↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) often exhibit unpredictable behaviors, particularly when dealing with context-dependent tasks like recalling items from a list. This paper focuses on understanding how information flows between layers within these models. These unexpected failures are particularly challenging because they lack consistency, making it very difficult to predict when a model will fail.

The researchers in this paper address these issues by using a novel method that combines circuit analysis and singular value decomposition (SVD) to identify and analyze low-rank communication channels between different parts of the model. This method allows them to pinpoint the specific mechanisms that cause the model to exhibit prompt sensitivity, such as the low-rank subspaces used for selective inhibition. The findings demonstrate the surprisingly intricate and interpretable structure learned during model pretraining and provide insights into how these seemingly arbitrary sensitivities arise.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on interpretability and model behavior in large language models (LLMs). It provides valuable insights into the intricate internal mechanisms of LLMs, helping to explain their sometimes unpredictable behavior. The identified communication channels and methods for manipulating internal representations could pave the way for improved LLM design and troubleshooting, especially in addressing prompt sensitivity issues. This study offers novel approaches to interpretability that go beyond simple activation analysis, opening new avenues for deeper understanding and more effective development of LLMs.

Visual Insights#

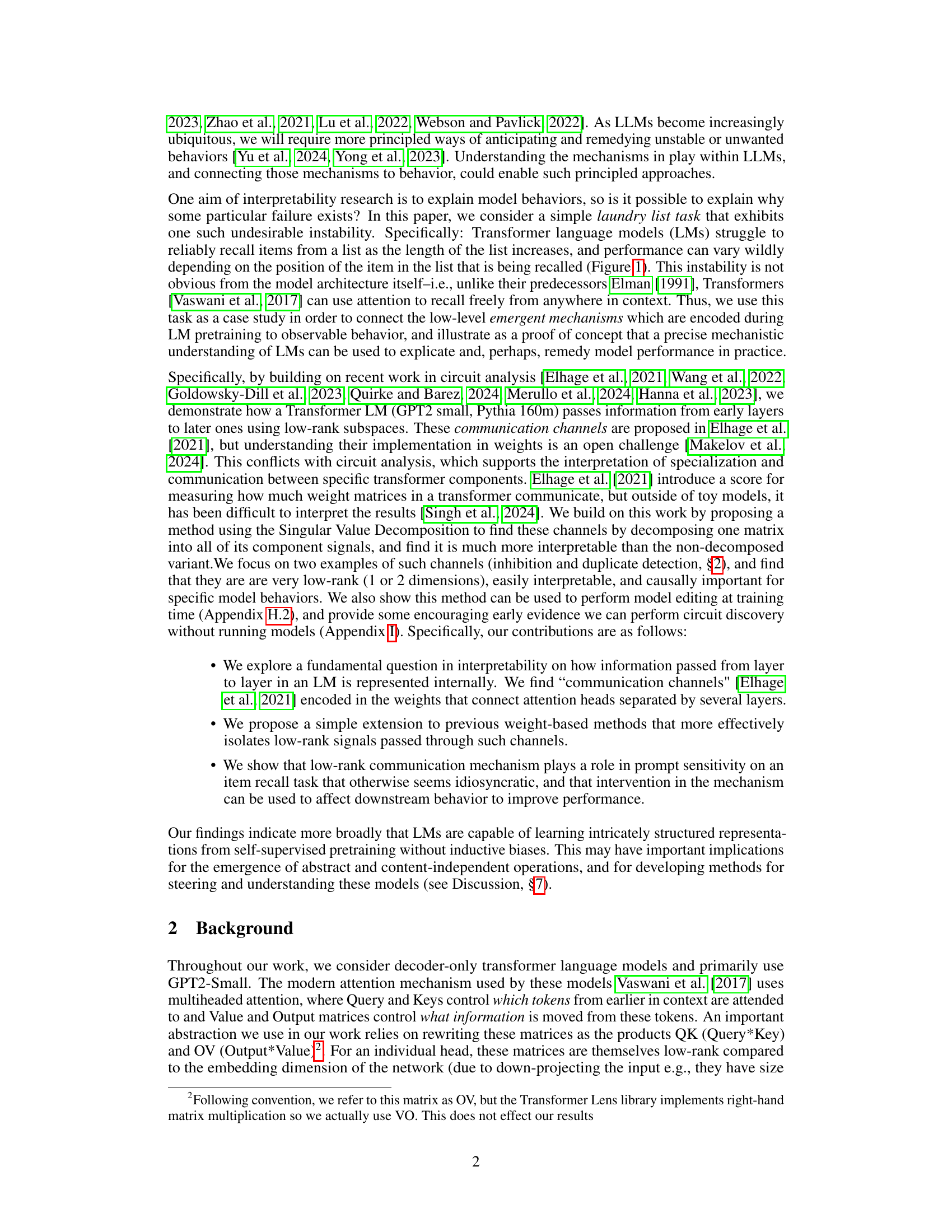

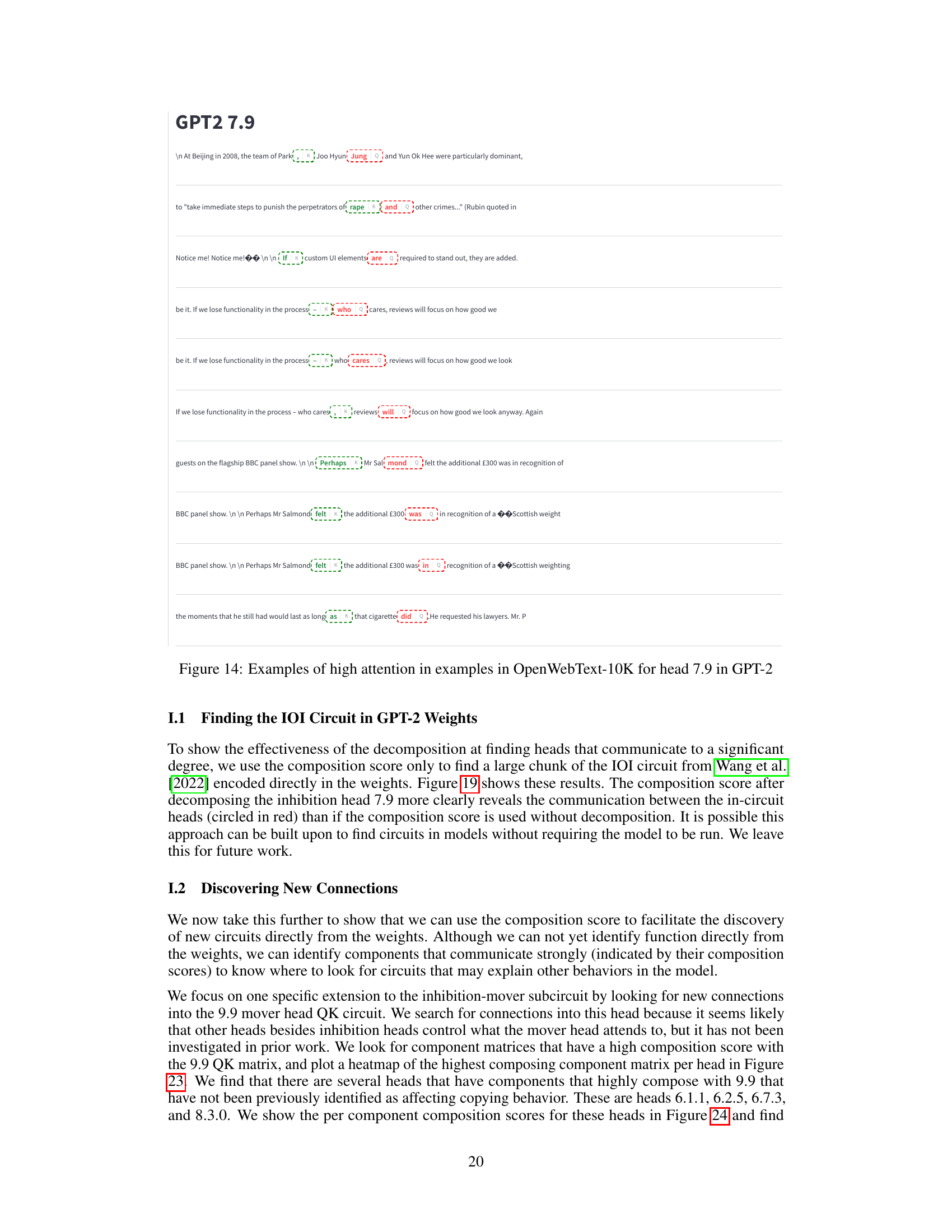

This figure shows the performance of language models on a laundry list task where the model must predict which item from a list is missing based on an incomplete second list. The left panel shows that accuracy decreases as the number of items in the list increases. The right panel shows an example demonstrating sensitivity to the order of items in the prompt. The figure illustrates a key problem the paper addresses: language models exhibit unexpected and arbitrary sensitivity to seemingly minor changes in prompts.

This table lists verbs and their corresponding likely objects. The purpose is to test the attention patterns of head 8.3 in the language model. By comparing the model’s attention to likely and unlikely object-verb pairs, the researchers aimed to determine if head 8.3 has a role in identifying relevant continuations of a given context.

In-depth insights#

Inter-layer comms#

The concept of ‘Inter-layer comms’ in the context of transformer language models (LMs) is crucial for understanding how information flows between different layers. The paper investigates low-rank communication channels, revealing that models utilize low-dimensional subspaces within the residual stream to selectively route information. This mechanism, implemented through weight matrices, allows early layers to influence later layers in a controlled manner. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is a key analytical tool used to identify these low-rank subspaces and quantify their contribution to specific behaviors. The analysis reveals a surprising level of structure in the model’s internal representations, showing that seemingly arbitrary sensitivities to prompts can stem from limitations in how these low-rank channels handle information. Manipulating these channels, as demonstrated in model editing experiments, can significantly improve performance on tasks requiring context retrieval. This detailed mechanistic understanding not only explains model failures in simple domains but also highlights the intricate, interpretable structure learned during pretraining, potentially paving the way for improved model design and more robust performance in complex settings.

Low-rank channels#

The concept of ’low-rank channels’ in transformer language models reveals a crucial mechanism for inter-layer communication. These channels, identified through Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of weight matrices, represent low-dimensional pathways that transmit information between layers. Their low-rank nature suggests efficiency, as the model selectively encodes and decodes features within these constrained subspaces. This mechanism is implicated in various model behaviors, such as selectively inhibiting items in a context or handling positional sensitivity. The ability to identify and manipulate these channels provides an important tool for interpretability, allowing for a more granular understanding of how the models function, and potentially improve performance by specifically targeting these pathways for intervention. Further research is needed to fully explore the generality and implications of low-rank channels across different model architectures and tasks. Understanding low-rank channels helps explain why seemingly simple tasks can sometimes challenge even sophisticated models, highlighting the complexity of information flow within these intricate networks.

