↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many studies have explored adversarial attacks to evade pedestrian detectors, but existing methods often fail at medium to long distances due to an appearance gap between simulated and physical-world scenarios, and conflicts in adversarial losses at different ranges. This paper highlights this gap and conflict as major challenges.

To address these issues, the authors propose a novel method called Full Distance Attack (FDA), which utilizes a Distant Image Converter (DIC) to accurately simulate the appearance of distant objects and incorporates a Multi-Frequency Optimization (MFO) technique to resolve conflicts between adversarial losses at different distances. Physical-world experiments demonstrated FDA’s effectiveness across multiple detection models, improving the robustness of adversarial attacks against pedestrian detectors in real-world scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical limitation of existing adversarial attack methods against pedestrian detectors: their ineffectiveness at longer distances. By introducing a novel Full Distance Attack (FDA), it opens avenues for more robust and realistic adversarial attacks, impacting the development of more secure and reliable computer vision systems. The proposed distant image converter (DIC) and multi-frequency optimization (MFO) techniques are valuable contributions to the field, pushing the boundaries of adversarial attacks and urging further research on improving the robustness of object detection models.

Visual Insights#

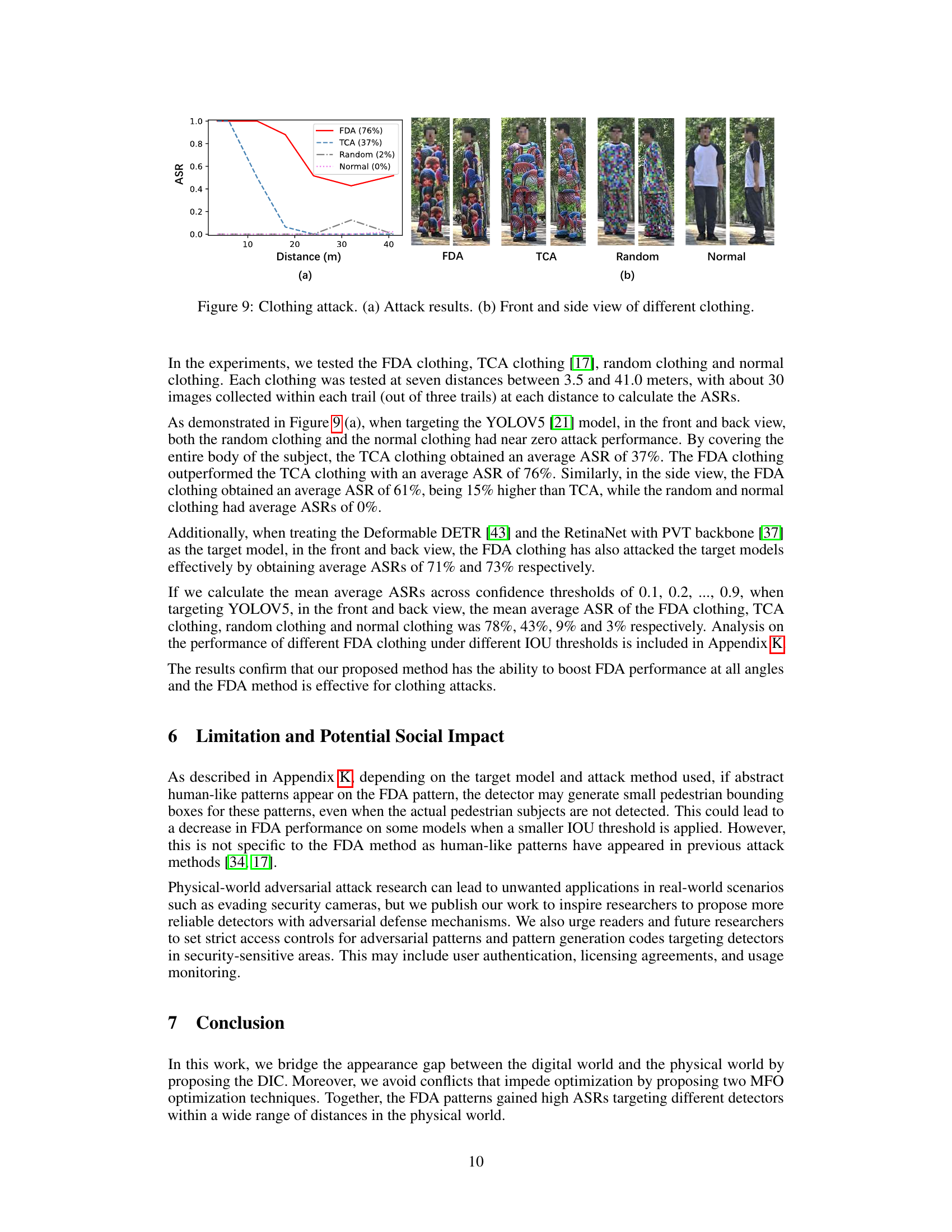

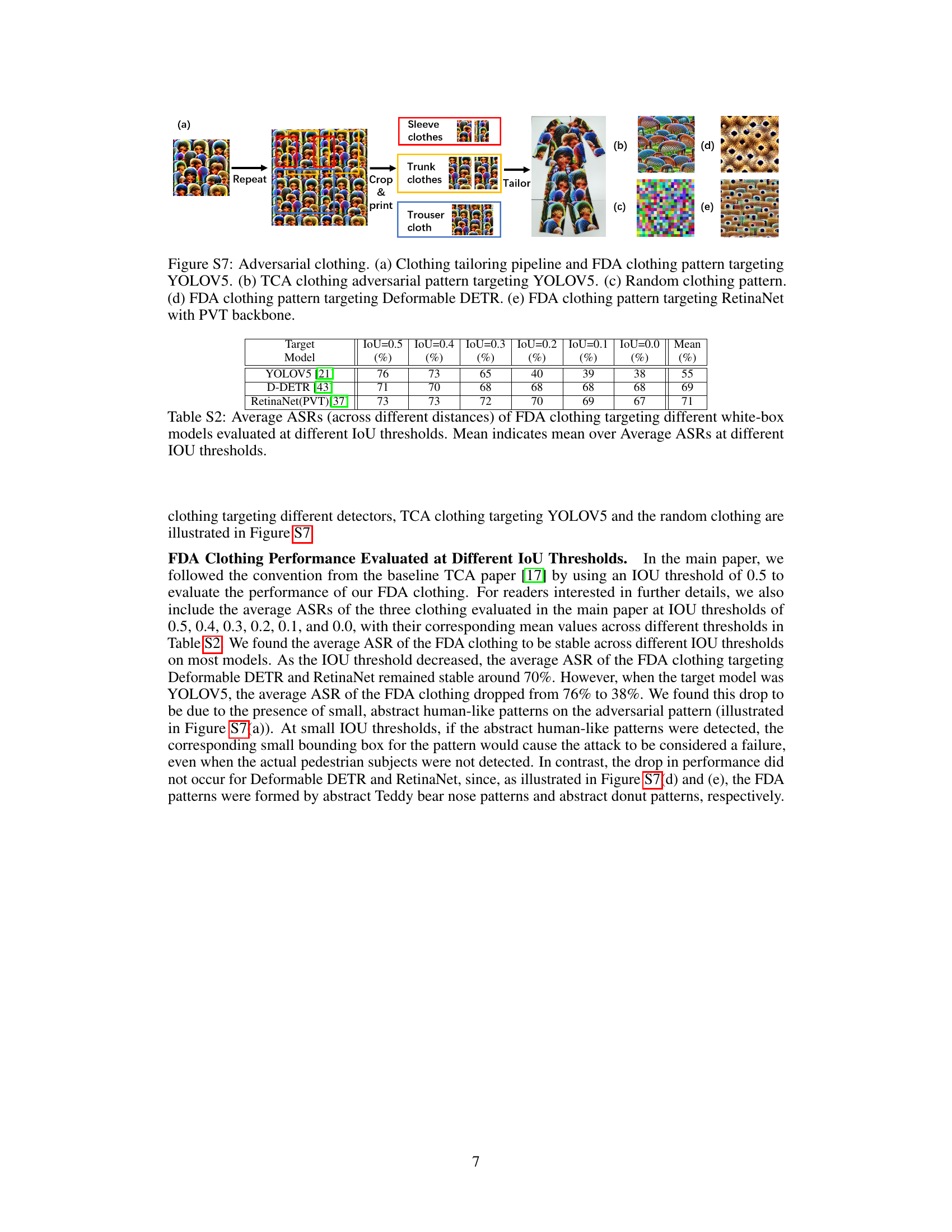

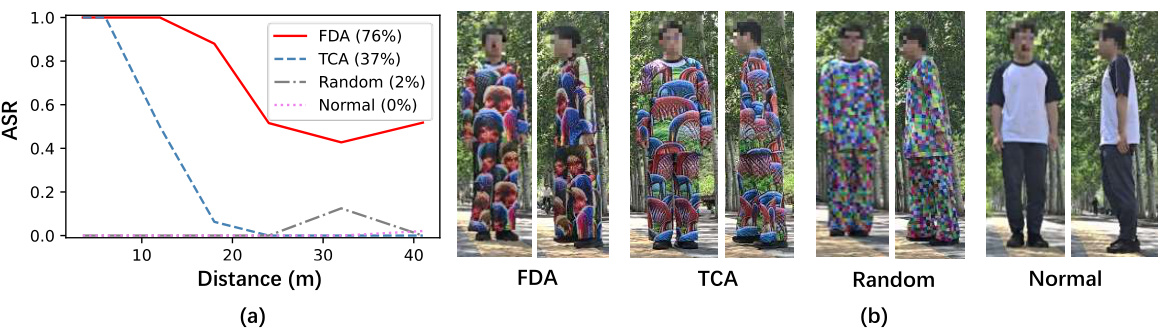

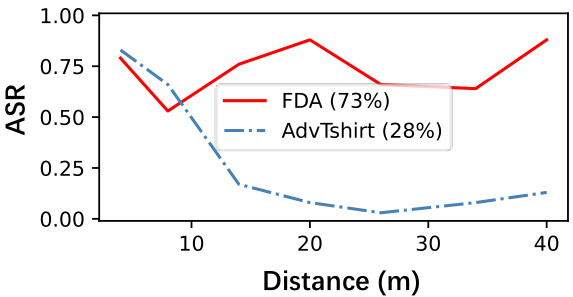

This figure compares the performance of a baseline adversarial attack method and the proposed Full Distance Attack (FDA) method across different distances. Subfigure (a) shows that the FDA method is significantly more effective at evading pedestrian detectors at medium and long distances. Subfigure (b) illustrates the main challenge in creating effective physical world adversarial attacks, the appearance gap between simulated and real-world adversarial patterns at different distances. The naive simulation method of simply resizing the adversarial pattern fails to accurately represent the appearance of the pattern at longer distances, leading to ineffective attacks.

