↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Visual processing in the brain is complex. While primary visual cortex (V1) neurons are often thought of as edge detectors, the role of pinwheel structures, a distinctive feature of higher mammal V1, is poorly understood. Previous work lacked a clear understanding of the functional advantages of pinwheels compared to other V1 organizations. This paper addresses these issues by exploring the functional roles of pinwheels using a combination of biological data and computational modeling.

The researchers developed a two-dimensional self-evolving spiking neural network (SESNN) model to simulate the development of orientation preference maps, ranging from simple salt-and-pepper organizations to complex pinwheels. They found that pinwheel centers function as first-order processors rapidly detecting complex contours and geometric saliency, which enables improved processing of complex textures in natural images. This innovative model provides a new framework for understanding the function of the visual cortex and offers new possibilities for designing more biologically plausible AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important as it provides novel insights into the functional role of visual cortical structures, particularly pinwheel centers, in processing complex visual information. This will have significant implications for research in neuroscience, computer vision, and artificial intelligence, opening new avenues for building biologically plausible and high-performing visual systems. The use of a novel 2D self-evolving spiking neural network to model orientation preference maps is also a noteworthy contribution.

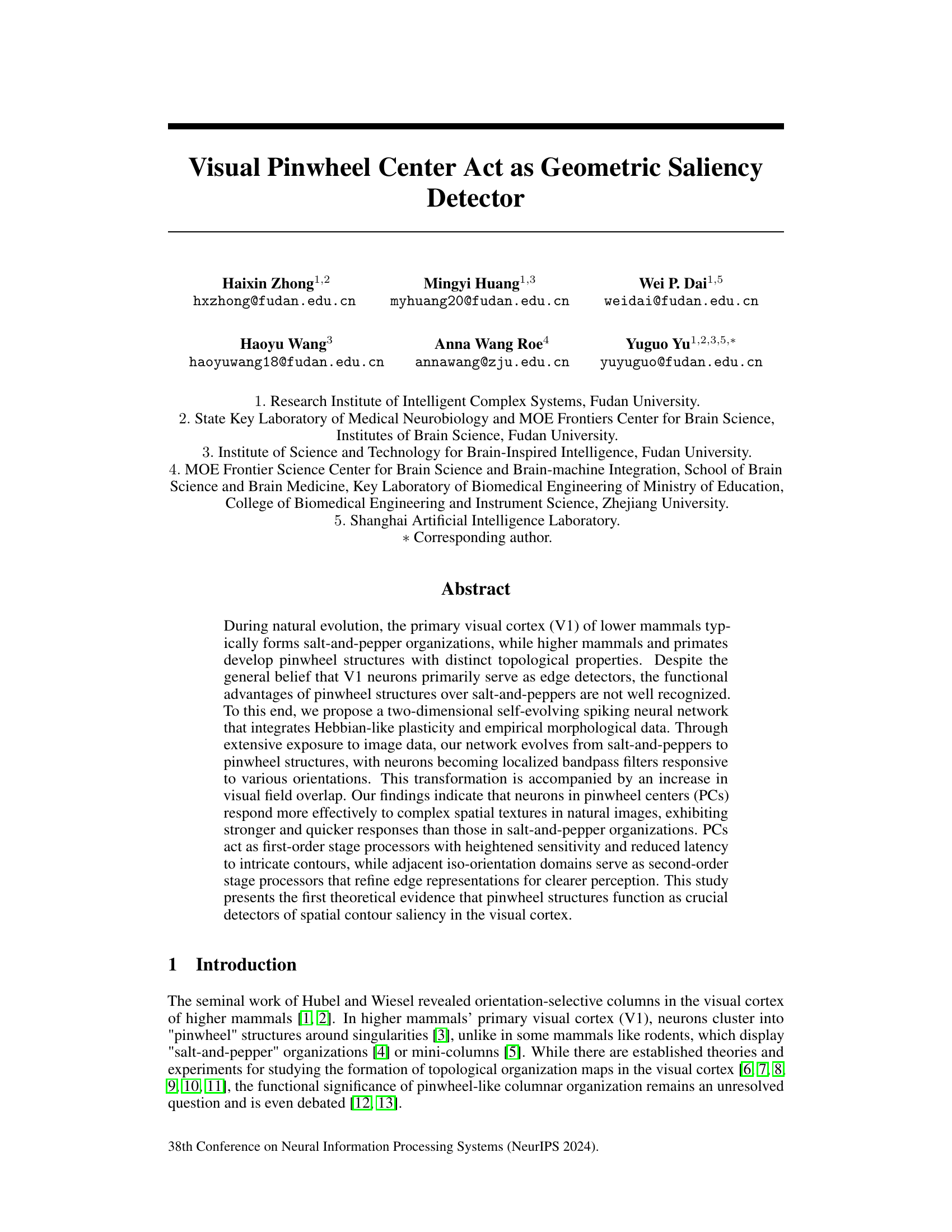

Visual Insights#

This figure shows how the visual overlap among neighboring neurons affects the organization of orientation preference maps (OPMs) in a spiking neural network model. It demonstrates the transition from salt-and-pepper to pinwheel structures as visual overlap increases. Furthermore, it compares the model’s OPM characteristics to those observed in actual anatomical data from different species (mice, cats, and macaques), showing a strong correlation between visual overlap and the development of pinwheel structures. Finally, it illustrates the relationship between iso-orientation domain (IOD) size and visual field extent across species.