Model editing#

The ‘Model Editing’ section presents a crucial methodology demonstrating the causal impact of identified low-rank communication channels within the transformer model. By meticulously manipulating specific singular value components of the weight matrices, the authors directly influence downstream model behavior, particularly in the context of the IOI task. This targeted intervention, going beyond simple weight modification, provides compelling evidence for the functional significance of these low-rank subspaces as genuine communication channels. The results show significant performance improvements after editing, underscoring the interpretability and controllability achieved through this approach. Importantly, the findings highlight the fine-grained control offered by manipulating these low-rank subspaces, enabling precise adjustments to model behavior, and suggesting a path towards a more principled understanding and manipulation of LM internal representations.

Context retrieval#

The concept of ‘context retrieval’ within the scope of transformer language models is a critical aspect of their functionality and a significant area of ongoing research. The paper investigates how these models access and utilize information from preceding parts of the input sequence, specifically focusing on a “laundry list” task that highlights the models’ sensitivity to the order of items. The core finding is that models do not simply retrieve information directly but instead employ a more intricate, low-rank communication mechanism. This mechanism involves writing and reading information within specific, low-dimensional subspaces of the residual stream, creating what the authors refer to as ‘communication channels’. These channels are not random but learned during pre-training and display surprising structure. The ability to manipulate these channels, potentially editing the model’s weights to enhance recall accuracy, highlights the potential of understanding this internal process for improving model performance. Failures in context retrieval are not always systematic but seem to arise when the inherent capacity of these low-rank mechanisms is overwhelmed, suggesting a potential bottleneck limiting the models’ ability to handle more complex information.

Future work#

The paper’s discussion of future work highlights several promising avenues for research. Extending the analysis to larger language models is crucial to determine the generalizability of the findings. The current work focuses on relatively small models, and investigating the same mechanisms in larger, more complex models would validate and strengthen the conclusions. Developing more sophisticated methods for circuit discovery is another critical area. The current approach relies on existing knowledge of model components; automating the process would make the findings more broadly applicable. The authors suggest exploring low-rank subspaces for other tasks and building upon the methodology for weight-based mechanistic analysis to discover circuits without needing to execute models. Investigating the role of specific components within the identified communication channels would significantly enhance the understanding of their function. Connecting their identified mechanisms to other phenomena (like the preference for the last item in the laundry list task) requires additional research. Finally, the authors express a strong desire to explore how learned representations affect downstream behaviors to better understand how such intricate structures emerge during pretraining.

