↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many LiDAR semantic segmentation methods project point clouds onto 2D images, causing significant information loss, especially for small objects. This loss stems from multiple 3D points mapping to the same 2D location, where only one is retained. This leads to incomplete geometric structures and hinders accurate identification of small objects.

To overcome this, SFCNet introduces a novel spherical frustum structure that preserves all points within a frustum. A hash-based representation ensures efficient storage. The network employs Spherical Frustum Sparse Convolution (SFC) and Frustum Farthest Point Sampling (F2PS) for efficient feature extraction and uniform sampling. Experimental results demonstrate that SFCNet outperforms existing methods on benchmark datasets, significantly improving the segmentation of small objects due to the preservation of complete geometric structures.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical issue of quantized information loss in LiDAR point cloud semantic segmentation, a common problem hindering accurate object recognition, especially for smaller objects. By introducing a novel spherical frustum structure and associated algorithms, SFCNet offers a significant improvement in segmentation accuracy, opening new avenues for research in autonomous driving and robotics.

Visual Insights#

This figure compares conventional spherical projection with the proposed spherical frustum approach. The conventional method projects 3D LiDAR points onto a 2D plane, discarding points that fall on the same grid cell, leading to information loss and inaccurate segmentation, particularly for small objects. In contrast, the spherical frustum preserves all points projected to the same 2D location, preventing information loss and improving segmentation accuracy, as demonstrated by the example of correctly segmenting a person.

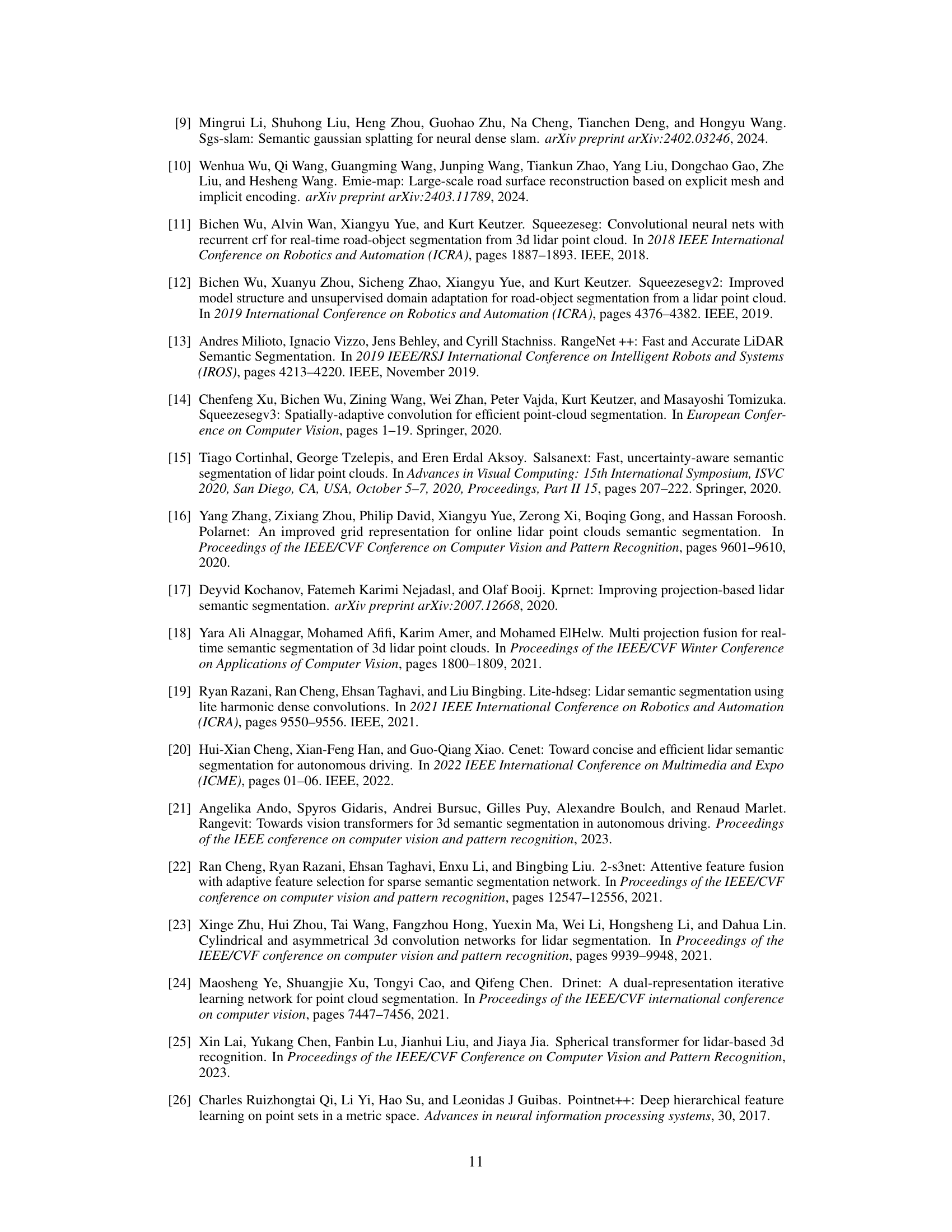

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different semantic segmentation methods on the SemanticKITTI test set. The methods are categorized into three groups: Point-Based, 3D Voxel-Based, and 2D Projection-Based. For each method, the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) is reported for 19 semantic classes. The best performing method in each category is highlighted in bold. This allows for a direct comparison of the performance of various approaches across different methodological categories.

In-depth insights#

SFCNet Architecture#

The SFCNet architecture is a novel approach to LiDAR point cloud semantic segmentation that leverages a spherical frustum structure to avoid the information loss inherent in conventional 2D projection methods. This structure preserves all points projected onto the same 2D grid, which is crucial for accurate segmentation, especially of small objects. The architecture integrates hash-based representation for efficient storage and retrieval of spherical frustums. The core components are the Spherical Frustum Sparse Convolution (SFC), which aggregates point features from neighboring frustums in a memory-efficient way, and Frustum Farthest Point Sampling (F2PS), ensuring uniform sampling of the 3D point cloud. The encoder-decoder structure uses SFC layers and F2PS for feature extraction and downsampling, while employing upsampling and concatenation in the decoder to achieve high-quality semantic segmentation.

Frustum Sampling#

Frustum sampling, in the context of LiDAR point cloud processing, presents a novel approach to downsampling point clouds while preserving crucial geometric information. Unlike traditional methods that might lead to information loss by projecting points onto a 2D grid, frustum sampling leverages a 3D spherical frustum structure. This structure ensures that all points projected onto the same 2D location are retained, preventing the quantization issues that plague other approaches. The key innovation lies in combining this 3D structure with efficient sampling strategies, likely employing techniques like farthest point sampling (FPS), to guarantee uniform downsampling across the entire point cloud, regardless of point density variations. This uniformity is critical for balanced feature aggregation in subsequent processing steps, avoiding biases towards denser regions. The hash-based representation of frustums offers memory efficiency, enabling the storage and retrieval of frustum data without significant overhead. In essence, frustum sampling provides a more complete and accurate representation of the point cloud for downstream tasks such as semantic segmentation, enhancing the performance particularly for smaller objects which often get lost in traditional downsampling processes.

Quantized Loss#

The concept of “Quantized Loss” in LiDAR point cloud processing highlights a critical challenge in converting 3D point cloud data into a 2D representation for processing with 2D convolutional neural networks. The loss arises from the inherent discretization of the 3D point cloud when projecting onto a 2D grid, where multiple points might map to the same pixel. This leads to information loss, especially concerning small objects whose points might be completely dropped during projection. This loss is not simply about data reduction, but rather a significant distortion of the geometric structure of the point cloud, affecting the accuracy of semantic segmentation, particularly in identifying and classifying small objects that may have only a few points in the raw data. The paper addresses this by proposing an alternative representation—a spherical frustum—that avoids data quantization, preserving the complete geometric structure, and thereby reducing this quantized loss and enabling more accurate segmentation results.