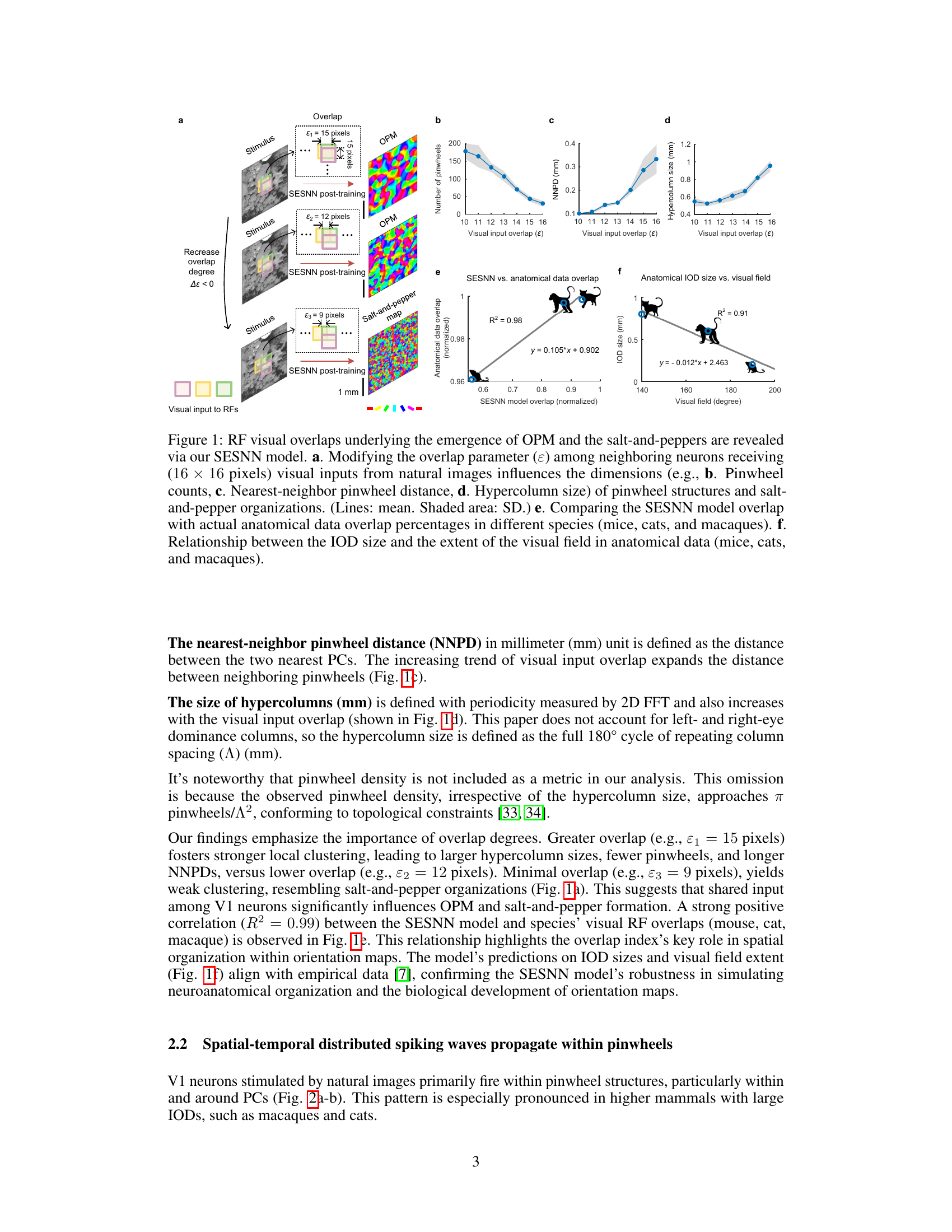

This table compares the quantitative results of the SESNN model to actual anatomical data from macaques. It shows a comparison of three key metrics: pinwheel density (the number of pinwheels per unit area), nearest-neighbor pinwheel distance (NNPD), and hypercolumn size. The SESNN model’s results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, showing the model’s ability to generate results consistent with biological observations.

In-depth insights#

Pinwheel Structure#

The research paper explores the fascinating “Pinwheel Structure” observed in the primary visual cortex (V1), focusing on its functional role as a geometric saliency detector. The analysis reveals that pinwheel centers (PCs), unlike iso-orientation domains (IODs), respond more effectively to complex spatial textures, exhibiting stronger and faster responses. This suggests PCs act as first-order processors, initiating spiking waves that subsequently refine edge representations in the IODs as second-order processors. The study’s novel self-evolving spiking neural network model demonstrates the developmental transition from salt-and-pepper to pinwheel organizations and underscores the evolutionary advantage of pinwheel structures for processing complex visual information. The visual overlap between neurons is highlighted as a crucial factor influencing the emergence of pinwheel structures, while a bimodal ratio analysis further supports the unique orientation tuning properties of PCs compared to IODs. Overall, the paper provides compelling evidence that the pinwheel structure isn’t merely a curious anatomical feature, but a key functional component for efficient and rapid geometric saliency detection in the visual cortex.