More visual insights#

More on figures

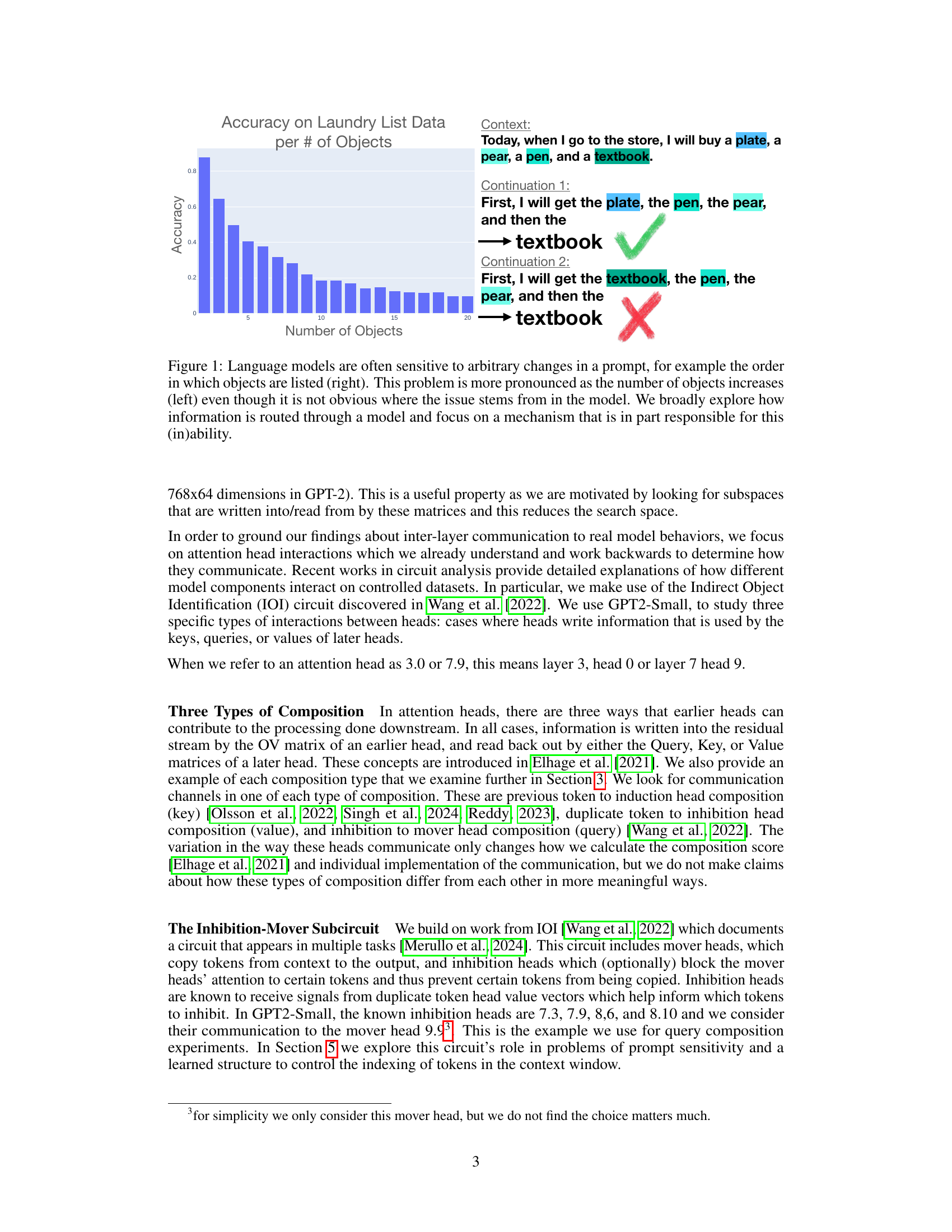

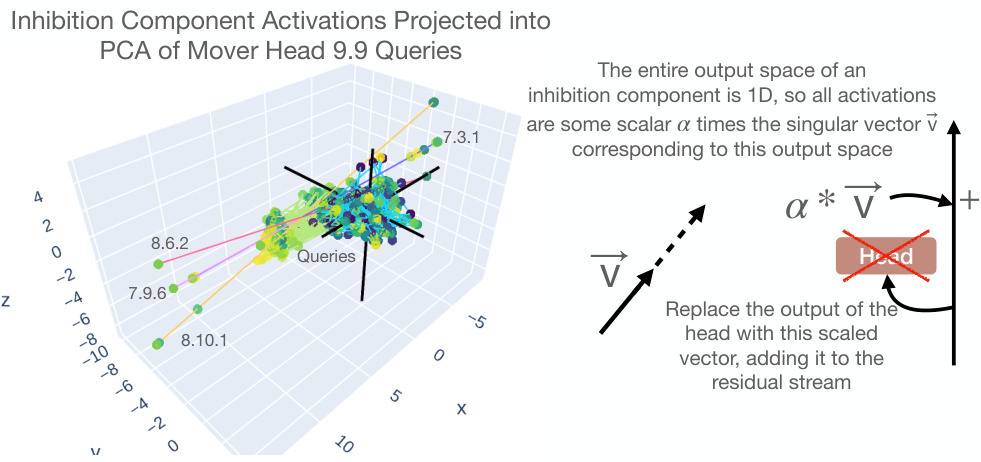

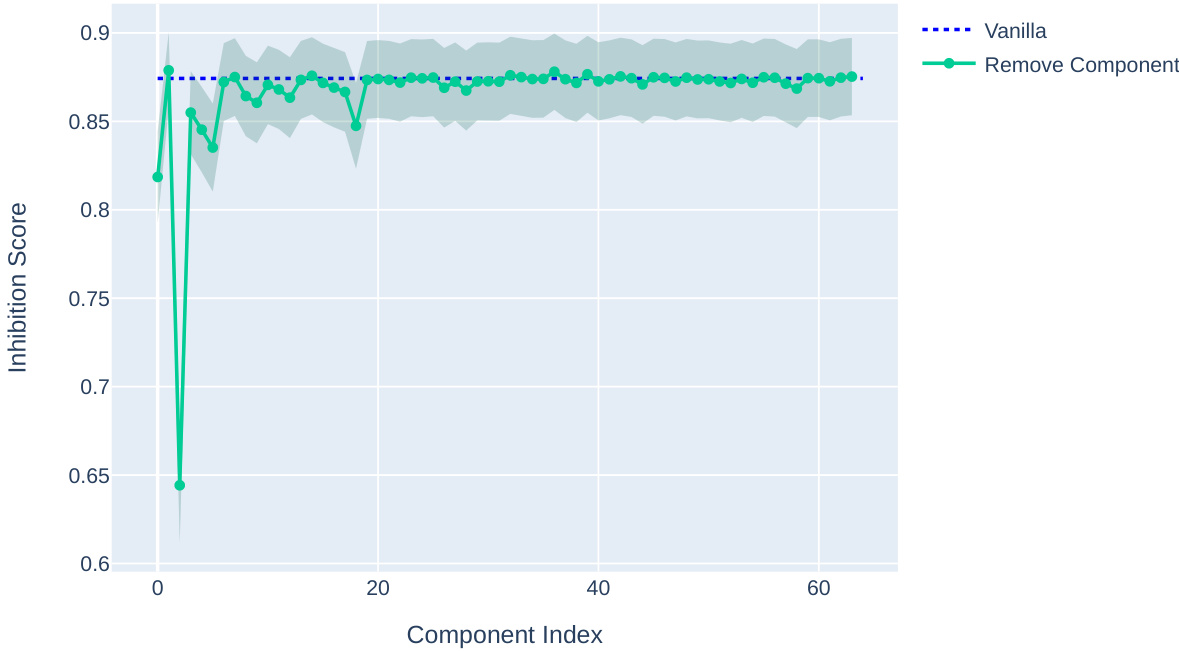

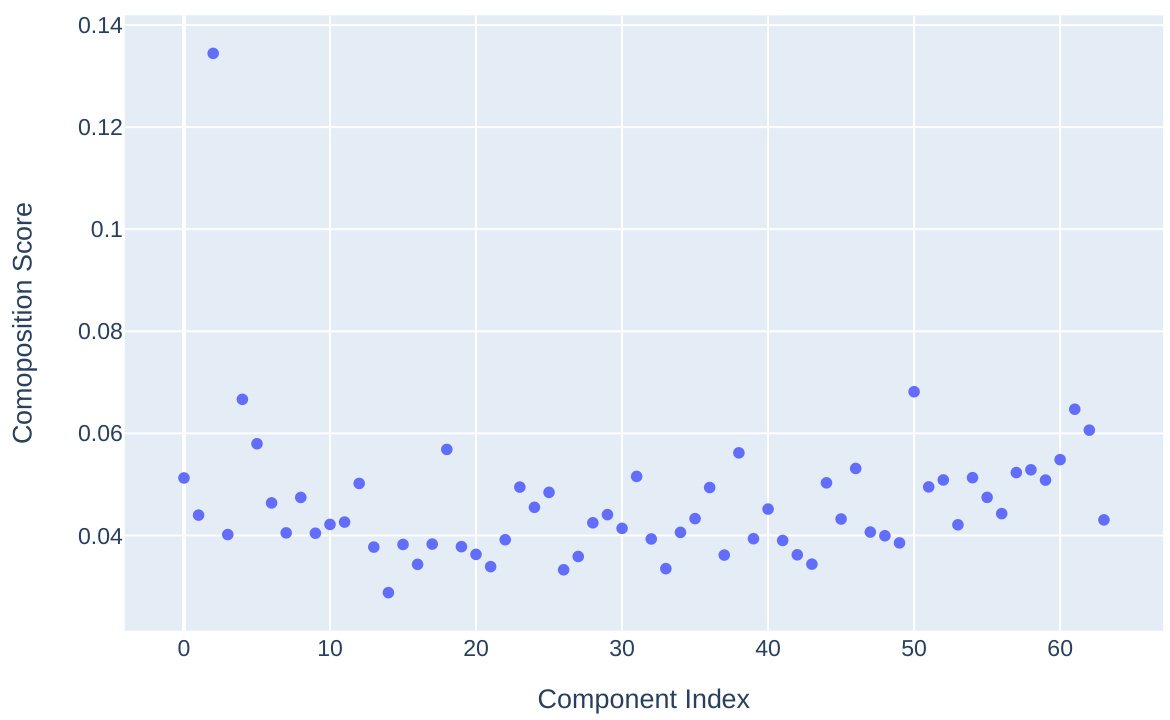

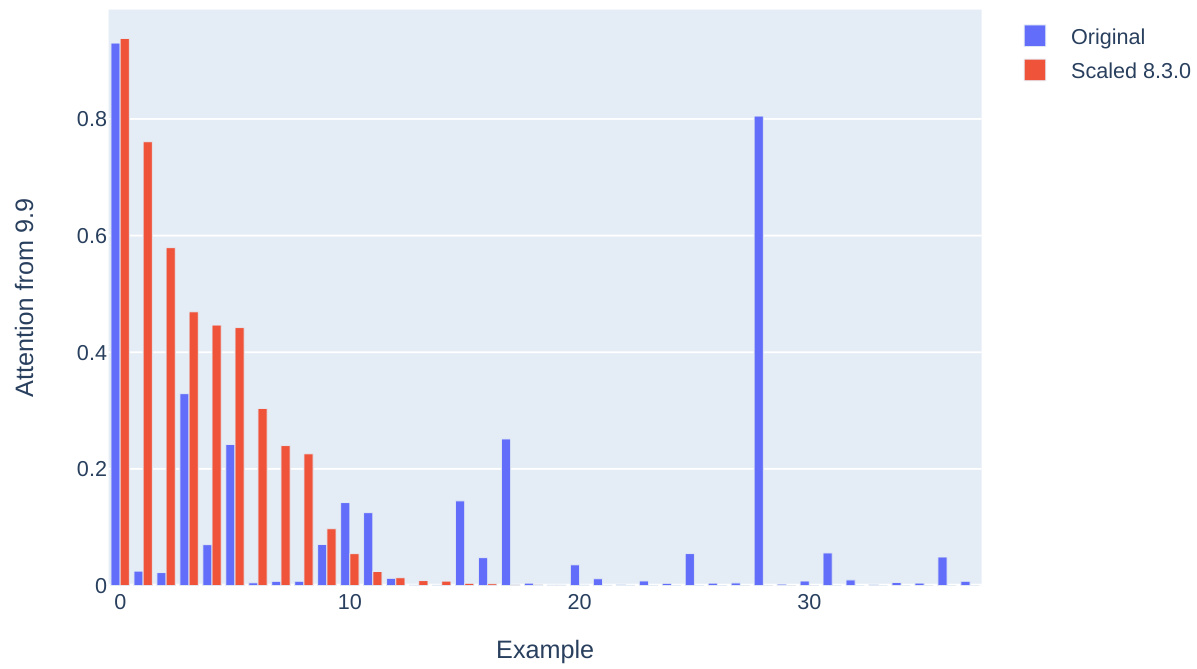

This figure displays the relationship between weight-based composition scores and data-based inhibition scores for different inhibition heads connected to mover head 9.9 in the IOI (Indirect Object Identification) task. The key observation is that the inhibition effect is highly concentrated in one or two components of each inhibition head’s matrix. Removing those specific components significantly reduces the mover head’s capacity to inhibit one of the names in the IOI task, highlighting the importance of low-rank subspaces within the interaction between heads. The visualization demonstrates that using the composition score, especially with the decomposition of component matrices, is effective for analyzing and interpreting the inter-layer communication.

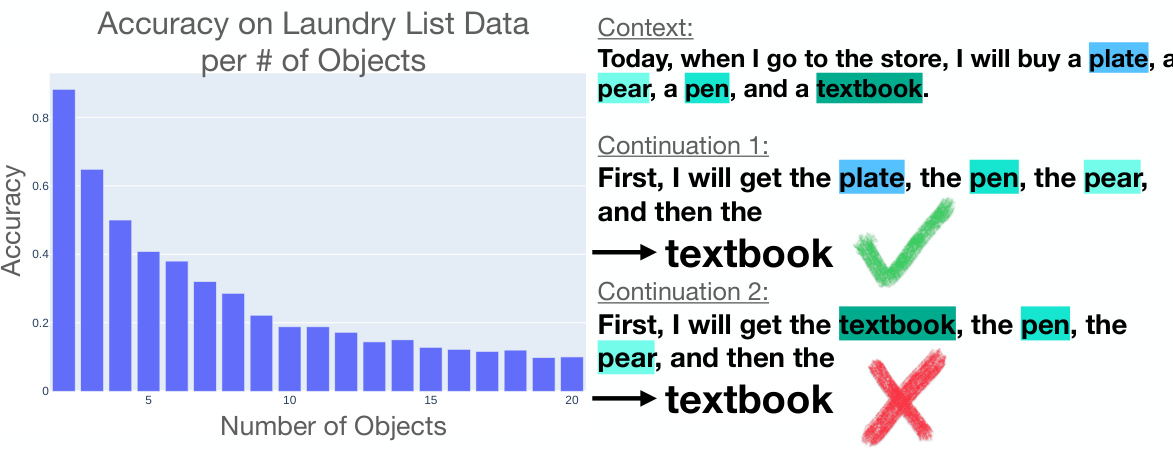

This figure shows that because the component matrices are rank-1, their output spaces are 1D, making them easier to interpret. The left panel displays a PCA of mover head 9.9 queries, showing inhibition component activations distributed along a line. The right panel illustrates how scaling a vector along this line (representing inhibition strength) and adding it to the residual stream or replacing an attention head’s output can change model behavior, as further demonstrated in Figure 4.