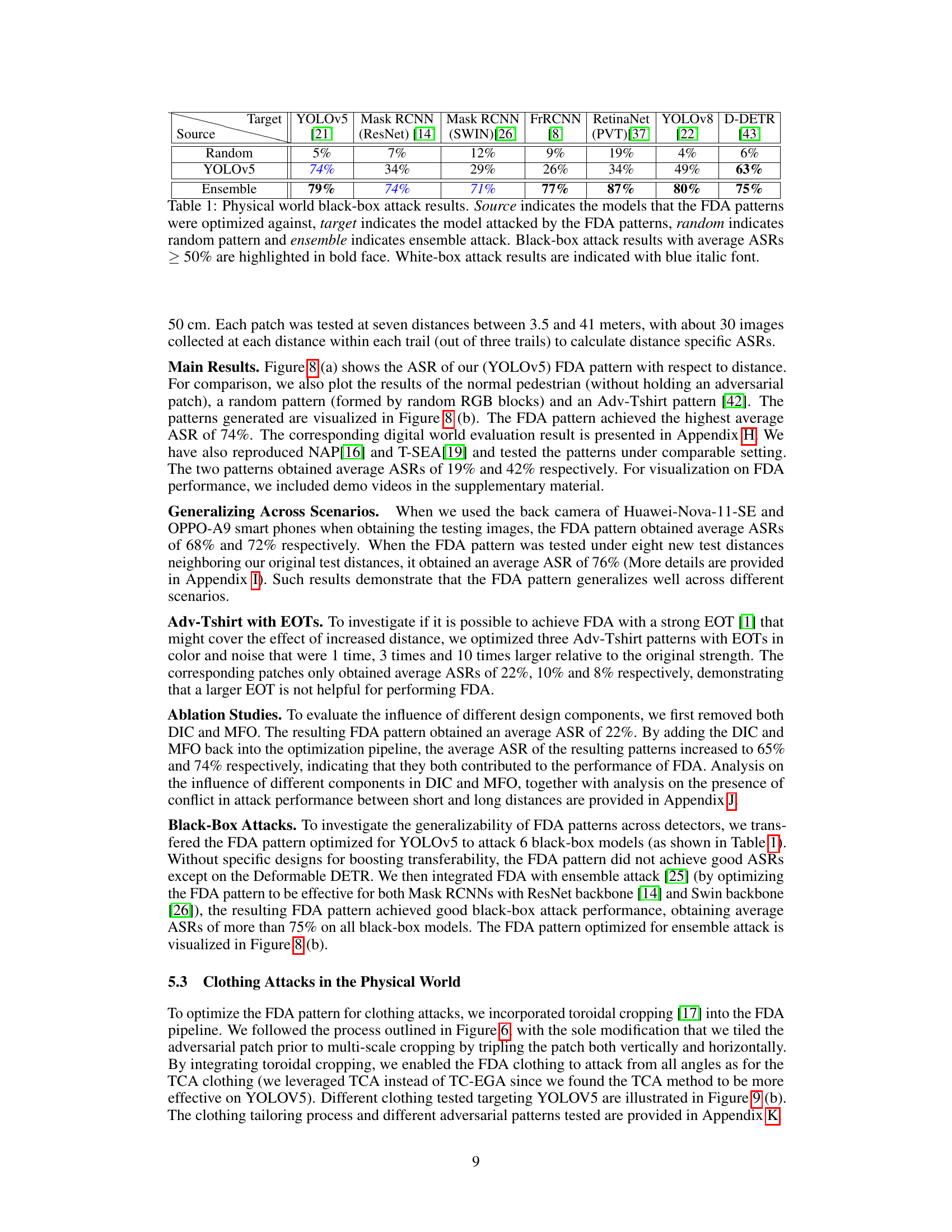

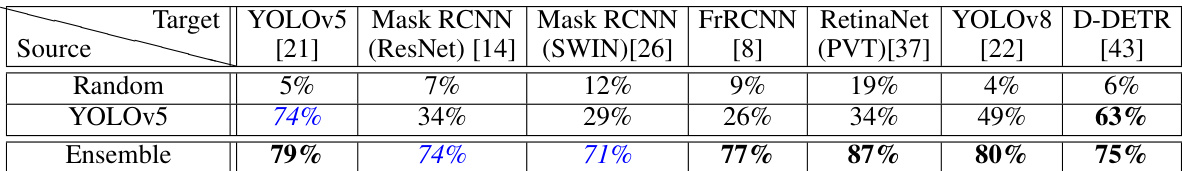

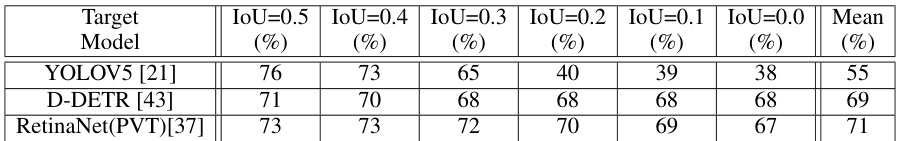

This table presents the results of black-box adversarial attacks on several pedestrian detection models. The FDA (Full Distance Attack) patterns were trained against various source models (YOLOv5, Mask RCNN with ResNet and Swin backbones, Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet with PVT backbone). The table shows the average attack success rate (ASR) achieved when these trained patterns were used to attack each target model. A random pattern and an ensemble attack (combining patterns from multiple sources) are also included for comparison. Higher ASRs indicate more successful evasion.

In-depth insights#

Distant Adversary#

The concept of a ‘Distant Adversary’ in the context of adversarial attacks against computer vision systems is crucial. It highlights the challenge of creating adversarial perturbations that remain effective at longer distances from the camera. This is significantly harder than crafting attacks for close-range images because factors like atmospheric perspective, camera blurring (anti-aliasing filters and imaging chip limitations), and digital camera effects all distort the appearance of the adversarial pattern. Successfully addressing the distant adversary problem necessitates advanced image simulation techniques during the optimization process to accurately model how the adversary’s appearance degrades with distance. This could involve integrating a physics-based model of the image formation pipeline and atmospheric effects. Further, the optimization strategy itself would need to be robust to the appearance inconsistencies introduced by the distance. Techniques such as multi-frequency optimization might be beneficial to tackle this problem, as different frequency components of the pattern may have different effects at various ranges. Real-world physical experiments are critical to validate the effectiveness of any proposed solution. The overall success hinges on bridging the gap between simulated and real-world conditions to ensure that the optimized adversarial pattern effectively degrades in appearance in a way that still successfully fools the target deep neural network.