Small Object Seg#

The heading ‘Small Object Seg’ likely refers to a section discussing the challenges and proposed solutions for semantic segmentation of small objects within a larger point cloud. This is a particularly difficult task because small objects often contain few points, leading to inadequate feature representation and increased vulnerability to noise and occlusion. The paper likely explores methods to improve detection and classification of these small objects, potentially through techniques like contextual information aggregation, upsampling or super-resolution strategies, or specialized convolutional or attention mechanisms. Success in this area is crucial for applications demanding high-precision semantic understanding, such as autonomous driving or robotics, where correctly identifying small but critical elements (pedestrians, traffic signs, etc.) is paramount for safety and effective navigation. The discussion likely includes quantitative results showcasing improvements in segmentation accuracy specifically for small objects, compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

Future Works#

The paper’s conclusion mentions several promising avenues for future research. Expanding the receptive field of the network is crucial, potentially through incorporating vision transformers or similar architectures known for their broad contextual understanding. Addressing the limitations of relying solely on the nearest points within spherical frustums for convolution is another key area. This could involve exploring alternative aggregation strategies that better capture the local geometric structure. Investigating the performance on weakly-supervised or multi-modal settings presents a significant challenge and opportunity. Finally, adapting the spherical frustum structure to different LiDAR point cloud tasks, such as registration and scene flow estimation, could unlock new possibilities and applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

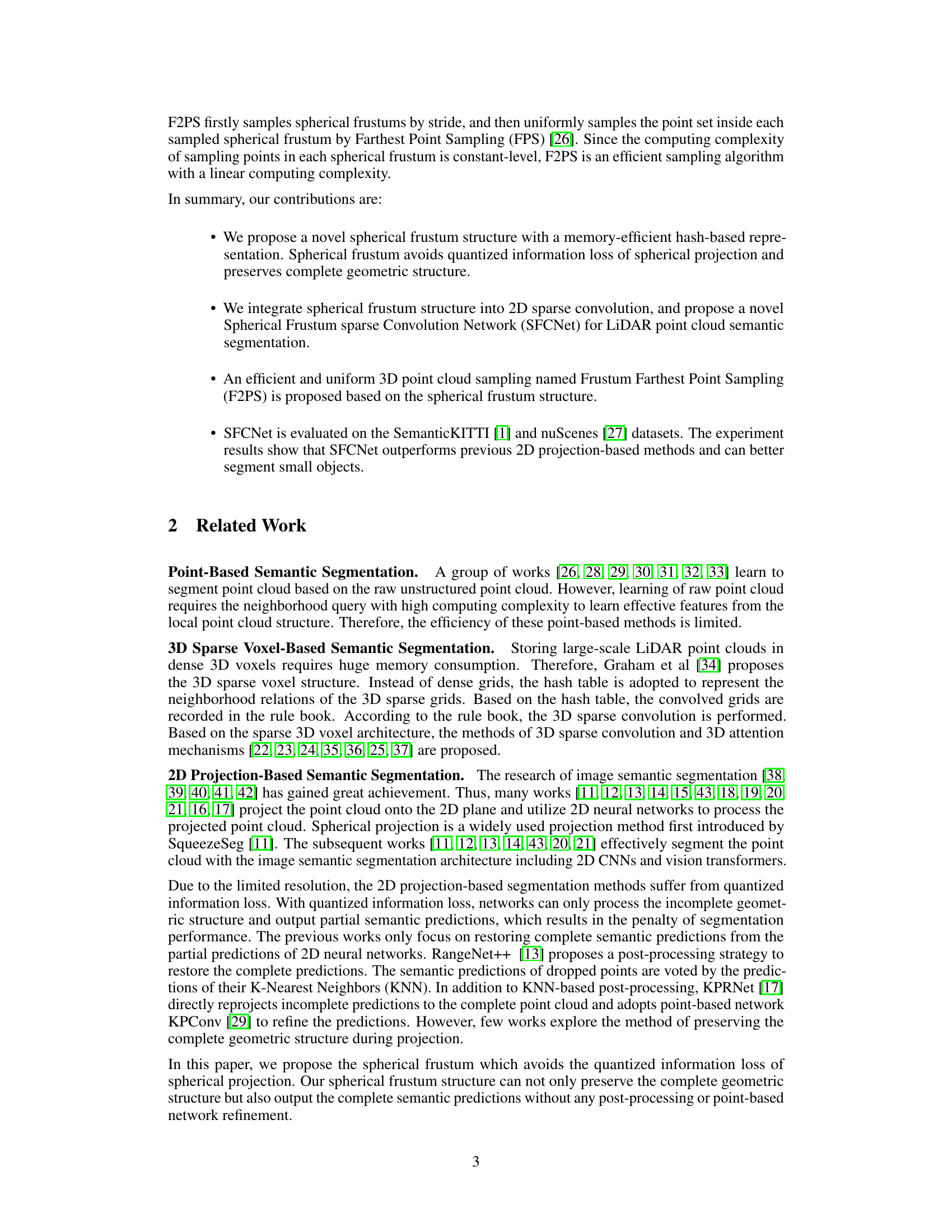

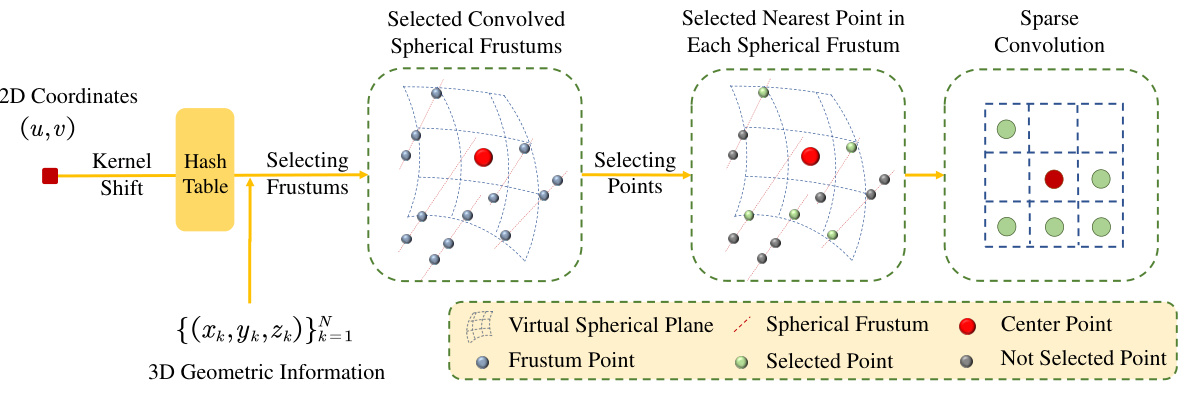

This figure illustrates the process of Spherical Frustum Sparse Convolution (SFC). It starts by selecting spherical frustums using a hash table based on a kernel shift from a central 2D coordinate (u,v). Then, the closest point within each selected spherical frustum is identified using 3D geometric information. Finally, a sparse convolution is performed on the features of these selected nearest points.

