↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Graph representation learning (GRL) is essential for extracting insights from complex network data but raises serious privacy concerns because sensitive information can be easily inferred from the generated representations. Previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of similarity-based attacks in reconstructing sensitive edges, but a comprehensive theoretical understanding has been lacking. This has led to concerns about the safety of deploying GRL models in real-world settings where privacy is a concern.

This research addresses the aforementioned issues by providing a principled analysis of the success and failure modes of similarity-based edge reconstruction attacks (SERA). The authors provide a non-asymptotic analysis of SERA’s capacity to reconstruct edges and validate their findings through experiments on both synthetic and real-world graphs. They show that SERA is highly effective against sparse graphs but less so against dense graphs. Furthermore, they show how noisy aggregation (NAG) can mitigate the effectiveness of SERA, providing an effective approach for balancing privacy and utility in GRL. The combination of theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation makes this a significant contribution to the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in graph representation learning and security. It provides a rigorous theoretical framework for analyzing privacy vulnerabilities, introduces a novel defense mechanism, and highlights the trade-off between privacy and utility. This work will shape future research in developing privacy-preserving graph neural network models and secure graph analytics methods.

Visual Insights#

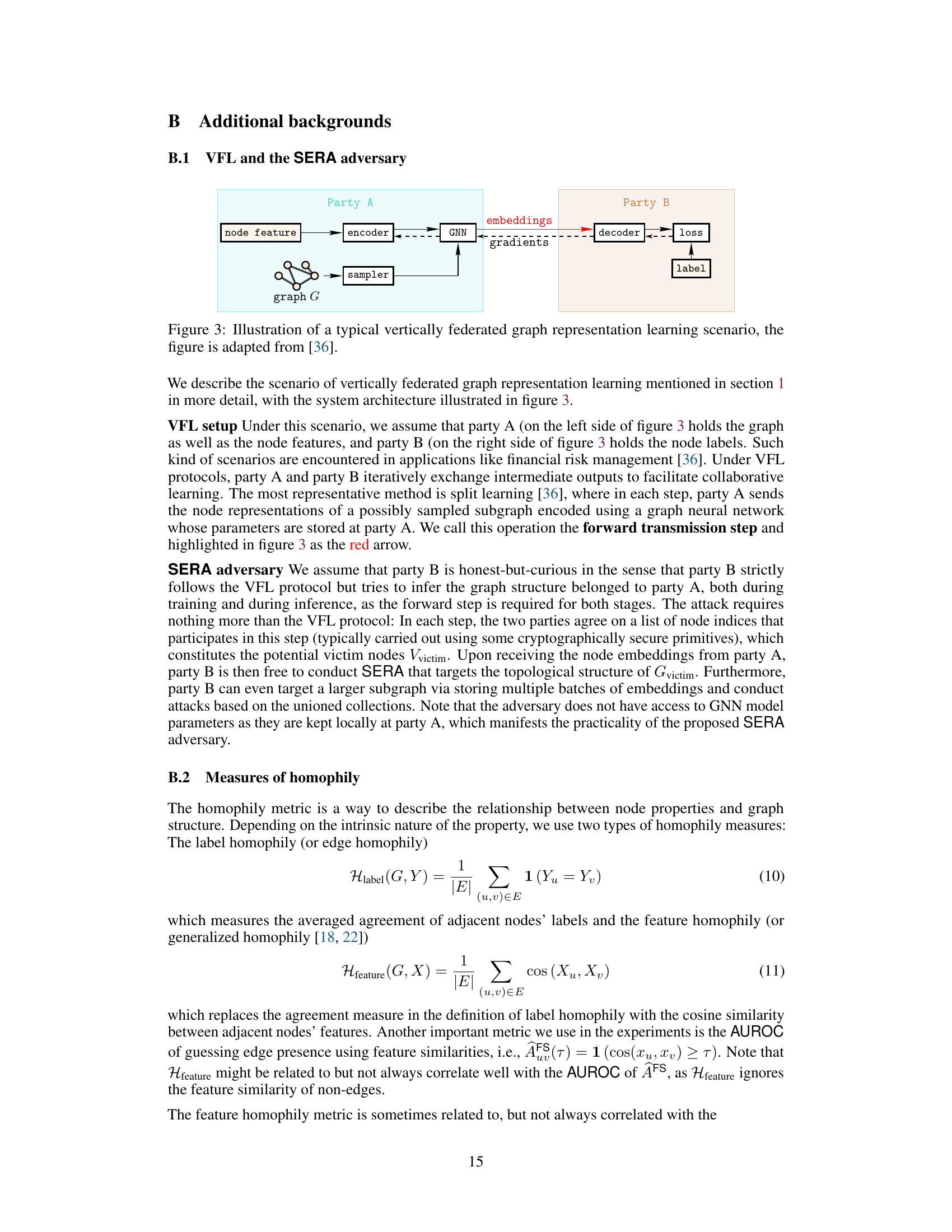

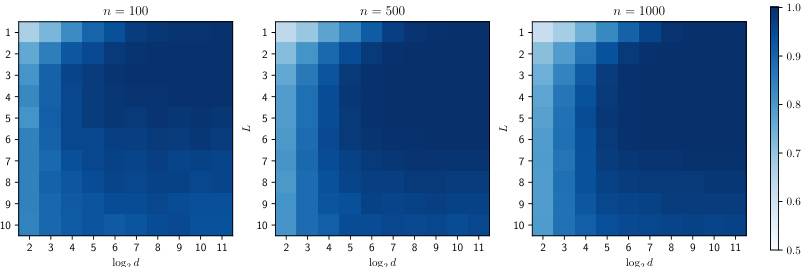

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance is measured using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) metric, averaged over 5 independent trials for each configuration. The heatmaps display how the AUROC varies with different graph sizes (n = 100, 500, 1000) and feature dimensions (d). The purpose of this figure is to illustrate the effectiveness of SERA on sparse graphs and its limitations on dense graphs.

