models to sophisticated attacks and emphasizes the need for stronger privacy-preserving mechanisms. Further research should investigate the algorithm’s robustness and its applicability to other neural network architectures beyond fully connected networks using ReLU activations.

ReLU-Induced Sparsity#

The concept of “ReLU-Induced Sparsity” centers on the observation that the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, commonly used in neural networks, introduces sparsity into the gradients. ReLU’s inherent thresholding nature (outputting zero for negative inputs and the input value otherwise) leads to many zero values in the gradients, particularly in the early layers of a network. This sparsity is not random; it’s structured and reflects the activation patterns of the neurons. This sparsity is crucial because it allows for a more efficient and precise gradient inversion attack. By exploiting the zero values, the algorithm can filter out a significant number of incorrect candidate directions, making the reconstruction of the original input data significantly more computationally feasible. The low-rank structure of the gradients, combined with ReLU-induced sparsity, forms the foundation of the SPEAR algorithm’s effectiveness. It’s a key property that distinguishes this approach from prior techniques relying solely on approximate reconstruction or only applicable to batch sizes of 1. The efficient exploitation of this sparsity is a major contribution of the research paper.

SPEAR Algorithm#

The SPEAR algorithm, designed for gradient inversion attacks in federated learning, is a novel approach that enables exact reconstruction of entire data batches, a significant advancement over previous methods limited to single-datapoint recovery. Its core innovation lies in leveraging the inherent low-rank structure of gradients from ReLU-activated networks and the sparsity induced by the ReLU activation function. SPEAR employs a sampling-based strategy to efficiently filter out incorrect candidate datapoints, followed by a greedy optimization step to refine the results. While computationally expensive for large batch sizes (scaling exponentially), its GPU implementation demonstrates feasibility for batches up to size 25, even with high-dimensional datasets and complex network architectures. This is a considerable step forward in gradient inversion attacks, challenging previously held assumptions about the infeasibility of exact batch reconstruction.

Empirical Evaluation#

The Empirical Evaluation section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made in the theoretical sections. A robust empirical evaluation should demonstrate that the proposed method performs as expected, ideally outperforming existing state-of-the-art approaches. Key aspects to consider are the datasets used, ensuring they are relevant, representative and publicly available to foster reproducibility. The evaluation metrics should be carefully chosen to reflect the specific goals of the research, and the results should be presented clearly, often with visualizations and statistical significance measures. Reproducibility is paramount, so the paper should provide sufficient detail on the experimental setup, including hyperparameters, training procedures, and hardware resources used. A thorough ablation study, testing variations of the proposed method, helps to isolate the contributions of different components and enhance the understanding of the results. Finally, a comparison with benchmark algorithms is essential, showcasing the method’s advantages and limitations in a broader context.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending SPEAR’s applicability beyond fully connected ReLU networks to convolutional or recurrent architectures, which are more prevalent in modern deep learning. Addressing the exponential scaling with batch size is crucial; investigating approximation techniques or alternative sampling strategies could make SPEAR more practical for larger batches. The robustness of SPEAR against various defense mechanisms, such as differential privacy or adversarial training, requires further investigation. A comparative analysis of SPEAR against other gradient inversion attacks focusing on efficiency, accuracy, and robustness would also provide valuable insights. Finally, exploring the implications of SPEAR in different federated learning settings, such as those with non-IID data distributions or more complex communication protocols, is an important avenue for future work. The potential for SPEAR to be used in privacy-preserving machine learning methods requires further exploration, with focus on the development of countermeasures that mitigate the risks highlighted by SPEAR.