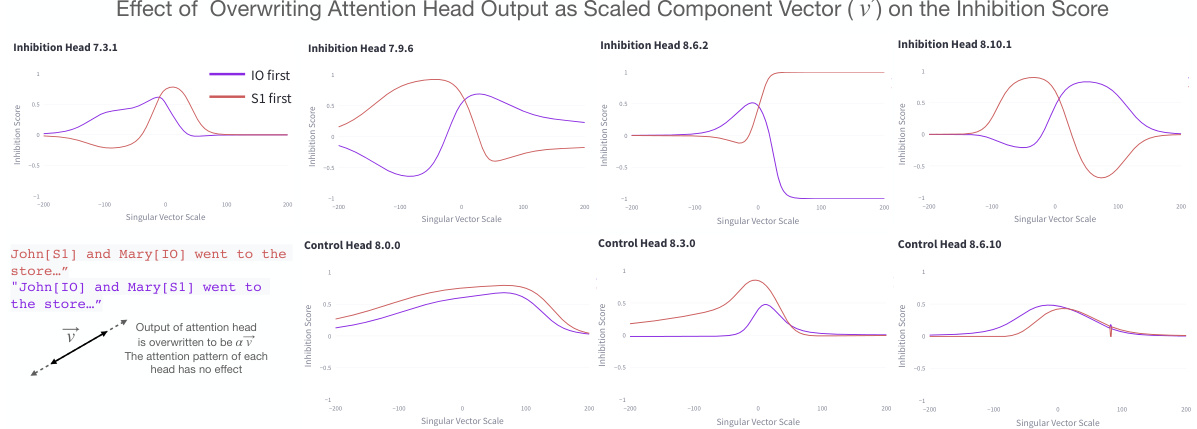

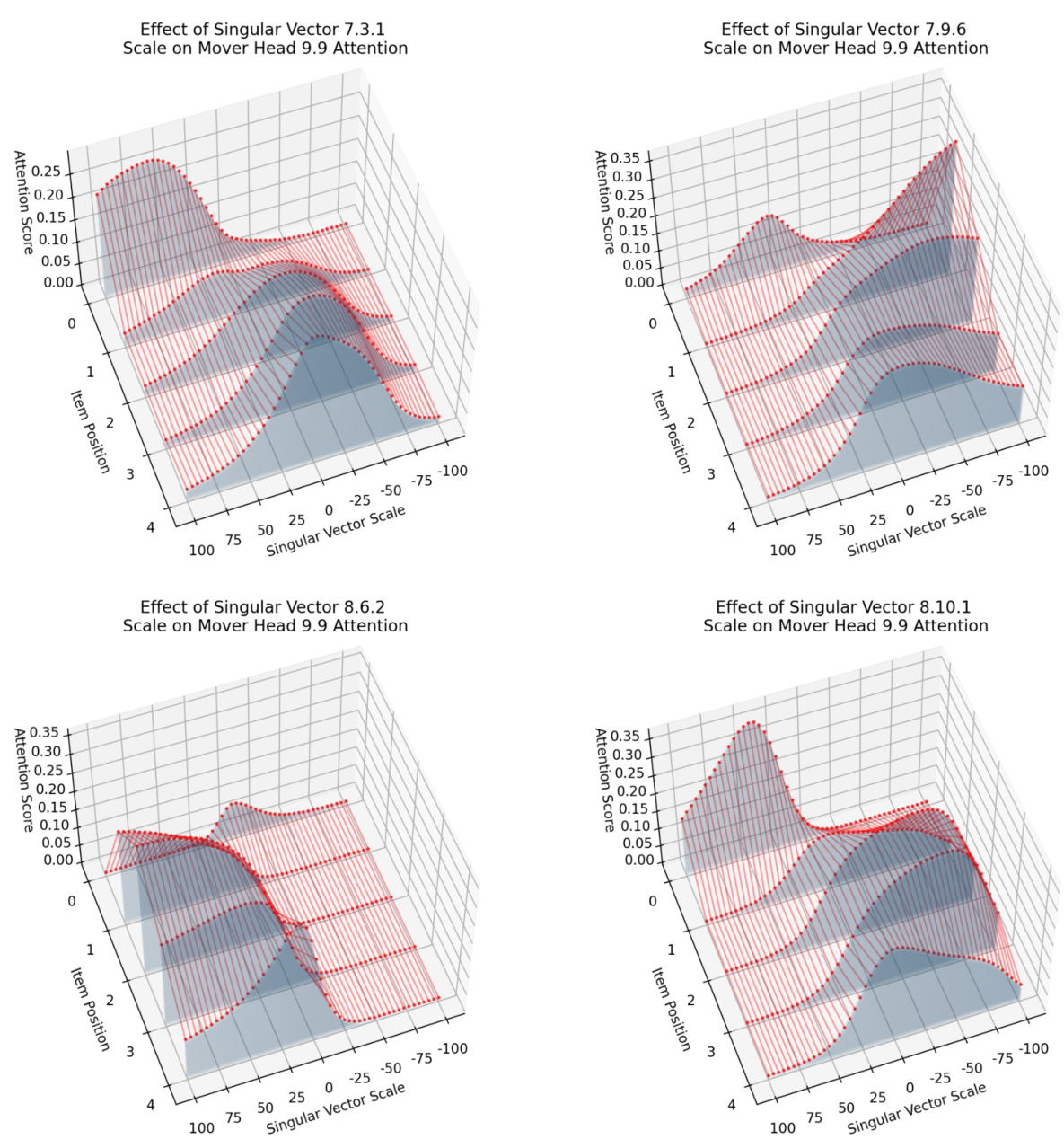

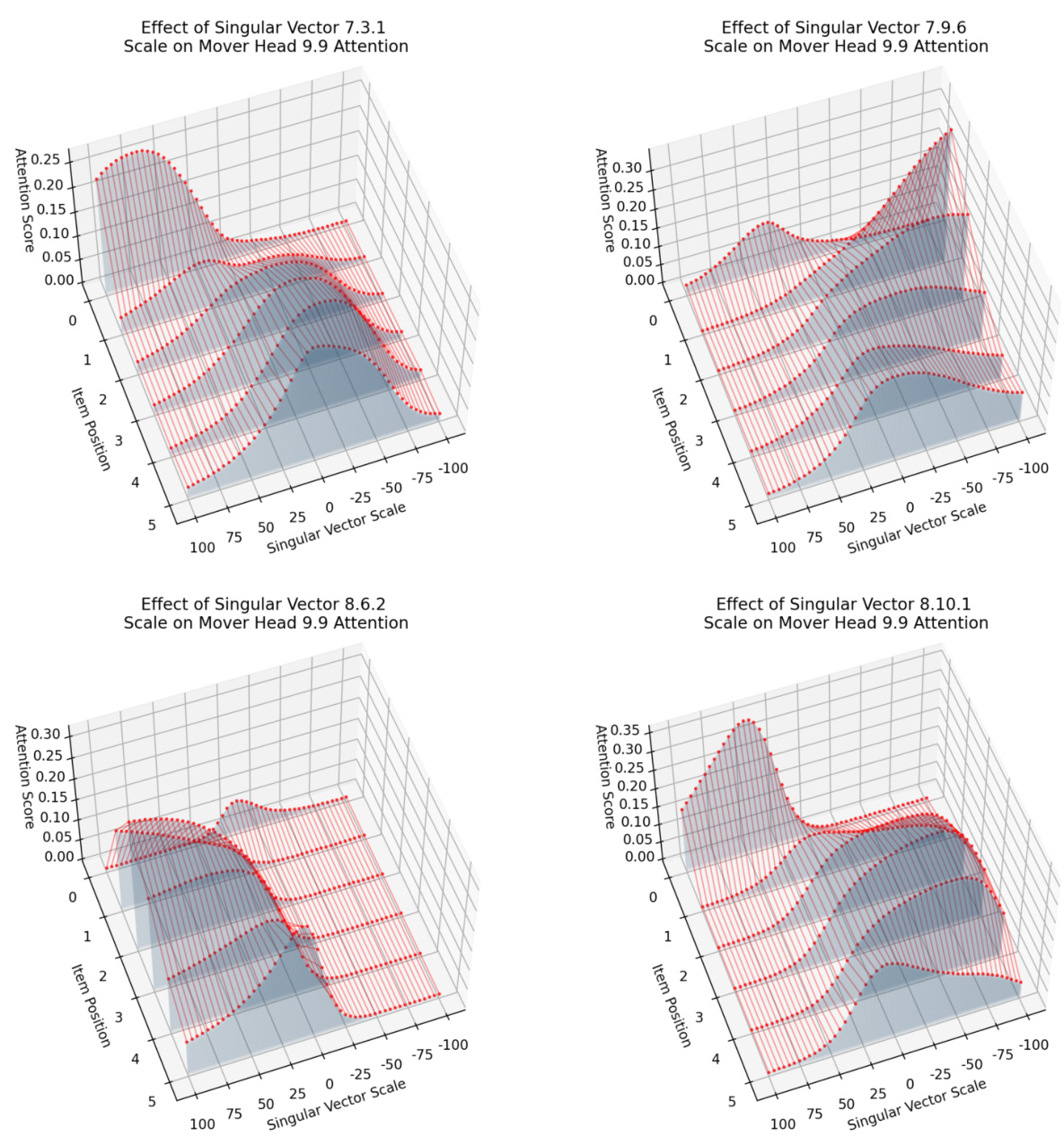

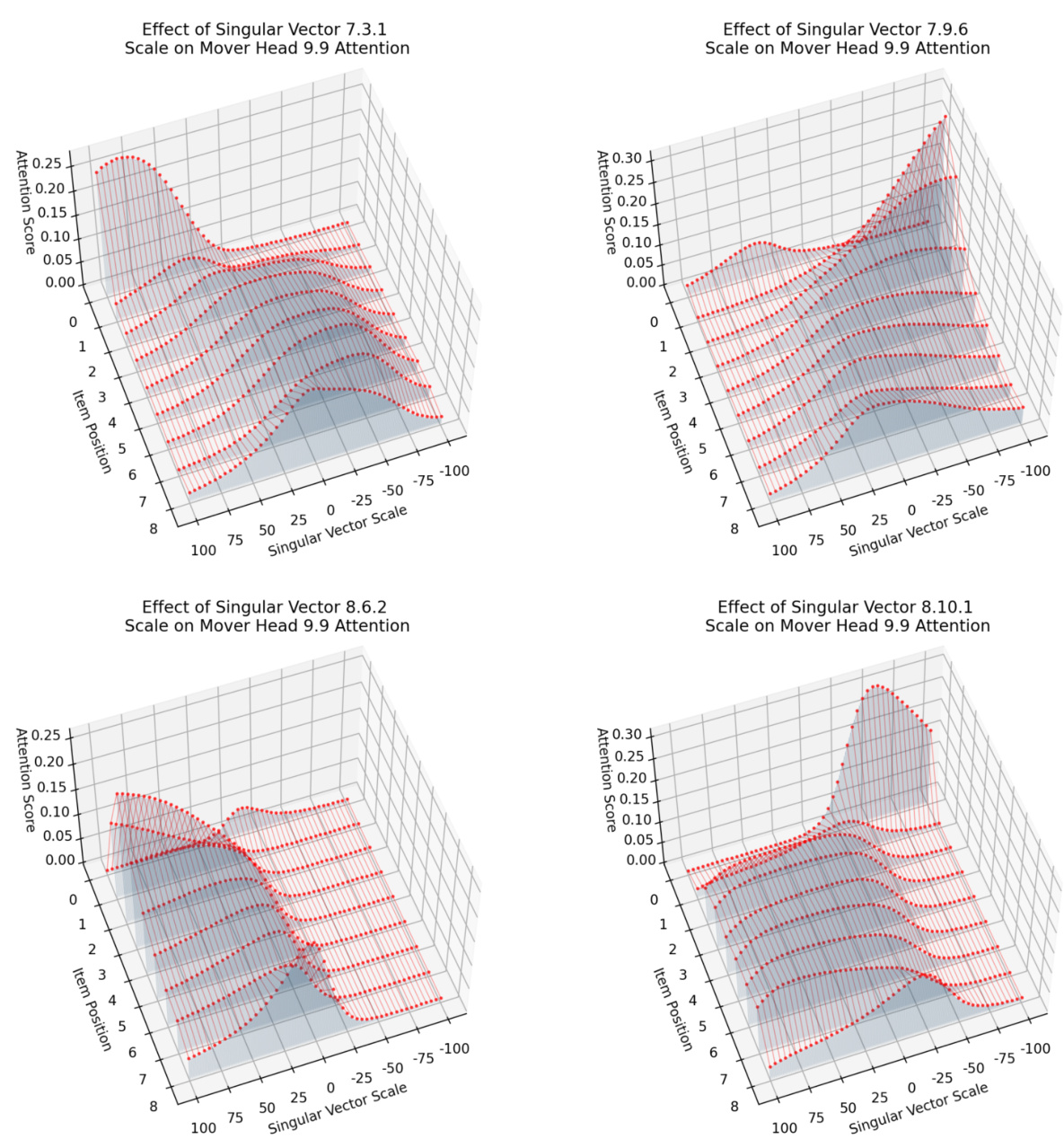

This figure shows the results of experiments manipulating the 1D inhibition components and 2D duplicate token components to control the mover head’s attention. The top part demonstrates that scaling a vector in the 8.10.1 output space can selectively inhibit either the first or second name. The bottom part shows how adding or removing duplicate token information from the duplicate channel affects the inhibition of names. The results highlight the fine-grained control these components exert over the model’s behavior and the specificity of their effects.

This figure shows the results of experiments on manipulating the inhibition components to control the mover head’s attention. The leftmost panel shows that manipulating a single inhibition component is not sufficient to control attention to individual items in a list. The middle panels show that manipulating multiple inhibition components allows for more precise control, but that this ability breaks down as the length of the list increases. The rightmost panel shows the improvement in accuracy after intervention.