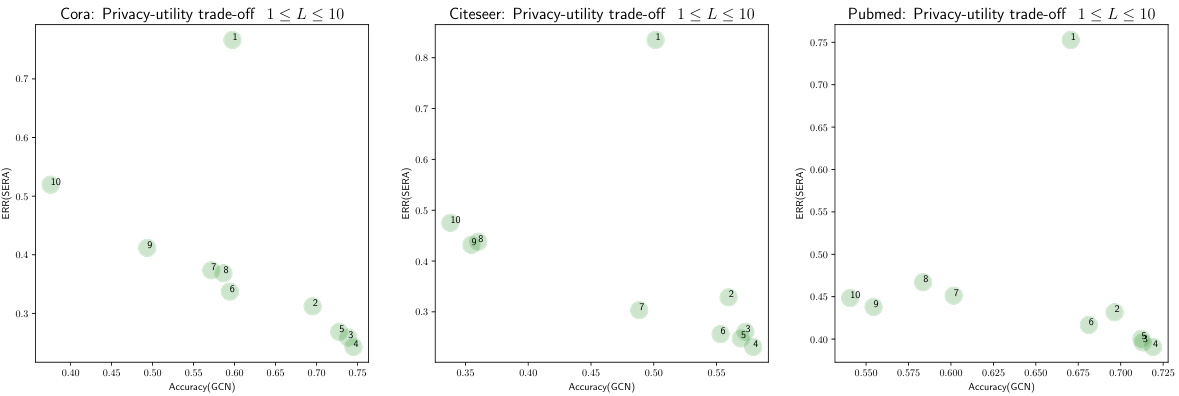

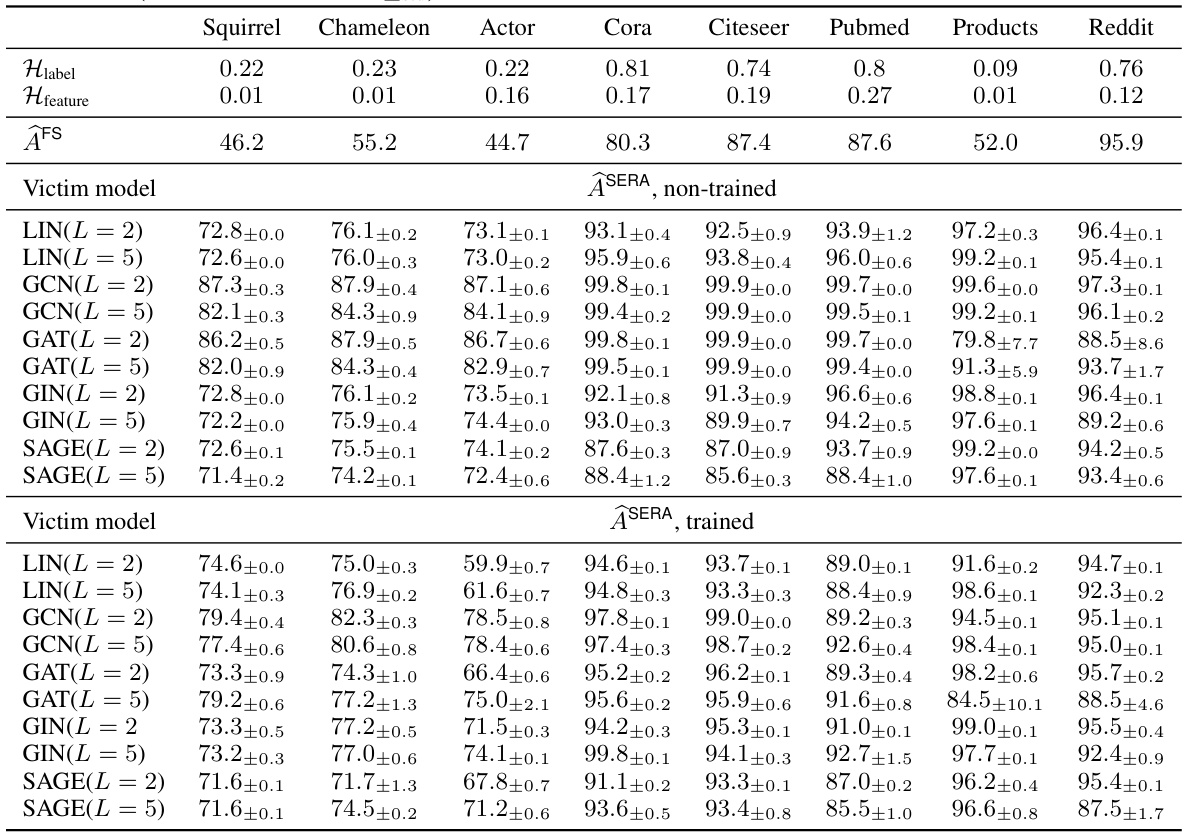

This table presents the performance of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on eight real-world datasets. The performance is measured by the AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) metric, which quantifies the accuracy of edge reconstruction. The table also includes the feature homophily (Hfeature), which measures the correlation between node feature similarity and edge presence, and the baseline attack performance (AFS). Results are shown for various GNN models (LIN, GCN, GAT, GIN, SAGE) both before and after training, illustrating how training affects the vulnerability to SERA attacks.

In-depth insights#

SERA’s Success Modes#

The success of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) hinges on several key factors. Graph sparsity plays a crucial role; SERA demonstrates higher efficacy on sparse graphs exhibiting a generalized homophily pattern (correlation between node feature similarity and edge adjacency). The theoretical analysis reveals a non-asymptotic bound on SERA’s reconstruction capacity, showing that it can provably reconstruct sparse random graphs even without relying on feature similarity. This suggests that successful edge reconstruction is achievable even when the correlation between node features and edge structure is minimal. However, SERA’s effectiveness diminishes significantly on dense graphs, as demonstrated with Stochastic Block Models (SBM), where intra-group connection probability directly affects the attack’s performance. In essence, while feature similarity can be a contributing factor, it is not a necessary condition for SERA’s success. The graph’s structural characteristics, primarily its sparsity, are the primary determinants of SERA’s success or failure modes.