More visual insights#

More on figures

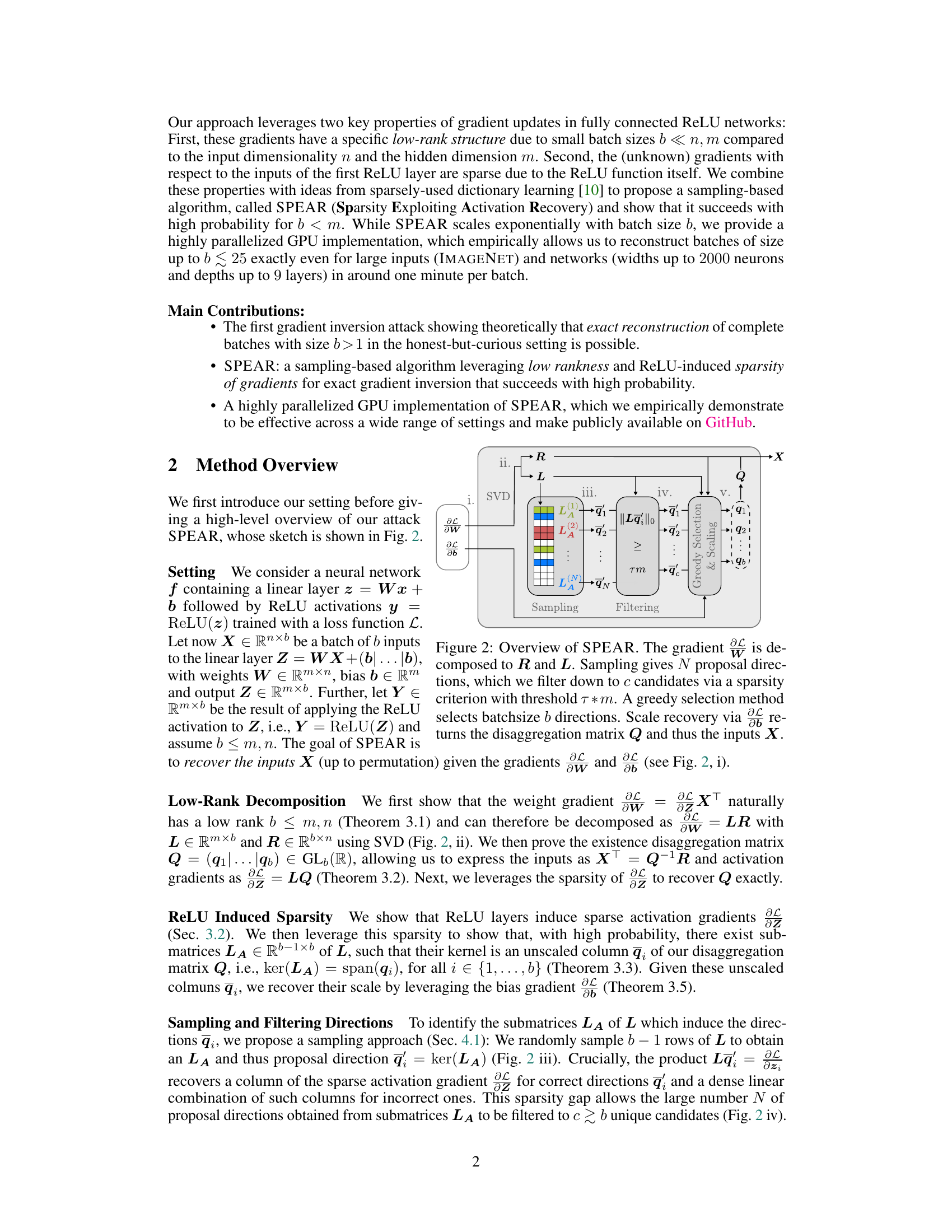

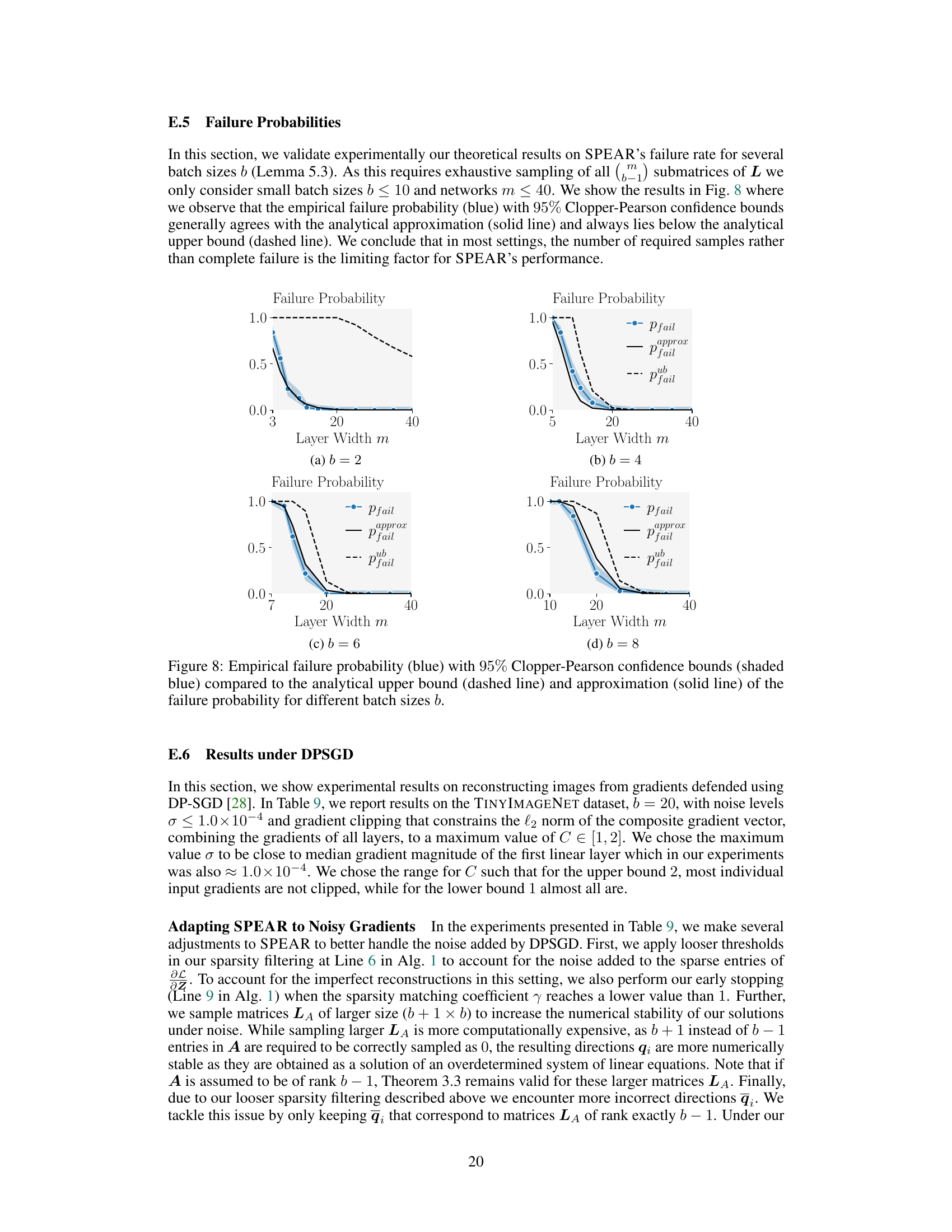

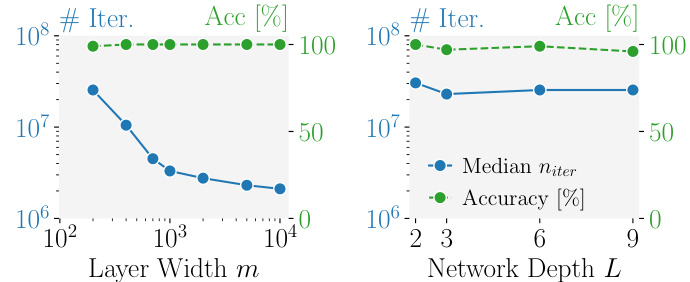

This figure illustrates the SPEAR algorithm’s workflow. It begins with singular value decomposition (SVD) of the gradient, then samples and filters proposal directions based on sparsity. A greedy selection method picks the best directions and scales them for final input recovery using the disaggregation matrix Q. The low rank and sparsity properties of the gradient in ReLU networks are utilized in this process.