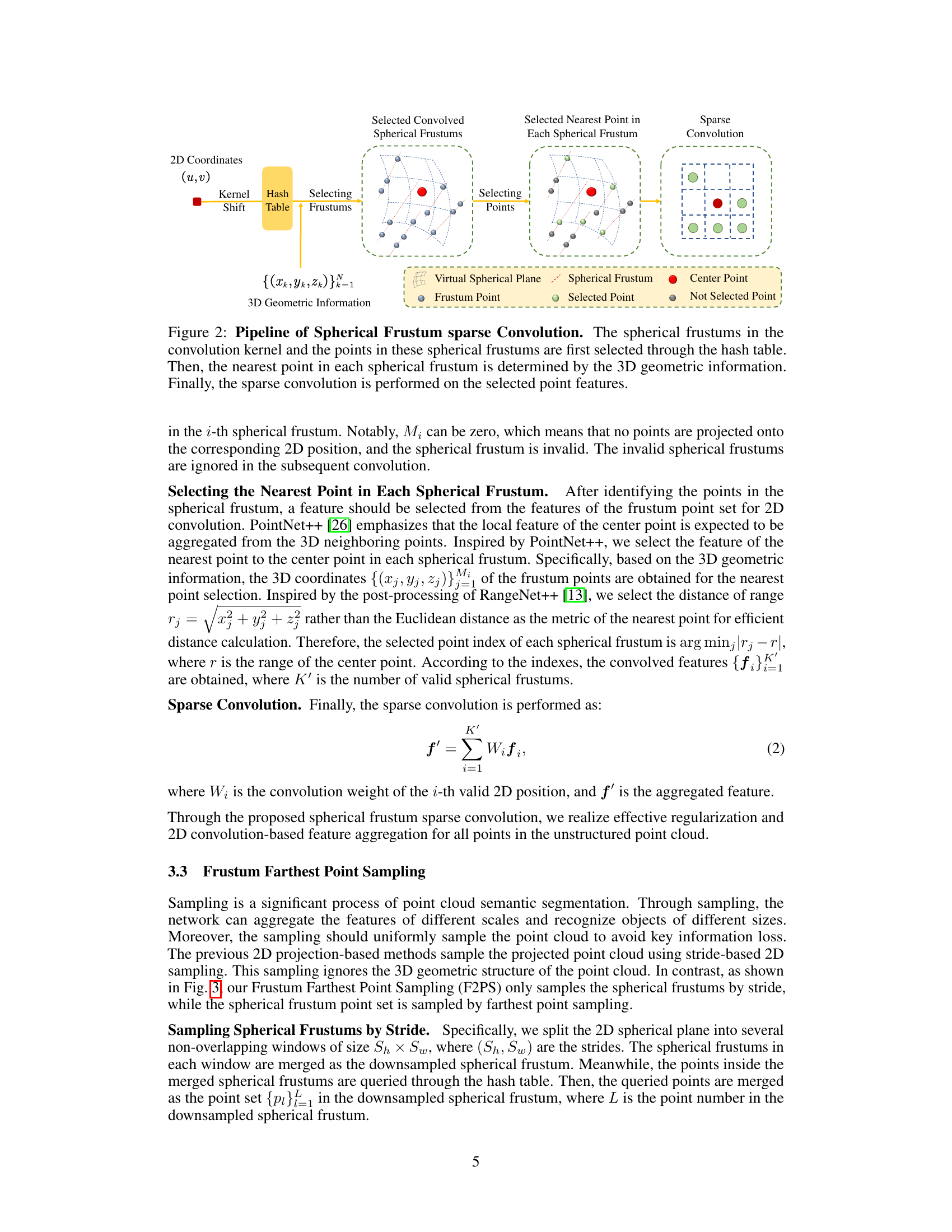

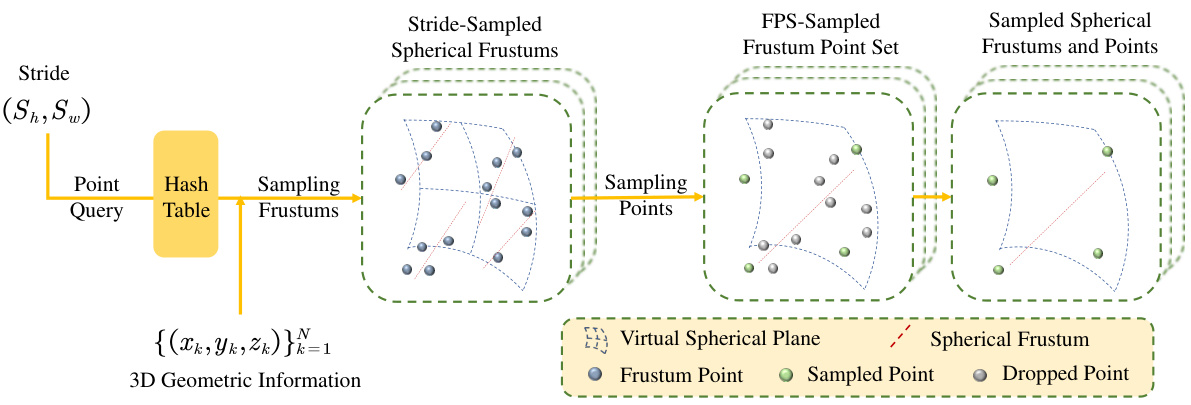

This figure illustrates the Frustum Farthest Point Sampling (F2PS) method. It starts by dividing the 2D spherical plane into windows using strides. Spherical frustums within each window are merged to create downsampled frustums. The hash table is then used to query the points within these downsampled frustums. Farthest Point Sampling is then applied to uniformly sample the points within each downsampled frustum. The result is a uniformly sampled point cloud and a set of uniformly sampled spherical frustums, suitable for use in the network.

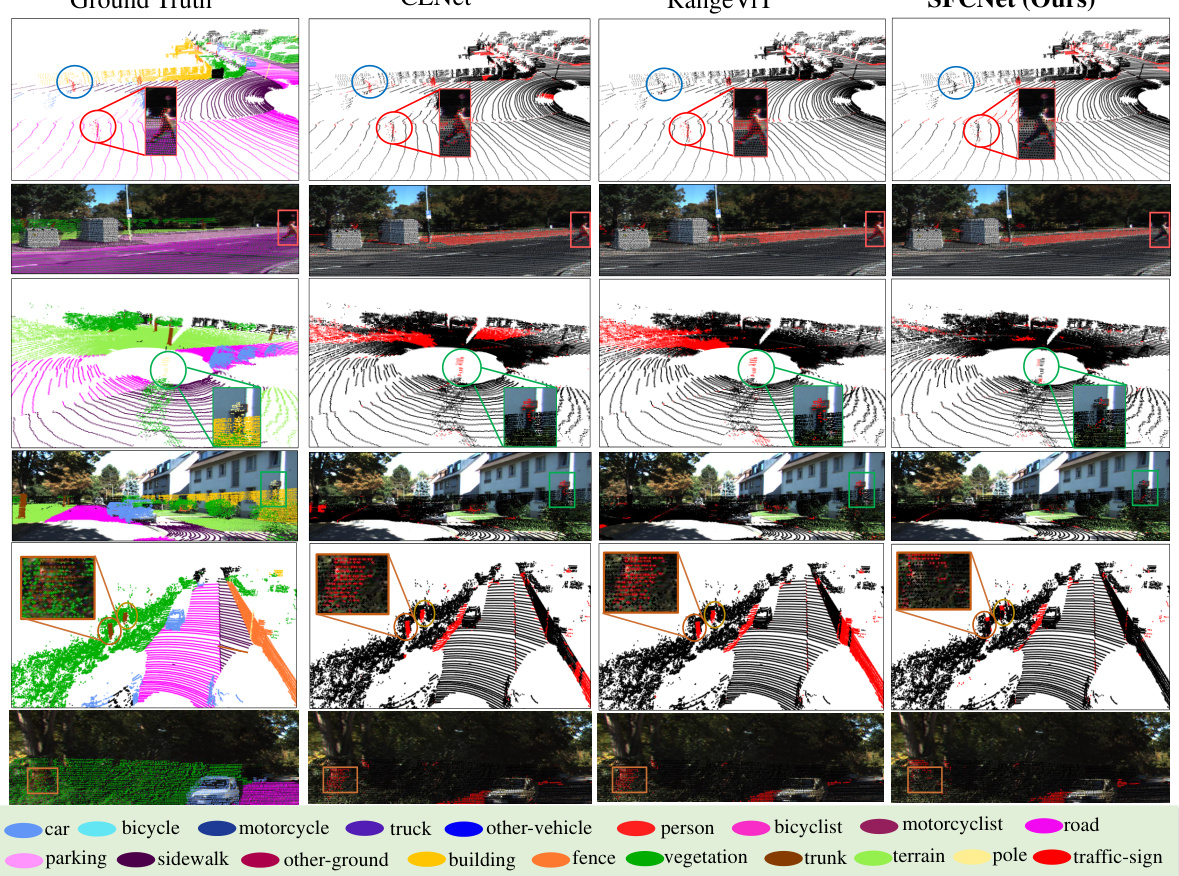

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of semantic segmentation results on the SemanticKITTI validation set between three methods: CENet, RangeViT, and SFCNet (the authors’ method). Each row displays a scene with ground truth, then error maps (falsely classified points in red) for each method, highlighting the improvements of SFCNet in object classification accuracy, especially for small objects such as people and poles. Corresponding RGB images provide visual context.

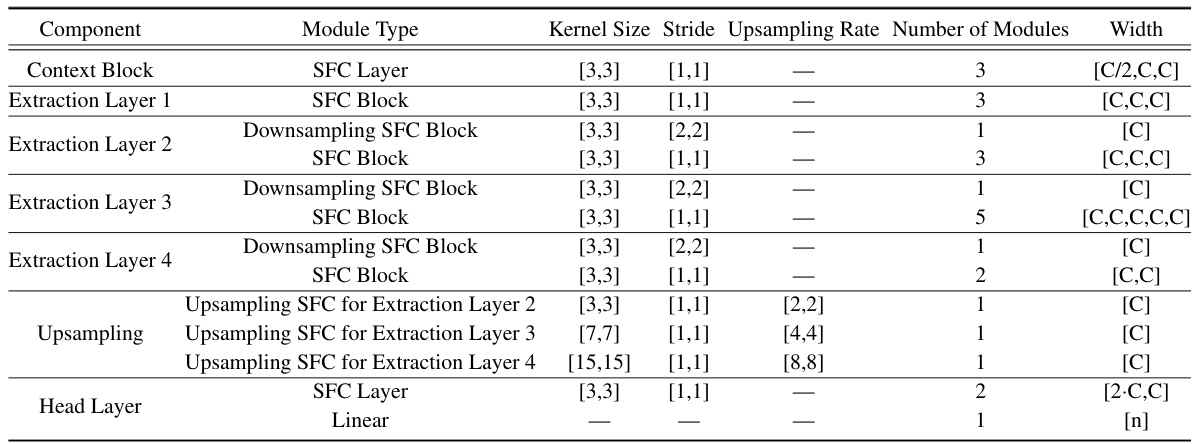

This figure shows the detailed architecture of SFCNet, a deep learning model for LiDAR point cloud semantic segmentation. It breaks down the model into its core components: a context block, extraction layers, downsampling and upsampling SFC blocks, and a head layer. Each component is described with its constituent sub-modules (SFC Layer, SFC Block, and Downsampling SFC Block), illustrating the flow of data and feature processing throughout the network.

This figure illustrates the Frustum Farthest Point Sampling (F2PS) process. First, the 2D spherical plane is divided into stride windows. Spherical frustums within each window are merged into downsampled spherical frustums. Points within these are then queried using a hash table. Finally, Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) selects a uniform subset of these points, resulting in a uniformly sampled point cloud.

This figure compares the proposed spherical frustum approach with the conventional spherical projection method. The conventional method drops points that project to the same 2D grid, leading to information loss, especially for small objects like the person shown in the example. The spherical frustum method, however, preserves all points, preventing information loss and improving segmentation accuracy.