SESNN Model#

The Self-Evolving Spiking Neural Network (SESNN) model is a crucial component of the research, offering a novel computational approach to model the development of orientation preference maps (OPMs) in the visual cortex. Its unique self-organizing nature allows the network to evolve from simple, salt-and-pepper OPMs to complex pinwheel structures, mirroring the developmental trajectory observed in biological systems. This evolution is driven by Hebbian-like plasticity and the integration of empirical morphological data, demonstrating the power of biologically-constrained computational modeling. The SESNN model not only replicates observed OPM structures but also sheds light on the functional roles of pinwheel centers (PCs) as geometric saliency detectors, underscoring the importance of visual field overlap in shaping OPM organization and revealing distinct processing hierarchies between PCs and iso-orientation domains (IODs). By simulating spatial-temporal spiking dynamics, the model provides valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underpinning visual perception.

Saliency Detection#

The concept of saliency detection, crucial to visual attention and perception, is significantly explored within the context of the visual pinwheel’s structure. The research posits that pinwheel centers (PCs), unlike iso-orientation domains, function as geometric saliency detectors, exhibiting heightened sensitivity and faster responses to intricate contours in natural images. This suggests that PCs serve as initial processors, rapidly detecting complex spatial patterns, and subsequently forwarding these to adjacent iso-orientation domains for refinement. This hierarchical processing model provides a novel mechanism to understand how the visual cortex efficiently processes visual information. The study’s findings support a functional significance for pinwheel structures in visual processing, suggesting a role beyond simply edge detection. The unique spatial-temporal dynamics within the pinwheel, with information propagating from PCs, also suggest an evolutionarily advantageous system for handling complex visual input.

Spatial Dynamics#

Spatial dynamics in neural systems, especially the visual cortex, are crucial for understanding information processing. Pinwheel structures, characterized by their unique topological organization, play a central role in this. The study reveals how visual input overlap influences the emergence of pinwheel structures, with high overlap promoting pinwheels more effectively than low overlap leading to salt-and-pepper patterns. Pinwheel centers (PCs) act as first-order processors, rapidly detecting complex spatial textures and initiating spiking waves to surrounding domains. These waves propagate within pinwheels and adjacent iso-orientation domains (IODs) act as second-order processors refining edge representation. This spatial-temporal interplay of PCs and IODs enhances the detection of contour saliency. The model highlights the importance of understanding spatial organization and interactions between neurons in the visual cortex for effective processing of visual information.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several avenues. Extending the SESNN model to incorporate additional visual features beyond orientation, such as color and motion, would enhance its biological realism and potentially reveal how these features interact with orientation in shaping complex visual perception. Investigating the model’s robustness to various noise levels and the impact of different learning rules on the emergence of pinwheel structures are also crucial. A deeper analysis of the temporal dynamics of spiking activity within pinwheels could provide insights into the underlying mechanisms of geometric saliency detection. Moreover, exploring the relationships between pinwheel structures and higher-level visual processing areas would illuminate the role of pinwheels in building increasingly complex visual representations. Finally, testing the model’s predictions against data from a wider range of species would further refine our understanding of the evolutionary pressures shaping the development of orientation maps in the visual cortex. These future directions promise to unveil crucial details about the functional organization and computational principles underlying visual processing.