DIC for Physical#

A hypothetical section titled “DIC for Physical” within a research paper on adversarial attacks against pedestrian detection systems would likely detail the process of translating digitally generated adversarial patterns into the physical world. This is crucial because adversarial examples optimized in simulation often fail to transfer effectively to real-world scenarios due to differences in lighting, camera properties, and atmospheric conditions. The core of this section would revolve around bridging the “reality gap”, outlining the specific techniques and considerations for printing, applying, and deploying the adversarial patches. Accurate color reproduction would be paramount, as subtle color shifts can drastically impact the effectiveness of the attack. Additionally, the section would explore the influence of various physical factors, such as atmospheric perspective (e.g., haze, fog), camera optics (blur, noise, etc.), and the texture and material of the patch itself, on the visual appearance and ultimate effectiveness of the adversarial pattern in real-world settings. The authors would likely present experimental results demonstrating the effectiveness of their chosen DIC methods in generating physically realistic adversarial patterns. Finally, a discussion of the limitations of the DIC method and potential avenues for improvement would provide valuable insight.

Multi-Frequency Opt#

The concept of “Multi-Frequency Optimization” in adversarial patch generation for evading pedestrian detectors addresses a critical challenge: the conflict between optimal adversarial patterns at near and far distances. At short ranges, high-resolution images allow for both high and low-frequency details to be effectively manipulated to fool the detector. However, at longer distances, image resolution decreases, rendering high-frequency details ineffective. A naive approach of simply downscaling adversarial patterns optimized for short distances fails because the visual appearance differs significantly from what the camera actually captures at a distance. Therefore, Multi-Frequency Optimization aims to generate patterns that are effective across a wide range of distances by specifically optimizing for different frequency components at different ranges. This is likely accomplished via a multi-stage or multi-loss function approach. For instance, a method might prioritize low-frequency components in the initial stages of optimization, focusing on the appearance at longer distances and then progressively incorporate higher-frequency components to refine performance at closer ranges. This technique is crucial to bridging the gap between simulated and real-world adversarial attacks, making physical attacks more robust and reliable.

Physical Attacks#

The concept of “Physical Attacks” in the context of adversarial machine learning focuses on the real-world effectiveness of attacks crafted in a digital space. It investigates whether adversarial examples, designed to fool AI models digitally, maintain their effectiveness when manifested physically. A key challenge lies in bridging the “reality gap”: the differences in appearance and environmental factors between simulated and actual physical conditions. Successful physical attacks demonstrate vulnerabilities beyond the digital realm, highlighting the importance of robustness in real-world AI systems. Furthermore, the research into physical attacks uncovers limitations of existing attack methods, revealing the need for more sophisticated techniques that account for the complexities of the physical world, such as lighting conditions, viewing angles and atmospheric effects. Developing effective physical attacks requires a multi-faceted approach involving careful image synthesis, printing techniques, and rigorous evaluation under varied conditions. The success of these attacks emphasizes the necessity for developing more robust AI models that are resilient to real-world adversarial manipulations.

FDA Generalization#

FDA generalization in the context of adversarial attacks against pedestrian detectors examines the ability of a generated adversarial pattern to maintain its effectiveness across various conditions. Successful generalization means the attack remains potent even with changes in distance, lighting, viewing angles, or the specific detector model. A well-generalized attack is more robust and less prone to failure in real-world scenarios. The paper likely investigates this robustness through extensive testing across diverse environments and models, measuring the success rate of the attack under various conditions. Factors influencing generalization might include the frequency components of the adversarial pattern and how these interact with the inherent properties of the image formation and camera systems. The study may also explore techniques to enhance generalization, perhaps through methods that incorporate multi-scale features or utilize more sophisticated optimization strategies during adversarial pattern generation. Ultimately, the success of FDA generalization greatly impacts the practical viability of adversarial attacks, moving beyond carefully controlled settings to the more challenging uncertainties of the real world.

More visual insights#

More on figures

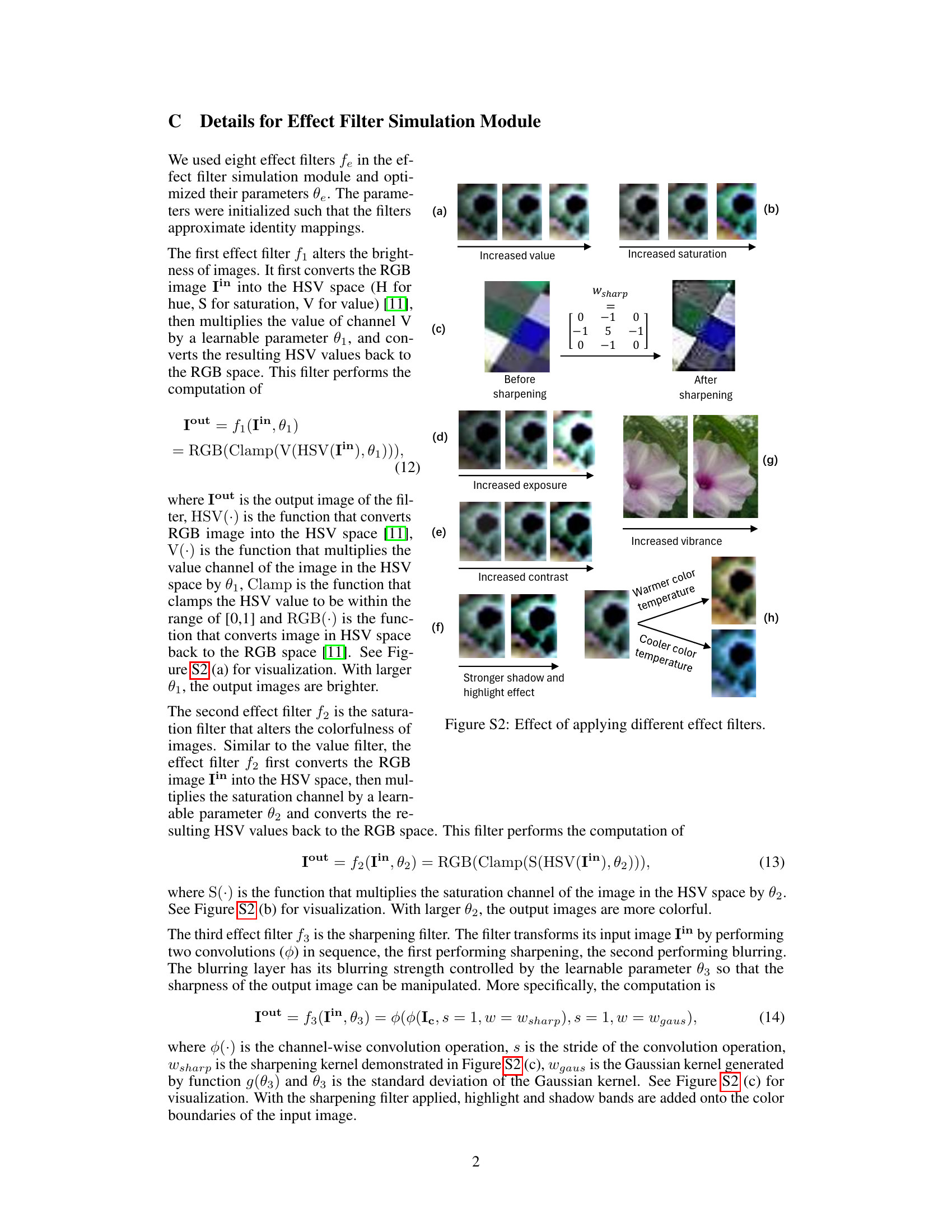

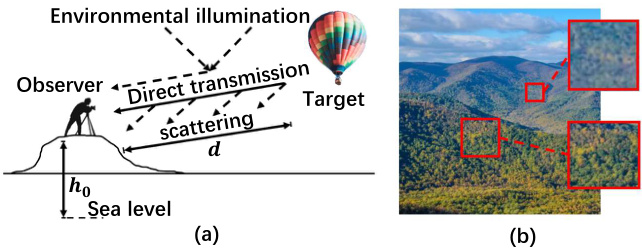

This figure illustrates the concept of atmospheric perspective, a phenomenon where the color of objects appears to shift toward the color of the sky as distance increases due to light scattering by air molecules, dust, and moisture. Panel (a) is a diagram showing the paths of light from a target object to an observer, including direct transmission and scattering. Panel (b) shows a real-world example of this effect in a landscape photograph, with distant trees appearing more bluish than nearer trees.