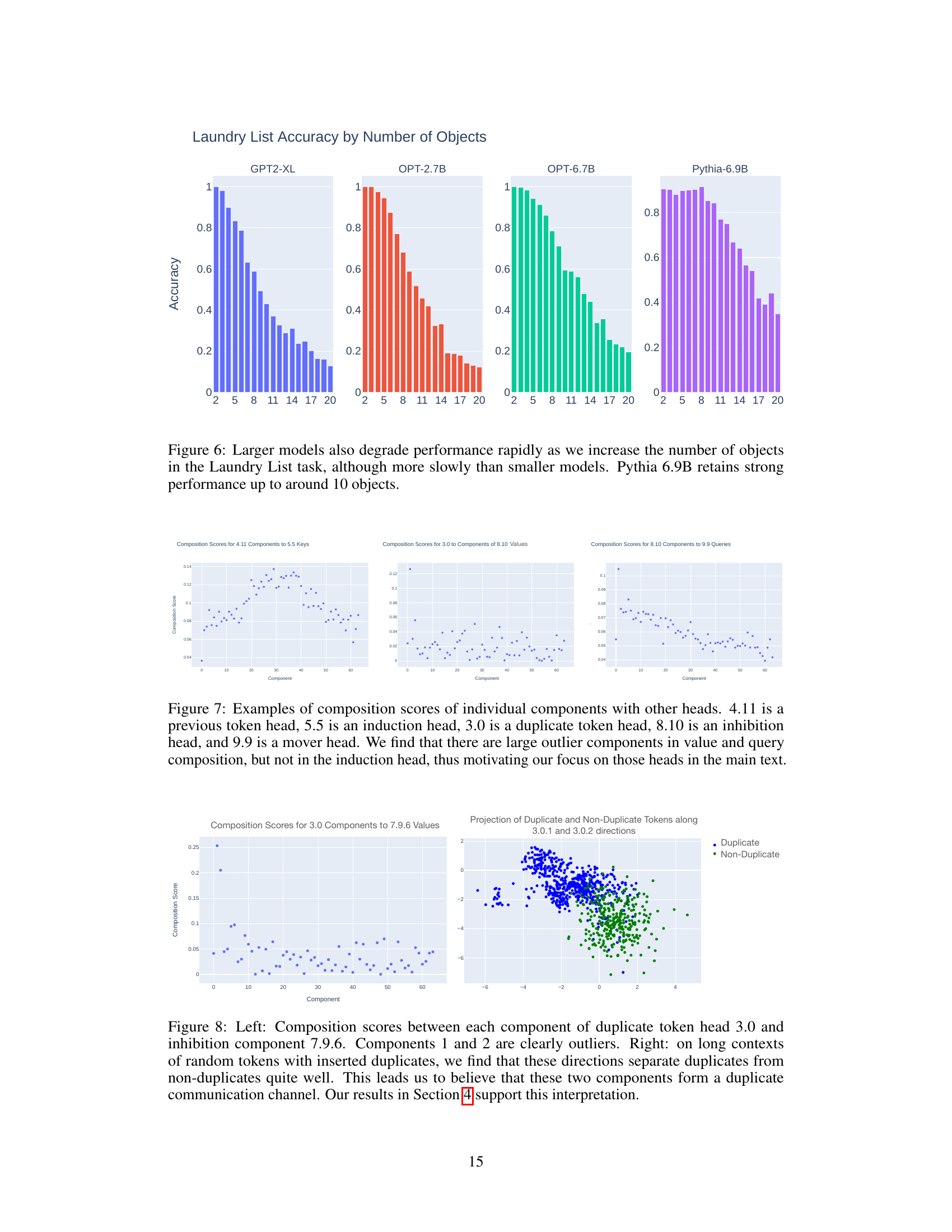

This figure shows the performance of four different language models (GPT2-XL, OPT-2.7B, OPT-6.7B, and Pythia-6.9B) on the Laundry List task as the number of objects in the list increases. The x-axis represents the number of objects, and the y-axis represents the accuracy of the model. As can be seen, the accuracy of all four models decreases as the number of objects increases. However, the larger models (OPT-6.7B and Pythia-6.9B) maintain relatively high accuracy for a larger number of objects compared to the smaller models (GPT2-XL and OPT-2.7B). This suggests that larger models are more robust to the challenges posed by the Laundry List task.

This figure presents composition scores between individual component matrices of different attention heads in a transformer language model. The composition score measures the interaction strength between heads, revealing communication pathways. Three types of compositions are shown: query, value, and key compositions. The figure highlights outlier components with unusually high composition scores in value and query compositions, but not in key composition. These outliers are in heads that play specific roles (duplicate token, inhibition, and mover heads) in established language model circuits. The lack of outliers in the key composition supports the authors’ focus on other types of composition in their subsequent analysis.

This figure displays the relationship between the weight-based composition score and the data-based inhibition score for different inhibition heads in relation to mover head 9.9 within the Indirect Object Identification (IOI) task. The lower graphs show the composition score, while the upper graphs depict the inhibition score. The key observation is the strong concentration of inhibition within one or two components of each inhibition head’s matrix. Removing these components significantly reduces the mover head’s capacity to suppress a name, thus highlighting the importance of these components and the efficacy of using composition scores in the context of decomposed matrices for analysis.

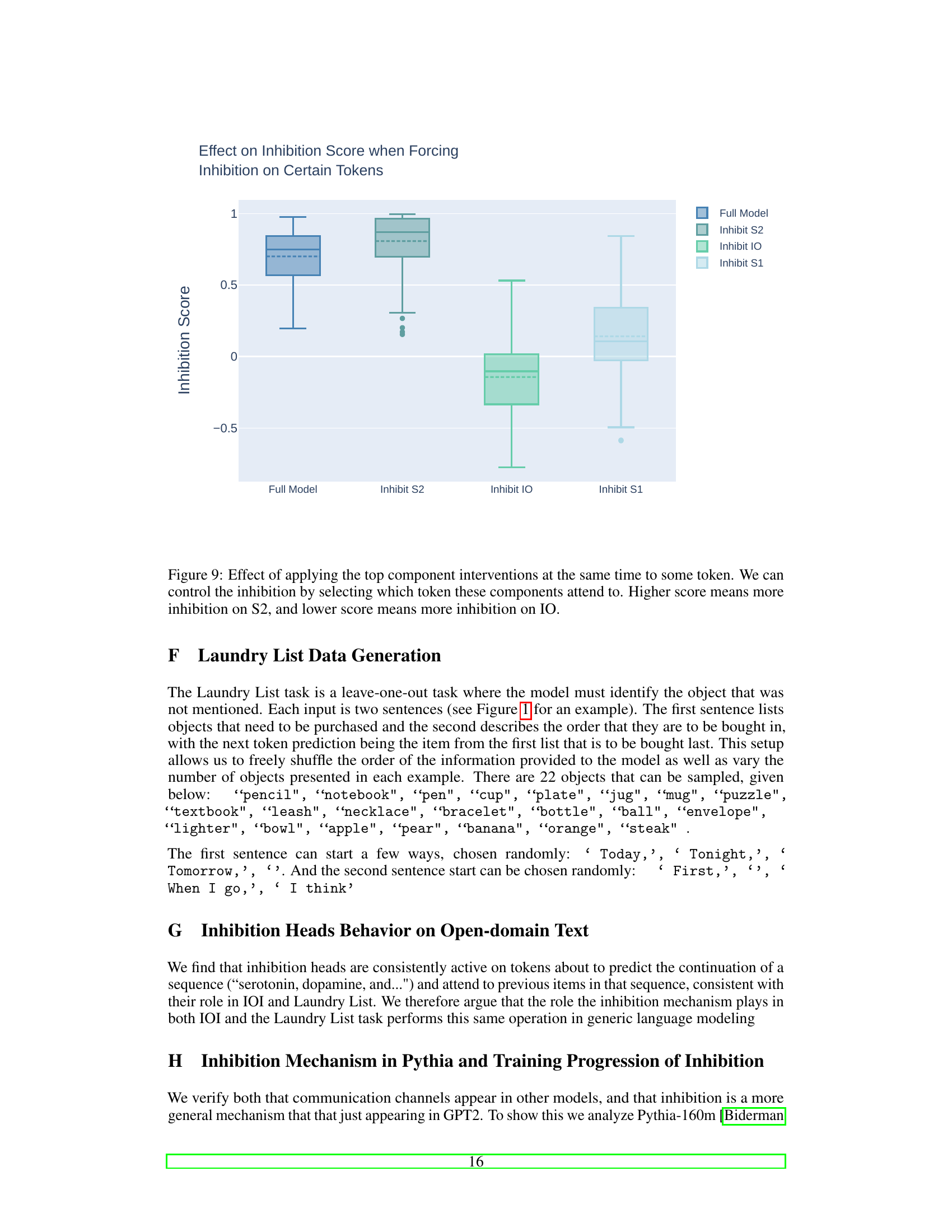

This figure shows the effect of applying top component interventions to some tokens. By selectively zeroing out components of the inhibition heads, the researchers can influence which token (IO or S1) receives less attention from the mover head (9.9). A higher score indicates more inhibition on S2, while a lower score means more inhibition on IO. This demonstrates the ability to manipulate the model’s selective attention behavior by directly targeting specific component interactions.