More visual insights#

More on figures

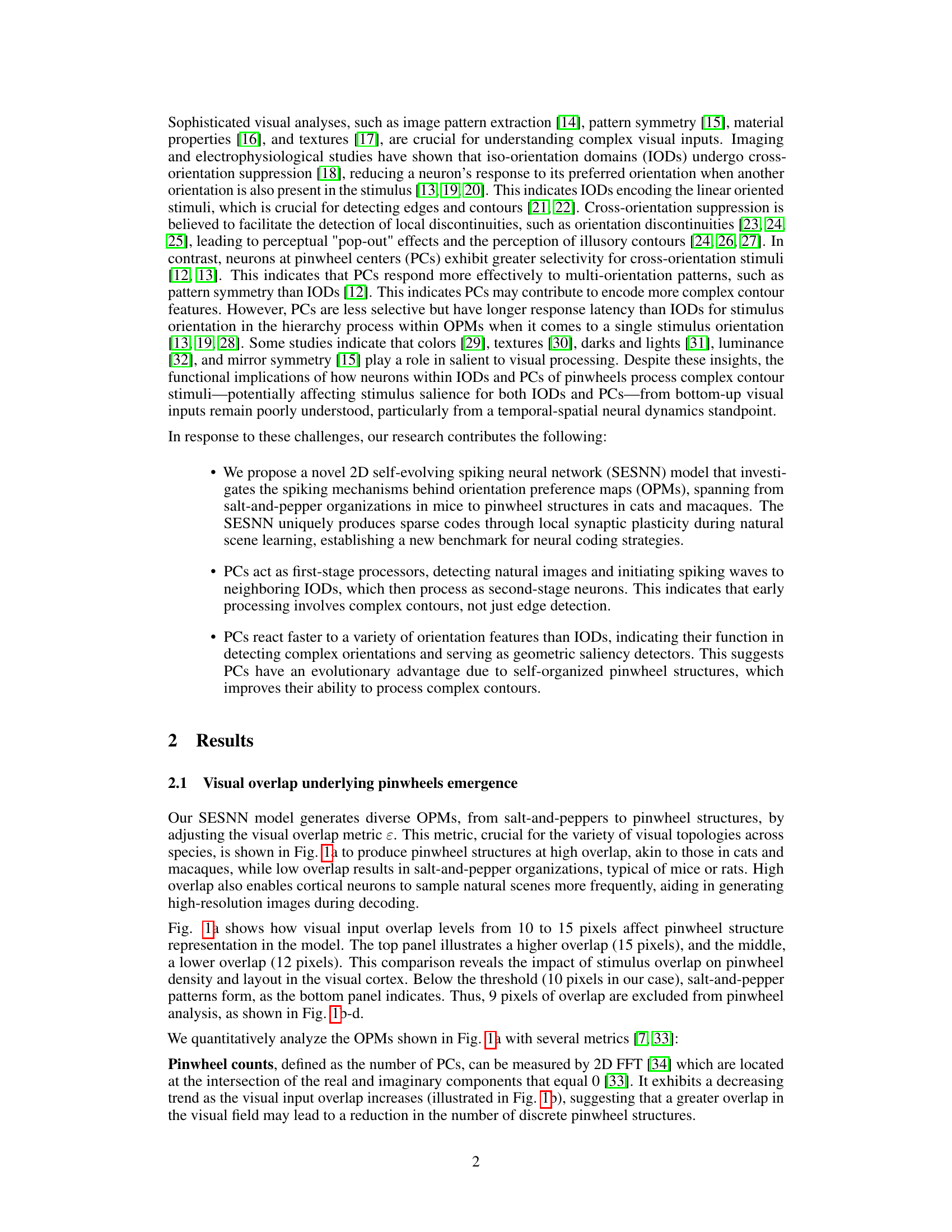

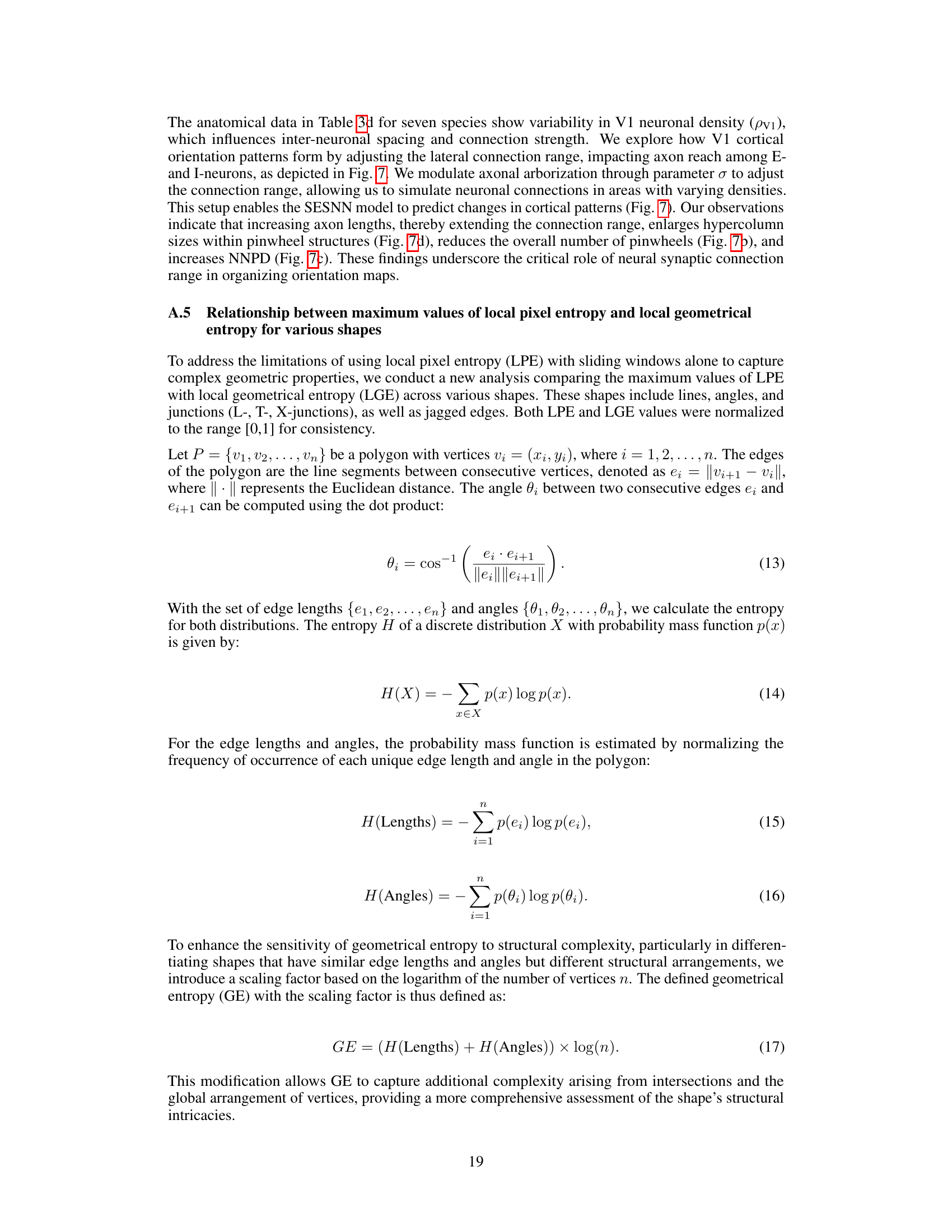

This figure demonstrates the spatiotemporal dynamics of neuronal activation within pinwheel structures. Panel (a) shows an orientation map with a zoomed-in view of a pinwheel, illustrating how neuronal firing initiates at the pinwheel center (PC) at time t0 and propagates outwards to surrounding neurons at time t0+1. Panel (b) presents box plots comparing the distance of firing neurons from the PC at t0 and t0+1, revealing a significant increase in distance at t0+1. Panel (c) displays a scatter plot and linear regression showing a strong positive correlation between the response onset latency and the distance from the PC, indicating a sequential activation pattern originating from the PC.