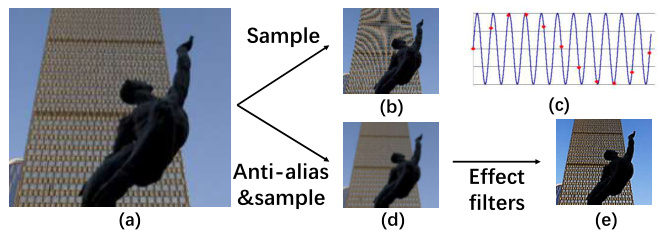

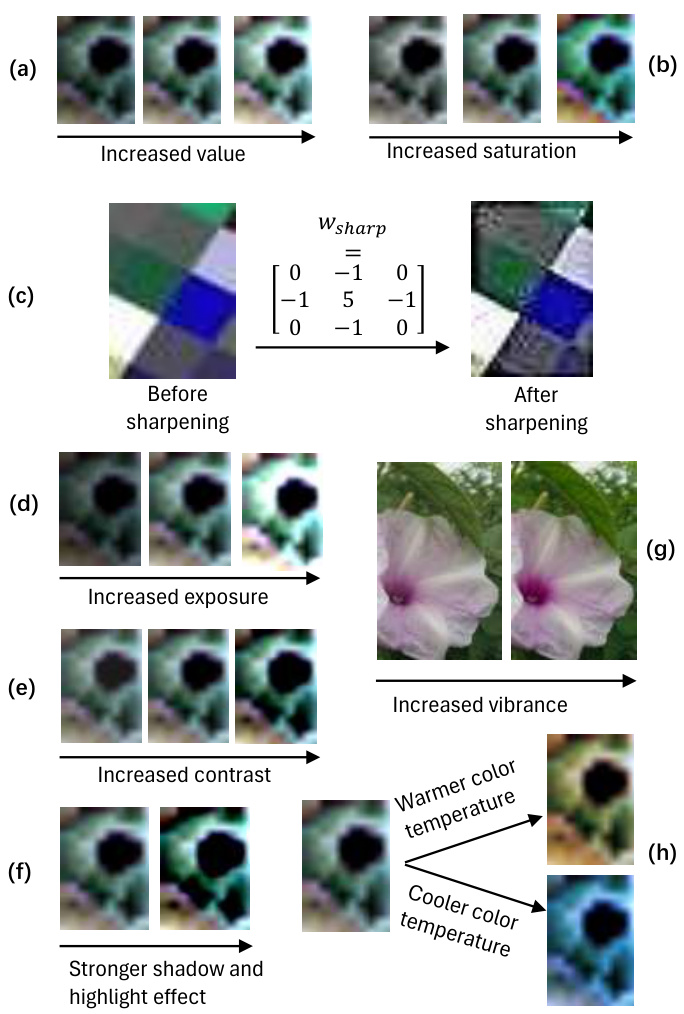

This figure illustrates the factors influencing the final image obtained by a camera. (a) shows the original light field. (b) shows aliasing effects caused by naive sampling of the light field. (c) provides a 1D illustration of aliasing. (d) demonstrates the effect of applying an anti-aliasing filter before sampling, which mitigates aliasing. Finally, (e) shows the effect of applying additional filters, such as sharpening and contrast, after capturing the image.

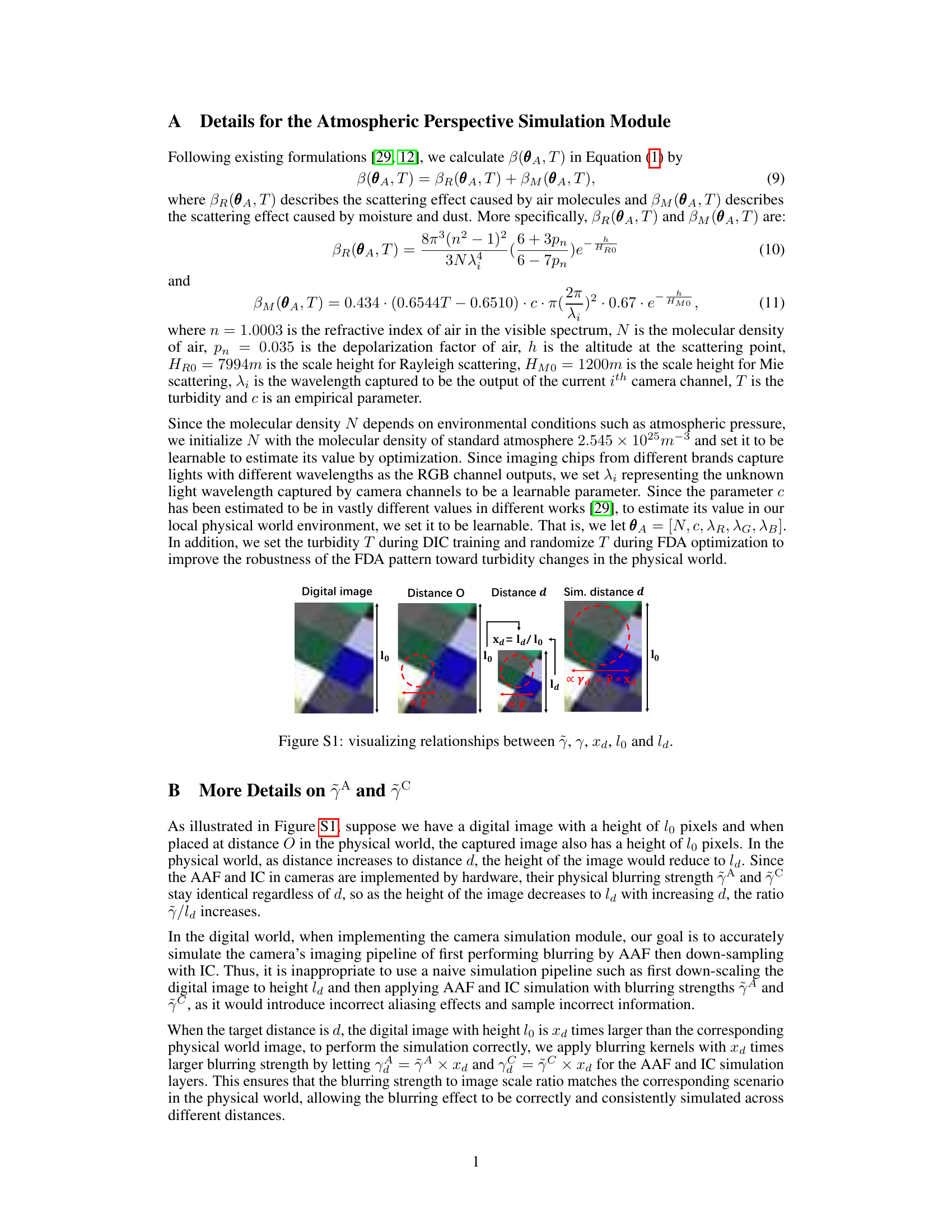

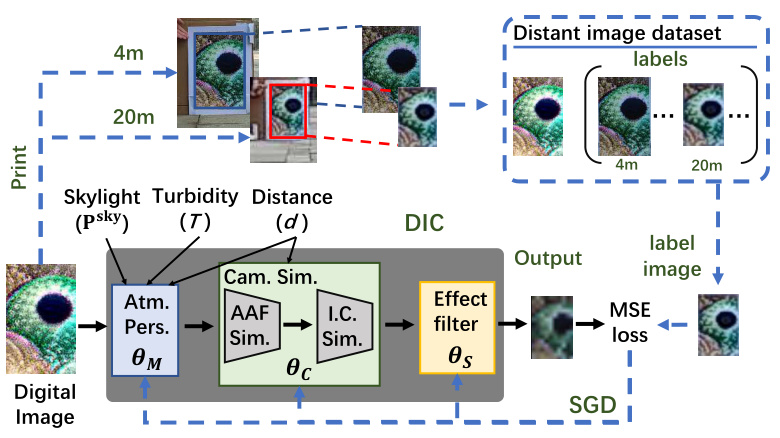

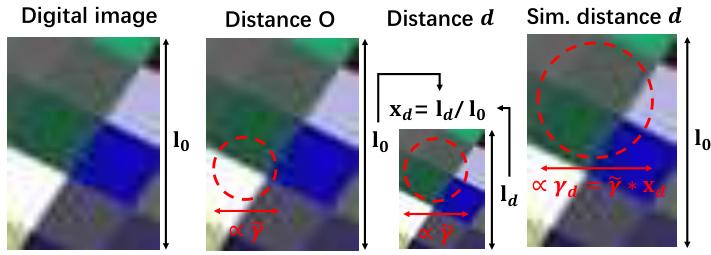

This figure illustrates the Distant Image Converter (DIC) pipeline. The DIC takes as input a digital image of a pedestrian at a short distance, along with environmental parameters such as skylight color, turbidity, and the target distance. It simulates the effects of atmospheric perspective, camera blurring (from anti-aliasing filter and image chip), and digital effect filters. The output is a simulated image of the same pedestrian appearing as if it were taken from the specified target distance. This simulated image bridges the appearance gap between digital images and their physical-world counterparts, enhancing the effectiveness of adversarial patterns for evasion at various distances.