SERA’s Failure Modes#

The heading ‘SERA’s Failure Modes’ suggests an investigation into situations where the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) proves ineffective. A key factor highlighted is graph density. While SERA excels against sparse graphs exhibiting homophily (where similar nodes are more likely to be connected), its performance degrades significantly in dense graphs or those lacking strong homophily. This suggests a limitation: SERA’s reliance on node representation similarity to infer edges becomes less reliable as the graph becomes denser. Another contributing factor is the presence of community structures, as exemplified by stochastic block models. When communities have strong internal connectivity, SERA struggles to accurately reconstruct inter-community edges, showcasing limitations in distinguishing between intra- and inter-community relationships based solely on node embeddings. The findings emphasize the critical influence of graph topology and structure on SERA’s efficacy, revealing the need to consider such characteristics to predict attack success and guide the development of privacy-enhancing strategies. Understanding these failure modes is crucial in both assessing the vulnerability of graph neural networks (GNNs) and developing effective defenses.

NAG’s Mitigation#

The section on “NAG’s Mitigation” likely explores the effectiveness of noisy aggregation (NAG) in defending against similarity-based edge reconstruction attacks (SERA). NAG introduces noise during the graph neural network’s aggregation process to protect sensitive edge information. The authors probably present both theoretical analysis (e.g., privacy guarantees, error bounds) and empirical evaluations to demonstrate how NAG affects SERA’s accuracy. A key aspect will likely involve the trade-off between privacy and utility, showing that adding more noise increases privacy but reduces the model’s predictive capabilities. The analysis may delve into different noise distributions, noise scales, and GNN architectures, assessing their impact on SERA’s performance and the overall privacy-utility balance. Real-world datasets are likely used to test the mitigation strategy, providing a realistic assessment of NAG’s effectiveness in protecting graph data against privacy attacks. The results would show that NAG is beneficial in certain scenarios, but not a perfect solution for all conditions.

Sparse Graph Analysis#

Analyzing sparse graphs within the context of graph neural networks (GNNs) reveals crucial insights into the trade-off between privacy and utility. Sparse graphs are particularly vulnerable to attacks that reconstruct sensitive topological information from node representations. A theoretical analysis, focusing on similarity-based edge reconstruction attacks (SERA), demonstrates that SERA’s effectiveness is deeply connected to graph sparsity, highlighting the importance of this property in analyzing GNN security. Empirically validating these findings on both synthetic sparse random graphs and real-world datasets further emphasizes the impact of graph sparsity on the success of SERA. This detailed analysis contributes substantially to a more comprehensive understanding of privacy vulnerabilities in GNNs, ultimately informing the development of more robust privacy-preserving techniques.

Dense Graph Limits#

The concept of ‘Dense Graph Limits’ in the context of graph representation learning (GRL) and privacy attacks focuses on the limitations of similarity-based edge reconstruction attacks (SERA) when applied to dense graphs. Dense graphs, unlike sparse ones, possess significantly more edges, making it computationally expensive and theoretically challenging to reconstruct the entire graph structure using SERA. This is because the similarity-based approach relies on pairwise comparisons of node representations, which becomes less informative as the graph density increases. The increase in the number of edges and their inter-dependencies significantly reduces the predictive power of node similarity for accurate edge reconstruction. Therefore, sparsity becomes a critical factor in the efficacy of SERA, with dense graphs posing a considerable challenge for such attacks. Alternative, potentially more powerful attack mechanisms may be required to successfully compromise the privacy of GRL models trained on dense graphs. Future research should investigate the theoretical limitations of SERA in the dense graph regime, exploring whether other types of attacks might be more successful.