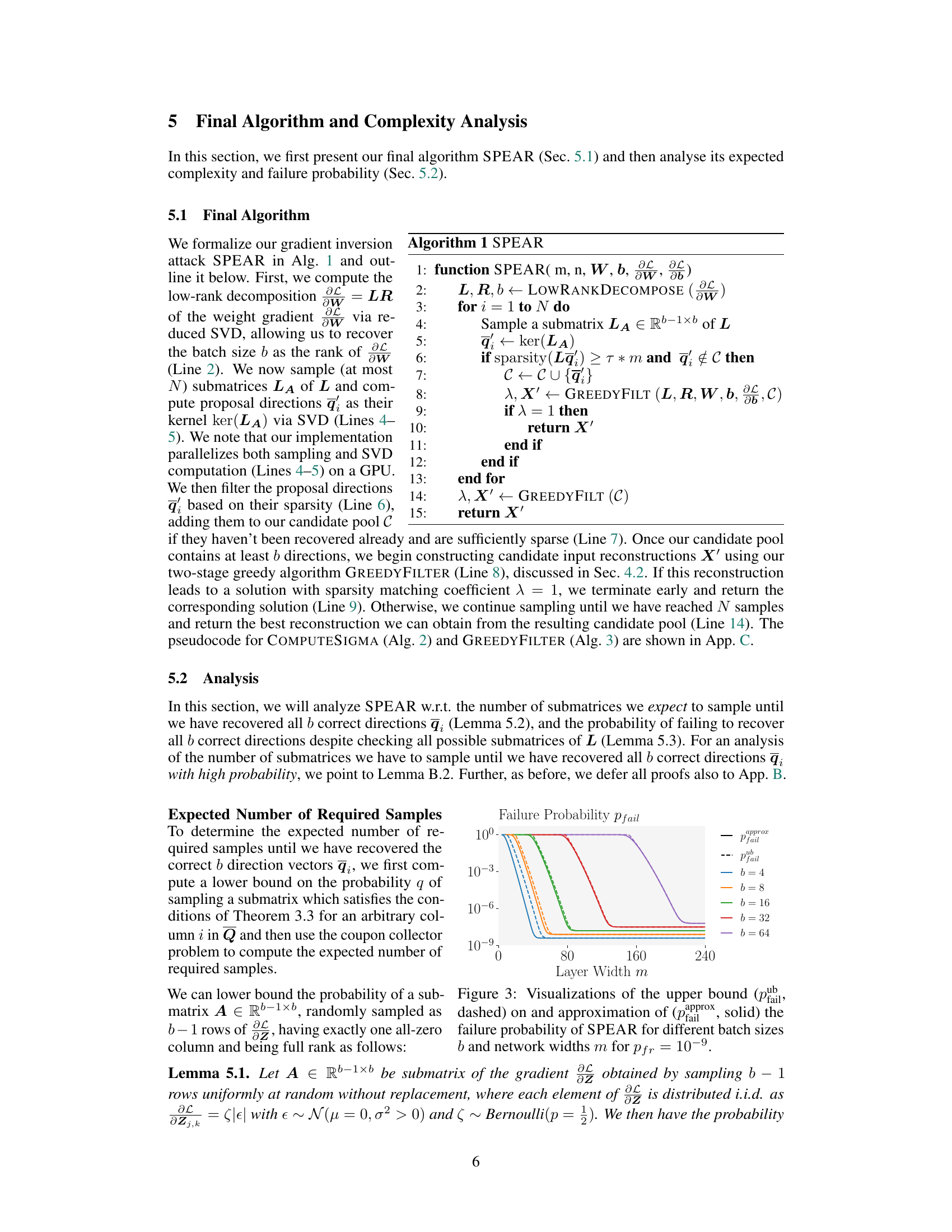

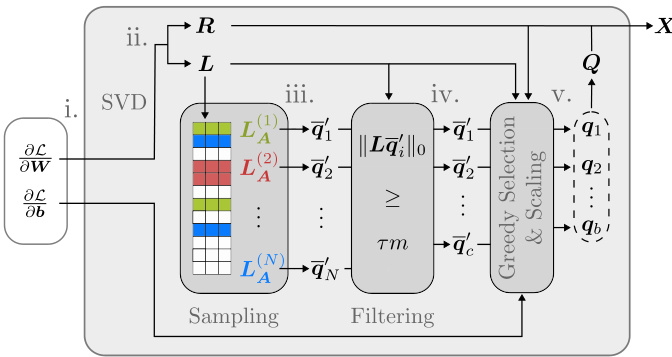

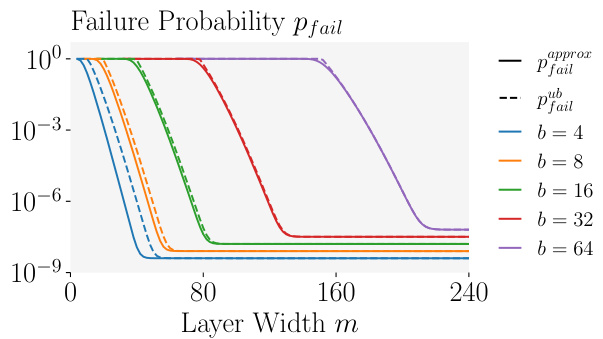

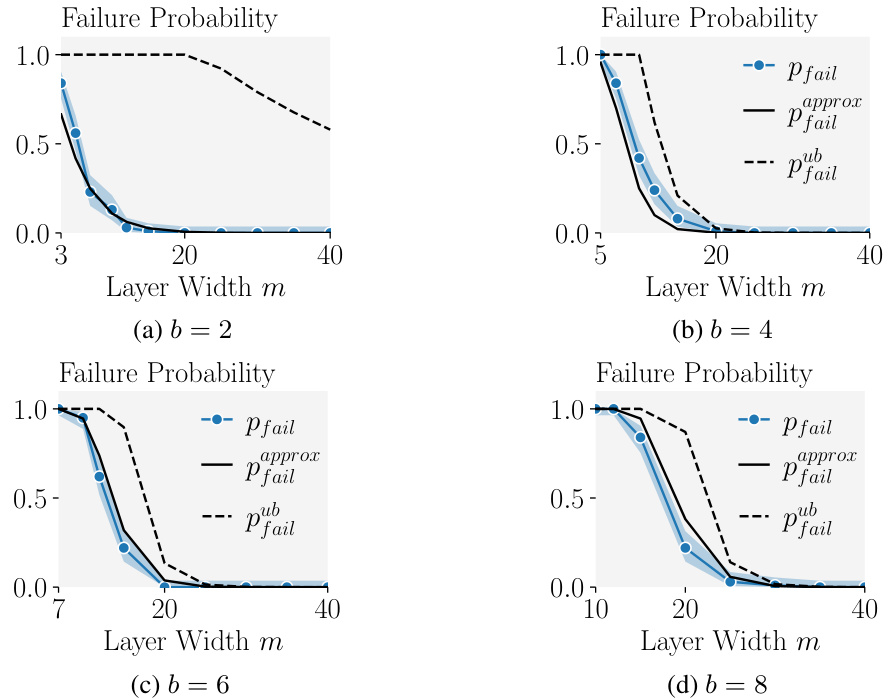

This figure shows the theoretical upper bound and approximation of the failure probability for SPEAR, which is the algorithm for reconstructing input data from gradients in federated learning. The failure probability is plotted against the network width (m) for different batch sizes (b). The dashed lines represent the theoretical upper bound, while the solid lines show an approximation. The graph illustrates how the probability of SPEAR failing to reconstruct the data decreases as the network width increases and the batch size decreases.