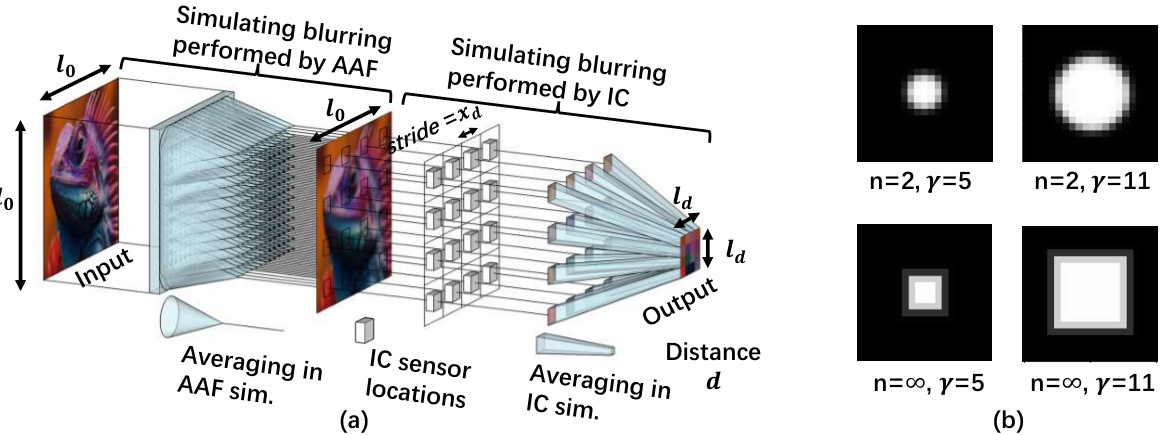

This figure illustrates the camera simulation module of the Distant Image Converter (DIC). Panel (a) shows a 3D schematic of the process. The input image is first blurred by an anti-aliasing filter (AAF) simulation layer, then down-sampled by an imaging chip (IC) simulation layer. The blurring is achieved through convolutional layers with kernels designed to mimic the averaging effects of the AAF and IC sensors at different distances. Panel (b) shows example kernel outputs (function f) with different parameters (n and γ), illustrating how these parameters control the spatial extent and shape of the blurring.

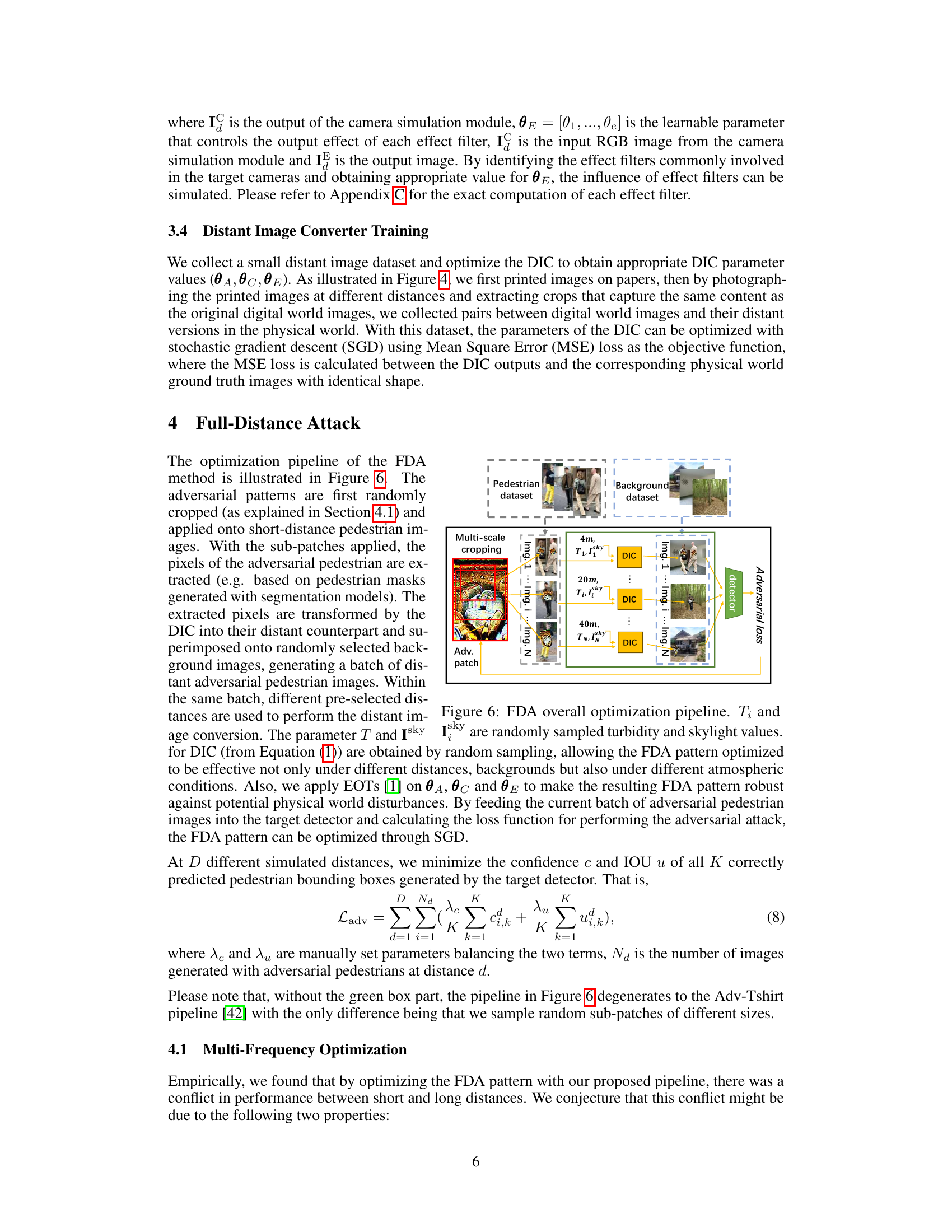

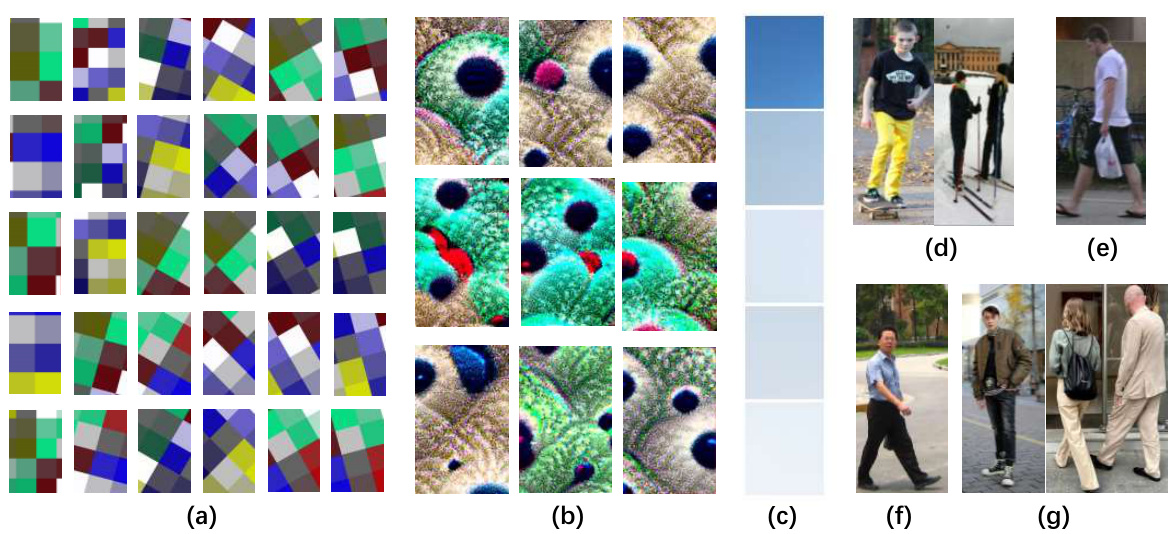

The figure illustrates the optimization pipeline of the Full-Distance Attack (FDA) method. It begins with randomly cropped adversarial patterns applied to short-distance pedestrian images. These patterns are then extracted (using pedestrian masks) and processed by the Distant Image Converter (DIC) at multiple simulated distances (4m, 20m, 40m), simulating the appearance changes with distance. The processed patterns are superimposed onto randomly selected background images to create a batch of distant adversarial pedestrian images. Different turbidity (T) and skylight (Isky) values are randomly sampled for each distance to increase robustness. This batch of images is fed to the target detector, and the adversarial loss is calculated. Through Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), the FDA pattern is optimized to effectively evade pedestrian detection across various distances.