More visual insights#

More on figures

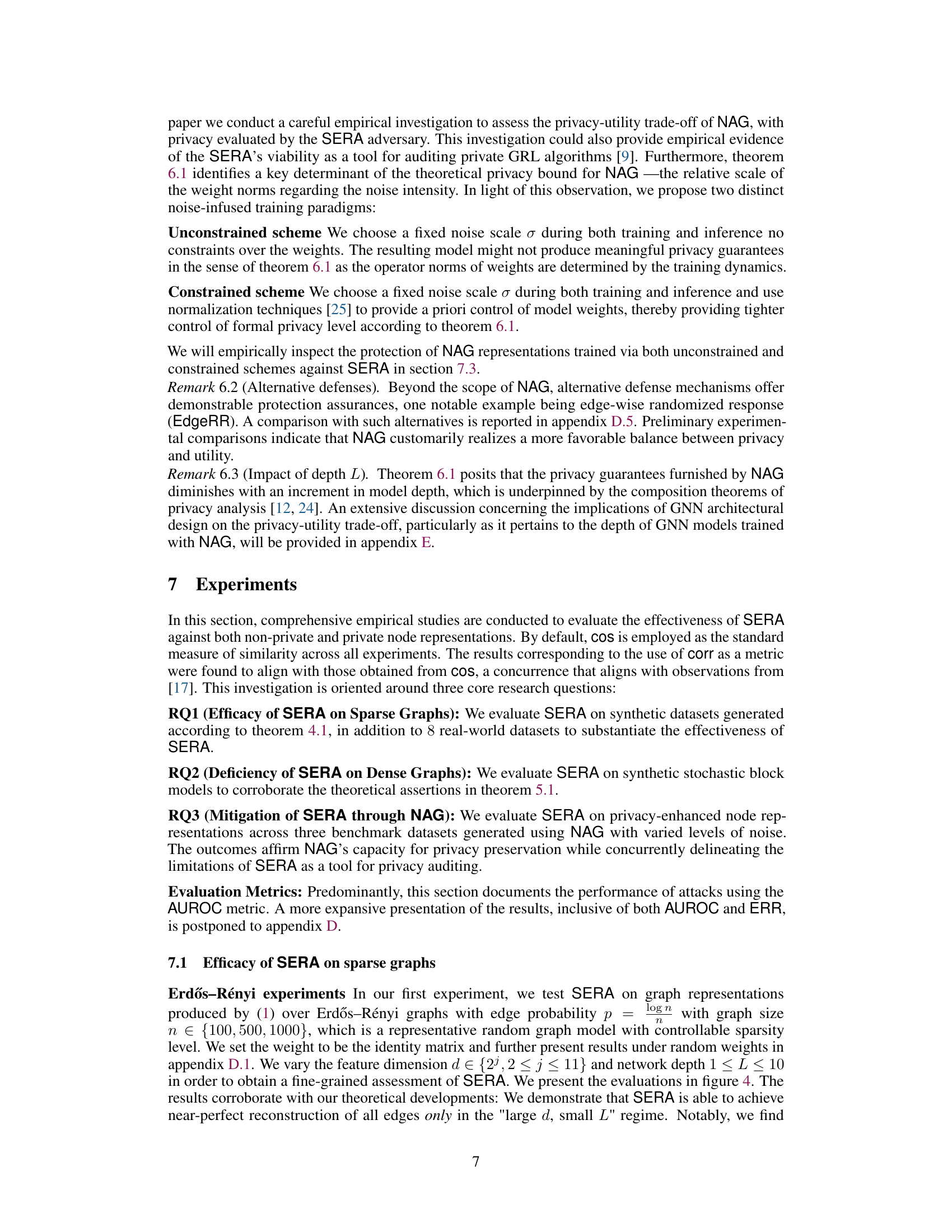

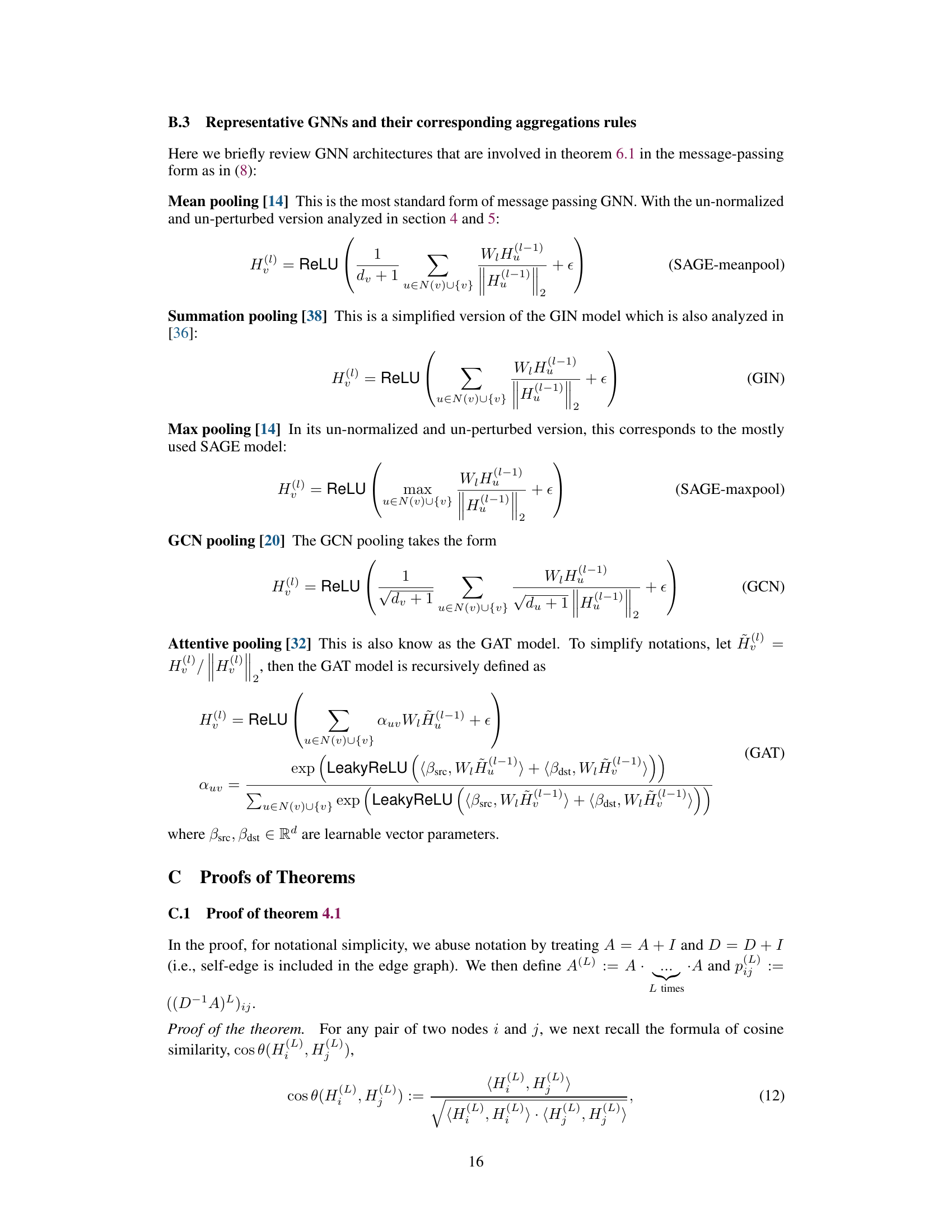

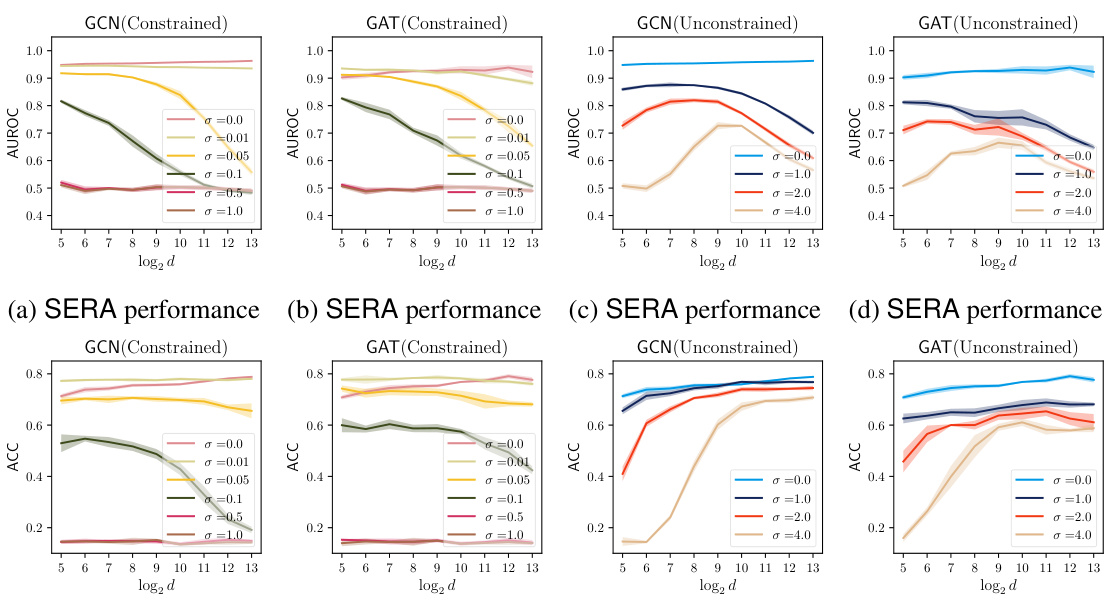

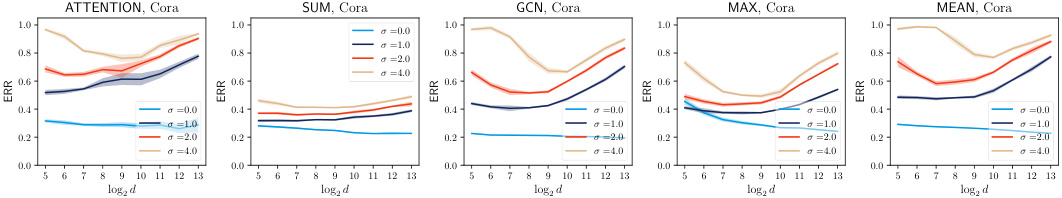

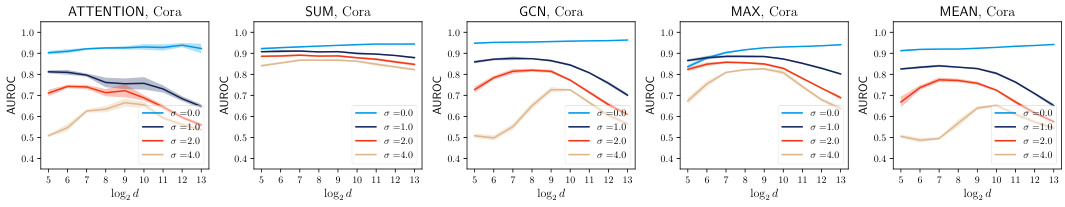

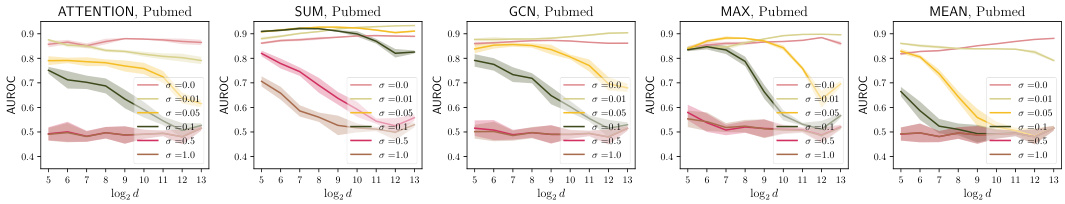

This figure displays the results of evaluating the privacy-utility trade-off of noisy aggregation (NAG) against similarity-based edge reconstruction attacks (SERA) on the Cora dataset. Two different training schemes for NAG are compared: a constrained scheme and an unconstrained scheme. The top row shows the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) for SERA, a metric indicating its effectiveness in reconstructing edges. The bottom row shows the accuracy of the GCN and GAT models under the different NAG training schemes. This demonstrates how the noise level (σ) and feature dimension (d) impact both privacy (SERA performance) and utility (model accuracy).

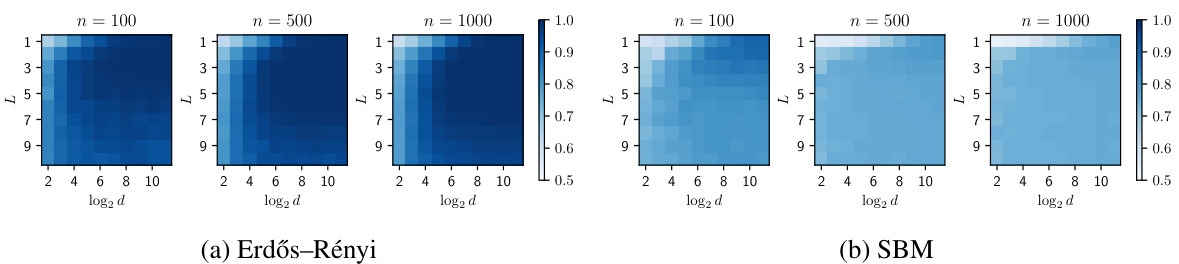