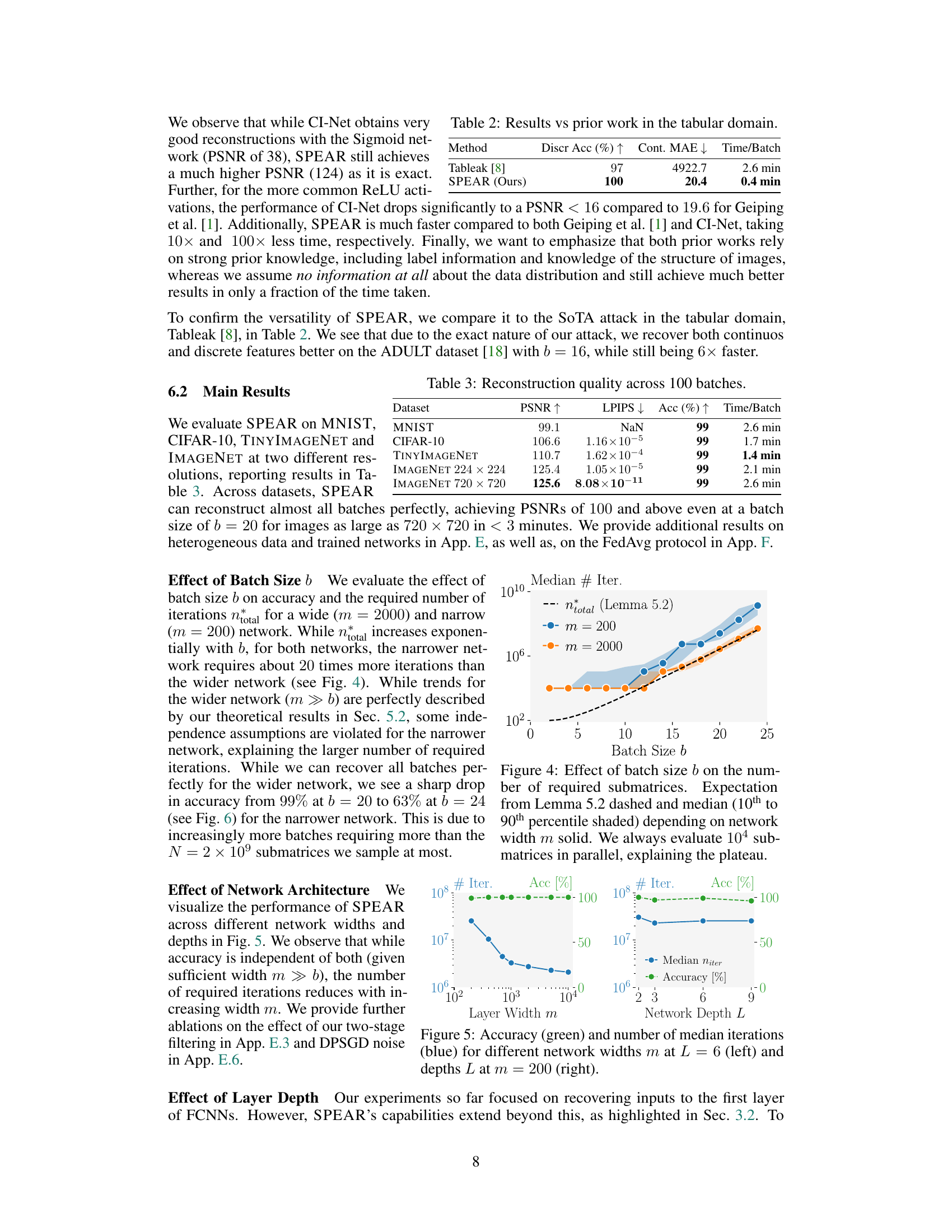

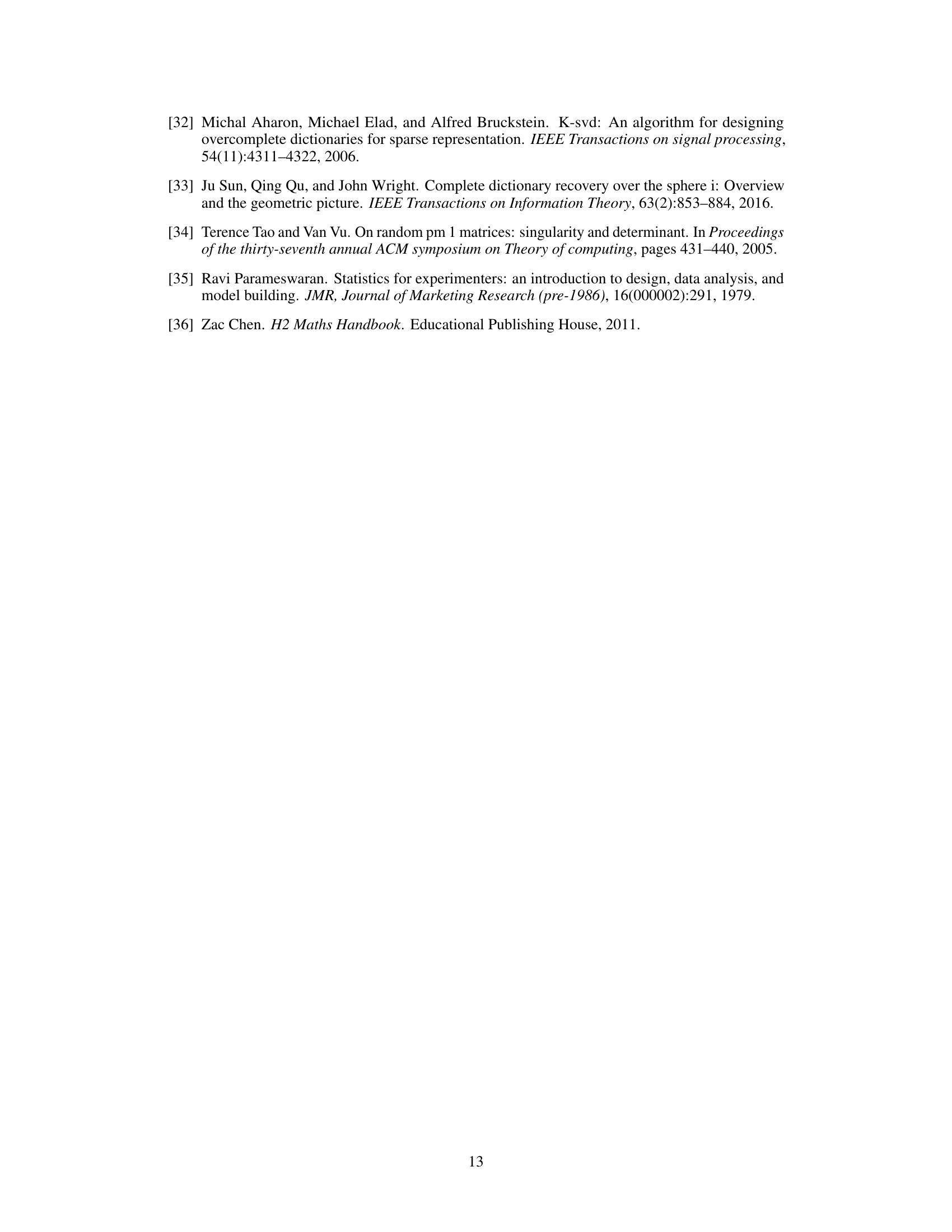

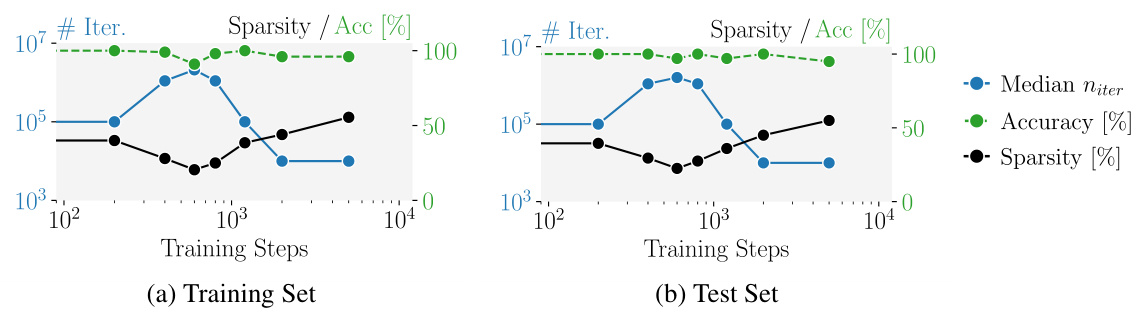

The figure shows how the number of submatrices that need to be sampled until all correct directions are found depends on the batch size and the network width. The dashed line represents the theoretical expectation from Lemma 5.2. The shaded areas represent the 10th to 90th percentiles of the median number of iterations observed in experiments. The solid lines show the median number of iterations observed in experiments for network widths of 200 and 2000. The plateau at the end is due to the parallelization used in the algorithm where 10,000 submatrices are evaluated at once.