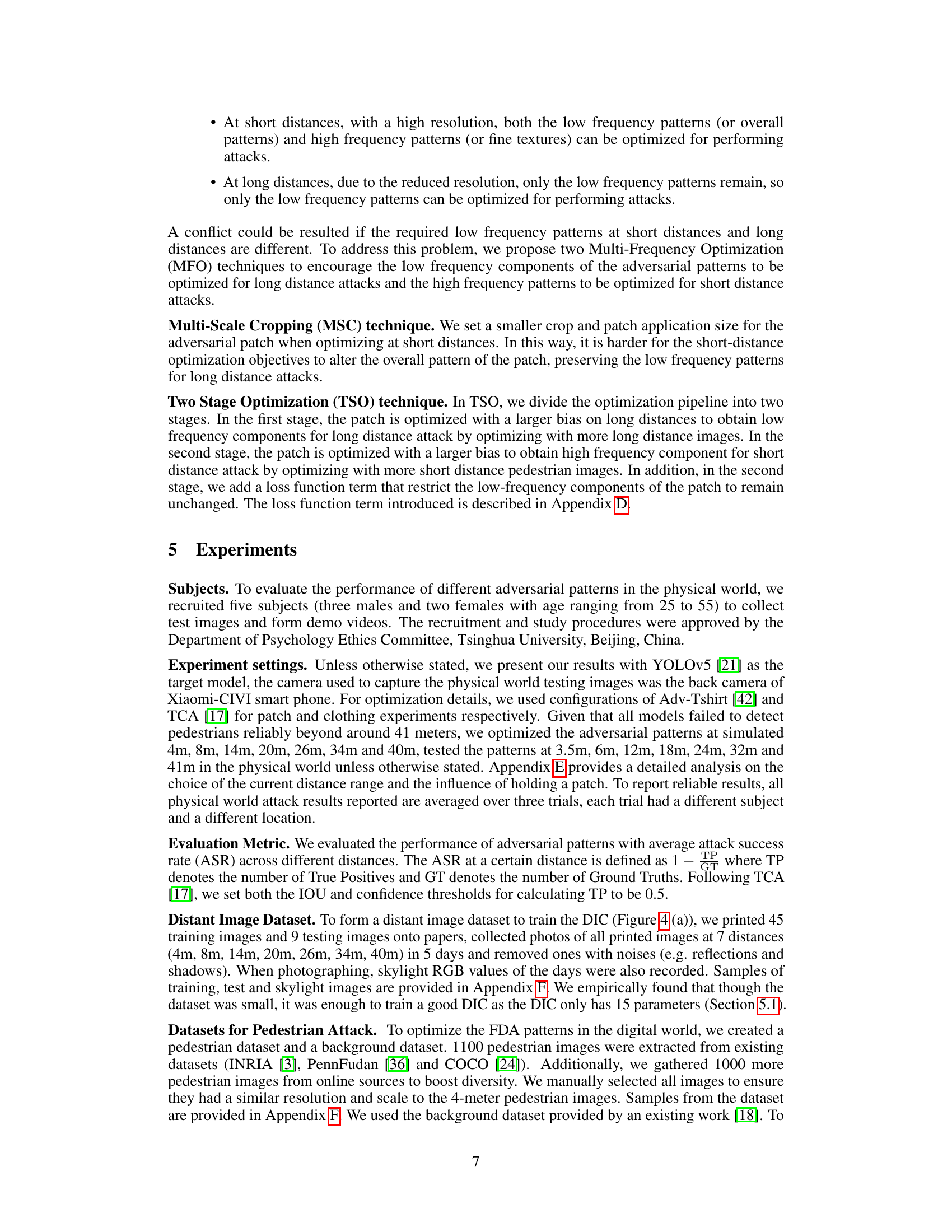

This figure shows the performance comparison of different distant image conversion methods on a test dataset. The left panel (a) presents a graph illustrating the L2 norm error of each method across varying distances. The right panel (b) provides a visual comparison of the output images generated by each method at three different distances, contrasted against the actual real-world image. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed Distant Image Converter (DIC) in accurately simulating the appearance of distant objects compared to naive methods like simple resizing and more sophisticated methods like fully convolutional networks.