This figure illustrates the architecture of a vertically federated graph representation learning scenario. In this setting, Party A holds both the graph structure and node features, while Party B possesses only the node labels. The learning process involves iterative communication between the two parties: Party A sends embeddings from a sampled subgraph (generated by the encoder and GNN) to Party B, while Party B sends gradients back to Party A. The red arrow emphasizes the embeddings that are sent to Party B. This process allows for collaborative training without sharing raw data, but it also creates opportunities for privacy violations as Party B can attempt to infer the structure of the graph (held by Party A) from the received embeddings.

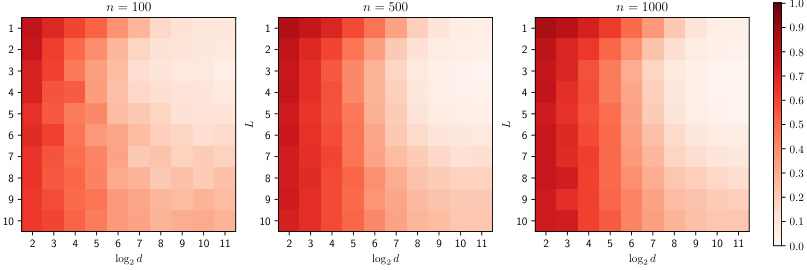

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the effectiveness of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs. The heatmaps display the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the Error Rate (ERR) for different combinations of feature dimension (d) and GNN encoder depth (L). Darker colors in the AUROC heatmaps indicate higher attack performance, while lighter colors in the ERR heatmaps indicate higher attack performance. The results are presented for three different graph sizes (n = 100, 500, and 1000).