This figure shows how the number of submatrices that need to be sampled to recover all b correct directions varies with the batch size b and network width m. The dashed line represents the expectation derived from Lemma 5.2, while the solid lines and shaded regions show the median and 10th-90th percentiles from experimental results. The plateau in the graph is explained by the fact that 104 submatrices are always evaluated in parallel, limiting the impact of increasing batch size beyond a certain point.

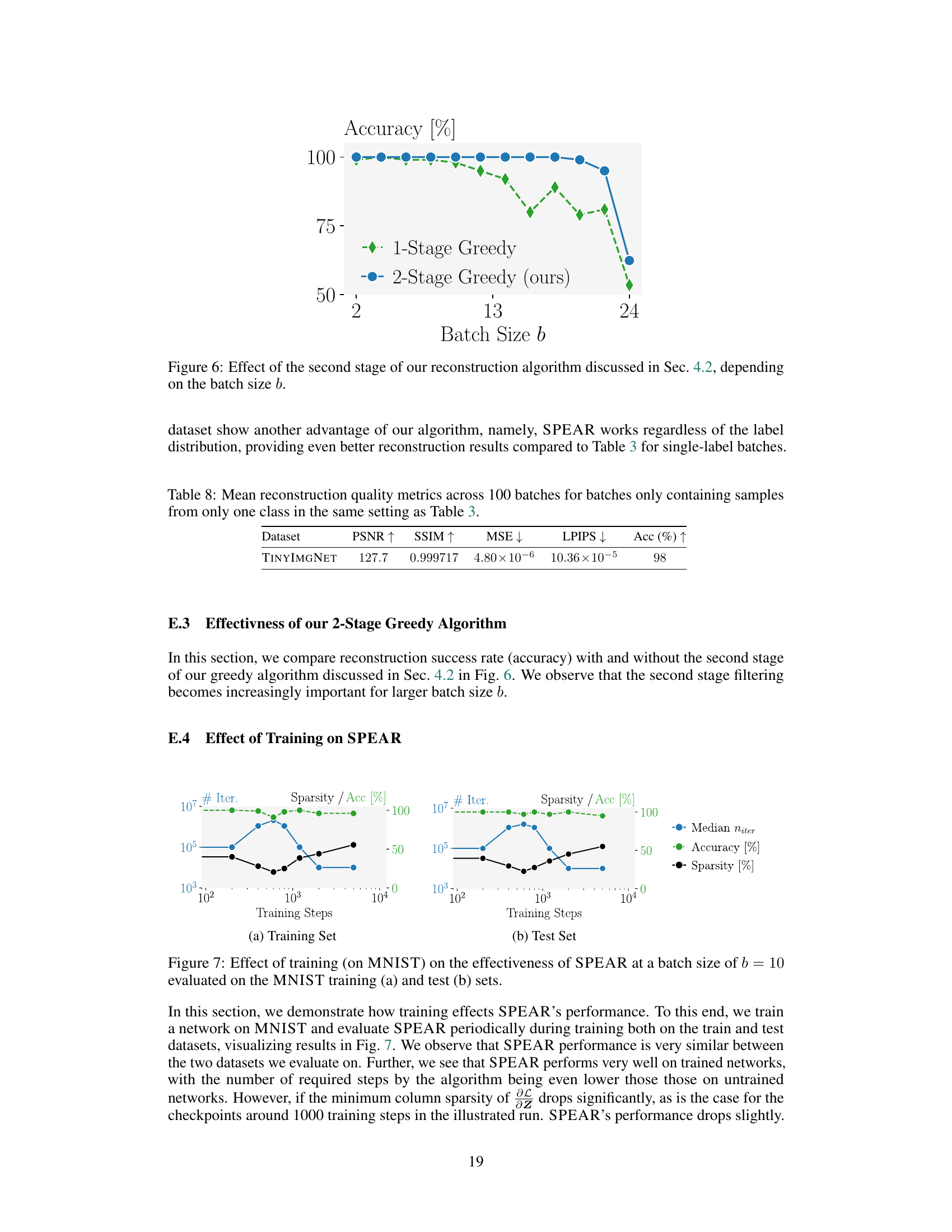

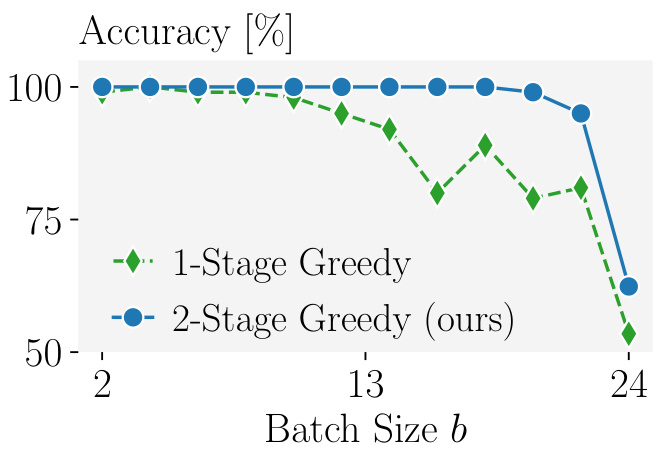

The figure shows the impact of adding a second greedy optimization stage to the SPEAR algorithm. The x-axis represents the batch size (b), and the y-axis shows the accuracy of the reconstruction. Two lines are plotted: one for a single-stage greedy approach and one for the two-stage greedy approach (SPEAR). The results indicate that the two-stage approach significantly improves accuracy, especially as the batch size increases. The improvement highlights the benefit of the additional filtering and optimization steps incorporated in SPEAR to select the most accurate reconstruction from multiple candidates.