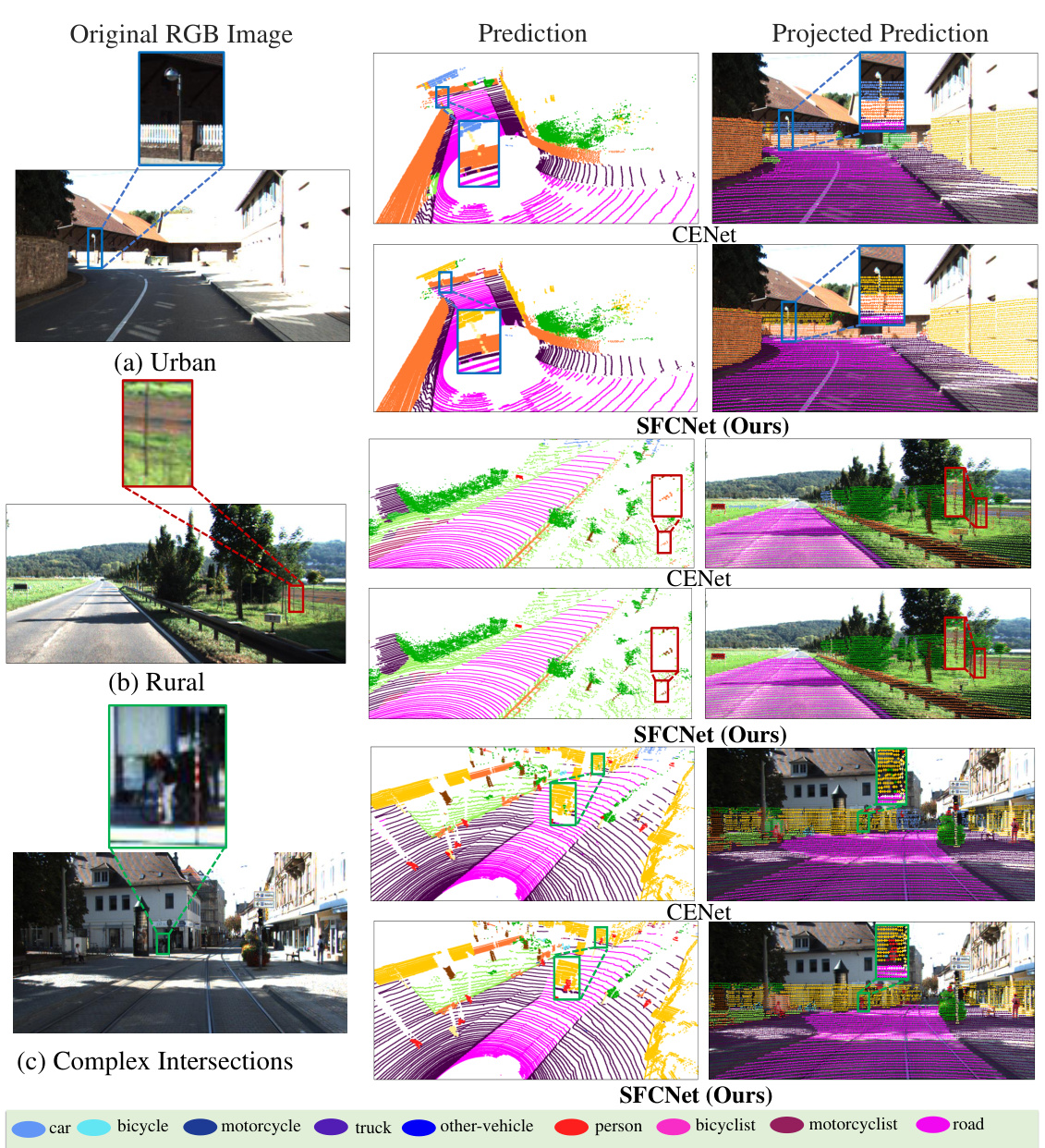

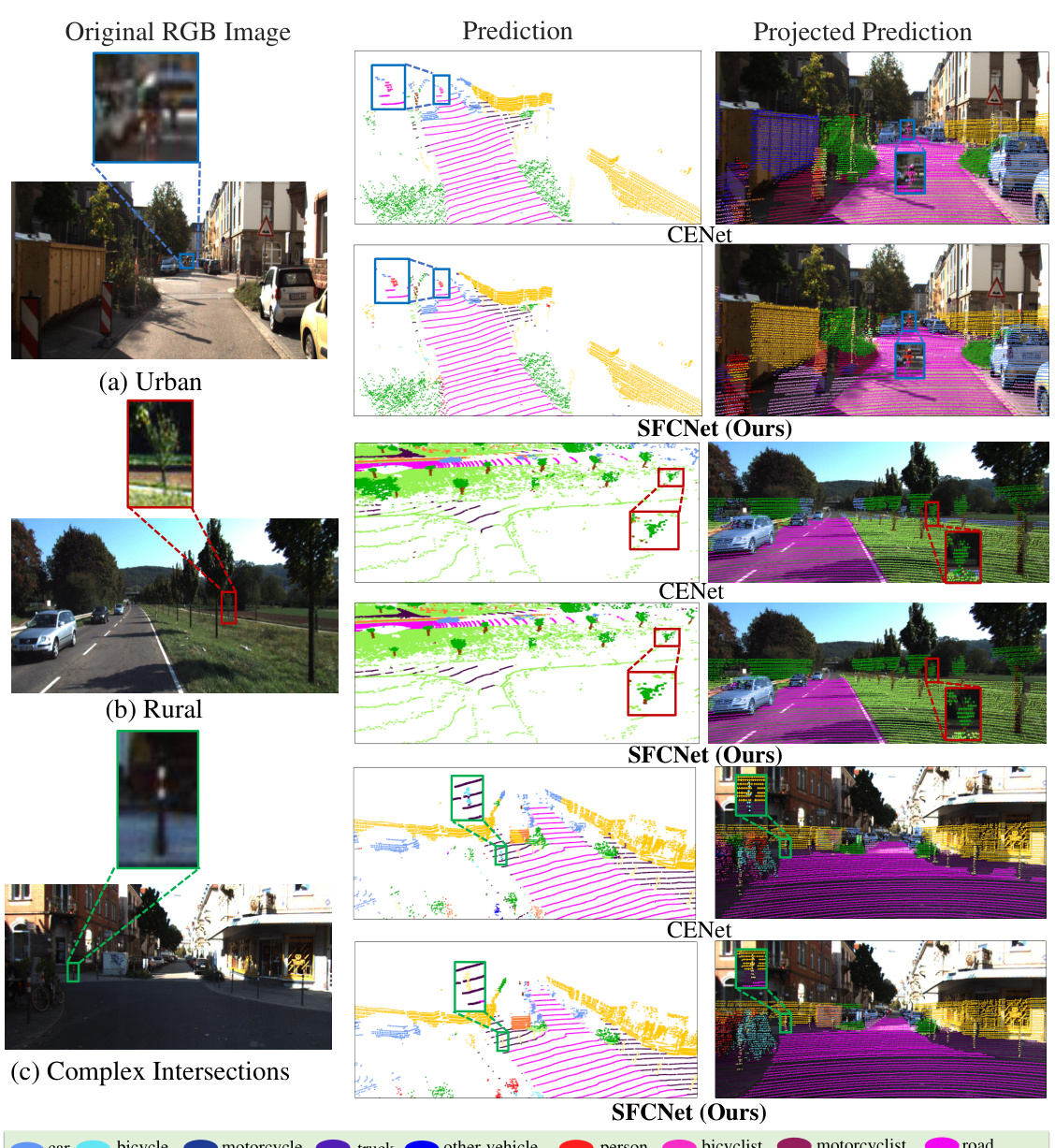

This figure compares the qualitative results of SFCNet and CENet on the SemanticKITTI test set. It shows three example scenes (urban, rural, complex intersection) and visualizes the differences between the ground truth, CENet’s predictions, and SFCNet’s predictions. The color coding for semantic classes is provided, and zoomed-in views highlight the improved accuracy of SFCNet, particularly for small objects.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of semantic segmentation results between SFCNet and CENet on the SemanticKITTI test set for three different scene types: urban, rural, and complex intersections. The results demonstrate SFCNet’s superior performance in accurately segmenting objects, especially small objects, by preserving complete geometric information and avoiding information loss.