This figure displays the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs, a type of random graph. The heatmaps show the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the Error Rate (ERR) for various combinations of feature dimension (d) and graph neural network (GNN) encoder depth (L). Darker colors in the AUROC heatmap indicate higher attack performance while lighter colors in the ERR heatmap indicate better performance. The results show that SERA’s success is influenced by both d and L. The figure supports the findings described in Section 4 of the paper.

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs. The heatmaps illustrate the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the Error Rate (ERR) for various graph sizes (n = 100, 500, 1000) across different feature dimensions (d) and network depths (L). Darker colors in the AUROC heatmaps indicate higher attack success, while lighter colors in the ERR heatmaps indicate lower error rates. The figure demonstrates that the effectiveness of SERA is strongly influenced by the feature dimension (d) and network depth (L).

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs. The heatmaps illustrate the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the Error Rate (ERR) for various combinations of graph size (n), feature dimension (d), and GNN encoder depth (L). Darker colors in the AUROC heatmaps represent higher attack success rates, while lighter colors in the ERR heatmaps indicate lower error rates (meaning better performance). The results demonstrate how the effectiveness of SERA changes based on the interplay of these parameters.

This figure shows the performance of the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on Stochastic Block Models (SBM) with varying numbers of groups (K) and within-group connection probabilities (p). The results, shown as AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) and error rate (ERR), are averaged over five independent trials. The shaded areas represent standard deviations. The figure helps illustrate the impact of the graph’s structure on the SERA attack.

This figure visualizes the performance of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The heatmaps show the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) metric, which indicates the accuracy of SERA in reconstructing edges. Each heatmap represents a different graph size (n = 100, 500, 1000). The x-axis represents the logarithm of the feature dimension (d), and the y-axis represents the depth of the Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder (L). Darker colors represent higher AUROC values (better SERA performance). The results illustrate that SERA is more effective against sparse graphs than dense graphs, and its performance is influenced by the feature dimensionality and GNN encoder depth.

This figure visualizes the results of experiments comparing the effectiveness of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdos-Renyi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic) metric is used to evaluate the performance, averaging results across 5 independent trials for each configuration. The figure helps illustrate how SERA’s success depends on graph properties (sparsity vs. density).

This figure shows the results of the edge reconstruction attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense stochastic block model (SBM) graphs. The x-axis represents the logarithm of the feature dimension (log₂d), and the y-axis represents the AUROC score, a measure of the attack’s performance. Each subplot shows the results for a different graph size (n=100, 500, 1000) for each type of graph. The plots visualize how well SERA can reconstruct edges in graphs with different features and densities. The results demonstrate SERA’s effectiveness on sparse graphs but its limitations on dense graphs.