The figure shows the impact of batch size (b) on the number of submatrices that need to be sampled to recover all the correct directions. It compares the theoretical expectation from Lemma 5.2 (dashed line) with empirical results (solid line and shaded area representing the 10th to 90th percentiles). The experiment used 10,000 submatrices in parallel, which explains why the curve plateaus.

This figure shows the theoretical upper bound and an approximation of the failure probability for SPEAR, which is the first algorithm to reconstruct batches with b > 1 exactly. The plot displays how the failure probability changes based on the batch size (b) and the network width (m), with a fixed false rejection rate (pfr) of 10^-9. The dashed line represents the theoretical upper bound, while the solid line is an approximation of the actual failure probability. This illustrates the algorithm’s performance and its dependence on network architecture.

This figure compares the image reconstruction quality of SPEAR with the prior state-of-the-art method (Geiping et al. [1]) for a batch of 20 images (b=20). The top row shows the images reconstructed using SPEAR. The middle row displays the results from Geiping et al. [1]. The bottom row presents the original ground truth images. This comparison visually demonstrates SPEAR’s superior accuracy in reconstructing images from gradients, even for larger batch sizes.

This figure shows a comparison of image reconstruction results using three different methods: the proposed SPEAR method, the previous state-of-the-art method by Geiping et al. [1], and the original images. It demonstrates that SPEAR achieves significantly better reconstruction quality for a batch of 20 images (b=20) than the prior art.

This figure shows a comparison of image reconstruction results from three different methods: The authors’ proposed method SPEAR, a previous state-of-the-art method by Geiping et al. [1], and the original images. The top row displays images reconstructed by SPEAR, the middle row those by Geiping et al., and the bottom row shows the original images. This visually demonstrates that SPEAR achieves much better reconstruction than Geiping et al., and that the reconstructions from SPEAR are very close to the original images, even when the batch size (number of images processed simultaneously) is 20.

This figure shows a comparison of image reconstruction results using three different methods: SPEAR (the proposed method), the previous state-of-the-art method (Geiping et al.), and the ground truth. The top row shows images reconstructed using SPEAR, the middle row shows images reconstructed using Geiping et al.’s method, and the bottom row shows the original images. The batch size used in this reconstruction is 20, highlighting the capability of SPEAR to reconstruct images in larger batches compared to the previous method.

This figure shows a comparison of image reconstruction results using three different methods: SPEAR (the proposed method), the previous state-of-the-art method by Geiping et al. [1], and the ground truth images. The top row shows images reconstructed using SPEAR, the middle row shows images reconstructed using Geiping et al.’s method, and the bottom row shows the original images. The figure demonstrates that SPEAR achieves more accurate reconstruction than the existing method for a batch size of 20.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of SPEAR against two other gradient inversion attack methods (CI-Net and Geiping et al.) on the ImageNet dataset. The comparison considers the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), which is a metric for image reconstruction quality. Higher PSNR indicates better reconstruction quality. The table also compares the time each method takes to reconstruct one batch of images. SPEAR significantly outperforms the other methods in terms of PSNR and speed.

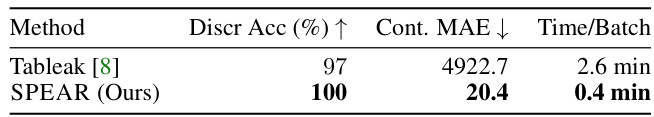

This table compares SPEAR’s performance against Tableak [8], a state-of-the-art gradient inversion attack in the tabular domain, on the ADULT dataset. It evaluates the methods based on three metrics: Discrete Accuracy (Discr Acc %), measuring the percentage of correctly classified discrete features; Continuous Mean Absolute Error (Cont. MAE), indicating the average absolute difference between the reconstructed and original values for continuous features; and Time/Batch, showing the time taken for reconstruction per batch of data.

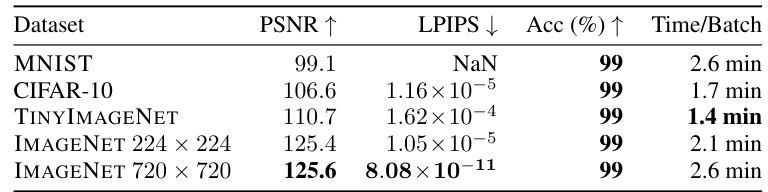

This table presents the reconstruction quality metrics (PSNR, LPIPS, Accuracy) and time per batch for different datasets (MNIST, CIFAR-10, TinyImageNet, and IMAGENET at two resolutions). It showcases the effectiveness of SPEAR in achieving near-perfect reconstruction (99% accuracy) across various datasets and image sizes.

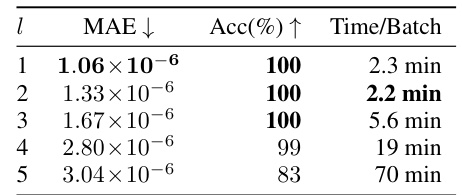

This table shows the effect of targeting different layers of a neural network (from the first layer to the fifth) on the reconstruction performance of the SPEAR algorithm. The results demonstrate that while SPEAR successfully reconstructs inputs to all layers, the computation time increases significantly as the target layer moves deeper into the network. It also shows a drop in reconstruction accuracy as the target layer is deeper. The results are based on 100 batches of images from the TINYIMAGENET dataset, each batch containing 20 images.