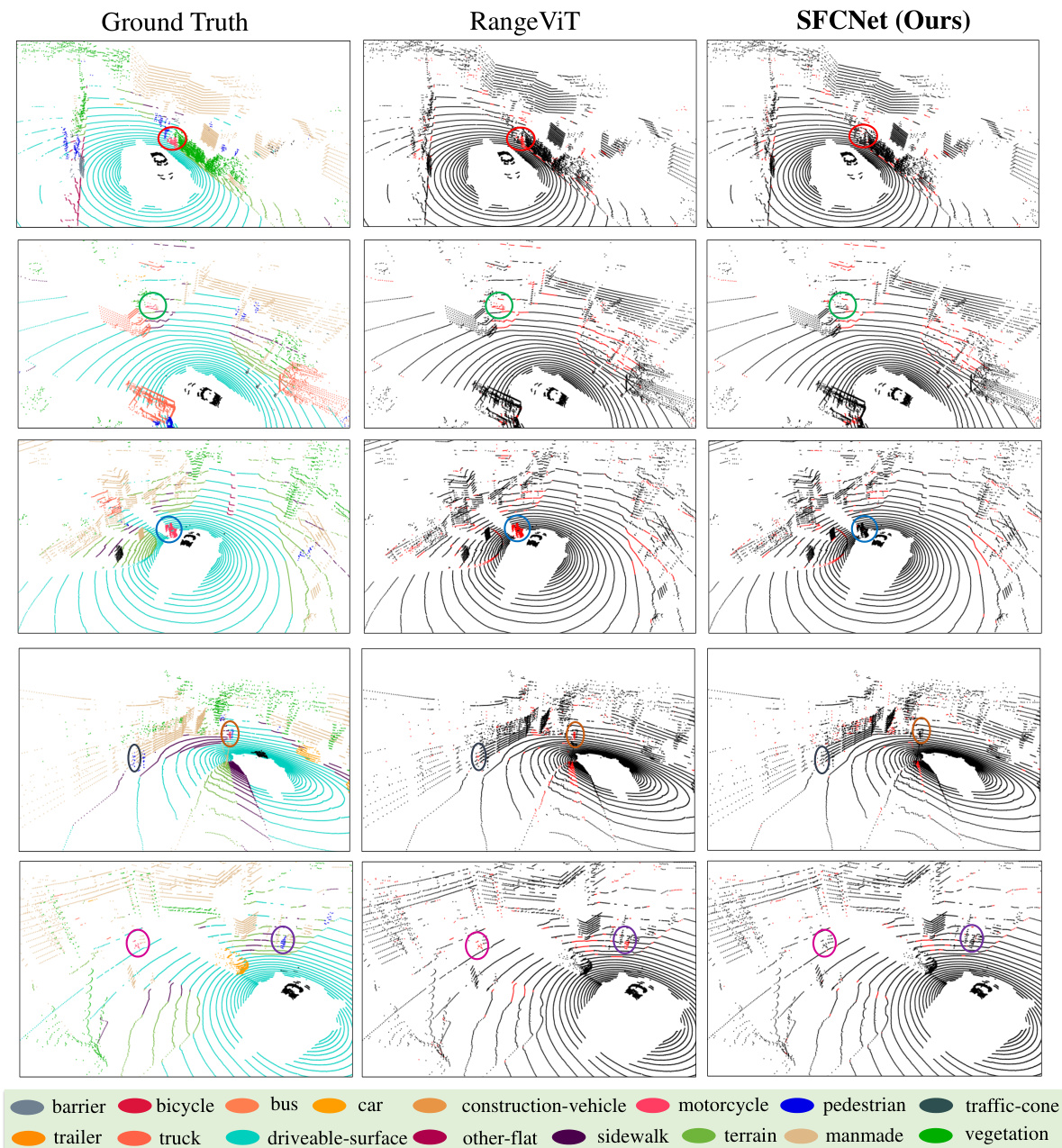

This figure compares the qualitative results of semantic segmentation on the nuScenes validation set between SFCNet and RangeViT. It shows three example scenes, displaying ground truth, RangeViT’s output, and SFCNet’s output for each. The color-coded legend indicates semantic classes. Red highlights incorrect segmentations. The figure demonstrates SFCNet’s improved accuracy and detail, particularly in segmenting smaller objects.

More on tables

This table presents the quantitative results of semantic segmentation on the nuScenes validation set. The results are broken down by category (barrier, bicycle, bus, car, construction, motorcycle, pedestrian, traffic cone, trailer, truck, driveable surface, other flat, sidewalk, terrain, manmade, vegetation) and show the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) achieved by different methods. The methods are categorized into Point-Based, 3D Voxel Based, and 2D Projection Based approaches. Bold numbers indicate the best performance within each method category.