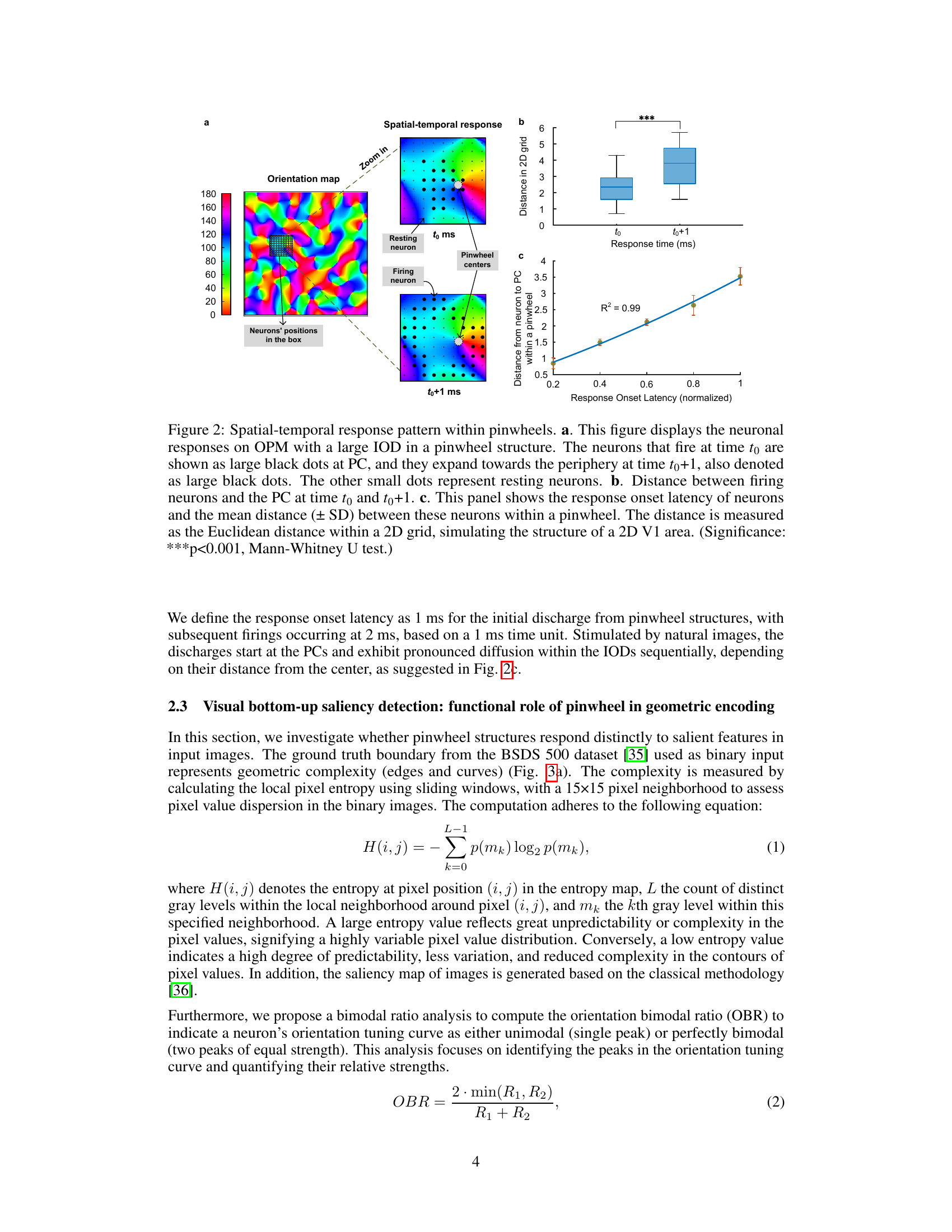

This figure demonstrates that pinwheel structures in the primary visual cortex (V1) exhibit a distinct response to geometric complexity compared to salt-and-pepper structures. Panel (a) shows a sample image from the BSDS500 dataset, along with its binary representation (edges and contours), saliency map, and entropy map. Panel (b) shows a positive correlation between saliency and entropy in natural images, indicating that regions of high geometric complexity are associated with greater saliency. Panel (c) compares the response onset latency (speed of neuronal response) of pinwheel structures and salt-and-pepper structures to stimuli of varying geometric complexity. The results show that pinwheel centers respond faster and stronger to complex contours, highlighting their role as geometric saliency detectors.

This figure demonstrates the geometric properties of pinwheel structures in V1 using star-like patterns as stimuli. Panels (a), (b), (c) show the relationship between saliency, complexity (measured by entropy), and neuronal response latency to the star-like patterns. Panel (d) compares the responses of PCs and IODs, further highlighting the enhanced saliency detection capabilities of PCs. Panel (e) analyzes the orientation bimodality ratio (OBR), showing differences between the OBR of PCs and IODs across various cortical distances. Statistical significance tests are included for each panel. Overall, this figure provides further evidence that pinwheel centers are geometric saliency detectors, responding faster and more robustly to complex stimuli compared to other V1 neurons.