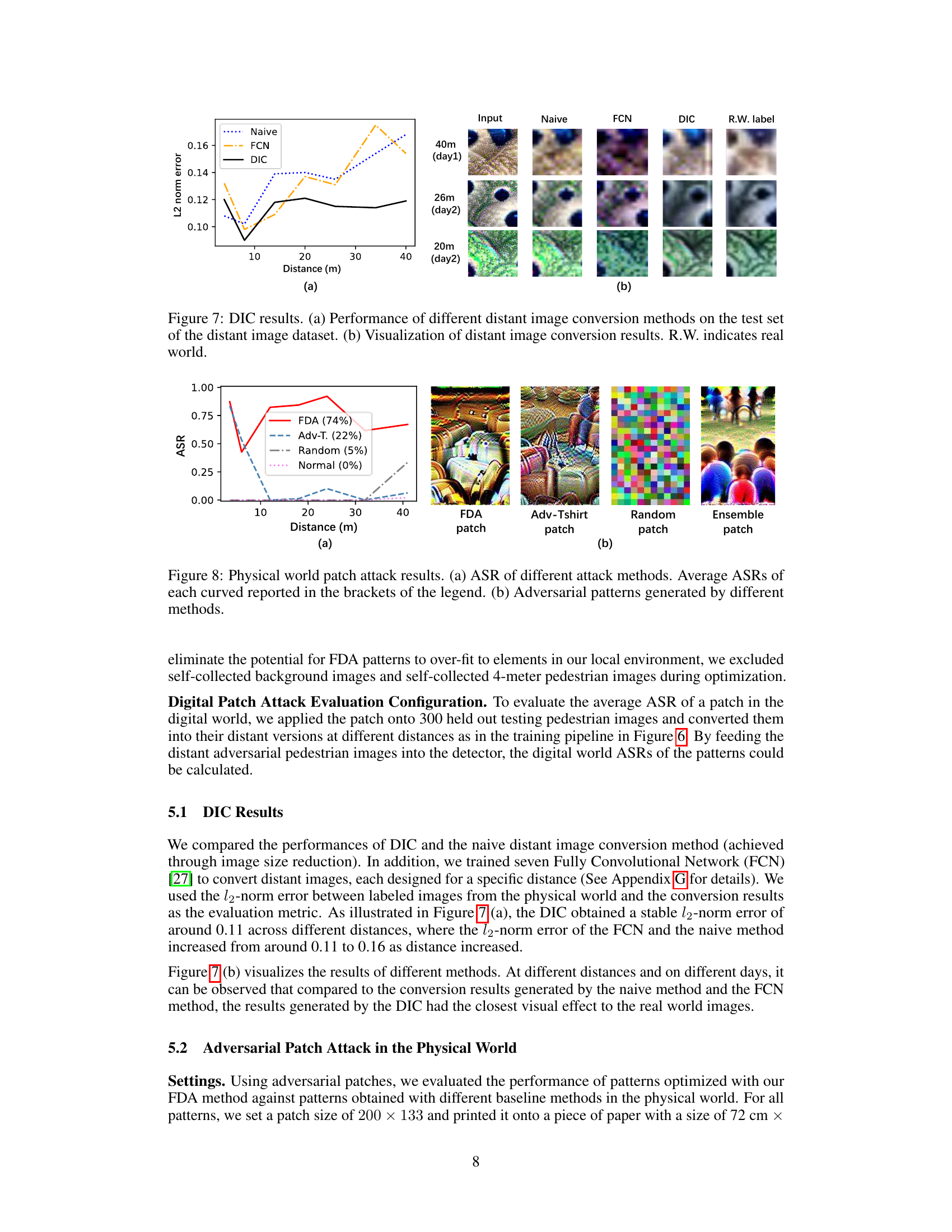

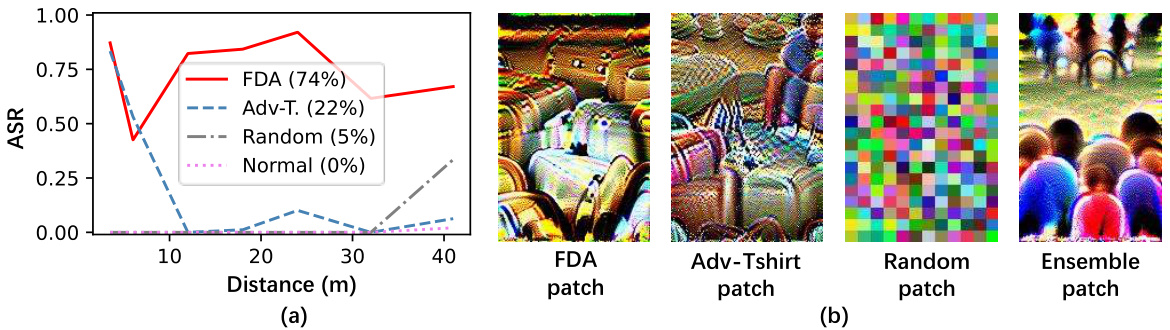

This figure shows the results of a physical world patch attack experiment. The left panel (a) is a graph showing the average success rate (ASR) of different attack methods (FDA, Adv-Tshirt, Random, Normal) across different distances. The right panel (b) shows the adversarial patterns generated by each method. The FDA method achieves the highest ASR at all distances, indicating its effectiveness in evading pedestrian detectors even at longer distances. Adv-Tshirt shows some effectiveness at shorter distances, while random and normal patterns are ineffective.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of different adversarial attack methods in the physical world. Subfigure (a) shows a graph comparing the average attack success rate (ASR) across various distances for four methods: FDA, Adv-Tshirt, Random Patch, and Normal (no patch). FDA shows significantly higher ASR across all distances. Subfigure (b) displays the adversarial patterns used for each method, visually illustrating their differences and how they might affect detection.

This figure illustrates the camera simulation module used in the Distant Image Converter (DIC). Panel (a) shows how the module simulates the blurring effects of the anti-aliasing filter (AAF) and imaging chip (IC) within a camera. It uses two convolutional layers to achieve this blurring. Panel (b) displays the results of the kernel generation function ‘f’ used to create the convolutional kernels. The function generates different kernels depending on its parameters, simulating how the blurring changes with different distances and camera characteristics.

This figure illustrates the factors that influence the image effect during the image formation process in a digital camera. It shows how aliasing can occur when the camera’s sensor naively samples the high-frequency analog light field, leading to the incorrect recording of moiré patterns. It also demonstrates the effects of applying an anti-aliasing filter to prevent aliasing and the use of effect filters (sharpening and contrast) to enhance the visual appeal of the image.

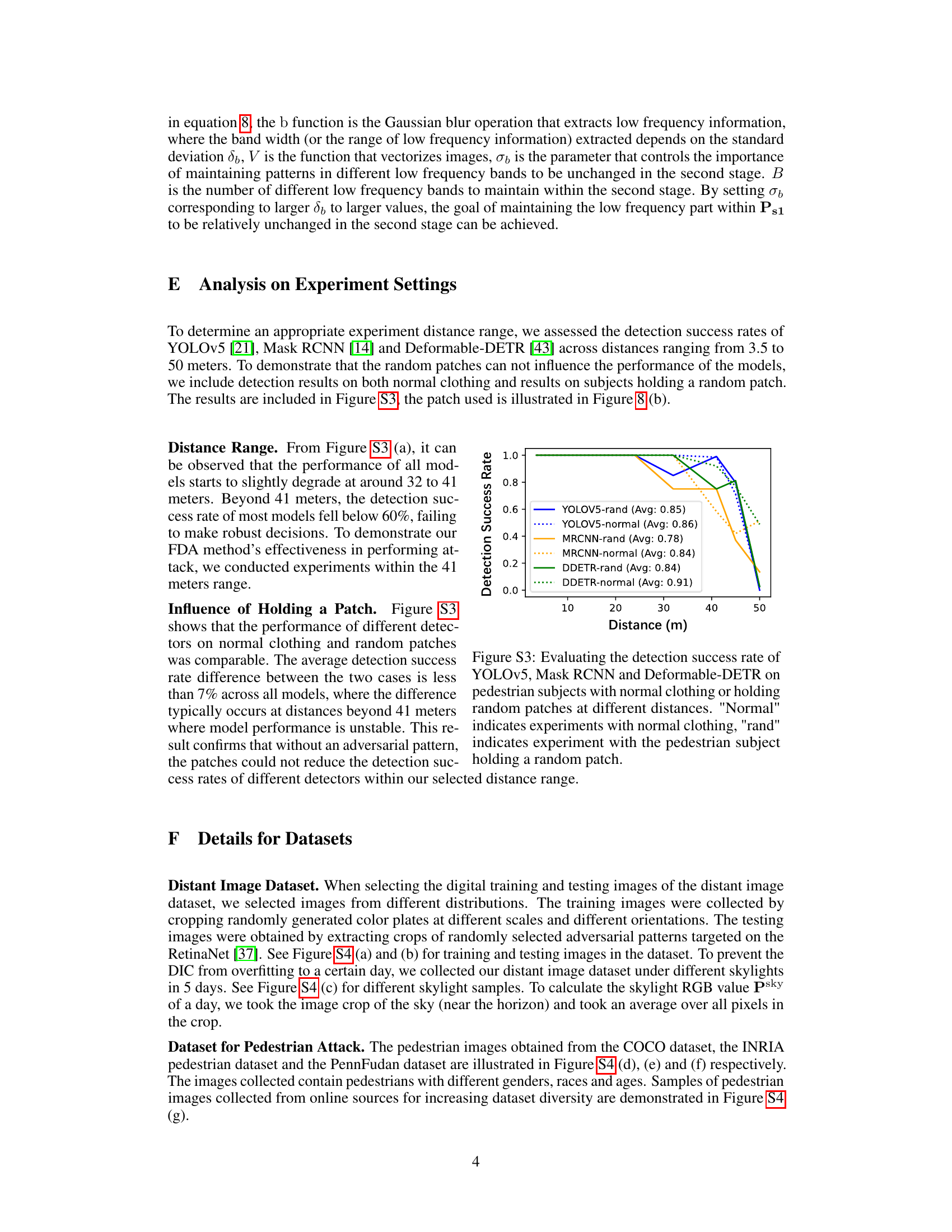

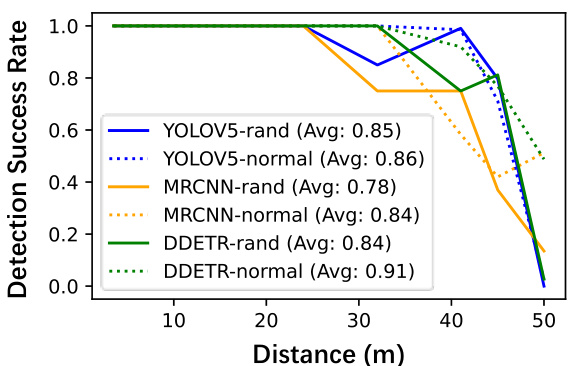

This figure shows the detection success rate of three different pedestrian detection models (YOLOv5, Mask RCNN, and Deformable-DETR) at various distances. Two scenarios are compared: one with subjects wearing normal clothing and one with subjects holding a random patch. The results demonstrate the performance drop of these models as the distance increases and shows that the random patches do not significantly affect the detection performance. This data helps to justify the selection of the distance range used in the main experiments.

This figure shows the results of the Distant Image Converter (DIC) experiment. Subfigure (a) is a graph comparing the performance of DIC against other methods (naive method and FCNs) in converting short-distance images to simulate their appearance at longer distances. The y-axis represents the L2-norm error between the converted images and real-world images, while the x-axis represents the distance. Subfigure (b) shows a qualitative comparison of the results, displaying example images from each method side-by-side with a real-world example for reference.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed Full Distance Attack (FDA) method against the baseline AdvTshirt method across varying distances. The y-axis represents the Average Success Rate (ASR) of the adversarial attacks, and the x-axis shows the distance in meters. The FDA method consistently outperforms AdvTshirt, especially at longer ranges, demonstrating its effectiveness in evading pedestrian detection even at greater distances.