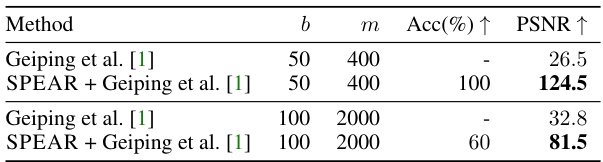

This table compares the reconstruction quality (accuracy and PSNR) achieved by Geiping et al.’s method and a modified version of SPEAR that incorporates Geiping et al.’s approach to enhance its search efficiency. The comparison is performed on 10 batches from the TINYIMAGENET dataset for two different network sizes (m=400 and m=2000) and batch sizes (b=50 and b=100). It shows that SPEAR, when combined with the optimization of Geiping et al. can achieve significantly better PSNR values.

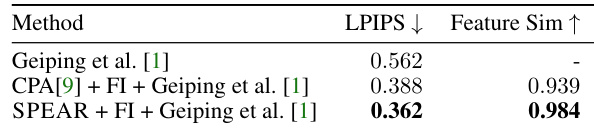

This table compares the reconstruction quality of three different methods on the ImageNet dataset using a VGG16 convolutional neural network. The methods compared are Geiping et al. [1] (a baseline approximate reconstruction method), CPA [9] + FI + Geiping et al. [1] (Cocktail Party Attack with Feature Inversion using Geiping et al. [1] for feature recovery), and SPEAR + FI + Geiping et al. [1] (the proposed method SPEAR combined with Feature Inversion and Geiping et al. [1]). The quality is assessed using two metrics: LPIPS (lower is better) and Feature Similarity (higher is better). The results show that SPEAR, combined with the other methods, achieves the best performance in both metrics, indicating superior reconstruction quality.

This table compares SPEAR’s performance against two prior gradient inversion attacks (CI-Net and Geiping et al.) on the ImageNet dataset. It shows that SPEAR achieves significantly higher PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) values, indicating much better reconstruction quality, and is also substantially faster. The comparison highlights SPEAR’s superiority in terms of both accuracy and efficiency.

This table presents the mean reconstruction quality metrics (PSNR, SSIM, MSE, LPIPS, and Accuracy) for 100 batches of images from the TINYIMAGENET dataset. A key characteristic of these batches is that they only contain samples from a single class (label-homogeneous data). The results are compared against those from Table 3, which uses heterogeneous data.

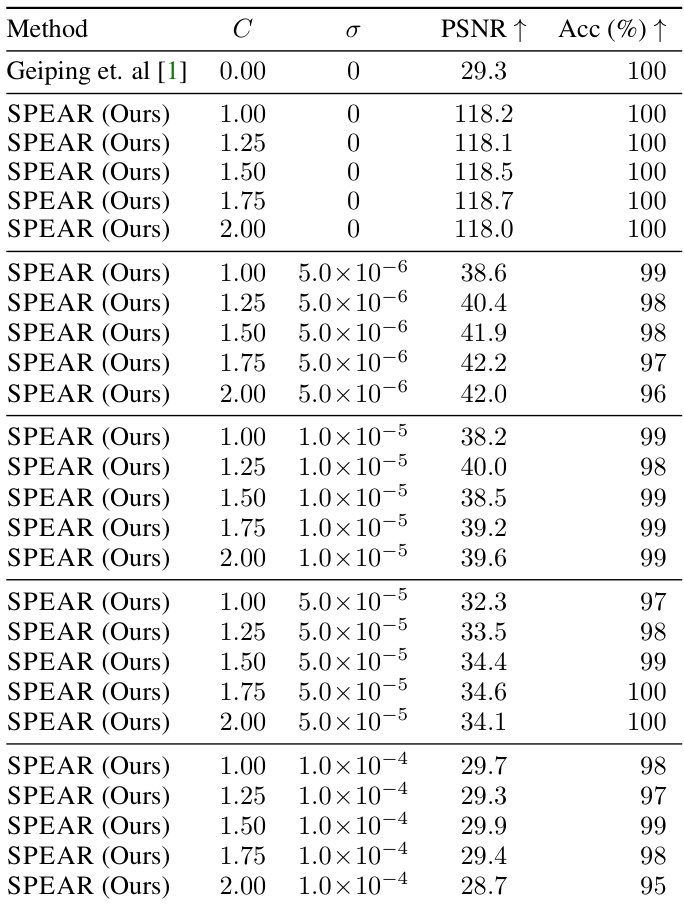

This table presents the results of reconstruction experiments using the SPEAR algorithm on the TINYIMAGENET dataset. The experiments involved adding different levels of noise (σ) and gradient clipping (C) to the gradients during training using the DP-SGD defense mechanism. The table shows the PSNR and accuracy achieved by the SPEAR algorithm under various noise and clipping conditions. It demonstrates the robustness of the SPEAR algorithm to noise and clipping.

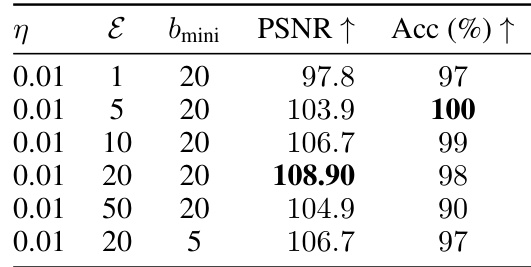

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of SPEAR against the FedAvg algorithm. The experiment varied the number of local client epochs (ε), and the size of mini-batches (bmini) used in the FedAvg updates while keeping the total number of data points used in each local update fixed at b=20. The PSNR and accuracy are reported for each configuration. This demonstrates SPEAR’s robustness and effectiveness even when applied to aggregated gradients from multiple local update steps.

This table presents the reconstruction quality (PSNR and Accuracy) achieved by SPEAR on the TINYIMAGENET dataset using FedAvg updates. It shows the results for 100 batches of size 20, varying the local learning rate (η) across three values (0.1, 0.01, 0.001). The number of local epochs (E) and mini-batch size (bmini) are kept constant at 5 and 20 respectively. The table demonstrates the robustness of SPEAR’s performance across different learning rates.

Full paper#