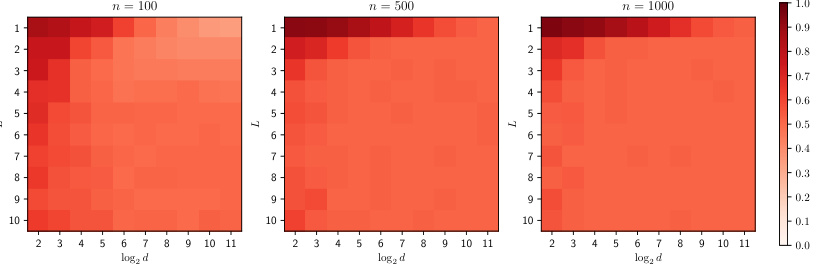

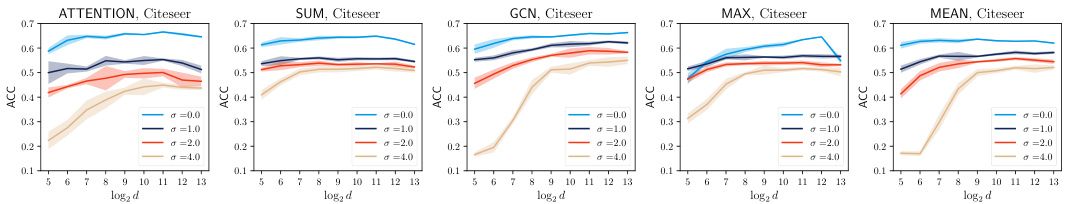

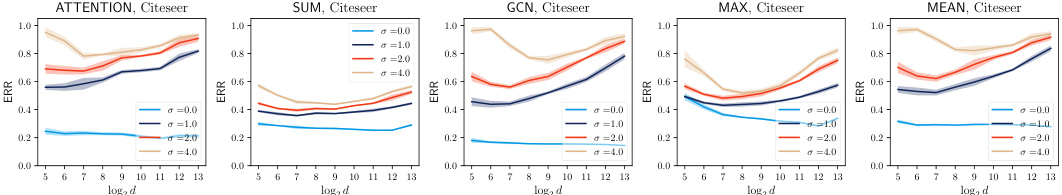

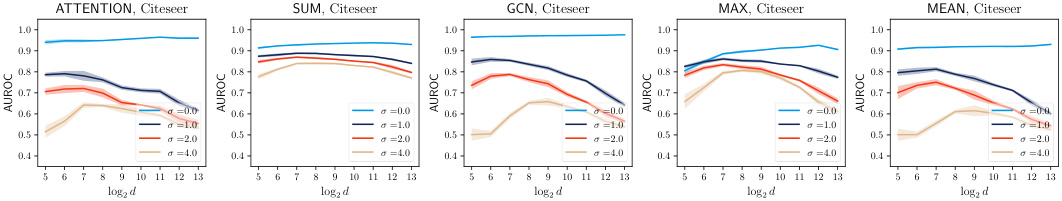

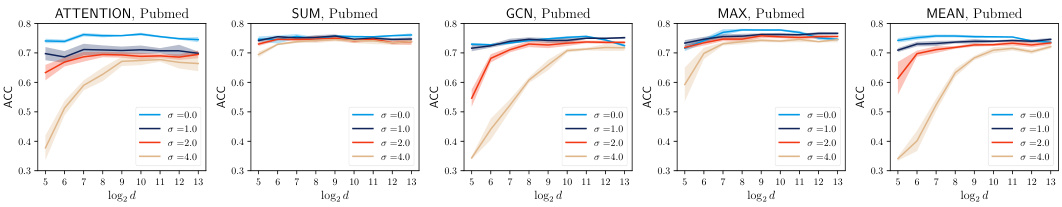

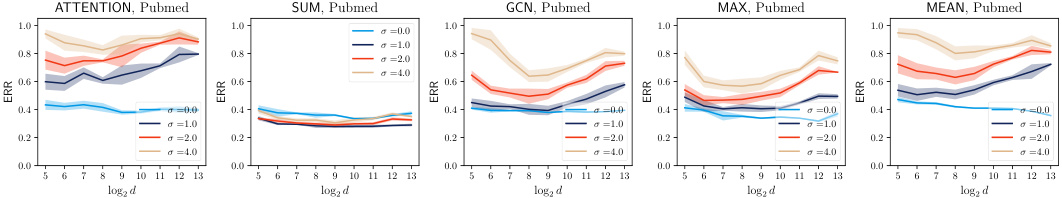

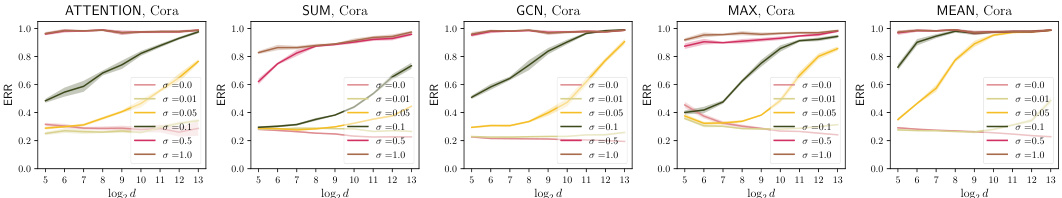

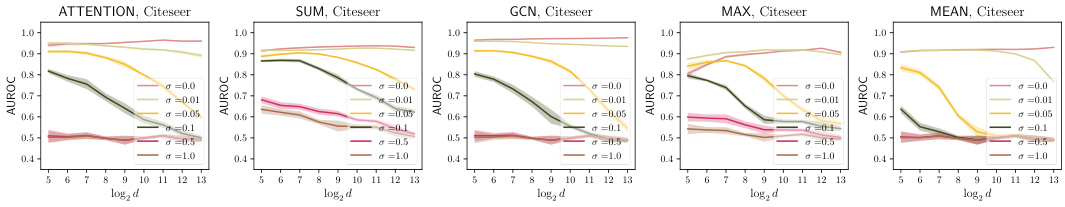

This figure visualizes the trade-off between privacy and utility using the unconstrained training scheme on the Cora dataset. It shows the impact of different noise levels (σ) and feature dimensions (d) on both the model accuracy and the attack success rate (measured by AUROC and ERR). It also shows how different aggregation mechanisms impact this trade-off.

This figure shows the results of experiments on the Cora dataset using the unconstrained training scheme for noisy aggregation (NAG). It displays the trade-off between privacy (measured by the success of the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) and utility (measured by the accuracy of the model). The graphs illustrate how changes in feature dimension (d) and noise scale (σ) affect both privacy and utility. Different aggregation mechanisms (ATTENTION, SUM, GCN, MAX, MEAN) are compared.

This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating the trade-off between privacy and utility when using noisy aggregation (NAG) for training graph neural networks. The experiment was conducted on the Cora dataset using an unconstrained training scheme, meaning there were no constraints on the weights of the model during training. The x-axis represents the feature dimension (log2 scale), and the y-axis displays either AUROC (attack success rate) or accuracy (model performance). Different lines represent different levels of added noise (sigma). The figure shows that increasing the noise level improves privacy (lower AUROC) but reduces utility (lower accuracy). The figure also demonstrates that there are different patterns for different types of aggregation mechanisms.

This figure shows the result of applying noisy aggregation (NAG) with different noise scales (σ) on the Cora dataset, while evaluating the trade-off between privacy and utility. The privacy is assessed using the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA), while the utility is measured by the accuracy of a node classification task. The plots showcase the AUROC and ERR (Error Rate) of SERA across various feature dimensions (d), categorized by different aggregation mechanisms used in the graph neural network (GNN). The unconstrained scheme means that the noise scale is fixed, but the model’s weights are not explicitly controlled during training. The results illustrate how the effectiveness of SERA and the model accuracy change depending on the noise scale and feature dimension.

This figure shows the results of applying Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) to both sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBM). The performance is evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) metric, averaged over 5 independent trials for each configuration. The figure helps to visualize how SERA’s effectiveness varies depending on the graph structure (sparse vs. dense) and the type of graph model used.

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance metric used is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), averaged across 5 independent trials for each configuration. The figure visually represents how well SERA reconstructs edges in each scenario based on the varying parameters of the graphs and the number of features. It serves to demonstrate the effectiveness of SERA on sparse graphs and its limitations on dense graphs, which is further explained and theoretically analyzed within the paper.

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBM). The performance is measured using the AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic) metric, averaged over 5 independent trials for each configuration. It visualizes how the attack’s effectiveness varies depending on the graph structure (sparse vs. dense) and the parameters of the graph generation process. The results provide insights into the conditions under which SERA is more or less effective.