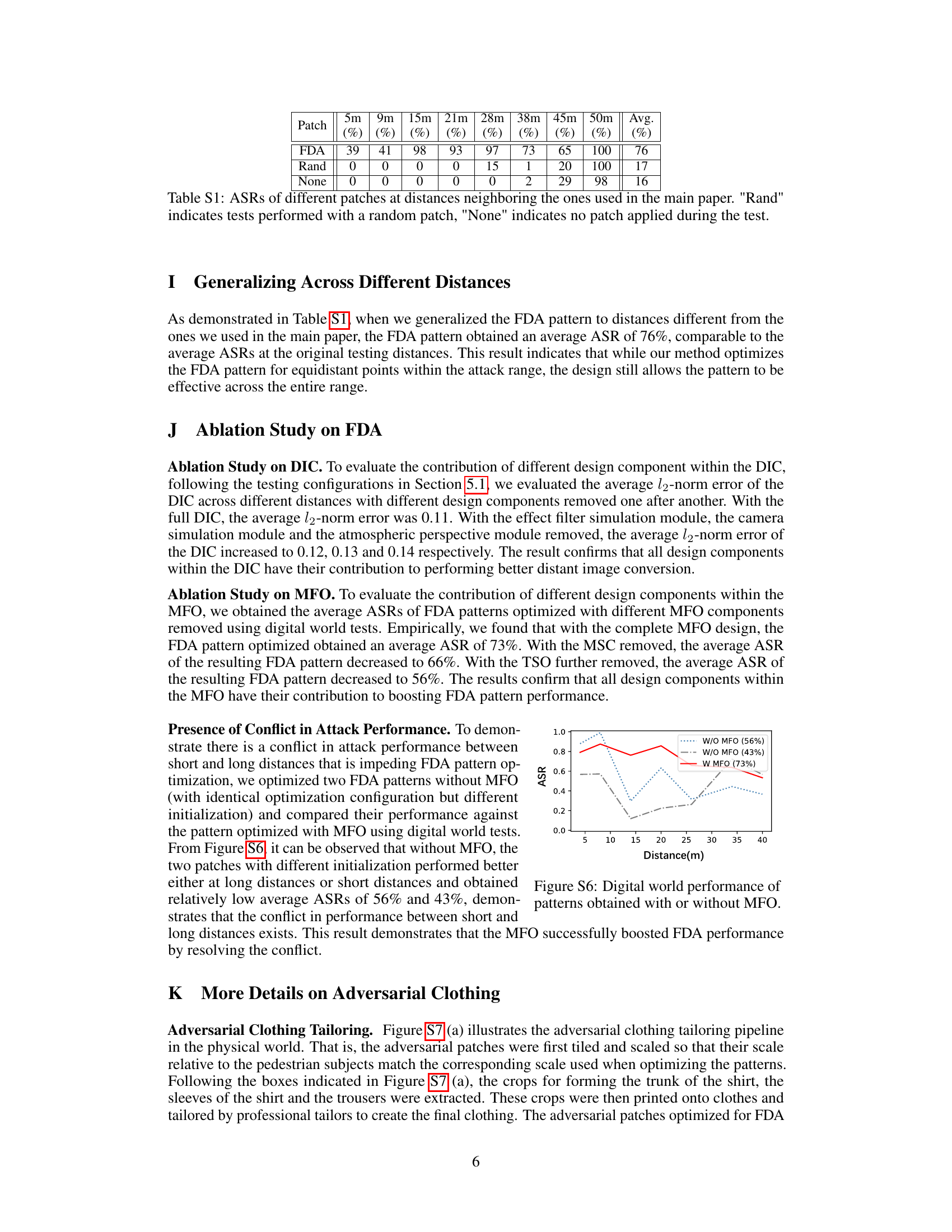

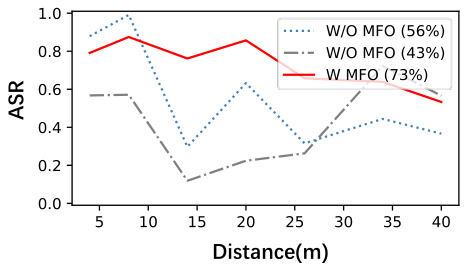

This figure shows the digital world attack success rate (ASR) of adversarial patterns optimized with and without the Multi-Frequency Optimization (MFO) technique. Two patterns were optimized without MFO, each with a different initialization. The figure demonstrates that without MFO, the attack performance is inconsistent across different distances, with one pattern performing better at shorter distances and the other at longer distances. The MFO technique significantly improves performance, resulting in a more consistent and higher ASR across all distances.

More on tables

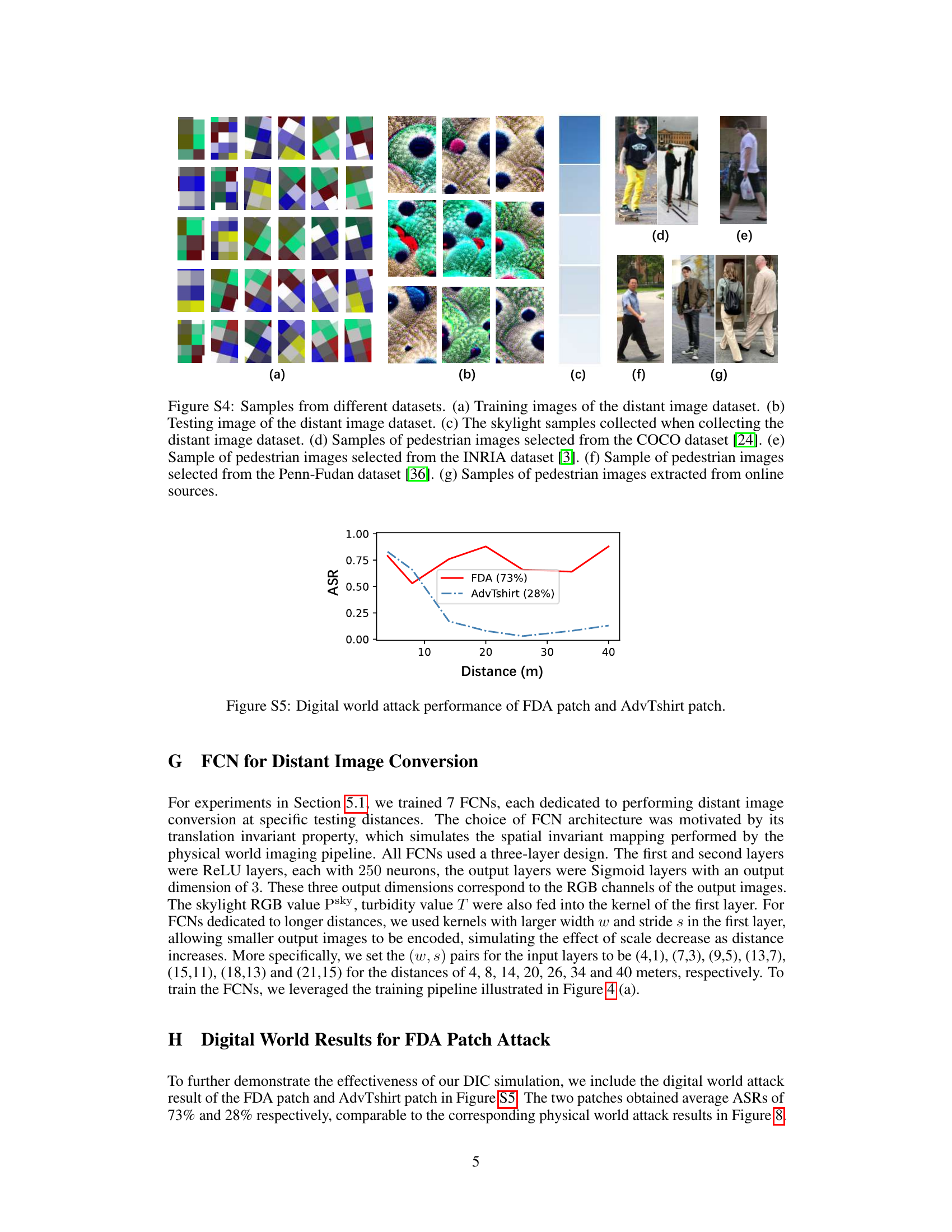

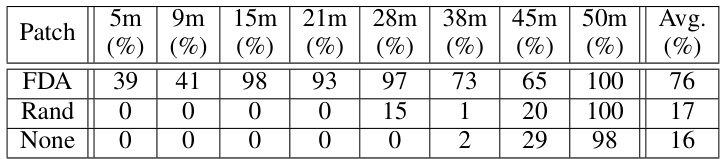

This table presents the generalization ability of the proposed FDA method across various distances. It shows the attack success rate (ASR) for FDA patches, random patches, and no patches (control group) at several distances (5m, 9m, 15m, 21m, 28m, 38m, 45m, 50m). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of FDA across various distances, showing consistently higher ASRs than random and control groups, indicating that the model remains robust even at distances not specifically optimized during the training phase.

This table presents the Average Success Rates (ASR) of the FDA clothing method across various distances and Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds when used against three different object detection models: YOLOv5, Deformable DETR, and RetinaNet (with PVT backbone). The IoU threshold represents the minimum overlap required between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth bounding box for a detection to be considered correct. The mean column provides the average ASR across all IoU thresholds, offering a more holistic view of the model’s performance.

Full paper#