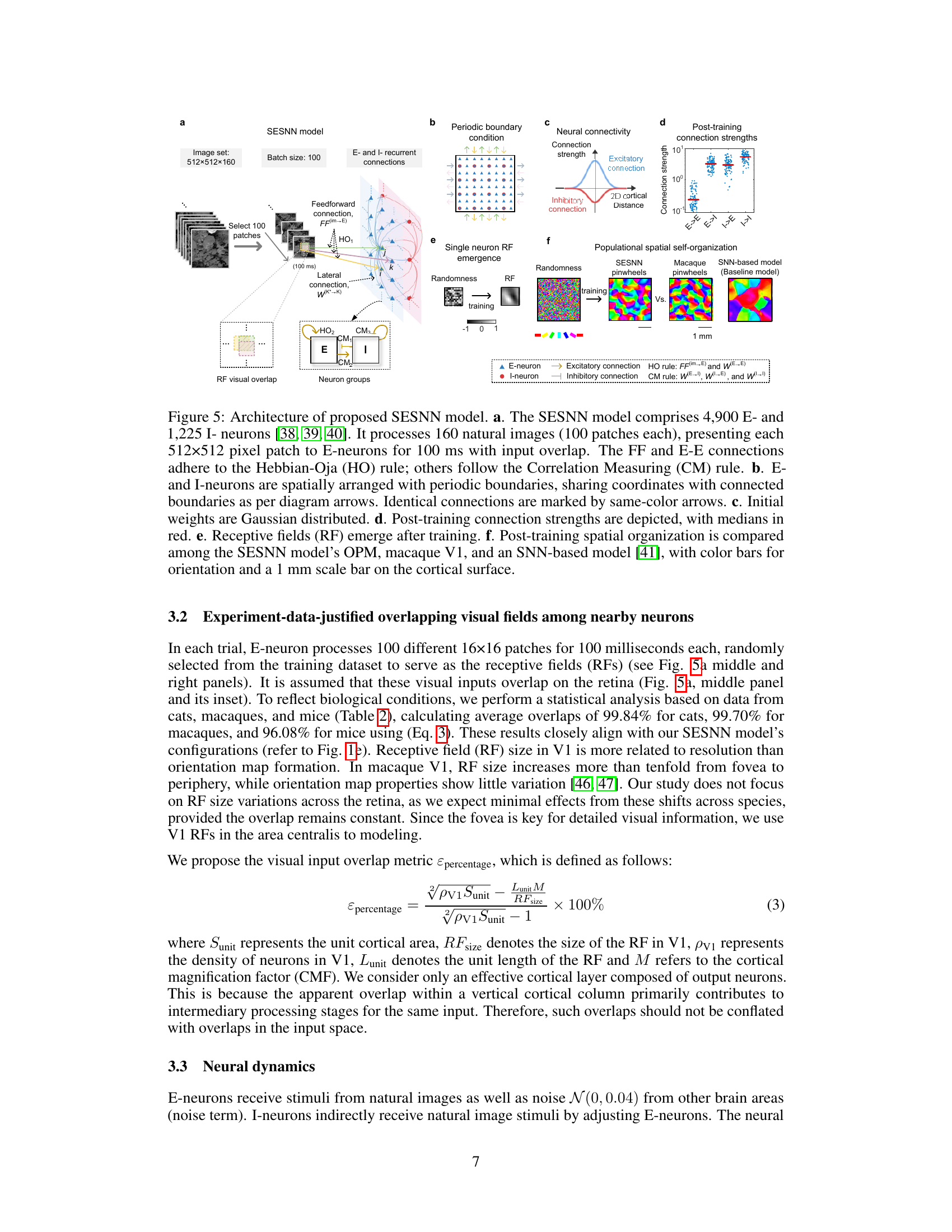

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Self-Evolving Spiking Neural Network (SESNN) model, which is a two-dimensional network of excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons. The figure details the network’s connections (feedforward and recurrent), the learning rules applied (Hebbian-Oja and Correlation Measuring), and the emergence of receptive fields (RFs) and pinwheel structures during training. Panel (f) shows a comparison of the SESNN model’s output with macaque V1 data and a baseline model, highlighting the model’s ability to produce realistic orientation preference maps.