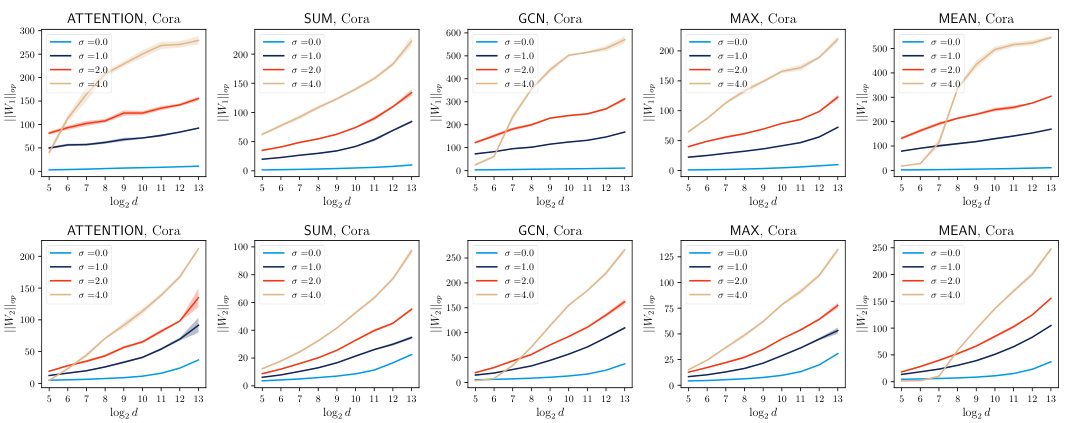

This figure shows the operator norm of the projection weights of the GNN across different aggregation types (ATTENTION, SUM, GCN, MAX, MEAN) and noise levels (σ=0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0) for the Cora, Citeseer, and Pubmed datasets. The results visualize how the operator norms change as the feature dimension increases. This is relevant to the study of privacy-utility tradeoffs using the noisy aggregation method, as the scale of the noise is related to the operator norms.

This figure shows the results of experiments on the Cora dataset using an unconstrained training scheme for noisy aggregation (NAG). It illustrates the trade-off between privacy (measured by the success of SERA attacks) and utility (measured by the accuracy of the GCN and GAT models). The x-axis represents the feature dimension (log2 scale), and the y-axis shows AUROC and accuracy for different noise levels (σ). The figure shows that increasing the feature dimension generally improves privacy and that increasing noise decreases the success of SERA attacks but also reduces model accuracy. The various subplots represent different aggregation mechanisms used in the GNN models.

The figure shows the results of the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBM). The results are shown as heatmaps, where darker colors indicate higher AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) values. This demonstrates the effectiveness of SERA against sparse graphs and its limitations with dense graphs. The X-axis represents the logarithm of the feature dimension (d), and the Y-axis represents the depth of the Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder (L).

This figure presents the results of the SERA attacks on two types of graphs: sparse Erdos-Renyi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance of the attacks is measured using the AUROC metric, averaged across 5 independent trials. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of SERA against sparse graphs and its limitations when dealing with dense graphs. Separate panels show AUROC across different graph sizes (number of nodes n) and feature dimensions (d) for Erdos-Renyi and SBM graphs, revealing the impact of these factors on attack success rate. The color intensity in each heatmap represents the AUROC values, with darker colors indicating higher success rates for SERA.

This figure displays the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance metric used is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), averaged over five independent trials for each configuration. The figure helps visualize how the effectiveness of SERA varies depending on the graph structure (sparse vs. dense) and the parameters used to generate the graphs. This is a key finding of the paper, demonstrating SERA’s effectiveness on sparse graphs and its limitations on dense graphs.

This figure shows the results of two experiments evaluating the efficacy of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) against two different types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBMs). The performance is measured using the AUROC metric, and the results are averaged over 5 random trials for each configuration. The figure helps visualize the impact of graph structure (sparsity vs. density) on the effectiveness of SERA.

This figure shows the privacy-utility trade-off on the Cora dataset using the unconstrained training scheme for NAG. It displays the AUROC and ERR metrics for different aggregation types (ATTENTION, SUM, GCN, MAX, MEAN) against varying feature dimensions (log2 d). Each data point represents the average of 5 independent trials, with shading indicating standard deviation. The results show the balance between privacy (lower ERR and AUROC) and utility (higher accuracy) achieved with different parameter settings.

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The graphs varied in density, with the number of nodes and the feature dimension changing. The results are displayed as heatmaps, where darker colors represent higher AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) scores, and lighter colors represent higher ERR (Error Rate) scores. This helps to visualize the effectiveness of SERA against different graph structures.

This figure shows the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance metric used is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). Each subplot represents a different graph size (n = 100, 500, 1000), and the color intensity represents the AUROC values, with darker colors indicating higher attack success rates. The results demonstrate that SERA is more effective against sparse graphs than dense graphs, consistent with the paper’s findings.

This figure displays the results of applying the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on both sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBM). The performance metric used is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), averaged over five independent trials for each configuration. The plots visualize the relationship between attacking efficacy (AUROC scores) and various graph parameters, such as graph size and feature dimension. This allows an examination of SERA’s effectiveness under differing graph conditions.

This figure shows the results of the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Model (SBM) graphs. The performance metric used is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), which is averaged over 5 independent trials for each configuration. The figure helps to illustrate how the effectiveness of SERA varies depending on graph type and other parameters (such as the number of nodes).

This figure visualizes the performance of Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attacks (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBM). The results are averaged over 5 independent trials and displayed using the AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) metric. It shows how the effectiveness of SERA changes depending on various factors such as graph size (n), feature dimension (d), and the depth (L) of the Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of SERA on sparse graphs and its limitations on dense graphs.

This figure shows the results of the similarity-based edge reconstruction attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense stochastic block model (SBM) graphs. The performance metric used is the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). The results are averaged over five random trials for each configuration. The figure visually represents the effectiveness of SERA under different conditions. The color intensity (darker = better SERA performance) of the grid helps one to visualize the relationship between the effectiveness of SERA and factors such as graph size (n), feature dimension (d), and graph type (sparse vs. dense).

This figure presents the results of evaluating the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on two types of graphs: sparse Erdős-Rényi graphs and dense Stochastic Block Models (SBMs). The performance is measured using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) metric, averaged over 5 independent trials for each configuration. The figure visually compares the success of SERA under different graph structures and parameters.

More on tables

This table presents the performance of the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) on eight real-world datasets. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), a common metric to evaluate the performance of a binary classifier, is used to assess the attack performance. The table compares the AUROC scores achieved by SERA against different graph neural network (GNN) models (trained and untrained) for each dataset. It also shows the feature homophily which is an indicator of the correlation between node features and the presence of edges.

This table presents the results of applying the Similarity-based Edge Reconstruction Attack (SERA) to eight different datasets. The performance of SERA is measured using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) metric, presented as a percentage. The table includes results for various GNN models (LIN, GCN, GAT, GIN, SAGE) with different depths (L=2 and L=5), both with and without prior training. The table also shows the feature homophily, a measure of the correlation between feature similarity and edge presence in each dataset.

Full paper#