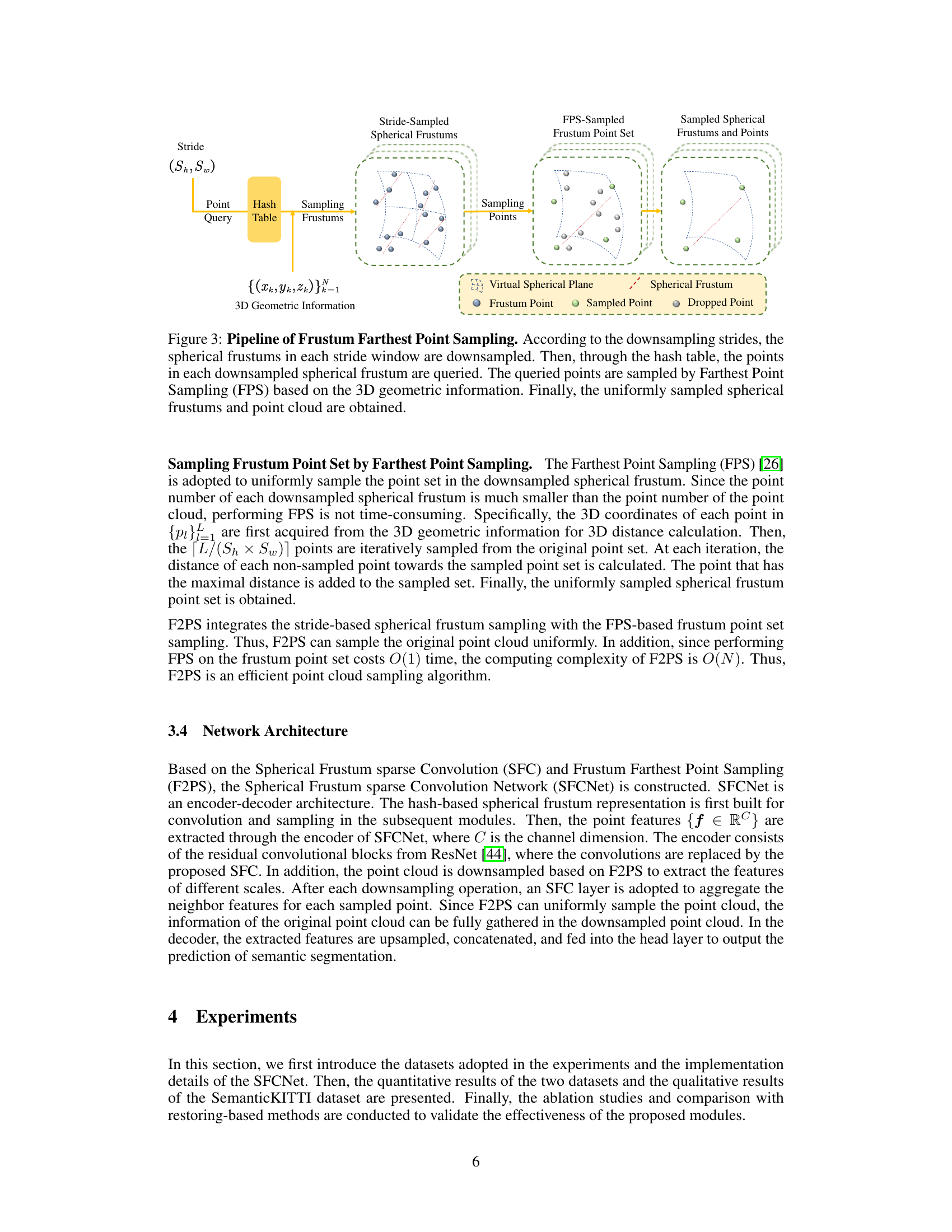

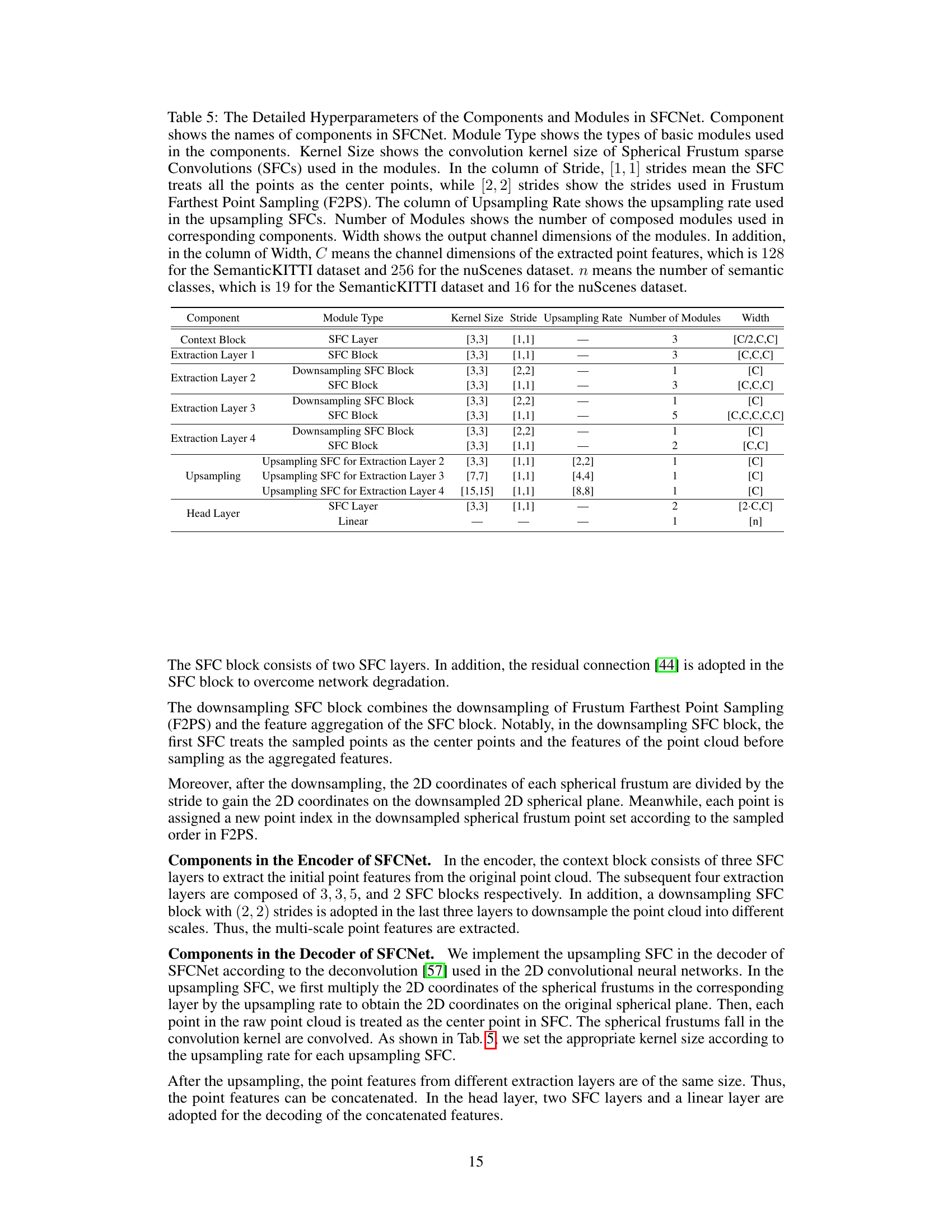

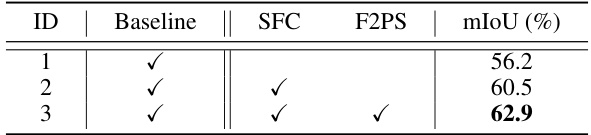

This table presents the ablation study results performed on the SemanticKITTI validation set to analyze the effect of each proposed module in SFCNet. The baseline model uses conventional spherical projection and stride-based sampling. The table shows the mIoU achieved with different combinations of modules: only baseline, with SFC (Spherical Frustum Sparse Convolution), with F2PS (Frustum Farthest Point Sampling), and with both SFC and F2PS. The results demonstrate the contribution of each module to the overall performance improvement.

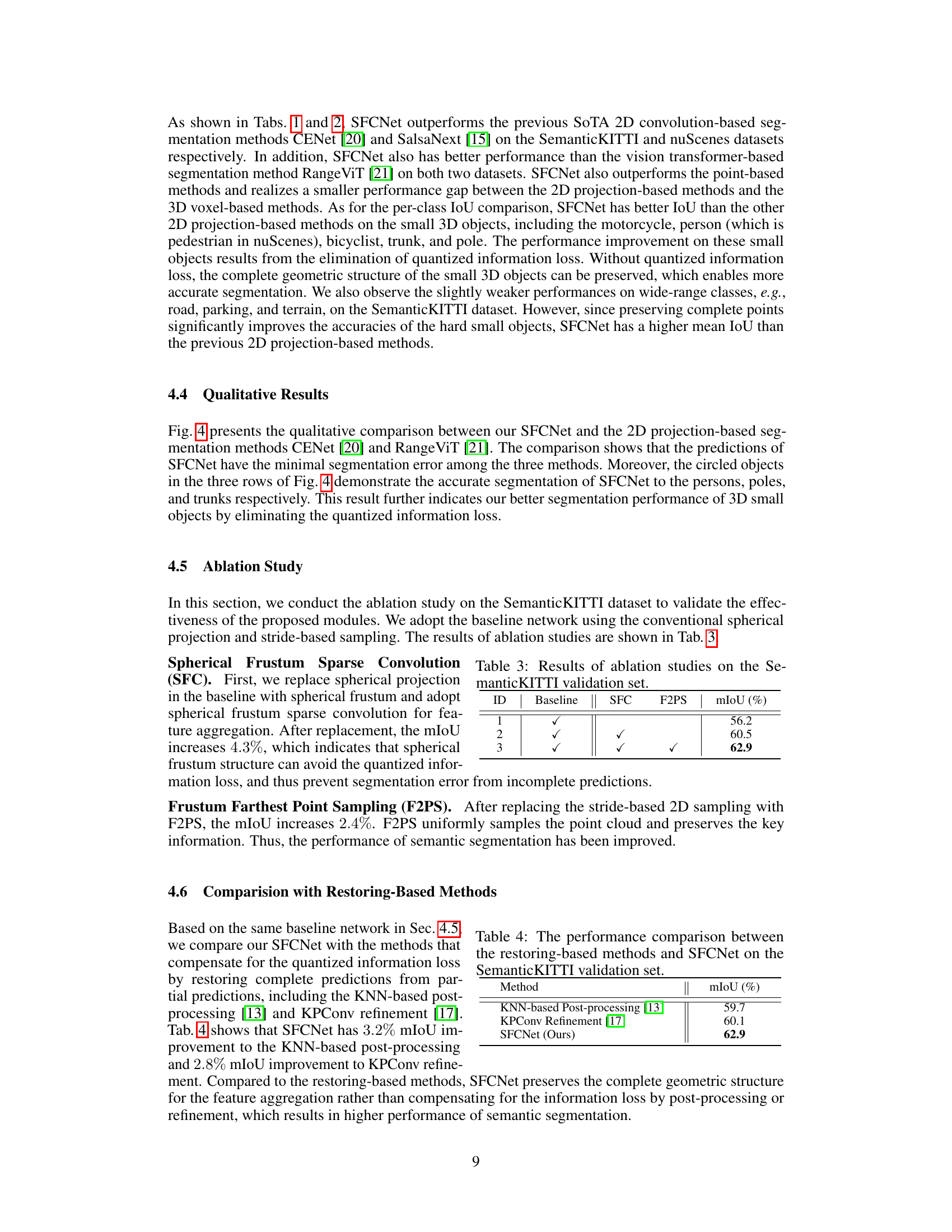

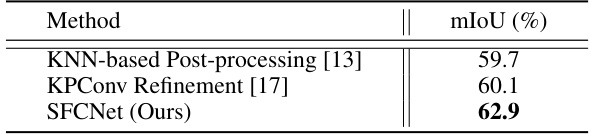

This table compares the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores achieved by SFCNet and two other methods that aim to restore complete semantic predictions from partial ones (KNN-based Post-processing and KPConv Refinement) on the SemanticKITTI validation set. It highlights SFCNet’s superior performance by directly preserving the complete geometric structure during the projection process, avoiding the need for post-processing restoration steps.