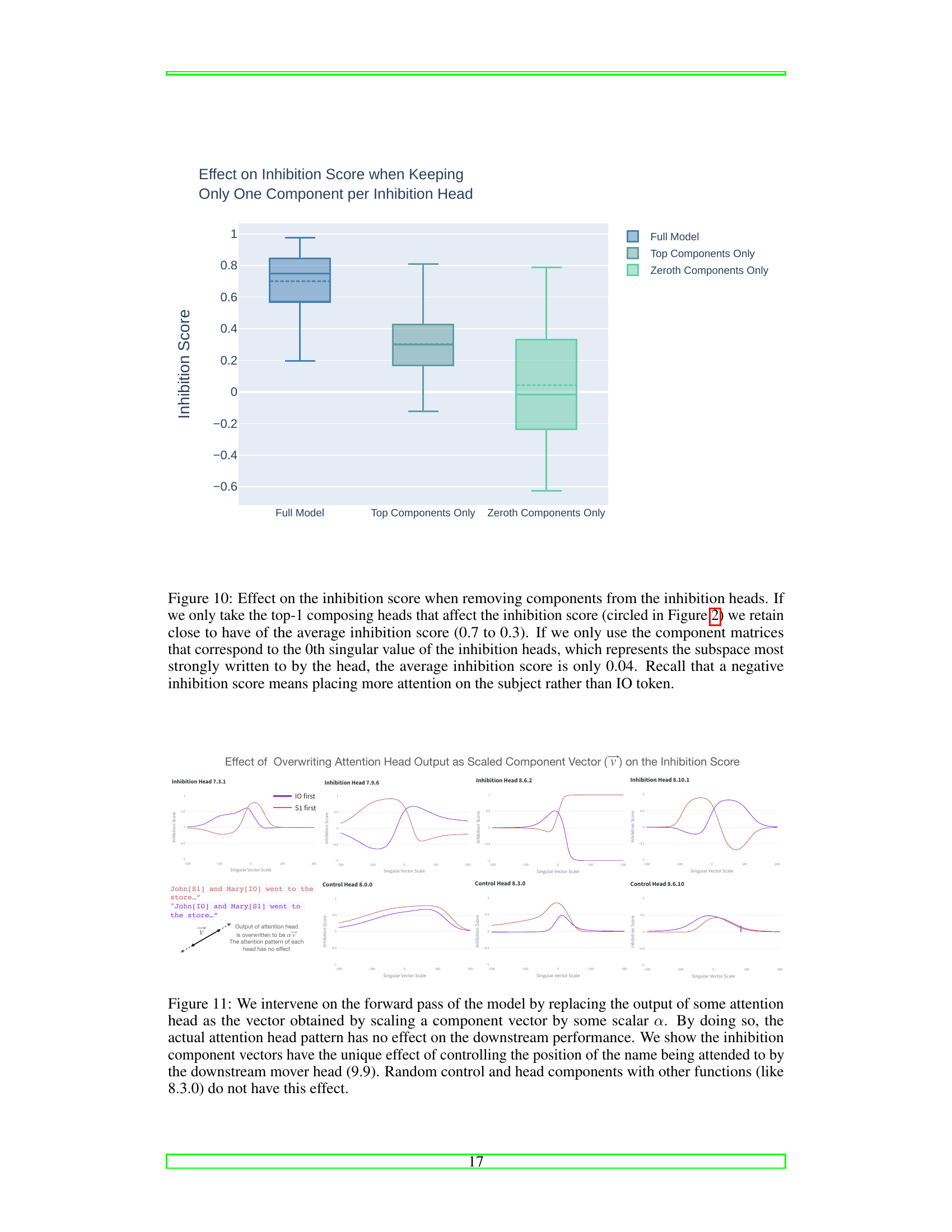

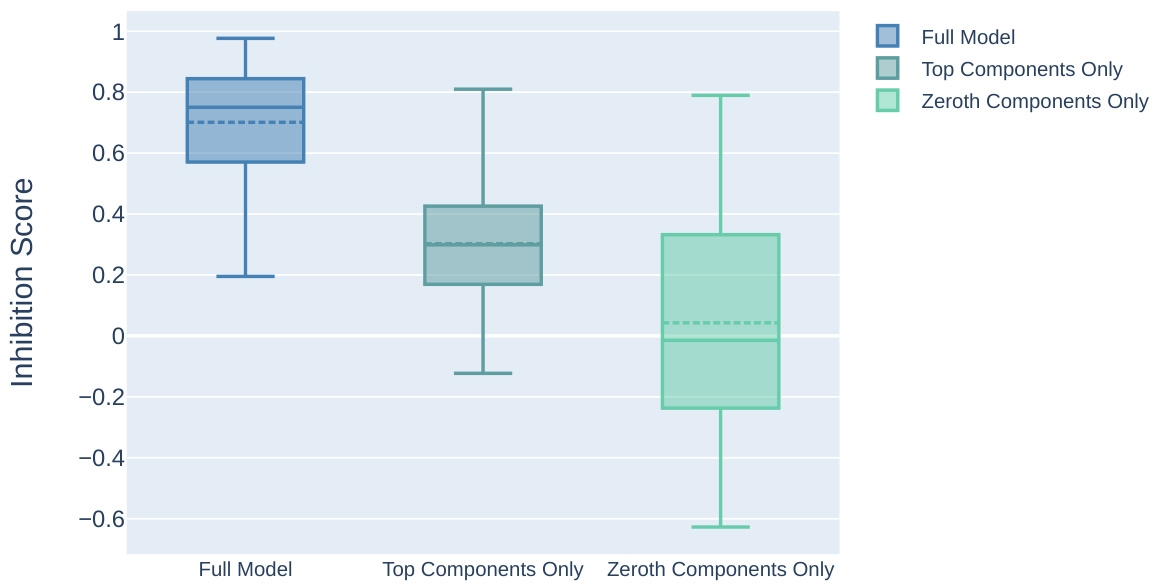

This figure shows the results of an experiment where components were removed from the inhibition heads of a language model, and the impact on the inhibition score was measured. The experiment shows that removing the top components reduces the inhibition score by roughly half, indicating their importance to the model’s behavior. Removing the lowest-ranked components, however, results in a significantly smaller effect, suggesting a low-rank structure in the inhibition mechanisms.

This figure shows how the rank-1 property of component matrices simplifies the analysis of their influence on model behavior. The left panel displays a PCA projection of inhibition component activations, illustrating their one-dimensional nature. The right panel demonstrates how scaling these activations (α) and incorporating them into the residual stream affects the model’s output. This manipulation allows for a controlled way to study the impact of individual components on model decisions, particularly in the context of the IOI task.

This figure shows two plots. The left plot shows how the accuracy of language models on a laundry list task decreases as the number of objects in the list increases. The right plot shows an example of how the order of objects in a prompt can affect the model’s ability to correctly answer a simple question. The figure highlights the sensitivity of language models to seemingly arbitrary changes in prompts and introduces the laundry list task that will be used in the paper to illustrate these problems.

The figure shows two plots. The left plot shows how the accuracy of language models decreases as the number of objects in a laundry list increases. The right plot shows an example of how changing the order of items in a laundry list can affect the model’s ability to correctly identify the item.

The figure shows two plots. The left plot shows how the accuracy of language models in a laundry list task decreases as the number of items in the list increases. The right plot shows an example of how changing the order of items in a prompt can significantly impact the model’s accuracy, even though the model should be able to access information from anywhere in the context. This demonstrates the arbitrary sensitivities of large language models (LLMs) to seemingly minor prompt variations.

This figure displays the relationship between weight-based composition scores and data-based inhibition scores for different inhibition heads communicating with a specific mover head (9.9) in the Indirect Object Identification (IOI) task. The graph shows that inhibition within each head is concentrated in one or two components. Removing those components significantly reduces the mover head’s ability to inhibit specific items. This suggests that communication channels are low-rank subspaces within the residual stream. The results support the use of the composition score when examining decomposed matrices for improved interpretability.

This figure shows composition scores for different types of head interactions: previous token to induction head (key), duplicate token to inhibition head (value), and inhibition to mover head (query). The figure demonstrates that some types of head interactions show clear signals in specific component matrices of the weight matrices (as revealed by Singular Value Decomposition), while others do not. This finding supports the authors’ focus on certain types of head interactions in their analysis.

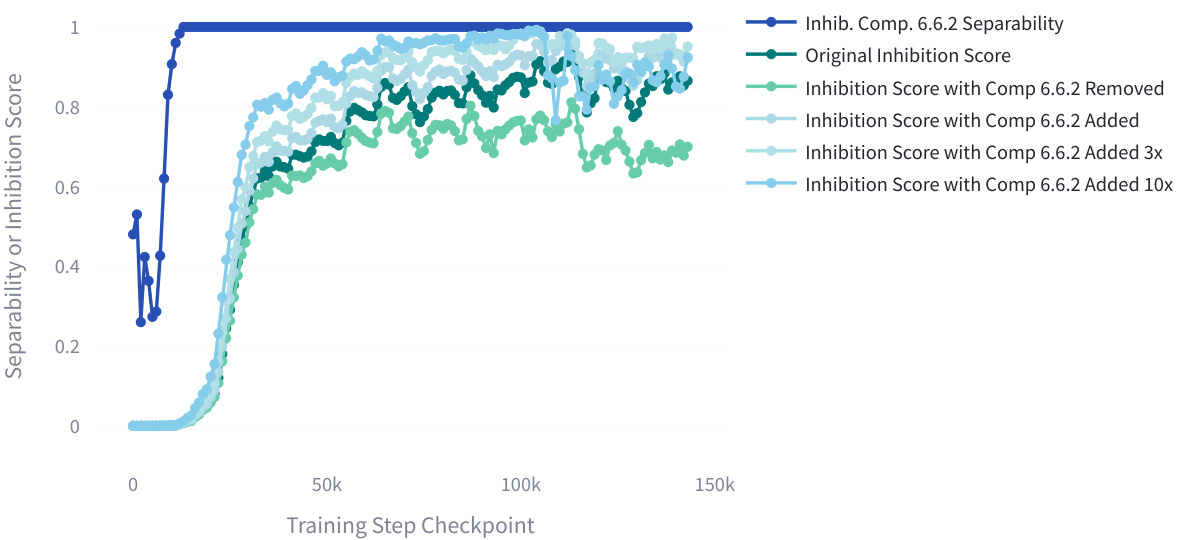

This figure shows the training progression of the inhibition component subspace and the mover head inhibition score in the Pythia model. It demonstrates the effect of adding or removing the inhibition component on the model’s ability to inhibit certain tokens. The separability metric indicates how well the model separates activations for minimal pairs based on the order of names, showing the impact of the inhibition component on the model’s performance.