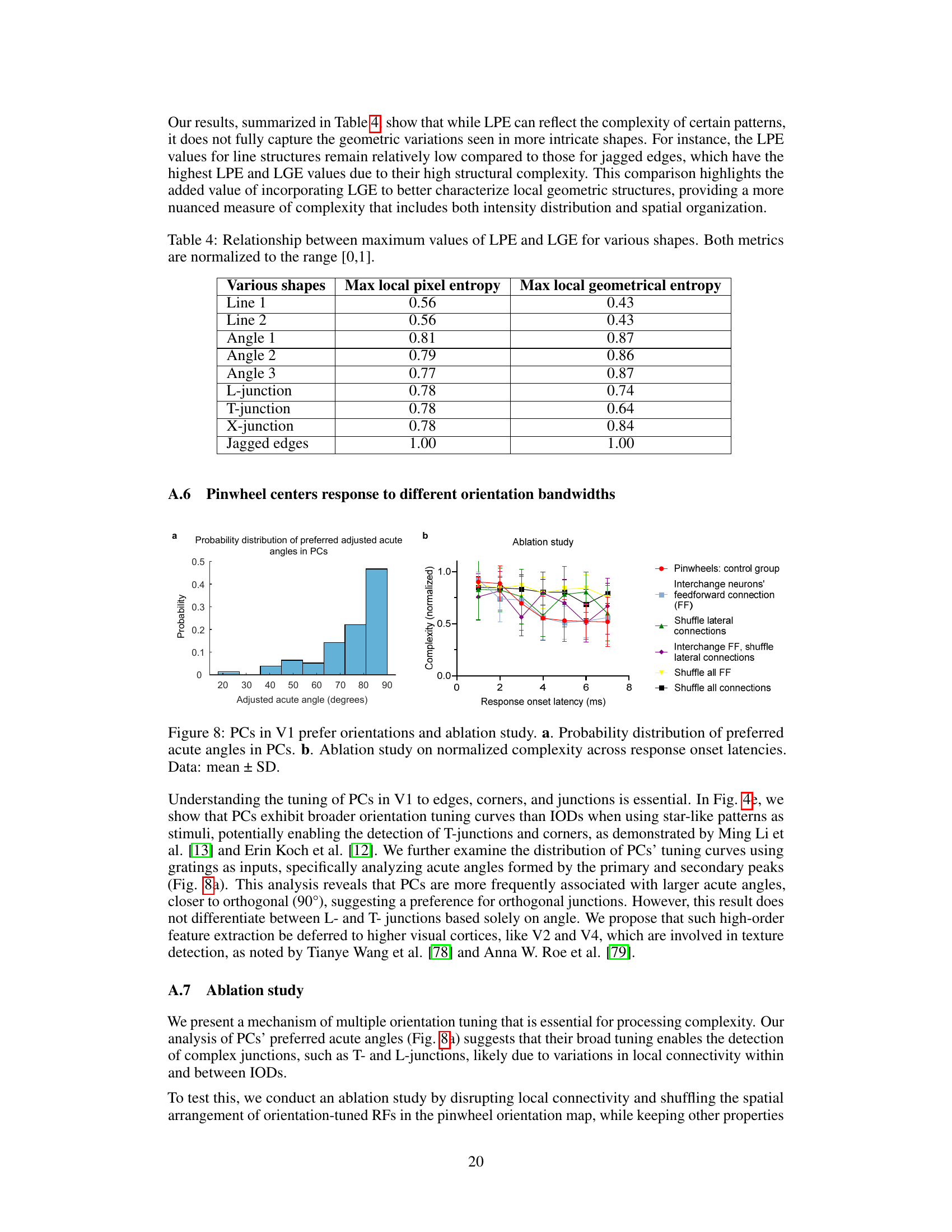

This figure uses a linear classifier based on receptive field density to distinguish between species with salt-and-pepper organizations in their visual cortex and those with pinwheel structures. Panel (a) shows the classification of species, while panel (b) shows how the ratio of V1 neuron number to retina size correlates with the presence of pinwheels, suggesting a threshold ratio for pinwheel formation.

This figure shows how the range of neuronal connections affects the formation and properties of pinwheel structures in the primary visual cortex (V1). Panel (a) illustrates this effect visually. Panels (b), (c), and (d) quantitatively show how changes in the connection range affect the number of pinwheels, the average distance between neighboring pinwheels (NNPD), and the size of hypercolumns, respectively. The results demonstrate a clear relationship between connection range and the organization of orientation columns in V1.