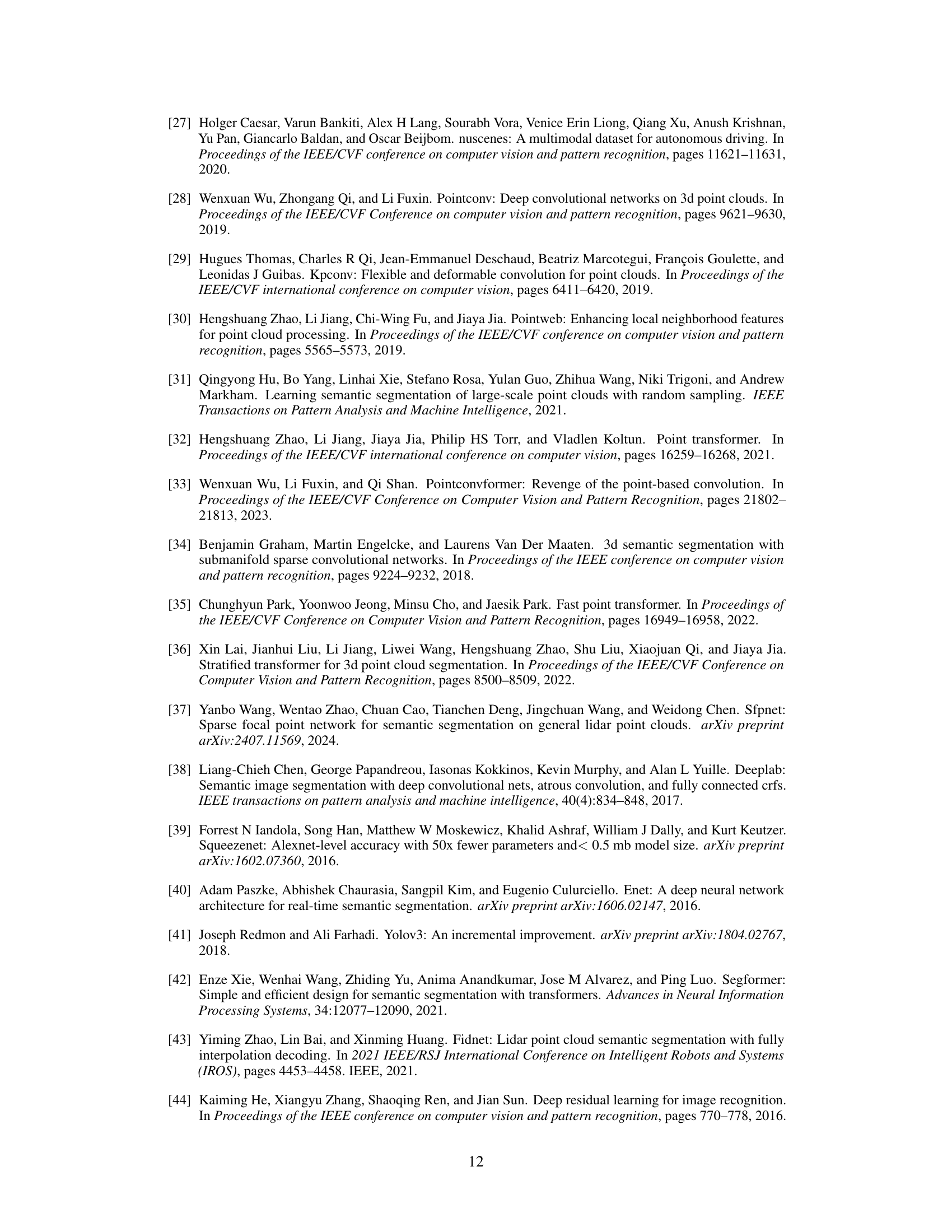

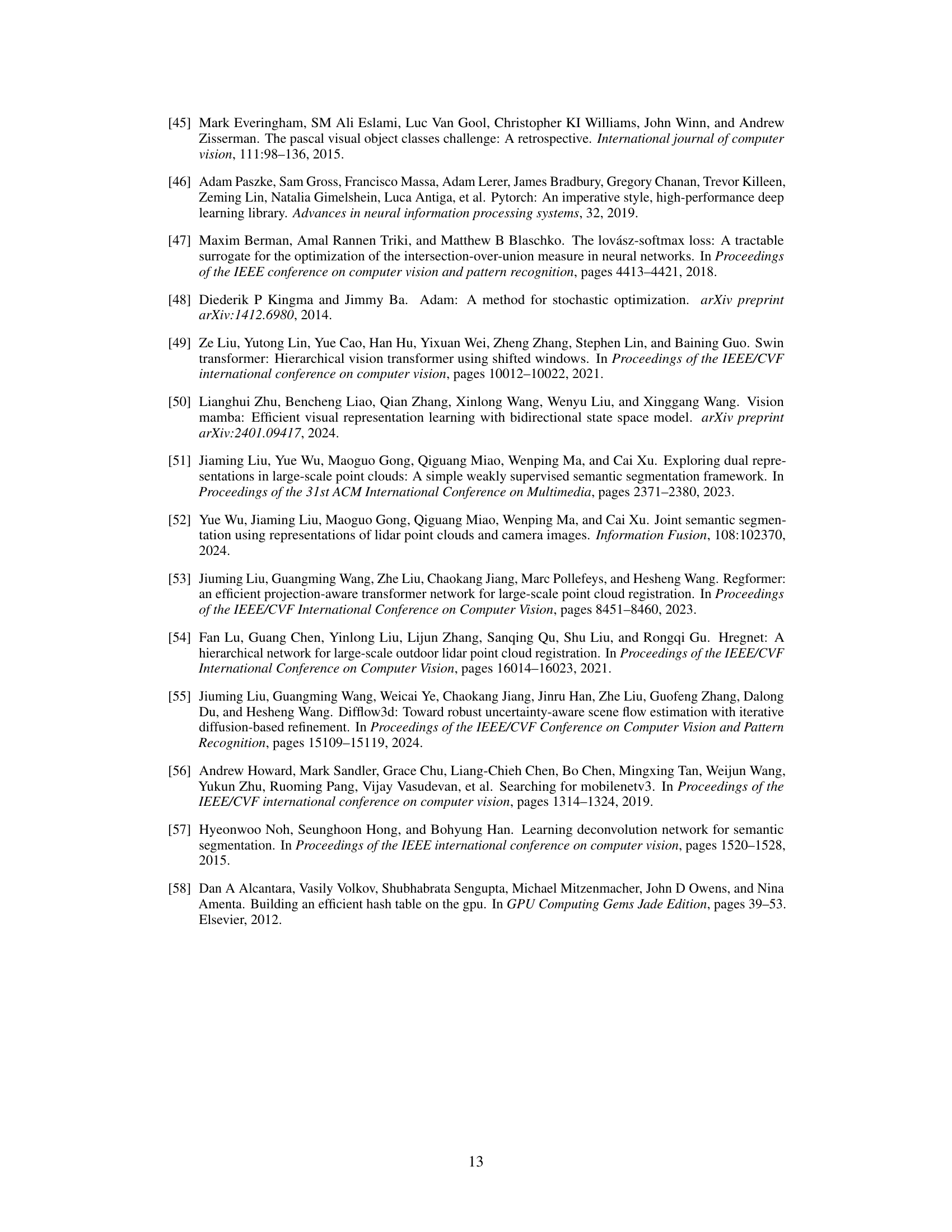

This table details the hyperparameters used in the different components and modules of the SFCNet architecture. It specifies kernel sizes, strides, upsampling rates, the number of modules, and output channel dimensions for each component, differentiating between the SemanticKITTI and nuScenes datasets.

This table shows the mean and standard deviation of the input features (x, y, z coordinates, range, and intensity) for each data category in the SemanticKITTI dataset. These statistics are used for data normalization during the training process of the SFCNet model. The normalization involves subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each feature to ensure that the features have zero mean and unit variance.

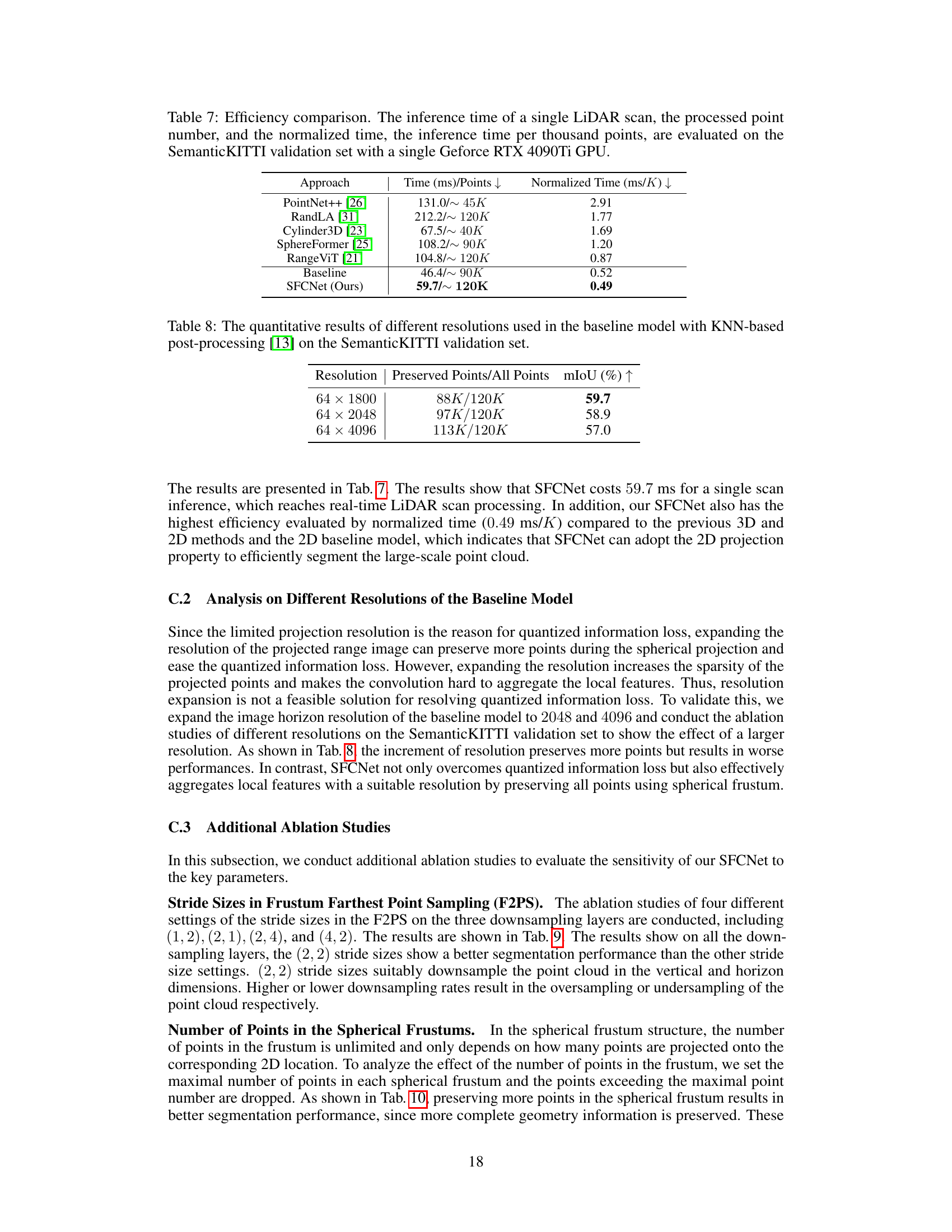

This table compares the inference time and efficiency of different semantic segmentation methods on the SemanticKITTI dataset. The inference time is measured for a single LiDAR scan, and the normalized time represents the inference time per 1000 points. The results show the efficiency of SFCNet compared to other methods.