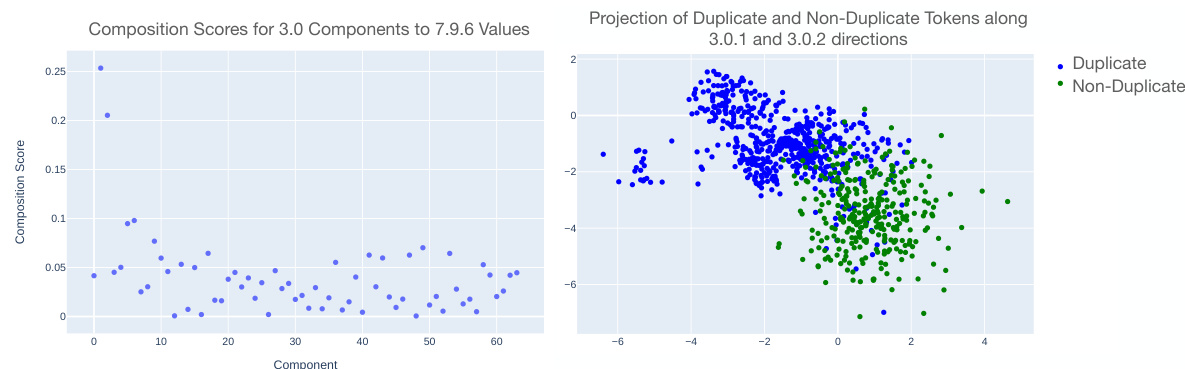

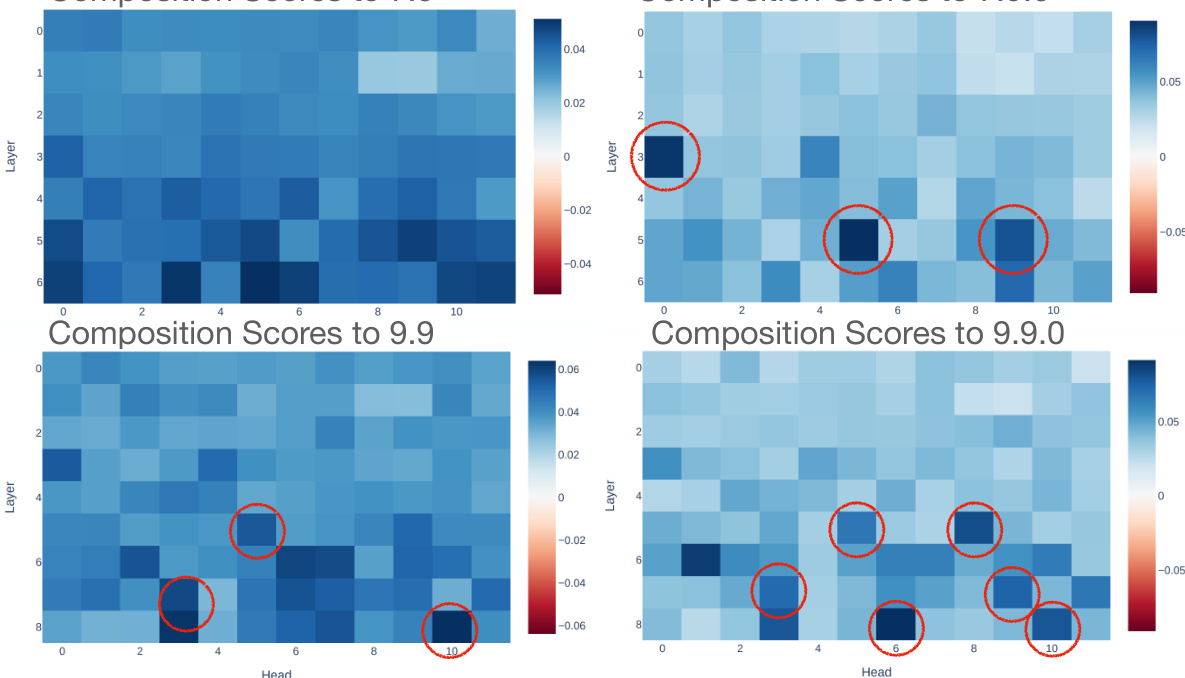

This figure shows the results of decomposing weight matrices to find communication channels between attention heads. The left side shows the noisy composition score without decomposition, while the right side shows the improved clarity after decomposition, highlighting in-circuit heads that communicate strongly.

This figure shows the results of decomposing weight matrices to find communication channels between attention heads. The left side shows the noisy composition scores without decomposition, while the right side shows the clearer results after decomposition, highlighting the in-circuit heads (circled in red). The decomposition helps isolate the communication channels within the model’s weights, allowing for identification of components belonging to the Indirect Object Identification (IOI) circuit without actually running the model.

This figure displays the correlation between weight-based composition scores and data-based inhibition scores for different inhibition heads connected to mover head 9.9 in the IOI task. The low-rank nature of inhibition within individual heads is highlighted, showing that removing a component leads to reduced mover head performance. This supports the use of composition scores when considering decomposed matrices.