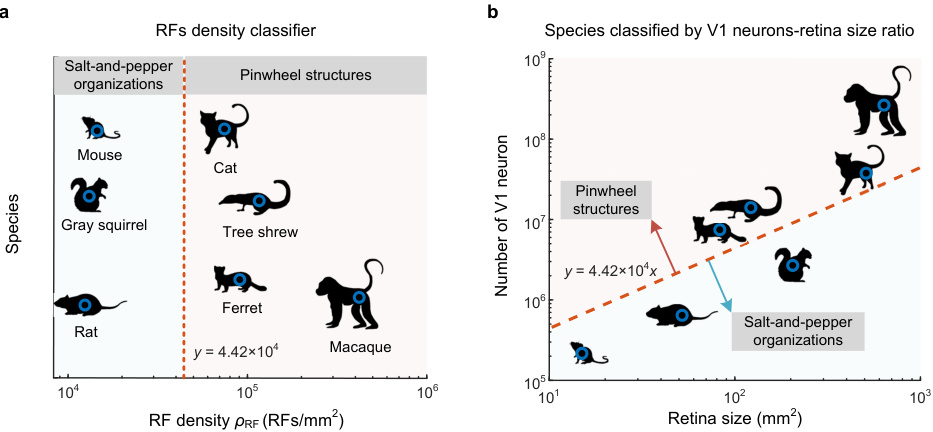

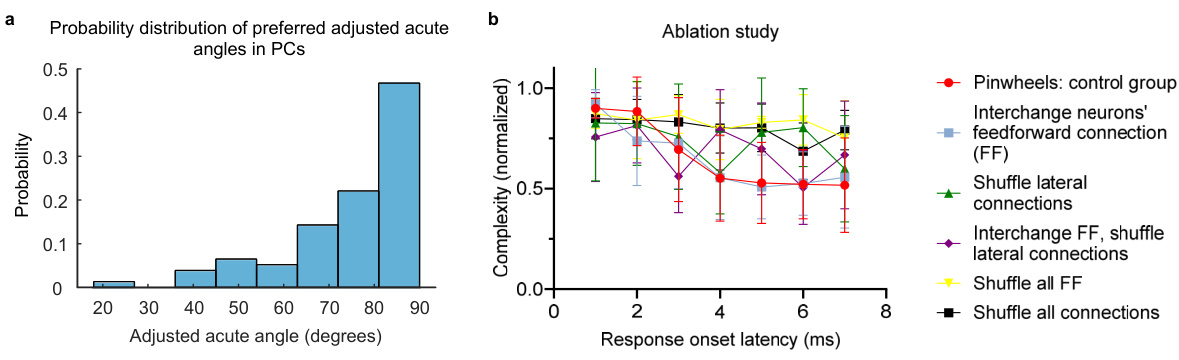

Figure 8 presents the results of two analyses. Panel (a) shows a probability distribution of preferred adjusted acute angles in pinwheel centers (PCs) of the primary visual cortex (V1). The distribution indicates a preference for larger angles closer to 90 degrees, suggesting a bias towards orthogonal orientations or junctions. Panel (b) displays the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of different connectivity manipulations on the normalized complexity of neural responses. Multiple conditions are tested, including shuffling different types of connections (feedforward, lateral, or both), and comparing their response latencies to a control group. The results demonstrate the importance of structured connectivity in maintaining the complex response patterns characteristic of pinwheel structures.

More on tables

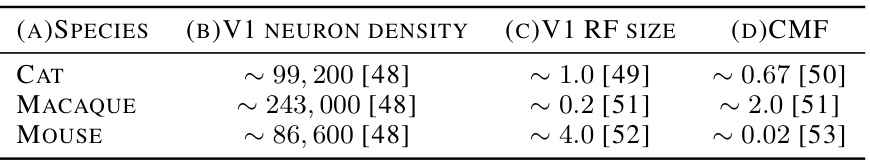

This table compares anatomical data of the retina and primary visual cortex (V1) across three species: cats, macaques, and mice. It shows the neuron density in V1, the size of the receptive field (RF) in the area centralis, and the cortical magnification factor (CMF). These parameters are crucial for understanding the differences in visual processing and the formation of orientation maps in these different species. The data is sourced from various research papers, with citation numbers provided in brackets.

This table presents a comparison of anatomical data for the retina and primary visual cortex (V1) across three different species: macaques, cats, and mice. It shows the mean retinal area (mm²), V1 area (mm²), V1 neuron density (neurons/mm²), and the size of the receptive fields in V1’s area centralis (degrees). It also calculates the density of receptive fields (RFs) per square millimeter in V1. This data is used in the paper to analyze the relationship between visual input overlap, anatomical features, and the emergence of different visual cortical organization patterns (pinwheels vs. salt-and-pepper).

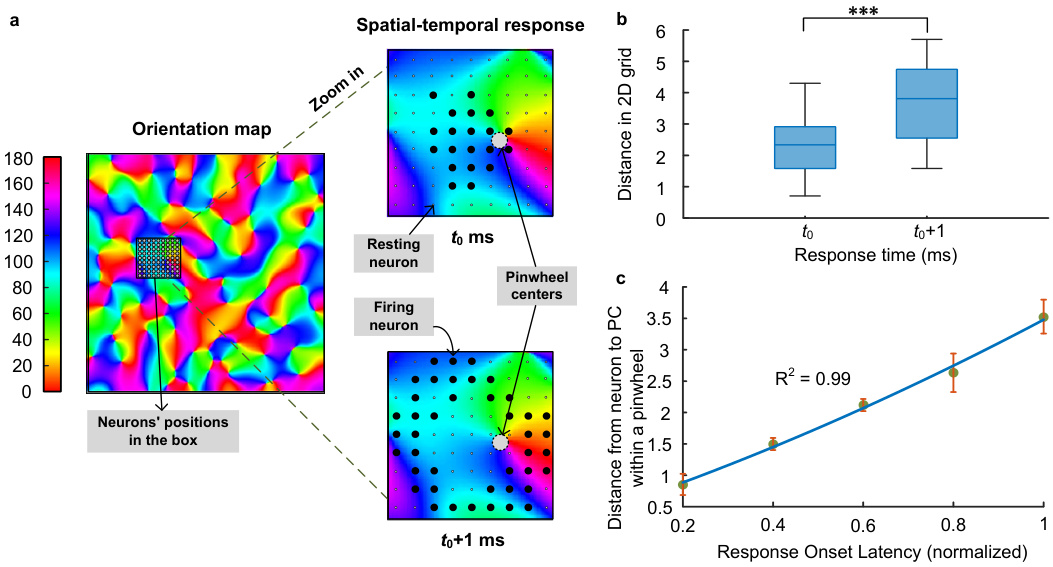

This table compares the maximum values of Local Pixel Entropy (LPE) and Local Geometrical Entropy (LGE) for various shapes, including lines, angles, and different types of junctions (L, T, X). Both metrics are normalized to the range [0,1] for easy comparison. The purpose is to demonstrate that while LPE captures some aspects of complexity, LGE provides a more nuanced and comprehensive measure, especially for intricate shapes.

This table presents comparative anatomical data for the retina and primary visual cortex (V1) across three species: macaque, cat, and mouse. For each species, the table lists the retina size (mm²), V1 size (mm²), V1 neuron density (neurons/mm²), V1 receptive field (RF) size in the area centralis (degrees), and the resulting calculated RF density (RFs/mm²). The RF density is calculated as the product of V1 size and V1 neuron density divided by the retina size. This table provides quantitative information on the anatomical differences between the species, offering context for interpreting differences in the organization of the visual cortex.

Full paper#