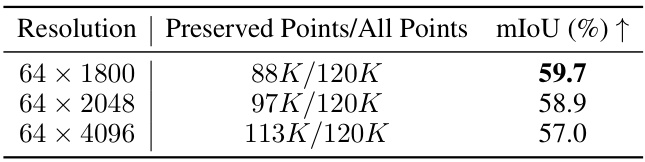

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the baseline model (using conventional spherical projection and stride-based sampling) with different resolutions of the projected range image (64 × 1800, 64 × 2048, 64 × 4096). The results show the number of points preserved at each resolution, and the corresponding mIoU on the SemanticKITTI validation set. The study aims to investigate the effect of resolution on the model’s performance, particularly in relation to information loss caused by dropping points during the projection.

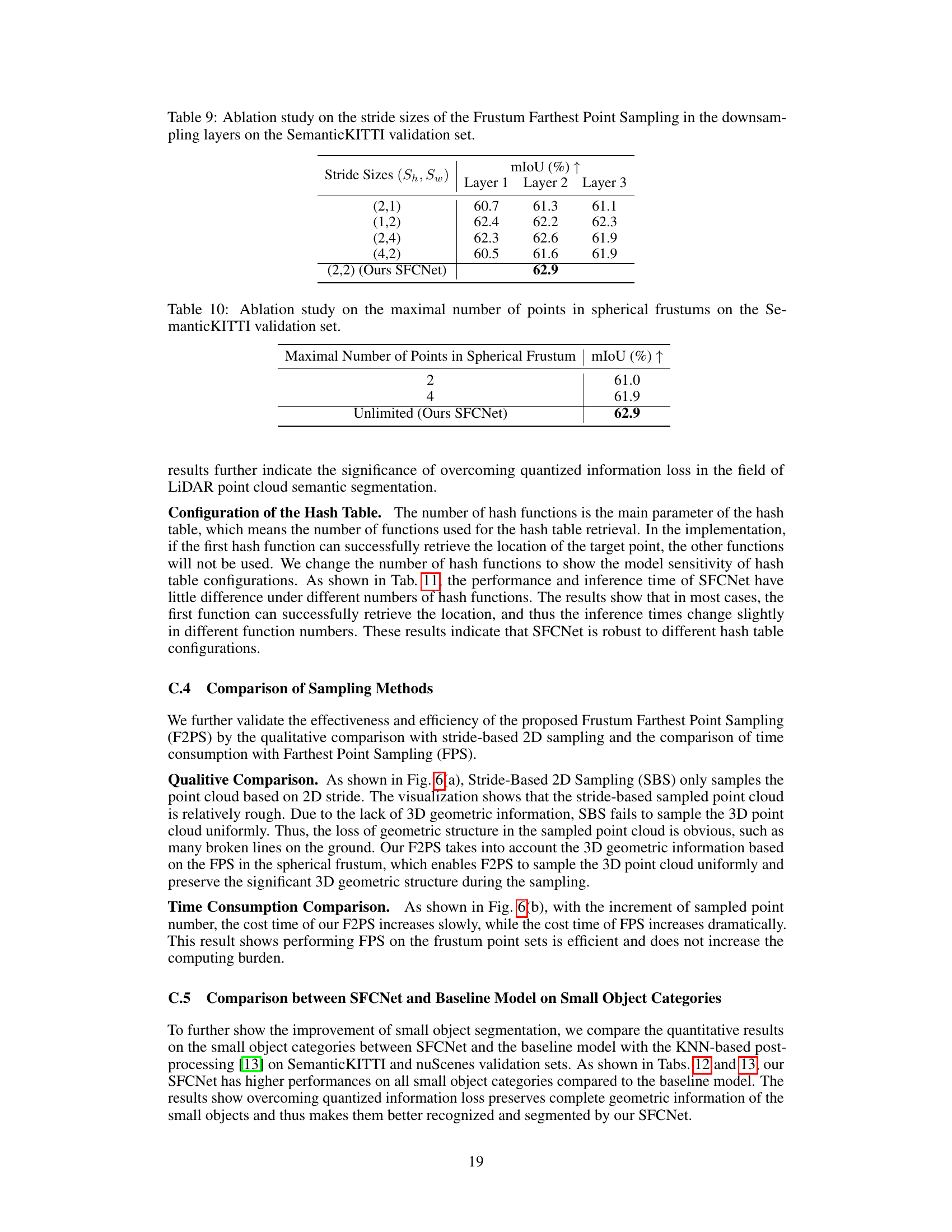

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the SemanticKITTI validation set to assess the impact of different stride sizes used in the Frustum Farthest Point Sampling (F2PS) method on the performance of the model. The study varied the stride sizes in the horizontal and vertical directions during downsampling in three layers of the network. The results show that a stride size of (2,2) yields the best performance, suggesting a balance between downsampling rate and information preservation is crucial for optimal results.

This table shows the results of an ablation study conducted on the SemanticKITTI validation set to analyze the impact of the maximum number of points allowed within each spherical frustum on the model’s performance. The model’s mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) is evaluated for three scenarios: allowing a maximum of 2 points, 4 points, and an unlimited number of points per frustum. The results demonstrate how increasing the maximum number of points improves performance. The unlimited point scenario represents the full SFCNet model.

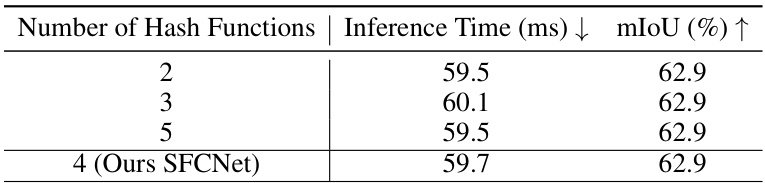

This table presents the ablation study on the number of hash functions used in the hash table for the spherical frustum structure. It shows that the performance (mIoU) remains relatively consistent across different numbers of hash functions, suggesting that the model is robust to this hyperparameter. The slight variations in inference time are likely due to minor differences in the hash table lookup process.

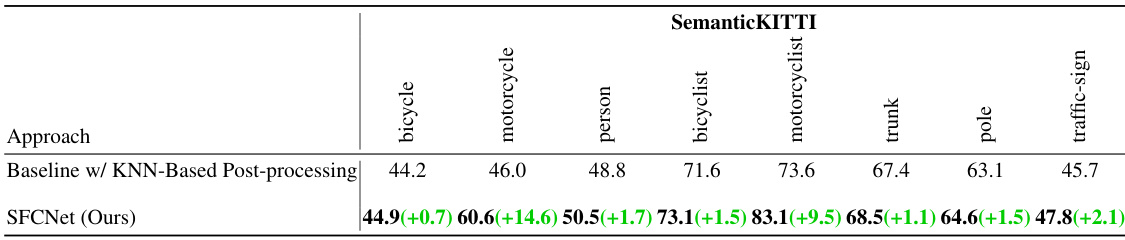

This table presents a quantitative comparison of semantic segmentation performance between the baseline model (with KNN-based post-processing) and the proposed SFCNet. The comparison focuses specifically on small object categories within the SemanticKITTI validation set. The table shows the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) for each small object category and highlights the performance improvement achieved by SFCNet compared to the baseline. Higher mIoU values indicate better segmentation accuracy.

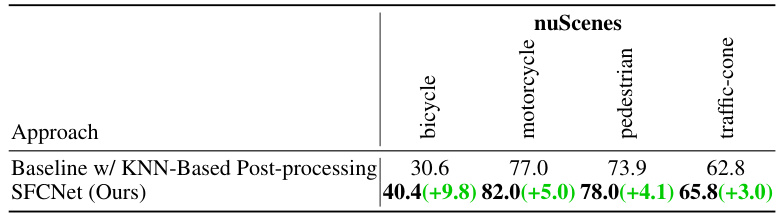

This table compares the performance of the baseline model with KNN-based post-processing and the proposed SFCNet on the nuScenes validation dataset. The comparison focuses specifically on four small object categories: bicycle, motorcycle, pedestrian, and traffic-cone. The mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) scores are provided for each category and method. Green numbers indicate the improvement achieved by SFCNet over the baseline approach.

Full paper#