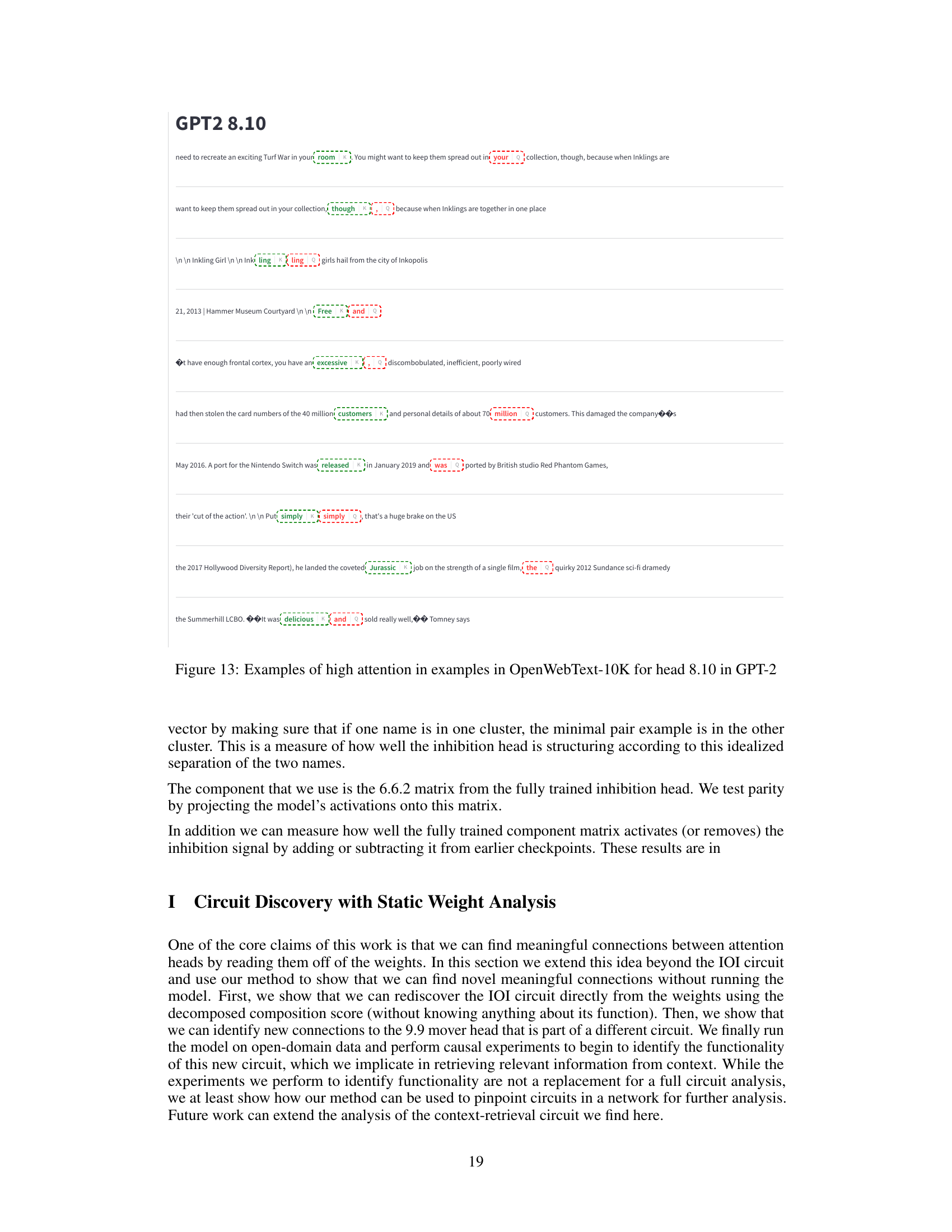

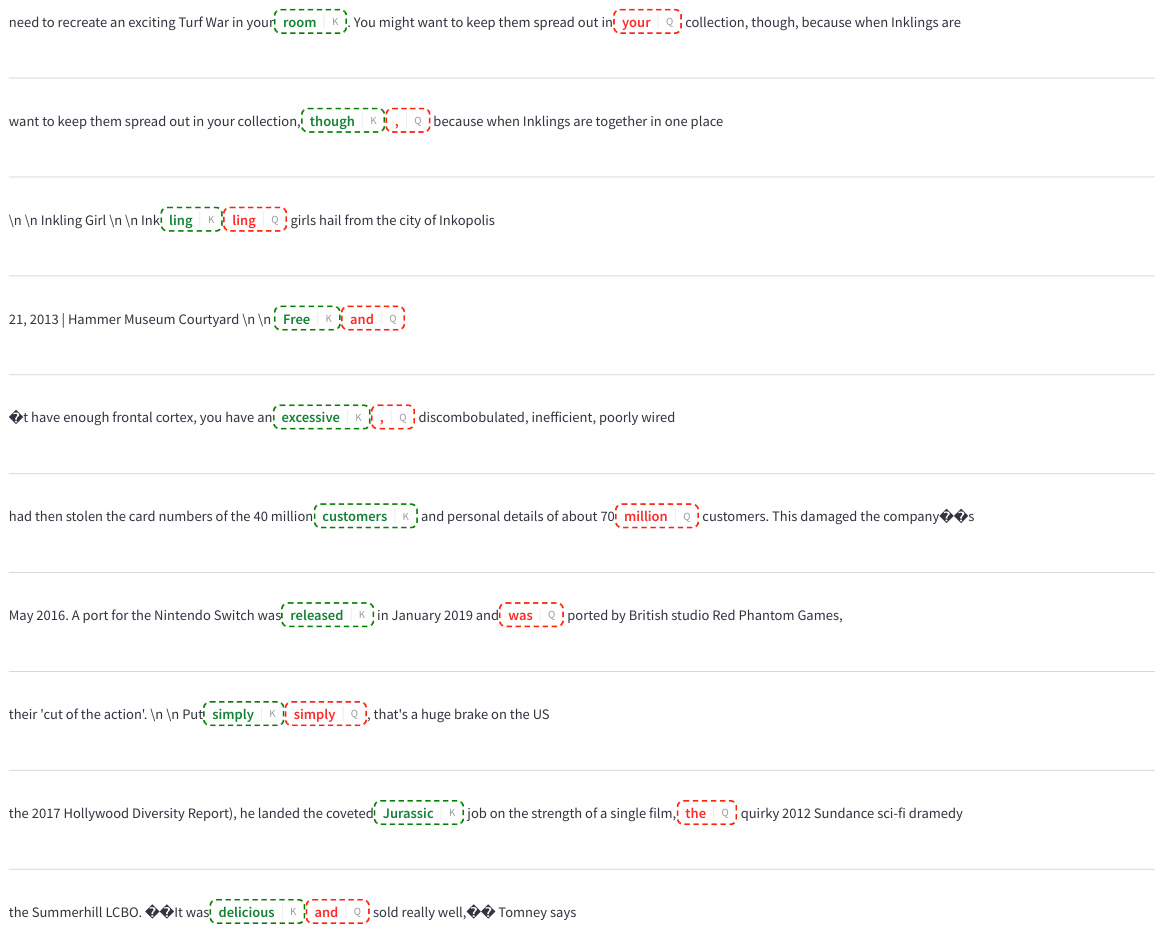

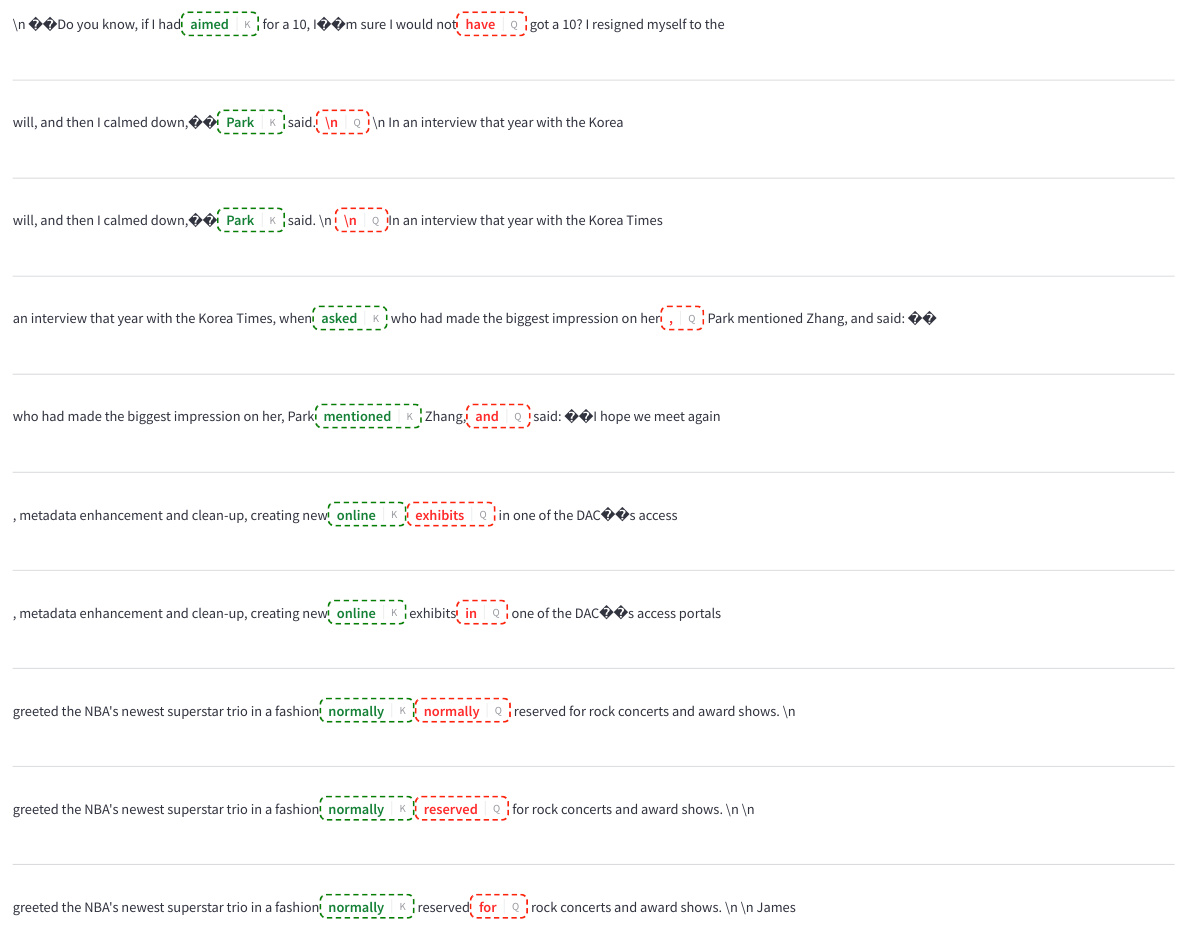

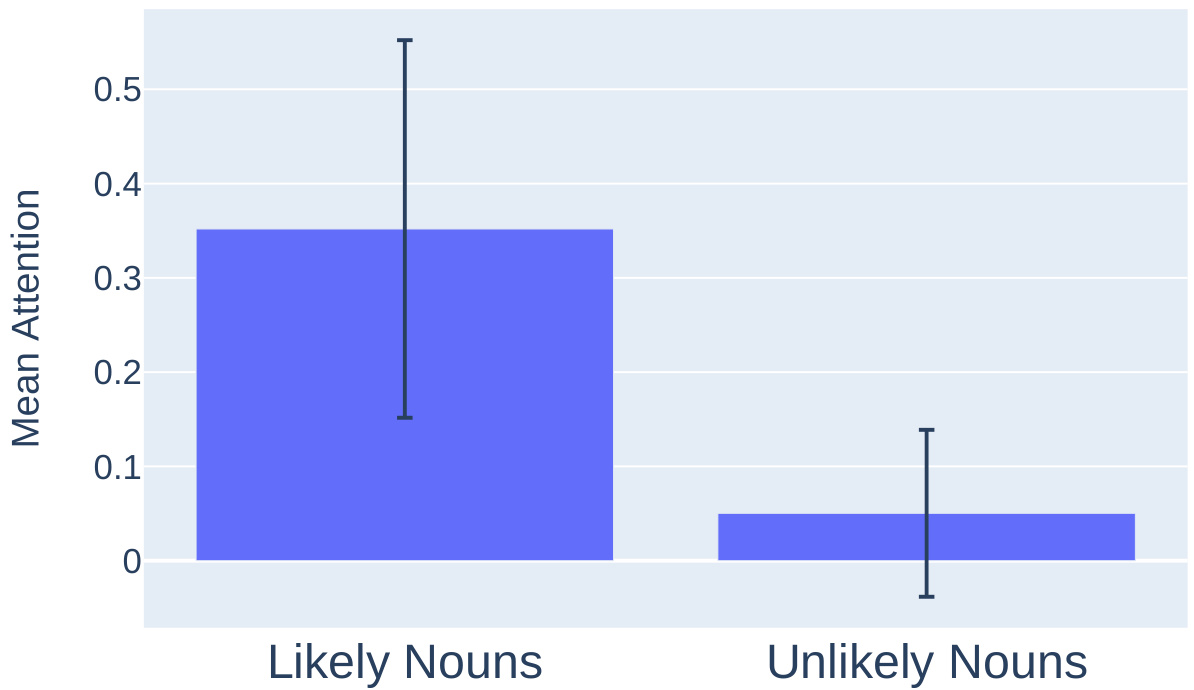

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to test the hypothesis that head 8.3 in GPT-2 attends to tokens that are logically appropriate continuations of the current context. The experiment used a synthetic dataset of verb-noun pairs, with some pairs being semantically consistent (likely nouns) and others not (unlikely nouns). The results show a statistically significant difference in the mean attention scores of head 8.3 for likely vs. unlikely nouns, supporting the hypothesis that head 8.3 plays a role in identifying semantically appropriate continuations.

This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to test the hypothesis that head 8.3 in GPT-2 is involved in selecting relevant continuations of the current context. The experiment used a synthetic dataset of verb-noun pairs, where the noun was either a likely or unlikely object of the verb. The figure displays the average attention score (probability mass assigned to a token) of head 8.3 to the noun in each condition. The results clearly indicate that head 8.3 attends much more strongly to nouns that are likely objects of the verb, providing further support for its role in contextual continuation.

This figure visualizes how the 3D inhibition subspace of a language model changes with increasing numbers of objects in a laundry list task. Each subplot represents a different number of objects, showing how the model allocates attention in its 3D inhibition subspace. The color of each point corresponds to which object the model attends to. As the number of objects increases, the subspace becomes more densely packed, leading to a breakdown of the clear structure for higher object counts.

This figure shows how the 1D inhibition components and 2D duplicate token components precisely control which name is avoided by the mover head. By scaling a vector in the output space of an inhibition component, either the first or second name can be selectively inhibited. Similarly, adding or removing duplicate token information from the duplicate channel also affects which name is inhibited. The experiment demonstrates that only these specific components have this causal effect on the model’s behavior.

This figure visualizes how the model’s 3D inhibition subspace handles an increasing number of objects in a laundry list task. Each point represents a model’s attention to a specific object. As more items are added, the space becomes more crowded, impacting the model’s ability to accurately index and retrieve the correct information, especially from the middle of the list. The structure is surprisingly neat, except for a few instances where artifacts appear.

This figure shows the effect of scaling different combinations of inhibition components on the mover head’s attention to different items in the laundry list task. The left panel shows that scaling a single component isn’t sufficient for large lists. The middle panel reveals that scaling three components creates a structured space where different regions correspond to different item positions, but this structure degrades with larger list sizes. The right panel presents the accuracy improvement resulting from sampling from this inhibition space, demonstrating that this intervention greatly helps for longer lists while showing a capacity limit.

This figure visualizes how the model’s 3D inhibition subspace handles an increasing number of objects in the laundry list task. Each sub-figure represents a different number of objects. As more objects are added, the model allocates more space within the 3D subspace to represent them. However, this representation capacity has limits; the middle objects become crowded together in the space, which negatively affects the model’s performance in the task.

This figure shows the results of manipulating the inhibition components. The left panel shows that manipulating a single inhibition component doesn’t allow for selecting specific objects, while manipulating three components (middle) creates a surprisingly well-organized structure in the attention space. However, this structure degrades with more items. The right panel shows the accuracy increase achieved by randomly sampling within the inhibition space. The improvement is substantial for smaller lists but plateaus with larger ones because the model’s ability to index the items in the list is capacity-limited.

This figure shows the results of experiments manipulating the inhibition channel to improve the model’s ability to recall items from a list (Laundry List Task). The left and middle panels show that interventions on the inhibition channel allow for finer-grained control over which item the model attends to, but this ability degrades as the list length increases. The right panel shows that manipulating this channel leads to significant accuracy improvements in recalling items from the list, especially when the number of items is small to moderate.

This figure shows the effect of manipulating the inhibition components on the mover head’s attention and the model’s accuracy on the Laundry List task. The left panel shows that scaling a single inhibition component is insufficient to control attention to specific objects in the list. The middle panel demonstrates that scaling a combination of three inhibition components allows for fine-grained control over which object is attended to, revealing an intricate structure in the model’s representation of list items. However, this structure breaks down as the list length increases, demonstrating a capacity limit of the inhibition mechanism. The right panel illustrates the improvement in task accuracy achieved by strategically sampling from the inhibition space.

This figure visualizes how the three-dimensional inhibition subspace in a language model handles an increasing number of objects in a laundry list task. Each sub-figure represents a different number of objects (3-10 and 20). The colors indicate which object the model is primarily focusing on. The plot shows that as the number of objects increases, the model’s attention to the objects gets increasingly compressed and less structured, especially in the middle range of objects, potentially indicating a capacity limitation in this mechanism.

This figure visualizes how scaling inhibition components affects the mover head’s attention and model accuracy in a laundry list task. The left panel shows that scaling a single inhibition component is insufficient for precise object selection. The middle panel demonstrates that scaling three inhibition components reveals a structured representation space where attention is partitioned by object index; this structure degrades with a larger number of objects. The right panel displays accuracy improvements resulting from sampling within the inhibition space, showing enhanced performance but limited capacity.

Full paper#